User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

International Pemphigus and Pemphigoid Foundation

In May 2018, the IPPF will bring together pemphigus and pemphigoid patients, clinicians, researchers, and industry partners to focus on ongoing or future clinical trials and their underlying science. This will take place prior to the International Investigative Dermatology meeting in Orlando. More.

In May 2018, the IPPF will bring together pemphigus and pemphigoid patients, clinicians, researchers, and industry partners to focus on ongoing or future clinical trials and their underlying science. This will take place prior to the International Investigative Dermatology meeting in Orlando. More.

In May 2018, the IPPF will bring together pemphigus and pemphigoid patients, clinicians, researchers, and industry partners to focus on ongoing or future clinical trials and their underlying science. This will take place prior to the International Investigative Dermatology meeting in Orlando. More.

Ehlers-Danlos Society

The Ehlers-Danlos Society will hold an International Symposium Sept. 26-29, 2018, in Ghent, Belgium. Clinicians and researchers are encouraged to attend to discuss the molecular, pathogenic, clinical, and management aspects of all types of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. More.

The Ehlers-Danlos Society will hold an International Symposium Sept. 26-29, 2018, in Ghent, Belgium. Clinicians and researchers are encouraged to attend to discuss the molecular, pathogenic, clinical, and management aspects of all types of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. More.

The Ehlers-Danlos Society will hold an International Symposium Sept. 26-29, 2018, in Ghent, Belgium. Clinicians and researchers are encouraged to attend to discuss the molecular, pathogenic, clinical, and management aspects of all types of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. More.

Dup 15q Alliance

Join the Dup 15q Alliance and the Angelman Syndrome Research Foundation August 6-7, 2018, for world-class scientific, translational, and clinical presentations. This symposium allows for the sharing of unpublished work, which leads to conceptual discussions and helps to accelerate therapeutic opportunities for both disorders. More.

Join the Dup 15q Alliance and the Angelman Syndrome Research Foundation August 6-7, 2018, for world-class scientific, translational, and clinical presentations. This symposium allows for the sharing of unpublished work, which leads to conceptual discussions and helps to accelerate therapeutic opportunities for both disorders. More.

Join the Dup 15q Alliance and the Angelman Syndrome Research Foundation August 6-7, 2018, for world-class scientific, translational, and clinical presentations. This symposium allows for the sharing of unpublished work, which leads to conceptual discussions and helps to accelerate therapeutic opportunities for both disorders. More.

Perianal Extramammary Paget Disease Treated With Topical Imiquimod and Oral Cimetidine

