User login

Performance Partnership

With 37,000 individual members and nearly 5,000 hospitals and other provider groups on its roster, the American Hospital Association (AHA) is a major player in national healthcare debates and in shaping policies aimed at improving quality.

John Combes, MD, AHA senior vice president and president and chief operating officer of the association-affiliated Center for Healthcare Governance, serves on several national advisory groups on medical ethics, palliative care, and reducing medication errors.

Among his many duties, he is a principal investigator for a national project aimed at reducing hospital-acquired infections called “On the CUSP: Stop Bloodstream Infections,” sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (CUSP is the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, developed by Johns Hopkins University and the Michigan Hospital Association.)

Dr. Combes recently talked with The Hospitalist about the AHA’s vision for healthcare reform, integrated care, and the role of hospitalists in redesigning hospital-based care.

Question: What are the AHA’s biggest priorities over the next year?

Answer: Healthcare reform and making sure that we can increase coverage for patients without insurance. There are 48 million uninsured in this country, and we are very supportive of increasing that coverage to make sure that people have good access to healthcare.

Q: The AHA has stated that “clinical integration holds the promise of greater quality and improved efficiency in delivering patient-centered care.” What’s your vision for clinical integration?

A: What we recognize is that in a reformed delivery system, we have to have a lot of partnerships between hospitals and clinicians—physicians in particular—and between hospitals and other facilities, such as long-term care facilities and post-acute facilities. We need to be able to bring better-coordinated care that meets the patient’s needs, and we need to work with each other to constantly improve that care. So that’s why we’re looking at an integrated delivery system. In our minds, it really means one registration, one bill, one experience for the patient.

Practically speaking, if you look at the healthcare reform legislation … there are pilots in there for accountable-care organizations (ACOs) and other payment reforms. And we’re very interested in making sure that hospitals can participate and take a leadership role in the development of those kinds of new structures.

Q: What role do you expect hospitalists to play in the continued drive for higher quality and more efficient care?

A: I think hospitalists can become a critical partner with the hospital in helping us redesign inpatient care to make it more efficient and effective. Additionally, hospitalists have a key role in engaging and keeping involved the community-based PCP, and making sure that they are considered part of the care team, even though they may not be present in the hospital, since they have the continuing responsibility for the patient.

I think as we look at other models of care delivery, such as the patient-centered medical home, it’s critical that hospitalists really develop some strong relationships and communication networks with those groups as well, so that the care for the patient can become seamless and transitions are not as dangerous as they’ve been in the past, in terms of missed opportunities and missed handoffs.

Q: What are the necessary ingredients for any successful quality incentive payment program?

A: One of our big concerns is that there are lots of regulatory obstacles to true integration, where you can design some of those payment structures in terms of gainsharing and also in terms of payment for high-level-quality performance. One of the concerns of the AHM is to make sure that as we pursue these new models of care that require high levels of integration, we also look at some regulatory relief.

The promise is that if we can integrate the delivery system, we can then get focused on improving care and then rewarding high-quality delivery of care. And that can come through incentive programs or pay-for-performance programs and things of that nature that can be worked out between the hospitals and the physicians.

Q: What can be done to reduce the rates of hospital-acquired infections?

A: The idea of CUSP is that you create teams and a culture on units that will then implement the evidence-based intervention—in this case, eliminating central-line infections.

Hospitalists can play a critical role in helping create that culture of mutual accountability at the team level [and] holding each other accountable to use the evidence-based techniques for, in this case, line insertion, or for any kind of safety intervention. I think eliminating infections is a goal that’s achievable. I think we have come to the understanding over the last five or so years that these complications are avoidable in many, many cases, and that it takes teamwork, communication, and use of evidence-based procedures to get the work done.

Q: What can be done to help reduce preventable hospital readmissions?

A: There are so many things that go into readmissions. And the issue is: What is truly preventable in terms of treatments within the hospital, the coordination of discharge, and aftercare followup? A lot of readmissions are related to social determinants of health. And those have to do with people’s ability to afford their medications, people’s ability to access care, people’s home environment, and things of that nature. It’s going to take an approach by hospitals on those things that are controllable in partnerships with the physicians. But for many, many readmissions, it’s related to other issues that we as a society really have to hold ourselves accountable to.

Q: Some critics have charged that the overuse of medical technology is helping to drive up healthcare costs. Would there be more of a role for hospitals in decision-making about the appropriateness of tests within a model like an ACO?

A: In an ACO, that’s a partnership between hospitals and physicians operating as one entity. So that’s the difference, because there, everybody is aligned to make sure that we deliver the most effective care. There’s going to be much more time spent on physicians ordering the most appropriate technology or treatments for that condition that will deliver value to the patient and to the payor of that care.

But that’s in a totally integrated system. Right now we don’t have that. So where the interests of the physicians may be different from the interests of the hospital and the intentions are not aligned, it’s very hard to get at talking about what’s the most effective care.

Q: Is there a measure that hasn’t received as much attention that you would like to see more focus on to help improve the quality or cost-effectiveness of healthcare?

A: I think the one area that we’re always challenged with—and I think we’ve seen it in the healthcare debate, and I think it’s an appropriate role for us as healthcare providers to pay attention to—is palliative and end-of-life care. I don’t think we’ve done enough work, as a profession, to make sure that we deliver very-high-quality care of patients with chronic and acute catastrophic illnesses.

We need to better understand what the needs of those patients are, to ask them to work with us to set the goals with them, what they want from us.

So I think it’s an opportunity for us to have a real partnership with patients at a critical time in their lives. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

With 37,000 individual members and nearly 5,000 hospitals and other provider groups on its roster, the American Hospital Association (AHA) is a major player in national healthcare debates and in shaping policies aimed at improving quality.

John Combes, MD, AHA senior vice president and president and chief operating officer of the association-affiliated Center for Healthcare Governance, serves on several national advisory groups on medical ethics, palliative care, and reducing medication errors.

Among his many duties, he is a principal investigator for a national project aimed at reducing hospital-acquired infections called “On the CUSP: Stop Bloodstream Infections,” sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (CUSP is the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, developed by Johns Hopkins University and the Michigan Hospital Association.)

Dr. Combes recently talked with The Hospitalist about the AHA’s vision for healthcare reform, integrated care, and the role of hospitalists in redesigning hospital-based care.

Question: What are the AHA’s biggest priorities over the next year?

Answer: Healthcare reform and making sure that we can increase coverage for patients without insurance. There are 48 million uninsured in this country, and we are very supportive of increasing that coverage to make sure that people have good access to healthcare.

Q: The AHA has stated that “clinical integration holds the promise of greater quality and improved efficiency in delivering patient-centered care.” What’s your vision for clinical integration?

A: What we recognize is that in a reformed delivery system, we have to have a lot of partnerships between hospitals and clinicians—physicians in particular—and between hospitals and other facilities, such as long-term care facilities and post-acute facilities. We need to be able to bring better-coordinated care that meets the patient’s needs, and we need to work with each other to constantly improve that care. So that’s why we’re looking at an integrated delivery system. In our minds, it really means one registration, one bill, one experience for the patient.

Practically speaking, if you look at the healthcare reform legislation … there are pilots in there for accountable-care organizations (ACOs) and other payment reforms. And we’re very interested in making sure that hospitals can participate and take a leadership role in the development of those kinds of new structures.

Q: What role do you expect hospitalists to play in the continued drive for higher quality and more efficient care?

