User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

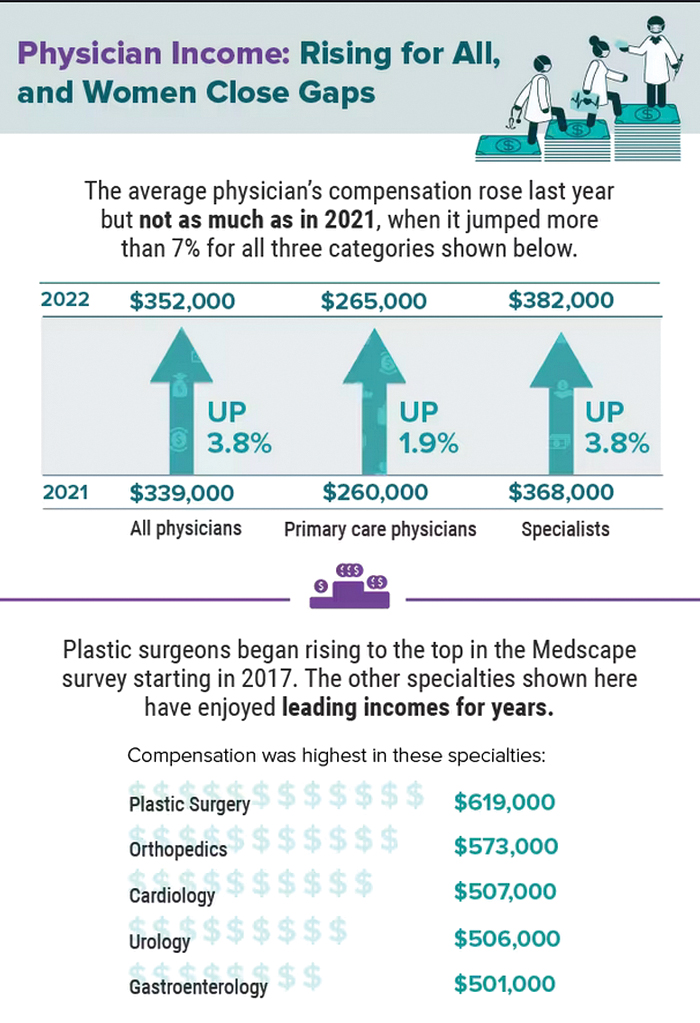

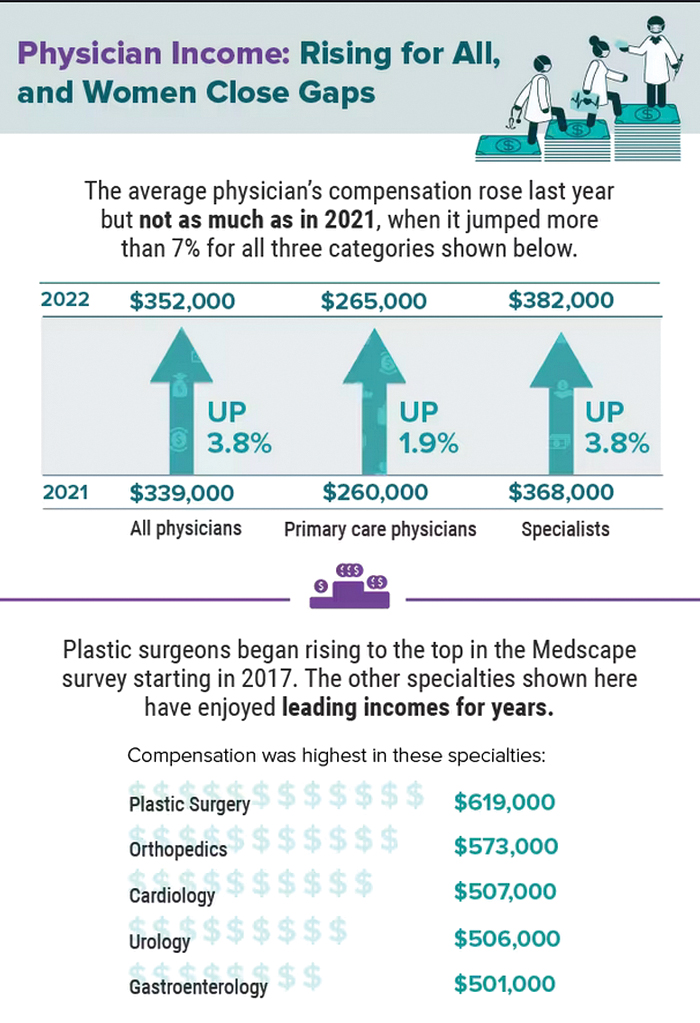

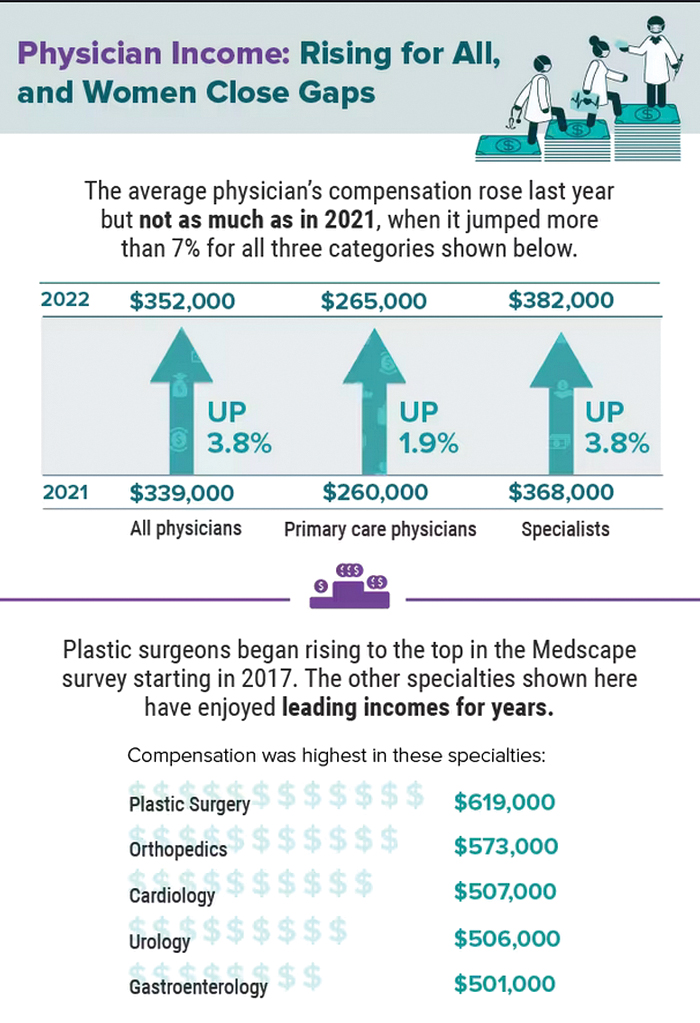

Infographic: Is your compensation rising as fast as your peers?

Did doctors’ salaries continue their zesty postpandemic rise in 2022? Are female physicians making pay gains versus their male counterparts that spark optimism for the future?

reveals which medical specialties pay better than others, and evaluates the current gender pay gap in medicine. If you’re interested in delving deeper into the data, check out Your Income vs. Your Peers’: Physician Compensation Report 2023.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Did doctors’ salaries continue their zesty postpandemic rise in 2022? Are female physicians making pay gains versus their male counterparts that spark optimism for the future?

reveals which medical specialties pay better than others, and evaluates the current gender pay gap in medicine. If you’re interested in delving deeper into the data, check out Your Income vs. Your Peers’: Physician Compensation Report 2023.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Did doctors’ salaries continue their zesty postpandemic rise in 2022? Are female physicians making pay gains versus their male counterparts that spark optimism for the future?

reveals which medical specialties pay better than others, and evaluates the current gender pay gap in medicine. If you’re interested in delving deeper into the data, check out Your Income vs. Your Peers’: Physician Compensation Report 2023.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A baby stops breathing at a grocery store – An ICU nurse steps in

My son needed a physical for his football team, and we couldn’t get an appointment. So, we went to the urgent care next to the H Mart in Cary, N.C. While I was waiting, I thought, let me go get a coffee or an iced tea at the H Mart. They have this French bakery in there.

I went in and ordered my drink, and I was waiting in line. I saw this woman pass me running with a baby. Another woman – I found out later it was her sister – was running after her, and she said: “Call 911!”

“I don’t have my phone,” I said. I left my phone with my son; he was using it.

I said: “Are you okay?” And she just handed me the baby. The baby was gray, and there was blood in her nose and mouth. The woman said: “She’s my baby. She’s 1 week old.”

I was trying to think very quickly. I didn’t see any bubbles in the blood around the baby’s nose or mouth to tell me if she was breathing. She was just limp. The mom was still screaming, but I couldn’t even hear her anymore. It was like I was having an out-of-body experience. All I could hear were my thoughts: “I need to put this baby down to start CPR. Someone was calling 911. I should go in the front of the store to save time, so EMS doesn’t have to look for me when they come.”

