User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Using antipsychotics for dementia

Sexting: What are the clinical and legal implications?

Sexting includes sending sexually explicit (or sexually suggestive) text messages and photos, usually by cell phone. This article focuses on sexts involving photos. Cell phones are almost ubiquitous among American teens, and with technological advances, sexts are getting easier to send. Sexting may occur to initiate a relationship or sustain one. Some teenagers are coerced into sexting. Many people do not realize the potential long-term consequences of sexting—particularly because of the impulsive nature of sexting and the belief that the behavior is harmless.

Media attention has recently focused on teens who face legal charges related to sexting. Sexting photos may be considered child pornography—even though the teens made it themselves. There are also social consequences to sexting. Photos meant to be private are sometimes forwarded to others. Cyberbullying is not uncommon with teen sexting, and suicides after experiencing this behavior have been reported.

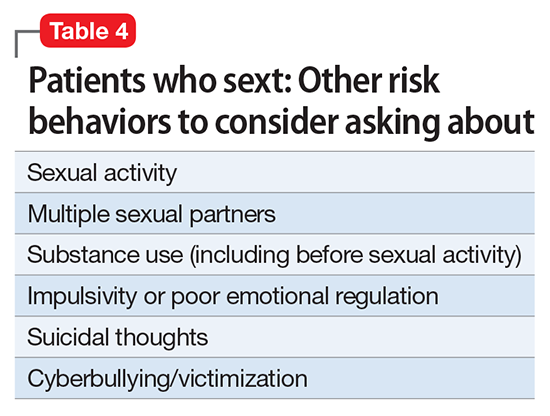

Sexting may be a form of modern flirtation, but in some cases, it may be a marker of other risk behaviors, such as substance abuse. Psychiatrists must be aware of the frequency and meaning of this potentially dangerous behavior. Clinicians should feel comfortable asking their patients about it and provide education and counseling.

CASE

Private photos get shared

K, age 14, a freshman with no psychiatric history, is referred to you by her school psychologist for evaluation of suicidal ideation. K reports depressed mood, poor sleep, inattention, loss of appetite, anhedonia, and feelings of guilt for the past month. She recently ended a relationship with her boyfriend of 1 year after she learned that he had shared with his friends naked photos of her that she had sent him. The school administration learned of the photos when a student posted them on one of the school computers.

K’s boyfriend, age 16, was suspended after the school learned that he had shared the photos without K’s consent. K, who is a good student, missed several days of school, including cheerleading practice; previously she had never missed a day of school.

On evaluation, K is tearful, stating that her life is “over.” She says that her ex-boyfriend’s friends are harassing her, calling her “slut” and making sexual comments. She also feels guilty, because she learned that the police interviewed her ex-boyfriend in connection with posting her photos on the Internet. In a text, he said he “might get charged with child pornography.” On further questioning, K confides that she had naked photos of her ex-boyfriend on her phone. She admits to sharing the pictures with her best friend, because she was “angry and wanted to get back” at her ex-boyfriend. She also reports a several-month history of sexting with her ex-boyfriend. K deleted the photos and texts after learning that her ex-boyfriend “was in trouble with the police.”

K has no prior sexual experience. She dated 1 boy her age prior to her ex-boyfriend. She had never been evaluated by a mental health clinician. She is dysphoric and reports feeling “hopeless … Unless this can be erased, I can’t go back to school.”

Sexting: What is the extent of the problem?

