User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Morning PT

Tuesdays and Fridays are tough. Not so much because of clinic, but rather because of the 32 minutes before clinic that I’m on the Peloton bike. They are the mornings I dedicate to training VO2max.

Training VO2max, or maximal oxygen consumption, is simple. Spin for a leisurely, easy-breathing, 4 minutes, then for 4 minutes push yourself until you see the light of heaven and wish for death to come. Then relax for 4 minutes again. Repeat this cycle four to six times. Done justly, you will dread Tuesdays and Fridays too. The punishing cycle of a 4-minute push, then 4-minute recovery is, however, an excellent way to improve cardiovascular fitness. And no, I’m not training for the Boston Marathon, so why am I working so hard? Because I’m training for marathon clinic days for the next 20 years.

Now more than ever, I feel we have to be physically fit to deal with a physicians’ day’s work. It’s exhausting. The root cause is too much work, yes, but I believe being physically fit could help.

I was talking to an 86-year-old patient about this very topic recently. He was short, with a well-manicured goatee and shiny head. He stuck his arm out to shake my hand. “Glad we’re back to handshakes again, doc.” His grip was that of a 30-year-old. “Buff” you’d likely describe him: He is noticeably muscular, not a skinny old man. He’s an old Navy Master Chief who started a business in wholesale flowers, which distributes all over the United States. And he’s still working full time. Impressed, I asked his secret for such vigor. PT, he replied.

PT, or physical training, is a foundational element of the Navy. Every sailor starts his or her day with morning PT before carrying out their duties. Some 30 years later, this guy is still getting after it. He does push-ups, sit-ups, and pull-ups nearly every morning. Morning PT is what he attributes to his success not only in health, but also business. As he sees it, he has the business savvy and experience of an old guy and the energy and stamina of a college kid. A good combination for a successful life.

I’ve always been pretty fit. Lately, I’ve been trying to take it to the next level, to not just be “physically active,” but rather “high-performance fit.” There are plenty of sources for instruction; how to stay young and healthy isn’t a new idea after all. I mean, Herodotus wrote of finding the Fountain of Youth in the 5th century BCE. A couple thousand years later, it’s still on trend. One of my favorite sages giving health span advice is Peter Attia, MD. I’ve been a fan since I met him at TEDMED in 2013 and I marvel at the astounding body of work he has created since. A Johns Hopkins–trained surgeon, he has spent his career reviewing the scientific literature about longevity and sharing it as actionable content. His book, “Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity” (New York: Penguin Random House, 2023) is a nice summary of his work. I recommend it.

Right now I’m switching between type 2 muscle fiber work (lots of jumping like my 2-year-old) and cardiovascular training including the aforementioned VO2max work. I cannot say that my patient inbox is any cleaner, or that I’m faster in the office, but I’m not flagging by the end of the day anymore. Master Chief challenged me to match his 10 pull-ups before he returns for his follow up visit. I’ll gladly give up Peloton sprints to work on that.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Tuesdays and Fridays are tough. Not so much because of clinic, but rather because of the 32 minutes before clinic that I’m on the Peloton bike. They are the mornings I dedicate to training VO2max.

Training VO2max, or maximal oxygen consumption, is simple. Spin for a leisurely, easy-breathing, 4 minutes, then for 4 minutes push yourself until you see the light of heaven and wish for death to come. Then relax for 4 minutes again. Repeat this cycle four to six times. Done justly, you will dread Tuesdays and Fridays too. The punishing cycle of a 4-minute push, then 4-minute recovery is, however, an excellent way to improve cardiovascular fitness. And no, I’m not training for the Boston Marathon, so why am I working so hard? Because I’m training for marathon clinic days for the next 20 years.

Now more than ever, I feel we have to be physically fit to deal with a physicians’ day’s work. It’s exhausting. The root cause is too much work, yes, but I believe being physically fit could help.

I was talking to an 86-year-old patient about this very topic recently. He was short, with a well-manicured goatee and shiny head. He stuck his arm out to shake my hand. “Glad we’re back to handshakes again, doc.” His grip was that of a 30-year-old. “Buff” you’d likely describe him: He is noticeably muscular, not a skinny old man. He’s an old Navy Master Chief who started a business in wholesale flowers, which distributes all over the United States. And he’s still working full time. Impressed, I asked his secret for such vigor. PT, he replied.

PT, or physical training, is a foundational element of the Navy. Every sailor starts his or her day with morning PT before carrying out their duties. Some 30 years later, this guy is still getting after it. He does push-ups, sit-ups, and pull-ups nearly every morning. Morning PT is what he attributes to his success not only in health, but also business. As he sees it, he has the business savvy and experience of an old guy and the energy and stamina of a college kid. A good combination for a successful life.

I’ve always been pretty fit. Lately, I’ve been trying to take it to the next level, to not just be “physically active,” but rather “high-performance fit.” There are plenty of sources for instruction; how to stay young and healthy isn’t a new idea after all. I mean, Herodotus wrote of finding the Fountain of Youth in the 5th century BCE. A couple thousand years later, it’s still on trend. One of my favorite sages giving health span advice is Peter Attia, MD. I’ve been a fan since I met him at TEDMED in 2013 and I marvel at the astounding body of work he has created since. A Johns Hopkins–trained surgeon, he has spent his career reviewing the scientific literature about longevity and sharing it as actionable content. His book, “Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity” (New York: Penguin Random House, 2023) is a nice summary of his work. I recommend it.

Right now I’m switching between type 2 muscle fiber work (lots of jumping like my 2-year-old) and cardiovascular training including the aforementioned VO2max work. I cannot say that my patient inbox is any cleaner, or that I’m faster in the office, but I’m not flagging by the end of the day anymore. Master Chief challenged me to match his 10 pull-ups before he returns for his follow up visit. I’ll gladly give up Peloton sprints to work on that.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Tuesdays and Fridays are tough. Not so much because of clinic, but rather because of the 32 minutes before clinic that I’m on the Peloton bike. They are the mornings I dedicate to training VO2max.

Training VO2max, or maximal oxygen consumption, is simple. Spin for a leisurely, easy-breathing, 4 minutes, then for 4 minutes push yourself until you see the light of heaven and wish for death to come. Then relax for 4 minutes again. Repeat this cycle four to six times. Done justly, you will dread Tuesdays and Fridays too. The punishing cycle of a 4-minute push, then 4-minute recovery is, however, an excellent way to improve cardiovascular fitness. And no, I’m not training for the Boston Marathon, so why am I working so hard? Because I’m training for marathon clinic days for the next 20 years.

Now more than ever, I feel we have to be physically fit to deal with a physicians’ day’s work. It’s exhausting. The root cause is too much work, yes, but I believe being physically fit could help.

