User login

Red eyes with a brown spot

A 32-year-old woman came to the rescue mission clinic with her 2 sons because she had red eyes and a runny nose. Her sons both had symptoms highly suggestive of viral upper respiratory infection. They lived in a homeless shelter.

The patient stated she did not use contact lenses or have any eye trauma, itching, photophobia, loss or change of vision, eye pain, eye discharge, or previous episodes of pinkeye. She had no other medical problems or history of allergies.

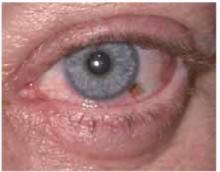

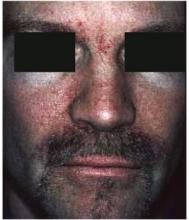

On physical exam, her vital signs were normal. She had conjunctival injection, without purulent discharge or limbal blush (Figures 1 and 2). Eyelids were mildly erythematous with no cobble-stoning. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. The anterior chamber by flashlight exam from the side did not show a narrow angle. Visual acuity was normal by Snellen exam. She had clear nasal discharge and bilateral preauricular lymphadenopathy.

In addition, she had a brown macule under the left iris on the conjunctiva. The patient said this had been present since childhood and it had not changed.

FIGURE 1

Red eyes

FIGURE 2

Brown macule

What is the differential iagnosis?

What about the brown macule?

Are any diagnostic tests Necessary for either condition?

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a red eye includes:

- Conjunctivitis

- Uveitis

- Acute glaucoma

- Corneal disease or foreign body trauma

- Scleritis and episcleritis.1

For this patient, conjunctivitis is the most likely diagnosis. The absence of eye pain or loss of vision makes uveitis, acute glaucoma, or corneal disease (including foreign-body trauma) less likely. The round shape of the pupil and the absence of the limbal blush also make uveitis less likely. The pattern of injection does not match the wedge-shaped inflammation of episcleritis or the depth of scleritis.

Diagnosis: viral conjunctivitis

This patient has viral conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis can be infectious, allergic, chemical/irritative, or autoimmune in origin. The most common infectious agents are viral—specifically, the adenoviruses. Other infectious agents include bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae), chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus.

Both infectious and allergic conjunctivitis are common. In this patient, the presence of nasal discharge, preauricular lymphadenopathy, and the lack of pruritus make viral infection more likely than allergic. Conjunctivitis that is bilateral without purulent discharge is more likely to be viral than bacterial.

What about the brown macule?

This patient also had a brown macule on her conjunctiva. The differential diagnosis of pigmented areas on the conjunctiva includes nevus, racial melanosis, primary acquired melanosis, secondary pigmentary deposition, and ocular melanoma.2 These conditions (besides ocular melanoma) are benign.

Although ocular melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, and the second most likely location for primary melanoma after the skin, it is still exceedingly rare. In the Causasian population, it has an average annual incidence of 6 cases per million, with approximately 1200 cases diagnosed each year. Ocular melanoma occurs in the uvea much more commonly than in the conjunctiva, at a ratio of 35:1. Conjunctival melanomas have a propensity for regional spread to the lymph nodes analogous to cutaneous disease, with 10-year survival rates of more than 80%.3

In this case, the patient had this dark spot since childhood and had noted no growth or change. It was consistent with a conjunctival nevus and did not need biopsy.

Diagnostic tests: only for cases that do not respond

When viral conjunctivitis is suspected, no laboratory tests are routinely recommended. Bacterial and viral cultures may be helpful to establish the diagnosis in cases that do not resolve or when patients have recurrent episodes. Infections that do not respond to empiric treatment should be cultured for the suspected organisms (bacteria, chlamydia, or herpes simplex). When chlamydial conjunctivitis is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed by means of an immunodiagnostic test (direct fluorescent antibody [DFA]) or culture (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).4

A fluorescein exam is helpful in cases with a question of corneal involvement from foreign-body trauma, herpes simplex, or epidemic kerato-conjunctivitis. Herpes simplex infections have a dendritic pattern of ulceration, and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis infections cause multiple small areas of increased fluorescein uptake.

Management: conjunctivitis usually self-limiting

Typical viral conjunctivitis caused by the adenoviruses or other common viruses (not herpes) does not require medication. Warm compresses may be recommended to reduce discomfort. Infectious conjunctivitis caused by bacteria are also usually self-limiting; however, a recent meta-analysis indicates that treatment with antibiotics can shorten the clinical duration (LOE=1a).5

Appropriate medications for bacterial conjunctivitis include 0.3% tobramycin or gentamycin, 10% sodium sulfacetamide, or erythromycin ophthalmic ointment. If herpetic keratoconjuntivitis is suspected, prompt ophthalmologic referral is indicated.1

Patient’s treatment and outcome

This patient was managed with reassurance and symptomatic treatment of her viral respiratory illness. Her red eyes and upper respiratory infection both resolved spontaneously within 1 week.

As her nevus had not changed in many years, she was instructed to continue to watch the nevus and report any changes to a physician for evaluation. If the lesion changed in the future, she should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

- Erythromycin (ophthalmic) • Ilotycin

- Gentamycin (ophthalmic) • Garamycin, Genoptic Liquifilm, Genoptic SOP, Gentacidin, Gentafair, Gentak, Ocu-Mycin, Spectro-Genta

- Sulfacetamide (ophthalmic) • AK-Sulf, Bleph-10, Cetamide, Isopto Cetamide, Ocusulf-10, Sodium Sulamyd, Sulf-10

- Tobramycin (ophthalmic) • AKTob, Tobrex

Correspondence

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Ricketson CW. Conjunctivitis in 5-minute clinical consult. Dambro, MR (ed). InfoRetriever [electronic database]. Charlottesville, Va: InfoPOEMs, Inc; 2004.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49:3-24.

3. Hurst EA, Harbour JW, Cornelius LA. Ocular melanoma: a review and the relationship to cutaneous melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1067-1073.

4. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Patterns. Conjunctivitis. Available at: www.aao.org/aao/education/library/ppp/index.cfm. Accessed on February 3, 2004.

5. Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, Cave J. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2003.

A 32-year-old woman came to the rescue mission clinic with her 2 sons because she had red eyes and a runny nose. Her sons both had symptoms highly suggestive of viral upper respiratory infection. They lived in a homeless shelter.

The patient stated she did not use contact lenses or have any eye trauma, itching, photophobia, loss or change of vision, eye pain, eye discharge, or previous episodes of pinkeye. She had no other medical problems or history of allergies.

On physical exam, her vital signs were normal. She had conjunctival injection, without purulent discharge or limbal blush (Figures 1 and 2). Eyelids were mildly erythematous with no cobble-stoning. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. The anterior chamber by flashlight exam from the side did not show a narrow angle. Visual acuity was normal by Snellen exam. She had clear nasal discharge and bilateral preauricular lymphadenopathy.

In addition, she had a brown macule under the left iris on the conjunctiva. The patient said this had been present since childhood and it had not changed.

FIGURE 1

Red eyes

FIGURE 2

Brown macule

What is the differential iagnosis?

What about the brown macule?

Are any diagnostic tests Necessary for either condition?

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a red eye includes:

- Conjunctivitis

- Uveitis

- Acute glaucoma

- Corneal disease or foreign body trauma

- Scleritis and episcleritis.1

For this patient, conjunctivitis is the most likely diagnosis. The absence of eye pain or loss of vision makes uveitis, acute glaucoma, or corneal disease (including foreign-body trauma) less likely. The round shape of the pupil and the absence of the limbal blush also make uveitis less likely. The pattern of injection does not match the wedge-shaped inflammation of episcleritis or the depth of scleritis.

Diagnosis: viral conjunctivitis

This patient has viral conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis can be infectious, allergic, chemical/irritative, or autoimmune in origin. The most common infectious agents are viral—specifically, the adenoviruses. Other infectious agents include bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae), chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus.

