User login

University of California, San Diego (UCSD): Critical Care Summer Session

Expert shares tips for assessing pain in the ICU

SAN DIEGO – Pain management in critically ill patients is vital because most of them experience pain during their ICU stay, both at rest and during activity, Chris Pasero, R.N., said at the University of California, San Diego Critical Care Summer Session.

Research has demonstrated that 13- to 18-year-old patients in the ICU rate wound care as the most painful, but all other patient populations rate simple turning as the most painful procedure in the ICU, said Ms. Pasero, a pain management educator and clinical consultant based in El Dorado Hills, Calif. "It’s no surprise that patients in the ICU remember their pain, and they identify it as a major source of stress and anxiety," she said. "Pain is often undertreated, and I think it’s because we have so many barriers in the ICU."

Barriers to effective pain management in critically ill patients include comorbidities and coadministered drugs that affect the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of analgesics. Conflicting goals of care also factor into play. "When we are managing pain, many of the drugs we use sedate," said Ms. Pasero, who cofounded the American Society for Pain Management Nursing. "That may conflict with what you’re trying to accomplish, such as the need to control pain in the presence of respiratory compromise. One of the biggest problems is that many of your patients are unable to report their own pain and a failure to properly assess patients for pain. Our failure to properly assess those who are challenging to assess is a major cause of their unrelieved pain and unnecessary suffering."

She described a framework for assessment known as the Hierarchy of Pain Measures. This includes obtaining a self-report of pain, behaviors, physiologic measures, and the presence of a pathologic condition or procedure that causes pain. "Many institutions are inserting this hierarchy into their policies and procedures," she said. "At the top of the hierarchy is a self-report of pain. Always attempt to obtain this. It will give us much of what you need."

Numerical pain rating scales can help patients tell clinicians their level of discomfort. The most common self-report pain intensity tools are the 0-10 numerical scale and two faces scales, the Faces Pain Scale – Revised tool developed by the International Association for the Study of Pain, and the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale.

Another self-report tool used in ICUs is the Iowa Pain Thermometer (Pain Med. 2007;8:585-600). This measure was originally developed for cognitively impaired elderly, but it is useful for assessing pain in all patients who have limited ability to express themselves, Ms. Pasero said.

She emphasized the importance of being sensitive to cultural differences when assessing for pain. "Folks who do not speak the language of the person caring for them are at very high risk for undertreated pain," she said. "We need to be careful about using family members to do our translation. Studies show that family members from some cultures may hesitate to discuss pain. Get as close as you can to the patient’s own report of pain."

Certain patient behaviors are good indicators of pain, such as frowns, grimaces, tears, guarding the site of pain, pulling at tubes, seeking attention, resisting passive movement, being combative, being intolerant of ventilators, and being confused. "Physiologic measures such as increased heart rate and blood pressure are considered very poor indicators of pain," noted Ms. Pasero, who is coauthor along with Margo McCaffery, R.N., of "Pain Assessment and Pharmacologic Management." (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2011). "There are multiple factors that influence vital signs. You give a lot of drugs to keep vital signs stable, so to expect a patient to fight against that to show you that they have pain with an elevated heart rate or elevated blood pressure is not a good idea. However, abnormalities or changes in vital signs should serve as a trigger to perform a good pain assessment."

She recommends using reliable and valid behavioral pain assessment tool such as the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool or the Behavioral Pain Scale in those who cannot report pain. "In unresponsive patients who cannot demonstrate behaviors and have underlying pathology or conditions thought to be painful, such as surgery, trauma, or mechanical ventilation, we need to assume they have pain and do the best we can to manage it with the administration of recommended doses of analgesics," she said. "Also assume pain is present in patients undergoing painful activities or procedures such as turning, suctioning, or wound care. It’s important to document the underlying pathology or activity assumed to be painful."

Ms. Pasero said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to make.

SAN DIEGO – Pain management in critically ill patients is vital because most of them experience pain during their ICU stay, both at rest and during activity, Chris Pasero, R.N., said at the University of California, San Diego Critical Care Summer Session.

Research has demonstrated that 13- to 18-year-old patients in the ICU rate wound care as the most painful, but all other patient populations rate simple turning as the most painful procedure in the ICU, said Ms. Pasero, a pain management educator and clinical consultant based in El Dorado Hills, Calif. "It’s no surprise that patients in the ICU remember their pain, and they identify it as a major source of stress and anxiety," she said. "Pain is often undertreated, and I think it’s because we have so many barriers in the ICU."

Barriers to effective pain management in critically ill patients include comorbidities and coadministered drugs that affect the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of analgesics. Conflicting goals of care also factor into play. "When we are managing pain, many of the drugs we use sedate," said Ms. Pasero, who cofounded the American Society for Pain Management Nursing. "That may conflict with what you’re trying to accomplish, such as the need to control pain in the presence of respiratory compromise. One of the biggest problems is that many of your patients are unable to report their own pain and a failure to properly assess patients for pain. Our failure to properly assess those who are challenging to assess is a major cause of their unrelieved pain and unnecessary suffering."

She described a framework for assessment known as the Hierarchy of Pain Measures. This includes obtaining a self-report of pain, behaviors, physiologic measures, and the presence of a pathologic condition or procedure that causes pain. "Many institutions are inserting this hierarchy into their policies and procedures," she said. "At the top of the hierarchy is a self-report of pain. Always attempt to obtain this. It will give us much of what you need."

Numerical pain rating scales can help patients tell clinicians their level of discomfort. The most common self-report pain intensity tools are the 0-10 numerical scale and two faces scales, the Faces Pain Scale – Revised tool developed by the International Association for the Study of Pain, and the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale.

Another self-report tool used in ICUs is the Iowa Pain Thermometer (Pain Med. 2007;8:585-600). This measure was originally developed for cognitively impaired elderly, but it is useful for assessing pain in all patients who have limited ability to express themselves, Ms. Pasero said.

She emphasized the importance of being sensitive to cultural differences when assessing for pain. "Folks who do not speak the language of the person caring for them are at very high risk for undertreated pain," she said. "We need to be careful about using family members to do our translation. Studies show that family members from some cultures may hesitate to discuss pain. Get as close as you can to the patient’s own report of pain."

