User login

The Next Generation of Anticoagulants?

The popularity of the next generation of anticoagulation therapies could be dependent on whether reversing agents for the newest drugs can be developed, says a hospitalist who heads an antithrombotic clinic.

In October, the FDA approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) for atrial fibrillation (AF) patients. In a noninferiority study published last month, investigators found that treatment with oral rivaroxaban alone (15mg twice daily for three weeks, followed by 20mg once daily) showed effectiveness versus subcutaneous enoxaparin followed by a vitamin K antagonist. In relation to the primary outcome of recurrent DVT, rivaroxaban had noninferior efficacy (36 events [2.1%], vs. 51 events, 0.44 to 1.04; P<0.001) (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499-2510).

Another study, dubbed ROCKET-AF (PDF) and unveiled at an American Heart Association meeting in November, reported that rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin in the treatment of stroke and non-CNS embolism. Study patients treated with rivaroxaban exhibited significantly less events (1.71) per 100 patient-years (188 patients) compared with those on warfarin (2.16; 241 patients; P<0.001 for noninferiority, P=0.018 for superiority).

A third medication, apixaban, which also acts as a direct

fact Xa inhibitor, is currently being tested in clinical trials.

Geno Merli, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and head of the Jefferson Antithrombotic Therapy Service, both in Philadelphia, says one of the most pressing issues with the Xa inhibitors is that there is not yet a reversing agent for the drugs should complications arise. “I can reverse Coumadin,” Dr. Merli says. “I can give vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma. You’re giving back the factors that were affected.”

Dr. Merli adds that pharmaceutical companies already are working on development of reversing agents and antibodies, but until those are approved, some physicians might shy away from new anticoagulant therapies. Still, he encourages physicians to get the medications added to their respective hospitals’ medicine cabinets as quickly as feasible.

“You’ve got to have it on your formulary because you have to know the drug,” Dr. Merli says. “You have to have it for the doctor who will choose to use it or the patient who comes in already on it.”

The popularity of the next generation of anticoagulation therapies could be dependent on whether reversing agents for the newest drugs can be developed, says a hospitalist who heads an antithrombotic clinic.

In October, the FDA approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) for atrial fibrillation (AF) patients. In a noninferiority study published last month, investigators found that treatment with oral rivaroxaban alone (15mg twice daily for three weeks, followed by 20mg once daily) showed effectiveness versus subcutaneous enoxaparin followed by a vitamin K antagonist. In relation to the primary outcome of recurrent DVT, rivaroxaban had noninferior efficacy (36 events [2.1%], vs. 51 events, 0.44 to 1.04; P<0.001) (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499-2510).

Another study, dubbed ROCKET-AF (PDF) and unveiled at an American Heart Association meeting in November, reported that rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin in the treatment of stroke and non-CNS embolism. Study patients treated with rivaroxaban exhibited significantly less events (1.71) per 100 patient-years (188 patients) compared with those on warfarin (2.16; 241 patients; P<0.001 for noninferiority, P=0.018 for superiority).

A third medication, apixaban, which also acts as a direct

fact Xa inhibitor, is currently being tested in clinical trials.

Geno Merli, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and head of the Jefferson Antithrombotic Therapy Service, both in Philadelphia, says one of the most pressing issues with the Xa inhibitors is that there is not yet a reversing agent for the drugs should complications arise. “I can reverse Coumadin,” Dr. Merli says. “I can give vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma. You’re giving back the factors that were affected.”

Dr. Merli adds that pharmaceutical companies already are working on development of reversing agents and antibodies, but until those are approved, some physicians might shy away from new anticoagulant therapies. Still, he encourages physicians to get the medications added to their respective hospitals’ medicine cabinets as quickly as feasible.

“You’ve got to have it on your formulary because you have to know the drug,” Dr. Merli says. “You have to have it for the doctor who will choose to use it or the patient who comes in already on it.”

The popularity of the next generation of anticoagulation therapies could be dependent on whether reversing agents for the newest drugs can be developed, says a hospitalist who heads an antithrombotic clinic.

In October, the FDA approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) for atrial fibrillation (AF) patients. In a noninferiority study published last month, investigators found that treatment with oral rivaroxaban alone (15mg twice daily for three weeks, followed by 20mg once daily) showed effectiveness versus subcutaneous enoxaparin followed by a vitamin K antagonist. In relation to the primary outcome of recurrent DVT, rivaroxaban had noninferior efficacy (36 events [2.1%], vs. 51 events, 0.44 to 1.04; P<0.001) (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499-2510).

Another study, dubbed ROCKET-AF (PDF) and unveiled at an American Heart Association meeting in November, reported that rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin in the treatment of stroke and non-CNS embolism. Study patients treated with rivaroxaban exhibited significantly less events (1.71) per 100 patient-years (188 patients) compared with those on warfarin (2.16; 241 patients; P<0.001 for noninferiority, P=0.018 for superiority).

A third medication, apixaban, which also acts as a direct

fact Xa inhibitor, is currently being tested in clinical trials.

Geno Merli, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and head of the Jefferson Antithrombotic Therapy Service, both in Philadelphia, says one of the most pressing issues with the Xa inhibitors is that there is not yet a reversing agent for the drugs should complications arise. “I can reverse Coumadin,” Dr. Merli says. “I can give vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma. You’re giving back the factors that were affected.”

Dr. Merli adds that pharmaceutical companies already are working on development of reversing agents and antibodies, but until those are approved, some physicians might shy away from new anticoagulant therapies. Still, he encourages physicians to get the medications added to their respective hospitals’ medicine cabinets as quickly as feasible.

“You’ve got to have it on your formulary because you have to know the drug,” Dr. Merli says. “You have to have it for the doctor who will choose to use it or the patient who comes in already on it.”

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: What is the relative efficacy of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/sulfa) versus ciprofloxacin for the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD?

Background: The use of antimicrobials in the treatment of COPD exacerbations is well accepted, with the original studies using amoxicillin, TMP/sulfa, and tetracyclines. Whether newer antimicrobial agents offer greater efficacy versus these standard agents remains uncertain.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled (double-dummy), noninferiority trial.

Setting: Two academic medical ICUs in Tunisia.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients (n=170) with severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation were randomized to standard medical therapy plus either TMP/sulfa or ciprofloxacin. Patients had a prior diagnosis of COPD and the clinical presence of purulent sputum and respiratory failure. The study excluded those who were immunosuppressed, had significant hepatic or renal disease, pneumonia, recent antibiotic use, active cancer, or inability to take oral medications.

The primary endpoint of hospital death and the need for an additional course of antibiotics was no different between the groups (16.4% with TMP/sulfa versus 15.3% with ciprofloxacin). The mean exacerbation-free interval, days of mechanical ventilation, and length of stay were no different. Noninferiority was defined as <10% relative difference.

Bottom line: TMP/sulfa was noninferior to ciprofloxacin in the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation.

Citation: Nouira S, Marghli S, Besbes L, et al. Standard versus newer antibacterial agents in the treatment of severe acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus ciprofloxacin. Clin Inf Dis. 2010;51:143-149.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: What is the relative efficacy of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/sulfa) versus ciprofloxacin for the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD?

Background: The use of antimicrobials in the treatment of COPD exacerbations is well accepted, with the original studies using amoxicillin, TMP/sulfa, and tetracyclines. Whether newer antimicrobial agents offer greater efficacy versus these standard agents remains uncertain.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled (double-dummy), noninferiority trial.

Setting: Two academic medical ICUs in Tunisia.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients (n=170) with severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation were randomized to standard medical therapy plus either TMP/sulfa or ciprofloxacin. Patients had a prior diagnosis of COPD and the clinical presence of purulent sputum and respiratory failure. The study excluded those who were immunosuppressed, had significant hepatic or renal disease, pneumonia, recent antibiotic use, active cancer, or inability to take oral medications.

The primary endpoint of hospital death and the need for an additional course of antibiotics was no different between the groups (16.4% with TMP/sulfa versus 15.3% with ciprofloxacin). The mean exacerbation-free interval, days of mechanical ventilation, and length of stay were no different. Noninferiority was defined as <10% relative difference.

Bottom line: TMP/sulfa was noninferior to ciprofloxacin in the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation.

Citation: Nouira S, Marghli S, Besbes L, et al. Standard versus newer antibacterial agents in the treatment of severe acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus ciprofloxacin. Clin Inf Dis. 2010;51:143-149.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: What is the relative efficacy of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/sulfa) versus ciprofloxacin for the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD?

Background: The use of antimicrobials in the treatment of COPD exacerbations is well accepted, with the original studies using amoxicillin, TMP/sulfa, and tetracyclines. Whether newer antimicrobial agents offer greater efficacy versus these standard agents remains uncertain.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled (double-dummy), noninferiority trial.

Setting: Two academic medical ICUs in Tunisia.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients (n=170) with severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation were randomized to standard medical therapy plus either TMP/sulfa or ciprofloxacin. Patients had a prior diagnosis of COPD and the clinical presence of purulent sputum and respiratory failure. The study excluded those who were immunosuppressed, had significant hepatic or renal disease, pneumonia, recent antibiotic use, active cancer, or inability to take oral medications.

The primary endpoint of hospital death and the need for an additional course of antibiotics was no different between the groups (16.4% with TMP/sulfa versus 15.3% with ciprofloxacin). The mean exacerbation-free interval, days of mechanical ventilation, and length of stay were no different. Noninferiority was defined as <10% relative difference.

Bottom line: TMP/sulfa was noninferior to ciprofloxacin in the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation.

Citation: Nouira S, Marghli S, Besbes L, et al. Standard versus newer antibacterial agents in the treatment of severe acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus ciprofloxacin. Clin Inf Dis. 2010;51:143-149.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Pneumonia Readmission Validation

Hospital readmissions are emblematic of the numerous challenges facing the US health care system. Despite high levels of spending, nearly 20% of Medicare beneficiaries are readmitted within 30 days of hospital discharge, many readmissions are considered preventable, and rates vary widely by hospital and region.1 Further, while readmissions have been estimated to cost taxpayers as much as $17 billion annually, the current fee‐for‐service method of paying for the acute care needs of seniors rewards hospitals financially for readmission, not their prevention.2

Pneumonia is the second most common reason for hospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries, accounting for approximately 650,000 admissions annually,3 and has been a focus of national quality‐improvement efforts for more than a decade.4, 5 Despite improvements in key processes of care, rates of readmission within 30 days of discharge following a hospitalization for pneumonia have been reported to vary from 10% to 24%.68 Among several factors, readmissions are believed to be influenced by the quality of both inpatient and outpatient care, and by care‐coordination activities occurring in the transition from inpatient to outpatient status.912

Public reporting of hospital performance is considered a key strategy for improving quality, reducing costs, and increasing the value of hospital care, both in the US and worldwide.13 In 2009, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded its reporting initiatives by adding risk‐adjusted hospital readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia to the Hospital Compare website.14, 15 Readmission rates are an attractive focus for public reporting for several reasons. First, in contrast to most process‐based measures of quality (eg, whether a patient with pneumonia received a particular antibiotic), a readmission is an adverse outcome that matters to patients and families.16 Second, unlike process measures whose assessment requires detailed review of medical records, readmissions can be easily determined from standard hospital claims. Finally, readmissions are costly, and their prevention could yield substantial savings to society.

