User login

RIT can improve transplant outcomes in NHL, CLL

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS—Administering radioimmunotherapy (RIT) prior to non-myeloablative allogeneic transplant (NMAT) can improve survival in patients with persistent disease, according to a speaker at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings.

Ryan Cassaday, MD, of the University of Washington in Seattle, noted that RIT-augmented NMAT can produce long-term remissions in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

But outcomes for patients with persistent disease are “underdescribed.”

So he and his colleagues set out to describe outcomes of NMAT for patients with persistent indolent B-NHL or CLL and estimate the impact of RIT in these patients.

Treatment details

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data from 89 patients who underwent NMAT from December 1998 to April 2009 and were followed until September 2013. Eighteen of the patients had received RIT as part of a prospective study (AK Gopal et al, Blood 2011).

The remaining 71 patients did not receive RIT but met eligibility criteria for that study. Specifically, they had a CD20+ B-cell malignancy, an HLA-matched peripheral blood stem cell donor, and persistent disease at NMAT. These control subjects received fludarabine (30 mg/m2 on days -7, -6, and -5) and 2 Gy of total body irradiation prior to NMAT.

Patients in the RIT group received the same treatment following RIT. On day -21, they received 250 mg/m2 of rituximab before an imaging dose of 111In-ibritumomab tiuxetan. And on day -14, they received 250 mg/m2 of rituximab and 0.4 mCi/kg of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan.

Patient characteristics

In the RIT group, 10 patients had CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), 6 had follicular lymphoma (FL), 1 had marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), and 1 had hairy cell leukemia. As for controls, 52 had CLL/SLL, 18 had FL, and 1 had MZL.

“The majority of patients were male [74%] and a relatively young age, given the diseases being treated [median of 56 years],” Dr Cassaday said. “The majority of patients had previously received rituximab [88%], and patients were heavily pretreated [median of 4 prior therapies, range 1-12].”

There were no significant differences between the 2 treatment groups with regard to the aforementioned characteristics. However, there were some “striking differences” between the 2 groups, Dr Cassaday said, including characteristics that portend worse prognosis.

Specifically, RIT-treated patients had more bulky disease (> 5 cm) than controls (61% vs 15%, P<0.001) and more chemoresistant disease (81% vs 39%, P=0.003). And RIT patients were more likely to have HCT comorbidity index scores of 3 or higher (72% vs 37%, P=0.006), as well as pre-NMAT platelet counts less than 25k/μL (33% vs 7%, P=0.002).

RIT improves PFS, OS

The researchers conducted a multivariate analysis including the factors that differed significantly between the 2 treatment groups. And they found that only RIT was significantly associated with both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

When calculating survival curves, the researchers adjusted for the imbalance in covariates between the treatment groups.

“[The adjusted survival rate] is essentially what one might expect had the RIT group had similar baseline characteristics as the control group,” Dr Cassaday explained.

Control subjects had a 3-year OS of 55%. For the RIT-treated patients, the unadjusted 3-year OS was 78% (P=0.20), and the adjusted OS was 87% (P=0.008).

The 3-year PFS was 44% for controls. For the RIT group, the unadjusted 3-year PFS was 56% (P=0.36), and the adjusted PFS was 71% (P=0.02).

The researchers also found that RIT did not increase the rate of non-relapse mortality. The unadjusted hazard ratio was 0.5 (P=0.32), and the adjusted hazard ratio was 0.4 (P=0.18).

“This analysis does have some limitations,” Dr Cassaday conceded. “Clearly, it does not replace the strength of evidence that would come from a randomized, controlled trial. And the relatively small sample size does limit our ability to look at a lot of different subgroups.”

In addition, the findings may not apply to other non-myeloablative regimens. And, due to the time frame of the study, the researchers could not account for the potential impact of newer agents.

Nevertheless, Dr Cassaday said the data suggest that RIT can improve the outcome of NMAT in patients with persistent indolent B-NHL or CLL. And a prospective, randomized study evaluating this approach is warranted.

Dr Cassaday presented this research at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings as abstract 75. Information in the abstract differs from that presented. ![]()

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS—Administering radioimmunotherapy (RIT) prior to non-myeloablative allogeneic transplant (NMAT) can improve survival in patients with persistent disease, according to a speaker at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings.

Ryan Cassaday, MD, of the University of Washington in Seattle, noted that RIT-augmented NMAT can produce long-term remissions in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

But outcomes for patients with persistent disease are “underdescribed.”

So he and his colleagues set out to describe outcomes of NMAT for patients with persistent indolent B-NHL or CLL and estimate the impact of RIT in these patients.

Treatment details

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data from 89 patients who underwent NMAT from December 1998 to April 2009 and were followed until September 2013. Eighteen of the patients had received RIT as part of a prospective study (AK Gopal et al, Blood 2011).

The remaining 71 patients did not receive RIT but met eligibility criteria for that study. Specifically, they had a CD20+ B-cell malignancy, an HLA-matched peripheral blood stem cell donor, and persistent disease at NMAT. These control subjects received fludarabine (30 mg/m2 on days -7, -6, and -5) and 2 Gy of total body irradiation prior to NMAT.

Patients in the RIT group received the same treatment following RIT. On day -21, they received 250 mg/m2 of rituximab before an imaging dose of 111In-ibritumomab tiuxetan. And on day -14, they received 250 mg/m2 of rituximab and 0.4 mCi/kg of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan.

Patient characteristics

In the RIT group, 10 patients had CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), 6 had follicular lymphoma (FL), 1 had marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), and 1 had hairy cell leukemia. As for controls, 52 had CLL/SLL, 18 had FL, and 1 had MZL.

“The majority of patients were male [74%] and a relatively young age, given the diseases being treated [median of 56 years],” Dr Cassaday said. “The majority of patients had previously received rituximab [88%], and patients were heavily pretreated [median of 4 prior therapies, range 1-12].”

There were no significant differences between the 2 treatment groups with regard to the aforementioned characteristics. However, there were some “striking differences” between the 2 groups, Dr Cassaday said, including characteristics that portend worse prognosis.

Specifically, RIT-treated patients had more bulky disease (> 5 cm) than controls (61% vs 15%, P<0.001) and more chemoresistant disease (81% vs 39%, P=0.003). And RIT patients were more likely to have HCT comorbidity index scores of 3 or higher (72% vs 37%, P=0.006), as well as pre-NMAT platelet counts less than 25k/μL (33% vs 7%, P=0.002).

RIT improves PFS, OS

The researchers conducted a multivariate analysis including the factors that differed significantly between the 2 treatment groups. And they found that only RIT was significantly associated with both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

When calculating survival curves, the researchers adjusted for the imbalance in covariates between the treatment groups.

“[The adjusted survival rate] is essentially what one might expect had the RIT group had similar baseline characteristics as the control group,” Dr Cassaday explained.

Control subjects had a 3-year OS of 55%. For the RIT-treated patients, the unadjusted 3-year OS was 78% (P=0.20), and the adjusted OS was 87% (P=0.008).

The 3-year PFS was 44% for controls. For the RIT group, the unadjusted 3-year PFS was 56% (P=0.36), and the adjusted PFS was 71% (P=0.02).

The researchers also found that RIT did not increase the rate of non-relapse mortality. The unadjusted hazard ratio was 0.5 (P=0.32), and the adjusted hazard ratio was 0.4 (P=0.18).

“This analysis does have some limitations,” Dr Cassaday conceded. “Clearly, it does not replace the strength of evidence that would come from a randomized, controlled trial. And the relatively small sample size does limit our ability to look at a lot of different subgroups.”

In addition, the findings may not apply to other non-myeloablative regimens. And, due to the time frame of the study, the researchers could not account for the potential impact of newer agents.

Nevertheless, Dr Cassaday said the data suggest that RIT can improve the outcome of NMAT in patients with persistent indolent B-NHL or CLL. And a prospective, randomized study evaluating this approach is warranted.

Dr Cassaday presented this research at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings as abstract 75. Information in the abstract differs from that presented. ![]()

GRAPEVINE, TEXAS—Administering radioimmunotherapy (RIT) prior to non-myeloablative allogeneic transplant (NMAT) can improve survival in patients with persistent disease, according to a speaker at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings.

Ryan Cassaday, MD, of the University of Washington in Seattle, noted that RIT-augmented NMAT can produce long-term remissions in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

But outcomes for patients with persistent disease are “underdescribed.”

So he and his colleagues set out to describe outcomes of NMAT for patients with persistent indolent B-NHL or CLL and estimate the impact of RIT in these patients.

Treatment details

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data from 89 patients who underwent NMAT from December 1998 to April 2009 and were followed until September 2013. Eighteen of the patients had received RIT as part of a prospective study (AK Gopal et al, Blood 2011).

The remaining 71 patients did not receive RIT but met eligibility criteria for that study. Specifically, they had a CD20+ B-cell malignancy, an HLA-matched peripheral blood stem cell donor, and persistent disease at NMAT. These control subjects received fludarabine (30 mg/m2 on days -7, -6, and -5) and 2 Gy of total body irradiation prior to NMAT.

Patients in the RIT group received the same treatment following RIT. On day -21, they received 250 mg/m2 of rituximab before an imaging dose of 111In-ibritumomab tiuxetan. And on day -14, they received 250 mg/m2 of rituximab and 0.4 mCi/kg of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan.

Patient characteristics

In the RIT group, 10 patients had CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), 6 had follicular lymphoma (FL), 1 had marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), and 1 had hairy cell leukemia. As for controls, 52 had CLL/SLL, 18 had FL, and 1 had MZL.

“The majority of patients were male [74%] and a relatively young age, given the diseases being treated [median of 56 years],” Dr Cassaday said. “The majority of patients had previously received rituximab [88%], and patients were heavily pretreated [median of 4 prior therapies, range 1-12].”

There were no significant differences between the 2 treatment groups with regard to the aforementioned characteristics. However, there were some “striking differences” between the 2 groups, Dr Cassaday said, including characteristics that portend worse prognosis.

Specifically, RIT-treated patients had more bulky disease (> 5 cm) than controls (61% vs 15%, P<0.001) and more chemoresistant disease (81% vs 39%, P=0.003). And RIT patients were more likely to have HCT comorbidity index scores of 3 or higher (72% vs 37%, P=0.006), as well as pre-NMAT platelet counts less than 25k/μL (33% vs 7%, P=0.002).

RIT improves PFS, OS

The researchers conducted a multivariate analysis including the factors that differed significantly between the 2 treatment groups. And they found that only RIT was significantly associated with both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

When calculating survival curves, the researchers adjusted for the imbalance in covariates between the treatment groups.

“[The adjusted survival rate] is essentially what one might expect had the RIT group had similar baseline characteristics as the control group,” Dr Cassaday explained.

Control subjects had a 3-year OS of 55%. For the RIT-treated patients, the unadjusted 3-year OS was 78% (P=0.20), and the adjusted OS was 87% (P=0.008).

The 3-year PFS was 44% for controls. For the RIT group, the unadjusted 3-year PFS was 56% (P=0.36), and the adjusted PFS was 71% (P=0.02).

The researchers also found that RIT did not increase the rate of non-relapse mortality. The unadjusted hazard ratio was 0.5 (P=0.32), and the adjusted hazard ratio was 0.4 (P=0.18).

“This analysis does have some limitations,” Dr Cassaday conceded. “Clearly, it does not replace the strength of evidence that would come from a randomized, controlled trial. And the relatively small sample size does limit our ability to look at a lot of different subgroups.”

In addition, the findings may not apply to other non-myeloablative regimens. And, due to the time frame of the study, the researchers could not account for the potential impact of newer agents.

Nevertheless, Dr Cassaday said the data suggest that RIT can improve the outcome of NMAT in patients with persistent indolent B-NHL or CLL. And a prospective, randomized study evaluating this approach is warranted.

Dr Cassaday presented this research at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings as abstract 75. Information in the abstract differs from that presented. ![]()

The demise of renal artery stenting

The announcement from Medtronic in January has apparently brought down the curtain on the much-heralded approach to the treatment of refractory hypertension using radio-frequency renal artery sympathetic nerve ablation (RASNA) applied through the tip of the Symplicity catheter.