A: I think hospitalists can become a critical partner with the hospital in helping us redesign inpatient care to make it more efficient and effective. Additionally, hospitalists have a key role in engaging and keeping involved the community-based PCP, and making sure that they are considered part of the care team, even though they may not be present in the hospital, since they have the continuing responsibility for the patient.

I think as we look at other models of care delivery, such as the patient-centered medical home, it’s critical that hospitalists really develop some strong relationships and communication networks with those groups as well, so that the care for the patient can become seamless and transitions are not as dangerous as they’ve been in the past, in terms of missed opportunities and missed handoffs.

Q: What are the necessary ingredients for any successful quality incentive payment program?

A: One of our big concerns is that there are lots of regulatory obstacles to true integration, where you can design some of those payment structures in terms of gainsharing and also in terms of payment for high-level-quality performance. One of the concerns of the AHM is to make sure that as we pursue these new models of care that require high levels of integration, we also look at some regulatory relief.

The promise is that if we can integrate the delivery system, we can then get focused on improving care and then rewarding high-quality delivery of care. And that can come through incentive programs or pay-for-performance programs and things of that nature that can be worked out between the hospitals and the physicians.

Q: What can be done to reduce the rates of hospital-acquired infections?

A: The idea of CUSP is that you create teams and a culture on units that will then implement the evidence-based intervention—in this case, eliminating central-line infections.

Hospitalists can play a critical role in helping create that culture of mutual accountability at the team level [and] holding each other accountable to use the evidence-based techniques for, in this case, line insertion, or for any kind of safety intervention. I think eliminating infections is a goal that’s achievable. I think we have come to the understanding over the last five or so years that these complications are avoidable in many, many cases, and that it takes teamwork, communication, and use of evidence-based procedures to get the work done.

Q: What can be done to help reduce preventable hospital readmissions?

A: There are so many things that go into readmissions. And the issue is: What is truly preventable in terms of treatments within the hospital, the coordination of discharge, and aftercare followup? A lot of readmissions are related to social determinants of health. And those have to do with people’s ability to afford their medications, people’s ability to access care, people’s home environment, and things of that nature. It’s going to take an approach by hospitals on those things that are controllable in partnerships with the physicians. But for many, many readmissions, it’s related to other issues that we as a society really have to hold ourselves accountable to.

Q: Some critics have charged that the overuse of medical technology is helping to drive up healthcare costs. Would there be more of a role for hospitals in decision-making about the appropriateness of tests within a model like an ACO?

A: In an ACO, that’s a partnership between hospitals and physicians operating as one entity. So that’s the difference, because there, everybody is aligned to make sure that we deliver the most effective care. There’s going to be much more time spent on physicians ordering the most appropriate technology or treatments for that condition that will deliver value to the patient and to the payor of that care.

But that’s in a totally integrated system. Right now we don’t have that. So where the interests of the physicians may be different from the interests of the hospital and the intentions are not aligned, it’s very hard to get at talking about what’s the most effective care.

Q: Is there a measure that hasn’t received as much attention that you would like to see more focus on to help improve the quality or cost-effectiveness of healthcare?

A: I think the one area that we’re always challenged with—and I think we’ve seen it in the healthcare debate, and I think it’s an appropriate role for us as healthcare providers to pay attention to—is palliative and end-of-life care. I don’t think we’ve done enough work, as a profession, to make sure that we deliver very-high-quality care of patients with chronic and acute catastrophic illnesses.

We need to better understand what the needs of those patients are, to ask them to work with us to set the goals with them, what they want from us.

So I think it’s an opportunity for us to have a real partnership with patients at a critical time in their lives. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

With 37,000 individual members and nearly 5,000 hospitals and other provider groups on its roster, the American Hospital Association (AHA) is a major player in national healthcare debates and in shaping policies aimed at improving quality.

John Combes, MD, AHA senior vice president and president and chief operating officer of the association-affiliated Center for Healthcare Governance, serves on several national advisory groups on medical ethics, palliative care, and reducing medication errors.

Among his many duties, he is a principal investigator for a national project aimed at reducing hospital-acquired infections called “On the CUSP: Stop Bloodstream Infections,” sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (CUSP is the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, developed by Johns Hopkins University and the Michigan Hospital Association.)

Dr. Combes recently talked with The Hospitalist about the AHA’s vision for healthcare reform, integrated care, and the role of hospitalists in redesigning hospital-based care.

Question: What are the AHA’s biggest priorities over the next year?

Answer: Healthcare reform and making sure that we can increase coverage for patients without insurance. There are 48 million uninsured in this country, and we are very supportive of increasing that coverage to make sure that people have good access to healthcare.

Q: The AHA has stated that “clinical integration holds the promise of greater quality and improved efficiency in delivering patient-centered care.” What’s your vision for clinical integration?

A: What we recognize is that in a reformed delivery system, we have to have a lot of partnerships between hospitals and clinicians—physicians in particular—and between hospitals and other facilities, such as long-term care facilities and post-acute facilities. We need to be able to bring better-coordinated care that meets the patient’s needs, and we need to work with each other to constantly improve that care. So that’s why we’re looking at an integrated delivery system. In our minds, it really means one registration, one bill, one experience for the patient.

Practically speaking, if you look at the healthcare reform legislation … there are pilots in there for accountable-care organizations (ACOs) and other payment reforms. And we’re very interested in making sure that hospitals can participate and take a leadership role in the development of those kinds of new structures.

Q: What role do you expect hospitalists to play in the continued drive for higher quality and more efficient care?

A: I think hospitalists can become a critical partner with the hospital in helping us redesign inpatient care to make it more efficient and effective. Additionally, hospitalists have a key role in engaging and keeping involved the community-based PCP, and making sure that they are considered part of the care team, even though they may not be present in the hospital, since they have the continuing responsibility for the patient.

I think as we look at other models of care delivery, such as the patient-centered medical home, it’s critical that hospitalists really develop some strong relationships and communication networks with those groups as well, so that the care for the patient can become seamless and transitions are not as dangerous as they’ve been in the past, in terms of missed opportunities and missed handoffs.

Q: What are the necessary ingredients for any successful quality incentive payment program?

A: One of our big concerns is that there are lots of regulatory obstacles to true integration, where you can design some of those payment structures in terms of gainsharing and also in terms of payment for high-level-quality performance. One of the concerns of the AHM is to make sure that as we pursue these new models of care that require high levels of integration, we also look at some regulatory relief.

The promise is that if we can integrate the delivery system, we can then get focused on improving care and then rewarding high-quality delivery of care. And that can come through incentive programs or pay-for-performance programs and things of that nature that can be worked out between the hospitals and the physicians.

Q: What can be done to reduce the rates of hospital-acquired infections?

A: The idea of CUSP is that you create teams and a culture on units that will then implement the evidence-based intervention—in this case, eliminating central-line infections.

Hospitalists can play a critical role in helping create that culture of mutual accountability at the team level [and] holding each other accountable to use the evidence-based techniques for, in this case, line insertion, or for any kind of safety intervention. I think eliminating infections is a goal that’s achievable. I think we have come to the understanding over the last five or so years that these complications are avoidable in many, many cases, and that it takes teamwork, communication, and use of evidence-based procedures to get the work done.

Q: What can be done to help reduce preventable hospital readmissions?

