User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

ObGyn’s steady progress toward going green in the OR—but gaps persist

Have you ever looked at the operating room (OR) trash bin at the end of a case and wondered if all that waste is necessary? Since I started my residency, not a day goes by that I have not asked myself this question.

In the mid-1990s, John Elkington introduced the concept of the triple bottom line—that is, people, planet, and profit—for implementation and measurement of sustainability in businesses.1 The health care sector is no exception when it comes to the bottom line! However, “people” remain the priority. What is our role, as ObGyns, in protecting the “planet” while keeping the “people” safe?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), climate change remains the single biggest health threat to humanity.2 The health care system is both the victim and the culprit. Studies suggest that the health care system, second to the food industry, is the biggest contributor to waste production in the United States. This sector generates more than 6,000 metric tons of waste each day and nearly 4 million tons (3.6 million metric tons) of solid waste each year.3 The health care system is responsible for an estimated 8% to 10% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the United States; the US health care system alone contributes to more than one-fourth of the global health care carbon footprint. If it were a country, the US health care system would rank 13th among all countries in emissions.4In turn, pollution produced by the health sector negatively impacts population health, further burdening the health care system. According to 2013 study data, the annual health damage caused by health care pollution was comparable to that of the deaths caused by preventable medical error.4

Aside from the environmental aspects, hospital waste disposal is expensive; reducing this cost is a potential area of interest for institutions.

As ObGyns, what is our role in reducing our waste generation and carbon footprint while keeping patients safe?

Defining health care waste, and disposal considerations

The WHO defines health care waste as including “the waste generated by health-care establishments, research facilities, and laboratories” as well as waste from scattered sources such as home dialysis and insulin injections.5 Despite representing a relatively small physical area of hospitals, labor and delivery units combined with ORs account for approximately 70% of all hospital waste.3 Operating room waste consists of disposable surgical supplies, personal protective equipment, drapes, plastic wrappers, sterile blue wraps, glass, cardboard, packaging material, medications, fluids, and other materials (FIGURE 1).

The WHO also notes that of all the waste generated by health care activities, about 85% is general, nonhazardous waste that is comparable to domestic waste.6 Hazardous waste is any material that poses a health risk, including potentially infectious materials, such as blood-soaked gauze, sharps, pharmaceuticals, or radioactive materials.6

Disposal of hazardous waste is expensiveand energy consuming as it is typically incinerated rather than disposed of in a landfill. This process produces substantial greenhouse gases, about 3 kg of carbon dioxide for every 1 kg of hazardous waste.7

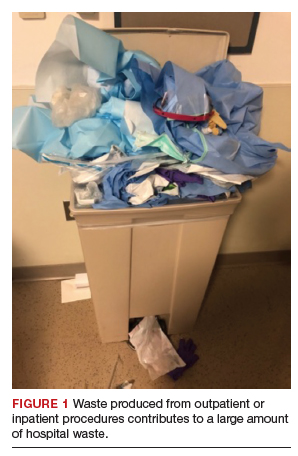

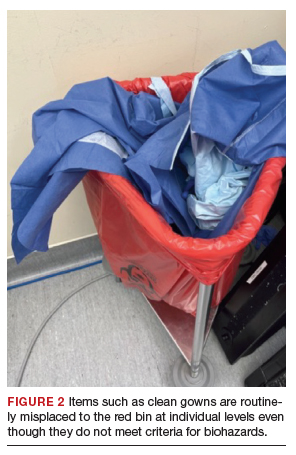

Red bags are used for hazardous waste disposal, while clear bags are used for general waste. Operating rooms produce about two-thirds of the hospital red-bag waste.8 Waste segregation unfortunately is not accurate, and as much as 90% of OR general waste is improperly designated as hazardous waste.3 Drapes and uncontaminated, needleless syringes, for example, should be disposed of in clear bags, but often they are instead directed to the red-bag and sharps container (FIGURE 2).

Obstetrics and gynecology has an important role to play in accurate waste segregation given the specialty’s frequent interaction with bodily fluids. Clinicians and other staff need to recognize and appropriately separate hazardous waste from general waste. For instance, not all fabrics involved in a case should be disposed of in the red bin, only those saturated with blood or body fluids. Educating health care staff and placing instruction posters on the red trash bins potentially could aid in accurate waste segregation and reduce regulated waste while decreasing disposal costs.

Recycling in the OR

Recycling has become an established practice in many health care facilities and ORs. Studies suggest that introducing recycling programs in ORs not only reduces carbon footprints but also reduces costs.3 One study reported that US academic medical centers consume 2 million lb ($15 million) each year of recoverable medical supplies.9

Single-stream recycling, a system in which all recyclable material—including plastics, paper, metal, and glass—are placed in a single bin without segregation at the collection site, has gained in popularity. Recycling can be implemented both in ORs and in other perioperative areas where regular trash bins are located.

In a study done at Oxford University Hospitals in the United Kingdom, introducing recycling bins in every OR, as well as in recovery and staff rest areas, helped improve waste segregation such that approximately 22% of OR waste was recycled.10 Studies show that recycling programs not only decrease the health care carbon footprint but also have a considerable financial impact. Albert and colleagues demonstrated that introducing a single-stream recycling program to a 9-OR day (or ambulatory) surgery center could redirect more than 4 tons of waste each month and saved thousands of dollars.11

Despite continued improvement in recycling programs, the segregation process is still far from optimal. In a survey done at the Mayo Clinic by Azouz and colleagues, more than half of the staff reported being unclear about which OR items are recyclable and nearly half reported that lack of knowledge was the barrier to proper recycling.12 That study also showed that after implementation of a recycling education program, costs decreased 10% relative to the same time period in prior years.12

Blue wraps. One example of recycling optimization is blue wraps, the polypropylene (No. 5 plastic) material used for wrapping surgical instruments. Blue wraps account for approximately 19% of OR waste and 5% of all hospital waste.11 Blue wraps are not biodegradable and also are not widely recycled. In recent years, a resale market has emerged for blue wraps, as they can be used for production of other No. 5 plastic items.9 By reselling blue wraps, revenue can be generated by recycling a necessary packing material that would otherwise require payment for disposal.

Sterility considerations. While recycling in ORs may raise concern due to the absolute sterility required in procedural settings, technologic developments have been promising in advancing safe recycling to reduce carbon footprints and health care costs without compromising patients’ safety. Segregation of waste from recyclable packaging material prior to the case, as well as directing trash to the correct bin (regular vs red bin), is one example. Moreover, because about 80% of all OR waste is generated during the set up before the patient arrives in the OR, it is not contaminated and can be safely recycled.13

Continue to: Packaging material...

Packaging material

A substantial part of OR waste consists of packaging material; of all OR waste, 26% consists of plastics and 7%, paper and cartons.14 Increasing use of disposable or “single use” medical products in ORs, along with the intention to safeguard sterility, contributes significantly to the generation of medical waste in operating units. Containers, wraps and overwraps, cardboard, and plastic packaging are all composed of materials that when clean, can be recycled; however, these items often end up in the landfill (FIGURE 3).

Although the segregation of packaging material to recycling versus regular trash versus red bin is of paramount importance, packaging design plays a significant role as well. In 2018, Boston Scientific introduced a new packaging design for ureteral stents that reduced plastic use in packaging by 120,000 lb each year.15 Despite the advances in the medical packaging industry to increase sustainability while safeguarding sterility for medical devices, there is still room for innovation in this area.

