User login

Metabolic Surgery Merits Bigger Role in Diabetes Management

This past March, the International Diabetes Federation released a position statement supporting bariatric surgery as an appropriate therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes who do not achieve their recommended treatment targets with medical therapy, particularly if they also have obesity-related comorbidities.

The statement acknowledged that bariatric surgery should be an accepted option in patients with type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2, and that it should be considered as an alternative treatment option in patients with a body mass index of 30-35 when diabetes is inadequately controlled by optimal medical regimens.

To translate this approach into practice, physicians who provide routine care to patients with type 2 diabetes – primary care physicians and endocrinologists – should inform appropriate patients that bariatric surgery is a metabolic surgical option in the treatment algorithm for diabetes. Bariatric surgeons should offer the type of bariatric surgery that best suits each patient’s individual situation. In many circumstances, these surgeons allow patients to choose the operation they believe is right for them, an approach that is unique to bariatric surgery; in most surgical consultations, patients are not offered a choice of procedures. Do patients select the procedure that will optimize their success?

To date, the best bariatric surgical procedure for achieving remission of diabetes is the duodenal switch (or biliopancreatic diversion), a procedure not widely performed in the United States. It is the most technically challenging type of bariatric surgery, especially when performed laparoscopically, and it carries a higher morbidity and mortality rate than do the more common bariatric surgical procedures.

Gastric banding is often sought by patients because it is widely marketed, potentially reversible, and comes with an excellent safety profile. But while gastric banding can result in significant weight loss, it achieves remission rates of type 2 diabetes that are lower than those of gastric bypass. Some patients consider the reversibility of gastric banding to be an advantage, but it is imperative that patients who undergo any bariatric surgical procedure be committed to long-term adherence to postoperative guidelines.

When comparing the risks of surgical complications with the benefits of diabetes remission (and other obesity-related comorbidities), I believe the best option is laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. This procedure is almost as effective as the duodenal switch for resolving diabetes, yet it is safer and is widely available in the United States.

Diabetes remission is often seen prior to significant weight loss in patients who have undergone laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The reason for this has yet to be fully elucidated. There appears to be a multifactorial gut hormone response that is responsible for this metabolic effect, but this theory is still under intense study.

Efficacy of Gastric Bypass for Diabetes Remission

We published a study 2 years ago that documented the efficacy of gastric bypass for diabetes remission. We compared hemoglobin A1c levels for patients who had undergone laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with a group of morbidly obese patients treated with conventional medical therapy.

One year after surgery, 59% of the 46 patients for whom we had follow-up data had experienced full remission (Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2009;5:4-10). They no longer required any diabetic medications, and their hemoglobin A1c was 6% or lower. In contrast, only 2 of the 41 patients (5%) in the conventional medical treatment group experienced remission.

Full remission of diabetes is very difficult to achieve with medications and lifestyle modification. Bariatric surgery – more appropriately termed "metabolic surgery" – presents an unrivaled opportunity for patients with type 2 diabetes to experience full remission. It also often resolves hypertension, lowers hypercholesterolemia, and substantially improves other obesity-related comorbidities, including obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteoarthritis.

The time has come to move away from arbitrary BMI cutoffs and insurance-mandated criteria to determine whether patients with diabetes are candidates for bariatric surgery. The primary determinant should be the severity and duration of the patient’s diabetes and obesity-related comorbidities, and whether a reasonable trial of medical and lifestyle management has failed.

Results from several studies have documented that the cost of bariatric surgery for patients who are not adequately managed by their medical regimen are recouped within 2-4 years by reduced drug costs and reduced costs for managing the complications of poorly controlled diabetes (Am. J. Manag. Care 2008;14:589-96; Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2011 May 27 [doi:10.1016/j.soard.2011.05.009].

Many physicians regard bariatric surgery as dangerous, and it is held to an unreasonably high standard of success. Even though gastric bypass will produce remission in about 60% of patients with diabetes and significant benefits for another 20%-30%, it is criticized for having a 10% failure rate. Many other procedures routinely used in appropriate patients do not work in 100% of patients.

The best success one can expect from a Nissen fundoplication for control of gastroesophageal reflux disease is 85%-90%, a well-established benchmark. Why should the standards for bariatric surgery be set above thresholds we accept for other surgical interventions?

The mortality rates of minimally invasive bariatric surgery rival those of routine operations such as cholecystectomy and hip replacement. The laparoscopic era has led to reduced mortality, fewer surgical site infections, shorter hospitalizations, and faster return to full activity. But because bariatric surgery is delivered by a scalpel and not a pill, it has faced discrimination and resistance within the medical community.

Dr. Kothari is director of the Minimally Invasive Bariatric Surgery Center at Gundersen Lutheran Health System in La Crosse, Wis. He has been a consultant to Covidien, Valley Lab, and Life Cell, and has received research grants from Covidien. This column appears in Internal Medicine News, a publication of Elsevier.

This past March, the International Diabetes Federation released a position statement supporting bariatric surgery as an appropriate therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes who do not achieve their recommended treatment targets with medical therapy, particularly if they also have obesity-related comorbidities.

The statement acknowledged that bariatric surgery should be an accepted option in patients with type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2, and that it should be considered as an alternative treatment option in patients with a body mass index of 30-35 when diabetes is inadequately controlled by optimal medical regimens.

To translate this approach into practice, physicians who provide routine care to patients with type 2 diabetes – primary care physicians and endocrinologists – should inform appropriate patients that bariatric surgery is a metabolic surgical option in the treatment algorithm for diabetes. Bariatric surgeons should offer the type of bariatric surgery that best suits each patient’s individual situation. In many circumstances, these surgeons allow patients to choose the operation they believe is right for them, an approach that is unique to bariatric surgery; in most surgical consultations, patients are not offered a choice of procedures. Do patients select the procedure that will optimize their success?

To date, the best bariatric surgical procedure for achieving remission of diabetes is the duodenal switch (or biliopancreatic diversion), a procedure not widely performed in the United States. It is the most technically challenging type of bariatric surgery, especially when performed laparoscopically, and it carries a higher morbidity and mortality rate than do the more common bariatric surgical procedures.

Gastric banding is often sought by patients because it is widely marketed, potentially reversible, and comes with an excellent safety profile. But while gastric banding can result in significant weight loss, it achieves remission rates of type 2 diabetes that are lower than those of gastric bypass. Some patients consider the reversibility of gastric banding to be an advantage, but it is imperative that patients who undergo any bariatric surgical procedure be committed to long-term adherence to postoperative guidelines.

When comparing the risks of surgical complications with the benefits of diabetes remission (and other obesity-related comorbidities), I believe the best option is laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. This procedure is almost as effective as the duodenal switch for resolving diabetes, yet it is safer and is widely available in the United States.

Diabetes remission is often seen prior to significant weight loss in patients who have undergone laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The reason for this has yet to be fully elucidated. There appears to be a multifactorial gut hormone response that is responsible for this metabolic effect, but this theory is still under intense study.

Efficacy of Gastric Bypass for Diabetes Remission

We published a study 2 years ago that documented the efficacy of gastric bypass for diabetes remission. We compared hemoglobin A1c levels for patients who had undergone laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with a group of morbidly obese patients treated with conventional medical therapy.

One year after surgery, 59% of the 46 patients for whom we had follow-up data had experienced full remission (Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2009;5:4-10). They no longer required any diabetic medications, and their hemoglobin A1c was 6% or lower. In contrast, only 2 of the 41 patients (5%) in the conventional medical treatment group experienced remission.

Full remission of diabetes is very difficult to achieve with medications and lifestyle modification. Bariatric surgery – more appropriately termed "metabolic surgery" – presents an unrivaled opportunity for patients with type 2 diabetes to experience full remission. It also often resolves hypertension, lowers hypercholesterolemia, and substantially improves other obesity-related comorbidities, including obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteoarthritis.

The time has come to move away from arbitrary BMI cutoffs and insurance-mandated criteria to determine whether patients with diabetes are candidates for bariatric surgery. The primary determinant should be the severity and duration of the patient’s diabetes and obesity-related comorbidities, and whether a reasonable trial of medical and lifestyle management has failed.

