User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

A practical approach to interviewing a somatizing patient

Somatization is the experience of psychological distress in the form of bodil

Collecting a detailed history of physical symptoms can help the patient feel that you are listening to him (her) and that the chief concern is important. A detailed review of psychiatric symptoms (eg, hallucinations, paranoia, suicidality, etc.) should be deferred until later in the examination. Asking questions relating to psychiatric symptoms early could lead to further resistance by reinforcing negative preconceptions that the patient might have regarding mental illness.

Explicitly express empathy regarding physical symptoms throughout the interview to acknowledge any real suffering the patient is experiencing and to contradict any notion that psychiatric evaluation implies that the suffering could be imaginary.

Ask, “How has this illness affected your life?” This question helps make the connection between the patient’s physical state and social milieu. If somatization is confirmed, then the provider should assist the patient in reversing the arrow of causation. Although the ultimate goal is for the patient to understand how his (her) life has affected the symptoms, simply understanding that there are connections between the two is a start toward this goal.1

Explore the response to the previous question. Expand upon it to elicit a detailed social history, listening for any social stressors.

Obtain family and personal histories of allergies, substance abuse, and medical or psychiatric illness.

Review psychiatric symptoms. Make questions less jarring2 by adapting them to the patient’s situation, such as “Has your illness become so painful that at times you don’t even want to live?”

Perform cognitive and physical examinations. Conducting a physical examination could further reassure the patient that you are not ignoring physical complaints.

Educate the patient that the mind and body are connected and emotions affect how one feels physically. Use examples, such as “When I feel anxious, my heart beats faster” or “A headache might hurt more at work than at the beach.”

Elicit feedback and questions from the patient.

Discuss your treatment plan with the patient. Resistant patients with confirmed somatization disorders might accept psychiatric care as a means of dealing with the stress or pain of their physical symptoms.

Consider asking:

- What would you be doing if you weren’t in the hospital right now?

- Aside from your health, what’s the biggest challenge in your life?

- Everything has a good side and a bad side. Is there anything positive about dealing with your illness? Providing the patient with an example of negative aspects of a good thing (such as the calories in ice cream, the high cost of gold, etc.) can help make this point.

- What would your life look like if you didn’t have these symptoms?

1. Creed F, Guthrie E. Techniques for interviewing the somatising patient. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:467-471.

2. Carlat DJ. The psychiatric interview: a practical guide. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2005.

Somatization is the experience of psychological distress in the form of bodil

Collecting a detailed history of physical symptoms can help the patient feel that you are listening to him (her) and that the chief concern is important. A detailed review of psychiatric symptoms (eg, hallucinations, paranoia, suicidality, etc.) should be deferred until later in the examination. Asking questions relating to psychiatric symptoms early could lead to further resistance by reinforcing negative preconceptions that the patient might have regarding mental illness.

Explicitly express empathy regarding physical symptoms throughout the interview to acknowledge any real suffering the patient is experiencing and to contradict any notion that psychiatric evaluation implies that the suffering could be imaginary.

Ask, “How has this illness affected your life?” This question helps make the connection between the patient’s physical state and social milieu. If somatization is confirmed, then the provider should assist the patient in reversing the arrow of causation. Although the ultimate goal is for the patient to understand how his (her) life has affected the symptoms, simply understanding that there are connections between the two is a start toward this goal.1

Explore the response to the previous question. Expand upon it to elicit a detailed social history, listening for any social stressors.

Obtain family and personal histories of allergies, substance abuse, and medical or psychiatric illness.

Review psychiatric symptoms. Make questions less jarring2 by adapting them to the patient’s situation, such as “Has your illness become so painful that at times you don’t even want to live?”

Perform cognitive and physical examinations. Conducting a physical examination could further reassure the patient that you are not ignoring physical complaints.

Educate the patient that the mind and body are connected and emotions affect how one feels physically. Use examples, such as “When I feel anxious, my heart beats faster” or “A headache might hurt more at work than at the beach.”

Elicit feedback and questions from the patient.

Discuss your treatment plan with the patient. Resistant patients with confirmed somatization disorders might accept psychiatric care as a means of dealing with the stress or pain of their physical symptoms.

Consider asking:

- What would you be doing if you weren’t in the hospital right now?

- Aside from your health, what’s the biggest challenge in your life?

- Everything has a good side and a bad side. Is there anything positive about dealing with your illness? Providing the patient with an example of negative aspects of a good thing (such as the calories in ice cream, the high cost of gold, etc.) can help make this point.

- What would your life look like if you didn’t have these symptoms?

Somatization is the experience of psychological distress in the form of bodil

Collecting a detailed history of physical symptoms can help the patient feel that you are listening to him (her) and that the chief concern is important. A detailed review of psychiatric symptoms (eg, hallucinations, paranoia, suicidality, etc.) should be deferred until later in the examination. Asking questions relating to psychiatric symptoms early could lead to further resistance by reinforcing negative preconceptions that the patient might have regarding mental illness.

Explicitly express empathy regarding physical symptoms throughout the interview to acknowledge any real suffering the patient is experiencing and to contradict any notion that psychiatric evaluation implies that the suffering could be imaginary.

Ask, “How has this illness affected your life?” This question helps make the connection between the patient’s physical state and social milieu. If somatization is confirmed, then the provider should assist the patient in reversing the arrow of causation. Although the ultimate goal is for the patient to understand how his (her) life has affected the symptoms, simply understanding that there are connections between the two is a start toward this goal.1

Explore the response to the previous question. Expand upon it to elicit a detailed social history, listening for any social stressors.

Obtain family and personal histories of allergies, substance abuse, and medical or psychiatric illness.

Review psychiatric symptoms. Make questions less jarring2 by adapting them to the patient’s situation, such as “Has your illness become so painful that at times you don’t even want to live?”

Perform cognitive and physical examinations. Conducting a physical examination could further reassure the patient that you are not ignoring physical complaints.

Educate the patient that the mind and body are connected and emotions affect how one feels physically. Use examples, such as “When I feel anxious, my heart beats faster” or “A headache might hurt more at work than at the beach.”

Elicit feedback and questions from the patient.

Discuss your treatment plan with the patient. Resistant patients with confirmed somatization disorders might accept psychiatric care as a means of dealing with the stress or pain of their physical symptoms.

Consider asking:

- What would you be doing if you weren’t in the hospital right now?

- Aside from your health, what’s the biggest challenge in your life?

- Everything has a good side and a bad side. Is there anything positive about dealing with your illness? Providing the patient with an example of negative aspects of a good thing (such as the calories in ice cream, the high cost of gold, etc.) can help make this point.

- What would your life look like if you didn’t have these symptoms?

1. Creed F, Guthrie E. Techniques for interviewing the somatising patient. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:467-471.

2. Carlat DJ. The psychiatric interview: a practical guide. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2005.

1. Creed F, Guthrie E. Techniques for interviewing the somatising patient. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:467-471.

2. Carlat DJ. The psychiatric interview: a practical guide. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2005.

Should you recommend acupuncture to patients with substance use disorders?

Acupuncture is an ancient therapeutic tool known to be the core of traditional Chinese medicine. Two theories suggest positive outcomes in patients treated with acupuncture:

- The oxidative stress reduction theory states that a “large body of evidences demonstrated that acupuncture has [an] antioxidative effect in various diseases, but the exact mechanism remains unclear.”1

- The neurophysiological theory states that “acupuncture stimulation can facilitate the release of certain neuropeptides in the CNS, eliciting profound physiological effects and even activating self-healing mechanisms.”2

For decades, acupuncture has been used for addiction management. Here we provide information on its utility for patients with substance use disorders.