Both infectious and allergic conjunctivitis are common. In this patient, the presence of nasal discharge, preauricular lymphadenopathy, and the lack of pruritus make viral infection more likely than allergic. Conjunctivitis that is bilateral without purulent discharge is more likely to be viral than bacterial.

What about the brown macule?

This patient also had a brown macule on her conjunctiva. The differential diagnosis of pigmented areas on the conjunctiva includes nevus, racial melanosis, primary acquired melanosis, secondary pigmentary deposition, and ocular melanoma.2 These conditions (besides ocular melanoma) are benign.

Although ocular melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, and the second most likely location for primary melanoma after the skin, it is still exceedingly rare. In the Causasian population, it has an average annual incidence of 6 cases per million, with approximately 1200 cases diagnosed each year. Ocular melanoma occurs in the uvea much more commonly than in the conjunctiva, at a ratio of 35:1. Conjunctival melanomas have a propensity for regional spread to the lymph nodes analogous to cutaneous disease, with 10-year survival rates of more than 80%.3

In this case, the patient had this dark spot since childhood and had noted no growth or change. It was consistent with a conjunctival nevus and did not need biopsy.

Diagnostic tests: only for cases that do not respond

When viral conjunctivitis is suspected, no laboratory tests are routinely recommended. Bacterial and viral cultures may be helpful to establish the diagnosis in cases that do not resolve or when patients have recurrent episodes. Infections that do not respond to empiric treatment should be cultured for the suspected organisms (bacteria, chlamydia, or herpes simplex). When chlamydial conjunctivitis is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed by means of an immunodiagnostic test (direct fluorescent antibody [DFA]) or culture (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).4

A fluorescein exam is helpful in cases with a question of corneal involvement from foreign-body trauma, herpes simplex, or epidemic kerato-conjunctivitis. Herpes simplex infections have a dendritic pattern of ulceration, and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis infections cause multiple small areas of increased fluorescein uptake.

Management: conjunctivitis usually self-limiting

Typical viral conjunctivitis caused by the adenoviruses or other common viruses (not herpes) does not require medication. Warm compresses may be recommended to reduce discomfort. Infectious conjunctivitis caused by bacteria are also usually self-limiting; however, a recent meta-analysis indicates that treatment with antibiotics can shorten the clinical duration (LOE=1a).5

Appropriate medications for bacterial conjunctivitis include 0.3% tobramycin or gentamycin, 10% sodium sulfacetamide, or erythromycin ophthalmic ointment. If herpetic keratoconjuntivitis is suspected, prompt ophthalmologic referral is indicated.1

Patient’s treatment and outcome

This patient was managed with reassurance and symptomatic treatment of her viral respiratory illness. Her red eyes and upper respiratory infection both resolved spontaneously within 1 week.

As her nevus had not changed in many years, she was instructed to continue to watch the nevus and report any changes to a physician for evaluation. If the lesion changed in the future, she should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

- Erythromycin (ophthalmic) • Ilotycin

- Gentamycin (ophthalmic) • Garamycin, Genoptic Liquifilm, Genoptic SOP, Gentacidin, Gentafair, Gentak, Ocu-Mycin, Spectro-Genta

- Sulfacetamide (ophthalmic) • AK-Sulf, Bleph-10, Cetamide, Isopto Cetamide, Ocusulf-10, Sodium Sulamyd, Sulf-10

- Tobramycin (ophthalmic) • AKTob, Tobrex

Correspondence

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected].

A 32-year-old woman came to the rescue mission clinic with her 2 sons because she had red eyes and a runny nose. Her sons both had symptoms highly suggestive of viral upper respiratory infection. They lived in a homeless shelter.

The patient stated she did not use contact lenses or have any eye trauma, itching, photophobia, loss or change of vision, eye pain, eye discharge, or previous episodes of pinkeye. She had no other medical problems or history of allergies.

On physical exam, her vital signs were normal. She had conjunctival injection, without purulent discharge or limbal blush (Figures 1 and 2). Eyelids were mildly erythematous with no cobble-stoning. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. The anterior chamber by flashlight exam from the side did not show a narrow angle. Visual acuity was normal by Snellen exam. She had clear nasal discharge and bilateral preauricular lymphadenopathy.

In addition, she had a brown macule under the left iris on the conjunctiva. The patient said this had been present since childhood and it had not changed.

FIGURE 1

Red eyes

FIGURE 2

Brown macule

What is the differential iagnosis?

What about the brown macule?

Are any diagnostic tests Necessary for either condition?

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a red eye includes:

- Conjunctivitis

- Uveitis

- Acute glaucoma

- Corneal disease or foreign body trauma

- Scleritis and episcleritis.1

For this patient, conjunctivitis is the most likely diagnosis. The absence of eye pain or loss of vision makes uveitis, acute glaucoma, or corneal disease (including foreign-body trauma) less likely. The round shape of the pupil and the absence of the limbal blush also make uveitis less likely. The pattern of injection does not match the wedge-shaped inflammation of episcleritis or the depth of scleritis.

Diagnosis: viral conjunctivitis

This patient has viral conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis can be infectious, allergic, chemical/irritative, or autoimmune in origin. The most common infectious agents are viral—specifically, the adenoviruses. Other infectious agents include bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae), chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus.

Both infectious and allergic conjunctivitis are common. In this patient, the presence of nasal discharge, preauricular lymphadenopathy, and the lack of pruritus make viral infection more likely than allergic. Conjunctivitis that is bilateral without purulent discharge is more likely to be viral than bacterial.

What about the brown macule?

This patient also had a brown macule on her conjunctiva. The differential diagnosis of pigmented areas on the conjunctiva includes nevus, racial melanosis, primary acquired melanosis, secondary pigmentary deposition, and ocular melanoma.2 These conditions (besides ocular melanoma) are benign.

Although ocular melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, and the second most likely location for primary melanoma after the skin, it is still exceedingly rare. In the Causasian population, it has an average annual incidence of 6 cases per million, with approximately 1200 cases diagnosed each year. Ocular melanoma occurs in the uvea much more commonly than in the conjunctiva, at a ratio of 35:1. Conjunctival melanomas have a propensity for regional spread to the lymph nodes analogous to cutaneous disease, with 10-year survival rates of more than 80%.3

In this case, the patient had this dark spot since childhood and had noted no growth or change. It was consistent with a conjunctival nevus and did not need biopsy.

Diagnostic tests: only for cases that do not respond

When viral conjunctivitis is suspected, no laboratory tests are routinely recommended. Bacterial and viral cultures may be helpful to establish the diagnosis in cases that do not resolve or when patients have recurrent episodes. Infections that do not respond to empiric treatment should be cultured for the suspected organisms (bacteria, chlamydia, or herpes simplex). When chlamydial conjunctivitis is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed by means of an immunodiagnostic test (direct fluorescent antibody [DFA]) or culture (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).4

A fluorescein exam is helpful in cases with a question of corneal involvement from foreign-body trauma, herpes simplex, or epidemic kerato-conjunctivitis. Herpes simplex infections have a dendritic pattern of ulceration, and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis infections cause multiple small areas of increased fluorescein uptake.

Management: conjunctivitis usually self-limiting

Typical viral conjunctivitis caused by the adenoviruses or other common viruses (not herpes) does not require medication. Warm compresses may be recommended to reduce discomfort. Infectious conjunctivitis caused by bacteria are also usually self-limiting; however, a recent meta-analysis indicates that treatment with antibiotics can shorten the clinical duration (LOE=1a).5

Appropriate medications for bacterial conjunctivitis include 0.3% tobramycin or gentamycin, 10% sodium sulfacetamide, or erythromycin ophthalmic ointment. If herpetic keratoconjuntivitis is suspected, prompt ophthalmologic referral is indicated.1

Patient’s treatment and outcome

This patient was managed with reassurance and symptomatic treatment of her viral respiratory illness. Her red eyes and upper respiratory infection both resolved spontaneously within 1 week.

