User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

The art of psychopharmacology: Avoiding medication changes and slowing down

As physicians, we are cognizant of the importance of patient-centered care, active listening, empathy, and patience—the so-called “hidden curriculum of medicine.”1 However, our attempts to centralize these concepts may be overshadowed by the deeply rooted drive to treat and fix. At times, we are simply treating uncertainty, whether it be diagnostic uncertainty or the uncertainty arising from clinical responses and outcomes that are far from binary. Definitive actions, such as adding medications or altering dosages, may appear to both patients and physicians to be a step closer to a “cure.” However, watchful waiting, re-evaluation, and accepting uncertainty are the true skills of effective care.

Be savvy about psychopharmacology

Psychotropics can take weeks to months to reach their full potential, and have varying responses and adverse effects. Beware of changing regimens prematurely, and keep in mind basic, yet crucial, pharmacokinetic concepts (eg, 4 to 5 half-lives to reach steady state, variations in metabolism). Receptor binding and dosing heuristics are notably common in psychiatry. Although such concepts are important to grasp, there is no one-size-fits-all rule. The brain simply does not possess the heart’s machine-like, linear functioning. Therefore, targeting individual parts (ie, receptors) will not equate to fixing the whole organ systematically or predictably.

Is the patient truly treatment-resistant?

Even the best treatment regimen has no clinical benefit if the patient cannot afford the prescription or does not take the medication. If cost is an impediment, switch from brand name drugs to generic formulations or to older medications in the same class. Before declaring the patient “treatment-resistant” and making medication changes, assess for compliance. This may require assistance from collateral informants. Ask family members to count the number of pills remaining in the bottle, and call the pharmacy to find out the last refill dates. If the patient exhibits a partial response to what should be a therapeutic dose, consider obtaining drug plasma levels to rule out rapid metabolism before deeming the medication trial a failure.2

Medications as liabilities

Overreliance on medications can result in the medications becoming liabilities. The polypharmacy problem is not unique to psychiatry.3 However, psychiatric patients may be more likely to inadvertently use medications in a maladaptive manner and disrupt the fundamental goals of long-term care. Avoid making medication adjustments in response to a patient’s life stressors and normative situational reactions. Doing so is a disservice to patients, because we are robbing them of chances to develop necessary coping skills and defenses. This can be overtly damaging in certain patient populations, such as those with borderline personality disorder, who may use medication adjustments as a crutch during crises.4

Treat the patient, not yourself

We physicians mean well in prescribing evidence-based treatments; however, if the symptoms or adverse effects are not bothersome or cause functional impairment, we risk losing sight of the patient’s goals in treatment and imposing our own instead. Displacing the treatment focus can alienate the patient, harm the therapeutic alliance, and result in “pill fatigue.” For example, we may be tempted to treat antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia, even if the patient is not concerned about abnormal movements. Although we see this adverse effect

Change does not happen overnight

Picking a treatment option out of a lineup of choices, à la UWorld questions, does not always translate into patients agreeing with the suggested treatment, let alone the idea of receiving treatment at all. Motivational interviewing is our chance to shine in such situations and the reason why we are physicians, rather than answer-picking bots. Patients cannot change if they are not ready. However, we should be ready to roll with resistance while looking for signs of readiness to change. We must accept that it may take a week, a month, a year, or even longer for patients to align with our plan of action. The only futile decision is deeming our efforts as futile while discounting the benefits of incremental care.

1. Hafferty FW, Gaufberg EH, O’Donnell JF. The role of the hidden curriculum in “on doctoring” courses. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(2):130-139.

2. Horvitz-Lennon M, Mattke S, Predmore Z, et al. The role of antipsychotic plasma levels in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):421-426.

3. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818-1831.

4. Gunderson JG. The emergence of a generalist model to meet public health needs for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):452-458.

5. Kikkert MJ, Schene AH, Koeter MW, et al. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: exploring patients’, carers’ and professionals’ views. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(4):786-794.

As physicians, we are cognizant of the importance of patient-centered care, active listening, empathy, and patience—the so-called “hidden curriculum of medicine.”1 However, our attempts to centralize these concepts may be overshadowed by the deeply rooted drive to treat and fix. At times, we are simply treating uncertainty, whether it be diagnostic uncertainty or the uncertainty arising from clinical responses and outcomes that are far from binary. Definitive actions, such as adding medications or altering dosages, may appear to both patients and physicians to be a step closer to a “cure.” However, watchful waiting, re-evaluation, and accepting uncertainty are the true skills of effective care.

Be savvy about psychopharmacology

Psychotropics can take weeks to months to reach their full potential, and have varying responses and adverse effects. Beware of changing regimens prematurely, and keep in mind basic, yet crucial, pharmacokinetic concepts (eg, 4 to 5 half-lives to reach steady state, variations in metabolism). Receptor binding and dosing heuristics are notably common in psychiatry. Although such concepts are important to grasp, there is no one-size-fits-all rule. The brain simply does not possess the heart’s machine-like, linear functioning. Therefore, targeting individual parts (ie, receptors) will not equate to fixing the whole organ systematically or predictably.

Is the patient truly treatment-resistant?

Even the best treatment regimen has no clinical benefit if the patient cannot afford the prescription or does not take the medication. If cost is an impediment, switch from brand name drugs to generic formulations or to older medications in the same class. Before declaring the patient “treatment-resistant” and making medication changes, assess for compliance. This may require assistance from collateral informants. Ask family members to count the number of pills remaining in the bottle, and call the pharmacy to find out the last refill dates. If the patient exhibits a partial response to what should be a therapeutic dose, consider obtaining drug plasma levels to rule out rapid metabolism before deeming the medication trial a failure.2

Medications as liabilities

Overreliance on medications can result in the medications becoming liabilities. The polypharmacy problem is not unique to psychiatry.3 However, psychiatric patients may be more likely to inadvertently use medications in a maladaptive manner and disrupt the fundamental goals of long-term care. Avoid making medication adjustments in response to a patient’s life stressors and normative situational reactions. Doing so is a disservice to patients, because we are robbing them of chances to develop necessary coping skills and defenses. This can be overtly damaging in certain patient populations, such as those with borderline personality disorder, who may use medication adjustments as a crutch during crises.4

Treat the patient, not yourself

We physicians mean well in prescribing evidence-based treatments; however, if the symptoms or adverse effects are not bothersome or cause functional impairment, we risk losing sight of the patient’s goals in treatment and imposing our own instead. Displacing the treatment focus can alienate the patient, harm the therapeutic alliance, and result in “pill fatigue.” For example, we may be tempted to treat antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia, even if the patient is not concerned about abnormal movements. Although we see this adverse effect

Change does not happen overnight

Picking a treatment option out of a lineup of choices, à la UWorld questions, does not always translate into patients agreeing with the suggested treatment, let alone the idea of receiving treatment at all. Motivational interviewing is our chance to shine in such situations and the reason why we are physicians, rather than answer-picking bots. Patients cannot change if they are not ready. However, we should be ready to roll with resistance while looking for signs of readiness to change. We must accept that it may take a week, a month, a year, or even longer for patients to align with our plan of action. The only futile decision is deeming our efforts as futile while discounting the benefits of incremental care.

As physicians, we are cognizant of the importance of patient-centered care, active listening, empathy, and patience—the so-called “hidden curriculum of medicine.”1 However, our attempts to centralize these concepts may be overshadowed by the deeply rooted drive to treat and fix. At times, we are simply treating uncertainty, whether it be diagnostic uncertainty or the uncertainty arising from clinical responses and outcomes that are far from binary. Definitive actions, such as adding medications or altering dosages, may appear to both patients and physicians to be a step closer to a “cure.” However, watchful waiting, re-evaluation, and accepting uncertainty are the true skills of effective care.

Be savvy about psychopharmacology

Psychotropics can take weeks to months to reach their full potential, and have varying responses and adverse effects. Beware of changing regimens prematurely, and keep in mind basic, yet crucial, pharmacokinetic concepts (eg, 4 to 5 half-lives to reach steady state, variations in metabolism). Receptor binding and dosing heuristics are notably common in psychiatry. Although such concepts are important to grasp, there is no one-size-fits-all rule. The brain simply does not possess the heart’s machine-like, linear functioning. Therefore, targeting individual parts (ie, receptors) will not equate to fixing the whole organ systematically or predictably.

Is the patient truly treatment-resistant?

Even the best treatment regimen has no clinical benefit if the patient cannot afford the prescription or does not take the medication. If cost is an impediment, switch from brand name drugs to generic formulations or to older medications in the same class. Before declaring the patient “treatment-resistant” and making medication changes, assess for compliance. This may require assistance from collateral informants. Ask family members to count the number of pills remaining in the bottle, and call the pharmacy to find out the last refill dates. If the patient exhibits a partial response to what should be a therapeutic dose, consider obtaining drug plasma levels to rule out rapid metabolism before deeming the medication trial a failure.2

Medications as liabilities

Overreliance on medications can result in the medications becoming liabilities. The polypharmacy problem is not unique to psychiatry.3 However, psychiatric patients may be more likely to inadvertently use medications in a maladaptive manner and disrupt the fundamental goals of long-term care. Avoid making medication adjustments in response to a patient’s life stressors and normative situational reactions. Doing so is a disservice to patients, because we are robbing them of chances to develop necessary coping skills and defenses. This can be overtly damaging in certain patient populations, such as those with borderline personality disorder, who may use medication adjustments as a crutch during crises.4

Treat the patient, not yourself

We physicians mean well in prescribing evidence-based treatments; however, if the symptoms or adverse effects are not bothersome or cause functional impairment, we risk losing sight of the patient’s goals in treatment and imposing our own instead. Displacing the treatment focus can alienate the patient, harm the therapeutic alliance, and result in “pill fatigue.” For example, we may be tempted to treat antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia, even if the patient is not concerned about abnormal movements. Although we see this adverse effect

Change does not happen overnight

Picking a treatment option out of a lineup of choices, à la UWorld questions, does not always translate into patients agreeing with the suggested treatment, let alone the idea of receiving treatment at all. Motivational interviewing is our chance to shine in such situations and the reason why we are physicians, rather than answer-picking bots. Patients cannot change if they are not ready. However, we should be ready to roll with resistance while looking for signs of readiness to change. We must accept that it may take a week, a month, a year, or even longer for patients to align with our plan of action. The only futile decision is deeming our efforts as futile while discounting the benefits of incremental care.