A necessary prerequisite for public reporting of readmission is a validated, risk‐adjusted measure that can be used to track performance over time and can facilitate comparisons across institutions. Toward this end, we describe the development, validation, and results of a National Quality Forum‐approved and CMS‐adopted model to estimate hospital‐specific, risk‐standardized, 30‐day readmission rates for Medicare patients hospitalized with pneumonia.17

METHODS

Data Sources

We used 20052006 claims data from Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and carrier (physician) Standard Analytic Files to develop and validate the administrative model. The Medicare Enrollment Database was used to determine Medicare fee‐for‐service enrollment and mortality statuses. A medical record model, used for additional validation of the administrative model, was developed using information abstracted from the charts of 75,616 pneumonia cases from 19982001 as part of the National Pneumonia Project, a CMS quality improvement initiative.18

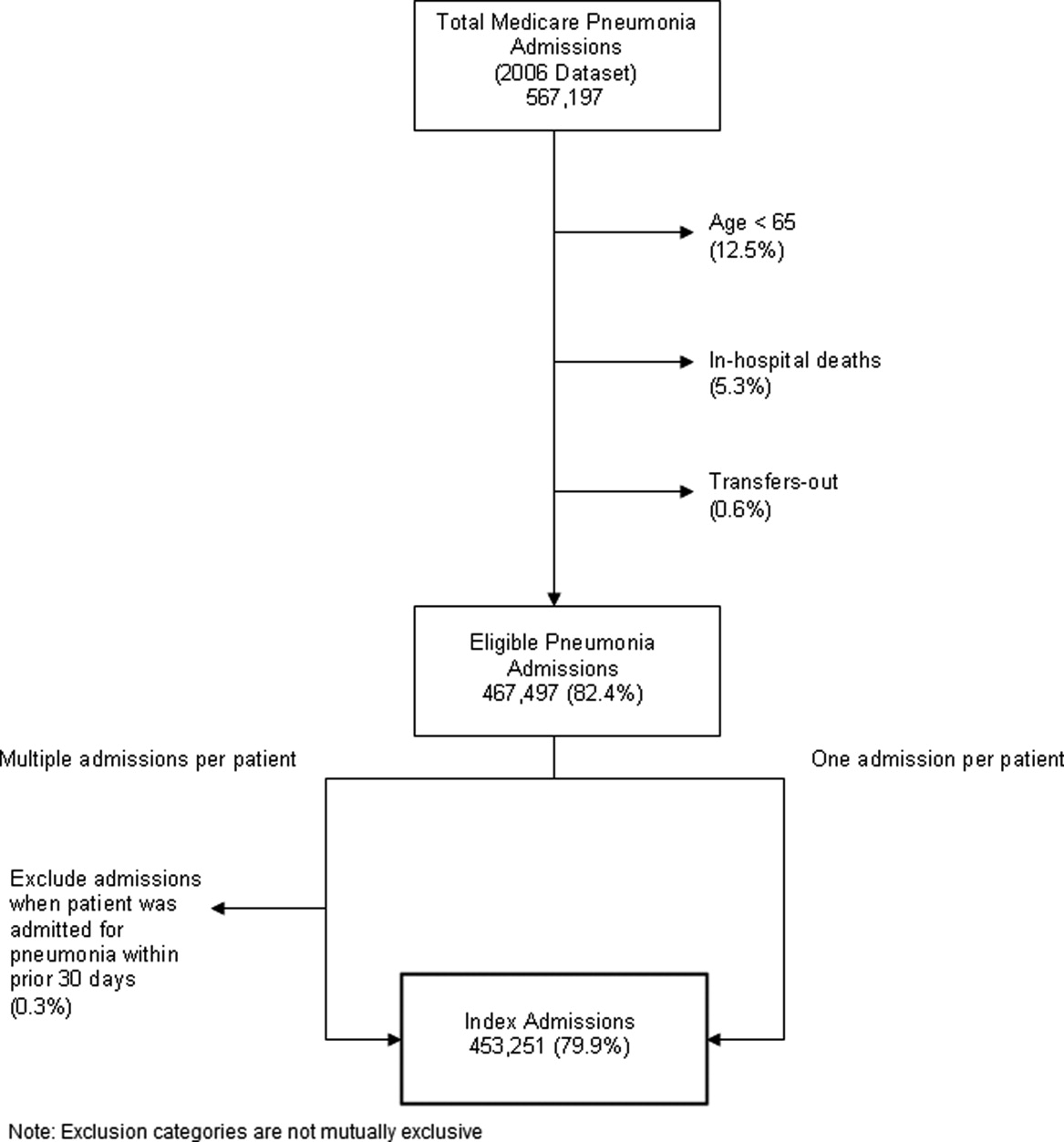

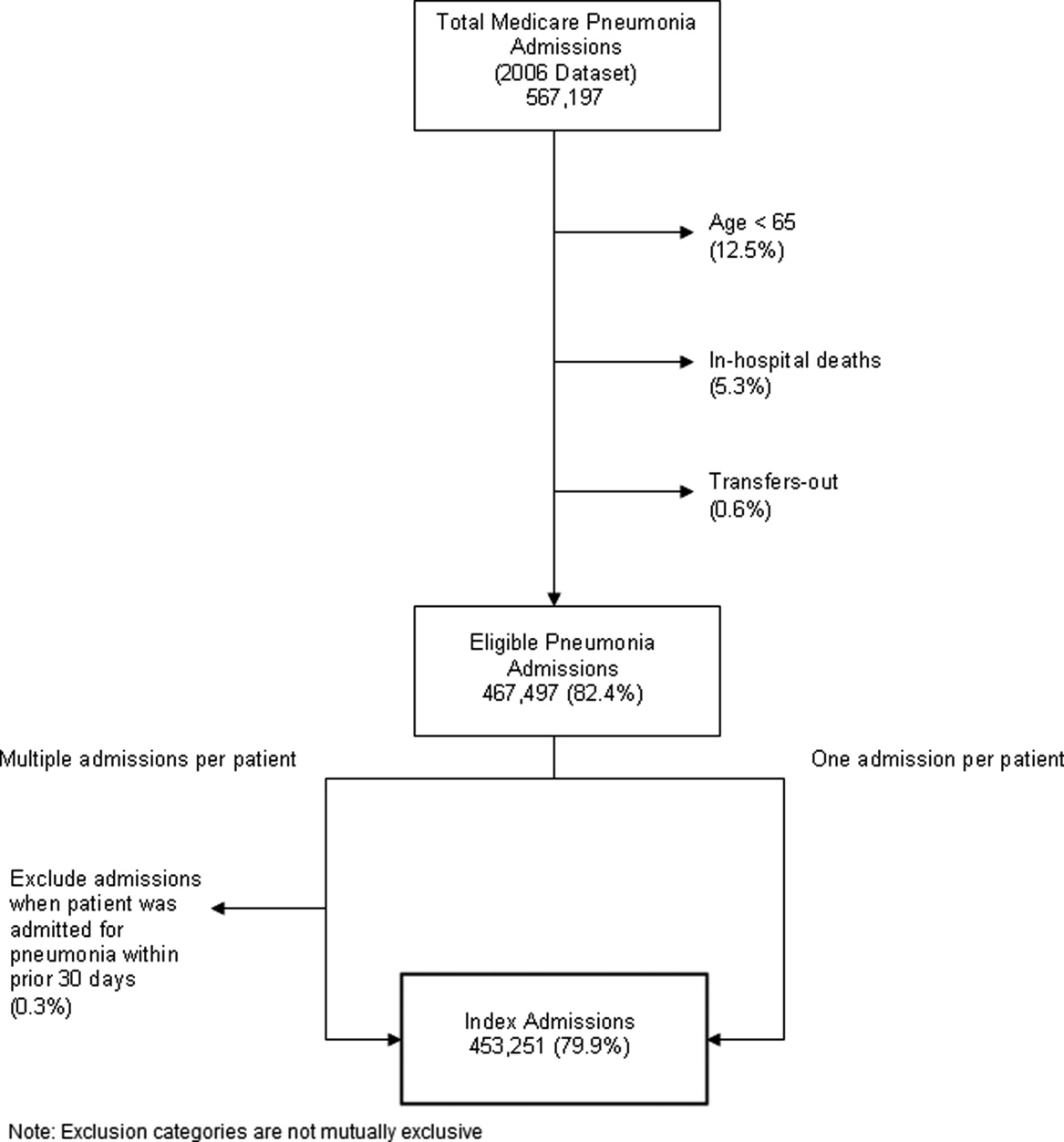

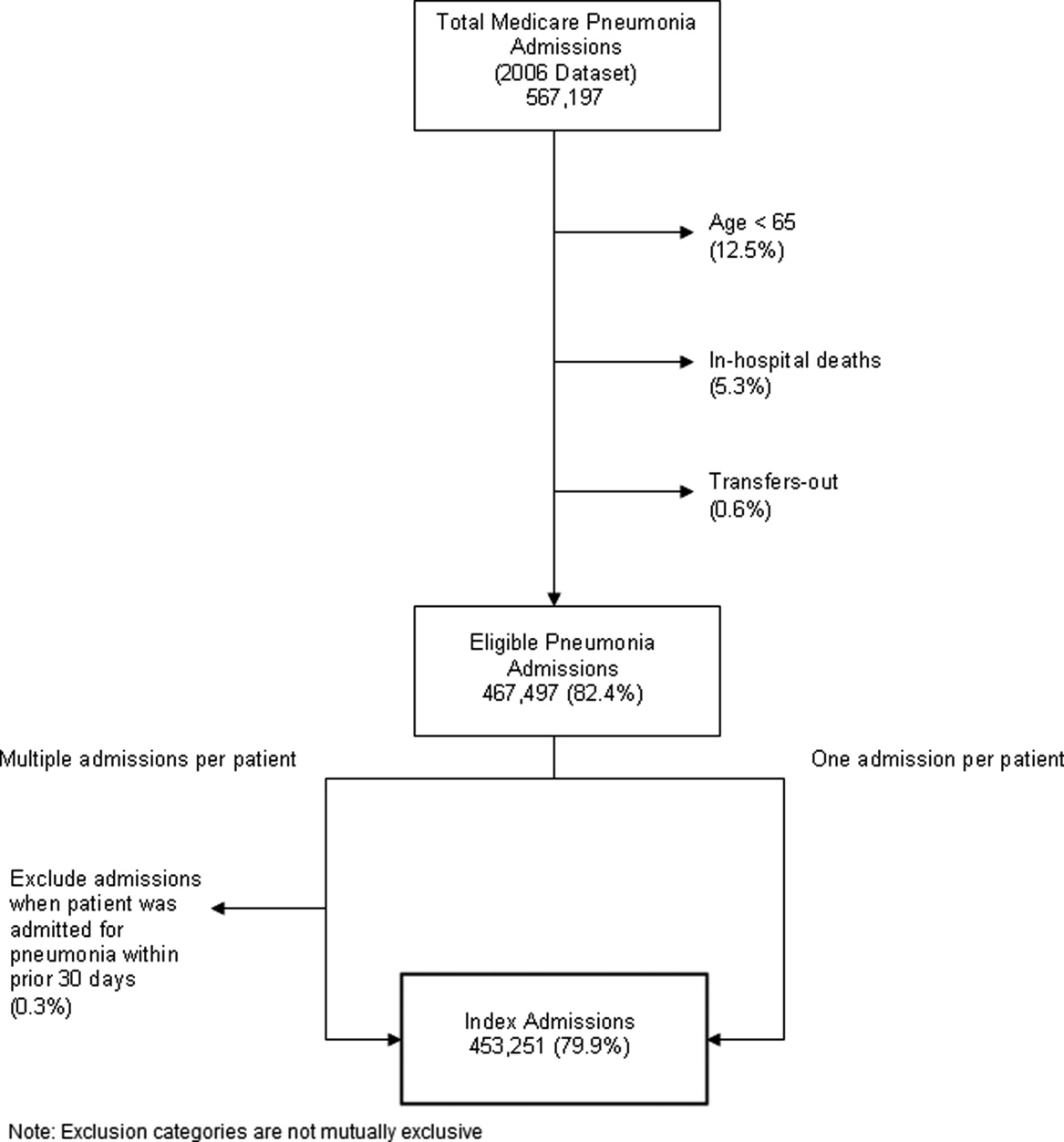

Study Cohort

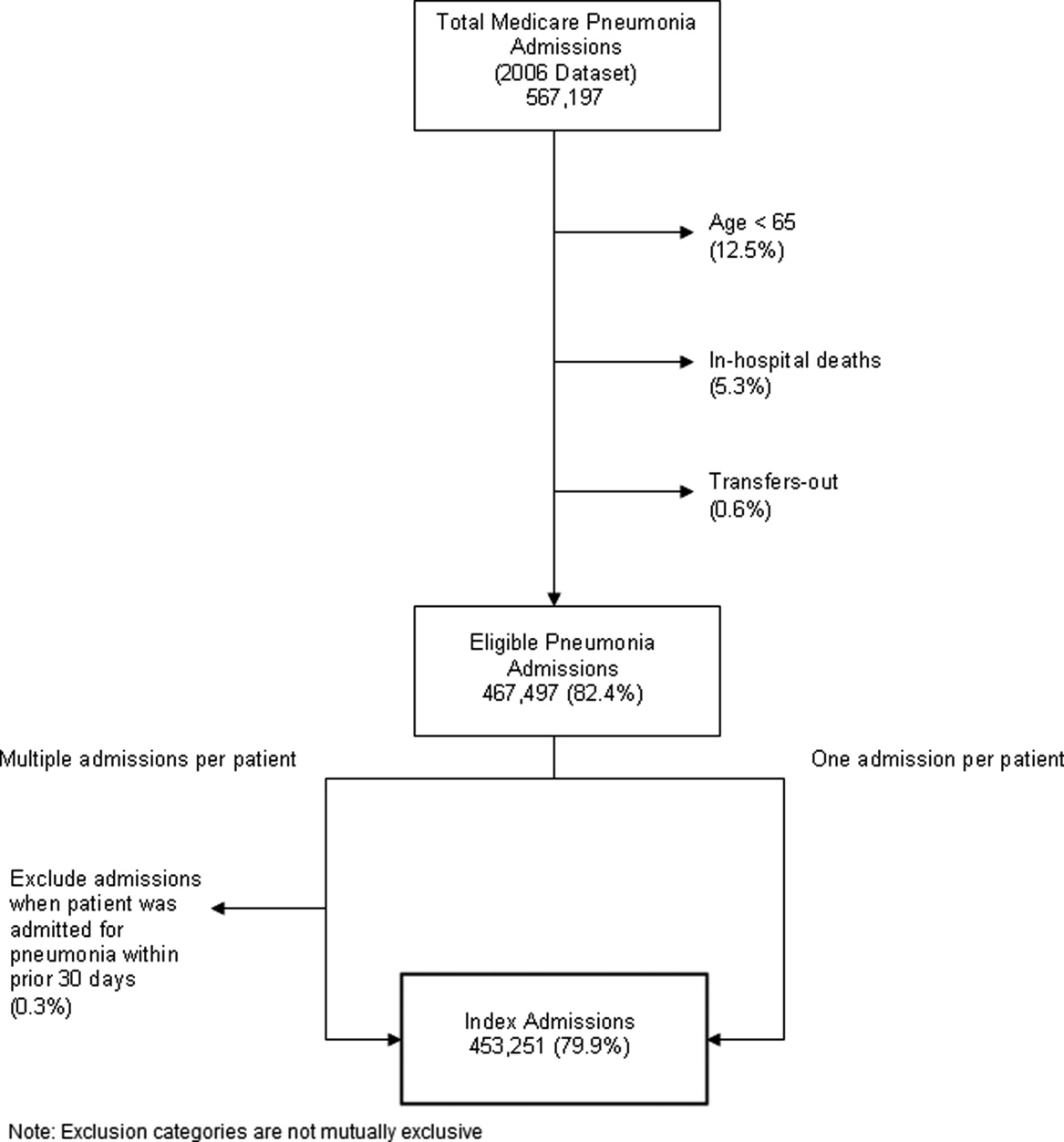

We identified hospitalizations of patients 65 years of age and older with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes 480.XX, 481, 482.XX, 483.X, 485, 486, 487.0) as potential index pneumonia admissions. Because our focus was readmission for patients discharged from acute care settings, we excluded admissions in which patients died or were transferred to another acute care facility. Additionally, we restricted analysis to patients who had been enrolled in fee‐for‐service Medicare Parts A and B, for at least 12 months prior to their pneumonia hospitalization, so that we could use diagnostic codes from all inpatient and outpatient encounters during that period to enhance identification of comorbidities.

Outcome

The outcome was 30‐day readmission, defined as occurrence of at least one hospitalization for any cause within 30 days of discharge after an index admission. Readmissions were identified from hospital claims data, and were attributed to the hospital that had discharged the patient. A 30‐day time frame was selected because it is a clinically meaningful period during which hospitals can be expected to collaborate with other organizations and providers to implement measures to reduce the risk of rehospitalization.

Candidate and Final Model Variables

Candidate variables for the administrative claims model were selected by a clinician team from 189 diagnostic groups included in the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) clinical classification system.19 The HCC clinical classification system was developed for CMS in preparation for all‐encounter risk adjustment for Medicare Advantage (managed care). Under the HCC algorithm, the 15,000+ ICD‐9‐CM diagnosis codes are assigned to one of 189 clinically‐coherent condition categories (CCs). We used the April 2008 version of the ICD‐9‐CM to CC assignment map, which is maintained by CMS and posted at

The final risk‐adjustment model included 39 variables selected by the team of clinicians and analysts, primarily based on their clinical relevance but also with knowledge of the strength of their statistical association with readmission outcome (Table 1). For each patient, the presence or absence of these conditions was assessed from multiple sources, including secondary diagnoses during the index admission, principal and secondary diagnoses from hospital admissions in the 12 months prior to the index admission, and diagnoses from hospital outpatient and physician encounters 12 months before the index admission. A small number of CCs were considered to represent potential complications of care (eg, bleeding). Because we did not want to adjust for complications of care occurring during the index admission, a patient was not considered to have one of these conditions unless it was also present in at least one encounter prior to the index admission.

| Variable | Frequencies | Estimate | Standard Error | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Intercept | 2.395 | 0.021 | ||||

| Age 65 (years above 65, continuous) | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.001 | |

| Male | 45 | 0.071 | 0.012 | 1.073 | 1.048 | 1.099 |

| History of CABG | 5.2 | 0.179 | 0.027 | 0.836 | 0.793 | 0.881 |

| Metastatic cancer and acute leukemia (CC 7) | 4.3 | 0.177 | 0.029 | 1.194 | 1.128 | 1.263 |

| Lung, upper digestive tract, and other severe cancers (CC 8) | 6.0 | 0.256 | 0.024 | 1.292 | 1.232 | 1.354 |

| Diabetes and DM complications (CC 15‐20, 119, 120) | 36 | 0.059 | 0.012 | 1.061 | 1.036 | 1.087 |

