User login

Biomarker predicts prolonged depression in breast cancer patients

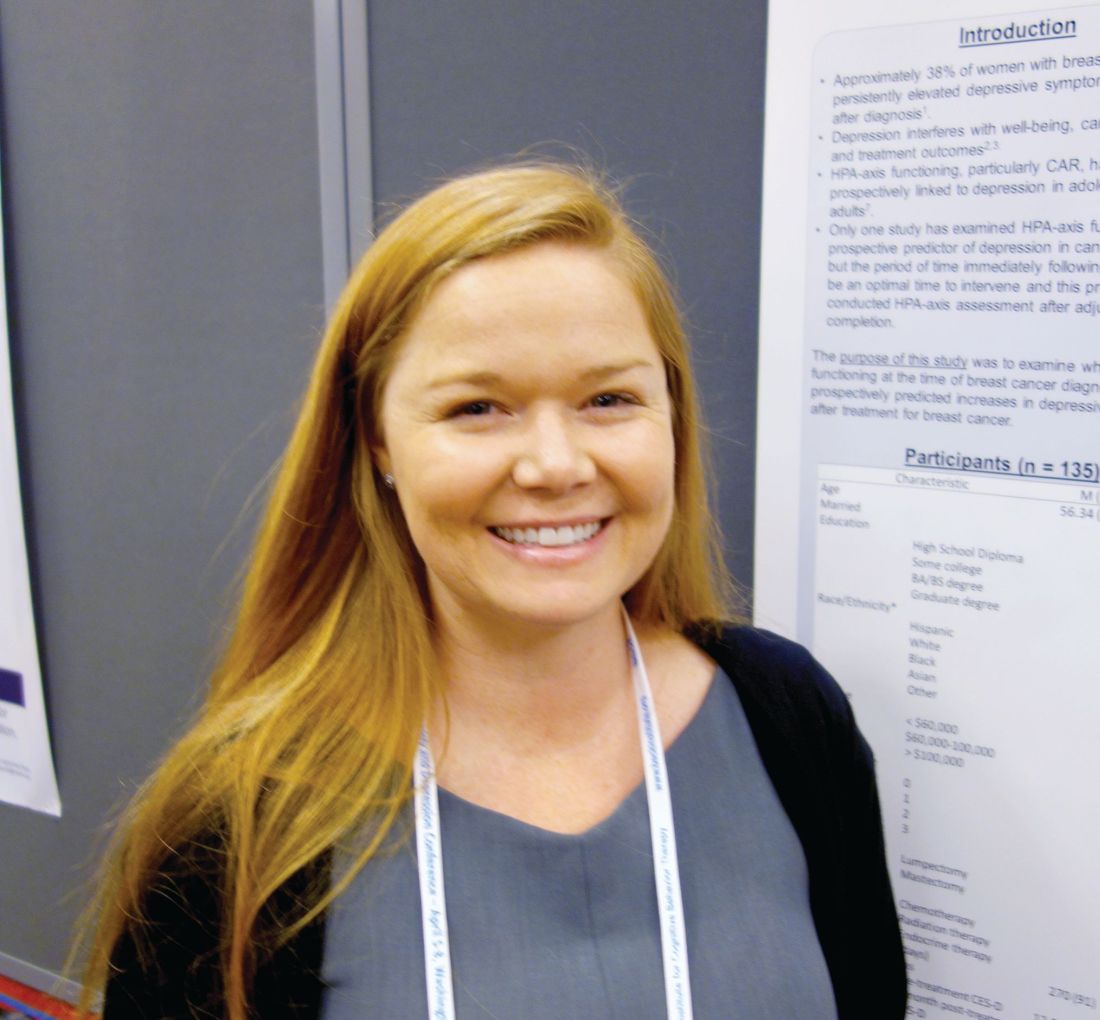

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly 40% of breast cancer patients experience prolonged depression lasting for at least 16 months after diagnosis of their malignancy; those at increased risk may be identifiable in a timely way by their exaggerated cortisol awakening response when measured after surgery but before adjuvant therapy, according to Kate R. Kuhlman, PhD.

“There are several psychological interventions that mitigate depressive symptoms and psychologic distress in women with breast cancer. This time period immediately following cancer diagnosis and surgery may be the optimal time to intervene,” said Dr. Kuhlman, a psychologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

She presented a prospective study of 135 women with breast cancer who collected saliva samples for analysis of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning on 3 consecutive days after their primary surgery but prior to starting adjuvant therapy. Samples were obtained on each of the 3 days upon awakening, 30 minutes later, 8 hours later, and at bedtime. The women also completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) then and again 6 months after completing their breast cancer treatment.

At baseline, 45 of the 135 women scored 16 points or higher out of a possible 60 on the 20-question CES-D, indicative of clinically significant depression. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning wasn’t associated with depressive symptoms at that time. Importantly, however, one measure of baseline HPA axis functioning – the cortisol awakening response – proved to be associated with an increase in depressive symptoms over time, Dr. Kuhlman reported.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, breast cancer stage, type of surgery, and forms of adjuvant therapy, a 1-standard-deviation increase above the mean in baseline cortisol awakening response was associated with a 6-point increase in CES-D score at follow-up 6 months after completion of breast cancer therapy. This association was seen only in the 90 women without significant depressive symptoms at baseline. And that’s exactly the population where a predictive biologic marker for future depression is most needed, Dr. Kuhlman said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

“The people at highest risk of depressive symptoms in the future are the ones who have the most symptoms now. They’re easy to identify. We have good reliable measures. But then there are also people at risk whom we would miss by using those measures because they don’t have high symptoms right now,” the psychologist explained.

She and her coinvestigators zeroed in on cortisol awakening response as a potential biomarker of increased future risk of depression because it reflects the adrenal gland’s sensitivity to adrenocorticotropic hormone and the gland’s ability to signal the pituitary to produce cortisol. This action is triggered when people go from sleep to awakening.

The next steps in this research are to confirm these novel findings and hunt for an alternative marker of adrenal sensitivity to adrenocorticotropic hormone that’s simpler than sending a waking saliva sample off to a laboratory.

This ongoing longitudinal study is funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Kuhlman reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly 40% of breast cancer patients experience prolonged depression lasting for at least 16 months after diagnosis of their malignancy; those at increased risk may be identifiable in a timely way by their exaggerated cortisol awakening response when measured after surgery but before adjuvant therapy, according to Kate R. Kuhlman, PhD.

“There are several psychological interventions that mitigate depressive symptoms and psychologic distress in women with breast cancer. This time period immediately following cancer diagnosis and surgery may be the optimal time to intervene,” said Dr. Kuhlman, a psychologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

She presented a prospective study of 135 women with breast cancer who collected saliva samples for analysis of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning on 3 consecutive days after their primary surgery but prior to starting adjuvant therapy. Samples were obtained on each of the 3 days upon awakening, 30 minutes later, 8 hours later, and at bedtime. The women also completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) then and again 6 months after completing their breast cancer treatment.

At baseline, 45 of the 135 women scored 16 points or higher out of a possible 60 on the 20-question CES-D, indicative of clinically significant depression. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning wasn’t associated with depressive symptoms at that time. Importantly, however, one measure of baseline HPA axis functioning – the cortisol awakening response – proved to be associated with an increase in depressive symptoms over time, Dr. Kuhlman reported.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, breast cancer stage, type of surgery, and forms of adjuvant therapy, a 1-standard-deviation increase above the mean in baseline cortisol awakening response was associated with a 6-point increase in CES-D score at follow-up 6 months after completion of breast cancer therapy. This association was seen only in the 90 women without significant depressive symptoms at baseline. And that’s exactly the population where a predictive biologic marker for future depression is most needed, Dr. Kuhlman said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

“The people at highest risk of depressive symptoms in the future are the ones who have the most symptoms now. They’re easy to identify. We have good reliable measures. But then there are also people at risk whom we would miss by using those measures because they don’t have high symptoms right now,” the psychologist explained.

She and her coinvestigators zeroed in on cortisol awakening response as a potential biomarker of increased future risk of depression because it reflects the adrenal gland’s sensitivity to adrenocorticotropic hormone and the gland’s ability to signal the pituitary to produce cortisol. This action is triggered when people go from sleep to awakening.