Opioid use disorder. Multiple studies have looked at withdrawal, comorbid mood disorders, and its management with acupuncture alone or in combination with psychotherapy and/or opioid agonists. Studies from Asia reported good treatment outcomes but had low-method quality.3 Western studies had superior method quality but found that acupuncture was no better than placebo as monotherapy. When acupuncture is combined with psychotherapy and an opioid agonist, treatment results are promising, showing faster taper of medications (methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone) with fewer adverse effects.

Cocaine use disorder. Most studies had poor treatment outcomes of acupuncture over placebo and were of low quality. A number of small studies were promising and found that patients treated with acupuncture were most likely to have a negative urine drug screen.3 Although acupuncture is widely used in the United States to treat cocaine dependence, evidence does not confirm its efficacy.

Tobacco use disorder. A small group of studies favored acupuncture for smoking cessation.3 Other studies reported no benefit compared with placebo or neutral results. Some studies agreed that any intervention (acupuncture or sham acupuncture) with good results is better than no intervention at all.

Alcohol use disorder. Almost no advantage over placebo was found. Studies with significant findings were in small populations.3

Amphetamine, Cannabis, and other hallucinogen use disorders. Available data on stimulants were too limited to be relevant. No studies were found on Cannabis and hallucinogens.

Further studies are needed

There is a lack of conclusive, good quality studies supporting acupuncture’s benefits in treating substance abuse. Acupuncture has been known to lack adverse effects other than those related to needle manipulation, which is dependent on the methods (depth of needle insertion, accurate anatomical location, angle, etc.). Because this treatment option is virtually side-effect free, inexpensive, with positive synergistic results, more high-method quality studies are needed to consider it for our patients.

1. Zeng XH, Li QQ, Xu Q, et al. Acupuncture mechanism and redox equilibrium. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. 2014;2014:483294. doi: 10.1155/2014/483294

2. Bai L, Lao L. Neurobiological foundations of acupuncture: the relevance and future prospect based on neuroimaging evidence. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. 2013;2013:812568. doi: 10.1155/2013/812568.

3. Boyuan Z, Yang C, Ke C, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for psychological symptoms associated with opioid addiction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. 2014;2014:313549. doi: 10.1155/2014/313549.

Acupuncture is an ancient therapeutic tool known to be the core of traditional Chinese medicine. Two theories suggest positive outcomes in patients treated with acupuncture:

- The oxidative stress reduction theory states that a “large body of evidences demonstrated that acupuncture has [an] antioxidative effect in various diseases, but the exact mechanism remains unclear.”1

- The neurophysiological theory states that “acupuncture stimulation can facilitate the release of certain neuropeptides in the CNS, eliciting profound physiological effects and even activating self-healing mechanisms.”2

For decades, acupuncture has been used for addiction management. Here we provide information on its utility for patients with substance use disorders.

Opioid use disorder. Multiple studies have looked at withdrawal, comorbid mood disorders, and its management with acupuncture alone or in combination with psychotherapy and/or opioid agonists. Studies from Asia reported good treatment outcomes but had low-method quality.3 Western studies had superior method quality but found that acupuncture was no better than placebo as monotherapy. When acupuncture is combined with psychotherapy and an opioid agonist, treatment results are promising, showing faster taper of medications (methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone) with fewer adverse effects.

Cocaine use disorder. Most studies had poor treatment outcomes of acupuncture over placebo and were of low quality. A number of small studies were promising and found that patients treated with acupuncture were most likely to have a negative urine drug screen.3 Although acupuncture is widely used in the United States to treat cocaine dependence, evidence does not confirm its efficacy.

Tobacco use disorder. A small group of studies favored acupuncture for smoking cessation.3 Other studies reported no benefit compared with placebo or neutral results. Some studies agreed that any intervention (acupuncture or sham acupuncture) with good results is better than no intervention at all.

Alcohol use disorder. Almost no advantage over placebo was found. Studies with significant findings were in small populations.3

Amphetamine, Cannabis, and other hallucinogen use disorders. Available data on stimulants were too limited to be relevant. No studies were found on Cannabis and hallucinogens.

Further studies are needed

There is a lack of conclusive, good quality studies supporting acupuncture’s benefits in treating substance abuse. Acupuncture has been known to lack adverse effects other than those related to needle manipulation, which is dependent on the methods (depth of needle insertion, accurate anatomical location, angle, etc.). Because this treatment option is virtually side-effect free, inexpensive, with positive synergistic results, more high-method quality studies are needed to consider it for our patients.

Acupuncture is an ancient therapeutic tool known to be the core of traditional Chinese medicine. Two theories suggest positive outcomes in patients treated with acupuncture:

- The oxidative stress reduction theory states that a “large body of evidences demonstrated that acupuncture has [an] antioxidative effect in various diseases, but the exact mechanism remains unclear.”1

- The neurophysiological theory states that “acupuncture stimulation can facilitate the release of certain neuropeptides in the CNS, eliciting profound physiological effects and even activating self-healing mechanisms.”2

For decades, acupuncture has been used for addiction management. Here we provide information on its utility for patients with substance use disorders.

Opioid use disorder. Multiple studies have looked at withdrawal, comorbid mood disorders, and its management with acupuncture alone or in combination with psychotherapy and/or opioid agonists. Studies from Asia reported good treatment outcomes but had low-method quality.3 Western studies had superior method quality but found that acupuncture was no better than placebo as monotherapy. When acupuncture is combined with psychotherapy and an opioid agonist, treatment results are promising, showing faster taper of medications (methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone) with fewer adverse effects.

Cocaine use disorder. Most studies had poor treatment outcomes of acupuncture over placebo and were of low quality. A number of small studies were promising and found that patients treated with acupuncture were most likely to have a negative urine drug screen.3 Although acupuncture is widely used in the United States to treat cocaine dependence, evidence does not confirm its efficacy.

Tobacco use disorder. A small group of studies favored acupuncture for smoking cessation.3 Other studies reported no benefit compared with placebo or neutral results. Some studies agreed that any intervention (acupuncture or sham acupuncture) with good results is better than no intervention at all.

Alcohol use disorder. Almost no advantage over placebo was found. Studies with significant findings were in small populations.3

Amphetamine, Cannabis, and other hallucinogen use disorders. Available data on stimulants were too limited to be relevant. No studies were found on Cannabis and hallucinogens.

Further studies are needed

There is a lack of conclusive, good quality studies supporting acupuncture’s benefits in treating substance abuse. Acupuncture has been known to lack adverse effects other than those related to needle manipulation, which is dependent on the methods (depth of needle insertion, accurate anatomical location, angle, etc.). Because this treatment option is virtually side-effect free, inexpensive, with positive synergistic results, more high-method quality studies are needed to consider it for our patients.

1. Zeng XH, Li QQ, Xu Q, et al. Acupuncture mechanism and redox equilibrium. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. 2014;2014:483294. doi: 10.1155/2014/483294

2. Bai L, Lao L. Neurobiological foundations of acupuncture: the relevance and future prospect based on neuroimaging evidence. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. 2013;2013:812568. doi: 10.1155/2013/812568.

3. Boyuan Z, Yang C, Ke C, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for psychological symptoms associated with opioid addiction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. 2014;2014:313549. doi: 10.1155/2014/313549.

1. Zeng XH, Li QQ, Xu Q, et al. Acupuncture mechanism and redox equilibrium. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. 2014;2014:483294. doi: 10.1155/2014/483294

2. Bai L, Lao L. Neurobiological foundations of acupuncture: the relevance and future prospect based on neuroimaging evidence. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. 2013;2013:812568. doi: 10.1155/2013/812568.

