User login

Blisters during pregnancy—just with the second husband

A 33-year-old Hispanic woman who was 5 months pregnant came to the hospital complaining of nausea and vomiting. She had a history of anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, diagnosed originally in 1993 after 2 spontaneous abortions. She had stopped taking warfarin (Coumadin) at the start of her pregnancy, and had been taking heparin for 3 months.

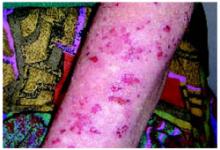

After 4 days of close monitoring, the patient had labor induced for severe life-threatening pre-eclampsia. One day after induction and delivery of a stillborn fetus, she began to develop painful swelling of both hands and feet along with targetoid, urticarial, edematous, deep pink, slightly dusky papules and plaques on her hands, abdomen, lower extremities, and proximal thighs. Some of the edematous sites began to form vesicles and bullae (FIGURE 1 AND 2). When asked about this eruption, the patient mentioned having a similar rash after delivery of one of her children about 10 years before.

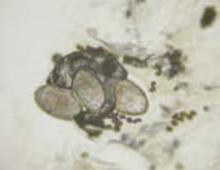

Interestingly, she noted that she only experienced these cutaneous findings during pregnancies with her second husband and not with her first. Biopsies were performed and showed prominent eosinophils in the dermis and a subepidermal vesicle (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 1

Blisters on the wrist…

FIGURE 2

…and the abdomen

FIGURE 3

Biopsy results

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Pemphigoid gestationis

The patient had pemphigoid gestationis, also known as herpes gestationis, a rare autoimmune bullous disease of pregnancy and the puerperium.1 Clinically and immunopathologically, pemphigoid gestationis is related to the pemphigoid group of disorders and is not virally mediated.2

In the United States, pemphigoid gestationis has an incidence of 1:10,000 to 1:50,000 pregnancies.3 Clinically, it manifests during the second or third trimester, with a sudden onset of extremely pruritic urticarial papules and plaques usually located around the umbilicus. These lesions often progress to tense vesicles and blisters and spread peripherally to the trunk, often sparing the face, palms, and soles.4 Worsening of the lesions at the time of delivery occurs in 75% of cases, and usually recurs with subsequent pregnancies.5 Occasionally, however, subsequent pregnancies are unaffected, so-called “skip pregnancies.”6 This occurs most often when there has been a change in paternity.7

The exact cause of pemphigoid gestationis is unknown. Investigative efforts lead to the identification of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibody, which binds to bullous pemphigoid (BP) antigen 2, also called BP180, which is a protein associated with hemidesmosomes of basal keratinocytes.8-10 These hemidesmosomes form the central portion of the dermalepidermal anchoring complex, whose function is to establish a connection between the basal keratinocytes and the upper dermis.11,12 This is critical for maintaining dermal-epidermal adhesion. It is hypothesized that binding of autoantibodies to BP180 initiates an inflammatory reaction, leading to blister formation at the dermal-epidermal junction.13

Pathology and immunology

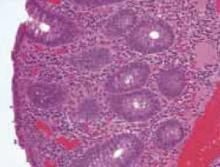

Histopathologic findings demonstrate subepidermal vesicles, spongiosis, and perivascular lymphocyte, and histiocyte infiltrates with a preponderance of eosinophils.3 The sine qua non of the disease, though, is the demonstration through direct immunofluorescence of complement deposition and IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane.14

There appears to be a genetic predisposition toward the development of pemphigoid gestationis. Associations with human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) DR3 (61%–85%), DR4 (52%), or both (43%–50%) have been reported.3,15,16 Interestingly, 85% of persons with a history of pemphigoid gestationis were found to have anti-HLA antibodies, some of which were directed against paternal HLAs expressed in their placentae.17 These findings raised speculation about a possible immunologic insult against placental antigens during pregnancy. Evidence suggests that circulating autoantibodies in patients with pemphigoid gestationis bind to the dermal-epidermal junction of skin and amnion in which BP180 antigen is also present.18-20

It has been demonstrated that in patients with pemphigoid gestationis the cells of the placenta stroma express abnormal major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules.21,22 This lead to the proposition of 2 possible mechanisms for the initiation of an autoimmune response in pemphigoid gestationis. The first proposes that placental BP180 is presented to the maternal immune system in association with abnormal MHC molecules, which then trigger the production of autoantibodies that cross-react with the skin. Alternatively, the placental stromal cells may evoke an allogeneic reaction against the BP180 antigen presented by paternal MHC molecules of the placental stroma, which then cross-reacts with the skin.23 The latter theory supports the findings in this patient, who developed pemphigoid gestationis during the 2 pregnancies with her second husband and not during the pregnancies with her first husband.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to differentiate the prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis from other pregnancy-related dermatoses. These include polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), erythema multiforme, prurigo annularis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and impetigo herpetiformis. Impetigo herpetiformis is not related to bacterial or viral causes, but is rather a manifestation of pustular psoriasis during pregnancy. The target lesions that form in pemphigoid gestationis look just like the target lesions of erythema multiforme.

When there is no blister formation, it is impossible to distinguish pemphigoid gestationis from many of the other cutaneous eruptions of pregnancy. If uncertain, the clinician should perform punch biopsies of the involved skin, with one specimen sent for immunofluoresence studies. The biopsy should not pass directly through a bullae, due to risk of losing the overlying epidermis in the specimen. Do the punch biopsy at the edge of the bulla including some normal skin. Other important laboratory exams to perform would include liver function tests to look for an upward trend associated with intrahepatic cholestasis, and herpes simplex virus antibody testing for the association with erythema multiforme. The cutaneous findings and pertinent tests are listed in the table below in order of increasing potential as a life-threatening dermatosis (TABLE).

TABLE

Differential diagnosis for blisters in pregnancy

| DISEASE | ASSOCIATIONS | DIAGNOSIS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphous eruption of pregnancy | Nonspecific pruritic eruption of pregnancy | Biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis | Mild to mid-potency topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy | Occur in stretch marks, spare umbilicus; more often in primigravidas | Unless history is very clear, biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis | Emollients, pulse-dye laser during violaceous stage of striae, topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Erythema multiforme | Can involve mucous membranes, targetoid lesions, absence of pruritus, centripetal spread, favors palms/soles | Viral, bacterial, or drug-related eruption. Most often with herpes simplex I or II virus. Biopsy to differentiate from pemphigoid gestationis | Acyclovir, valacyclovir if HSV-related, treatment of bacterial infection, or removal of offending drug |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Blistering, urticarial papules/plaques, pruritus | Biopsy sent for histologic diagnosis and immunofluorescence | Prednisone for short course starting at 1 mg/kg, then tapering over 2–3 months, topical steroids |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | +/- jaundice, otherwise no cutaneous findings other than generalized pruritus, risk of preterm birth | Elevation in liver function tests, cholesterol, triglycerides, dark urine, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, greasy stools | Ursodeoxycholic acid, S-adenosyl-L-methionine |

| Impetigo herpetiformis (pustular psoriasis of pregnancy) | Extremely ill with fever, chills, nausea, vascular instability, pustules rather than vesicles | Biopsy if uncertain, pustules sterile, risk of hypocalcemia, hypoparathyroidism | High dose oral steroids or cyclosporine |

Treatment

Pemphigoid gestationis should resolve spontaneously within 2 to 3 months of delivery. Treatment is aimed at preventing new blisters and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines in mild cases.2,25 In advanced lesions as seen in this case, 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg of prednisolone daily is usually sufficient.3,25 Alternative medications include sulfapyridine, dapsone, and cyclosporine, though disease response is variable and their safety is questionable.3

When the skin condition began, the patient was treated with oral antihistamines and topical steroids. On day 2, the diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis was clear, and she was started on oral prednisone at 60 mg/d, which resulted in rapid symptom improvement in her lesions and swelling. New lesions stopped forming, and systemic steroids were tapered off over the 3 months after delivery. The skin lesions healed and she was given supportive counseling to help her cope with her pregnancy loss.

Conclusion

We have described a rare case of a patient with no cutaneous eruptions during her pregnancies with her first husband, who developed pemphigoid gestationis in 2 pregnancies with her second husband. While it is interesting that our patient also had the anticardiolipin syndrome, most patients do not have both conditions.