I was talking to an 86-year-old patient about this very topic recently. He was short, with a well-manicured goatee and shiny head. He stuck his arm out to shake my hand. “Glad we’re back to handshakes again, doc.” His grip was that of a 30-year-old. “Buff” you’d likely describe him: He is noticeably muscular, not a skinny old man. He’s an old Navy Master Chief who started a business in wholesale flowers, which distributes all over the United States. And he’s still working full time. Impressed, I asked his secret for such vigor. PT, he replied.

PT, or physical training, is a foundational element of the Navy. Every sailor starts his or her day with morning PT before carrying out their duties. Some 30 years later, this guy is still getting after it. He does push-ups, sit-ups, and pull-ups nearly every morning. Morning PT is what he attributes to his success not only in health, but also business. As he sees it, he has the business savvy and experience of an old guy and the energy and stamina of a college kid. A good combination for a successful life.

I’ve always been pretty fit. Lately, I’ve been trying to take it to the next level, to not just be “physically active,” but rather “high-performance fit.” There are plenty of sources for instruction; how to stay young and healthy isn’t a new idea after all. I mean, Herodotus wrote of finding the Fountain of Youth in the 5th century BCE. A couple thousand years later, it’s still on trend. One of my favorite sages giving health span advice is Peter Attia, MD. I’ve been a fan since I met him at TEDMED in 2013 and I marvel at the astounding body of work he has created since. A Johns Hopkins–trained surgeon, he has spent his career reviewing the scientific literature about longevity and sharing it as actionable content. His book, “Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity” (New York: Penguin Random House, 2023) is a nice summary of his work. I recommend it.

Right now I’m switching between type 2 muscle fiber work (lots of jumping like my 2-year-old) and cardiovascular training including the aforementioned VO2max work. I cannot say that my patient inbox is any cleaner, or that I’m faster in the office, but I’m not flagging by the end of the day anymore. Master Chief challenged me to match his 10 pull-ups before he returns for his follow up visit. I’ll gladly give up Peloton sprints to work on that.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Review supports continued mask-wearing in health care visits

A new study urges people to continue wearing protective masks in medical settings, even though the U.S. public health emergency declaration around COVID-19 has expired.

Masks continue to lower the risk of catching the virus during medical visits, according to the study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine. And there was not much difference between wearing surgical masks and N95 respirators in health care settings.

The researchers reviewed 3 randomized trials and 21 observational studies to compare the effectiveness of those and cloth masks in reducing COVID-19 transmission.

Tara N. Palmore, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, and David K. Henderson, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., wrote in an opinion article accompanying the study.

“In our enthusiasm to return to the appearance and feeling of normalcy, and as institutions decide which mitigation strategies to discontinue, we strongly advocate not discarding this important lesson learned for the sake of our patients’ safety,” Dr. Palmore and Dr. Henderson wrote.

Surgical masks limit the spread of aerosols and droplets from people who have the flu, coronaviruses or other respiratory viruses, CNN reported. And while masks are not 100% effective, they substantially lower the amount of virus put into the air via coughing and talking.

The study said one reason people should wear masks to medical settings is because “health care personnel are notorious for coming to work while ill.” Transmission from patient to staff and staff to patient is still possible, but rare, when both are masked.

The review authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Palmore has received grants from the NIH, Rigel, Gilead, and AbbVie, and Dr. Henderson is a past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A new study urges people to continue wearing protective masks in medical settings, even though the U.S. public health emergency declaration around COVID-19 has expired.

Masks continue to lower the risk of catching the virus during medical visits, according to the study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine. And there was not much difference between wearing surgical masks and N95 respirators in health care settings.

The researchers reviewed 3 randomized trials and 21 observational studies to compare the effectiveness of those and cloth masks in reducing COVID-19 transmission.

Tara N. Palmore, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, and David K. Henderson, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., wrote in an opinion article accompanying the study.

“In our enthusiasm to return to the appearance and feeling of normalcy, and as institutions decide which mitigation strategies to discontinue, we strongly advocate not discarding this important lesson learned for the sake of our patients’ safety,” Dr. Palmore and Dr. Henderson wrote.

Surgical masks limit the spread of aerosols and droplets from people who have the flu, coronaviruses or other respiratory viruses, CNN reported. And while masks are not 100% effective, they substantially lower the amount of virus put into the air via coughing and talking.

The study said one reason people should wear masks to medical settings is because “health care personnel are notorious for coming to work while ill.” Transmission from patient to staff and staff to patient is still possible, but rare, when both are masked.

The review authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Palmore has received grants from the NIH, Rigel, Gilead, and AbbVie, and Dr. Henderson is a past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A new study urges people to continue wearing protective masks in medical settings, even though the U.S. public health emergency declaration around COVID-19 has expired.

Masks continue to lower the risk of catching the virus during medical visits, according to the study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine. And there was not much difference between wearing surgical masks and N95 respirators in health care settings.

The researchers reviewed 3 randomized trials and 21 observational studies to compare the effectiveness of those and cloth masks in reducing COVID-19 transmission.

Tara N. Palmore, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, and David K. Henderson, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., wrote in an opinion article accompanying the study.

“In our enthusiasm to return to the appearance and feeling of normalcy, and as institutions decide which mitigation strategies to discontinue, we strongly advocate not discarding this important lesson learned for the sake of our patients’ safety,” Dr. Palmore and Dr. Henderson wrote.

Surgical masks limit the spread of aerosols and droplets from people who have the flu, coronaviruses or other respiratory viruses, CNN reported. And while masks are not 100% effective, they substantially lower the amount of virus put into the air via coughing and talking.

The study said one reason people should wear masks to medical settings is because “health care personnel are notorious for coming to work while ill.” Transmission from patient to staff and staff to patient is still possible, but rare, when both are masked.

The review authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Palmore has received grants from the NIH, Rigel, Gilead, and AbbVie, and Dr. Henderson is a past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Evidence of TAVR benefit extends to cardiogenic shock

Early risks outweighed at 1 year

For patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), adverse outcomes are more common in those who are in cardiogenic shock than those who are not, but the greater risks appear to be completely concentrated in the early period of recovery, suggests a propensity-matched study.

reported Abhijeet Dhoble, MD, associate professor and an interventional cardiologist at McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

Their results were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The study, which drew data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Replacement (STS/ACC TVR) Registry, looked only at patients who underwent TAVR with the Sapien3 or Sapience3 Ultra device. Patients with CS were propensity matched to Sapien device-treated patients in the registry without CS.

Taken from a pool of 9,348 patients with CS and 299,600 patients without, the matching included a large array of clinically relevant covariates, including age, gender, prior cardiovascular events, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class.

After matching, there were 4,952 patients in each arm. The baseline Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score was approximately 10.0 in both arms. About half had atrial fibrillation and 90% were in NYHA class III or IV. The median LVEF in both groups was 39.9%.