Results from several studies have documented that the cost of bariatric surgery for patients who are not adequately managed by their medical regimen are recouped within 2-4 years by reduced drug costs and reduced costs for managing the complications of poorly controlled diabetes (Am. J. Manag. Care 2008;14:589-96; Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2011 May 27 [doi:10.1016/j.soard.2011.05.009].

Many physicians regard bariatric surgery as dangerous, and it is held to an unreasonably high standard of success. Even though gastric bypass will produce remission in about 60% of patients with diabetes and significant benefits for another 20%-30%, it is criticized for having a 10% failure rate. Many other procedures routinely used in appropriate patients do not work in 100% of patients.

The best success one can expect from a Nissen fundoplication for control of gastroesophageal reflux disease is 85%-90%, a well-established benchmark. Why should the standards for bariatric surgery be set above thresholds we accept for other surgical interventions?

The mortality rates of minimally invasive bariatric surgery rival those of routine operations such as cholecystectomy and hip replacement. The laparoscopic era has led to reduced mortality, fewer surgical site infections, shorter hospitalizations, and faster return to full activity. But because bariatric surgery is delivered by a scalpel and not a pill, it has faced discrimination and resistance within the medical community.

Dr. Kothari is director of the Minimally Invasive Bariatric Surgery Center at Gundersen Lutheran Health System in La Crosse, Wis. He has been a consultant to Covidien, Valley Lab, and Life Cell, and has received research grants from Covidien. This column appears in Internal Medicine News, a publication of Elsevier.

This past March, the International Diabetes Federation released a position statement supporting bariatric surgery as an appropriate therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes who do not achieve their recommended treatment targets with medical therapy, particularly if they also have obesity-related comorbidities.

The statement acknowledged that bariatric surgery should be an accepted option in patients with type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of at least 35 kg/m2, and that it should be considered as an alternative treatment option in patients with a body mass index of 30-35 when diabetes is inadequately controlled by optimal medical regimens.

To translate this approach into practice, physicians who provide routine care to patients with type 2 diabetes – primary care physicians and endocrinologists – should inform appropriate patients that bariatric surgery is a metabolic surgical option in the treatment algorithm for diabetes. Bariatric surgeons should offer the type of bariatric surgery that best suits each patient’s individual situation. In many circumstances, these surgeons allow patients to choose the operation they believe is right for them, an approach that is unique to bariatric surgery; in most surgical consultations, patients are not offered a choice of procedures. Do patients select the procedure that will optimize their success?

To date, the best bariatric surgical procedure for achieving remission of diabetes is the duodenal switch (or biliopancreatic diversion), a procedure not widely performed in the United States. It is the most technically challenging type of bariatric surgery, especially when performed laparoscopically, and it carries a higher morbidity and mortality rate than do the more common bariatric surgical procedures.

Gastric banding is often sought by patients because it is widely marketed, potentially reversible, and comes with an excellent safety profile. But while gastric banding can result in significant weight loss, it achieves remission rates of type 2 diabetes that are lower than those of gastric bypass. Some patients consider the reversibility of gastric banding to be an advantage, but it is imperative that patients who undergo any bariatric surgical procedure be committed to long-term adherence to postoperative guidelines.

When comparing the risks of surgical complications with the benefits of diabetes remission (and other obesity-related comorbidities), I believe the best option is laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. This procedure is almost as effective as the duodenal switch for resolving diabetes, yet it is safer and is widely available in the United States.

Diabetes remission is often seen prior to significant weight loss in patients who have undergone laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The reason for this has yet to be fully elucidated. There appears to be a multifactorial gut hormone response that is responsible for this metabolic effect, but this theory is still under intense study.

Efficacy of Gastric Bypass for Diabetes Remission

We published a study 2 years ago that documented the efficacy of gastric bypass for diabetes remission. We compared hemoglobin A1c levels for patients who had undergone laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with a group of morbidly obese patients treated with conventional medical therapy.

One year after surgery, 59% of the 46 patients for whom we had follow-up data had experienced full remission (Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2009;5:4-10). They no longer required any diabetic medications, and their hemoglobin A1c was 6% or lower. In contrast, only 2 of the 41 patients (5%) in the conventional medical treatment group experienced remission.

Full remission of diabetes is very difficult to achieve with medications and lifestyle modification. Bariatric surgery – more appropriately termed "metabolic surgery" – presents an unrivaled opportunity for patients with type 2 diabetes to experience full remission. It also often resolves hypertension, lowers hypercholesterolemia, and substantially improves other obesity-related comorbidities, including obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteoarthritis.

The time has come to move away from arbitrary BMI cutoffs and insurance-mandated criteria to determine whether patients with diabetes are candidates for bariatric surgery. The primary determinant should be the severity and duration of the patient’s diabetes and obesity-related comorbidities, and whether a reasonable trial of medical and lifestyle management has failed.

Results from several studies have documented that the cost of bariatric surgery for patients who are not adequately managed by their medical regimen are recouped within 2-4 years by reduced drug costs and reduced costs for managing the complications of poorly controlled diabetes (Am. J. Manag. Care 2008;14:589-96; Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2011 May 27 [doi:10.1016/j.soard.2011.05.009].

Many physicians regard bariatric surgery as dangerous, and it is held to an unreasonably high standard of success. Even though gastric bypass will produce remission in about 60% of patients with diabetes and significant benefits for another 20%-30%, it is criticized for having a 10% failure rate. Many other procedures routinely used in appropriate patients do not work in 100% of patients.

The best success one can expect from a Nissen fundoplication for control of gastroesophageal reflux disease is 85%-90%, a well-established benchmark. Why should the standards for bariatric surgery be set above thresholds we accept for other surgical interventions?

The mortality rates of minimally invasive bariatric surgery rival those of routine operations such as cholecystectomy and hip replacement. The laparoscopic era has led to reduced mortality, fewer surgical site infections, shorter hospitalizations, and faster return to full activity. But because bariatric surgery is delivered by a scalpel and not a pill, it has faced discrimination and resistance within the medical community.

Dr. Kothari is director of the Minimally Invasive Bariatric Surgery Center at Gundersen Lutheran Health System in La Crosse, Wis. He has been a consultant to Covidien, Valley Lab, and Life Cell, and has received research grants from Covidien. This column appears in Internal Medicine News, a publication of Elsevier.

Bariatric Surgery Now 'Safer Than Appendectomy'

ORLANDO – Bariatric surgery achieved an unprecedented level of safety through 2009, as U.S. surgeons mastered the laparoscopic gastric bypass approach and offered patients gastric banding or gastroplasty, based on data collected on more than 100,000 U.S. patients treated at academic medical centers during 2002-2009.

This recent era also ushered in a new list of risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, including two modifiable risk factors: diabetes and the type of surgery used, Dr. Brian R. Smith said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

"We find six preoperative factors that predict mortality. We can’t change patient age, sex, or insurance type, but we can better manage their diabetes preoperatively, and we can change the type of surgery they receive" to minimize their risk, said Dr. Smith, a surgeon at the University of California, Irvine, and chief of general surgery at the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in Long Beach, Calif.

"Bariatric surgery is now statistically safer than appendectomy. Probably the most significant factor is that [surgeons] have gotten better with the laparoscopic approach; we got over the learning curve," he said in an interview.

Dr. Smith and his associates reviewed 105,287 patients who underwent bariatric surgery during 2002-2009 at hospitals that contribute data to the University HealthSystem Consortium, a database of about 360 U.S. academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals. During that period, bariatric surgery volume ranged from about 10,000 cases in 2002 to about 16,000 in 2009.

Through 2003, open gastric bypass was used exclusively but, starting in 2004, surgeons began performing laparoscopic gastric bypass and gastric banding. By 2005, about 60% of the roughly 13,000 bariatric procedures that year involved laparoscopic bypass, with open bypass reduced to less than 20% of the total. During 2009, nearly 70% of bariatric procedures done at hospitals in the consortium were laparoscopic bypasses, about a quarter were banding or gastroplasty, and only about 6% of cases involved open bypass.