3. Boyuan Z, Yang C, Ke C, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for psychological symptoms associated with opioid addiction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement and Alternat Med. 2014;2014:313549. doi: 10.1155/2014/313549.

Impact of an inspirational training director on a resident’s life

The term psychiatry is derived from the Greek words “pskhe” and “iatreia” which mean “healing of the soul.”1 The desire to heal souls from different ethnicities, religions, and languages can be overwhelming for a trainee resident who is new to U.S. culture. The fear of having difficulty in building rapport with patients because of cultural bias and the dread of not understanding accents, slang, jokes, and nonverbal communication can be so frustrating that it overrides the intense desire of becoming an empathetic and successful physician.2 Du

I started my residency training in 2014 without any substantial scholarly work in my background or clinical experience in the United States. However, I had a great learning experience at my training program and would like to express my gratitude by recognizing my program director’s (Panagiota Korenis, MD) role in helping me accomplish my career goals. She believed in me when I was not able to believe in myself, and helped me overcome a helpless feeling of isolation and desperation during my intern year. Because of her mentorship and supervision, I presented 20 posters and oral presentations; published 5 works; drafted guidelines for training residents, including course material on the health care disparities faced by the Lesbian, Gay Bisexual, Transgender, Queer community; created a tool to predict readmissions in an inpatient psychiatric setting; received many prestigious awards, including Resident of the Year, a Certificate of Academic Excellence, a Young Scholar Award, and an American Psychiatric Association Diversity Leadership Fellowship for 2017-2019; and was accepted for a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship in one of my dream programs, Boston Children’s Hospital.

I strongly believe that the impact of an inspiring, motivating, and encouraging program director on a resident’s life is monumental. Here are some of the qualities I believe make a great program director who can significantly transform a trainee’s life:

A positive attitude.

- Encourage trainees to believe in their abilities, even if they stumble.

- Unleash and nurture their talents, and help them recognize their strengths and confidence.

- Foster a warm, welcoming, and supportive environment that enables residents to strive to reach their potential and goals.

- Boost confidence, acknowledge genuine efforts, and praise achievements.

- Encourage involvement in future projects.

Empathy and generosity.

- Treat residents with respect and care, while recognizing their strengths and weaknesses.

- Understand them at both a professional and personal level.

- Support meaningful and suitable projects that residents are passionate about and at which they excel.

- Influence residents by helping them understand the impact they have on patients and the program.

- Demonstrate sensitivity to the individual needs of each resident and provide constructive feedback.

Easy accessibility.

- Build good rapport with residents.

- Listen carefully to the residents’ ideas and feedback.

- Reassure residents that they can ask any questions or raise any issues they want to address.

Leadership.

- Color/BlackUndertake a leadership role within multidisciplinary teams, and collaborate effectively with other medical specialties for continuity of care, mutual support, Color/Blackand interdisciplinary education and communication.

- Assert authority when needed, and make important decisions for the program.

- Manage conflicts effectively and timely.

- Strictly monitor duty hours.3

Education.

- Design an educational curriculum relevant to all clinical settings.

- Provide protected time for didactics and scholarlyColor/Black activities.

- Ensure that residents develop a comprehensive understanding of the field.

- Actively involve residents in teaching, and modify the curriculum based on residents’ input and feedback.

- Schedule classes for in-service exams (eg, Psychiatry Residency In-Service Training Exam) and for the board exam preparation.4

- Promote residents’ autonomy and sense of competence.

Promote residents well-being.

- Encourage a work–life balance.

- Focus on team building and communication, and organize process groups.

- Adopt innovative ways to enable residents in managing stress.

- Organize social events and group activities, and provide support groups.

- Ensure adequate sleep hours and time away from work to prevent burnout.

Career development.

- Provide career guidance, and connect residents to appropriate resources for further professional development.

- Recognize that mentoring is a lifelong activity that does not end with the completion of residency training.

1. Gilman DC, Peck HT, Colby FM, eds. The new international encyclopedia. Vol 16. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead and Company; 2000:505.

2. Saeed F, Majeed MH, Kousar N. Easing international medical graduates’ entry into US training. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):269.

3. Johnson V. A resitern’s reflection on duty-hours reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):2278-2279.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Defining the key elements of an optimal residency program. https://www.aamc.org/download/84544/data/definekeyelements.pdf. Published May 2001. Accessed June 7, 2017.

The term psychiatry is derived from the Greek words “pskhe” and “iatreia” which mean “healing of the soul.”1 The desire to heal souls from different ethnicities, religions, and languages can be overwhelming for a trainee resident who is new to U.S. culture. The fear of having difficulty in building rapport with patients because of cultural bias and the dread of not understanding accents, slang, jokes, and nonverbal communication can be so frustrating that it overrides the intense desire of becoming an empathetic and successful physician.2 Du

I started my residency training in 2014 without any substantial scholarly work in my background or clinical experience in the United States. However, I had a great learning experience at my training program and would like to express my gratitude by recognizing my program director’s (Panagiota Korenis, MD) role in helping me accomplish my career goals. She believed in me when I was not able to believe in myself, and helped me overcome a helpless feeling of isolation and desperation during my intern year. Because of her mentorship and supervision, I presented 20 posters and oral presentations; published 5 works; drafted guidelines for training residents, including course material on the health care disparities faced by the Lesbian, Gay Bisexual, Transgender, Queer community; created a tool to predict readmissions in an inpatient psychiatric setting; received many prestigious awards, including Resident of the Year, a Certificate of Academic Excellence, a Young Scholar Award, and an American Psychiatric Association Diversity Leadership Fellowship for 2017-2019; and was accepted for a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship in one of my dream programs, Boston Children’s Hospital.

I strongly believe that the impact of an inspiring, motivating, and encouraging program director on a resident’s life is monumental. Here are some of the qualities I believe make a great program director who can significantly transform a trainee’s life:

A positive attitude.

- Encourage trainees to believe in their abilities, even if they stumble.

- Unleash and nurture their talents, and help them recognize their strengths and confidence.

- Foster a warm, welcoming, and supportive environment that enables residents to strive to reach their potential and goals.

- Boost confidence, acknowledge genuine efforts, and praise achievements.

- Encourage involvement in future projects.

Empathy and generosity.

- Treat residents with respect and care, while recognizing their strengths and weaknesses.

- Understand them at both a professional and personal level.

- Support meaningful and suitable projects that residents are passionate about and at which they excel.

- Influence residents by helping them understand the impact they have on patients and the program.

- Demonstrate sensitivity to the individual needs of each resident and provide constructive feedback.

Easy accessibility.

- Build good rapport with residents.

- Listen carefully to the residents’ ideas and feedback.

- Reassure residents that they can ask any questions or raise any issues they want to address.

Leadership.

- Color/BlackUndertake a leadership role within multidisciplinary teams, and collaborate effectively with other medical specialties for continuity of care, mutual support, Color/Blackand interdisciplinary education and communication.

- Assert authority when needed, and make important decisions for the program.

- Manage conflicts effectively and timely.

- Strictly monitor duty hours.3

Education.

- Design an educational curriculum relevant to all clinical settings.

- Provide protected time for didactics and scholarlyColor/Black activities.

- Ensure that residents develop a comprehensive understanding of the field.

- Actively involve residents in teaching, and modify the curriculum based on residents’ input and feedback.

- Schedule classes for in-service exams (eg, Psychiatry Residency In-Service Training Exam) and for the board exam preparation.4

- Promote residents’ autonomy and sense of competence.