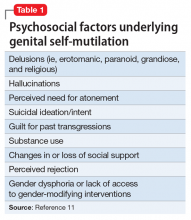

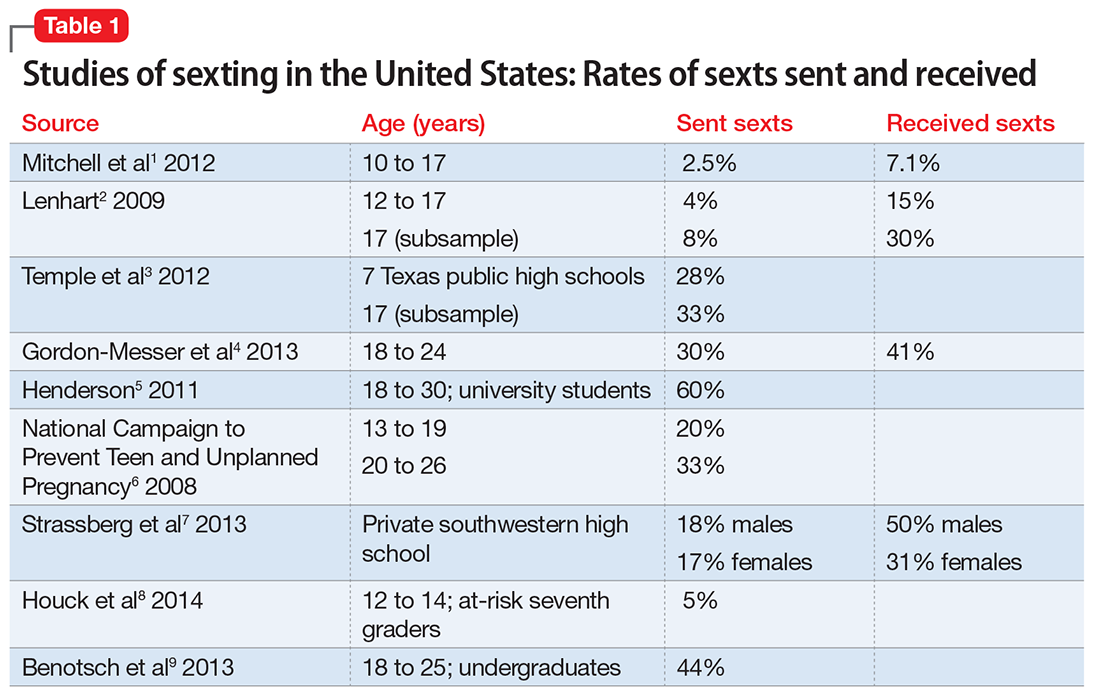

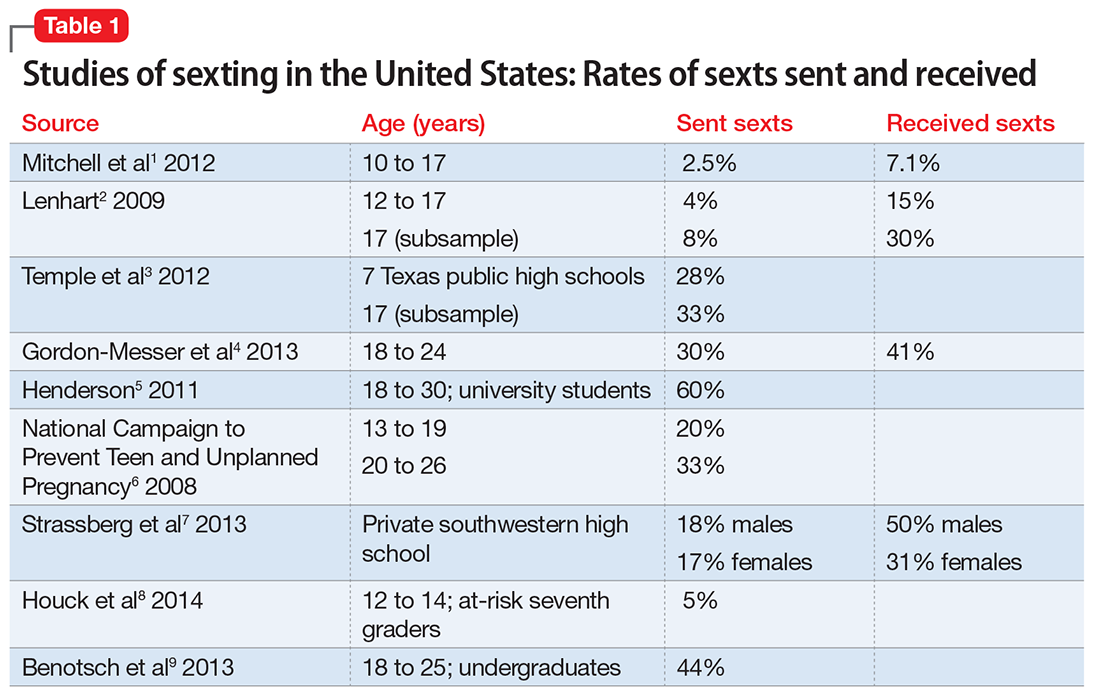

The true prevalence of sexting is difficult to ascertain, because different studies have used different definitions and methodologies. However, the rates are far from negligible. Sexting rates increase with age, over the teen years.1-3 Among American minors, 2.5% to 28% of middle school and high school students report that they have sent a sext (Table 11-9). Studies of American young adults (age ≥18) and university students have found 30% to 60% have sent sexts, and >40% have received a sext.4,5

Many people receive sexts—including individuals who are not the intended recipient. In 1 study, although most teens intended to share sexts only with their boyfriend/girlfriend, 25% to 33% had received sext photos intended for other people.6 In another recent study, 25% of teens had forwarded a sext that they received.7 Moreover, 12% of teenage boys and 5% of teenage girls had sent a sexually explicit photo that they took of another teen to a third person.7 Forwarding sexts can add exponentially to the psychosocial risks of the photographed teenager.

Who sexts? Current research indicates that the likelihood of sexting is related to age, personality, and social situation. Teens are approaching the peak age of their sex drive, and often are curious and feel invincible. Teens are more impulsive than adults. When it takes less than a minute to send a sext, irreversible poor choices can be made quickly. Teens who send sexts often engage in more text messaging than other teens.7

Teens may use sexting to initiate or sustain a relationship. Sexts also may be sent because of coercion. More than one-half of girls cited pressure to sext from a boy.6 Temple et al3 found that more than one-half of their study sample had been asked to send a sext. Girls were more likely than boys to be asked to send a sext; most were troubled by this.