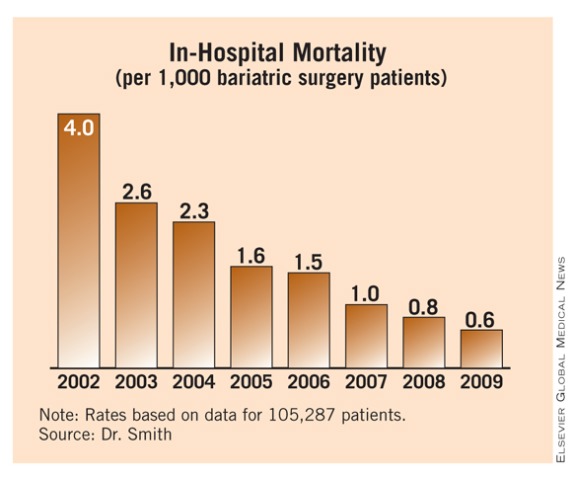

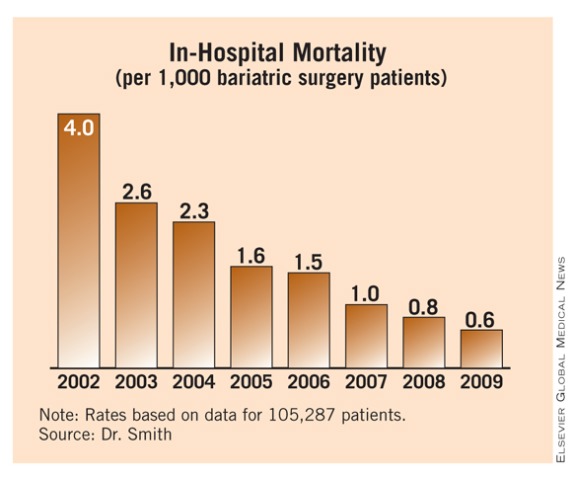

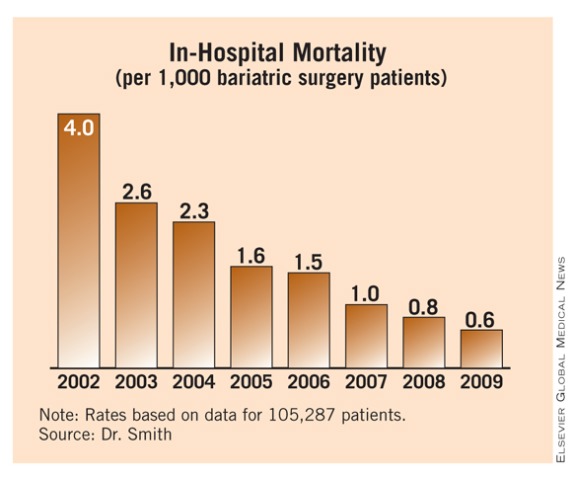

Concurrent with this shift in type of bariatric surgery performed came a striking drop in in-hospital mortality. In 2002, the rate was 4 deaths/1,000 patients. Over the following 7 years, mortality steadily fell and reached a new low of 0.6 deaths/1,000 patients in 2009, Dr. Smith reported.

"It’s a remarkable achievement – an American surgical success story," commented Dr. John M. Morton, director of bariatric surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Morton attributed the sharp decline in mortality to the rapid switch from open to laparoscopic gastric bypass, the focus starting in 2004 on treating bariatric surgery patients at designated centers of excellence, improved clinical pathways, and better patient selection. "We consistently see mortality rates of 0.1%, 0.3%, tops. That makes bariatric surgery as safe as laparoscopic cholecystectomy and hip replacement," he said in an interview.

Dr. Smith agreed that the rapid drop in the number of open gastric bypass procedures starting in 2005 and their replacement by laparoscopic procedures played a major role in the fall in patient mortality during the mid-2000s.

The more than 100,000 patients reviewed by Dr. Smith included 17% who were older than 60 years. About 80% were women and about 73% were white. The prevalence of hypertension was 56%, 30% had diabetes, and 22% had hyperlipidemia. Two-thirds of the patients had private medical insurance coverage.

A multivariate analysis identified six factors linked with an increased mortality risk: age older than 60 years, male sex, Medicare coverage, diabetes, open surgery, and gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes had not previously been identified as a mortality risk in published analyses, and the new list did not include hypertension, which had been a risk factor in prior analyses.

On the basis of these factors, Dr. Smith and his associates developed a mortality risk–scoring formula that assigned 1 point for each of four risk factors – male sex, Medicare insurance, open surgery, and gastric bypass – and 0.5 points for each of the other two factors, age 60 years or older and diabetes. After assigning these point values to the patients in the database, they found that patients with a risk score of 3.5 or greater had a sevenfold increased risk of in-hospital mortality, compared with patients with a score of zero or 0.5.

Dr. Smith said he had no disclosures. Dr. Morton said that he has received an educational grant from Ethicon Endo-Surgery, and he has received honoraria from and served on the scientific advisory board of Vibrynt.

ORLANDO – Bariatric surgery achieved an unprecedented level of safety through 2009, as U.S. surgeons mastered the laparoscopic gastric bypass approach and offered patients gastric banding or gastroplasty, based on data collected on more than 100,000 U.S. patients treated at academic medical centers during 2002-2009.

This recent era also ushered in a new list of risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, including two modifiable risk factors: diabetes and the type of surgery used, Dr. Brian R. Smith said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

"We find six preoperative factors that predict mortality. We can’t change patient age, sex, or insurance type, but we can better manage their diabetes preoperatively, and we can change the type of surgery they receive" to minimize their risk, said Dr. Smith, a surgeon at the University of California, Irvine, and chief of general surgery at the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in Long Beach, Calif.

"Bariatric surgery is now statistically safer than appendectomy. Probably the most significant factor is that [surgeons] have gotten better with the laparoscopic approach; we got over the learning curve," he said in an interview.

Dr. Smith and his associates reviewed 105,287 patients who underwent bariatric surgery during 2002-2009 at hospitals that contribute data to the University HealthSystem Consortium, a database of about 360 U.S. academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals. During that period, bariatric surgery volume ranged from about 10,000 cases in 2002 to about 16,000 in 2009.

Through 2003, open gastric bypass was used exclusively but, starting in 2004, surgeons began performing laparoscopic gastric bypass and gastric banding. By 2005, about 60% of the roughly 13,000 bariatric procedures that year involved laparoscopic bypass, with open bypass reduced to less than 20% of the total. During 2009, nearly 70% of bariatric procedures done at hospitals in the consortium were laparoscopic bypasses, about a quarter were banding or gastroplasty, and only about 6% of cases involved open bypass.

Concurrent with this shift in type of bariatric surgery performed came a striking drop in in-hospital mortality. In 2002, the rate was 4 deaths/1,000 patients. Over the following 7 years, mortality steadily fell and reached a new low of 0.6 deaths/1,000 patients in 2009, Dr. Smith reported.

"It’s a remarkable achievement – an American surgical success story," commented Dr. John M. Morton, director of bariatric surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Morton attributed the sharp decline in mortality to the rapid switch from open to laparoscopic gastric bypass, the focus starting in 2004 on treating bariatric surgery patients at designated centers of excellence, improved clinical pathways, and better patient selection. "We consistently see mortality rates of 0.1%, 0.3%, tops. That makes bariatric surgery as safe as laparoscopic cholecystectomy and hip replacement," he said in an interview.

Dr. Smith agreed that the rapid drop in the number of open gastric bypass procedures starting in 2005 and their replacement by laparoscopic procedures played a major role in the fall in patient mortality during the mid-2000s.

The more than 100,000 patients reviewed by Dr. Smith included 17% who were older than 60 years. About 80% were women and about 73% were white. The prevalence of hypertension was 56%, 30% had diabetes, and 22% had hyperlipidemia. Two-thirds of the patients had private medical insurance coverage.

