User login

Uterine fibroids registry looks to provide comparative treatment data

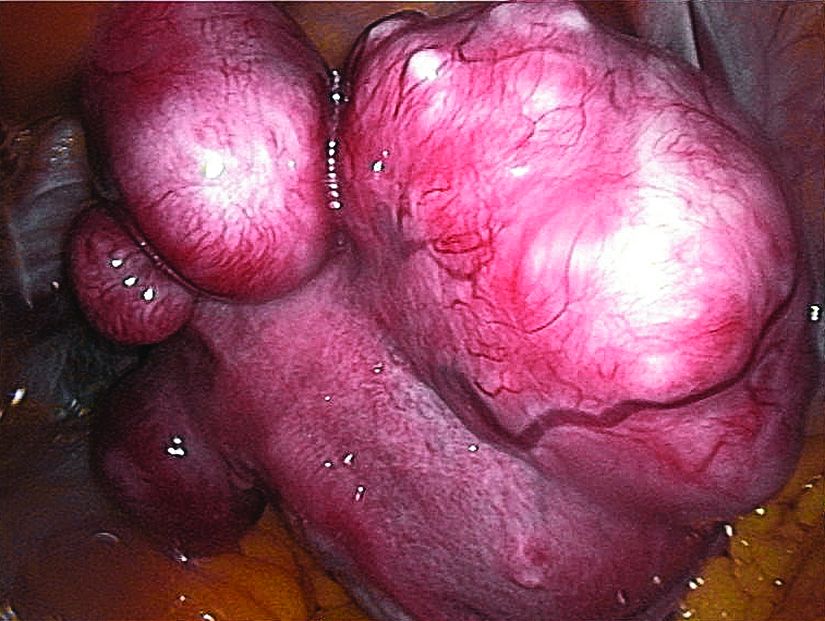

Early findings from a uterine fibroids registry suggest more than half of enrolled women chose an alternative to hysterectomy, underscoring the need to study the efficacy of these uterine-sparing treatment options, said Elizabeth A. Stewart, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates.

There is very little evidence on the comparative efficacy of uterine fibroid treatment options so the COMPARE-UF (Comparing Options for Management: Patient-Centered Results for Uterine Fibroids) registry was initiated for women who choose procedural therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Data at the nine clinical centers – representing rural and urban populations – are being collected regarding hysterectomy, myomectomy (abdominal, hysteroscopic, vaginal, and laparoscopic/robotic), endometrial ablation, radiofrequency fibroid ablation, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound, and therapeutic use of progestin-releasing intrauterine devices.

A total of 16% of the women were under age 35, and 40% were aged 40 years or younger. “The fact that a sizable proportion of women are under age 40 suggests that with long-term follow-up, data on reproductive outcomes can be obtained as these women seek pregnancy,” Dr. Stewart and her associates noted.

Although African American women make up only 13% of the U.S. population, they constitute 42% of enrollment in COMPARE-UF, the investigators reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. African American women chose similar or greater numbers of each type of myomectomy and uterine embolization as white women chose.

The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The registry is supported by AHRQ and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Stewart reported personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas, Pharma, Bayer, Gynesonics, and Myovant Sciences. Several researchers reported grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this study, and the remainder of the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stewart EA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.004.

Early findings from a uterine fibroids registry suggest more than half of enrolled women chose an alternative to hysterectomy, underscoring the need to study the efficacy of these uterine-sparing treatment options, said Elizabeth A. Stewart, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates.

There is very little evidence on the comparative efficacy of uterine fibroid treatment options so the COMPARE-UF (Comparing Options for Management: Patient-Centered Results for Uterine Fibroids) registry was initiated for women who choose procedural therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Data at the nine clinical centers – representing rural and urban populations – are being collected regarding hysterectomy, myomectomy (abdominal, hysteroscopic, vaginal, and laparoscopic/robotic), endometrial ablation, radiofrequency fibroid ablation, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound, and therapeutic use of progestin-releasing intrauterine devices.

A total of 16% of the women were under age 35, and 40% were aged 40 years or younger. “The fact that a sizable proportion of women are under age 40 suggests that with long-term follow-up, data on reproductive outcomes can be obtained as these women seek pregnancy,” Dr. Stewart and her associates noted.

Although African American women make up only 13% of the U.S. population, they constitute 42% of enrollment in COMPARE-UF, the investigators reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. African American women chose similar or greater numbers of each type of myomectomy and uterine embolization as white women chose.

The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The registry is supported by AHRQ and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Stewart reported personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas, Pharma, Bayer, Gynesonics, and Myovant Sciences. Several researchers reported grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this study, and the remainder of the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stewart EA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.004.

Early findings from a uterine fibroids registry suggest more than half of enrolled women chose an alternative to hysterectomy, underscoring the need to study the efficacy of these uterine-sparing treatment options, said Elizabeth A. Stewart, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and her associates.

There is very little evidence on the comparative efficacy of uterine fibroid treatment options so the COMPARE-UF (Comparing Options for Management: Patient-Centered Results for Uterine Fibroids) registry was initiated for women who choose procedural therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Data at the nine clinical centers – representing rural and urban populations – are being collected regarding hysterectomy, myomectomy (abdominal, hysteroscopic, vaginal, and laparoscopic/robotic), endometrial ablation, radiofrequency fibroid ablation, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound, and therapeutic use of progestin-releasing intrauterine devices.

A total of 16% of the women were under age 35, and 40% were aged 40 years or younger. “The fact that a sizable proportion of women are under age 40 suggests that with long-term follow-up, data on reproductive outcomes can be obtained as these women seek pregnancy,” Dr. Stewart and her associates noted.

Although African American women make up only 13% of the U.S. population, they constitute 42% of enrollment in COMPARE-UF, the investigators reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. African American women chose similar or greater numbers of each type of myomectomy and uterine embolization as white women chose.

The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The registry is supported by AHRQ and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Stewart reported personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas, Pharma, Bayer, Gynesonics, and Myovant Sciences. Several researchers reported grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this study, and the remainder of the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stewart EA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.004.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of the initial 2,031 women enrolled in the registry, hysterectomy was chosen by 38%, and myomectomies were chosen by 46%.

Study details: Initial results from the COMPARE-UF registry.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Stewart reported personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Astellas, Pharma, Bayer, Gynesonics, and Myovant Sciences. Several researchers reported grants from pharmaceutical companies outside this study, and the remainder of the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Stewart EA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.004.

Dermatologic complaints prolong hospital stay for hematologic cancer

and are associated with an increased mean length of hospital stay, according to a large retrospective chart review from a major cancer center.

The substantial burden imposed by dermatologic complications in patients with cancer, particularly a hematologic malignancy, highlights the importance of greater collaboration between oncology and dermatology services to mitigate the impact of these events on both quality of life and outcome, wrote Gregory S. Phillips of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and his associates. The study was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The data that produced these conclusions were drawn from a retrospective chart review of 11,533 cancer patients treated at the center during 2015. Of these, 412 (3.6%) were referred for a dermatology consultation.

Those who received a dermatology consultation were comparable for median age (60 years) and gender (roughly 50:50 male:female), compared with those who did not. However, the odds ratio (OR) for a dermatology consultation was 6.56 among those with a hematologic malignancy compared with those who had a solid tumor. In those with leukemia, the proportion receiving a dermatologic consult was nearly ninefold greater.

Whether or not undertaken in a patient with a hematologic malignancy, dermatologic consults correlated with significantly greater morbidity, as well as mortality. This included a longer median length of stay (11 vs. 5 days; P less than .0001) and a higher in-hospital rate of death (9% vs. 2%; P less than .0001), compared with patients not needing a dermatology consultation.

Of dermatologic consultations in the total study population, the most common were for inflammatory conditions (27%), infections (24%), and drug reactions (17%). Neoplasm was the dermatologic diagnosis in 10% of the total population, but in 13% of those with hematologic malignancies.

Inpatient dermatology consultations were most frequently ordered by the hematology-oncology service, accounting for 44% of the total, followed by the solid tumor oncology service (27%) and the surgery service (15%). Multiple consultations were more likely in patients with leukemia or lymphoma than other forms of cancer.

In the dermatology consult, biopsy was employed for diagnosis in only 18%. As for treatment, 42% received topical therapy alone, and 38% received a systemic therapy. Dermatologic consultations that subsequently involved consultation with another service such as allergy and immunology, were rare, occurring in only 4% of cases.