One study that assessed knowledge of potential legal consequences of sexting found that many teens who sent sexts were aware of the potential consequences.7 Regarding personality traits, sexting among undergraduates was predicted by neuroticism and low agreeableness.10 Conversely, sending text messages with sexually suggestive writing was predicted by extraversion and problematic cell phone use.

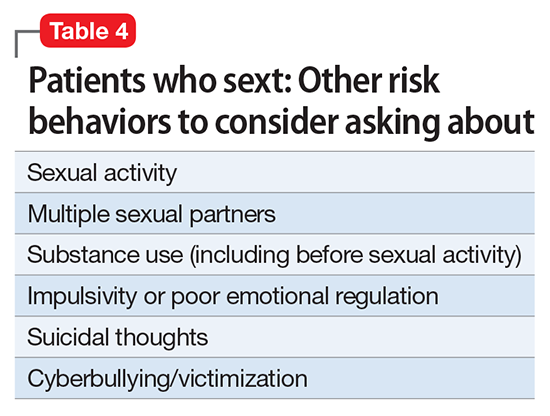

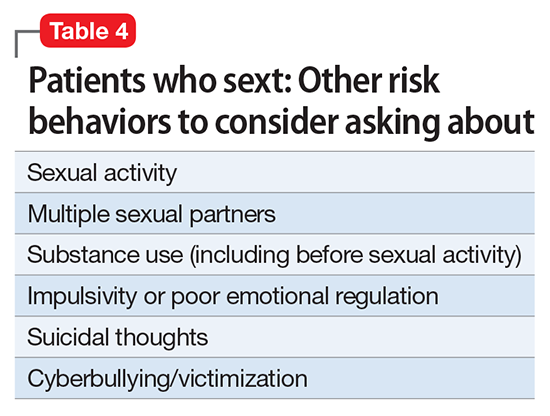

Comorbidities. There are mixed findings about whether sexting is simply a modern dating strategy or a marker of other risk behaviors; age may play an important discriminating role. Sexual activity appears to be correlated with sexting. According to Temple and Choi,11 “Sexting fits within the context of adolescent sexual development and may be a viable indicator of adolescent sexual activity.”11

Some authors have suggested that sexting is a contemporary risk behavior that is likely to correlate with other risk behaviors. Among young teens—seventh graders who were referred to a risk prevention trial because of behavioral/emotional difficulties—those who sexted were more likely to engage in early sexual behaviors.8 These younger at-risk teens also had less understanding of their emotions and greater difficulty in regulating their emotions.

Among the general population of high school students, teens who sext are more likely to be sexually active.3 High school girls who engaged in sexting were noted to engage in other risk behaviors, including having multiple partners in the past year and using alcohol or drugs before sex.3 Teens who had sent a sext were more likely to be sexually active 1 year later than teens who had not.11Studies of sexting among university students also have had mixed findings. One study found that among undergraduates, sexting was associated with substance use and other risk behaviors.9 Another young adult study found sexting was not related to sexual risk or psychological well-being.4

Legal issues affect psychiatrists as well as patients

As a psychiatrist evaluating K, what are your duties as a mandated reporter? Psychiatrists are legally required to report suspected maltreatment or abuse of children.12 The circumstances under which psychiatrists may have a mandate to report include when a psychiatrist:

- evaluates a child and suspects abuse

- suspects child abuse based on an adult patient’s report

- learns from a third party that a child may have been/is being abused.

Psychiatrists usually are not mandated to report other types of potentially criminal behavior. As such, reporting sexting might be considered a breach of confidentiality. Psychiatrists should be familiar with the specific reporting guidelines for the jurisdiction in which they practice. Psychiatrists who work with individuals who commit crimes should focus on changing the potentially dangerous behaviors rather than reporting them.

Does the transmission of naked photos of a minor in a sexual pose or act constitute child pornography or another criminal offense? The legal answer varies, but the role of the psychiatrist does not. Psychiatrists should educate their patients about potentially dangerous behaviors.

With regards to the legal consequences, some states classify underage sexting photos as child pornography. Others have less rigid definitions of child pornography and take into account the age of the participants and their intent. Such jurisdictions point out that sexting naked photos among adolescents is “age appropriate.” Some have enacted specific sexting laws to address the transmission of obscene material to a child through the Internet. In some jurisdictions, sexting laws are categorized to refer to behavior of individuals under or over age 18. The term “revenge porn” is used to refer to nonconsensual pornography with its dissemination motivated by spite.13 Some states have defined specific revenge porn laws to address the behavior. Currently, 20 states have sexting laws and 26 states have revenge porn laws.14 Twenty states address a minor age <18 sending the photo, while only 18 address the recipient. The law in this area can be complex and detailed, taking into account the age of the sender, the intentions of the sender, and the nature of the relationship between the sender and the recipient and the behavior of the recipient.