As her nevus had not changed in many years, she was instructed to continue to watch the nevus and report any changes to a physician for evaluation. If the lesion changed in the future, she should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

- Erythromycin (ophthalmic) • Ilotycin

- Gentamycin (ophthalmic) • Garamycin, Genoptic Liquifilm, Genoptic SOP, Gentacidin, Gentafair, Gentak, Ocu-Mycin, Spectro-Genta

- Sulfacetamide (ophthalmic) • AK-Sulf, Bleph-10, Cetamide, Isopto Cetamide, Ocusulf-10, Sodium Sulamyd, Sulf-10

- Tobramycin (ophthalmic) • AKTob, Tobrex

Correspondence

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Ricketson CW. Conjunctivitis in 5-minute clinical consult. Dambro, MR (ed). InfoRetriever [electronic database]. Charlottesville, Va: InfoPOEMs, Inc; 2004.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49:3-24.

3. Hurst EA, Harbour JW, Cornelius LA. Ocular melanoma: a review and the relationship to cutaneous melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1067-1073.

4. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Patterns. Conjunctivitis. Available at: www.aao.org/aao/education/library/ppp/index.cfm. Accessed on February 3, 2004.

5. Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, Cave J. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2003.

1. Ricketson CW. Conjunctivitis in 5-minute clinical consult. Dambro, MR (ed). InfoRetriever [electronic database]. Charlottesville, Va: InfoPOEMs, Inc; 2004.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv Ophthalmol 2004;49:3-24.

3. Hurst EA, Harbour JW, Cornelius LA. Ocular melanoma: a review and the relationship to cutaneous melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1067-1073.

4. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Patterns. Conjunctivitis. Available at: www.aao.org/aao/education/library/ppp/index.cfm. Accessed on February 3, 2004.

5. Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, Cave J. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2003.

Bald spots on a young girl

An 8-year-old Hispanic girl was brought to see her family physician by her mother, who noticed 2 bald spots on the back of her daughter’s scalp while brushing her hair. The child had no itching or pain. No obvious precipitating events preceded the hair loss.

The mother was more worried than the child: she didn’t want to see her beautiful girl become bald. The girl was pleased that the bald spots could be completely covered with her long hair, but she didn’t want anyone to see them. The child was otherwise healthy. She did not have any chronic medical problems and was not taking any medications. No one else in the family had a similar problem.

When the mother lifted the hair in the back, 2 round areas of hair loss were evident (Figure 1). On close inspection, there was no scaling or scarring. Her nails were normal. The child was afebrile, and the remainder of her exam was unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

Two round areas of hair loss

What is the diagnosis?

What are the management options?

Diagnosis: alopecia areata

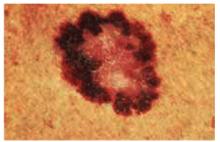

This is the typical appearance of alopecia areata, a chronic inflammatory disease that affects the hair follicles, causing sudden hair loss. Sometimes it affects the nails as well.1 Alopecia areata occurs in both males and females of all ages and races.

Alopecia areata may be an autoimmune disease, though this is unproven. The affected skin may be slightly erythematous but otherwise appears normal. Short broken hairs (exclamation-mark hairs) may be seen around the margins of expanding patches of baldness. The nails are involved in about 10% of patients with severe enough alopecia to be referred to a specialist.1

Many cases begin in childhood and can be psychologically devastating. Alopecia areata is part of a spectrum of diseases with mild to extensive hair loss (Figure 2), including alopecia totalis, in which all the hair on the scalp is lost, and alopecia universalis (Figure 3), in which all the hair on the body is lost. Extensive involvement, early age of onset, and Down syndrome are all poor prognostic factors for alopecia areata.

FIGURE 2

More extensive alopecia

FIGURE 3

Alopecia universalis

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for alopecia areata includes tinea capitis, trichotillomania, early scarring alopecia, telogen effluvium, anagen effluvium (drug-induced), systemic and discoid lupus erythematosus, and secondary syphilis. In most cases the history and physical exam are adequate to make the diagnosis.

This patient does not have the typical scalp scaling and inflammation seen with tinea capitis. Trichotillomania—hair loss caused by the purposeful pulling of hair by the patient—is likely to cause the most confusion because it coexists with alopecia areata in some cases. This child has shown no evidence of such behavior. She also has no evidence of scalp scarring as may be seen in lupus. Telogen effluvium and anagen effluvium cause a more even distribution of hair loss. The patient has no known risk factors for secondary syphilis.

Laboratory testing

No lab tests are needed in this case. If there were some scalp scaling or inflammation, a potassium hydroxide preparation of the involved area would be useful to look for fungal elements; a fungal culture might also be warranted. If needed, further investigations might include serological testing for lupus erythematosus and syphilis, and a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is still unknown.

Treatment: time, drug therapies, aromatherapy

Spontaneous remission occurs in up to 80% of patients with limited patchy hair loss of less than 1 year.1 Spontaneous remission rates are significantly lower with more extensive hair loss.

Treatments are potentially painful, expensive, or time-consuming, and few randomized controlled trials support their use. Often the best treatment is watching for spontaneous remission.

The only adverse health effect of alopecia areata is the psychological distress that it may cause. While this is not to be taken lightly, the lack of evidence for successful treatments needs to be weighed with the patient’s ability to cope with leaving the hair loss untreated over time. In cases of extensive hair loss, the best treatment may be a wig.

For patients that have more visible and extensive areas of hair loss, the psychological impact might prompt the patient to want any treatment available despite the lack of evidence. Alopecia totalis or universalis may cause considerable psychological and social disability. Patients can be referred to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation for support groups and additional information. Individual counseling may be needed for some patients.

National Alopecia Areata Foundation Web site: www.alopeciaareata.com. Patients can order a 7-minute video, This Weird Thing That Makes My Hair Fall Out: Alopecia Areata, which is available for any children who want a way to share their feelings about alopecia areata with friends, family, peers, schoolmates, principals, and teachers.

European Hair Research Society Web site: www.ehrs.org. Web site has links to several alopecia areata sites.

Steroid injections

Intralesional steroid injections may stimulate regrowth of hair at the site of injection (level of evidence [LOE]=5).1 The effect may last a few months, but there is no evidence that it improves the long-term outcome or increases the probability of a cure. New areas of alopecia can still develop.

Injections are typically performed with 5–10 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetonide using a small-gauge needle. Most children will not be able to tolerate the scalp injections and should not be forced to endure this type of therapy even if the parent is pushing for it.

Other medications

Topical diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) is a contact immunotherapy that has some proven benefit with extensive alopecia areata (LOE=2b).1,2 In 1 study, 56 patients with chronic, extensive alopecia areata (duration ranging from 1 to 10 years, involving 30% to 100% of the scalp) were treated with progressively higher concentrations of DPCP in a randomized crossover trial.2 Twenty-five of 56 patients had total hair regrowth at 6 months, and no relapse occurred in 60% of patients. Side effects included local inflammation, eczema, autosensitization reaction, and eyelid edema.

Unfortunately, contact immunotherapy involves multiple visits to the office over several months, and it stimulates cosmetically worthwhile hair regrowth in <50% of patients with extensive patchy hair loss.1 It is a reasonable alternative for patients who do not have spontaneous remission after 1 year.

While potent topical steroids and topical minoxidil are prescribed for limited patchy alopecia areata, no convincing evidence shows they are effective.1 Likewise, no evidence warrants the use systemic steroids or psoralen/ultraviolet light treatment (PUVA).1

Aromatherapy

The best evidence may be for aromatherapy. A single-blinded randomized controlled trial was performed with 86 patients.3 As Dr Ebell points out in his InfoPOEMs review of this study, aromatherapy involves rubbing scented essential oils into the skin to treat localized and systemic disease.4 Patients with alopecia areata were randomized to nightly aromatherapy—with Thymus vulgaris (thyme), Lavandula angustifolia (lavender), Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary), and Cedrus atlantica (cedar)—or to a control consisting of carrier oils only.