Promote residents well-being.

- Encourage a work–life balance.

- Focus on team building and communication, and organize process groups.

- Adopt innovative ways to enable residents in managing stress.

- Organize social events and group activities, and provide support groups.

- Ensure adequate sleep hours and time away from work to prevent burnout.

Career development.

- Provide career guidance, and connect residents to appropriate resources for further professional development.

- Recognize that mentoring is a lifelong activity that does not end with the completion of residency training.

The term psychiatry is derived from the Greek words “pskhe” and “iatreia” which mean “healing of the soul.”1 The desire to heal souls from different ethnicities, religions, and languages can be overwhelming for a trainee resident who is new to U.S. culture. The fear of having difficulty in building rapport with patients because of cultural bias and the dread of not understanding accents, slang, jokes, and nonverbal communication can be so frustrating that it overrides the intense desire of becoming an empathetic and successful physician.2 Du

I started my residency training in 2014 without any substantial scholarly work in my background or clinical experience in the United States. However, I had a great learning experience at my training program and would like to express my gratitude by recognizing my program director’s (Panagiota Korenis, MD) role in helping me accomplish my career goals. She believed in me when I was not able to believe in myself, and helped me overcome a helpless feeling of isolation and desperation during my intern year. Because of her mentorship and supervision, I presented 20 posters and oral presentations; published 5 works; drafted guidelines for training residents, including course material on the health care disparities faced by the Lesbian, Gay Bisexual, Transgender, Queer community; created a tool to predict readmissions in an inpatient psychiatric setting; received many prestigious awards, including Resident of the Year, a Certificate of Academic Excellence, a Young Scholar Award, and an American Psychiatric Association Diversity Leadership Fellowship for 2017-2019; and was accepted for a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship in one of my dream programs, Boston Children’s Hospital.

I strongly believe that the impact of an inspiring, motivating, and encouraging program director on a resident’s life is monumental. Here are some of the qualities I believe make a great program director who can significantly transform a trainee’s life:

A positive attitude.

- Encourage trainees to believe in their abilities, even if they stumble.

- Unleash and nurture their talents, and help them recognize their strengths and confidence.

- Foster a warm, welcoming, and supportive environment that enables residents to strive to reach their potential and goals.

- Boost confidence, acknowledge genuine efforts, and praise achievements.

- Encourage involvement in future projects.

Empathy and generosity.

- Treat residents with respect and care, while recognizing their strengths and weaknesses.

- Understand them at both a professional and personal level.

- Support meaningful and suitable projects that residents are passionate about and at which they excel.

- Influence residents by helping them understand the impact they have on patients and the program.

- Demonstrate sensitivity to the individual needs of each resident and provide constructive feedback.

Easy accessibility.

- Build good rapport with residents.

- Listen carefully to the residents’ ideas and feedback.

- Reassure residents that they can ask any questions or raise any issues they want to address.

Leadership.

- Color/BlackUndertake a leadership role within multidisciplinary teams, and collaborate effectively with other medical specialties for continuity of care, mutual support, Color/Blackand interdisciplinary education and communication.

- Assert authority when needed, and make important decisions for the program.

- Manage conflicts effectively and timely.

- Strictly monitor duty hours.3

Education.

- Design an educational curriculum relevant to all clinical settings.

- Provide protected time for didactics and scholarlyColor/Black activities.

- Ensure that residents develop a comprehensive understanding of the field.

- Actively involve residents in teaching, and modify the curriculum based on residents’ input and feedback.

- Schedule classes for in-service exams (eg, Psychiatry Residency In-Service Training Exam) and for the board exam preparation.4

- Promote residents’ autonomy and sense of competence.

Promote residents well-being.

- Encourage a work–life balance.

- Focus on team building and communication, and organize process groups.

- Adopt innovative ways to enable residents in managing stress.

- Organize social events and group activities, and provide support groups.

- Ensure adequate sleep hours and time away from work to prevent burnout.

Career development.

- Provide career guidance, and connect residents to appropriate resources for further professional development.

- Recognize that mentoring is a lifelong activity that does not end with the completion of residency training.

1. Gilman DC, Peck HT, Colby FM, eds. The new international encyclopedia. Vol 16. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead and Company; 2000:505.

2. Saeed F, Majeed MH, Kousar N. Easing international medical graduates’ entry into US training. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):269.

3. Johnson V. A resitern’s reflection on duty-hours reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):2278-2279.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Defining the key elements of an optimal residency program. https://www.aamc.org/download/84544/data/definekeyelements.pdf. Published May 2001. Accessed June 7, 2017.

1. Gilman DC, Peck HT, Colby FM, eds. The new international encyclopedia. Vol 16. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead and Company; 2000:505.

2. Saeed F, Majeed MH, Kousar N. Easing international medical graduates’ entry into US training. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):269.

3. Johnson V. A resitern’s reflection on duty-hours reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):2278-2279.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Defining the key elements of an optimal residency program. https://www.aamc.org/download/84544/data/definekeyelements.pdf. Published May 2001. Accessed June 7, 2017.

Managing patients who are somatizing

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Malingering in apparently psychotic patients: Detecting it and dealing with it

Imagine you’re on call in a busy emergency department (ED) overnight. Things are tough. The consults are piling up, no one is returning your calls for collateral information, and you’re dealing with a myriad of emergencies.

In walks Mr. D, age 45, complaining of hearing voices, feeling unsafe, and asking for admission. It’s now 2

Of course, like all qualified psychiatrists, you will dig a little deeper, and in doing so you learn that Mr. D has visited this hospital before and has been admitted to the psychiatry unit. Now you go from having a dearth of information to having more records than you can count.

You discover that Mr. D has a history of coming to the ED during precarious hours, with similar complaints, demanding admission.

Mr. D, you learn, is unemployed, single, and homeless. Your meticulous search through his hospital records and previous admission and discharge notes reveal that once he has slept for a night, eaten a hot meal, and received narcotics for his back pain and benzodiazepines for his “symptoms” he demands to leave the hospital. His psychotic symptoms disappear despite his consistent refusal to take antipsychotics throughout his stay.

Now, what would you do?

As earnest medical students and psychiatrists, we enjoy helping patients on their path toward recovery. We want to advocate for our patients and give them the benefit of the doubt. We’re taught in medical school to be non-judgmental and invite patients to share their narrative. But through experience, we start to become aware of malingering.

Suspecting malingering, diagnosed as a condition, often is avoided by psychiatrists.1 This makes sense—it goes against the essence of our training and imposes a pejorative label on someone who has reached out for help.

Often persons with mental illness will suffer for years until they to receive help.2 That’s exactly why, when patients like Mr. D come to the ED and report hearing voices, we’re not likely to shout, “Liar!” and invite them to leave.

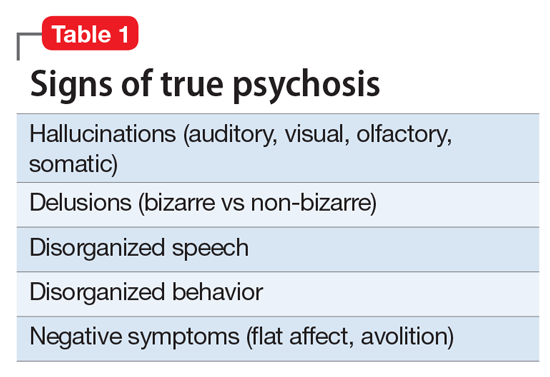

However, malingering is a real problem, especially because the number of psychiatric hospital beds have dwindled to record lows, thereby overcrowding EDs. Resources are skimpy, and clinicians want to help those who need it the most and not waste resources on someone who is “faking it” for secondary gain.