This technology is being used widely around the world for the treatment of refractory hypertensive patients. The enthusiasm for RASNA was generated by a series of reports suggesting that an amazing decrease in systolic blood pressure of more than 30 mm Hg can be obtained in patients with resistant hypertension taking three or more antihypertensive drugs. However, the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial (Clin. Cardiol. 2012;35:528-35), which enrolled 535 patients with refractory hypertension, failed to achieve the primary endpoint of a significant decrease in systolic pressure in the radio-frequency (RF)-treated patients compared with the sham-operated patients. In the study, blinding was rigorously managed by renal artery catheterization of all 535 patients, with RF ablation instituted in two-thirds of the patients, and a sham operation conducted in one-third.

As a result of the observations in SYMPLICITY HTN-3, Medtronic is suspending enrollment in current trials using the Symplicity device throughout the world, and will "continue to ensure patients access to the Symplicity technology at the discretion of their physicians in countries where the device is approved," according to its statement.

Enthusiasm for RF ablation of the sympathetic nerves accompanying the renal artery was generated by a series of publications describing the physiologic and therapeutic effects. The first publications in this series described the metabolic changes that occurred after RF ablation carried out in one patient who experienced a decrease in systolic pressure of 20 mm Hg associated with modulation of sympathetic activity 30 days and 12 months after the procedure (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:932-4). This study was followed by two subsequent reports of patients in whom RASNA was carried out. A proof-of-concept trial (SYMPLICITY HTN-1) in 153 patients reported a substantial decrease in blood pressure over a 2-year period (Hypertension 2011;57:911-7). A second trial (SYMPLICITY HTN-2) randomized 106 patients to either RASNA or standard therapy. That trial reported that 84% of the patients receiving RASNA had a reduction of blood pressure greater than 10 mm Hg within 6 months, compared with 35% of the control group (Lancet 2010;376:1903-9). Both studies reported a profound decrease in blood pressure that ensued over a 6-month period in 80%-90% of patients undergoing the therapy. In light of these reports, it is difficult to explain the fact that SYMPLICITY HTN-3 was a negative study.

Modulation of the sympathetic nervous system for the treatment of hypertension is not new. More than 60 years ago, Smithwick and colleagues carried out both surgical lumbar and sympathetic splanchnicectomy for its treatment with uncertain results (JAMA 1952;153:1501-4). In an era when all that we could offer hypertensive patients was a low-salt diet, the procedure became rather popular. However, the surgical risks, adverse side effects, and uncertainty of benefit led to both procedures being discontinued. Recently, there have been studies of the effect of stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve for the treatment of hypertension.

The potential benefit of modulation of the arterial sympathetic nerves, and particularly those located in the renal artery, became the focus of this recent interest. Nevertheless, a number of questions have arisen in regard to the mechanism of RASNA. And why does it take 6 months to achieve the blood pressure response? In addition, there is very little published data in regard to the changes in the renal artery and its adjacent tissue as a result of the RF ablation.

At the present, Medtronic has not provided any information beyond its indicating the lack of benefit. Further information will be reported at the upcoming American College of Cardiology scientific sessions. In the meantime, speculation is rampant as to whether the initial reports were purely placebo effects or if there is something intrinsically flawed in the SYMPLICITY HTN -3 trial.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

The announcement from Medtronic in January has apparently brought down the curtain on the much-heralded approach to the treatment of refractory hypertension using radio-frequency renal artery sympathetic nerve ablation (RASNA) applied through the tip of the Symplicity catheter.

This technology is being used widely around the world for the treatment of refractory hypertensive patients. The enthusiasm for RASNA was generated by a series of reports suggesting that an amazing decrease in systolic blood pressure of more than 30 mm Hg can be obtained in patients with resistant hypertension taking three or more antihypertensive drugs. However, the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial (Clin. Cardiol. 2012;35:528-35), which enrolled 535 patients with refractory hypertension, failed to achieve the primary endpoint of a significant decrease in systolic pressure in the radio-frequency (RF)-treated patients compared with the sham-operated patients. In the study, blinding was rigorously managed by renal artery catheterization of all 535 patients, with RF ablation instituted in two-thirds of the patients, and a sham operation conducted in one-third.

As a result of the observations in SYMPLICITY HTN-3, Medtronic is suspending enrollment in current trials using the Symplicity device throughout the world, and will "continue to ensure patients access to the Symplicity technology at the discretion of their physicians in countries where the device is approved," according to its statement.

Enthusiasm for RF ablation of the sympathetic nerves accompanying the renal artery was generated by a series of publications describing the physiologic and therapeutic effects. The first publications in this series described the metabolic changes that occurred after RF ablation carried out in one patient who experienced a decrease in systolic pressure of 20 mm Hg associated with modulation of sympathetic activity 30 days and 12 months after the procedure (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:932-4). This study was followed by two subsequent reports of patients in whom RASNA was carried out. A proof-of-concept trial (SYMPLICITY HTN-1) in 153 patients reported a substantial decrease in blood pressure over a 2-year period (Hypertension 2011;57:911-7). A second trial (SYMPLICITY HTN-2) randomized 106 patients to either RASNA or standard therapy. That trial reported that 84% of the patients receiving RASNA had a reduction of blood pressure greater than 10 mm Hg within 6 months, compared with 35% of the control group (Lancet 2010;376:1903-9). Both studies reported a profound decrease in blood pressure that ensued over a 6-month period in 80%-90% of patients undergoing the therapy. In light of these reports, it is difficult to explain the fact that SYMPLICITY HTN-3 was a negative study.

Modulation of the sympathetic nervous system for the treatment of hypertension is not new. More than 60 years ago, Smithwick and colleagues carried out both surgical lumbar and sympathetic splanchnicectomy for its treatment with uncertain results (JAMA 1952;153:1501-4). In an era when all that we could offer hypertensive patients was a low-salt diet, the procedure became rather popular. However, the surgical risks, adverse side effects, and uncertainty of benefit led to both procedures being discontinued. Recently, there have been studies of the effect of stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve for the treatment of hypertension.

The potential benefit of modulation of the arterial sympathetic nerves, and particularly those located in the renal artery, became the focus of this recent interest. Nevertheless, a number of questions have arisen in regard to the mechanism of RASNA. And why does it take 6 months to achieve the blood pressure response? In addition, there is very little published data in regard to the changes in the renal artery and its adjacent tissue as a result of the RF ablation.

At the present, Medtronic has not provided any information beyond its indicating the lack of benefit. Further information will be reported at the upcoming American College of Cardiology scientific sessions. In the meantime, speculation is rampant as to whether the initial reports were purely placebo effects or if there is something intrinsically flawed in the SYMPLICITY HTN -3 trial.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

The announcement from Medtronic in January has apparently brought down the curtain on the much-heralded approach to the treatment of refractory hypertension using radio-frequency renal artery sympathetic nerve ablation (RASNA) applied through the tip of the Symplicity catheter.

This technology is being used widely around the world for the treatment of refractory hypertensive patients. The enthusiasm for RASNA was generated by a series of reports suggesting that an amazing decrease in systolic blood pressure of more than 30 mm Hg can be obtained in patients with resistant hypertension taking three or more antihypertensive drugs. However, the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial (Clin. Cardiol. 2012;35:528-35), which enrolled 535 patients with refractory hypertension, failed to achieve the primary endpoint of a significant decrease in systolic pressure in the radio-frequency (RF)-treated patients compared with the sham-operated patients. In the study, blinding was rigorously managed by renal artery catheterization of all 535 patients, with RF ablation instituted in two-thirds of the patients, and a sham operation conducted in one-third.

As a result of the observations in SYMPLICITY HTN-3, Medtronic is suspending enrollment in current trials using the Symplicity device throughout the world, and will "continue to ensure patients access to the Symplicity technology at the discretion of their physicians in countries where the device is approved," according to its statement.

Enthusiasm for RF ablation of the sympathetic nerves accompanying the renal artery was generated by a series of publications describing the physiologic and therapeutic effects. The first publications in this series described the metabolic changes that occurred after RF ablation carried out in one patient who experienced a decrease in systolic pressure of 20 mm Hg associated with modulation of sympathetic activity 30 days and 12 months after the procedure (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:932-4). This study was followed by two subsequent reports of patients in whom RASNA was carried out. A proof-of-concept trial (SYMPLICITY HTN-1) in 153 patients reported a substantial decrease in blood pressure over a 2-year period (Hypertension 2011;57:911-7). A second trial (SYMPLICITY HTN-2) randomized 106 patients to either RASNA or standard therapy. That trial reported that 84% of the patients receiving RASNA had a reduction of blood pressure greater than 10 mm Hg within 6 months, compared with 35% of the control group (Lancet 2010;376:1903-9). Both studies reported a profound decrease in blood pressure that ensued over a 6-month period in 80%-90% of patients undergoing the therapy. In light of these reports, it is difficult to explain the fact that SYMPLICITY HTN-3 was a negative study.

Modulation of the sympathetic nervous system for the treatment of hypertension is not new. More than 60 years ago, Smithwick and colleagues carried out both surgical lumbar and sympathetic splanchnicectomy for its treatment with uncertain results (JAMA 1952;153:1501-4). In an era when all that we could offer hypertensive patients was a low-salt diet, the procedure became rather popular. However, the surgical risks, adverse side effects, and uncertainty of benefit led to both procedures being discontinued. Recently, there have been studies of the effect of stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve for the treatment of hypertension.

The potential benefit of modulation of the arterial sympathetic nerves, and particularly those located in the renal artery, became the focus of this recent interest. Nevertheless, a number of questions have arisen in regard to the mechanism of RASNA. And why does it take 6 months to achieve the blood pressure response? In addition, there is very little published data in regard to the changes in the renal artery and its adjacent tissue as a result of the RF ablation.

At the present, Medtronic has not provided any information beyond its indicating the lack of benefit. Further information will be reported at the upcoming American College of Cardiology scientific sessions. In the meantime, speculation is rampant as to whether the initial reports were purely placebo effects or if there is something intrinsically flawed in the SYMPLICITY HTN -3 trial.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Hyperglycemia and CV Complications

Hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients is frequently observed and is recognized as an important threat to the health of patients with varying levels of illness, independent of diabetes status.[1, 2, 3, 4] Previous studies have found that in‐hospital hyperglycemia is associated with higher short‐term mortality rates,[5, 6, 7] longer lengths of stay, and higher rates of admission to intensive care units.[4]

In‐hospital hyperglycemia may be the result of diabetes mellitus or stress associated with hospitalization. The mechanism of stress hyperglycemia differs from diabetic hyperglycemia and can occur independently of diabetes status.[8] Stress hyperglycemia is characterized by rapid onset of insulin resistance, which normally takes months or years in diabetes mellitus. It develops in association with or because of other stressor such as infection or inflammatory processes.[9]

To our knowledge, no long‐term follow‐up study on hospitalized patients with elevated glucose levels but without a diabetes diagnosis has ever been conducted. In this study, we measured the 1‐ and 5‐year risk of mortality and diabetes‐related diseases for hospitalized patients with a diabetes diagnosis compared with patients grouped according to their peak in‐hospital serum glucose level. Our primary comparison was between patients with diagnosed diabetes and those with peak serum glucose >200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), but we also examined 4 other categories of peak serum glucose: 140 to 200 mg/dL (7.811.1 mmol/L), 108 to 140 mg/dL (6.07.8 mmol/L), and <108 mg/dL (<6.0 mmol/L).

METHODS

Study Base

The study included all adult patients (excluding patients admitted to psychiatry and obstetrics) admitted to The Ottawa Hospital (TOH) between January 1, 1996 and March 31, 2008 and discharged alive. Included patients were 18 years or older and had complete medical record abstracts. TOH is the primary hospital in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, and the main tertiary hospital in the Champlain Local Health Integration Network, the public healthcare authority for the Ottawa region. This study was approved by The Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Data Sources

The Ottawa Hospital Data Warehouse (OHDW) is a repository for data from the hospital's patient information systems. These systems include patient registration information, discharge abstract, and laboratory, pharmacy, and radiology results. OHDW was used to determine each patient's age, gender, diagnoses, pharmacy orders, laboratory test results, in‐hospital comorbidities, most responsible hospital service, and admission urgency.