A: There are so many things that go into readmissions. And the issue is: What is truly preventable in terms of treatments within the hospital, the coordination of discharge, and aftercare followup? A lot of readmissions are related to social determinants of health. And those have to do with people’s ability to afford their medications, people’s ability to access care, people’s home environment, and things of that nature. It’s going to take an approach by hospitals on those things that are controllable in partnerships with the physicians. But for many, many readmissions, it’s related to other issues that we as a society really have to hold ourselves accountable to.

Q: Some critics have charged that the overuse of medical technology is helping to drive up healthcare costs. Would there be more of a role for hospitals in decision-making about the appropriateness of tests within a model like an ACO?

A: In an ACO, that’s a partnership between hospitals and physicians operating as one entity. So that’s the difference, because there, everybody is aligned to make sure that we deliver the most effective care. There’s going to be much more time spent on physicians ordering the most appropriate technology or treatments for that condition that will deliver value to the patient and to the payor of that care.

But that’s in a totally integrated system. Right now we don’t have that. So where the interests of the physicians may be different from the interests of the hospital and the intentions are not aligned, it’s very hard to get at talking about what’s the most effective care.

Q: Is there a measure that hasn’t received as much attention that you would like to see more focus on to help improve the quality or cost-effectiveness of healthcare?

A: I think the one area that we’re always challenged with—and I think we’ve seen it in the healthcare debate, and I think it’s an appropriate role for us as healthcare providers to pay attention to—is palliative and end-of-life care. I don’t think we’ve done enough work, as a profession, to make sure that we deliver very-high-quality care of patients with chronic and acute catastrophic illnesses.

We need to better understand what the needs of those patients are, to ask them to work with us to set the goals with them, what they want from us.

So I think it’s an opportunity for us to have a real partnership with patients at a critical time in their lives. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine

Some in her HM group think Cathleen Ammann, MD, is the guinea pig. Dr. Ammann, the medical director of the hospital medicine division at Wentworth-Douglass Hospital in Dover, N.H., will be one of the first to complete her American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) through the new Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) pathway. Dr. Ammann—and the hospital administration—sees things a little differently.

“Am I the guinea pig or a pioneer?” a hospitalist in Dr. Ammann’s group asked her recently. “I definitely see it as being a pioneer. When you look back in another 10 years, hospital medicine might be a specialty with its own certification. I know it’s a little corny, but I look forward to getting in on that at the ground floor.”

Dr. Ammann is one of about 175 hospitalists who have signed up to recertify through FPHM. Her internal-medicine (IM) certification expires at the end of the year, so she will be taking the recertification exam Oct. 25.

“I hope the test focuses more on what I’m doing … stroke, quality measures,” she says. “Hospitalists know that stuff like the back of our hand. … I think it will work out well for me, but I also think it will be great for our program to have a director who has a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine. It shows my commitment, and we can hold that up to the rest of the organization and say we really have someone who is concentrated in this field.”

Dr. Ammann sums up the thinking of many HM leaders who’ve been working with ABIM and the American Board of Medical Specialties to launch the MOC pathway for hospitalists: Not only does a focused practice certification allow the more than 30,000 hospitalists in the U.S. to define themselves as different, it also provides hospitalists an MOC process and secured examination more acutely tailored to their skill sets and daily practice. The new pathway also requires ACLS certification and stresses continued “maintenance of competency,” according to SHM leaders, through a triennial self-evaluation requirement (60 self-evaluation points, with at least 20 points from medical knowledge modules and 40 points from completion of practice performance modules). The traditional IM MOC requires a practice-improvement module (PIM) every 10 years.

“The process will ask diplomates to participate in practice improvement every three years, which will focus on the ongoing need for performance improvement,” says Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, SHM president and chair of the ABIM Hospital Medicine MOC Question Writing Committee. “It will separate out the authentic hospitalist who is representing the goals and virtues that we are espousing as a society, particularly with regards to quality healthcare and safe healthcare. But I also think there are unique benefits for the patient that will be receiving the healthcare, because through this process, I believe, every diplomate will be a better hospitalist as a product of having done it.”

Here’s a brief look at what hospitalists interested in the FPHM MOC can expect:

The Process and Timeline

ABIM and SHM began working toward an HM-focused pathway about five years ago, and the two groups announced the FPHM program in September 2009. ABIM is in the process of retooling its website for the new MOC pathway. The entry system—to sign up and begin the MOC’s attestation process—was made public in March. The registration interface for the secure exam opened to the hospitalist community May 1, says Eric Holmboe, MD, ABIM’s chief medical officer.

“Diplomates can signify their interest and start the attestation process, which will allow them to get formal entry into the pathway,” Dr. Holmboe says. “Once they receive the attestation confirmation back, they can start doing the requirements around the medical knowledge and performance and practice requirements. Those are all available on the website. … We’re excited. The first phase of the project is live. This is a brand-new pathway for MOC, and we’re really hopeful people will find it valuable and useful.”

Board recertification is no easy task, and prospective diplomates should organize a plan of attack based upon individual workloads and regular involvement in performance-improvement programs. Some hospitalists will only need six to nine months to complete all the requirements and take the exam; others might take a conservative approach and need one to two years.

“Eighteen months is very reasonable,” Dr. Holmboe says. “Because of the 40-point requirement for the evaluation of performance and practice, that means you have to do the hospital-based PIM or self-directed PIM, or some combination thereof, twice. So if you haven’t been active in QI projects in your hospital, you really need to get going.”

Some hospitalists and HM groups work on quality-improvement (QI) projects regularly. Dr. Ammann plans to use a recent QI project looking at her group’s compliance with antibiotic selection for pneumonia to satisfy one of her required PIMs.

“[The three-year] requirement should be easy for directors because we’re always doing that kind of work anyway,” she says. “We just finished a project where we had to improve our compliance with antibiotic selection. We looked at our processes and found that our pathway wasn’t clear, and it could be interpreted a couple different ways. So our chief of medicine and I just changed the pathway, put it out there, and since then, our compliance has consistently been 100%.

We have two quarters of data, and I’m going to use that for my PIM, which is nice, because it’s done.”

For hospitalists whose certification runs out in 2011 or beyond, Dr. Holmboe suggests the following timeline:

Now through end of 2010

- Register for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine MOC pathway on ABIM’ website (www.abim.org/moc/policies. aspx);

- Complete the attestation process;

- Get involved in an appropriate (hospital-based) performance-improvement activity; and

- Complete Update in Hospital Medicine using ABIM or ACP medical education modules.

—Cathleen Ammann, MD, medical director, hospital medicine division, Wentworth-Douglass Hospital, Dover, N.H.

First six months of 2011

- Complete the next yearly Update in HM module;

- Develop a strategy to prepare for the exam, which is given in the fall; and

- Plan and complete your second performance improvement activity.

Second half of 2011

- Prepare for the exam; and

- Pass the exam.

Start Process Now, Start Earning Points

ABIM is encouraging prospective FPHM diplomates to begin working on medical-knowledge modules. Most are designed to “stretch folks and to get them to look things up.”

“ACP, to their credit, also has hospital-based modules,” Dr. Holmboe says. “So if somebody is a dual member, they can certainly use the ACP’s MKSAP (Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program) hospital-based modules as well. We’re also working with SHM, looking for areas they might fill in around knowledge and updates—things that could be brought into the program over time.”

In regard to the evaluation and performance modules, ABIM offers three main pathways, including the Hospital-Based PIM, which targets core measure sets like community-acquired pneumonia and congestive heart failure and DVT prophylaxis. “Hospitalists can use those PIMs to start a quality-improvement program, or they can use it to report on one they are working on,” Dr. Holmboe says, adding the Hospital Based PIM’s online module will be redesigned this summer to improve the user experience.