To navigate this diagnostic challenge, psychiatrists need the skills to detect malingering and the confidence to deal with it appropriately. This article aims to:

- define psychosis and malingering

- review the prevalence and historical considerations of malingering

- offer practical strategies to deal with malingering.

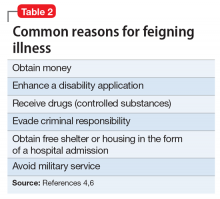

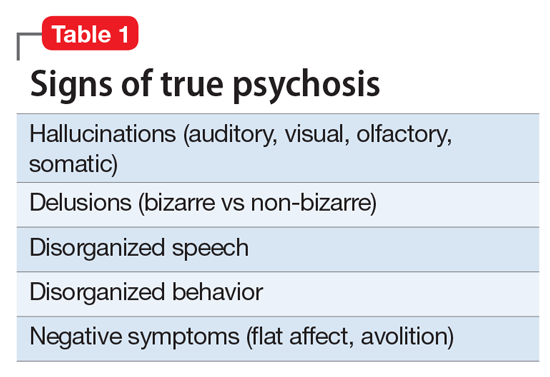

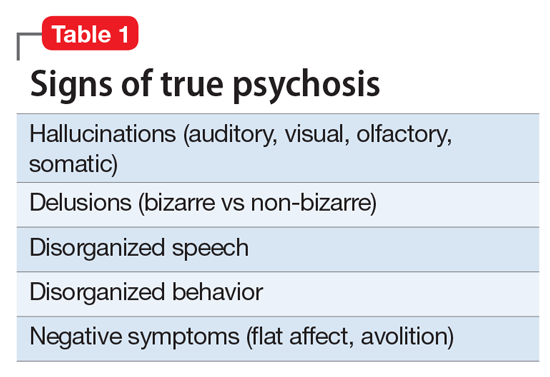

Know the real thing

Clinicians first must have the clinical acumen and expertise to identify a true mental illness such as psychosis2 (Table 1). The differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms is broad. The astute clinician might suspect that untreated bipolar disorder or depression led to the emergence of perceptual disturbances or disordered thinking. Transient psychotic symptoms can be associated with trauma disorders, borderline personality disorder, and acute intoxication. Psychotic spectrum disorders range from brief psychosis to schizophreniform to schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia.

Malingering—which is a condition, not a diagnosis—is characterized by the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms motivated by external incentives.3,4 The presence of external incentives differentiates malingering from true psychiatric disorders, including factitious disorder, somatoform disorder, and dissociative disorder, and specific medical conditions.1 In those disorders, there is no external incentive.

It is important to remember that malingering can coexist with a serious mental illness. For example, a truly psychotic person might malinger, feign, or exaggerate symptoms to try to receive much needed help. Individuals with true psychosis might have become disenchanted with the mental health system, and thereby have a tendency to over-report or exaggerate symptoms in an effort to obtain treatment. This also could explain why many clinicians intuitively are reluctant to make the determination that someone is malingering. Malingering also can be present in an individual who has antisocial personality disorder, factitious disorder, Ganser syndrome, and Munchausen syndrome.4 When symptoms or diseases that either are thought to be exaggerated or do not exist, consider a diagnosis of malingering.

A key challenge in any discussion of abnormal health care–seeking behavior is the extent to which a person’s reported symptoms are considered to be a product of choice, psychopathology beyond volitional control, or perhaps both. Clinical skills alone typically are not sufficient for diagnosing or detecting malingering. Medical education needs to provide doctors with the conceptual, developmental, and management frameworks to understand and manage patients whose symptoms appear to be simulated. Central to understanding factitious disorders and malingering are the explanatory models and beliefs used to provide meaning for both patients and doctors.7

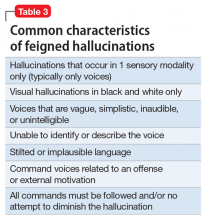

When considering malingered psychosis, the suspecting physician must stay alert to possible motives. Also, the patient’s presentation might provide some clues when there is marked variability, such as discrepancies in the history, gross inconsistencies, or blatant contradictions. Hallucinations are a heterogeneous experience, and discerning between true vs feigned symptoms can be challenging for even the seasoned clinician. It can be helpful to study the phenomenology of typical vs atypical hallucinatory symptoms.8 Examples of atypical symptoms include:

- vague hallucinations

- experiencing hallucinations of only 1 sensory modality (such as voices alone, visual images in black and white only)

- delusions that have an abrupt onset

- bizarre content without disordered thinking.2,6,9,10

The truth about an untruthful condition

Although the exact prevalence of malingering varies by circumstance, Rissmiller et al12,13 demonstrated—and later replicated—a prevalence of approximately 10% among patients hospitalized for suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Studies have demonstrated even higher prevalence within forensic populations, which seems reasonable because evading criminal responsibility is a large incentive to feign symptoms. Studies also have shown that 5% of military recruits will feign symptoms to avoid service. Moreover, 1% of psychiatric patients, such as Mr. D, feign symptoms for secondary gain.13

Although there are no psychometrically validated assessment tools to distinguish between real vs feigned hallucinations, several standardized tests can help tease out the truth.9 The preferred personality test used in forensic settings is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory,14 which consists of 567 items, with 10 clinical scales and several validity scales. The F scale, “faking good” or “faking bad,” detects people who are answering questions with the goal of appearing better or worse than they actually are. In studies of patients hospitalized for being at risk for suicide who were administered tests of self-reported malingering, approximately 10% of people admitted to psychiatric units were “faking” their symptoms.14

It is important to identify malingering from a professional and public health standpoint. Society incurs incremental costs when a person uses dwindling mental health resources for their own reward, leaving others to suffer without treatment. The number of psychiatric hospital beds has fallen from half a million in the 1950s to approximately 100,000 today.15

Practical guidelines

Malingering presents specific challenges to clinicians, such as:

- diagnostic uncertainty

- inaccurately branding one a liar

- countertransference

- personal reactions.

Our ethical and fiduciary responsibility is to our patient. In examining the art in medicine, it has been suggested that malingering could be viewed as an immature or primitive defense.16

Although there often is suspicion that a person is malingering, a definitive statement of such must be confirmed. Without clarity, labeling an individual as a malingerer could have detrimental effects to his (her) future care, defames his character, and places a thoughtless examiner at risk of a lawsuit. Confirmation can be achieved by observation or psychological testing methods.

Observation. When in doubt of what to do with someone such as Mr. D, there is little harm in acting prudently by holding him in a controlled setting—whether keeping him overnight in an ED or admitting him for a brief psychiatric stay. By observing someone in a controlled environment, where there are multiple professional watchful eyes, inferences will be more accurate.1

Structured assessments have been developed to help detect malingering—one example is the Test of Memory Malingering—however, in daily practice, the physician generally should suspect malingering when there are tangible incentives and when reported symptoms do not match the physical examination or there is no organic basis for the physical complaints.17 Detecting illness deception relies on converging evidence sources, including detailed interview assessments, clinical notes, and consultations.7

When you feel certain that you are encountering someone who is malingering, the final step is to get a consult. Malingering is a serious label and warrants due diligence by the provider, rather than a haphazard guess that a patient is lying. Once you receive confirmatory opinions, great care should be taken in documenting a clear and accurate note that will benefit your clinical counterpart who might encounter a patient such as Mr. D when he (she) shows up again, and will go a long way toward appropriately directing his care.