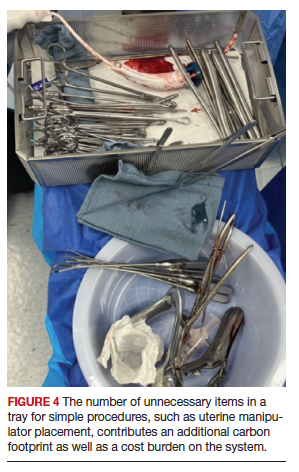

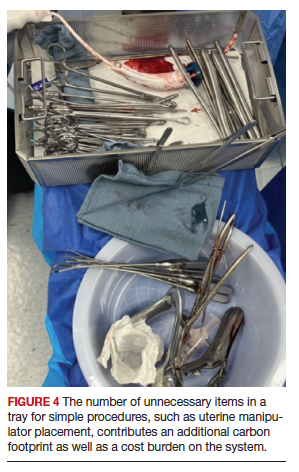

Reducing overage by judicious selection of surgical devices, instruments, and supplies

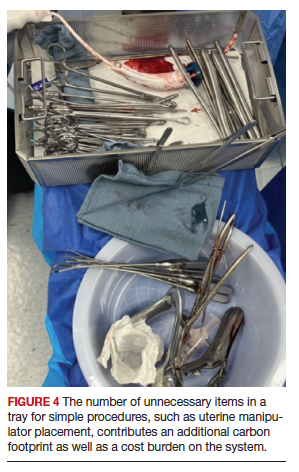

Overage is the term used to describe surgical inventory that is opened and prepared for surgery but ultimately not used and therefore discarded. Design of surgical carts and instrument and supply selection requires direct input from ObGyns. Opening only the needed instruments while ensuring ready availability of potentially needed supplies can significantly reduce OR waste generation as well as decrease chemical pollution generated by instrument sterilization. Decreasing OR overage reduces overall costs as well (FIGURE 4).

In a pilot study at the University of Massachusetts, Albert and colleagues examined the sets of disposable items and instruments designated for common plastic and hand surgery procedures.11 They identified the supplies and instruments that are routinely opened and wasted, based on surgeons’ interview responses, and redesigned the sets. Fifteen items were removed from disposable plastic surgery packs and 7 items from hand surgery packs. The authors reported saving thousands of dollars per year with these changes alone, as well as reducing waste.11 This same concept easily could be implemented in obstetrics and gynecology. We must ask ourselves: Do we always need, for example, a complete dilation and curettage kit to place the uterine manipulator prior to a minimally invasive hysterectomy?

In another pilot study, Greenberg and colleagues investigated whether cesarean deliveries consistently could be performed in a safe manner with only 20 instruments in the surgical kit.16 Obstetricians rated the 20-instrument kit an 8.7 out of 10 for performing cesarean deliveries safely.16

In addition to instrument selection, surgeons have a role in other supply use and waste generation: for instance, opening multiple pairs of surgical gloves and surgical gowns in advance when most of them will not be used during the case. Furthermore, many ObGyn surgeons routinely change gloves or even gowns during gynecologic procedures when they go back and forth between the vaginal and abdominal fields. Is the perineum “dirty” after application of a surgical prep solution?

In an observational study, Shockley and colleagues investigated the type and quantity of bacteria found intraoperatively on the abdomen, vagina, surgical gloves, instrument tips, and uterus at distinct time points during total laparoscopic hysterectomy.17 They showed that in 98.9% of cultures, the overall bacterial concentrations did not exceed the threshold for infection. There was no bacterial growth from vaginal cultures, and the only samples with some bacterial growth belonged to the surgeon’s gloves after specimen extraction; about one-third of samples showed growth after specimen extraction, but only 1 sample had a bacterial load above the infectious threshold of 5,000 colony-forming units per mL. The authors therefore suggested that if a surgeon changes gloves, doing so after specimen extraction and before turning attention back to the abdomen for vaginal cuff closure may be most effective in reducing bacterial load.17

Surgical site infection contributes to medical cost and likely medical waste as well. For example, surgical site infection may require prolonged treatments, tests, and medical instruments. In severe cases with abscesses, treatment entails hospitalization with prolonged antibiotic therapy with or without procedures to drain the collections. Further research therefore is warranted to investigate safe and environmentally friendly practices.

Myriad products are introduced to the medical system each day, some of which replace conventional tools. For instance, low-density polyethylene, or LDPE, transfer sheet is advertised for lateral patient transfer from the OR table to the bed or stretcher. This No. 4–coded plastic, while recyclable, is routinely discarded as trash in ORs. One ergonomic study found that reusable slide boards are as effective for reducing friction and staff muscle activities and are noninferior to the plastic sheets.18

Steps to making an impact

Operating rooms and labor and delivery units are responsible for a large proportion of hospital waste, and therefore they are of paramount importance in reducing waste and carbon footprint at the individual and institutional level. Reduction of OR waste not only is environmentally conscious but also decreases cost. Steps as small as individual practices to as big as changing infrastructures can make an impact. For instance:

- redesigning surgical carts

- reformulating surgeon-specific supply lists

- raising awareness about surgical overage

- encouraging recycling through education and audit

- optimizing surgical waste segregation through educational posters.

These are all simple steps that could significantly reduce waste and carbon footprint.

Bottom line

Although waste reduction is the responsibility of all health care providers, as leaders in their workplace physicians can serve as role models by implementing “green” practices in procedural units. Raising awareness and using a team approach is critical to succeed in our endeavors to move toward an environmentally friendly future. ●

- Elkington J. Towards the sustainable corporation: win-winwin business strategies for sustainable development. Calif Manage Rev. 1994;36:90-100.

- Climate change and health. October 30, 2021. World Health Organization. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.who .int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and -health

- Kwakye G, Brat GA, Makary MA. Green surgical practices for health care. Arch Surg. 2011;146:131-136.

- Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental impacts of the US health care system and effects on public health. PloS One. 2016;11:e0157014.

- Pruss A, Giroult E, Rushbrook P. Safe management of wastes from health-care activities. World Health Organization; 1999.

- Health-care waste. February 8, 2018. World Health Organization. Accessed October 4, 2022. https://www.who. int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste2

- Southorn T, Norrish AR, Gardner K, et al. Reducing the carbon footprint of the operating theatre: a multicentre quality improvement report. J Perioper Pract. 2013;23:144-146.

- Greening the OR. Practice Greenhealth. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://practicegreenhealth.org/topics/greening -operating-room/greening-or

- Babu MA, Dalenberg AK, Goodsell G, et al. Greening the operating room: results of a scalable initiative to reduce waste and recover supply costs. Neurosurgery. 2019;85:432-437.

- Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. Introducing recycling into the operating theatres. Mapping Greener Healthcare. Accessed October 14, 2022. https://map .sustainablehealthcare.org.uk/oxford-radcliffe-hospitals -nhs-trust/introducing-recycling-operating-theatres

- Albert MG, Rothkopf DM. Operating room waste reduction in plastic and hand surgery. Plast Surg. 2015;23:235-238.

- Azouz S, Boyll P, Swanson M, et al. Managing barriers to recycling in the operating room. Am J Surg. 2019;217:634-638.

- Wyssusek KH, Keys MT, van Zundert AAJ. Operating room greening initiatives—the old, the new, and the way forward: a narrative review. Waste Manag Res. 2019;37:3-19.

- Tieszen ME, Gruenberg JC. A quantitative, qualitative, and critical assessment of surgical waste: surgeons venture through the trash can. JAMA. 1992;267:2765-2768.

- Boston Scientific 2018 Performance Report. Boston Scientific. Accessed November 19, 2022. https://www.bostonscientific. com/content/dam/bostonscientific/corporate/citizenship /sustainability/Boston_Scientific_Performance _Report_2018.pdf

- Greenberg JA, Wylie B, Robinson JN. A pilot study to assess the adequacy of the Brigham 20 Kit for cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117:157-159.

- Shockley ME, Beran B, Nutting H, et al. Sterility of selected operative sites during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:990-997.

- Al-Qaisi SK, El Tannir A, Younan LA, et al. An ergonomic assessment of using laterally-tilting operating room tables and friction reducing devices for patient lateral transfers. Appl Ergon. 2020;87:103122.

Have you ever looked at the operating room (OR) trash bin at the end of a case and wondered if all that waste is necessary? Since I started my residency, not a day goes by that I have not asked myself this question.