The next steps in this research are to confirm these novel findings and hunt for an alternative marker of adrenal sensitivity to adrenocorticotropic hormone that’s simpler than sending a waking saliva sample off to a laboratory.

This ongoing longitudinal study is funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Kuhlman reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly 40% of breast cancer patients experience prolonged depression lasting for at least 16 months after diagnosis of their malignancy; those at increased risk may be identifiable in a timely way by their exaggerated cortisol awakening response when measured after surgery but before adjuvant therapy, according to Kate R. Kuhlman, PhD.

“There are several psychological interventions that mitigate depressive symptoms and psychologic distress in women with breast cancer. This time period immediately following cancer diagnosis and surgery may be the optimal time to intervene,” said Dr. Kuhlman, a psychologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

She presented a prospective study of 135 women with breast cancer who collected saliva samples for analysis of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning on 3 consecutive days after their primary surgery but prior to starting adjuvant therapy. Samples were obtained on each of the 3 days upon awakening, 30 minutes later, 8 hours later, and at bedtime. The women also completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) then and again 6 months after completing their breast cancer treatment.

At baseline, 45 of the 135 women scored 16 points or higher out of a possible 60 on the 20-question CES-D, indicative of clinically significant depression. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning wasn’t associated with depressive symptoms at that time. Importantly, however, one measure of baseline HPA axis functioning – the cortisol awakening response – proved to be associated with an increase in depressive symptoms over time, Dr. Kuhlman reported.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, breast cancer stage, type of surgery, and forms of adjuvant therapy, a 1-standard-deviation increase above the mean in baseline cortisol awakening response was associated with a 6-point increase in CES-D score at follow-up 6 months after completion of breast cancer therapy. This association was seen only in the 90 women without significant depressive symptoms at baseline. And that’s exactly the population where a predictive biologic marker for future depression is most needed, Dr. Kuhlman said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

“The people at highest risk of depressive symptoms in the future are the ones who have the most symptoms now. They’re easy to identify. We have good reliable measures. But then there are also people at risk whom we would miss by using those measures because they don’t have high symptoms right now,” the psychologist explained.

She and her coinvestigators zeroed in on cortisol awakening response as a potential biomarker of increased future risk of depression because it reflects the adrenal gland’s sensitivity to adrenocorticotropic hormone and the gland’s ability to signal the pituitary to produce cortisol. This action is triggered when people go from sleep to awakening.

The next steps in this research are to confirm these novel findings and hunt for an alternative marker of adrenal sensitivity to adrenocorticotropic hormone that’s simpler than sending a waking saliva sample off to a laboratory.

This ongoing longitudinal study is funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Kuhlman reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Nondepressed breast cancer patients whose saliva samples show an exaggerated cortisol awakening response when measured after surgery but before adjuvant therapy are at increased risk for developing prolonged depression as treatment progresses.

Data source: A prospective longitudinal study of 135 women with breast cancer.

Disclosures: This ongoing study is funded by the National Cancer Institute. The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Complicated grief treatment gets better results than interpersonal psychotherapy

SAN FRANCISCO – The effectiveness of complicated grief treatment (CGT) rests, to a significant extent, on its capacity to reduce the grieving patient’s level of avoidance of reminders of the loss, Kim Glickman, PhD, said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Her psychotherapeutic mechanism-of-action study identified two other mediators of improvement in response to CGT: guilt related to the death and negative thoughts about the future. Patients who experienced significant reductions in levels of those variables during CGT were much more likely to ultimately be treatment responders.

The clinical implication of these findings is that psychotherapists should focus on reducing grief complications, such as avoidance behaviors and maladaptive thoughts, including blaming oneself or others for how the person died and seeing a hopeless future, according to Dr. Glickman, of City University of New York.

Complicated grief affects about 7% of bereaved individuals. It is characterized by prolonged emotional pain, intense sorrow, preoccupation with thoughts of the loved one, and persistent yearning. It is typically resistant to antidepressant therapy. In the DSM-5, it is called “persistent complex bereavement disorder” and is described in a chapter on provisional conditions for further study. Since it doesn’t have the status of a formal diagnostic entity, insurers typically will not pay for treatment of complicated grief reactions.

CGT has been shown to be effective in three randomized clinical trials. It is a manualized 16-session therapy that can be considered a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy with added elements of interpersonal psychotherapy and motivational interviewing. The focus is on encouraging adaptation to the loss by keeping grief center stage, honoring the person who died, and envisioning a future with possibilities for happiness, Dr. Glickman explained.

The mechanisms of action of CGT haven’t been well-characterized. This was the impetus for Dr. Glickman’s study, in which she analyzed data from the first randomized trial to demonstrate CGT’s effectiveness more than a decade ago (JAMA. 2005 Jun 1;293[21]:2601-8).

Among the 69 patients with complicated grief who completed 16 sessions of psychotherapy, the clinical response rate was 51% in the CGT group, compared with 28% in patients randomized to interpersonal psychotherapy. The number needed to treat with CGT was 4.3 in order to achieve a clinical response, defined as either a Clinical Global Impression–Improvement score of 1 or 2 or at least a 20-point improvement pre to post treatment on the self-rated Inventory of Complicated Grief.

In order to more closely examine potential mediators of clinical response, Dr. Glickman chose as her measure of change in feelings of guilt the study participants’ scores on the Structured Clinical Interview for Complicated Grief. To assess negative thoughts about the future, she relied on item two from the Beck Depression Inventory and, for avoidance behaviors, she used scores on the 15-item Grief-Related Avoidance Questionnaire.

CGT proved significantly more effective than interpersonal therapy at improving scores on all three of these instruments. The mediating effect was most robust for improvement in avoidance behaviors.

Dr. Glickman’s future research plans include looking at additional possible mediators of CGT’s efficacy, including change in emotion regulation, ideally assessed on a weekly basis during the course of treatment.

Complicated grief therapy was pioneered by therapists at Columbia University in New York. Dr. Glickman noted that more information about complicated grief and training in CGT is available at www.complicatedgrief.columbia.edu.

The randomized trial on which her analysis was based was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Glickman reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

SAN FRANCISCO – The effectiveness of complicated grief treatment (CGT) rests, to a significant extent, on its capacity to reduce the grieving patient’s level of avoidance of reminders of the loss, Kim Glickman, PhD, said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Her psychotherapeutic mechanism-of-action study identified two other mediators of improvement in response to CGT: guilt related to the death and negative thoughts about the future. Patients who experienced significant reductions in levels of those variables during CGT were much more likely to ultimately be treatment responders.

The clinical implication of these findings is that psychotherapists should focus on reducing grief complications, such as avoidance behaviors and maladaptive thoughts, including blaming oneself or others for how the person died and seeing a hopeless future, according to Dr. Glickman, of City University of New York.

Complicated grief affects about 7% of bereaved individuals. It is characterized by prolonged emotional pain, intense sorrow, preoccupation with thoughts of the loved one, and persistent yearning. It is typically resistant to antidepressant therapy. In the DSM-5, it is called “persistent complex bereavement disorder” and is described in a chapter on provisional conditions for further study. Since it doesn’t have the status of a formal diagnostic entity, insurers typically will not pay for treatment of complicated grief reactions.

CGT has been shown to be effective in three randomized clinical trials. It is a manualized 16-session therapy that can be considered a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy with added elements of interpersonal psychotherapy and motivational interviewing. The focus is on encouraging adaptation to the loss by keeping grief center stage, honoring the person who died, and envisioning a future with possibilities for happiness, Dr. Glickman explained.

The mechanisms of action of CGT haven’t been well-characterized. This was the impetus for Dr. Glickman’s study, in which she analyzed data from the first randomized trial to demonstrate CGT’s effectiveness more than a decade ago (JAMA. 2005 Jun 1;293[21]:2601-8).

Among the 69 patients with complicated grief who completed 16 sessions of psychotherapy, the clinical response rate was 51% in the CGT group, compared with 28% in patients randomized to interpersonal psychotherapy. The number needed to treat with CGT was 4.3 in order to achieve a clinical response, defined as either a Clinical Global Impression–Improvement score of 1 or 2 or at least a 20-point improvement pre to post treatment on the self-rated Inventory of Complicated Grief.

In order to more closely examine potential mediators of clinical response, Dr. Glickman chose as her measure of change in feelings of guilt the study participants’ scores on the Structured Clinical Interview for Complicated Grief. To assess negative thoughts about the future, she relied on item two from the Beck Depression Inventory and, for avoidance behaviors, she used scores on the 15-item Grief-Related Avoidance Questionnaire.