Laws regarding sexting vary greatly. Sexting may be a misdemeanor or a felony, depending on the state, the specific behavior, and the frequency. In the United States, 11 state laws include a diversion remedy—an option to pursue the case outside of the criminal juvenile system; 10 laws require counseling or another informal sanction; 11 states laws have the potential for misdemeanor punishment; and 4 state laws have the potential for felony punishment.14 Depending on the criminal charge, the perpetrator may have to register as a sex offender. For example, in some jurisdictions, a conviction for possession of child pornography requires sex offender registration. Thirty-eight states include juvenile sex offenders in their sex offender registries. Other states require juveniles to register if they are age ≥15 years or have been tried as an adult.15

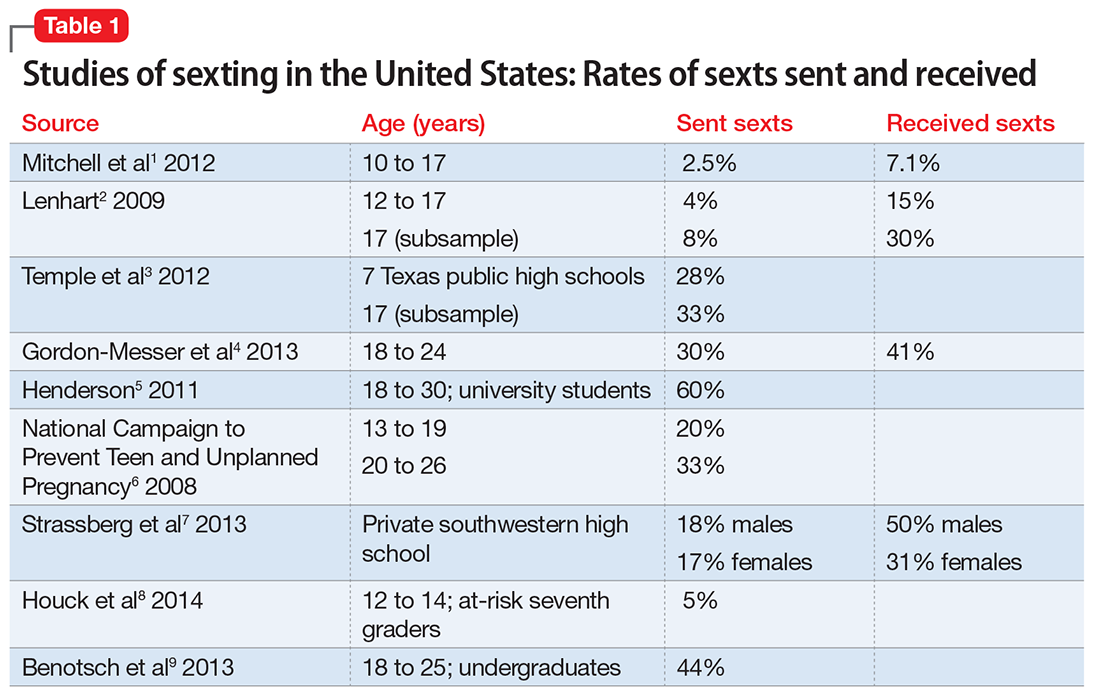