Certain patient behaviors are good indicators of pain, such as frowns, grimaces, tears, guarding the site of pain, pulling at tubes, seeking attention, resisting passive movement, being combative, being intolerant of ventilators, and being confused. "Physiologic measures such as increased heart rate and blood pressure are considered very poor indicators of pain," noted Ms. Pasero, who is coauthor along with Margo McCaffery, R.N., of "Pain Assessment and Pharmacologic Management." (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2011). "There are multiple factors that influence vital signs. You give a lot of drugs to keep vital signs stable, so to expect a patient to fight against that to show you that they have pain with an elevated heart rate or elevated blood pressure is not a good idea. However, abnormalities or changes in vital signs should serve as a trigger to perform a good pain assessment."

She recommends using reliable and valid behavioral pain assessment tool such as the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool or the Behavioral Pain Scale in those who cannot report pain. "In unresponsive patients who cannot demonstrate behaviors and have underlying pathology or conditions thought to be painful, such as surgery, trauma, or mechanical ventilation, we need to assume they have pain and do the best we can to manage it with the administration of recommended doses of analgesics," she said. "Also assume pain is present in patients undergoing painful activities or procedures such as turning, suctioning, or wound care. It’s important to document the underlying pathology or activity assumed to be painful."

Ms. Pasero said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to make.

SAN DIEGO – Pain management in critically ill patients is vital because most of them experience pain during their ICU stay, both at rest and during activity, Chris Pasero, R.N., said at the University of California, San Diego Critical Care Summer Session.

Research has demonstrated that 13- to 18-year-old patients in the ICU rate wound care as the most painful, but all other patient populations rate simple turning as the most painful procedure in the ICU, said Ms. Pasero, a pain management educator and clinical consultant based in El Dorado Hills, Calif. "It’s no surprise that patients in the ICU remember their pain, and they identify it as a major source of stress and anxiety," she said. "Pain is often undertreated, and I think it’s because we have so many barriers in the ICU."

Barriers to effective pain management in critically ill patients include comorbidities and coadministered drugs that affect the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of analgesics. Conflicting goals of care also factor into play. "When we are managing pain, many of the drugs we use sedate," said Ms. Pasero, who cofounded the American Society for Pain Management Nursing. "That may conflict with what you’re trying to accomplish, such as the need to control pain in the presence of respiratory compromise. One of the biggest problems is that many of your patients are unable to report their own pain and a failure to properly assess patients for pain. Our failure to properly assess those who are challenging to assess is a major cause of their unrelieved pain and unnecessary suffering."

She described a framework for assessment known as the Hierarchy of Pain Measures. This includes obtaining a self-report of pain, behaviors, physiologic measures, and the presence of a pathologic condition or procedure that causes pain. "Many institutions are inserting this hierarchy into their policies and procedures," she said. "At the top of the hierarchy is a self-report of pain. Always attempt to obtain this. It will give us much of what you need."

Numerical pain rating scales can help patients tell clinicians their level of discomfort. The most common self-report pain intensity tools are the 0-10 numerical scale and two faces scales, the Faces Pain Scale – Revised tool developed by the International Association for the Study of Pain, and the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale.

Another self-report tool used in ICUs is the Iowa Pain Thermometer (Pain Med. 2007;8:585-600). This measure was originally developed for cognitively impaired elderly, but it is useful for assessing pain in all patients who have limited ability to express themselves, Ms. Pasero said.

She emphasized the importance of being sensitive to cultural differences when assessing for pain. "Folks who do not speak the language of the person caring for them are at very high risk for undertreated pain," she said. "We need to be careful about using family members to do our translation. Studies show that family members from some cultures may hesitate to discuss pain. Get as close as you can to the patient’s own report of pain."

Certain patient behaviors are good indicators of pain, such as frowns, grimaces, tears, guarding the site of pain, pulling at tubes, seeking attention, resisting passive movement, being combative, being intolerant of ventilators, and being confused. "Physiologic measures such as increased heart rate and blood pressure are considered very poor indicators of pain," noted Ms. Pasero, who is coauthor along with Margo McCaffery, R.N., of "Pain Assessment and Pharmacologic Management." (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2011). "There are multiple factors that influence vital signs. You give a lot of drugs to keep vital signs stable, so to expect a patient to fight against that to show you that they have pain with an elevated heart rate or elevated blood pressure is not a good idea. However, abnormalities or changes in vital signs should serve as a trigger to perform a good pain assessment."

She recommends using reliable and valid behavioral pain assessment tool such as the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool or the Behavioral Pain Scale in those who cannot report pain. "In unresponsive patients who cannot demonstrate behaviors and have underlying pathology or conditions thought to be painful, such as surgery, trauma, or mechanical ventilation, we need to assume they have pain and do the best we can to manage it with the administration of recommended doses of analgesics," she said. "Also assume pain is present in patients undergoing painful activities or procedures such as turning, suctioning, or wound care. It’s important to document the underlying pathology or activity assumed to be painful."

Ms. Pasero said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to make.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE UCSD CRITICAL CARE SUMMER SESSION

Managing blunt abdominal trauma in children tricky business

SAN DIEGO – In the clinical experience of Dr. Julia Grabowski, managing blunt abdominal trauma injuries in children can be tricky business because of the wide variation in development between infants and adolescents.

Such differences "affect both the care of the injured child and injury prevention efforts," she said at the University of California San Diego Critical Care Summer Session. Anatomic considerations in the management of pediatric abdominal trauma include the close proximity of multiple organs, "which can affect their overall injury patterns," said Dr. Grabowski, a pediatric surgeon at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego. "In addition, their solid organs are larger compared with the rest of their abdomen. They generally have less body fat, less connective tissue, and less muscle mass, and their bony skeleton is incompletely ossified."

Compared with adults, the rib cage in children "is higher and much more pliable, so rib fractures are quite uncommon in the pediatric population," she said. "If you do see a child who has a rib fracture, that’s a trigger to think they had a much worse trauma than you originally expected."

Blunt injuries account for about 90% of all injuries and deaths in children, Dr. Grabowski said. In blunt abdominal trauma, the most common mechanism of action is a fall, followed by motor vehicle collisions, pedestrian versus auto accidents, bicycle accidents, and assaults. The most commonly injured organs are the spleen and liver, followed distantly by the kidney, small bowel, and pancreas.

Diagnostic evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma includes C-spine imaging for those in whom you suspect C-spine trauma, chest x-rays, anterior-posterior x-ray of the pelvis as necessary, and a computed tomography scan, "which is really the workhorse of evaluation for blunt abdominal trauma," she said. Lab studies may include CBC, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, and blood type and cross.