CGT proved significantly more effective than interpersonal therapy at improving scores on all three of these instruments. The mediating effect was most robust for improvement in avoidance behaviors.

Dr. Glickman’s future research plans include looking at additional possible mediators of CGT’s efficacy, including change in emotion regulation, ideally assessed on a weekly basis during the course of treatment.

Complicated grief therapy was pioneered by therapists at Columbia University in New York. Dr. Glickman noted that more information about complicated grief and training in CGT is available at www.complicatedgrief.columbia.edu.

The randomized trial on which her analysis was based was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Glickman reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

SAN FRANCISCO – The effectiveness of complicated grief treatment (CGT) rests, to a significant extent, on its capacity to reduce the grieving patient’s level of avoidance of reminders of the loss, Kim Glickman, PhD, said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Her psychotherapeutic mechanism-of-action study identified two other mediators of improvement in response to CGT: guilt related to the death and negative thoughts about the future. Patients who experienced significant reductions in levels of those variables during CGT were much more likely to ultimately be treatment responders.

The clinical implication of these findings is that psychotherapists should focus on reducing grief complications, such as avoidance behaviors and maladaptive thoughts, including blaming oneself or others for how the person died and seeing a hopeless future, according to Dr. Glickman, of City University of New York.

Complicated grief affects about 7% of bereaved individuals. It is characterized by prolonged emotional pain, intense sorrow, preoccupation with thoughts of the loved one, and persistent yearning. It is typically resistant to antidepressant therapy. In the DSM-5, it is called “persistent complex bereavement disorder” and is described in a chapter on provisional conditions for further study. Since it doesn’t have the status of a formal diagnostic entity, insurers typically will not pay for treatment of complicated grief reactions.

CGT has been shown to be effective in three randomized clinical trials. It is a manualized 16-session therapy that can be considered a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy with added elements of interpersonal psychotherapy and motivational interviewing. The focus is on encouraging adaptation to the loss by keeping grief center stage, honoring the person who died, and envisioning a future with possibilities for happiness, Dr. Glickman explained.

The mechanisms of action of CGT haven’t been well-characterized. This was the impetus for Dr. Glickman’s study, in which she analyzed data from the first randomized trial to demonstrate CGT’s effectiveness more than a decade ago (JAMA. 2005 Jun 1;293[21]:2601-8).

Among the 69 patients with complicated grief who completed 16 sessions of psychotherapy, the clinical response rate was 51% in the CGT group, compared with 28% in patients randomized to interpersonal psychotherapy. The number needed to treat with CGT was 4.3 in order to achieve a clinical response, defined as either a Clinical Global Impression–Improvement score of 1 or 2 or at least a 20-point improvement pre to post treatment on the self-rated Inventory of Complicated Grief.

In order to more closely examine potential mediators of clinical response, Dr. Glickman chose as her measure of change in feelings of guilt the study participants’ scores on the Structured Clinical Interview for Complicated Grief. To assess negative thoughts about the future, she relied on item two from the Beck Depression Inventory and, for avoidance behaviors, she used scores on the 15-item Grief-Related Avoidance Questionnaire.

CGT proved significantly more effective than interpersonal therapy at improving scores on all three of these instruments. The mediating effect was most robust for improvement in avoidance behaviors.

Dr. Glickman’s future research plans include looking at additional possible mediators of CGT’s efficacy, including change in emotion regulation, ideally assessed on a weekly basis during the course of treatment.

Complicated grief therapy was pioneered by therapists at Columbia University in New York. Dr. Glickman noted that more information about complicated grief and training in CGT is available at www.complicatedgrief.columbia.edu.

The randomized trial on which her analysis was based was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Glickman reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

AT THE ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A key mediator of clinical improvement in response to cognitive grief treatment is a reduction in avoidance behaviors.

Data source: A secondary analysis of a randomized trial of complicated grief treatment versus interpersonal psychotherapy in 69 patients with complicated grief.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Tweaking CBT may boost outcomes in hoarding disorder

SAN FRANCISCO – Cognitive-behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder leaves substantial room for improvement in efficacy, and additional therapeutic attention to maladaptive beliefs regarding perfectionism just might be the answer, Hannah C. Levy, PhD, said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

She presented a secondary analysis of the relationship between cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) outcomes and baseline maladaptive beliefs in a wait list–controlled study of 36 patients with hoarding disorder (HD) who were not on psychiatric medication. Her purpose was to identify which cognitive domains predicted treatment outcome. This, in turn, could point the way to new treatment targets.

In contrast, the baseline strength of Saving Cognitions Inventory maladaptive beliefs about saving, such as emotional attachment to hoarded objects or a belief that keeping those objects is the only way to be able to remember an important event, proved unrelated to CBT outcomes. And this finding may help explain CBT’s limited effectiveness in HD.

“I think traditionally our CBT interventions are more focused on the maladaptive saving beliefs. We’re currently not doing a whole lot about the perfectionism ideas that people may be bringing in,” said Dr. Levy of the anxiety disorders center at the Institute of Living in Hartford, Conn.

A strong unmet need exists for novel targets for CBT in hoarding disorder to improve current less-than-stellar outcomes, she said. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that while CBT did provide a statistically significant benefit for this common and often disabling disease, outcomes were far from optimal. Indeed, after completing their course of CBT, patients still scored an average of 3 standard deviations above mean normal for scores on the SI-R (Depress Anxiety. 2015 Mar;32[3]:158-66).

Other investigators have recognized the limitations of current CBT for HD and tried tweaking the therapy to boost efficacy. These efforts have included formal studies incorporating home visits, adding cognitive remediation to reduce the neuropsychological deficits often present in patients with HD, and/or extending the treatment duration to 26 weekly sessions from the current standard of 15 or 16.

Unfortunately, none of these innovations has really panned out when tested, Dr. Levy said. For example, in the 36-patient study analyzed by Dr. Levy, clinically significant improvement was seen in only 41% of subjects following 26 weeks of CBT (Depress Anxiety. 2010 May;27[5]:476-84). In contrast, published response rates for CBT in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder – a related condition – are in the 85% range.

She described the perfectionism that often figures prominently in HD as a maladaptive belief that if something can’t be done perfectly, it’s not worth doing at all.

“People will say to me, ‘I can’t start discarding until I’ve got my organizational system down.’ They’re completely stymied. They can’t make any progress because their system isn’t fully coordinated yet,” the psychologist explained.

One way to potentially target this perfectionism more explicitly might be to incorporate cognitive restructuring or behavioral experiments that enable patients to test out and perhaps discard those beliefs, according to Dr. Levy.

She reported no financial conflicts regarding her analysis, which was based upon data collected in an earlier study sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health.

SAN FRANCISCO – Cognitive-behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder leaves substantial room for improvement in efficacy, and additional therapeutic attention to maladaptive beliefs regarding perfectionism just might be the answer, Hannah C. Levy, PhD, said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

She presented a secondary analysis of the relationship between cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) outcomes and baseline maladaptive beliefs in a wait list–controlled study of 36 patients with hoarding disorder (HD) who were not on psychiatric medication. Her purpose was to identify which cognitive domains predicted treatment outcome. This, in turn, could point the way to new treatment targets.

In contrast, the baseline strength of Saving Cognitions Inventory maladaptive beliefs about saving, such as emotional attachment to hoarded objects or a belief that keeping those objects is the only way to be able to remember an important event, proved unrelated to CBT outcomes. And this finding may help explain CBT’s limited effectiveness in HD.

“I think traditionally our CBT interventions are more focused on the maladaptive saving beliefs. We’re currently not doing a whole lot about the perfectionism ideas that people may be bringing in,” said Dr. Levy of the anxiety disorders center at the Institute of Living in Hartford, Conn.

A strong unmet need exists for novel targets for CBT in hoarding disorder to improve current less-than-stellar outcomes, she said. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that while CBT did provide a statistically significant benefit for this common and often disabling disease, outcomes were far from optimal. Indeed, after completing their course of CBT, patients still scored an average of 3 standard deviations above mean normal for scores on the SI-R (Depress Anxiety. 2015 Mar;32[3]:158-66).