Mortality more than twofold higher in CS patients

At 30 days, outcomes were worse in patients with CS, including the proportion who died (12.9% vs. 4.9%; P < .0001) and the proportion with stroke (3.3% vs. 1.9%; P < .0001).

The only major study endpoint not significantly different, although higher in the CS group, was the rate of readmission (12.0% vs. 11.0%; P = .25).

At 1 year, the differences in the rates of mortality (29.7% vs. 22.6%; P < .0001) and stroke (4.3% vs. 3.1%; P = .0004) had narrowed modestly but remained highly significant. A closer analysis indicated that almost all of the difference in the rate of events occurred prior to hospital discharge.

In fact, mortality (9.9% vs. 2.7%; P < .0001), stroke (2.9% vs. 1.5%; P < .0001), major vascular complications (2.3% vs. 1.9%; P = .0002), life-threatening bleeding (2.5% vs. 0.7%; P < .0001), new dialysis (3.5% vs. 1.1%; P < .0001) and new onset atrial fibrillation (3.8% vs. 1.6%; P < .0001) were all significantly higher in the CS group in this very early time period. By hazard ratio (HR), the risk of a major event prior to leaving the hospital was nearly threefold higher (HR 2.3; P < .0001) in the CS group.

Yet, there was no significant difference in the accumulation of adverse events after discharge. When compared for major events in the landmark analysis, the event curves were essentially superimposable from 30 days to 1 year. During this period, event rates were 19.3% versus 18.5% for CS and non-CS patients (HR 1.07; P = .2640).

The higher rate of events was unrelated to procedural complications, which were very low in both groups and did not differ significantly. Transition to open surgery, annular disruption, aortic dissection, coronary occlusion, and device embolization occurred in < 1% of patients in both groups.

Predictors of a poor outcome identified

On multivariate analysis, the predictors of events in the CS patients were comorbidities. Despite propensity matching, being on dialysis, having a permanent pacemaker, or having a mechanical assist device were all independent predictors of mortality risk specific to the CS group.

Age and baseline Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score were not predictors.

These risk factors deserve consideration when evaluating CS candidates for TAVR, but Dr. Dhoble said that none are absolute contraindications. Rather, he advised that they should be considered in the context of the entire clinical picture, including the expected benefit from TAVR. Indeed, the benefit-to-risk ratio generally favors TAVR in CS patients, particularly those with obstructive CS caused by aortic stenosis, according to Dr. Dhoble.

“Efforts should be made not only to avoid delaying TAVR in such patients but also to prevent CS by early definitive treatment of patients with aortic stenosis,” he said.

These data are useful and important, said Jonathan Schwartz, MD, medical director, interventional cardiology, Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C.

CS candidates for TAVR “are some of the sickest patients we treat. It is nice to finally have some data for this group,” he said. He agreed that CS patients can derive major benefit from TAVR if appropriately selected.

While many CS patients are already considered for TAVR, one source of hesitation has been the exclusion of CS patients from major TAVR trials, said Dr. Dhoble. He hopes these data will provide a framework for clinical decisions.

Ironically, the first TAVR patient and half of the initial series of 38 TAVR patients had CS, noted Alain G. Cribier, MD, director of cardiology, Charles Nicolle Hospital, University of Rouen, France. As the primary investigator of that initial TAVR study, conducted more than 20 years ago, he said he was not surprised by the favorable results of the propensity analysis.

“There is an almost miraculous clinical improvement to be achieved when you succeed with the procedure,” said Dr. Cribier, recounting his own experience. Improvements in LVEF of up to 30% can be achieved “within a day or two or even the first day,” he said.

Dr. Dhoble reports financial relationships with Abbott Vascular and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Schwartz reports that he has financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr. Cribier reports a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences.

Early risks outweighed at 1 year

Early risks outweighed at 1 year

For patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), adverse outcomes are more common in those who are in cardiogenic shock than those who are not, but the greater risks appear to be completely concentrated in the early period of recovery, suggests a propensity-matched study.

reported Abhijeet Dhoble, MD, associate professor and an interventional cardiologist at McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

Their results were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The study, which drew data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Replacement (STS/ACC TVR) Registry, looked only at patients who underwent TAVR with the Sapien3 or Sapience3 Ultra device. Patients with CS were propensity matched to Sapien device-treated patients in the registry without CS.

Taken from a pool of 9,348 patients with CS and 299,600 patients without, the matching included a large array of clinically relevant covariates, including age, gender, prior cardiovascular events, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class.

After matching, there were 4,952 patients in each arm. The baseline Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score was approximately 10.0 in both arms. About half had atrial fibrillation and 90% were in NYHA class III or IV. The median LVEF in both groups was 39.9%.

Mortality more than twofold higher in CS patients

At 30 days, outcomes were worse in patients with CS, including the proportion who died (12.9% vs. 4.9%; P < .0001) and the proportion with stroke (3.3% vs. 1.9%; P < .0001).

The only major study endpoint not significantly different, although higher in the CS group, was the rate of readmission (12.0% vs. 11.0%; P = .25).

At 1 year, the differences in the rates of mortality (29.7% vs. 22.6%; P < .0001) and stroke (4.3% vs. 3.1%; P = .0004) had narrowed modestly but remained highly significant. A closer analysis indicated that almost all of the difference in the rate of events occurred prior to hospital discharge.

In fact, mortality (9.9% vs. 2.7%; P < .0001), stroke (2.9% vs. 1.5%; P < .0001), major vascular complications (2.3% vs. 1.9%; P = .0002), life-threatening bleeding (2.5% vs. 0.7%; P < .0001), new dialysis (3.5% vs. 1.1%; P < .0001) and new onset atrial fibrillation (3.8% vs. 1.6%; P < .0001) were all significantly higher in the CS group in this very early time period. By hazard ratio (HR), the risk of a major event prior to leaving the hospital was nearly threefold higher (HR 2.3; P < .0001) in the CS group.

Yet, there was no significant difference in the accumulation of adverse events after discharge. When compared for major events in the landmark analysis, the event curves were essentially superimposable from 30 days to 1 year. During this period, event rates were 19.3% versus 18.5% for CS and non-CS patients (HR 1.07; P = .2640).

The higher rate of events was unrelated to procedural complications, which were very low in both groups and did not differ significantly. Transition to open surgery, annular disruption, aortic dissection, coronary occlusion, and device embolization occurred in < 1% of patients in both groups.

Predictors of a poor outcome identified

On multivariate analysis, the predictors of events in the CS patients were comorbidities. Despite propensity matching, being on dialysis, having a permanent pacemaker, or having a mechanical assist device were all independent predictors of mortality risk specific to the CS group.

Age and baseline Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score were not predictors.

These risk factors deserve consideration when evaluating CS candidates for TAVR, but Dr. Dhoble said that none are absolute contraindications. Rather, he advised that they should be considered in the context of the entire clinical picture, including the expected benefit from TAVR. Indeed, the benefit-to-risk ratio generally favors TAVR in CS patients, particularly those with obstructive CS caused by aortic stenosis, according to Dr. Dhoble.