Another option is Focused Assessment With Sonography for Trauma (the FAST scan). According to Dr. Grabowski, recent research has demonstrated that FAST has a low sensitivity and is inappropriate for use in hemodynamically stable children, but that it may be useful in unstable patients.

For splenic and hepatic injuries, grade and clinical exam dictates the need for PICU admission, frequency of vital signs, hematocrit and hemoglobin testing, diet, and activity. The American Pediatric Surgical Association published guidelines for the management of hemodynamically stable children with isolated spleen or liver injury (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2000; 35:164-9).

"Most children are in the hospital 1 day longer than their grade of injury, and they’re out of any activity for 2 weeks longer than their grade of injury," said Dr. Grabowski. Splenic injuries from to sports competition "are quite common, especially around football and hockey seasons," as are those caused by motor vehicle accidents and accidents from all-terrain vehicles. Common complaints include abdominal pain/tenderness, shoulder pain, nausea and vomiting, and anemia. CT scan is 98% sensitive in identifying the injury.

"Over time we have found that splenic salvage can be achieved in greater than 90% of children with blunt splenic injury, even up to a grade IV or V injury," she said. "Management of splenic injury should be based on physiologic parameters, rather than on a grading of the spleen injury or the presence of ‘blush’ on a CT scan. When an operation is required it’s usually for hemodynamic stability or for ongoing transfusion requirements."

For patients who undergo splenectomy, incidence of overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis is thought to be about 0.8%, and the risk is greatest in the first 2 years. "Even though it’s such a low incidence, overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis has a very high mortality, up to 50%," she said. "It’s important to educate the patients and the parents that if they develop a fever, it’s important to come to the hospital as soon as possible for evaluation."

Next, Dr. Grabowski discussed hepatic injuries, which involve the right lobe of the liver in 60%-78% of cases. Children with hepatic injuries commonly present with abdominal pain/tenderness and 56%-100% have associated injuries, most commonly involving the brain. Shock occurs in fewer than 10% of patients who present with a liver injury, while an aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT) level of greater than 250 units/L suggests liver injury.

Nonoperative treatment is successful about 90% of the time. This requires hemodynamic stability and absence of peritoneal signs. "Head injury is not a contraindication for nonoperative management," she said. "We have less experience with, and less studies looking at, angioembolization for hepatic injuries, but since we’ve had such good success with splenic injuries, we think it’s going to be helpful for hepatic injuries as well."

Operative treatment is indicated in cases of persistent bleeding, hemodynamic instability, or to rule out a missed injury.

Dr. Grabowski pointed out that there is little value in routine follow-up imaging studies after splenic or hepatic injury. The American Pediatric Surgical Association guidelines recommend a return to normal activities after a period of 2 weeks plus the grade of injury. "Normal activity is considered returning to school and walking," she said. "It’s not return to sports competition like football or wrestling. We usually say if your spleen gets injured during the football season, you can return to play the following season."

Bowel injuries comprise just 15% of intra-abdominal injuries in children, "but there is a high mortality, about 25%, and they’re easily missed on initial exam," Dr. Grabowski said. Clinical examination remains the most important diagnostic tool in the awake patient because only 60% of radiographic studies will be diagnostic. "It’s a difficult diagnosis to make, and delays occur in about 10% of cases," she said. "But many good studies have shown that children who have a delayed diagnosis of bowel injury did not have a worse outcome."

Seat belt injures also are common because most children are too large for car seats and too small for an adult seat belt system. "So they either don’t wear the cross-chest harness or they wear it inappropriately," Dr. Grabowski said. "Children also have a higher center of gravity, an immaturity and lack of structural integrity of their bony pelvis, and in most cases they have a relative paucity of abdominal musculature. Because they’re wearing their seat belt wrong they have a tendency to get injured by their seat belt more often than adults do."

An estimated 50%-70% of seat belt injuries are associated with a chance fracture, or a rupture of the posterior spinal ligament, or wedge, most commonly at L1 and L3. Those particular injuries "are very often associated with a bowel injury, so there’s a high index of suspicion in those children," she said. Indications for exploration in children who present with seat belt injuries include hemodynamic instability, pneumoperitoneum, peritonitis, bladder rupture, abdominal tenderness with free fluid in pelvis on CT without solid organ injury, if they worsen on exam, if they spike a fever, or if their labs become abnormal.

Dr. Grabowski advises clinicians to think nonaccidental trauma if children present with no history or explanation for injury, if the history is incompatible with the type or degree of injury, if a sibling is blamed for the injury, if caregivers give conflicting histories when interviewed separately, or if the history is not credible. "Health care providers are mandated reporters of nonaccidental trauma," she said, noting than an estimated 1 million children are victims of abuse each year.

Dr. Grabowski said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to make.

SAN DIEGO – In the clinical experience of Dr. Julia Grabowski, managing blunt abdominal trauma injuries in children can be tricky business because of the wide variation in development between infants and adolescents.

Such differences "affect both the care of the injured child and injury prevention efforts," she said at the University of California San Diego Critical Care Summer Session. Anatomic considerations in the management of pediatric abdominal trauma include the close proximity of multiple organs, "which can affect their overall injury patterns," said Dr. Grabowski, a pediatric surgeon at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego. "In addition, their solid organs are larger compared with the rest of their abdomen. They generally have less body fat, less connective tissue, and less muscle mass, and their bony skeleton is incompletely ossified."

Compared with adults, the rib cage in children "is higher and much more pliable, so rib fractures are quite uncommon in the pediatric population," she said. "If you do see a child who has a rib fracture, that’s a trigger to think they had a much worse trauma than you originally expected."

Blunt injuries account for about 90% of all injuries and deaths in children, Dr. Grabowski said. In blunt abdominal trauma, the most common mechanism of action is a fall, followed by motor vehicle collisions, pedestrian versus auto accidents, bicycle accidents, and assaults. The most commonly injured organs are the spleen and liver, followed distantly by the kidney, small bowel, and pancreas.

Diagnostic evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma includes C-spine imaging for those in whom you suspect C-spine trauma, chest x-rays, anterior-posterior x-ray of the pelvis as necessary, and a computed tomography scan, "which is really the workhorse of evaluation for blunt abdominal trauma," she said. Lab studies may include CBC, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, and blood type and cross.