Other investigators have recognized the limitations of current CBT for HD and tried tweaking the therapy to boost efficacy. These efforts have included formal studies incorporating home visits, adding cognitive remediation to reduce the neuropsychological deficits often present in patients with HD, and/or extending the treatment duration to 26 weekly sessions from the current standard of 15 or 16.

Unfortunately, none of these innovations has really panned out when tested, Dr. Levy said. For example, in the 36-patient study analyzed by Dr. Levy, clinically significant improvement was seen in only 41% of subjects following 26 weeks of CBT (Depress Anxiety. 2010 May;27[5]:476-84). In contrast, published response rates for CBT in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder – a related condition – are in the 85% range.

She described the perfectionism that often figures prominently in HD as a maladaptive belief that if something can’t be done perfectly, it’s not worth doing at all.

“People will say to me, ‘I can’t start discarding until I’ve got my organizational system down.’ They’re completely stymied. They can’t make any progress because their system isn’t fully coordinated yet,” the psychologist explained.

One way to potentially target this perfectionism more explicitly might be to incorporate cognitive restructuring or behavioral experiments that enable patients to test out and perhaps discard those beliefs, according to Dr. Levy.

She reported no financial conflicts regarding her analysis, which was based upon data collected in an earlier study sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health.

SAN FRANCISCO – Cognitive-behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder leaves substantial room for improvement in efficacy, and additional therapeutic attention to maladaptive beliefs regarding perfectionism just might be the answer, Hannah C. Levy, PhD, said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

She presented a secondary analysis of the relationship between cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) outcomes and baseline maladaptive beliefs in a wait list–controlled study of 36 patients with hoarding disorder (HD) who were not on psychiatric medication. Her purpose was to identify which cognitive domains predicted treatment outcome. This, in turn, could point the way to new treatment targets.

In contrast, the baseline strength of Saving Cognitions Inventory maladaptive beliefs about saving, such as emotional attachment to hoarded objects or a belief that keeping those objects is the only way to be able to remember an important event, proved unrelated to CBT outcomes. And this finding may help explain CBT’s limited effectiveness in HD.

“I think traditionally our CBT interventions are more focused on the maladaptive saving beliefs. We’re currently not doing a whole lot about the perfectionism ideas that people may be bringing in,” said Dr. Levy of the anxiety disorders center at the Institute of Living in Hartford, Conn.

A strong unmet need exists for novel targets for CBT in hoarding disorder to improve current less-than-stellar outcomes, she said. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that while CBT did provide a statistically significant benefit for this common and often disabling disease, outcomes were far from optimal. Indeed, after completing their course of CBT, patients still scored an average of 3 standard deviations above mean normal for scores on the SI-R (Depress Anxiety. 2015 Mar;32[3]:158-66).

Other investigators have recognized the limitations of current CBT for HD and tried tweaking the therapy to boost efficacy. These efforts have included formal studies incorporating home visits, adding cognitive remediation to reduce the neuropsychological deficits often present in patients with HD, and/or extending the treatment duration to 26 weekly sessions from the current standard of 15 or 16.

Unfortunately, none of these innovations has really panned out when tested, Dr. Levy said. For example, in the 36-patient study analyzed by Dr. Levy, clinically significant improvement was seen in only 41% of subjects following 26 weeks of CBT (Depress Anxiety. 2010 May;27[5]:476-84). In contrast, published response rates for CBT in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder – a related condition – are in the 85% range.

She described the perfectionism that often figures prominently in HD as a maladaptive belief that if something can’t be done perfectly, it’s not worth doing at all.

“People will say to me, ‘I can’t start discarding until I’ve got my organizational system down.’ They’re completely stymied. They can’t make any progress because their system isn’t fully coordinated yet,” the psychologist explained.

One way to potentially target this perfectionism more explicitly might be to incorporate cognitive restructuring or behavioral experiments that enable patients to test out and perhaps discard those beliefs, according to Dr. Levy.

She reported no financial conflicts regarding her analysis, which was based upon data collected in an earlier study sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health.

AT ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: High baseline levels of perfectionism and rigidity of thinking were associated with lack of response to 26 weeks of CBT for hoarding disorder.

Data source: A secondary analysis of data from a prospective study of 36 patients with primary hoarding disorder.

Disclosures: The presenter reported no financial conflicts regarding her analysis, which was based upon data collected in an earlier study sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Illness-induced PTSD is common, understudied

SAN FRANCISCO – Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms triggered by a life-threatening medical illness differ from the more common PTSD, the source of which is an external trauma such as an assault or natural disaster, according to Renee El-Gabalawy, PhD.

“This suggests implications for diagnostic classification. Maybe, in future editions of the DSM, we should think of this as a subtype of PTSD or potentially as a new diagnostic category, although it’s far too early to make any conclusions about that,” Dr. El-Gabalawy said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

It’s estimated that PTSD occurs in 12%-25% of people who experience a life-threatening medical event.

“This is a fairly staggering proportion of people, and unfortunately this is a very overlooked area in the PTSD literature, almost all of which has been done in critical care units or oncology settings,” said Dr. El-Gabalawy, a psychologist at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

She presented an analysis of data from the 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, in which a nationally representative sample composed of 36,309 U.S. adults were interviewed face to face, with the current DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD being applied using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Association Disabilities Interview Schedule–5 (AUDADIS-5).

A total of 1,779 subjects (4.9%) indicated they had experienced physician-diagnosed PTSD during the previous year. Of those, 6.5% said their PTSD was triggered by an acute life-threatening medical event. The rest were attributed to nonmedical trauma.

There were sharp demographic differences between the two groups. Individuals with medical illness–induced PTSD were older – 35 years old at onset of their first episode, compared with age 23 in the others – with later onset of their PTSD. They were more likely to be men: 45.7% were male, compared with 31.8% for subjects with nonmedical PTSD. Comorbid depression was present in 25.4% of those with medical illness–induced PTSD, and comorbid panic disorder was present in 17%, significantly lower than the 37% and 24.5% rates in individuals with other triggers of PTSD.

Quality of life as measured by the Short Form-12 was similar in the two groups, after the investigators controlled for the number of medical conditions patients had.

Of people with medical illness–induced PTSD, 41% attributed their PTSD to a digestive disease, most often inflammatory bowel disease. In contrast, a digestive condition was present in 19.2% of subjects with nonmedical trauma as the source of their PTSD. Thus, a serious digestive disorder was associated with a 2.4-times increased risk of medical illness–induced PTSD in an analysis adjusted for socioeconomic factors and number of health conditions. Cancer, which was the trigger for 16.1% of cases of medical illness–induced PTSD and which had a prevalence of 5.8% in those with nonmedical sources of PTSD, was associated with a 2.64-times increased risk of medical illness–related PTSD.

“Those odds ratios are quite high for a population-based sample. This was a very dramatic effect,” Dr. El-Gabalawy commented.

The two groups of participants with PTSD had similar intensity of core PTSD symptom clusters with the exception of negative mood/cognition, which figured more prominently in those with medical illness–induced PTSD.

“This is very much in line with my clinical experience, that what’s really predominant in these folks are the maladaptive cognitions, their fear about their future health trajectory,” she said. “I tend to use cognitive processing therapy in these patients. It really taps into those maladaptive cognitions, and I’ve found that my patients are very receptive to this. Cognitive processing therapy might be more advantageous in this situation than prolonged exposure therapy .”

Dr. El-Gabalawy said she is a fan of the Enduring Somatic Threat model of medical illness–induced PTSD developed by Donald Edmondson, PhD, of Columbia University in New York (Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014 Mar 5;8[3]:118-34).

“It aligns with the literature and my own clinical experience,” she explained.

Dr. Edmondson’s model draws conceptual distinctions between medical illness–induced PTSD and other causes of PTSD. In medical illness–related PTSD, the trauma has a somatic source, the trauma tends to be chronic, and intrusive thoughts tend to be future oriented and highly cognitive in nature.

“It’s not uncommon that I’ll hear my patients with medical illness–induced PTSD say, ‘I’m really scared my disease is going to get worse.’ And behavioral avoidance is really difficult. Whereas, in the traditional conceptualization of PTSD, the intrusions are often past oriented and elicited by external triggers. Behavioral avoidance of those triggers is possible, but, in illness-related PTSD, arousal is keyed to internal triggers, often somatic in nature, such as heart palpitations,” according to the psychologist.