Our patient had the classic findings of pemphigoid gestationis with many characteristic lesions (including the umbilicus) making the diagnosis possible before biopsy confirmation. This was fortunate for her because her painful swelling responded quickly to the corticosteroids. When cases are less clinically obvious, biopsy for histopathology and immunofluorescence facilitates differentiation of pemphigoid gestationis from other dermatoses of pregnancy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Coupe RL. Herpes gestationis. Arch Dermatol 1965;91:633-636.

2. Jenkins RE, Hern S, Black MM. Clinical features and management of 87 patients with pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:255-259.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (Pemphigoid gestationis). Clinics Dermatology 2006;24:109-112.

4. Shornick JK. Herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:539-556.

5. Holmes RC, Black MM, Dann J, et al. A comparative study of toxic erythema of pregnancy and herpes gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1982;106:499-510.

6. Cozzani E, Basso M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Pemphigoid gestationis post partum after changing husband. Intn J Dermatol 2005;44:1057-1058.

7. Shornick JK, Black MM. Fetal risks in herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26:63-68.

8. Diaz LA, Ratrie H, III, Saunders WS, et al. Isolation of a human epidermal cDNA corresponding to the 180-kD autoantigen recognized by bullous pemphigoid and herpes gestationis sera. Immunolocalization of this protein to the hemidesmosome. J Clin Invest 1990;86:1088-1094.

9. Giudice GJ, Emery DJ, Diaz LA. Cloning and primary structural analysis of the bullous pemphigoid autoantigen BP180. J Invest Dermatol 1992;99:243-250.

10. Zillikens D, Giudice GJ. BP180/typeXVIII collagen: its role in acquired and inherited disorders of the dermal-epidermal junction. Arch Dermatol Res 1999;291:187-194.

11. Borradori L, Sonnenberg A. Hemidesmosomes: roles in adhesion, signaling and human diseases. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1996;8:647-656.

12. Zillikens D. Acquired skin disease of hemidesmosomes. J Dermatol Sci 1999;20:134-154.

13. Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Autoimmune and inherited subepidermal blistering diseases: advances in the clinic and the laboratory. Adv Dermatol 2000;16:113-157.

14. Shornick JD. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1998;17:172-181.

15. Holmes RC, Black MM, Jurecka W, et al. Clues to the aetiology and pathogenesis of herpes gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1983;109:131-139.

16. Shornick JK, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. High frequency of histocompatibility antigens DR3 and DR4 in herpes gestationis. J Clin Invest 1981;68:553-555.

17. Shornick JK, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Paternal histocompatibility (HLA) antigens and maternal anti-HLA antibodies in herpes gestationis. J Invest Dermatol 1983;81:407-409.

18. Ortonne JP, Hsi BL, Verrando P, et al. Herpes gestationis factor reacts with the amniotic epithelial basement membrane. Br J Dermatol 1987;117:147-154.

19. Kelly SE, Bhogal BS, Wojnarowska F, Black MM. Expression of a pemphigoid gestationis-related antigen by human placenta. Br J Dermatol 1988;118:605-611.

20. Fairley JA, Heintz PW, Neuburg M, et al. Expression pattern of the bullous pemphigoid-180 antigen in normal and neoplastic epithelia. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:385-391.

21. Kelly SE, Black MM, Fleming S. Antigen-presenting cells in the skin and placenta in pemphigoid gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1990;122:593-599.

22. Borthwick GM, Holmes RC, Stirrat GM. Abnormal expression of class II MHC antigens in placentae from patients with pemphigoid gestationis. Placenta 1988;9:81-94.

23. Kelly SE, Black MM, Fleming S. Pemphigoid gestationis: a unique mechanism of initiation of an autoimmune response by MHC class II molecules. J Pathol 1989;158:81-82.

24. Borradori L, Saurat JH. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy. Toward a comprehensive view. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:778-780.

25. Shimanovich I, Bröcker EB, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: new insights into the pathogenesis lead to novel diagnostic tools. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;109:970-976.

A 33-year-old Hispanic woman who was 5 months pregnant came to the hospital complaining of nausea and vomiting. She had a history of anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, diagnosed originally in 1993 after 2 spontaneous abortions. She had stopped taking warfarin (Coumadin) at the start of her pregnancy, and had been taking heparin for 3 months.

After 4 days of close monitoring, the patient had labor induced for severe life-threatening pre-eclampsia. One day after induction and delivery of a stillborn fetus, she began to develop painful swelling of both hands and feet along with targetoid, urticarial, edematous, deep pink, slightly dusky papules and plaques on her hands, abdomen, lower extremities, and proximal thighs. Some of the edematous sites began to form vesicles and bullae (FIGURE 1 AND 2). When asked about this eruption, the patient mentioned having a similar rash after delivery of one of her children about 10 years before.

Interestingly, she noted that she only experienced these cutaneous findings during pregnancies with her second husband and not with her first. Biopsies were performed and showed prominent eosinophils in the dermis and a subepidermal vesicle (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 1

Blisters on the wrist…

FIGURE 2

…and the abdomen

FIGURE 3

Biopsy results

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Pemphigoid gestationis

The patient had pemphigoid gestationis, also known as herpes gestationis, a rare autoimmune bullous disease of pregnancy and the puerperium.1 Clinically and immunopathologically, pemphigoid gestationis is related to the pemphigoid group of disorders and is not virally mediated.2

In the United States, pemphigoid gestationis has an incidence of 1:10,000 to 1:50,000 pregnancies.3 Clinically, it manifests during the second or third trimester, with a sudden onset of extremely pruritic urticarial papules and plaques usually located around the umbilicus. These lesions often progress to tense vesicles and blisters and spread peripherally to the trunk, often sparing the face, palms, and soles.4 Worsening of the lesions at the time of delivery occurs in 75% of cases, and usually recurs with subsequent pregnancies.5 Occasionally, however, subsequent pregnancies are unaffected, so-called “skip pregnancies.”6 This occurs most often when there has been a change in paternity.7

The exact cause of pemphigoid gestationis is unknown. Investigative efforts lead to the identification of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibody, which binds to bullous pemphigoid (BP) antigen 2, also called BP180, which is a protein associated with hemidesmosomes of basal keratinocytes.8-10 These hemidesmosomes form the central portion of the dermalepidermal anchoring complex, whose function is to establish a connection between the basal keratinocytes and the upper dermis.11,12 This is critical for maintaining dermal-epidermal adhesion. It is hypothesized that binding of autoantibodies to BP180 initiates an inflammatory reaction, leading to blister formation at the dermal-epidermal junction.13

Pathology and immunology

Histopathologic findings demonstrate subepidermal vesicles, spongiosis, and perivascular lymphocyte, and histiocyte infiltrates with a preponderance of eosinophils.3 The sine qua non of the disease, though, is the demonstration through direct immunofluorescence of complement deposition and IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane.14

There appears to be a genetic predisposition toward the development of pemphigoid gestationis. Associations with human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) DR3 (61%–85%), DR4 (52%), or both (43%–50%) have been reported.3,15,16 Interestingly, 85% of persons with a history of pemphigoid gestationis were found to have anti-HLA antibodies, some of which were directed against paternal HLAs expressed in their placentae.17 These findings raised speculation about a possible immunologic insult against placental antigens during pregnancy. Evidence suggests that circulating autoantibodies in patients with pemphigoid gestationis bind to the dermal-epidermal junction of skin and amnion in which BP180 antigen is also present.18-20

It has been demonstrated that in patients with pemphigoid gestationis the cells of the placenta stroma express abnormal major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules.21,22 This lead to the proposition of 2 possible mechanisms for the initiation of an autoimmune response in pemphigoid gestationis. The first proposes that placental BP180 is presented to the maternal immune system in association with abnormal MHC molecules, which then trigger the production of autoantibodies that cross-react with the skin. Alternatively, the placental stromal cells may evoke an allogeneic reaction against the BP180 antigen presented by paternal MHC molecules of the placental stroma, which then cross-reacts with the skin.23 The latter theory supports the findings in this patient, who developed pemphigoid gestationis during the 2 pregnancies with her second husband and not during the pregnancies with her first husband.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to differentiate the prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis from other pregnancy-related dermatoses. These include polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), erythema multiforme, prurigo annularis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and impetigo herpetiformis. Impetigo herpetiformis is not related to bacterial or viral causes, but is rather a manifestation of pustular psoriasis during pregnancy. The target lesions that form in pemphigoid gestationis look just like the target lesions of erythema multiforme.