A multivariate analysis identified six factors linked with an increased mortality risk: age older than 60 years, male sex, Medicare coverage, diabetes, open surgery, and gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes had not previously been identified as a mortality risk in published analyses, and the new list did not include hypertension, which had been a risk factor in prior analyses.

On the basis of these factors, Dr. Smith and his associates developed a mortality risk–scoring formula that assigned 1 point for each of four risk factors – male sex, Medicare insurance, open surgery, and gastric bypass – and 0.5 points for each of the other two factors, age 60 years or older and diabetes. After assigning these point values to the patients in the database, they found that patients with a risk score of 3.5 or greater had a sevenfold increased risk of in-hospital mortality, compared with patients with a score of zero or 0.5.

Dr. Smith said he had no disclosures. Dr. Morton said that he has received an educational grant from Ethicon Endo-Surgery, and he has received honoraria from and served on the scientific advisory board of Vibrynt.

ORLANDO – Bariatric surgery achieved an unprecedented level of safety through 2009, as U.S. surgeons mastered the laparoscopic gastric bypass approach and offered patients gastric banding or gastroplasty, based on data collected on more than 100,000 U.S. patients treated at academic medical centers during 2002-2009.

This recent era also ushered in a new list of risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, including two modifiable risk factors: diabetes and the type of surgery used, Dr. Brian R. Smith said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

"We find six preoperative factors that predict mortality. We can’t change patient age, sex, or insurance type, but we can better manage their diabetes preoperatively, and we can change the type of surgery they receive" to minimize their risk, said Dr. Smith, a surgeon at the University of California, Irvine, and chief of general surgery at the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in Long Beach, Calif.

"Bariatric surgery is now statistically safer than appendectomy. Probably the most significant factor is that [surgeons] have gotten better with the laparoscopic approach; we got over the learning curve," he said in an interview.

Dr. Smith and his associates reviewed 105,287 patients who underwent bariatric surgery during 2002-2009 at hospitals that contribute data to the University HealthSystem Consortium, a database of about 360 U.S. academic medical centers and affiliated hospitals. During that period, bariatric surgery volume ranged from about 10,000 cases in 2002 to about 16,000 in 2009.

Through 2003, open gastric bypass was used exclusively but, starting in 2004, surgeons began performing laparoscopic gastric bypass and gastric banding. By 2005, about 60% of the roughly 13,000 bariatric procedures that year involved laparoscopic bypass, with open bypass reduced to less than 20% of the total. During 2009, nearly 70% of bariatric procedures done at hospitals in the consortium were laparoscopic bypasses, about a quarter were banding or gastroplasty, and only about 6% of cases involved open bypass.

Concurrent with this shift in type of bariatric surgery performed came a striking drop in in-hospital mortality. In 2002, the rate was 4 deaths/1,000 patients. Over the following 7 years, mortality steadily fell and reached a new low of 0.6 deaths/1,000 patients in 2009, Dr. Smith reported.

"It’s a remarkable achievement – an American surgical success story," commented Dr. John M. Morton, director of bariatric surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Morton attributed the sharp decline in mortality to the rapid switch from open to laparoscopic gastric bypass, the focus starting in 2004 on treating bariatric surgery patients at designated centers of excellence, improved clinical pathways, and better patient selection. "We consistently see mortality rates of 0.1%, 0.3%, tops. That makes bariatric surgery as safe as laparoscopic cholecystectomy and hip replacement," he said in an interview.

Dr. Smith agreed that the rapid drop in the number of open gastric bypass procedures starting in 2005 and their replacement by laparoscopic procedures played a major role in the fall in patient mortality during the mid-2000s.

The more than 100,000 patients reviewed by Dr. Smith included 17% who were older than 60 years. About 80% were women and about 73% were white. The prevalence of hypertension was 56%, 30% had diabetes, and 22% had hyperlipidemia. Two-thirds of the patients had private medical insurance coverage.

A multivariate analysis identified six factors linked with an increased mortality risk: age older than 60 years, male sex, Medicare coverage, diabetes, open surgery, and gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes had not previously been identified as a mortality risk in published analyses, and the new list did not include hypertension, which had been a risk factor in prior analyses.

On the basis of these factors, Dr. Smith and his associates developed a mortality risk–scoring formula that assigned 1 point for each of four risk factors – male sex, Medicare insurance, open surgery, and gastric bypass – and 0.5 points for each of the other two factors, age 60 years or older and diabetes. After assigning these point values to the patients in the database, they found that patients with a risk score of 3.5 or greater had a sevenfold increased risk of in-hospital mortality, compared with patients with a score of zero or 0.5.

Dr. Smith said he had no disclosures. Dr. Morton said that he has received an educational grant from Ethicon Endo-Surgery, and he has received honoraria from and served on the scientific advisory board of Vibrynt.

FROM THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR METABOLIC AND BARIATRIC SURGERY ANNUAL MEETING

Major Finding: During 2009, bariatric surgery done at U.S. academic hospitals had an in-hospital mortality rate of 0.6/1,000 patients, compared with a rate of 4/1,000 cases in 2002.

Data Source: Review of 105,287 patients undergoing bariatric surgery at U.S. hospitals participating in the University Health Consortium.

Disclosures: Dr. Smith said he had no disclosures. Dr. Morton said that he has received an educational grant from Ethicon Endo-Surgery, and he has received honoraria from and served on the scientific advisory board of Vibrynt.

Bariatric Surgery Cuts Mortality, MIs, and Strokes in Morbidly Obese

ORLANDO – Patients undergoing bariatric surgery had a significantly reduced rate of subsequent myocardial infarctions and strokes and significantly increased survival, compared with similar, morbidly obese patients who had other types of surgery, in a retrospective cohort study of more than 9,000 U.S. patients.

The results "add to the growing evidence that bariatric surgery plays a role in temporizing the risk factors for major cardiovascular events. We believe our analysis builds on prior reports and takes them a step further by evaluating actual events," Dr. John D. Scott said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

In his study of bariatric surgery patients in South Carolina during 1996-2008, the combined rate of MIs, strokes, and deaths was 52% below the rate in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery, and 28% below the rate of those who had orthopedic surgery – both statistically significant differences. The results also showed significant drops in each component of the combined end point (MIs, strokes, and deaths).

"Previous literature demonstrated that cardiovascular risk declined after bariatric surgery. What this study did was look at the rate of actual cardiovascular events, which significantly declined after bariatric surgery," said Dr. Scott, a bariatric surgeon at University Medical Center Greenville (S.C.) Hospital System.

The new study used hospital in-patient records collected during 1996-2008 through the South Carolina Office of Research and Statistics, and death data collected by the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. The analysis included morbidly obese patients aged 40-79 years who underwent nonemergency surgery (4,747 patients who had any form of bariatric surgery, 3,066 patients who underwent joint replacement or spinal surgery, and 1,327 patients who had a cholecystectomy, hernia repair, or lysis of gastrointestinal adhesions). Those with a history of prior MI or stroke were excluded.

Patients were followed for an average of 14 months after bariatric surgery, 25 after orthopedic surgery, and 26 months after gastrointestinal surgery.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for age, sex, race, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, coronary artery disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and a history of transient ischemic attack, patients undergoing bariatric surgery had a significant 41% reduced rate of first MI compared with the orthopedic surgery patients, and a significant 51% lower rate compared with the gastrointestinal surgery patients.

Mortality in the bariatric surgery patients dropped by a significant 19% and 55% relative to the orthopedic and gastrointestinal patients, respectively, and the stroke rate was also significantly lower following bariatric surgery compared with the rates in each control group. The magnitude of these event-rate reductions was consistent with prior reports of risk reduction, Dr. Scott said.

Notably, bariatric surgery "reduced cardiovascular events, as opposed to obesity-drug treatments that may actually increase the risk for cardiovascular events," he noted. "Bariatric surgery has been rigorously tested and [proved] over the past 20 years, and it has a dramatic effect on all aspects of patient health. [Most] medical treatments for obesity don’t have 20 years of data, and some medications actually cause heart problems. We don’t know how bariatric surgery reduced myocardial infarctions and strokes, but it’s probably several factors: weight loss and resolution of diabetes, hypertension, and sleep apnea. The spectrum of returning patients to a more normal, baseline state probably leads to less morbidity and mortality," Dr. Scott said.