| Disorders of fluid/electrolyte/acid‐base (CC 22, 23) | 34 | 0.149 | 0.013 | 1.160 | 1.131 | 1.191 |

| Iron deficiency and other/unspecified anemias and blood disease (CC 47) | 46 | 0.118 | 0.012 | 1.126 | 1.099 | 1.153 |

| Other psychiatric disorders (CC 60) | 12 | 0.108 | 0.017 | 1.114 | 1.077 | 1.151 |

| Cardio‐respiratory failure and shock (CC 79) | 16 | 0.114 | 0.016 | 1.121 | 1.087 | 1.156 |

| Congestive heart failure (CC 80) | 39 | 0.151 | 0.014 | 1.163 | 1.133 | 1.194 |

| Chronic atherosclerosis (CC 83, 84) | 47 | 0.051 | 0.013 | 1.053 | 1.027 | 1.079 |

| Valvular and rheumatic heart disease (CC 86) | 23 | 0.062 | 0.014 | 1.064 | 1.036 | 1.093 |

| Arrhythmias (CC 92, 93) | 38 | 0.126 | 0.013 | 1.134 | 1.107 | 1.163 |

| Vascular or circulatory disease (CC 104‐106) | 38 | 0.088 | 0.012 | 1.092 | 1.066 | 1.119 |

| COPD (CC 108) | 58 | 0.186 | 0.013 | 1.205 | 1.175 | 1.235 |

| Fibrosis of lung and other chronic lung disorders (CC 109) | 17 | 0.086 | 0.015 | 1.090 | 1.059 | 1.122 |

| Renal failure (CC 131) | 17 | 0.147 | 0.016 | 1.158 | 1.122 | 1.196 |

| Protein‐calorie malnutrition (CC 21) | 7.9 | 0.121 | 0.020 | 1.129 | 1.086 | 1.173 |

| History of infection (CC 1, 3‐6) | 35 | 0.068 | 0.012 | 1.071 | 1.045 | 1.097 |

| Severe hematological disorders (CC 44) | 3.6 | 0.117 | 0.028 | 1.125 | 1.064 | 1.188 |

| Decubitus ulcer or chronic skin ulcer (CC 148, 149) | 10 | 0.101 | 0.018 | 1.106 | 1.067 | 1.146 |

| History of pneumonia (CC 111‐113) | 44 | 0.065 | 0.013 | 1.067 | 1.041 | 1.094 |

| Vertebral fractures (CC 157) | 5.1 | 0.113 | 0.024 | 1.120 | 1.068 | 1.174 |

| Other injuries (CC 162) | 32 | 0.061 | 0.012 | 1.063 | 1.038 | 1.089 |

| Urinary tract infection (CC 135) | 26 | 0.064 | 0.014 | 1.066 | 1.038 | 1.095 |

| Lymphatic, head and neck, brain, and other major cancers; breast, prostate, colorectal, and other cancers and tumors (CC 9‐10) | 16 | 0.050 | 0.016 | 1.051 | 1.018 | 1.084 |

| End‐stage renal disease or dialysis (CC 129, 130) | 1.9 | 0.131 | 0.037 | 1.140 | 1.060 | 1.226 |

| Drug/alcohol abuse/dependence/psychosis (CC 51‐53) | 12 | 0.081 | 0.017 | 1.084 | 1.048 | 1.121 |

| Septicemia/shock (CC 2) | 6.3 | 0.094 | 0.022 | 1.098 | 1.052 | 1.146 |

| Other gastrointestinal disorders (CC 36) | 56 | 0.073 | 0.012 | 1.076 | 1.051 | 1.102 |

| Acute coronary syndrome (CC 81, 82) | 8.3 | 0.126 | 0.019 | 1.134 | 1.092 | 1.178 |

| Pleural effusion/pneumothorax (CC 114) | 12 | 0.083 | 0.017 | 1.086 | 1.051 | 1.123 |

| Other urinary tract disorders (CC 136) | 24 | 0.059 | 0.014 | 1.061 | 1.033 | 1.090 |

| Stroke (CC 95, 96) | 10 | 0.047 | 0.019 | 1.049 | 1.011 | 1.088 |

| Dementia and senility (CC 49, 50) | 27 | 0.031 | 0.014 | 1.031 | 1.004 | 1.059 |

| Hemiplegia, paraplegia, paralysis, functional disability (CC 67‐69, 100‐102, 177, 178) | 7.4 | 0.068 | 0.021 | 1.070 | 1.026 | 1.116 |

| Other lung disorders (CC 115) | 45 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 1.005 | 0.982 | 1.030 |

| Major psychiatric disorders (CC 54‐56) | 11 | 0.038 | 0.018 | 1.038 | 1.003 | 1.075 |

| Asthma (CC 110) | 12 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 1.006 | 0.972 | 1.041 |

Model Derivation

For the development of the administrative claims model, we randomly sampled half of 2006 hospitalizations that met inclusion criteria. To assess model performance at the patient level, we calculated the area under the receiver operating curve (AUC), and calculated observed readmission rates in the lowest and highest deciles on the basis of predicted readmission probabilities. We also compared performance with a null model, a model that adjusted for age and sex, and a model that included all candidate variables.20

Risk‐Standardized Readmission Rates

Using hierarchical logistic regression, we modeled the log‐odds of readmission within 30 days of discharge from an index pneumonia admission as a function of patient demographic and clinical characteristics, and a random hospital‐specific intercept. This strategy accounts for within‐hospital correlation, or clustering, of observed outcomes, and models the assumption that underlying differences in quality among hospitals being evaluated lead to systematic differences in outcomes. We then calculated hospital‐specific readmission rates as the ratio of predicted‐to‐expected readmissions (similar to observed/expected ratio), multiplied by the national unadjusted ratea form of indirect standardization. Predicted number of readmissions in each hospital is estimated given the same patient mix and its estimated hospital‐specific intercept. Expected number of readmissions in each hospital is estimated using its patient mix and the average hospital‐specific intercept. To assess hospital performance in any given year, we re‐estimate model coefficients using that year's data.