In the mid-1990s, John Elkington introduced the concept of the triple bottom line—that is, people, planet, and profit—for implementation and measurement of sustainability in businesses.1 The health care sector is no exception when it comes to the bottom line! However, “people” remain the priority. What is our role, as ObGyns, in protecting the “planet” while keeping the “people” safe?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), climate change remains the single biggest health threat to humanity.2 The health care system is both the victim and the culprit. Studies suggest that the health care system, second to the food industry, is the biggest contributor to waste production in the United States. This sector generates more than 6,000 metric tons of waste each day and nearly 4 million tons (3.6 million metric tons) of solid waste each year.3 The health care system is responsible for an estimated 8% to 10% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the United States; the US health care system alone contributes to more than one-fourth of the global health care carbon footprint. If it were a country, the US health care system would rank 13th among all countries in emissions.4In turn, pollution produced by the health sector negatively impacts population health, further burdening the health care system. According to 2013 study data, the annual health damage caused by health care pollution was comparable to that of the deaths caused by preventable medical error.4

Aside from the environmental aspects, hospital waste disposal is expensive; reducing this cost is a potential area of interest for institutions.

As ObGyns, what is our role in reducing our waste generation and carbon footprint while keeping patients safe?

Defining health care waste, and disposal considerations

The WHO defines health care waste as including “the waste generated by health-care establishments, research facilities, and laboratories” as well as waste from scattered sources such as home dialysis and insulin injections.5 Despite representing a relatively small physical area of hospitals, labor and delivery units combined with ORs account for approximately 70% of all hospital waste.3 Operating room waste consists of disposable surgical supplies, personal protective equipment, drapes, plastic wrappers, sterile blue wraps, glass, cardboard, packaging material, medications, fluids, and other materials (FIGURE 1).

The WHO also notes that of all the waste generated by health care activities, about 85% is general, nonhazardous waste that is comparable to domestic waste.6 Hazardous waste is any material that poses a health risk, including potentially infectious materials, such as blood-soaked gauze, sharps, pharmaceuticals, or radioactive materials.6

Disposal of hazardous waste is expensiveand energy consuming as it is typically incinerated rather than disposed of in a landfill. This process produces substantial greenhouse gases, about 3 kg of carbon dioxide for every 1 kg of hazardous waste.7

Red bags are used for hazardous waste disposal, while clear bags are used for general waste. Operating rooms produce about two-thirds of the hospital red-bag waste.8 Waste segregation unfortunately is not accurate, and as much as 90% of OR general waste is improperly designated as hazardous waste.3 Drapes and uncontaminated, needleless syringes, for example, should be disposed of in clear bags, but often they are instead directed to the red-bag and sharps container (FIGURE 2).

Obstetrics and gynecology has an important role to play in accurate waste segregation given the specialty’s frequent interaction with bodily fluids. Clinicians and other staff need to recognize and appropriately separate hazardous waste from general waste. For instance, not all fabrics involved in a case should be disposed of in the red bin, only those saturated with blood or body fluids. Educating health care staff and placing instruction posters on the red trash bins potentially could aid in accurate waste segregation and reduce regulated waste while decreasing disposal costs.

Recycling in the OR

Recycling has become an established practice in many health care facilities and ORs. Studies suggest that introducing recycling programs in ORs not only reduces carbon footprints but also reduces costs.3 One study reported that US academic medical centers consume 2 million lb ($15 million) each year of recoverable medical supplies.9

Single-stream recycling, a system in which all recyclable material—including plastics, paper, metal, and glass—are placed in a single bin without segregation at the collection site, has gained in popularity. Recycling can be implemented both in ORs and in other perioperative areas where regular trash bins are located.

In a study done at Oxford University Hospitals in the United Kingdom, introducing recycling bins in every OR, as well as in recovery and staff rest areas, helped improve waste segregation such that approximately 22% of OR waste was recycled.10 Studies show that recycling programs not only decrease the health care carbon footprint but also have a considerable financial impact. Albert and colleagues demonstrated that introducing a single-stream recycling program to a 9-OR day (or ambulatory) surgery center could redirect more than 4 tons of waste each month and saved thousands of dollars.11

Despite continued improvement in recycling programs, the segregation process is still far from optimal. In a survey done at the Mayo Clinic by Azouz and colleagues, more than half of the staff reported being unclear about which OR items are recyclable and nearly half reported that lack of knowledge was the barrier to proper recycling.12 That study also showed that after implementation of a recycling education program, costs decreased 10% relative to the same time period in prior years.12

Blue wraps. One example of recycling optimization is blue wraps, the polypropylene (No. 5 plastic) material used for wrapping surgical instruments. Blue wraps account for approximately 19% of OR waste and 5% of all hospital waste.11 Blue wraps are not biodegradable and also are not widely recycled. In recent years, a resale market has emerged for blue wraps, as they can be used for production of other No. 5 plastic items.9 By reselling blue wraps, revenue can be generated by recycling a necessary packing material that would otherwise require payment for disposal.

Sterility considerations. While recycling in ORs may raise concern due to the absolute sterility required in procedural settings, technologic developments have been promising in advancing safe recycling to reduce carbon footprints and health care costs without compromising patients’ safety. Segregation of waste from recyclable packaging material prior to the case, as well as directing trash to the correct bin (regular vs red bin), is one example. Moreover, because about 80% of all OR waste is generated during the set up before the patient arrives in the OR, it is not contaminated and can be safely recycled.13

Continue to: Packaging material...

Packaging material

A substantial part of OR waste consists of packaging material; of all OR waste, 26% consists of plastics and 7%, paper and cartons.14 Increasing use of disposable or “single use” medical products in ORs, along with the intention to safeguard sterility, contributes significantly to the generation of medical waste in operating units. Containers, wraps and overwraps, cardboard, and plastic packaging are all composed of materials that when clean, can be recycled; however, these items often end up in the landfill (FIGURE 3).

Although the segregation of packaging material to recycling versus regular trash versus red bin is of paramount importance, packaging design plays a significant role as well. In 2018, Boston Scientific introduced a new packaging design for ureteral stents that reduced plastic use in packaging by 120,000 lb each year.15 Despite the advances in the medical packaging industry to increase sustainability while safeguarding sterility for medical devices, there is still room for innovation in this area.

Reducing overage by judicious selection of surgical devices, instruments, and supplies

Overage is the term used to describe surgical inventory that is opened and prepared for surgery but ultimately not used and therefore discarded. Design of surgical carts and instrument and supply selection requires direct input from ObGyns. Opening only the needed instruments while ensuring ready availability of potentially needed supplies can significantly reduce OR waste generation as well as decrease chemical pollution generated by instrument sterilization. Decreasing OR overage reduces overall costs as well (FIGURE 4).

In a pilot study at the University of Massachusetts, Albert and colleagues examined the sets of disposable items and instruments designated for common plastic and hand surgery procedures.11 They identified the supplies and instruments that are routinely opened and wasted, based on surgeons’ interview responses, and redesigned the sets. Fifteen items were removed from disposable plastic surgery packs and 7 items from hand surgery packs. The authors reported saving thousands of dollars per year with these changes alone, as well as reducing waste.11 This same concept easily could be implemented in obstetrics and gynecology. We must ask ourselves: Do we always need, for example, a complete dilation and curettage kit to place the uterine manipulator prior to a minimally invasive hysterectomy?

In another pilot study, Greenberg and colleagues investigated whether cesarean deliveries consistently could be performed in a safe manner with only 20 instruments in the surgical kit.16 Obstetricians rated the 20-instrument kit an 8.7 out of 10 for performing cesarean deliveries safely.16

In addition to instrument selection, surgeons have a role in other supply use and waste generation: for instance, opening multiple pairs of surgical gloves and surgical gowns in advance when most of them will not be used during the case. Furthermore, many ObGyn surgeons routinely change gloves or even gowns during gynecologic procedures when they go back and forth between the vaginal and abdominal fields. Is the perineum “dirty” after application of a surgical prep solution?