This dataset was linked to 3 population‐based administrative datasets and 1 derived cohort. Ontario's Registered Persons Database (RPDB) is a population‐based registry containing date of death (if applicable) as well as eligibility status for the provincial universal health insurance program, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP).[10] The OHIP database records billing claims submitted by approximately 95% of Ontario physicians. Each claim contains a fee code describing the type of service provided and a location denoting where the service had taken place. The Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) records clinical, demographic, and administrative data for all hospital admissions and same‐day surgeries for all Ontario acute care hospitals since April 1, 1988. The Ontario Myocardial Infarction Database (OMID) contains records of all patients with a most responsible diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] code 410 or International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD‐10] code I21) identified from the DAD. Details on the creation of the OMID are provided in an earlier study.[10]

Variable Definitions

We identified the index admission of the TOH cohort in the DAD using a unique encrypted health insurance number, admission and discharge dates, and the institution number. To avoid double counting, patients with the same encrypted health insurance number who were discharged from an institution and admitted to another within 2 days were classified as transfers and counted as 1 hospitalization.

Diabetes and cardiovascular (CV) complications (acute myocardial infarction [AMI], congestive heart failure [CHF], cardiovascular disease [CVD], peripheral vascular disease [PVD], and end‐stage renal disease [ESRD]) were identified in the discharge abstract as the most responsible diagnosis for the admission as well as postadmission comorbidities. The discharge abstract records diagnostic codes according to ICD‐9 (April 1, 1988March 31, 2002) or ICD‐10 (April 1, 2002March 1, 2009).

Each hospitalization was classified into 1 of 6 mutually exclusive diabetes status categories based on diagnostic codes, serum glucose test results, and pharmacy records. The diagnosed diabetes group included hospitalizations with any diagnostic code of diabetes in the discharge abstract or any order for a diabetes medication during hospitalization. Eligible medications included acarbose, acetohexamide, chlorpropamide, glibenclamide, gliclazide, glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide, insulin, metformin, nateglinide, pioglitazone, repaglinide, rosiglitazone, and tolbutamide. A chart validation study showed excellent ascertainment of diabetes status using these methods (correct classification 88.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 85.791.3 with weighted kappa=0.89; 95% CI: 0.85‐0.92).[11, 12] Patients without diagnosed diabetes were classified according to their peak serum glucose value during the index hospitalization: <108 mg/dL (<6.0 mmol/L), 108 to 140 mg/dL (6.07.8 mmol/L), 140 to 200 mg/dL (7.811.1 mmol/L), >200 mg/dL (>11.1 mmol/L); hospitalizations in which glucose levels were not obtained were classified as unknown. These peak serum glucose categories are based on the World Health Organization's definition of diabetes and poor glucose tolerance.[12]

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all‐cause postdischarge mortality determined by linking the index admission to the RPDB. Secondary outcomes were CV complications, including: AMI (determined by linking to the OMID); hospitalization for CHF (determined by linking to the DAD for primary diagnosis of 425, 428, 514, 518.4 or I50, I42.0, I42.6, I42.7, I42.8, I42.9, I43, J81), CVD (determined by linking to the DAD for primary diagnosis of 430, 431, 432, 434, 436 or I60, I61, I62, I63, I64, G46), PVD (determined by primary diagnosis of 96.11, 96.12, 96.13, 96.14, 96.15 [excluded if in conjunction with 170, 171, 213, 730, 740759, 800900, 901904, 940950], 50.18, 51.25, 51.29 [excluded if in conjunction with 414.1, 441, 44] or 1VC93, 1VG93, 1VQ93, 1WA93, 1WE93, 1WJ93, 1WL93, 1WM93 [excluded if in conjunction with C40, C41, C46.1, C47, C49, D160, M46.2, M86, M87, M89.6, M90.0‐M90.5, Q00, Q38‐Q40, S02.0, S09.0, S04.0, S15, S25, T26), and 1KG50, 1KG57, 1KG76, 1KG35HAC1, 1KG35HHC1 [excluded if in conjunction with I60, I67.1, I71, I72, 177.0, 179.0]), and ESRD (determined by 403.9, 404.9,584, 585, 586, 788.5 or I12, I13, N17, N18, N19, R34).

Analysis

We identified all encounters of cohort patients in any Ontario acute‐care hospital within 5 years following the index discharge. Patients not covered by provincial health insurance (OHIP) were excluded.

We first measured crude mortality and morbidity rates by patient category (diagnosed diabetes and glucose levels). Next, we compared the unadjusted outcomes and baseline characteristics (age, sex, previous inpatient and emergency admissions, and disease at admission) between groups using a [2] test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

Due to the violation of proportional hazards, we used the Weibull accelerated failure time model to calculate the hazard of death associated with diabetes status or serum glucose level. Consistency of the probability plots confirmed appropriateness of using the Weibull function. Competing risk is defined as a type of failure that prevents the observation of the event of interest or fundamentally alters the probability of its occurrence.[13, 14] In the comorbidity analyses, death is a competing risk for all other outcomes. We calculated the multivariate competing risk hazard for each outcome of interest except death. Each model was adjusted for potential confounders: baseline risk of in‐hospital mortality, common comorbidities, most responsible hospital service, and the number of previous inpatient admissions and emergency department visits to TOH in the previous 6 months. The probability of dying during the admission was calculated using the Escobar model, which predicts the in‐hospital probability of dying using data available at the time of admission to the hospital.[15] The Escobar model has been validated in the study population.[16] The baseline probability of dying was based on age, sex, acuity of admission, primary condition, Charlson comorbidity score,[17] and the laboratory‐based acute physiology score.[15] The Charlson comorbidity score was calculated using weights from Schneeweiss et al.[17] Kaplan‐Meier survival curves were created for both adjusted and unadjusted models. Death was used as the main censoring variable when analyzing nonfatal outcomes at 1‐ and 5‐year follow‐up.

Adjusted models were constructed using a stepwise selection technique and compared with Akaike and Bayesian information criteria values. For all tests, significance was defined as a P value of 0.05 or less.

We recognize that the cohort may contain more than 1 index hospitalization per patient. However, repeated analyses using only the first or last encounter per patient produced nearly identical hazard ratios (HRs) and CIs.

RESULTS

Between January 1, 1996 and March 31, 2008, 194,641 nonpsychiatric and nonobstetric adults were admitted to TOH. Seventeen patients were excluded because they were ineligible for healthcare coverage and had no encounter with the Ontario healthcare system following discharge from hospital, and 11,175 of the admissions ended in death. The final cohort consisted of 114,764 unique individuals representing 183,449 encounters.

Patients had a mean age of 59.5 years (standard deviation: 18.0) and 48.9% were male. The baseline risk of dying during hospitalization was 4.8%.

Table 1 describes patients by diabetes and peak serum glucose status. Patients with diagnosed diabetes were more likely to be older and male. Patients with elevated peak serum glucose (>200 mg/dL; >11.1 mmol/L) were younger than the diagnosed diabetes group and had a higher baseline probability of in‐hospital death (9.4%, 95% CI: 9.09.7). Patients in these 2 groups had more inpatient admissions within the previous 6 months compared to the groups with other peak serum glucose values.

| Serum Glucose Level, mg/dL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed Diabetes, n=32,774, 17.9% | >200, n=5,082, 2.8% | 140200, n=25,857, 14.1% | 108140, n=38,741, 21.1% | <108, n=27,603, 15.0% | Unknown, n=53,392, 29.1% | |

| ||||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 65.8 (14.1) | 64.3 (17.0)a | 63.9 (17.3)a | 60.9 (18.6)a | 54.3 (19.7)a | 54.8 (16.9)a |

| Risk‐adjusted mortality at admission, mean (SD) | 0.08 (0.12) | 0.09 (0.12)a | 0.07 (0.10)a | 0.05 (0.09)a | 0.04 (0.07)a | 0.01 (0.04)a |

| Sex, male, no. (%) | 18,200 (55.5) | 2,610 (51.4)a | 13,477 (52.1)a | 19,495 (50.3)a | 12,907 (46.8)a | 22,951 (43.0)a |

| No. of previous inpatient admissions, 6 months (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 22,780 (69.5) | 3,576 (70.4) | 19,118 (73.9)a | 28,827 (74.4)a | 20,354 (73.7)a | 43,317 (81.1)a |

| 1 | 6,470 (19.7) | 962 (18.9) | 4,484 (17.3)a | 6,526 (16.9)a | 4,744 (17.2)a | 7,360 (13.8)a |

| 2+ | 3,524 (10.8) | 544 (10.7) | 2,255 (8.7)a | 3,388 (9.1)a | 2,505 (9.1)a | 2,715 (5.1)a |

| No. of previous emergency admissions (6 months) (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 15,518 (47.4) | 2,638 (51.9)a | 12,681 (49.0)a | 16,584 (42.8)a | 13,039 (47.2) | 43,112 (80.8)a |

| 1 | 9,665 (29.5) | 1,490 (29.3)a | 8,339 (32.3)a | 13,829 (35.7)a | 8,709 (31.6) | 6,533 (12.2)a |

| 2+ | 7,591 (23.2) | 954 (18.8)a | 4,837 (18.7)a | 8,328 (21.5)a | 5,855 (21.2) | 3,747 (7.0)a |

| Emergency admission at index hospitalization (%) | 25,420 (77.6) | 4,178 (82.2)a | 20,284 (78.5)a | 33,282 (85.9)a | 23,598 (85.5)a | 15,039 (28.2)a |

| Length of stay, d (mean/SD) | 12.4 (22.3) | 15.8 (30.0)a | 11.9 (17.1)a | 8.5 (12.2)a | 6.3 (9.5)a | 3.4 (4.9)a |

| Disease at index hospitalization (%) | ||||||

| PVD | 2,783 (8.5) | 257 (5.1)a | 1,387 (5.4)a | 1,372 (3.5)a | 908 (3.3)a | 965 (1.8)a |

| Pneumonia | 3,308 (10.1) | 658 (13.0)a | 2,577 (10.0) | 2,809 (7.3)a | 1,220 (4.4)a | 399 (0.8)a |

| UTI | 3,549 (10.8) | 665 (13.1)a | 2,660 (10.3)a | 3,336 (8.6)a | 1,559 (5.7)a | 929 (1.7)a |

| IHD | 8,957 (27.3) | 1,086 (21.4)a | 4,714 (18.2)a | 5,306 (13.7)a | 3,100 (11.2)a | 2,842 (5.3)a |

| Hypertension | 10,864 (33.2) | 1,115 (21.9)a | 5,155 (19.9)a | 5,880 (15.2)a | 3,045 (11.0)a | 3,211 (6.0)a |

| Arrhythmia | 5,010 (15.3) | 823 (16.2) | 3,768 (14.6)a | 3,718 (9.6)a | 2,046 (7.4)a | 1,172 (2.2)a |

| CHF | 570 (17.5) | 763 (15.0)a | 2,761 (10.7)a | 2,449 (6.3)a | 1,121 (4.1)a | 386 (0.7)a |

| Diagnoses of diabetes in the next year (%) | 126 (2.5) | 368 (1.4) | 370 (1.0) | 215 (0.8) | 540 (1.0) | |

| Diagnoses of diabetes in the next 5 years (%) | 310 (6.1) | 981 (3.8) | 916 (2.4) | 434 (1.7) | 1,317 (2.5) | |

| First 3 most common primary discharge codes | AHD I251 (5.7%), HF I50 (3.1%), NSTEMI I214 (1.6%) | AHD I251 (2.7%), COPD J441 (2.1%), HF I50 (2.0%) | AHD I251 (4.0%), Pneumonia J189 (1.6%), HF I50 (1.5%) | AHD I251 (1.6%), Pneumonia J189 (1.5%), CA D700 (1.3%) | AHD I251 (1.8%), AA K359 (1.7%), UA I200 (1.2%) | OA M171 (2.3%), AHD I251 (2.2%), OA M170 (1.7%) |

Of the 5082 patients classified with a peak serum glucose measurement >200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), 15% had 2 and 8% had more than 2 serum glucose measurements that exceeded this threshold. For the remaining patients (with 1 peak serum glucose measurement >200 mg/dL), 52% had additional serum glucose measurements over 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L).