“Efforts should be made not only to avoid delaying TAVR in such patients but also to prevent CS by early definitive treatment of patients with aortic stenosis,” he said.

These data are useful and important, said Jonathan Schwartz, MD, medical director, interventional cardiology, Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C.

CS candidates for TAVR “are some of the sickest patients we treat. It is nice to finally have some data for this group,” he said. He agreed that CS patients can derive major benefit from TAVR if appropriately selected.

While many CS patients are already considered for TAVR, one source of hesitation has been the exclusion of CS patients from major TAVR trials, said Dr. Dhoble. He hopes these data will provide a framework for clinical decisions.

Ironically, the first TAVR patient and half of the initial series of 38 TAVR patients had CS, noted Alain G. Cribier, MD, director of cardiology, Charles Nicolle Hospital, University of Rouen, France. As the primary investigator of that initial TAVR study, conducted more than 20 years ago, he said he was not surprised by the favorable results of the propensity analysis.

“There is an almost miraculous clinical improvement to be achieved when you succeed with the procedure,” said Dr. Cribier, recounting his own experience. Improvements in LVEF of up to 30% can be achieved “within a day or two or even the first day,” he said.

Dr. Dhoble reports financial relationships with Abbott Vascular and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Schwartz reports that he has financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr. Cribier reports a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences.

For patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), adverse outcomes are more common in those who are in cardiogenic shock than those who are not, but the greater risks appear to be completely concentrated in the early period of recovery, suggests a propensity-matched study.

reported Abhijeet Dhoble, MD, associate professor and an interventional cardiologist at McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston.

Their results were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The study, which drew data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Replacement (STS/ACC TVR) Registry, looked only at patients who underwent TAVR with the Sapien3 or Sapience3 Ultra device. Patients with CS were propensity matched to Sapien device-treated patients in the registry without CS.

Taken from a pool of 9,348 patients with CS and 299,600 patients without, the matching included a large array of clinically relevant covariates, including age, gender, prior cardiovascular events, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class.

After matching, there were 4,952 patients in each arm. The baseline Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score was approximately 10.0 in both arms. About half had atrial fibrillation and 90% were in NYHA class III or IV. The median LVEF in both groups was 39.9%.

Mortality more than twofold higher in CS patients

At 30 days, outcomes were worse in patients with CS, including the proportion who died (12.9% vs. 4.9%; P < .0001) and the proportion with stroke (3.3% vs. 1.9%; P < .0001).

The only major study endpoint not significantly different, although higher in the CS group, was the rate of readmission (12.0% vs. 11.0%; P = .25).

At 1 year, the differences in the rates of mortality (29.7% vs. 22.6%; P < .0001) and stroke (4.3% vs. 3.1%; P = .0004) had narrowed modestly but remained highly significant. A closer analysis indicated that almost all of the difference in the rate of events occurred prior to hospital discharge.

In fact, mortality (9.9% vs. 2.7%; P < .0001), stroke (2.9% vs. 1.5%; P < .0001), major vascular complications (2.3% vs. 1.9%; P = .0002), life-threatening bleeding (2.5% vs. 0.7%; P < .0001), new dialysis (3.5% vs. 1.1%; P < .0001) and new onset atrial fibrillation (3.8% vs. 1.6%; P < .0001) were all significantly higher in the CS group in this very early time period. By hazard ratio (HR), the risk of a major event prior to leaving the hospital was nearly threefold higher (HR 2.3; P < .0001) in the CS group.

Yet, there was no significant difference in the accumulation of adverse events after discharge. When compared for major events in the landmark analysis, the event curves were essentially superimposable from 30 days to 1 year. During this period, event rates were 19.3% versus 18.5% for CS and non-CS patients (HR 1.07; P = .2640).

The higher rate of events was unrelated to procedural complications, which were very low in both groups and did not differ significantly. Transition to open surgery, annular disruption, aortic dissection, coronary occlusion, and device embolization occurred in < 1% of patients in both groups.

Predictors of a poor outcome identified

On multivariate analysis, the predictors of events in the CS patients were comorbidities. Despite propensity matching, being on dialysis, having a permanent pacemaker, or having a mechanical assist device were all independent predictors of mortality risk specific to the CS group.

Age and baseline Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score were not predictors.

These risk factors deserve consideration when evaluating CS candidates for TAVR, but Dr. Dhoble said that none are absolute contraindications. Rather, he advised that they should be considered in the context of the entire clinical picture, including the expected benefit from TAVR. Indeed, the benefit-to-risk ratio generally favors TAVR in CS patients, particularly those with obstructive CS caused by aortic stenosis, according to Dr. Dhoble.

“Efforts should be made not only to avoid delaying TAVR in such patients but also to prevent CS by early definitive treatment of patients with aortic stenosis,” he said.

These data are useful and important, said Jonathan Schwartz, MD, medical director, interventional cardiology, Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C.

CS candidates for TAVR “are some of the sickest patients we treat. It is nice to finally have some data for this group,” he said. He agreed that CS patients can derive major benefit from TAVR if appropriately selected.

While many CS patients are already considered for TAVR, one source of hesitation has been the exclusion of CS patients from major TAVR trials, said Dr. Dhoble. He hopes these data will provide a framework for clinical decisions.

Ironically, the first TAVR patient and half of the initial series of 38 TAVR patients had CS, noted Alain G. Cribier, MD, director of cardiology, Charles Nicolle Hospital, University of Rouen, France. As the primary investigator of that initial TAVR study, conducted more than 20 years ago, he said he was not surprised by the favorable results of the propensity analysis.

“There is an almost miraculous clinical improvement to be achieved when you succeed with the procedure,” said Dr. Cribier, recounting his own experience. Improvements in LVEF of up to 30% can be achieved “within a day or two or even the first day,” he said.

Dr. Dhoble reports financial relationships with Abbott Vascular and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Schwartz reports that he has financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr. Cribier reports a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences.

FROM EUROPCR 2023

The antimicrobial peptide that even Pharma can love

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

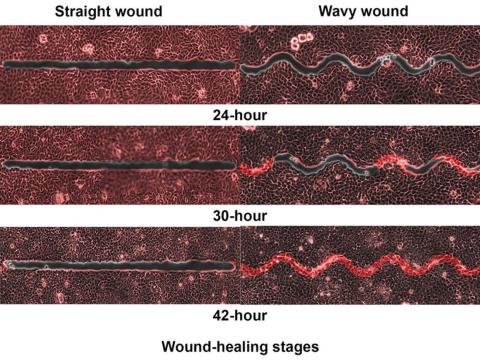

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.