In an observational study, Shockley and colleagues investigated the type and quantity of bacteria found intraoperatively on the abdomen, vagina, surgical gloves, instrument tips, and uterus at distinct time points during total laparoscopic hysterectomy.17 They showed that in 98.9% of cultures, the overall bacterial concentrations did not exceed the threshold for infection. There was no bacterial growth from vaginal cultures, and the only samples with some bacterial growth belonged to the surgeon’s gloves after specimen extraction; about one-third of samples showed growth after specimen extraction, but only 1 sample had a bacterial load above the infectious threshold of 5,000 colony-forming units per mL. The authors therefore suggested that if a surgeon changes gloves, doing so after specimen extraction and before turning attention back to the abdomen for vaginal cuff closure may be most effective in reducing bacterial load.17

Surgical site infection contributes to medical cost and likely medical waste as well. For example, surgical site infection may require prolonged treatments, tests, and medical instruments. In severe cases with abscesses, treatment entails hospitalization with prolonged antibiotic therapy with or without procedures to drain the collections. Further research therefore is warranted to investigate safe and environmentally friendly practices.

Myriad products are introduced to the medical system each day, some of which replace conventional tools. For instance, low-density polyethylene, or LDPE, transfer sheet is advertised for lateral patient transfer from the OR table to the bed or stretcher. This No. 4–coded plastic, while recyclable, is routinely discarded as trash in ORs. One ergonomic study found that reusable slide boards are as effective for reducing friction and staff muscle activities and are noninferior to the plastic sheets.18

Steps to making an impact

Operating rooms and labor and delivery units are responsible for a large proportion of hospital waste, and therefore they are of paramount importance in reducing waste and carbon footprint at the individual and institutional level. Reduction of OR waste not only is environmentally conscious but also decreases cost. Steps as small as individual practices to as big as changing infrastructures can make an impact. For instance:

- redesigning surgical carts

- reformulating surgeon-specific supply lists

- raising awareness about surgical overage

- encouraging recycling through education and audit

- optimizing surgical waste segregation through educational posters.

These are all simple steps that could significantly reduce waste and carbon footprint.

Bottom line

Although waste reduction is the responsibility of all health care providers, as leaders in their workplace physicians can serve as role models by implementing “green” practices in procedural units. Raising awareness and using a team approach is critical to succeed in our endeavors to move toward an environmentally friendly future. ●

Have you ever looked at the operating room (OR) trash bin at the end of a case and wondered if all that waste is necessary? Since I started my residency, not a day goes by that I have not asked myself this question.

In the mid-1990s, John Elkington introduced the concept of the triple bottom line—that is, people, planet, and profit—for implementation and measurement of sustainability in businesses.1 The health care sector is no exception when it comes to the bottom line! However, “people” remain the priority. What is our role, as ObGyns, in protecting the “planet” while keeping the “people” safe?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), climate change remains the single biggest health threat to humanity.2 The health care system is both the victim and the culprit. Studies suggest that the health care system, second to the food industry, is the biggest contributor to waste production in the United States. This sector generates more than 6,000 metric tons of waste each day and nearly 4 million tons (3.6 million metric tons) of solid waste each year.3 The health care system is responsible for an estimated 8% to 10% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the United States; the US health care system alone contributes to more than one-fourth of the global health care carbon footprint. If it were a country, the US health care system would rank 13th among all countries in emissions.4In turn, pollution produced by the health sector negatively impacts population health, further burdening the health care system. According to 2013 study data, the annual health damage caused by health care pollution was comparable to that of the deaths caused by preventable medical error.4

Aside from the environmental aspects, hospital waste disposal is expensive; reducing this cost is a potential area of interest for institutions.

As ObGyns, what is our role in reducing our waste generation and carbon footprint while keeping patients safe?

Defining health care waste, and disposal considerations

The WHO defines health care waste as including “the waste generated by health-care establishments, research facilities, and laboratories” as well as waste from scattered sources such as home dialysis and insulin injections.5 Despite representing a relatively small physical area of hospitals, labor and delivery units combined with ORs account for approximately 70% of all hospital waste.3 Operating room waste consists of disposable surgical supplies, personal protective equipment, drapes, plastic wrappers, sterile blue wraps, glass, cardboard, packaging material, medications, fluids, and other materials (FIGURE 1).

The WHO also notes that of all the waste generated by health care activities, about 85% is general, nonhazardous waste that is comparable to domestic waste.6 Hazardous waste is any material that poses a health risk, including potentially infectious materials, such as blood-soaked gauze, sharps, pharmaceuticals, or radioactive materials.6

Disposal of hazardous waste is expensiveand energy consuming as it is typically incinerated rather than disposed of in a landfill. This process produces substantial greenhouse gases, about 3 kg of carbon dioxide for every 1 kg of hazardous waste.7

Red bags are used for hazardous waste disposal, while clear bags are used for general waste. Operating rooms produce about two-thirds of the hospital red-bag waste.8 Waste segregation unfortunately is not accurate, and as much as 90% of OR general waste is improperly designated as hazardous waste.3 Drapes and uncontaminated, needleless syringes, for example, should be disposed of in clear bags, but often they are instead directed to the red-bag and sharps container (FIGURE 2).

Obstetrics and gynecology has an important role to play in accurate waste segregation given the specialty’s frequent interaction with bodily fluids. Clinicians and other staff need to recognize and appropriately separate hazardous waste from general waste. For instance, not all fabrics involved in a case should be disposed of in the red bin, only those saturated with blood or body fluids. Educating health care staff and placing instruction posters on the red trash bins potentially could aid in accurate waste segregation and reduce regulated waste while decreasing disposal costs.

Recycling in the OR

Recycling has become an established practice in many health care facilities and ORs. Studies suggest that introducing recycling programs in ORs not only reduces carbon footprints but also reduces costs.3 One study reported that US academic medical centers consume 2 million lb ($15 million) each year of recoverable medical supplies.9

Single-stream recycling, a system in which all recyclable material—including plastics, paper, metal, and glass—are placed in a single bin without segregation at the collection site, has gained in popularity. Recycling can be implemented both in ORs and in other perioperative areas where regular trash bins are located.

In a study done at Oxford University Hospitals in the United Kingdom, introducing recycling bins in every OR, as well as in recovery and staff rest areas, helped improve waste segregation such that approximately 22% of OR waste was recycled.10 Studies show that recycling programs not only decrease the health care carbon footprint but also have a considerable financial impact. Albert and colleagues demonstrated that introducing a single-stream recycling program to a 9-OR day (or ambulatory) surgery center could redirect more than 4 tons of waste each month and saved thousands of dollars.11

Despite continued improvement in recycling programs, the segregation process is still far from optimal. In a survey done at the Mayo Clinic by Azouz and colleagues, more than half of the staff reported being unclear about which OR items are recyclable and nearly half reported that lack of knowledge was the barrier to proper recycling.12 That study also showed that after implementation of a recycling education program, costs decreased 10% relative to the same time period in prior years.12

Blue wraps. One example of recycling optimization is blue wraps, the polypropylene (No. 5 plastic) material used for wrapping surgical instruments. Blue wraps account for approximately 19% of OR waste and 5% of all hospital waste.11 Blue wraps are not biodegradable and also are not widely recycled. In recent years, a resale market has emerged for blue wraps, as they can be used for production of other No. 5 plastic items.9 By reselling blue wraps, revenue can be generated by recycling a necessary packing material that would otherwise require payment for disposal.

Sterility considerations. While recycling in ORs may raise concern due to the absolute sterility required in procedural settings, technologic developments have been promising in advancing safe recycling to reduce carbon footprints and health care costs without compromising patients’ safety. Segregation of waste from recyclable packaging material prior to the case, as well as directing trash to the correct bin (regular vs red bin), is one example. Moreover, because about 80% of all OR waste is generated during the set up before the patient arrives in the OR, it is not contaminated and can be safely recycled.13

Continue to: Packaging material...