Table 2 presents crude 1‐ and 5‐year mortality and morbidity rates by patient group. The mortality rate is the percentage of patients who died within 1 year and 5 years of their index admission, with or without developing a CV complication. Morbidity rate describes the percentage who developed the complication among patients who survived after discharge or developed the complication prior to death within a 1‐year and 5‐year period. During the 1‐year follow‐up period, the crude mortality rate among patients with elevated peak serum glucose was higher than all other groups (25.4% vs 20.6% for diagnosed diabetes and 7.4% to 22.5% for other peak serum glucose levels; all P<0.0001). For the 5‐year follow‐up, the gap between patients with elevated peak serum glucose and those with diagnosed diabetes lessened but remained significant (45.1% vs 41.7%; P<0.0001). In the 1‐year follow‐up, patients with diagnosed diabetes had significantly higher morbidity rates than all other groups except for AMI. The difference in the rate of AMI for diagnosed diabetes and patients with elevated glucose was not statistically significant.

| Diagnosed Diabetes, n=32,774 | Serum Glucose Level (mg/dL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >200, n=5,082 | 140200, n=25,857 | 108140, n=38,741 | <108, n=27,603 | Unknown, n=53,392 | ||

| ||||||

| All‐cause death | ||||||

| 1 year | 6,762 (20.6) | 1,293 (25.4)a | 5,309 (20.5) | 7,212 (18.6)a | 4,178 (15)a | 3,969 (7.4)a |

| 5 years | 13,659 (41.7) | 2,292 (45.1)a | 9,871 (38.2)a | 13,256 (34.2)a | 7,606 (27.6)a | 98,614 (16.1)a |

| AMI | ||||||

| 1 year | 728 (2.8) | 104 (2.7) | 326 (1.6)a | 386 (1.2)a | 172 (0.7)a | 218 (0.4)a |

| 5 years | 1,687 (8.4) | 182 (6.3)a | 687 (4.2)a | 837 (3.2)a | 436 (2.2)a | 633 (1.4)a |

| CVD | ||||||

| 1 year | 582 (2.2) | 71 (1.9) | 306 (1.5)a | 403 (1.3)a | 251 (1.1)a | 195 (0.4)a |

| 5 years | 1,153 (5.8) | 143 (5.0) | 623 (3.8)a | 872 (3.4)a | 470 (2.3)a | 534 (1.2)a |

| CHF | ||||||

| 1 year | 2,260 (8.4) | 245 (6.3)a | 870 (4.2)a | 1,023 (3.2)a | 516 (2.2)a | 362 (0.7)a |

| 5 years | 3,830 (17.7) | 395 (12.9)a | 1,529 (9.0)a | 1,802 (6.8)a | 960 (4.7)a | 884 (2.0)a |

| PVD | ||||||

| 1 year | 795 (3.0) | 24 (0.6)a | 114 (0.6)a | 154 (0.5)a | 97 (0.4)a | 141 (0.3)a |

| 5 years | 1,547 (7.8) | 50 (1.8)a | 220 (1.4)a | 275 (1.1)a | 192 (1.0)a | 295 (0.7)a |

| ESRD | ||||||

| 1 year | 953 (3.6) | 104 (2.7)a | 403 (1.9)a | 457 (1.4)a | 311 (1.3)a | 329 (0.7)a |

| 5 years | 1,938 (9.5) | 183 (6.3)a | 807 (4.9)a | 995 (3.8)a | 611 (3.0)a | 771 (1.7)a |