Furthermore, they suggested that the data support increased attention to dermatologic complications in cancer. Although the impact of consultations on outcome was not evaluated in this study, the authors cited another recent study in which there was a more than 2-day reduction in hospital stay when a dermatology consultation was employed in noncancer patients with an inflammatory skin disease (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Jun 1;153[6]:523-8). Moreover, they speculated that a prompt resolution of dermatologic complaints in cancer patients has implications for better outcomes if they result in fewer delays in anti-cancer therapy.

The study was partly funded by the a grant from the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Centers Program. Dr. Lacouture reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Adgero Biopharmaceuticals, Berg, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Foamix, Janssen, Legacy Healthcare, NovoCure, and Quintiles. Another author reported ties with Amgen, Roche, Eaisi, and P Value Communications.

SOURCE: Phillips GS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jun;78(6):1102-9.

and are associated with an increased mean length of hospital stay, according to a large retrospective chart review from a major cancer center.

The substantial burden imposed by dermatologic complications in patients with cancer, particularly a hematologic malignancy, highlights the importance of greater collaboration between oncology and dermatology services to mitigate the impact of these events on both quality of life and outcome, wrote Gregory S. Phillips of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and his associates. The study was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The data that produced these conclusions were drawn from a retrospective chart review of 11,533 cancer patients treated at the center during 2015. Of these, 412 (3.6%) were referred for a dermatology consultation.

Those who received a dermatology consultation were comparable for median age (60 years) and gender (roughly 50:50 male:female), compared with those who did not. However, the odds ratio (OR) for a dermatology consultation was 6.56 among those with a hematologic malignancy compared with those who had a solid tumor. In those with leukemia, the proportion receiving a dermatologic consult was nearly ninefold greater.

Whether or not undertaken in a patient with a hematologic malignancy, dermatologic consults correlated with significantly greater morbidity, as well as mortality. This included a longer median length of stay (11 vs. 5 days; P less than .0001) and a higher in-hospital rate of death (9% vs. 2%; P less than .0001), compared with patients not needing a dermatology consultation.

Of dermatologic consultations in the total study population, the most common were for inflammatory conditions (27%), infections (24%), and drug reactions (17%). Neoplasm was the dermatologic diagnosis in 10% of the total population, but in 13% of those with hematologic malignancies.

Inpatient dermatology consultations were most frequently ordered by the hematology-oncology service, accounting for 44% of the total, followed by the solid tumor oncology service (27%) and the surgery service (15%). Multiple consultations were more likely in patients with leukemia or lymphoma than other forms of cancer.

In the dermatology consult, biopsy was employed for diagnosis in only 18%. As for treatment, 42% received topical therapy alone, and 38% received a systemic therapy. Dermatologic consultations that subsequently involved consultation with another service such as allergy and immunology, were rare, occurring in only 4% of cases.

Furthermore, they suggested that the data support increased attention to dermatologic complications in cancer. Although the impact of consultations on outcome was not evaluated in this study, the authors cited another recent study in which there was a more than 2-day reduction in hospital stay when a dermatology consultation was employed in noncancer patients with an inflammatory skin disease (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Jun 1;153[6]:523-8). Moreover, they speculated that a prompt resolution of dermatologic complaints in cancer patients has implications for better outcomes if they result in fewer delays in anti-cancer therapy.

The study was partly funded by the a grant from the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Centers Program. Dr. Lacouture reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Adgero Biopharmaceuticals, Berg, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Foamix, Janssen, Legacy Healthcare, NovoCure, and Quintiles. Another author reported ties with Amgen, Roche, Eaisi, and P Value Communications.

SOURCE: Phillips GS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jun;78(6):1102-9.

and are associated with an increased mean length of hospital stay, according to a large retrospective chart review from a major cancer center.

The substantial burden imposed by dermatologic complications in patients with cancer, particularly a hematologic malignancy, highlights the importance of greater collaboration between oncology and dermatology services to mitigate the impact of these events on both quality of life and outcome, wrote Gregory S. Phillips of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and his associates. The study was published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The data that produced these conclusions were drawn from a retrospective chart review of 11,533 cancer patients treated at the center during 2015. Of these, 412 (3.6%) were referred for a dermatology consultation.

Those who received a dermatology consultation were comparable for median age (60 years) and gender (roughly 50:50 male:female), compared with those who did not. However, the odds ratio (OR) for a dermatology consultation was 6.56 among those with a hematologic malignancy compared with those who had a solid tumor. In those with leukemia, the proportion receiving a dermatologic consult was nearly ninefold greater.

Whether or not undertaken in a patient with a hematologic malignancy, dermatologic consults correlated with significantly greater morbidity, as well as mortality. This included a longer median length of stay (11 vs. 5 days; P less than .0001) and a higher in-hospital rate of death (9% vs. 2%; P less than .0001), compared with patients not needing a dermatology consultation.

Of dermatologic consultations in the total study population, the most common were for inflammatory conditions (27%), infections (24%), and drug reactions (17%). Neoplasm was the dermatologic diagnosis in 10% of the total population, but in 13% of those with hematologic malignancies.

Inpatient dermatology consultations were most frequently ordered by the hematology-oncology service, accounting for 44% of the total, followed by the solid tumor oncology service (27%) and the surgery service (15%). Multiple consultations were more likely in patients with leukemia or lymphoma than other forms of cancer.

In the dermatology consult, biopsy was employed for diagnosis in only 18%. As for treatment, 42% received topical therapy alone, and 38% received a systemic therapy. Dermatologic consultations that subsequently involved consultation with another service such as allergy and immunology, were rare, occurring in only 4% of cases.

Furthermore, they suggested that the data support increased attention to dermatologic complications in cancer. Although the impact of consultations on outcome was not evaluated in this study, the authors cited another recent study in which there was a more than 2-day reduction in hospital stay when a dermatology consultation was employed in noncancer patients with an inflammatory skin disease (JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Jun 1;153[6]:523-8). Moreover, they speculated that a prompt resolution of dermatologic complaints in cancer patients has implications for better outcomes if they result in fewer delays in anti-cancer therapy.

The study was partly funded by the a grant from the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Centers Program. Dr. Lacouture reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Adgero Biopharmaceuticals, Berg, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Foamix, Janssen, Legacy Healthcare, NovoCure, and Quintiles. Another author reported ties with Amgen, Roche, Eaisi, and P Value Communications.

SOURCE: Phillips GS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jun;78(6):1102-9.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Dermatologic complications are more common in hematologic than solid tumor cancers and correlate with adverse outcomes.

Major finding: In cancer patients, dermatologic consults are associated with longer hospital stay (11 vs. 5 days) and death (9% vs. 2%).

Study details: Retrospective chart review of inpatient dermatology consultations during 2015.

Disclosures: The study was partly funded by the a grant from the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Centers Program. Dr. Lacouture reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Adgero Biopharmaceuticals, Berg, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Foamix, Janssen, Legacy Healthcare, NovoCure, and Quintiles. Another author reported ties with Amgen, Roche, Eaisi, and P Value Communications.

Source: Phillips et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1102-9.

MDedge Psychcast: Episode 107

Dr. Worley uses a nautical metaphor to describe the phenomenon and possible ways to combat it.

Dr. Worley uses a nautical metaphor to describe the phenomenon and possible ways to combat it.

Dr. Worley uses a nautical metaphor to describe the phenomenon and possible ways to combat it.

An MRI Analysis of the Pelvis to Determine the Ideal Method for Ultrasound-Guided Bone Marrow Aspiration from the Iliac Crest

ABSTRACT

Use of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow has gained significant popularity. The iliac crest has been determined to be an effective site for harvesting mesenchymal stem cells. Review of the literature reveals that multiple techniques are used to harvest bone marrow aspirate from the iliac crest, but the descriptions are based on the experience of various authors as opposed to studied anatomy. A safe, reliable, and reproducible method for aspiration has yet to be studied and described. We hypothesized that there would be an ideal angle and distance for aspiration that would be the safest, most consistent, and most reliable. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we reviewed 26 total lumbar spine MRI scans (13 males, 13 females) and found that an angle of 24° should be used when entering the most medial aspect of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and that this angle did not differ between the sexes. The distance that the trocar can advance after entry before hitting the anterior ilium wall varied significantly between males and females, being 7.53 cm in males and 6.74 cm in females. In addition, the size of the PSIS table was significantly different between males and females (1.20 cm and 0.96 cm, respectively). No other significant differences in the measurements gathered were found. Using the data gleaned from this study, we developed an aspiration technique. This method uses ultrasound to determine the location of the PSIS and the entry point on the PSIS. This contrasts with most techniques that use landmark palpation, which is known to be unreliable and inaccurate. The described technique for aspiration from the PSIS is safe, reliable, reproducible, and substantiated by data.