Improvement was seen in 54% of the treatment group and 21% of the control group (P=.008; number needed to treat=3). Of the 19 patients in the active treatment group who reported improvement, 11 had “very good” or “excellent” improvement. The results show aromatherapy to be a safe and effective treatment for alopecia areata (LOE=1b).4

The main problem with this study is that the researchers did not describe the duration of the patients’ alopecia. However, in a reply to a letter, they described the patients as having had alopecia areata from less than 1 year to more than 9 years. This explains the low improvement rates in both groups but does not invalidate the statistically significant difference for those that received the essential oils.

Conclusion of visit, follow-up

For a mild case like this in which the hair loss can be hidden, the best treatment is reassurance and observation. The physician explained the natural history of the disease, including the fact that regrowth will take at least 3 months for any single patch. Therapeutic options were also discussed. The mother and child were reassured that the hair is likely to grow in on its own. Neither of them wanted intralesional injections or topical therapies.

One year later during a well-child check, it was noted that the girl’s hair had fully regrown.

1. MacDonald Hull SP, Wood ML, Hutchinson PE, Sladden M, Messenger AG. Guidelines for the management of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:692-699.

2. Cotellessa C, Peris K, Caracciolo E, Mordenti C, Chimenti S. The use of topical diphenylcyclopropenone for the treatment of extensive alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:73-76.

3. Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy: successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Derm 1998;134:1349-1352.

4. Ebell M. Aromatherapy effective for alopecia areata. Review of Hay et al 1998. InfoPOEMs, Inc. March 1999.

An 8-year-old Hispanic girl was brought to see her family physician by her mother, who noticed 2 bald spots on the back of her daughter’s scalp while brushing her hair. The child had no itching or pain. No obvious precipitating events preceded the hair loss.

The mother was more worried than the child: she didn’t want to see her beautiful girl become bald. The girl was pleased that the bald spots could be completely covered with her long hair, but she didn’t want anyone to see them. The child was otherwise healthy. She did not have any chronic medical problems and was not taking any medications. No one else in the family had a similar problem.

When the mother lifted the hair in the back, 2 round areas of hair loss were evident (Figure 1). On close inspection, there was no scaling or scarring. Her nails were normal. The child was afebrile, and the remainder of her exam was unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

Two round areas of hair loss

What is the diagnosis?

What are the management options?

Diagnosis: alopecia areata

This is the typical appearance of alopecia areata, a chronic inflammatory disease that affects the hair follicles, causing sudden hair loss. Sometimes it affects the nails as well.1 Alopecia areata occurs in both males and females of all ages and races.

Alopecia areata may be an autoimmune disease, though this is unproven. The affected skin may be slightly erythematous but otherwise appears normal. Short broken hairs (exclamation-mark hairs) may be seen around the margins of expanding patches of baldness. The nails are involved in about 10% of patients with severe enough alopecia to be referred to a specialist.1

Many cases begin in childhood and can be psychologically devastating. Alopecia areata is part of a spectrum of diseases with mild to extensive hair loss (Figure 2), including alopecia totalis, in which all the hair on the scalp is lost, and alopecia universalis (Figure 3), in which all the hair on the body is lost. Extensive involvement, early age of onset, and Down syndrome are all poor prognostic factors for alopecia areata.

FIGURE 2

More extensive alopecia

FIGURE 3

Alopecia universalis

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for alopecia areata includes tinea capitis, trichotillomania, early scarring alopecia, telogen effluvium, anagen effluvium (drug-induced), systemic and discoid lupus erythematosus, and secondary syphilis. In most cases the history and physical exam are adequate to make the diagnosis.

This patient does not have the typical scalp scaling and inflammation seen with tinea capitis. Trichotillomania—hair loss caused by the purposeful pulling of hair by the patient—is likely to cause the most confusion because it coexists with alopecia areata in some cases. This child has shown no evidence of such behavior. She also has no evidence of scalp scarring as may be seen in lupus. Telogen effluvium and anagen effluvium cause a more even distribution of hair loss. The patient has no known risk factors for secondary syphilis.

Laboratory testing

No lab tests are needed in this case. If there were some scalp scaling or inflammation, a potassium hydroxide preparation of the involved area would be useful to look for fungal elements; a fungal culture might also be warranted. If needed, further investigations might include serological testing for lupus erythematosus and syphilis, and a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is still unknown.

Treatment: time, drug therapies, aromatherapy

Spontaneous remission occurs in up to 80% of patients with limited patchy hair loss of less than 1 year.1 Spontaneous remission rates are significantly lower with more extensive hair loss.

Treatments are potentially painful, expensive, or time-consuming, and few randomized controlled trials support their use. Often the best treatment is watching for spontaneous remission.

The only adverse health effect of alopecia areata is the psychological distress that it may cause. While this is not to be taken lightly, the lack of evidence for successful treatments needs to be weighed with the patient’s ability to cope with leaving the hair loss untreated over time. In cases of extensive hair loss, the best treatment may be a wig.

For patients that have more visible and extensive areas of hair loss, the psychological impact might prompt the patient to want any treatment available despite the lack of evidence. Alopecia totalis or universalis may cause considerable psychological and social disability. Patients can be referred to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation for support groups and additional information. Individual counseling may be needed for some patients.

National Alopecia Areata Foundation Web site: www.alopeciaareata.com. Patients can order a 7-minute video, This Weird Thing That Makes My Hair Fall Out: Alopecia Areata, which is available for any children who want a way to share their feelings about alopecia areata with friends, family, peers, schoolmates, principals, and teachers.

European Hair Research Society Web site: www.ehrs.org. Web site has links to several alopecia areata sites.

Steroid injections

Intralesional steroid injections may stimulate regrowth of hair at the site of injection (level of evidence [LOE]=5).1 The effect may last a few months, but there is no evidence that it improves the long-term outcome or increases the probability of a cure. New areas of alopecia can still develop.

Injections are typically performed with 5–10 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetonide using a small-gauge needle. Most children will not be able to tolerate the scalp injections and should not be forced to endure this type of therapy even if the parent is pushing for it.

Other medications

Topical diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) is a contact immunotherapy that has some proven benefit with extensive alopecia areata (LOE=2b).1,2 In 1 study, 56 patients with chronic, extensive alopecia areata (duration ranging from 1 to 10 years, involving 30% to 100% of the scalp) were treated with progressively higher concentrations of DPCP in a randomized crossover trial.2 Twenty-five of 56 patients had total hair regrowth at 6 months, and no relapse occurred in 60% of patients. Side effects included local inflammation, eczema, autosensitization reaction, and eyelid edema.

Unfortunately, contact immunotherapy involves multiple visits to the office over several months, and it stimulates cosmetically worthwhile hair regrowth in <50% of patients with extensive patchy hair loss.1 It is a reasonable alternative for patients who do not have spontaneous remission after 1 year.

While potent topical steroids and topical minoxidil are prescribed for limited patchy alopecia areata, no convincing evidence shows they are effective.1 Likewise, no evidence warrants the use systemic steroids or psoralen/ultraviolet light treatment (PUVA).1

Aromatherapy

The best evidence may be for aromatherapy. A single-blinded randomized controlled trial was performed with 86 patients.3 As Dr Ebell points out in his InfoPOEMs review of this study, aromatherapy involves rubbing scented essential oils into the skin to treat localized and systemic disease.4 Patients with alopecia areata were randomized to nightly aromatherapy—with Thymus vulgaris (thyme), Lavandula angustifolia (lavender), Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary), and Cedrus atlantica (cedar)—or to a control consisting of carrier oils only.