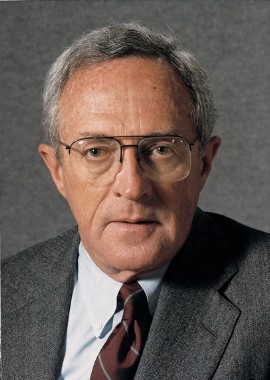

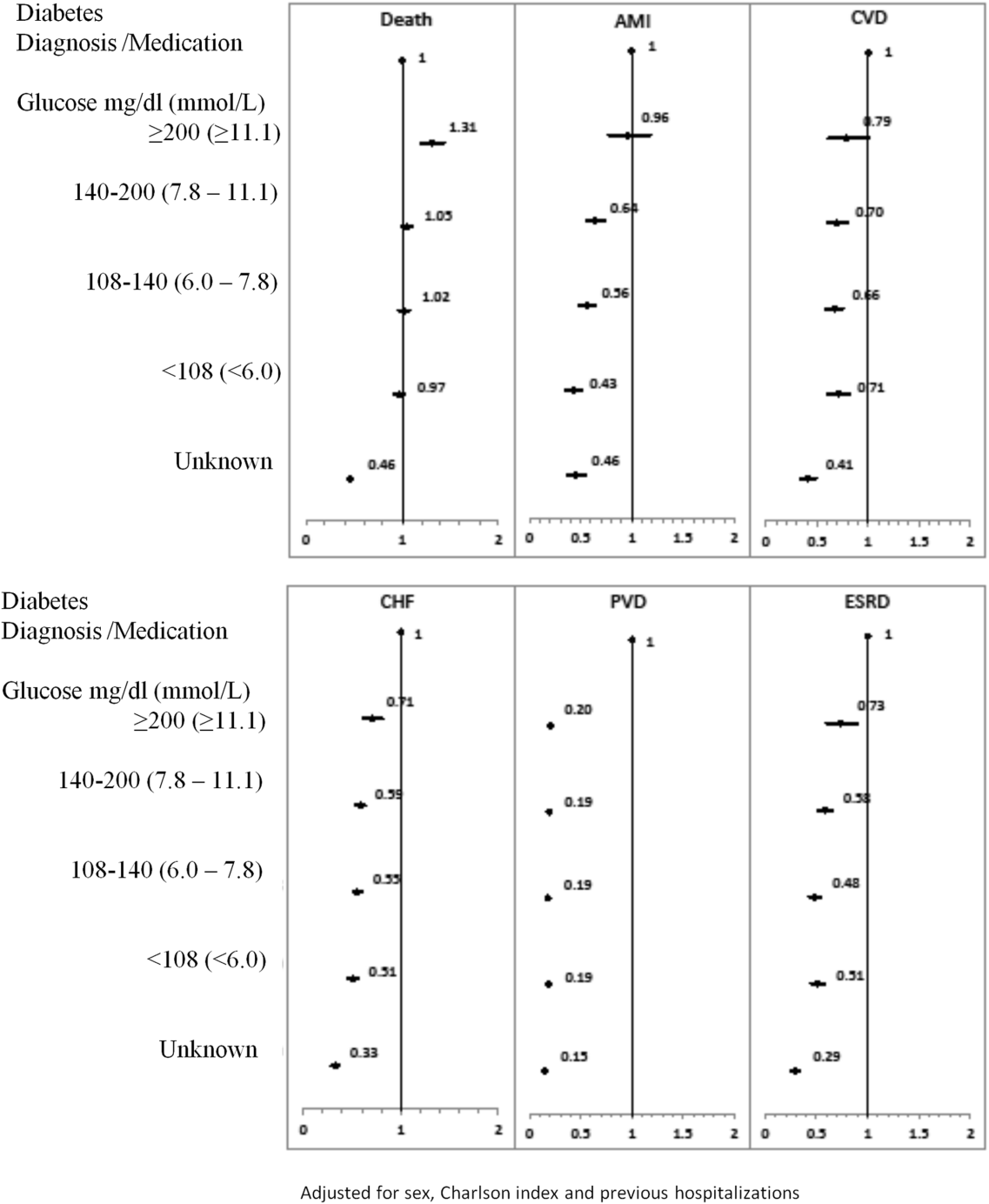

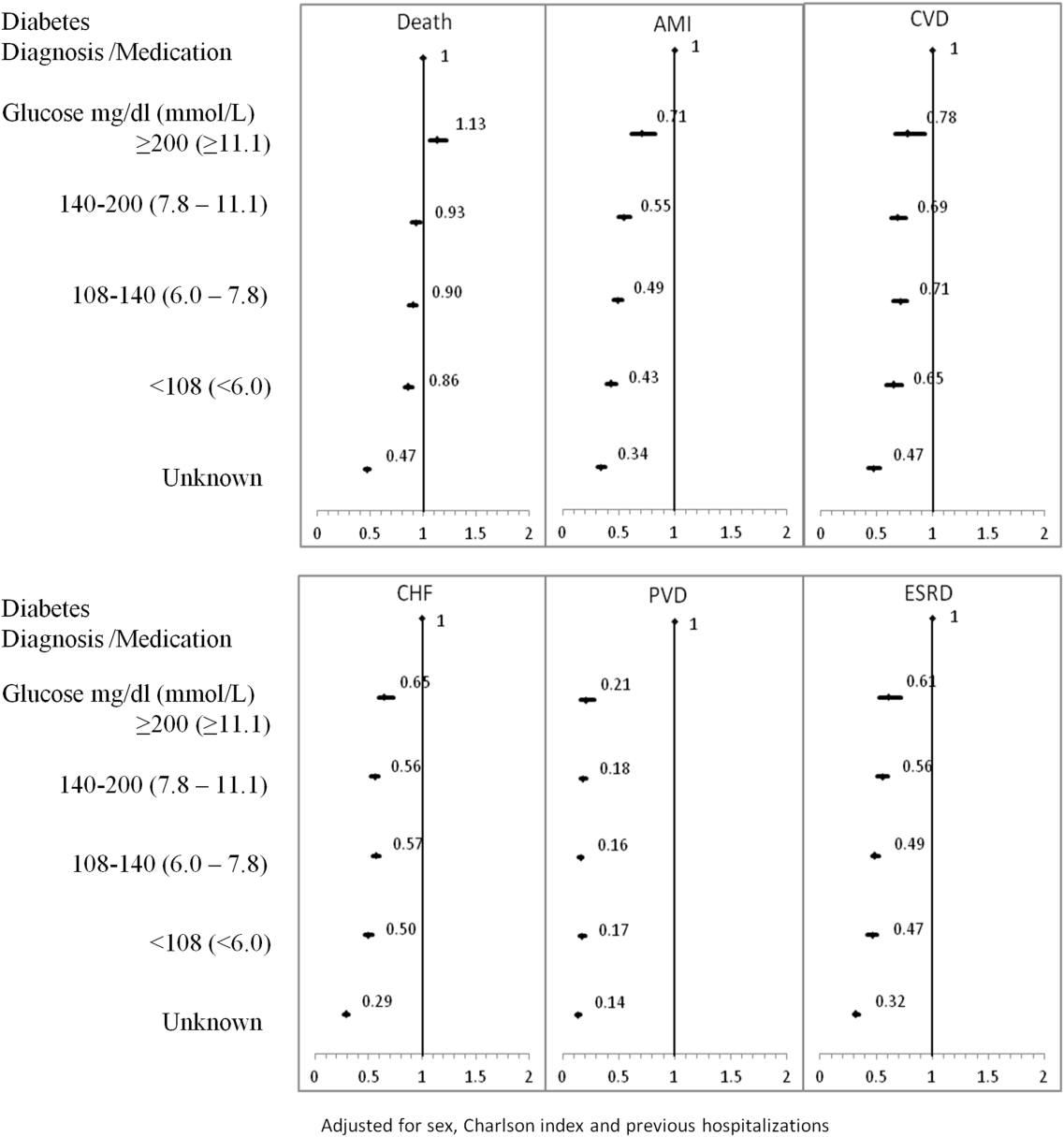

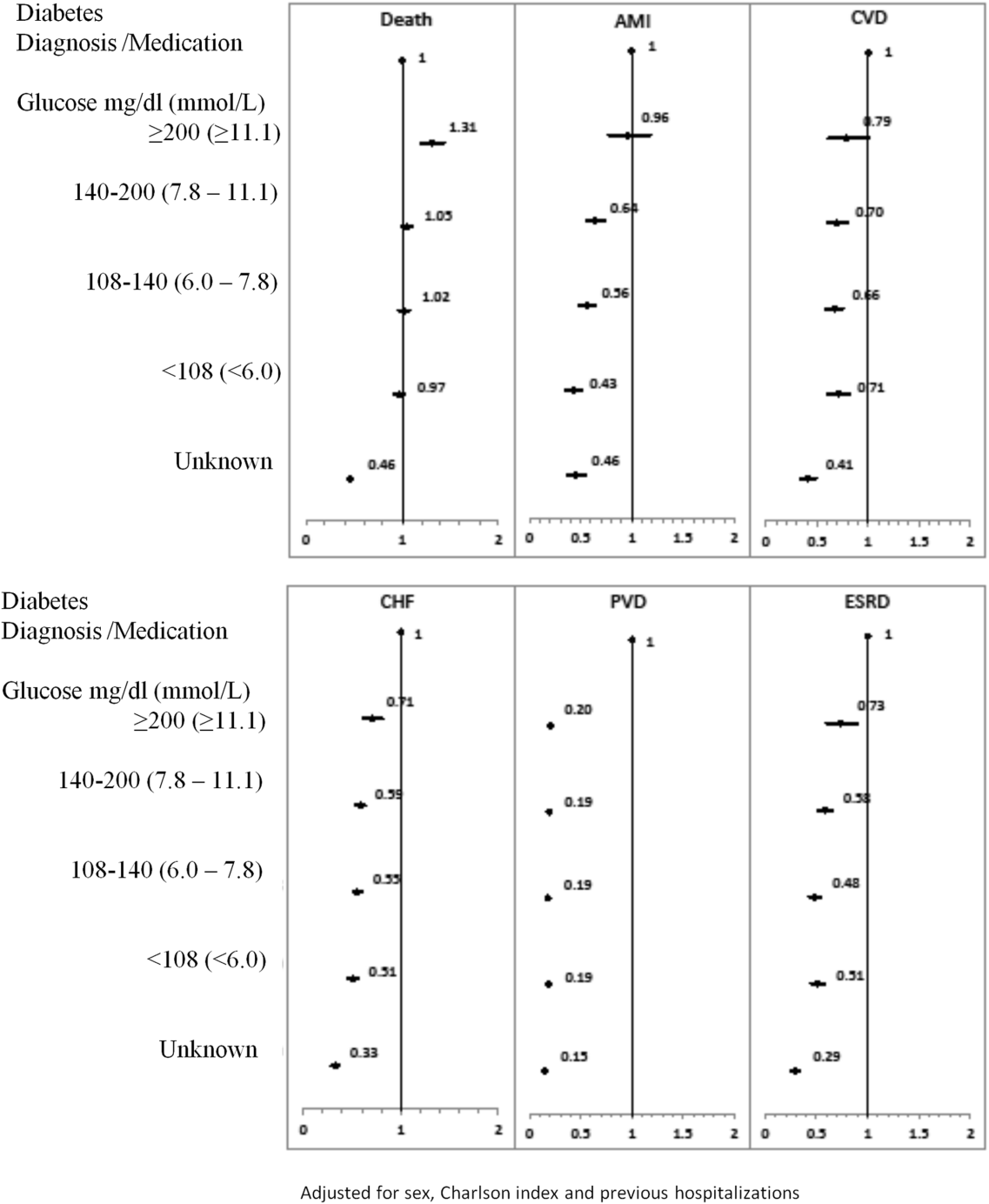

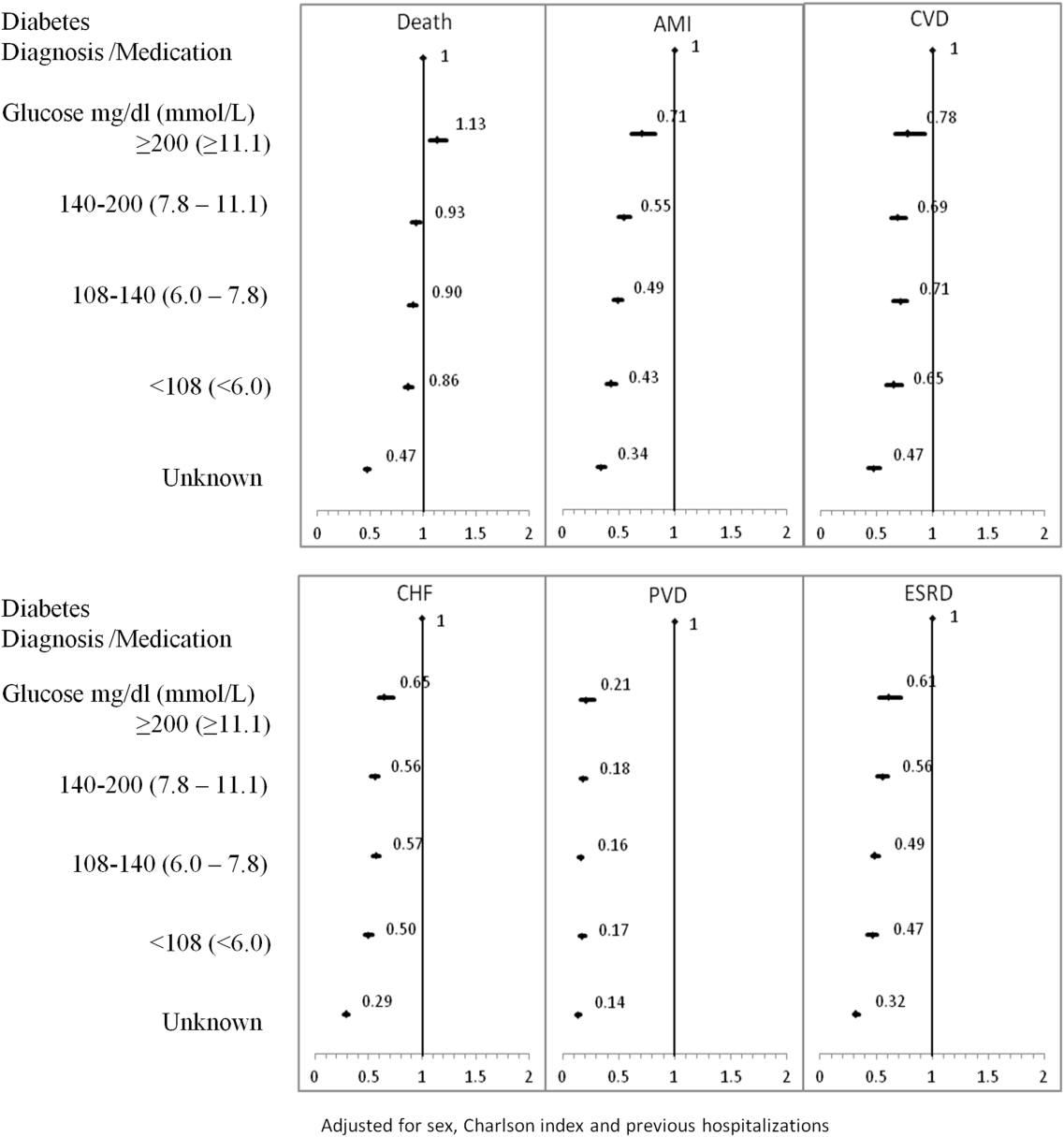

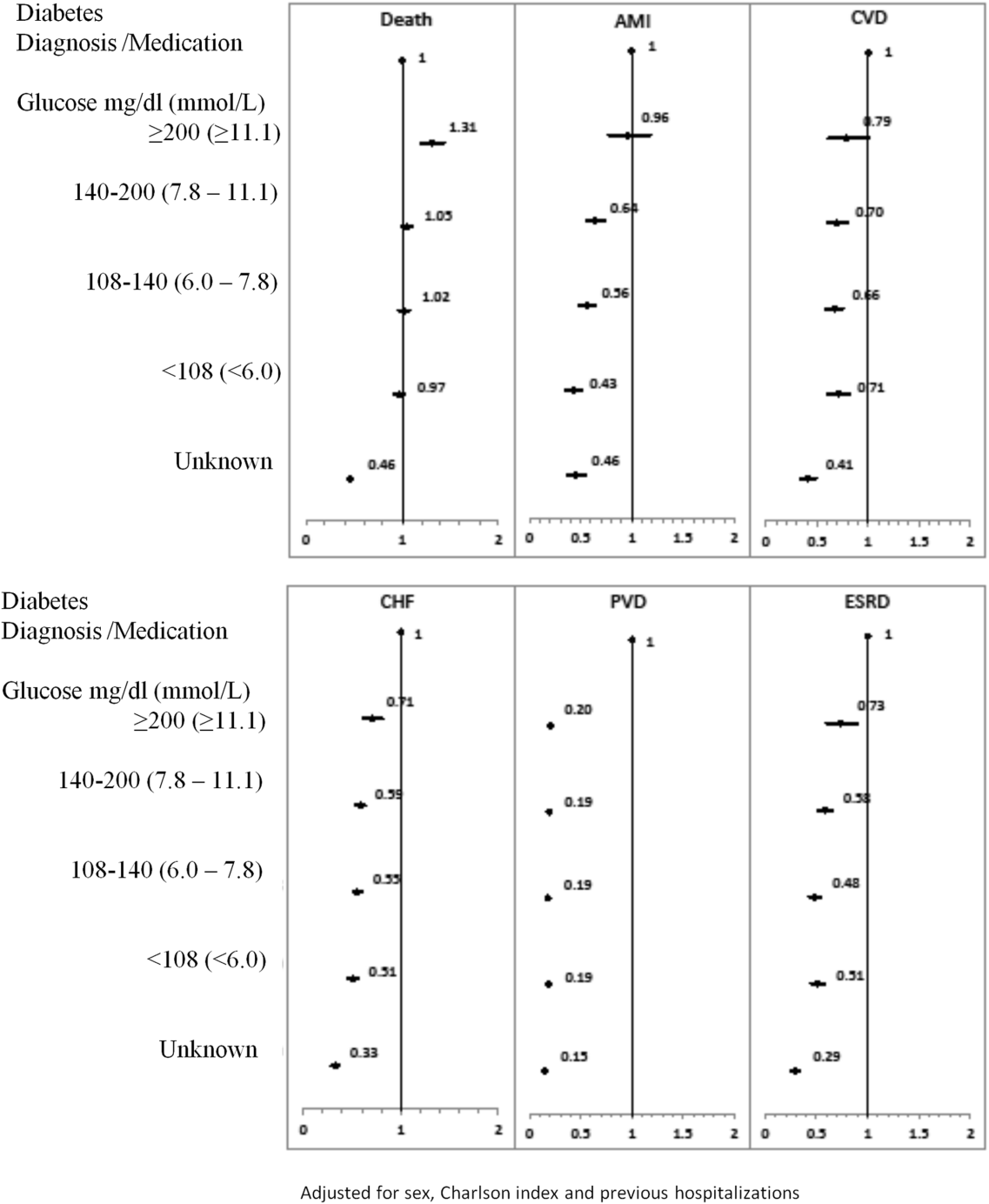

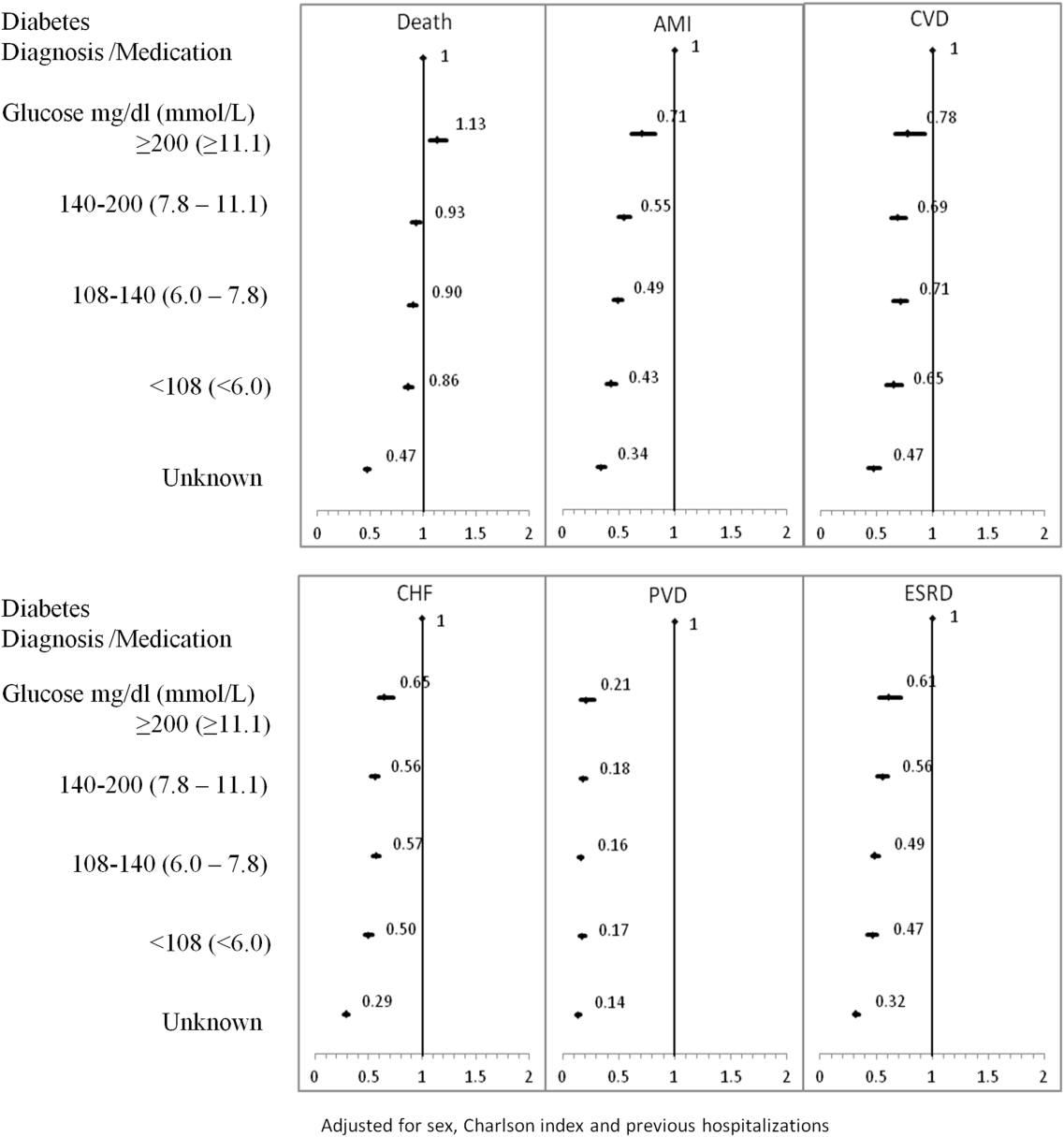

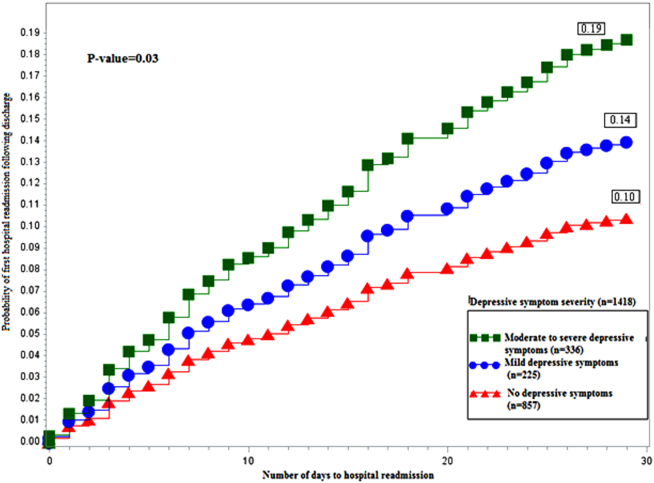

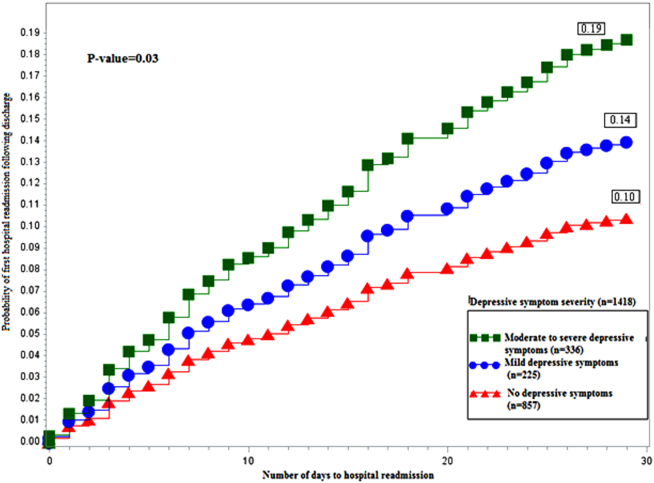

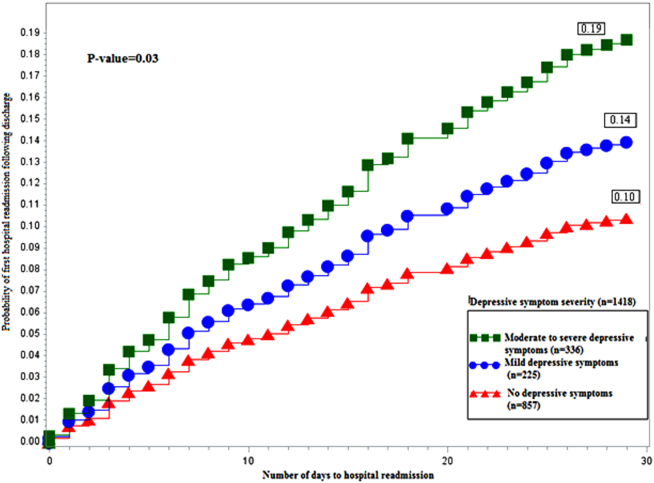

The 1‐year adjusted hazard ratios for mortality and CV complications are presented in Figure 1. After adjustment for baseline demographics and clinical and hospital factors, having a peak serum glucose level above 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) was an independent predictor of death. The mortality risk for this group in the year following discharge was 31% higher than patients with diagnosed diabetes (adjusted HR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.20‐1.43). There was no mortality risk difference between the group with diagnosed diabetes and the lower peak serum glucose levels (adjusted HR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.99‐1.11), 108160 mg/dL (6.07.8 mmol/L) (adjusted HR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.971.07); and <108 mg/dL (<6.0 mmol/L) (adjusted HR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.921.03). Adjusted HRs, with 95% CIs and P values for 5‐year follow‐up are presented in Figure 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios for morbidity showed a different pattern. Patients with diagnosed diabetes had a higher risk of developing complications in the year following discharge from the hospital (Figure 1). After adjusting for potential confounders, we found that patients with diagnosed diabetes had the same risk of AMI and CVD as patients with peak serum glucose levels above 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) (AMI, adjusted HR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.78‐1.18; CVD, adjusted HR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.61‐1.00) but a 36% to 57% higher AMI risk and 29% to 34% higher CVD risk than other peak serum glucose level groups. Compared to all peak serum glucose groups, patients with diagnosed diabetes had a significantly higher risk of developing CHF, PVD, and ESRD (Figure 1). Similarly, the 5‐year risk of AMI, CVD, CHF, PVD, and ESRD was higher for patients with diagnosed diabetes compared to all peak serum glucose groups (Figure 2).

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

The study found that in‐hospital hyperglycemia was a strong predictor of mortality at 1‐ and 5‐years follow‐up, even after adjustment using well‐established and discriminating comorbidity measures. Extreme in‐hospital hyperglycemia was a stronger predictor of mortality than diagnosed diabetes.

Previous studies have shown that diabetes and stress hyperglycemia among hospitalized patients are important markers for poor clinical outcomes and in‐hospital mortality.[1, 2, 4] This study indicates that hospitalized patients with extreme hyperglycemia (peak serum glucose >200 mg/dL) were at a high risk of death for at least 5 years following discharge.

These findings, based on a large general sample of hospitalized patients, indicate that the extreme elevations in peak serum glucose convey a risk for all hospitalized patients, not only those with critical illness.[3, 18] Hyperglycemia appears to be an independent indicator of mortality risk and should be evaluated as a potential component within risk prediction tools. Further study is required to determine mechanisms for this risk association to identify what therapies, if any, might be used to minimize this risk.

The diagnosed diabetes group, which likely included some patients who also had extreme in‐hospital hyperglycemia, had a lower 1‐year risk of death than patients with hyperglycemia who did not have diabetes diagnosis. This may be an indication of the protective effect of blood glucose control, because patients with diabetes are more likely to receive therapy for hyperglycemia during and after hospitalization.

Classification of patients by several serum glucose levels (as opposed to a dichotomous classification, where hyperglycemia is either present or absent), showed that hyperglycemia constitutes a graded risk[5] for almost all outcomes examined, particularly mortality, AMI, and CVD.