Model Validation: Administrative Claims

We compared the model performance in the development sample with its performance in the sample from the 2006 data that was not selected for the development set, and separately among pneumonia admissions in 2005. The model was recalibrated in each validation set.

Model Validation: Medical Record Abstraction

We developed a separate medical record‐based model of readmission risk using information from charts that had previously been abstracted as part of CMS's National Pneumonia Project. To select variables for this model, the clinician team: 1) reviewed the list of variables that were included in a medical record model that was previously developed for validating the National Quality Forum‐approved pneumonia mortality measure; 2) reviewed a list of other potential candidate variables available in the National Pneumonia Project dataset; and 3) reviewed variables that emerged as potentially important predictors of readmission, based on a systematic review of the literature that was conducted as part of measure development. This selection process resulted in a final medical record model that included 35 variables.

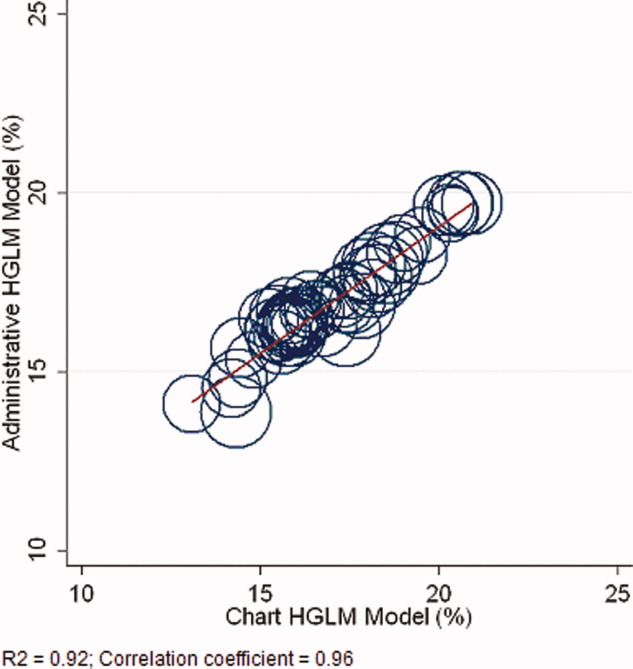

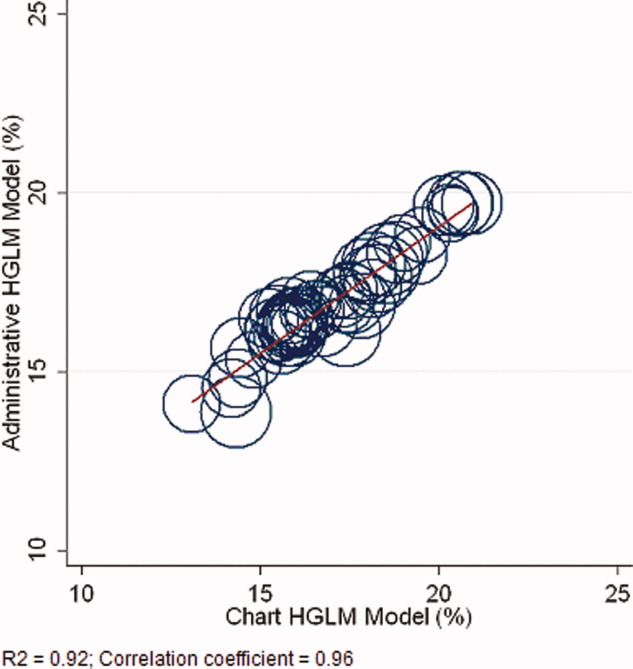

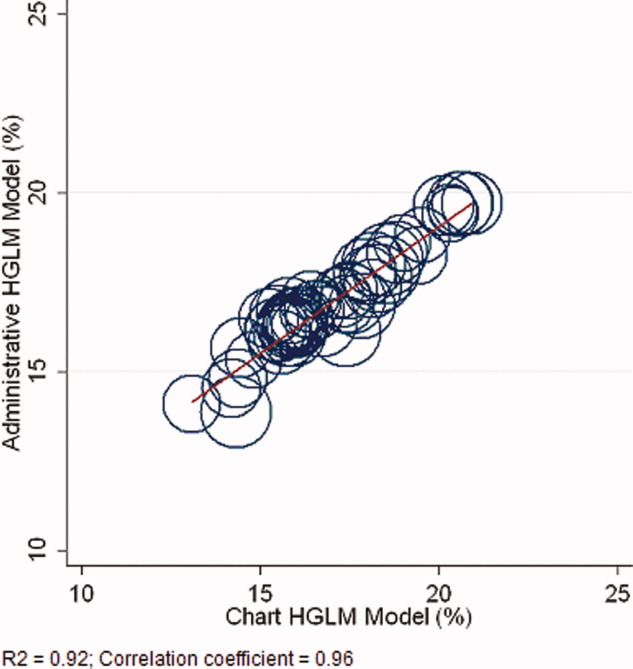

We linked patients in the National Pneumonia Project cohort to their Medicare claims data, including claims from one year before the index hospitalization, so that we could calculate risk‐standardized readmission rates in this cohort separately using medical record and claims‐based models. This analysis was conducted at the state level, for the 50 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, because medical record data were unavailable in sufficient numbers to permit hospital‐level comparisons. To examine the relationship between risk‐standardized rates obtained from medical record and administrative data models, we estimated a linear regression model describing the association between the two rates, weighting each state by number of index hospitalizations, and calculated the correlation coefficient and the intercept and slope of this equation. A slope close to 1 and an intercept close to 0 would provide evidence that risk‐standardized state readmission rates from the medical record and claims models were similar. We also calculated the difference between state risk‐standardized readmission rates from the two models.

Analyses were conducted with the use of SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Models were fitted separately for the National Pneumonia Project and 2006 cohort. We estimated the hierarchical models using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS. The Human Investigation Committee at the Yale School of Medicine approved an exemption for the authors to use CMS claims and enrollment data for research analyses and publication.

RESULTS

Model Derivation and Performance

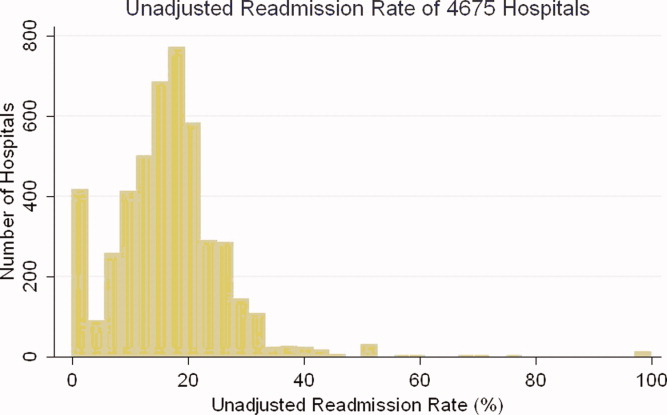

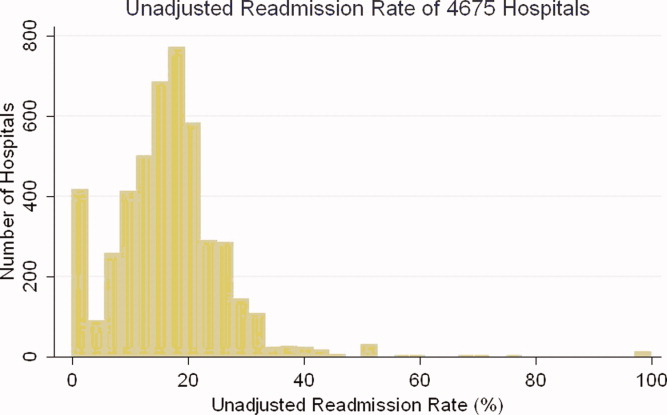

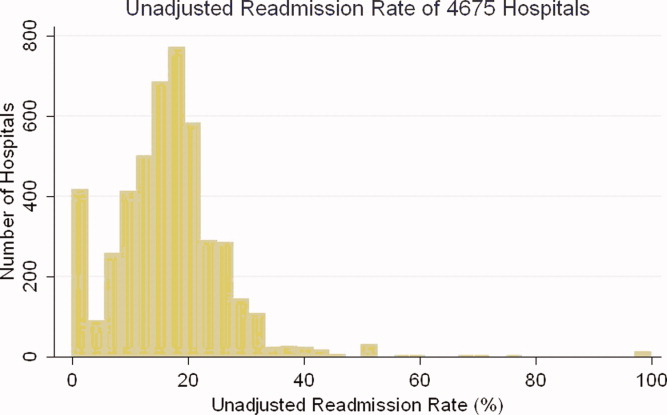

After exclusions were applied, the 2006 sample included 453,251 pneumonia hospitalizations (Figure 1). The development sample consisted of 226,545 hospitalizations at 4675 hospitals, with an overall unadjusted 30‐day readmission rate of 17.4%. In 11,694 index cases (5.2%), the patient died within 30 days without being readmitted. Median readmission rate was 16.3%, 25th and 75th percentile rates were 11.1% and 21.3%, and at the 10th and 90th percentile, hospital readmission rates ranged from 4.6% to 26.7% (Figure 2).