They created synthetic wounds – some straight, some wavy – in micropatterned hydrogel substrates that mimicked human skin. Then they used an advanced optical technique known as particle image velocimetry to measure fluid flow and learn how cells moved to close the wound gaps.

The wavy wounds “induced more complex collective cell movements, such as a swirly, vortex-like motion,” according to the written statement from NTU Singapore. In the straight wounds, cell movements paralleled the wound front, “moving in straight lines like a marching band,” they pointed out, unlike some researchers who never call us unless they need money.

Complex epithelial cell movements are better, it turns out. Over an observation period of 64 hours the NTU team found that the healing efficiency of wavy gaps – measured by the area covered by the cells over time – is nearly five times faster than straight gaps.

The complex motion “enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps,” explained lead author Xu Hongmei, a doctoral student at NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, who seems to have time to toss out a tumblr or two to keep the press informed.

As for the rest of you, would it kill you to pick up a phone once in a while? Maybe let a journalist know that you’re still alive? We have feelings too, you know, and we worry.

A little Jekyll, a little Hyde, and a little shop of horrors

More “Little Shop of Horrors” references are coming, so be prepared.

We begin with Triphyophyllum peltatum. This woody vine is of great interest to medical and pharmaceutical researchers because its constituents have shown promise against pancreatic cancer and leukemia cells, among others, along with the pathogens that cause malaria and other diseases. There is another side, however. T. peltatum also has a tendency to turn into a realistic Audrey II when deprived.

No, of course they’re not craving human flesh, but it does become … carnivorous in its appetite.

T. peltatum, native to the West African tropics and not found in a New York florist shop, has the unique ability to change its diet and development based on the environmental circumstances. For some unknown reason, the leaves would develop adhesive traps in the form of sticky drops that capture insect prey. The plant is notoriously hard to grow, however, so no one could study the transformation under lab conditions. Until now.

A group of German scientists “exposed the plant to different stress factors, including deficiencies of various nutrients, and studied how it responded to each,” said Dr. Traud Winkelmann of Leibniz University Hannover. “Only in one case were we able to observe the formation of traps: in the case of a lack of phosphorus.”

Well, there you have it: phosphorus. We need it for healthy bones and teeth, which this plant doesn’t have to worry about, unlike its Tony Award–nominated counterpart. The investigators hope that their findings could lead to “future molecular analyses that will help understand the origins of carnivory,” but we’re guessing that a certain singing alien species will be left out of that research.

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.

They created synthetic wounds – some straight, some wavy – in micropatterned hydrogel substrates that mimicked human skin. Then they used an advanced optical technique known as particle image velocimetry to measure fluid flow and learn how cells moved to close the wound gaps.

The wavy wounds “induced more complex collective cell movements, such as a swirly, vortex-like motion,” according to the written statement from NTU Singapore. In the straight wounds, cell movements paralleled the wound front, “moving in straight lines like a marching band,” they pointed out, unlike some researchers who never call us unless they need money.

Complex epithelial cell movements are better, it turns out. Over an observation period of 64 hours the NTU team found that the healing efficiency of wavy gaps – measured by the area covered by the cells over time – is nearly five times faster than straight gaps.

The complex motion “enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps,” explained lead author Xu Hongmei, a doctoral student at NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, who seems to have time to toss out a tumblr or two to keep the press informed.

As for the rest of you, would it kill you to pick up a phone once in a while? Maybe let a journalist know that you’re still alive? We have feelings too, you know, and we worry.

A little Jekyll, a little Hyde, and a little shop of horrors

More “Little Shop of Horrors” references are coming, so be prepared.

We begin with Triphyophyllum peltatum. This woody vine is of great interest to medical and pharmaceutical researchers because its constituents have shown promise against pancreatic cancer and leukemia cells, among others, along with the pathogens that cause malaria and other diseases. There is another side, however. T. peltatum also has a tendency to turn into a realistic Audrey II when deprived.

No, of course they’re not craving human flesh, but it does become … carnivorous in its appetite.

T. peltatum, native to the West African tropics and not found in a New York florist shop, has the unique ability to change its diet and development based on the environmental circumstances. For some unknown reason, the leaves would develop adhesive traps in the form of sticky drops that capture insect prey. The plant is notoriously hard to grow, however, so no one could study the transformation under lab conditions. Until now.

A group of German scientists “exposed the plant to different stress factors, including deficiencies of various nutrients, and studied how it responded to each,” said Dr. Traud Winkelmann of Leibniz University Hannover. “Only in one case were we able to observe the formation of traps: in the case of a lack of phosphorus.”

Well, there you have it: phosphorus. We need it for healthy bones and teeth, which this plant doesn’t have to worry about, unlike its Tony Award–nominated counterpart. The investigators hope that their findings could lead to “future molecular analyses that will help understand the origins of carnivory,” but we’re guessing that a certain singing alien species will be left out of that research.

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.

They created synthetic wounds – some straight, some wavy – in micropatterned hydrogel substrates that mimicked human skin. Then they used an advanced optical technique known as particle image velocimetry to measure fluid flow and learn how cells moved to close the wound gaps.

The wavy wounds “induced more complex collective cell movements, such as a swirly, vortex-like motion,” according to the written statement from NTU Singapore. In the straight wounds, cell movements paralleled the wound front, “moving in straight lines like a marching band,” they pointed out, unlike some researchers who never call us unless they need money.

Complex epithelial cell movements are better, it turns out. Over an observation period of 64 hours the NTU team found that the healing efficiency of wavy gaps – measured by the area covered by the cells over time – is nearly five times faster than straight gaps.

The complex motion “enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps,” explained lead author Xu Hongmei, a doctoral student at NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, who seems to have time to toss out a tumblr or two to keep the press informed.

As for the rest of you, would it kill you to pick up a phone once in a while? Maybe let a journalist know that you’re still alive? We have feelings too, you know, and we worry.

A little Jekyll, a little Hyde, and a little shop of horrors

More “Little Shop of Horrors” references are coming, so be prepared.

We begin with Triphyophyllum peltatum. This woody vine is of great interest to medical and pharmaceutical researchers because its constituents have shown promise against pancreatic cancer and leukemia cells, among others, along with the pathogens that cause malaria and other diseases. There is another side, however. T. peltatum also has a tendency to turn into a realistic Audrey II when deprived.

No, of course they’re not craving human flesh, but it does become … carnivorous in its appetite.

T. peltatum, native to the West African tropics and not found in a New York florist shop, has the unique ability to change its diet and development based on the environmental circumstances. For some unknown reason, the leaves would develop adhesive traps in the form of sticky drops that capture insect prey. The plant is notoriously hard to grow, however, so no one could study the transformation under lab conditions. Until now.

A group of German scientists “exposed the plant to different stress factors, including deficiencies of various nutrients, and studied how it responded to each,” said Dr. Traud Winkelmann of Leibniz University Hannover. “Only in one case were we able to observe the formation of traps: in the case of a lack of phosphorus.”