Dr. Scott said that he has been a speaker for Gore.

Dr. Scott and his associates have attempted to address a quintessential question about bariatric surgery: Does it reduce the long-term mortality associated with obesity? About 10 prior reports in the literature have also attempted to address this, including one published in the same week that Dr. Scott presented his findings (JAMA 2011;305:2419-26). All of these studies have weaknesses, mostly involving the control group. Because nonsurgical patients who received medical management typically are used as the control group, this often raises the question of whether the control patients were sicker than the surgical patients.

Dr. Scott’s study avoided this weakness by comparing bariatric surgery patients with other surgery patients. This eliminated the bias of greater sickness, as all patients in the study were healthy enough to undergo elective surgery. It also eliminated any bias stemming from access to surgical and medical care.

Despite this, the bariatric surgery and control groups differed in demographics and comorbidities. It seems as though the between-group differences were too extensive to allow for adequate adjustment by a multivariate analysis. In addition, the study included no information on body mass index, so no adjustment was possible for this variable.

I believe the impact of bariatric surgery can only be reliably tested in a randomized, controlled trial. The biases embedded in databases cannot be fully eliminated; the only way to address this question objectively is with a randomized trial.

Philip Schauer, M.D., is director of the bariatric and metabolic institute at the Cleveland Clinic. He made these comments as the designated discussant of Dr. Scott’s paper. He said that he has received teaching grants from Allergan and Covidien; consulting fees as a member of the advisory board of and research support from Bard/Davol and Ethicon Endo-Surgery; consulting fees from Baxter Healthcare, Cardinal Health, and Stryker Endoscopy; and support from RemedyMD.

Dr. Scott and his associates have attempted to address a quintessential question about bariatric surgery: Does it reduce the long-term mortality associated with obesity? About 10 prior reports in the literature have also attempted to address this, including one published in the same week that Dr. Scott presented his findings (JAMA 2011;305:2419-26). All of these studies have weaknesses, mostly involving the control group. Because nonsurgical patients who received medical management typically are used as the control group, this often raises the question of whether the control patients were sicker than the surgical patients.

Dr. Scott’s study avoided this weakness by comparing bariatric surgery patients with other surgery patients. This eliminated the bias of greater sickness, as all patients in the study were healthy enough to undergo elective surgery. It also eliminated any bias stemming from access to surgical and medical care.

Despite this, the bariatric surgery and control groups differed in demographics and comorbidities. It seems as though the between-group differences were too extensive to allow for adequate adjustment by a multivariate analysis. In addition, the study included no information on body mass index, so no adjustment was possible for this variable.

I believe the impact of bariatric surgery can only be reliably tested in a randomized, controlled trial. The biases embedded in databases cannot be fully eliminated; the only way to address this question objectively is with a randomized trial.

Philip Schauer, M.D., is director of the bariatric and metabolic institute at the Cleveland Clinic. He made these comments as the designated discussant of Dr. Scott’s paper. He said that he has received teaching grants from Allergan and Covidien; consulting fees as a member of the advisory board of and research support from Bard/Davol and Ethicon Endo-Surgery; consulting fees from Baxter Healthcare, Cardinal Health, and Stryker Endoscopy; and support from RemedyMD.

Dr. Scott and his associates have attempted to address a quintessential question about bariatric surgery: Does it reduce the long-term mortality associated with obesity? About 10 prior reports in the literature have also attempted to address this, including one published in the same week that Dr. Scott presented his findings (JAMA 2011;305:2419-26). All of these studies have weaknesses, mostly involving the control group. Because nonsurgical patients who received medical management typically are used as the control group, this often raises the question of whether the control patients were sicker than the surgical patients.

Dr. Scott’s study avoided this weakness by comparing bariatric surgery patients with other surgery patients. This eliminated the bias of greater sickness, as all patients in the study were healthy enough to undergo elective surgery. It also eliminated any bias stemming from access to surgical and medical care.

Despite this, the bariatric surgery and control groups differed in demographics and comorbidities. It seems as though the between-group differences were too extensive to allow for adequate adjustment by a multivariate analysis. In addition, the study included no information on body mass index, so no adjustment was possible for this variable.

I believe the impact of bariatric surgery can only be reliably tested in a randomized, controlled trial. The biases embedded in databases cannot be fully eliminated; the only way to address this question objectively is with a randomized trial.

Philip Schauer, M.D., is director of the bariatric and metabolic institute at the Cleveland Clinic. He made these comments as the designated discussant of Dr. Scott’s paper. He said that he has received teaching grants from Allergan and Covidien; consulting fees as a member of the advisory board of and research support from Bard/Davol and Ethicon Endo-Surgery; consulting fees from Baxter Healthcare, Cardinal Health, and Stryker Endoscopy; and support from RemedyMD.

ORLANDO – Patients undergoing bariatric surgery had a significantly reduced rate of subsequent myocardial infarctions and strokes and significantly increased survival, compared with similar, morbidly obese patients who had other types of surgery, in a retrospective cohort study of more than 9,000 U.S. patients.

The results "add to the growing evidence that bariatric surgery plays a role in temporizing the risk factors for major cardiovascular events. We believe our analysis builds on prior reports and takes them a step further by evaluating actual events," Dr. John D. Scott said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

In his study of bariatric surgery patients in South Carolina during 1996-2008, the combined rate of MIs, strokes, and deaths was 52% below the rate in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery, and 28% below the rate of those who had orthopedic surgery – both statistically significant differences. The results also showed significant drops in each component of the combined end point (MIs, strokes, and deaths).

"Previous literature demonstrated that cardiovascular risk declined after bariatric surgery. What this study did was look at the rate of actual cardiovascular events, which significantly declined after bariatric surgery," said Dr. Scott, a bariatric surgeon at University Medical Center Greenville (S.C.) Hospital System.

The new study used hospital in-patient records collected during 1996-2008 through the South Carolina Office of Research and Statistics, and death data collected by the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. The analysis included morbidly obese patients aged 40-79 years who underwent nonemergency surgery (4,747 patients who had any form of bariatric surgery, 3,066 patients who underwent joint replacement or spinal surgery, and 1,327 patients who had a cholecystectomy, hernia repair, or lysis of gastrointestinal adhesions). Those with a history of prior MI or stroke were excluded.

Patients were followed for an average of 14 months after bariatric surgery, 25 after orthopedic surgery, and 26 months after gastrointestinal surgery.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for age, sex, race, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, coronary artery disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and a history of transient ischemic attack, patients undergoing bariatric surgery had a significant 41% reduced rate of first MI compared with the orthopedic surgery patients, and a significant 51% lower rate compared with the gastrointestinal surgery patients.

Mortality in the bariatric surgery patients dropped by a significant 19% and 55% relative to the orthopedic and gastrointestinal patients, respectively, and the stroke rate was also significantly lower following bariatric surgery compared with the rates in each control group. The magnitude of these event-rate reductions was consistent with prior reports of risk reduction, Dr. Scott said.

Notably, bariatric surgery "reduced cardiovascular events, as opposed to obesity-drug treatments that may actually increase the risk for cardiovascular events," he noted. "Bariatric surgery has been rigorously tested and [proved] over the past 20 years, and it has a dramatic effect on all aspects of patient health. [Most] medical treatments for obesity don’t have 20 years of data, and some medications actually cause heart problems. We don’t know how bariatric surgery reduced myocardial infarctions and strokes, but it’s probably several factors: weight loss and resolution of diabetes, hypertension, and sleep apnea. The spectrum of returning patients to a more normal, baseline state probably leads to less morbidity and mortality," Dr. Scott said.

Dr. Scott said that he has been a speaker for Gore.

ORLANDO – Patients undergoing bariatric surgery had a significantly reduced rate of subsequent myocardial infarctions and strokes and significantly increased survival, compared with similar, morbidly obese patients who had other types of surgery, in a retrospective cohort study of more than 9,000 U.S. patients.