Previous studies indicate that diabetes is observed in only 23% to 35% of hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia.[18, 19] We would expect higher risk for CV complications for patients with elevated glucose if the proportion of these patients who had undiagnosed diabetes was higher than the proportion estimated in the literature. However, we observed lower risk of CV complications (especially PVD and ESRD) for the elevated glucose group in the 1 and 5 years following discharge. In‐hospital hyperglycemia is not equivalent to undiagnosed diabetes.

There are several potential limitations in this study. The first is our method for ascertaining CV complications. Diverse disease definitions are used in medical literature, and similar studies using different definitions may yield different results, though we would not expect to find a wide range of variation. Second, our study did not include information about severity of diabetes and the persistence of elevated glucose; if available, this knowledge may provide better insight into patient experiences, especially in long‐term follow‐up. Third, results are also limited by the absence of data on cause of death, a potentially helpful means of identifying posthospitalization difficulties experienced by patients with hyperglycemia. Fourth, this study mainly compares experiences of patients with elevated peak serum glucose level to diabetes patients; it would be worthwhile to explore the impact of lower gradations of glucose levels.

We would like to emphasize that we did not confirm diabetes diagnosis following discharge for patients with hyperglycemia. However, we did not observe a high rate of complications at 5‐year follow‐up, particularly for ESRD. This may be because most patients with in‐hospital elevated glucose had early diabetes or transient hyperglycemia and therefore lower risk of long‐term diabetes‐specific consultations.

Hyperglycemia is an important independent indicator, carrying a greater risk for 1‐ and 5‐year mortality than diagnosed diabetes. However, it is unclear whether hospitalized patients with elevated peak serum glucose have early diabetes or their hyperglycemia reflects hospital stress or another comorbidity concept.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Amy Zierler and Allison Whalen O'Connor for their editorial assistance. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):553–591.

- , , , et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1119–1131.

- The NICE‐SUGAR Study Investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283–1297.

- , , , , , . Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in‐hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(3):978–982.

- , , , , . Hyperglycemia‐related mortality in critically ill patients varies with admission diagnosis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(12):3001–3009.

- , . Hospital management of hyperglycemia. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18(2):110–118.

- , , , et al. IScore: a risk score to predict death early after hospitalization for an acute ischemic stroke. Circulation. 2011;123(7):739–749.

- , . Does Stress‐induced hyperglycemia increase the risk of perioperative infectious complications in orthopaedic trauma patients? J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(12):752–756.

- . Metabolic mechanisms of stress hyperglycemia. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30(2):157–163.

- , , . Temporal changes in the outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in Ontario, 1992–1996. CMAJ. 1999;161(10):1257–1261.

- , , , et al. The accuracy of using integrated electronic health care data to identify patients with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(3):606–611.

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(suppl 1):s43–s48.

- . Dealing with competing risks: testing covariates and calculating sample size. Stat Med. 2002;21(22):3317–3324.

- , , , . Competing risk analysis of events 10 years after revascularization. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2010;44(5):279–288.

- , , , , , . Risk‐adjusting hospital inpatient mortality using automated inpatient, outpatient, and laboratory databases. Med Care. 2008;46(3):232–239.

- , , , . The Kaiser Permanente inpatient risk adjustment methodology was valid in an external patient population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):798–803.