1. Hafferty FW, Gaufberg EH, O’Donnell JF. The role of the hidden curriculum in “on doctoring” courses. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(2):130-139.

2. Horvitz-Lennon M, Mattke S, Predmore Z, et al. The role of antipsychotic plasma levels in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):421-426.

3. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818-1831.

4. Gunderson JG. The emergence of a generalist model to meet public health needs for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):452-458.

5. Kikkert MJ, Schene AH, Koeter MW, et al. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: exploring patients’, carers’ and professionals’ views. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(4):786-794.

1. Hafferty FW, Gaufberg EH, O’Donnell JF. The role of the hidden curriculum in “on doctoring” courses. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17(2):130-139.

2. Horvitz-Lennon M, Mattke S, Predmore Z, et al. The role of antipsychotic plasma levels in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):421-426.

3. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818-1831.

4. Gunderson JG. The emergence of a generalist model to meet public health needs for patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):452-458.

5. Kikkert MJ, Schene AH, Koeter MW, et al. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: exploring patients’, carers’ and professionals’ views. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(4):786-794.

Providing psychotherapy? Keep these principles in mind

Although the biological aspects of psychiatry are crucial, psychotherapy is an integral part of psychiatry. Unfortunately, the emphasis on psychotherapy training in psychiatry residency programs has declined compared with a decade or more ago. In an era of dwindling psychotherapy training and resources, the quality and type of psychotherapy training has become more variable. In addition to helping maintain the therapeutic alliance, nuanced psychotherapy by a trained professional can be transformational by helping patients to:

- process complex life events and emotions

- feel understood

- overcome psychological barriers to recovery

- enhance self-esteem.

When providing psychotherapy for adult patients, consider these basic, but salient points that are often overlooked.

Refrain from making life decisions for patients, except in exceptional circumstances, such as in situations of abuse and other crises.1 Telling an adult patient what to do about life decisions that he finds challenging fits more under life coaching than psychotherapy. Through therapy, patients should be helped in processing the pros and cons of certain decisions and in navigating the decision-making process to arrive at a decision that makes the most sense to them. Also, it’s not uncommon for therapeutic relationships to rupture when therapists give advice such as suggesting that a patient divorce his spouse, date a certain individual, or have children.

There are many reasons why giving advice in psychotherapy is not recommended. Giving advice can be an impediment to the therapeutic process.2 What is good advice for one patient may not be good for another. Therapists who give advice often do so from their own lens and perspective. This perspective may not only be different from the patient’s priorities and life circumstances, but the therapist also may have inadequate information about the patient’s situation,1,2 which could lead to providing advice that could even harm the patient. In addition, providing advice might prevent a patient from gaining adequate agency or self-directedness while promoting an unhealthy dependence on the therapist and reinforcing the patient’s self-doubt or lack of confidence. In these cases, the patient may later resent the therapist for the advice.

Address the ‘here and now.’1 Pay attention to immediate issues or themes that emerge, and address them with the patient gently and thoughtfully, as appropriate. Ignoring these may create risks of missing vital, underlying material that could reveal more of the patient’s inner world, as these themes can sometimes reflect other themes of the patient’s life outside of treatment.

Acknowledging and empathizing, when appropriate, are key initial steps that help decrease resistance and facilitate the therapeutic process.

Explore the affect. Paying attention to the patient’s emotional state is critical.3 This holds true for all types of psychotherapy. For example, if a patient suddenly becomes tearful when telling his story or describing recent events, this is usually a sign that the subject matter affects or holds value to the patient in a significant or meaningful way and should be further explored.

‘Meet the patient where they are.’ This doesn’t mean you should yield to the patient or give in to his demands. It implies that you should assess the patient’s readiness for a particular intervention and devise interventions from that standpoint, exploring the patient’s ambivalence, noticing resistance, and continuing to acknowledge and empathize with where the patient is in life or treatment. When utilized judiciously, this technique can help the therapist align with the patient, and help the patient move forward through resistance and ambivalence.

Be nonjudgmental and empathetic. Patients place trust in their therapists when they disclose thoughts or emotions that are sensitive, meaningful, or close to the heart. A nonjudgmental response helps the patient accept his experiences and emotions. Being empathetic requires putting oneself in another’s shoes; it does not mean agreeing with the patient. Of course, if you learn that your patient abused a child or an older adult, you are required to report it to the appropriate state agency. In addition, follow the duty to warn and protect in case of any other safety issues, as appropriate.

Do not assume. Open-ended questions and exploration are key. For example, a patient told her resident therapist that her father recently passed away. The therapist expressed to the patient how hard this must be for her. However, the patient said she was relieved by her father’s death, because he had been abusive to her for years. Because of the therapist’s comment, the patient doubted her own reaction and felt guilty for not being more upset about her father’s death.

Avoid over-identifying with your patient. If you find yourself over-identifying with a patient because you have a common background or life events, seek supervision. Over-identification not only can pose barriers to objectively identifying patterns and trends in the patient’s behavior or presentation but also can increase the risk of crossing boundaries or even minimizing the patient’s experience. Exercise caution if you find yourself wanting to be liked by your patient; this is a common mistake among beginning therapists.4

Seek supervision. If you are feeling angry, frustrated, indifferent, or overly attached toward a patient, recognize this countertransference and seek consultation or supervision from an experienced colleague or supervisor. These emotions can be valuable tools that shed light not only on the patient’s life and the session itself, but also help you identify any other factors, such as your own feelings or experiences, that might be contributing to these reactions.

1. Yalom ID. The gift of therapy: an open letter to a new generation of therapists and their patients. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 2002:46-73,142-145.

2. Bender S, Messner E. Management of impasses. In: Bender S, Messner E. Becoming a therapist: what do I say, and why? New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2003:235-258.

3.

4. Buckley P, Karasu TB, Charles E. Common mistakes in psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(12):1578-1580.

Although the biological aspects of psychiatry are crucial, psychotherapy is an integral part of psychiatry. Unfortunately, the emphasis on psychotherapy training in psychiatry residency programs has declined compared with a decade or more ago. In an era of dwindling psychotherapy training and resources, the quality and type of psychotherapy training has become more variable. In addition to helping maintain the therapeutic alliance, nuanced psychotherapy by a trained professional can be transformational by helping patients to:

- process complex life events and emotions

- feel understood

- overcome psychological barriers to recovery

- enhance self-esteem.

When providing psychotherapy for adult patients, consider these basic, but salient points that are often overlooked.

Refrain from making life decisions for patients, except in exceptional circumstances, such as in situations of abuse and other crises.1 Telling an adult patient what to do about life decisions that he finds challenging fits more under life coaching than psychotherapy. Through therapy, patients should be helped in processing the pros and cons of certain decisions and in navigating the decision-making process to arrive at a decision that makes the most sense to them. Also, it’s not uncommon for therapeutic relationships to rupture when therapists give advice such as suggesting that a patient divorce his spouse, date a certain individual, or have children.

There are many reasons why giving advice in psychotherapy is not recommended. Giving advice can be an impediment to the therapeutic process.2 What is good advice for one patient may not be good for another. Therapists who give advice often do so from their own lens and perspective. This perspective may not only be different from the patient’s priorities and life circumstances, but the therapist also may have inadequate information about the patient’s situation,1,2 which could lead to providing advice that could even harm the patient. In addition, providing advice might prevent a patient from gaining adequate agency or self-directedness while promoting an unhealthy dependence on the therapist and reinforcing the patient’s self-doubt or lack of confidence. In these cases, the patient may later resent the therapist for the advice.

Address the ‘here and now.’1 Pay attention to immediate issues or themes that emerge, and address them with the patient gently and thoughtfully, as appropriate. Ignoring these may create risks of missing vital, underlying material that could reveal more of the patient’s inner world, as these themes can sometimes reflect other themes of the patient’s life outside of treatment.

Acknowledging and empathizing, when appropriate, are key initial steps that help decrease resistance and facilitate the therapeutic process.

Explore the affect. Paying attention to the patient’s emotional state is critical.3 This holds true for all types of psychotherapy. For example, if a patient suddenly becomes tearful when telling his story or describing recent events, this is usually a sign that the subject matter affects or holds value to the patient in a significant or meaningful way and should be further explored.

‘Meet the patient where they are.’ This doesn’t mean you should yield to the patient or give in to his demands. It implies that you should assess the patient’s readiness for a particular intervention and devise interventions from that standpoint, exploring the patient’s ambivalence, noticing resistance, and continuing to acknowledge and empathize with where the patient is in life or treatment. When utilized judiciously, this technique can help the therapist align with the patient, and help the patient move forward through resistance and ambivalence.

Be nonjudgmental and empathetic. Patients place trust in their therapists when they disclose thoughts or emotions that are sensitive, meaningful, or close to the heart. A nonjudgmental response helps the patient accept his experiences and emotions. Being empathetic requires putting oneself in another’s shoes; it does not mean agreeing with the patient. Of course, if you learn that your patient abused a child or an older adult, you are required to report it to the appropriate state agency. In addition, follow the duty to warn and protect in case of any other safety issues, as appropriate.