1. LoPiccolo CJ, Goodkin K, Baldewicz TT. Current issues in the diagnosis and management of malingering. Ann Med. 1999;31(3):166-174.

2. Resnick PJ, Knoll J. Faking it: how to detect malingered psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(11):12-25.

3. Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2007:887.

4. Gorman WF. Defining malingering. J Forensic Sci. 1982;27(2):401-407.

5. Mendelson G, Mendelson D. Malingering pain in the medicolegal context. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(6):423-432.

6. Resnick PJ. Malingered psychosis. In: Rogers R, ed. Clinical assessment of malingering and deception. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1997:47-67.

7. Bass C, Halligan P. Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422-1432.

8. McCarthy-Jones S, Resnick PJ. Listening to the voices: the use of phenomenology to differentiate malingered from genuine auditory verbal hallucinations. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2014;37(2):183-189.

9. Resnick PJ. Defrocking the fraud: the detection of malingering. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1993;30(2):93-101.

10. Nayani TH, David AS. The auditory hallucination: a phenomenological survey. Psychol Med. 1996;26(1):177-189.

11. Pollock P. Feigning auditory hallucinations by offenders. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 1998;9(2)305-327.

12. Rissmiller DJ, Wayslow A, Madison H, et al. Prevalence of malingering in inpatient suicide ideators and attempters. Crisis. 1998;19(2):62-66.

13. Rissmiller DA, Steer RA, Friedman M, et al. Prevalence of malingering in suicidal psychiatric patients: a replication. Psychol Rep. 1999;84(3 pt 1):726-730.

14. Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1989.

15. Szabo L. Cost of not caring: Stigma set in stone. USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/06/25/stigma-of-mental-illness/9875351. Published June 25, 2014. Accessed May 5, 2017.

16. Malone RD, Lange CL. A clinical approach to the malingering patient. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2007;35(1):13-21.

17. McDermott BE, Feldman MD. Malingering in the medical setting. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(4):645-662.

Imagine you’re on call in a busy emergency department (ED) overnight. Things are tough. The consults are piling up, no one is returning your calls for collateral information, and you’re dealing with a myriad of emergencies.

In walks Mr. D, age 45, complaining of hearing voices, feeling unsafe, and asking for admission. It’s now 2

Of course, like all qualified psychiatrists, you will dig a little deeper, and in doing so you learn that Mr. D has visited this hospital before and has been admitted to the psychiatry unit. Now you go from having a dearth of information to having more records than you can count.

You discover that Mr. D has a history of coming to the ED during precarious hours, with similar complaints, demanding admission.

Mr. D, you learn, is unemployed, single, and homeless. Your meticulous search through his hospital records and previous admission and discharge notes reveal that once he has slept for a night, eaten a hot meal, and received narcotics for his back pain and benzodiazepines for his “symptoms” he demands to leave the hospital. His psychotic symptoms disappear despite his consistent refusal to take antipsychotics throughout his stay.

Now, what would you do?

As earnest medical students and psychiatrists, we enjoy helping patients on their path toward recovery. We want to advocate for our patients and give them the benefit of the doubt. We’re taught in medical school to be non-judgmental and invite patients to share their narrative. But through experience, we start to become aware of malingering.

Suspecting malingering, diagnosed as a condition, often is avoided by psychiatrists.1 This makes sense—it goes against the essence of our training and imposes a pejorative label on someone who has reached out for help.

Often persons with mental illness will suffer for years until they to receive help.2 That’s exactly why, when patients like Mr. D come to the ED and report hearing voices, we’re not likely to shout, “Liar!” and invite them to leave.

However, malingering is a real problem, especially because the number of psychiatric hospital beds have dwindled to record lows, thereby overcrowding EDs. Resources are skimpy, and clinicians want to help those who need it the most and not waste resources on someone who is “faking it” for secondary gain.

To navigate this diagnostic challenge, psychiatrists need the skills to detect malingering and the confidence to deal with it appropriately. This article aims to:

- define psychosis and malingering

- review the prevalence and historical considerations of malingering

- offer practical strategies to deal with malingering.

Know the real thing

Clinicians first must have the clinical acumen and expertise to identify a true mental illness such as psychosis2 (Table 1). The differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms is broad. The astute clinician might suspect that untreated bipolar disorder or depression led to the emergence of perceptual disturbances or disordered thinking. Transient psychotic symptoms can be associated with trauma disorders, borderline personality disorder, and acute intoxication. Psychotic spectrum disorders range from brief psychosis to schizophreniform to schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia.

Malingering—which is a condition, not a diagnosis—is characterized by the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms motivated by external incentives.3,4 The presence of external incentives differentiates malingering from true psychiatric disorders, including factitious disorder, somatoform disorder, and dissociative disorder, and specific medical conditions.1 In those disorders, there is no external incentive.

It is important to remember that malingering can coexist with a serious mental illness. For example, a truly psychotic person might malinger, feign, or exaggerate symptoms to try to receive much needed help. Individuals with true psychosis might have become disenchanted with the mental health system, and thereby have a tendency to over-report or exaggerate symptoms in an effort to obtain treatment. This also could explain why many clinicians intuitively are reluctant to make the determination that someone is malingering. Malingering also can be present in an individual who has antisocial personality disorder, factitious disorder, Ganser syndrome, and Munchausen syndrome.4 When symptoms or diseases that either are thought to be exaggerated or do not exist, consider a diagnosis of malingering.

A key challenge in any discussion of abnormal health care–seeking behavior is the extent to which a person’s reported symptoms are considered to be a product of choice, psychopathology beyond volitional control, or perhaps both. Clinical skills alone typically are not sufficient for diagnosing or detecting malingering. Medical education needs to provide doctors with the conceptual, developmental, and management frameworks to understand and manage patients whose symptoms appear to be simulated. Central to understanding factitious disorders and malingering are the explanatory models and beliefs used to provide meaning for both patients and doctors.7

When considering malingered psychosis, the suspecting physician must stay alert to possible motives. Also, the patient’s presentation might provide some clues when there is marked variability, such as discrepancies in the history, gross inconsistencies, or blatant contradictions. Hallucinations are a heterogeneous experience, and discerning between true vs feigned symptoms can be challenging for even the seasoned clinician. It can be helpful to study the phenomenology of typical vs atypical hallucinatory symptoms.8 Examples of atypical symptoms include:

- vague hallucinations

- experiencing hallucinations of only 1 sensory modality (such as voices alone, visual images in black and white only)

- delusions that have an abrupt onset

- bizarre content without disordered thinking.2,6,9,10

The truth about an untruthful condition

Although the exact prevalence of malingering varies by circumstance, Rissmiller et al12,13 demonstrated—and later replicated—a prevalence of approximately 10% among patients hospitalized for suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Studies have demonstrated even higher prevalence within forensic populations, which seems reasonable because evading criminal responsibility is a large incentive to feign symptoms. Studies also have shown that 5% of military recruits will feign symptoms to avoid service. Moreover, 1% of psychiatric patients, such as Mr. D, feign symptoms for secondary gain.13

Although there are no psychometrically validated assessment tools to distinguish between real vs feigned hallucinations, several standardized tests can help tease out the truth.9 The preferred personality test used in forensic settings is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory,14 which consists of 567 items, with 10 clinical scales and several validity scales. The F scale, “faking good” or “faking bad,” detects people who are answering questions with the goal of appearing better or worse than they actually are. In studies of patients hospitalized for being at risk for suicide who were administered tests of self-reported malingering, approximately 10% of people admitted to psychiatric units were “faking” their symptoms.14

It is important to identify malingering from a professional and public health standpoint. Society incurs incremental costs when a person uses dwindling mental health resources for their own reward, leaving others to suffer without treatment. The number of psychiatric hospital beds has fallen from half a million in the 1950s to approximately 100,000 today.15

Practical guidelines

Malingering presents specific challenges to clinicians, such as:

- diagnostic uncertainty

- inaccurately branding one a liar

- countertransference

- personal reactions.