Another option is Focused Assessment With Sonography for Trauma (the FAST scan). According to Dr. Grabowski, recent research has demonstrated that FAST has a low sensitivity and is inappropriate for use in hemodynamically stable children, but that it may be useful in unstable patients.

For splenic and hepatic injuries, grade and clinical exam dictates the need for PICU admission, frequency of vital signs, hematocrit and hemoglobin testing, diet, and activity. The American Pediatric Surgical Association published guidelines for the management of hemodynamically stable children with isolated spleen or liver injury (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2000; 35:164-9).

"Most children are in the hospital 1 day longer than their grade of injury, and they’re out of any activity for 2 weeks longer than their grade of injury," said Dr. Grabowski. Splenic injuries from to sports competition "are quite common, especially around football and hockey seasons," as are those caused by motor vehicle accidents and accidents from all-terrain vehicles. Common complaints include abdominal pain/tenderness, shoulder pain, nausea and vomiting, and anemia. CT scan is 98% sensitive in identifying the injury.

"Over time we have found that splenic salvage can be achieved in greater than 90% of children with blunt splenic injury, even up to a grade IV or V injury," she said. "Management of splenic injury should be based on physiologic parameters, rather than on a grading of the spleen injury or the presence of ‘blush’ on a CT scan. When an operation is required it’s usually for hemodynamic stability or for ongoing transfusion requirements."

For patients who undergo splenectomy, incidence of overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis is thought to be about 0.8%, and the risk is greatest in the first 2 years. "Even though it’s such a low incidence, overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis has a very high mortality, up to 50%," she said. "It’s important to educate the patients and the parents that if they develop a fever, it’s important to come to the hospital as soon as possible for evaluation."

Next, Dr. Grabowski discussed hepatic injuries, which involve the right lobe of the liver in 60%-78% of cases. Children with hepatic injuries commonly present with abdominal pain/tenderness and 56%-100% have associated injuries, most commonly involving the brain. Shock occurs in fewer than 10% of patients who present with a liver injury, while an aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT) level of greater than 250 units/L suggests liver injury.

Nonoperative treatment is successful about 90% of the time. This requires hemodynamic stability and absence of peritoneal signs. "Head injury is not a contraindication for nonoperative management," she said. "We have less experience with, and less studies looking at, angioembolization for hepatic injuries, but since we’ve had such good success with splenic injuries, we think it’s going to be helpful for hepatic injuries as well."

Operative treatment is indicated in cases of persistent bleeding, hemodynamic instability, or to rule out a missed injury.

Dr. Grabowski pointed out that there is little value in routine follow-up imaging studies after splenic or hepatic injury. The American Pediatric Surgical Association guidelines recommend a return to normal activities after a period of 2 weeks plus the grade of injury. "Normal activity is considered returning to school and walking," she said. "It’s not return to sports competition like football or wrestling. We usually say if your spleen gets injured during the football season, you can return to play the following season."

Bowel injuries comprise just 15% of intra-abdominal injuries in children, "but there is a high mortality, about 25%, and they’re easily missed on initial exam," Dr. Grabowski said. Clinical examination remains the most important diagnostic tool in the awake patient because only 60% of radiographic studies will be diagnostic. "It’s a difficult diagnosis to make, and delays occur in about 10% of cases," she said. "But many good studies have shown that children who have a delayed diagnosis of bowel injury did not have a worse outcome."

Seat belt injures also are common because most children are too large for car seats and too small for an adult seat belt system. "So they either don’t wear the cross-chest harness or they wear it inappropriately," Dr. Grabowski said. "Children also have a higher center of gravity, an immaturity and lack of structural integrity of their bony pelvis, and in most cases they have a relative paucity of abdominal musculature. Because they’re wearing their seat belt wrong they have a tendency to get injured by their seat belt more often than adults do."

An estimated 50%-70% of seat belt injuries are associated with a chance fracture, or a rupture of the posterior spinal ligament, or wedge, most commonly at L1 and L3. Those particular injuries "are very often associated with a bowel injury, so there’s a high index of suspicion in those children," she said. Indications for exploration in children who present with seat belt injuries include hemodynamic instability, pneumoperitoneum, peritonitis, bladder rupture, abdominal tenderness with free fluid in pelvis on CT without solid organ injury, if they worsen on exam, if they spike a fever, or if their labs become abnormal.

Dr. Grabowski advises clinicians to think nonaccidental trauma if children present with no history or explanation for injury, if the history is incompatible with the type or degree of injury, if a sibling is blamed for the injury, if caregivers give conflicting histories when interviewed separately, or if the history is not credible. "Health care providers are mandated reporters of nonaccidental trauma," she said, noting than an estimated 1 million children are victims of abuse each year.

Dr. Grabowski said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to make.

SAN DIEGO – In the clinical experience of Dr. Julia Grabowski, managing blunt abdominal trauma injuries in children can be tricky business because of the wide variation in development between infants and adolescents.

Such differences "affect both the care of the injured child and injury prevention efforts," she said at the University of California San Diego Critical Care Summer Session. Anatomic considerations in the management of pediatric abdominal trauma include the close proximity of multiple organs, "which can affect their overall injury patterns," said Dr. Grabowski, a pediatric surgeon at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego. "In addition, their solid organs are larger compared with the rest of their abdomen. They generally have less body fat, less connective tissue, and less muscle mass, and their bony skeleton is incompletely ossified."

Compared with adults, the rib cage in children "is higher and much more pliable, so rib fractures are quite uncommon in the pediatric population," she said. "If you do see a child who has a rib fracture, that’s a trigger to think they had a much worse trauma than you originally expected."

Blunt injuries account for about 90% of all injuries and deaths in children, Dr. Grabowski said. In blunt abdominal trauma, the most common mechanism of action is a fall, followed by motor vehicle collisions, pedestrian versus auto accidents, bicycle accidents, and assaults. The most commonly injured organs are the spleen and liver, followed distantly by the kidney, small bowel, and pancreas.

Diagnostic evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma includes C-spine imaging for those in whom you suspect C-spine trauma, chest x-rays, anterior-posterior x-ray of the pelvis as necessary, and a computed tomography scan, "which is really the workhorse of evaluation for blunt abdominal trauma," she said. Lab studies may include CBC, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, and blood type and cross.

Another option is Focused Assessment With Sonography for Trauma (the FAST scan). According to Dr. Grabowski, recent research has demonstrated that FAST has a low sensitivity and is inappropriate for use in hemodynamically stable children, but that it may be useful in unstable patients.