Do not assume. Open-ended questions and exploration are key. For example, a patient told her resident therapist that her father recently passed away. The therapist expressed to the patient how hard this must be for her. However, the patient said she was relieved by her father’s death, because he had been abusive to her for years. Because of the therapist’s comment, the patient doubted her own reaction and felt guilty for not being more upset about her father’s death.

Avoid over-identifying with your patient. If you find yourself over-identifying with a patient because you have a common background or life events, seek supervision. Over-identification not only can pose barriers to objectively identifying patterns and trends in the patient’s behavior or presentation but also can increase the risk of crossing boundaries or even minimizing the patient’s experience. Exercise caution if you find yourself wanting to be liked by your patient; this is a common mistake among beginning therapists.4

Seek supervision. If you are feeling angry, frustrated, indifferent, or overly attached toward a patient, recognize this countertransference and seek consultation or supervision from an experienced colleague or supervisor. These emotions can be valuable tools that shed light not only on the patient’s life and the session itself, but also help you identify any other factors, such as your own feelings or experiences, that might be contributing to these reactions.

Although the biological aspects of psychiatry are crucial, psychotherapy is an integral part of psychiatry. Unfortunately, the emphasis on psychotherapy training in psychiatry residency programs has declined compared with a decade or more ago. In an era of dwindling psychotherapy training and resources, the quality and type of psychotherapy training has become more variable. In addition to helping maintain the therapeutic alliance, nuanced psychotherapy by a trained professional can be transformational by helping patients to:

- process complex life events and emotions

- feel understood

- overcome psychological barriers to recovery

- enhance self-esteem.

When providing psychotherapy for adult patients, consider these basic, but salient points that are often overlooked.

Refrain from making life decisions for patients, except in exceptional circumstances, such as in situations of abuse and other crises.1 Telling an adult patient what to do about life decisions that he finds challenging fits more under life coaching than psychotherapy. Through therapy, patients should be helped in processing the pros and cons of certain decisions and in navigating the decision-making process to arrive at a decision that makes the most sense to them. Also, it’s not uncommon for therapeutic relationships to rupture when therapists give advice such as suggesting that a patient divorce his spouse, date a certain individual, or have children.

There are many reasons why giving advice in psychotherapy is not recommended. Giving advice can be an impediment to the therapeutic process.2 What is good advice for one patient may not be good for another. Therapists who give advice often do so from their own lens and perspective. This perspective may not only be different from the patient’s priorities and life circumstances, but the therapist also may have inadequate information about the patient’s situation,1,2 which could lead to providing advice that could even harm the patient. In addition, providing advice might prevent a patient from gaining adequate agency or self-directedness while promoting an unhealthy dependence on the therapist and reinforcing the patient’s self-doubt or lack of confidence. In these cases, the patient may later resent the therapist for the advice.

Address the ‘here and now.’1 Pay attention to immediate issues or themes that emerge, and address them with the patient gently and thoughtfully, as appropriate. Ignoring these may create risks of missing vital, underlying material that could reveal more of the patient’s inner world, as these themes can sometimes reflect other themes of the patient’s life outside of treatment.

Acknowledging and empathizing, when appropriate, are key initial steps that help decrease resistance and facilitate the therapeutic process.

Explore the affect. Paying attention to the patient’s emotional state is critical.3 This holds true for all types of psychotherapy. For example, if a patient suddenly becomes tearful when telling his story or describing recent events, this is usually a sign that the subject matter affects or holds value to the patient in a significant or meaningful way and should be further explored.

‘Meet the patient where they are.’ This doesn’t mean you should yield to the patient or give in to his demands. It implies that you should assess the patient’s readiness for a particular intervention and devise interventions from that standpoint, exploring the patient’s ambivalence, noticing resistance, and continuing to acknowledge and empathize with where the patient is in life or treatment. When utilized judiciously, this technique can help the therapist align with the patient, and help the patient move forward through resistance and ambivalence.

Be nonjudgmental and empathetic. Patients place trust in their therapists when they disclose thoughts or emotions that are sensitive, meaningful, or close to the heart. A nonjudgmental response helps the patient accept his experiences and emotions. Being empathetic requires putting oneself in another’s shoes; it does not mean agreeing with the patient. Of course, if you learn that your patient abused a child or an older adult, you are required to report it to the appropriate state agency. In addition, follow the duty to warn and protect in case of any other safety issues, as appropriate.

Do not assume. Open-ended questions and exploration are key. For example, a patient told her resident therapist that her father recently passed away. The therapist expressed to the patient how hard this must be for her. However, the patient said she was relieved by her father’s death, because he had been abusive to her for years. Because of the therapist’s comment, the patient doubted her own reaction and felt guilty for not being more upset about her father’s death.

Avoid over-identifying with your patient. If you find yourself over-identifying with a patient because you have a common background or life events, seek supervision. Over-identification not only can pose barriers to objectively identifying patterns and trends in the patient’s behavior or presentation but also can increase the risk of crossing boundaries or even minimizing the patient’s experience. Exercise caution if you find yourself wanting to be liked by your patient; this is a common mistake among beginning therapists.4

Seek supervision. If you are feeling angry, frustrated, indifferent, or overly attached toward a patient, recognize this countertransference and seek consultation or supervision from an experienced colleague or supervisor. These emotions can be valuable tools that shed light not only on the patient’s life and the session itself, but also help you identify any other factors, such as your own feelings or experiences, that might be contributing to these reactions.

1. Yalom ID. The gift of therapy: an open letter to a new generation of therapists and their patients. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 2002:46-73,142-145.

2. Bender S, Messner E. Management of impasses. In: Bender S, Messner E. Becoming a therapist: what do I say, and why? New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2003:235-258.

3.

4. Buckley P, Karasu TB, Charles E. Common mistakes in psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(12):1578-1580.

1. Yalom ID. The gift of therapy: an open letter to a new generation of therapists and their patients. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers; 2002:46-73,142-145.

2. Bender S, Messner E. Management of impasses. In: Bender S, Messner E. Becoming a therapist: what do I say, and why? New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2003:235-258.

3.

4. Buckley P, Karasu TB, Charles E. Common mistakes in psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(12):1578-1580.

Use the ABCs when managing problem behaviors in autism

Despite a lack of evidence, polypharmacy often is used to treat autism spectrum disorder (ASD),1 while educational techniques are underutilized. Compared with the general population, children with ASD may be more prone to the adverse effects of the medications used to treat symptoms, such as antipsychotics and antidepressants.2 Therefore, when addressing problem behaviors, such as tantrums, aggressiveness, or self-injury, in a patient with ASD, before prescribing a medication, consider the ABCs of these behaviors.3

Antecedents. What happened before the behavior occurred? Where and when did the behavior occur? Was the individual unable to get a desired tangible item, such as a preferred food, toy, or another object? Was the individual told complete a task that he (she) did not want to do? Did the individual see someone else getting attention?

Behaviors. What behavior(s) occurred after each antecedent?

Consequences. What happened after the behavior occurred? Did the caregiver give the individual the item he wanted? Was the individual able to get out of doing work that he did not want to do or become the center of attention?

Having parents document the ABCs is useful not only for finding out why a behavior occurred, but also for objectively determining if and how a medication is affecting the frequency of a behavior. Charts that parents can use to document ABC data are available online (eg, http://www.positivelyautism.com/downloads/datasheet_abc.pdf). Once this data is collected, it can be used to implement appropriate interventions, which I describe as DEFG.

Differential reinforcement of other behaviors is a procedure that provides positive reinforcement for not engaging in a problem behavior or for staying on task. For example, use a token board to reward positive behaviors, with physical tokens or written marks. However, some patients require immediate reinforcement. I suggest that parents or caregivers carry small pieces of preferred food to give to the patient to reinforce positive behavior.

Exercise. A review of 18 studies reported that physical exercise, such as jogging, weight training, and bike riding, can help reduce problem behaviors in individuals with ASD.4 Among 64 participants with ASD, there was a decrease in aggression, stereotypy, off-task behavior, and elopement, and improvements in on-task and motor behavior such as playing catch.

Function. Refer to the ABCs to determine why a specific problem behavior is occurring. Each behavior can have 1 or multiple functions; therefore, develop a plan specific to the reason the patient engages in the behavior. For example, if the individual engages in a behavior to avoid a task, the parent or caregiver can give individual tokens that the individual can later exchange for a break, instead of engaging in the problem behavior to avoid the task. If a behavior appears to be done for attention, instruct the caregivers to provide frequent periods of attention when the individual engages in positive behaviors.

Go to the appropriate placement. By law, persons age ≤21 have the right to an education and to make meaningful progress. If a patient with ASD exhibits behaviors that interfere with learning, he is entitled to a placement that can provide intensive applied behavior analysis. If you feel that the child needs a different school, write an evaluation for the parent or guardian to submit to the school district and clearly outline the patient’s needs and requirements.

1. Spencer D, Marshall J, Post B, et al. Psychotropic medication use and polypharmacy in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):833-840.

2. Azeem MW, Imran N, Khawaja IS. Autism spectrum disorder: an update. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(1):58-62.

3. Pratt C, Dubie M. Observing behavior using A-B-C data. Indiana Resource Center for Autism. https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/pages/observing-behavior-using-a-b-c-data. Accessed October 4, 2017.

4. Lang R, Kern Koegel LK, Ashbaugh K, et al. Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Res Autism Spectr Dis. 2010;4(4):565-576.

Despite a lack of evidence, polypharmacy often is used to treat autism spectrum disorder (ASD),1 while educational techniques are underutilized. Compared with the general population, children with ASD may be more prone to the adverse effects of the medications used to treat symptoms, such as antipsychotics and antidepressants.2 Therefore, when addressing problem behaviors, such as tantrums, aggressiveness, or self-injury, in a patient with ASD, before prescribing a medication, consider the ABCs of these behaviors.3

Antecedents. What happened before the behavior occurred? Where and when did the behavior occur? Was the individual unable to get a desired tangible item, such as a preferred food, toy, or another object? Was the individual told complete a task that he (she) did not want to do? Did the individual see someone else getting attention?