The claims model included 39 variables (age, sex, and 37 clinical variables) (Table 1). The mean age of the cohort was 80.0 years, with 55.5% women and 11.1% nonwhite patients. Mean observed readmission rate in the development sample ranged from 9% in the lowest decile of predicted pneumonia readmission rates to 32% in the highest predicted decile, a range of 23%. The AUC was 0.63. For comparison, a model with only age and sex had an AUC of 0.51, and a model with all candidate variables had an AUC equal to 0.63 (Table 2).

| Calibration (0, 1)* | Discrimination | Residuals Lack of Fit (Pearson Residual Fall %) | Model 2 (No. of Covariates) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Ability (Lowest Decile, Highest Decile) | AUC | (<2) | (2, 0) | (0, 2) | (2+) | ||||

| |||||||||

| Development sample | |||||||||

| 2006 | (1st half) N = 226,545 | (0, 1) | (0.09, 0.32) | 0.63 | 0 | 82.62 | 7.39 | 9.99 | 6,843 (40) |

| Validation sample | |||||||||

| 2006 | (2nd half) N = 226,706 | (0.002, 0.997) | (0.09, 0.31) | 0.63 | 0 | 82.55 | 7.45 | 9.99 | 6,870 (40) |

| 2005 | N = 536,015 | (0.035, 1.008) | (0.08, 0.31) | 0.63 | 0 | 82.67 | 7.31 | 10.03 | 16,241 (40) |

Hospital Risk‐Standardized Readmission Rates

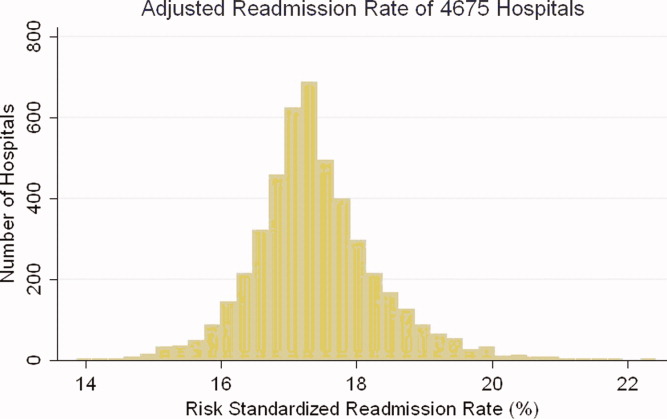

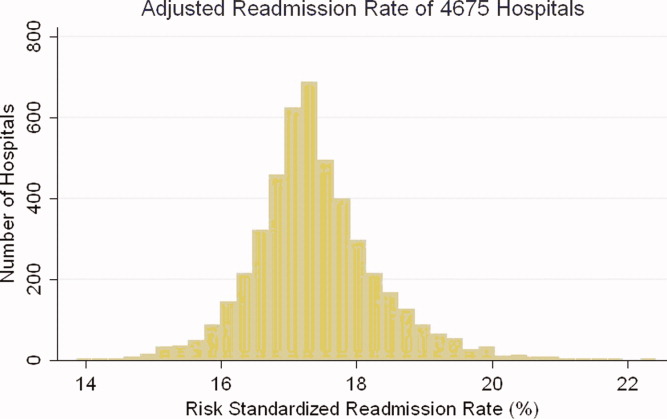

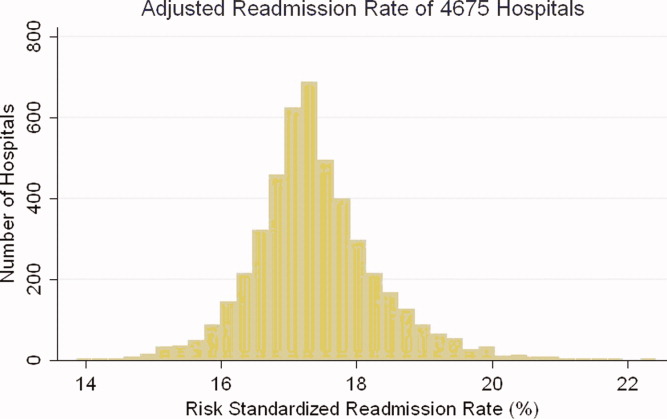

Risk‐standardized readmission rates varied across hospitals (Figure 3). Median risk‐standardized readmission rate was 17.3%, and the 25th and 75th percentiles were 16.9% and 17.9%, respectively. The 5th percentile was 16.0% and the 95th percentile was 19.1%. Odds of readmission for a hospital one standard deviation above average was 1.4 times that of a hospital one standard deviation below average.

Administrative Model Validation

In the remaining 50% of pneumonia index hospitalizations from 2006, and the entire 2005 cohort, regression coefficients and standard errors of model variables were similar to those in the development data set. Model performance using 2005 data was consistent with model performance using the 2006 development and validation half‐samples (Table 2).

Medical Record Validation

After exclusions, the medical record sample taken from the National Pneumonia Project included 47,429 cases, with an unadjusted 30‐day readmission rate of 17.0%. The final medical record risk‐adjustment model included a total of 35 variables, whose prevalence and association with readmission risk varied modestly (Table 3). Performance of the medical record and administrative models was similar (areas under the ROC curve 0.59 and 0.63, respectively) (Table 4). Additionally, in the administrative model, predicted readmission rates ranged from 8% in the lowest predicted decile to 30% in the highest predicted decile, while in the medical record model, the corresponding rates varied from 10% to 26%.

| Variable | Percent | Estimate | Standard Error | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Age 65, mean (SD) | 15.24 (7.87) | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.997 | 0.993 | 1.000 |

| Male | 46.18 | 0.122 | 0.025 | 1.130 | 1.075 | 1.188 |

| Nursing home resident | 17.71 | 0.035 | 0.037 | 1.036 | 0.963 | 1.114 |

| Neoplastic disease | 6.80 | 0.130 | 0.049 | 1.139 | 1.034 | 1.254 |

| Liver disease | 1.04 | 0.089 | 0.123 | 0.915 | 0.719 | 1.164 |

| History of heart failure | 28.98 | 0.234 | 0.029 | 1.264 | 1.194 | 1.339 |

| History of renal disease | 8.51 | 0.188 | 0.047 | 1.206 | 1.100 | 1.323 |

| Altered mental status | 17.95 | 0.009 | 0.034 | 1.009 | 0.944 | 1.080 |

| Pleural effusion | 21.20 | 0.165 | 0.030 | 1.179 | 1.111 | 1.251 |

| BUN 30 mg/dl | 23.28 | 0.160 | 0.033 | 1.174 | 1.100 | 1.252 |

| BUN missing | 14.56 | 0.101 | 0.185 | 0.904 | 0.630 | 1.298 |

| Systolic BP <90 mmHg | 2.95 | 0.068 | 0.070 | 1.070 | 0.932 | 1.228 |

| Systolic BP missing | 11.21 | 0.149 | 0.425 | 1.160 | 0.504 | 2.669 |

| Pulse 125/min | 7.73 | 0.036 | 0.047 | 1.036 | 0.945 | 1.137 |

| Pulse missing | 11.22 | 0.210 | 0.405 | 1.234 | 0.558 | 2.729 |

| Respiratory rate 30/min | 16.38 | 0.079 | 0.034 | 1.082 | 1.012 | 1.157 |

| Respiratory rate missing | 11.39 | 0.204 | 0.240 | 1.226 | 0.765 | 1.964 |

| Sodium <130 mmol/L | 4.82 | 0.136 | 0.057 | 1.145 | 1.025 | 1.280 |

| Sodium missing | 14.39 | 0.049 | 0.143 | 1.050 | 0.793 | 1.391 |

| Glucose 250 mg/dl | 5.19 | 0.005 | 0.057 | 0.995 | 0.889 | 1.114 |

| Glucose missing | 15.44 | 0.156 | 0.105 | 0.855 | 0.696 | 1.051 |

| Hematocrit <30% | 7.77 | 0.270 | 0.044 | 1.310 | 1.202 | 1.428 |

| Hematocrit missing | 13.62 | 0.071 | 0.135 | 0.932 | 0.715 | 1.215 |

| Creatinine 2.5 mg/dL | 4.68 | 0.109 | 0.062 | 1.115 | 0.989 | 1.258 |

| Creatinine missing | 14.63 | 0.200 | 0.167 | 1.221 | 0.880 | 1.695 |

| WBC 6‐12 b/L | 38.04 | 0.021 | 0.049 | 0.979 | 0.889 | 1.079 |

| WBC >12 b/L | 41.45 | 0.068 | 0.049 | 0.934 | 0.848 | 1.029 |

| WBC missing | 12.85 | 0.167 | 0.162 | 1.181 | 0.860 | 1.623 |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | 15.01 | 0.347 | 0.035 | 1.415 | 1.321 | 1.516 |

| Chronic lung disease | 42.16 | 0.137 | 0.028 | 1.147 | 1.086 | 1.211 |

| Coronary artery disease | 39.57 | 0.150 | 0.028 | 1.162 | 1.100 | 1.227 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20.90 | 0.137 | 0.033 | 1.147 | 1.076 | 1.223 |

| Alcohol/drug abuse | 3.40 | 0.099 | 0.071 | 0.906 | 0.788 | 1.041 |

| Dementia/Alzheimer's disease | 16.38 | 0.125 | 0.038 | 1.133 | 1.052 | 1.222 |

| Splenectomy | 0.44 | 0.016 | 0.186 | 1.016 | 0.706 | 1.463 |

| Model | Calibration (0, 1)* | Discrimination | Residuals Lack of Fit (Pearson Residual Fall %) | Model 2 (No. of Covariates) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Ability (Lowest Decile, Highest Decile) | AUC | (<2) | (2, 0) | (0, 2) | (2+) | |||

| ||||||||

| Medical Record Model Development Sample (NP) | ||||||||

| N = 47,429 No. of 30‐day readmissions = 8,042 | (1, 0) | (0.10, 0.26) | 0.59 | 0 | 83.04 | 5.28 | 11.68 | 710 (35) |

| Linked Administrative Model Validation Sample | ||||||||

| N = 47,429 No. of 30‐day readmissions = 8,042 | (1, 0) | (0.08, 0.30) | 0.63 | 0 | 83.04 | 6.94 | 10.01 | 1,414 (40) |

The correlation coefficient of the estimated state‐specific standardized readmission rates from the administrative and medical record models was 0.96, and the proportion of the variance explained by the model was 0.92 (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

We have described the development, validation, and results of a hospital, 30‐day, risk‐standardized readmission model for pneumonia that was created to support current federal transparency initiatives. The model uses administrative claims data from Medicare fee‐for‐service patients and produces results that are comparable to a model based on information obtained through manual abstraction of medical records. We observed an overall 30‐day readmission rate of 17%, and our analyses revealed substantial variation across US hospitals, suggesting that improvement by lower performing institutions is an achievable goal.

Because more than one in six pneumonia patients are rehospitalized shortly after discharge, and because pneumonia hospitalizations represent an enormous expense to the Medicare program, prevention of readmissions is now widely recognized to offer a substantial opportunity to improve patient outcomes while simultaneously lowering health care costs. Accordingly, promotion of strategies to reduce readmission rates has become a key priority for payers and quality‐improvement organizations. These range from policy‐level attempts to stimulate change, such as publicly reporting hospital readmission rates on government websites, to establishing accreditation standardssuch as the Joint Commission's requirement to accurately reconcile medications, to the creation of quality improvement collaboratives focused on sharing best practices across institutions. Regardless of the approach taken, a valid, risk‐adjusted measure of performance is required to evaluate and track performance over time. The measure we have described meets the National Quality Forum's measure evaluation criteria in that it addresses an important clinical topic for which there appears to be significant opportunities for improvement, the measure is precisely defined and has been subjected to validity and reliability testing, it is risk‐adjusted based on patient clinical factors present at the start of care, is feasible to produce, and is understandable by a broad range of potential users.21 Because hospitalists are the physicians primarily responsible for the care of patients with pneumonia at US hospitals, and because they frequently serve as the physician champions for quality improvement activities related to pneumonia, it is especially important that they maintain a thorough understanding of the measures and methodologies underlying current efforts to measure hospital performance.