For splenic and hepatic injuries, grade and clinical exam dictates the need for PICU admission, frequency of vital signs, hematocrit and hemoglobin testing, diet, and activity. The American Pediatric Surgical Association published guidelines for the management of hemodynamically stable children with isolated spleen or liver injury (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2000; 35:164-9).

"Most children are in the hospital 1 day longer than their grade of injury, and they’re out of any activity for 2 weeks longer than their grade of injury," said Dr. Grabowski. Splenic injuries from to sports competition "are quite common, especially around football and hockey seasons," as are those caused by motor vehicle accidents and accidents from all-terrain vehicles. Common complaints include abdominal pain/tenderness, shoulder pain, nausea and vomiting, and anemia. CT scan is 98% sensitive in identifying the injury.

"Over time we have found that splenic salvage can be achieved in greater than 90% of children with blunt splenic injury, even up to a grade IV or V injury," she said. "Management of splenic injury should be based on physiologic parameters, rather than on a grading of the spleen injury or the presence of ‘blush’ on a CT scan. When an operation is required it’s usually for hemodynamic stability or for ongoing transfusion requirements."

For patients who undergo splenectomy, incidence of overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis is thought to be about 0.8%, and the risk is greatest in the first 2 years. "Even though it’s such a low incidence, overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis has a very high mortality, up to 50%," she said. "It’s important to educate the patients and the parents that if they develop a fever, it’s important to come to the hospital as soon as possible for evaluation."

Next, Dr. Grabowski discussed hepatic injuries, which involve the right lobe of the liver in 60%-78% of cases. Children with hepatic injuries commonly present with abdominal pain/tenderness and 56%-100% have associated injuries, most commonly involving the brain. Shock occurs in fewer than 10% of patients who present with a liver injury, while an aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT) level of greater than 250 units/L suggests liver injury.

Nonoperative treatment is successful about 90% of the time. This requires hemodynamic stability and absence of peritoneal signs. "Head injury is not a contraindication for nonoperative management," she said. "We have less experience with, and less studies looking at, angioembolization for hepatic injuries, but since we’ve had such good success with splenic injuries, we think it’s going to be helpful for hepatic injuries as well."

Operative treatment is indicated in cases of persistent bleeding, hemodynamic instability, or to rule out a missed injury.

Dr. Grabowski pointed out that there is little value in routine follow-up imaging studies after splenic or hepatic injury. The American Pediatric Surgical Association guidelines recommend a return to normal activities after a period of 2 weeks plus the grade of injury. "Normal activity is considered returning to school and walking," she said. "It’s not return to sports competition like football or wrestling. We usually say if your spleen gets injured during the football season, you can return to play the following season."

Bowel injuries comprise just 15% of intra-abdominal injuries in children, "but there is a high mortality, about 25%, and they’re easily missed on initial exam," Dr. Grabowski said. Clinical examination remains the most important diagnostic tool in the awake patient because only 60% of radiographic studies will be diagnostic. "It’s a difficult diagnosis to make, and delays occur in about 10% of cases," she said. "But many good studies have shown that children who have a delayed diagnosis of bowel injury did not have a worse outcome."

Seat belt injures also are common because most children are too large for car seats and too small for an adult seat belt system. "So they either don’t wear the cross-chest harness or they wear it inappropriately," Dr. Grabowski said. "Children also have a higher center of gravity, an immaturity and lack of structural integrity of their bony pelvis, and in most cases they have a relative paucity of abdominal musculature. Because they’re wearing their seat belt wrong they have a tendency to get injured by their seat belt more often than adults do."

An estimated 50%-70% of seat belt injuries are associated with a chance fracture, or a rupture of the posterior spinal ligament, or wedge, most commonly at L1 and L3. Those particular injuries "are very often associated with a bowel injury, so there’s a high index of suspicion in those children," she said. Indications for exploration in children who present with seat belt injuries include hemodynamic instability, pneumoperitoneum, peritonitis, bladder rupture, abdominal tenderness with free fluid in pelvis on CT without solid organ injury, if they worsen on exam, if they spike a fever, or if their labs become abnormal.

Dr. Grabowski advises clinicians to think nonaccidental trauma if children present with no history or explanation for injury, if the history is incompatible with the type or degree of injury, if a sibling is blamed for the injury, if caregivers give conflicting histories when interviewed separately, or if the history is not credible. "Health care providers are mandated reporters of nonaccidental trauma," she said, noting than an estimated 1 million children are victims of abuse each year.

Dr. Grabowski said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to make.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE UCSD CRITICAL CARE SUMMER SESSION

Critically ill obstetric patients: Delivering the right care

SAN DIEGO – Fewer than 1% of pregnant women present to the intensive care unit critically ill, but when they do, "there’s often significant morbidity and mortality," Dr. Kimberly S. Robbins said at the University of California, San Diego Critical Care Summer Session.

Dr. Robbins, an assistant professor in the UCSD department of anesthesiology, noted that the greatest physiologic changes of pregnancy affect the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems, and the most common conditions that land obstetric patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) are obstetric hemorrhage and complications of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

"In general we consider pregnant patients to be potentially difficult airway patients, or difficult to intubate," she said. "That’s because pregnant patients are predisposed to edema and swollen airways." This patient population also has increased minute ventilation, "mostly because of an increase in tidal volume but also due to an increase in respiratory rate. They have increased oxygen demand, an increased metabolic rate because they are supplying oxygen to another being, and they have decreased functional residual capacity, which is the amount of volume that’s left in the lung after passive expiration."

From a cardiovascular standpoint, pregnant patients have an increased cardiac output both from an increased stroke volume and an increased heart rate. "During pregnancy the heart is shifted upward and to the left," Dr. Robbins added. "That impacts where you place your hands for CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation]. We also commonly see a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and diastolic blood pressure, as well as aortocaval compression. This means that the large gravid uterus can compress the great vessels. Not only does that impede venous return to the heart, but you can also get a decrease in the outflow of blood from the heart into the aorta."

Pregnant patients also experience a 45% increase in blood volume. This makes them relatively anemic "because there’s a relative increase in the plasma volume over the red cell volume," she explained. "Normal hemoglobin in a pregnant patient is around 11 or 12 g/dL."