Improvement was seen in 54% of the treatment group and 21% of the control group (P=.008; number needed to treat=3). Of the 19 patients in the active treatment group who reported improvement, 11 had “very good” or “excellent” improvement. The results show aromatherapy to be a safe and effective treatment for alopecia areata (LOE=1b).4

The main problem with this study is that the researchers did not describe the duration of the patients’ alopecia. However, in a reply to a letter, they described the patients as having had alopecia areata from less than 1 year to more than 9 years. This explains the low improvement rates in both groups but does not invalidate the statistically significant difference for those that received the essential oils.

Conclusion of visit, follow-up

For a mild case like this in which the hair loss can be hidden, the best treatment is reassurance and observation. The physician explained the natural history of the disease, including the fact that regrowth will take at least 3 months for any single patch. Therapeutic options were also discussed. The mother and child were reassured that the hair is likely to grow in on its own. Neither of them wanted intralesional injections or topical therapies.

One year later during a well-child check, it was noted that the girl’s hair had fully regrown.

An 8-year-old Hispanic girl was brought to see her family physician by her mother, who noticed 2 bald spots on the back of her daughter’s scalp while brushing her hair. The child had no itching or pain. No obvious precipitating events preceded the hair loss.

The mother was more worried than the child: she didn’t want to see her beautiful girl become bald. The girl was pleased that the bald spots could be completely covered with her long hair, but she didn’t want anyone to see them. The child was otherwise healthy. She did not have any chronic medical problems and was not taking any medications. No one else in the family had a similar problem.

When the mother lifted the hair in the back, 2 round areas of hair loss were evident (Figure 1). On close inspection, there was no scaling or scarring. Her nails were normal. The child was afebrile, and the remainder of her exam was unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

Two round areas of hair loss

What is the diagnosis?

What are the management options?

Diagnosis: alopecia areata

This is the typical appearance of alopecia areata, a chronic inflammatory disease that affects the hair follicles, causing sudden hair loss. Sometimes it affects the nails as well.1 Alopecia areata occurs in both males and females of all ages and races.

Alopecia areata may be an autoimmune disease, though this is unproven. The affected skin may be slightly erythematous but otherwise appears normal. Short broken hairs (exclamation-mark hairs) may be seen around the margins of expanding patches of baldness. The nails are involved in about 10% of patients with severe enough alopecia to be referred to a specialist.1

Many cases begin in childhood and can be psychologically devastating. Alopecia areata is part of a spectrum of diseases with mild to extensive hair loss (Figure 2), including alopecia totalis, in which all the hair on the scalp is lost, and alopecia universalis (Figure 3), in which all the hair on the body is lost. Extensive involvement, early age of onset, and Down syndrome are all poor prognostic factors for alopecia areata.

FIGURE 2

More extensive alopecia

FIGURE 3

Alopecia universalis

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for alopecia areata includes tinea capitis, trichotillomania, early scarring alopecia, telogen effluvium, anagen effluvium (drug-induced), systemic and discoid lupus erythematosus, and secondary syphilis. In most cases the history and physical exam are adequate to make the diagnosis.

This patient does not have the typical scalp scaling and inflammation seen with tinea capitis. Trichotillomania—hair loss caused by the purposeful pulling of hair by the patient—is likely to cause the most confusion because it coexists with alopecia areata in some cases. This child has shown no evidence of such behavior. She also has no evidence of scalp scarring as may be seen in lupus. Telogen effluvium and anagen effluvium cause a more even distribution of hair loss. The patient has no known risk factors for secondary syphilis.

Laboratory testing

No lab tests are needed in this case. If there were some scalp scaling or inflammation, a potassium hydroxide preparation of the involved area would be useful to look for fungal elements; a fungal culture might also be warranted. If needed, further investigations might include serological testing for lupus erythematosus and syphilis, and a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is still unknown.

Treatment: time, drug therapies, aromatherapy

Spontaneous remission occurs in up to 80% of patients with limited patchy hair loss of less than 1 year.1 Spontaneous remission rates are significantly lower with more extensive hair loss.

Treatments are potentially painful, expensive, or time-consuming, and few randomized controlled trials support their use. Often the best treatment is watching for spontaneous remission.

The only adverse health effect of alopecia areata is the psychological distress that it may cause. While this is not to be taken lightly, the lack of evidence for successful treatments needs to be weighed with the patient’s ability to cope with leaving the hair loss untreated over time. In cases of extensive hair loss, the best treatment may be a wig.

For patients that have more visible and extensive areas of hair loss, the psychological impact might prompt the patient to want any treatment available despite the lack of evidence. Alopecia totalis or universalis may cause considerable psychological and social disability. Patients can be referred to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation for support groups and additional information. Individual counseling may be needed for some patients.

National Alopecia Areata Foundation Web site: www.alopeciaareata.com. Patients can order a 7-minute video, This Weird Thing That Makes My Hair Fall Out: Alopecia Areata, which is available for any children who want a way to share their feelings about alopecia areata with friends, family, peers, schoolmates, principals, and teachers.

European Hair Research Society Web site: www.ehrs.org. Web site has links to several alopecia areata sites.

Steroid injections

Intralesional steroid injections may stimulate regrowth of hair at the site of injection (level of evidence [LOE]=5).1 The effect may last a few months, but there is no evidence that it improves the long-term outcome or increases the probability of a cure. New areas of alopecia can still develop.

Injections are typically performed with 5–10 mg/mL of triamcinolone acetonide using a small-gauge needle. Most children will not be able to tolerate the scalp injections and should not be forced to endure this type of therapy even if the parent is pushing for it.

Other medications

Topical diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) is a contact immunotherapy that has some proven benefit with extensive alopecia areata (LOE=2b).1,2 In 1 study, 56 patients with chronic, extensive alopecia areata (duration ranging from 1 to 10 years, involving 30% to 100% of the scalp) were treated with progressively higher concentrations of DPCP in a randomized crossover trial.2 Twenty-five of 56 patients had total hair regrowth at 6 months, and no relapse occurred in 60% of patients. Side effects included local inflammation, eczema, autosensitization reaction, and eyelid edema.

Unfortunately, contact immunotherapy involves multiple visits to the office over several months, and it stimulates cosmetically worthwhile hair regrowth in <50% of patients with extensive patchy hair loss.1 It is a reasonable alternative for patients who do not have spontaneous remission after 1 year.

While potent topical steroids and topical minoxidil are prescribed for limited patchy alopecia areata, no convincing evidence shows they are effective.1 Likewise, no evidence warrants the use systemic steroids or psoralen/ultraviolet light treatment (PUVA).1

Aromatherapy

The best evidence may be for aromatherapy. A single-blinded randomized controlled trial was performed with 86 patients.3 As Dr Ebell points out in his InfoPOEMs review of this study, aromatherapy involves rubbing scented essential oils into the skin to treat localized and systemic disease.4 Patients with alopecia areata were randomized to nightly aromatherapy—with Thymus vulgaris (thyme), Lavandula angustifolia (lavender), Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary), and Cedrus atlantica (cedar)—or to a control consisting of carrier oils only.

Improvement was seen in 54% of the treatment group and 21% of the control group (P=.008; number needed to treat=3). Of the 19 patients in the active treatment group who reported improvement, 11 had “very good” or “excellent” improvement. The results show aromatherapy to be a safe and effective treatment for alopecia areata (LOE=1b).4

The main problem with this study is that the researchers did not describe the duration of the patients’ alopecia. However, in a reply to a letter, they described the patients as having had alopecia areata from less than 1 year to more than 9 years. This explains the low improvement rates in both groups but does not invalidate the statistically significant difference for those that received the essential oils.

Conclusion of visit, follow-up

For a mild case like this in which the hair loss can be hidden, the best treatment is reassurance and observation. The physician explained the natural history of the disease, including the fact that regrowth will take at least 3 months for any single patch. Therapeutic options were also discussed. The mother and child were reassured that the hair is likely to grow in on its own. Neither of them wanted intralesional injections or topical therapies.

One year later during a well-child check, it was noted that the girl’s hair had fully regrown.