Behaviors. What behavior(s) occurred after each antecedent?

Consequences. What happened after the behavior occurred? Did the caregiver give the individual the item he wanted? Was the individual able to get out of doing work that he did not want to do or become the center of attention?

Having parents document the ABCs is useful not only for finding out why a behavior occurred, but also for objectively determining if and how a medication is affecting the frequency of a behavior. Charts that parents can use to document ABC data are available online (eg, http://www.positivelyautism.com/downloads/datasheet_abc.pdf). Once this data is collected, it can be used to implement appropriate interventions, which I describe as DEFG.

Differential reinforcement of other behaviors is a procedure that provides positive reinforcement for not engaging in a problem behavior or for staying on task. For example, use a token board to reward positive behaviors, with physical tokens or written marks. However, some patients require immediate reinforcement. I suggest that parents or caregivers carry small pieces of preferred food to give to the patient to reinforce positive behavior.

Exercise. A review of 18 studies reported that physical exercise, such as jogging, weight training, and bike riding, can help reduce problem behaviors in individuals with ASD.4 Among 64 participants with ASD, there was a decrease in aggression, stereotypy, off-task behavior, and elopement, and improvements in on-task and motor behavior such as playing catch.

Function. Refer to the ABCs to determine why a specific problem behavior is occurring. Each behavior can have 1 or multiple functions; therefore, develop a plan specific to the reason the patient engages in the behavior. For example, if the individual engages in a behavior to avoid a task, the parent or caregiver can give individual tokens that the individual can later exchange for a break, instead of engaging in the problem behavior to avoid the task. If a behavior appears to be done for attention, instruct the caregivers to provide frequent periods of attention when the individual engages in positive behaviors.

Go to the appropriate placement. By law, persons age ≤21 have the right to an education and to make meaningful progress. If a patient with ASD exhibits behaviors that interfere with learning, he is entitled to a placement that can provide intensive applied behavior analysis. If you feel that the child needs a different school, write an evaluation for the parent or guardian to submit to the school district and clearly outline the patient’s needs and requirements.

Despite a lack of evidence, polypharmacy often is used to treat autism spectrum disorder (ASD),1 while educational techniques are underutilized. Compared with the general population, children with ASD may be more prone to the adverse effects of the medications used to treat symptoms, such as antipsychotics and antidepressants.2 Therefore, when addressing problem behaviors, such as tantrums, aggressiveness, or self-injury, in a patient with ASD, before prescribing a medication, consider the ABCs of these behaviors.3

Antecedents. What happened before the behavior occurred? Where and when did the behavior occur? Was the individual unable to get a desired tangible item, such as a preferred food, toy, or another object? Was the individual told complete a task that he (she) did not want to do? Did the individual see someone else getting attention?

Behaviors. What behavior(s) occurred after each antecedent?

Consequences. What happened after the behavior occurred? Did the caregiver give the individual the item he wanted? Was the individual able to get out of doing work that he did not want to do or become the center of attention?

Having parents document the ABCs is useful not only for finding out why a behavior occurred, but also for objectively determining if and how a medication is affecting the frequency of a behavior. Charts that parents can use to document ABC data are available online (eg, http://www.positivelyautism.com/downloads/datasheet_abc.pdf). Once this data is collected, it can be used to implement appropriate interventions, which I describe as DEFG.

Differential reinforcement of other behaviors is a procedure that provides positive reinforcement for not engaging in a problem behavior or for staying on task. For example, use a token board to reward positive behaviors, with physical tokens or written marks. However, some patients require immediate reinforcement. I suggest that parents or caregivers carry small pieces of preferred food to give to the patient to reinforce positive behavior.

Exercise. A review of 18 studies reported that physical exercise, such as jogging, weight training, and bike riding, can help reduce problem behaviors in individuals with ASD.4 Among 64 participants with ASD, there was a decrease in aggression, stereotypy, off-task behavior, and elopement, and improvements in on-task and motor behavior such as playing catch.

Function. Refer to the ABCs to determine why a specific problem behavior is occurring. Each behavior can have 1 or multiple functions; therefore, develop a plan specific to the reason the patient engages in the behavior. For example, if the individual engages in a behavior to avoid a task, the parent or caregiver can give individual tokens that the individual can later exchange for a break, instead of engaging in the problem behavior to avoid the task. If a behavior appears to be done for attention, instruct the caregivers to provide frequent periods of attention when the individual engages in positive behaviors.

Go to the appropriate placement. By law, persons age ≤21 have the right to an education and to make meaningful progress. If a patient with ASD exhibits behaviors that interfere with learning, he is entitled to a placement that can provide intensive applied behavior analysis. If you feel that the child needs a different school, write an evaluation for the parent or guardian to submit to the school district and clearly outline the patient’s needs and requirements.

1. Spencer D, Marshall J, Post B, et al. Psychotropic medication use and polypharmacy in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):833-840.

2. Azeem MW, Imran N, Khawaja IS. Autism spectrum disorder: an update. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(1):58-62.

3. Pratt C, Dubie M. Observing behavior using A-B-C data. Indiana Resource Center for Autism. https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/pages/observing-behavior-using-a-b-c-data. Accessed October 4, 2017.

4. Lang R, Kern Koegel LK, Ashbaugh K, et al. Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Res Autism Spectr Dis. 2010;4(4):565-576.

1. Spencer D, Marshall J, Post B, et al. Psychotropic medication use and polypharmacy in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):833-840.

2. Azeem MW, Imran N, Khawaja IS. Autism spectrum disorder: an update. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46(1):58-62.

3. Pratt C, Dubie M. Observing behavior using A-B-C data. Indiana Resource Center for Autism. https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/pages/observing-behavior-using-a-b-c-data. Accessed October 4, 2017.

4. Lang R, Kern Koegel LK, Ashbaugh K, et al. Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Res Autism Spectr Dis. 2010;4(4):565-576.

Employment contracts: What to check before you sign

Most psychiatrists are required to sign an employment contract before taking a job, but few of us have received any training on reviewing such contracts. We often rely on coworkers and attorneys to navigate this process for us. However, the contract is crucial, because it outlines your employer’s clinical and administrative expectations for the position, and it gives you the opportunity to lay out what you want.1 Because an employment contract is legally binding, you should thoroughly read it and look for clauses that may not work in your best interest. Although not a complete list, the following items should be reviewed before signing a contract.1,2

Benefits. Make sure you are offered a reasonable salary, but balance the dollar amount with benefits such as:

- continuing medical education allowances

- educational loan forgiveness

- health/malpractice/disability insurance

- retirement benefits

- compensation for call schedule.

In some cases, there may be a delay before you are eligible to obtain certain benefits.

Work expectations. Many contracts state that the position is “full-time” or have other nonspecific parameters for work expectations. You should inquire about objective work parameters, such as duty hours, the average frequency of the current call schedule, timeframe for completing medical documentation, and penalties for not meeting clinical or administrative requirements, so you are not surprised by:

- working longer-than-planned shifts

- performing on-call duties

- working on days that you were not expecting

- having your credentialing status placed in jeopardy.

Some group practices allow for a half-day of no scheduled appointments with patients, so you can complete paperwork and return phone calls.

Noncompete clause. This restricts you from working within a certain geographic area or for a competing employer for a finite time period after the contract terminates or expires. A noncompete clause could restrict you from practicing within a large geographical area, especially if the job is located in a densely populated area. Some noncompete clauses do not include a temporal or geographic restriction, but can limit your ability to bring patients with you to a new practice or facility when the contract expires.

Malpractice insurance. Two types of malpractice insurance are occurrence and claims-made:

- Occurrence insurance protects you whenever an action is brought against you, even if the action is brought after the contract terminates or expires.

- Claims-made insurance provides coverage if the policy with the same insurer was in effect when the malpractice was committed and when the actual action was commenced.

Although claims-made insurance is less expensive, it can leave you without coverage should you leave your employer and no longer maintain the same insurance policy. Claims-made can be converted into occurrence through the purchase of a tail endorsement. If the employer does not offer you tail coverage, then it is your responsibility to pay for this insurance, which can be expensive.

Termination language. Every contract features a termination section that lists potential causes for terminating your employment. This list is usually not exhaustive, but it sets the framework for a realistic view of reasonable causes. Contracts also commonly contain provisions that permit termination “without cause” after notice of termination is provided. Although you could negotiate for more notice time, “without cause” clauses are unlikely to be removed from the contract.

1. Claussen K. Eight physician employment contract items you need to know about. The Doctor Weighs In. https://thedoctorweighsin.com/8-physician-employment-contract-items-you-need-to-know-about. Published March 8, 2017. Accessed October 11, 2017.

2. Blustein AE, Keller LB. Physician employment contracts: what you need to know before you sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://www.aad.org/members/publications/directions-in-residency/archiveyment-contracts-what-you-need-to-know-before-you-sign. Accessed October 11, 2017.

Most psychiatrists are required to sign an employment contract before taking a job, but few of us have received any training on reviewing such contracts. We often rely on coworkers and attorneys to navigate this process for us. However, the contract is crucial, because it outlines your employer’s clinical and administrative expectations for the position, and it gives you the opportunity to lay out what you want.1 Because an employment contract is legally binding, you should thoroughly read it and look for clauses that may not work in your best interest. Although not a complete list, the following items should be reviewed before signing a contract.1,2

Benefits. Make sure you are offered a reasonable salary, but balance the dollar amount with benefits such as:

- continuing medical education allowances

- educational loan forgiveness

- health/malpractice/disability insurance

- retirement benefits

- compensation for call schedule.

In some cases, there may be a delay before you are eligible to obtain certain benefits.