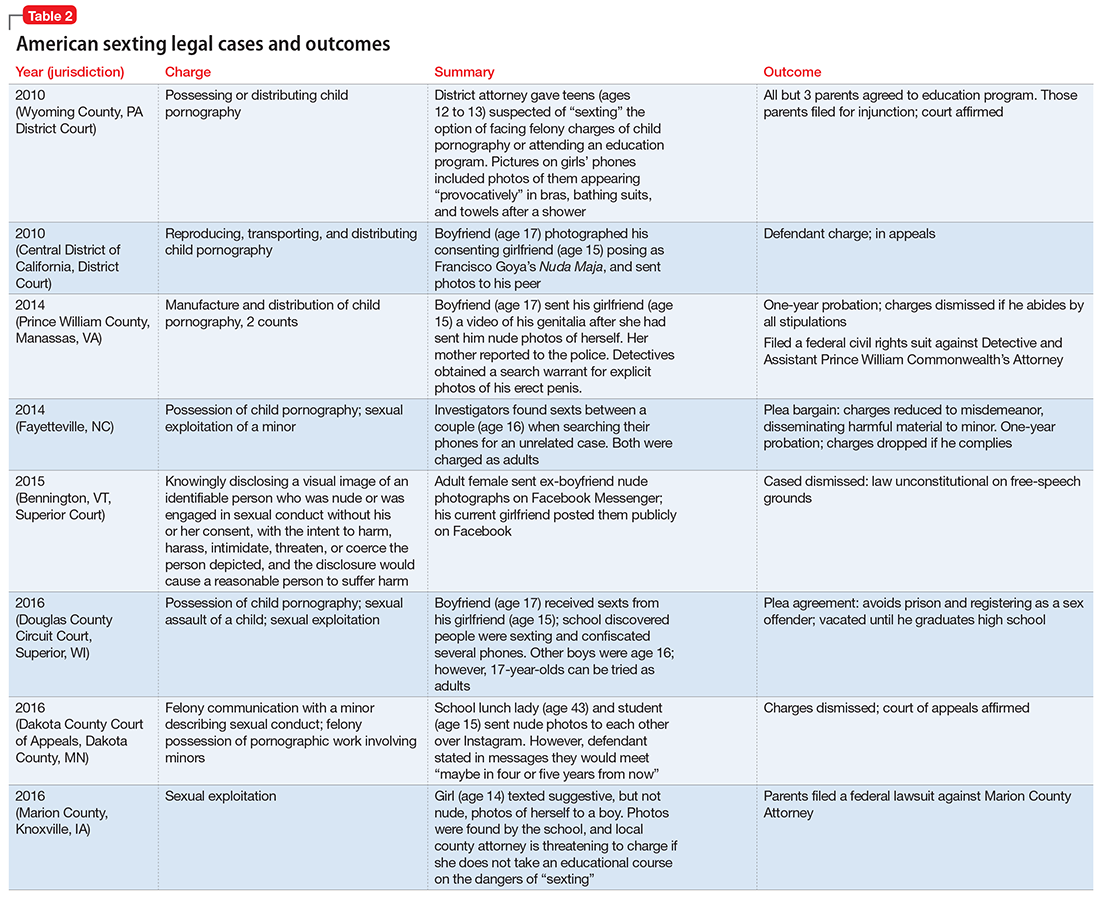

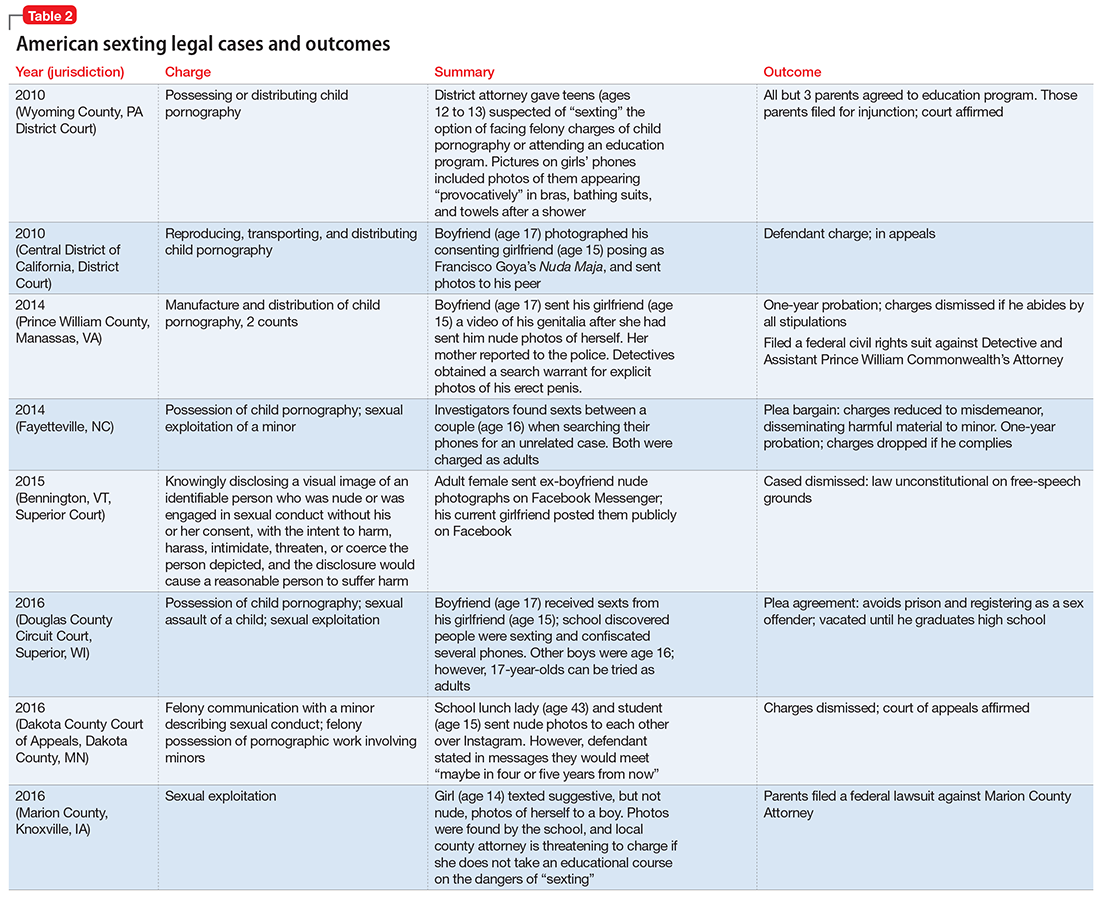

The frequency of police involvement in sexting cases also greatly varies. A national study examining the characteristics of youth sexting cases revealed that law enforcement agencies handled approximately 3,477 cases of youth-produced sexual photos in 2008 and 2009.16 Situations that involved an adult or a minor engaged in malicious, nonconsensual, or abusive behavior comprised two-thirds of cases. Arrests occurred in 62% of the adult-involved cases and 36% of the aggravated youth-only cases. Arrests occurred in only 18% of investigated non-aggravated youth-only cases. Table 2 describes recent American sexting legal cases and their outcomes.

In K’s case, depending on the jurisdiction, K or her ex-boyfriend may be subject to arrest for child pornography, revenge pornography, or sexting.