Her study was supported by the Canadian National Institutes of Health Research and the University of Manitoba. She reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms triggered by a life-threatening medical illness differ from the more common PTSD, the source of which is an external trauma such as an assault or natural disaster, according to Renee El-Gabalawy, PhD.

“This suggests implications for diagnostic classification. Maybe, in future editions of the DSM, we should think of this as a subtype of PTSD or potentially as a new diagnostic category, although it’s far too early to make any conclusions about that,” Dr. El-Gabalawy said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

It’s estimated that PTSD occurs in 12%-25% of people who experience a life-threatening medical event.

“This is a fairly staggering proportion of people, and unfortunately this is a very overlooked area in the PTSD literature, almost all of which has been done in critical care units or oncology settings,” said Dr. El-Gabalawy, a psychologist at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

She presented an analysis of data from the 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, in which a nationally representative sample composed of 36,309 U.S. adults were interviewed face to face, with the current DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD being applied using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Association Disabilities Interview Schedule–5 (AUDADIS-5).

A total of 1,779 subjects (4.9%) indicated they had experienced physician-diagnosed PTSD during the previous year. Of those, 6.5% said their PTSD was triggered by an acute life-threatening medical event. The rest were attributed to nonmedical trauma.

There were sharp demographic differences between the two groups. Individuals with medical illness–induced PTSD were older – 35 years old at onset of their first episode, compared with age 23 in the others – with later onset of their PTSD. They were more likely to be men: 45.7% were male, compared with 31.8% for subjects with nonmedical PTSD. Comorbid depression was present in 25.4% of those with medical illness–induced PTSD, and comorbid panic disorder was present in 17%, significantly lower than the 37% and 24.5% rates in individuals with other triggers of PTSD.

Quality of life as measured by the Short Form-12 was similar in the two groups, after the investigators controlled for the number of medical conditions patients had.

Of people with medical illness–induced PTSD, 41% attributed their PTSD to a digestive disease, most often inflammatory bowel disease. In contrast, a digestive condition was present in 19.2% of subjects with nonmedical trauma as the source of their PTSD. Thus, a serious digestive disorder was associated with a 2.4-times increased risk of medical illness–induced PTSD in an analysis adjusted for socioeconomic factors and number of health conditions. Cancer, which was the trigger for 16.1% of cases of medical illness–induced PTSD and which had a prevalence of 5.8% in those with nonmedical sources of PTSD, was associated with a 2.64-times increased risk of medical illness–related PTSD.

“Those odds ratios are quite high for a population-based sample. This was a very dramatic effect,” Dr. El-Gabalawy commented.

The two groups of participants with PTSD had similar intensity of core PTSD symptom clusters with the exception of negative mood/cognition, which figured more prominently in those with medical illness–induced PTSD.

“This is very much in line with my clinical experience, that what’s really predominant in these folks are the maladaptive cognitions, their fear about their future health trajectory,” she said. “I tend to use cognitive processing therapy in these patients. It really taps into those maladaptive cognitions, and I’ve found that my patients are very receptive to this. Cognitive processing therapy might be more advantageous in this situation than prolonged exposure therapy .”

Dr. El-Gabalawy said she is a fan of the Enduring Somatic Threat model of medical illness–induced PTSD developed by Donald Edmondson, PhD, of Columbia University in New York (Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014 Mar 5;8[3]:118-34).

“It aligns with the literature and my own clinical experience,” she explained.

Dr. Edmondson’s model draws conceptual distinctions between medical illness–induced PTSD and other causes of PTSD. In medical illness–related PTSD, the trauma has a somatic source, the trauma tends to be chronic, and intrusive thoughts tend to be future oriented and highly cognitive in nature.

“It’s not uncommon that I’ll hear my patients with medical illness–induced PTSD say, ‘I’m really scared my disease is going to get worse.’ And behavioral avoidance is really difficult. Whereas, in the traditional conceptualization of PTSD, the intrusions are often past oriented and elicited by external triggers. Behavioral avoidance of those triggers is possible, but, in illness-related PTSD, arousal is keyed to internal triggers, often somatic in nature, such as heart palpitations,” according to the psychologist.

Her study was supported by the Canadian National Institutes of Health Research and the University of Manitoba. She reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms triggered by a life-threatening medical illness differ from the more common PTSD, the source of which is an external trauma such as an assault or natural disaster, according to Renee El-Gabalawy, PhD.

“This suggests implications for diagnostic classification. Maybe, in future editions of the DSM, we should think of this as a subtype of PTSD or potentially as a new diagnostic category, although it’s far too early to make any conclusions about that,” Dr. El-Gabalawy said at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

It’s estimated that PTSD occurs in 12%-25% of people who experience a life-threatening medical event.

“This is a fairly staggering proportion of people, and unfortunately this is a very overlooked area in the PTSD literature, almost all of which has been done in critical care units or oncology settings,” said Dr. El-Gabalawy, a psychologist at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg.

She presented an analysis of data from the 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, in which a nationally representative sample composed of 36,309 U.S. adults were interviewed face to face, with the current DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD being applied using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Association Disabilities Interview Schedule–5 (AUDADIS-5).

A total of 1,779 subjects (4.9%) indicated they had experienced physician-diagnosed PTSD during the previous year. Of those, 6.5% said their PTSD was triggered by an acute life-threatening medical event. The rest were attributed to nonmedical trauma.

There were sharp demographic differences between the two groups. Individuals with medical illness–induced PTSD were older – 35 years old at onset of their first episode, compared with age 23 in the others – with later onset of their PTSD. They were more likely to be men: 45.7% were male, compared with 31.8% for subjects with nonmedical PTSD. Comorbid depression was present in 25.4% of those with medical illness–induced PTSD, and comorbid panic disorder was present in 17%, significantly lower than the 37% and 24.5% rates in individuals with other triggers of PTSD.

Quality of life as measured by the Short Form-12 was similar in the two groups, after the investigators controlled for the number of medical conditions patients had.

Of people with medical illness–induced PTSD, 41% attributed their PTSD to a digestive disease, most often inflammatory bowel disease. In contrast, a digestive condition was present in 19.2% of subjects with nonmedical trauma as the source of their PTSD. Thus, a serious digestive disorder was associated with a 2.4-times increased risk of medical illness–induced PTSD in an analysis adjusted for socioeconomic factors and number of health conditions. Cancer, which was the trigger for 16.1% of cases of medical illness–induced PTSD and which had a prevalence of 5.8% in those with nonmedical sources of PTSD, was associated with a 2.64-times increased risk of medical illness–related PTSD.

“Those odds ratios are quite high for a population-based sample. This was a very dramatic effect,” Dr. El-Gabalawy commented.

The two groups of participants with PTSD had similar intensity of core PTSD symptom clusters with the exception of negative mood/cognition, which figured more prominently in those with medical illness–induced PTSD.

“This is very much in line with my clinical experience, that what’s really predominant in these folks are the maladaptive cognitions, their fear about their future health trajectory,” she said. “I tend to use cognitive processing therapy in these patients. It really taps into those maladaptive cognitions, and I’ve found that my patients are very receptive to this. Cognitive processing therapy might be more advantageous in this situation than prolonged exposure therapy .”

Dr. El-Gabalawy said she is a fan of the Enduring Somatic Threat model of medical illness–induced PTSD developed by Donald Edmondson, PhD, of Columbia University in New York (Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014 Mar 5;8[3]:118-34).

“It aligns with the literature and my own clinical experience,” she explained.

Dr. Edmondson’s model draws conceptual distinctions between medical illness–induced PTSD and other causes of PTSD. In medical illness–related PTSD, the trauma has a somatic source, the trauma tends to be chronic, and intrusive thoughts tend to be future oriented and highly cognitive in nature.

“It’s not uncommon that I’ll hear my patients with medical illness–induced PTSD say, ‘I’m really scared my disease is going to get worse.’ And behavioral avoidance is really difficult. Whereas, in the traditional conceptualization of PTSD, the intrusions are often past oriented and elicited by external triggers. Behavioral avoidance of those triggers is possible, but, in illness-related PTSD, arousal is keyed to internal triggers, often somatic in nature, such as heart palpitations,” according to the psychologist.

Her study was supported by the Canadian National Institutes of Health Research and the University of Manitoba. She reported having no financial conflicts.

AT ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Individuals with PTSD and a serious digestive disease were 2.4-times more likely to have medical illness–induced PTSD than PTSD triggered by a nonmedical cause.