The results "add to the growing evidence that bariatric surgery plays a role in temporizing the risk factors for major cardiovascular events. We believe our analysis builds on prior reports and takes them a step further by evaluating actual events," Dr. John D. Scott said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

In his study of bariatric surgery patients in South Carolina during 1996-2008, the combined rate of MIs, strokes, and deaths was 52% below the rate in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery, and 28% below the rate of those who had orthopedic surgery – both statistically significant differences. The results also showed significant drops in each component of the combined end point (MIs, strokes, and deaths).

"Previous literature demonstrated that cardiovascular risk declined after bariatric surgery. What this study did was look at the rate of actual cardiovascular events, which significantly declined after bariatric surgery," said Dr. Scott, a bariatric surgeon at University Medical Center Greenville (S.C.) Hospital System.

The new study used hospital in-patient records collected during 1996-2008 through the South Carolina Office of Research and Statistics, and death data collected by the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. The analysis included morbidly obese patients aged 40-79 years who underwent nonemergency surgery (4,747 patients who had any form of bariatric surgery, 3,066 patients who underwent joint replacement or spinal surgery, and 1,327 patients who had a cholecystectomy, hernia repair, or lysis of gastrointestinal adhesions). Those with a history of prior MI or stroke were excluded.

Patients were followed for an average of 14 months after bariatric surgery, 25 after orthopedic surgery, and 26 months after gastrointestinal surgery.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for age, sex, race, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, coronary artery disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and a history of transient ischemic attack, patients undergoing bariatric surgery had a significant 41% reduced rate of first MI compared with the orthopedic surgery patients, and a significant 51% lower rate compared with the gastrointestinal surgery patients.

Mortality in the bariatric surgery patients dropped by a significant 19% and 55% relative to the orthopedic and gastrointestinal patients, respectively, and the stroke rate was also significantly lower following bariatric surgery compared with the rates in each control group. The magnitude of these event-rate reductions was consistent with prior reports of risk reduction, Dr. Scott said.

Notably, bariatric surgery "reduced cardiovascular events, as opposed to obesity-drug treatments that may actually increase the risk for cardiovascular events," he noted. "Bariatric surgery has been rigorously tested and [proved] over the past 20 years, and it has a dramatic effect on all aspects of patient health. [Most] medical treatments for obesity don’t have 20 years of data, and some medications actually cause heart problems. We don’t know how bariatric surgery reduced myocardial infarctions and strokes, but it’s probably several factors: weight loss and resolution of diabetes, hypertension, and sleep apnea. The spectrum of returning patients to a more normal, baseline state probably leads to less morbidity and mortality," Dr. Scott said.

Dr. Scott said that he has been a speaker for Gore.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR METABOLIC AND BARIATRIC SURGERY

Major Finding: Bariatric surgery patients had a statistically significant 28% reduced relative rate of death, MI, or stroke, compared with orthopedic surgery patients, and a significant 52% reduced relative rate of these end points, compared with gastrointestinal surgery patients, in an adjusted multivariate analysis.

Data Source: Retrospective cohort study of 9,140 morbidly obese patients who underwent elective bariatric, orthopedic, or gastrointestinal surgery in South Carolina during 1996-2008.

Disclosures: Dr. Scott said that he has been a speaker for Gore.

Society Defers Statement on Gastric Bands in Class I Obesity

ORLANDO – The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has opted to defer making recommendations on the use of the laparoscopically placed gastric band for class I obesity patients, according to Dr. Stacy A. Brethauer at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The stage was set for the position statement after the Food and Drug Administration’s approval last February of a laparoscopically placed gastric band for patients with class I obesity and a related comorbidity. The society opted to wait, pending availability of level I evidence on the safety and efficacy of at least one alternative surgical option, such as laparoscopic gastric bypass.

"We decided to wait until we had adequate data on at least the bypass," which should take about another 2 years, given the status of controlled trials now in progress, he said. Safety and efficacy data from randomized, controlled trials of the gastrectomy sleeve will likely take even longer, he added.

"We could issue a statement based just on the band data. There are enough data to say that it’s safe and effective. The FDA has spoken, and approved bands for patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30- 34 kg/m2 and at least one obesity-related comorbidity. But the society’s committee seeks to produce a broader assessment of the treatment options, said Dr. Brethauer, a surgeon in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic.

His committee’s decision to wait parallels the slow approach that Dr. Brethauer and many of his colleagues have taken on placing bands in the expanded patient population following the agency’s decision last February. This cautious approach reflects both medical insurance coverage issues, and the skeptical view of bariatric surgery that many physicians still have, which limits patient referrals.

Despite the FDA’s action, class I obesity patients with an obesity-related comorbidity generally still do not receive insurance coverage for band placement, so the only patients of this type getting bands are those who pay for the procedure themselves. "At the Cleveland Clinic, about 5% of our practice is self-pay. We don’t see many patients who say, ‘I have a BMI of 33 [kg/m2], here is $15,000, please put in a band.’ That may happen elsewhere, but not in our practice," Dr. Brethauer said in an interview.

Also, "primary care physicians ... still see bariatric surgery as carrying a lot of risk, even for patients with a BMI of more than 35." As a result, most patients Dr. Brethauer sees about bariatric surgery are self-referred or sent by endocrinologists.

At least some endocrinologists "have realized that there are benefits to patients from bariatric surgery that they can’t offer. The endocrinologists will be the [linchpin] for changing the paradigm and for getting patients in for surgery sooner. The primary care physicians will hopefully follow. Our job [as bariatric surgeons] is to give [these physicians] the evidence so that they can feel comfortable making referrals. Right now, we only see patients with a BMI of 30-35 for entry into trials. We work with endocrinologists" as co-principal investigators of studies in this BMI group.

"The FDA’s approval of bands for these patients was based on evidence, but many physicians either don’t believe the evidence or don’t pay attention to it. There has been strong evidence to support bariatric surgery for treating diabetes in patients with BMIs of 35 or higher for decades, but some physicians still don’t believe it. It’s an ongoing challenge to convince physicians that for most patients it’s a low-risk surgery that gives a high benefit."

Dr. Brethauer said that he has received consulting fees from Bard/Davol, Baxter Healthcare, Cardinal Health, Ethicon Endo- Surgery, and Stryker Endoscopy. He also has received honoraria and served on an advisory committee for Ethicon Endo-Surgery, has been a proctor for Bard/Davol, and had received teaching honoraria from Covidien.

ORLANDO – The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has opted to defer making recommendations on the use of the laparoscopically placed gastric band for class I obesity patients, according to Dr. Stacy A. Brethauer at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The stage was set for the position statement after the Food and Drug Administration’s approval last February of a laparoscopically placed gastric band for patients with class I obesity and a related comorbidity. The society opted to wait, pending availability of level I evidence on the safety and efficacy of at least one alternative surgical option, such as laparoscopic gastric bypass.

"We decided to wait until we had adequate data on at least the bypass," which should take about another 2 years, given the status of controlled trials now in progress, he said. Safety and efficacy data from randomized, controlled trials of the gastrectomy sleeve will likely take even longer, he added.

"We could issue a statement based just on the band data. There are enough data to say that it’s safe and effective. The FDA has spoken, and approved bands for patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30- 34 kg/m2 and at least one obesity-related comorbidity. But the society’s committee seeks to produce a broader assessment of the treatment options, said Dr. Brethauer, a surgeon in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic.

His committee’s decision to wait parallels the slow approach that Dr. Brethauer and many of his colleagues have taken on placing bands in the expanded patient population following the agency’s decision last February. This cautious approach reflects both medical insurance coverage issues, and the skeptical view of bariatric surgery that many physicians still have, which limits patient referrals.

Despite the FDA’s action, class I obesity patients with an obesity-related comorbidity generally still do not receive insurance coverage for band placement, so the only patients of this type getting bands are those who pay for the procedure themselves. "At the Cleveland Clinic, about 5% of our practice is self-pay. We don’t see many patients who say, ‘I have a BMI of 33 [kg/m2], here is $15,000, please put in a band.’ That may happen elsewhere, but not in our practice," Dr. Brethauer said in an interview.