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

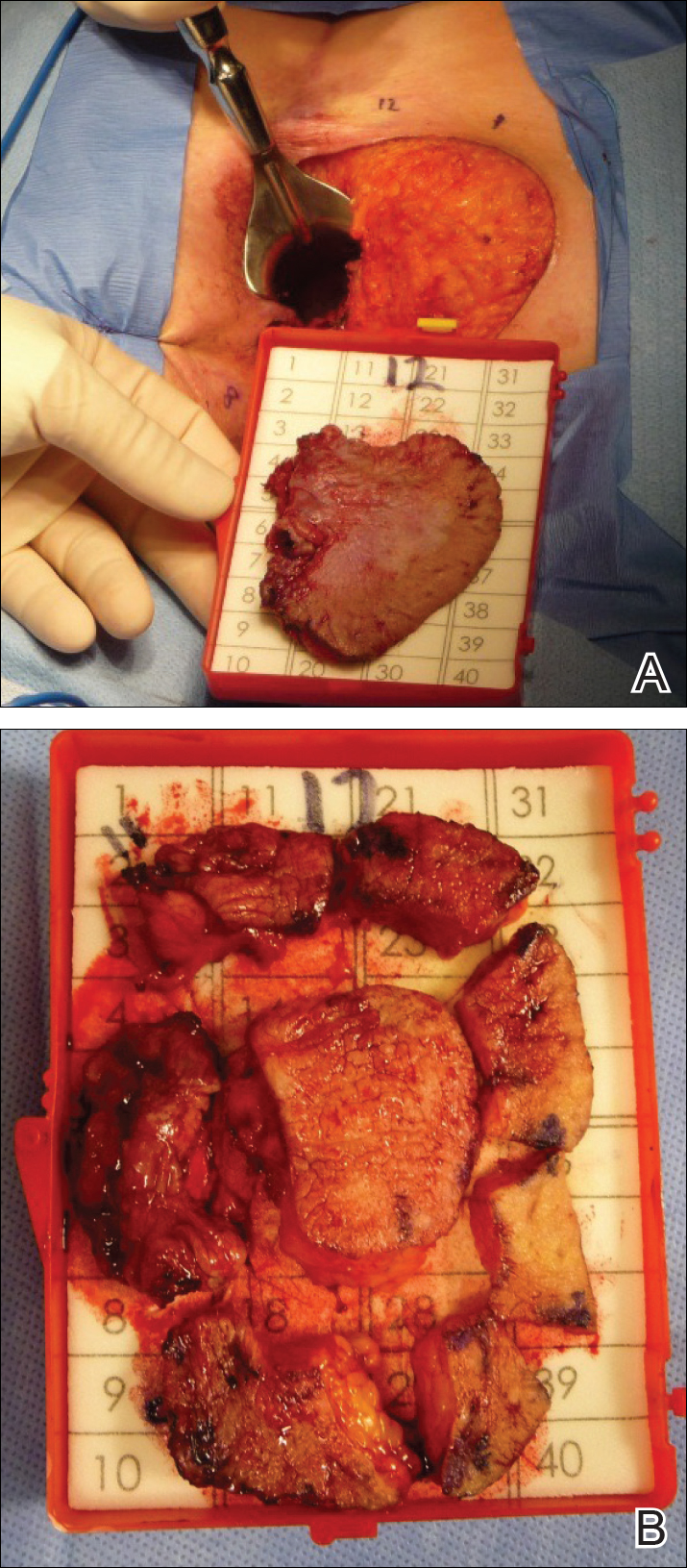

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

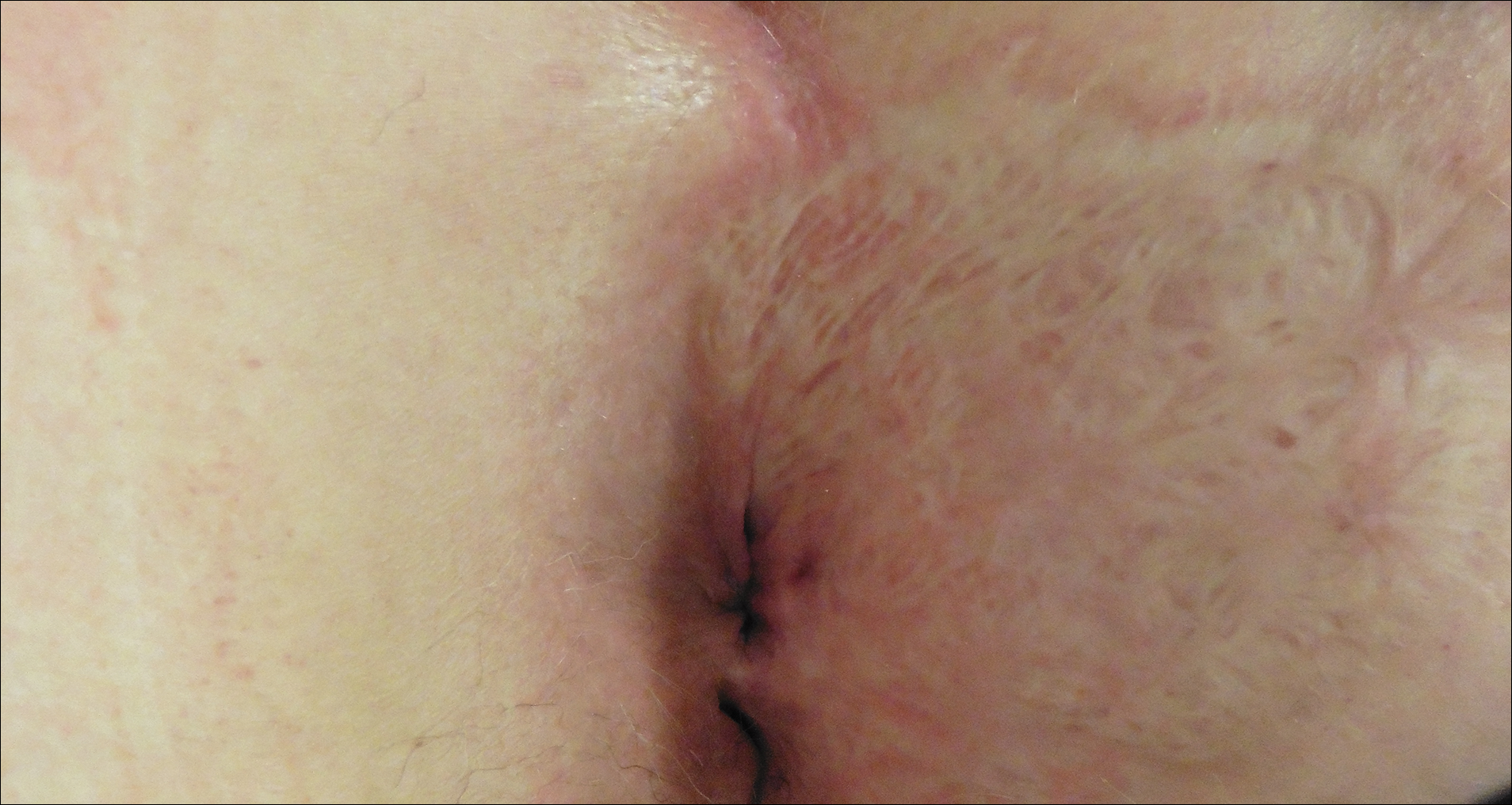

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

Resident Pearls

- Topical imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine can be a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with perianal extramammary Paget disease (EMPD).

- Its antineoplastic and immunomodulatory properties may suggest a role for oral cimetidine as an adjuvant therapy in the treatment of perianal EMPD.

Cure SMA

Cure SMA is conducting a survey of pediatricians to assess baseline awareness regarding spinal muscular atrophy. Support Cure SMA and take the survey! More.

Cure SMA is conducting a survey of pediatricians to assess baseline awareness regarding spinal muscular atrophy. Support Cure SMA and take the survey! More.

Cure SMA is conducting a survey of pediatricians to assess baseline awareness regarding spinal muscular atrophy. Support Cure SMA and take the survey! More.

CurePSP

The First International Symposium on PSP and CBD will take place in London Oct. 25-26, 2018, in conjunction with CurePSP and the PSP Association. The latest research updates will be shared through scientific and clinical presentations and poster sessions. View a draft agenda and register now. CurePSP sponsors and organizes family conferences around the US, providing opportunities to learn more about PSP, CBD, and MSA. Join CurePSP and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MD, on June 29-30, 2018. More.

The First International Symposium on PSP and CBD will take place in London Oct. 25-26, 2018, in conjunction with CurePSP and the PSP Association. The latest research updates will be shared through scientific and clinical presentations and poster sessions. View a draft agenda and register now. CurePSP sponsors and organizes family conferences around the US, providing opportunities to learn more about PSP, CBD, and MSA. Join CurePSP and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MD, on June 29-30, 2018. More.

The First International Symposium on PSP and CBD will take place in London Oct. 25-26, 2018, in conjunction with CurePSP and the PSP Association. The latest research updates will be shared through scientific and clinical presentations and poster sessions. View a draft agenda and register now. CurePSP sponsors and organizes family conferences around the US, providing opportunities to learn more about PSP, CBD, and MSA. Join CurePSP and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MD, on June 29-30, 2018. More.