Neurologically, pregnant patients can experience enhanced toxicity of local anesthetics used during cesarean section and during labor and delivery. Such complications "can land a person in the ICU," Dr. Robbins said. "Pregnant patients also have decreased anesthetic requirements. This is important as we’re titrating our sedatives or analgesics in the ICU. They also have distention of their epidural venous plexus. This makes it more likely that we may inadvertently inject local anesthetic into the vasculature and cause complications."

From a gastrointestinal standpoint, pregnant patients are considered full-stomach patients at all times, "even if they’ve had nothing by mouth," she said. "This is believed to occur after the first trimester, typically because of increased gastric pressure and decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone. During labor we see decreased gastric emptying, increased gastric volume, and decreased gastric pH levels."

Pregnancy also impacts renal function by increasing renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate. In addition, it can cause decreased levels of creatinine and mild glucosuria and proteinuria. From an endocrine standpoint, pregnant patients have impaired glucose tolerance, increased sensitivity to insulin, and an increase in T3, T4, and thyroid size.

Dr. Robbins went on to discuss preeclampsia, a hypertensive disorder that causes 50,000-70,000 deaths worldwide per year. She characterized the condition as a triad of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema that usually occurs during a woman’s first pregnancy. Other factors include molar pregnancy, multiple gestation, and vascular endothelial disorders. General diagnostic criteria include at least 20 weeks gestation, new-onset hypertension (blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or 30/15 increase x2 at least 6 hours apart), proteinuria of greater than 0.3 g/day, and generalized edema or weight gain greater than 5 pounds/week.

Diagnostic criteria for severe preeclampsia include a systolic blood pressure of greater than 160 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of greater than 110 mm Hg sustained, proteinuria of greater than 5 g/day, and signs of end organ dysfunction.

The pathophysiology of preeclampsia is unknown. "This is probably the greatest area of research in obstetrics and obstetric anesthesiology," Dr. Robbins said. "Some have postulated that it is a dysfunction of the maternal endothelium that develops because of abnormal formation of the placenta such that the placenta does not normally invade into the maternal vasculature. There are vasoactive substances that are released into the maternal circulation. That causes dysfunction of the maternal endothelium."

Patients with mild preeclampsia can be treated expectantly, but if the gestational age is greater than 37 weeks delivery should be considered. "The hallmark of treatment is prompt delivery of the fetus," she said.

For patients with severe preeclampsia, the focus is on improving placental perfusion through optimizing maternal cardiac output and peripheral vasodilation. "Most patients with pregnancy-induced hypertension are volume depleted and require careful volume repletion," she said. "Continuous fetal monitoring is also warranted."

In cases of severe preeclampsia, magnesium sulfate is the standard seizure prophylaxis. Dr. Robbins and her associates typically give a loading dose of 4-6 grams over 20 minutes, and then they run an infusion of 1-2 g/hr to keep the patient in a range of 4-8 mg/dL. "We can start to see toxicity such as loss of deep tendon reflexes at magnesium levels above 10 mg/dL," she said.

Hallmark agents for blood pressure control include hydralazine and labetalol. "You want to avoid rapid vasodilation and manage fluids in a goal-directed fashion," she said. "You may see these patients receiving steroids if their gestational age is less than 34 weeks. That’s to help with fetal lung maturity."

If preeclampsia progresses to seizures, magnesium therapy is the mainstay of treatment. "Once the patient is stabilized, she should undergo a neurologic evaluation and imaging to rule out other things such as stroke, hemorrhage, epilepsy, or a tumor," she said. "The highest risk of morbidity in this group of patients is from cerebrovascular events, including both ischemic and hemorrhagic events."

Patients with preeclampsia face an increased risk for HELLP syndrome, which stands for hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets. "The treatment here is delivery of the fetus and other supportive measures," Dr. Robbins said. Steroids have not been shown to be beneficial (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;193:1591-8). The clinical course of patients with HELLP syndrome "is fraught with complications, including liver hematoma rupture and renal failure, so you need to be prepared for that."

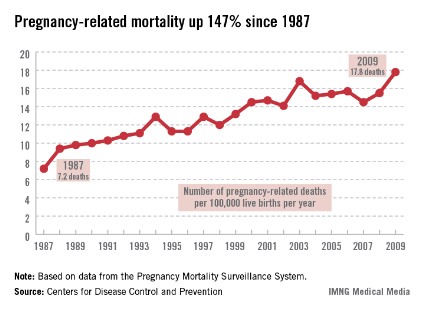

Dr. Robbins also discussed obstetric hemorrhage, which is the second-leading cause of pregnancy-related death in the United States and is the leading cause in developing countries. Hemorrhage is defined as losing greater than 500 mL of blood at vaginal delivery or greater than 1,000 mL after cesarean section. "Life-threatening hemorrhage can occur in the antepartum or postpartum period," she said. Antepartum hemorrhage is usually associated with placenta previa or abruption, while postpartum hemorrhage is most often associated with uterine atony. Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage include preexisting anemia, obesity, fetal macrosomia, prior cesarean sections, and multiple gestations. "In these patients, disseminated intravascular coagulation may develop because of the dilutional effects of massive transfusion or some other underlying process," she said.

Treatment of obstetric hemorrhage includes volume resuscitation, correction of coagulopathy, maintaining adequate tissue perfusion, and controlling the source of blood loss. "Patients with uterine atony can be treated with uterine massage or with uterotonic drugs such as oxytocin, Methergine [methylergonovine], Hemabate [carboprost], and misoprostol," Dr. Robbins said. Surgical treatments such as uterine compression sutures or hysterectomy may be required.

Dr. Robbins said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SAN DIEGO – Fewer than 1% of pregnant women present to the intensive care unit critically ill, but when they do, "there’s often significant morbidity and mortality," Dr. Kimberly S. Robbins said at the University of California, San Diego Critical Care Summer Session.

Dr. Robbins, an assistant professor in the UCSD department of anesthesiology, noted that the greatest physiologic changes of pregnancy affect the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems, and the most common conditions that land obstetric patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) are obstetric hemorrhage and complications of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

"In general we consider pregnant patients to be potentially difficult airway patients, or difficult to intubate," she said. "That’s because pregnant patients are predisposed to edema and swollen airways." This patient population also has increased minute ventilation, "mostly because of an increase in tidal volume but also due to an increase in respiratory rate. They have increased oxygen demand, an increased metabolic rate because they are supplying oxygen to another being, and they have decreased functional residual capacity, which is the amount of volume that’s left in the lung after passive expiration."