Two other approaches are the Self-Directed PIM and the Accepted Quality Improvement programs. “That would be for hospitalists who may not be working on the core measure sets in the hospital-based PIM, but are still important,” he says. “They can use that module to report on those activities and get the points they need.”

Dr. Holmboe also points out that diplomates do not have to complete all the other requirements before they take the exam. “Some people get confused; you don’t have to cram in the 100 points before the exam,” Dr. Holmboe explains. He notes that the exam can, for example, be taken this year and the remainder of the requirements completed at a later date.

“If it was up to me, you should do a [PIM] every year,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, SFHM, CEO of SHM and one of the architects of the new FPHM pathway. “If you are a real hospitalist, completing a PIM every three years shouldn’t be a big deal. You should be able to say, ‘I’ve looked at 10 things: how I’m doing in pneumonia, how I’m doing in DVT, how I’m doing in glycemic control. This isn’t work for me; it’s part of my workflow.’ It’s like asking a salesman how many sales calls have you made, how many miles have you driven, and how many sales have you closed.”

The Examination

Dr. Wiese, associate dean of Graduate Medical Education and professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, completed his 10-year MOC in 2008, and he says the process made him “a better physician.” As president of SHM and chair of the FPHM test-writing committee, he envisions that the new MOC pathway will help “ramp up the quality of care for the hospitalized patient.”

“The FPHM MOC process is much more than just a different exam,” he says. “It is true the secure examination will have a lot more hospital-medicine-patient content focus, but not to the exclusion of ambulatory content.”

—Jeff Wiese, SHM president, ABIM Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Test Writing Committee chair

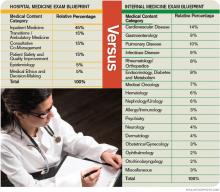

The content-area blueprint (see “Traditional IM Test vs. Focused Practice in HM Test” below) for the FPHM exam includes 15% of questions in the areas of quality and patient safety, along with another 15% in consultative and comanagement topics. Transitions of care and ambulatory questions make up another 15% of the exam.

“If there is one component of the exam that will [be HM-focused], it’s the questions of the exam that are focusing on the core principles of quality and patient safety,” Dr. Wiese says.

That’s music to the ears of many hospitalists—including Dr. Ammann—who know questions about managing cholesterol aren’t relevant to hospitalists. Dr. Ammann was an office-based physician before becoming a hospitalist in 2005. One year later, she was promoted to director of her group, which includes 14 physicians and two nonphysician providers.

“I was really hoping I would be able to [MOC] through the focused practice in HM,” she says. “I did practice office medicine, so I probably have a little advantage. But I was not looking forward to spending time learning and brushing up on things that I am not doing anymore—not only because I’m not doing it anymore, but it would be a waste of time because I’m not going to be doing it, either.”

One of her hospitalist colleagues is taking the traditional IM pathway to MOC, Dr. Ammann says, because “she doesn’t want to limit her scope.” But that’s not how Dr. Ammann sees the FPHM. She is committed to HM and doesn’t have “any problems kissing office medicine goodbye.”

“I think it will work out well for me, but I also think it will be great for our program to have a director who has a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine,” she says. “It shows my commitment, and we can hold that up to the rest of the organization and say we really have someone who is concentrated in this field.”

Educational Efforts

Vikas Parekh, MD, FHM, is in his second year as the chair of SHM’s Education Committee, and says the first task at hand is to educate hospitalists about the new FPHM pathway to MOC. The University of Michigan hospitalist says his committee, working with ABIM and SHM staff, is focused on two major educational efforts: developing the SHM strategy to assist hospitalists with the new FPHM MOC pathway, and “fulfilling the needs of hospitalists, in terms of the resources they have for the MOC process.”

“We’ve already started down this route, in terms of developing resources,” Dr. Parekh says. “We’ve done a few things that have been easy. One is the ABIM learning session pre-course at the annual meeting. … It earns you points toward the medical-knowledge component.”

ABIM and ACP are the traditional avenues for medical-knowledge and practice-improvement requirements for the MOC process. SHM and ABIM currently are working to develop medical-knowledge modules in the domains of patient safety and quality improvement, areas most relevant to HM. Dr. Parekh expects those components to be available in early 2011.

“Practice improvement is likely to be our second main effort,” Dr. Parekh says. “SHM has a lot of resources within our resource rooms that have the shell of what you would really need to meet ABIM requirements for a PIM but aren’t quite complete or thorough enough, or have all the bells and whistles that ABIM wants them to have. … We think we can do a much better job focusing the PIMs to hospitalists.”

At a more granular level, Dr. Wellikson envisions a “suite of products” to assist members in the MOC process. “What we are trying to do is develop resources that help people practice better medicine,” he says, “and while we are helping you practice better medicine, you can also use that to prove to [ABIM] that you have done it.

“So if you log onto the website today and downloaded and completed any of those SHM resource rooms, somewhere in the next several months you will be able to click on a form, enter the results, send it to ABIM, and you’ll have satisfied a PIM,” Dr. Wellikson says. “You can do the work today.”

SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safer Transitions) and Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation programs are prime candidates for Web-based PIMs, according to Dr. Holmboe.

“I think it is still very early, but we are very excited about this,” Dr. Parekh says. “I think a lot of people still have questions about what exactly this mean to me, and why should I recertify through this focused practice as opposed to the traditional general pathway? We hope to change that by making the resources focused to their practice.” TH

Jason Carris is editor of The Hospitalist.

Some in her HM group think Cathleen Ammann, MD, is the guinea pig. Dr. Ammann, the medical director of the hospital medicine division at Wentworth-Douglass Hospital in Dover, N.H., will be one of the first to complete her American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) through the new Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) pathway. Dr. Ammann—and the hospital administration—sees things a little differently.

“Am I the guinea pig or a pioneer?” a hospitalist in Dr. Ammann’s group asked her recently. “I definitely see it as being a pioneer. When you look back in another 10 years, hospital medicine might be a specialty with its own certification. I know it’s a little corny, but I look forward to getting in on that at the ground floor.”

Dr. Ammann is one of about 175 hospitalists who have signed up to recertify through FPHM. Her internal-medicine (IM) certification expires at the end of the year, so she will be taking the recertification exam Oct. 25.

“I hope the test focuses more on what I’m doing … stroke, quality measures,” she says. “Hospitalists know that stuff like the back of our hand. … I think it will work out well for me, but I also think it will be great for our program to have a director who has a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine. It shows my commitment, and we can hold that up to the rest of the organization and say we really have someone who is concentrated in this field.”

Dr. Ammann sums up the thinking of many HM leaders who’ve been working with ABIM and the American Board of Medical Specialties to launch the MOC pathway for hospitalists: Not only does a focused practice certification allow the more than 30,000 hospitalists in the U.S. to define themselves as different, it also provides hospitalists an MOC process and secured examination more acutely tailored to their skill sets and daily practice. The new pathway also requires ACLS certification and stresses continued “maintenance of competency,” according to SHM leaders, through a triennial self-evaluation requirement (60 self-evaluation points, with at least 20 points from medical knowledge modules and 40 points from completion of practice performance modules). The traditional IM MOC requires a practice-improvement module (PIM) every 10 years.