Also, "primary care physicians ... still see bariatric surgery as carrying a lot of risk, even for patients with a BMI of more than 35." As a result, most patients Dr. Brethauer sees about bariatric surgery are self-referred or sent by endocrinologists.

At least some endocrinologists "have realized that there are benefits to patients from bariatric surgery that they can’t offer. The endocrinologists will be the [linchpin] for changing the paradigm and for getting patients in for surgery sooner. The primary care physicians will hopefully follow. Our job [as bariatric surgeons] is to give [these physicians] the evidence so that they can feel comfortable making referrals. Right now, we only see patients with a BMI of 30-35 for entry into trials. We work with endocrinologists" as co-principal investigators of studies in this BMI group.

"The FDA’s approval of bands for these patients was based on evidence, but many physicians either don’t believe the evidence or don’t pay attention to it. There has been strong evidence to support bariatric surgery for treating diabetes in patients with BMIs of 35 or higher for decades, but some physicians still don’t believe it. It’s an ongoing challenge to convince physicians that for most patients it’s a low-risk surgery that gives a high benefit."

Dr. Brethauer said that he has received consulting fees from Bard/Davol, Baxter Healthcare, Cardinal Health, Ethicon Endo- Surgery, and Stryker Endoscopy. He also has received honoraria and served on an advisory committee for Ethicon Endo-Surgery, has been a proctor for Bard/Davol, and had received teaching honoraria from Covidien.

ORLANDO – The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has opted to defer making recommendations on the use of the laparoscopically placed gastric band for class I obesity patients, according to Dr. Stacy A. Brethauer at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The stage was set for the position statement after the Food and Drug Administration’s approval last February of a laparoscopically placed gastric band for patients with class I obesity and a related comorbidity. The society opted to wait, pending availability of level I evidence on the safety and efficacy of at least one alternative surgical option, such as laparoscopic gastric bypass.

"We decided to wait until we had adequate data on at least the bypass," which should take about another 2 years, given the status of controlled trials now in progress, he said. Safety and efficacy data from randomized, controlled trials of the gastrectomy sleeve will likely take even longer, he added.

"We could issue a statement based just on the band data. There are enough data to say that it’s safe and effective. The FDA has spoken, and approved bands for patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30- 34 kg/m2 and at least one obesity-related comorbidity. But the society’s committee seeks to produce a broader assessment of the treatment options, said Dr. Brethauer, a surgeon in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic.

His committee’s decision to wait parallels the slow approach that Dr. Brethauer and many of his colleagues have taken on placing bands in the expanded patient population following the agency’s decision last February. This cautious approach reflects both medical insurance coverage issues, and the skeptical view of bariatric surgery that many physicians still have, which limits patient referrals.

Despite the FDA’s action, class I obesity patients with an obesity-related comorbidity generally still do not receive insurance coverage for band placement, so the only patients of this type getting bands are those who pay for the procedure themselves. "At the Cleveland Clinic, about 5% of our practice is self-pay. We don’t see many patients who say, ‘I have a BMI of 33 [kg/m2], here is $15,000, please put in a band.’ That may happen elsewhere, but not in our practice," Dr. Brethauer said in an interview.

Also, "primary care physicians ... still see bariatric surgery as carrying a lot of risk, even for patients with a BMI of more than 35." As a result, most patients Dr. Brethauer sees about bariatric surgery are self-referred or sent by endocrinologists.

At least some endocrinologists "have realized that there are benefits to patients from bariatric surgery that they can’t offer. The endocrinologists will be the [linchpin] for changing the paradigm and for getting patients in for surgery sooner. The primary care physicians will hopefully follow. Our job [as bariatric surgeons] is to give [these physicians] the evidence so that they can feel comfortable making referrals. Right now, we only see patients with a BMI of 30-35 for entry into trials. We work with endocrinologists" as co-principal investigators of studies in this BMI group.

"The FDA’s approval of bands for these patients was based on evidence, but many physicians either don’t believe the evidence or don’t pay attention to it. There has been strong evidence to support bariatric surgery for treating diabetes in patients with BMIs of 35 or higher for decades, but some physicians still don’t believe it. It’s an ongoing challenge to convince physicians that for most patients it’s a low-risk surgery that gives a high benefit."

Dr. Brethauer said that he has received consulting fees from Bard/Davol, Baxter Healthcare, Cardinal Health, Ethicon Endo- Surgery, and Stryker Endoscopy. He also has received honoraria and served on an advisory committee for Ethicon Endo-Surgery, has been a proctor for Bard/Davol, and had received teaching honoraria from Covidien.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR METABOLIC AND BARIATRIC SURGERY ANNUAL MEETING

Society Defers Statement on Gastric Bands in Class I Obesity

ORLANDO – The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has opted to defer making recommendations on the use of the laparoscopically placed gastric band for class I obesity patients, according to Dr. Stacy A. Brethauer at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The stage was set for the position statement after the Food and Drug Administration’s approval last February of a laparoscopically placed gastric band for patients with class I obesity and a related comorbidity. The society opted to wait, pending availability of level I evidence on the safety and efficacy of at least one alternative surgical option, such as laparoscopic gastric bypass.

"We decided to wait until we had adequate data on at least the bypass," which should take about another 2 years, given the status of controlled trials now in progress, he said. Safety and efficacy data from randomized, controlled trials of the gastrectomy sleeve will likely take even longer, he added.

"We could issue a statement based just on the band data. There are enough data to say that it’s safe and effective. The FDA has spoken, and approved bands for patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30- 34 kg/m2 and at least one obesity-related comorbidity. But the society’s committee seeks to produce a broader assessment of the treatment options, said Dr. Brethauer, a surgeon in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic.

His committee’s decision to wait parallels the slow approach that Dr. Brethauer and many of his colleagues have taken on placing bands in the expanded patient population following the agency’s decision last February. This cautious approach reflects both medical insurance coverage issues, and the skeptical view of bariatric surgery that many physicians still have, which limits patient referrals.

Despite the FDA’s action, class I obesity patients with an obesity-related comorbidity generally still do not receive insurance coverage for band placement, so the only patients of this type getting bands are those who pay for the procedure themselves. "At the Cleveland Clinic, about 5% of our practice is self-pay. We don’t see many patients who say, ‘I have a BMI of 33 [kg/m2], here is $15,000, please put in a band.’ That may happen elsewhere, but not in our practice," Dr. Brethauer said in an interview.

Also, "primary care physicians ... still see bariatric surgery as carrying a lot of risk, even for patients with a BMI of more than 35." As a result, most patients Dr. Brethauer sees about bariatric surgery are self-referred or sent by endocrinologists.

At least some endocrinologists "have realized that there are benefits to patients from bariatric surgery that they can’t offer. The endocrinologists will be the [linchpin] for changing the paradigm and for getting patients in for surgery sooner. The primary care physicians will hopefully follow. Our job [as bariatric surgeons] is to give [these physicians] the evidence so that they can feel comfortable making referrals. Right now, we only see patients with a BMI of 30-35 for entry into trials. We work with endocrinologists" as co-principal investigators of studies in this BMI group.

"The FDA’s approval of bands for these patients was based on evidence, but many physicians either don’t believe the evidence or don’t pay attention to it. There has been strong evidence to support bariatric surgery for treating diabetes in patients with BMIs of 35 or higher for decades, but some physicians still don’t believe it. It’s an ongoing challenge to convince physicians that for most patients it’s a low-risk surgery that gives a high benefit."

Dr. Brethauer said that he has received consulting fees from Bard/Davol, Baxter Healthcare, Cardinal Health, Ethicon Endo- Surgery, and Stryker Endoscopy. He also has received honoraria and served on an advisory committee for Ethicon Endo-Surgery, has been a proctor for Bard/Davol, and had received teaching honoraria from Covidien.