Our ethical and fiduciary responsibility is to our patient. In examining the art in medicine, it has been suggested that malingering could be viewed as an immature or primitive defense.16

Although there often is suspicion that a person is malingering, a definitive statement of such must be confirmed. Without clarity, labeling an individual as a malingerer could have detrimental effects to his (her) future care, defames his character, and places a thoughtless examiner at risk of a lawsuit. Confirmation can be achieved by observation or psychological testing methods.

Observation. When in doubt of what to do with someone such as Mr. D, there is little harm in acting prudently by holding him in a controlled setting—whether keeping him overnight in an ED or admitting him for a brief psychiatric stay. By observing someone in a controlled environment, where there are multiple professional watchful eyes, inferences will be more accurate.1

Structured assessments have been developed to help detect malingering—one example is the Test of Memory Malingering—however, in daily practice, the physician generally should suspect malingering when there are tangible incentives and when reported symptoms do not match the physical examination or there is no organic basis for the physical complaints.17 Detecting illness deception relies on converging evidence sources, including detailed interview assessments, clinical notes, and consultations.7

When you feel certain that you are encountering someone who is malingering, the final step is to get a consult. Malingering is a serious label and warrants due diligence by the provider, rather than a haphazard guess that a patient is lying. Once you receive confirmatory opinions, great care should be taken in documenting a clear and accurate note that will benefit your clinical counterpart who might encounter a patient such as Mr. D when he (she) shows up again, and will go a long way toward appropriately directing his care.

Imagine you’re on call in a busy emergency department (ED) overnight. Things are tough. The consults are piling up, no one is returning your calls for collateral information, and you’re dealing with a myriad of emergencies.

In walks Mr. D, age 45, complaining of hearing voices, feeling unsafe, and asking for admission. It’s now 2

Of course, like all qualified psychiatrists, you will dig a little deeper, and in doing so you learn that Mr. D has visited this hospital before and has been admitted to the psychiatry unit. Now you go from having a dearth of information to having more records than you can count.

You discover that Mr. D has a history of coming to the ED during precarious hours, with similar complaints, demanding admission.

Mr. D, you learn, is unemployed, single, and homeless. Your meticulous search through his hospital records and previous admission and discharge notes reveal that once he has slept for a night, eaten a hot meal, and received narcotics for his back pain and benzodiazepines for his “symptoms” he demands to leave the hospital. His psychotic symptoms disappear despite his consistent refusal to take antipsychotics throughout his stay.

Now, what would you do?

As earnest medical students and psychiatrists, we enjoy helping patients on their path toward recovery. We want to advocate for our patients and give them the benefit of the doubt. We’re taught in medical school to be non-judgmental and invite patients to share their narrative. But through experience, we start to become aware of malingering.

Suspecting malingering, diagnosed as a condition, often is avoided by psychiatrists.1 This makes sense—it goes against the essence of our training and imposes a pejorative label on someone who has reached out for help.

Often persons with mental illness will suffer for years until they to receive help.2 That’s exactly why, when patients like Mr. D come to the ED and report hearing voices, we’re not likely to shout, “Liar!” and invite them to leave.

However, malingering is a real problem, especially because the number of psychiatric hospital beds have dwindled to record lows, thereby overcrowding EDs. Resources are skimpy, and clinicians want to help those who need it the most and not waste resources on someone who is “faking it” for secondary gain.

To navigate this diagnostic challenge, psychiatrists need the skills to detect malingering and the confidence to deal with it appropriately. This article aims to:

- define psychosis and malingering

- review the prevalence and historical considerations of malingering

- offer practical strategies to deal with malingering.

Know the real thing

Clinicians first must have the clinical acumen and expertise to identify a true mental illness such as psychosis2 (Table 1). The differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms is broad. The astute clinician might suspect that untreated bipolar disorder or depression led to the emergence of perceptual disturbances or disordered thinking. Transient psychotic symptoms can be associated with trauma disorders, borderline personality disorder, and acute intoxication. Psychotic spectrum disorders range from brief psychosis to schizophreniform to schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia.

Malingering—which is a condition, not a diagnosis—is characterized by the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms motivated by external incentives.3,4 The presence of external incentives differentiates malingering from true psychiatric disorders, including factitious disorder, somatoform disorder, and dissociative disorder, and specific medical conditions.1 In those disorders, there is no external incentive.

It is important to remember that malingering can coexist with a serious mental illness. For example, a truly psychotic person might malinger, feign, or exaggerate symptoms to try to receive much needed help. Individuals with true psychosis might have become disenchanted with the mental health system, and thereby have a tendency to over-report or exaggerate symptoms in an effort to obtain treatment. This also could explain why many clinicians intuitively are reluctant to make the determination that someone is malingering. Malingering also can be present in an individual who has antisocial personality disorder, factitious disorder, Ganser syndrome, and Munchausen syndrome.4 When symptoms or diseases that either are thought to be exaggerated or do not exist, consider a diagnosis of malingering.

A key challenge in any discussion of abnormal health care–seeking behavior is the extent to which a person’s reported symptoms are considered to be a product of choice, psychopathology beyond volitional control, or perhaps both. Clinical skills alone typically are not sufficient for diagnosing or detecting malingering. Medical education needs to provide doctors with the conceptual, developmental, and management frameworks to understand and manage patients whose symptoms appear to be simulated. Central to understanding factitious disorders and malingering are the explanatory models and beliefs used to provide meaning for both patients and doctors.7

When considering malingered psychosis, the suspecting physician must stay alert to possible motives. Also, the patient’s presentation might provide some clues when there is marked variability, such as discrepancies in the history, gross inconsistencies, or blatant contradictions. Hallucinations are a heterogeneous experience, and discerning between true vs feigned symptoms can be challenging for even the seasoned clinician. It can be helpful to study the phenomenology of typical vs atypical hallucinatory symptoms.8 Examples of atypical symptoms include:

- vague hallucinations

- experiencing hallucinations of only 1 sensory modality (such as voices alone, visual images in black and white only)

- delusions that have an abrupt onset

- bizarre content without disordered thinking.2,6,9,10

The truth about an untruthful condition

Although the exact prevalence of malingering varies by circumstance, Rissmiller et al12,13 demonstrated—and later replicated—a prevalence of approximately 10% among patients hospitalized for suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Studies have demonstrated even higher prevalence within forensic populations, which seems reasonable because evading criminal responsibility is a large incentive to feign symptoms. Studies also have shown that 5% of military recruits will feign symptoms to avoid service. Moreover, 1% of psychiatric patients, such as Mr. D, feign symptoms for secondary gain.13

Although there are no psychometrically validated assessment tools to distinguish between real vs feigned hallucinations, several standardized tests can help tease out the truth.9 The preferred personality test used in forensic settings is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory,14 which consists of 567 items, with 10 clinical scales and several validity scales. The F scale, “faking good” or “faking bad,” detects people who are answering questions with the goal of appearing better or worse than they actually are. In studies of patients hospitalized for being at risk for suicide who were administered tests of self-reported malingering, approximately 10% of people admitted to psychiatric units were “faking” their symptoms.14

It is important to identify malingering from a professional and public health standpoint. Society incurs incremental costs when a person uses dwindling mental health resources for their own reward, leaving others to suffer without treatment. The number of psychiatric hospital beds has fallen from half a million in the 1950s to approximately 100,000 today.15

Practical guidelines

Malingering presents specific challenges to clinicians, such as:

- diagnostic uncertainty

- inaccurately branding one a liar

- countertransference

- personal reactions.