1. MacDonald Hull SP, Wood ML, Hutchinson PE, Sladden M, Messenger AG. Guidelines for the management of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:692-699.

2. Cotellessa C, Peris K, Caracciolo E, Mordenti C, Chimenti S. The use of topical diphenylcyclopropenone for the treatment of extensive alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:73-76.

3. Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy: successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Derm 1998;134:1349-1352.

4. Ebell M. Aromatherapy effective for alopecia areata. Review of Hay et al 1998. InfoPOEMs, Inc. March 1999.

1. MacDonald Hull SP, Wood ML, Hutchinson PE, Sladden M, Messenger AG. Guidelines for the management of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:692-699.

2. Cotellessa C, Peris K, Caracciolo E, Mordenti C, Chimenti S. The use of topical diphenylcyclopropenone for the treatment of extensive alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:73-76.

3. Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy: successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Derm 1998;134:1349-1352.

4. Ebell M. Aromatherapy effective for alopecia areata. Review of Hay et al 1998. InfoPOEMs, Inc. March 1999.

Painful genital ulcers

A colleague came into the charting area and said he thought he had just seen his first case of chancroid. He asked me if I had a moment to see the patient, a 32-year-old African American man who noted the onset of painful sores on his penis 1 week ago. The patient consented to a second opinion. On further questioning, he remembered a tingling pain that started a few days prior to the sores. When asked about any previous outbreaks, he thought he may have had something like this 1 year ago. He did not remember seeing blisters before the sores appeared.

The last time the patient had sexual relations was 2 months ago, with someone he met at a party. He claimed he used a condom. He did not have any lesions at that time and had never had a sexually transmitted disease before.

He had recently fallen in love, and was concerned about these ulcers—he did not want to give her any diseases. They had only kissed so far and he wanted to know what he should tell her. He said he had never had sex with men or injected any drugs. He has had a number of serially monogamous relationships and reported no other human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk factors.

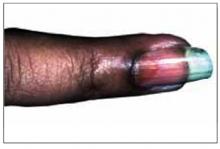

The patient was a healthy-looking young man. Examination of his penis (Figure 1) showed the ulcers clearly visible (Figure 2). He had only shotty inguinal adenopathy that was nontender.

FIGURE 1

Painful sores on the genitals

FIGURE 2

Close-up of ulcers on the penis

What is the diagnosis?

What is the treatment and prevention strategy?

Differential diagnosis

The most likely causes of painful genital ulcers in this case are herpes simplex, chancroid, and syphilis. Granuloma inguinale and lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) are rare causes of genital ulceration in the United States. A zipper accident or other trauma can cause genital ulceration, but the patient should be able to give a clear history of such an event.

By epidemiology alone, the order of likelihood for the cause of any genital ulceration is herpes, syphilis, then chancroid.

This case points to herpes

Herpes simplex is by far the most common cause of painful genital ulcers in the United States; at least 50 million people have genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection1 The features of this case pointing to herpes are the appearance of multiple ulcers, the tingling pain that preceded the ulcers, and the history of a possible episode in the preceding year. While it would be helpful to have a history of blisters that preceded the ulcers, the evidence still points to herpes as the most likely diagnosis.

Could it be syphilis?

While the primary chancre of syphilis is classically described as painless, the patient with syphilis may experience pain. Syphilis tends to present as a single ulcer but may cause multiple ulcers.

Why not chancroid?

Chancroid may also cause multiple small painful ulcers. However, the ulcers of chancroid tend to be deeper than those of herpes and bleed more easily.

Other characteristics to look for

All of these sexually transmitted diseases can cause tender painful adenopathy, which is particularly characteristic of chancroid and LGV. Suppurative inguinal adenopathy with painful genital ulcers is almost pathognomonic of chancroid. With LGV, there may be a self-limited genital ulcer at the site of inoculation, which is often gone by the time a patient seeks care. Granuloma inguinale causes painless, progressive ulcerative lesions without regional lymphadenopathy. These lesions are highly vascular (with a characteristic beefy red appearance) and bleed easily on contact.1 While it would be helpful to have a history of blisters that preceded the ulcers, the evidence still points to herpes as the most likely diagnosis.

Laboratory examination

Herpes

All patients with genital ulcers thought to be from an STD should be tested for syphilis and HIV regardless of other risk factors.1 This patient should additionally be tested for herpes simplex. A bacteriologic test for chancroid is not necessary, but the clinician who first saw the patient asked that we conduct the test for chancroid—a culture for the Haemophilus ducreyi bacterium.

Isolation of HSV in cell culture is the preferred virologic test for patients with genital ulcers.1Unfortunately, the sensitivity of culture declines rapidly as lesions begin to heal, usually within a few days of onset. Direct fluorescent antibody tests are also available. Both herpes culture and the direct fluorescent antibody test distinguish HSV-1 from HSV-2. Polymerase chain reaction assays for HSV DNA are highly sensitive, but their role in the diagnosis of genital ulcer disease has not been well-defined.

Most cases of recurrent genital herpes are caused by HSV-2. Specific serologic testing can be expensive, and is not needed at the time of the initial virologic screening. However, consider ordering the test at a subsequent visit, because the distinction between HSV serotypes influences prognosis and counseling. Also, because false-negative HSV cultures are common—especially with recurrent infection or healing lesions—type-specific serologic tests are useful for confirming a diagnosis of genital herpes.1 Herpes serologies can also be used to help manage sexual partners of persons with genital herpes.

Syphilis

The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test should be used to detect syphilis. Both tests are used for nonspecific screening only, because they measure anticardiolipin antibodies. A positive result should be confirmed with a specific treponemal test such as a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS).

The results of these laboratory tests are not available immediately during the patient’s visit. If there was a high suspicion for syphilis, a dark field examination from the ulcer exudate could be used to look for spirochetes while the patient was still in the office. In this case, the suspicion for syphilis was low.

Treatment: Antivirals

The major question is whether the patient should be treated empirically with medication. The most likely diagnosis is herpes simplex. Randomized trials indicate that 3 antiviral medications— acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir—provide clinical benefit for genital herpes (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).1

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002 treatment guidelines for STDs recommend the following medications for the first clinical episode of genital herpes:

- Acyclovir 400 mg orally, 3 times daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved, OR

- Acyclovir 200 mg orally, 5 times daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved, OR

- Famciclovir 250 mg orally, 3 times daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved, OR

- Valacyclovir 1 g orally, twice daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved.

Topical acyclovir is less effective than the oral formulaton and its use is discouraged.

The suspicion for syphilis is too low to warrant an intramuscular shot of penicillin, which is painful and can cause anaphylaxis in some patients. The likelihood of chancroid is too low to prescribe an oral antibiotic such as erythromycin.

The patient wanted empirical treatment for herpes. He was given valacyclovir, 1 gm for 7 days, taken twice daily, with the option to call in for more if the ulcers did not resolve by day 7. He was told he might apply petrolatum and clean gauze to the ulcers to diminish the pain when open ulcers rub against underwear. Acetaminophen or other analgesics were recommended for pain, and he was advised to avoid sexual activity until the ulcers had fully healed.

Preventing transmission

The patient is appropriately concerned about the transmission of this condition to a new partner. Not having a firm diagnosis makes definitive counseling more difficult. However, general principles of safe sex and condom use were discussed. On the follow-up visit the patient was told that the result of his herpes test was positive for HSV-2. Results of his RPR, HIV antibody test, and H ducreyiculture were all negative.

Information about condom use was reinforced, and the patient was told there is definitive evidence that condom use does diminish the risk of transmission of herpes from a man to a woman (LOE=1b).2 That same study did not show that condom use prevents transmission from women to men. Also, changes in sexual behavior, correlated with counseling about avoiding sex when a partner has lesions, were associated with reduction in HSV-2 acquisition over time (LOE=1b).2

One study showed that the overall risk of genital HSV transmission in couples is low (10%/year). The risk may be significantly increased in women and in seronegative individuals.3 This speaks for serologic testing for the potential partner of this patient.