Work expectations. Many contracts state that the position is “full-time” or have other nonspecific parameters for work expectations. You should inquire about objective work parameters, such as duty hours, the average frequency of the current call schedule, timeframe for completing medical documentation, and penalties for not meeting clinical or administrative requirements, so you are not surprised by:

- working longer-than-planned shifts

- performing on-call duties

- working on days that you were not expecting

- having your credentialing status placed in jeopardy.

Some group practices allow for a half-day of no scheduled appointments with patients, so you can complete paperwork and return phone calls.

Noncompete clause. This restricts you from working within a certain geographic area or for a competing employer for a finite time period after the contract terminates or expires. A noncompete clause could restrict you from practicing within a large geographical area, especially if the job is located in a densely populated area. Some noncompete clauses do not include a temporal or geographic restriction, but can limit your ability to bring patients with you to a new practice or facility when the contract expires.

Malpractice insurance. Two types of malpractice insurance are occurrence and claims-made:

- Occurrence insurance protects you whenever an action is brought against you, even if the action is brought after the contract terminates or expires.

- Claims-made insurance provides coverage if the policy with the same insurer was in effect when the malpractice was committed and when the actual action was commenced.

Although claims-made insurance is less expensive, it can leave you without coverage should you leave your employer and no longer maintain the same insurance policy. Claims-made can be converted into occurrence through the purchase of a tail endorsement. If the employer does not offer you tail coverage, then it is your responsibility to pay for this insurance, which can be expensive.

Termination language. Every contract features a termination section that lists potential causes for terminating your employment. This list is usually not exhaustive, but it sets the framework for a realistic view of reasonable causes. Contracts also commonly contain provisions that permit termination “without cause” after notice of termination is provided. Although you could negotiate for more notice time, “without cause” clauses are unlikely to be removed from the contract.

Most psychiatrists are required to sign an employment contract before taking a job, but few of us have received any training on reviewing such contracts. We often rely on coworkers and attorneys to navigate this process for us. However, the contract is crucial, because it outlines your employer’s clinical and administrative expectations for the position, and it gives you the opportunity to lay out what you want.1 Because an employment contract is legally binding, you should thoroughly read it and look for clauses that may not work in your best interest. Although not a complete list, the following items should be reviewed before signing a contract.1,2

Benefits. Make sure you are offered a reasonable salary, but balance the dollar amount with benefits such as:

- continuing medical education allowances

- educational loan forgiveness

- health/malpractice/disability insurance

- retirement benefits

- compensation for call schedule.

In some cases, there may be a delay before you are eligible to obtain certain benefits.

Work expectations. Many contracts state that the position is “full-time” or have other nonspecific parameters for work expectations. You should inquire about objective work parameters, such as duty hours, the average frequency of the current call schedule, timeframe for completing medical documentation, and penalties for not meeting clinical or administrative requirements, so you are not surprised by:

- working longer-than-planned shifts

- performing on-call duties

- working on days that you were not expecting

- having your credentialing status placed in jeopardy.

Some group practices allow for a half-day of no scheduled appointments with patients, so you can complete paperwork and return phone calls.

Noncompete clause. This restricts you from working within a certain geographic area or for a competing employer for a finite time period after the contract terminates or expires. A noncompete clause could restrict you from practicing within a large geographical area, especially if the job is located in a densely populated area. Some noncompete clauses do not include a temporal or geographic restriction, but can limit your ability to bring patients with you to a new practice or facility when the contract expires.

Malpractice insurance. Two types of malpractice insurance are occurrence and claims-made:

- Occurrence insurance protects you whenever an action is brought against you, even if the action is brought after the contract terminates or expires.

- Claims-made insurance provides coverage if the policy with the same insurer was in effect when the malpractice was committed and when the actual action was commenced.

Although claims-made insurance is less expensive, it can leave you without coverage should you leave your employer and no longer maintain the same insurance policy. Claims-made can be converted into occurrence through the purchase of a tail endorsement. If the employer does not offer you tail coverage, then it is your responsibility to pay for this insurance, which can be expensive.

Termination language. Every contract features a termination section that lists potential causes for terminating your employment. This list is usually not exhaustive, but it sets the framework for a realistic view of reasonable causes. Contracts also commonly contain provisions that permit termination “without cause” after notice of termination is provided. Although you could negotiate for more notice time, “without cause” clauses are unlikely to be removed from the contract.

1. Claussen K. Eight physician employment contract items you need to know about. The Doctor Weighs In. https://thedoctorweighsin.com/8-physician-employment-contract-items-you-need-to-know-about. Published March 8, 2017. Accessed October 11, 2017.

2. Blustein AE, Keller LB. Physician employment contracts: what you need to know before you sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://www.aad.org/members/publications/directions-in-residency/archiveyment-contracts-what-you-need-to-know-before-you-sign. Accessed October 11, 2017.

1. Claussen K. Eight physician employment contract items you need to know about. The Doctor Weighs In. https://thedoctorweighsin.com/8-physician-employment-contract-items-you-need-to-know-about. Published March 8, 2017. Accessed October 11, 2017.

2. Blustein AE, Keller LB. Physician employment contracts: what you need to know before you sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://www.aad.org/members/publications/directions-in-residency/archiveyment-contracts-what-you-need-to-know-before-you-sign. Accessed October 11, 2017.

3 Approaches to PMS

Throughout my 40 years in private psychiatric practice, I have found some treatments for premenstrual syndrome (PMS) that were not mentioned in “Etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces” (Evidence-Based Reviews, Current Psychiatry. September 2017, p. 20-28).

This started in 1972 when I was serving in the Army in Oklahoma. A 28-year-old woman with severe PMS had been treated by internal medicine, an OB/GYN, and endocrinology, all to no avail. Three days before her menses began, she would start driving north. When menses commenced, she would find herself in Nebraska and have to call her husband so he could wire her money to come back.

Through my evaluation, I found that she would gain 10 lb before her menses. I prescribed a diuretic and instructed her to start taking it when she began swelling and to stop taking it after her menses began. This alleviated all of her symptoms. If a woman gains more than 3 to 5 lb, her brain also will swell, along with everything else. Because the brain is encapsulated in the skull, the swelling puts pressure on the brain, which might have been the cause of these brief psychotic episodes.

If a woman who develops PMS does not experience significant weight gain, the first thing I try is vitamin B6, 100 mg/d, prior to menses. Vitamin B6 is a cofactor in the production of numerous neurotransmitters. I found that prescribing vitamin B6 would alleviate about 20% of PMS symptoms. If the patient has a personal or family history of affective disorder, I often try antidepressants prior to menses, which alleviate approximately another 20% of her symptoms. If none of the previous 3 factors are present, I often add a low dose of progesterone, which appears to help. If all else fails, I will try a low dose of lithium, 300 mg/d, before menses. This also seems to have some positive effect.

I have not written an article about these approaches to PMS, although I have discussed them with OB/GYNs, who never seem to follow these recommendations. Because I am not university-based, I have not been able to put thes

Throughout my 40 years in private psychiatric practice, I have found some treatments for premenstrual syndrome (PMS) that were not mentioned in “Etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces” (Evidence-Based Reviews, Current Psychiatry. September 2017, p. 20-28).

This started in 1972 when I was serving in the Army in Oklahoma. A 28-year-old woman with severe PMS had been treated by internal medicine, an OB/GYN, and endocrinology, all to no avail. Three days before her menses began, she would start driving north. When menses commenced, she would find herself in Nebraska and have to call her husband so he could wire her money to come back.

Through my evaluation, I found that she would gain 10 lb before her menses. I prescribed a diuretic and instructed her to start taking it when she began swelling and to stop taking it after her menses began. This alleviated all of her symptoms. If a woman gains more than 3 to 5 lb, her brain also will swell, along with everything else. Because the brain is encapsulated in the skull, the swelling puts pressure on the brain, which might have been the cause of these brief psychotic episodes.

If a woman who develops PMS does not experience significant weight gain, the first thing I try is vitamin B6, 100 mg/d, prior to menses. Vitamin B6 is a cofactor in the production of numerous neurotransmitters. I found that prescribing vitamin B6 would alleviate about 20% of PMS symptoms. If the patient has a personal or family history of affective disorder, I often try antidepressants prior to menses, which alleviate approximately another 20% of her symptoms. If none of the previous 3 factors are present, I often add a low dose of progesterone, which appears to help. If all else fails, I will try a low dose of lithium, 300 mg/d, before menses. This also seems to have some positive effect.

I have not written an article about these approaches to PMS, although I have discussed them with OB/GYNs, who never seem to follow these recommendations. Because I am not university-based, I have not been able to put thes

Throughout my 40 years in private psychiatric practice, I have found some treatments for premenstrual syndrome (PMS) that were not mentioned in “Etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 5 interwoven pieces” (Evidence-Based Reviews, Current Psychiatry. September 2017, p. 20-28).

This started in 1972 when I was serving in the Army in Oklahoma. A 28-year-old woman with severe PMS had been treated by internal medicine, an OB/GYN, and endocrinology, all to no avail. Three days before her menses began, she would start driving north. When menses commenced, she would find herself in Nebraska and have to call her husband so he could wire her money to come back.

Through my evaluation, I found that she would gain 10 lb before her menses. I prescribed a diuretic and instructed her to start taking it when she began swelling and to stop taking it after her menses began. This alleviated all of her symptoms. If a woman gains more than 3 to 5 lb, her brain also will swell, along with everything else. Because the brain is encapsulated in the skull, the swelling puts pressure on the brain, which might have been the cause of these brief psychotic episodes.

If a woman who develops PMS does not experience significant weight gain, the first thing I try is vitamin B6, 100 mg/d, prior to menses. Vitamin B6 is a cofactor in the production of numerous neurotransmitters. I found that prescribing vitamin B6 would alleviate about 20% of PMS symptoms. If the patient has a personal or family history of affective disorder, I often try antidepressants prior to menses, which alleviate approximately another 20% of her symptoms. If none of the previous 3 factors are present, I often add a low dose of progesterone, which appears to help. If all else fails, I will try a low dose of lithium, 300 mg/d, before menses. This also seems to have some positive effect.