Potential social and psychiatric consequences

What are the social and psychiatric ramifications for K? Aside from potential legal consequences of sexting, K is experiencing psychological and social consequences. She has developed depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Her ex-boyfriend’s dissemination of her nude photos on the school computer could be interpreted as cyberbullying. (The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children defines cyberbullying as “bullying through the use of technology or electronic devices such as telephones, cell phones, computers, and the Internet.”17 All 50 states have enacted laws against bullying; 48 states have electronic harassment in their bullying laws; and 22 states have laws specifically referencing “cyberbullying.”)

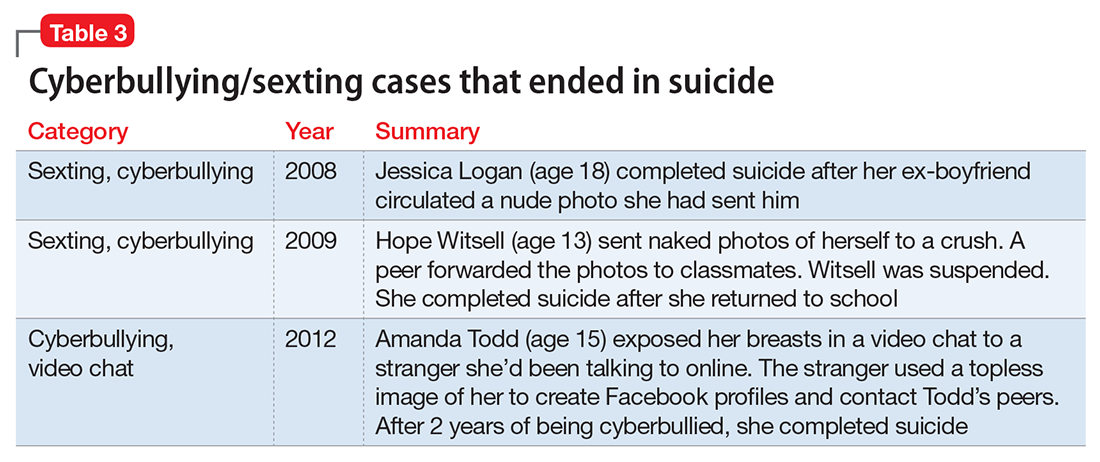

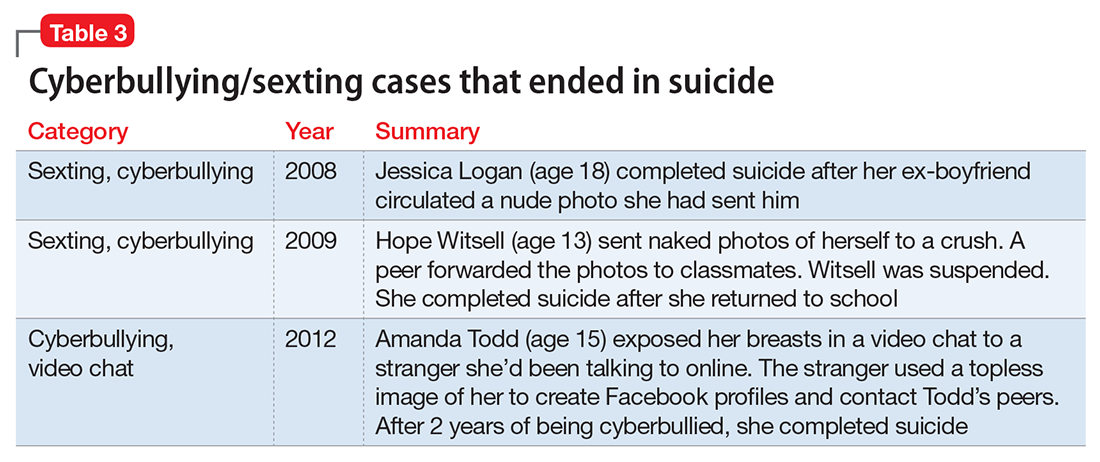

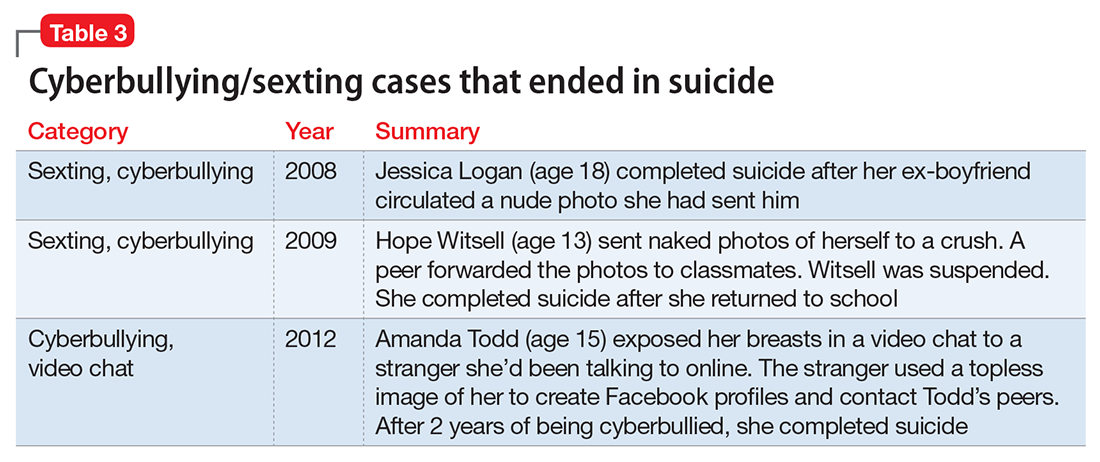

Her depressive symptoms developed in response to her feelings of guilt and shame related to sexting as well as the subsequent peer harassment. She is refusing to return to school because of her concerns about bullying. A careful inquiry into suicidality should be part of the evaluation when sexting has led to psychiatric symptoms. Several cases of sexting and cyberbullying have ended in suicide (Table 3).

How to ask patients about sexting

To screen patients for sexting, clinicians need to develop a new skill set, which at first may be uncomfortable. However, the questions to ask are not all that different from other questions about adolescent and young adult sexuality. The importance of patients seeing that we as physicians are comfortable with the topic and approachable about their sexual health cannot be overemphasized. When discussing sexting with patients, it is essential to:

- explain that you are asking questions about their sexual health because they are important to overall health

- engage patients in discussion in a nonthreatening and nonjudgmental way

- develop rapport so patients feel comfortable disclosing behavior that may be embarrassing

- listen to their stories and build a context for understanding their experiences. As you listen, ask questions when needed to help move the story along.

Sometimes when asking about topics that are uncomfortable, clinicians revert from open-ended to closed-ended questions, but when asking about a patient’s sexual life, it is especially important to be open-ended and ask questions in a nonjudgmental way. Contextualizing sexual questions by (for example) asking them while discussing the teen’s relationships will make them seem more natural.18 To best understand, inquire explicitly about specific behaviors, but do so without appearing voyeuristic.18

Sexting may precede sexual intercourse. Keep in mind that a patient may report that she (he) is not sexually active but still may be involved in sexting. Therefore, discuss sexting even if your patient reports not being sexually active. By understanding the prevalence of sexting among teens, you can ask questions in a normalizing way. Clinicians can inquire about sexting while discussing relationships and dating or online risk behaviors.