Packaging material

A substantial part of OR waste consists of packaging material; of all OR waste, 26% consists of plastics and 7%, paper and cartons.14 Increasing use of disposable or “single use” medical products in ORs, along with the intention to safeguard sterility, contributes significantly to the generation of medical waste in operating units. Containers, wraps and overwraps, cardboard, and plastic packaging are all composed of materials that when clean, can be recycled; however, these items often end up in the landfill (FIGURE 3).

Although the segregation of packaging material to recycling versus regular trash versus red bin is of paramount importance, packaging design plays a significant role as well. In 2018, Boston Scientific introduced a new packaging design for ureteral stents that reduced plastic use in packaging by 120,000 lb each year.15 Despite the advances in the medical packaging industry to increase sustainability while safeguarding sterility for medical devices, there is still room for innovation in this area.

Reducing overage by judicious selection of surgical devices, instruments, and supplies

Overage is the term used to describe surgical inventory that is opened and prepared for surgery but ultimately not used and therefore discarded. Design of surgical carts and instrument and supply selection requires direct input from ObGyns. Opening only the needed instruments while ensuring ready availability of potentially needed supplies can significantly reduce OR waste generation as well as decrease chemical pollution generated by instrument sterilization. Decreasing OR overage reduces overall costs as well (FIGURE 4).

In a pilot study at the University of Massachusetts, Albert and colleagues examined the sets of disposable items and instruments designated for common plastic and hand surgery procedures.11 They identified the supplies and instruments that are routinely opened and wasted, based on surgeons’ interview responses, and redesigned the sets. Fifteen items were removed from disposable plastic surgery packs and 7 items from hand surgery packs. The authors reported saving thousands of dollars per year with these changes alone, as well as reducing waste.11 This same concept easily could be implemented in obstetrics and gynecology. We must ask ourselves: Do we always need, for example, a complete dilation and curettage kit to place the uterine manipulator prior to a minimally invasive hysterectomy?

In another pilot study, Greenberg and colleagues investigated whether cesarean deliveries consistently could be performed in a safe manner with only 20 instruments in the surgical kit.16 Obstetricians rated the 20-instrument kit an 8.7 out of 10 for performing cesarean deliveries safely.16

In addition to instrument selection, surgeons have a role in other supply use and waste generation: for instance, opening multiple pairs of surgical gloves and surgical gowns in advance when most of them will not be used during the case. Furthermore, many ObGyn surgeons routinely change gloves or even gowns during gynecologic procedures when they go back and forth between the vaginal and abdominal fields. Is the perineum “dirty” after application of a surgical prep solution?

In an observational study, Shockley and colleagues investigated the type and quantity of bacteria found intraoperatively on the abdomen, vagina, surgical gloves, instrument tips, and uterus at distinct time points during total laparoscopic hysterectomy.17 They showed that in 98.9% of cultures, the overall bacterial concentrations did not exceed the threshold for infection. There was no bacterial growth from vaginal cultures, and the only samples with some bacterial growth belonged to the surgeon’s gloves after specimen extraction; about one-third of samples showed growth after specimen extraction, but only 1 sample had a bacterial load above the infectious threshold of 5,000 colony-forming units per mL. The authors therefore suggested that if a surgeon changes gloves, doing so after specimen extraction and before turning attention back to the abdomen for vaginal cuff closure may be most effective in reducing bacterial load.17

Surgical site infection contributes to medical cost and likely medical waste as well. For example, surgical site infection may require prolonged treatments, tests, and medical instruments. In severe cases with abscesses, treatment entails hospitalization with prolonged antibiotic therapy with or without procedures to drain the collections. Further research therefore is warranted to investigate safe and environmentally friendly practices.

Myriad products are introduced to the medical system each day, some of which replace conventional tools. For instance, low-density polyethylene, or LDPE, transfer sheet is advertised for lateral patient transfer from the OR table to the bed or stretcher. This No. 4–coded plastic, while recyclable, is routinely discarded as trash in ORs. One ergonomic study found that reusable slide boards are as effective for reducing friction and staff muscle activities and are noninferior to the plastic sheets.18

Steps to making an impact

Operating rooms and labor and delivery units are responsible for a large proportion of hospital waste, and therefore they are of paramount importance in reducing waste and carbon footprint at the individual and institutional level. Reduction of OR waste not only is environmentally conscious but also decreases cost. Steps as small as individual practices to as big as changing infrastructures can make an impact. For instance:

- redesigning surgical carts

- reformulating surgeon-specific supply lists

- raising awareness about surgical overage

- encouraging recycling through education and audit

- optimizing surgical waste segregation through educational posters.

These are all simple steps that could significantly reduce waste and carbon footprint.

Bottom line

Although waste reduction is the responsibility of all health care providers, as leaders in their workplace physicians can serve as role models by implementing “green” practices in procedural units. Raising awareness and using a team approach is critical to succeed in our endeavors to move toward an environmentally friendly future. ●

- Elkington J. Towards the sustainable corporation: win-winwin business strategies for sustainable development. Calif Manage Rev. 1994;36:90-100.

- Climate change and health. October 30, 2021. World Health Organization. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.who .int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and -health

- Kwakye G, Brat GA, Makary MA. Green surgical practices for health care. Arch Surg. 2011;146:131-136.

- Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental impacts of the US health care system and effects on public health. PloS One. 2016;11:e0157014.

- Pruss A, Giroult E, Rushbrook P. Safe management of wastes from health-care activities. World Health Organization; 1999.

- Health-care waste. February 8, 2018. World Health Organization. Accessed October 4, 2022. https://www.who. int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste2

- Southorn T, Norrish AR, Gardner K, et al. Reducing the carbon footprint of the operating theatre: a multicentre quality improvement report. J Perioper Pract. 2013;23:144-146.

- Greening the OR. Practice Greenhealth. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://practicegreenhealth.org/topics/greening -operating-room/greening-or

- Babu MA, Dalenberg AK, Goodsell G, et al. Greening the operating room: results of a scalable initiative to reduce waste and recover supply costs. Neurosurgery. 2019;85:432-437.

- Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. Introducing recycling into the operating theatres. Mapping Greener Healthcare. Accessed October 14, 2022. https://map .sustainablehealthcare.org.uk/oxford-radcliffe-hospitals -nhs-trust/introducing-recycling-operating-theatres

- Albert MG, Rothkopf DM. Operating room waste reduction in plastic and hand surgery. Plast Surg. 2015;23:235-238.

- Azouz S, Boyll P, Swanson M, et al. Managing barriers to recycling in the operating room. Am J Surg. 2019;217:634-638.

- Wyssusek KH, Keys MT, van Zundert AAJ. Operating room greening initiatives—the old, the new, and the way forward: a narrative review. Waste Manag Res. 2019;37:3-19.

- Tieszen ME, Gruenberg JC. A quantitative, qualitative, and critical assessment of surgical waste: surgeons venture through the trash can. JAMA. 1992;267:2765-2768.

- Boston Scientific 2018 Performance Report. Boston Scientific. Accessed November 19, 2022. https://www.bostonscientific. com/content/dam/bostonscientific/corporate/citizenship /sustainability/Boston_Scientific_Performance _Report_2018.pdf

- Greenberg JA, Wylie B, Robinson JN. A pilot study to assess the adequacy of the Brigham 20 Kit for cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117:157-159.

- Shockley ME, Beran B, Nutting H, et al. Sterility of selected operative sites during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:990-997.

- Al-Qaisi SK, El Tannir A, Younan LA, et al. An ergonomic assessment of using laterally-tilting operating room tables and friction reducing devices for patient lateral transfers. Appl Ergon. 2020;87:103122.

- Elkington J. Towards the sustainable corporation: win-winwin business strategies for sustainable development. Calif Manage Rev. 1994;36:90-100.