ORLANDO – The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has opted to defer making recommendations on the use of the laparoscopically placed gastric band for class I obesity patients, according to Dr. Stacy A. Brethauer at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The stage was set for the position statement after the Food and Drug Administration’s approval last February of a laparoscopically placed gastric band for patients with class I obesity and a related comorbidity. The society opted to wait, pending availability of level I evidence on the safety and efficacy of at least one alternative surgical option, such as laparoscopic gastric bypass.

"We decided to wait until we had adequate data on at least the bypass," which should take about another 2 years, given the status of controlled trials now in progress, he said. Safety and efficacy data from randomized, controlled trials of the gastrectomy sleeve will likely take even longer, he added.

"We could issue a statement based just on the band data. There are enough data to say that it’s safe and effective. The FDA has spoken, and approved bands for patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30- 34 kg/m2 and at least one obesity-related comorbidity. But the society’s committee seeks to produce a broader assessment of the treatment options, said Dr. Brethauer, a surgeon in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic.

His committee’s decision to wait parallels the slow approach that Dr. Brethauer and many of his colleagues have taken on placing bands in the expanded patient population following the agency’s decision last February. This cautious approach reflects both medical insurance coverage issues, and the skeptical view of bariatric surgery that many physicians still have, which limits patient referrals.

Despite the FDA’s action, class I obesity patients with an obesity-related comorbidity generally still do not receive insurance coverage for band placement, so the only patients of this type getting bands are those who pay for the procedure themselves. "At the Cleveland Clinic, about 5% of our practice is self-pay. We don’t see many patients who say, ‘I have a BMI of 33 [kg/m2], here is $15,000, please put in a band.’ That may happen elsewhere, but not in our practice," Dr. Brethauer said in an interview.

Also, "primary care physicians ... still see bariatric surgery as carrying a lot of risk, even for patients with a BMI of more than 35." As a result, most patients Dr. Brethauer sees about bariatric surgery are self-referred or sent by endocrinologists.

At least some endocrinologists "have realized that there are benefits to patients from bariatric surgery that they can’t offer. The endocrinologists will be the [linchpin] for changing the paradigm and for getting patients in for surgery sooner. The primary care physicians will hopefully follow. Our job [as bariatric surgeons] is to give [these physicians] the evidence so that they can feel comfortable making referrals. Right now, we only see patients with a BMI of 30-35 for entry into trials. We work with endocrinologists" as co-principal investigators of studies in this BMI group.

"The FDA’s approval of bands for these patients was based on evidence, but many physicians either don’t believe the evidence or don’t pay attention to it. There has been strong evidence to support bariatric surgery for treating diabetes in patients with BMIs of 35 or higher for decades, but some physicians still don’t believe it. It’s an ongoing challenge to convince physicians that for most patients it’s a low-risk surgery that gives a high benefit."

Dr. Brethauer said that he has received consulting fees from Bard/Davol, Baxter Healthcare, Cardinal Health, Ethicon Endo- Surgery, and Stryker Endoscopy. He also has received honoraria and served on an advisory committee for Ethicon Endo-Surgery, has been a proctor for Bard/Davol, and had received teaching honoraria from Covidien.

ORLANDO – The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has opted to defer making recommendations on the use of the laparoscopically placed gastric band for class I obesity patients, according to Dr. Stacy A. Brethauer at the annual meeting of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The stage was set for the position statement after the Food and Drug Administration’s approval last February of a laparoscopically placed gastric band for patients with class I obesity and a related comorbidity. The society opted to wait, pending availability of level I evidence on the safety and efficacy of at least one alternative surgical option, such as laparoscopic gastric bypass.

"We decided to wait until we had adequate data on at least the bypass," which should take about another 2 years, given the status of controlled trials now in progress, he said. Safety and efficacy data from randomized, controlled trials of the gastrectomy sleeve will likely take even longer, he added.

"We could issue a statement based just on the band data. There are enough data to say that it’s safe and effective. The FDA has spoken, and approved bands for patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30- 34 kg/m2 and at least one obesity-related comorbidity. But the society’s committee seeks to produce a broader assessment of the treatment options, said Dr. Brethauer, a surgeon in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute of the Cleveland Clinic.

His committee’s decision to wait parallels the slow approach that Dr. Brethauer and many of his colleagues have taken on placing bands in the expanded patient population following the agency’s decision last February. This cautious approach reflects both medical insurance coverage issues, and the skeptical view of bariatric surgery that many physicians still have, which limits patient referrals.

Despite the FDA’s action, class I obesity patients with an obesity-related comorbidity generally still do not receive insurance coverage for band placement, so the only patients of this type getting bands are those who pay for the procedure themselves. "At the Cleveland Clinic, about 5% of our practice is self-pay. We don’t see many patients who say, ‘I have a BMI of 33 [kg/m2], here is $15,000, please put in a band.’ That may happen elsewhere, but not in our practice," Dr. Brethauer said in an interview.

Also, "primary care physicians ... still see bariatric surgery as carrying a lot of risk, even for patients with a BMI of more than 35." As a result, most patients Dr. Brethauer sees about bariatric surgery are self-referred or sent by endocrinologists.

At least some endocrinologists "have realized that there are benefits to patients from bariatric surgery that they can’t offer. The endocrinologists will be the [linchpin] for changing the paradigm and for getting patients in for surgery sooner. The primary care physicians will hopefully follow. Our job [as bariatric surgeons] is to give [these physicians] the evidence so that they can feel comfortable making referrals. Right now, we only see patients with a BMI of 30-35 for entry into trials. We work with endocrinologists" as co-principal investigators of studies in this BMI group.

"The FDA’s approval of bands for these patients was based on evidence, but many physicians either don’t believe the evidence or don’t pay attention to it. There has been strong evidence to support bariatric surgery for treating diabetes in patients with BMIs of 35 or higher for decades, but some physicians still don’t believe it. It’s an ongoing challenge to convince physicians that for most patients it’s a low-risk surgery that gives a high benefit."

Dr. Brethauer said that he has received consulting fees from Bard/Davol, Baxter Healthcare, Cardinal Health, Ethicon Endo- Surgery, and Stryker Endoscopy. He also has received honoraria and served on an advisory committee for Ethicon Endo-Surgery, has been a proctor for Bard/Davol, and had received teaching honoraria from Covidien.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR METABOLIC AND BARIATRIC SURGERY ANNUAL MEETING

Gastric Sleeve Results Good at 12 Months

ORLANDO – Endoscopic placement of a gastric-jejunal bypass sleeve led to significant weight loss and improvements in diabetes and other comorbidities in a pilot study with 24 patients who had the sleeve in place for up to 1 year.

Endoscopic insertion of the bypass sleeve in these 24 patients involved laparoscopic assistance. Future refinements may eliminate the laparoscopic step and permit a fully nonsurgical approach to gastric bypass, Dr. Bryan J. Sandler said at the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery annual meeting. Further study is needed to determine the experience with a larger number of patients and to examine their experience over time, added Dr. Sandler, a bariatric surgeon at the University of California, San Diego.

"It’s a really exciting technology," commented Dr. Aurora D. Pryor, a surgeon in the Center for Metabolic and Weight Loss Surgery at Duke University in Durham, N.C. "It potentially expands the kind of patient in whom you could use this treatment, including bigger, high-risk patients, and possibly also patients with diabetes and a lower body mass index. I would like to see longer-term studies and have them see if they can still successfully exchange the sleeve, but if they can do it successfully long term, then it would be a very innovative solution," she said in an interview.

The study included 24 patients who averaged 40 years old, 71% of whom were women, with an average body mass index of 42 kg/m2, with a range of 35-51 kg/m2. Twelve patients received a bypass sleeve with a planned explant time of 3 months, and another 12 patients received a sleeve with planned explant time of 12 months. The researchers treated patients at San José Hospital Tec de Monterrey (Mexico).

The surgeons placed the top end of the polyurethane sleeve at the gastroesophageal junction and the bottom end into the jejunum, so that food bypassed most of the stomach and duodenum. The sleeve both restricts food intake and works as a food bypass, mimicking the effect of a surgical Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, Dr. Sandler said.