I have not written an article about these approaches to PMS, although I have discussed them with OB/GYNs, who never seem to follow these recommendations. Because I am not university-based, I have not been able to put thes

Prescribing antipsychotics in geriatric patients: Focus on schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

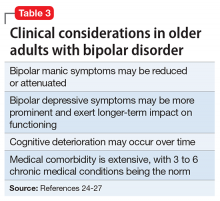

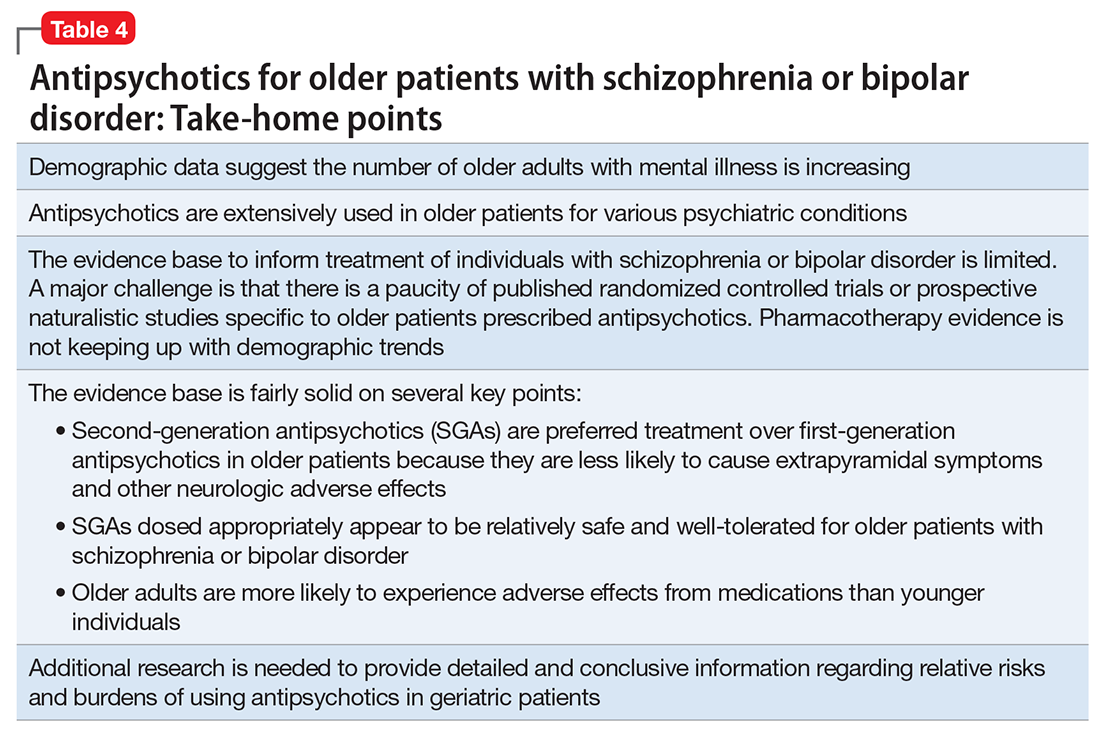

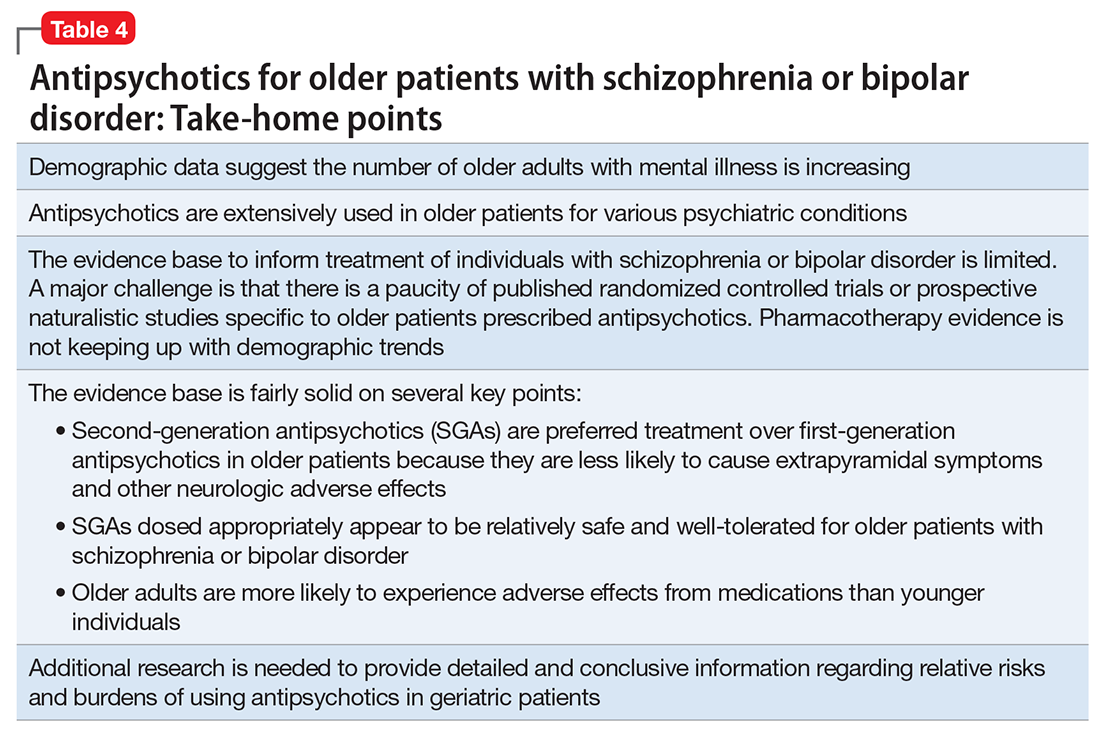

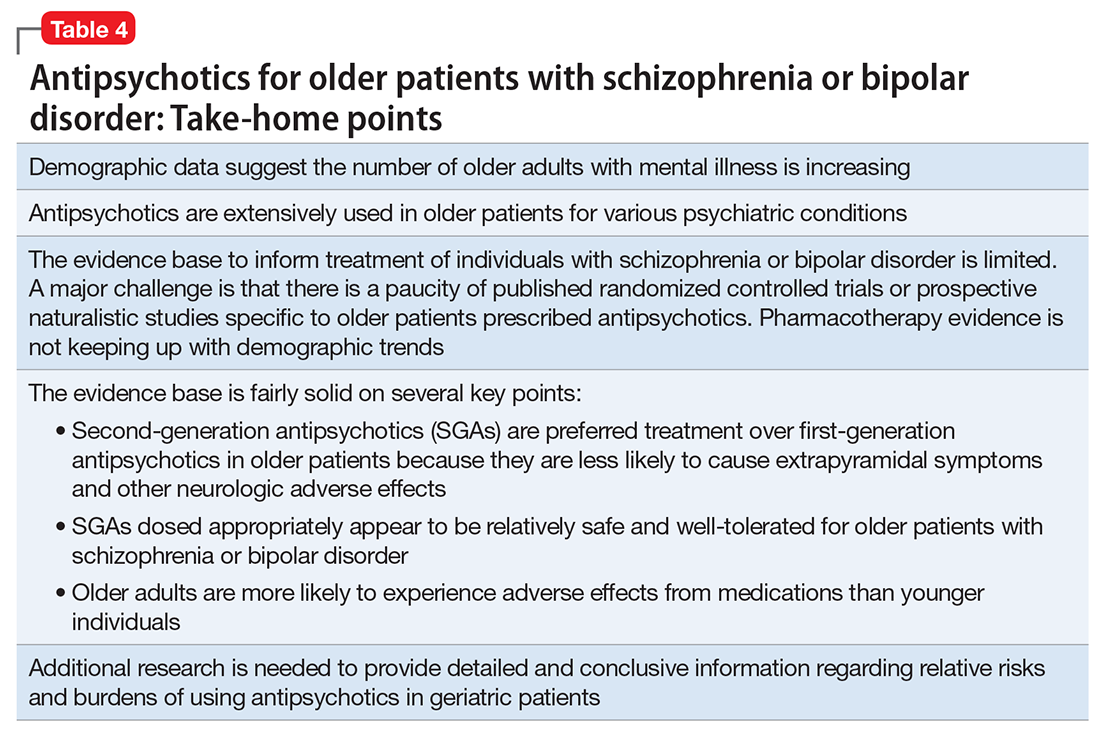

Antipsychotics are FDA-approved as a primary treatment for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and as adjunctive therapy for major depressive disorder. In the United States, approximately 26% of antipsychotic prescriptions written for these indications are for individuals age >65.1 Additionally, antipsychotics are widely used to treat behavioral symptoms associated with dementia.1 The rapid expansion of the use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), in particular, has been driven in part by their lower risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) compared with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs).1 However, a growing body of data indicates that all antipsychotics have a range of adverse effects in older patients. This focus is critical in light of demographic trends—in the next 10 to 15 years, the population age >60 will grow 3.5 times more rapidly than the general population.2

In this context, psychiatrists need information on the relative risks of antipsychotics for older patients. This 3-part series summarizes findings and recommendations on safety and tolerability when prescribing antipsychotics in older individuals with chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and dementia. This review aims to:

- briefly summarize the major studies and analyses relevant to older patients with these diagnoses

- provide a summative opinion on safety and tolerability issues in these older adults

- highlight the gaps in the evidence base and areas that need additional research.

Part 1 focuses on older adults with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Subsequent articles will focus on prescribing antipsychotics to older adults with depression and those with dementia.

Schizophrenia

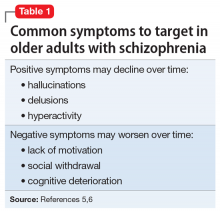

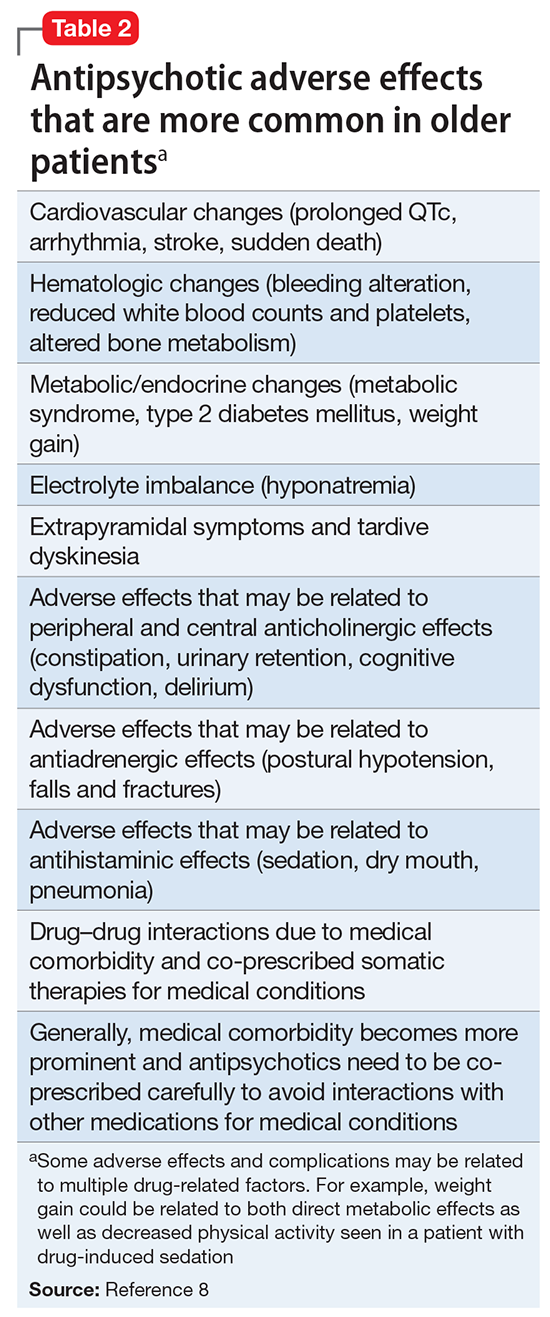

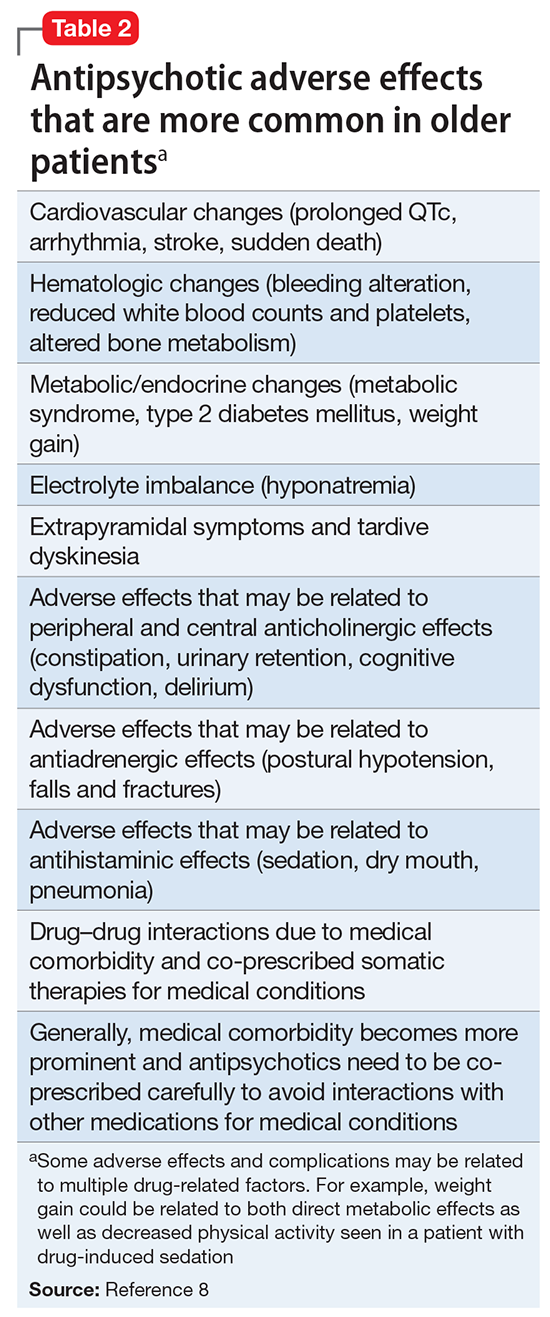

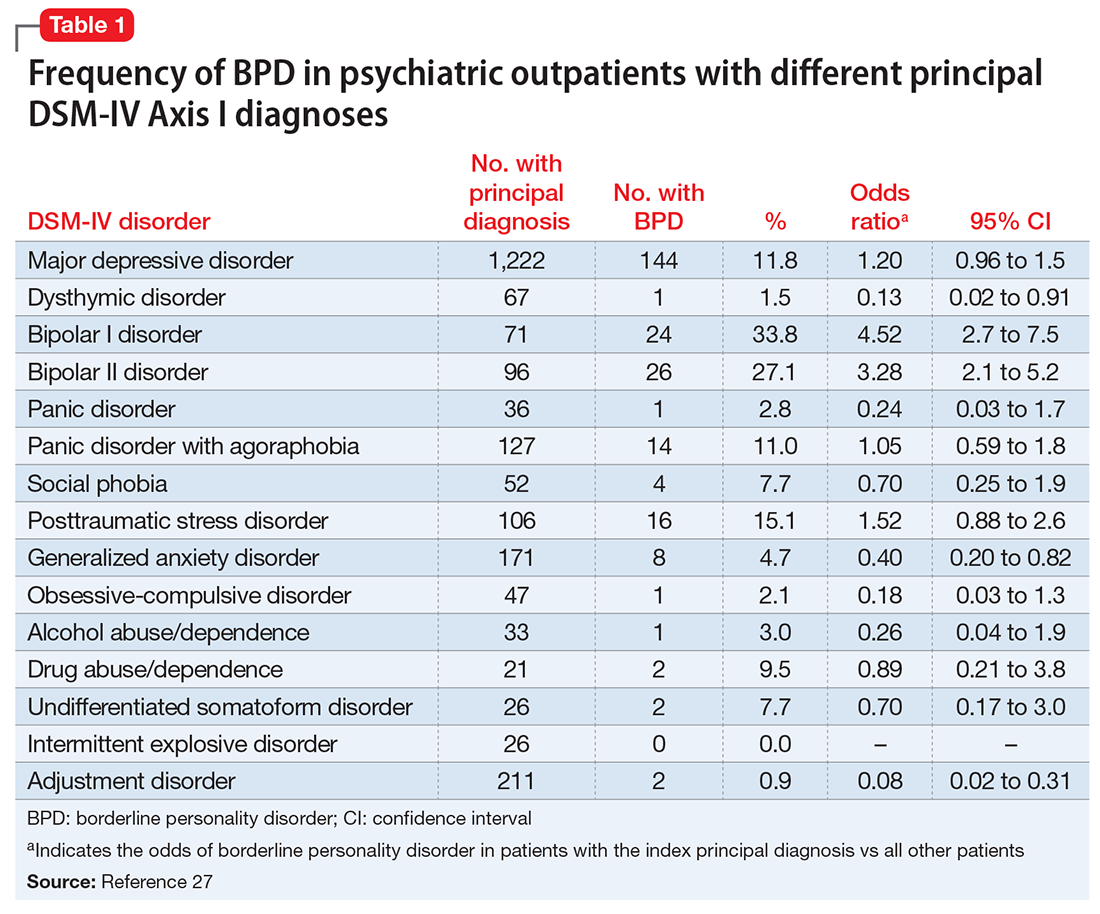

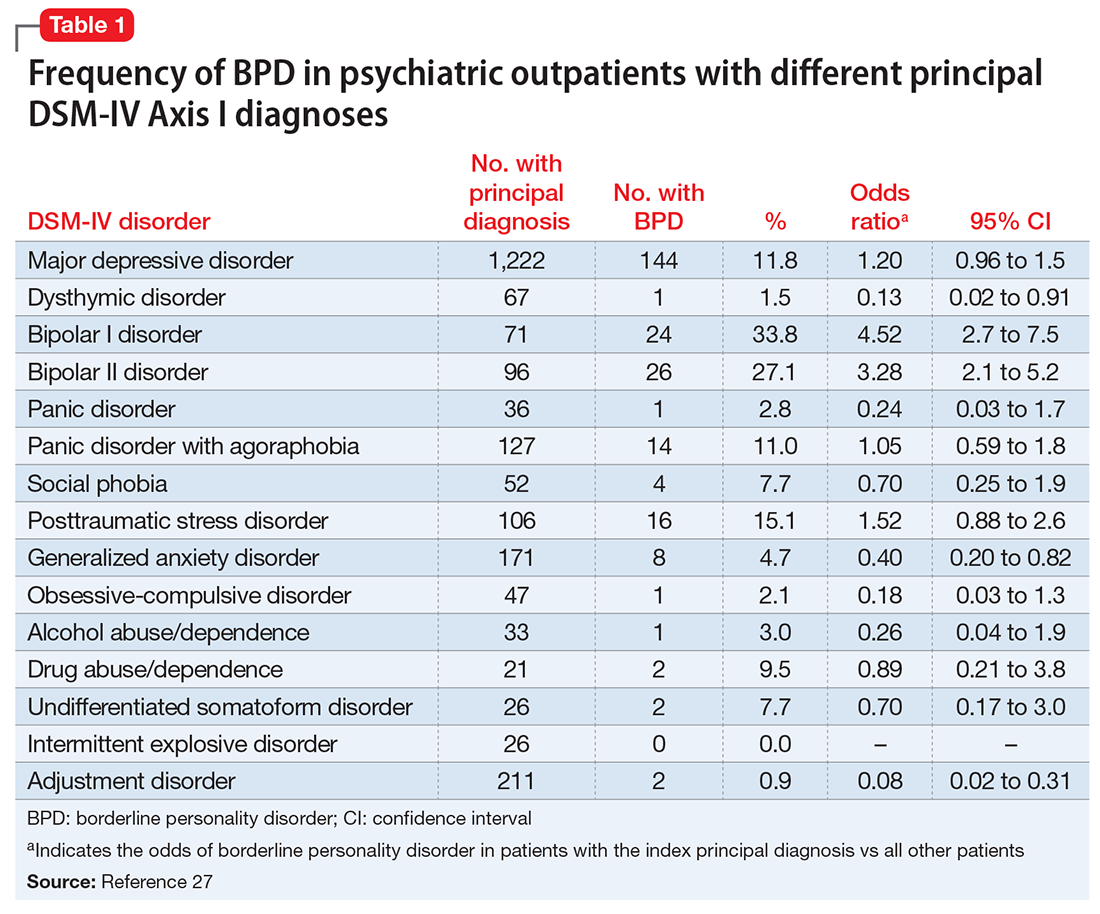

Summary of benefits, place in treatment armamentarium. Individuals with schizophrenia have a shorter life expectancy than that of the general population mostly as a result of suicide and comorbid physical illnesses,3 but the number of patients with schizophrenia age >55 will double over the next 2 decades.4 With aging, both positive and negative symptoms may be a focus of treatment (Table 1).5,6 Antipsychotics are a first-line treatment for older patients with schizophrenia with few medication alternatives.7 Safety risks associated with antipsychotics in older people span a broad spectrum (Table 2).8

A 6-week prospective RCT evaluated paliperidone extended-release vs placebo in 114 older adults (age ≥65 years; mean age, 70 years) with schizophrenia.14 There was an optional 24-week extension of open-label treatment with paliperidone. Mean daily dose of paliperidone was 8.4 mg. Efficacy measures did not show consistent statistically significant differences between treatment groups. Discontinuation rates were similar between paliperidone (7%) vs placebo (8%). Serious adverse events occurred in 3% of paliperidone-treated vs 8% of placebo-treated patients. Elevated prolactin levels occurred in one-half of paliperidone-treated patients. There were no prolactin or glucose treatment-related adverse events or significant mean changes in body weight for either paliperidone-treated or placebo-treated patients. Safety findings in the 24-week, open-label extension group were consistent with the RCT results.

Howanitz et al15 conducted a 12-week, prospective RCT that compared clozapine (mean dose, 300 mg/d) with chlorpromazine (mean dose, 600 mg/d) in 42 older adults (mean age, 67 years) with schizophrenia. Drop-out rate prior to 5 weeks was 19% and similar between groups. Common adverse effects included sialorrhea, hematologic abnormalities, sedation, tachycardia, EPS, and weight gain. Although both drugs were effective, more patients taking clozapine had tachycardia and weight gain, while more chlorpromazine patients reported sedation.

There have been other, less rigorous studies.7,8 Most of these studies evaluated risperidone and olanzapine, and most were conducted in “younger” geriatric patients (age <75 years). Although patients who participate in clinical trials may be healthier than “typical” patients, adverse effects such as EPS, sedation, and weight gain were still relatively common in these studies.

Other clinical data. A major consideration in treating older adults with schizophrenia is balancing the need to administer an antipsychotic dose high enough to alleviate psychotic symptoms while minimizing dose-dependent adverse effects. There is a U-shaped relationship between age and vulnerability to antipsychotic adverse effects,16,17 wherein adverse effects are highest at younger and older ages. Evidence supports using the lowest effective antipsychotic dose for geriatric patients with schizophrenia. Positive emission tomography (PET) studies suggest that older patients develop EPS with lower doses despite lower receptor occupancy.17,18 A recent study of 35 older patients (mean age, 60.1 years) with schizophrenia obtained PET, clinical measures, and blood pharmacokinetic measures before and after reduction of risperidone or olanzapine doses.18 A ≥40% reduction in dose was associated with reduced adverse effects, particularly EPS and elevation of prolactin levels. Moreover, the therapeutic window of striatal D2/D3 receptor occupancy appeared to be 50% to 60% in these older patients, compared with 65% to 80% in younger patients.

Long-term risks of antipsychotic treatment across the lifespan are less clear, with evidence suggesting both lower and higher mortality risk.19,20 It is difficult to fully disentangle the long-term risks of antipsychotics from the cumulative effects of lifestyle and comorbidity among individuals who have lived with schizophrenia for decades. Large naturalistic studies that include substantial numbers of older people with schizophrenia might be a way to elicit more information on long-term safety. The Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcome (SOHO) study was a large naturalistic trial that recruited >10,000 individuals with schizophrenia in 10 European countries.21 Although the SOHO study found differences between antipsychotics and adverse effects, such as EPS, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction, because the mean age of these patients was approximately 40 years and the follow-up period was only 3 years, it is difficult to draw conclusions that could be relevant to older individuals who have had schizophrenia for decades.

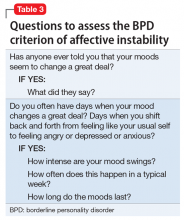

Bipolar Disorder

Clinical trials: Bipolar depression. A post hoc, secondary analysis of two 8-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies in bipolar depression compared 2 dosages of quetiapine (300 mg/d and 600 mg/d) with placebo in mixed-age patients.31 In a subgroup of 72 patients, ages 55 to 65, remission occurred more often with quetiapine than with placebo. Study discontinuation rates were similar between older people and younger people (age <55 years): quetiapine, 300 mg/d, 29.2%; quetiapine, 600 mg/d, 48.1%; and placebo, 29.6% in older adults, compared with 37.1%, 45.8%, and 38.1%, respectively, in younger adults. In all patients, the most common reason for discontinuation was adverse events with quetiapine and lack of efficacy for placebo. Adverse event rates were similar in older and younger adults. Dry mouth and dizziness were more common in older adults. Proportions of adults experiencing clinically significant weight gain (≥7% of body weight) were 5.3%, 8.3%, and 0% in older adults receiving quetiapine, 300 mg/d, quetiapine, 600 mg/d, and placebo, respectively, compared with 7.2%, 10.1%, and 2.6% in younger adults. EPS and treatment-emergent mania were minimal.

A secondary analysis of mixed-age, RCTs examined response in older adults (age ≥55 years) with bipolar I depression who received lurasidone as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.32 In the monotherapy study, these patients were randomized to 6 weeks of lurasidone 20 to 60 mg/d, lurasidone 80 to 120 mg/d, or placebo. In the adjunctive therapy study, they were randomized to lurasidone 20 to 120 mg/d or placebo with either lithium or valproate. There were 83 older adults (17.1% of the sample) in the monotherapy study and 53 (15.6%) in the adjunctive therapy study. Mean improvement in depression was significantly higher for both doses of lurasidone monotherapy than placebo. Adjunctive lurasidone was not associated with statistically significant improvement vs placebo. The most frequent adverse events in older patients on lurasidone monotherapy 20 to 60 mg/d or 80 to 120 mg/d were nausea (18.5% and 9.7%, respectively) and somnolence (11.1% and 0%, respectively). Akathisia (9.7%) and insomnia (9.7%) were the most common adverse events in the group receiving 80 to 120 mg/d, with the rate of akathisia exhibiting a dose-related increase. Weight change with lurasidone was similar to placebo, and there were no clinically meaningful group changes in vital signs, electrocardiography, or laboratory parameters.

A small (N = 20) open study found improvement in older adults with bipolar depression with aripiprazole (mean dose, 10.3 mg/d).33 Adverse effects included restlessness and weight gain (n = 3, 9% each), sedation (n = 2, 10%), and drooling and diarrhea/loose stools (n = 1, 5% each). In another small study (N = 15) using asenapine (mean dose, 11.2 mg/d) in mainly older bipolar patients with depression, the most common adverse effects were gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort (n = 5, 33%) and restlessness, tremors, cognitive difficulties, and sluggishness (n = 2, 13% each).34

Clinical trials: Bipolar mania. Researchers conducted a pooled analysis of two 12-week randomized trials comparing quetiapine with placebo in a mixed-age sample with bipolar mania.35 In a subgroup of 59 older patients (mean age, 62.9 years), manic symptoms improved significantly more with quetiapine (modal dose, 550 mg/d) than with placebo. Adverse effects reported by >10% of older patients were dry mouth, somnolence, postural hypotension, insomnia, weight gain, and dizziness. Insomnia was reported by >10% of patients receiving placebo.

In a case series of 11 elderly patients with mania receiving asenapine, Baruch et al36 reported a 63% remission rate. One patient discontinued the study because of a new rash, 1 discontinued after developing peripheral edema, and 3 patients reported mild sedation.

Beyer et al37 reported on a post hoc analysis of 94 older adults (mean age, 57.1 years; range, 50.1 to 74.8 years) with acute bipolar mania receiving olanzapine (n = 47), divalproex (n = 31), or placebo (n = 16) in a pooled olanzapine clinical trials database. Patients receiving olanzapine or divalproex had improvement in mania; those receiving placebo did not improve. Safety findings were comparable with reports in younger patients with mania.