Data source: A cross-sectional study of a nationally representative sample of more than 36,000 U.S. adults, 4.9% of whom met DSM 5 criteria for PTSD.

Disclosures: The presenter reported no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the Canadian National Institutes of Health Research and the University of Manitoba.

Children exposed to violence show accelerated cellular aging

SAN FRANCISCO – Children exposed to high levels of urban violence demonstrate accelerated cellular aging beyond their chronologic years, Vasiliki Michopoulos, PhD, reported at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

This fast-running cellular biologic clock is not a good thing. Neither is their blunted heart rate variability in response to stress, an indicator of autonomic dysfunction that constitutes a cardiovascular risk factor, she added.

Accelerated cellular aging as measured by DNA methylation in blood or saliva samples has become a red hot research area. Investigators have shown that a person’s DNA methylation age, also known as epigenetic age, predicts all-cause mortality risk in later life. In adults, accelerated cellular aging as reflected in a 5-year discrepancy between DNA methylation age and chronologic age is predictive of an adjusted 16% increased mortality risk independent of social class, education level, lifestyle factors, and chronic diseases, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Genome Biol. 2015 Jan 30;16:25).

Lifetime exposure to stress has been convincingly shown to accelerate epigenetic aging, as reflected by DNA methylation level. But, prior to Dr. Michopoulos’s study, it wasn’t known if exposure to violence during childhood influences epigenetic aging or if perhaps only later-life trauma is relevant.

To address this question, she and her coinvestigators recruited 101 African American children aged 6-11 years and their mothers. Of note, medical attention wasn’t being sought for the children. Rather, their mothers were approached regarding study participation while attending primary care clinics at Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital. Children were not eligible to participate if they had been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, cognitive impairment, or a psychotic disorder.

The children had been exposed to a lot of violence, both witnessed and directly experienced, as reflected in their mean total score of 18.9 on the Violence Exposure Scale for Children-Revised (VEX-R). More than 80% of the children had witnessed an assault and 30% a murder. Stabbings, shootings, drug trafficking, and arrests were other common exposures.

One-quarter of the children showed accelerated cellular aging. They had experienced twice as much violence exposure as reflected in their VEX-R scores, compared with children whose epigenetic and chronologic ages were the same.

The children with accelerated cellular aging also demonstrated decreased heart rate variability in response to a standardized stressor, which involved a startle experience in a darkened room. Their heart rate in the stressor situation shot up on average by 17 bpm less than the children whose cellular age as measured by DNA methylation matched their chronologic age.

“Our data suggest that DNA methylation may serve as a biomarker by which to identify at-risk individuals who may benefit from interventions that decrease risk for cardiometabolic disorders in adulthood,” Dr. Michopoulos said. “It’ll be really interesting to see, as these kids grow up and develop, whether their phenotype stays static, reverses, or changes completely.”

Dr. Michopoulos reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted as part of the Grady Trauma Project (www.gradytraumaproject.com) with funding from the National Institute of Mental Health and Emory University and Grady Memorial Hospital, both in Atlanta.

SAN FRANCISCO – Children exposed to high levels of urban violence demonstrate accelerated cellular aging beyond their chronologic years, Vasiliki Michopoulos, PhD, reported at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

This fast-running cellular biologic clock is not a good thing. Neither is their blunted heart rate variability in response to stress, an indicator of autonomic dysfunction that constitutes a cardiovascular risk factor, she added.

Accelerated cellular aging as measured by DNA methylation in blood or saliva samples has become a red hot research area. Investigators have shown that a person’s DNA methylation age, also known as epigenetic age, predicts all-cause mortality risk in later life. In adults, accelerated cellular aging as reflected in a 5-year discrepancy between DNA methylation age and chronologic age is predictive of an adjusted 16% increased mortality risk independent of social class, education level, lifestyle factors, and chronic diseases, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Genome Biol. 2015 Jan 30;16:25).

Lifetime exposure to stress has been convincingly shown to accelerate epigenetic aging, as reflected by DNA methylation level. But, prior to Dr. Michopoulos’s study, it wasn’t known if exposure to violence during childhood influences epigenetic aging or if perhaps only later-life trauma is relevant.

To address this question, she and her coinvestigators recruited 101 African American children aged 6-11 years and their mothers. Of note, medical attention wasn’t being sought for the children. Rather, their mothers were approached regarding study participation while attending primary care clinics at Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital. Children were not eligible to participate if they had been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, cognitive impairment, or a psychotic disorder.

The children had been exposed to a lot of violence, both witnessed and directly experienced, as reflected in their mean total score of 18.9 on the Violence Exposure Scale for Children-Revised (VEX-R). More than 80% of the children had witnessed an assault and 30% a murder. Stabbings, shootings, drug trafficking, and arrests were other common exposures.

One-quarter of the children showed accelerated cellular aging. They had experienced twice as much violence exposure as reflected in their VEX-R scores, compared with children whose epigenetic and chronologic ages were the same.

The children with accelerated cellular aging also demonstrated decreased heart rate variability in response to a standardized stressor, which involved a startle experience in a darkened room. Their heart rate in the stressor situation shot up on average by 17 bpm less than the children whose cellular age as measured by DNA methylation matched their chronologic age.

“Our data suggest that DNA methylation may serve as a biomarker by which to identify at-risk individuals who may benefit from interventions that decrease risk for cardiometabolic disorders in adulthood,” Dr. Michopoulos said. “It’ll be really interesting to see, as these kids grow up and develop, whether their phenotype stays static, reverses, or changes completely.”

Dr. Michopoulos reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted as part of the Grady Trauma Project (www.gradytraumaproject.com) with funding from the National Institute of Mental Health and Emory University and Grady Memorial Hospital, both in Atlanta.

SAN FRANCISCO – Children exposed to high levels of urban violence demonstrate accelerated cellular aging beyond their chronologic years, Vasiliki Michopoulos, PhD, reported at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

This fast-running cellular biologic clock is not a good thing. Neither is their blunted heart rate variability in response to stress, an indicator of autonomic dysfunction that constitutes a cardiovascular risk factor, she added.

Accelerated cellular aging as measured by DNA methylation in blood or saliva samples has become a red hot research area. Investigators have shown that a person’s DNA methylation age, also known as epigenetic age, predicts all-cause mortality risk in later life. In adults, accelerated cellular aging as reflected in a 5-year discrepancy between DNA methylation age and chronologic age is predictive of an adjusted 16% increased mortality risk independent of social class, education level, lifestyle factors, and chronic diseases, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Genome Biol. 2015 Jan 30;16:25).

Lifetime exposure to stress has been convincingly shown to accelerate epigenetic aging, as reflected by DNA methylation level. But, prior to Dr. Michopoulos’s study, it wasn’t known if exposure to violence during childhood influences epigenetic aging or if perhaps only later-life trauma is relevant.

To address this question, she and her coinvestigators recruited 101 African American children aged 6-11 years and their mothers. Of note, medical attention wasn’t being sought for the children. Rather, their mothers were approached regarding study participation while attending primary care clinics at Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital. Children were not eligible to participate if they had been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, cognitive impairment, or a psychotic disorder.

The children had been exposed to a lot of violence, both witnessed and directly experienced, as reflected in their mean total score of 18.9 on the Violence Exposure Scale for Children-Revised (VEX-R). More than 80% of the children had witnessed an assault and 30% a murder. Stabbings, shootings, drug trafficking, and arrests were other common exposures.

One-quarter of the children showed accelerated cellular aging. They had experienced twice as much violence exposure as reflected in their VEX-R scores, compared with children whose epigenetic and chronologic ages were the same.

The children with accelerated cellular aging also demonstrated decreased heart rate variability in response to a standardized stressor, which involved a startle experience in a darkened room. Their heart rate in the stressor situation shot up on average by 17 bpm less than the children whose cellular age as measured by DNA methylation matched their chronologic age.

“Our data suggest that DNA methylation may serve as a biomarker by which to identify at-risk individuals who may benefit from interventions that decrease risk for cardiometabolic disorders in adulthood,” Dr. Michopoulos said. “It’ll be really interesting to see, as these kids grow up and develop, whether their phenotype stays static, reverses, or changes completely.”

Dr. Michopoulos reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted as part of the Grady Trauma Project (www.gradytraumaproject.com) with funding from the National Institute of Mental Health and Emory University and Grady Memorial Hospital, both in Atlanta.