Cornelia de Lange Syndrome (CdLS) Foundation

Register now for the 8th Biennial CdLS Scientific and Educational Symposium to be held in Minneapolis on June 27-28, 2018. The program will feature talks by leading researchers. To submit an abstract, contact Amy Kimball at [email protected]. More.

Register now for the 8th Biennial CdLS Scientific and Educational Symposium to be held in Minneapolis on June 27-28, 2018. The program will feature talks by leading researchers. To submit an abstract, contact Amy Kimball at [email protected]. More.

Register now for the 8th Biennial CdLS Scientific and Educational Symposium to be held in Minneapolis on June 27-28, 2018. The program will feature talks by leading researchers. To submit an abstract, contact Amy Kimball at [email protected]. More.

Children’s Cardiomyopathy Foundation

The Children’s Cardiomyopathy Foundation offers a research grant program for studies focused on all forms of cardiomyopathy in children. Letters of intent are due June 13, 2018. More.

The Children’s Cardiomyopathy Foundation offers a research grant program for studies focused on all forms of cardiomyopathy in children. Letters of intent are due June 13, 2018. More.

The Children’s Cardiomyopathy Foundation offers a research grant program for studies focused on all forms of cardiomyopathy in children. Letters of intent are due June 13, 2018. More.

Aplastic Anemia and MDS International Foundation (AAMDSIF)

AAMDSIF will be hosting seven “Living with Aplastic Anemia, MDS, PNH” patient and family conferences in cities around the country this year. Each free event offers opportunities to learn from leading medical experts and to connect with other patients and caregivers. More.

AAMDSIF will be hosting seven “Living with Aplastic Anemia, MDS, PNH” patient and family conferences in cities around the country this year. Each free event offers opportunities to learn from leading medical experts and to connect with other patients and caregivers. More.

AAMDSIF will be hosting seven “Living with Aplastic Anemia, MDS, PNH” patient and family conferences in cities around the country this year. Each free event offers opportunities to learn from leading medical experts and to connect with other patients and caregivers. More.