When there is no blister formation, it is impossible to distinguish pemphigoid gestationis from many of the other cutaneous eruptions of pregnancy. If uncertain, the clinician should perform punch biopsies of the involved skin, with one specimen sent for immunofluoresence studies. The biopsy should not pass directly through a bullae, due to risk of losing the overlying epidermis in the specimen. Do the punch biopsy at the edge of the bulla including some normal skin. Other important laboratory exams to perform would include liver function tests to look for an upward trend associated with intrahepatic cholestasis, and herpes simplex virus antibody testing for the association with erythema multiforme. The cutaneous findings and pertinent tests are listed in the table below in order of increasing potential as a life-threatening dermatosis (TABLE).

TABLE

Differential diagnosis for blisters in pregnancy

| DISEASE | ASSOCIATIONS | DIAGNOSIS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphous eruption of pregnancy | Nonspecific pruritic eruption of pregnancy | Biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis | Mild to mid-potency topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy | Occur in stretch marks, spare umbilicus; more often in primigravidas | Unless history is very clear, biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis | Emollients, pulse-dye laser during violaceous stage of striae, topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Erythema multiforme | Can involve mucous membranes, targetoid lesions, absence of pruritus, centripetal spread, favors palms/soles | Viral, bacterial, or drug-related eruption. Most often with herpes simplex I or II virus. Biopsy to differentiate from pemphigoid gestationis | Acyclovir, valacyclovir if HSV-related, treatment of bacterial infection, or removal of offending drug |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Blistering, urticarial papules/plaques, pruritus | Biopsy sent for histologic diagnosis and immunofluorescence | Prednisone for short course starting at 1 mg/kg, then tapering over 2–3 months, topical steroids |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | +/- jaundice, otherwise no cutaneous findings other than generalized pruritus, risk of preterm birth | Elevation in liver function tests, cholesterol, triglycerides, dark urine, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, greasy stools | Ursodeoxycholic acid, S-adenosyl-L-methionine |

| Impetigo herpetiformis (pustular psoriasis of pregnancy) | Extremely ill with fever, chills, nausea, vascular instability, pustules rather than vesicles | Biopsy if uncertain, pustules sterile, risk of hypocalcemia, hypoparathyroidism | High dose oral steroids or cyclosporine |

Treatment

Pemphigoid gestationis should resolve spontaneously within 2 to 3 months of delivery. Treatment is aimed at preventing new blisters and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines in mild cases.2,25 In advanced lesions as seen in this case, 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg of prednisolone daily is usually sufficient.3,25 Alternative medications include sulfapyridine, dapsone, and cyclosporine, though disease response is variable and their safety is questionable.3

When the skin condition began, the patient was treated with oral antihistamines and topical steroids. On day 2, the diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis was clear, and she was started on oral prednisone at 60 mg/d, which resulted in rapid symptom improvement in her lesions and swelling. New lesions stopped forming, and systemic steroids were tapered off over the 3 months after delivery. The skin lesions healed and she was given supportive counseling to help her cope with her pregnancy loss.

Conclusion

We have described a rare case of a patient with no cutaneous eruptions during her pregnancies with her first husband, who developed pemphigoid gestationis in 2 pregnancies with her second husband. While it is interesting that our patient also had the anticardiolipin syndrome, most patients do not have both conditions.

Our patient had the classic findings of pemphigoid gestationis with many characteristic lesions (including the umbilicus) making the diagnosis possible before biopsy confirmation. This was fortunate for her because her painful swelling responded quickly to the corticosteroids. When cases are less clinically obvious, biopsy for histopathology and immunofluorescence facilitates differentiation of pemphigoid gestationis from other dermatoses of pregnancy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

A 33-year-old Hispanic woman who was 5 months pregnant came to the hospital complaining of nausea and vomiting. She had a history of anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, diagnosed originally in 1993 after 2 spontaneous abortions. She had stopped taking warfarin (Coumadin) at the start of her pregnancy, and had been taking heparin for 3 months.

After 4 days of close monitoring, the patient had labor induced for severe life-threatening pre-eclampsia. One day after induction and delivery of a stillborn fetus, she began to develop painful swelling of both hands and feet along with targetoid, urticarial, edematous, deep pink, slightly dusky papules and plaques on her hands, abdomen, lower extremities, and proximal thighs. Some of the edematous sites began to form vesicles and bullae (FIGURE 1 AND 2). When asked about this eruption, the patient mentioned having a similar rash after delivery of one of her children about 10 years before.

Interestingly, she noted that she only experienced these cutaneous findings during pregnancies with her second husband and not with her first. Biopsies were performed and showed prominent eosinophils in the dermis and a subepidermal vesicle (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 1

Blisters on the wrist…

FIGURE 2

…and the abdomen

FIGURE 3

Biopsy results

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Pemphigoid gestationis

The patient had pemphigoid gestationis, also known as herpes gestationis, a rare autoimmune bullous disease of pregnancy and the puerperium.1 Clinically and immunopathologically, pemphigoid gestationis is related to the pemphigoid group of disorders and is not virally mediated.2

In the United States, pemphigoid gestationis has an incidence of 1:10,000 to 1:50,000 pregnancies.3 Clinically, it manifests during the second or third trimester, with a sudden onset of extremely pruritic urticarial papules and plaques usually located around the umbilicus. These lesions often progress to tense vesicles and blisters and spread peripherally to the trunk, often sparing the face, palms, and soles.4 Worsening of the lesions at the time of delivery occurs in 75% of cases, and usually recurs with subsequent pregnancies.5 Occasionally, however, subsequent pregnancies are unaffected, so-called “skip pregnancies.”6 This occurs most often when there has been a change in paternity.7

The exact cause of pemphigoid gestationis is unknown. Investigative efforts lead to the identification of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibody, which binds to bullous pemphigoid (BP) antigen 2, also called BP180, which is a protein associated with hemidesmosomes of basal keratinocytes.8-10 These hemidesmosomes form the central portion of the dermalepidermal anchoring complex, whose function is to establish a connection between the basal keratinocytes and the upper dermis.11,12 This is critical for maintaining dermal-epidermal adhesion. It is hypothesized that binding of autoantibodies to BP180 initiates an inflammatory reaction, leading to blister formation at the dermal-epidermal junction.13

Pathology and immunology

Histopathologic findings demonstrate subepidermal vesicles, spongiosis, and perivascular lymphocyte, and histiocyte infiltrates with a preponderance of eosinophils.3 The sine qua non of the disease, though, is the demonstration through direct immunofluorescence of complement deposition and IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane.14

There appears to be a genetic predisposition toward the development of pemphigoid gestationis. Associations with human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) DR3 (61%–85%), DR4 (52%), or both (43%–50%) have been reported.3,15,16 Interestingly, 85% of persons with a history of pemphigoid gestationis were found to have anti-HLA antibodies, some of which were directed against paternal HLAs expressed in their placentae.17 These findings raised speculation about a possible immunologic insult against placental antigens during pregnancy. Evidence suggests that circulating autoantibodies in patients with pemphigoid gestationis bind to the dermal-epidermal junction of skin and amnion in which BP180 antigen is also present.18-20

It has been demonstrated that in patients with pemphigoid gestationis the cells of the placenta stroma express abnormal major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules.21,22 This lead to the proposition of 2 possible mechanisms for the initiation of an autoimmune response in pemphigoid gestationis. The first proposes that placental BP180 is presented to the maternal immune system in association with abnormal MHC molecules, which then trigger the production of autoantibodies that cross-react with the skin. Alternatively, the placental stromal cells may evoke an allogeneic reaction against the BP180 antigen presented by paternal MHC molecules of the placental stroma, which then cross-reacts with the skin.23 The latter theory supports the findings in this patient, who developed pemphigoid gestationis during the 2 pregnancies with her second husband and not during the pregnancies with her first husband.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to differentiate the prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis from other pregnancy-related dermatoses. These include polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), erythema multiforme, prurigo annularis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and impetigo herpetiformis. Impetigo herpetiformis is not related to bacterial or viral causes, but is rather a manifestation of pustular psoriasis during pregnancy. The target lesions that form in pemphigoid gestationis look just like the target lesions of erythema multiforme.