Well, there you have it: phosphorus. We need it for healthy bones and teeth, which this plant doesn’t have to worry about, unlike its Tony Award–nominated counterpart. The investigators hope that their findings could lead to “future molecular analyses that will help understand the origins of carnivory,” but we’re guessing that a certain singing alien species will be left out of that research.

Redo-TAVR in U.S. database yields good news: Outcomes rival first intervention

Data support redo if needed.

Even after 3 years of follow-up, redo transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) performs about as well as the first procedure, whether compared for hard endpoints, such as death and stroke, or for softer endpoints, such as function and quality of life, new registry data suggest.

reported Rajendra Makkar, MD, associate director, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The results were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

Data for this analysis were drawn from 348,338 TAVR procedures with the Edwards balloon-expandable valves in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Replacement Registry.

Of these, 1,216 were redo procedures. In 475 of the cases, the redo was performed in a patient whose first procedure was with an Edwards device. In the remaining 741 cases, the Edwards device replaced a different prosthetic heart valve. The median time to the redo from the first procedure was 26 months.

For the analysis, the redo-TAVRs were compared with native TAVR patients through 1:1 propensity matching employing 35 covariates, such as age, body mass index (BMI), baseline comorbidities, prior cardiovascular procedures, valve size, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score.

Low death and stroke rates following TAVR redos

The rates of all-cause death or stroke within hospital (4.7% vs. 3.9%; P = .32) and at 30 days (6.1% vs. 5.9%; P = .77) were numerically but not statistically higher in the redo group.

At 1 year, the rates of death (17.3% vs. 17.7%; P = .961) and stroke (3.3% vs. 3.5%; P = .982) were numerically but not significantly lower among those who underwent a redo procedure.

The secondary endpoints told the same story. The one exception was the higher aortic valve reintervention rate (0.61% vs. 0.09%; P = .03) at 30 days in the redo group. This did reach statistical significance, but Dr. Makkar pointed out rates were very low regardless. The rates climbed in both groups by 1 year (1.09% vs. 0.21%; P = .01).

No other secondary endpoints differed significantly at 30 days or at 1 year. Even though some were numerically higher after redo at 1 year, such as major vascular complications (1.25 vs. 1.60; P = .51), others were lower, such as new-start dialysis (1.62 vs. 0.98; P = .26). All-cause readmission rates at 1 year were nearly identical (32.56% vs. 32.23%; P = .82).

Consistent with the comparable outcomes on the hard endpoints, major and similar improvements were seen in both the redo and the propensity-matched native TAVR patients on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Overall Summary. The slight advantage for the redo group was not significant at 30 days, but the degree of improvement was greater after the redo than after native TAVR at 1 year (15% vs. 10%; P = .03).

“You bring good news,” said Alain G. Cribier, MD, director of cardiology, Charles Nicolle Hospital, University of Rouen, France. Widely regarded as the father of TAVR for his first-in-human series in 2002, Dr. Cribier said that there are several reassuring take-home messages from this study.

“First, these data tell us that the redo rate is extremely low,” he said, noting that the registry data suggests a risk well below 1%. “Second, we are seeing from this data that there are no more complications [than TAVR in a native valve] if you need to do this.”

Redo patients are generally sicker

The propensity matching was designed to eliminate baseline differences for the outcome comparisons, but Dr. Makkar did point out that redo-TAVR patients were sicker than the native TAVR patients. For example, when compared prior to propensity matching, the STS score was higher (8.3 vs. 5.2; P < .01), more patients had atrial fibrillation (47.9% vs. 36.2%; P < .01), and more patients had a prior stroke (15.0% vs. 10.7%; P < .01).

The registry only has follow-up out to 1 year, but participating patients were matched to a claims database to capture outcomes out to 3 years. Mortality rates at long-term follow-up were not significantly different for redo vs. native TAVR (42.2% vs. 40.3% respectively; P = .98); for the entire dataset or when compared in subgroups defined by Edwards valve redo of an Edwards valve (P = .909) or an Edwards valve redo of a non-Edwards device (P = .871).

Whether an early redo, defined as 12 months after the index TAVR procedure, or a late redo, the rate of mortality ranged from approximately 16% to 18% with no significant difference between redo and native TAVR.

A moderator for the late-breaking trials session where these data were presented, Darren Mylotte, MD, a consultant in cardiology for the Galway University Hospitals, Ireland, challenged Dr. Makkar about the potential for selection bias. He said redo patients might be the ones that interventionalists feel confident about helping, making this comparison unrepresentative.

“I think that the selection bias is likely to cut both ways,” Dr. Makkar replied. For many patients with a failed TAVR, he explained that clinicians might think, “There is nothing to be done for this patient except to try a redo.”

Dr. Makkar reports financial relationships with Abbott, Cordis, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic. Dr. Cribier reports a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Mylotte reports no potential conflicts of interest.

Data support redo if needed.

Data support redo if needed.

Even after 3 years of follow-up, redo transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) performs about as well as the first procedure, whether compared for hard endpoints, such as death and stroke, or for softer endpoints, such as function and quality of life, new registry data suggest.

reported Rajendra Makkar, MD, associate director, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The results were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

Data for this analysis were drawn from 348,338 TAVR procedures with the Edwards balloon-expandable valves in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Replacement Registry.

Of these, 1,216 were redo procedures. In 475 of the cases, the redo was performed in a patient whose first procedure was with an Edwards device. In the remaining 741 cases, the Edwards device replaced a different prosthetic heart valve. The median time to the redo from the first procedure was 26 months.

For the analysis, the redo-TAVRs were compared with native TAVR patients through 1:1 propensity matching employing 35 covariates, such as age, body mass index (BMI), baseline comorbidities, prior cardiovascular procedures, valve size, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score.

Low death and stroke rates following TAVR redos

The rates of all-cause death or stroke within hospital (4.7% vs. 3.9%; P = .32) and at 30 days (6.1% vs. 5.9%; P = .77) were numerically but not statistically higher in the redo group.

At 1 year, the rates of death (17.3% vs. 17.7%; P = .961) and stroke (3.3% vs. 3.5%; P = .982) were numerically but not significantly lower among those who underwent a redo procedure.

The secondary endpoints told the same story. The one exception was the higher aortic valve reintervention rate (0.61% vs. 0.09%; P = .03) at 30 days in the redo group. This did reach statistical significance, but Dr. Makkar pointed out rates were very low regardless. The rates climbed in both groups by 1 year (1.09% vs. 0.21%; P = .01).

No other secondary endpoints differed significantly at 30 days or at 1 year. Even though some were numerically higher after redo at 1 year, such as major vascular complications (1.25 vs. 1.60; P = .51), others were lower, such as new-start dialysis (1.62 vs. 0.98; P = .26). All-cause readmission rates at 1 year were nearly identical (32.56% vs. 32.23%; P = .82).