Several features of our approach warrant additional comment. First, we deliberately chose to measure all readmission events rather than attempt to discriminate between potentially preventable and nonpreventable readmissions. From the patient perspective, readmission for any reason is a concern, and limiting the measure to pneumonia‐related readmissions could make it susceptible to gaming by hospitals. Moreover, determining whether a readmission is related to a potential quality problem is not straightforward. For example, a patient with pneumonia whose discharge medications were prescribed incorrectly may be readmitted with a hip fracture following an episode of syncope. It would be inappropriate to treat this readmission as unrelated to the care the patient received for pneumonia. Additionally, while our approach does not presume that every readmission is preventable, the goal is to reduce the risk of readmissions generally (not just in narrowly defined subpopulations), and successful interventions to reduce rehospitalization have typically demonstrated reductions in all‐cause readmission.9, 22 Second, deaths that occurred within 30 days of discharge, yet that were not accompanied by a hospital readmission, were not counted as a readmission outcome. While it may seem inappropriate to treat a postdischarge death as a nonevent (rather than censoring or excluding such cases), alternative analytic approaches, such as using a hierarchical survival model, are not currently computationally feasible with large national data sets. Fortunately, only a relatively small proportion of discharges fell into this category (5.2% of index cases in the 2006 development sample died within 30 days of discharge without being readmitted). An alternative approach to handling the competing outcome of death would have been to use a composite outcome of readmission or death. However, we believe that it is important to report the outcomes separately because factors that predict readmission and mortality may differ, and when making comparisons across hospitals it would not be possible to determine whether differences in rate were due to readmission or mortality. Third, while the patient‐level readmission model showed only modest discrimination, we intentionally excluded covariates such as race and socioeconomic status, as well as in‐hospital events and potential complications of care, and whether patients were discharged home or to a skilled nursing facility. While these variables could have improved predictive ability, they may be directly or indirectly related to quality or supply factors that should not be included in a model that seeks to control for patient clinical characteristics. For example, if hospitals with a large share of poor patients have higher readmission rates, then including income in the model will obscure differences that are important to identify. While we believe that the decision to exclude such factors in the model is in the best interest of patients, and supports efforts to reduce health inequality in society more generally, we also recognize that hospitals that care for a disproportionate share of poor patients are likely to require additional resources to overcome these social factors. Fourth, we limited the analysis to patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia, and chose not to also include those with a principal diagnosis of sepsis or respiratory failure coupled with a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia. While the broader definition is used by CMS in the National Pneumonia Project, that initiative relied on chart abstraction to differentiate pneumonia present at the time of admission from cases developing as a complication of hospitalization. Additionally, we did not attempt to differentiate between community‐acquired and healthcare‐associated pneumonia, however our approach is consistent with the National Pneumonia Project and Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team.18 Fifth, while our model estimates readmission rates at the hospital level, we recognize that readmissions are influenced by a complex and extensive range of factors. In this context, greater cooperation between hospitals and other care providers will almost certainly be required in order to achieve dramatic improvement in readmission rates, which in turn will depend upon changes to the way serious illness is paid for. Some options that have recently been described include imposing financial penalties for early readmission, extending the boundaries of case‐based payment beyond hospital discharge, and bundling payments between hospitals and physicians.2325

Our measure has several limitations. First, our models were developed and validated using Medicare data, and the results may not apply to pneumonia patients less than 65 years of age. However, most patients hospitalized with pneumonia in the US are 65 or older. In addition, we were unable to test the model with a Medicare managed care population, because data are not currently available on such patients. Finally, the medical record‐based validation was conducted by state‐level analysis because the sample size was insufficient to carry this out at the hospital level.

In conclusion, more than 17% of Medicare beneficiaries are readmitted within 30 days following discharge after a hospitalization for pneumonia, and rates vary substantially across institutions. The development of a valid measure of hospital performance and public reporting are important first steps towards focusing attention on this problem. Actual improvement will now depend on whether hospitals and partner organizations are successful at identifying and implementing effective methods to prevent readmission.

- ,,.Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare Fee‐for‐Service Program.N Engl J Med.2009;360(14):1418–1428.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.Report to the Congress: Promoting Greater Efficiency in Medicare.2007.

- ,,,,. HCUP Facts and Figures: Statistics on Hospital‐based Care in the United States, 2007.2009. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports.jsp. Accessed November 7, 2009.

- Centers for Medicare 353(3):255–264.

- ,,,.Trends in postdischarge mortality and readmissions: has length of stay declined too far?Arch Intern Med.2004;164(5):538–544.

- ,,,.Short‐term outcomes and their predictors for patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia.Heart Lung.2004;33(5):301–307.

- ,,, et al.Improved clinical outcomes with utilization of a community‐acquired pneumonia guideline.Chest.2006;130(3):794–799.

- ,,,,.Associations between initial antimicrobial therapy and medical outcomes for hospitalized elderly patients with pneumonia.Arch Intern Med.1999;159(21):2562–2572.

- ,.Hospital readmissions as a measure of quality of health care: advantages and limitations.Arch Intern Med.2000;160(8):1074–1081.

- ,,,.The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial.Arch Intern Med.2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- Corrigan JM, Eden J, Smith BM, eds.Leadership by Example: Coordinating Government Roles in Improving Health Care Quality. Committee on Enhancing Federal Healthcare Quality Programs.Washington, DC:National Academies Press,2003.

- Medicare.gov—Hospital Compare. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/Hospital/Search/Welcome.asp?version=default1(1):29–37.

- ,,,,.Measuring performance for treating heart attacks and heart failure: the case for outcomes measurement.Health Aff.2007;26(1):75–85.

- NQF‐Endorsed® Standards. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Measures_List.aspx. Accessed November 6,2009.

- ,,,,.Timing of antibiotic administration and outcomes for Medicare patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia.Arch Intern Med.2004;164(6):637–644.

- ,,. Diagnostic Cost Group Hierarchical Condition Category Models for Medicare Risk Adjustment. Report prepared for the Health Care Financing Administration. Health Economics Research, Inc;2000. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/Reports/Reports/ItemDetail.asp?ItemID=CMS023176. Accessed November 7, 2009.

- .Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis.1st ed.New York:Springer;2006.

- National Quality Forum—Measure Evaluation Criteria.2008. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/uploadedFiles/Quality_Forum/Measuring_Performance/Consensus_Development_Process%E2%80%99s_Principle/EvalCriteria2008–08‐28Final.pdf?n=4701.

- ,,, et al.Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow‐up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial.JAMA.1999;281(7):613–620.

- .Paying for care episodes and care coordination.N Engl J Med.2007;356(11):1166–1168.

- .Health care reform—toward more freedom, and responsibility, for physicians.N Engl J Med.2009;361(6):623–628.

- .Beyond pay for performance—emerging models of provider‐payment reform.N Engl J Med.2008;359(12):1197–1200.

Hospital readmissions are emblematic of the numerous challenges facing the US health care system. Despite high levels of spending, nearly 20% of Medicare beneficiaries are readmitted within 30 days of hospital discharge, many readmissions are considered preventable, and rates vary widely by hospital and region.1 Further, while readmissions have been estimated to cost taxpayers as much as $17 billion annually, the current fee‐for‐service method of paying for the acute care needs of seniors rewards hospitals financially for readmission, not their prevention.2

Pneumonia is the second most common reason for hospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries, accounting for approximately 650,000 admissions annually,3 and has been a focus of national quality‐improvement efforts for more than a decade.4, 5 Despite improvements in key processes of care, rates of readmission within 30 days of discharge following a hospitalization for pneumonia have been reported to vary from 10% to 24%.68 Among several factors, readmissions are believed to be influenced by the quality of both inpatient and outpatient care, and by care‐coordination activities occurring in the transition from inpatient to outpatient status.912

Public reporting of hospital performance is considered a key strategy for improving quality, reducing costs, and increasing the value of hospital care, both in the US and worldwide.13 In 2009, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded its reporting initiatives by adding risk‐adjusted hospital readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia to the Hospital Compare website.14, 15 Readmission rates are an attractive focus for public reporting for several reasons. First, in contrast to most process‐based measures of quality (eg, whether a patient with pneumonia received a particular antibiotic), a readmission is an adverse outcome that matters to patients and families.16 Second, unlike process measures whose assessment requires detailed review of medical records, readmissions can be easily determined from standard hospital claims. Finally, readmissions are costly, and their prevention could yield substantial savings to society.

A necessary prerequisite for public reporting of readmission is a validated, risk‐adjusted measure that can be used to track performance over time and can facilitate comparisons across institutions. Toward this end, we describe the development, validation, and results of a National Quality Forum‐approved and CMS‐adopted model to estimate hospital‐specific, risk‐standardized, 30‐day readmission rates for Medicare patients hospitalized with pneumonia.17

METHODS

Data Sources

We used 20052006 claims data from Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and carrier (physician) Standard Analytic Files to develop and validate the administrative model. The Medicare Enrollment Database was used to determine Medicare fee‐for‐service enrollment and mortality statuses. A medical record model, used for additional validation of the administrative model, was developed using information abstracted from the charts of 75,616 pneumonia cases from 19982001 as part of the National Pneumonia Project, a CMS quality improvement initiative.18

Study Cohort

We identified hospitalizations of patients 65 years of age and older with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes 480.XX, 481, 482.XX, 483.X, 485, 486, 487.0) as potential index pneumonia admissions. Because our focus was readmission for patients discharged from acute care settings, we excluded admissions in which patients died or were transferred to another acute care facility. Additionally, we restricted analysis to patients who had been enrolled in fee‐for‐service Medicare Parts A and B, for at least 12 months prior to their pneumonia hospitalization, so that we could use diagnostic codes from all inpatient and outpatient encounters during that period to enhance identification of comorbidities.

Outcome

The outcome was 30‐day readmission, defined as occurrence of at least one hospitalization for any cause within 30 days of discharge after an index admission. Readmissions were identified from hospital claims data, and were attributed to the hospital that had discharged the patient. A 30‐day time frame was selected because it is a clinically meaningful period during which hospitals can be expected to collaborate with other organizations and providers to implement measures to reduce the risk of rehospitalization.

Candidate and Final Model Variables

Candidate variables for the administrative claims model were selected by a clinician team from 189 diagnostic groups included in the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) clinical classification system.19 The HCC clinical classification system was developed for CMS in preparation for all‐encounter risk adjustment for Medicare Advantage (managed care). Under the HCC algorithm, the 15,000+ ICD‐9‐CM diagnosis codes are assigned to one of 189 clinically‐coherent condition categories (CCs). We used the April 2008 version of the ICD‐9‐CM to CC assignment map, which is maintained by CMS and posted at

The final risk‐adjustment model included 39 variables selected by the team of clinicians and analysts, primarily based on their clinical relevance but also with knowledge of the strength of their statistical association with readmission outcome (Table 1). For each patient, the presence or absence of these conditions was assessed from multiple sources, including secondary diagnoses during the index admission, principal and secondary diagnoses from hospital admissions in the 12 months prior to the index admission, and diagnoses from hospital outpatient and physician encounters 12 months before the index admission. A small number of CCs were considered to represent potential complications of care (eg, bleeding). Because we did not want to adjust for complications of care occurring during the index admission, a patient was not considered to have one of these conditions unless it was also present in at least one encounter prior to the index admission.