When recurrences are frequent, antiviral agents can decrease the frequency (LOE=1a).1 If this patient has frequent recurrences, antiviral agents would be appropriate and would decrease the times when the patient is shedding virus asymptomatically.

Herpes is transmitted between sexual partners during asymptomatic shedding.1 Acyclovir 400 mg twice daily can reduce asymptomatic viral shedding significantly among women with recurrent herpes simplex (LOE=1b).4 While it is likely this will decrease transmission from women to men, this has not been proven. Data on decreasing viral transmission from men to women by antiviral therapy is not available. At some point, the Glycoprotein-D-adjuvant vaccine may be an option to prevent genital herpes transmission to his partner.5

Note. The CDC 2002 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines are available for download and use on a Palm handheld computer at www.cdcnpin.org/scripts/std/pda.asp.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-6).-Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/. Accessed on November 4, 2003.

2. Wald A, Langenberg AG, Link K, et al. Effect of condoms on reducing the transmission of herpes simplex virus type 2 from men to women. JAMA 2001;285:31003106.

3. Bryson Y, Dillon M, Bernstein DI, Radolf J, Zakowski P, Garratty E. Risk of acquisition of genital herpes simplex virus type 2 in sex partners of persons with genital herpes: a prospective couple study. J Infect Dis 1993;167:942-946.

4. Wald A, Zeh J, Barnum G, et al. Suppression of subclinical shedding of herpes simplex virus type 2 with acyclovir. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:8-15.

5. Stanberry LR, Spruance SL, Cunningham AL, et al. GlaxoSmithKline Herpes Vaccine Efficacy Study Group. Glycoprotein-D-adjuvant vaccine to prevent genital herpes. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1652-1661.

A colleague came into the charting area and said he thought he had just seen his first case of chancroid. He asked me if I had a moment to see the patient, a 32-year-old African American man who noted the onset of painful sores on his penis 1 week ago. The patient consented to a second opinion. On further questioning, he remembered a tingling pain that started a few days prior to the sores. When asked about any previous outbreaks, he thought he may have had something like this 1 year ago. He did not remember seeing blisters before the sores appeared.

The last time the patient had sexual relations was 2 months ago, with someone he met at a party. He claimed he used a condom. He did not have any lesions at that time and had never had a sexually transmitted disease before.

He had recently fallen in love, and was concerned about these ulcers—he did not want to give her any diseases. They had only kissed so far and he wanted to know what he should tell her. He said he had never had sex with men or injected any drugs. He has had a number of serially monogamous relationships and reported no other human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk factors.

The patient was a healthy-looking young man. Examination of his penis (Figure 1) showed the ulcers clearly visible (Figure 2). He had only shotty inguinal adenopathy that was nontender.

FIGURE 1

Painful sores on the genitals

FIGURE 2

Close-up of ulcers on the penis

What is the diagnosis?

What is the treatment and prevention strategy?

Differential diagnosis

The most likely causes of painful genital ulcers in this case are herpes simplex, chancroid, and syphilis. Granuloma inguinale and lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) are rare causes of genital ulceration in the United States. A zipper accident or other trauma can cause genital ulceration, but the patient should be able to give a clear history of such an event.

By epidemiology alone, the order of likelihood for the cause of any genital ulceration is herpes, syphilis, then chancroid.

This case points to herpes

Herpes simplex is by far the most common cause of painful genital ulcers in the United States; at least 50 million people have genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection1 The features of this case pointing to herpes are the appearance of multiple ulcers, the tingling pain that preceded the ulcers, and the history of a possible episode in the preceding year. While it would be helpful to have a history of blisters that preceded the ulcers, the evidence still points to herpes as the most likely diagnosis.

Could it be syphilis?

While the primary chancre of syphilis is classically described as painless, the patient with syphilis may experience pain. Syphilis tends to present as a single ulcer but may cause multiple ulcers.

Why not chancroid?

Chancroid may also cause multiple small painful ulcers. However, the ulcers of chancroid tend to be deeper than those of herpes and bleed more easily.

Other characteristics to look for

All of these sexually transmitted diseases can cause tender painful adenopathy, which is particularly characteristic of chancroid and LGV. Suppurative inguinal adenopathy with painful genital ulcers is almost pathognomonic of chancroid. With LGV, there may be a self-limited genital ulcer at the site of inoculation, which is often gone by the time a patient seeks care. Granuloma inguinale causes painless, progressive ulcerative lesions without regional lymphadenopathy. These lesions are highly vascular (with a characteristic beefy red appearance) and bleed easily on contact.1 While it would be helpful to have a history of blisters that preceded the ulcers, the evidence still points to herpes as the most likely diagnosis.

Laboratory examination

Herpes

All patients with genital ulcers thought to be from an STD should be tested for syphilis and HIV regardless of other risk factors.1 This patient should additionally be tested for herpes simplex. A bacteriologic test for chancroid is not necessary, but the clinician who first saw the patient asked that we conduct the test for chancroid—a culture for the Haemophilus ducreyi bacterium.

Isolation of HSV in cell culture is the preferred virologic test for patients with genital ulcers.1Unfortunately, the sensitivity of culture declines rapidly as lesions begin to heal, usually within a few days of onset. Direct fluorescent antibody tests are also available. Both herpes culture and the direct fluorescent antibody test distinguish HSV-1 from HSV-2. Polymerase chain reaction assays for HSV DNA are highly sensitive, but their role in the diagnosis of genital ulcer disease has not been well-defined.

Most cases of recurrent genital herpes are caused by HSV-2. Specific serologic testing can be expensive, and is not needed at the time of the initial virologic screening. However, consider ordering the test at a subsequent visit, because the distinction between HSV serotypes influences prognosis and counseling. Also, because false-negative HSV cultures are common—especially with recurrent infection or healing lesions—type-specific serologic tests are useful for confirming a diagnosis of genital herpes.1 Herpes serologies can also be used to help manage sexual partners of persons with genital herpes.

Syphilis

The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test should be used to detect syphilis. Both tests are used for nonspecific screening only, because they measure anticardiolipin antibodies. A positive result should be confirmed with a specific treponemal test such as a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS).

The results of these laboratory tests are not available immediately during the patient’s visit. If there was a high suspicion for syphilis, a dark field examination from the ulcer exudate could be used to look for spirochetes while the patient was still in the office. In this case, the suspicion for syphilis was low.

Treatment: Antivirals

The major question is whether the patient should be treated empirically with medication. The most likely diagnosis is herpes simplex. Randomized trials indicate that 3 antiviral medications— acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir—provide clinical benefit for genital herpes (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).1

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002 treatment guidelines for STDs recommend the following medications for the first clinical episode of genital herpes:

- Acyclovir 400 mg orally, 3 times daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved, OR

- Acyclovir 200 mg orally, 5 times daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved, OR

- Famciclovir 250 mg orally, 3 times daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved, OR

- Valacyclovir 1 g orally, twice daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved.

Topical acyclovir is less effective than the oral formulaton and its use is discouraged.

The suspicion for syphilis is too low to warrant an intramuscular shot of penicillin, which is painful and can cause anaphylaxis in some patients. The likelihood of chancroid is too low to prescribe an oral antibiotic such as erythromycin.

The patient wanted empirical treatment for herpes. He was given valacyclovir, 1 gm for 7 days, taken twice daily, with the option to call in for more if the ulcers did not resolve by day 7. He was told he might apply petrolatum and clean gauze to the ulcers to diminish the pain when open ulcers rub against underwear. Acetaminophen or other analgesics were recommended for pain, and he was advised to avoid sexual activity until the ulcers had fully healed.

Preventing transmission

The patient is appropriately concerned about the transmission of this condition to a new partner. Not having a firm diagnosis makes definitive counseling more difficult. However, general principles of safe sex and condom use were discussed. On the follow-up visit the patient was told that the result of his herpes test was positive for HSV-2. Results of his RPR, HIV antibody test, and H ducreyiculture were all negative.

Information about condom use was reinforced, and the patient was told there is definitive evidence that condom use does diminish the risk of transmission of herpes from a man to a woman (LOE=1b).2 That same study did not show that condom use prevents transmission from women to men. Also, changes in sexual behavior, correlated with counseling about avoiding sex when a partner has lesions, were associated with reduction in HSV-2 acquisition over time (LOE=1b).2

One study showed that the overall risk of genital HSV transmission in couples is low (10%/year). The risk may be significantly increased in women and in seronegative individuals.3 This speaks for serologic testing for the potential partner of this patient.

When recurrences are frequent, antiviral agents can decrease the frequency (LOE=1a).1 If this patient has frequent recurrences, antiviral agents would be appropriate and would decrease the times when the patient is shedding virus asymptomatically.

Herpes is transmitted between sexual partners during asymptomatic shedding.1 Acyclovir 400 mg twice daily can reduce asymptomatic viral shedding significantly among women with recurrent herpes simplex (LOE=1b).4 While it is likely this will decrease transmission from women to men, this has not been proven. Data on decreasing viral transmission from men to women by antiviral therapy is not available. At some point, the Glycoprotein-D-adjuvant vaccine may be an option to prevent genital herpes transmission to his partner.5

Note. The CDC 2002 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines are available for download and use on a Palm handheld computer at www.cdcnpin.org/scripts/std/pda.asp.

A colleague came into the charting area and said he thought he had just seen his first case of chancroid. He asked me if I had a moment to see the patient, a 32-year-old African American man who noted the onset of painful sores on his penis 1 week ago. The patient consented to a second opinion. On further questioning, he remembered a tingling pain that started a few days prior to the sores. When asked about any previous outbreaks, he thought he may have had something like this 1 year ago. He did not remember seeing blisters before the sores appeared.

The last time the patient had sexual relations was 2 months ago, with someone he met at a party. He claimed he used a condom. He did not have any lesions at that time and had never had a sexually transmitted disease before.

He had recently fallen in love, and was concerned about these ulcers—he did not want to give her any diseases. They had only kissed so far and he wanted to know what he should tell her. He said he had never had sex with men or injected any drugs. He has had a number of serially monogamous relationships and reported no other human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk factors.

The patient was a healthy-looking young man. Examination of his penis (Figure 1) showed the ulcers clearly visible (Figure 2). He had only shotty inguinal adenopathy that was nontender.

FIGURE 1

Painful sores on the genitals

FIGURE 2

Close-up of ulcers on the penis

What is the diagnosis?

What is the treatment and prevention strategy?

Differential diagnosis

The most likely causes of painful genital ulcers in this case are herpes simplex, chancroid, and syphilis. Granuloma inguinale and lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) are rare causes of genital ulceration in the United States. A zipper accident or other trauma can cause genital ulceration, but the patient should be able to give a clear history of such an event.

By epidemiology alone, the order of likelihood for the cause of any genital ulceration is herpes, syphilis, then chancroid.

This case points to herpes

Herpes simplex is by far the most common cause of painful genital ulcers in the United States; at least 50 million people have genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection1 The features of this case pointing to herpes are the appearance of multiple ulcers, the tingling pain that preceded the ulcers, and the history of a possible episode in the preceding year. While it would be helpful to have a history of blisters that preceded the ulcers, the evidence still points to herpes as the most likely diagnosis.

Could it be syphilis?

While the primary chancre of syphilis is classically described as painless, the patient with syphilis may experience pain. Syphilis tends to present as a single ulcer but may cause multiple ulcers.

Why not chancroid?

Chancroid may also cause multiple small painful ulcers. However, the ulcers of chancroid tend to be deeper than those of herpes and bleed more easily.

Other characteristics to look for

All of these sexually transmitted diseases can cause tender painful adenopathy, which is particularly characteristic of chancroid and LGV. Suppurative inguinal adenopathy with painful genital ulcers is almost pathognomonic of chancroid. With LGV, there may be a self-limited genital ulcer at the site of inoculation, which is often gone by the time a patient seeks care. Granuloma inguinale causes painless, progressive ulcerative lesions without regional lymphadenopathy. These lesions are highly vascular (with a characteristic beefy red appearance) and bleed easily on contact.1 While it would be helpful to have a history of blisters that preceded the ulcers, the evidence still points to herpes as the most likely diagnosis.

Laboratory examination

Herpes

All patients with genital ulcers thought to be from an STD should be tested for syphilis and HIV regardless of other risk factors.1 This patient should additionally be tested for herpes simplex. A bacteriologic test for chancroid is not necessary, but the clinician who first saw the patient asked that we conduct the test for chancroid—a culture for the Haemophilus ducreyi bacterium.

Isolation of HSV in cell culture is the preferred virologic test for patients with genital ulcers.1Unfortunately, the sensitivity of culture declines rapidly as lesions begin to heal, usually within a few days of onset. Direct fluorescent antibody tests are also available. Both herpes culture and the direct fluorescent antibody test distinguish HSV-1 from HSV-2. Polymerase chain reaction assays for HSV DNA are highly sensitive, but their role in the diagnosis of genital ulcer disease has not been well-defined.

Most cases of recurrent genital herpes are caused by HSV-2. Specific serologic testing can be expensive, and is not needed at the time of the initial virologic screening. However, consider ordering the test at a subsequent visit, because the distinction between HSV serotypes influences prognosis and counseling. Also, because false-negative HSV cultures are common—especially with recurrent infection or healing lesions—type-specific serologic tests are useful for confirming a diagnosis of genital herpes.1 Herpes serologies can also be used to help manage sexual partners of persons with genital herpes.

Syphilis

The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test should be used to detect syphilis. Both tests are used for nonspecific screening only, because they measure anticardiolipin antibodies. A positive result should be confirmed with a specific treponemal test such as a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS).

The results of these laboratory tests are not available immediately during the patient’s visit. If there was a high suspicion for syphilis, a dark field examination from the ulcer exudate could be used to look for spirochetes while the patient was still in the office. In this case, the suspicion for syphilis was low.

Treatment: Antivirals

The major question is whether the patient should be treated empirically with medication. The most likely diagnosis is herpes simplex. Randomized trials indicate that 3 antiviral medications— acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir—provide clinical benefit for genital herpes (level of evidence [LOE]=1a).1

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002 treatment guidelines for STDs recommend the following medications for the first clinical episode of genital herpes:

- Acyclovir 400 mg orally, 3 times daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved, OR

- Acyclovir 200 mg orally, 5 times daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved, OR

- Famciclovir 250 mg orally, 3 times daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved, OR

- Valacyclovir 1 g orally, twice daily for 7–10 days or until clinically resolved.

Topical acyclovir is less effective than the oral formulaton and its use is discouraged.

The suspicion for syphilis is too low to warrant an intramuscular shot of penicillin, which is painful and can cause anaphylaxis in some patients. The likelihood of chancroid is too low to prescribe an oral antibiotic such as erythromycin.

The patient wanted empirical treatment for herpes. He was given valacyclovir, 1 gm for 7 days, taken twice daily, with the option to call in for more if the ulcers did not resolve by day 7. He was told he might apply petrolatum and clean gauze to the ulcers to diminish the pain when open ulcers rub against underwear. Acetaminophen or other analgesics were recommended for pain, and he was advised to avoid sexual activity until the ulcers had fully healed.

Preventing transmission

The patient is appropriately concerned about the transmission of this condition to a new partner. Not having a firm diagnosis makes definitive counseling more difficult. However, general principles of safe sex and condom use were discussed. On the follow-up visit the patient was told that the result of his herpes test was positive for HSV-2. Results of his RPR, HIV antibody test, and H ducreyiculture were all negative.