User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Study confirms it’s possible to catch COVID-19 twice

Researchers in Hong Kong say they’ve confirmed that a person can be infected with COVID-19 twice.

The new proof comes from a 33-year-old man in Hong Kong who first caught COVID-19 in March. He was tested for the coronavirus after he developed a cough, sore throat, fever, and a headache for 3 days. He stayed in the hospital until he twice tested negative for the virus in mid-April.

On Aug. 15, the man returned to Hong Kong from a recent trip to Spain and the United Kingdom, areas that have recently seen a resurgence of COVID-19 cases. At the airport, he was screened for COVID-19 with a test that checks saliva for the virus. He tested positive, but this time, had no symptoms. He was taken to the hospital for monitoring. His viral load – the amount of virus he had in his body – went down over time, suggesting that his immune system was taking care of the intrusion on its own.

The special thing about his case is that each time he was hospitalized, doctors sequenced the genome of the virus that infected him. It was slightly different from one infection to the next, suggesting that the virus had mutated – or changed – in the 4 months between his infections. It also proves that it’s possible for this coronavirus to infect the same person twice.

Experts with the World Health Organization responded to the case at a news briefing.

“What we are learning about infection is that people do develop an immune response. What is not completely clear yet is how strong that immune response is and for how long that immune response lasts,” said Maria Van Kerkhove, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist with the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland.

A study on the man’s case is being prepared for publication in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. Experts say the finding shouldn’t cause alarm, but it does have important implications for the development of herd immunity and efforts to come up with vaccines and treatments.

“This appears to be pretty clear-cut evidence of reinfection because of sequencing and isolation of two different viruses,” said Gregory Poland, MD, an expert on vaccine development and immunology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “The big unknown is how often is this happening,” he said. More studies are needed to learn whether this was a rare case or something that is happening often.

Past experience guides present

Until we know more, Dr. Poland said, the possibility of getting COVID-19 twice shouldn’t make anyone worry.

This also happens with other kinds of coronaviruses – the ones that cause common colds. Those coronaviruses change slightly each year as they circle the globe, which allows them to keep spreading and causing their more run-of-the-mill kind of misery.

It also happens with seasonal flu. It is the reason people have to get vaccinated against the flu year after year, and why the flu vaccine has to change slightly each year in an effort to keep up with the ever-evolving influenza virus.

“We’ve been making flu vaccines for 80 years, and there are clinical trials happening as we speak to find new and better influenza vaccines,” Dr. Poland said.

There has been other evidence the virus that causes COVID-19 can change this way, too. Researchers at Howard Hughes Medical Center, at Rockefeller University in New York, recently used a key piece of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – the genetic instructions for its spike protein – to repeatedly infect human cells. Scientists watched as each new generation of the virus went on to infect a new batch of cells. Over time, as it copied itself, some of the copies changed their genes to allow them to survive after scientists attacked them with neutralizing antibodies. Those antibodies are among the main weapons used by the immune system to recognize and disable a virus.

Though that study is still a preprint, which means it hasn’t yet been reviewed by outside experts, the authors wrote that their findings suggest the virus can change in ways that help it evade our immune system. If true, they wrote in mid-July, it means reinfection is possible, especially in people who have a weak immune response to the virus the first time they encounter it.

Good news

That seems to be true in the case of the man from Hong Kong. When doctors tested his blood to look for antibodies to the virus, they didn’t find any. That could mean that he either had a weak immune response to the virus the first time around, or that the antibodies he made during his first infection diminished over time. But during his second infection, he quickly developed more antibodies, suggesting that the second infection acted a little bit like a booster to fire up his immune system. That’s probably the reason he didn’t have any symptoms the second time, too.

That’s good news, Dr. Poland said. It means our bodies can get better at fighting off the COVID-19 virus and that catching it once means the second time might not be so bad.

But the fact that the virus can change quickly this way does have some impact on the effort to come up with a vaccine that works well.

“I think a potential implication of this is that we will have to give booster doses. The question is how frequently,” Dr. Poland said. That will depend on how fast the virus is changing, and how often reinfection is happening in the real world.

“I’m a little surprised at 4½ months,” Dr. Poland said, referencing the time between the Hong Kong man’s infections. “I’m not surprised by, you know, I got infected last winter and I got infected again this winter,” he said.

It also suggests that immune-based therapies such as convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies may be of limited help over time, since the virus might be changing in ways that help it outsmart those treatments.

Convalescent plasma is essentially a concentrated dose of antibodies from people who have recovered from a COVID-19 infection. As the virus changes, the antibodies in that plasma may not work as well for future infections.

Drug companies have learned to harness the power of monoclonal antibodies as powerful treatments against cancer and other diseases. Monoclonal antibodies, which are mass-produced in a lab, mimic the body’s natural defenses against a pathogen. Just like the virus can become resistant to natural immunity, it can change in ways that help it outsmart lab-created treatments. Some drug companies that are developing monoclonal antibodies to fight COVID-19 have already prepared for that possibility by making antibody cocktails that are designed to disable the virus by locking onto it in different places, which may help prevent it from developing resistance to those therapies.

“We have a lot to learn,” Dr. Poland said. “Now that the proof of principle has been established, and I would say it has with this man, and with our knowledge of seasonal coronaviruses, we need to look more aggressively to define how often this occurs.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Researchers in Hong Kong say they’ve confirmed that a person can be infected with COVID-19 twice.

The new proof comes from a 33-year-old man in Hong Kong who first caught COVID-19 in March. He was tested for the coronavirus after he developed a cough, sore throat, fever, and a headache for 3 days. He stayed in the hospital until he twice tested negative for the virus in mid-April.

On Aug. 15, the man returned to Hong Kong from a recent trip to Spain and the United Kingdom, areas that have recently seen a resurgence of COVID-19 cases. At the airport, he was screened for COVID-19 with a test that checks saliva for the virus. He tested positive, but this time, had no symptoms. He was taken to the hospital for monitoring. His viral load – the amount of virus he had in his body – went down over time, suggesting that his immune system was taking care of the intrusion on its own.

The special thing about his case is that each time he was hospitalized, doctors sequenced the genome of the virus that infected him. It was slightly different from one infection to the next, suggesting that the virus had mutated – or changed – in the 4 months between his infections. It also proves that it’s possible for this coronavirus to infect the same person twice.

Experts with the World Health Organization responded to the case at a news briefing.

“What we are learning about infection is that people do develop an immune response. What is not completely clear yet is how strong that immune response is and for how long that immune response lasts,” said Maria Van Kerkhove, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist with the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland.

A study on the man’s case is being prepared for publication in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. Experts say the finding shouldn’t cause alarm, but it does have important implications for the development of herd immunity and efforts to come up with vaccines and treatments.

“This appears to be pretty clear-cut evidence of reinfection because of sequencing and isolation of two different viruses,” said Gregory Poland, MD, an expert on vaccine development and immunology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “The big unknown is how often is this happening,” he said. More studies are needed to learn whether this was a rare case or something that is happening often.

Past experience guides present

Until we know more, Dr. Poland said, the possibility of getting COVID-19 twice shouldn’t make anyone worry.

This also happens with other kinds of coronaviruses – the ones that cause common colds. Those coronaviruses change slightly each year as they circle the globe, which allows them to keep spreading and causing their more run-of-the-mill kind of misery.

It also happens with seasonal flu. It is the reason people have to get vaccinated against the flu year after year, and why the flu vaccine has to change slightly each year in an effort to keep up with the ever-evolving influenza virus.

“We’ve been making flu vaccines for 80 years, and there are clinical trials happening as we speak to find new and better influenza vaccines,” Dr. Poland said.

There has been other evidence the virus that causes COVID-19 can change this way, too. Researchers at Howard Hughes Medical Center, at Rockefeller University in New York, recently used a key piece of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – the genetic instructions for its spike protein – to repeatedly infect human cells. Scientists watched as each new generation of the virus went on to infect a new batch of cells. Over time, as it copied itself, some of the copies changed their genes to allow them to survive after scientists attacked them with neutralizing antibodies. Those antibodies are among the main weapons used by the immune system to recognize and disable a virus.

Though that study is still a preprint, which means it hasn’t yet been reviewed by outside experts, the authors wrote that their findings suggest the virus can change in ways that help it evade our immune system. If true, they wrote in mid-July, it means reinfection is possible, especially in people who have a weak immune response to the virus the first time they encounter it.

Good news

That seems to be true in the case of the man from Hong Kong. When doctors tested his blood to look for antibodies to the virus, they didn’t find any. That could mean that he either had a weak immune response to the virus the first time around, or that the antibodies he made during his first infection diminished over time. But during his second infection, he quickly developed more antibodies, suggesting that the second infection acted a little bit like a booster to fire up his immune system. That’s probably the reason he didn’t have any symptoms the second time, too.

That’s good news, Dr. Poland said. It means our bodies can get better at fighting off the COVID-19 virus and that catching it once means the second time might not be so bad.

But the fact that the virus can change quickly this way does have some impact on the effort to come up with a vaccine that works well.

“I think a potential implication of this is that we will have to give booster doses. The question is how frequently,” Dr. Poland said. That will depend on how fast the virus is changing, and how often reinfection is happening in the real world.

“I’m a little surprised at 4½ months,” Dr. Poland said, referencing the time between the Hong Kong man’s infections. “I’m not surprised by, you know, I got infected last winter and I got infected again this winter,” he said.

It also suggests that immune-based therapies such as convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies may be of limited help over time, since the virus might be changing in ways that help it outsmart those treatments.

Convalescent plasma is essentially a concentrated dose of antibodies from people who have recovered from a COVID-19 infection. As the virus changes, the antibodies in that plasma may not work as well for future infections.

Drug companies have learned to harness the power of monoclonal antibodies as powerful treatments against cancer and other diseases. Monoclonal antibodies, which are mass-produced in a lab, mimic the body’s natural defenses against a pathogen. Just like the virus can become resistant to natural immunity, it can change in ways that help it outsmart lab-created treatments. Some drug companies that are developing monoclonal antibodies to fight COVID-19 have already prepared for that possibility by making antibody cocktails that are designed to disable the virus by locking onto it in different places, which may help prevent it from developing resistance to those therapies.

“We have a lot to learn,” Dr. Poland said. “Now that the proof of principle has been established, and I would say it has with this man, and with our knowledge of seasonal coronaviruses, we need to look more aggressively to define how often this occurs.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Researchers in Hong Kong say they’ve confirmed that a person can be infected with COVID-19 twice.

The new proof comes from a 33-year-old man in Hong Kong who first caught COVID-19 in March. He was tested for the coronavirus after he developed a cough, sore throat, fever, and a headache for 3 days. He stayed in the hospital until he twice tested negative for the virus in mid-April.

On Aug. 15, the man returned to Hong Kong from a recent trip to Spain and the United Kingdom, areas that have recently seen a resurgence of COVID-19 cases. At the airport, he was screened for COVID-19 with a test that checks saliva for the virus. He tested positive, but this time, had no symptoms. He was taken to the hospital for monitoring. His viral load – the amount of virus he had in his body – went down over time, suggesting that his immune system was taking care of the intrusion on its own.

The special thing about his case is that each time he was hospitalized, doctors sequenced the genome of the virus that infected him. It was slightly different from one infection to the next, suggesting that the virus had mutated – or changed – in the 4 months between his infections. It also proves that it’s possible for this coronavirus to infect the same person twice.

Experts with the World Health Organization responded to the case at a news briefing.

“What we are learning about infection is that people do develop an immune response. What is not completely clear yet is how strong that immune response is and for how long that immune response lasts,” said Maria Van Kerkhove, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist with the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland.

A study on the man’s case is being prepared for publication in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. Experts say the finding shouldn’t cause alarm, but it does have important implications for the development of herd immunity and efforts to come up with vaccines and treatments.

“This appears to be pretty clear-cut evidence of reinfection because of sequencing and isolation of two different viruses,” said Gregory Poland, MD, an expert on vaccine development and immunology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “The big unknown is how often is this happening,” he said. More studies are needed to learn whether this was a rare case or something that is happening often.

Past experience guides present

Until we know more, Dr. Poland said, the possibility of getting COVID-19 twice shouldn’t make anyone worry.

This also happens with other kinds of coronaviruses – the ones that cause common colds. Those coronaviruses change slightly each year as they circle the globe, which allows them to keep spreading and causing their more run-of-the-mill kind of misery.

It also happens with seasonal flu. It is the reason people have to get vaccinated against the flu year after year, and why the flu vaccine has to change slightly each year in an effort to keep up with the ever-evolving influenza virus.

“We’ve been making flu vaccines for 80 years, and there are clinical trials happening as we speak to find new and better influenza vaccines,” Dr. Poland said.

There has been other evidence the virus that causes COVID-19 can change this way, too. Researchers at Howard Hughes Medical Center, at Rockefeller University in New York, recently used a key piece of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – the genetic instructions for its spike protein – to repeatedly infect human cells. Scientists watched as each new generation of the virus went on to infect a new batch of cells. Over time, as it copied itself, some of the copies changed their genes to allow them to survive after scientists attacked them with neutralizing antibodies. Those antibodies are among the main weapons used by the immune system to recognize and disable a virus.

Though that study is still a preprint, which means it hasn’t yet been reviewed by outside experts, the authors wrote that their findings suggest the virus can change in ways that help it evade our immune system. If true, they wrote in mid-July, it means reinfection is possible, especially in people who have a weak immune response to the virus the first time they encounter it.

Good news

That seems to be true in the case of the man from Hong Kong. When doctors tested his blood to look for antibodies to the virus, they didn’t find any. That could mean that he either had a weak immune response to the virus the first time around, or that the antibodies he made during his first infection diminished over time. But during his second infection, he quickly developed more antibodies, suggesting that the second infection acted a little bit like a booster to fire up his immune system. That’s probably the reason he didn’t have any symptoms the second time, too.

That’s good news, Dr. Poland said. It means our bodies can get better at fighting off the COVID-19 virus and that catching it once means the second time might not be so bad.

But the fact that the virus can change quickly this way does have some impact on the effort to come up with a vaccine that works well.

“I think a potential implication of this is that we will have to give booster doses. The question is how frequently,” Dr. Poland said. That will depend on how fast the virus is changing, and how often reinfection is happening in the real world.

“I’m a little surprised at 4½ months,” Dr. Poland said, referencing the time between the Hong Kong man’s infections. “I’m not surprised by, you know, I got infected last winter and I got infected again this winter,” he said.

It also suggests that immune-based therapies such as convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies may be of limited help over time, since the virus might be changing in ways that help it outsmart those treatments.

Convalescent plasma is essentially a concentrated dose of antibodies from people who have recovered from a COVID-19 infection. As the virus changes, the antibodies in that plasma may not work as well for future infections.

Drug companies have learned to harness the power of monoclonal antibodies as powerful treatments against cancer and other diseases. Monoclonal antibodies, which are mass-produced in a lab, mimic the body’s natural defenses against a pathogen. Just like the virus can become resistant to natural immunity, it can change in ways that help it outsmart lab-created treatments. Some drug companies that are developing monoclonal antibodies to fight COVID-19 have already prepared for that possibility by making antibody cocktails that are designed to disable the virus by locking onto it in different places, which may help prevent it from developing resistance to those therapies.

“We have a lot to learn,” Dr. Poland said. “Now that the proof of principle has been established, and I would say it has with this man, and with our knowledge of seasonal coronaviruses, we need to look more aggressively to define how often this occurs.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Research examines links between ‘long COVID’ and ME/CFS

Some patients who had COVID-19 continue to have symptoms weeks to months later, even after they no longer test positive for the virus. In two recent reports – one published in JAMA in July and another published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in August – chronic fatigue was listed as the top symptom among individuals still feeling unwell beyond 2 weeks after COVID-19 onset.

Although some of the reported persistent symptoms appear specific to SARS-CoV-2 – such as cough, chest pain, and dyspnea – others overlap with the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, which is defined by substantial, profound fatigue for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and one or both of orthostatic intolerance and/or cognitive impairment. Although the etiology of ME/CFS is unclear, the condition commonly arises following a viral illness.

At the virtual meeting of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis August 21, the opening session was devoted to research documenting the extent to which COVID-19 survivors subsequently meet ME/CFS criteria, and to exploring underlying mechanisms.

“It offers a lot of opportunities for us to study potentially early ME/CFS and how it develops, but in addition, a lot of the research that has been done on ME/CFS may also provide answers for COVID-19,” IACFS/ME vice president Lily Chu, MD, said in an interview.

A hint from the SARS outbreak

This isn’t the first time researchers have seen a possible link between a coronavirus and ME/CFS, Harvey Moldofsky, MD, told attendees. To illustrate that point, Dr. Moldofsky, of the department of psychiatry (emeritus) at the University of Toronto, reviewed data from a previously published case-controlled study, which included 22 health care workers who had been infected in 2003 with SARS-CoV-1 and continued to report chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and disturbed and unrefreshing sleep with EEG-documented sleep disturbances 1-3 years following the illness. None had been able to return to work by 1 year.

“We’re looking at similar symptoms now” among survivors of COVID-19, Dr. Moldofsky said. “[T]he key issue is that we have no idea of its prevalence. … We need epidemiologic studies.”

Distinguishing ME/CFS from other post–COVID-19 symptoms

Not everyone who has persistent symptoms after COVID-19 will develop ME/CFS, and distinguishing between cases may be important.

Clinically, Dr. Chu said, one way to assess whether a patient with persistent COVID-19 symptoms might be progressing to ME/CFS is to ask him or her specifically about the level of fatigue following physical exertion and the timing of any fatigue. With ME/CFS, postexertional malaise often involves a dramatic exacerbation of symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and cognitive impairment a day or 2 after exertion rather than immediately following it. In contrast, shortness of breath during exertion isn’t typical of ME/CFS.

Objective measures of ME/CFS include low natural killer cell function (the test can be ordered from commercial labs but requires rapid transport of the blood sample), and autonomic dysfunction assessed by a tilt-table test.

While there is currently no cure for ME/CFS, diagnosing it allows for the patient to be taught “pacing” in which the person conserves his or her energy by balancing activity with rest. “That type of behavioral technique is valuable for everyone who suffers from a chronic disease with fatigue. It can help them be more functional,” Dr. Chu said.

If a patient appears to be exhibiting signs of ME/CFS, “don’t wait until they hit the 6-month mark to start helping them manage their symptoms,” she said. “Teaching pacing to COVID-19 patients who have a lot of fatigue isn’t going to harm them. As they get better they’re going to just naturally do more. But if they do have ME/CFS, [pacing] stresses their system less, since the data seem to be pointing to deficiencies in producing energy.”

Will COVID-19 unleash a new wave of ME/CFS patients?

Much of the session at the virtual meeting was devoted to ongoing studies. For example, Leonard Jason, PhD, of the Center for Community Research at DePaul University, Chicago, described a prospective study launched in 2014 that looked at risk factors for developing ME/CFS in college students who contracted infectious mononucleosis as a result of Epstein-Barr virus. Now, his team is also following students from the same cohort who develop COVID-19.

Because the study included collection of baseline biological samples, the results could help reveal predisposing factors associated with long-term illness from either virus.

Another project, funded by the Open Medicine Foundation, will follow patients who are discharged from the ICU following severe COVID-19 illness. Blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid will be collected from those with persistent symptoms at 6 months, along with questionnaire data. At 18-24 months, those who continue to report symptoms will undergo more intensive evaluation using genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics.

“We’re taking advantage of this horrible situation, hoping to understand how a serious viral infection might lead to ME/CFS,” said lead investigator Ronald Tompkins, MD, ScD, chief medical officer at the Open Medicine Foundation and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, Boston. The results, he said, “might give us insight into potential drug targets or biomarkers useful for prevention and treatment strategies.”

Meanwhile, Sadie Whittaker, PhD, head of the Solve ME/CFS initiative, described her organization’s new plan to use their registry to prospectively track the impact of COVID-19 on people with ME/CFS.

She noted that they’ve also teamed up with “long-COVID” communities including Body Politic. “Our goal is to form a coalition to study together or at least harmonize data … and understand what’s going on through the power of bigger sample sizes,” Dr. Whittaker said.

None of the speakers disclosed relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Some patients who had COVID-19 continue to have symptoms weeks to months later, even after they no longer test positive for the virus. In two recent reports – one published in JAMA in July and another published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in August – chronic fatigue was listed as the top symptom among individuals still feeling unwell beyond 2 weeks after COVID-19 onset.

Although some of the reported persistent symptoms appear specific to SARS-CoV-2 – such as cough, chest pain, and dyspnea – others overlap with the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, which is defined by substantial, profound fatigue for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and one or both of orthostatic intolerance and/or cognitive impairment. Although the etiology of ME/CFS is unclear, the condition commonly arises following a viral illness.

At the virtual meeting of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis August 21, the opening session was devoted to research documenting the extent to which COVID-19 survivors subsequently meet ME/CFS criteria, and to exploring underlying mechanisms.

“It offers a lot of opportunities for us to study potentially early ME/CFS and how it develops, but in addition, a lot of the research that has been done on ME/CFS may also provide answers for COVID-19,” IACFS/ME vice president Lily Chu, MD, said in an interview.

A hint from the SARS outbreak

This isn’t the first time researchers have seen a possible link between a coronavirus and ME/CFS, Harvey Moldofsky, MD, told attendees. To illustrate that point, Dr. Moldofsky, of the department of psychiatry (emeritus) at the University of Toronto, reviewed data from a previously published case-controlled study, which included 22 health care workers who had been infected in 2003 with SARS-CoV-1 and continued to report chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and disturbed and unrefreshing sleep with EEG-documented sleep disturbances 1-3 years following the illness. None had been able to return to work by 1 year.

“We’re looking at similar symptoms now” among survivors of COVID-19, Dr. Moldofsky said. “[T]he key issue is that we have no idea of its prevalence. … We need epidemiologic studies.”

Distinguishing ME/CFS from other post–COVID-19 symptoms

Not everyone who has persistent symptoms after COVID-19 will develop ME/CFS, and distinguishing between cases may be important.

Clinically, Dr. Chu said, one way to assess whether a patient with persistent COVID-19 symptoms might be progressing to ME/CFS is to ask him or her specifically about the level of fatigue following physical exertion and the timing of any fatigue. With ME/CFS, postexertional malaise often involves a dramatic exacerbation of symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and cognitive impairment a day or 2 after exertion rather than immediately following it. In contrast, shortness of breath during exertion isn’t typical of ME/CFS.

Objective measures of ME/CFS include low natural killer cell function (the test can be ordered from commercial labs but requires rapid transport of the blood sample), and autonomic dysfunction assessed by a tilt-table test.

While there is currently no cure for ME/CFS, diagnosing it allows for the patient to be taught “pacing” in which the person conserves his or her energy by balancing activity with rest. “That type of behavioral technique is valuable for everyone who suffers from a chronic disease with fatigue. It can help them be more functional,” Dr. Chu said.

If a patient appears to be exhibiting signs of ME/CFS, “don’t wait until they hit the 6-month mark to start helping them manage their symptoms,” she said. “Teaching pacing to COVID-19 patients who have a lot of fatigue isn’t going to harm them. As they get better they’re going to just naturally do more. But if they do have ME/CFS, [pacing] stresses their system less, since the data seem to be pointing to deficiencies in producing energy.”

Will COVID-19 unleash a new wave of ME/CFS patients?

Much of the session at the virtual meeting was devoted to ongoing studies. For example, Leonard Jason, PhD, of the Center for Community Research at DePaul University, Chicago, described a prospective study launched in 2014 that looked at risk factors for developing ME/CFS in college students who contracted infectious mononucleosis as a result of Epstein-Barr virus. Now, his team is also following students from the same cohort who develop COVID-19.

Because the study included collection of baseline biological samples, the results could help reveal predisposing factors associated with long-term illness from either virus.

Another project, funded by the Open Medicine Foundation, will follow patients who are discharged from the ICU following severe COVID-19 illness. Blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid will be collected from those with persistent symptoms at 6 months, along with questionnaire data. At 18-24 months, those who continue to report symptoms will undergo more intensive evaluation using genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics.

“We’re taking advantage of this horrible situation, hoping to understand how a serious viral infection might lead to ME/CFS,” said lead investigator Ronald Tompkins, MD, ScD, chief medical officer at the Open Medicine Foundation and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, Boston. The results, he said, “might give us insight into potential drug targets or biomarkers useful for prevention and treatment strategies.”

Meanwhile, Sadie Whittaker, PhD, head of the Solve ME/CFS initiative, described her organization’s new plan to use their registry to prospectively track the impact of COVID-19 on people with ME/CFS.

She noted that they’ve also teamed up with “long-COVID” communities including Body Politic. “Our goal is to form a coalition to study together or at least harmonize data … and understand what’s going on through the power of bigger sample sizes,” Dr. Whittaker said.

None of the speakers disclosed relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Some patients who had COVID-19 continue to have symptoms weeks to months later, even after they no longer test positive for the virus. In two recent reports – one published in JAMA in July and another published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in August – chronic fatigue was listed as the top symptom among individuals still feeling unwell beyond 2 weeks after COVID-19 onset.

Although some of the reported persistent symptoms appear specific to SARS-CoV-2 – such as cough, chest pain, and dyspnea – others overlap with the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, which is defined by substantial, profound fatigue for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, and one or both of orthostatic intolerance and/or cognitive impairment. Although the etiology of ME/CFS is unclear, the condition commonly arises following a viral illness.

At the virtual meeting of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis August 21, the opening session was devoted to research documenting the extent to which COVID-19 survivors subsequently meet ME/CFS criteria, and to exploring underlying mechanisms.

“It offers a lot of opportunities for us to study potentially early ME/CFS and how it develops, but in addition, a lot of the research that has been done on ME/CFS may also provide answers for COVID-19,” IACFS/ME vice president Lily Chu, MD, said in an interview.

A hint from the SARS outbreak

This isn’t the first time researchers have seen a possible link between a coronavirus and ME/CFS, Harvey Moldofsky, MD, told attendees. To illustrate that point, Dr. Moldofsky, of the department of psychiatry (emeritus) at the University of Toronto, reviewed data from a previously published case-controlled study, which included 22 health care workers who had been infected in 2003 with SARS-CoV-1 and continued to report chronic fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and disturbed and unrefreshing sleep with EEG-documented sleep disturbances 1-3 years following the illness. None had been able to return to work by 1 year.

“We’re looking at similar symptoms now” among survivors of COVID-19, Dr. Moldofsky said. “[T]he key issue is that we have no idea of its prevalence. … We need epidemiologic studies.”

Distinguishing ME/CFS from other post–COVID-19 symptoms

Not everyone who has persistent symptoms after COVID-19 will develop ME/CFS, and distinguishing between cases may be important.

Clinically, Dr. Chu said, one way to assess whether a patient with persistent COVID-19 symptoms might be progressing to ME/CFS is to ask him or her specifically about the level of fatigue following physical exertion and the timing of any fatigue. With ME/CFS, postexertional malaise often involves a dramatic exacerbation of symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and cognitive impairment a day or 2 after exertion rather than immediately following it. In contrast, shortness of breath during exertion isn’t typical of ME/CFS.

Objective measures of ME/CFS include low natural killer cell function (the test can be ordered from commercial labs but requires rapid transport of the blood sample), and autonomic dysfunction assessed by a tilt-table test.

While there is currently no cure for ME/CFS, diagnosing it allows for the patient to be taught “pacing” in which the person conserves his or her energy by balancing activity with rest. “That type of behavioral technique is valuable for everyone who suffers from a chronic disease with fatigue. It can help them be more functional,” Dr. Chu said.

If a patient appears to be exhibiting signs of ME/CFS, “don’t wait until they hit the 6-month mark to start helping them manage their symptoms,” she said. “Teaching pacing to COVID-19 patients who have a lot of fatigue isn’t going to harm them. As they get better they’re going to just naturally do more. But if they do have ME/CFS, [pacing] stresses their system less, since the data seem to be pointing to deficiencies in producing energy.”

Will COVID-19 unleash a new wave of ME/CFS patients?

Much of the session at the virtual meeting was devoted to ongoing studies. For example, Leonard Jason, PhD, of the Center for Community Research at DePaul University, Chicago, described a prospective study launched in 2014 that looked at risk factors for developing ME/CFS in college students who contracted infectious mononucleosis as a result of Epstein-Barr virus. Now, his team is also following students from the same cohort who develop COVID-19.

Because the study included collection of baseline biological samples, the results could help reveal predisposing factors associated with long-term illness from either virus.

Another project, funded by the Open Medicine Foundation, will follow patients who are discharged from the ICU following severe COVID-19 illness. Blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid will be collected from those with persistent symptoms at 6 months, along with questionnaire data. At 18-24 months, those who continue to report symptoms will undergo more intensive evaluation using genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics.

“We’re taking advantage of this horrible situation, hoping to understand how a serious viral infection might lead to ME/CFS,” said lead investigator Ronald Tompkins, MD, ScD, chief medical officer at the Open Medicine Foundation and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, Boston. The results, he said, “might give us insight into potential drug targets or biomarkers useful for prevention and treatment strategies.”

Meanwhile, Sadie Whittaker, PhD, head of the Solve ME/CFS initiative, described her organization’s new plan to use their registry to prospectively track the impact of COVID-19 on people with ME/CFS.

She noted that they’ve also teamed up with “long-COVID” communities including Body Politic. “Our goal is to form a coalition to study together or at least harmonize data … and understand what’s going on through the power of bigger sample sizes,” Dr. Whittaker said.

None of the speakers disclosed relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA clears first brain stimulation device to help smokers quit

The Food and Drug Administration has granted marketing approval for the BrainsWay deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) system to help adult smokers kick tobacco.

in a press release.

As previously reported, the system has already been approved by the FDA as a treatment for patients suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder.

The BrainsWay deep TMS system with H4-coil is designed to target addiction-related brain circuits.

It was evaluated as an aid to short-term smoking cessation in a prospective, double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled, multicenter study that involved 262 adults who had a history of smoking an average of more than 26 years and had attempted to quit multiple times but failed.

Active and sham treatments were performed daily 5 days a week for 3 weeks, followed by an additional three sessions once weekly for 3 weeks, for a total of 18 sessions over 6 weeks.

In the full intention-to-treat population (all 262 participants), the 4-week continuous quit rate (CQR, the primary endpoint) was higher in the active deep TMS group than in the sham TMS group (17.1% vs. 7.9%; P = .0238).

Among participants who completed the study, that is, those who underwent treatment for 4 weeks, who kept daily records, and for whom confirmatory urine samples were available, the CQR was 28.4% in the active deep TMS group, compared with 11.7% in the sham treatment group (P = .0063).

The average number of cigarettes smoked per day, as determined on the basis of daily records (secondary endpoint), was statistically significantly lower in the active deep TMS group, compared with the sham treatment group (P = .0311).

No patient suffered a seizure. The most common adverse event was headache, for which there was no statistical difference between the active and sham treatment groups. Other side effects included application site discomfort, back pain, muscle twitching, and discomfort.

“This FDA clearance represents a significant milestone for BrainsWay and our deep TMS platform technology,” Christopher von Jako, PhD, president and CEO of the company, said in the release.

“While other therapies are currently available, a substantial medical need continues to exist for treatments that can increase the continuous quit rate among smokers,” Dr. von Jako noted.

“Based on the compelling data from our large, randomized pivotal study of 262 subjects, we are confident that our deep TMS technology can play an important role in treating cigarette smokers who seek to quit,” he added.

The company plans a “controlled” U.S. market release of the system for this indication early next year.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted marketing approval for the BrainsWay deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) system to help adult smokers kick tobacco.

in a press release.

As previously reported, the system has already been approved by the FDA as a treatment for patients suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder.

The BrainsWay deep TMS system with H4-coil is designed to target addiction-related brain circuits.

It was evaluated as an aid to short-term smoking cessation in a prospective, double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled, multicenter study that involved 262 adults who had a history of smoking an average of more than 26 years and had attempted to quit multiple times but failed.

Active and sham treatments were performed daily 5 days a week for 3 weeks, followed by an additional three sessions once weekly for 3 weeks, for a total of 18 sessions over 6 weeks.

In the full intention-to-treat population (all 262 participants), the 4-week continuous quit rate (CQR, the primary endpoint) was higher in the active deep TMS group than in the sham TMS group (17.1% vs. 7.9%; P = .0238).

Among participants who completed the study, that is, those who underwent treatment for 4 weeks, who kept daily records, and for whom confirmatory urine samples were available, the CQR was 28.4% in the active deep TMS group, compared with 11.7% in the sham treatment group (P = .0063).

The average number of cigarettes smoked per day, as determined on the basis of daily records (secondary endpoint), was statistically significantly lower in the active deep TMS group, compared with the sham treatment group (P = .0311).

No patient suffered a seizure. The most common adverse event was headache, for which there was no statistical difference between the active and sham treatment groups. Other side effects included application site discomfort, back pain, muscle twitching, and discomfort.

“This FDA clearance represents a significant milestone for BrainsWay and our deep TMS platform technology,” Christopher von Jako, PhD, president and CEO of the company, said in the release.

“While other therapies are currently available, a substantial medical need continues to exist for treatments that can increase the continuous quit rate among smokers,” Dr. von Jako noted.

“Based on the compelling data from our large, randomized pivotal study of 262 subjects, we are confident that our deep TMS technology can play an important role in treating cigarette smokers who seek to quit,” he added.

The company plans a “controlled” U.S. market release of the system for this indication early next year.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted marketing approval for the BrainsWay deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) system to help adult smokers kick tobacco.

in a press release.

As previously reported, the system has already been approved by the FDA as a treatment for patients suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder.

The BrainsWay deep TMS system with H4-coil is designed to target addiction-related brain circuits.

It was evaluated as an aid to short-term smoking cessation in a prospective, double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled, multicenter study that involved 262 adults who had a history of smoking an average of more than 26 years and had attempted to quit multiple times but failed.

Active and sham treatments were performed daily 5 days a week for 3 weeks, followed by an additional three sessions once weekly for 3 weeks, for a total of 18 sessions over 6 weeks.

In the full intention-to-treat population (all 262 participants), the 4-week continuous quit rate (CQR, the primary endpoint) was higher in the active deep TMS group than in the sham TMS group (17.1% vs. 7.9%; P = .0238).

Among participants who completed the study, that is, those who underwent treatment for 4 weeks, who kept daily records, and for whom confirmatory urine samples were available, the CQR was 28.4% in the active deep TMS group, compared with 11.7% in the sham treatment group (P = .0063).

The average number of cigarettes smoked per day, as determined on the basis of daily records (secondary endpoint), was statistically significantly lower in the active deep TMS group, compared with the sham treatment group (P = .0311).

No patient suffered a seizure. The most common adverse event was headache, for which there was no statistical difference between the active and sham treatment groups. Other side effects included application site discomfort, back pain, muscle twitching, and discomfort.

“This FDA clearance represents a significant milestone for BrainsWay and our deep TMS platform technology,” Christopher von Jako, PhD, president and CEO of the company, said in the release.

“While other therapies are currently available, a substantial medical need continues to exist for treatments that can increase the continuous quit rate among smokers,” Dr. von Jako noted.

“Based on the compelling data from our large, randomized pivotal study of 262 subjects, we are confident that our deep TMS technology can play an important role in treating cigarette smokers who seek to quit,” he added.

The company plans a “controlled” U.S. market release of the system for this indication early next year.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA authorizes convalescent plasma for COVID-19

Convalescent plasma contains antibodies from the blood of recovered COVID-19 patients, which can be used to treat people with severe infections. Convalescent plasma has been used to treat patients for other infectious diseases. The authorization allows the plasma to be distributed in the United States and administered by health care providers.

“COVID-19 convalescent plasma is safe and shows promising efficacy,” Stephen Hahn, MD, commissioner of the FDA, said during a press briefing with President Donald Trump.

In April, the FDA approved a program to test convalescent plasma in COVID-19 patients at the Mayo Clinic, followed by other institutions. More than 90,000 patients have enrolled in the program, and 70,000 have received the treatment, Dr. Hahn said.

The data indicate that the plasma can reduce mortality in patients by 35%, particularly if patients are treated within 3 days of being diagnosed. Those who have benefited the most were under age 80 and not on artificial respiration, Alex Azar, the secretary for the Department of Health & Human Services, said during the briefing.

“We dream, in drug development, of something like a 35% mortality reduction,” he said.

But top scientists pushed back against the announcement.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, professor of molecular medicine, and executive vice president of Scripps Research, said the data the FDA are relying on did not come from the rigorous randomized, double-blind placebo trials that best determine if a treatment is successful.

Still, convalescent plasma is “one more tool added to the arsenal” of combating COVID-19, Mr. Azar said. The FDA will continue to study convalescent plasma as a COVID-19 treatment, Dr. Hahn added.

“We’re waiting for more data. We’re going to continue to gather data,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing, but the current results meet FDA criteria for issuing an emergency use authorization.

Convalescent plasma “may be effective in lessening the severity or shortening the length of COVID-19 illness in some hospitalized patients,” according to the FDA announcement. Potential side effects include allergic reactions, transfusion-transmitted infections, and transfusion-associated lung injury.

“We’ve seen a great deal of demand for this from doctors around the country,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing. “The EUA … allows us to continue that and meet that demand.”

Dr. Topol, however, said it appears Trump and the FDA are playing politics with science.

“There’s no evidence to support any survival benefit,” Dr. Topol said on Twitter. “Two days ago [the] FDA’s website stated there was no evidence for an EUA.”

The American Red Cross and other blood centers put out a national call for blood donors in July, especially for patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Mr. Azar and Dr. Hahn emphasized the need for blood donors during the press briefing.

“If you donate plasma, you could save a life,” Mr. Azar said.

The study has not been peer reviewed and did not include a placebo group for comparison, STAT reported.

Last week several health officials warned that the scientific data were too weak to warrant an emergency authorization, the New York Times reported.

A version of this originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Convalescent plasma contains antibodies from the blood of recovered COVID-19 patients, which can be used to treat people with severe infections. Convalescent plasma has been used to treat patients for other infectious diseases. The authorization allows the plasma to be distributed in the United States and administered by health care providers.

“COVID-19 convalescent plasma is safe and shows promising efficacy,” Stephen Hahn, MD, commissioner of the FDA, said during a press briefing with President Donald Trump.

In April, the FDA approved a program to test convalescent plasma in COVID-19 patients at the Mayo Clinic, followed by other institutions. More than 90,000 patients have enrolled in the program, and 70,000 have received the treatment, Dr. Hahn said.

The data indicate that the plasma can reduce mortality in patients by 35%, particularly if patients are treated within 3 days of being diagnosed. Those who have benefited the most were under age 80 and not on artificial respiration, Alex Azar, the secretary for the Department of Health & Human Services, said during the briefing.

“We dream, in drug development, of something like a 35% mortality reduction,” he said.

But top scientists pushed back against the announcement.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, professor of molecular medicine, and executive vice president of Scripps Research, said the data the FDA are relying on did not come from the rigorous randomized, double-blind placebo trials that best determine if a treatment is successful.

Still, convalescent plasma is “one more tool added to the arsenal” of combating COVID-19, Mr. Azar said. The FDA will continue to study convalescent plasma as a COVID-19 treatment, Dr. Hahn added.

“We’re waiting for more data. We’re going to continue to gather data,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing, but the current results meet FDA criteria for issuing an emergency use authorization.

Convalescent plasma “may be effective in lessening the severity or shortening the length of COVID-19 illness in some hospitalized patients,” according to the FDA announcement. Potential side effects include allergic reactions, transfusion-transmitted infections, and transfusion-associated lung injury.

“We’ve seen a great deal of demand for this from doctors around the country,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing. “The EUA … allows us to continue that and meet that demand.”

Dr. Topol, however, said it appears Trump and the FDA are playing politics with science.

“There’s no evidence to support any survival benefit,” Dr. Topol said on Twitter. “Two days ago [the] FDA’s website stated there was no evidence for an EUA.”

The American Red Cross and other blood centers put out a national call for blood donors in July, especially for patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Mr. Azar and Dr. Hahn emphasized the need for blood donors during the press briefing.

“If you donate plasma, you could save a life,” Mr. Azar said.

The study has not been peer reviewed and did not include a placebo group for comparison, STAT reported.

Last week several health officials warned that the scientific data were too weak to warrant an emergency authorization, the New York Times reported.

A version of this originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Convalescent plasma contains antibodies from the blood of recovered COVID-19 patients, which can be used to treat people with severe infections. Convalescent plasma has been used to treat patients for other infectious diseases. The authorization allows the plasma to be distributed in the United States and administered by health care providers.

“COVID-19 convalescent plasma is safe and shows promising efficacy,” Stephen Hahn, MD, commissioner of the FDA, said during a press briefing with President Donald Trump.

In April, the FDA approved a program to test convalescent plasma in COVID-19 patients at the Mayo Clinic, followed by other institutions. More than 90,000 patients have enrolled in the program, and 70,000 have received the treatment, Dr. Hahn said.

The data indicate that the plasma can reduce mortality in patients by 35%, particularly if patients are treated within 3 days of being diagnosed. Those who have benefited the most were under age 80 and not on artificial respiration, Alex Azar, the secretary for the Department of Health & Human Services, said during the briefing.

“We dream, in drug development, of something like a 35% mortality reduction,” he said.

But top scientists pushed back against the announcement.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, professor of molecular medicine, and executive vice president of Scripps Research, said the data the FDA are relying on did not come from the rigorous randomized, double-blind placebo trials that best determine if a treatment is successful.

Still, convalescent plasma is “one more tool added to the arsenal” of combating COVID-19, Mr. Azar said. The FDA will continue to study convalescent plasma as a COVID-19 treatment, Dr. Hahn added.

“We’re waiting for more data. We’re going to continue to gather data,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing, but the current results meet FDA criteria for issuing an emergency use authorization.

Convalescent plasma “may be effective in lessening the severity or shortening the length of COVID-19 illness in some hospitalized patients,” according to the FDA announcement. Potential side effects include allergic reactions, transfusion-transmitted infections, and transfusion-associated lung injury.

“We’ve seen a great deal of demand for this from doctors around the country,” Dr. Hahn said during the briefing. “The EUA … allows us to continue that and meet that demand.”

Dr. Topol, however, said it appears Trump and the FDA are playing politics with science.

“There’s no evidence to support any survival benefit,” Dr. Topol said on Twitter. “Two days ago [the] FDA’s website stated there was no evidence for an EUA.”

The American Red Cross and other blood centers put out a national call for blood donors in July, especially for patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Mr. Azar and Dr. Hahn emphasized the need for blood donors during the press briefing.

“If you donate plasma, you could save a life,” Mr. Azar said.

The study has not been peer reviewed and did not include a placebo group for comparison, STAT reported.

Last week several health officials warned that the scientific data were too weak to warrant an emergency authorization, the New York Times reported.

A version of this originally appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA updates hydrochlorothiazide label to include nonmelanoma skin cancer risk

and undergo regular skin cancer screening, according to updates to the medication’s label.

The skin cancer risk is small, however, and patients should continue taking HCTZ, a commonly used diuretic and antihypertensive drug, unless their doctor says otherwise, according to a U.S. Food and Drug Administration announcement about the labeling changes, which the agency approved on Aug. 20.

HCTZ, first approved in 1959, is associated with photosensitivity. Researchers identified a relationship between HCTZ and nonmelanoma skin cancer in postmarketing studies. Investigators have described dose-response patterns for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

An FDA analysis found that the risk mostly was increased for SCC. The drug was associated with approximately one additional case of SCC per 16,000 patients per year. For white patients who received a cumulative dose of 50,000 mg or more, the risk was greater. In this patient population, HCTZ was associated with about one additional case of SCC per 6,700 patients per year, according to the label.

Reliably estimating the frequency of nonmelanoma skin cancer and establishing a causal relationship to drug exposure is not possible with the available postmarketing data, the label notes

“Treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer is typically local and successful, with very low rates of death,” the FDA said. “Meanwhile, the risks of uncontrolled blood pressure can be severe and include life-threatening heart attacks or stroke. Given this information, patients should continue to use HCTZ and take protective skin care measures to reduce their risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer, unless directed otherwise from their health care provider.”

Patients can reduce sun exposure by using broad-spectrum sunscreens with a sun protection factor value of at least 15, limiting time in the sun, and wearing protective clothing, the agency advised.

and undergo regular skin cancer screening, according to updates to the medication’s label.

The skin cancer risk is small, however, and patients should continue taking HCTZ, a commonly used diuretic and antihypertensive drug, unless their doctor says otherwise, according to a U.S. Food and Drug Administration announcement about the labeling changes, which the agency approved on Aug. 20.

HCTZ, first approved in 1959, is associated with photosensitivity. Researchers identified a relationship between HCTZ and nonmelanoma skin cancer in postmarketing studies. Investigators have described dose-response patterns for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

An FDA analysis found that the risk mostly was increased for SCC. The drug was associated with approximately one additional case of SCC per 16,000 patients per year. For white patients who received a cumulative dose of 50,000 mg or more, the risk was greater. In this patient population, HCTZ was associated with about one additional case of SCC per 6,700 patients per year, according to the label.

Reliably estimating the frequency of nonmelanoma skin cancer and establishing a causal relationship to drug exposure is not possible with the available postmarketing data, the label notes

“Treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer is typically local and successful, with very low rates of death,” the FDA said. “Meanwhile, the risks of uncontrolled blood pressure can be severe and include life-threatening heart attacks or stroke. Given this information, patients should continue to use HCTZ and take protective skin care measures to reduce their risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer, unless directed otherwise from their health care provider.”

Patients can reduce sun exposure by using broad-spectrum sunscreens with a sun protection factor value of at least 15, limiting time in the sun, and wearing protective clothing, the agency advised.

and undergo regular skin cancer screening, according to updates to the medication’s label.

The skin cancer risk is small, however, and patients should continue taking HCTZ, a commonly used diuretic and antihypertensive drug, unless their doctor says otherwise, according to a U.S. Food and Drug Administration announcement about the labeling changes, which the agency approved on Aug. 20.

HCTZ, first approved in 1959, is associated with photosensitivity. Researchers identified a relationship between HCTZ and nonmelanoma skin cancer in postmarketing studies. Investigators have described dose-response patterns for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

An FDA analysis found that the risk mostly was increased for SCC. The drug was associated with approximately one additional case of SCC per 16,000 patients per year. For white patients who received a cumulative dose of 50,000 mg or more, the risk was greater. In this patient population, HCTZ was associated with about one additional case of SCC per 6,700 patients per year, according to the label.

Reliably estimating the frequency of nonmelanoma skin cancer and establishing a causal relationship to drug exposure is not possible with the available postmarketing data, the label notes

“Treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer is typically local and successful, with very low rates of death,” the FDA said. “Meanwhile, the risks of uncontrolled blood pressure can be severe and include life-threatening heart attacks or stroke. Given this information, patients should continue to use HCTZ and take protective skin care measures to reduce their risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer, unless directed otherwise from their health care provider.”

Patients can reduce sun exposure by using broad-spectrum sunscreens with a sun protection factor value of at least 15, limiting time in the sun, and wearing protective clothing, the agency advised.

‘The pandemic within the pandemic’

The coronavirus has infected millions of Americans and killed over 174,000. But could it be worse? Maybe.

“Racism is the pandemic within the pandemic,” Marc H. Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League, said in the 2020 “State of Black America, Unmasked” report.

“Black people with COVID-19 symptoms in February and March were less likely to get tested or treated than white patients,” he wrote.

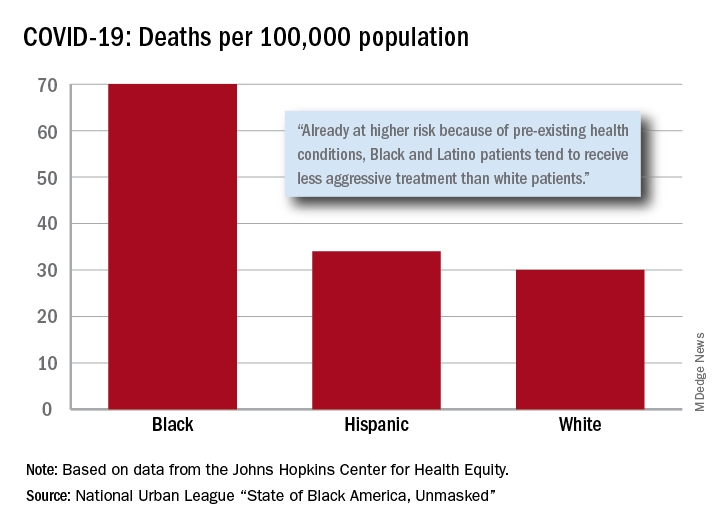

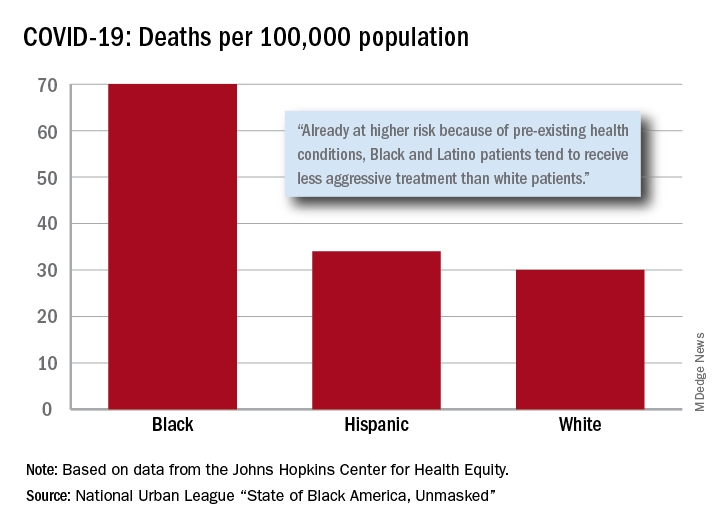

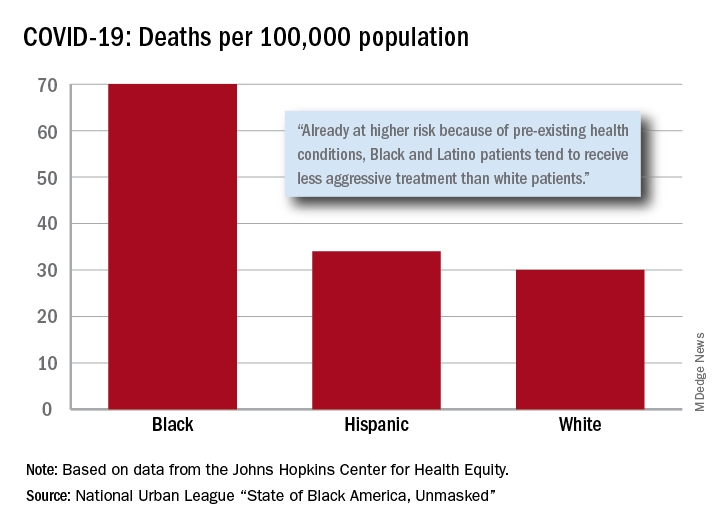

After less testing and less treatment, the next step seems inevitable. The death rate from COVID-19 is 70 per 100,000 population among Black Americans, compared with 30 per 100,000 for Whites and 34 per 100,000 for Hispanics, the league said based on data from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity.

Black and Hispanic patients with COVID-19 are more likely to have preexisting health conditions, but they “tend to receive less aggressive treatment than white patients,” the report noted. The lower death rate among Hispanics may be explained by the Black population’s greater age, although Hispanic Americans have a higher infection rate (73 per 10,000) than Blacks (62 per 10,000) or Whites (23 per 10,000).

Another possible explanation for the differences in infection rates: Blacks and Hispanics are less able to work at home because they “are overrepresented in low-wage jobs that offer the least flexibility and increase their risk of exposure to the coronavirus,” the league said.

Hispanics and Blacks also are more likely to be uninsured than Whites – 19.5% and 11.5%, respectively, vs. 7.5% – so “they tend to delay seeking treatment and are sicker than white patients when they finally do,” the league said. That may account for their much higher COVID-19 hospitalization rates: 213 per 100,000 for Blacks, 205 for Hispanics, and 46 for Whites.

“The silver lining during these dark times is that this pandemic has revealed our shared vulnerability and our interconnectedness. Many people are beginning to see that when others don’t have the opportunity to be healthy, it puts all of us at risk,” Lisa Cooper, MD, James F. Fries Professor of Medicine and Bloomberg Distinguished Professor in Health Equity at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an essay accompanying the report.

The coronavirus has infected millions of Americans and killed over 174,000. But could it be worse? Maybe.

“Racism is the pandemic within the pandemic,” Marc H. Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League, said in the 2020 “State of Black America, Unmasked” report.

“Black people with COVID-19 symptoms in February and March were less likely to get tested or treated than white patients,” he wrote.

After less testing and less treatment, the next step seems inevitable. The death rate from COVID-19 is 70 per 100,000 population among Black Americans, compared with 30 per 100,000 for Whites and 34 per 100,000 for Hispanics, the league said based on data from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity.

Black and Hispanic patients with COVID-19 are more likely to have preexisting health conditions, but they “tend to receive less aggressive treatment than white patients,” the report noted. The lower death rate among Hispanics may be explained by the Black population’s greater age, although Hispanic Americans have a higher infection rate (73 per 10,000) than Blacks (62 per 10,000) or Whites (23 per 10,000).

Another possible explanation for the differences in infection rates: Blacks and Hispanics are less able to work at home because they “are overrepresented in low-wage jobs that offer the least flexibility and increase their risk of exposure to the coronavirus,” the league said.

Hispanics and Blacks also are more likely to be uninsured than Whites – 19.5% and 11.5%, respectively, vs. 7.5% – so “they tend to delay seeking treatment and are sicker than white patients when they finally do,” the league said. That may account for their much higher COVID-19 hospitalization rates: 213 per 100,000 for Blacks, 205 for Hispanics, and 46 for Whites.

“The silver lining during these dark times is that this pandemic has revealed our shared vulnerability and our interconnectedness. Many people are beginning to see that when others don’t have the opportunity to be healthy, it puts all of us at risk,” Lisa Cooper, MD, James F. Fries Professor of Medicine and Bloomberg Distinguished Professor in Health Equity at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an essay accompanying the report.

The coronavirus has infected millions of Americans and killed over 174,000. But could it be worse? Maybe.

“Racism is the pandemic within the pandemic,” Marc H. Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League, said in the 2020 “State of Black America, Unmasked” report.

“Black people with COVID-19 symptoms in February and March were less likely to get tested or treated than white patients,” he wrote.

After less testing and less treatment, the next step seems inevitable. The death rate from COVID-19 is 70 per 100,000 population among Black Americans, compared with 30 per 100,000 for Whites and 34 per 100,000 for Hispanics, the league said based on data from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity.

Black and Hispanic patients with COVID-19 are more likely to have preexisting health conditions, but they “tend to receive less aggressive treatment than white patients,” the report noted. The lower death rate among Hispanics may be explained by the Black population’s greater age, although Hispanic Americans have a higher infection rate (73 per 10,000) than Blacks (62 per 10,000) or Whites (23 per 10,000).

Another possible explanation for the differences in infection rates: Blacks and Hispanics are less able to work at home because they “are overrepresented in low-wage jobs that offer the least flexibility and increase their risk of exposure to the coronavirus,” the league said.

Hispanics and Blacks also are more likely to be uninsured than Whites – 19.5% and 11.5%, respectively, vs. 7.5% – so “they tend to delay seeking treatment and are sicker than white patients when they finally do,” the league said. That may account for their much higher COVID-19 hospitalization rates: 213 per 100,000 for Blacks, 205 for Hispanics, and 46 for Whites.

“The silver lining during these dark times is that this pandemic has revealed our shared vulnerability and our interconnectedness. Many people are beginning to see that when others don’t have the opportunity to be healthy, it puts all of us at risk,” Lisa Cooper, MD, James F. Fries Professor of Medicine and Bloomberg Distinguished Professor in Health Equity at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an essay accompanying the report.

Patient visits post COVID-19

Has telemedicine found its footing?

When Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone, he accomplished something that many telegraph devotees never thought possible: the synchronous, bidirectional transmission of voice over electrical lines.

This was an incredible milestone in the advancement of mankind and enabled true revolutions in commerce, scientific collaboration, and human interaction. But Mr. Bell knew his invention didn’t represent the final advancement in telecommunication; he was quite prescient in imagining a day when individuals could see each other while speaking on the phone.

Many years later, what was once only a dream is now commonplace, and children growing up today can’t imagine a world where apps such as FaceTime and Skype don’t exist. Until recently, however, the medical community has been slow to adopt the idea of video interactions. This has dramatically changed because of the pandemic and the need for social distancing. It appears that telemedicine has found its footing, but whether it will remain popular once patients feel safe going to see their doctors in person again remains to be seen. This month, we’ll examine a few key issues that will determine the future of virtual medical visits.

Collect calling

The pandemic has wrought both human and economic casualties. With fear, job loss, and regulations leading to decreased spending, many large and small businesses have been and will continue to be unable to survive. Companies, including Brooks Brothers, Hertz, Lord and Taylor, GNC, and J.C. Penney, have declared bankruptcy.1 Medical practices and hospitals have taken cuts to their bottom line, and we’ve heard of many physician groups that have had to enact substantial salary cuts or even lay off providers – something previously unheard of. Recent months have demonstrated the health care community’s commitment to put patients first, but we simply cannot survive if we aren’t adequately reimbursed. Traditionally, this has been a significant roadblock toward the widespread adoption of telemedicine.

In most cases, these visits were not reimbursed at all. Thankfully, shortly after the coronavirus hit our shores, Medicare and Medicaid changed their policies, offering equal payment for video and in-person patient encounters. Most private insurers have followed suit, but the commitment to this payment parity appears – thus far – to be temporary. It is unclear that the financial support of telemedicine will continue post COVID-19, and this has many physicians feeling uncomfortable. In the meantime, many patients have come to prefer virtual visits, appreciating the convenience and efficiency.

Physicians don’t always have the same experience. Telemedicine can be technically challenging and take just as much – or sometimes more – time to navigate and document. Unless they are reimbursed equitably, providers will be forced to limit their use of virtual visits or not offer them at all. This leads to another issue: reliability.

‘Can you hear me now?’

Over the past several months, we have had the opportunity to use telemedicine firsthand and have spoken to many other physicians and patients about their experiences with it. The reports are all quite consistent: Most have had generally positive things to say. Still, some common concerns emerge when diving a bit deeper. Most notably are complaints about usability and reliability of the software.

While there are large telemedicine companies that have developed world-class cross-platform products, many in use today are proprietary and EHR dependent. As a result, the quality varies widely. Many EHR vendors were caught completely off guard by the sudden demand for telemedicine and are playing catch-up as they develop their own virtual visit platforms. While these vendor-developed platforms promise tight integration with patient records, some have significant shortcomings in stability when taxed under high utilization, including choppy video and garbled voice. This simply won’t do if telemedicine is to survive. It is incumbent on software developers and health care providers to invest in high-quality, reliable platforms on which to build their virtual visit offerings. This will ensure a more rapid adoption and the “staying power” of the new technology.

Dialing ‘0’ for the operator

Once seen as a “novelty” offered by only a small number of medical providers, virtual visits now represent a significant and ever-increasing percentage of patient encounters. The technology therefore must be easy to use. Given confidentiality and documentation requirements, along with the broad variety of available computing platforms and devices (e.g., PC, Mac, iOS, and Android), the process is often far from problem free. Patients may need help downloading apps, setting up webcams, or registering for the service. Providers may face issues with Internet connectivity or EHR-related delays.

It is critical that help be available to make the connection seamless and the experience a positive one. We are fortunate to work for a health care institution that has made this a priority, dedicating a team of individuals to provide real-time support to patients and clinicians. Small independent practices may not have this luxury, but we would encourage all providers to engage with their telemedicine or EHR vendors to determine what resources are available when problems arise, as they undoubtedly will.

Answering the call

Like the invention of the telephone, the advent of telemedicine is another milestone on the journey toward better communication with our patients, and it appears to be here to stay. Virtual visits won’t completely replace in-person care, nor minimize the benefit of human interaction, but they will continue to play an important role in the care continuum. By addressing the above concerns, we’ll lay a solid foundation for success and create a positive experience for physicians and patients alike.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Reference

1. A running list of companies that have filed for bankruptcy during the coronavirus pandemic. Fortune.

Has telemedicine found its footing?

Has telemedicine found its footing?

When Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone, he accomplished something that many telegraph devotees never thought possible: the synchronous, bidirectional transmission of voice over electrical lines.

This was an incredible milestone in the advancement of mankind and enabled true revolutions in commerce, scientific collaboration, and human interaction. But Mr. Bell knew his invention didn’t represent the final advancement in telecommunication; he was quite prescient in imagining a day when individuals could see each other while speaking on the phone.

Many years later, what was once only a dream is now commonplace, and children growing up today can’t imagine a world where apps such as FaceTime and Skype don’t exist. Until recently, however, the medical community has been slow to adopt the idea of video interactions. This has dramatically changed because of the pandemic and the need for social distancing. It appears that telemedicine has found its footing, but whether it will remain popular once patients feel safe going to see their doctors in person again remains to be seen. This month, we’ll examine a few key issues that will determine the future of virtual medical visits.

Collect calling