| Variable | Frequencies | Estimate | Standard Error | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Intercept | 2.395 | 0.021 | ||||

| Age 65 (years above 65, continuous) | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.001 | |

| Male | 45 | 0.071 | 0.012 | 1.073 | 1.048 | 1.099 |

| History of CABG | 5.2 | 0.179 | 0.027 | 0.836 | 0.793 | 0.881 |

| Metastatic cancer and acute leukemia (CC 7) | 4.3 | 0.177 | 0.029 | 1.194 | 1.128 | 1.263 |

| Lung, upper digestive tract, and other severe cancers (CC 8) | 6.0 | 0.256 | 0.024 | 1.292 | 1.232 | 1.354 |

| Diabetes and DM complications (CC 15‐20, 119, 120) | 36 | 0.059 | 0.012 | 1.061 | 1.036 | 1.087 |

| Disorders of fluid/electrolyte/acid‐base (CC 22, 23) | 34 | 0.149 | 0.013 | 1.160 | 1.131 | 1.191 |

| Iron deficiency and other/unspecified anemias and blood disease (CC 47) | 46 | 0.118 | 0.012 | 1.126 | 1.099 | 1.153 |

| Other psychiatric disorders (CC 60) | 12 | 0.108 | 0.017 | 1.114 | 1.077 | 1.151 |

| Cardio‐respiratory failure and shock (CC 79) | 16 | 0.114 | 0.016 | 1.121 | 1.087 | 1.156 |

| Congestive heart failure (CC 80) | 39 | 0.151 | 0.014 | 1.163 | 1.133 | 1.194 |

| Chronic atherosclerosis (CC 83, 84) | 47 | 0.051 | 0.013 | 1.053 | 1.027 | 1.079 |

| Valvular and rheumatic heart disease (CC 86) | 23 | 0.062 | 0.014 | 1.064 | 1.036 | 1.093 |

| Arrhythmias (CC 92, 93) | 38 | 0.126 | 0.013 | 1.134 | 1.107 | 1.163 |

| Vascular or circulatory disease (CC 104‐106) | 38 | 0.088 | 0.012 | 1.092 | 1.066 | 1.119 |

| COPD (CC 108) | 58 | 0.186 | 0.013 | 1.205 | 1.175 | 1.235 |

| Fibrosis of lung and other chronic lung disorders (CC 109) | 17 | 0.086 | 0.015 | 1.090 | 1.059 | 1.122 |

| Renal failure (CC 131) | 17 | 0.147 | 0.016 | 1.158 | 1.122 | 1.196 |

| Protein‐calorie malnutrition (CC 21) | 7.9 | 0.121 | 0.020 | 1.129 | 1.086 | 1.173 |

| History of infection (CC 1, 3‐6) | 35 | 0.068 | 0.012 | 1.071 | 1.045 | 1.097 |

| Severe hematological disorders (CC 44) | 3.6 | 0.117 | 0.028 | 1.125 | 1.064 | 1.188 |

| Decubitus ulcer or chronic skin ulcer (CC 148, 149) | 10 | 0.101 | 0.018 | 1.106 | 1.067 | 1.146 |

| History of pneumonia (CC 111‐113) | 44 | 0.065 | 0.013 | 1.067 | 1.041 | 1.094 |

| Vertebral fractures (CC 157) | 5.1 | 0.113 | 0.024 | 1.120 | 1.068 | 1.174 |

| Other injuries (CC 162) | 32 | 0.061 | 0.012 | 1.063 | 1.038 | 1.089 |

| Urinary tract infection (CC 135) | 26 | 0.064 | 0.014 | 1.066 | 1.038 | 1.095 |

| Lymphatic, head and neck, brain, and other major cancers; breast, prostate, colorectal, and other cancers and tumors (CC 9‐10) | 16 | 0.050 | 0.016 | 1.051 | 1.018 | 1.084 |

| End‐stage renal disease or dialysis (CC 129, 130) | 1.9 | 0.131 | 0.037 | 1.140 | 1.060 | 1.226 |

| Drug/alcohol abuse/dependence/psychosis (CC 51‐53) | 12 | 0.081 | 0.017 | 1.084 | 1.048 | 1.121 |

| Septicemia/shock (CC 2) | 6.3 | 0.094 | 0.022 | 1.098 | 1.052 | 1.146 |

| Other gastrointestinal disorders (CC 36) | 56 | 0.073 | 0.012 | 1.076 | 1.051 | 1.102 |

| Acute coronary syndrome (CC 81, 82) | 8.3 | 0.126 | 0.019 | 1.134 | 1.092 | 1.178 |

| Pleural effusion/pneumothorax (CC 114) | 12 | 0.083 | 0.017 | 1.086 | 1.051 | 1.123 |

| Other urinary tract disorders (CC 136) | 24 | 0.059 | 0.014 | 1.061 | 1.033 | 1.090 |

| Stroke (CC 95, 96) | 10 | 0.047 | 0.019 | 1.049 | 1.011 | 1.088 |

| Dementia and senility (CC 49, 50) | 27 | 0.031 | 0.014 | 1.031 | 1.004 | 1.059 |

| Hemiplegia, paraplegia, paralysis, functional disability (CC 67‐69, 100‐102, 177, 178) | 7.4 | 0.068 | 0.021 | 1.070 | 1.026 | 1.116 |

| Other lung disorders (CC 115) | 45 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 1.005 | 0.982 | 1.030 |

| Major psychiatric disorders (CC 54‐56) | 11 | 0.038 | 0.018 | 1.038 | 1.003 | 1.075 |

| Asthma (CC 110) | 12 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 1.006 | 0.972 | 1.041 |

Model Derivation

For the development of the administrative claims model, we randomly sampled half of 2006 hospitalizations that met inclusion criteria. To assess model performance at the patient level, we calculated the area under the receiver operating curve (AUC), and calculated observed readmission rates in the lowest and highest deciles on the basis of predicted readmission probabilities. We also compared performance with a null model, a model that adjusted for age and sex, and a model that included all candidate variables.20

Risk‐Standardized Readmission Rates

Using hierarchical logistic regression, we modeled the log‐odds of readmission within 30 days of discharge from an index pneumonia admission as a function of patient demographic and clinical characteristics, and a random hospital‐specific intercept. This strategy accounts for within‐hospital correlation, or clustering, of observed outcomes, and models the assumption that underlying differences in quality among hospitals being evaluated lead to systematic differences in outcomes. We then calculated hospital‐specific readmission rates as the ratio of predicted‐to‐expected readmissions (similar to observed/expected ratio), multiplied by the national unadjusted ratea form of indirect standardization. Predicted number of readmissions in each hospital is estimated given the same patient mix and its estimated hospital‐specific intercept. Expected number of readmissions in each hospital is estimated using its patient mix and the average hospital‐specific intercept. To assess hospital performance in any given year, we re‐estimate model coefficients using that year's data.

Model Validation: Administrative Claims

We compared the model performance in the development sample with its performance in the sample from the 2006 data that was not selected for the development set, and separately among pneumonia admissions in 2005. The model was recalibrated in each validation set.

Model Validation: Medical Record Abstraction

We developed a separate medical record‐based model of readmission risk using information from charts that had previously been abstracted as part of CMS's National Pneumonia Project. To select variables for this model, the clinician team: 1) reviewed the list of variables that were included in a medical record model that was previously developed for validating the National Quality Forum‐approved pneumonia mortality measure; 2) reviewed a list of other potential candidate variables available in the National Pneumonia Project dataset; and 3) reviewed variables that emerged as potentially important predictors of readmission, based on a systematic review of the literature that was conducted as part of measure development. This selection process resulted in a final medical record model that included 35 variables.

We linked patients in the National Pneumonia Project cohort to their Medicare claims data, including claims from one year before the index hospitalization, so that we could calculate risk‐standardized readmission rates in this cohort separately using medical record and claims‐based models. This analysis was conducted at the state level, for the 50 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, because medical record data were unavailable in sufficient numbers to permit hospital‐level comparisons. To examine the relationship between risk‐standardized rates obtained from medical record and administrative data models, we estimated a linear regression model describing the association between the two rates, weighting each state by number of index hospitalizations, and calculated the correlation coefficient and the intercept and slope of this equation. A slope close to 1 and an intercept close to 0 would provide evidence that risk‐standardized state readmission rates from the medical record and claims models were similar. We also calculated the difference between state risk‐standardized readmission rates from the two models.

Analyses were conducted with the use of SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Models were fitted separately for the National Pneumonia Project and 2006 cohort. We estimated the hierarchical models using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS. The Human Investigation Committee at the Yale School of Medicine approved an exemption for the authors to use CMS claims and enrollment data for research analyses and publication.

RESULTS

Model Derivation and Performance

After exclusions were applied, the 2006 sample included 453,251 pneumonia hospitalizations (Figure 1). The development sample consisted of 226,545 hospitalizations at 4675 hospitals, with an overall unadjusted 30‐day readmission rate of 17.4%. In 11,694 index cases (5.2%), the patient died within 30 days without being readmitted. Median readmission rate was 16.3%, 25th and 75th percentile rates were 11.1% and 21.3%, and at the 10th and 90th percentile, hospital readmission rates ranged from 4.6% to 26.7% (Figure 2).

The claims model included 39 variables (age, sex, and 37 clinical variables) (Table 1). The mean age of the cohort was 80.0 years, with 55.5% women and 11.1% nonwhite patients. Mean observed readmission rate in the development sample ranged from 9% in the lowest decile of predicted pneumonia readmission rates to 32% in the highest predicted decile, a range of 23%. The AUC was 0.63. For comparison, a model with only age and sex had an AUC of 0.51, and a model with all candidate variables had an AUC equal to 0.63 (Table 2).

| Calibration (0, 1)* | Discrimination | Residuals Lack of Fit (Pearson Residual Fall %) | Model 2 (No. of Covariates) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Ability (Lowest Decile, Highest Decile) | AUC | (<2) | (2, 0) | (0, 2) | (2+) | ||||

| |||||||||

| Development sample | |||||||||

| 2006 | (1st half) N = 226,545 | (0, 1) | (0.09, 0.32) | 0.63 | 0 | 82.62 | 7.39 | 9.99 | 6,843 (40) |

| Validation sample | |||||||||

| 2006 | (2nd half) N = 226,706 | (0.002, 0.997) | (0.09, 0.31) | 0.63 | 0 | 82.55 | 7.45 | 9.99 | 6,870 (40) |

| 2005 | N = 536,015 | (0.035, 1.008) | (0.08, 0.31) | 0.63 | 0 | 82.67 | 7.31 | 10.03 | 16,241 (40) |

Hospital Risk‐Standardized Readmission Rates

Risk‐standardized readmission rates varied across hospitals (Figure 3). Median risk‐standardized readmission rate was 17.3%, and the 25th and 75th percentiles were 16.9% and 17.9%, respectively. The 5th percentile was 16.0% and the 95th percentile was 19.1%. Odds of readmission for a hospital one standard deviation above average was 1.4 times that of a hospital one standard deviation below average.

Administrative Model Validation

In the remaining 50% of pneumonia index hospitalizations from 2006, and the entire 2005 cohort, regression coefficients and standard errors of model variables were similar to those in the development data set. Model performance using 2005 data was consistent with model performance using the 2006 development and validation half‐samples (Table 2).

Medical Record Validation

After exclusions, the medical record sample taken from the National Pneumonia Project included 47,429 cases, with an unadjusted 30‐day readmission rate of 17.0%. The final medical record risk‐adjustment model included a total of 35 variables, whose prevalence and association with readmission risk varied modestly (Table 3). Performance of the medical record and administrative models was similar (areas under the ROC curve 0.59 and 0.63, respectively) (Table 4). Additionally, in the administrative model, predicted readmission rates ranged from 8% in the lowest predicted decile to 30% in the highest predicted decile, while in the medical record model, the corresponding rates varied from 10% to 26%.