The iliac crest is an effective site for harvesting bone marrow stem cells. It allows for easy access and is superficial in most individuals, allowing for a relatively quick and simple procedure. Use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for treatment of orthopedic injuries has grown recently. Whereas overall use has increased, review of the literature reveals very few techniques for iliac crest aspiration,1 but these are not based on anatomic relationships or studies. Hernigou and colleagues2,3 attempted to quantitatively evaluate potential “sectors” allowing for safe aspiration using cadaver and computed tomographic reconstruction imaging. We used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to analyze aspiration parameters. Owing to the ilium’s anatomy, improper positioning or aspiration technique during aspiration can result in serious injury.2,4-6 We hypothesized that there is an ideal angle and positioning for bone marrow aspiration from the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) that is safe, consistent, and reproducible. Although most aspiration techniques use landmark palpation, this is unreliable and inaccurate, especially when compared with ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19 We describe our technique using ultrasound to visualize patient anatomy and accurately determine anatomic entry with the trocar.

METHODS

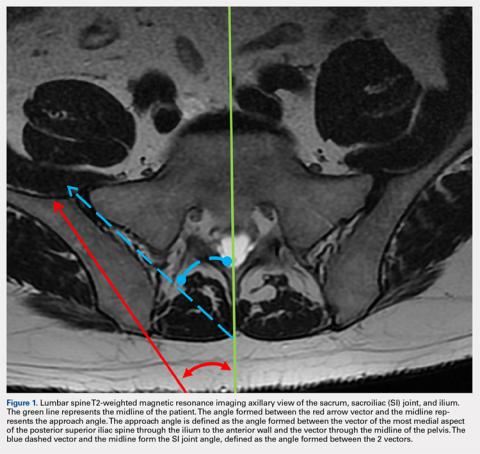

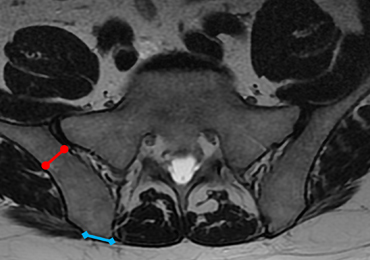

MRI scans of 26 patients (13 males, 13 females) were reviewed to determine average angles and distances. Axial T2-weighted views of the lumbar spine were used in all analyses. The sacroiliac (SI) joint angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector through the midline of the pelvis and the vector that is parallel to the SI joint. The approach angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector of the most medial aspect of the PSIS through the ilium to the anterior wall and the vector through the midline of the pelvis (Figure 1).

Continue to: For the 13 males, the mean SI joint...

RESULTS

The results are reported in the Table.

Table. Measurements of Patients Taken on Axial T2-Weighted Views of Lumbosacral MRI Scansa

Patient | SI Joint Angle (°) | Approach Angle (°) | PSIS Table Width (cm) | PSIS to Anterior Ilium Wall (cm) | Perpendicular Distance PSIS to Anterior Joint (cm) | Post Ilium Wall to SI Joint Width (cm) |

Males | ||||||

1 | 28.80 | 19.50 | 1.24 | 8.80 | 4.16 | 1.52 |

2 | 31.80 | 27.60 | 1.70 | 7.89 | 3.49 | 1.02 |

3 | 33.70 | 27.70 | 1.12 | 8.14 | 3.15 | 1.28 |

4 | 23.70 | 26.40 | 0.95 | 6.66 | 3.22 | 0.65 |

5 | 35.90 | 28.40 | 0.84 | 7.60 | 2.57 | 0.95 |

6 | 33.80 | 29.30 | 1.20 | 7.73 | 2.34 | 0.90 |

7 | 30.30 | 21.20 | 1.36 | 8.44 | 3.95 | 1.18 |

8 | 34.50 | 20.40 | 1.53 | 7.08 | 3.98 | 1.56 |

9 | 28.70 | 24.00 | 1.34 | 8.19 | 3.51 | 1.31 |

10 | 22.40 | 20.10 | 1.37 | 7.30 | 3.87 | 1.28 |

11 | 33.60 | 20.80 | 0.88 | 6.43 | 3.26 | 0.94 |

12 | 48.50 | 31.00 | 1.15 | 6.69 | 2.97 | 1.38 |

13 | 20.20 | 20.90 | 0.94 | 6.95 | 3.79 | 1.05 |

Averages | 31.22 | 24.41 | 1.20 | 7.53 | 3.40 | 1.16 |

Standard Deviation | 7.18 | 4.11 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.26 |

Females | ||||||

14 | 22.80 | 23.20 | 1.54 | 7.21 | 3.45 | 1.39 |

15 | 33.30 | 21.40 | 1.09 | 7.26 | 3.57 | 0.98 |

16 | 19.70 | 15.60 | 0.78 | 8.32 | 3.76 | 0.86 |

17 | 17.50 | 15.60 | 0.61 | 7.57 | 3.37 | 1.03 |

18 | 48.20 | 26.60 | 0.94 | 6.62 | 3.16 | 0.71 |

19 | 38.20 | 28.30 | 0.90 | 6.32 | 2.23 | 0.91 |

20 | 44.50 | 31.70 | 0.99 | 6.19 | 3.06 | 0.76 |

21 | 24.10 | 18.00 | 0.92 | 6.99 | 3.23 | 0.71 |

22 | 17.20 | 14.80 | 0.81 | 6.00 | 2.81 | 1.13 |

23 | 42.00 | 38.50 | 1.00 | 5.33 | 2.47 | 1.42 |

24 | 32.00 | 25.50 | 0.98 | 6.01 | 2.79 | 1.21 |

25 | 24.70 | 24.80 | 0.87 | 6.09 | 2.79 | 1.02 |

26 | 19.80 | 22.30 | 1.04 | 7.71 | 2.37 | 1.36 |

Averages | 29.54 | 23.56 | 0.96 | 6.74 | 3.00 | 1.04 |

Standard Deviation | 10.84 | 6.88 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

All patients Averages | 30.38 | 23.98 | 1.08 | 7.14 | 3.20 | 1.10 |

Standard Deviation | 9.05 | 5.57 | 0.26 | 0.88 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

aStatistical significance is denoted as P < .02.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PSIS, posterior iliac spine; SI, sacroiliac.

For the 13 males, the mean SI joint angle was 31.22° ± 7.18° (range, 20.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 24.41° ± 4.11° (range, 19.50° to 31.00°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.20 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.84 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.53 cm ± 0.75 cm (range, 6.43 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.40 cm ± 0.56 cm (range, 2.34 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.16 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

For the 13 females, the mean SI joint angle was 29.54° ± 10.84° (range, 17.20° to 48.20°). The mean approach angle was 23.56° ± 6.88° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 0.96 cm ± 0.21 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.54 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 6.74 cm ± 0.85 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.32 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.00 cm ± 0.48 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 3.76 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.04 cm ± 0.25 cm (range, 0.71 cm to 1.42 cm).

For the 26 total patients, the mean SI joint angle was 30.38° ± 9.05° (range, 17.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 23.98° ± 5.57° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.08 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.14 cm ± 0.88 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.20 cm ± 0.55 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.10 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

There was a statistically significant difference between the male and female groups for the maximum distance the trocar can be advanced from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall (P < .02), and a statistically significant difference for the PSIS table width (P < .02). There were no significant differences between the male and female groups for the approach angle, the SI joint angle, the perpendicular distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium, and the minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint.

Continue to: The patient is brought to the procedure...

TECHNIQUE: ILIAC CREST (PSIS) BONE MARROW ASPIRATION

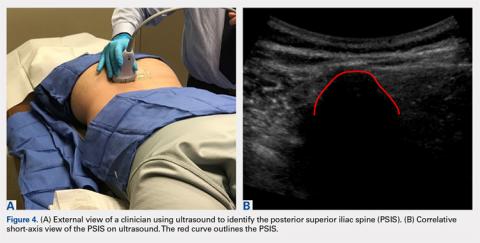

The patient is brought to the procedure room and placed in a prone position. The donor site is prepared and draped in the usual sterile manner. Ultrasound is used to identify the median sacral crest in a short-axis view. The probe is then moved laterally to identify the PSIS (Figures 4A, 4B).

The crosshairs on the ultrasound probe are used to mark the center lines of each plane. The central point marks the location of the PSIS. Alternatively, an in-plane technique can be used to place a spinal needle on the exact entry point on the PSIS. Once the PSIS and entry point are identified, the site is blocked with 10 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine.