“The process will ask diplomates to participate in practice improvement every three years, which will focus on the ongoing need for performance improvement,” says Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, SHM president and chair of the ABIM Hospital Medicine MOC Question Writing Committee. “It will separate out the authentic hospitalist who is representing the goals and virtues that we are espousing as a society, particularly with regards to quality healthcare and safe healthcare. But I also think there are unique benefits for the patient that will be receiving the healthcare, because through this process, I believe, every diplomate will be a better hospitalist as a product of having done it.”

Here’s a brief look at what hospitalists interested in the FPHM MOC can expect:

The Process and Timeline

ABIM and SHM began working toward an HM-focused pathway about five years ago, and the two groups announced the FPHM program in September 2009. ABIM is in the process of retooling its website for the new MOC pathway. The entry system—to sign up and begin the MOC’s attestation process—was made public in March. The registration interface for the secure exam opened to the hospitalist community May 1, says Eric Holmboe, MD, ABIM’s chief medical officer.

“Diplomates can signify their interest and start the attestation process, which will allow them to get formal entry into the pathway,” Dr. Holmboe says. “Once they receive the attestation confirmation back, they can start doing the requirements around the medical knowledge and performance and practice requirements. Those are all available on the website. … We’re excited. The first phase of the project is live. This is a brand-new pathway for MOC, and we’re really hopeful people will find it valuable and useful.”

Board recertification is no easy task, and prospective diplomates should organize a plan of attack based upon individual workloads and regular involvement in performance-improvement programs. Some hospitalists will only need six to nine months to complete all the requirements and take the exam; others might take a conservative approach and need one to two years.

“Eighteen months is very reasonable,” Dr. Holmboe says. “Because of the 40-point requirement for the evaluation of performance and practice, that means you have to do the hospital-based PIM or self-directed PIM, or some combination thereof, twice. So if you haven’t been active in QI projects in your hospital, you really need to get going.”

Some hospitalists and HM groups work on quality-improvement (QI) projects regularly. Dr. Ammann plans to use a recent QI project looking at her group’s compliance with antibiotic selection for pneumonia to satisfy one of her required PIMs.

“[The three-year] requirement should be easy for directors because we’re always doing that kind of work anyway,” she says. “We just finished a project where we had to improve our compliance with antibiotic selection. We looked at our processes and found that our pathway wasn’t clear, and it could be interpreted a couple different ways. So our chief of medicine and I just changed the pathway, put it out there, and since then, our compliance has consistently been 100%.

We have two quarters of data, and I’m going to use that for my PIM, which is nice, because it’s done.”

For hospitalists whose certification runs out in 2011 or beyond, Dr. Holmboe suggests the following timeline:

Now through end of 2010

- Register for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine MOC pathway on ABIM’ website (www.abim.org/moc/policies. aspx);

- Complete the attestation process;

- Get involved in an appropriate (hospital-based) performance-improvement activity; and

- Complete Update in Hospital Medicine using ABIM or ACP medical education modules.

—Cathleen Ammann, MD, medical director, hospital medicine division, Wentworth-Douglass Hospital, Dover, N.H.

First six months of 2011

- Complete the next yearly Update in HM module;

- Develop a strategy to prepare for the exam, which is given in the fall; and

- Plan and complete your second performance improvement activity.

Second half of 2011

- Prepare for the exam; and

- Pass the exam.

Start Process Now, Start Earning Points

ABIM is encouraging prospective FPHM diplomates to begin working on medical-knowledge modules. Most are designed to “stretch folks and to get them to look things up.”

“ACP, to their credit, also has hospital-based modules,” Dr. Holmboe says. “So if somebody is a dual member, they can certainly use the ACP’s MKSAP (Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program) hospital-based modules as well. We’re also working with SHM, looking for areas they might fill in around knowledge and updates—things that could be brought into the program over time.”

In regard to the evaluation and performance modules, ABIM offers three main pathways, including the Hospital-Based PIM, which targets core measure sets like community-acquired pneumonia and congestive heart failure and DVT prophylaxis. “Hospitalists can use those PIMs to start a quality-improvement program, or they can use it to report on one they are working on,” Dr. Holmboe says, adding the Hospital Based PIM’s online module will be redesigned this summer to improve the user experience.

Two other approaches are the Self-Directed PIM and the Accepted Quality Improvement programs. “That would be for hospitalists who may not be working on the core measure sets in the hospital-based PIM, but are still important,” he says. “They can use that module to report on those activities and get the points they need.”

Dr. Holmboe also points out that diplomates do not have to complete all the other requirements before they take the exam. “Some people get confused; you don’t have to cram in the 100 points before the exam,” Dr. Holmboe explains. He notes that the exam can, for example, be taken this year and the remainder of the requirements completed at a later date.

“If it was up to me, you should do a [PIM] every year,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, SFHM, CEO of SHM and one of the architects of the new FPHM pathway. “If you are a real hospitalist, completing a PIM every three years shouldn’t be a big deal. You should be able to say, ‘I’ve looked at 10 things: how I’m doing in pneumonia, how I’m doing in DVT, how I’m doing in glycemic control. This isn’t work for me; it’s part of my workflow.’ It’s like asking a salesman how many sales calls have you made, how many miles have you driven, and how many sales have you closed.”

The Examination

Dr. Wiese, associate dean of Graduate Medical Education and professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, completed his 10-year MOC in 2008, and he says the process made him “a better physician.” As president of SHM and chair of the FPHM test-writing committee, he envisions that the new MOC pathway will help “ramp up the quality of care for the hospitalized patient.”

“The FPHM MOC process is much more than just a different exam,” he says. “It is true the secure examination will have a lot more hospital-medicine-patient content focus, but not to the exclusion of ambulatory content.”

—Jeff Wiese, SHM president, ABIM Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Test Writing Committee chair

The content-area blueprint (see “Traditional IM Test vs. Focused Practice in HM Test” below) for the FPHM exam includes 15% of questions in the areas of quality and patient safety, along with another 15% in consultative and comanagement topics. Transitions of care and ambulatory questions make up another 15% of the exam.

“If there is one component of the exam that will [be HM-focused], it’s the questions of the exam that are focusing on the core principles of quality and patient safety,” Dr. Wiese says.

That’s music to the ears of many hospitalists—including Dr. Ammann—who know questions about managing cholesterol aren’t relevant to hospitalists. Dr. Ammann was an office-based physician before becoming a hospitalist in 2005. One year later, she was promoted to director of her group, which includes 14 physicians and two nonphysician providers.

“I was really hoping I would be able to [MOC] through the focused practice in HM,” she says. “I did practice office medicine, so I probably have a little advantage. But I was not looking forward to spending time learning and brushing up on things that I am not doing anymore—not only because I’m not doing it anymore, but it would be a waste of time because I’m not going to be doing it, either.”

One of her hospitalist colleagues is taking the traditional IM pathway to MOC, Dr. Ammann says, because “she doesn’t want to limit her scope.” But that’s not how Dr. Ammann sees the FPHM. She is committed to HM and doesn’t have “any problems kissing office medicine goodbye.”

“I think it will work out well for me, but I also think it will be great for our program to have a director who has a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine,” she says. “It shows my commitment, and we can hold that up to the rest of the organization and say we really have someone who is concentrated in this field.”

Educational Efforts

Vikas Parekh, MD, FHM, is in his second year as the chair of SHM’s Education Committee, and says the first task at hand is to educate hospitalists about the new FPHM pathway to MOC. The University of Michigan hospitalist says his committee, working with ABIM and SHM staff, is focused on two major educational efforts: developing the SHM strategy to assist hospitalists with the new FPHM MOC pathway, and “fulfilling the needs of hospitalists, in terms of the resources they have for the MOC process.”