- , , , . Improved comorbidity adjustment for predicting mortality in medicare populations. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(4):1103–1120.

- , , , et al. Glucose metabolism in patients with acute myocardial infarction and no previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359(9324):2140–2144.

- , , , et al. Disorders of glucose metabolism in acute stroke patients: an underrecognized problem. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(4):792–797.

Hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients is frequently observed and is recognized as an important threat to the health of patients with varying levels of illness, independent of diabetes status.[1, 2, 3, 4] Previous studies have found that in‐hospital hyperglycemia is associated with higher short‐term mortality rates,[5, 6, 7] longer lengths of stay, and higher rates of admission to intensive care units.[4]

In‐hospital hyperglycemia may be the result of diabetes mellitus or stress associated with hospitalization. The mechanism of stress hyperglycemia differs from diabetic hyperglycemia and can occur independently of diabetes status.[8] Stress hyperglycemia is characterized by rapid onset of insulin resistance, which normally takes months or years in diabetes mellitus. It develops in association with or because of other stressor such as infection or inflammatory processes.[9]

To our knowledge, no long‐term follow‐up study on hospitalized patients with elevated glucose levels but without a diabetes diagnosis has ever been conducted. In this study, we measured the 1‐ and 5‐year risk of mortality and diabetes‐related diseases for hospitalized patients with a diabetes diagnosis compared with patients grouped according to their peak in‐hospital serum glucose level. Our primary comparison was between patients with diagnosed diabetes and those with peak serum glucose >200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), but we also examined 4 other categories of peak serum glucose: 140 to 200 mg/dL (7.811.1 mmol/L), 108 to 140 mg/dL (6.07.8 mmol/L), and <108 mg/dL (<6.0 mmol/L).

METHODS

Study Base

The study included all adult patients (excluding patients admitted to psychiatry and obstetrics) admitted to The Ottawa Hospital (TOH) between January 1, 1996 and March 31, 2008 and discharged alive. Included patients were 18 years or older and had complete medical record abstracts. TOH is the primary hospital in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, and the main tertiary hospital in the Champlain Local Health Integration Network, the public healthcare authority for the Ottawa region. This study was approved by The Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Data Sources

The Ottawa Hospital Data Warehouse (OHDW) is a repository for data from the hospital's patient information systems. These systems include patient registration information, discharge abstract, and laboratory, pharmacy, and radiology results. OHDW was used to determine each patient's age, gender, diagnoses, pharmacy orders, laboratory test results, in‐hospital comorbidities, most responsible hospital service, and admission urgency.

This dataset was linked to 3 population‐based administrative datasets and 1 derived cohort. Ontario's Registered Persons Database (RPDB) is a population‐based registry containing date of death (if applicable) as well as eligibility status for the provincial universal health insurance program, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP).[10] The OHIP database records billing claims submitted by approximately 95% of Ontario physicians. Each claim contains a fee code describing the type of service provided and a location denoting where the service had taken place. The Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) records clinical, demographic, and administrative data for all hospital admissions and same‐day surgeries for all Ontario acute care hospitals since April 1, 1988. The Ontario Myocardial Infarction Database (OMID) contains records of all patients with a most responsible diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] code 410 or International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD‐10] code I21) identified from the DAD. Details on the creation of the OMID are provided in an earlier study.[10]

Variable Definitions

We identified the index admission of the TOH cohort in the DAD using a unique encrypted health insurance number, admission and discharge dates, and the institution number. To avoid double counting, patients with the same encrypted health insurance number who were discharged from an institution and admitted to another within 2 days were classified as transfers and counted as 1 hospitalization.

Diabetes and cardiovascular (CV) complications (acute myocardial infarction [AMI], congestive heart failure [CHF], cardiovascular disease [CVD], peripheral vascular disease [PVD], and end‐stage renal disease [ESRD]) were identified in the discharge abstract as the most responsible diagnosis for the admission as well as postadmission comorbidities. The discharge abstract records diagnostic codes according to ICD‐9 (April 1, 1988March 31, 2002) or ICD‐10 (April 1, 2002March 1, 2009).

Each hospitalization was classified into 1 of 6 mutually exclusive diabetes status categories based on diagnostic codes, serum glucose test results, and pharmacy records. The diagnosed diabetes group included hospitalizations with any diagnostic code of diabetes in the discharge abstract or any order for a diabetes medication during hospitalization. Eligible medications included acarbose, acetohexamide, chlorpropamide, glibenclamide, gliclazide, glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide, insulin, metformin, nateglinide, pioglitazone, repaglinide, rosiglitazone, and tolbutamide. A chart validation study showed excellent ascertainment of diabetes status using these methods (correct classification 88.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 85.791.3 with weighted kappa=0.89; 95% CI: 0.85‐0.92).[11, 12] Patients without diagnosed diabetes were classified according to their peak serum glucose value during the index hospitalization: <108 mg/dL (<6.0 mmol/L), 108 to 140 mg/dL (6.07.8 mmol/L), 140 to 200 mg/dL (7.811.1 mmol/L), >200 mg/dL (>11.1 mmol/L); hospitalizations in which glucose levels were not obtained were classified as unknown. These peak serum glucose categories are based on the World Health Organization's definition of diabetes and poor glucose tolerance.[12]

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all‐cause postdischarge mortality determined by linking the index admission to the RPDB. Secondary outcomes were CV complications, including: AMI (determined by linking to the OMID); hospitalization for CHF (determined by linking to the DAD for primary diagnosis of 425, 428, 514, 518.4 or I50, I42.0, I42.6, I42.7, I42.8, I42.9, I43, J81), CVD (determined by linking to the DAD for primary diagnosis of 430, 431, 432, 434, 436 or I60, I61, I62, I63, I64, G46), PVD (determined by primary diagnosis of 96.11, 96.12, 96.13, 96.14, 96.15 [excluded if in conjunction with 170, 171, 213, 730, 740759, 800900, 901904, 940950], 50.18, 51.25, 51.29 [excluded if in conjunction with 414.1, 441, 44] or 1VC93, 1VG93, 1VQ93, 1WA93, 1WE93, 1WJ93, 1WL93, 1WM93 [excluded if in conjunction with C40, C41, C46.1, C47, C49, D160, M46.2, M86, M87, M89.6, M90.0‐M90.5, Q00, Q38‐Q40, S02.0, S09.0, S04.0, S15, S25, T26), and 1KG50, 1KG57, 1KG76, 1KG35HAC1, 1KG35HHC1 [excluded if in conjunction with I60, I67.1, I71, I72, 177.0, 179.0]), and ESRD (determined by 403.9, 404.9,584, 585, 586, 788.5 or I12, I13, N17, N18, N19, R34).

Analysis

We identified all encounters of cohort patients in any Ontario acute‐care hospital within 5 years following the index discharge. Patients not covered by provincial health insurance (OHIP) were excluded.

We first measured crude mortality and morbidity rates by patient category (diagnosed diabetes and glucose levels). Next, we compared the unadjusted outcomes and baseline characteristics (age, sex, previous inpatient and emergency admissions, and disease at admission) between groups using a [2] test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

Due to the violation of proportional hazards, we used the Weibull accelerated failure time model to calculate the hazard of death associated with diabetes status or serum glucose level. Consistency of the probability plots confirmed appropriateness of using the Weibull function. Competing risk is defined as a type of failure that prevents the observation of the event of interest or fundamentally alters the probability of its occurrence.[13, 14] In the comorbidity analyses, death is a competing risk for all other outcomes. We calculated the multivariate competing risk hazard for each outcome of interest except death. Each model was adjusted for potential confounders: baseline risk of in‐hospital mortality, common comorbidities, most responsible hospital service, and the number of previous inpatient admissions and emergency department visits to TOH in the previous 6 months. The probability of dying during the admission was calculated using the Escobar model, which predicts the in‐hospital probability of dying using data available at the time of admission to the hospital.[15] The Escobar model has been validated in the study population.[16] The baseline probability of dying was based on age, sex, acuity of admission, primary condition, Charlson comorbidity score,[17] and the laboratory‐based acute physiology score.[15] The Charlson comorbidity score was calculated using weights from Schneeweiss et al.[17] Kaplan‐Meier survival curves were created for both adjusted and unadjusted models. Death was used as the main censoring variable when analyzing nonfatal outcomes at 1‐ and 5‐year follow‐up.

Adjusted models were constructed using a stepwise selection technique and compared with Akaike and Bayesian information criteria values. For all tests, significance was defined as a P value of 0.05 or less.

We recognize that the cohort may contain more than 1 index hospitalization per patient. However, repeated analyses using only the first or last encounter per patient produced nearly identical hazard ratios (HRs) and CIs.

RESULTS

Between January 1, 1996 and March 31, 2008, 194,641 nonpsychiatric and nonobstetric adults were admitted to TOH. Seventeen patients were excluded because they were ineligible for healthcare coverage and had no encounter with the Ontario healthcare system following discharge from hospital, and 11,175 of the admissions ended in death. The final cohort consisted of 114,764 unique individuals representing 183,449 encounters.

Patients had a mean age of 59.5 years (standard deviation: 18.0) and 48.9% were male. The baseline risk of dying during hospitalization was 4.8%.

Table 1 describes patients by diabetes and peak serum glucose status. Patients with diagnosed diabetes were more likely to be older and male. Patients with elevated peak serum glucose (>200 mg/dL; >11.1 mmol/L) were younger than the diagnosed diabetes group and had a higher baseline probability of in‐hospital death (9.4%, 95% CI: 9.09.7). Patients in these 2 groups had more inpatient admissions within the previous 6 months compared to the groups with other peak serum glucose values.

| Serum Glucose Level, mg/dL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed Diabetes, n=32,774, 17.9% | >200, n=5,082, 2.8% | 140200, n=25,857, 14.1% | 108140, n=38,741, 21.1% | <108, n=27,603, 15.0% | Unknown, n=53,392, 29.1% | |

| ||||||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 65.8 (14.1) | 64.3 (17.0)a | 63.9 (17.3)a | 60.9 (18.6)a | 54.3 (19.7)a | 54.8 (16.9)a |

| Risk‐adjusted mortality at admission, mean (SD) | 0.08 (0.12) | 0.09 (0.12)a | 0.07 (0.10)a | 0.05 (0.09)a | 0.04 (0.07)a | 0.01 (0.04)a |

| Sex, male, no. (%) | 18,200 (55.5) | 2,610 (51.4)a | 13,477 (52.1)a | 19,495 (50.3)a | 12,907 (46.8)a | 22,951 (43.0)a |

| No. of previous inpatient admissions, 6 months (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 22,780 (69.5) | 3,576 (70.4) | 19,118 (73.9)a | 28,827 (74.4)a | 20,354 (73.7)a | 43,317 (81.1)a |

| 1 | 6,470 (19.7) | 962 (18.9) | 4,484 (17.3)a | 6,526 (16.9)a | 4,744 (17.2)a | 7,360 (13.8)a |

| 2+ | 3,524 (10.8) | 544 (10.7) | 2,255 (8.7)a | 3,388 (9.1)a | 2,505 (9.1)a | 2,715 (5.1)a |

| No. of previous emergency admissions (6 months) (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 15,518 (47.4) | 2,638 (51.9)a | 12,681 (49.0)a | 16,584 (42.8)a | 13,039 (47.2) | 43,112 (80.8)a |

| 1 | 9,665 (29.5) | 1,490 (29.3)a | 8,339 (32.3)a | 13,829 (35.7)a | 8,709 (31.6) | 6,533 (12.2)a |

| 2+ | 7,591 (23.2) | 954 (18.8)a | 4,837 (18.7)a | 8,328 (21.5)a | 5,855 (21.2) | 3,747 (7.0)a |

| Emergency admission at index hospitalization (%) | 25,420 (77.6) | 4,178 (82.2)a | 20,284 (78.5)a | 33,282 (85.9)a | 23,598 (85.5)a | 15,039 (28.2)a |

| Length of stay, d (mean/SD) | 12.4 (22.3) | 15.8 (30.0)a | 11.9 (17.1)a | 8.5 (12.2)a | 6.3 (9.5)a | 3.4 (4.9)a |