- Climate change and health. October 30, 2021. World Health Organization. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.who .int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and -health

- Kwakye G, Brat GA, Makary MA. Green surgical practices for health care. Arch Surg. 2011;146:131-136.

- Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental impacts of the US health care system and effects on public health. PloS One. 2016;11:e0157014.

- Pruss A, Giroult E, Rushbrook P. Safe management of wastes from health-care activities. World Health Organization; 1999.

- Health-care waste. February 8, 2018. World Health Organization. Accessed October 4, 2022. https://www.who. int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste2

- Southorn T, Norrish AR, Gardner K, et al. Reducing the carbon footprint of the operating theatre: a multicentre quality improvement report. J Perioper Pract. 2013;23:144-146.

- Greening the OR. Practice Greenhealth. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://practicegreenhealth.org/topics/greening -operating-room/greening-or

- Babu MA, Dalenberg AK, Goodsell G, et al. Greening the operating room: results of a scalable initiative to reduce waste and recover supply costs. Neurosurgery. 2019;85:432-437.

- Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. Introducing recycling into the operating theatres. Mapping Greener Healthcare. Accessed October 14, 2022. https://map .sustainablehealthcare.org.uk/oxford-radcliffe-hospitals -nhs-trust/introducing-recycling-operating-theatres

- Albert MG, Rothkopf DM. Operating room waste reduction in plastic and hand surgery. Plast Surg. 2015;23:235-238.

- Azouz S, Boyll P, Swanson M, et al. Managing barriers to recycling in the operating room. Am J Surg. 2019;217:634-638.

- Wyssusek KH, Keys MT, van Zundert AAJ. Operating room greening initiatives—the old, the new, and the way forward: a narrative review. Waste Manag Res. 2019;37:3-19.

- Tieszen ME, Gruenberg JC. A quantitative, qualitative, and critical assessment of surgical waste: surgeons venture through the trash can. JAMA. 1992;267:2765-2768.

- Boston Scientific 2018 Performance Report. Boston Scientific. Accessed November 19, 2022. https://www.bostonscientific. com/content/dam/bostonscientific/corporate/citizenship /sustainability/Boston_Scientific_Performance _Report_2018.pdf

- Greenberg JA, Wylie B, Robinson JN. A pilot study to assess the adequacy of the Brigham 20 Kit for cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117:157-159.

- Shockley ME, Beran B, Nutting H, et al. Sterility of selected operative sites during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:990-997.

- Al-Qaisi SK, El Tannir A, Younan LA, et al. An ergonomic assessment of using laterally-tilting operating room tables and friction reducing devices for patient lateral transfers. Appl Ergon. 2020;87:103122.

Understanding clinic-reported IVF success rates

The field of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) continues to evolve from its first successful birth in 1978 in England, and then in 1981 in the United States. Over the last 6 years, the total number of cycles in the U.S. has increased by 44% to nearly 370,000.

SART membership consists of more than 350 clinics throughout the United States, representing 80% of ART clinics. Over 95% of ART cycles in 2021 in the United States were performed in SART-member clinics.

SART is an invaluable resource for both patients and physicians. Their website includes a “Predict My Success” calculator that allows patients and physicians to enter individualized data to calculate the chance of having a baby over one or more complete cycles of IVF. To help us understand the pregnancy outcome data from ART – cycles per clinic along with national results – I posed the questions below to Amy Sparks, PhD, HCLD, director of the IVF and Andrology Laboratories and the Center for Advanced Reproductive Care at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City. Dr. Sparks is past president of SART and former chairperson of the SART Registry committee when the current Clinic Summary Report format was initially released.

Question: The Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act (FCSRCA) of 1992 mandated that all ART clinics report success rate data to the federal government, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a standardized manner. As ART is the only field in medicine to be required to annually report their patient outcomes, that is, all initiated cycles and live births, why do you believe this law was enacted and is limited to reproductive medicine?

Answer: The FCSRCA of 1992 was enacted in response to the lack of open and reliable pregnancy success rate information for patients seeking infertility care using assisted reproductive technologies. Success rates of 25%-50% were being advertised by independent clinics when, nationally, fewer than 15% of ART procedures led to live births. The Federal Trade Commission said such claims were deceptive and filed charges against five clinics, saying they misrepresented their success in helping women become pregnant. The government won one case by court order and the other four cases were settled out of court.

This field of medicine was in the spotlight as the majority of patients lacked insurance coverage for their ART cycles, and there was a strong desire to protect consumers paying out of pocket for relatively low success. Recognizing that the FTC’s mission is to ensure truth in advertising and not regulate medical care, Congress passed the FCSRCA, mandating that all centers providing ART services report all initiated cycles and their outcomes. The CDC was appointed as the agency responsible for collecting cycle data and reporting outcomes. Centers not reporting their cycles are listed as nonreporting centers.

This act also established standards for accreditation of embryology laboratories including personnel and traditional clinical laboratory management requirements. These standards serve as the foundation for embryology laboratory accrediting agencies.

Q: Why have live-birth rates on SART appeared to be focused on “per IVF cycle” as opposed to the CDC reporting of live births “per embryo transfer?”

A: An ART cycle “start” is defined as the initiation of ovarian stimulation with medication that may or may not include administration of exogenous gonadotropins, followed by oocyte retrieval and embryo transfer. Not every patient beginning a cycle will undergo an oocyte retrieval and not all patients who undergo oocyte retrieval have an embryo transfer. The live-birth rates (LBR) for each of these steps of progression in the ART process are available in the SART and CDC reports.

In 2016, SART recognized that practices were foregoing fresh embryo transfer after oocyte retrieval, opting to cryopreserve all embryos to either accommodate genetic testing of the embryos prior to transfer or to avoid embryo transfer to an unfavorable uterine environment. In response to changes in practice and in an effort to deemphasize live birth per transfer, thereby alleviating a potential motivator or pressure for practitioners to transfer multiple embryos, SART moved to a report that displays the cumulative live-birth rate per cycle start for oocyte retrieval. The cumulative live-birth rate per cycle start for oocyte retrieval is the chance of live birth from transfers of embryos derived from the oocyte retrieval and performed within 1 year of the oocyte retrieval.

This change in reporting further reduced the pressure to transfer multiple embryos and encouraged elective, single-embryo transfer. The outcome per transfer is no longer the report’s primary focus.

Q: The latest pregnancy outcomes statistics are from the year 2020 and are finalized by the CDC. Why does the SART website have this same year labeled “preliminary” outcomes?

A: Shortly after the 2016 SART report change, the CDC made similar changes to their report. The difference is that SART provides a “preliminary” report of outcomes within the year of the cycle start for oocyte retrieval. The cumulative outcome is not “finalized” until the following year as transfers may be performed as late as 12 months after the oocyte retrieval.

SART has opted to report both the “preliminary” or interim outcome and the “final” outcome a year later. The CDC has opted to limit their report to “final” outcomes. I’m happy to report that SART recently released the final report for 2021 cycles.

Q: Have national success rates in the United States continued to rise or have they plateaued?

A: It appears that success rates have plateaued; however, we find ourselves at another point where practice patterns and patients’ approach to using ART for family building have changed.

Recognizing the impact of maternal aging on reproductive potential, patients are opting to undergo multiple ART cycles to cryopreserve embryos for family building before they attempt to get pregnant. This family-building path reduces the value of measuring the LBR per cycle start as we may not know the outcome for many years. SART leaders are deliberating intently as to how to best represent this growing patient population in outcome reporting.

Q: Can you comment on the reduction of multiple gestations with the increasing use of single-embryo transfer?

A: The reduction in emphasis on live births per transfer, emphasis on singleton live-birth rates in both the SART and CDC reports, and American Society for Reproductive Medicine practice committee guidelines strongly supporting single embryo transfer have significantly reduced the rate of multiple gestations.