“We’ve already started down this route, in terms of developing resources,” Dr. Parekh says. “We’ve done a few things that have been easy. One is the ABIM learning session pre-course at the annual meeting. … It earns you points toward the medical-knowledge component.”

ABIM and ACP are the traditional avenues for medical-knowledge and practice-improvement requirements for the MOC process. SHM and ABIM currently are working to develop medical-knowledge modules in the domains of patient safety and quality improvement, areas most relevant to HM. Dr. Parekh expects those components to be available in early 2011.

“Practice improvement is likely to be our second main effort,” Dr. Parekh says. “SHM has a lot of resources within our resource rooms that have the shell of what you would really need to meet ABIM requirements for a PIM but aren’t quite complete or thorough enough, or have all the bells and whistles that ABIM wants them to have. … We think we can do a much better job focusing the PIMs to hospitalists.”

At a more granular level, Dr. Wellikson envisions a “suite of products” to assist members in the MOC process. “What we are trying to do is develop resources that help people practice better medicine,” he says, “and while we are helping you practice better medicine, you can also use that to prove to [ABIM] that you have done it.

“So if you log onto the website today and downloaded and completed any of those SHM resource rooms, somewhere in the next several months you will be able to click on a form, enter the results, send it to ABIM, and you’ll have satisfied a PIM,” Dr. Wellikson says. “You can do the work today.”

SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safer Transitions) and Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation programs are prime candidates for Web-based PIMs, according to Dr. Holmboe.

“I think it is still very early, but we are very excited about this,” Dr. Parekh says. “I think a lot of people still have questions about what exactly this mean to me, and why should I recertify through this focused practice as opposed to the traditional general pathway? We hope to change that by making the resources focused to their practice.” TH

Jason Carris is editor of The Hospitalist.

Some in her HM group think Cathleen Ammann, MD, is the guinea pig. Dr. Ammann, the medical director of the hospital medicine division at Wentworth-Douglass Hospital in Dover, N.H., will be one of the first to complete her American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) through the new Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) pathway. Dr. Ammann—and the hospital administration—sees things a little differently.

“Am I the guinea pig or a pioneer?” a hospitalist in Dr. Ammann’s group asked her recently. “I definitely see it as being a pioneer. When you look back in another 10 years, hospital medicine might be a specialty with its own certification. I know it’s a little corny, but I look forward to getting in on that at the ground floor.”

Dr. Ammann is one of about 175 hospitalists who have signed up to recertify through FPHM. Her internal-medicine (IM) certification expires at the end of the year, so she will be taking the recertification exam Oct. 25.

“I hope the test focuses more on what I’m doing … stroke, quality measures,” she says. “Hospitalists know that stuff like the back of our hand. … I think it will work out well for me, but I also think it will be great for our program to have a director who has a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine. It shows my commitment, and we can hold that up to the rest of the organization and say we really have someone who is concentrated in this field.”

Dr. Ammann sums up the thinking of many HM leaders who’ve been working with ABIM and the American Board of Medical Specialties to launch the MOC pathway for hospitalists: Not only does a focused practice certification allow the more than 30,000 hospitalists in the U.S. to define themselves as different, it also provides hospitalists an MOC process and secured examination more acutely tailored to their skill sets and daily practice. The new pathway also requires ACLS certification and stresses continued “maintenance of competency,” according to SHM leaders, through a triennial self-evaluation requirement (60 self-evaluation points, with at least 20 points from medical knowledge modules and 40 points from completion of practice performance modules). The traditional IM MOC requires a practice-improvement module (PIM) every 10 years.

“The process will ask diplomates to participate in practice improvement every three years, which will focus on the ongoing need for performance improvement,” says Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, SHM president and chair of the ABIM Hospital Medicine MOC Question Writing Committee. “It will separate out the authentic hospitalist who is representing the goals and virtues that we are espousing as a society, particularly with regards to quality healthcare and safe healthcare. But I also think there are unique benefits for the patient that will be receiving the healthcare, because through this process, I believe, every diplomate will be a better hospitalist as a product of having done it.”

Here’s a brief look at what hospitalists interested in the FPHM MOC can expect:

The Process and Timeline

ABIM and SHM began working toward an HM-focused pathway about five years ago, and the two groups announced the FPHM program in September 2009. ABIM is in the process of retooling its website for the new MOC pathway. The entry system—to sign up and begin the MOC’s attestation process—was made public in March. The registration interface for the secure exam opened to the hospitalist community May 1, says Eric Holmboe, MD, ABIM’s chief medical officer.

“Diplomates can signify their interest and start the attestation process, which will allow them to get formal entry into the pathway,” Dr. Holmboe says. “Once they receive the attestation confirmation back, they can start doing the requirements around the medical knowledge and performance and practice requirements. Those are all available on the website. … We’re excited. The first phase of the project is live. This is a brand-new pathway for MOC, and we’re really hopeful people will find it valuable and useful.”

Board recertification is no easy task, and prospective diplomates should organize a plan of attack based upon individual workloads and regular involvement in performance-improvement programs. Some hospitalists will only need six to nine months to complete all the requirements and take the exam; others might take a conservative approach and need one to two years.

“Eighteen months is very reasonable,” Dr. Holmboe says. “Because of the 40-point requirement for the evaluation of performance and practice, that means you have to do the hospital-based PIM or self-directed PIM, or some combination thereof, twice. So if you haven’t been active in QI projects in your hospital, you really need to get going.”

Some hospitalists and HM groups work on quality-improvement (QI) projects regularly. Dr. Ammann plans to use a recent QI project looking at her group’s compliance with antibiotic selection for pneumonia to satisfy one of her required PIMs.

“[The three-year] requirement should be easy for directors because we’re always doing that kind of work anyway,” she says. “We just finished a project where we had to improve our compliance with antibiotic selection. We looked at our processes and found that our pathway wasn’t clear, and it could be interpreted a couple different ways. So our chief of medicine and I just changed the pathway, put it out there, and since then, our compliance has consistently been 100%.

We have two quarters of data, and I’m going to use that for my PIM, which is nice, because it’s done.”

For hospitalists whose certification runs out in 2011 or beyond, Dr. Holmboe suggests the following timeline:

Now through end of 2010

- Register for the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine MOC pathway on ABIM’ website (www.abim.org/moc/policies. aspx);

- Complete the attestation process;

- Get involved in an appropriate (hospital-based) performance-improvement activity; and

- Complete Update in Hospital Medicine using ABIM or ACP medical education modules.

—Cathleen Ammann, MD, medical director, hospital medicine division, Wentworth-Douglass Hospital, Dover, N.H.

First six months of 2011

- Complete the next yearly Update in HM module;

- Develop a strategy to prepare for the exam, which is given in the fall; and

- Plan and complete your second performance improvement activity.

Second half of 2011

- Prepare for the exam; and

- Pass the exam.

Start Process Now, Start Earning Points

ABIM is encouraging prospective FPHM diplomates to begin working on medical-knowledge modules. Most are designed to “stretch folks and to get them to look things up.”

“ACP, to their credit, also has hospital-based modules,” Dr. Holmboe says. “So if somebody is a dual member, they can certainly use the ACP’s MKSAP (Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program) hospital-based modules as well. We’re also working with SHM, looking for areas they might fill in around knowledge and updates—things that could be brought into the program over time.”