Consistent with the comparable outcomes on the hard endpoints, major and similar improvements were seen in both the redo and the propensity-matched native TAVR patients on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Overall Summary. The slight advantage for the redo group was not significant at 30 days, but the degree of improvement was greater after the redo than after native TAVR at 1 year (15% vs. 10%; P = .03).

“You bring good news,” said Alain G. Cribier, MD, director of cardiology, Charles Nicolle Hospital, University of Rouen, France. Widely regarded as the father of TAVR for his first-in-human series in 2002, Dr. Cribier said that there are several reassuring take-home messages from this study.

“First, these data tell us that the redo rate is extremely low,” he said, noting that the registry data suggests a risk well below 1%. “Second, we are seeing from this data that there are no more complications [than TAVR in a native valve] if you need to do this.”

Redo patients are generally sicker

The propensity matching was designed to eliminate baseline differences for the outcome comparisons, but Dr. Makkar did point out that redo-TAVR patients were sicker than the native TAVR patients. For example, when compared prior to propensity matching, the STS score was higher (8.3 vs. 5.2; P < .01), more patients had atrial fibrillation (47.9% vs. 36.2%; P < .01), and more patients had a prior stroke (15.0% vs. 10.7%; P < .01).

The registry only has follow-up out to 1 year, but participating patients were matched to a claims database to capture outcomes out to 3 years. Mortality rates at long-term follow-up were not significantly different for redo vs. native TAVR (42.2% vs. 40.3% respectively; P = .98); for the entire dataset or when compared in subgroups defined by Edwards valve redo of an Edwards valve (P = .909) or an Edwards valve redo of a non-Edwards device (P = .871).

Whether an early redo, defined as 12 months after the index TAVR procedure, or a late redo, the rate of mortality ranged from approximately 16% to 18% with no significant difference between redo and native TAVR.

A moderator for the late-breaking trials session where these data were presented, Darren Mylotte, MD, a consultant in cardiology for the Galway University Hospitals, Ireland, challenged Dr. Makkar about the potential for selection bias. He said redo patients might be the ones that interventionalists feel confident about helping, making this comparison unrepresentative.

“I think that the selection bias is likely to cut both ways,” Dr. Makkar replied. For many patients with a failed TAVR, he explained that clinicians might think, “There is nothing to be done for this patient except to try a redo.”

Dr. Makkar reports financial relationships with Abbott, Cordis, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic. Dr. Cribier reports a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Mylotte reports no potential conflicts of interest.

Even after 3 years of follow-up, redo transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) performs about as well as the first procedure, whether compared for hard endpoints, such as death and stroke, or for softer endpoints, such as function and quality of life, new registry data suggest.

reported Rajendra Makkar, MD, associate director, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The results were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

Data for this analysis were drawn from 348,338 TAVR procedures with the Edwards balloon-expandable valves in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Replacement Registry.

Of these, 1,216 were redo procedures. In 475 of the cases, the redo was performed in a patient whose first procedure was with an Edwards device. In the remaining 741 cases, the Edwards device replaced a different prosthetic heart valve. The median time to the redo from the first procedure was 26 months.

For the analysis, the redo-TAVRs were compared with native TAVR patients through 1:1 propensity matching employing 35 covariates, such as age, body mass index (BMI), baseline comorbidities, prior cardiovascular procedures, valve size, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score.

Low death and stroke rates following TAVR redos

The rates of all-cause death or stroke within hospital (4.7% vs. 3.9%; P = .32) and at 30 days (6.1% vs. 5.9%; P = .77) were numerically but not statistically higher in the redo group.

At 1 year, the rates of death (17.3% vs. 17.7%; P = .961) and stroke (3.3% vs. 3.5%; P = .982) were numerically but not significantly lower among those who underwent a redo procedure.

The secondary endpoints told the same story. The one exception was the higher aortic valve reintervention rate (0.61% vs. 0.09%; P = .03) at 30 days in the redo group. This did reach statistical significance, but Dr. Makkar pointed out rates were very low regardless. The rates climbed in both groups by 1 year (1.09% vs. 0.21%; P = .01).

No other secondary endpoints differed significantly at 30 days or at 1 year. Even though some were numerically higher after redo at 1 year, such as major vascular complications (1.25 vs. 1.60; P = .51), others were lower, such as new-start dialysis (1.62 vs. 0.98; P = .26). All-cause readmission rates at 1 year were nearly identical (32.56% vs. 32.23%; P = .82).

Consistent with the comparable outcomes on the hard endpoints, major and similar improvements were seen in both the redo and the propensity-matched native TAVR patients on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Overall Summary. The slight advantage for the redo group was not significant at 30 days, but the degree of improvement was greater after the redo than after native TAVR at 1 year (15% vs. 10%; P = .03).

“You bring good news,” said Alain G. Cribier, MD, director of cardiology, Charles Nicolle Hospital, University of Rouen, France. Widely regarded as the father of TAVR for his first-in-human series in 2002, Dr. Cribier said that there are several reassuring take-home messages from this study.

“First, these data tell us that the redo rate is extremely low,” he said, noting that the registry data suggests a risk well below 1%. “Second, we are seeing from this data that there are no more complications [than TAVR in a native valve] if you need to do this.”

Redo patients are generally sicker

The propensity matching was designed to eliminate baseline differences for the outcome comparisons, but Dr. Makkar did point out that redo-TAVR patients were sicker than the native TAVR patients. For example, when compared prior to propensity matching, the STS score was higher (8.3 vs. 5.2; P < .01), more patients had atrial fibrillation (47.9% vs. 36.2%; P < .01), and more patients had a prior stroke (15.0% vs. 10.7%; P < .01).

The registry only has follow-up out to 1 year, but participating patients were matched to a claims database to capture outcomes out to 3 years. Mortality rates at long-term follow-up were not significantly different for redo vs. native TAVR (42.2% vs. 40.3% respectively; P = .98); for the entire dataset or when compared in subgroups defined by Edwards valve redo of an Edwards valve (P = .909) or an Edwards valve redo of a non-Edwards device (P = .871).

Whether an early redo, defined as 12 months after the index TAVR procedure, or a late redo, the rate of mortality ranged from approximately 16% to 18% with no significant difference between redo and native TAVR.

A moderator for the late-breaking trials session where these data were presented, Darren Mylotte, MD, a consultant in cardiology for the Galway University Hospitals, Ireland, challenged Dr. Makkar about the potential for selection bias. He said redo patients might be the ones that interventionalists feel confident about helping, making this comparison unrepresentative.

“I think that the selection bias is likely to cut both ways,” Dr. Makkar replied. For many patients with a failed TAVR, he explained that clinicians might think, “There is nothing to be done for this patient except to try a redo.”