When there is no blister formation, it is impossible to distinguish pemphigoid gestationis from many of the other cutaneous eruptions of pregnancy. If uncertain, the clinician should perform punch biopsies of the involved skin, with one specimen sent for immunofluoresence studies. The biopsy should not pass directly through a bullae, due to risk of losing the overlying epidermis in the specimen. Do the punch biopsy at the edge of the bulla including some normal skin. Other important laboratory exams to perform would include liver function tests to look for an upward trend associated with intrahepatic cholestasis, and herpes simplex virus antibody testing for the association with erythema multiforme. The cutaneous findings and pertinent tests are listed in the table below in order of increasing potential as a life-threatening dermatosis (TABLE).

TABLE

Differential diagnosis for blisters in pregnancy

| DISEASE | ASSOCIATIONS | DIAGNOSIS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphous eruption of pregnancy | Nonspecific pruritic eruption of pregnancy | Biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis | Mild to mid-potency topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy | Occur in stretch marks, spare umbilicus; more often in primigravidas | Unless history is very clear, biopsy to differentiate from prebullous stage of pemphigoid gestationis | Emollients, pulse-dye laser during violaceous stage of striae, topical steroids, oral antihistamines |

| Erythema multiforme | Can involve mucous membranes, targetoid lesions, absence of pruritus, centripetal spread, favors palms/soles | Viral, bacterial, or drug-related eruption. Most often with herpes simplex I or II virus. Biopsy to differentiate from pemphigoid gestationis | Acyclovir, valacyclovir if HSV-related, treatment of bacterial infection, or removal of offending drug |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Blistering, urticarial papules/plaques, pruritus | Biopsy sent for histologic diagnosis and immunofluorescence | Prednisone for short course starting at 1 mg/kg, then tapering over 2–3 months, topical steroids |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | +/- jaundice, otherwise no cutaneous findings other than generalized pruritus, risk of preterm birth | Elevation in liver function tests, cholesterol, triglycerides, dark urine, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, greasy stools | Ursodeoxycholic acid, S-adenosyl-L-methionine |

| Impetigo herpetiformis (pustular psoriasis of pregnancy) | Extremely ill with fever, chills, nausea, vascular instability, pustules rather than vesicles | Biopsy if uncertain, pustules sterile, risk of hypocalcemia, hypoparathyroidism | High dose oral steroids or cyclosporine |

Treatment

Pemphigoid gestationis should resolve spontaneously within 2 to 3 months of delivery. Treatment is aimed at preventing new blisters and relieving pruritus, with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines in mild cases.2,25 In advanced lesions as seen in this case, 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg of prednisolone daily is usually sufficient.3,25 Alternative medications include sulfapyridine, dapsone, and cyclosporine, though disease response is variable and their safety is questionable.3

When the skin condition began, the patient was treated with oral antihistamines and topical steroids. On day 2, the diagnosis of pemphigoid gestationis was clear, and she was started on oral prednisone at 60 mg/d, which resulted in rapid symptom improvement in her lesions and swelling. New lesions stopped forming, and systemic steroids were tapered off over the 3 months after delivery. The skin lesions healed and she was given supportive counseling to help her cope with her pregnancy loss.

Conclusion

We have described a rare case of a patient with no cutaneous eruptions during her pregnancies with her first husband, who developed pemphigoid gestationis in 2 pregnancies with her second husband. While it is interesting that our patient also had the anticardiolipin syndrome, most patients do not have both conditions.

Our patient had the classic findings of pemphigoid gestationis with many characteristic lesions (including the umbilicus) making the diagnosis possible before biopsy confirmation. This was fortunate for her because her painful swelling responded quickly to the corticosteroids. When cases are less clinically obvious, biopsy for histopathology and immunofluorescence facilitates differentiation of pemphigoid gestationis from other dermatoses of pregnancy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Coupe RL. Herpes gestationis. Arch Dermatol 1965;91:633-636.

2. Jenkins RE, Hern S, Black MM. Clinical features and management of 87 patients with pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:255-259.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (Pemphigoid gestationis). Clinics Dermatology 2006;24:109-112.

4. Shornick JK. Herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:539-556.

5. Holmes RC, Black MM, Dann J, et al. A comparative study of toxic erythema of pregnancy and herpes gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1982;106:499-510.

6. Cozzani E, Basso M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Pemphigoid gestationis post partum after changing husband. Intn J Dermatol 2005;44:1057-1058.

7. Shornick JK, Black MM. Fetal risks in herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26:63-68.

8. Diaz LA, Ratrie H, III, Saunders WS, et al. Isolation of a human epidermal cDNA corresponding to the 180-kD autoantigen recognized by bullous pemphigoid and herpes gestationis sera. Immunolocalization of this protein to the hemidesmosome. J Clin Invest 1990;86:1088-1094.

9. Giudice GJ, Emery DJ, Diaz LA. Cloning and primary structural analysis of the bullous pemphigoid autoantigen BP180. J Invest Dermatol 1992;99:243-250.

10. Zillikens D, Giudice GJ. BP180/typeXVIII collagen: its role in acquired and inherited disorders of the dermal-epidermal junction. Arch Dermatol Res 1999;291:187-194.

11. Borradori L, Sonnenberg A. Hemidesmosomes: roles in adhesion, signaling and human diseases. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1996;8:647-656.

12. Zillikens D. Acquired skin disease of hemidesmosomes. J Dermatol Sci 1999;20:134-154.

13. Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Autoimmune and inherited subepidermal blistering diseases: advances in the clinic and the laboratory. Adv Dermatol 2000;16:113-157.

14. Shornick JD. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1998;17:172-181.

15. Holmes RC, Black MM, Jurecka W, et al. Clues to the aetiology and pathogenesis of herpes gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1983;109:131-139.

16. Shornick JK, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. High frequency of histocompatibility antigens DR3 and DR4 in herpes gestationis. J Clin Invest 1981;68:553-555.

17. Shornick JK, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Paternal histocompatibility (HLA) antigens and maternal anti-HLA antibodies in herpes gestationis. J Invest Dermatol 1983;81:407-409.

18. Ortonne JP, Hsi BL, Verrando P, et al. Herpes gestationis factor reacts with the amniotic epithelial basement membrane. Br J Dermatol 1987;117:147-154.

19. Kelly SE, Bhogal BS, Wojnarowska F, Black MM. Expression of a pemphigoid gestationis-related antigen by human placenta. Br J Dermatol 1988;118:605-611.

20. Fairley JA, Heintz PW, Neuburg M, et al. Expression pattern of the bullous pemphigoid-180 antigen in normal and neoplastic epithelia. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:385-391.

21. Kelly SE, Black MM, Fleming S. Antigen-presenting cells in the skin and placenta in pemphigoid gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1990;122:593-599.

22. Borthwick GM, Holmes RC, Stirrat GM. Abnormal expression of class II MHC antigens in placentae from patients with pemphigoid gestationis. Placenta 1988;9:81-94.

23. Kelly SE, Black MM, Fleming S. Pemphigoid gestationis: a unique mechanism of initiation of an autoimmune response by MHC class II molecules. J Pathol 1989;158:81-82.

24. Borradori L, Saurat JH. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy. Toward a comprehensive view. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:778-780.

25. Shimanovich I, Bröcker EB, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: new insights into the pathogenesis lead to novel diagnostic tools. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;109:970-976.

1. Coupe RL. Herpes gestationis. Arch Dermatol 1965;91:633-636.

2. Jenkins RE, Hern S, Black MM. Clinical features and management of 87 patients with pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:255-259.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (Pemphigoid gestationis). Clinics Dermatology 2006;24:109-112.