I started moving and trying to clean the blood from the baby’s face with her blanket. At the front of the store, I saw a display of rice bags. I put the baby on top of one of the bags. “Okay, where do I check for a pulse on a baby?” I took care of adults, never pediatric patients, never babies. She was so tiny. I put my hand on her chest and felt nothing. No heartbeat. She still wasn’t breathing.

People were around me, but I couldn’t see or hear anybody. All I was thinking was: “What can I do for this patient right now?” I started CPR with two fingers. Nothing was happening. It wasn’t that long, but it felt like forever for me. I couldn’t do mouth-to-mouth because there was so much blood on her face. I still don’t know what caused the bleeding.

It was COVID time, so I had my mask on. I was, like: “You know what? Screw this. She’s a 1-week-old baby. Her lungs are tiny. Maybe I don’t have to do mouth-to-mouth. I can just blow in her mouth.” I took off my mask and opened her mouth. I took a deep breath and blew a little bit of air in her mouth. I continued CPR for maybe 5 or 10 seconds.

And then she gasped! She opened her eyes, but they were rolled up. I was still doing CPR, and maybe 2 second after that, I could feel under my hand a very rapid heart rate. I took my hand away and lifted her up.

Just then the EMS got there. I gave them the baby and said: “I did CPR. I don’t know how long it lasted.” The EMS person looked at me, said: “Thank you for what you did. Now we need you to help us with mom.” I said, “okay.”

I turned around, and the mom was still screaming and crying. I asked one of the ladies that worked there, “Can you get me water?” She brought it, and I gave some to the mom, and she started talking to EMS.

People were asking me: “What happened? What happened?” It’s funny, I guess the nurse in me didn’t want to give out information. And I didn’t want to ask for information. I was thinking about privacy. I said, “I don’t know,” and walked away.

The mom’s sister came and hugged me and said thank you. I was still in this out-of-body zone, and I just wanted to get the hell out of there. So, I left. I went to my car and when I got in it, I started shaking and sweating and crying.

I had been so calm in the moment, not thinking about if the baby was going to survive or not. I didn’t know how long she was without oxygen, if she would have some anoxic brain injury or stroke. I’m a mom, too. I would have been just as terrified as that mom. I just hoped there was a chance that she could take her baby home.

I went back to the urgent care, and my son was, like, “are you okay?” I said: “You will not believe this. I just did CPR on a baby.” He said: “Oh. Okay.” I don’t think he even knew what that meant.

I’ve been an ICU nurse since 2008. I’ve been in very critical moments with patients, life or death situations. I help save people all the time at the hospital. Most of the time, you know what you’re getting. You can prepare. You have everything you need, and everyone knows what to do. You know what the worst will look like. You know the outcome.

But this was something else. You read about things like this. You hear about them. But you never think it’ll happen to you – until it happens.

I couldn’t stop thinking about the baby. So, 2 days later, I posted on Next Door to see if somebody would read it and say, “hey, the baby survived.” I was amazed at how many people responded, but no one knew the family.

The local news got hold of me and asked me to do a story. I told them, “the only way I can do a story is if the baby survived. I’m not going to do a story about a dead baby, and the mom has to live through it again.”

The reporter called me later on that day and said she had talked to the police. They said the family was visiting from out of state. The baby went to the hospital and was discharged home 2 days later. I said, “okay, then I can talk.”

When the news story came out, I started getting texts from people at work the same night. So many people were reaching out. Even people from out of state. But I never heard from the family. No one knew how to reach them.

Since I was very young, I wanted to work in a hospital, to help people. It really brings me joy, seeing somebody go home, knowing, yes, we did this. It’s a great feeling. I love this job. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

I just wish I had asked the mom’s name. Because I always think about that baby. I always wonder, what did she become? I hope somebody reads this who might know that little girl. It would be so nice to meet her one day.

Ms. Diallo is an ICU nurse and now works as nurse care coordinator at the University of North Carolina’s Children’s Neurology Clinic in Chapel Hill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

My son needed a physical for his football team, and we couldn’t get an appointment. So, we went to the urgent care next to the H Mart in Cary, N.C. While I was waiting, I thought, let me go get a coffee or an iced tea at the H Mart. They have this French bakery in there.

I went in and ordered my drink, and I was waiting in line. I saw this woman pass me running with a baby. Another woman – I found out later it was her sister – was running after her, and she said: “Call 911!”

“I don’t have my phone,” I said. I left my phone with my son; he was using it.

I said: “Are you okay?” And she just handed me the baby. The baby was gray, and there was blood in her nose and mouth. The woman said: “She’s my baby. She’s 1 week old.”

I was trying to think very quickly. I didn’t see any bubbles in the blood around the baby’s nose or mouth to tell me if she was breathing. She was just limp. The mom was still screaming, but I couldn’t even hear her anymore. It was like I was having an out-of-body experience. All I could hear were my thoughts: “I need to put this baby down to start CPR. Someone was calling 911. I should go in the front of the store to save time, so EMS doesn’t have to look for me when they come.”

I started moving and trying to clean the blood from the baby’s face with her blanket. At the front of the store, I saw a display of rice bags. I put the baby on top of one of the bags. “Okay, where do I check for a pulse on a baby?” I took care of adults, never pediatric patients, never babies. She was so tiny. I put my hand on her chest and felt nothing. No heartbeat. She still wasn’t breathing.

People were around me, but I couldn’t see or hear anybody. All I was thinking was: “What can I do for this patient right now?” I started CPR with two fingers. Nothing was happening. It wasn’t that long, but it felt like forever for me. I couldn’t do mouth-to-mouth because there was so much blood on her face. I still don’t know what caused the bleeding.

It was COVID time, so I had my mask on. I was, like: “You know what? Screw this. She’s a 1-week-old baby. Her lungs are tiny. Maybe I don’t have to do mouth-to-mouth. I can just blow in her mouth.” I took off my mask and opened her mouth. I took a deep breath and blew a little bit of air in her mouth. I continued CPR for maybe 5 or 10 seconds.

And then she gasped! She opened her eyes, but they were rolled up. I was still doing CPR, and maybe 2 second after that, I could feel under my hand a very rapid heart rate. I took my hand away and lifted her up.

Just then the EMS got there. I gave them the baby and said: “I did CPR. I don’t know how long it lasted.” The EMS person looked at me, said: “Thank you for what you did. Now we need you to help us with mom.” I said, “okay.”

I turned around, and the mom was still screaming and crying. I asked one of the ladies that worked there, “Can you get me water?” She brought it, and I gave some to the mom, and she started talking to EMS.

People were asking me: “What happened? What happened?” It’s funny, I guess the nurse in me didn’t want to give out information. And I didn’t want to ask for information. I was thinking about privacy. I said, “I don’t know,” and walked away.

The mom’s sister came and hugged me and said thank you. I was still in this out-of-body zone, and I just wanted to get the hell out of there. So, I left. I went to my car and when I got in it, I started shaking and sweating and crying.

I had been so calm in the moment, not thinking about if the baby was going to survive or not. I didn’t know how long she was without oxygen, if she would have some anoxic brain injury or stroke. I’m a mom, too. I would have been just as terrified as that mom. I just hoped there was a chance that she could take her baby home.

I went back to the urgent care, and my son was, like, “are you okay?” I said: “You will not believe this. I just did CPR on a baby.” He said: “Oh. Okay.” I don’t think he even knew what that meant.

I’ve been an ICU nurse since 2008. I’ve been in very critical moments with patients, life or death situations. I help save people all the time at the hospital. Most of the time, you know what you’re getting. You can prepare. You have everything you need, and everyone knows what to do. You know what the worst will look like. You know the outcome.

But this was something else. You read about things like this. You hear about them. But you never think it’ll happen to you – until it happens.

I couldn’t stop thinking about the baby. So, 2 days later, I posted on Next Door to see if somebody would read it and say, “hey, the baby survived.” I was amazed at how many people responded, but no one knew the family.

The local news got hold of me and asked me to do a story. I told them, “the only way I can do a story is if the baby survived. I’m not going to do a story about a dead baby, and the mom has to live through it again.”

The reporter called me later on that day and said she had talked to the police. They said the family was visiting from out of state. The baby went to the hospital and was discharged home 2 days later. I said, “okay, then I can talk.”

When the news story came out, I started getting texts from people at work the same night. So many people were reaching out. Even people from out of state. But I never heard from the family. No one knew how to reach them.

Since I was very young, I wanted to work in a hospital, to help people. It really brings me joy, seeing somebody go home, knowing, yes, we did this. It’s a great feeling. I love this job. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

I just wish I had asked the mom’s name. Because I always think about that baby. I always wonder, what did she become? I hope somebody reads this who might know that little girl. It would be so nice to meet her one day.