Dr. Makkar reports financial relationships with Abbott, Cordis, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic. Dr. Cribier reports a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Mylotte reports no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM EUROPCR 2023

Docs fervently hope federal ban on noncompete clauses goes through

The Federal Trade Commission’s proposed regulation that would ban noncompete agreements across the country seems like potential good news for doctors. Of course, many hospitals and employers are against it. As a result, the FTC’s sweeping proposal has tongues wagging on both sides of the issue.

Many physicians are thrilled that they may soon have more control over their career and not be stuck in jobs where they feel frustrated, underpaid, or blocked in their progress.

As of 2018, as many as 45% of primary care physicians had inked such agreements with their employers.

Typically, the agreements prevent physicians from practicing medicine with a new employer for a defined period within a specific geographic area. No matter how attractive an alternate offer of employment might be, doctors are bound by the agreements to say no if the offer exists in that defined area and time period.

The period for public comment on the proposed regulation ended on April 19, and there is currently no set date for a decision.

In a Medscape poll of 558 physicians, more than 9 out of 10 respondents said that they were either currently bound by a noncompete clause or that they had been bound by one in the past that had forced them to temporarily stop working, commute long distances, move to a different area, or switch fields.

The new proposal would make it illegal for an employer, such as a hospital or large group, to enter a noncompete with a worker; maintain a noncompete with a worker; or represent to a worker, under certain circumstances, that the worker is subject to a noncompete.

It also would not only ban future noncompete agreements but also retroactively invalidate existing ones. The FTC reasons that noncompete clauses could potentially increase worker earnings as well as lower health care costs by billions of dollars. If the ruling were to move forward, it would represent part of President Biden’s “worker-forward” priorities, focusing on how competition can be a good thing for employees. The President billed the FTC’s announcement as a “huge win for workers.”

In its statements on the proposed ban, the FTC claimed that it could lower consumer prices across the board by as much as $150 billion per year and return nearly $300 million to workers each year.

However, even if passed, the draft rule would keep in place nonsolicitation rules that many health care organizations have put into place. That means that, if a physician leaves an employer, he or she cannot reach out to former patients and colleagues to bring them along or invite them to switch to him or her in the new job.

Within that clause, however, the FTC has specified that if such nonsolicitation agreement has the “equivalent effect” of a noncompete, the agency would deem it such. That means, even if that rule stays, it could be contested and may be interpreted as violating the noncompete law. So there’s value in reading all the fine print should the ban move forward.

Could the ban bring potential downsides?

Most physicians view the potential to break free of a noncompete agreement as a victory. Peter Glennon, an employment litigation attorney with The Glennon Law Firm in Rochester, N.Y., says not so fast. “If you ask anyone if they’d prefer a noncompete agreement, of course they’re going to say no,” he said in an interview. “It sounds like a restriction, one that can hold you back.”

Mr. Glennon believes that there are actually upsides to physician noncompetes. For instance, many noncompetes come with sign-on bonuses that could potentially disappear without the agreements. There’s also the fact that when some physicians sign a noncompete agreement, they then receive pro bono training and continuing education along with marketing and promotion of their skills. Without signing a noncompete, employers may be less incentivized to provide all those benefits to their physician employers.

Those benefits – and the noncompetes – also vary by specialty, Mr. Glennon said. “In 2021, Washington, DC, banned noncompetes for doctors making less than $250,000. So, most generalists there can walk across the street and get a new job. For specialists like cardiologists or neurosurgeons, however, advanced training and marketing benefits matter, so many of them don’t want to lose noncompetes.”

Still, most physicians hope that the FTC’s ban takes hold. Manan Shah, MD, founder, and chief medical officer at Wyndly, an allergy relief startup practice, is one of them.

“Initially, it might disincentivize hospital systems from helping new physicians build up their name and practice because they might be concerned about a physician leaving and starting anew,” he said. “But in the long term, hospitals require physicians to bring their patients to them for care, so the best hospitals will always compete for the best physicians and support them as they build up their practice.”

Dr. Shah views noncompetes as overly prohibitive to physicians. “Right now, if a physician starts a job at a large hospital system and realizes they want to switch jobs, the noncompete distances are so wide they often have to move cities to continue practicing,” he said. “Picking up and starting over in a new city isn’t an option for everyone and can be especially difficult for someone with a family.”

Where Mr. Glennon argued that a physician leaving a team-based practice might harm patients, Shah takes a different perspective. “Imagine you have a doctor whom you trust and have been working with,” he said. “If something changes at their hospital and they decide to move, you literally have to find a new doctor instead of just being able to see them at another location down the street.”

Another potential burden of the noncompete agreements is that they could possibly squelch doctor’s desires to hang up their own shingle. According to Dr. Shah, the agreements make it so that if a physician wants to work independently, it’s nearly impossible to fly solo. “This is frustrating because independent practices have been shown to be more cost effective and allow patients to build better relationships with their doctors,” he claimed.

A 2016 study from Annals of Family Medicine supports that claim, at least for small general practices. Another study appearing in JAMA concurred. It does point out, however, that the cost equation is nuanced and that benefits of larger systems include more resilience to economic downturns and can provide more specialized care.

Will nonprofit hospitals be subject to this noncompete ban?

Further complicating the noncompete ban issue is how it might impact nonprofit institutions versus their for-profit peers. Most hospitals structured as nonprofits would be exempt from the rule because the FTC Act provides that it can enforce against “persons, partnerships, or corporations,” which are further defined as entities “organized to carry on business for their own profit or that of their members.”

The fallout from this, said Dr. Shah, is that it “would disproportionately affect health care providers, since many hospital systems are nonprofits. This is disconcerting because we know that many nonprofit systems make large profits anyway and can offer executive teams’ lucrative packages, while the nurses, assistants, and physicians providing the care are generally not well compensated.”

So far, about nine states plus Washington, D.C., have already put noncompete bans in place, and they may serve as a harbinger of things to come should the federal ban go into effect. Each varies in its specifics. Some, like Indiana, outright ban them, whereas others limit them based on variables like income and industry. “We’re seeing these states responding to local market conditions,” said Darryl Drevna, senior director of regulatory affairs at the American Medical Group Association. “Health care is a hyperlocal market. Depending on the situation, the bans adapt and respond specific to those states.”

Should the federal ban take hold, however, it will supersede whatever rules the individual states have in place.

Some opponents of the federal ban proposal question its authority to begin with, however, Mr. Glennon included. “Many people believe the FTC is overstepping,” he said. “Some people believe that Section 5 of the FTC Act does not give it the authority to police labor markets.”

Mr. Drevna noted that the FTC has taken an aggressive stance, one that will ultimately wind up in the courts. “How it works out is anyone’s guess,” he said. “Ideally, the FTC will consider the comments and concerns of groups like AMGA and realize that states are best suited to regulate in this area.”