In regard to the evaluation and performance modules, ABIM offers three main pathways, including the Hospital-Based PIM, which targets core measure sets like community-acquired pneumonia and congestive heart failure and DVT prophylaxis. “Hospitalists can use those PIMs to start a quality-improvement program, or they can use it to report on one they are working on,” Dr. Holmboe says, adding the Hospital Based PIM’s online module will be redesigned this summer to improve the user experience.

Two other approaches are the Self-Directed PIM and the Accepted Quality Improvement programs. “That would be for hospitalists who may not be working on the core measure sets in the hospital-based PIM, but are still important,” he says. “They can use that module to report on those activities and get the points they need.”

Dr. Holmboe also points out that diplomates do not have to complete all the other requirements before they take the exam. “Some people get confused; you don’t have to cram in the 100 points before the exam,” Dr. Holmboe explains. He notes that the exam can, for example, be taken this year and the remainder of the requirements completed at a later date.

“If it was up to me, you should do a [PIM] every year,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, SFHM, CEO of SHM and one of the architects of the new FPHM pathway. “If you are a real hospitalist, completing a PIM every three years shouldn’t be a big deal. You should be able to say, ‘I’ve looked at 10 things: how I’m doing in pneumonia, how I’m doing in DVT, how I’m doing in glycemic control. This isn’t work for me; it’s part of my workflow.’ It’s like asking a salesman how many sales calls have you made, how many miles have you driven, and how many sales have you closed.”

The Examination

Dr. Wiese, associate dean of Graduate Medical Education and professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans, completed his 10-year MOC in 2008, and he says the process made him “a better physician.” As president of SHM and chair of the FPHM test-writing committee, he envisions that the new MOC pathway will help “ramp up the quality of care for the hospitalized patient.”

“The FPHM MOC process is much more than just a different exam,” he says. “It is true the secure examination will have a lot more hospital-medicine-patient content focus, but not to the exclusion of ambulatory content.”

—Jeff Wiese, SHM president, ABIM Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Test Writing Committee chair

The content-area blueprint (see “Traditional IM Test vs. Focused Practice in HM Test” below) for the FPHM exam includes 15% of questions in the areas of quality and patient safety, along with another 15% in consultative and comanagement topics. Transitions of care and ambulatory questions make up another 15% of the exam.

“If there is one component of the exam that will [be HM-focused], it’s the questions of the exam that are focusing on the core principles of quality and patient safety,” Dr. Wiese says.

That’s music to the ears of many hospitalists—including Dr. Ammann—who know questions about managing cholesterol aren’t relevant to hospitalists. Dr. Ammann was an office-based physician before becoming a hospitalist in 2005. One year later, she was promoted to director of her group, which includes 14 physicians and two nonphysician providers.

“I was really hoping I would be able to [MOC] through the focused practice in HM,” she says. “I did practice office medicine, so I probably have a little advantage. But I was not looking forward to spending time learning and brushing up on things that I am not doing anymore—not only because I’m not doing it anymore, but it would be a waste of time because I’m not going to be doing it, either.”

One of her hospitalist colleagues is taking the traditional IM pathway to MOC, Dr. Ammann says, because “she doesn’t want to limit her scope.” But that’s not how Dr. Ammann sees the FPHM. She is committed to HM and doesn’t have “any problems kissing office medicine goodbye.”

“I think it will work out well for me, but I also think it will be great for our program to have a director who has a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine,” she says. “It shows my commitment, and we can hold that up to the rest of the organization and say we really have someone who is concentrated in this field.”

Educational Efforts

Vikas Parekh, MD, FHM, is in his second year as the chair of SHM’s Education Committee, and says the first task at hand is to educate hospitalists about the new FPHM pathway to MOC. The University of Michigan hospitalist says his committee, working with ABIM and SHM staff, is focused on two major educational efforts: developing the SHM strategy to assist hospitalists with the new FPHM MOC pathway, and “fulfilling the needs of hospitalists, in terms of the resources they have for the MOC process.”

“We’ve already started down this route, in terms of developing resources,” Dr. Parekh says. “We’ve done a few things that have been easy. One is the ABIM learning session pre-course at the annual meeting. … It earns you points toward the medical-knowledge component.”

ABIM and ACP are the traditional avenues for medical-knowledge and practice-improvement requirements for the MOC process. SHM and ABIM currently are working to develop medical-knowledge modules in the domains of patient safety and quality improvement, areas most relevant to HM. Dr. Parekh expects those components to be available in early 2011.

“Practice improvement is likely to be our second main effort,” Dr. Parekh says. “SHM has a lot of resources within our resource rooms that have the shell of what you would really need to meet ABIM requirements for a PIM but aren’t quite complete or thorough enough, or have all the bells and whistles that ABIM wants them to have. … We think we can do a much better job focusing the PIMs to hospitalists.”

At a more granular level, Dr. Wellikson envisions a “suite of products” to assist members in the MOC process. “What we are trying to do is develop resources that help people practice better medicine,” he says, “and while we are helping you practice better medicine, you can also use that to prove to [ABIM] that you have done it.

“So if you log onto the website today and downloaded and completed any of those SHM resource rooms, somewhere in the next several months you will be able to click on a form, enter the results, send it to ABIM, and you’ll have satisfied a PIM,” Dr. Wellikson says. “You can do the work today.”

SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safer Transitions) and Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation programs are prime candidates for Web-based PIMs, according to Dr. Holmboe.

“I think it is still very early, but we are very excited about this,” Dr. Parekh says. “I think a lot of people still have questions about what exactly this mean to me, and why should I recertify through this focused practice as opposed to the traditional general pathway? We hope to change that by making the resources focused to their practice.” TH

Jason Carris is editor of The Hospitalist.

Wachter’s World

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—Democrats and Republicans have trumpeted that unprecedented changes in the healthcare system are on the way, but the dean of HM cautions that significant change is still years away.

“The reform bill, to my mind, mostly kicked the hard decision for cost, quality, and safety down the road,” said Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. “All of these issues have been raised, though.”

Dr. Wachter, former SHM president, author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachters world.com), and recently named the 10th-most-powerful physician executive in the nation by Modern Healthcare, used his annual HM10 address to paint a cautiously optimistic picture of HM playing a leading role in quality, safety, and innovation in the delivery of healthcare.

“It is a completely open question, whether we will be capable of snapping our fingers and creating a set of incentives or policy drivers that will allow the creation of the next Geisinger [Health System] without waiting 50 years,” Dr. Wachter said. “These cultures take a long time to develop. It’s not just about the [organizational] chart and the way money flows. You have to develop the culture of shared governance.”

In what has become a rite, Dr. Wachter gives the closing address at SHM’s annual meeting. This year’s title: “Use Your Words: Understanding the New Language of Healthcare Reform.” He focused most of his speech on finding the balance between high-quality and low-cost patient care, particularly when viewed through the prism of the “cost curve,” the economic principle that measures benefits against their cost.

Medical care on the “flat part of the curve” equates to tests, procedures, or other engagements that might have prophylactic value but little clinical benefit. From a purely clinical point of view, that is acceptable, but layering in a cost-benefit analysis adds a more objective way of deciding whether the care delivered is “worth the cost,” Dr. Wachter said.

—Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco

“The question is: Where do we want to live on this curve?” he added. “As you spend more money, you may be getting more benefit, but the incremental amount . . . pushes out past the flat part of curve.”