Prior to introduction of the trocar, all instrumentation is primed with heparin and syringes are prepped with anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution, solution A. A stab incision is made at the site. The trocar is placed at the entry point, which should be centered in a superior-inferior plane and at the most medial point of the PSIS. Starting with the trocar vertical, the trocar is angled laterally 24° by dropping the hand medially toward the midline. No angulation cephalad or caudad is necessary, but cephalad must be avoided so as not to skive superiorly. This angle, which is recommended for both males and females, allows for the greatest distance the trocar can travel in bone before hitting the anterior ilium wall. A standard deviation of 5.57° is present, which should be considered. Steady pressure should be applied with a slight twisting motion on the PSIS. If advancement of the trocar is too difficult, a mallet or drill can be used to assist in penetration.

With the trocar advanced into the bone 1 cm, the trocar needle is removed while the cannula remains in place. The syringe is attached to the top of the cannula. The syringe plunger is pulled back to aspirate 20 mL of bone marrow. The cannula and syringe assembly are advanced 2 cm farther into the bone to allow for aspiration of a new location within the bone marrow cavity, and 20 mL of bone marrow are again aspirated. This is done a final time, advancing the trocar another 2 cm and aspirating a final 20 mL of bone marrow. The entire process should yield roughly 60 mL of bone marrow from one side. If desired, the same process can be repeated for the contralateral PSIS to yield a total of 120 mL of bone marrow from the 2 sites.

Based on our data, the average distance to the anterior ilium wall was 7 cm, but the shortest distance noted in this study was 5 cm. On the basis of the data presented, this technique allows for safe advancement based on even the shortest measured distance, without fear of puncturing the anterior ilium wall. Perforation could damage the femoral nerve and the internal or external iliac artery or vein that lie anterior to the ilium.

Continue to: We hypothesized that there...

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that there would be an optimal angle of entry and maximal safe distance the trocar could advance through the ilium when aspirating. Because male and female pelvic anatomy differs, we also hypothesized that there would be differences in distance and size measurements for males and females. Our results supported our hypothesis that there is an ideal approach angle. The results also showed that the maximum distance the trocar can advance and the width of the PSIS table differ significantly between males and females.

Although pelvic anatomy differs between males and females, there should be an ideal entry angle that would allow maximum advancement into the ilium without perforating the anterior wall, which we defined as the approach angle. In our comparison of 26 MRI scans, we found that the approach angle did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (13 males, 13 females). This allows clinicians to enter the PSIS at roughly 24° medial to the parasagittal line, maximizing the space before puncturing into the anterior pelvis in either males or females.

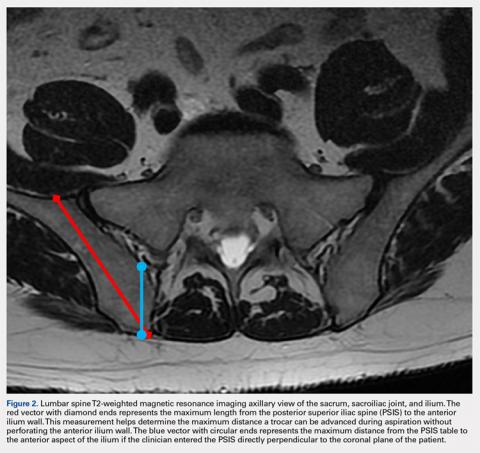

If clinicians were to enter perpendicular to the patient’s PSIS, they would, on average, be able to advance only 3.20 cm before encountering the SI joint. When entering at 24° as we recommend, the average distance increases to 7.14 cm. Although the angle did not differ significantly, there was a significant difference between males and females in the length from the PSIS to the anterior wall, with males having 7.53 cm distance and females 6.74 cm. This is an important measurement because if the anterior ilium wall is punctured, the femoral nerve and the common, internal and external iliac arteries and veins could be damaged, resulting in retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

A fatality in 2001 in the United Kingdom led to a national audit of bone marrow aspiration and biopsies.4-6 Although these procedures were done primarily for patients with cancer, hemorrhagic events were the most frequent and serious events. This audit led to the identification of many risk factors. Bain4-6 conducted reviews of bone marrow aspirations and biopsies in the United Kingdom from 2002 to 2004. Of a total of 53,088 procedures conducted during that time frame, 48 (0.09%) adverse events occurred, with 29 (0.05%) being hemorrhagic events. Although infrequent, hemorrhagic adverse events represent significant morbidity. Reviews such as those conducted by Bain4-6 highlight the importance of a study that helps determine the optimal parameters for aspiration to ensure safety and reliability.

Hernigou and colleagues2,3 conducted studies analyzing different “sectors” in an attempt to develop a safe aspiration technique. They found that obese patients were at higher risk, and some sites of aspiration (sectors 1, 4, 5) had increased risk for perforation and damage to surrounding structures. Their sector 6, which incorporated the entirety of the PSIS table, was considered the safest, most reliable site for trocar introduction.2,3 Hernigou and colleagues,2 in comparing the bone mass of the sectors, also noted that sector 6 has the greatest bone thickness close to the entry point, making it the most favorable site. The PSIS is not just a point; it is more a “table.” The PSIS can be palpated posteriorly, but this is inaccurate and unreliable, particularly in larger individuals. The PSIS table can be identified on ultrasound before introducing the trocar, which is a more reliable method of landmark identification than palpation guidance, just as in ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19

Continue to: If the PSIS is not accurately...

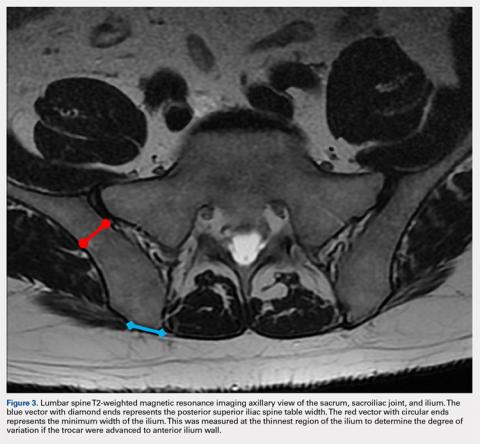

If the PSIS is not accurately identified, penetration laterally will result in entering the ilium wing, where it is quite narrow. We found the distance between the posterior ilium wall and the SI joint to be only 1.10 cm wide (Figure 3); we defined this area as the narrow corridor. Superior and lateral entry could damage the superior cluneal nerves coming over the iliac crest, which are located 6 cm lateral to the SI joint. Inferior and lateral entry 6 cm below the PSIS could reach the greater sciatic foramen, damaging the sacral plexus and superior gluteal artery and vein. If the entry slips above the PSIS over the pelvis, the trocar could enter the retroperitoneal space and damage the femoral nerve and common iliac artery and vein, leading to a retroperitoneal hemorrhage.4-6,20

MSCs are found as perivascular cells and lie in the cortices of bones.21 Following the approach angle and directed line from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall described in this study (Figures 1 and 2), the trocar would pass through the narrow corridor as it advances farther into the ilium. The minimum width of this corridor was measured in this study and, on average, was 1.10 cm wide from cortex to cortex (Figure 3). As the bone marrow is aspirated from this narrow corridor, the clinician is gathering MSCs from both the lateral and medial cortices of the ilium. By aspirating from a greater surface area of the cortices, it is believed that this will increase the total collection of MSCs.

CONCLUSION

Although there are reports in the literature that describe techniques for bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest, the techniques are very general and vague regarding the ideal angles and methods. Studies have attempted to quantify the safest entry sites for aspiration but have not detailed ideal parameters for collection. Blind aspiration from the iliac crest can have serious implications if adverse events occur, and thus there is a need for a safe and reliable method of aspiration from the iliac crest. Ultrasound guidance to identify anatomy, as opposed to palpation guidance, ensures anatomic placement of the trocar while minimizing the risk of aspiration. Based on the measurements gathered in this study, an optimal angle of entry and safe distance of penetration have been identified. Using our data and relevant literature, we developed a technique for a safe, consistent, and reliable method of bone marrow aspiration out of the iliac crest.

1. Chahla J, Mannava S, Cinque ME, Geeslin AG, Codina D, LaPrade RF. Bone marrow aspirate concentrate harvesting and processing technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(2):e441-e445. doi:10.1016/j.eats.2016.10.024.

2. Hernigou J, Alves A, Homma Y, Guissou I, Hernigou P. Anatomy of the ilium for bone marrow aspiration: map of sectors and implication for safe trocar placement. Int Orthop. 2014;38(12):2585-2590. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2353-7.