4. Shornick JK. Herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:539-556.

5. Holmes RC, Black MM, Dann J, et al. A comparative study of toxic erythema of pregnancy and herpes gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1982;106:499-510.

6. Cozzani E, Basso M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Pemphigoid gestationis post partum after changing husband. Intn J Dermatol 2005;44:1057-1058.

7. Shornick JK, Black MM. Fetal risks in herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26:63-68.

8. Diaz LA, Ratrie H, III, Saunders WS, et al. Isolation of a human epidermal cDNA corresponding to the 180-kD autoantigen recognized by bullous pemphigoid and herpes gestationis sera. Immunolocalization of this protein to the hemidesmosome. J Clin Invest 1990;86:1088-1094.

9. Giudice GJ, Emery DJ, Diaz LA. Cloning and primary structural analysis of the bullous pemphigoid autoantigen BP180. J Invest Dermatol 1992;99:243-250.

10. Zillikens D, Giudice GJ. BP180/typeXVIII collagen: its role in acquired and inherited disorders of the dermal-epidermal junction. Arch Dermatol Res 1999;291:187-194.

11. Borradori L, Sonnenberg A. Hemidesmosomes: roles in adhesion, signaling and human diseases. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1996;8:647-656.

12. Zillikens D. Acquired skin disease of hemidesmosomes. J Dermatol Sci 1999;20:134-154.

13. Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Autoimmune and inherited subepidermal blistering diseases: advances in the clinic and the laboratory. Adv Dermatol 2000;16:113-157.

14. Shornick JD. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1998;17:172-181.

15. Holmes RC, Black MM, Jurecka W, et al. Clues to the aetiology and pathogenesis of herpes gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1983;109:131-139.

16. Shornick JK, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. High frequency of histocompatibility antigens DR3 and DR4 in herpes gestationis. J Clin Invest 1981;68:553-555.

17. Shornick JK, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Paternal histocompatibility (HLA) antigens and maternal anti-HLA antibodies in herpes gestationis. J Invest Dermatol 1983;81:407-409.

18. Ortonne JP, Hsi BL, Verrando P, et al. Herpes gestationis factor reacts with the amniotic epithelial basement membrane. Br J Dermatol 1987;117:147-154.

19. Kelly SE, Bhogal BS, Wojnarowska F, Black MM. Expression of a pemphigoid gestationis-related antigen by human placenta. Br J Dermatol 1988;118:605-611.

20. Fairley JA, Heintz PW, Neuburg M, et al. Expression pattern of the bullous pemphigoid-180 antigen in normal and neoplastic epithelia. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:385-391.

21. Kelly SE, Black MM, Fleming S. Antigen-presenting cells in the skin and placenta in pemphigoid gestationis. Br J Dermatol 1990;122:593-599.

22. Borthwick GM, Holmes RC, Stirrat GM. Abnormal expression of class II MHC antigens in placentae from patients with pemphigoid gestationis. Placenta 1988;9:81-94.

23. Kelly SE, Black MM, Fleming S. Pemphigoid gestationis: a unique mechanism of initiation of an autoimmune response by MHC class II molecules. J Pathol 1989;158:81-82.

24. Borradori L, Saurat JH. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy. Toward a comprehensive view. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:778-780.

25. Shimanovich I, Bröcker EB, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: new insights into the pathogenesis lead to novel diagnostic tools. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;109:970-976.

Itching and rash in a boy and his grandmother

A boy came to the office with a rash and progressively severe itching for approximately 2 months (FIGURE 1). Examination showed an excoriated generalized papular eruption, including some urticarial-type papules and chronic eczematoid changes near the waist, axillae, hands, and wrists.

His grandmother, with whom he spends most weekends and a lot of time after school, also has had a rash and progressive itch for approximately 3 weeks. One feature of the dermopathy observed clinically, first located by hand lens examination and then confirmed by dermoscopy, is depicted in FIGURE 2.

FIGURE 1

Excoriated eruptions

FIGURE 2

Dermoscopic photograph of the dermatosis

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Scabies

The boy and his grandmother both have scabies, an infectious disease—in fact, the first human disease proven to be caused by a specific agent.1Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis, or scabies, is a mite in the arachnid class.2 In some states and localities, scabies cases or scabies outbreaks are reportable to the public health department.

The cardinal symptom of scabies is pruritus. The itch, especially with initial scabietic infestation, may be gradual in onset.3 Physical examination findings can vary from subtle and nonspecific to overwhelming and distinctive. Scabies can also mimic other dermopathies, complicating diagnosis. Undiagnosed and untreated, scabies can last a protracted period.

The dermopathy may be characterized by urticarial-type papules, vesicles, eczematoid change, excoriation, and bacterial superinfection, especially in children. Nodules may be present, particularly on the penis and scrotum. These may last for months after the infestation has cleared.3 The most commonly involved areas include fingers and finger webs, wrist folds, elbows, knees, the lower abdomen, armpits, thighs, male genitals, nipples, breasts, buttocks, and shoulder blades.3,4 In young children, scabies may be found anywhere, including palms, soles, face and scalp.

Affliction of multiple family members and finding dermatitis in these distinctive locations is helpful in diagnosis. Finding the mites’ burrows is considered pathognomonic because other burrowing diseases (eg, cutaneous larva migrans) are easily distinguished clinically.4 Extensive excoriation is a clinical clue to look for burrows.3

Transmission usually skin-to-skin

Scabies is generally transmitted by prolonged skin-to-skin contact, such as occurs in families or during sexual contact. It is possible to acquire scabies infestation via contaminated items of clothing or bed linens, but this is not regarded as a significant route of transmission.3 Transmission by casual contact, such as a handshake or hug, is unlikely.

Infestation with the S scabiei mite, referred to as scabies in man, is termed “mange” in other mammals known to host the mite (dogs, cats, rabbits, cattle, pigs, and horses). Mites from one host species generally do not establish themselves on another species, and thus are referred to as varieties, variants, or forms. Humans develop a transient dermopathy from infestation by animal scabies, but such infestations are mild and disappear spontaneously unless the person is in frequent contact with the infested animal.3,4

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of scabies—a great masquerader—is extensive, and includes atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, impetigo, insect bites, vasculitis, neurodermatitis, folliculitis, prurigo nodularis, psoriasis (crusted scabies), and a host of other dermopathies.3,4

Confirming the diagnosis

Finding the causative mite, its ova (eggs), or scybala (feces), confirms the diagnosis, although failure to find these does not rule out scabies. Papules or burrows that have not been excoriated are best for obtaining preparations for microscopic examination.3 Burrows may be found with nakedeye inspection, although use of a hand-held magnifier and good illumination make finding burrows easier.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy, performed with an otoscope-like, illuminated magnifier designed for skin assessment, provides reliable confirmation of S- or Z-shaped burrows. During dermoscopy, carefully examining the distal end of the burrows in the skin may reveal the “triangular black dot” of the scabies mite (FIGURE 2, top right)—the head of the mite.5 The body of the mite—light in color and oval—is not visible even with the most careful dermoscopic examination. The “black dot” of the mite may be visible with careful inspection with a hand lens. In the appropriate clinical setting, dermoscopic identification of an unequivocal burrow with the dark “triangle sign” at one end is diagnostic for scabies. When a digital photograph obtained through the dermatoscope is magnified, the distal end of the burrow (FIGURE 3) reveals the triangular head parts of the mite and the body within the burrow. This body is not evident with dermoscopy alone; the additional magnification via photography allows its visualization.

FIGURE 3

Magnification

Scabies mount

In instances where the physician is going to make an institution-wide recommendation with major ramifications, it is wise to positively identify the mite. A scabies mount performed at the location of the triangular dot will readily provide a mite for identification. Scabies mounts are prepared via a very superficial shave technique without anesthesia. The skin flakes are transferred to a slide and a drop of mineral oil is added. Alternatively, a drop of mineral oil can be placed on the skin and a superficial sample obtained.

Note that this technique differs from that of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation for fungal identification. The scabies mount technique is more like a superficial shave biopsy (with the knife blade parallel to the skin) than a KOH preparation (blade dragged along the skin surface more perpendicular to the skin).Microscopic examination of each slide reveals a mite (FIGURES 4 AND 5).