Also consider whether any of your patient’s sexual behaviors, including sexting, are the result of coercion: “Some of my patients tell me they feel pressured or coerced into having sex. Have you ever felt this way?”19 and “Have you ever been picked on or bullied? Is that still a problem?” are suggested safety screening questions about bullying,18 and one can also ask about specific cyberbullying behaviors.

1. Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Jones LM, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of youth sexting: a national study. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):13-20.

2. Lenhart A. Teens and sexting. The Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2009/12/15/teens-and-sexting. Published December 15, 2009. Accessed October 31, 2017.

3. Temple JR, Paul JA, van den Berg P, et al. Teen sexting and its association with sexual behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(9):828-833.

4. Gordon-Messer D, Bauermeister JA, Grodzinski A, et al. Sexting among young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):301-306.

5. Henderson L. Sexting and sexual relationships among teens and young adults. McNair Scholars Research Journal. 2011;7(1):31-39.

6. The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Sex and tech: results from a survey of teens and young adults. https://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/sex_and_tech_summary.pdf. Published December 2008. Accessed October 31, 2017.

7. Strassberg DS, McKinnon RK, Sustaíta MA, et al. Sexting by high school students: an exploratory and descriptive study. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(1):15-21.

8. Houck CD, Barker D, Rizzo C, et al. Sexting and sexual behavior in at-risk adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):e276-e282.

9. Benotsch EG, Snipes DJ, Martin AM, et al. Sexting, substance use, and sexual risk behavior in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):307-313.

10. Delevi R, Weisskirch RS. Personality factors as predictors of sexting. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(6):2589-2594.

11. Temple JR, Choi H. Longitudinal association between teen sexting and sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):1287-1292.

12. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psych Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

13. Citron DK, Franks MA. Criminalizing revenge porn. Wake Forest Law Review. 2014;49:345-391.

14. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. State cyberbullying laws: a brief review of state cyberbullying laws and policies. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/Bullying-and-Cyberbullying-Laws.pdf. Updated 2016. Accessed October 31, 2017.

15. Beitsch R. States slowly scale back juvenile sex offender registries. The Pew Charitable Trusts. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2015/11/19/states-slowly-scale-back-juvenile-sex-offender-registries. Published November 19, 2015. Accessed October 31, 2017.

16. Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ. How often are teens arrested for sexting? Data from a national sample of police cases. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):4-12.

17. The Campus School at Boston College. Bullying prevention policy. https://www.bc.edu/bc-web/schools/lsoe/sites/campus-school/who-we-are/policies-and-procedures/bullying-prevention-policy.html. Accessed October 31, 2017.