3. Hernigou J, Picard L, Alves A, Silvera J, Homma Y, Hernigou P. Understanding bone safety zones during bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest: the sector rule. Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2377-2384. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2343-9.

4. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity: review of 2003. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(4):406-408. doi:10.1136/jcp.2004.022178.

5. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity and mortality: 2002 data. Clin Lab Haematol. 2004;26(5):315-318. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2257.2004.00630.x.

6. Bain BJ. Morbidity associated with bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy - a review of UK data for 2004. Haematologica. 2006;91(9):1293-1294.

7. Berkoff DJ, Miller LE, Block JE. Clinical utility of ultrasound guidance for intra-articular knee injections: a review. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:89-95. doi:10.2147/CIA.S29265.

8. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.019.

9. Hirahara AM, Panero AJ. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 3: interventional and procedural uses. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):440-445.

10. Jackson DW, Evans NA, Thomas BM. Accuracy of needle placement into the intra-articular space of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(9):1522-1527.

11. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

12. Panero AJ, Hirahara AM. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 2: the diagnostic evaluation. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(4):233-238.

13. Sethi PM, El Attrache N. Accuracy of intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2006;29(2):149-152.

14. Sibbit WL Jr, Peisajovich A, Michael AA, et al. Does sonographic needle guidance affect the clinical outcome of intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):1892-1902. doi:10.3899/jrheum.090013.

15. Smith J, Brault JS, Rizzo M, Sayeed YA, Finnoff JT. Accuracy of sonographically guided and palpation guided scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint injections. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30(11):1509-1515. doi:10.7863/jum.2011.30.11.1509.

16. Yamakado K. The targeting accuracy of subacromial injection to the shoulder: an arthrographic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):887-891.

17. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament: surgical technique and case report. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):418-422, 460.

18. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous repair of medial patellofemoral ligament: surgical technique and outcomes. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):152-157.

19. Hirahara AM, Mackay G, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided InternalBrace of the medial collateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. Submitted.

20. Jamaludin WFW, Mukari SAM, Wahid SFA. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage associated with bone marrow trephine biopsy. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:489-493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.889274.

21. Bianco P, Cao X, Frenette PS, et al. The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):35-42. doi:10.1038/nm.3028.

ABSTRACT

Use of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow has gained significant popularity. The iliac crest has been determined to be an effective site for harvesting mesenchymal stem cells. Review of the literature reveals that multiple techniques are used to harvest bone marrow aspirate from the iliac crest, but the descriptions are based on the experience of various authors as opposed to studied anatomy. A safe, reliable, and reproducible method for aspiration has yet to be studied and described. We hypothesized that there would be an ideal angle and distance for aspiration that would be the safest, most consistent, and most reliable. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we reviewed 26 total lumbar spine MRI scans (13 males, 13 females) and found that an angle of 24° should be used when entering the most medial aspect of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and that this angle did not differ between the sexes. The distance that the trocar can advance after entry before hitting the anterior ilium wall varied significantly between males and females, being 7.53 cm in males and 6.74 cm in females. In addition, the size of the PSIS table was significantly different between males and females (1.20 cm and 0.96 cm, respectively). No other significant differences in the measurements gathered were found. Using the data gleaned from this study, we developed an aspiration technique. This method uses ultrasound to determine the location of the PSIS and the entry point on the PSIS. This contrasts with most techniques that use landmark palpation, which is known to be unreliable and inaccurate. The described technique for aspiration from the PSIS is safe, reliable, reproducible, and substantiated by data.

The iliac crest is an effective site for harvesting bone marrow stem cells. It allows for easy access and is superficial in most individuals, allowing for a relatively quick and simple procedure. Use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for treatment of orthopedic injuries has grown recently. Whereas overall use has increased, review of the literature reveals very few techniques for iliac crest aspiration,1 but these are not based on anatomic relationships or studies. Hernigou and colleagues2,3 attempted to quantitatively evaluate potential “sectors” allowing for safe aspiration using cadaver and computed tomographic reconstruction imaging. We used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to analyze aspiration parameters. Owing to the ilium’s anatomy, improper positioning or aspiration technique during aspiration can result in serious injury.2,4-6 We hypothesized that there is an ideal angle and positioning for bone marrow aspiration from the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) that is safe, consistent, and reproducible. Although most aspiration techniques use landmark palpation, this is unreliable and inaccurate, especially when compared with ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19 We describe our technique using ultrasound to visualize patient anatomy and accurately determine anatomic entry with the trocar.

METHODS

MRI scans of 26 patients (13 males, 13 females) were reviewed to determine average angles and distances. Axial T2-weighted views of the lumbar spine were used in all analyses. The sacroiliac (SI) joint angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector through the midline of the pelvis and the vector that is parallel to the SI joint. The approach angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector of the most medial aspect of the PSIS through the ilium to the anterior wall and the vector through the midline of the pelvis (Figure 1).

Continue to: For the 13 males, the mean SI joint...

RESULTS

The results are reported in the Table.

Table. Measurements of Patients Taken on Axial T2-Weighted Views of Lumbosacral MRI Scansa

Patient | SI Joint Angle (°) | Approach Angle (°) | PSIS Table Width (cm) | PSIS to Anterior Ilium Wall (cm) | Perpendicular Distance PSIS to Anterior Joint (cm) | Post Ilium Wall to SI Joint Width (cm) |

Males | ||||||

1 | 28.80 | 19.50 | 1.24 | 8.80 | 4.16 | 1.52 |

2 | 31.80 | 27.60 | 1.70 | 7.89 | 3.49 | 1.02 |

3 | 33.70 | 27.70 | 1.12 | 8.14 | 3.15 | 1.28 |

4 | 23.70 | 26.40 | 0.95 | 6.66 | 3.22 | 0.65 |

5 | 35.90 | 28.40 | 0.84 | 7.60 | 2.57 | 0.95 |

6 | 33.80 | 29.30 | 1.20 | 7.73 | 2.34 | 0.90 |

7 | 30.30 | 21.20 | 1.36 | 8.44 | 3.95 | 1.18 |

8 | 34.50 | 20.40 | 1.53 | 7.08 | 3.98 | 1.56 |

9 | 28.70 | 24.00 | 1.34 | 8.19 | 3.51 | 1.31 |

10 | 22.40 | 20.10 | 1.37 | 7.30 | 3.87 | 1.28 |

11 | 33.60 | 20.80 | 0.88 | 6.43 | 3.26 | 0.94 |

12 | 48.50 | 31.00 | 1.15 | 6.69 | 2.97 | 1.38 |

13 | 20.20 | 20.90 | 0.94 | 6.95 | 3.79 | 1.05 |

Averages | 31.22 | 24.41 | 1.20 | 7.53 | 3.40 | 1.16 |

Standard Deviation | 7.18 | 4.11 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.26 |

Females | ||||||

14 | 22.80 | 23.20 | 1.54 | 7.21 | 3.45 | 1.39 |

15 | 33.30 | 21.40 | 1.09 | 7.26 | 3.57 | 0.98 |

16 | 19.70 | 15.60 | 0.78 | 8.32 | 3.76 | 0.86 |

17 | 17.50 | 15.60 | 0.61 | 7.57 | 3.37 | 1.03 |

18 | 48.20 | 26.60 | 0.94 | 6.62 | 3.16 | 0.71 |

19 | 38.20 | 28.30 | 0.90 | 6.32 | 2.23 | 0.91 |

20 | 44.50 | 31.70 | 0.99 | 6.19 | 3.06 | 0.76 |

21 | 24.10 | 18.00 | 0.92 | 6.99 | 3.23 | 0.71 |

22 | 17.20 | 14.80 | 0.81 | 6.00 | 2.81 | 1.13 |

23 | 42.00 | 38.50 | 1.00 | 5.33 | 2.47 | 1.42 |

24 | 32.00 | 25.50 | 0.98 | 6.01 | 2.79 | 1.21 |

25 | 24.70 | 24.80 | 0.87 | 6.09 | 2.79 | 1.02 |

26 | 19.80 | 22.30 | 1.04 | 7.71 | 2.37 | 1.36 |

Averages | 29.54 | 23.56 | 0.96 | 6.74 | 3.00 | 1.04 |

Standard Deviation | 10.84 | 6.88 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

All patients Averages | 30.38 | 23.98 | 1.08 | 7.14 | 3.20 | 1.10 |

Standard Deviation | 9.05 | 5.57 | 0.26 | 0.88 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

aStatistical significance is denoted as P < .02.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PSIS, posterior iliac spine; SI, sacroiliac.