AT THE ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Children who demonstrated advanced cellular aging based on DNA methylation levels had experienced twice as much exposure to violence as those whose epigenetic and chronologic ages matched.

Data source: This cross-sectional study included 101 urban African American children aged 6-11 years.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and Emory University and Grady Memorial Hospital, both in Atlanta.

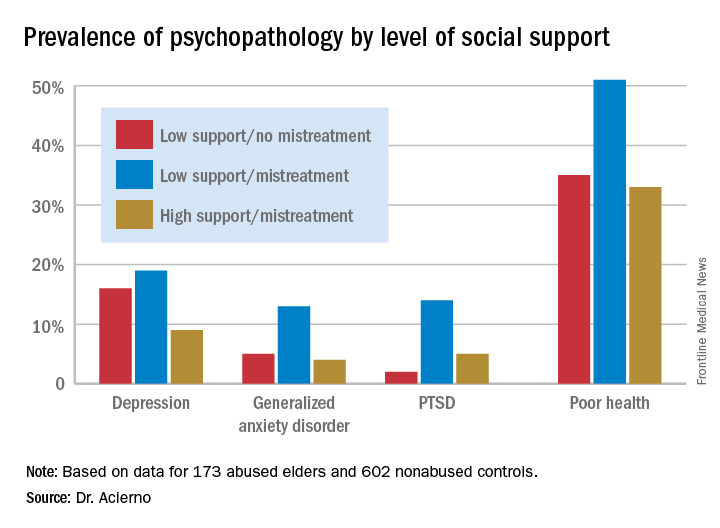

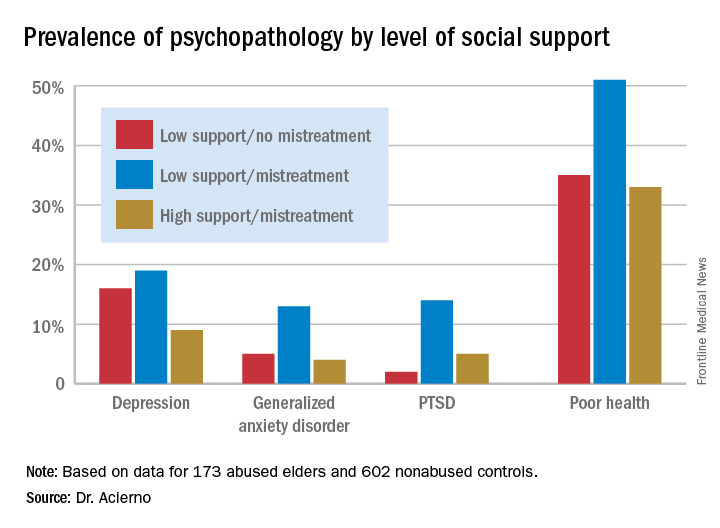

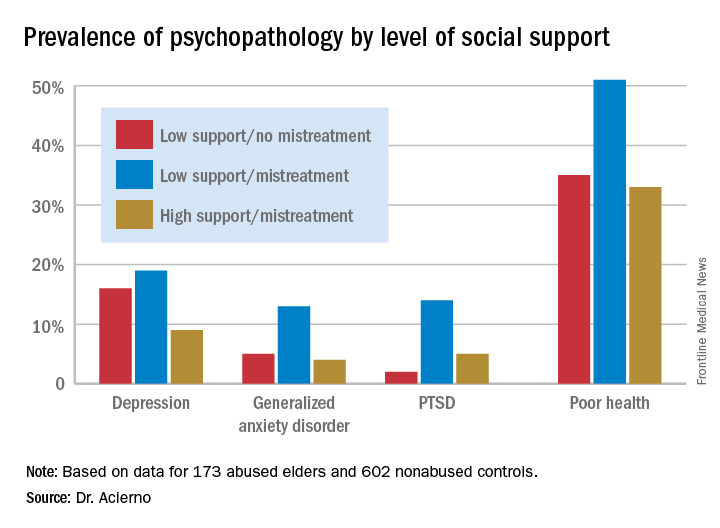

Elder abuse: Strong social support prevents associated psychopathology

SAN FRANCISCO – Victims of elder abuse who have perceived strong social support from family or friends are “completely inoculated” against the otherwise dramatically increased risk of trauma-related psychopathology that pertains to mistreated seniors who lack such support, according to Ron Acierno, PhD.

Dr. Acierno, professor of nursing at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, presented 8-year follow-up data from the National Elder Mistreatment Study, the largest study of elder abuse ever conducted in the United States.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study involved 5,777 randomly selected community-dwelling older adults who, in 2008, participated in structured interviews assessing whether they had experienced physical, psychological, sexual, or neglectful mistreatment. The study made headlines by documenting an unexpectedly high 11% rate of elder mistreatment within the previous 12 months (Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100[2]:292-7).

Eight years later, Dr. Acierno and his coinvestigators were able to recontact 173 of the original 684 abused elders, as well as 602 nonabused controls for structured interviews assessing their current mental health. At that point, the participants averaged 84.9 years of age.

Striking differences in mental health status based on elder abuse history were documented. The prevalences of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder were 13%, 7%, and 8%, respectively, in the elder abuse group, compared with 5%, 1%, and 1% in the nonabused controls. Of the group subjected to abuse 8 years earlier, 40% were categorized at follow-up as “in poor health,” compared with 23% of controls.

More importantly, high social support essentially erased the elder abuse group’s increased risk (see graphic), Dr. Acierno said.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study was funded by the National Institute of Justice, the National Institute on Aging, and the Archstone Foundation. Dr. Acierno reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Victims of elder abuse who have perceived strong social support from family or friends are “completely inoculated” against the otherwise dramatically increased risk of trauma-related psychopathology that pertains to mistreated seniors who lack such support, according to Ron Acierno, PhD.

Dr. Acierno, professor of nursing at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, presented 8-year follow-up data from the National Elder Mistreatment Study, the largest study of elder abuse ever conducted in the United States.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study involved 5,777 randomly selected community-dwelling older adults who, in 2008, participated in structured interviews assessing whether they had experienced physical, psychological, sexual, or neglectful mistreatment. The study made headlines by documenting an unexpectedly high 11% rate of elder mistreatment within the previous 12 months (Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100[2]:292-7).

Eight years later, Dr. Acierno and his coinvestigators were able to recontact 173 of the original 684 abused elders, as well as 602 nonabused controls for structured interviews assessing their current mental health. At that point, the participants averaged 84.9 years of age.

Striking differences in mental health status based on elder abuse history were documented. The prevalences of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder were 13%, 7%, and 8%, respectively, in the elder abuse group, compared with 5%, 1%, and 1% in the nonabused controls. Of the group subjected to abuse 8 years earlier, 40% were categorized at follow-up as “in poor health,” compared with 23% of controls.

More importantly, high social support essentially erased the elder abuse group’s increased risk (see graphic), Dr. Acierno said.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study was funded by the National Institute of Justice, the National Institute on Aging, and the Archstone Foundation. Dr. Acierno reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Victims of elder abuse who have perceived strong social support from family or friends are “completely inoculated” against the otherwise dramatically increased risk of trauma-related psychopathology that pertains to mistreated seniors who lack such support, according to Ron Acierno, PhD.

Dr. Acierno, professor of nursing at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, presented 8-year follow-up data from the National Elder Mistreatment Study, the largest study of elder abuse ever conducted in the United States.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study involved 5,777 randomly selected community-dwelling older adults who, in 2008, participated in structured interviews assessing whether they had experienced physical, psychological, sexual, or neglectful mistreatment. The study made headlines by documenting an unexpectedly high 11% rate of elder mistreatment within the previous 12 months (Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100[2]:292-7).

Eight years later, Dr. Acierno and his coinvestigators were able to recontact 173 of the original 684 abused elders, as well as 602 nonabused controls for structured interviews assessing their current mental health. At that point, the participants averaged 84.9 years of age.

Striking differences in mental health status based on elder abuse history were documented. The prevalences of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder were 13%, 7%, and 8%, respectively, in the elder abuse group, compared with 5%, 1%, and 1% in the nonabused controls. Of the group subjected to abuse 8 years earlier, 40% were categorized at follow-up as “in poor health,” compared with 23% of controls.