| Variable | Percent | Estimate | Standard Error | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Age 65, mean (SD) | 15.24 (7.87) | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.997 | 0.993 | 1.000 |

| Male | 46.18 | 0.122 | 0.025 | 1.130 | 1.075 | 1.188 |

| Nursing home resident | 17.71 | 0.035 | 0.037 | 1.036 | 0.963 | 1.114 |

| Neoplastic disease | 6.80 | 0.130 | 0.049 | 1.139 | 1.034 | 1.254 |

| Liver disease | 1.04 | 0.089 | 0.123 | 0.915 | 0.719 | 1.164 |

| History of heart failure | 28.98 | 0.234 | 0.029 | 1.264 | 1.194 | 1.339 |

| History of renal disease | 8.51 | 0.188 | 0.047 | 1.206 | 1.100 | 1.323 |

| Altered mental status | 17.95 | 0.009 | 0.034 | 1.009 | 0.944 | 1.080 |

| Pleural effusion | 21.20 | 0.165 | 0.030 | 1.179 | 1.111 | 1.251 |

| BUN 30 mg/dl | 23.28 | 0.160 | 0.033 | 1.174 | 1.100 | 1.252 |

| BUN missing | 14.56 | 0.101 | 0.185 | 0.904 | 0.630 | 1.298 |

| Systolic BP <90 mmHg | 2.95 | 0.068 | 0.070 | 1.070 | 0.932 | 1.228 |

| Systolic BP missing | 11.21 | 0.149 | 0.425 | 1.160 | 0.504 | 2.669 |

| Pulse 125/min | 7.73 | 0.036 | 0.047 | 1.036 | 0.945 | 1.137 |

| Pulse missing | 11.22 | 0.210 | 0.405 | 1.234 | 0.558 | 2.729 |

| Respiratory rate 30/min | 16.38 | 0.079 | 0.034 | 1.082 | 1.012 | 1.157 |

| Respiratory rate missing | 11.39 | 0.204 | 0.240 | 1.226 | 0.765 | 1.964 |

| Sodium <130 mmol/L | 4.82 | 0.136 | 0.057 | 1.145 | 1.025 | 1.280 |

| Sodium missing | 14.39 | 0.049 | 0.143 | 1.050 | 0.793 | 1.391 |

| Glucose 250 mg/dl | 5.19 | 0.005 | 0.057 | 0.995 | 0.889 | 1.114 |

| Glucose missing | 15.44 | 0.156 | 0.105 | 0.855 | 0.696 | 1.051 |

| Hematocrit <30% | 7.77 | 0.270 | 0.044 | 1.310 | 1.202 | 1.428 |

| Hematocrit missing | 13.62 | 0.071 | 0.135 | 0.932 | 0.715 | 1.215 |

| Creatinine 2.5 mg/dL | 4.68 | 0.109 | 0.062 | 1.115 | 0.989 | 1.258 |

| Creatinine missing | 14.63 | 0.200 | 0.167 | 1.221 | 0.880 | 1.695 |

| WBC 6‐12 b/L | 38.04 | 0.021 | 0.049 | 0.979 | 0.889 | 1.079 |

| WBC >12 b/L | 41.45 | 0.068 | 0.049 | 0.934 | 0.848 | 1.029 |

| WBC missing | 12.85 | 0.167 | 0.162 | 1.181 | 0.860 | 1.623 |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | 15.01 | 0.347 | 0.035 | 1.415 | 1.321 | 1.516 |

| Chronic lung disease | 42.16 | 0.137 | 0.028 | 1.147 | 1.086 | 1.211 |

| Coronary artery disease | 39.57 | 0.150 | 0.028 | 1.162 | 1.100 | 1.227 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20.90 | 0.137 | 0.033 | 1.147 | 1.076 | 1.223 |

| Alcohol/drug abuse | 3.40 | 0.099 | 0.071 | 0.906 | 0.788 | 1.041 |

| Dementia/Alzheimer's disease | 16.38 | 0.125 | 0.038 | 1.133 | 1.052 | 1.222 |

| Splenectomy | 0.44 | 0.016 | 0.186 | 1.016 | 0.706 | 1.463 |

| Model | Calibration (0, 1)* | Discrimination | Residuals Lack of Fit (Pearson Residual Fall %) | Model 2 (No. of Covariates) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Ability (Lowest Decile, Highest Decile) | AUC | (<2) | (2, 0) | (0, 2) | (2+) | |||

| ||||||||

| Medical Record Model Development Sample (NP) | ||||||||

| N = 47,429 No. of 30‐day readmissions = 8,042 | (1, 0) | (0.10, 0.26) | 0.59 | 0 | 83.04 | 5.28 | 11.68 | 710 (35) |

| Linked Administrative Model Validation Sample | ||||||||

| N = 47,429 No. of 30‐day readmissions = 8,042 | (1, 0) | (0.08, 0.30) | 0.63 | 0 | 83.04 | 6.94 | 10.01 | 1,414 (40) |

The correlation coefficient of the estimated state‐specific standardized readmission rates from the administrative and medical record models was 0.96, and the proportion of the variance explained by the model was 0.92 (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

We have described the development, validation, and results of a hospital, 30‐day, risk‐standardized readmission model for pneumonia that was created to support current federal transparency initiatives. The model uses administrative claims data from Medicare fee‐for‐service patients and produces results that are comparable to a model based on information obtained through manual abstraction of medical records. We observed an overall 30‐day readmission rate of 17%, and our analyses revealed substantial variation across US hospitals, suggesting that improvement by lower performing institutions is an achievable goal.

Because more than one in six pneumonia patients are rehospitalized shortly after discharge, and because pneumonia hospitalizations represent an enormous expense to the Medicare program, prevention of readmissions is now widely recognized to offer a substantial opportunity to improve patient outcomes while simultaneously lowering health care costs. Accordingly, promotion of strategies to reduce readmission rates has become a key priority for payers and quality‐improvement organizations. These range from policy‐level attempts to stimulate change, such as publicly reporting hospital readmission rates on government websites, to establishing accreditation standardssuch as the Joint Commission's requirement to accurately reconcile medications, to the creation of quality improvement collaboratives focused on sharing best practices across institutions. Regardless of the approach taken, a valid, risk‐adjusted measure of performance is required to evaluate and track performance over time. The measure we have described meets the National Quality Forum's measure evaluation criteria in that it addresses an important clinical topic for which there appears to be significant opportunities for improvement, the measure is precisely defined and has been subjected to validity and reliability testing, it is risk‐adjusted based on patient clinical factors present at the start of care, is feasible to produce, and is understandable by a broad range of potential users.21 Because hospitalists are the physicians primarily responsible for the care of patients with pneumonia at US hospitals, and because they frequently serve as the physician champions for quality improvement activities related to pneumonia, it is especially important that they maintain a thorough understanding of the measures and methodologies underlying current efforts to measure hospital performance.

Several features of our approach warrant additional comment. First, we deliberately chose to measure all readmission events rather than attempt to discriminate between potentially preventable and nonpreventable readmissions. From the patient perspective, readmission for any reason is a concern, and limiting the measure to pneumonia‐related readmissions could make it susceptible to gaming by hospitals. Moreover, determining whether a readmission is related to a potential quality problem is not straightforward. For example, a patient with pneumonia whose discharge medications were prescribed incorrectly may be readmitted with a hip fracture following an episode of syncope. It would be inappropriate to treat this readmission as unrelated to the care the patient received for pneumonia. Additionally, while our approach does not presume that every readmission is preventable, the goal is to reduce the risk of readmissions generally (not just in narrowly defined subpopulations), and successful interventions to reduce rehospitalization have typically demonstrated reductions in all‐cause readmission.9, 22 Second, deaths that occurred within 30 days of discharge, yet that were not accompanied by a hospital readmission, were not counted as a readmission outcome. While it may seem inappropriate to treat a postdischarge death as a nonevent (rather than censoring or excluding such cases), alternative analytic approaches, such as using a hierarchical survival model, are not currently computationally feasible with large national data sets. Fortunately, only a relatively small proportion of discharges fell into this category (5.2% of index cases in the 2006 development sample died within 30 days of discharge without being readmitted). An alternative approach to handling the competing outcome of death would have been to use a composite outcome of readmission or death. However, we believe that it is important to report the outcomes separately because factors that predict readmission and mortality may differ, and when making comparisons across hospitals it would not be possible to determine whether differences in rate were due to readmission or mortality. Third, while the patient‐level readmission model showed only modest discrimination, we intentionally excluded covariates such as race and socioeconomic status, as well as in‐hospital events and potential complications of care, and whether patients were discharged home or to a skilled nursing facility. While these variables could have improved predictive ability, they may be directly or indirectly related to quality or supply factors that should not be included in a model that seeks to control for patient clinical characteristics. For example, if hospitals with a large share of poor patients have higher readmission rates, then including income in the model will obscure differences that are important to identify. While we believe that the decision to exclude such factors in the model is in the best interest of patients, and supports efforts to reduce health inequality in society more generally, we also recognize that hospitals that care for a disproportionate share of poor patients are likely to require additional resources to overcome these social factors. Fourth, we limited the analysis to patients with a principal diagnosis of pneumonia, and chose not to also include those with a principal diagnosis of sepsis or respiratory failure coupled with a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia. While the broader definition is used by CMS in the National Pneumonia Project, that initiative relied on chart abstraction to differentiate pneumonia present at the time of admission from cases developing as a complication of hospitalization. Additionally, we did not attempt to differentiate between community‐acquired and healthcare‐associated pneumonia, however our approach is consistent with the National Pneumonia Project and Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team.18 Fifth, while our model estimates readmission rates at the hospital level, we recognize that readmissions are influenced by a complex and extensive range of factors. In this context, greater cooperation between hospitals and other care providers will almost certainly be required in order to achieve dramatic improvement in readmission rates, which in turn will depend upon changes to the way serious illness is paid for. Some options that have recently been described include imposing financial penalties for early readmission, extending the boundaries of case‐based payment beyond hospital discharge, and bundling payments between hospitals and physicians.2325

Our measure has several limitations. First, our models were developed and validated using Medicare data, and the results may not apply to pneumonia patients less than 65 years of age. However, most patients hospitalized with pneumonia in the US are 65 or older. In addition, we were unable to test the model with a Medicare managed care population, because data are not currently available on such patients. Finally, the medical record‐based validation was conducted by state‐level analysis because the sample size was insufficient to carry this out at the hospital level.

In conclusion, more than 17% of Medicare beneficiaries are readmitted within 30 days following discharge after a hospitalization for pneumonia, and rates vary substantially across institutions. The development of a valid measure of hospital performance and public reporting are important first steps towards focusing attention on this problem. Actual improvement will now depend on whether hospitals and partner organizations are successful at identifying and implementing effective methods to prevent readmission.

Hospital readmissions are emblematic of the numerous challenges facing the US health care system. Despite high levels of spending, nearly 20% of Medicare beneficiaries are readmitted within 30 days of hospital discharge, many readmissions are considered preventable, and rates vary widely by hospital and region.1 Further, while readmissions have been estimated to cost taxpayers as much as $17 billion annually, the current fee‐for‐service method of paying for the acute care needs of seniors rewards hospitals financially for readmission, not their prevention.2

Pneumonia is the second most common reason for hospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries, accounting for approximately 650,000 admissions annually,3 and has been a focus of national quality‐improvement efforts for more than a decade.4, 5 Despite improvements in key processes of care, rates of readmission within 30 days of discharge following a hospitalization for pneumonia have been reported to vary from 10% to 24%.68 Among several factors, readmissions are believed to be influenced by the quality of both inpatient and outpatient care, and by care‐coordination activities occurring in the transition from inpatient to outpatient status.912

Public reporting of hospital performance is considered a key strategy for improving quality, reducing costs, and increasing the value of hospital care, both in the US and worldwide.13 In 2009, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded its reporting initiatives by adding risk‐adjusted hospital readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia to the Hospital Compare website.14, 15 Readmission rates are an attractive focus for public reporting for several reasons. First, in contrast to most process‐based measures of quality (eg, whether a patient with pneumonia received a particular antibiotic), a readmission is an adverse outcome that matters to patients and families.16 Second, unlike process measures whose assessment requires detailed review of medical records, readmissions can be easily determined from standard hospital claims. Finally, readmissions are costly, and their prevention could yield substantial savings to society.

A necessary prerequisite for public reporting of readmission is a validated, risk‐adjusted measure that can be used to track performance over time and can facilitate comparisons across institutions. Toward this end, we describe the development, validation, and results of a National Quality Forum‐approved and CMS‐adopted model to estimate hospital‐specific, risk‐standardized, 30‐day readmission rates for Medicare patients hospitalized with pneumonia.17

METHODS

Data Sources

We used 20052006 claims data from Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and carrier (physician) Standard Analytic Files to develop and validate the administrative model. The Medicare Enrollment Database was used to determine Medicare fee‐for‐service enrollment and mortality statuses. A medical record model, used for additional validation of the administrative model, was developed using information abstracted from the charts of 75,616 pneumonia cases from 19982001 as part of the National Pneumonia Project, a CMS quality improvement initiative.18

Study Cohort