For the 13 males, the mean SI joint angle was 31.22° ± 7.18° (range, 20.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 24.41° ± 4.11° (range, 19.50° to 31.00°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.20 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.84 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.53 cm ± 0.75 cm (range, 6.43 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.40 cm ± 0.56 cm (range, 2.34 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.16 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

For the 13 females, the mean SI joint angle was 29.54° ± 10.84° (range, 17.20° to 48.20°). The mean approach angle was 23.56° ± 6.88° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 0.96 cm ± 0.21 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.54 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 6.74 cm ± 0.85 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.32 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.00 cm ± 0.48 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 3.76 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.04 cm ± 0.25 cm (range, 0.71 cm to 1.42 cm).

For the 26 total patients, the mean SI joint angle was 30.38° ± 9.05° (range, 17.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 23.98° ± 5.57° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.08 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.14 cm ± 0.88 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.20 cm ± 0.55 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.10 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

There was a statistically significant difference between the male and female groups for the maximum distance the trocar can be advanced from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall (P < .02), and a statistically significant difference for the PSIS table width (P < .02). There were no significant differences between the male and female groups for the approach angle, the SI joint angle, the perpendicular distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium, and the minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint.

Continue to: The patient is brought to the procedure...

TECHNIQUE: ILIAC CREST (PSIS) BONE MARROW ASPIRATION

The patient is brought to the procedure room and placed in a prone position. The donor site is prepared and draped in the usual sterile manner. Ultrasound is used to identify the median sacral crest in a short-axis view. The probe is then moved laterally to identify the PSIS (Figures 4A, 4B).

The crosshairs on the ultrasound probe are used to mark the center lines of each plane. The central point marks the location of the PSIS. Alternatively, an in-plane technique can be used to place a spinal needle on the exact entry point on the PSIS. Once the PSIS and entry point are identified, the site is blocked with 10 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine.

Prior to introduction of the trocar, all instrumentation is primed with heparin and syringes are prepped with anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution, solution A. A stab incision is made at the site. The trocar is placed at the entry point, which should be centered in a superior-inferior plane and at the most medial point of the PSIS. Starting with the trocar vertical, the trocar is angled laterally 24° by dropping the hand medially toward the midline. No angulation cephalad or caudad is necessary, but cephalad must be avoided so as not to skive superiorly. This angle, which is recommended for both males and females, allows for the greatest distance the trocar can travel in bone before hitting the anterior ilium wall. A standard deviation of 5.57° is present, which should be considered. Steady pressure should be applied with a slight twisting motion on the PSIS. If advancement of the trocar is too difficult, a mallet or drill can be used to assist in penetration.

With the trocar advanced into the bone 1 cm, the trocar needle is removed while the cannula remains in place. The syringe is attached to the top of the cannula. The syringe plunger is pulled back to aspirate 20 mL of bone marrow. The cannula and syringe assembly are advanced 2 cm farther into the bone to allow for aspiration of a new location within the bone marrow cavity, and 20 mL of bone marrow are again aspirated. This is done a final time, advancing the trocar another 2 cm and aspirating a final 20 mL of bone marrow. The entire process should yield roughly 60 mL of bone marrow from one side. If desired, the same process can be repeated for the contralateral PSIS to yield a total of 120 mL of bone marrow from the 2 sites.

Based on our data, the average distance to the anterior ilium wall was 7 cm, but the shortest distance noted in this study was 5 cm. On the basis of the data presented, this technique allows for safe advancement based on even the shortest measured distance, without fear of puncturing the anterior ilium wall. Perforation could damage the femoral nerve and the internal or external iliac artery or vein that lie anterior to the ilium.

Continue to: We hypothesized that there...

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that there would be an optimal angle of entry and maximal safe distance the trocar could advance through the ilium when aspirating. Because male and female pelvic anatomy differs, we also hypothesized that there would be differences in distance and size measurements for males and females. Our results supported our hypothesis that there is an ideal approach angle. The results also showed that the maximum distance the trocar can advance and the width of the PSIS table differ significantly between males and females.

Although pelvic anatomy differs between males and females, there should be an ideal entry angle that would allow maximum advancement into the ilium without perforating the anterior wall, which we defined as the approach angle. In our comparison of 26 MRI scans, we found that the approach angle did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (13 males, 13 females). This allows clinicians to enter the PSIS at roughly 24° medial to the parasagittal line, maximizing the space before puncturing into the anterior pelvis in either males or females.

If clinicians were to enter perpendicular to the patient’s PSIS, they would, on average, be able to advance only 3.20 cm before encountering the SI joint. When entering at 24° as we recommend, the average distance increases to 7.14 cm. Although the angle did not differ significantly, there was a significant difference between males and females in the length from the PSIS to the anterior wall, with males having 7.53 cm distance and females 6.74 cm. This is an important measurement because if the anterior ilium wall is punctured, the femoral nerve and the common, internal and external iliac arteries and veins could be damaged, resulting in retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

A fatality in 2001 in the United Kingdom led to a national audit of bone marrow aspiration and biopsies.4-6 Although these procedures were done primarily for patients with cancer, hemorrhagic events were the most frequent and serious events. This audit led to the identification of many risk factors. Bain4-6 conducted reviews of bone marrow aspirations and biopsies in the United Kingdom from 2002 to 2004. Of a total of 53,088 procedures conducted during that time frame, 48 (0.09%) adverse events occurred, with 29 (0.05%) being hemorrhagic events. Although infrequent, hemorrhagic adverse events represent significant morbidity. Reviews such as those conducted by Bain4-6 highlight the importance of a study that helps determine the optimal parameters for aspiration to ensure safety and reliability.

Hernigou and colleagues2,3 conducted studies analyzing different “sectors” in an attempt to develop a safe aspiration technique. They found that obese patients were at higher risk, and some sites of aspiration (sectors 1, 4, 5) had increased risk for perforation and damage to surrounding structures. Their sector 6, which incorporated the entirety of the PSIS table, was considered the safest, most reliable site for trocar introduction.2,3 Hernigou and colleagues,2 in comparing the bone mass of the sectors, also noted that sector 6 has the greatest bone thickness close to the entry point, making it the most favorable site. The PSIS is not just a point; it is more a “table.” The PSIS can be palpated posteriorly, but this is inaccurate and unreliable, particularly in larger individuals. The PSIS table can be identified on ultrasound before introducing the trocar, which is a more reliable method of landmark identification than palpation guidance, just as in ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19

Continue to: If the PSIS is not accurately...

If the PSIS is not accurately identified, penetration laterally will result in entering the ilium wing, where it is quite narrow. We found the distance between the posterior ilium wall and the SI joint to be only 1.10 cm wide (Figure 3); we defined this area as the narrow corridor. Superior and lateral entry could damage the superior cluneal nerves coming over the iliac crest, which are located 6 cm lateral to the SI joint. Inferior and lateral entry 6 cm below the PSIS could reach the greater sciatic foramen, damaging the sacral plexus and superior gluteal artery and vein. If the entry slips above the PSIS over the pelvis, the trocar could enter the retroperitoneal space and damage the femoral nerve and common iliac artery and vein, leading to a retroperitoneal hemorrhage.4-6,20

MSCs are found as perivascular cells and lie in the cortices of bones.21 Following the approach angle and directed line from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall described in this study (Figures 1 and 2), the trocar would pass through the narrow corridor as it advances farther into the ilium. The minimum width of this corridor was measured in this study and, on average, was 1.10 cm wide from cortex to cortex (Figure 3). As the bone marrow is aspirated from this narrow corridor, the clinician is gathering MSCs from both the lateral and medial cortices of the ilium. By aspirating from a greater surface area of the cortices, it is believed that this will increase the total collection of MSCs.

CONCLUSION

Although there are reports in the literature that describe techniques for bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest, the techniques are very general and vague regarding the ideal angles and methods. Studies have attempted to quantify the safest entry sites for aspiration but have not detailed ideal parameters for collection. Blind aspiration from the iliac crest can have serious implications if adverse events occur, and thus there is a need for a safe and reliable method of aspiration from the iliac crest. Ultrasound guidance to identify anatomy, as opposed to palpation guidance, ensures anatomic placement of the trocar while minimizing the risk of aspiration. Based on the measurements gathered in this study, an optimal angle of entry and safe distance of penetration have been identified. Using our data and relevant literature, we developed a technique for a safe, consistent, and reliable method of bone marrow aspiration out of the iliac crest.

ABSTRACT

Use of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow has gained significant popularity. The iliac crest has been determined to be an effective site for harvesting mesenchymal stem cells. Review of the literature reveals that multiple techniques are used to harvest bone marrow aspirate from the iliac crest, but the descriptions are based on the experience of various authors as opposed to studied anatomy. A safe, reliable, and reproducible method for aspiration has yet to be studied and described. We hypothesized that there would be an ideal angle and distance for aspiration that would be the safest, most consistent, and most reliable. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we reviewed 26 total lumbar spine MRI scans (13 males, 13 females) and found that an angle of 24° should be used when entering the most medial aspect of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and that this angle did not differ between the sexes. The distance that the trocar can advance after entry before hitting the anterior ilium wall varied significantly between males and females, being 7.53 cm in males and 6.74 cm in females. In addition, the size of the PSIS table was significantly different between males and females (1.20 cm and 0.96 cm, respectively). No other significant differences in the measurements gathered were found. Using the data gleaned from this study, we developed an aspiration technique. This method uses ultrasound to determine the location of the PSIS and the entry point on the PSIS. This contrasts with most techniques that use landmark palpation, which is known to be unreliable and inaccurate. The described technique for aspiration from the PSIS is safe, reliable, reproducible, and substantiated by data.

The iliac crest is an effective site for harvesting bone marrow stem cells. It allows for easy access and is superficial in most individuals, allowing for a relatively quick and simple procedure. Use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for treatment of orthopedic injuries has grown recently. Whereas overall use has increased, review of the literature reveals very few techniques for iliac crest aspiration,1 but these are not based on anatomic relationships or studies. Hernigou and colleagues2,3 attempted to quantitatively evaluate potential “sectors” allowing for safe aspiration using cadaver and computed tomographic reconstruction imaging. We used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to analyze aspiration parameters. Owing to the ilium’s anatomy, improper positioning or aspiration technique during aspiration can result in serious injury.2,4-6 We hypothesized that there is an ideal angle and positioning for bone marrow aspiration from the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) that is safe, consistent, and reproducible. Although most aspiration techniques use landmark palpation, this is unreliable and inaccurate, especially when compared with ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19 We describe our technique using ultrasound to visualize patient anatomy and accurately determine anatomic entry with the trocar.

METHODS

MRI scans of 26 patients (13 males, 13 females) were reviewed to determine average angles and distances. Axial T2-weighted views of the lumbar spine were used in all analyses. The sacroiliac (SI) joint angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector through the midline of the pelvis and the vector that is parallel to the SI joint. The approach angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector of the most medial aspect of the PSIS through the ilium to the anterior wall and the vector through the midline of the pelvis (Figure 1).

Continue to: For the 13 males, the mean SI joint...

RESULTS

The results are reported in the Table.

Table. Measurements of Patients Taken on Axial T2-Weighted Views of Lumbosacral MRI Scansa

Patient | SI Joint Angle (°) | Approach Angle (°) | PSIS Table Width (cm) | PSIS to Anterior Ilium Wall (cm) | Perpendicular Distance PSIS to Anterior Joint (cm) | Post Ilium Wall to SI Joint Width (cm) |

Males | ||||||

1 | 28.80 | 19.50 | 1.24 | 8.80 | 4.16 | 1.52 |

2 | 31.80 | 27.60 | 1.70 | 7.89 | 3.49 | 1.02 |

3 | 33.70 | 27.70 | 1.12 | 8.14 | 3.15 | 1.28 |

4 | 23.70 | 26.40 | 0.95 | 6.66 | 3.22 | 0.65 |

5 | 35.90 | 28.40 | 0.84 | 7.60 | 2.57 | 0.95 |

6 | 33.80 | 29.30 | 1.20 | 7.73 | 2.34 | 0.90 |

7 | 30.30 | 21.20 | 1.36 | 8.44 | 3.95 | 1.18 |

8 | 34.50 | 20.40 | 1.53 | 7.08 | 3.98 | 1.56 |

9 | 28.70 | 24.00 | 1.34 | 8.19 | 3.51 | 1.31 |

10 | 22.40 | 20.10 | 1.37 | 7.30 | 3.87 | 1.28 |

11 | 33.60 | 20.80 | 0.88 | 6.43 | 3.26 | 0.94 |

12 | 48.50 | 31.00 | 1.15 | 6.69 | 2.97 | 1.38 |

13 | 20.20 | 20.90 | 0.94 | 6.95 | 3.79 | 1.05 |

Averages | 31.22 | 24.41 | 1.20 | 7.53 | 3.40 | 1.16 |

Standard Deviation | 7.18 | 4.11 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.26 |

Females | ||||||

14 | 22.80 | 23.20 | 1.54 | 7.21 | 3.45 | 1.39 |

15 | 33.30 | 21.40 | 1.09 | 7.26 | 3.57 | 0.98 |

16 | 19.70 | 15.60 | 0.78 | 8.32 | 3.76 | 0.86 |

17 | 17.50 | 15.60 | 0.61 | 7.57 | 3.37 | 1.03 |

18 | 48.20 | 26.60 | 0.94 | 6.62 | 3.16 | 0.71 |

19 | 38.20 | 28.30 | 0.90 | 6.32 | 2.23 | 0.91 |

20 | 44.50 | 31.70 | 0.99 | 6.19 | 3.06 | 0.76 |

21 | 24.10 | 18.00 | 0.92 | 6.99 | 3.23 | 0.71 |

22 | 17.20 | 14.80 | 0.81 | 6.00 | 2.81 | 1.13 |

23 | 42.00 | 38.50 | 1.00 | 5.33 | 2.47 | 1.42 |

24 | 32.00 | 25.50 | 0.98 | 6.01 | 2.79 | 1.21 |

25 | 24.70 | 24.80 | 0.87 | 6.09 | 2.79 | 1.02 |

26 | 19.80 | 22.30 | 1.04 | 7.71 | 2.37 | 1.36 |

Averages | 29.54 | 23.56 | 0.96 | 6.74 | 3.00 | 1.04 |

Standard Deviation | 10.84 | 6.88 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

All patients Averages | 30.38 | 23.98 | 1.08 | 7.14 | 3.20 | 1.10 |

Standard Deviation | 9.05 | 5.57 | 0.26 | 0.88 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

aStatistical significance is denoted as P < .02.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PSIS, posterior iliac spine; SI, sacroiliac.

For the 13 males, the mean SI joint angle was 31.22° ± 7.18° (range, 20.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 24.41° ± 4.11° (range, 19.50° to 31.00°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.20 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.84 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.53 cm ± 0.75 cm (range, 6.43 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.40 cm ± 0.56 cm (range, 2.34 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.16 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

For the 13 females, the mean SI joint angle was 29.54° ± 10.84° (range, 17.20° to 48.20°). The mean approach angle was 23.56° ± 6.88° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 0.96 cm ± 0.21 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.54 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 6.74 cm ± 0.85 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.32 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.00 cm ± 0.48 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 3.76 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.04 cm ± 0.25 cm (range, 0.71 cm to 1.42 cm).

For the 26 total patients, the mean SI joint angle was 30.38° ± 9.05° (range, 17.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 23.98° ± 5.57° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.08 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.14 cm ± 0.88 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.20 cm ± 0.55 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.10 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

There was a statistically significant difference between the male and female groups for the maximum distance the trocar can be advanced from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall (P < .02), and a statistically significant difference for the PSIS table width (P < .02). There were no significant differences between the male and female groups for the approach angle, the SI joint angle, the perpendicular distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium, and the minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint.

Continue to: The patient is brought to the procedure...

TECHNIQUE: ILIAC CREST (PSIS) BONE MARROW ASPIRATION

The patient is brought to the procedure room and placed in a prone position. The donor site is prepared and draped in the usual sterile manner. Ultrasound is used to identify the median sacral crest in a short-axis view. The probe is then moved laterally to identify the PSIS (Figures 4A, 4B).

The crosshairs on the ultrasound probe are used to mark the center lines of each plane. The central point marks the location of the PSIS. Alternatively, an in-plane technique can be used to place a spinal needle on the exact entry point on the PSIS. Once the PSIS and entry point are identified, the site is blocked with 10 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine.

Prior to introduction of the trocar, all instrumentation is primed with heparin and syringes are prepped with anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution, solution A. A stab incision is made at the site. The trocar is placed at the entry point, which should be centered in a superior-inferior plane and at the most medial point of the PSIS. Starting with the trocar vertical, the trocar is angled laterally 24° by dropping the hand medially toward the midline. No angulation cephalad or caudad is necessary, but cephalad must be avoided so as not to skive superiorly. This angle, which is recommended for both males and females, allows for the greatest distance the trocar can travel in bone before hitting the anterior ilium wall. A standard deviation of 5.57° is present, which should be considered. Steady pressure should be applied with a slight twisting motion on the PSIS. If advancement of the trocar is too difficult, a mallet or drill can be used to assist in penetration.