| Disease at index hospitalization (%) | ||||||

| PVD | 2,783 (8.5) | 257 (5.1)a | 1,387 (5.4)a | 1,372 (3.5)a | 908 (3.3)a | 965 (1.8)a |

| Pneumonia | 3,308 (10.1) | 658 (13.0)a | 2,577 (10.0) | 2,809 (7.3)a | 1,220 (4.4)a | 399 (0.8)a |

| UTI | 3,549 (10.8) | 665 (13.1)a | 2,660 (10.3)a | 3,336 (8.6)a | 1,559 (5.7)a | 929 (1.7)a |

| IHD | 8,957 (27.3) | 1,086 (21.4)a | 4,714 (18.2)a | 5,306 (13.7)a | 3,100 (11.2)a | 2,842 (5.3)a |

| Hypertension | 10,864 (33.2) | 1,115 (21.9)a | 5,155 (19.9)a | 5,880 (15.2)a | 3,045 (11.0)a | 3,211 (6.0)a |

| Arrhythmia | 5,010 (15.3) | 823 (16.2) | 3,768 (14.6)a | 3,718 (9.6)a | 2,046 (7.4)a | 1,172 (2.2)a |

| CHF | 570 (17.5) | 763 (15.0)a | 2,761 (10.7)a | 2,449 (6.3)a | 1,121 (4.1)a | 386 (0.7)a |

| Diagnoses of diabetes in the next year (%) | 126 (2.5) | 368 (1.4) | 370 (1.0) | 215 (0.8) | 540 (1.0) | |

| Diagnoses of diabetes in the next 5 years (%) | 310 (6.1) | 981 (3.8) | 916 (2.4) | 434 (1.7) | 1,317 (2.5) | |

| First 3 most common primary discharge codes | AHD I251 (5.7%), HF I50 (3.1%), NSTEMI I214 (1.6%) | AHD I251 (2.7%), COPD J441 (2.1%), HF I50 (2.0%) | AHD I251 (4.0%), Pneumonia J189 (1.6%), HF I50 (1.5%) | AHD I251 (1.6%), Pneumonia J189 (1.5%), CA D700 (1.3%) | AHD I251 (1.8%), AA K359 (1.7%), UA I200 (1.2%) | OA M171 (2.3%), AHD I251 (2.2%), OA M170 (1.7%) |

Of the 5082 patients classified with a peak serum glucose measurement >200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), 15% had 2 and 8% had more than 2 serum glucose measurements that exceeded this threshold. For the remaining patients (with 1 peak serum glucose measurement >200 mg/dL), 52% had additional serum glucose measurements over 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L).

Table 2 presents crude 1‐ and 5‐year mortality and morbidity rates by patient group. The mortality rate is the percentage of patients who died within 1 year and 5 years of their index admission, with or without developing a CV complication. Morbidity rate describes the percentage who developed the complication among patients who survived after discharge or developed the complication prior to death within a 1‐year and 5‐year period. During the 1‐year follow‐up period, the crude mortality rate among patients with elevated peak serum glucose was higher than all other groups (25.4% vs 20.6% for diagnosed diabetes and 7.4% to 22.5% for other peak serum glucose levels; all P<0.0001). For the 5‐year follow‐up, the gap between patients with elevated peak serum glucose and those with diagnosed diabetes lessened but remained significant (45.1% vs 41.7%; P<0.0001). In the 1‐year follow‐up, patients with diagnosed diabetes had significantly higher morbidity rates than all other groups except for AMI. The difference in the rate of AMI for diagnosed diabetes and patients with elevated glucose was not statistically significant.

| Diagnosed Diabetes, n=32,774 | Serum Glucose Level (mg/dL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >200, n=5,082 | 140200, n=25,857 | 108140, n=38,741 | <108, n=27,603 | Unknown, n=53,392 | ||

| ||||||

| All‐cause death | ||||||

| 1 year | 6,762 (20.6) | 1,293 (25.4)a | 5,309 (20.5) | 7,212 (18.6)a | 4,178 (15)a | 3,969 (7.4)a |

| 5 years | 13,659 (41.7) | 2,292 (45.1)a | 9,871 (38.2)a | 13,256 (34.2)a | 7,606 (27.6)a | 98,614 (16.1)a |

| AMI | ||||||

| 1 year | 728 (2.8) | 104 (2.7) | 326 (1.6)a | 386 (1.2)a | 172 (0.7)a | 218 (0.4)a |

| 5 years | 1,687 (8.4) | 182 (6.3)a | 687 (4.2)a | 837 (3.2)a | 436 (2.2)a | 633 (1.4)a |

| CVD | ||||||

| 1 year | 582 (2.2) | 71 (1.9) | 306 (1.5)a | 403 (1.3)a | 251 (1.1)a | 195 (0.4)a |

| 5 years | 1,153 (5.8) | 143 (5.0) | 623 (3.8)a | 872 (3.4)a | 470 (2.3)a | 534 (1.2)a |

| CHF | ||||||

| 1 year | 2,260 (8.4) | 245 (6.3)a | 870 (4.2)a | 1,023 (3.2)a | 516 (2.2)a | 362 (0.7)a |

| 5 years | 3,830 (17.7) | 395 (12.9)a | 1,529 (9.0)a | 1,802 (6.8)a | 960 (4.7)a | 884 (2.0)a |

| PVD | ||||||

| 1 year | 795 (3.0) | 24 (0.6)a | 114 (0.6)a | 154 (0.5)a | 97 (0.4)a | 141 (0.3)a |

| 5 years | 1,547 (7.8) | 50 (1.8)a | 220 (1.4)a | 275 (1.1)a | 192 (1.0)a | 295 (0.7)a |

| ESRD | ||||||

| 1 year | 953 (3.6) | 104 (2.7)a | 403 (1.9)a | 457 (1.4)a | 311 (1.3)a | 329 (0.7)a |

| 5 years | 1,938 (9.5) | 183 (6.3)a | 807 (4.9)a | 995 (3.8)a | 611 (3.0)a | 771 (1.7)a |

The 1‐year adjusted hazard ratios for mortality and CV complications are presented in Figure 1. After adjustment for baseline demographics and clinical and hospital factors, having a peak serum glucose level above 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) was an independent predictor of death. The mortality risk for this group in the year following discharge was 31% higher than patients with diagnosed diabetes (adjusted HR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.20‐1.43). There was no mortality risk difference between the group with diagnosed diabetes and the lower peak serum glucose levels (adjusted HR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.99‐1.11), 108160 mg/dL (6.07.8 mmol/L) (adjusted HR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.971.07); and <108 mg/dL (<6.0 mmol/L) (adjusted HR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.921.03). Adjusted HRs, with 95% CIs and P values for 5‐year follow‐up are presented in Figure 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios for morbidity showed a different pattern. Patients with diagnosed diabetes had a higher risk of developing complications in the year following discharge from the hospital (Figure 1). After adjusting for potential confounders, we found that patients with diagnosed diabetes had the same risk of AMI and CVD as patients with peak serum glucose levels above 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) (AMI, adjusted HR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.78‐1.18; CVD, adjusted HR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.61‐1.00) but a 36% to 57% higher AMI risk and 29% to 34% higher CVD risk than other peak serum glucose level groups. Compared to all peak serum glucose groups, patients with diagnosed diabetes had a significantly higher risk of developing CHF, PVD, and ESRD (Figure 1). Similarly, the 5‐year risk of AMI, CVD, CHF, PVD, and ESRD was higher for patients with diagnosed diabetes compared to all peak serum glucose groups (Figure 2).

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

The study found that in‐hospital hyperglycemia was a strong predictor of mortality at 1‐ and 5‐years follow‐up, even after adjustment using well‐established and discriminating comorbidity measures. Extreme in‐hospital hyperglycemia was a stronger predictor of mortality than diagnosed diabetes.

Previous studies have shown that diabetes and stress hyperglycemia among hospitalized patients are important markers for poor clinical outcomes and in‐hospital mortality.[1, 2, 4] This study indicates that hospitalized patients with extreme hyperglycemia (peak serum glucose >200 mg/dL) were at a high risk of death for at least 5 years following discharge.

These findings, based on a large general sample of hospitalized patients, indicate that the extreme elevations in peak serum glucose convey a risk for all hospitalized patients, not only those with critical illness.[3, 18] Hyperglycemia appears to be an independent indicator of mortality risk and should be evaluated as a potential component within risk prediction tools. Further study is required to determine mechanisms for this risk association to identify what therapies, if any, might be used to minimize this risk.

The diagnosed diabetes group, which likely included some patients who also had extreme in‐hospital hyperglycemia, had a lower 1‐year risk of death than patients with hyperglycemia who did not have diabetes diagnosis. This may be an indication of the protective effect of blood glucose control, because patients with diabetes are more likely to receive therapy for hyperglycemia during and after hospitalization.

Classification of patients by several serum glucose levels (as opposed to a dichotomous classification, where hyperglycemia is either present or absent), showed that hyperglycemia constitutes a graded risk[5] for almost all outcomes examined, particularly mortality, AMI, and CVD.

Previous studies indicate that diabetes is observed in only 23% to 35% of hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia.[18, 19] We would expect higher risk for CV complications for patients with elevated glucose if the proportion of these patients who had undiagnosed diabetes was higher than the proportion estimated in the literature. However, we observed lower risk of CV complications (especially PVD and ESRD) for the elevated glucose group in the 1 and 5 years following discharge. In‐hospital hyperglycemia is not equivalent to undiagnosed diabetes.

There are several potential limitations in this study. The first is our method for ascertaining CV complications. Diverse disease definitions are used in medical literature, and similar studies using different definitions may yield different results, though we would not expect to find a wide range of variation. Second, our study did not include information about severity of diabetes and the persistence of elevated glucose; if available, this knowledge may provide better insight into patient experiences, especially in long‐term follow‐up. Third, results are also limited by the absence of data on cause of death, a potentially helpful means of identifying posthospitalization difficulties experienced by patients with hyperglycemia. Fourth, this study mainly compares experiences of patients with elevated peak serum glucose level to diabetes patients; it would be worthwhile to explore the impact of lower gradations of glucose levels.

We would like to emphasize that we did not confirm diabetes diagnosis following discharge for patients with hyperglycemia. However, we did not observe a high rate of complications at 5‐year follow‐up, particularly for ESRD. This may be because most patients with in‐hospital elevated glucose had early diabetes or transient hyperglycemia and therefore lower risk of long‐term diabetes‐specific consultations.

Hyperglycemia is an important independent indicator, carrying a greater risk for 1‐ and 5‐year mortality than diagnosed diabetes. However, it is unclear whether hospitalized patients with elevated peak serum glucose have early diabetes or their hyperglycemia reflects hospital stress or another comorbidity concept.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Amy Zierler and Allison Whalen O'Connor for their editorial assistance. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

Hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients is frequently observed and is recognized as an important threat to the health of patients with varying levels of illness, independent of diabetes status.[1, 2, 3, 4] Previous studies have found that in‐hospital hyperglycemia is associated with higher short‐term mortality rates,[5, 6, 7] longer lengths of stay, and higher rates of admission to intensive care units.[4]

In‐hospital hyperglycemia may be the result of diabetes mellitus or stress associated with hospitalization. The mechanism of stress hyperglycemia differs from diabetic hyperglycemia and can occur independently of diabetes status.[8] Stress hyperglycemia is characterized by rapid onset of insulin resistance, which normally takes months or years in diabetes mellitus. It develops in association with or because of other stressor such as infection or inflammatory processes.[9]

To our knowledge, no long‐term follow‐up study on hospitalized patients with elevated glucose levels but without a diabetes diagnosis has ever been conducted. In this study, we measured the 1‐ and 5‐year risk of mortality and diabetes‐related diseases for hospitalized patients with a diabetes diagnosis compared with patients grouped according to their peak in‐hospital serum glucose level. Our primary comparison was between patients with diagnosed diabetes and those with peak serum glucose >200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), but we also examined 4 other categories of peak serum glucose: 140 to 200 mg/dL (7.811.1 mmol/L), 108 to 140 mg/dL (6.07.8 mmol/L), and <108 mg/dL (<6.0 mmol/L).

METHODS

Study Base