From a cardiovascular standpoint, pregnant patients have an increased cardiac output both from an increased stroke volume and an increased heart rate. "During pregnancy the heart is shifted upward and to the left," Dr. Robbins added. "That impacts where you place your hands for CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation]. We also commonly see a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and diastolic blood pressure, as well as aortocaval compression. This means that the large gravid uterus can compress the great vessels. Not only does that impede venous return to the heart, but you can also get a decrease in the outflow of blood from the heart into the aorta."

Pregnant patients also experience a 45% increase in blood volume. This makes them relatively anemic "because there’s a relative increase in the plasma volume over the red cell volume," she explained. "Normal hemoglobin in a pregnant patient is around 11 or 12 g/dL."

Neurologically, pregnant patients can experience enhanced toxicity of local anesthetics used during cesarean section and during labor and delivery. Such complications "can land a person in the ICU," Dr. Robbins said. "Pregnant patients also have decreased anesthetic requirements. This is important as we’re titrating our sedatives or analgesics in the ICU. They also have distention of their epidural venous plexus. This makes it more likely that we may inadvertently inject local anesthetic into the vasculature and cause complications."

From a gastrointestinal standpoint, pregnant patients are considered full-stomach patients at all times, "even if they’ve had nothing by mouth," she said. "This is believed to occur after the first trimester, typically because of increased gastric pressure and decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone. During labor we see decreased gastric emptying, increased gastric volume, and decreased gastric pH levels."

Pregnancy also impacts renal function by increasing renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate. In addition, it can cause decreased levels of creatinine and mild glucosuria and proteinuria. From an endocrine standpoint, pregnant patients have impaired glucose tolerance, increased sensitivity to insulin, and an increase in T3, T4, and thyroid size.

Dr. Robbins went on to discuss preeclampsia, a hypertensive disorder that causes 50,000-70,000 deaths worldwide per year. She characterized the condition as a triad of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema that usually occurs during a woman’s first pregnancy. Other factors include molar pregnancy, multiple gestation, and vascular endothelial disorders. General diagnostic criteria include at least 20 weeks gestation, new-onset hypertension (blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or 30/15 increase x2 at least 6 hours apart), proteinuria of greater than 0.3 g/day, and generalized edema or weight gain greater than 5 pounds/week.

Diagnostic criteria for severe preeclampsia include a systolic blood pressure of greater than 160 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of greater than 110 mm Hg sustained, proteinuria of greater than 5 g/day, and signs of end organ dysfunction.

The pathophysiology of preeclampsia is unknown. "This is probably the greatest area of research in obstetrics and obstetric anesthesiology," Dr. Robbins said. "Some have postulated that it is a dysfunction of the maternal endothelium that develops because of abnormal formation of the placenta such that the placenta does not normally invade into the maternal vasculature. There are vasoactive substances that are released into the maternal circulation. That causes dysfunction of the maternal endothelium."

Patients with mild preeclampsia can be treated expectantly, but if the gestational age is greater than 37 weeks delivery should be considered. "The hallmark of treatment is prompt delivery of the fetus," she said.

For patients with severe preeclampsia, the focus is on improving placental perfusion through optimizing maternal cardiac output and peripheral vasodilation. "Most patients with pregnancy-induced hypertension are volume depleted and require careful volume repletion," she said. "Continuous fetal monitoring is also warranted."

In cases of severe preeclampsia, magnesium sulfate is the standard seizure prophylaxis. Dr. Robbins and her associates typically give a loading dose of 4-6 grams over 20 minutes, and then they run an infusion of 1-2 g/hr to keep the patient in a range of 4-8 mg/dL. "We can start to see toxicity such as loss of deep tendon reflexes at magnesium levels above 10 mg/dL," she said.

Hallmark agents for blood pressure control include hydralazine and labetalol. "You want to avoid rapid vasodilation and manage fluids in a goal-directed fashion," she said. "You may see these patients receiving steroids if their gestational age is less than 34 weeks. That’s to help with fetal lung maturity."

If preeclampsia progresses to seizures, magnesium therapy is the mainstay of treatment. "Once the patient is stabilized, she should undergo a neurologic evaluation and imaging to rule out other things such as stroke, hemorrhage, epilepsy, or a tumor," she said. "The highest risk of morbidity in this group of patients is from cerebrovascular events, including both ischemic and hemorrhagic events."

Patients with preeclampsia face an increased risk for HELLP syndrome, which stands for hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets. "The treatment here is delivery of the fetus and other supportive measures," Dr. Robbins said. Steroids have not been shown to be beneficial (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;193:1591-8). The clinical course of patients with HELLP syndrome "is fraught with complications, including liver hematoma rupture and renal failure, so you need to be prepared for that."

Dr. Robbins also discussed obstetric hemorrhage, which is the second-leading cause of pregnancy-related death in the United States and is the leading cause in developing countries. Hemorrhage is defined as losing greater than 500 mL of blood at vaginal delivery or greater than 1,000 mL after cesarean section. "Life-threatening hemorrhage can occur in the antepartum or postpartum period," she said. Antepartum hemorrhage is usually associated with placenta previa or abruption, while postpartum hemorrhage is most often associated with uterine atony. Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage include preexisting anemia, obesity, fetal macrosomia, prior cesarean sections, and multiple gestations. "In these patients, disseminated intravascular coagulation may develop because of the dilutional effects of massive transfusion or some other underlying process," she said.

Treatment of obstetric hemorrhage includes volume resuscitation, correction of coagulopathy, maintaining adequate tissue perfusion, and controlling the source of blood loss. "Patients with uterine atony can be treated with uterine massage or with uterotonic drugs such as oxytocin, Methergine [methylergonovine], Hemabate [carboprost], and misoprostol," Dr. Robbins said. Surgical treatments such as uterine compression sutures or hysterectomy may be required.

Dr. Robbins said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SAN DIEGO – Fewer than 1% of pregnant women present to the intensive care unit critically ill, but when they do, "there’s often significant morbidity and mortality," Dr. Kimberly S. Robbins said at the University of California, San Diego Critical Care Summer Session.