A decade ago, only a third of the transfers were single-embryo transfers and over 25% of live births resulted in a multiple birth. Today, the majority of embryo transfers are elective, single-embryo transfers, and the multiple birth rate has been reduced by nearly 80%. In 2020, 93% of live births from IVF were singletons.

Q: SART offers an online IVF calculator so both patients and physicians can plug in data for an approximate cumulative success rate for up to three IVF cycles. The calculator pools data from all U.S.-reporting IVF centers. Can you explain what an “IVF cycle” is and what patient information is required? Why do success rates increase over time?

A: Each “IVF cycle” is a cycle start for an oocyte retrieval and all transfers of embryos from that cycle within a year of the oocyte retrieval. If the first cycle and subsequent transfers do not lead to a live birth, patients still have a chance to achieve a live birth with a second or third cycle. The success rate increases over time as it reflects the chance of success for a population of patients, with some achieving a live birth after the first cycle and additional patients who achieve success following their third cycle.

Q: The SART IVF calculator can be used with no prior IVF cycles or following an unsuccessful cycle. Are there data to support an estimation of outcome following two or even more unsuccessful cycles?

A: The variables in the SART IVF calculator are based upon the cycle-specific data from patients seeking care at SART member clinics. The current predictor was built with data from cycles performed in 2015-2016. SART is adjusting the predictor and developing a calculator that will be routinely updated, accordingly.

Q: Only approximately 40% of states have some form of infertility coverage law in place; however the number of IVF cycles in the United States continues to increase on an annual basis. What do you think are the driving factors behind this?

A: Advocacy efforts to improve patients’ access to infertility care have included giving patients tools to encourage their employers to include infertility care in their health care benefits package. More recently, the “Great Resignation” has led to the “Great Recruitment” and employers are recognizing that the addition of infertility care to health care benefits is a powerful recruitment tool.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

The field of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) continues to evolve from its first successful birth in 1978 in England, and then in 1981 in the United States. Over the last 6 years, the total number of cycles in the U.S. has increased by 44% to nearly 370,000.

SART membership consists of more than 350 clinics throughout the United States, representing 80% of ART clinics. Over 95% of ART cycles in 2021 in the United States were performed in SART-member clinics.

SART is an invaluable resource for both patients and physicians. Their website includes a “Predict My Success” calculator that allows patients and physicians to enter individualized data to calculate the chance of having a baby over one or more complete cycles of IVF. To help us understand the pregnancy outcome data from ART – cycles per clinic along with national results – I posed the questions below to Amy Sparks, PhD, HCLD, director of the IVF and Andrology Laboratories and the Center for Advanced Reproductive Care at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City. Dr. Sparks is past president of SART and former chairperson of the SART Registry committee when the current Clinic Summary Report format was initially released.

Question: The Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act (FCSRCA) of 1992 mandated that all ART clinics report success rate data to the federal government, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a standardized manner. As ART is the only field in medicine to be required to annually report their patient outcomes, that is, all initiated cycles and live births, why do you believe this law was enacted and is limited to reproductive medicine?

Answer: The FCSRCA of 1992 was enacted in response to the lack of open and reliable pregnancy success rate information for patients seeking infertility care using assisted reproductive technologies. Success rates of 25%-50% were being advertised by independent clinics when, nationally, fewer than 15% of ART procedures led to live births. The Federal Trade Commission said such claims were deceptive and filed charges against five clinics, saying they misrepresented their success in helping women become pregnant. The government won one case by court order and the other four cases were settled out of court.

This field of medicine was in the spotlight as the majority of patients lacked insurance coverage for their ART cycles, and there was a strong desire to protect consumers paying out of pocket for relatively low success. Recognizing that the FTC’s mission is to ensure truth in advertising and not regulate medical care, Congress passed the FCSRCA, mandating that all centers providing ART services report all initiated cycles and their outcomes. The CDC was appointed as the agency responsible for collecting cycle data and reporting outcomes. Centers not reporting their cycles are listed as nonreporting centers.

This act also established standards for accreditation of embryology laboratories including personnel and traditional clinical laboratory management requirements. These standards serve as the foundation for embryology laboratory accrediting agencies.

Q: Why have live-birth rates on SART appeared to be focused on “per IVF cycle” as opposed to the CDC reporting of live births “per embryo transfer?”

A: An ART cycle “start” is defined as the initiation of ovarian stimulation with medication that may or may not include administration of exogenous gonadotropins, followed by oocyte retrieval and embryo transfer. Not every patient beginning a cycle will undergo an oocyte retrieval and not all patients who undergo oocyte retrieval have an embryo transfer. The live-birth rates (LBR) for each of these steps of progression in the ART process are available in the SART and CDC reports.

In 2016, SART recognized that practices were foregoing fresh embryo transfer after oocyte retrieval, opting to cryopreserve all embryos to either accommodate genetic testing of the embryos prior to transfer or to avoid embryo transfer to an unfavorable uterine environment. In response to changes in practice and in an effort to deemphasize live birth per transfer, thereby alleviating a potential motivator or pressure for practitioners to transfer multiple embryos, SART moved to a report that displays the cumulative live-birth rate per cycle start for oocyte retrieval. The cumulative live-birth rate per cycle start for oocyte retrieval is the chance of live birth from transfers of embryos derived from the oocyte retrieval and performed within 1 year of the oocyte retrieval.

This change in reporting further reduced the pressure to transfer multiple embryos and encouraged elective, single-embryo transfer. The outcome per transfer is no longer the report’s primary focus.

Q: The latest pregnancy outcomes statistics are from the year 2020 and are finalized by the CDC. Why does the SART website have this same year labeled “preliminary” outcomes?

A: Shortly after the 2016 SART report change, the CDC made similar changes to their report. The difference is that SART provides a “preliminary” report of outcomes within the year of the cycle start for oocyte retrieval. The cumulative outcome is not “finalized” until the following year as transfers may be performed as late as 12 months after the oocyte retrieval.

SART has opted to report both the “preliminary” or interim outcome and the “final” outcome a year later. The CDC has opted to limit their report to “final” outcomes. I’m happy to report that SART recently released the final report for 2021 cycles.

Q: Have national success rates in the United States continued to rise or have they plateaued?

A: It appears that success rates have plateaued; however, we find ourselves at another point where practice patterns and patients’ approach to using ART for family building have changed.

Recognizing the impact of maternal aging on reproductive potential, patients are opting to undergo multiple ART cycles to cryopreserve embryos for family building before they attempt to get pregnant. This family-building path reduces the value of measuring the LBR per cycle start as we may not know the outcome for many years. SART leaders are deliberating intently as to how to best represent this growing patient population in outcome reporting.

Q: Can you comment on the reduction of multiple gestations with the increasing use of single-embryo transfer?

A: The reduction in emphasis on live births per transfer, emphasis on singleton live-birth rates in both the SART and CDC reports, and American Society for Reproductive Medicine practice committee guidelines strongly supporting single embryo transfer have significantly reduced the rate of multiple gestations.

A decade ago, only a third of the transfers were single-embryo transfers and over 25% of live births resulted in a multiple birth. Today, the majority of embryo transfers are elective, single-embryo transfers, and the multiple birth rate has been reduced by nearly 80%. In 2020, 93% of live births from IVF were singletons.

Q: SART offers an online IVF calculator so both patients and physicians can plug in data for an approximate cumulative success rate for up to three IVF cycles. The calculator pools data from all U.S.-reporting IVF centers. Can you explain what an “IVF cycle” is and what patient information is required? Why do success rates increase over time?

A: Each “IVF cycle” is a cycle start for an oocyte retrieval and all transfers of embryos from that cycle within a year of the oocyte retrieval. If the first cycle and subsequent transfers do not lead to a live birth, patients still have a chance to achieve a live birth with a second or third cycle. The success rate increases over time as it reflects the chance of success for a population of patients, with some achieving a live birth after the first cycle and additional patients who achieve success following their third cycle.