Our ethical and fiduciary responsibility is to our patient. In examining the art in medicine, it has been suggested that malingering could be viewed as an immature or primitive defense.16

Although there often is suspicion that a person is malingering, a definitive statement of such must be confirmed. Without clarity, labeling an individual as a malingerer could have detrimental effects to his (her) future care, defames his character, and places a thoughtless examiner at risk of a lawsuit. Confirmation can be achieved by observation or psychological testing methods.

Observation. When in doubt of what to do with someone such as Mr. D, there is little harm in acting prudently by holding him in a controlled setting—whether keeping him overnight in an ED or admitting him for a brief psychiatric stay. By observing someone in a controlled environment, where there are multiple professional watchful eyes, inferences will be more accurate.1

Structured assessments have been developed to help detect malingering—one example is the Test of Memory Malingering—however, in daily practice, the physician generally should suspect malingering when there are tangible incentives and when reported symptoms do not match the physical examination or there is no organic basis for the physical complaints.17 Detecting illness deception relies on converging evidence sources, including detailed interview assessments, clinical notes, and consultations.7

When you feel certain that you are encountering someone who is malingering, the final step is to get a consult. Malingering is a serious label and warrants due diligence by the provider, rather than a haphazard guess that a patient is lying. Once you receive confirmatory opinions, great care should be taken in documenting a clear and accurate note that will benefit your clinical counterpart who might encounter a patient such as Mr. D when he (she) shows up again, and will go a long way toward appropriately directing his care.

1. LoPiccolo CJ, Goodkin K, Baldewicz TT. Current issues in the diagnosis and management of malingering. Ann Med. 1999;31(3):166-174.

2. Resnick PJ, Knoll J. Faking it: how to detect malingered psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(11):12-25.

3. Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2007:887.

4. Gorman WF. Defining malingering. J Forensic Sci. 1982;27(2):401-407.

5. Mendelson G, Mendelson D. Malingering pain in the medicolegal context. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(6):423-432.

6. Resnick PJ. Malingered psychosis. In: Rogers R, ed. Clinical assessment of malingering and deception. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1997:47-67.

7. Bass C, Halligan P. Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422-1432.

8. McCarthy-Jones S, Resnick PJ. Listening to the voices: the use of phenomenology to differentiate malingered from genuine auditory verbal hallucinations. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2014;37(2):183-189.

9. Resnick PJ. Defrocking the fraud: the detection of malingering. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1993;30(2):93-101.

10. Nayani TH, David AS. The auditory hallucination: a phenomenological survey. Psychol Med. 1996;26(1):177-189.

11. Pollock P. Feigning auditory hallucinations by offenders. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 1998;9(2)305-327.

12. Rissmiller DJ, Wayslow A, Madison H, et al. Prevalence of malingering in inpatient suicide ideators and attempters. Crisis. 1998;19(2):62-66.

13. Rissmiller DA, Steer RA, Friedman M, et al. Prevalence of malingering in suicidal psychiatric patients: a replication. Psychol Rep. 1999;84(3 pt 1):726-730.

14. Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1989.

15. Szabo L. Cost of not caring: Stigma set in stone. USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/06/25/stigma-of-mental-illness/9875351. Published June 25, 2014. Accessed May 5, 2017.

16. Malone RD, Lange CL. A clinical approach to the malingering patient. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2007;35(1):13-21.

17. McDermott BE, Feldman MD. Malingering in the medical setting. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(4):645-662.

1. LoPiccolo CJ, Goodkin K, Baldewicz TT. Current issues in the diagnosis and management of malingering. Ann Med. 1999;31(3):166-174.

2. Resnick PJ, Knoll J. Faking it: how to detect malingered psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(11):12-25.

3. Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2007:887.

4. Gorman WF. Defining malingering. J Forensic Sci. 1982;27(2):401-407.

5. Mendelson G, Mendelson D. Malingering pain in the medicolegal context. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(6):423-432.

6. Resnick PJ. Malingered psychosis. In: Rogers R, ed. Clinical assessment of malingering and deception. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1997:47-67.

7. Bass C, Halligan P. Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422-1432.

8. McCarthy-Jones S, Resnick PJ. Listening to the voices: the use of phenomenology to differentiate malingered from genuine auditory verbal hallucinations. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2014;37(2):183-189.

9. Resnick PJ. Defrocking the fraud: the detection of malingering. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1993;30(2):93-101.

10. Nayani TH, David AS. The auditory hallucination: a phenomenological survey. Psychol Med. 1996;26(1):177-189.

11. Pollock P. Feigning auditory hallucinations by offenders. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 1998;9(2)305-327.

12. Rissmiller DJ, Wayslow A, Madison H, et al. Prevalence of malingering in inpatient suicide ideators and attempters. Crisis. 1998;19(2):62-66.

13. Rissmiller DA, Steer RA, Friedman M, et al. Prevalence of malingering in suicidal psychiatric patients: a replication. Psychol Rep. 1999;84(3 pt 1):726-730.

14. Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1989.

15. Szabo L. Cost of not caring: Stigma set in stone. USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/06/25/stigma-of-mental-illness/9875351. Published June 25, 2014. Accessed May 5, 2017.

16. Malone RD, Lange CL. A clinical approach to the malingering patient. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2007;35(1):13-21.

17. McDermott BE, Feldman MD. Malingering in the medical setting. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(4):645-662.

Malingering

What role does asthma medication have in ADHD or depression?

Asthma medications comprise several drug classes, including leukotriene antagonists and steroid-based inhalers. These drugs have been implicated in behavioral changes, such as increased hyperactivity, similar to symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)1; this scenario is more of a concern in children than adults. This raises the question of whether these medications are physiologically linked to behavioral symptoms because of a suggested association with serotonin.2,3 If this is the case, it is necessary to identify and evaluate possible psychiatric effects of these asthma agents.

How asthma medications work

Some asthma agents, such as montelukast, act as either leukotriene-related enzyme inhibitors (arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase) or leukotriene receptor antagonists. These drugs block production of inflammatory leukotrienes, which cause bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also can trigger cytokine synthesis, which can modulate leukotriene receptor function. Therefore, leukotriene antagonists could interfere with cytokine function.3,4

Corticosteroid inhalers suppress inflammatory genes by reversing histone acetylation of inflammatory genes involved in asthma. These inhalers have been shown to reduce cytokine levels in patients with chronic lung disease and those with moderate to

Possible link between asthma and serotonin

Serotonin plays an integral role in observable, dysfunctional behaviors seen in disorders such as ADHD and ODD. In previous studies, serotonin modulated the cytokine network, and patients with asthma had elevated levels of plasma serotonin.2,3 These findings imply that asthma medications could be involved in altering levels of both cytokines and serotonin. Pretorius2 emphasized the importance of monitoring serotonin levels in children who exhibit behavioral dysfunction based on these observations:

- Persons with asthma presenting with medical symptoms have elevated serotonin levels.

- Decreased serotonin levels have been associated with ADHD and ODD; medications for ADHD have been shown to increase serotonin levels.

- Asthma medications have been shown to decrease serotonin levels.2,3

Asthma medications might be partially responsible for behavioral disturbances, and therapeutic management should integrate the role of serotonin with asthma therapy.2,3

Clinical considerations