Dr. Robbins, an assistant professor in the UCSD department of anesthesiology, noted that the greatest physiologic changes of pregnancy affect the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems, and the most common conditions that land obstetric patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) are obstetric hemorrhage and complications of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

"In general we consider pregnant patients to be potentially difficult airway patients, or difficult to intubate," she said. "That’s because pregnant patients are predisposed to edema and swollen airways." This patient population also has increased minute ventilation, "mostly because of an increase in tidal volume but also due to an increase in respiratory rate. They have increased oxygen demand, an increased metabolic rate because they are supplying oxygen to another being, and they have decreased functional residual capacity, which is the amount of volume that’s left in the lung after passive expiration."

From a cardiovascular standpoint, pregnant patients have an increased cardiac output both from an increased stroke volume and an increased heart rate. "During pregnancy the heart is shifted upward and to the left," Dr. Robbins added. "That impacts where you place your hands for CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation]. We also commonly see a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and diastolic blood pressure, as well as aortocaval compression. This means that the large gravid uterus can compress the great vessels. Not only does that impede venous return to the heart, but you can also get a decrease in the outflow of blood from the heart into the aorta."

Pregnant patients also experience a 45% increase in blood volume. This makes them relatively anemic "because there’s a relative increase in the plasma volume over the red cell volume," she explained. "Normal hemoglobin in a pregnant patient is around 11 or 12 g/dL."

Neurologically, pregnant patients can experience enhanced toxicity of local anesthetics used during cesarean section and during labor and delivery. Such complications "can land a person in the ICU," Dr. Robbins said. "Pregnant patients also have decreased anesthetic requirements. This is important as we’re titrating our sedatives or analgesics in the ICU. They also have distention of their epidural venous plexus. This makes it more likely that we may inadvertently inject local anesthetic into the vasculature and cause complications."

From a gastrointestinal standpoint, pregnant patients are considered full-stomach patients at all times, "even if they’ve had nothing by mouth," she said. "This is believed to occur after the first trimester, typically because of increased gastric pressure and decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone. During labor we see decreased gastric emptying, increased gastric volume, and decreased gastric pH levels."

Pregnancy also impacts renal function by increasing renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate. In addition, it can cause decreased levels of creatinine and mild glucosuria and proteinuria. From an endocrine standpoint, pregnant patients have impaired glucose tolerance, increased sensitivity to insulin, and an increase in T3, T4, and thyroid size.

Dr. Robbins went on to discuss preeclampsia, a hypertensive disorder that causes 50,000-70,000 deaths worldwide per year. She characterized the condition as a triad of hypertension, proteinuria, and edema that usually occurs during a woman’s first pregnancy. Other factors include molar pregnancy, multiple gestation, and vascular endothelial disorders. General diagnostic criteria include at least 20 weeks gestation, new-onset hypertension (blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or 30/15 increase x2 at least 6 hours apart), proteinuria of greater than 0.3 g/day, and generalized edema or weight gain greater than 5 pounds/week.

Diagnostic criteria for severe preeclampsia include a systolic blood pressure of greater than 160 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of greater than 110 mm Hg sustained, proteinuria of greater than 5 g/day, and signs of end organ dysfunction.

The pathophysiology of preeclampsia is unknown. "This is probably the greatest area of research in obstetrics and obstetric anesthesiology," Dr. Robbins said. "Some have postulated that it is a dysfunction of the maternal endothelium that develops because of abnormal formation of the placenta such that the placenta does not normally invade into the maternal vasculature. There are vasoactive substances that are released into the maternal circulation. That causes dysfunction of the maternal endothelium."

Patients with mild preeclampsia can be treated expectantly, but if the gestational age is greater than 37 weeks delivery should be considered. "The hallmark of treatment is prompt delivery of the fetus," she said.

For patients with severe preeclampsia, the focus is on improving placental perfusion through optimizing maternal cardiac output and peripheral vasodilation. "Most patients with pregnancy-induced hypertension are volume depleted and require careful volume repletion," she said. "Continuous fetal monitoring is also warranted."

In cases of severe preeclampsia, magnesium sulfate is the standard seizure prophylaxis. Dr. Robbins and her associates typically give a loading dose of 4-6 grams over 20 minutes, and then they run an infusion of 1-2 g/hr to keep the patient in a range of 4-8 mg/dL. "We can start to see toxicity such as loss of deep tendon reflexes at magnesium levels above 10 mg/dL," she said.

Hallmark agents for blood pressure control include hydralazine and labetalol. "You want to avoid rapid vasodilation and manage fluids in a goal-directed fashion," she said. "You may see these patients receiving steroids if their gestational age is less than 34 weeks. That’s to help with fetal lung maturity."

If preeclampsia progresses to seizures, magnesium therapy is the mainstay of treatment. "Once the patient is stabilized, she should undergo a neurologic evaluation and imaging to rule out other things such as stroke, hemorrhage, epilepsy, or a tumor," she said. "The highest risk of morbidity in this group of patients is from cerebrovascular events, including both ischemic and hemorrhagic events."

Patients with preeclampsia face an increased risk for HELLP syndrome, which stands for hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets. "The treatment here is delivery of the fetus and other supportive measures," Dr. Robbins said. Steroids have not been shown to be beneficial (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;193:1591-8). The clinical course of patients with HELLP syndrome "is fraught with complications, including liver hematoma rupture and renal failure, so you need to be prepared for that."

Dr. Robbins also discussed obstetric hemorrhage, which is the second-leading cause of pregnancy-related death in the United States and is the leading cause in developing countries. Hemorrhage is defined as losing greater than 500 mL of blood at vaginal delivery or greater than 1,000 mL after cesarean section. "Life-threatening hemorrhage can occur in the antepartum or postpartum period," she said. Antepartum hemorrhage is usually associated with placenta previa or abruption, while postpartum hemorrhage is most often associated with uterine atony. Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage include preexisting anemia, obesity, fetal macrosomia, prior cesarean sections, and multiple gestations. "In these patients, disseminated intravascular coagulation may develop because of the dilutional effects of massive transfusion or some other underlying process," she said.

Treatment of obstetric hemorrhage includes volume resuscitation, correction of coagulopathy, maintaining adequate tissue perfusion, and controlling the source of blood loss. "Patients with uterine atony can be treated with uterine massage or with uterotonic drugs such as oxytocin, Methergine [methylergonovine], Hemabate [carboprost], and misoprostol," Dr. Robbins said. Surgical treatments such as uterine compression sutures or hysterectomy may be required.

Dr. Robbins said that she had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE UCSD CRITICAL CARE SUMMER SESSION