In our patient, 3 burrows were identified with a hand lens and confirmed by dermoscopy. In 2 burrows, the triangular dots were transferred to slides by doing a very superficial shave (without anesthesia) of the stratum corneum with a number 15 blade and handle. The material was placed on a slide, a drop of mineral oil added, and the slide examined microscopically (FIGURES 4 AND 5). These dermoscopically guided preparations each yielded a mite and little other debris.

FIGURE 4

Scabies mite

FIGURE 5

Mite, ova, and feces

Ink test

The “ink test” is another adjunct to help identify burrows. A nontoxic, watersoluble felt-tip marker is rubbed over an area suspected of having burrows. After waiting a few moments for the ink to sink into the disrupted stratum corneum overlying burrows, the ink is washed off, leaving an ink-demarcated burrow to examine.4 This can be performed as an adjunct to dermoscopy.5

The course of scabies

The mite’s life cycle

There are 4 stages in the mite’s life cycle: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. Female mites deposit 2 to 3 eggs per day as they create their burrows. The eggs are oval, 0.1 to 0.15 mm in length, and hatch in 3 to 8 days. The resultant larvae migrate to the skin surface and burrow into the intact stratum corneum to construct almost invisible, short burrows called molting pouches.

The larvae progress through 2 nymphal stages before a final molt to the adult stage. Larvae and nymphs live in molting pouches or in hair follicles. They appear similar to adults except for smaller size and, during the larval stage, 3 pair of legs. Adult female mites are 0.3 to 0.4 mm long and about 0.25 to 0.35 mm wide, about twice the size of males. Mating occurs when a male penetrates the molting pouch of the adult female. Impregnated females then extend their molting pouches to form the characteristic serpentine burrows, laying eggs in the process. The total period to progress from egg to the gravid female stage takes 10 to 14 days. The impregnated females spend the remaining 2 months of their lives in burrows.3,4

The mites live in and on the stratum corneum, burrowing into but never below the stratum corneum. The burrows appear as raised, serpentine lines varying from a few millimeters up to several centimeters long. Transmission occurs by the transfer of ova-bearing females.3,4

Cause of the rash and itch

The mites do not “bite.” Instead, the hallmark of scabies, when found, are the burrows created by the mites. However, it is common to see a papular urticarial type response as an allergic reaction to antigens associated with the mite itself, its scybala, and eggs. In fact, after acquiring scabies for the first time, itch does not appear for 2 to 6 weeks (average, 3 to 4 weeks) because the host needs to be sensitized to these antigens.4

It is not until the immunologic reactivity or sensitization develops that the host becomes symptomatic and aware of a problem. This requirement for sensitization explains the often gradual onset of itch. The incubation period is important in transmission to other individuals during the asymptomatic phase.3 However, a previously sensitized host may experience itch within hours to days after reinfestation.4

Epidemiology of scabies

Scabies infestations occur in all geographic areas and climates, and affects people of all ages and socioeconomic strata.7 For unexplained reasons, those with African ancestry rarely acquire scabies.7

It is most common in those who have close physical contact with others and, therefore, disproportionately affects children, mothers of young children, sexually active young adults, nursing home populations, and those in crowded living situations. Scabies is commonplace in developing countries. It is possible to acquire scabies after sleeping in unsanitary bedding. The scabies mite does not carry other diseases.7

Crusted scabies

Crusted scabies, a rare form of scabies also known as Norwegian scabies, is an aggressive infestation that usually occurs in immunodeficient, debilitated, or malnourished persons. Crusted scabies, because of the huge mite burden, is associated with greater transmissibility than scabies.7 Interestingly, because of impaired allergic response or indifference to itch, some of these patients may exhibit little pruritus.7

Treatment of scabies

Perhaps the most difficult job in treatment of scabies is treating asymptomatic contacts. Physicians may be reluctant to prescribe, and contacts themselves may be reluctant to take, appropriate treatment. These individuals often spread the infection for 4 to 6 weeks before they develop sensitization and clinical symptoms. Thus, it is essential that these asymptomatic contacts be treated or a cycle of reinfestation will be created.3 All sexual contacts, close personal contacts, and household contacts from within the preceding month should be examined and treated.8

Permethrin cream. The recommended treatment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is permethrin cream (5%) applied to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 to 14 hours. This recommendation includes careful application under fingernails, between toes, and on palms and soles. Infants may need the face and scalp treated in addition. Treatment of the face beyond infancy frequently results in a contact irritant dermatitis. Permethrin is effective and safe but costs more than lindane.8

Lindane. The CDC guidelines offer 2 alternatives to permethrin. One alternative, lindane 1% cream or lotion, can be applied in a thin layer to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 hours.

Lindane should not be used immediately after a bath or shower, and should not be used by persons who have extensive dermatitis, pregnant or lactating women, or children aged less than 2 years. Lindane resistance has been reported, including in the United States. Seizures have occurred when lindane was applied after a bath or used by patients who had extensive dermatitis. Aplastic anemia following lindane use also has been reported. Infants, young children, and pregnant or lactating women should not be treated with lindane; they can be treated with permethrin.8

Applying topical treatments. Topical scabicides should be applied to all skin from neck down, including intertriginous areas and the gluteal fold. The medication needs to be reapplied to hands if the hands are washed after application. It is advisable to cut fingernails short before applying scabicides and to ensure that scabicide is applied under fingernails. A toothpick can be used if necessary to assist in application under nails. In infants and small children, medication should be applied to face and scalp, avoiding the periorbital area.6

Other treatments. Ivermectin, the third treatment recommended by the CDC, can be administered as a single dose of 200 mcg/kg orally, and repeated in 2 weeks. Ivermectin is not recommended for pregnant or lactating patients. The safety of ivermectin in children who weigh less than 15 kg has not been determined.8

Some specialists recommend retreatment after 1 to 2 weeks for patients who are still symptomatic. Patients who do not respond to the recommended treatment should be retreated with an alternative regimen.8

Patients who have uncomplicated scabies and also are infected with HIV should receive the same treatment regimens as those who are HIV-negative.8 For patients with crusted scabies, the optimal regimen is unknown because no controlled therapeutic trials have been conducted. Expert opinion suggests augmented and combined regimens should be used for this aggressive infestation. Lindane should be avoided because of risks of neurotoxicity with heavy applications.8 Control of scabies epidemics (eg, in nursing homes, hospitals, residential facilities) require treatment of the entire population at risk.

Ancillary measures

Scabies mites may survive for a few days after leaving human skin. Thus, frequent bed linen changes minimize transmission via bedding. Hot-water laundry in temperatures of 120°F (49°s mites in 10 minutes and is sufficient to disinfect all bedding, clothing, and washable items.3

Other methods of disinfection include placing items in a dryer on the hot cycle for 10 to 30 minutes, pressing them with a warm iron, dry-cleaning, or placing in a sealed plastic bag for 7 to 14 days. Carpets or upholstery should be vacuumed through the heavy traffic areas. Fumigation of living areas and furniture with insecticide is unnecessary.6-8 Pets do not need to be treated.6 Children may return to school and childcare immediately following initial treatment.6

Follow-up of scabies patient

The boy’s mother is allowed to view the mites through the microscope, fostering her accepting the diagnosis and enhancing the chance for compliance with treatment, which involves treating the entire family.

Patients should be informed that the rash and pruritus of scabies may persist for 4 weeks after treatment because scabietic antigenic material remains until natural epidermal sloughing and turnover occurs.3 When symptoms or signs persist, evaluation should ensue for faulty application of topical scabicides and for treatment failure.7

Acknowledgments

The author (GNF) wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Elston and Heather Martinez, without whose assistance photographs like these would never happen; and Lisa Nichols, without whose acquisitive skills it never would have occurred to me to mite-hunt with a dermatoscope.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 East Second Street, Defiance, OH 43512. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Binder WD. Scabies. eMedicine [online database]. Available at: www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic517.htm. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

2. Arachnid. Wikipedia [online encyclopedia]. Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arachnid. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

3. Scabies. DPDx—CDC Parasitology Diagnostic Website. Available at: www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Scabies.htm. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

4. Arya V, Molinaro MJ, Majewski SS, Schwartz RA. Pediatric scabies. Cutis 2003;71:193-196.

5. Vazquez-Lopez F, Kreusch JF, Marghoob AA. Other uses of dermoscopy. In: Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005:301,305-306.