More importantly, high social support essentially erased the elder abuse group’s increased risk (see graphic), Dr. Acierno said.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study was funded by the National Institute of Justice, the National Institute on Aging, and the Archstone Foundation. Dr. Acierno reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Having a strong social support network virtually eliminated the otherwise sharply increased risk of trauma-related psychopathology in victims of elder abuse.

Data source: An 8-year follow-up report on the mental health status of participants in the largest study of elder mistreatment in US history.

Disclosures: The National Elder Mistreatment Study was funded by the National Institute of Justice, the National Institute on Aging, and the Archstone Foundation. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Address procrastination, disorganization in hoarding disorder

SAN FRANCISCO – Procrastination, disorganization, indecisiveness, and perfectionism each are significant independent predictors of hoarding severity, even though none of these associated factors is included in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder, according to Sanjaya Saxena, MD.

Of these four associated factors, disorganization and procrastination had the strongest correlation with hoarding severity in his study. Patients meeting the DSM-5 criteria for hoarding disorder scored significantly higher on measures of disorganization and procrastination than did patients with nonhoarding obsessive-compulsive disorder or anxiety disorders, said Dr. Saxena, professor of psychiatry and director of the obsessive-compulsive disorders program at the University of California, San Diego.

The DSM-5 lists as the core symptoms of hoarding disorder difficulty in discarding possessions; perceived need to save items; excessive acquisition, clutter, and resultant distress; and impaired functioning. But while procrastination, disorganization, perfectionism, and indecisiveness aren’t included in the diagnostic criteria, Dr. Saxena said he and some other experts have considered those features to be characteristic of affected individuals. So he decided to formally test the strength of the associations.

He reported on 21 patients with hoarding disorder and 13 controls with nonhoarding OCD or an anxiety disorder. All subjects completed a battery of assessment tools, including the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale, the Frost Indecisiveness Scale, the Adult Inventory of Procrastination Scale, and three different measures of hoarding severity. Participants also completed a disorganization index based on their answers to three questions drawn from the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP-IV) Rating Scale: How often did you have difficulty organizing tasks and activities as a child? How disorganized are you in your thinking, planning, and time management? And how disorganized are your belongings at home?

Neither disorganization, procrastination, perfectionism, nor indecisiveness turned out to be associated with severity of nonhoarding OCD or anxiety disorder symptoms. Surprisingly, no significant differences were found between hoarding disorder patients and controls on the measures of indecisiveness or perfectionism, Dr. Saxena said. And the two groups did not differ in their levels of anxiety and depression.

However, levels of procrastination and disorganization were strongly correlated with hoarding severity as assessed via the Saving Inventory – Revised, the UCLA Hoarding Severity Scale, and the Hoarding Rating Scale. The hoarding disorder group’s average score on the disorganization index was 5.67, more than twice that of the 2.67 in the control group. And patients with hoarding disorder had an average Adult Inventory of Procrastination score of 50.9 out of a possible maximum of 75 points, compared with 41 in controls.

In a multivariate regression analysis, age and level of depression collectively explained 23.5% of the variance in hoarding severity scores in the study population. Disorganization independently explained an additional 29.9% of the variance, and procrastination accounted for another 19.1%, Dr. Saxena reported.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was funded by the university’s department of psychiatry.

SAN FRANCISCO – Procrastination, disorganization, indecisiveness, and perfectionism each are significant independent predictors of hoarding severity, even though none of these associated factors is included in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder, according to Sanjaya Saxena, MD.

Of these four associated factors, disorganization and procrastination had the strongest correlation with hoarding severity in his study. Patients meeting the DSM-5 criteria for hoarding disorder scored significantly higher on measures of disorganization and procrastination than did patients with nonhoarding obsessive-compulsive disorder or anxiety disorders, said Dr. Saxena, professor of psychiatry and director of the obsessive-compulsive disorders program at the University of California, San Diego.

The DSM-5 lists as the core symptoms of hoarding disorder difficulty in discarding possessions; perceived need to save items; excessive acquisition, clutter, and resultant distress; and impaired functioning. But while procrastination, disorganization, perfectionism, and indecisiveness aren’t included in the diagnostic criteria, Dr. Saxena said he and some other experts have considered those features to be characteristic of affected individuals. So he decided to formally test the strength of the associations.

He reported on 21 patients with hoarding disorder and 13 controls with nonhoarding OCD or an anxiety disorder. All subjects completed a battery of assessment tools, including the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale, the Frost Indecisiveness Scale, the Adult Inventory of Procrastination Scale, and three different measures of hoarding severity. Participants also completed a disorganization index based on their answers to three questions drawn from the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP-IV) Rating Scale: How often did you have difficulty organizing tasks and activities as a child? How disorganized are you in your thinking, planning, and time management? And how disorganized are your belongings at home?

Neither disorganization, procrastination, perfectionism, nor indecisiveness turned out to be associated with severity of nonhoarding OCD or anxiety disorder symptoms. Surprisingly, no significant differences were found between hoarding disorder patients and controls on the measures of indecisiveness or perfectionism, Dr. Saxena said. And the two groups did not differ in their levels of anxiety and depression.

However, levels of procrastination and disorganization were strongly correlated with hoarding severity as assessed via the Saving Inventory – Revised, the UCLA Hoarding Severity Scale, and the Hoarding Rating Scale. The hoarding disorder group’s average score on the disorganization index was 5.67, more than twice that of the 2.67 in the control group. And patients with hoarding disorder had an average Adult Inventory of Procrastination score of 50.9 out of a possible maximum of 75 points, compared with 41 in controls.

In a multivariate regression analysis, age and level of depression collectively explained 23.5% of the variance in hoarding severity scores in the study population. Disorganization independently explained an additional 29.9% of the variance, and procrastination accounted for another 19.1%, Dr. Saxena reported.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was funded by the university’s department of psychiatry.

SAN FRANCISCO – Procrastination, disorganization, indecisiveness, and perfectionism each are significant independent predictors of hoarding severity, even though none of these associated factors is included in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder, according to Sanjaya Saxena, MD.

Of these four associated factors, disorganization and procrastination had the strongest correlation with hoarding severity in his study. Patients meeting the DSM-5 criteria for hoarding disorder scored significantly higher on measures of disorganization and procrastination than did patients with nonhoarding obsessive-compulsive disorder or anxiety disorders, said Dr. Saxena, professor of psychiatry and director of the obsessive-compulsive disorders program at the University of California, San Diego.

The DSM-5 lists as the core symptoms of hoarding disorder difficulty in discarding possessions; perceived need to save items; excessive acquisition, clutter, and resultant distress; and impaired functioning. But while procrastination, disorganization, perfectionism, and indecisiveness aren’t included in the diagnostic criteria, Dr. Saxena said he and some other experts have considered those features to be characteristic of affected individuals. So he decided to formally test the strength of the associations.

He reported on 21 patients with hoarding disorder and 13 controls with nonhoarding OCD or an anxiety disorder. All subjects completed a battery of assessment tools, including the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale, the Frost Indecisiveness Scale, the Adult Inventory of Procrastination Scale, and three different measures of hoarding severity. Participants also completed a disorganization index based on their answers to three questions drawn from the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP-IV) Rating Scale: How often did you have difficulty organizing tasks and activities as a child? How disorganized are you in your thinking, planning, and time management? And how disorganized are your belongings at home?

Neither disorganization, procrastination, perfectionism, nor indecisiveness turned out to be associated with severity of nonhoarding OCD or anxiety disorder symptoms. Surprisingly, no significant differences were found between hoarding disorder patients and controls on the measures of indecisiveness or perfectionism, Dr. Saxena said. And the two groups did not differ in their levels of anxiety and depression.

However, levels of procrastination and disorganization were strongly correlated with hoarding severity as assessed via the Saving Inventory – Revised, the UCLA Hoarding Severity Scale, and the Hoarding Rating Scale. The hoarding disorder group’s average score on the disorganization index was 5.67, more than twice that of the 2.67 in the control group. And patients with hoarding disorder had an average Adult Inventory of Procrastination score of 50.9 out of a possible maximum of 75 points, compared with 41 in controls.

In a multivariate regression analysis, age and level of depression collectively explained 23.5% of the variance in hoarding severity scores in the study population. Disorganization independently explained an additional 29.9% of the variance, and procrastination accounted for another 19.1%, Dr. Saxena reported.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, which was funded by the university’s department of psychiatry.

AT THE ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point: