User login

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon, distinct clinical subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that comprises approximately 8% of all lymphoma diagnoses in the United States and Europe.1,2 Considered incurable, MCL often presents in advanced stages, particularly with involvement of the lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract in the form of lymphomatous polyps. MCL disproportionately affects males, and incidence rises with age, with a median age at diagnosis of 68 years.2 Historically, the prognosis of patients with MCL has been among the poorest among B-cell lymphoma patients, with a median overall survival (OS) of 3 to 5 years, and time to treatment failure (TTF) of 18 to 24 months, although this is improving in the modern era.3 Less frequently, patients with MCL display isolated bone marrow, peripheral blood, and splenic involvement. These cases tend to behave more indolently with longer survival.4,5 Recent advances in therapy have dramatically impacted treatment alternatives and outcomes for MCL. As such, the therapeutic and prognostic landscape of MCL is evolving rapidly.

PATHOGENESIS

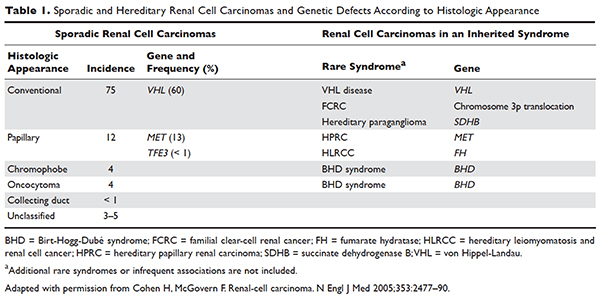

The histologic diagnosis of MCL by morphology alone is often challenging. Accurate diagnosis relies on immunohistochemical staining for the purposes of immunophenotyping.6 MCL typically expresses B-cell markers CD5 and CD20, and lacks both CD10 and CD23. The genetic hallmark of MCL is the t(11;14) (q13;q32) chromosomal translocation leading to upregulation of the cyclin D1 protein, a critical regulator of the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Specifically, the t(11;14) translocation, present in virtually all cases of MCL, juxtaposes the proto-oncogene CCND1 to the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene.7 Consequently, cyclin D1, normally not expressed in B lymphocytes, becomes constitutively overexpressed. This alteration is thought to facilitate the deregulation of the cell cycle at the G1-S phase transition.8

Gene expression profiling studies have underscored the importance of cell cycle deregulation in MCL, and high proliferation is associated with a worse prognosis.9 More than 50% of the genes associated with poor outcomes were derived from the “proliferation signature” that was more highly expressed in dividing cells. In the seminal Rosenwald study, a gene expression–based outcome model was constructed in which the proliferation signature average represents a linear variable that assigns a discrete probability of survival to an individual patient.9 The proliferative index, or proliferative signature, of MCL can be estimated by the percentage of Ki-67–positive cells present in the tumor through immunohistochemistry. This is often used as a marker of poor outcomes, and as a surrogate for the proliferative signature in MCL that can be incorporated into clinical practice (as opposed to gene expression profiling). Statistically significant differences in OS have emerged between groups of MCL patients with Ki-67–positive cells comprising less than 30% of their tumor sample (favorable) and those with Ki-67–positive cells comprising 30% or greater (unfavorable).10

Recent data has also identified the importance of the transcription factor SOX 11 (SRY-related HMG-box), which regulates multiple cellular transcriptional events, including cell proliferation and differentiation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis.11 MCL expressing SOX 11 behaves more aggressively than MCL variants lacking SOX 11 expression, and tends to accumulate more genetic alterations.12 Moreover, lack of SOX 11 expression characterizes a subset of MCL that does not carry the t(11;14) translocation.

DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

CASE PRESENTATION

A 62-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with cervical lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and early satiety over the past several months. He is otherwise in good health. His Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status is 1. On physical examination, 3-cm lymphadenopathy in the bilateral cervical chain is noted. Bilateral axillary lymph nodes measure 2 to 4 cm. His spleen is enlarged and is palpable at approximately 5 cm below the costal margin. A complete blood count reveals a total white blood cell (WBC) count of 14,000 cells/μL, with 68% lymphocytes and a normal distribution of neutrophils. Hemoglobin is 11 g/dL, and platelet count is 112,000/μL. The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level is 322 U/L (upper limit of normal: 225 U/L).

• How is MCL diagnosed?

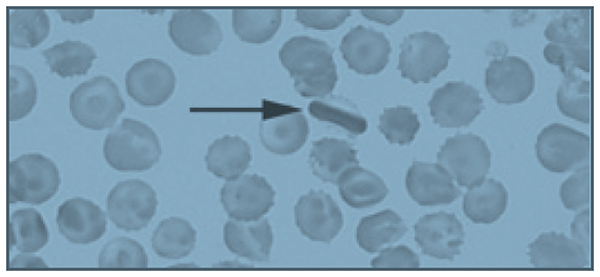

Diagnosis of MCL requires review by expert hematopathologists.13 Whenever possible, an excisional biopsy should be performed for the adequate characterization of lymph node architecture and evaluation by immunohistochemistry. Aside from the characteristic expression of CD5 and CD20 and absence of CD23, MCL should express cyclin D1, which reflects t(11;14). If cyclin D1 is inconclusive or unavailable, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) for t(11;14) should be performed.8 Patients often have circulating malignant lymphocytes, or leukemic phase MCL. Flow cytometry of the peripheral blood can detect traditional surface markers, and FISH can also be performed on circulating abnormal lymphocytes.

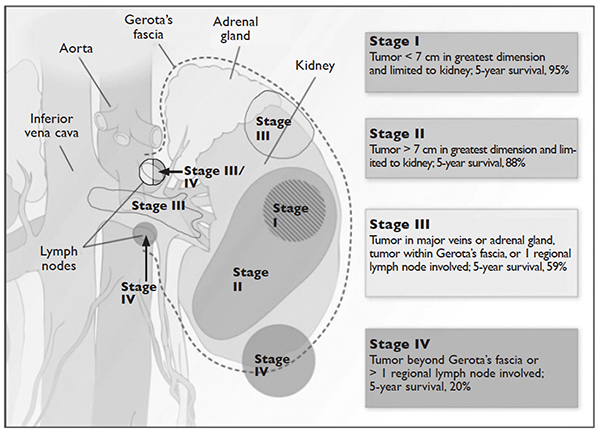

For disease staging, bone marrow biopsy and aspiration are required. Radiographic staging using computed tomography (CT) scans and/or positron emission tomography (PET) scans had traditionally followed the Ann Arbor staging system, but recently the Lugano classification has emerged, which delineates only early or advanced stage.14 Gastrointestinal evaluation of MCL with endoscopy and colonoscopy with blind biopsies has been recommended to evaluate for the presence of lymphomatous polyps, but this is not an absolute requirement.15

RISK STRATIFICATION

At diagnosis, patients should undergo risk stratification in order to understand prognosis and possibly guide treatment. In MCL, the MCL international prognostic index (MIPI) is used. The MIPI is a prognostic tool developed exclusively for patients with MCL using data from 455 patients with advanced-stage MCL treated within 3 European clinical trials.16 The MIPI classified patients into risk groups based on age, ECOG performance status, LDH level, and WBC count. Patients were categorized into low-risk (44% of patients, median OS not reached), intermediate-risk (35%, median OS 51 months), and high-risk groups (21%, median OS 29 months). This is done through a logarithmic calculation, which can be accessed through online calculators (a prototype example can be found at www.qxmd.com/calculate-online/hematology/prognosis-mantle-cell-lymphoma-mipi). Cell proliferation using the Ki-67 index was evaluated in an exploratory analysis (the biologic [“B”] MIPI), and also demonstrated strong prognostic relevance.16 Currently, treatment of MCL patients is not stratified by MIPI outside of a clinical trial, but this useful tool assists in assessing patient prognosis and has been validated for use with both conventional chemoimmunotherapy and in the setting of autologous stem cell transplant (autoSCT).16,17 At this point in time, the MIPI score is not used to stratify treatment, although some clinical trials are incorporating the use of the MIPI score at diagnosis. Nonetheless, given its prognostic importance, the MIPI should be performed for all MCL patients undergoing staging and evaluation for treatment to establish disease risk.

As noted, the proliferative signature, represented by the Ki-67 protein, is also highly prognostic in MCL. Ki-67 is expressed in the late G1, S, G2, and M phases of the cell cycle. The Ki-67 index is defined by the hematopathologist as the percentage of lymphoma cells staining positive for Ki-67 protein, based on the number of cells per high-power field. There is significant interobserver variability in this process, which can be minimized by assessing Ki-67 quantitatively using computer software. The prognostic significance of Ki-67 at diagnosis was established in large studies of MCL patient cohorts, with survival differing by up to 3 years.18,19 Determann et al demonstrated the utility of the proliferative index in patients with MCL treated with standard chemoimmunotherapy.10 In this study, 249 patients with advanced-stage MCL treated within randomized trials conducted by the European MCL Network were analyzed. The Ki-67 index was found to be extremely prognostic of OS, independent of other clinical risk factors, including the MIPI score. As a continuous variable, Ki-67 indices of greater than 10% correlated with poor outcomes. The Ki-67 index has also been confirmed as prognostic in relapsed MCL.20 It is important to note that, as a unique feature, the Ki-67 index has remained an independent prognostic factor, even when incorporated into the “B” MIPI.

TREATMENT

CASE CONTINUED

The patient undergoes an excisional biopsy of a cervical lymph node, which demonstrates an abnormal proliferation of small-medium–sized lymphocytes with slightly irregular nuclear contours. Immunohistochemistry shows that the abnormal lymphocytes are positive for CD20 and CD5, negative for CD10 and CD23, and diffusely positive for cyclin D1, consistent with a diagnosis of MCL. The proliferative index, as measured by the Ki-67 immunostain, is 40%. A bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are then obtained, which show a clonal population of B lymphocytes expressing the same immunophenotype as the lymph node (positive for CD20 and CD5, negative for CD10 and CD23, cyclin D1 positive). A CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast is obtained, along with a PET scan. These studies identify extensive hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy in the bilateral cervical chains, supraclavicular areas, mediastinum, and hilum. Mesenteric lymph nodes are also enlarged and hypermetabolic, as are retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The spleen is noted to be enlarged with multiple hypermetabolic lesions. Based on the presence of extensive lymphadenopathy as well as bone marrow involvement, the patient is diagnosed with stage IV MCL. He undergoes risk-stratification with the MIPI. His MIPI score is 6.3, high risk.

• What is the approach to upfront therapy for MCL?

FRONTLINE THERAPY

Role of Watchful Waiting

A small proportion of MCL patients have indolent disease that can be observed. This population is more likely to have leukemic-phase MCL with circulating lymphocytes, splenomegaly, and bone marrow involvement and absent or minimal lymphadenopathy.4,5 A retrospective study of 97 patients established that deferment of initial therapy in MCL is acceptable in some patients.5 In this study, approximately one third of patients with MCL were observed for more than 3 months before initiating systemic therapy, and the median time to treatment for the observation group was 12 months. Most patients undergoing observation had a low-risk MIPI. Patients were not harmed by observation, as no OS differences were observed among groups. This study underscores that deferred treatment can be an acceptable alternative in selected MCL patients for a short period of time. In practice, the type of patient who would be appropriate for this approach is someone who is frail, elderly, and with multiple comorbidities. Additionally, expectant observation could be considered for patients with limited-stage or low-volume MCL, low Ki-67 index, and low-risk MIPI scores.

Approach to Therapy

Treatment of MCL is generally approached by evaluating patient age and fitness for treatment. While there is no accepted standard, for younger patients healthy enough to tolerate aggressive approaches, treatment often involves an intensive cytarabine-containing regimen, which is consolidated with an autoSCT. This approach results in the longest remission duration, with some series suggesting a plateau in survival after 5 years, with no relapses.21 Nonintensive conventional chemotherapy alone is often reserved for the frailer or older patient. Given that remission durations with chemotherapy alone in MCL are short, goals of treatment focus on maximizing benefit and remission duration and minimizing risk of toxicity.

Standard Chemotherapy: Elderly and/or Frail Patients

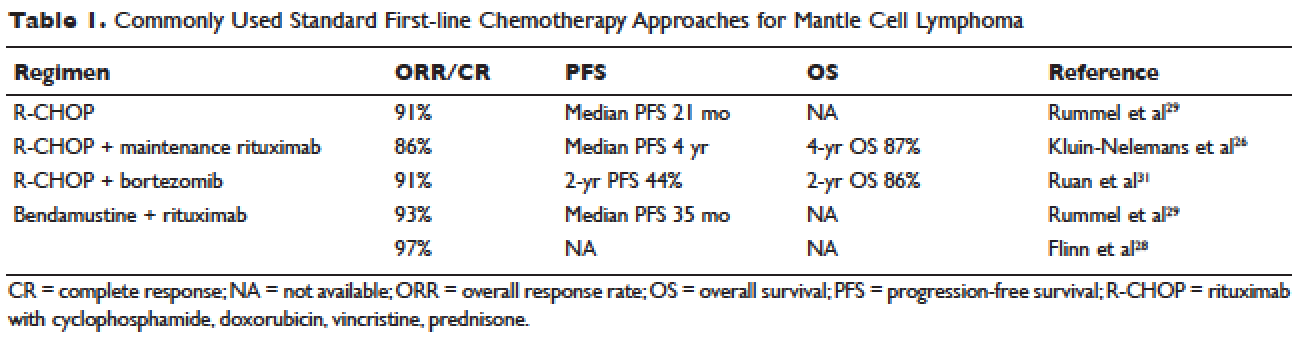

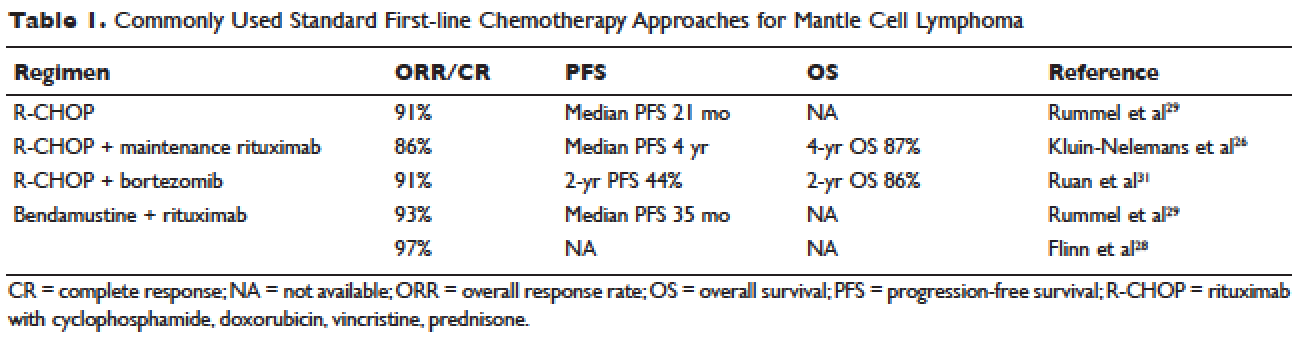

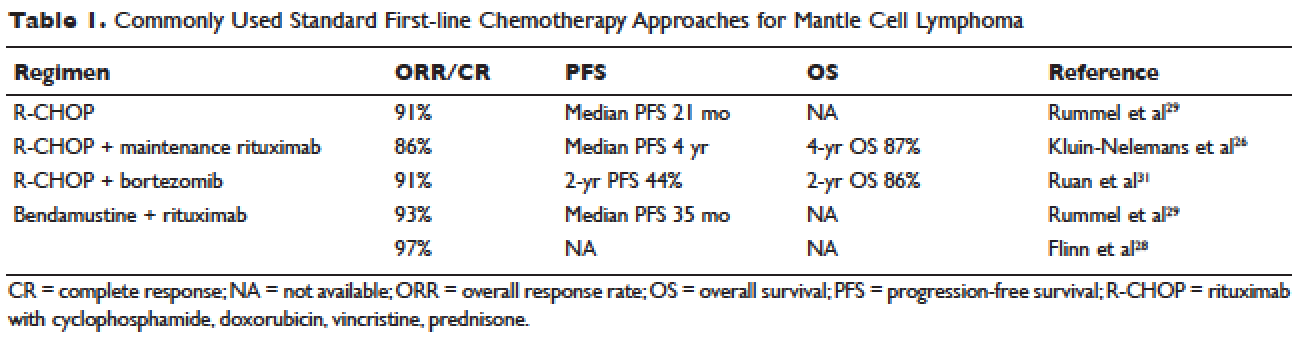

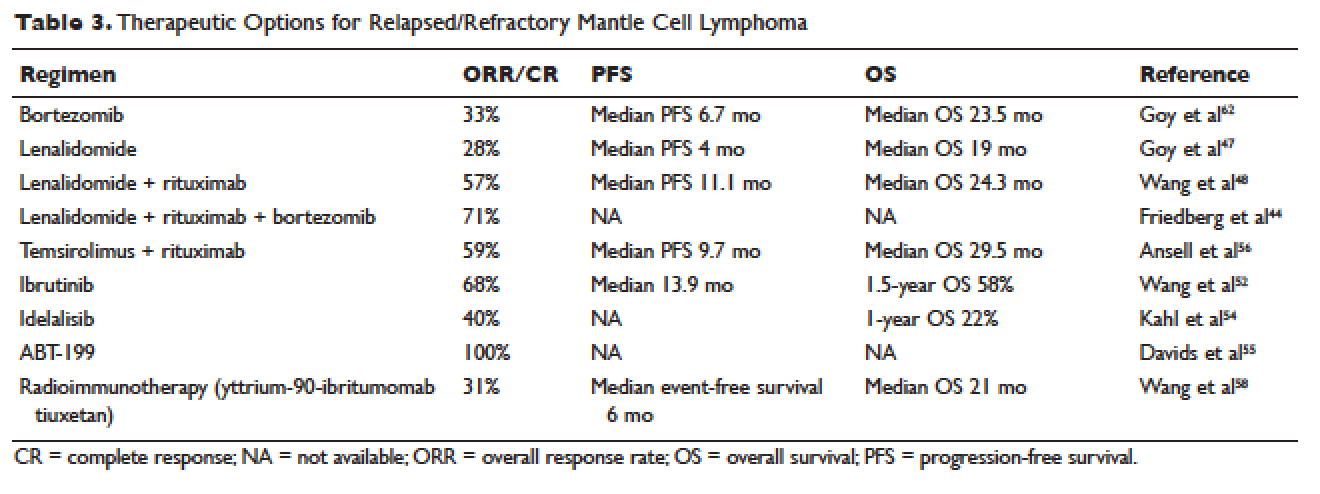

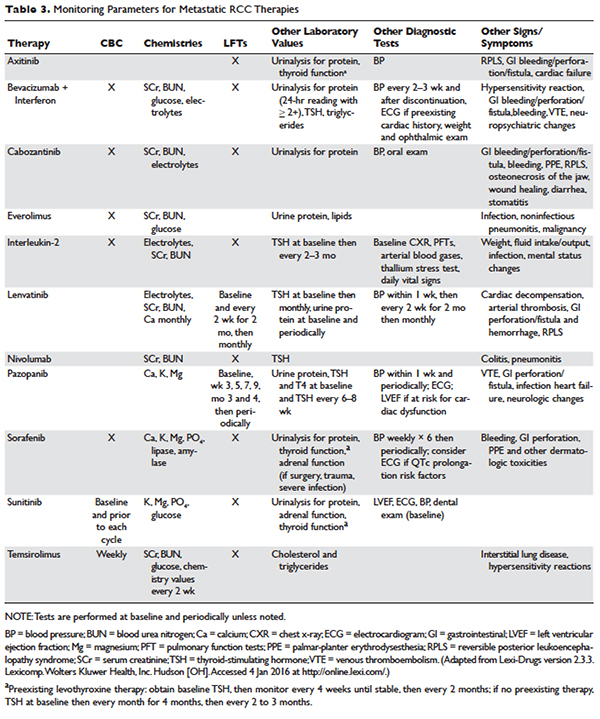

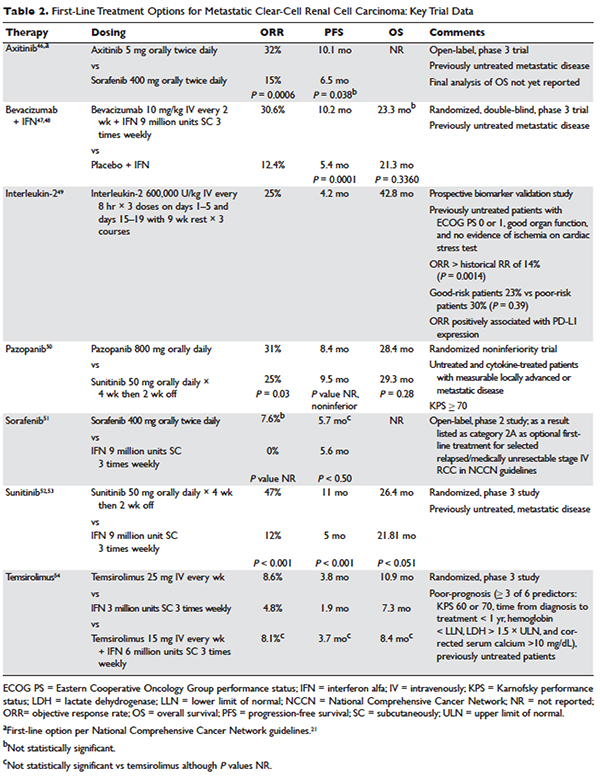

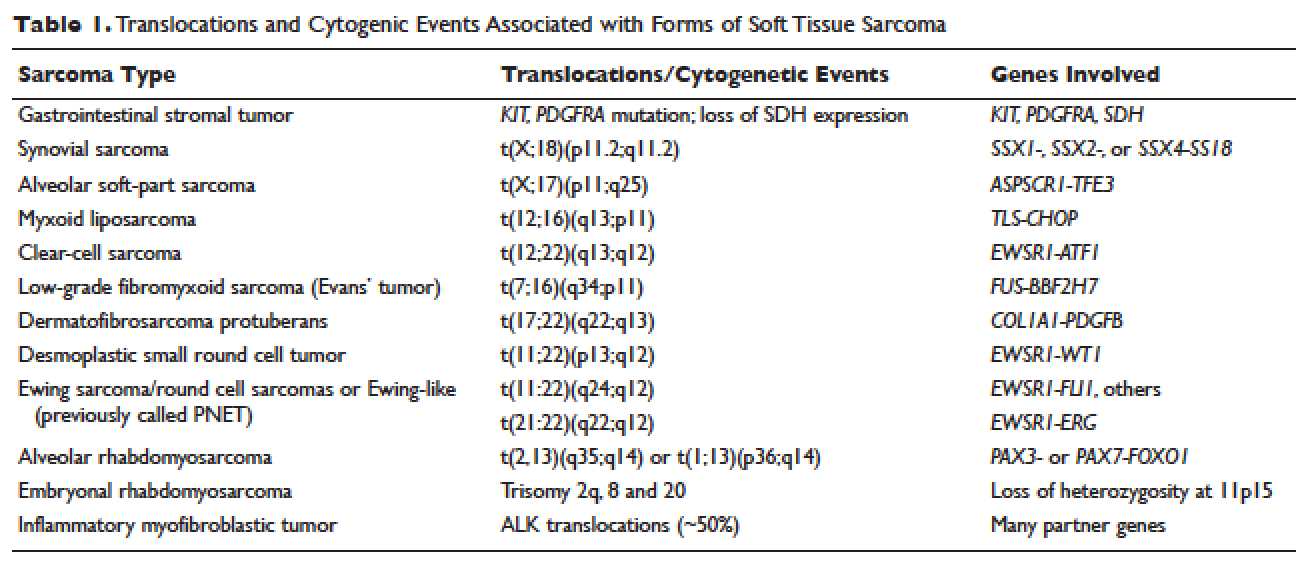

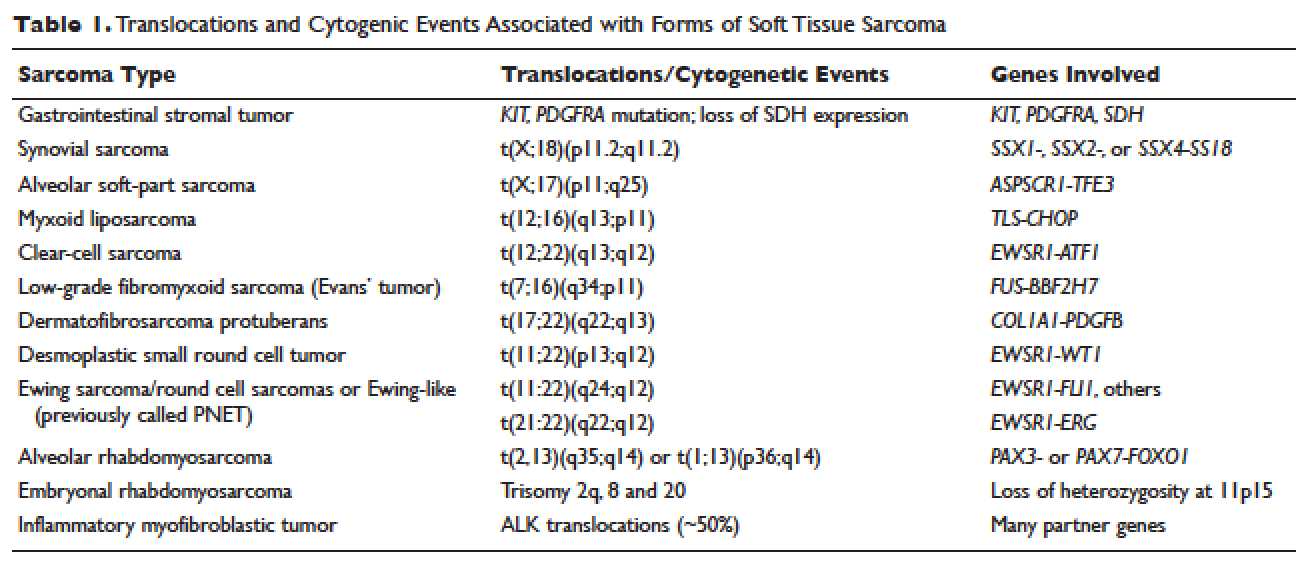

Conventional chemotherapy alone for the treatment of MCL results in a 70% to 85% overall response rate (ORR) and 7% to 30% complete response (CR) rate.22 Rituximab, a mouse humanized monoclonal IgG1 anti-CD20 antibody, is used as standard of care in combination with chemotherapy, since its addition has been found to increase response rates and extend both progression-free survival (PFS) and OS compared to chemotherapy alone.23,24 However, chemoimmunotherapy approaches do not provide long-term control of MCL and are considered noncurative. Various regimens have been studied and include anthracycline-containing regimens such as R-CHOP (rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone),22 combination chemotherapy with antimetabolites such as R-hyper-CVAD (hyper-fractionated rituximab with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine),25 purine analogue–based regimens such as R-FC (rituximab with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide),26 bortezomib-containing regimens,27 and alkylator-based treatment with BR (bendamustine and rituximab) (Table 1).28,29 Among these, the most commonly used are R-CHOP and BR.

Two large randomized studies compared R-CHOP for 6 cycles to BR for 6 cycles in patients with indolent NHL and MCL. Among MCL patients, BR resulted in superior PFS compared to R-CHOP (69 months versus 26 months) but no benefit in OS.28,29 The ORR to R-CHOP was approximately 90%, with a PFS of 21 months in the Rummel et al study.29 This study included more than 80 centers in Germany and enrolled 549 patients with MCL, follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion. Among these, 46 patients received BR and 48 received R-CHOP (18% for both, respectively). It should be noted that patients in the BR group had significantly less toxicity and experienced fewer side effects than did those in the R-CHOP group. Similarly, BR-treated patients had a lower frequency of hematologic side effects and infections of any grade. However, drug-associated skin reactions and allergies were more common with BR compared to R-CHOP. The study by Flinn and colleagues was an international randomized, noninferiority phase 3 study designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of BR compared with R-CHOP or R-CVP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone) for treatment-naive patients with MCL or other indolent NHL. The primary endpoint was CR. In this study, BR was found to be noninferior to R-CHOP and R-CVP based on CR rate (31% versus 25%, respectively; P = 0.0225). Response rates in general were high: 97% for BR and 91% for R-CHOP/R-CVP (P = 0.0102). Here, BR-treated patients experienced more nausea, emesis, and drug-induced hypersensitivity compared to the R-CHOP and R-CVP groups.

Another approach studied in older patients is the use of R-CHOP with rituximab maintenance. In a large European study, 560 patients 60 years of age or older with advanced-stage MCL were randomly assigned to either R-FC (rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide) every 28 days for 6 cycles, or R-CHOP every 21 days for 8 cycles. Patients who had a response then underwent a second randomization, with one group receiving rituximab maintenance therapy. Maintenance was continued until progression of disease. Patients in this study were not eligible for high-dose chemotherapy and autoSCT. The study found that rates of CR were similar with both R-FC and R-CHOP (40% and 34%, respectively; P = 0.10). However, the R-FC arm underperformed in several arenas. Disease progression occurred more frequently with R-FC (14% versus 5% with R-CHOP), and OS was shorter (4-year OS, 47% versus 62%; P = 0.005, respectively). More patients also died in the R-FC group, and there was greater hematologic toxicity compared to R-CHOP. At 4 years, 58% of the patients receiving rituximab remained in remission. Among patients who responded to R-CHOP, rituximab maintenance led to a benefit in OS, reducing the risk of progression or death by 45%.26 At this time, studies are ongoing to establish the benefit of rituximab maintenance after BR.

Bendamustine in combination with other agents has also been studied in the frontline setting. Visco and colleagues evaluated the combination of bendamustine with rituximab and cytarabine (R-BAC) in older patients with MCL (age 65 or older).63 This phase 2, two-stage study enrolled 40 patients and had a dose-finding arm for cytarabine in combination with BR. It permitted relapsed/refractory patients, but 50% had newly diagnosed, previously untreated MCL. The regimen had an impressive ORR of 100%, with CR rates of 95% for previously untreated patients. PFS at 2 years was 95%. R-BAC was well tolerated, with the primary toxicity being reversible myelosuppression.

BR was combined with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and dexamethasone in a phase 2 study.64 This Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA) study evaluated 76 patients with newly diagnosed MCL older than age 65 years. BR was administered in standard doses (bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 and rituximab 375 mg/m² IV on day 1) and bortezomib was administered subcutaneously on days 1, 4, 8, and 11, with acyclovir for viral prophylaxis. Patients received 6 cycles. The ORR was 87% and the CR was 60%. Patients experienced toxicity, and not all bortezomib doses were administered due to neurotoxic or hematologic side effects.

A randomized phase 3 study compared R-CHOP to the VR-CAP regimen (R-CHOP regimen but bortezomib replaces vincristine on days 1, 4, 8, 11, at 1.3 mg/m2) in 487 newly diagnosed MCL patients.27 Median PFS was superior in the VR-CAP group compared with R-CHOP (14.4 months versus 24.7 months, respectively). Additionally, rates of CR were superior in the VR-CAP group (53% compared to 42% with R-CHOP). However, there was more hematologic toxicity with VR-CAP. On the basis of these findings, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved bortezomib for the frontline treatment of MCL.

Other chemoimmunotherapy combinations containing bortezomib have been studied in frontline MCL treatment, with promising results. These include bortezomib in combination with R-CHOP or modified R-hyper-CVAD, as well as bortezomib in combination with CHOP-like treatments and purine analogues.27,30–32 The ongoing ECOG 1411 study is currently evaluating bortezomib added to BR for induction therapy of newly diagnosed MCL in a 4-arm randomized trial. Patients receive BR with or without bortezomib during induction and are then randomly assigned to maintenance with either rituximab alone or rituximab with lenalidomide. Other novel combination agents are actively being studied in frontline MCL treatment, including lenalidomide and rituximab and BR with lenalidomide.

Intensification of Therapy and AutoSCT: Fitter and/or Younger Patients

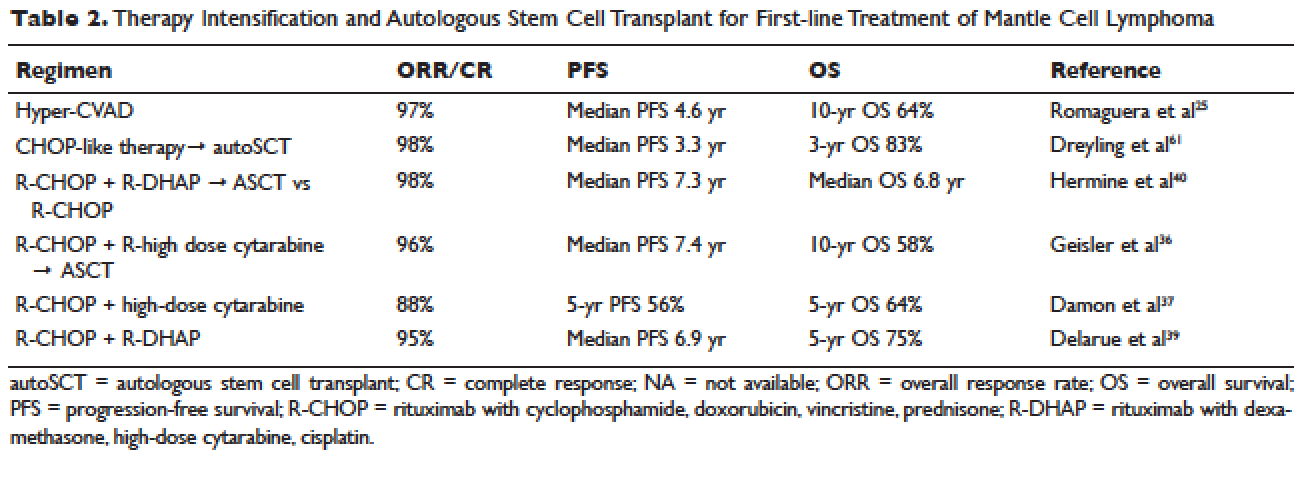

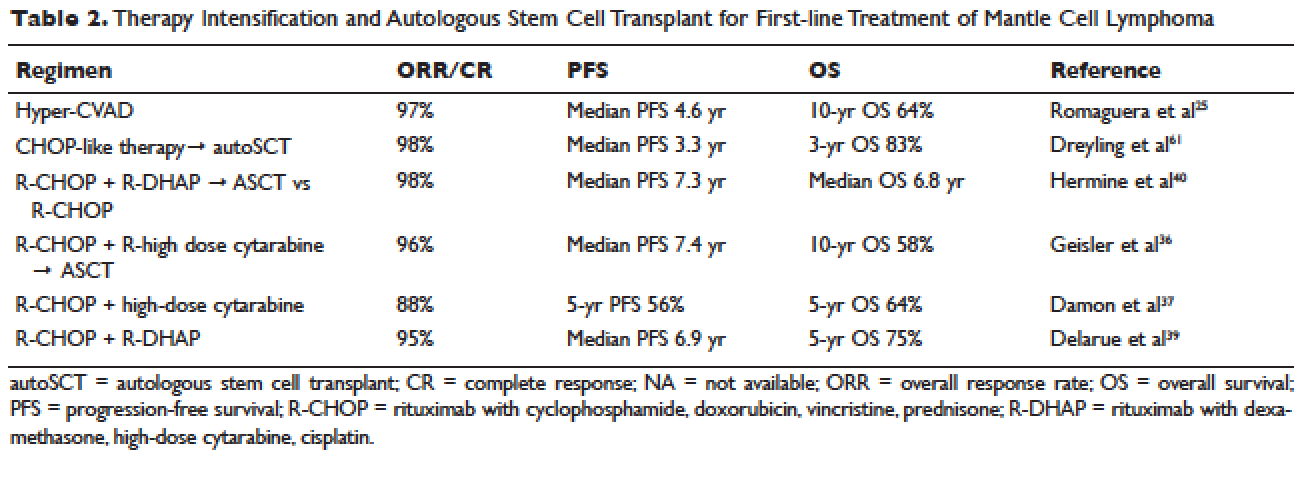

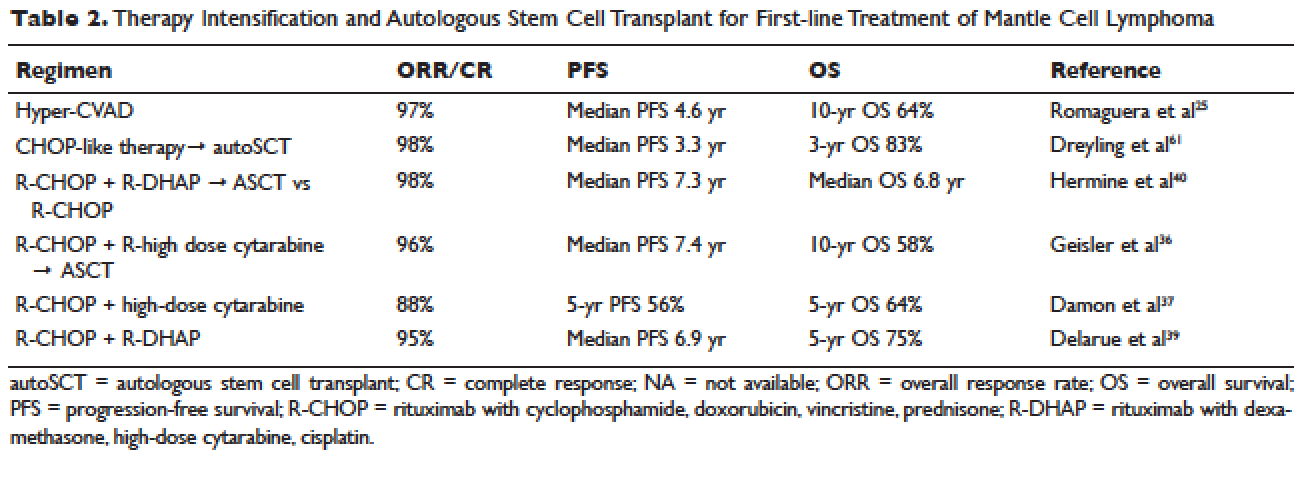

Short response duration has created the need for post-remission therapy in MCL. One approach to improve remission duration in MCL is to intensify induction through the use of cytarabine-containing regimens and/or consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy, typically using BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) and autoSCT (Table 2). The cytarabine-containing R-hyper-CVAD regimen, developed at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, resulted in a 97% ORR and an 87% CR rate, with TTF of nearly 5 years. However, nearly one third of patients were unable to complete treatment due to toxicity, and 5 patients developed secondary myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia.33 The feasibility of this R-hyper-CVAD regimen was tested in a multicenter cooperative group setting, but similar results were not seen; in this study, nearly 40% of patients were unable to complete the full scheduled course of treatment due to toxicity.34

Other ways to intensify therapy in MCL involve adding a second non-cross-resistant cytarabine-containing regimen to R-CHOP after remission, such as DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin), followed by consolidation with an autoSCT. A retrospective registry from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network sought to compare the efficacy of different treatment approaches in the frontline setting. They studied 167 patients with MCL and compared 4 groups: treatment with R-hyper-CVAD, either with or without autoSCT, and treatment with R-CHOP, either with or without autoSCT. This study found that in patients younger than 65, R-CHOP followed by autoSCT or R-hyper-CVAD without autoSCT resulted in similar PF and OS, but was superior to R-CHOP alone for newly diagnosed MCL patients.35 These data support more intensive regimens in younger and fitter patients. Several other prospective and randomized studies have demonstrated clinical benefit for patients with MCL undergoing autoSCT in first remission. Of particular importance is the seminal phase 3 study of the European MCL Network, which established the role of autoSCT in this setting.61 In this prospective randomized trial involving 122 newly diagnosed MCL patients who responded to CHOP-like induction, patients in CR derived a greater benefit from autoSCT.

More recent studies have demonstrated similar benefits using cytarabine-based autoSCT. The Nordic MCL2 study evaluated 160 patients using R-CHOP, alternating with rituximab and high-dose cytarabine, followed by autoSCT. This study used “maxi-CHOP,” an augmented CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide 1200 mg/m2, doxorubicin 75 mg/m2, but standard doses of vincristine [2 mg] and prednisone [100 mg days 1–5]), alternating with 4 infusions of cytarabine at 2 g/m2 and standard doses of rituximab (375 mg/m2). Patients then received conditioning with BEAM and autoSCT. Patients were evaluated for the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD) and for the t(11;14) or clonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement with polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Patients with MRD were offered therapy with rituximab at 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 doses. This combination resulted in 10-year OS rates of 58%.36 In a multicenter study involving 78 patients from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB), R-CHOP followed by high-dose cytarabine and BEAM-based autoSCT resulted in a 5-year OS of 64%.37 A single-arm phase 2 study from the Netherlands also tested R-CHOP followed by high-dose cytarabine and BEAM-based autoSCT. Nonhematologic toxicities were 22% after high-dose cytarabine, and 55% after BEAM. The ORR was 70%, with a 64% CR rate and 66% OS at 4 years.38 The French GELA group used 3 cycles of R-CHOP and 3 cycles of R-DHAP in a phase 2 study of young (under age 66) MCL patients. Following R-CHOP, the ORR was 93%, and following R-DHAP the ORR was 95%. Five-year OSA was 75%.39 A large randomized phase 3 study by Hermine and colleagues of the EMCLN confirmed the benefit of this approach in 497 patients with newly diagnosed MCL. R-CHOP for 6 cycles followed by autoSCT was compared to R-CHOP for 3 cycles alternating with R-DHAP for 3 cycles and autoSCT with a cytarabine-based conditioning regimen. The addition of cytarabine significantly increased rates of CR, TTF, and OS, without increasing toxicity.40

CASE CONTINUED

The patient is treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy for 3 cycles followed by R-DHAP. His course is complicated by mild tinnitus and acute kidney injury from cisplatin that promptly resolves. Three weeks following treatment, a restaging PET/CT scan shows resolution of all lymphadenopathy, with no hypermetabolic uptake, consistent with a complete remission. A repeat bone marrow biopsy shows no involvement with MCL. He subsequently undergoes an autoSCT, and restaging CT/PET 3 months following autoSCT shows continued remission. He is monitored every 3 to 6 months over the next several years.

He has a 4.5-year disease remission, after which he develops growing palpable lymphadenopathy on exam and progressive anemia and thrombocytopenia. A bone marrow biopsy is repeated, which shows recurrent MCL. Restaging diagnostic imaging with a CT scan reveals lymphadenopathy above and below the diaphragm. An axillary lymph node biopsy also demonstrates recurrent MCL. At this time the patient is otherwise in fairly good health, except for feeling fatigued. His ECOG performance status is 1. He begins therapy with bortezomib at a dose of 1.3 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 for 6 cycles. His treatment course is complicated by painful sensory peripheral neuropathy of the bilateral lower extremities. Restaging studies at the completion of therapy demonstrate that he has achieved a partial response, with a 50% reduction in the size of involved lymphadenopathy and some residual areas of hypermetabolic uptake. His peripheral cytopenias improve moderately.

• What are the therapeutic options for relapsed MCL?

TREATMENT OF RELAPSED MCL

Single-Agent and Combination Chemotherapy

Whenever possible, and since there is no standard, patients with relapsed MCL should be offered a clinical trial. Outside of a clinical study, many of the treatment regimens used at diagnosis can also be applied in the relapsed setting. In relapsed MCL, Rummel et al showed that BR for 4 cycles resulted in an ORR of 90%, with a CR of 60%. The median PFS was 24 months.41 Bortezomib, an inhibitor of the proteasome-ubiquitin pathway, leads to apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in MCL.42 Multiple studies have evaluated bortezomib both as a single agent and in combination for patients with relapsed MCL. In 2006, bortezomib became the first agent approved by the FDA in relapsed or refractory MCL, based on the phase 2 PINNACLE study. This prospective multicenter study involving 155 patients demonstrated an ORR of 33%, CR rate of 8%, and median treatment duration of 9 months. The median time to progression was 6 months.43 Subsequently, bortezomib-containing combinations evolved. In a multicenter study of relapsed and refractory indolent NHL and MCL, Friedberg and colleagues evaluated bortezomib in combination with BR.44 In the MCL cohort, the ORR was 71%. These promising results led to the study of this combination in the frontline setting. The ongoing ECOG 1411 study is using BR for the frontline treatment of MCL with or without bortezomib as induction. This study also includes rituximab maintenance, and randomizes patients to undergo maintenance with or without the immunomodulator lenalidomide. Bortezomib has been associated with herpes simplex and herpes zoster reactivation. Neuropathy has also been observed with bortezomib, which can be attenuated by administering it subcutaneously.

Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent derived from thalidomide. It has significant activity and is a mainstay of treatment in multiple myeloma. Lenalidomide acts by enhancing cellular immunity, has antiproliferative effects, and inhibits T-cell function leading to growth inhibitory effects in the tumor microenvironment.45 In MCL, lenalidomide has demonstrated clinical activity both as a single agent and in combination, as well as in preclinical studies establishing its pro-apoptotic effects.46 The pivotal EMERGE study evaluated monotherapy with lenalidomide in heavily pretreated relapsed and refractory MCL. This multicenter international study of 134 patents reported an ORR of 28% with a 7.5% CR rate and median PFS of 4 months. All patients had relapsed or progressed following bortezomib. This led to the approval of lenalidomide by the FDA in 2013 for the treatment of patients with MCL whose disease relapsed or progressed following 2 prior therapies, one of which included bortezomib.47 Lenalidomide has been associated with neutropenia, secondary cancers, and deep venous thrombosis.

In combination with other agents in the relapsed setting, lenalidomide shows broader activity. A phase 1/2 study by Wang and colleagues demonstrated an ORR of 57%; the median response duration was 19 months when lenalidomide was combined with rituximab for relapsed/refractory MCL.48

Novel Therapies

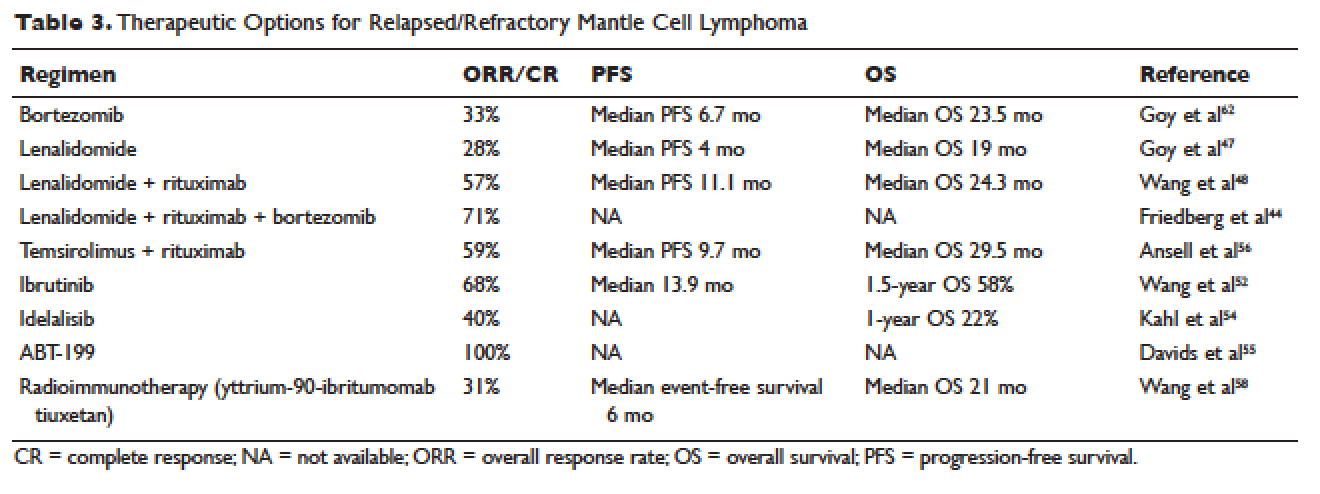

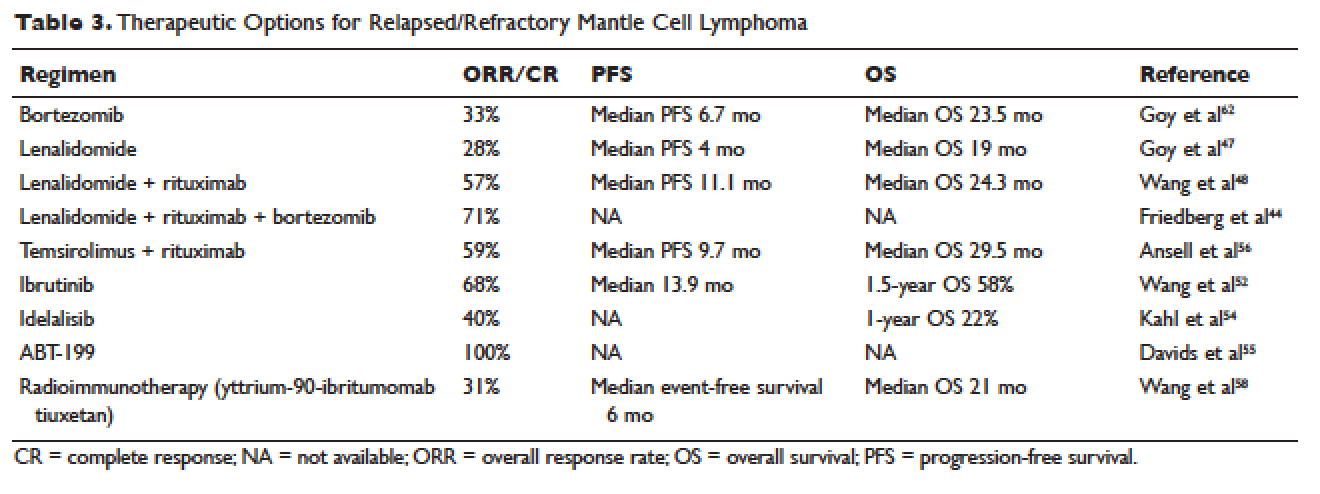

More recently, novel treatment approaches have been tested in MCL based on an increased understanding of aberrant signaling pathways in this disease (Table 3). Constitutive activation of B-cell receptor signaling is critical for the survival and proliferation of lymphomas, and has led to the development of targeted agents inhibiting B-cell receptor–associated protein kinases. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is one essential component of the B-cell receptor.49 In particular, proteins upstream of the BTK pathway have been implicated in growth and proliferation of MCL, suggesting that inhibition of BTK may impede lymphomagenesis.50 Ibrutinib is an oral inhibitor of BTK, and demonstrates activity in multiple lymphoma subtypes. In a phase 1 study of ibrutinib in relapsed and refractory hematologic malignancies, an ORR of 60% was observed in 50 evaluable patients, with 16% CR. Median PFS was 13 months. Among these, 7 of 9 patients with MCL responded, including 3 CRs.51 Given these promising results, a phase 2 multicenter study evaluating ibrutinib in relapsed and refractory MCL was completed.52 At a dose of 560 mg daily, the response rate was 68%, with CR of 21%. The most common observed treatment-related side effects included diarrhea, fatigue, and nausea. Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were also observed. Of importance, 5% of patients had grade 3 or higher bleeding events, including subdural hematoma, gastrointestinal bleeding, and hematuria. The estimated OS rate was 58% at 18 months. On the basis of this study, the FDA approved ibrutinib for relapsed and refractory MCL in November 2013.

The PI3K pathway is another survival pathway that is dysfunctional in several hematologic disorders, including MCL. Overexpression of PI3K and its downstream targets contributes to MCL pathogenesis.53 Idelalisib is an oral small molecule inhibitor of the delta isoform of PI3K that is dosed daily; it was approved by the FDA for the treatment of relapsed and refractory follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. It is being further evaluated in MCL. A dose-escalation phase 1 study in heavily pre-treated MCL patients established safety and tolerability.54 Efficacy analysis showed an ORR of 40%, CR of 5%, and 1-year OS of 22%. Further phase 2 studies testing idelalisib as a single agent and in combination for MCL are ongoing. Side effects of idelalisib include elevated liver enzymes, pneumonitis, and diarrhea.

The BCL family of proteins is involved in both pro-and anti-apoptotic functions. BCL2 is an intracellular protein that blocks apoptosis. ABT-199 is an oral BCL2 inhibitor that in early clinical trials has shown very promising activity in MCL. In a phase 1 study of 31 relapsed and refractory NHL patients, all 8 MCL patients (100% ORR) responded to ABT-199 therapy.55 Given these promising initial results, multiple studies evaluating ABT-199 are ongoing in MCL as part of first-line treatment as well as for relapsed disease. ABT-199 has been implicated in tumor lysis syndrome, and in early studies of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, fatal tumor lysis was observed.

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor temsirolimus has been evaluated in relapsed MCL. It is given weekly at 250 mg intravenously. Response rates to single-agent temsirolimus are approximately 20% to 35%, and are higher when combined with rituximab.56,57 The phase 2 study evaluating temsirolimus as a single agent enrolled 35 heavily pre-treated patients. ORR was 38% with only 1 CR. The duration of response was 7 months. Temsirolimus is approved for relapsed MCL in Europe but not in the United States. Similar to the other targeted agents, temsirolimus is actively being studied in combination with other active agents in MCL. Adverse effects noted with temsirolimus include diarrhea, stomatitis, and rash. Thrombocytopenia requiring dose reductions is another frequently observed complication.

Radioimmunotherapy

Radioimmunotherapy (RIT) has been studied extensively in MCL. RIT consists of anti-CD 20 antibodies coupled to radioactive particles that deliver radiation to targeted cells, minimizing toxicity to surrounding tissues. RIT is not used as frequently in the modern era as it had been in the past. At this time, only yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan is available.

RIT has been evaluated in MCL both at the time of relapse58 and more recently, as part of a conditioning regimen prior to autoSCT, with good tolerability.65–67 Averse events noted with RIT include hematologic toxicity (can be prolonged), hypothyroidism, and in rare cases, myelodysplastic syndrome and acute leukemia. The bone marrow must have less than 25% involvement with disease prior to administration. Wang and colleagues evaluated yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan in 34 heavily pretreated patients with MCL.58 They observed an ORR of 31%. The median event-free survival (EFS) was 6 months, but in patients achieving either CR or PR, EFS was 28 months. A 21-month OS was noted.

In the upfront setting, RIT has been added as a mechanism of intensification. A recent Nordic group study of RIT with autoSCT did not find benefit with the addition of RIT.59 An ECOG study recently added yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan after CHOP chemotherapy in the upfront treatment of MCL, with good tolerability.55 However, when added to R-hyper-CVAD, the combination had unexpected high rates of hematologic toxicity, including grade 3/4 cytopenias and an unacceptably high rate of secondary malignancies.68

AutoSCT or Allogeneic Transplant

While many studies noted above have established the beneficial role of autoSCT in MCL in first remission, the role of allogeneic transplant (alloSCT) in MCL remains controversial. A recent large retrospective study conducted by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) evaluated 519 patients with MCL who underwent both autoSCT and alloSCT.60 Patients were grouped into an early cohort (transplant in first PR or CR, and 2 or fewer treatments) and late cohort (all other patients). The analysis had mature follow up. A multivariate analysis demonstrated that early autoSCT was associated with superior outcomes compared to autoSCT performed later. While it was not possible to demonstrate a survival benefit favoring autoSCT over reduced intensity (RIC) alloSCT, patients transplanted later in their disease course had shorter OS. For patients receiving autoSCT in CR 1 following only 1 prior line of therapy, OS at 5 years was 75% and PFS was 70%. Patients undergoing RIC followed by alloSCT had fewer relapses, but this was negated by higher nonrelapse mortality (25%), resulting in a PFS similar to autoSCT.

CASE CONCLUSION

After treatment with bortezomib the patient is well for 9 months. Subsequently, however, he develops increasing lymphadenopathy and progressive fatigue. He is then started on lenalidomide 25 mg orally daily for 21 out of 28 days. He experiences significant fatigue with lenalidomide and prolonged neutropenia requiring dose delays, despite dose modification to 10 mg orally daily. He requires discontinuation of lenalidomide. Given persistent disease, the patient then begins treatment with ibrutinib. Within a few days of starting ibrutinib therapy, he experiences a marked but transient leukocytosis. Two months later, the patient’s palpable lymphadenopathy has decreased, and his anemia and thrombocytopenia related to MCL are improving. He has tolerated treatment well. His course has been complicated only by a mild, pruritic maculopapular eruption on his chest, back, and arms, that was responsive to topical low-dose steroids. He remains on ibrutinib 1 year later.

CONCLUSION

Advances in our understanding of MCL treatment are revolutionizing the approach to this once deadly disease. Over the next several years, these gains will weave themselves into the current treatment paradigm and likely alter the treatment landscape for MCL as we know it.

- Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. New approach to classifying non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: clinical features of the major histologic subtypes. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2780–95.

- Zhou Y, Wang H, Fang W, et al. Incidence trends of mantle cell lymphoma in the United States between 1992 and 2004. Cancer 2008;113:791–8.

- Geisler CH. Front-line treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2010;95:1241–3.

- Fernandez V, Salamero O, Espinet B, et al. Genomic and gene expression profiling defines indolent forms of mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Res 2010;70:1408–18.

- Martin P, Chadburn A, Christos P, et al. Outcome of deferred initial therapy in mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1209–13.

- Bertoni F, Ponzoni M. The cellular origin of mantle cell lymphoma. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007;39:1747–53.

- de Boer CJ, van Krieken JH, Kluin-Nelemans HC, et al. Cyclin D1 messenger RNA overexpression as a marker for mantle cell lymphoma. Oncogene 1995;10:1833–40.

- Jares P, Colomer D, Campo E. Molecular pathogenesis of mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Invest 2012;122:3416–23.

- Rosenwald A, Wright G, Wiestner A, et al. The proliferation gene expression signature is a quantitative integrator of oncogenic events that predicts survival in mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell 2003;3:185–97.

- Determann O, Hoster E, Ott G, et al. Ki-67 predicts outcome in advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma patients treated with anti-CD20 immunochemotherapy: results from randomized trials of the European MCL Network and the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2008;111:2385–7.

- Vegliante MC, Palomero J, Perez-Galan P, et al. SOX11 regulates PAX5 expression and blocks terminal B-cell differentiation in aggressive mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2013;121:2175–85.

- Bea S, Valdes-Mas R, Navarro A, et al. Landscape of somatic mutations and clonal evolution in mantle cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:18250–5.

- Zelenetz AD, Abramson JS, Advani RH, et al. Non- Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2011;9: 484–560.

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3059–68.

- Zelenetz AD, Abramson JS, Advani RH, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8:288–334.

- Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2008;111:558–65.

- Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. The Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) is superior to the International Prognostic Index (IPI) in predicting survival following intensive first-line immunochemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). Blood 2010;115:1530–3.

- Tiemann M, Schrader C, Klapper W, et al. Histopathology, cell proliferation indices and clinical outcome in 304 patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL): a clinicopathological study from the European MCL Network. Br J Haematol 2005;131:29–38.

- Raty R, Franssila K, Joensuu H, et al. Ki-67 expression level, histological subtype, and the International Prognostic Index as outcome predictors in mantle cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol 2002;69:11–20.

- Vogt N, Klapper W. Variability in morphology and cell proliferation in sequential biopsies of mantle cell lymphoma at diagnosis and relapse: clinical correlation and insights into disease progression. Histopathology 2013;62:334–42.

- Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo-purged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood 2008;112:2687–93.

- Howard OM, Gribben JG, Neuberg DS, et al. Rituximab and CHOP induction therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma: molecular complete responses are not predictive of progression-free survival. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1288–94.

- Griffiths R, Mikhael J, Gleeson M, et al. Addition of rituximab to chemotherapy alone as first-line therapy improves overall survival in elderly patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2011;118:4808–16.

- Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). J Clin Oncol 2005;23:1984–92.

- Romaguera JE, Fayad L, Rodriguez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7013–23.

- Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, et al. Treatment of older patients with mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2012;367:520–31.

- Robak T, Huang H, Jin J, et al. Bortezomib-based therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2015;372:944–53.

- Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS, et al. Randomized trial of bendamustine-rituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood 2014;123:2944–52.

- Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2013;381:1203–10.

- Houot R, Le Gouill S, Ojeda Uribe M, et al. Combination of rituximab, bortezomib, doxorubicin, dexamethasone and chlorambucil (RiPAD+C) as first-line therapy for elderly mantle cell lymphoma patients: results of a phase II trial from the GOELAMS. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1555–61.

- Ruan J, Martin P, Furman RR, et al. Bortezomib plus CHOP-rituximab for previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:690–7.

- Chang JE, Li H, Smith MR, et al. Phase 2 study of VcR-CVAD with maintenance rituximab for untreated mantle cell lymphoma: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study (E1405). Blood 2014; 123:1665–73.

- Romaguera JE, Fayad LE, Feng L, et al. Ten-year follow-up after intense chemoimmunotherapy with Rituximab-HyperCVAD alternating with Rituximab-high dose methotrexate/cytarabine (R-MA) and without stem cell transplantation in patients with untreated aggressive mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2010;150:200–8.

- Bernstein SH, Epner E, Unger JM, et al. A phase II multicenter trial of hyperCVAD MTX/Ara-C and rituximab in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma; SWOG 0213. Ann Oncol 2013;24:1587–93.

- LaCasce AS, Vandergrift JL, Rodriguez MA, et al. Comparative outcome of initial therapy for younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: an analysis from the NCCN NHL Database. Blood 2012;119:2093–9.

- Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Nordic MCL2 trial update: six-year follow-up after intensive immunochemotherapy for untreated mantle cell lymphoma followed by BEAM or BEAC + autologous stem-cell support: still very long survival but late relapses do occur. Br J Haematol 2012;158:355–62.

- Damon LE, Johnson JL, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for untreated patients with mantle-cell lymphoma: CALGB 59909. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6101–8.

- van ‘t Veer MB, de Jong D, MacKenzie M, et al. High-dose Ara-C and beam with autograft rescue in R-CHOP responsive mantle cell lymphoma patients. Br J Haematol 2009;144:524–30.

- Delarue R, Haioun C, Ribrag V, et al. CHOP and DHAP plus rituximab followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: a phase 2 study from the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood 2013;121:48–53.

- Hermine O, Hoster E, Walewski J, et al. Alternating courses of 3x CHOP and 3x DHAP plus rituximab followed by a high dose ARA-C containing myeloablative regimen and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) increases overall survival when compared to 6 courses of CHOP plus rituximab followed by myeloablative radiochemotherapy and ASCT in mantle cell lymphoma: final analysis of the MCL Younger Trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network (MCL net). In: American Society of Hematology Proceedings. December 8–11, 2012; Atlanta, GA. Abstract 151.

- Rummel MJ, Al-Batran SE, Kim SZ, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab is effective and has a favorable toxicity profile in the treatment of mantle cell and low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3383–9.

- Pham LV, Tamayo AT, Yoshimura LC, et al. Inhibition of constitutive NF-kappa B activation in mantle cell lymphoma B cells leads to induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. J Immunol 2003;171:88–95.

- Fisher RI, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4867–74.

- Friedberg JW, Vose JM, Kelly JL, et al. The combination of bendamustine, bortezomib, and rituximab for patients with relapsed/refractory indolent and mantle cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2011;117:2807–12.

- Bartlett JB, Dredge K, Dalgleish AG. The evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:314–22.

- Qian Z, Zhang L, Cai Z, et al. Lenalidomide synergizes with dexamethasone to induce growth arrest and apoptosis of mantle cell lymphoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Leuk Res 2011;35:380–6.

- Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) study. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3688–95.

- Wang M, Fayad L, Wagner-Bartak N, et al. Lenalidomide in combination with rituximab for patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:716–23.

- Buggy JJ, Elias L. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and its role in B-cell malignancy. Int Rev Immunol 2012;31: 119–32.

- Rinaldi A, Kwee I, Taborelli M, et al. Genomic and expression profiling identifies the B-cell associated tyrosine kinase Syk as a possible therapeutic target in mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2006;132:303–16.

- Advani RH, Buggy JJ, Sharman JP, et al. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (PCI-32765) has significant activity in patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31:88–94.

- Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:507–16.

- Rudelius M, Pittaluga S, Nishizuka S, et al. Constitutive activation of Akt contributes to the pathogenesis and survival of mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2006;108: 1668–76.

- Kahl BS, Spurgeon SE, Furman RR, et al. A phase 1 study of the PI3Kdelta inhibitor idelalisib in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Blood 2014;123:3398–405.

- Davids MS, Seymour JF, Gerecitano JF, et al. Updated results of a phase I first in human study of the BCL-2inhibitor ABT-199 in patients with relapsed/refractory NHL. J Clin Oncol 31, 2013 (suppl; abstr 8520).

- Ansell SM, Tang H, Kurtin PJ, et al. Temsirolimus and rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: a phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:361–8.

- Witzig TE, Geyer SM, Ghobrial I, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent temsirolimus (CCI-779) for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5347–56.

- Wang M, Oki Y, Pro B, et al. Phase II study of yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5213–8.

- Kolstad A, Laurell A, Jerkeman M, et al. Nordic MCL3 study: 90Y-ibritumomab-tiuxetan added to BEAM/C in non-CR patients before transplant in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2014;123:2953–9.

- Fenske TS, Zhang MJ, Carreras J, et al. Autologous or reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chemotherapy-sensitive mantle-cell lymphoma: analysis of transplantation timing and modality. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:273–81.

- Dreyling M, Lenz G, Hoster E, et al. Early consolidation by myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission significantly prolongs progression-free survival in mantle-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the European MCL Network. Blood 2005;105:2677–84.

- Goy A, Younes A, McLaughlin P, et al. Phase II study of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:667–75.

- Visco C, Finotto S, Zambello R, et al. Combination of rituximab, bendamustine, and cytarabine for patients with mantle-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma ineligible for intensive regimens or autologous transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2013;10;31:1442–9.

- Gressin R, Callanan M, Daguindau N, et al. The Ribvd regimen (Rituximab IV, Bendamustine IV, Velcade SC, Dexamethasone IV) offers a high complete response rate In elderly patients with untreated mantle cell lymphoma. Preliminary results of the Lysa trial “Lymphome Du Manteau 2010 SA.” Blood 2013;122:370.

- Krishnan A, Nademanee A, Fung HC, et al. Phase II trial of a transplantation regimen of yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan and high-dose chemotherapy in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:90–5.

- Nademanee A, Forman S, Molina A, et al. A phase 1/2 trial of high-dose yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan in combination with high-dose etoposide and cyclophosphamide followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with poor-risk or relapsed non-Hodgkinlymphoma. Blood 2005;106:2896–902.

- Shimoni A, Avivi I, Rowe JM, et al. A randomized study comparing yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) and high-dose BEAM chemotherapy versus BEAM alone as the conditioning regimen before autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with aggressive lymphoma. Cancer 2012;118:4706–14.

- Arranz R, García-Noblejas A, Grande C, et al. First-line treatment with rituximab-hyperCVAD alternating with rituximab-methotrexate-cytarabine and followed by consolidation with 90Y-ibritumomab-tiuxetan in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Results of a multicenter, phase 2 pilot trial from the GELTAMO group. Haematologica 2013;98:1563-70.

INTRODUCTION

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon, distinct clinical subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that comprises approximately 8% of all lymphoma diagnoses in the United States and Europe.1,2 Considered incurable, MCL often presents in advanced stages, particularly with involvement of the lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract in the form of lymphomatous polyps. MCL disproportionately affects males, and incidence rises with age, with a median age at diagnosis of 68 years.2 Historically, the prognosis of patients with MCL has been among the poorest among B-cell lymphoma patients, with a median overall survival (OS) of 3 to 5 years, and time to treatment failure (TTF) of 18 to 24 months, although this is improving in the modern era.3 Less frequently, patients with MCL display isolated bone marrow, peripheral blood, and splenic involvement. These cases tend to behave more indolently with longer survival.4,5 Recent advances in therapy have dramatically impacted treatment alternatives and outcomes for MCL. As such, the therapeutic and prognostic landscape of MCL is evolving rapidly.

PATHOGENESIS

The histologic diagnosis of MCL by morphology alone is often challenging. Accurate diagnosis relies on immunohistochemical staining for the purposes of immunophenotyping.6 MCL typically expresses B-cell markers CD5 and CD20, and lacks both CD10 and CD23. The genetic hallmark of MCL is the t(11;14) (q13;q32) chromosomal translocation leading to upregulation of the cyclin D1 protein, a critical regulator of the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Specifically, the t(11;14) translocation, present in virtually all cases of MCL, juxtaposes the proto-oncogene CCND1 to the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene.7 Consequently, cyclin D1, normally not expressed in B lymphocytes, becomes constitutively overexpressed. This alteration is thought to facilitate the deregulation of the cell cycle at the G1-S phase transition.8

Gene expression profiling studies have underscored the importance of cell cycle deregulation in MCL, and high proliferation is associated with a worse prognosis.9 More than 50% of the genes associated with poor outcomes were derived from the “proliferation signature” that was more highly expressed in dividing cells. In the seminal Rosenwald study, a gene expression–based outcome model was constructed in which the proliferation signature average represents a linear variable that assigns a discrete probability of survival to an individual patient.9 The proliferative index, or proliferative signature, of MCL can be estimated by the percentage of Ki-67–positive cells present in the tumor through immunohistochemistry. This is often used as a marker of poor outcomes, and as a surrogate for the proliferative signature in MCL that can be incorporated into clinical practice (as opposed to gene expression profiling). Statistically significant differences in OS have emerged between groups of MCL patients with Ki-67–positive cells comprising less than 30% of their tumor sample (favorable) and those with Ki-67–positive cells comprising 30% or greater (unfavorable).10

Recent data has also identified the importance of the transcription factor SOX 11 (SRY-related HMG-box), which regulates multiple cellular transcriptional events, including cell proliferation and differentiation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis.11 MCL expressing SOX 11 behaves more aggressively than MCL variants lacking SOX 11 expression, and tends to accumulate more genetic alterations.12 Moreover, lack of SOX 11 expression characterizes a subset of MCL that does not carry the t(11;14) translocation.

DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING

CASE PRESENTATION

A 62-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with cervical lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and early satiety over the past several months. He is otherwise in good health. His Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status is 1. On physical examination, 3-cm lymphadenopathy in the bilateral cervical chain is noted. Bilateral axillary lymph nodes measure 2 to 4 cm. His spleen is enlarged and is palpable at approximately 5 cm below the costal margin. A complete blood count reveals a total white blood cell (WBC) count of 14,000 cells/μL, with 68% lymphocytes and a normal distribution of neutrophils. Hemoglobin is 11 g/dL, and platelet count is 112,000/μL. The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level is 322 U/L (upper limit of normal: 225 U/L).

• How is MCL diagnosed?

Diagnosis of MCL requires review by expert hematopathologists.13 Whenever possible, an excisional biopsy should be performed for the adequate characterization of lymph node architecture and evaluation by immunohistochemistry. Aside from the characteristic expression of CD5 and CD20 and absence of CD23, MCL should express cyclin D1, which reflects t(11;14). If cyclin D1 is inconclusive or unavailable, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) for t(11;14) should be performed.8 Patients often have circulating malignant lymphocytes, or leukemic phase MCL. Flow cytometry of the peripheral blood can detect traditional surface markers, and FISH can also be performed on circulating abnormal lymphocytes.

For disease staging, bone marrow biopsy and aspiration are required. Radiographic staging using computed tomography (CT) scans and/or positron emission tomography (PET) scans had traditionally followed the Ann Arbor staging system, but recently the Lugano classification has emerged, which delineates only early or advanced stage.14 Gastrointestinal evaluation of MCL with endoscopy and colonoscopy with blind biopsies has been recommended to evaluate for the presence of lymphomatous polyps, but this is not an absolute requirement.15

RISK STRATIFICATION

At diagnosis, patients should undergo risk stratification in order to understand prognosis and possibly guide treatment. In MCL, the MCL international prognostic index (MIPI) is used. The MIPI is a prognostic tool developed exclusively for patients with MCL using data from 455 patients with advanced-stage MCL treated within 3 European clinical trials.16 The MIPI classified patients into risk groups based on age, ECOG performance status, LDH level, and WBC count. Patients were categorized into low-risk (44% of patients, median OS not reached), intermediate-risk (35%, median OS 51 months), and high-risk groups (21%, median OS 29 months). This is done through a logarithmic calculation, which can be accessed through online calculators (a prototype example can be found at www.qxmd.com/calculate-online/hematology/prognosis-mantle-cell-lymphoma-mipi). Cell proliferation using the Ki-67 index was evaluated in an exploratory analysis (the biologic [“B”] MIPI), and also demonstrated strong prognostic relevance.16 Currently, treatment of MCL patients is not stratified by MIPI outside of a clinical trial, but this useful tool assists in assessing patient prognosis and has been validated for use with both conventional chemoimmunotherapy and in the setting of autologous stem cell transplant (autoSCT).16,17 At this point in time, the MIPI score is not used to stratify treatment, although some clinical trials are incorporating the use of the MIPI score at diagnosis. Nonetheless, given its prognostic importance, the MIPI should be performed for all MCL patients undergoing staging and evaluation for treatment to establish disease risk.

As noted, the proliferative signature, represented by the Ki-67 protein, is also highly prognostic in MCL. Ki-67 is expressed in the late G1, S, G2, and M phases of the cell cycle. The Ki-67 index is defined by the hematopathologist as the percentage of lymphoma cells staining positive for Ki-67 protein, based on the number of cells per high-power field. There is significant interobserver variability in this process, which can be minimized by assessing Ki-67 quantitatively using computer software. The prognostic significance of Ki-67 at diagnosis was established in large studies of MCL patient cohorts, with survival differing by up to 3 years.18,19 Determann et al demonstrated the utility of the proliferative index in patients with MCL treated with standard chemoimmunotherapy.10 In this study, 249 patients with advanced-stage MCL treated within randomized trials conducted by the European MCL Network were analyzed. The Ki-67 index was found to be extremely prognostic of OS, independent of other clinical risk factors, including the MIPI score. As a continuous variable, Ki-67 indices of greater than 10% correlated with poor outcomes. The Ki-67 index has also been confirmed as prognostic in relapsed MCL.20 It is important to note that, as a unique feature, the Ki-67 index has remained an independent prognostic factor, even when incorporated into the “B” MIPI.

TREATMENT

CASE CONTINUED

The patient undergoes an excisional biopsy of a cervical lymph node, which demonstrates an abnormal proliferation of small-medium–sized lymphocytes with slightly irregular nuclear contours. Immunohistochemistry shows that the abnormal lymphocytes are positive for CD20 and CD5, negative for CD10 and CD23, and diffusely positive for cyclin D1, consistent with a diagnosis of MCL. The proliferative index, as measured by the Ki-67 immunostain, is 40%. A bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are then obtained, which show a clonal population of B lymphocytes expressing the same immunophenotype as the lymph node (positive for CD20 and CD5, negative for CD10 and CD23, cyclin D1 positive). A CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast is obtained, along with a PET scan. These studies identify extensive hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy in the bilateral cervical chains, supraclavicular areas, mediastinum, and hilum. Mesenteric lymph nodes are also enlarged and hypermetabolic, as are retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The spleen is noted to be enlarged with multiple hypermetabolic lesions. Based on the presence of extensive lymphadenopathy as well as bone marrow involvement, the patient is diagnosed with stage IV MCL. He undergoes risk-stratification with the MIPI. His MIPI score is 6.3, high risk.

• What is the approach to upfront therapy for MCL?

FRONTLINE THERAPY

Role of Watchful Waiting

A small proportion of MCL patients have indolent disease that can be observed. This population is more likely to have leukemic-phase MCL with circulating lymphocytes, splenomegaly, and bone marrow involvement and absent or minimal lymphadenopathy.4,5 A retrospective study of 97 patients established that deferment of initial therapy in MCL is acceptable in some patients.5 In this study, approximately one third of patients with MCL were observed for more than 3 months before initiating systemic therapy, and the median time to treatment for the observation group was 12 months. Most patients undergoing observation had a low-risk MIPI. Patients were not harmed by observation, as no OS differences were observed among groups. This study underscores that deferred treatment can be an acceptable alternative in selected MCL patients for a short period of time. In practice, the type of patient who would be appropriate for this approach is someone who is frail, elderly, and with multiple comorbidities. Additionally, expectant observation could be considered for patients with limited-stage or low-volume MCL, low Ki-67 index, and low-risk MIPI scores.

Approach to Therapy

Treatment of MCL is generally approached by evaluating patient age and fitness for treatment. While there is no accepted standard, for younger patients healthy enough to tolerate aggressive approaches, treatment often involves an intensive cytarabine-containing regimen, which is consolidated with an autoSCT. This approach results in the longest remission duration, with some series suggesting a plateau in survival after 5 years, with no relapses.21 Nonintensive conventional chemotherapy alone is often reserved for the frailer or older patient. Given that remission durations with chemotherapy alone in MCL are short, goals of treatment focus on maximizing benefit and remission duration and minimizing risk of toxicity.

Standard Chemotherapy: Elderly and/or Frail Patients

Conventional chemotherapy alone for the treatment of MCL results in a 70% to 85% overall response rate (ORR) and 7% to 30% complete response (CR) rate.22 Rituximab, a mouse humanized monoclonal IgG1 anti-CD20 antibody, is used as standard of care in combination with chemotherapy, since its addition has been found to increase response rates and extend both progression-free survival (PFS) and OS compared to chemotherapy alone.23,24 However, chemoimmunotherapy approaches do not provide long-term control of MCL and are considered noncurative. Various regimens have been studied and include anthracycline-containing regimens such as R-CHOP (rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone),22 combination chemotherapy with antimetabolites such as R-hyper-CVAD (hyper-fractionated rituximab with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine),25 purine analogue–based regimens such as R-FC (rituximab with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide),26 bortezomib-containing regimens,27 and alkylator-based treatment with BR (bendamustine and rituximab) (Table 1).28,29 Among these, the most commonly used are R-CHOP and BR.

Two large randomized studies compared R-CHOP for 6 cycles to BR for 6 cycles in patients with indolent NHL and MCL. Among MCL patients, BR resulted in superior PFS compared to R-CHOP (69 months versus 26 months) but no benefit in OS.28,29 The ORR to R-CHOP was approximately 90%, with a PFS of 21 months in the Rummel et al study.29 This study included more than 80 centers in Germany and enrolled 549 patients with MCL, follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion. Among these, 46 patients received BR and 48 received R-CHOP (18% for both, respectively). It should be noted that patients in the BR group had significantly less toxicity and experienced fewer side effects than did those in the R-CHOP group. Similarly, BR-treated patients had a lower frequency of hematologic side effects and infections of any grade. However, drug-associated skin reactions and allergies were more common with BR compared to R-CHOP. The study by Flinn and colleagues was an international randomized, noninferiority phase 3 study designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of BR compared with R-CHOP or R-CVP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone) for treatment-naive patients with MCL or other indolent NHL. The primary endpoint was CR. In this study, BR was found to be noninferior to R-CHOP and R-CVP based on CR rate (31% versus 25%, respectively; P = 0.0225). Response rates in general were high: 97% for BR and 91% for R-CHOP/R-CVP (P = 0.0102). Here, BR-treated patients experienced more nausea, emesis, and drug-induced hypersensitivity compared to the R-CHOP and R-CVP groups.

Another approach studied in older patients is the use of R-CHOP with rituximab maintenance. In a large European study, 560 patients 60 years of age or older with advanced-stage MCL were randomly assigned to either R-FC (rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide) every 28 days for 6 cycles, or R-CHOP every 21 days for 8 cycles. Patients who had a response then underwent a second randomization, with one group receiving rituximab maintenance therapy. Maintenance was continued until progression of disease. Patients in this study were not eligible for high-dose chemotherapy and autoSCT. The study found that rates of CR were similar with both R-FC and R-CHOP (40% and 34%, respectively; P = 0.10). However, the R-FC arm underperformed in several arenas. Disease progression occurred more frequently with R-FC (14% versus 5% with R-CHOP), and OS was shorter (4-year OS, 47% versus 62%; P = 0.005, respectively). More patients also died in the R-FC group, and there was greater hematologic toxicity compared to R-CHOP. At 4 years, 58% of the patients receiving rituximab remained in remission. Among patients who responded to R-CHOP, rituximab maintenance led to a benefit in OS, reducing the risk of progression or death by 45%.26 At this time, studies are ongoing to establish the benefit of rituximab maintenance after BR.

Bendamustine in combination with other agents has also been studied in the frontline setting. Visco and colleagues evaluated the combination of bendamustine with rituximab and cytarabine (R-BAC) in older patients with MCL (age 65 or older).63 This phase 2, two-stage study enrolled 40 patients and had a dose-finding arm for cytarabine in combination with BR. It permitted relapsed/refractory patients, but 50% had newly diagnosed, previously untreated MCL. The regimen had an impressive ORR of 100%, with CR rates of 95% for previously untreated patients. PFS at 2 years was 95%. R-BAC was well tolerated, with the primary toxicity being reversible myelosuppression.

BR was combined with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and dexamethasone in a phase 2 study.64 This Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA) study evaluated 76 patients with newly diagnosed MCL older than age 65 years. BR was administered in standard doses (bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 and rituximab 375 mg/m² IV on day 1) and bortezomib was administered subcutaneously on days 1, 4, 8, and 11, with acyclovir for viral prophylaxis. Patients received 6 cycles. The ORR was 87% and the CR was 60%. Patients experienced toxicity, and not all bortezomib doses were administered due to neurotoxic or hematologic side effects.

A randomized phase 3 study compared R-CHOP to the VR-CAP regimen (R-CHOP regimen but bortezomib replaces vincristine on days 1, 4, 8, 11, at 1.3 mg/m2) in 487 newly diagnosed MCL patients.27 Median PFS was superior in the VR-CAP group compared with R-CHOP (14.4 months versus 24.7 months, respectively). Additionally, rates of CR were superior in the VR-CAP group (53% compared to 42% with R-CHOP). However, there was more hematologic toxicity with VR-CAP. On the basis of these findings, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved bortezomib for the frontline treatment of MCL.

Other chemoimmunotherapy combinations containing bortezomib have been studied in frontline MCL treatment, with promising results. These include bortezomib in combination with R-CHOP or modified R-hyper-CVAD, as well as bortezomib in combination with CHOP-like treatments and purine analogues.27,30–32 The ongoing ECOG 1411 study is currently evaluating bortezomib added to BR for induction therapy of newly diagnosed MCL in a 4-arm randomized trial. Patients receive BR with or without bortezomib during induction and are then randomly assigned to maintenance with either rituximab alone or rituximab with lenalidomide. Other novel combination agents are actively being studied in frontline MCL treatment, including lenalidomide and rituximab and BR with lenalidomide.

Intensification of Therapy and AutoSCT: Fitter and/or Younger Patients

Short response duration has created the need for post-remission therapy in MCL. One approach to improve remission duration in MCL is to intensify induction through the use of cytarabine-containing regimens and/or consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy, typically using BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) and autoSCT (Table 2). The cytarabine-containing R-hyper-CVAD regimen, developed at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, resulted in a 97% ORR and an 87% CR rate, with TTF of nearly 5 years. However, nearly one third of patients were unable to complete treatment due to toxicity, and 5 patients developed secondary myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia.33 The feasibility of this R-hyper-CVAD regimen was tested in a multicenter cooperative group setting, but similar results were not seen; in this study, nearly 40% of patients were unable to complete the full scheduled course of treatment due to toxicity.34

Other ways to intensify therapy in MCL involve adding a second non-cross-resistant cytarabine-containing regimen to R-CHOP after remission, such as DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin), followed by consolidation with an autoSCT. A retrospective registry from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network sought to compare the efficacy of different treatment approaches in the frontline setting. They studied 167 patients with MCL and compared 4 groups: treatment with R-hyper-CVAD, either with or without autoSCT, and treatment with R-CHOP, either with or without autoSCT. This study found that in patients younger than 65, R-CHOP followed by autoSCT or R-hyper-CVAD without autoSCT resulted in similar PF and OS, but was superior to R-CHOP alone for newly diagnosed MCL patients.35 These data support more intensive regimens in younger and fitter patients. Several other prospective and randomized studies have demonstrated clinical benefit for patients with MCL undergoing autoSCT in first remission. Of particular importance is the seminal phase 3 study of the European MCL Network, which established the role of autoSCT in this setting.61 In this prospective randomized trial involving 122 newly diagnosed MCL patients who responded to CHOP-like induction, patients in CR derived a greater benefit from autoSCT.

More recent studies have demonstrated similar benefits using cytarabine-based autoSCT. The Nordic MCL2 study evaluated 160 patients using R-CHOP, alternating with rituximab and high-dose cytarabine, followed by autoSCT. This study used “maxi-CHOP,” an augmented CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide 1200 mg/m2, doxorubicin 75 mg/m2, but standard doses of vincristine [2 mg] and prednisone [100 mg days 1–5]), alternating with 4 infusions of cytarabine at 2 g/m2 and standard doses of rituximab (375 mg/m2). Patients then received conditioning with BEAM and autoSCT. Patients were evaluated for the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD) and for the t(11;14) or clonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement with polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Patients with MRD were offered therapy with rituximab at 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 doses. This combination resulted in 10-year OS rates of 58%.36 In a multicenter study involving 78 patients from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB), R-CHOP followed by high-dose cytarabine and BEAM-based autoSCT resulted in a 5-year OS of 64%.37 A single-arm phase 2 study from the Netherlands also tested R-CHOP followed by high-dose cytarabine and BEAM-based autoSCT. Nonhematologic toxicities were 22% after high-dose cytarabine, and 55% after BEAM. The ORR was 70%, with a 64% CR rate and 66% OS at 4 years.38 The French GELA group used 3 cycles of R-CHOP and 3 cycles of R-DHAP in a phase 2 study of young (under age 66) MCL patients. Following R-CHOP, the ORR was 93%, and following R-DHAP the ORR was 95%. Five-year OSA was 75%.39 A large randomized phase 3 study by Hermine and colleagues of the EMCLN confirmed the benefit of this approach in 497 patients with newly diagnosed MCL. R-CHOP for 6 cycles followed by autoSCT was compared to R-CHOP for 3 cycles alternating with R-DHAP for 3 cycles and autoSCT with a cytarabine-based conditioning regimen. The addition of cytarabine significantly increased rates of CR, TTF, and OS, without increasing toxicity.40

CASE CONTINUED

The patient is treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy for 3 cycles followed by R-DHAP. His course is complicated by mild tinnitus and acute kidney injury from cisplatin that promptly resolves. Three weeks following treatment, a restaging PET/CT scan shows resolution of all lymphadenopathy, with no hypermetabolic uptake, consistent with a complete remission. A repeat bone marrow biopsy shows no involvement with MCL. He subsequently undergoes an autoSCT, and restaging CT/PET 3 months following autoSCT shows continued remission. He is monitored every 3 to 6 months over the next several years.

He has a 4.5-year disease remission, after which he develops growing palpable lymphadenopathy on exam and progressive anemia and thrombocytopenia. A bone marrow biopsy is repeated, which shows recurrent MCL. Restaging diagnostic imaging with a CT scan reveals lymphadenopathy above and below the diaphragm. An axillary lymph node biopsy also demonstrates recurrent MCL. At this time the patient is otherwise in fairly good health, except for feeling fatigued. His ECOG performance status is 1. He begins therapy with bortezomib at a dose of 1.3 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 for 6 cycles. His treatment course is complicated by painful sensory peripheral neuropathy of the bilateral lower extremities. Restaging studies at the completion of therapy demonstrate that he has achieved a partial response, with a 50% reduction in the size of involved lymphadenopathy and some residual areas of hypermetabolic uptake. His peripheral cytopenias improve moderately.

• What are the therapeutic options for relapsed MCL?

TREATMENT OF RELAPSED MCL

Single-Agent and Combination Chemotherapy

Whenever possible, and since there is no standard, patients with relapsed MCL should be offered a clinical trial. Outside of a clinical study, many of the treatment regimens used at diagnosis can also be applied in the relapsed setting. In relapsed MCL, Rummel et al showed that BR for 4 cycles resulted in an ORR of 90%, with a CR of 60%. The median PFS was 24 months.41 Bortezomib, an inhibitor of the proteasome-ubiquitin pathway, leads to apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in MCL.42 Multiple studies have evaluated bortezomib both as a single agent and in combination for patients with relapsed MCL. In 2006, bortezomib became the first agent approved by the FDA in relapsed or refractory MCL, based on the phase 2 PINNACLE study. This prospective multicenter study involving 155 patients demonstrated an ORR of 33%, CR rate of 8%, and median treatment duration of 9 months. The median time to progression was 6 months.43 Subsequently, bortezomib-containing combinations evolved. In a multicenter study of relapsed and refractory indolent NHL and MCL, Friedberg and colleagues evaluated bortezomib in combination with BR.44 In the MCL cohort, the ORR was 71%. These promising results led to the study of this combination in the frontline setting. The ongoing ECOG 1411 study is using BR for the frontline treatment of MCL with or without bortezomib as induction. This study also includes rituximab maintenance, and randomizes patients to undergo maintenance with or without the immunomodulator lenalidomide. Bortezomib has been associated with herpes simplex and herpes zoster reactivation. Neuropathy has also been observed with bortezomib, which can be attenuated by administering it subcutaneously.

Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent derived from thalidomide. It has significant activity and is a mainstay of treatment in multiple myeloma. Lenalidomide acts by enhancing cellular immunity, has antiproliferative effects, and inhibits T-cell function leading to growth inhibitory effects in the tumor microenvironment.45 In MCL, lenalidomide has demonstrated clinical activity both as a single agent and in combination, as well as in preclinical studies establishing its pro-apoptotic effects.46 The pivotal EMERGE study evaluated monotherapy with lenalidomide in heavily pretreated relapsed and refractory MCL. This multicenter international study of 134 patents reported an ORR of 28% with a 7.5% CR rate and median PFS of 4 months. All patients had relapsed or progressed following bortezomib. This led to the approval of lenalidomide by the FDA in 2013 for the treatment of patients with MCL whose disease relapsed or progressed following 2 prior therapies, one of which included bortezomib.47 Lenalidomide has been associated with neutropenia, secondary cancers, and deep venous thrombosis.

In combination with other agents in the relapsed setting, lenalidomide shows broader activity. A phase 1/2 study by Wang and colleagues demonstrated an ORR of 57%; the median response duration was 19 months when lenalidomide was combined with rituximab for relapsed/refractory MCL.48

Novel Therapies