Q: The SART IVF calculator can be used with no prior IVF cycles or following an unsuccessful cycle. Are there data to support an estimation of outcome following two or even more unsuccessful cycles?

A: The variables in the SART IVF calculator are based upon the cycle-specific data from patients seeking care at SART member clinics. The current predictor was built with data from cycles performed in 2015-2016. SART is adjusting the predictor and developing a calculator that will be routinely updated, accordingly.

Q: Only approximately 40% of states have some form of infertility coverage law in place; however the number of IVF cycles in the United States continues to increase on an annual basis. What do you think are the driving factors behind this?

A: Advocacy efforts to improve patients’ access to infertility care have included giving patients tools to encourage their employers to include infertility care in their health care benefits package. More recently, the “Great Resignation” has led to the “Great Recruitment” and employers are recognizing that the addition of infertility care to health care benefits is a powerful recruitment tool.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

The field of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) continues to evolve from its first successful birth in 1978 in England, and then in 1981 in the United States. Over the last 6 years, the total number of cycles in the U.S. has increased by 44% to nearly 370,000.

SART membership consists of more than 350 clinics throughout the United States, representing 80% of ART clinics. Over 95% of ART cycles in 2021 in the United States were performed in SART-member clinics.

SART is an invaluable resource for both patients and physicians. Their website includes a “Predict My Success” calculator that allows patients and physicians to enter individualized data to calculate the chance of having a baby over one or more complete cycles of IVF. To help us understand the pregnancy outcome data from ART – cycles per clinic along with national results – I posed the questions below to Amy Sparks, PhD, HCLD, director of the IVF and Andrology Laboratories and the Center for Advanced Reproductive Care at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City. Dr. Sparks is past president of SART and former chairperson of the SART Registry committee when the current Clinic Summary Report format was initially released.

Question: The Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act (FCSRCA) of 1992 mandated that all ART clinics report success rate data to the federal government, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a standardized manner. As ART is the only field in medicine to be required to annually report their patient outcomes, that is, all initiated cycles and live births, why do you believe this law was enacted and is limited to reproductive medicine?

Answer: The FCSRCA of 1992 was enacted in response to the lack of open and reliable pregnancy success rate information for patients seeking infertility care using assisted reproductive technologies. Success rates of 25%-50% were being advertised by independent clinics when, nationally, fewer than 15% of ART procedures led to live births. The Federal Trade Commission said such claims were deceptive and filed charges against five clinics, saying they misrepresented their success in helping women become pregnant. The government won one case by court order and the other four cases were settled out of court.

This field of medicine was in the spotlight as the majority of patients lacked insurance coverage for their ART cycles, and there was a strong desire to protect consumers paying out of pocket for relatively low success. Recognizing that the FTC’s mission is to ensure truth in advertising and not regulate medical care, Congress passed the FCSRCA, mandating that all centers providing ART services report all initiated cycles and their outcomes. The CDC was appointed as the agency responsible for collecting cycle data and reporting outcomes. Centers not reporting their cycles are listed as nonreporting centers.

This act also established standards for accreditation of embryology laboratories including personnel and traditional clinical laboratory management requirements. These standards serve as the foundation for embryology laboratory accrediting agencies.

Q: Why have live-birth rates on SART appeared to be focused on “per IVF cycle” as opposed to the CDC reporting of live births “per embryo transfer?”

A: An ART cycle “start” is defined as the initiation of ovarian stimulation with medication that may or may not include administration of exogenous gonadotropins, followed by oocyte retrieval and embryo transfer. Not every patient beginning a cycle will undergo an oocyte retrieval and not all patients who undergo oocyte retrieval have an embryo transfer. The live-birth rates (LBR) for each of these steps of progression in the ART process are available in the SART and CDC reports.

In 2016, SART recognized that practices were foregoing fresh embryo transfer after oocyte retrieval, opting to cryopreserve all embryos to either accommodate genetic testing of the embryos prior to transfer or to avoid embryo transfer to an unfavorable uterine environment. In response to changes in practice and in an effort to deemphasize live birth per transfer, thereby alleviating a potential motivator or pressure for practitioners to transfer multiple embryos, SART moved to a report that displays the cumulative live-birth rate per cycle start for oocyte retrieval. The cumulative live-birth rate per cycle start for oocyte retrieval is the chance of live birth from transfers of embryos derived from the oocyte retrieval and performed within 1 year of the oocyte retrieval.

This change in reporting further reduced the pressure to transfer multiple embryos and encouraged elective, single-embryo transfer. The outcome per transfer is no longer the report’s primary focus.

Q: The latest pregnancy outcomes statistics are from the year 2020 and are finalized by the CDC. Why does the SART website have this same year labeled “preliminary” outcomes?

A: Shortly after the 2016 SART report change, the CDC made similar changes to their report. The difference is that SART provides a “preliminary” report of outcomes within the year of the cycle start for oocyte retrieval. The cumulative outcome is not “finalized” until the following year as transfers may be performed as late as 12 months after the oocyte retrieval.

SART has opted to report both the “preliminary” or interim outcome and the “final” outcome a year later. The CDC has opted to limit their report to “final” outcomes. I’m happy to report that SART recently released the final report for 2021 cycles.

Q: Have national success rates in the United States continued to rise or have they plateaued?

A: It appears that success rates have plateaued; however, we find ourselves at another point where practice patterns and patients’ approach to using ART for family building have changed.

Recognizing the impact of maternal aging on reproductive potential, patients are opting to undergo multiple ART cycles to cryopreserve embryos for family building before they attempt to get pregnant. This family-building path reduces the value of measuring the LBR per cycle start as we may not know the outcome for many years. SART leaders are deliberating intently as to how to best represent this growing patient population in outcome reporting.

Q: Can you comment on the reduction of multiple gestations with the increasing use of single-embryo transfer?

A: The reduction in emphasis on live births per transfer, emphasis on singleton live-birth rates in both the SART and CDC reports, and American Society for Reproductive Medicine practice committee guidelines strongly supporting single embryo transfer have significantly reduced the rate of multiple gestations.

A decade ago, only a third of the transfers were single-embryo transfers and over 25% of live births resulted in a multiple birth. Today, the majority of embryo transfers are elective, single-embryo transfers, and the multiple birth rate has been reduced by nearly 80%. In 2020, 93% of live births from IVF were singletons.

Q: SART offers an online IVF calculator so both patients and physicians can plug in data for an approximate cumulative success rate for up to three IVF cycles. The calculator pools data from all U.S.-reporting IVF centers. Can you explain what an “IVF cycle” is and what patient information is required? Why do success rates increase over time?

A: Each “IVF cycle” is a cycle start for an oocyte retrieval and all transfers of embryos from that cycle within a year of the oocyte retrieval. If the first cycle and subsequent transfers do not lead to a live birth, patients still have a chance to achieve a live birth with a second or third cycle. The success rate increases over time as it reflects the chance of success for a population of patients, with some achieving a live birth after the first cycle and additional patients who achieve success following their third cycle.

Q: The SART IVF calculator can be used with no prior IVF cycles or following an unsuccessful cycle. Are there data to support an estimation of outcome following two or even more unsuccessful cycles?

A: The variables in the SART IVF calculator are based upon the cycle-specific data from patients seeking care at SART member clinics. The current predictor was built with data from cycles performed in 2015-2016. SART is adjusting the predictor and developing a calculator that will be routinely updated, accordingly.

Q: Only approximately 40% of states have some form of infertility coverage law in place; however the number of IVF cycles in the United States continues to increase on an annual basis. What do you think are the driving factors behind this?

A: Advocacy efforts to improve patients’ access to infertility care have included giving patients tools to encourage their employers to include infertility care in their health care benefits package. More recently, the “Great Resignation” has led to the “Great Recruitment” and employers are recognizing that the addition of infertility care to health care benefits is a powerful recruitment tool.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

Remote weight monitoring minimizes office visits for newborns

WASHINGTON, D.C. – according to a new study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.