6. FAQs—scabies. Texas Department of Health Services, Infectious Disease Control Unit website. Available at: www.dshs.state.tx.us/idcu/disease/scabies/faqs/. Accessed on July 6, 2006.

7. Infestations and bites [chapter 15]. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Mosby; 2004:497-503.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-6):68-69.

A boy came to the office with a rash and progressively severe itching for approximately 2 months (FIGURE 1). Examination showed an excoriated generalized papular eruption, including some urticarial-type papules and chronic eczematoid changes near the waist, axillae, hands, and wrists.

His grandmother, with whom he spends most weekends and a lot of time after school, also has had a rash and progressive itch for approximately 3 weeks. One feature of the dermopathy observed clinically, first located by hand lens examination and then confirmed by dermoscopy, is depicted in FIGURE 2.

FIGURE 1

Excoriated eruptions

FIGURE 2

Dermoscopic photograph of the dermatosis

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Scabies

The boy and his grandmother both have scabies, an infectious disease—in fact, the first human disease proven to be caused by a specific agent.1Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis, or scabies, is a mite in the arachnid class.2 In some states and localities, scabies cases or scabies outbreaks are reportable to the public health department.

The cardinal symptom of scabies is pruritus. The itch, especially with initial scabietic infestation, may be gradual in onset.3 Physical examination findings can vary from subtle and nonspecific to overwhelming and distinctive. Scabies can also mimic other dermopathies, complicating diagnosis. Undiagnosed and untreated, scabies can last a protracted period.

The dermopathy may be characterized by urticarial-type papules, vesicles, eczematoid change, excoriation, and bacterial superinfection, especially in children. Nodules may be present, particularly on the penis and scrotum. These may last for months after the infestation has cleared.3 The most commonly involved areas include fingers and finger webs, wrist folds, elbows, knees, the lower abdomen, armpits, thighs, male genitals, nipples, breasts, buttocks, and shoulder blades.3,4 In young children, scabies may be found anywhere, including palms, soles, face and scalp.

Affliction of multiple family members and finding dermatitis in these distinctive locations is helpful in diagnosis. Finding the mites’ burrows is considered pathognomonic because other burrowing diseases (eg, cutaneous larva migrans) are easily distinguished clinically.4 Extensive excoriation is a clinical clue to look for burrows.3

Transmission usually skin-to-skin

Scabies is generally transmitted by prolonged skin-to-skin contact, such as occurs in families or during sexual contact. It is possible to acquire scabies infestation via contaminated items of clothing or bed linens, but this is not regarded as a significant route of transmission.3 Transmission by casual contact, such as a handshake or hug, is unlikely.

Infestation with the S scabiei mite, referred to as scabies in man, is termed “mange” in other mammals known to host the mite (dogs, cats, rabbits, cattle, pigs, and horses). Mites from one host species generally do not establish themselves on another species, and thus are referred to as varieties, variants, or forms. Humans develop a transient dermopathy from infestation by animal scabies, but such infestations are mild and disappear spontaneously unless the person is in frequent contact with the infested animal.3,4

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of scabies—a great masquerader—is extensive, and includes atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, impetigo, insect bites, vasculitis, neurodermatitis, folliculitis, prurigo nodularis, psoriasis (crusted scabies), and a host of other dermopathies.3,4

Confirming the diagnosis

Finding the causative mite, its ova (eggs), or scybala (feces), confirms the diagnosis, although failure to find these does not rule out scabies. Papules or burrows that have not been excoriated are best for obtaining preparations for microscopic examination.3 Burrows may be found with nakedeye inspection, although use of a hand-held magnifier and good illumination make finding burrows easier.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy, performed with an otoscope-like, illuminated magnifier designed for skin assessment, provides reliable confirmation of S- or Z-shaped burrows. During dermoscopy, carefully examining the distal end of the burrows in the skin may reveal the “triangular black dot” of the scabies mite (FIGURE 2, top right)—the head of the mite.5 The body of the mite—light in color and oval—is not visible even with the most careful dermoscopic examination. The “black dot” of the mite may be visible with careful inspection with a hand lens. In the appropriate clinical setting, dermoscopic identification of an unequivocal burrow with the dark “triangle sign” at one end is diagnostic for scabies. When a digital photograph obtained through the dermatoscope is magnified, the distal end of the burrow (FIGURE 3) reveals the triangular head parts of the mite and the body within the burrow. This body is not evident with dermoscopy alone; the additional magnification via photography allows its visualization.

FIGURE 3

Magnification

Scabies mount

In instances where the physician is going to make an institution-wide recommendation with major ramifications, it is wise to positively identify the mite. A scabies mount performed at the location of the triangular dot will readily provide a mite for identification. Scabies mounts are prepared via a very superficial shave technique without anesthesia. The skin flakes are transferred to a slide and a drop of mineral oil is added. Alternatively, a drop of mineral oil can be placed on the skin and a superficial sample obtained.

Note that this technique differs from that of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation for fungal identification. The scabies mount technique is more like a superficial shave biopsy (with the knife blade parallel to the skin) than a KOH preparation (blade dragged along the skin surface more perpendicular to the skin).Microscopic examination of each slide reveals a mite (FIGURES 4 AND 5).

In our patient, 3 burrows were identified with a hand lens and confirmed by dermoscopy. In 2 burrows, the triangular dots were transferred to slides by doing a very superficial shave (without anesthesia) of the stratum corneum with a number 15 blade and handle. The material was placed on a slide, a drop of mineral oil added, and the slide examined microscopically (FIGURES 4 AND 5). These dermoscopically guided preparations each yielded a mite and little other debris.

FIGURE 4

Scabies mite

FIGURE 5

Mite, ova, and feces

Ink test

The “ink test” is another adjunct to help identify burrows. A nontoxic, watersoluble felt-tip marker is rubbed over an area suspected of having burrows. After waiting a few moments for the ink to sink into the disrupted stratum corneum overlying burrows, the ink is washed off, leaving an ink-demarcated burrow to examine.4 This can be performed as an adjunct to dermoscopy.5

The course of scabies

The mite’s life cycle

There are 4 stages in the mite’s life cycle: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. Female mites deposit 2 to 3 eggs per day as they create their burrows. The eggs are oval, 0.1 to 0.15 mm in length, and hatch in 3 to 8 days. The resultant larvae migrate to the skin surface and burrow into the intact stratum corneum to construct almost invisible, short burrows called molting pouches.

The larvae progress through 2 nymphal stages before a final molt to the adult stage. Larvae and nymphs live in molting pouches or in hair follicles. They appear similar to adults except for smaller size and, during the larval stage, 3 pair of legs. Adult female mites are 0.3 to 0.4 mm long and about 0.25 to 0.35 mm wide, about twice the size of males. Mating occurs when a male penetrates the molting pouch of the adult female. Impregnated females then extend their molting pouches to form the characteristic serpentine burrows, laying eggs in the process. The total period to progress from egg to the gravid female stage takes 10 to 14 days. The impregnated females spend the remaining 2 months of their lives in burrows.3,4

The mites live in and on the stratum corneum, burrowing into but never below the stratum corneum. The burrows appear as raised, serpentine lines varying from a few millimeters up to several centimeters long. Transmission occurs by the transfer of ova-bearing females.3,4

Cause of the rash and itch

The mites do not “bite.” Instead, the hallmark of scabies, when found, are the burrows created by the mites. However, it is common to see a papular urticarial type response as an allergic reaction to antigens associated with the mite itself, its scybala, and eggs. In fact, after acquiring scabies for the first time, itch does not appear for 2 to 6 weeks (average, 3 to 4 weeks) because the host needs to be sensitized to these antigens.4

It is not until the immunologic reactivity or sensitization develops that the host becomes symptomatic and aware of a problem. This requirement for sensitization explains the often gradual onset of itch. The incubation period is important in transmission to other individuals during the asymptomatic phase.3 However, a previously sensitized host may experience itch within hours to days after reinfestation.4