Dr. Wachter boiled his lesson down to two philosophies. In one, the practice of HM means a test, a procedure, or a consult is ordered because the benefits outweigh the risks. In the other, that same episodic treatment is ordered only if every less-expensive option has already been attempted. “These are absolutely fundamental tensions,” he admitted.

But not all that is reform must be contentious, he said. Take the renewed push toward “accountable-care organizations,” in which providers partner and share responsibility for both the quality and cost of healthcare for a specific population of beneficiaries. The healthcare reform bill contains incentives for such a structure, which Dr. Wachter views as the government’s latest attempt to improve care by controlling how much reimbursement physicians and their employers receive.

While other specialists might not be experienced with data-point discussions on cost savings with hospital administrators, HM leaders are all too familiar with the concept, as most have those discussions during annual hospital subsidy negotiations. Correspondingly, those who listened to Dr. Wachter’s advice agreed that there is ample opportunity to lead the charge for quality and safety improvement—and the likely savings to be associated with those changes.

“Let’s be patient for what’s coming around the corner,” said Daniel Dressler, MD, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta and an SHM board member. “But let’s not miss the boat.” HM2010

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—Democrats and Republicans have trumpeted that unprecedented changes in the healthcare system are on the way, but the dean of HM cautions that significant change is still years away.

“The reform bill, to my mind, mostly kicked the hard decision for cost, quality, and safety down the road,” said Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. “All of these issues have been raised, though.”

Dr. Wachter, former SHM president, author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachters world.com), and recently named the 10th-most-powerful physician executive in the nation by Modern Healthcare, used his annual HM10 address to paint a cautiously optimistic picture of HM playing a leading role in quality, safety, and innovation in the delivery of healthcare.

“It is a completely open question, whether we will be capable of snapping our fingers and creating a set of incentives or policy drivers that will allow the creation of the next Geisinger [Health System] without waiting 50 years,” Dr. Wachter said. “These cultures take a long time to develop. It’s not just about the [organizational] chart and the way money flows. You have to develop the culture of shared governance.”

In what has become a rite, Dr. Wachter gives the closing address at SHM’s annual meeting. This year’s title: “Use Your Words: Understanding the New Language of Healthcare Reform.” He focused most of his speech on finding the balance between high-quality and low-cost patient care, particularly when viewed through the prism of the “cost curve,” the economic principle that measures benefits against their cost.

Medical care on the “flat part of the curve” equates to tests, procedures, or other engagements that might have prophylactic value but little clinical benefit. From a purely clinical point of view, that is acceptable, but layering in a cost-benefit analysis adds a more objective way of deciding whether the care delivered is “worth the cost,” Dr. Wachter said.

—Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco

“The question is: Where do we want to live on this curve?” he added. “As you spend more money, you may be getting more benefit, but the incremental amount . . . pushes out past the flat part of curve.”

Dr. Wachter boiled his lesson down to two philosophies. In one, the practice of HM means a test, a procedure, or a consult is ordered because the benefits outweigh the risks. In the other, that same episodic treatment is ordered only if every less-expensive option has already been attempted. “These are absolutely fundamental tensions,” he admitted.

But not all that is reform must be contentious, he said. Take the renewed push toward “accountable-care organizations,” in which providers partner and share responsibility for both the quality and cost of healthcare for a specific population of beneficiaries. The healthcare reform bill contains incentives for such a structure, which Dr. Wachter views as the government’s latest attempt to improve care by controlling how much reimbursement physicians and their employers receive.

While other specialists might not be experienced with data-point discussions on cost savings with hospital administrators, HM leaders are all too familiar with the concept, as most have those discussions during annual hospital subsidy negotiations. Correspondingly, those who listened to Dr. Wachter’s advice agreed that there is ample opportunity to lead the charge for quality and safety improvement—and the likely savings to be associated with those changes.

“Let’s be patient for what’s coming around the corner,” said Daniel Dressler, MD, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta and an SHM board member. “But let’s not miss the boat.” HM2010

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—Democrats and Republicans have trumpeted that unprecedented changes in the healthcare system are on the way, but the dean of HM cautions that significant change is still years away.

“The reform bill, to my mind, mostly kicked the hard decision for cost, quality, and safety down the road,” said Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. “All of these issues have been raised, though.”

Dr. Wachter, former SHM president, author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachters world.com), and recently named the 10th-most-powerful physician executive in the nation by Modern Healthcare, used his annual HM10 address to paint a cautiously optimistic picture of HM playing a leading role in quality, safety, and innovation in the delivery of healthcare.

“It is a completely open question, whether we will be capable of snapping our fingers and creating a set of incentives or policy drivers that will allow the creation of the next Geisinger [Health System] without waiting 50 years,” Dr. Wachter said. “These cultures take a long time to develop. It’s not just about the [organizational] chart and the way money flows. You have to develop the culture of shared governance.”

In what has become a rite, Dr. Wachter gives the closing address at SHM’s annual meeting. This year’s title: “Use Your Words: Understanding the New Language of Healthcare Reform.” He focused most of his speech on finding the balance between high-quality and low-cost patient care, particularly when viewed through the prism of the “cost curve,” the economic principle that measures benefits against their cost.

Medical care on the “flat part of the curve” equates to tests, procedures, or other engagements that might have prophylactic value but little clinical benefit. From a purely clinical point of view, that is acceptable, but layering in a cost-benefit analysis adds a more objective way of deciding whether the care delivered is “worth the cost,” Dr. Wachter said.

—Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco

“The question is: Where do we want to live on this curve?” he added. “As you spend more money, you may be getting more benefit, but the incremental amount . . . pushes out past the flat part of curve.”

Dr. Wachter boiled his lesson down to two philosophies. In one, the practice of HM means a test, a procedure, or a consult is ordered because the benefits outweigh the risks. In the other, that same episodic treatment is ordered only if every less-expensive option has already been attempted. “These are absolutely fundamental tensions,” he admitted.

But not all that is reform must be contentious, he said. Take the renewed push toward “accountable-care organizations,” in which providers partner and share responsibility for both the quality and cost of healthcare for a specific population of beneficiaries. The healthcare reform bill contains incentives for such a structure, which Dr. Wachter views as the government’s latest attempt to improve care by controlling how much reimbursement physicians and their employers receive.

While other specialists might not be experienced with data-point discussions on cost savings with hospital administrators, HM leaders are all too familiar with the concept, as most have those discussions during annual hospital subsidy negotiations. Correspondingly, those who listened to Dr. Wachter’s advice agreed that there is ample opportunity to lead the charge for quality and safety improvement—and the likely savings to be associated with those changes.

“Let’s be patient for what’s coming around the corner,” said Daniel Dressler, MD, SFHM, director of hospital medicine at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta and an SHM board member. “But let’s not miss the boat.” HM2010

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Special Interests

HOSPITALISTS FROM ALL PARTS OF THE COUNTRY—and a few other countries—discussed a wide swath of topics during a community-based HM special-interest forum at HM10. Issues that were discussed included unit-based rounding, changes to Medicare consult codes, strategies for avoiding “dumps,” and working with specialists.

Two established community hospitalists—SHM co-founders John Nelson, MD, MHM, and Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, MHM—moderated the one-hour session.

Much of the debate centered on defining a hospitalist’s role and relationships with others in the hospital. One hospitalist said he’d noticed significant changes in the 15 years since he began HM practice; however, some issues remain unresolved: Primary-care physicians (PCPs) still know the patients better, and medical specialists still want hospitalists to be their “interns.”