Ms. Diallo is an ICU nurse and now works as nurse care coordinator at the University of North Carolina’s Children’s Neurology Clinic in Chapel Hill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

My son needed a physical for his football team, and we couldn’t get an appointment. So, we went to the urgent care next to the H Mart in Cary, N.C. While I was waiting, I thought, let me go get a coffee or an iced tea at the H Mart. They have this French bakery in there.

I went in and ordered my drink, and I was waiting in line. I saw this woman pass me running with a baby. Another woman – I found out later it was her sister – was running after her, and she said: “Call 911!”

“I don’t have my phone,” I said. I left my phone with my son; he was using it.

I said: “Are you okay?” And she just handed me the baby. The baby was gray, and there was blood in her nose and mouth. The woman said: “She’s my baby. She’s 1 week old.”

I was trying to think very quickly. I didn’t see any bubbles in the blood around the baby’s nose or mouth to tell me if she was breathing. She was just limp. The mom was still screaming, but I couldn’t even hear her anymore. It was like I was having an out-of-body experience. All I could hear were my thoughts: “I need to put this baby down to start CPR. Someone was calling 911. I should go in the front of the store to save time, so EMS doesn’t have to look for me when they come.”

I started moving and trying to clean the blood from the baby’s face with her blanket. At the front of the store, I saw a display of rice bags. I put the baby on top of one of the bags. “Okay, where do I check for a pulse on a baby?” I took care of adults, never pediatric patients, never babies. She was so tiny. I put my hand on her chest and felt nothing. No heartbeat. She still wasn’t breathing.

People were around me, but I couldn’t see or hear anybody. All I was thinking was: “What can I do for this patient right now?” I started CPR with two fingers. Nothing was happening. It wasn’t that long, but it felt like forever for me. I couldn’t do mouth-to-mouth because there was so much blood on her face. I still don’t know what caused the bleeding.

It was COVID time, so I had my mask on. I was, like: “You know what? Screw this. She’s a 1-week-old baby. Her lungs are tiny. Maybe I don’t have to do mouth-to-mouth. I can just blow in her mouth.” I took off my mask and opened her mouth. I took a deep breath and blew a little bit of air in her mouth. I continued CPR for maybe 5 or 10 seconds.

And then she gasped! She opened her eyes, but they were rolled up. I was still doing CPR, and maybe 2 second after that, I could feel under my hand a very rapid heart rate. I took my hand away and lifted her up.

Just then the EMS got there. I gave them the baby and said: “I did CPR. I don’t know how long it lasted.” The EMS person looked at me, said: “Thank you for what you did. Now we need you to help us with mom.” I said, “okay.”

I turned around, and the mom was still screaming and crying. I asked one of the ladies that worked there, “Can you get me water?” She brought it, and I gave some to the mom, and she started talking to EMS.

People were asking me: “What happened? What happened?” It’s funny, I guess the nurse in me didn’t want to give out information. And I didn’t want to ask for information. I was thinking about privacy. I said, “I don’t know,” and walked away.

The mom’s sister came and hugged me and said thank you. I was still in this out-of-body zone, and I just wanted to get the hell out of there. So, I left. I went to my car and when I got in it, I started shaking and sweating and crying.

I had been so calm in the moment, not thinking about if the baby was going to survive or not. I didn’t know how long she was without oxygen, if she would have some anoxic brain injury or stroke. I’m a mom, too. I would have been just as terrified as that mom. I just hoped there was a chance that she could take her baby home.

I went back to the urgent care, and my son was, like, “are you okay?” I said: “You will not believe this. I just did CPR on a baby.” He said: “Oh. Okay.” I don’t think he even knew what that meant.

I’ve been an ICU nurse since 2008. I’ve been in very critical moments with patients, life or death situations. I help save people all the time at the hospital. Most of the time, you know what you’re getting. You can prepare. You have everything you need, and everyone knows what to do. You know what the worst will look like. You know the outcome.

But this was something else. You read about things like this. You hear about them. But you never think it’ll happen to you – until it happens.

I couldn’t stop thinking about the baby. So, 2 days later, I posted on Next Door to see if somebody would read it and say, “hey, the baby survived.” I was amazed at how many people responded, but no one knew the family.

The local news got hold of me and asked me to do a story. I told them, “the only way I can do a story is if the baby survived. I’m not going to do a story about a dead baby, and the mom has to live through it again.”

The reporter called me later on that day and said she had talked to the police. They said the family was visiting from out of state. The baby went to the hospital and was discharged home 2 days later. I said, “okay, then I can talk.”

When the news story came out, I started getting texts from people at work the same night. So many people were reaching out. Even people from out of state. But I never heard from the family. No one knew how to reach them.

Since I was very young, I wanted to work in a hospital, to help people. It really brings me joy, seeing somebody go home, knowing, yes, we did this. It’s a great feeling. I love this job. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

I just wish I had asked the mom’s name. Because I always think about that baby. I always wonder, what did she become? I hope somebody reads this who might know that little girl. It would be so nice to meet her one day.

Ms. Diallo is an ICU nurse and now works as nurse care coordinator at the University of North Carolina’s Children’s Neurology Clinic in Chapel Hill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Green Mediterranean diet may relieve aortic stiffness

A green adaptation to the traditional Mediterranean diet improves proximal aortic stiffness (PAS), a distinct marker of vascular aging and increased cardiovascular risk, according to an exploratory post hoc analysis of the DIRECT-PLUS randomized clinical trial.

The green Mediterranean diet is distinct from the traditional Mediterranean diet because of its more abundant dietary polyphenols, from green tea and a Wolffia globosa (Mankai) plant green shake, and lower intake of red or processed meat.

Independent of weight loss, the modified green Mediterranean diet regressed PAS by 15%, the traditional Mediterranean diet by 7.3%, and the healthy dietary guideline–based diet by 4.8%, the study team observed.

“The DIRECT-PLUS trial research team was the first to introduce the concept of the green-Mediterranean/high polyphenols diet,” lead researcher Iris Shai, RD, PhD, with Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er-Sheva, Israel, told this news organization.

This diet promoted “dramatic proximal aortic de-stiffening” as assessed by MRI over 18 months in roughly 300 participants with abdominal obesity/dyslipidemia. “To date, no dietary strategies have been shown to impact vascular aging physiology,” Dr. Shai said.

The analysis was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Not all healthy diets are equal

Of the 294 participants, 281 had valid PAS measurements at baseline. The baseline PAS (6.1 m/s) was similar across intervention groups (P = .20). Increased PAS was associated with aging, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and visceral adiposity (P < .05).

After 18 months’ intervention (retention rate 89.8%), all diet groups showed significant PAS reductions: –0.05 m/s with the standard healthy diet (4.8%), –0.08 m/s with the traditional Mediterranean diet (7.3%) and –0.15 the green Mediterranean diet (15%).

In the multivariable model, the green Mediterranean dieters had greater PAS reduction than did the healthy-diet and Mediterranean dieters (P = .003 and P = .032, respectively).

The researchers caution that DIRECT-PLUS had multiple endpoints and this exploratory post hoc analysis might be sensitive to type I statistical error and should be considered “hypothesis-generating.”

High-quality study, believable results

Reached for comment on the study, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart in New York, said, “There is not a lot of high-quality research on diet, and I would call this high-quality research in as much as they used randomization which most dietary studies don’t do.

“The greener Mediterranean diet seemed to be the best one on the surrogate marker of MRI-defined aortic stiffness,” Dr. Bhatt, professor of cardiovascular medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“It makes sense that a diet that has more green in it, more polyphenols, would be healthier. This has been shown in some other studies, that these plant-based polyphenols might have various cardiovascular protective aspects to them,” Dr. Bhatt said.

Overall, he said the results are “quite believable, with the caveat that it would be nice to see the results reproduced in a more diverse and larger sample.”

“There is emerging evidence that diets that are higher in fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains and lower in overall caloric intake, in general, seem to be good diets to reduce cardiovascular risk factors and maybe even reduce actual cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Bhatt added.

The study was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), the Rosetrees Trust, Israel Ministry of Health, Israel Ministry of Science and Technology, and the California Walnuts Commission. Dr. Shai and Dr. Bhatt have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A green adaptation to the traditional Mediterranean diet improves proximal aortic stiffness (PAS), a distinct marker of vascular aging and increased cardiovascular risk, according to an exploratory post hoc analysis of the DIRECT-PLUS randomized clinical trial.

The green Mediterranean diet is distinct from the traditional Mediterranean diet because of its more abundant dietary polyphenols, from green tea and a Wolffia globosa (Mankai) plant green shake, and lower intake of red or processed meat.

Independent of weight loss, the modified green Mediterranean diet regressed PAS by 15%, the traditional Mediterranean diet by 7.3%, and the healthy dietary guideline–based diet by 4.8%, the study team observed.

“The DIRECT-PLUS trial research team was the first to introduce the concept of the green-Mediterranean/high polyphenols diet,” lead researcher Iris Shai, RD, PhD, with Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er-Sheva, Israel, told this news organization.

This diet promoted “dramatic proximal aortic de-stiffening” as assessed by MRI over 18 months in roughly 300 participants with abdominal obesity/dyslipidemia. “To date, no dietary strategies have been shown to impact vascular aging physiology,” Dr. Shai said.

The analysis was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Not all healthy diets are equal

Of the 294 participants, 281 had valid PAS measurements at baseline. The baseline PAS (6.1 m/s) was similar across intervention groups (P = .20). Increased PAS was associated with aging, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and visceral adiposity (P < .05).

After 18 months’ intervention (retention rate 89.8%), all diet groups showed significant PAS reductions: –0.05 m/s with the standard healthy diet (4.8%), –0.08 m/s with the traditional Mediterranean diet (7.3%) and –0.15 the green Mediterranean diet (15%).

In the multivariable model, the green Mediterranean dieters had greater PAS reduction than did the healthy-diet and Mediterranean dieters (P = .003 and P = .032, respectively).

The researchers caution that DIRECT-PLUS had multiple endpoints and this exploratory post hoc analysis might be sensitive to type I statistical error and should be considered “hypothesis-generating.”

High-quality study, believable results

Reached for comment on the study, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart in New York, said, “There is not a lot of high-quality research on diet, and I would call this high-quality research in as much as they used randomization which most dietary studies don’t do.

“The greener Mediterranean diet seemed to be the best one on the surrogate marker of MRI-defined aortic stiffness,” Dr. Bhatt, professor of cardiovascular medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“It makes sense that a diet that has more green in it, more polyphenols, would be healthier. This has been shown in some other studies, that these plant-based polyphenols might have various cardiovascular protective aspects to them,” Dr. Bhatt said.

Overall, he said the results are “quite believable, with the caveat that it would be nice to see the results reproduced in a more diverse and larger sample.”

“There is emerging evidence that diets that are higher in fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains and lower in overall caloric intake, in general, seem to be good diets to reduce cardiovascular risk factors and maybe even reduce actual cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Bhatt added.

The study was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), the Rosetrees Trust, Israel Ministry of Health, Israel Ministry of Science and Technology, and the California Walnuts Commission. Dr. Shai and Dr. Bhatt have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A green adaptation to the traditional Mediterranean diet improves proximal aortic stiffness (PAS), a distinct marker of vascular aging and increased cardiovascular risk, according to an exploratory post hoc analysis of the DIRECT-PLUS randomized clinical trial.

The green Mediterranean diet is distinct from the traditional Mediterranean diet because of its more abundant dietary polyphenols, from green tea and a Wolffia globosa (Mankai) plant green shake, and lower intake of red or processed meat.

Independent of weight loss, the modified green Mediterranean diet regressed PAS by 15%, the traditional Mediterranean diet by 7.3%, and the healthy dietary guideline–based diet by 4.8%, the study team observed.

“The DIRECT-PLUS trial research team was the first to introduce the concept of the green-Mediterranean/high polyphenols diet,” lead researcher Iris Shai, RD, PhD, with Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be’er-Sheva, Israel, told this news organization.

This diet promoted “dramatic proximal aortic de-stiffening” as assessed by MRI over 18 months in roughly 300 participants with abdominal obesity/dyslipidemia. “To date, no dietary strategies have been shown to impact vascular aging physiology,” Dr. Shai said.

The analysis was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Not all healthy diets are equal

Of the 294 participants, 281 had valid PAS measurements at baseline. The baseline PAS (6.1 m/s) was similar across intervention groups (P = .20). Increased PAS was associated with aging, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and visceral adiposity (P < .05).

After 18 months’ intervention (retention rate 89.8%), all diet groups showed significant PAS reductions: –0.05 m/s with the standard healthy diet (4.8%), –0.08 m/s with the traditional Mediterranean diet (7.3%) and –0.15 the green Mediterranean diet (15%).

In the multivariable model, the green Mediterranean dieters had greater PAS reduction than did the healthy-diet and Mediterranean dieters (P = .003 and P = .032, respectively).

The researchers caution that DIRECT-PLUS had multiple endpoints and this exploratory post hoc analysis might be sensitive to type I statistical error and should be considered “hypothesis-generating.”

High-quality study, believable results

Reached for comment on the study, Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart in New York, said, “There is not a lot of high-quality research on diet, and I would call this high-quality research in as much as they used randomization which most dietary studies don’t do.

“The greener Mediterranean diet seemed to be the best one on the surrogate marker of MRI-defined aortic stiffness,” Dr. Bhatt, professor of cardiovascular medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who wasn’t involved in the study, told this news organization.

“It makes sense that a diet that has more green in it, more polyphenols, would be healthier. This has been shown in some other studies, that these plant-based polyphenols might have various cardiovascular protective aspects to them,” Dr. Bhatt said.

Overall, he said the results are “quite believable, with the caveat that it would be nice to see the results reproduced in a more diverse and larger sample.”

“There is emerging evidence that diets that are higher in fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains and lower in overall caloric intake, in general, seem to be good diets to reduce cardiovascular risk factors and maybe even reduce actual cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Bhatt added.

The study was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), the Rosetrees Trust, Israel Ministry of Health, Israel Ministry of Science and Technology, and the California Walnuts Commission. Dr. Shai and Dr. Bhatt have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obstructive sleep apnea linked to early cognitive decline

In a pilot study out of King’s College London, participants with severe OSA experienced worse executive functioning as well as social and emotional recognition versus healthy controls.

Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, and being middle-aged or older. Because some researchers have hypothesized that cognitive deficits could be driven by such comorbidities, the study investigators recruited middle-aged men with no medical comorbidities.

“Traditionally, we were more concerned with sleep apnea’s metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, and indeed, when cognitive deficits were demonstrated, most were attributed to them, and yet, our patients and their partners/families commonly tell us differently,” lead investigator Ivana Rosenzweig, MD, PhD, of King’s College London, who is also a consultant in sleep medicine and neuropsychiatry at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, said in an interview.

“Our findings provide a very important first step towards challenging the long-standing dogma that sleep apnea has little to do with the brain – apart from causing sleepiness – and that it is a predominantly nonneuro/psychiatric illness,” added Dr. Rosenzweig.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Sleep.

Brain changes

The researchers wanted to understand how OSA may be linked to cognitive decline in the absence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

To accomplish this, the investigators studied 27 men between the ages of 35 and 70 with a new diagnosis of mild to severe OSA without any comorbidities (16 with mild OSA and 11 with severe OSA). They also studied a control group of seven men matched for age, body mass index, and education level.

The team tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and found that the most significant deficits for the OSA group, compared with controls, were in areas of visual matching ability (P < .0001), short-term visual recognition memory, nonverbal patterns, executive functioning and attentional set-shifting (P < .001), psychomotor functioning, and social cognition and emotional recognition (P < .05).

On the latter two tests, impaired participants were less likely to accurately identify the emotion on computer-generated faces. Those with mild OSA performed better than those with severe OSA on these tasks, but rarely worse than controls.

Dr. Rosenzweig noted that the findings were one-of-a-kind because of the recruitment of patients with OSA who were otherwise healthy and nonobese, “something one rarely sees in the sleep clinic, where we commonly encounter patients with already developed comorbidities.

“In order to truly revolutionize the treatment for our patients, it is important to understand how much the accompanying comorbidities, such as systemic hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other various serious cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and how much the illness itself may shape the demonstrated cognitive deficits,” she said.

She also said that “it is widely agreed that medical problems in middle age may predispose to increased prevalence of dementia in later years.

Moreover, the very link between sleep apnea and Alzheimer’s, vascular and mixed dementia is increasingly demonstrated,” said Dr. Rosenzweig.

Although women typically have a lower prevalence of OSA than men, Dr. Rosenzweig said women were not included in the study “because we are too complex. As a lifelong feminist it pains me to say this, but to get any authoritative answer on our physiology, we need decent funding in place so that we can take into account all the intricacies of the changes of our sleep, physiology, and metabolism.

“While there is always lots of noise about how important it is to answer these questions, there are only very limited funds available for the sleep research,” she added.

Dr. Rosenzweig’s future research will focus on the potential link between OSA and neuroinflammation.

In a comment, Liza Ashbrook, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the findings “add to the growing list of negative health consequences associated with sleep apnea.”

She said that, if the cognitive changes found in the study are, in fact, caused by OSA, it is unclear whether they are the beginning of long-term cognitive changes or a symptom of fragmented sleep that may be reversible.

Dr. Ashbrook said she would be interested in seeing research on understanding the effect of OSA treatment on the affected cognitive domains.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pilot study out of King’s College London, participants with severe OSA experienced worse executive functioning as well as social and emotional recognition versus healthy controls.

Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, and being middle-aged or older. Because some researchers have hypothesized that cognitive deficits could be driven by such comorbidities, the study investigators recruited middle-aged men with no medical comorbidities.

“Traditionally, we were more concerned with sleep apnea’s metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, and indeed, when cognitive deficits were demonstrated, most were attributed to them, and yet, our patients and their partners/families commonly tell us differently,” lead investigator Ivana Rosenzweig, MD, PhD, of King’s College London, who is also a consultant in sleep medicine and neuropsychiatry at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, said in an interview.

“Our findings provide a very important first step towards challenging the long-standing dogma that sleep apnea has little to do with the brain – apart from causing sleepiness – and that it is a predominantly nonneuro/psychiatric illness,” added Dr. Rosenzweig.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Sleep.

Brain changes

The researchers wanted to understand how OSA may be linked to cognitive decline in the absence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

To accomplish this, the investigators studied 27 men between the ages of 35 and 70 with a new diagnosis of mild to severe OSA without any comorbidities (16 with mild OSA and 11 with severe OSA). They also studied a control group of seven men matched for age, body mass index, and education level.

The team tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and found that the most significant deficits for the OSA group, compared with controls, were in areas of visual matching ability (P < .0001), short-term visual recognition memory, nonverbal patterns, executive functioning and attentional set-shifting (P < .001), psychomotor functioning, and social cognition and emotional recognition (P < .05).

On the latter two tests, impaired participants were less likely to accurately identify the emotion on computer-generated faces. Those with mild OSA performed better than those with severe OSA on these tasks, but rarely worse than controls.

Dr. Rosenzweig noted that the findings were one-of-a-kind because of the recruitment of patients with OSA who were otherwise healthy and nonobese, “something one rarely sees in the sleep clinic, where we commonly encounter patients with already developed comorbidities.

“In order to truly revolutionize the treatment for our patients, it is important to understand how much the accompanying comorbidities, such as systemic hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other various serious cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and how much the illness itself may shape the demonstrated cognitive deficits,” she said.

She also said that “it is widely agreed that medical problems in middle age may predispose to increased prevalence of dementia in later years.

Moreover, the very link between sleep apnea and Alzheimer’s, vascular and mixed dementia is increasingly demonstrated,” said Dr. Rosenzweig.

Although women typically have a lower prevalence of OSA than men, Dr. Rosenzweig said women were not included in the study “because we are too complex. As a lifelong feminist it pains me to say this, but to get any authoritative answer on our physiology, we need decent funding in place so that we can take into account all the intricacies of the changes of our sleep, physiology, and metabolism.

“While there is always lots of noise about how important it is to answer these questions, there are only very limited funds available for the sleep research,” she added.

Dr. Rosenzweig’s future research will focus on the potential link between OSA and neuroinflammation.

In a comment, Liza Ashbrook, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the findings “add to the growing list of negative health consequences associated with sleep apnea.”

She said that, if the cognitive changes found in the study are, in fact, caused by OSA, it is unclear whether they are the beginning of long-term cognitive changes or a symptom of fragmented sleep that may be reversible.

Dr. Ashbrook said she would be interested in seeing research on understanding the effect of OSA treatment on the affected cognitive domains.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pilot study out of King’s College London, participants with severe OSA experienced worse executive functioning as well as social and emotional recognition versus healthy controls.

Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, and being middle-aged or older. Because some researchers have hypothesized that cognitive deficits could be driven by such comorbidities, the study investigators recruited middle-aged men with no medical comorbidities.

“Traditionally, we were more concerned with sleep apnea’s metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, and indeed, when cognitive deficits were demonstrated, most were attributed to them, and yet, our patients and their partners/families commonly tell us differently,” lead investigator Ivana Rosenzweig, MD, PhD, of King’s College London, who is also a consultant in sleep medicine and neuropsychiatry at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, said in an interview.

“Our findings provide a very important first step towards challenging the long-standing dogma that sleep apnea has little to do with the brain – apart from causing sleepiness – and that it is a predominantly nonneuro/psychiatric illness,” added Dr. Rosenzweig.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Sleep.

Brain changes

The researchers wanted to understand how OSA may be linked to cognitive decline in the absence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

To accomplish this, the investigators studied 27 men between the ages of 35 and 70 with a new diagnosis of mild to severe OSA without any comorbidities (16 with mild OSA and 11 with severe OSA). They also studied a control group of seven men matched for age, body mass index, and education level.

The team tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and found that the most significant deficits for the OSA group, compared with controls, were in areas of visual matching ability (P < .0001), short-term visual recognition memory, nonverbal patterns, executive functioning and attentional set-shifting (P < .001), psychomotor functioning, and social cognition and emotional recognition (P < .05).

On the latter two tests, impaired participants were less likely to accurately identify the emotion on computer-generated faces. Those with mild OSA performed better than those with severe OSA on these tasks, but rarely worse than controls.

Dr. Rosenzweig noted that the findings were one-of-a-kind because of the recruitment of patients with OSA who were otherwise healthy and nonobese, “something one rarely sees in the sleep clinic, where we commonly encounter patients with already developed comorbidities.

“In order to truly revolutionize the treatment for our patients, it is important to understand how much the accompanying comorbidities, such as systemic hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other various serious cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and how much the illness itself may shape the demonstrated cognitive deficits,” she said.

She also said that “it is widely agreed that medical problems in middle age may predispose to increased prevalence of dementia in later years.

Moreover, the very link between sleep apnea and Alzheimer’s, vascular and mixed dementia is increasingly demonstrated,” said Dr. Rosenzweig.

Although women typically have a lower prevalence of OSA than men, Dr. Rosenzweig said women were not included in the study “because we are too complex. As a lifelong feminist it pains me to say this, but to get any authoritative answer on our physiology, we need decent funding in place so that we can take into account all the intricacies of the changes of our sleep, physiology, and metabolism.

“While there is always lots of noise about how important it is to answer these questions, there are only very limited funds available for the sleep research,” she added.

Dr. Rosenzweig’s future research will focus on the potential link between OSA and neuroinflammation.

In a comment, Liza Ashbrook, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the findings “add to the growing list of negative health consequences associated with sleep apnea.”

She said that, if the cognitive changes found in the study are, in fact, caused by OSA, it is unclear whether they are the beginning of long-term cognitive changes or a symptom of fragmented sleep that may be reversible.

Dr. Ashbrook said she would be interested in seeing research on understanding the effect of OSA treatment on the affected cognitive domains.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FRONTIERS IN SLEEP

Physicians may retire en masse soon. What does that mean for medicine?

The double whammy of pandemic burnout and the aging of baby boomer physicians has, indeed, the makings of some scary headlines. A recent survey by Elsevier Health predicts that up to 75% of health care workers will leave the profession by 2025. And a 2020 study conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) projected a shortfall of up to 139,000 physicians by 2033.

“We’ve paid a lot of attention to physician retirement,” says Michael Dill, AAMC’s director of workforce studies. “It’s a significant concern in terms of whether we have an adequate supply of physicians in the U.S. to meet our nation’s medical care needs. Anyone who thinks otherwise is incorrect.”

To Mr. Dill,

“The physician workforce as a whole is aging,” he said. “Close to a quarter of the physicians in the U.S. are 65 and over. So, you don’t need any extraordinary events driving retirement in order for retirement to be a real phenomenon of which we should all be concerned.”

And, although Mr. Dill said there aren’t any data to suggest that doctors in rural or urban areas are retiring faster than in the suburbs, that doesn’t mean retirement will have the same impact depending on where patients live.

“If you live in a rural area with one small practice in town and that physician retires, there goes the entirety of the physician supply,” he said. “In a major metro area, that’s not as big a deal.”

Why younger doctors are fast-tracking retirement

Fernando Mendoza, MD, 54, a pediatric emergency department physician in Miami, worries that physicians are getting so bogged down by paperwork that this may lead to even more doctors, at younger ages, leaving the profession.

“I love taking care of kids, but there’s going to be a cost to doing your work when you’re spending as much time as we need to spend on charts, pharmacy requests, and making sure all of the Medicare and Medicaid compliance issues are worked out.”

These stressors may compel some younger doctors to consider carving out a second career or fast-track younger physicians toward retirement.

“A medical degree carries a lot of weight, which helps when pivoting,” said Dr. Mendoza, who launched Scrivas, a Miami-based medical scribe agency, to help reduce the paperwork workload for physicians. “It might be that a doctor wants to get involved in the acquisition of medical equipment, or maybe they can focus on their investments. Either way, by leaving medicine, they’re not dealing with the hassle and churn-and-burn of seeing patients.”

What this means for patients

The time is now to stem the upcoming tide of retirement, said Mr. Dill. But the challenges remain daunting. For starters, the country needs more physicians trained now – but it will take years to replace those baby boomer doctors ready to hang up their white coats.

The medical profession also needs to find ways to support physicians who spend their days juggling an endless array of responsibilities, he said.

The AAMC study found that patients already feel the physician shortfall. Their public opinion research in 2019 said 35% of patients had trouble finding a physician over the past 2 or 3 years, up 10 percentage points since they asked the question in 2015.

Moreover, according to the report, the over-65 population is expected to grow by 45.1%, leaving a specialty care gap because older people generally have more complicated health cases that require specialists. In addition, physician burnout may lead more physicians under 65 to retire much earlier than expected.

Changes in how medicine is practiced, telemedicine care, and medical education – such as disruption of classes or clinical rotations, regulatory changes, and a lack of interest in certain specialties – could also be affected by a mass physician retirement.

What can we do about mass retirement?

The AAMC reports in “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034” that federally funded GME support is in the works to train 15,000 physicians per year, with 3,000 new residency slots added per year over 5 years. The proposed model will add 3,750 new physicians each year beginning in 2026.

Other efforts include increasing use of APRNs and PAs, whose population is estimated to more than double by 2034, improve population health through preventive care, increase equity in health outcomes, and improve access and affordable care.

Removing licensing barriers for immigrant doctors can also help alleviate the shortage.

“We need to find better ways to leverage the entirety of the health care team so that not as much falls on physicians,” Mr. Dill said. “It’s also imperative that we focus on ways to support physician wellness and allow physicians to remain active in the field, but at a reduced rate.”

That’s precisely what Marie Brown, MD, director of practice redesign at the American Medical Association, is seeing nationwide. Cutting back their hours is not only trending, but it’s also helping doctors cope with burnout.

“We’re seeing physicians take a 20% or more cut in salary in order to decrease their burden,” she said. “They’ll spend 4 days on clinical time with patients so that on that fifth ‘day off,’ they’re doing the paperwork and documentation they need to do so they don’t compromise care on the other 4 days of the week.”

And this may only be a Band-Aid solution, she fears.

“If a physician is spending 3 hours a day doing unnecessary work that could be done by another team member, that’s contributing to burnout,” Dr. Brown said. “It’s no surprise that they’ll want to escape and retire if they’re in a financial situation to do so.”

“I advocate negotiating within your organization so you’re doing more of what you like, such as mentoring or running a residency, and less of what you don’t, while cutting back from full-time to something less than full-time while maintaining benefits,” said Joel Greenwald, MD, a certified financial planner in Minneapolis, who specializes in helping physicians manage their financial affairs.

“Falling into the ‘like less’ bucket are usually things like working weekends and taking calls,” he said.

“This benefits everyone on a large scale because those doctors who find things they enjoy are generally working to a later age but working less hard,” he said. “Remaining comfortably and happily gainfully employed for a longer period, even if you’re not working full-time, has a very powerful effect on your financial planning, and you’ll avoid the risk of running out of money.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The double whammy of pandemic burnout and the aging of baby boomer physicians has, indeed, the makings of some scary headlines. A recent survey by Elsevier Health predicts that up to 75% of health care workers will leave the profession by 2025. And a 2020 study conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) projected a shortfall of up to 139,000 physicians by 2033.

“We’ve paid a lot of attention to physician retirement,” says Michael Dill, AAMC’s director of workforce studies. “It’s a significant concern in terms of whether we have an adequate supply of physicians in the U.S. to meet our nation’s medical care needs. Anyone who thinks otherwise is incorrect.”

To Mr. Dill,

“The physician workforce as a whole is aging,” he said. “Close to a quarter of the physicians in the U.S. are 65 and over. So, you don’t need any extraordinary events driving retirement in order for retirement to be a real phenomenon of which we should all be concerned.”

And, although Mr. Dill said there aren’t any data to suggest that doctors in rural or urban areas are retiring faster than in the suburbs, that doesn’t mean retirement will have the same impact depending on where patients live.

“If you live in a rural area with one small practice in town and that physician retires, there goes the entirety of the physician supply,” he said. “In a major metro area, that’s not as big a deal.”

Why younger doctors are fast-tracking retirement

Fernando Mendoza, MD, 54, a pediatric emergency department physician in Miami, worries that physicians are getting so bogged down by paperwork that this may lead to even more doctors, at younger ages, leaving the profession.

“I love taking care of kids, but there’s going to be a cost to doing your work when you’re spending as much time as we need to spend on charts, pharmacy requests, and making sure all of the Medicare and Medicaid compliance issues are worked out.”

These stressors may compel some younger doctors to consider carving out a second career or fast-track younger physicians toward retirement.

“A medical degree carries a lot of weight, which helps when pivoting,” said Dr. Mendoza, who launched Scrivas, a Miami-based medical scribe agency, to help reduce the paperwork workload for physicians. “It might be that a doctor wants to get involved in the acquisition of medical equipment, or maybe they can focus on their investments. Either way, by leaving medicine, they’re not dealing with the hassle and churn-and-burn of seeing patients.”

What this means for patients

The time is now to stem the upcoming tide of retirement, said Mr. Dill. But the challenges remain daunting. For starters, the country needs more physicians trained now – but it will take years to replace those baby boomer doctors ready to hang up their white coats.

The medical profession also needs to find ways to support physicians who spend their days juggling an endless array of responsibilities, he said.

The AAMC study found that patients already feel the physician shortfall. Their public opinion research in 2019 said 35% of patients had trouble finding a physician over the past 2 or 3 years, up 10 percentage points since they asked the question in 2015.

Moreover, according to the report, the over-65 population is expected to grow by 45.1%, leaving a specialty care gap because older people generally have more complicated health cases that require specialists. In addition, physician burnout may lead more physicians under 65 to retire much earlier than expected.

Changes in how medicine is practiced, telemedicine care, and medical education – such as disruption of classes or clinical rotations, regulatory changes, and a lack of interest in certain specialties – could also be affected by a mass physician retirement.

What can we do about mass retirement?

The AAMC reports in “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034” that federally funded GME support is in the works to train 15,000 physicians per year, with 3,000 new residency slots added per year over 5 years. The proposed model will add 3,750 new physicians each year beginning in 2026.

Other efforts include increasing use of APRNs and PAs, whose population is estimated to more than double by 2034, improve population health through preventive care, increase equity in health outcomes, and improve access and affordable care.

Removing licensing barriers for immigrant doctors can also help alleviate the shortage.

“We need to find better ways to leverage the entirety of the health care team so that not as much falls on physicians,” Mr. Dill said. “It’s also imperative that we focus on ways to support physician wellness and allow physicians to remain active in the field, but at a reduced rate.”

That’s precisely what Marie Brown, MD, director of practice redesign at the American Medical Association, is seeing nationwide. Cutting back their hours is not only trending, but it’s also helping doctors cope with burnout.

“We’re seeing physicians take a 20% or more cut in salary in order to decrease their burden,” she said. “They’ll spend 4 days on clinical time with patients so that on that fifth ‘day off,’ they’re doing the paperwork and documentation they need to do so they don’t compromise care on the other 4 days of the week.”

And this may only be a Band-Aid solution, she fears.

“If a physician is spending 3 hours a day doing unnecessary work that could be done by another team member, that’s contributing to burnout,” Dr. Brown said. “It’s no surprise that they’ll want to escape and retire if they’re in a financial situation to do so.”

“I advocate negotiating within your organization so you’re doing more of what you like, such as mentoring or running a residency, and less of what you don’t, while cutting back from full-time to something less than full-time while maintaining benefits,” said Joel Greenwald, MD, a certified financial planner in Minneapolis, who specializes in helping physicians manage their financial affairs.

“Falling into the ‘like less’ bucket are usually things like working weekends and taking calls,” he said.

“This benefits everyone on a large scale because those doctors who find things they enjoy are generally working to a later age but working less hard,” he said. “Remaining comfortably and happily gainfully employed for a longer period, even if you’re not working full-time, has a very powerful effect on your financial planning, and you’ll avoid the risk of running out of money.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The double whammy of pandemic burnout and the aging of baby boomer physicians has, indeed, the makings of some scary headlines. A recent survey by Elsevier Health predicts that up to 75% of health care workers will leave the profession by 2025. And a 2020 study conducted by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) projected a shortfall of up to 139,000 physicians by 2033.

“We’ve paid a lot of attention to physician retirement,” says Michael Dill, AAMC’s director of workforce studies. “It’s a significant concern in terms of whether we have an adequate supply of physicians in the U.S. to meet our nation’s medical care needs. Anyone who thinks otherwise is incorrect.”

To Mr. Dill,

“The physician workforce as a whole is aging,” he said. “Close to a quarter of the physicians in the U.S. are 65 and over. So, you don’t need any extraordinary events driving retirement in order for retirement to be a real phenomenon of which we should all be concerned.”

And, although Mr. Dill said there aren’t any data to suggest that doctors in rural or urban areas are retiring faster than in the suburbs, that doesn’t mean retirement will have the same impact depending on where patients live.

“If you live in a rural area with one small practice in town and that physician retires, there goes the entirety of the physician supply,” he said. “In a major metro area, that’s not as big a deal.”

Why younger doctors are fast-tracking retirement

Fernando Mendoza, MD, 54, a pediatric emergency department physician in Miami, worries that physicians are getting so bogged down by paperwork that this may lead to even more doctors, at younger ages, leaving the profession.

“I love taking care of kids, but there’s going to be a cost to doing your work when you’re spending as much time as we need to spend on charts, pharmacy requests, and making sure all of the Medicare and Medicaid compliance issues are worked out.”

These stressors may compel some younger doctors to consider carving out a second career or fast-track younger physicians toward retirement.

“A medical degree carries a lot of weight, which helps when pivoting,” said Dr. Mendoza, who launched Scrivas, a Miami-based medical scribe agency, to help reduce the paperwork workload for physicians. “It might be that a doctor wants to get involved in the acquisition of medical equipment, or maybe they can focus on their investments. Either way, by leaving medicine, they’re not dealing with the hassle and churn-and-burn of seeing patients.”

What this means for patients

The time is now to stem the upcoming tide of retirement, said Mr. Dill. But the challenges remain daunting. For starters, the country needs more physicians trained now – but it will take years to replace those baby boomer doctors ready to hang up their white coats.

The medical profession also needs to find ways to support physicians who spend their days juggling an endless array of responsibilities, he said.

The AAMC study found that patients already feel the physician shortfall. Their public opinion research in 2019 said 35% of patients had trouble finding a physician over the past 2 or 3 years, up 10 percentage points since they asked the question in 2015.

Moreover, according to the report, the over-65 population is expected to grow by 45.1%, leaving a specialty care gap because older people generally have more complicated health cases that require specialists. In addition, physician burnout may lead more physicians under 65 to retire much earlier than expected.

Changes in how medicine is practiced, telemedicine care, and medical education – such as disruption of classes or clinical rotations, regulatory changes, and a lack of interest in certain specialties – could also be affected by a mass physician retirement.

What can we do about mass retirement?

The AAMC reports in “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034” that federally funded GME support is in the works to train 15,000 physicians per year, with 3,000 new residency slots added per year over 5 years. The proposed model will add 3,750 new physicians each year beginning in 2026.

Other efforts include increasing use of APRNs and PAs, whose population is estimated to more than double by 2034, improve population health through preventive care, increase equity in health outcomes, and improve access and affordable care.

Removing licensing barriers for immigrant doctors can also help alleviate the shortage.

“We need to find better ways to leverage the entirety of the health care team so that not as much falls on physicians,” Mr. Dill said. “It’s also imperative that we focus on ways to support physician wellness and allow physicians to remain active in the field, but at a reduced rate.”

That’s precisely what Marie Brown, MD, director of practice redesign at the American Medical Association, is seeing nationwide. Cutting back their hours is not only trending, but it’s also helping doctors cope with burnout.

“We’re seeing physicians take a 20% or more cut in salary in order to decrease their burden,” she said. “They’ll spend 4 days on clinical time with patients so that on that fifth ‘day off,’ they’re doing the paperwork and documentation they need to do so they don’t compromise care on the other 4 days of the week.”

And this may only be a Band-Aid solution, she fears.

“If a physician is spending 3 hours a day doing unnecessary work that could be done by another team member, that’s contributing to burnout,” Dr. Brown said. “It’s no surprise that they’ll want to escape and retire if they’re in a financial situation to do so.”

“I advocate negotiating within your organization so you’re doing more of what you like, such as mentoring or running a residency, and less of what you don’t, while cutting back from full-time to something less than full-time while maintaining benefits,” said Joel Greenwald, MD, a certified financial planner in Minneapolis, who specializes in helping physicians manage their financial affairs.

“Falling into the ‘like less’ bucket are usually things like working weekends and taking calls,” he said.

“This benefits everyone on a large scale because those doctors who find things they enjoy are generally working to a later age but working less hard,” he said. “Remaining comfortably and happily gainfully employed for a longer period, even if you’re not working full-time, has a very powerful effect on your financial planning, and you’ll avoid the risk of running out of money.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physician compensation continues to climb amid postpandemic change

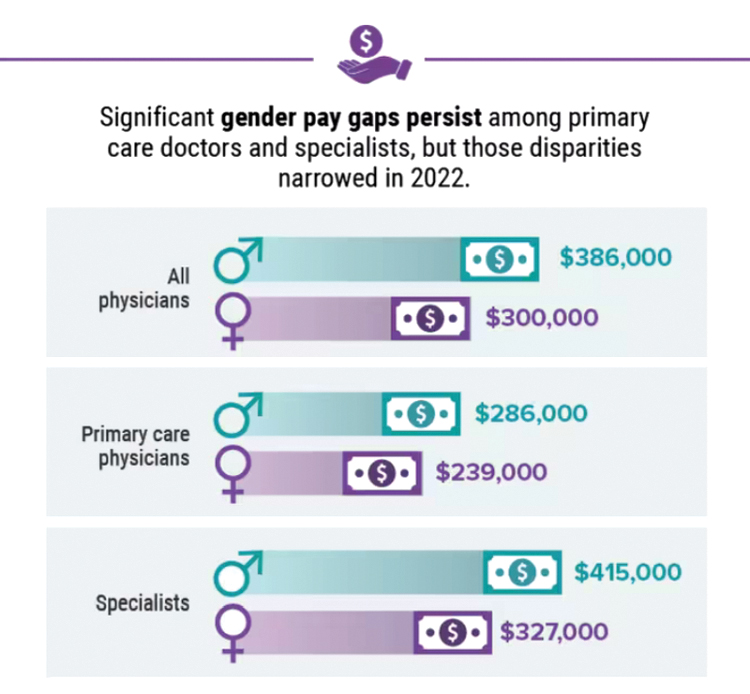

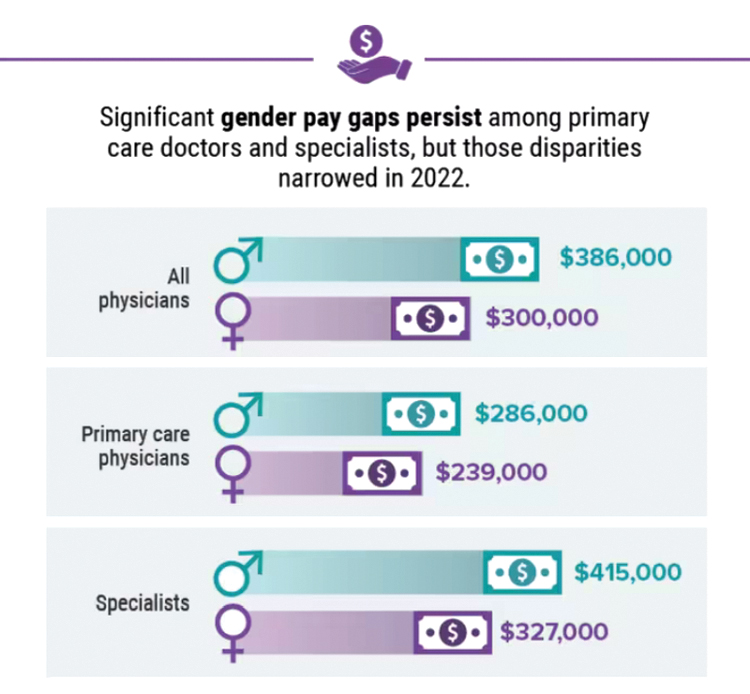

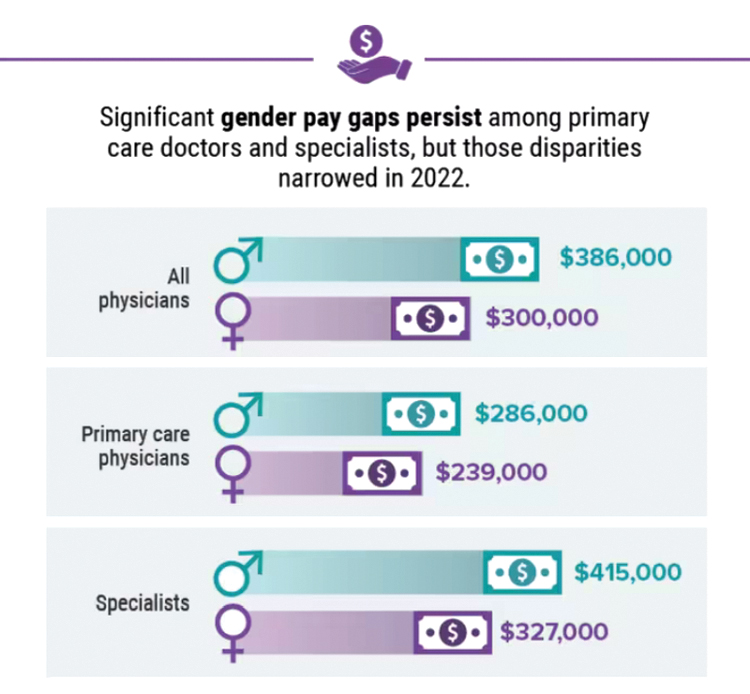

In addition, gender-based pay disparity among primary care physicians shrank, and the number of physicians who declined to take new Medicare patients rose.

The annual report is based on a survey of more than 10,000 physicians in over 29 specialties who answered questions about their income, workload, challenges, and level of satisfaction.

Average compensation across specialties rose to $352,000 – up nearly 17% from the 2018 average of $299,000. Fallout from the COVID-19 public health emergency continued to affect both physician compensation and job satisfaction, including Medicare reimbursements and staffing shortages due to burnout or retirement.

“Many physicians reevaluated what drove them to be a physician,” says Marc Adam, a recruiter at MASC Medical, a Florida physician recruiting firm.

Adam cites telehealth as an example. “An overwhelming majority of physicians prefer telehealth because of the convenience, but some really did not want to do it long term. They miss the patient interaction.”

The report also revealed that the gender-based pay gap in primary physicians fell, with men earning 19% more – down from 25% more in recent years. Among specialists, the gender gap was 27% on average, down from 31% last year. One reason may be an increase in compensation transparency, which Mr. Adam says should be the norm.

Income increases will likely continue, owing in large part to the growing disparity between physician supply and demand.

The projected physician shortage is expected to grow to 124,000 by 2034, according to the American Association of Medical Colleges. Federal lawmakers are considering passing the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2023, which would add 14,000 Medicare-funded residency positions to help alleviate shortages.

Patient needs, Medicare rules continue to shift

Specialties with the biggest increases in compensation include oncology, anesthesiology, gastroenterology, radiology, critical care, and urology. Many procedure-related specialties saw more volume post pandemic.

Some respondents identified Medicare cuts and low reimbursement rates as a factor in tamping down compensation hikes. The number of physicians who expect to continue to take new Medicare patients is 65%, down from 71% 5 years ago.

For example, Medicare reimbursements for telehealth are expected to scale down in May, when the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, which expanded telehealth services for Medicare patients, winds down.

“Telehealth will still exist,” says Mr. Adam, “but certain requirements will shape it going forward.”

Medicare isn’t viewed negatively across the board, however. Florida is among the top-earning states for physicians – along with Indiana, Connecticut, and Missouri. One reason is Florida’s unique health care environment, explains Mr. Adam, whose Florida-based firm places physicians nationwide.

“Florida is very progressive in terms of health care. For one thing, we have a large aging population and a large Medicare population.” Several growing organizations that focus on quality-based care are based in Florida, including ChenMed and Cano Health. Add to that the fact that owners of Florida’s health care organizations don’t have to be physicians, he explains, and the stage is set for experimentation.

“Being able to segment tasks frees up physicians to be more focused on medicine and provide better care while other people focus on the business and innovation.”

If Florida’s high compensation ranking continues, it may help employers there fulfill a growing need. The state is among those expected to experience the largest physician shortages in 2030, along with California, Texas, Arizona, and Georgia.

Side gigs up, satisfaction (slightly) down

In general, physicians aren’t fazed by these challenges. Many reported taking side gigs, some for additional income. Even so, 73% say they would still choose medicine, and more than 90% of physicians in 10 specialties would choose their specialty again. Still, burnout and stressors have led some to stop practicing altogether.

More and more organizations are hiring “travel physicians,” Mr. Adam says, and more physicians are choosing to take contract work (“locum tenens”) and practice in many different regions. Contract physicians typically help meet patient demand or provide coverage during the hiring process as well as while staff are on vacation or maternity leave.

Says Mr. Adam, “There’s no security, but there’s higher income and more flexibility.”

According to CHG Healthcare, locum tenens staffing is rising – approximately 7% of U.S. physicians (around 50,000) filled assignments in 2022, up 88% from 2015. In 2022, 56% of locum tenens employers reported a reduction in staff burnout, up from 30% in 2020.

The report indicates that more than half of physicians are satisfied with their income, down slightly from 55% 5 years ago (prepandemic). Physicians in some of the lower-paying specialties are among those most satisfied with their income. It’s not very surprising to Mr. Adam: “Higher earners generally suffer the most from burnout.

“They’re overworked, they have the largest number of patients, and they’re performing in high-stress situations doing challenging procedures on a daily basis – and they probably have worse work-life balance.” These physicians know going in that they need to be paid more to deal with such burdens. “That’s the feedback I get when I speak to high earners,” says Mr. Adam.

“The experienced ones are very clear about their [compensation] expectations.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, gender-based pay disparity among primary care physicians shrank, and the number of physicians who declined to take new Medicare patients rose.

The annual report is based on a survey of more than 10,000 physicians in over 29 specialties who answered questions about their income, workload, challenges, and level of satisfaction.

Average compensation across specialties rose to $352,000 – up nearly 17% from the 2018 average of $299,000. Fallout from the COVID-19 public health emergency continued to affect both physician compensation and job satisfaction, including Medicare reimbursements and staffing shortages due to burnout or retirement.

“Many physicians reevaluated what drove them to be a physician,” says Marc Adam, a recruiter at MASC Medical, a Florida physician recruiting firm.

Adam cites telehealth as an example. “An overwhelming majority of physicians prefer telehealth because of the convenience, but some really did not want to do it long term. They miss the patient interaction.”

The report also revealed that the gender-based pay gap in primary physicians fell, with men earning 19% more – down from 25% more in recent years. Among specialists, the gender gap was 27% on average, down from 31% last year. One reason may be an increase in compensation transparency, which Mr. Adam says should be the norm.

Income increases will likely continue, owing in large part to the growing disparity between physician supply and demand.

The projected physician shortage is expected to grow to 124,000 by 2034, according to the American Association of Medical Colleges. Federal lawmakers are considering passing the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2023, which would add 14,000 Medicare-funded residency positions to help alleviate shortages.

Patient needs, Medicare rules continue to shift

Specialties with the biggest increases in compensation include oncology, anesthesiology, gastroenterology, radiology, critical care, and urology. Many procedure-related specialties saw more volume post pandemic.

Some respondents identified Medicare cuts and low reimbursement rates as a factor in tamping down compensation hikes. The number of physicians who expect to continue to take new Medicare patients is 65%, down from 71% 5 years ago.

For example, Medicare reimbursements for telehealth are expected to scale down in May, when the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, which expanded telehealth services for Medicare patients, winds down.

“Telehealth will still exist,” says Mr. Adam, “but certain requirements will shape it going forward.”

Medicare isn’t viewed negatively across the board, however. Florida is among the top-earning states for physicians – along with Indiana, Connecticut, and Missouri. One reason is Florida’s unique health care environment, explains Mr. Adam, whose Florida-based firm places physicians nationwide.

“Florida is very progressive in terms of health care. For one thing, we have a large aging population and a large Medicare population.” Several growing organizations that focus on quality-based care are based in Florida, including ChenMed and Cano Health. Add to that the fact that owners of Florida’s health care organizations don’t have to be physicians, he explains, and the stage is set for experimentation.

“Being able to segment tasks frees up physicians to be more focused on medicine and provide better care while other people focus on the business and innovation.”

If Florida’s high compensation ranking continues, it may help employers there fulfill a growing need. The state is among those expected to experience the largest physician shortages in 2030, along with California, Texas, Arizona, and Georgia.

Side gigs up, satisfaction (slightly) down

In general, physicians aren’t fazed by these challenges. Many reported taking side gigs, some for additional income. Even so, 73% say they would still choose medicine, and more than 90% of physicians in 10 specialties would choose their specialty again. Still, burnout and stressors have led some to stop practicing altogether.

More and more organizations are hiring “travel physicians,” Mr. Adam says, and more physicians are choosing to take contract work (“locum tenens”) and practice in many different regions. Contract physicians typically help meet patient demand or provide coverage during the hiring process as well as while staff are on vacation or maternity leave.

Says Mr. Adam, “There’s no security, but there’s higher income and more flexibility.”

According to CHG Healthcare, locum tenens staffing is rising – approximately 7% of U.S. physicians (around 50,000) filled assignments in 2022, up 88% from 2015. In 2022, 56% of locum tenens employers reported a reduction in staff burnout, up from 30% in 2020.

The report indicates that more than half of physicians are satisfied with their income, down slightly from 55% 5 years ago (prepandemic). Physicians in some of the lower-paying specialties are among those most satisfied with their income. It’s not very surprising to Mr. Adam: “Higher earners generally suffer the most from burnout.

“They’re overworked, they have the largest number of patients, and they’re performing in high-stress situations doing challenging procedures on a daily basis – and they probably have worse work-life balance.” These physicians know going in that they need to be paid more to deal with such burdens. “That’s the feedback I get when I speak to high earners,” says Mr. Adam.

“The experienced ones are very clear about their [compensation] expectations.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, gender-based pay disparity among primary care physicians shrank, and the number of physicians who declined to take new Medicare patients rose.

The annual report is based on a survey of more than 10,000 physicians in over 29 specialties who answered questions about their income, workload, challenges, and level of satisfaction.

Average compensation across specialties rose to $352,000 – up nearly 17% from the 2018 average of $299,000. Fallout from the COVID-19 public health emergency continued to affect both physician compensation and job satisfaction, including Medicare reimbursements and staffing shortages due to burnout or retirement.

“Many physicians reevaluated what drove them to be a physician,” says Marc Adam, a recruiter at MASC Medical, a Florida physician recruiting firm.