Epidemiology of scabies

Scabies infestations occur in all geographic areas and climates, and affects people of all ages and socioeconomic strata.7 For unexplained reasons, those with African ancestry rarely acquire scabies.7

It is most common in those who have close physical contact with others and, therefore, disproportionately affects children, mothers of young children, sexually active young adults, nursing home populations, and those in crowded living situations. Scabies is commonplace in developing countries. It is possible to acquire scabies after sleeping in unsanitary bedding. The scabies mite does not carry other diseases.7

Crusted scabies

Crusted scabies, a rare form of scabies also known as Norwegian scabies, is an aggressive infestation that usually occurs in immunodeficient, debilitated, or malnourished persons. Crusted scabies, because of the huge mite burden, is associated with greater transmissibility than scabies.7 Interestingly, because of impaired allergic response or indifference to itch, some of these patients may exhibit little pruritus.7

Treatment of scabies

Perhaps the most difficult job in treatment of scabies is treating asymptomatic contacts. Physicians may be reluctant to prescribe, and contacts themselves may be reluctant to take, appropriate treatment. These individuals often spread the infection for 4 to 6 weeks before they develop sensitization and clinical symptoms. Thus, it is essential that these asymptomatic contacts be treated or a cycle of reinfestation will be created.3 All sexual contacts, close personal contacts, and household contacts from within the preceding month should be examined and treated.8

Permethrin cream. The recommended treatment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is permethrin cream (5%) applied to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 to 14 hours. This recommendation includes careful application under fingernails, between toes, and on palms and soles. Infants may need the face and scalp treated in addition. Treatment of the face beyond infancy frequently results in a contact irritant dermatitis. Permethrin is effective and safe but costs more than lindane.8

Lindane. The CDC guidelines offer 2 alternatives to permethrin. One alternative, lindane 1% cream or lotion, can be applied in a thin layer to all areas of the body from the neck down and thoroughly washed off after 8 hours.

Lindane should not be used immediately after a bath or shower, and should not be used by persons who have extensive dermatitis, pregnant or lactating women, or children aged less than 2 years. Lindane resistance has been reported, including in the United States. Seizures have occurred when lindane was applied after a bath or used by patients who had extensive dermatitis. Aplastic anemia following lindane use also has been reported. Infants, young children, and pregnant or lactating women should not be treated with lindane; they can be treated with permethrin.8

Applying topical treatments. Topical scabicides should be applied to all skin from neck down, including intertriginous areas and the gluteal fold. The medication needs to be reapplied to hands if the hands are washed after application. It is advisable to cut fingernails short before applying scabicides and to ensure that scabicide is applied under fingernails. A toothpick can be used if necessary to assist in application under nails. In infants and small children, medication should be applied to face and scalp, avoiding the periorbital area.6

Other treatments. Ivermectin, the third treatment recommended by the CDC, can be administered as a single dose of 200 mcg/kg orally, and repeated in 2 weeks. Ivermectin is not recommended for pregnant or lactating patients. The safety of ivermectin in children who weigh less than 15 kg has not been determined.8

Some specialists recommend retreatment after 1 to 2 weeks for patients who are still symptomatic. Patients who do not respond to the recommended treatment should be retreated with an alternative regimen.8

Patients who have uncomplicated scabies and also are infected with HIV should receive the same treatment regimens as those who are HIV-negative.8 For patients with crusted scabies, the optimal regimen is unknown because no controlled therapeutic trials have been conducted. Expert opinion suggests augmented and combined regimens should be used for this aggressive infestation. Lindane should be avoided because of risks of neurotoxicity with heavy applications.8 Control of scabies epidemics (eg, in nursing homes, hospitals, residential facilities) require treatment of the entire population at risk.

Ancillary measures

Scabies mites may survive for a few days after leaving human skin. Thus, frequent bed linen changes minimize transmission via bedding. Hot-water laundry in temperatures of 120°F (49°s mites in 10 minutes and is sufficient to disinfect all bedding, clothing, and washable items.3

Other methods of disinfection include placing items in a dryer on the hot cycle for 10 to 30 minutes, pressing them with a warm iron, dry-cleaning, or placing in a sealed plastic bag for 7 to 14 days. Carpets or upholstery should be vacuumed through the heavy traffic areas. Fumigation of living areas and furniture with insecticide is unnecessary.6-8 Pets do not need to be treated.6 Children may return to school and childcare immediately following initial treatment.6

Follow-up of scabies patient

The boy’s mother is allowed to view the mites through the microscope, fostering her accepting the diagnosis and enhancing the chance for compliance with treatment, which involves treating the entire family.

Patients should be informed that the rash and pruritus of scabies may persist for 4 weeks after treatment because scabietic antigenic material remains until natural epidermal sloughing and turnover occurs.3 When symptoms or signs persist, evaluation should ensue for faulty application of topical scabicides and for treatment failure.7

Acknowledgments

The author (GNF) wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Elston and Heather Martinez, without whose assistance photographs like these would never happen; and Lisa Nichols, without whose acquisitive skills it never would have occurred to me to mite-hunt with a dermatoscope.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, Defiance Clinic, 1400 East Second Street, Defiance, OH 43512. E-mail: [email protected]

A boy came to the office with a rash and progressively severe itching for approximately 2 months (FIGURE 1). Examination showed an excoriated generalized papular eruption, including some urticarial-type papules and chronic eczematoid changes near the waist, axillae, hands, and wrists.

His grandmother, with whom he spends most weekends and a lot of time after school, also has had a rash and progressive itch for approximately 3 weeks. One feature of the dermopathy observed clinically, first located by hand lens examination and then confirmed by dermoscopy, is depicted in FIGURE 2.

FIGURE 1

Excoriated eruptions

FIGURE 2

Dermoscopic photograph of the dermatosis

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Scabies

The boy and his grandmother both have scabies, an infectious disease—in fact, the first human disease proven to be caused by a specific agent.1Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis, or scabies, is a mite in the arachnid class.2 In some states and localities, scabies cases or scabies outbreaks are reportable to the public health department.

The cardinal symptom of scabies is pruritus. The itch, especially with initial scabietic infestation, may be gradual in onset.3 Physical examination findings can vary from subtle and nonspecific to overwhelming and distinctive. Scabies can also mimic other dermopathies, complicating diagnosis. Undiagnosed and untreated, scabies can last a protracted period.

The dermopathy may be characterized by urticarial-type papules, vesicles, eczematoid change, excoriation, and bacterial superinfection, especially in children. Nodules may be present, particularly on the penis and scrotum. These may last for months after the infestation has cleared.3 The most commonly involved areas include fingers and finger webs, wrist folds, elbows, knees, the lower abdomen, armpits, thighs, male genitals, nipples, breasts, buttocks, and shoulder blades.3,4 In young children, scabies may be found anywhere, including palms, soles, face and scalp.

Affliction of multiple family members and finding dermatitis in these distinctive locations is helpful in diagnosis. Finding the mites’ burrows is considered pathognomonic because other burrowing diseases (eg, cutaneous larva migrans) are easily distinguished clinically.4 Extensive excoriation is a clinical clue to look for burrows.3

Transmission usually skin-to-skin

Scabies is generally transmitted by prolonged skin-to-skin contact, such as occurs in families or during sexual contact. It is possible to acquire scabies infestation via contaminated items of clothing or bed linens, but this is not regarded as a significant route of transmission.3 Transmission by casual contact, such as a handshake or hug, is unlikely.

Infestation with the S scabiei mite, referred to as scabies in man, is termed “mange” in other mammals known to host the mite (dogs, cats, rabbits, cattle, pigs, and horses). Mites from one host species generally do not establish themselves on another species, and thus are referred to as varieties, variants, or forms. Humans develop a transient dermopathy from infestation by animal scabies, but such infestations are mild and disappear spontaneously unless the person is in frequent contact with the infested animal.3,4

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of scabies—a great masquerader—is extensive, and includes atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, impetigo, insect bites, vasculitis, neurodermatitis, folliculitis, prurigo nodularis, psoriasis (crusted scabies), and a host of other dermopathies.3,4

Confirming the diagnosis