With the trocar advanced into the bone 1 cm, the trocar needle is removed while the cannula remains in place. The syringe is attached to the top of the cannula. The syringe plunger is pulled back to aspirate 20 mL of bone marrow. The cannula and syringe assembly are advanced 2 cm farther into the bone to allow for aspiration of a new location within the bone marrow cavity, and 20 mL of bone marrow are again aspirated. This is done a final time, advancing the trocar another 2 cm and aspirating a final 20 mL of bone marrow. The entire process should yield roughly 60 mL of bone marrow from one side. If desired, the same process can be repeated for the contralateral PSIS to yield a total of 120 mL of bone marrow from the 2 sites.

Based on our data, the average distance to the anterior ilium wall was 7 cm, but the shortest distance noted in this study was 5 cm. On the basis of the data presented, this technique allows for safe advancement based on even the shortest measured distance, without fear of puncturing the anterior ilium wall. Perforation could damage the femoral nerve and the internal or external iliac artery or vein that lie anterior to the ilium.

Continue to: We hypothesized that there...

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that there would be an optimal angle of entry and maximal safe distance the trocar could advance through the ilium when aspirating. Because male and female pelvic anatomy differs, we also hypothesized that there would be differences in distance and size measurements for males and females. Our results supported our hypothesis that there is an ideal approach angle. The results also showed that the maximum distance the trocar can advance and the width of the PSIS table differ significantly between males and females.

Although pelvic anatomy differs between males and females, there should be an ideal entry angle that would allow maximum advancement into the ilium without perforating the anterior wall, which we defined as the approach angle. In our comparison of 26 MRI scans, we found that the approach angle did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (13 males, 13 females). This allows clinicians to enter the PSIS at roughly 24° medial to the parasagittal line, maximizing the space before puncturing into the anterior pelvis in either males or females.

If clinicians were to enter perpendicular to the patient’s PSIS, they would, on average, be able to advance only 3.20 cm before encountering the SI joint. When entering at 24° as we recommend, the average distance increases to 7.14 cm. Although the angle did not differ significantly, there was a significant difference between males and females in the length from the PSIS to the anterior wall, with males having 7.53 cm distance and females 6.74 cm. This is an important measurement because if the anterior ilium wall is punctured, the femoral nerve and the common, internal and external iliac arteries and veins could be damaged, resulting in retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

A fatality in 2001 in the United Kingdom led to a national audit of bone marrow aspiration and biopsies.4-6 Although these procedures were done primarily for patients with cancer, hemorrhagic events were the most frequent and serious events. This audit led to the identification of many risk factors. Bain4-6 conducted reviews of bone marrow aspirations and biopsies in the United Kingdom from 2002 to 2004. Of a total of 53,088 procedures conducted during that time frame, 48 (0.09%) adverse events occurred, with 29 (0.05%) being hemorrhagic events. Although infrequent, hemorrhagic adverse events represent significant morbidity. Reviews such as those conducted by Bain4-6 highlight the importance of a study that helps determine the optimal parameters for aspiration to ensure safety and reliability.

Hernigou and colleagues2,3 conducted studies analyzing different “sectors” in an attempt to develop a safe aspiration technique. They found that obese patients were at higher risk, and some sites of aspiration (sectors 1, 4, 5) had increased risk for perforation and damage to surrounding structures. Their sector 6, which incorporated the entirety of the PSIS table, was considered the safest, most reliable site for trocar introduction.2,3 Hernigou and colleagues,2 in comparing the bone mass of the sectors, also noted that sector 6 has the greatest bone thickness close to the entry point, making it the most favorable site. The PSIS is not just a point; it is more a “table.” The PSIS can be palpated posteriorly, but this is inaccurate and unreliable, particularly in larger individuals. The PSIS table can be identified on ultrasound before introducing the trocar, which is a more reliable method of landmark identification than palpation guidance, just as in ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19

Continue to: If the PSIS is not accurately...

If the PSIS is not accurately identified, penetration laterally will result in entering the ilium wing, where it is quite narrow. We found the distance between the posterior ilium wall and the SI joint to be only 1.10 cm wide (Figure 3); we defined this area as the narrow corridor. Superior and lateral entry could damage the superior cluneal nerves coming over the iliac crest, which are located 6 cm lateral to the SI joint. Inferior and lateral entry 6 cm below the PSIS could reach the greater sciatic foramen, damaging the sacral plexus and superior gluteal artery and vein. If the entry slips above the PSIS over the pelvis, the trocar could enter the retroperitoneal space and damage the femoral nerve and common iliac artery and vein, leading to a retroperitoneal hemorrhage.4-6,20

MSCs are found as perivascular cells and lie in the cortices of bones.21 Following the approach angle and directed line from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall described in this study (Figures 1 and 2), the trocar would pass through the narrow corridor as it advances farther into the ilium. The minimum width of this corridor was measured in this study and, on average, was 1.10 cm wide from cortex to cortex (Figure 3). As the bone marrow is aspirated from this narrow corridor, the clinician is gathering MSCs from both the lateral and medial cortices of the ilium. By aspirating from a greater surface area of the cortices, it is believed that this will increase the total collection of MSCs.

CONCLUSION

Although there are reports in the literature that describe techniques for bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest, the techniques are very general and vague regarding the ideal angles and methods. Studies have attempted to quantify the safest entry sites for aspiration but have not detailed ideal parameters for collection. Blind aspiration from the iliac crest can have serious implications if adverse events occur, and thus there is a need for a safe and reliable method of aspiration from the iliac crest. Ultrasound guidance to identify anatomy, as opposed to palpation guidance, ensures anatomic placement of the trocar while minimizing the risk of aspiration. Based on the measurements gathered in this study, an optimal angle of entry and safe distance of penetration have been identified. Using our data and relevant literature, we developed a technique for a safe, consistent, and reliable method of bone marrow aspiration out of the iliac crest.

1. Chahla J, Mannava S, Cinque ME, Geeslin AG, Codina D, LaPrade RF. Bone marrow aspirate concentrate harvesting and processing technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(2):e441-e445. doi:10.1016/j.eats.2016.10.024.

2. Hernigou J, Alves A, Homma Y, Guissou I, Hernigou P. Anatomy of the ilium for bone marrow aspiration: map of sectors and implication for safe trocar placement. Int Orthop. 2014;38(12):2585-2590. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2353-7.

3. Hernigou J, Picard L, Alves A, Silvera J, Homma Y, Hernigou P. Understanding bone safety zones during bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest: the sector rule. Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2377-2384. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2343-9.

4. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity: review of 2003. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(4):406-408. doi:10.1136/jcp.2004.022178.

5. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity and mortality: 2002 data. Clin Lab Haematol. 2004;26(5):315-318. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2257.2004.00630.x.

6. Bain BJ. Morbidity associated with bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy - a review of UK data for 2004. Haematologica. 2006;91(9):1293-1294.

7. Berkoff DJ, Miller LE, Block JE. Clinical utility of ultrasound guidance for intra-articular knee injections: a review. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:89-95. doi:10.2147/CIA.S29265.

8. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.019.

9. Hirahara AM, Panero AJ. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 3: interventional and procedural uses. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):440-445.

10. Jackson DW, Evans NA, Thomas BM. Accuracy of needle placement into the intra-articular space of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(9):1522-1527.

11. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

12. Panero AJ, Hirahara AM. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 2: the diagnostic evaluation. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(4):233-238.

13. Sethi PM, El Attrache N. Accuracy of intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2006;29(2):149-152.

14. Sibbit WL Jr, Peisajovich A, Michael AA, et al. Does sonographic needle guidance affect the clinical outcome of intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):1892-1902. doi:10.3899/jrheum.090013.

15. Smith J, Brault JS, Rizzo M, Sayeed YA, Finnoff JT. Accuracy of sonographically guided and palpation guided scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint injections. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30(11):1509-1515. doi:10.7863/jum.2011.30.11.1509.

16. Yamakado K. The targeting accuracy of subacromial injection to the shoulder: an arthrographic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):887-891.

17. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament: surgical technique and case report. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):418-422, 460.

18. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous repair of medial patellofemoral ligament: surgical technique and outcomes. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):152-157.

19. Hirahara AM, Mackay G, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided InternalBrace of the medial collateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. Submitted.