18. Goldenring JM, Rosen DS. Getting into adolescent heads: an essential update. Contemporary Pediatrics. 2004;21(1):64.

19. Klein DA, Goldenring JM, Adelman WP. HEEADSSS 3.0: the psychosocial interview for adolescents updated for a new century fueled by media. Contemporary Pediatrics. http://contemporarypediatrics.modernmedicine.com/contemporary-pediatrics/content/tags/adolescent-medicine/heeadsss-30-psychosocial-interview-adolesce?page=full. Published January 1, 2014. Accessed October 31, 2017.

Sexting includes sending sexually explicit (or sexually suggestive) text messages and photos, usually by cell phone. This article focuses on sexts involving photos. Cell phones are almost ubiquitous among American teens, and with technological advances, sexts are getting easier to send. Sexting may occur to initiate a relationship or sustain one. Some teenagers are coerced into sexting. Many people do not realize the potential long-term consequences of sexting—particularly because of the impulsive nature of sexting and the belief that the behavior is harmless.

Media attention has recently focused on teens who face legal charges related to sexting. Sexting photos may be considered child pornography—even though the teens made it themselves. There are also social consequences to sexting. Photos meant to be private are sometimes forwarded to others. Cyberbullying is not uncommon with teen sexting, and suicides after experiencing this behavior have been reported.

Sexting may be a form of modern flirtation, but in some cases, it may be a marker of other risk behaviors, such as substance abuse. Psychiatrists must be aware of the frequency and meaning of this potentially dangerous behavior. Clinicians should feel comfortable asking their patients about it and provide education and counseling.

CASE

Private photos get shared

K, age 14, a freshman with no psychiatric history, is referred to you by her school psychologist for evaluation of suicidal ideation. K reports depressed mood, poor sleep, inattention, loss of appetite, anhedonia, and feelings of guilt for the past month. She recently ended a relationship with her boyfriend of 1 year after she learned that he had shared with his friends naked photos of her that she had sent him. The school administration learned of the photos when a student posted them on one of the school computers.

K’s boyfriend, age 16, was suspended after the school learned that he had shared the photos without K’s consent. K, who is a good student, missed several days of school, including cheerleading practice; previously she had never missed a day of school.

On evaluation, K is tearful, stating that her life is “over.” She says that her ex-boyfriend’s friends are harassing her, calling her “slut” and making sexual comments. She also feels guilty, because she learned that the police interviewed her ex-boyfriend in connection with posting her photos on the Internet. In a text, he said he “might get charged with child pornography.” On further questioning, K confides that she had naked photos of her ex-boyfriend on her phone. She admits to sharing the pictures with her best friend, because she was “angry and wanted to get back” at her ex-boyfriend. She also reports a several-month history of sexting with her ex-boyfriend. K deleted the photos and texts after learning that her ex-boyfriend “was in trouble with the police.”

K has no prior sexual experience. She dated 1 boy her age prior to her ex-boyfriend. She had never been evaluated by a mental health clinician. She is dysphoric and reports feeling “hopeless … Unless this can be erased, I can’t go back to school.”

Sexting: What is the extent of the problem?

The true prevalence of sexting is difficult to ascertain, because different studies have used different definitions and methodologies. However, the rates are far from negligible. Sexting rates increase with age, over the teen years.1-3 Among American minors, 2.5% to 28% of middle school and high school students report that they have sent a sext (Table 11-9). Studies of American young adults (age ≥18) and university students have found 30% to 60% have sent sexts, and >40% have received a sext.4,5

Many people receive sexts—including individuals who are not the intended recipient. In 1 study, although most teens intended to share sexts only with their boyfriend/girlfriend, 25% to 33% had received sext photos intended for other people.6 In another recent study, 25% of teens had forwarded a sext that they received.7 Moreover, 12% of teenage boys and 5% of teenage girls had sent a sexually explicit photo that they took of another teen to a third person.7 Forwarding sexts can add exponentially to the psychosocial risks of the photographed teenager.

Who sexts? Current research indicates that the likelihood of sexting is related to age, personality, and social situation. Teens are approaching the peak age of their sex drive, and often are curious and feel invincible. Teens are more impulsive than adults. When it takes less than a minute to send a sext, irreversible poor choices can be made quickly. Teens who send sexts often engage in more text messaging than other teens.7

Teens may use sexting to initiate or sustain a relationship. Sexts also may be sent because of coercion. More than one-half of girls cited pressure to sext from a boy.6 Temple et al3 found that more than one-half of their study sample had been asked to send a sext. Girls were more likely than boys to be asked to send a sext; most were troubled by this.

One study that assessed knowledge of potential legal consequences of sexting found that many teens who sent sexts were aware of the potential consequences.7 Regarding personality traits, sexting among undergraduates was predicted by neuroticism and low agreeableness.10 Conversely, sending text messages with sexually suggestive writing was predicted by extraversion and problematic cell phone use.

Comorbidities. There are mixed findings about whether sexting is simply a modern dating strategy or a marker of other risk behaviors; age may play an important discriminating role. Sexual activity appears to be correlated with sexting. According to Temple and Choi,11 “Sexting fits within the context of adolescent sexual development and may be a viable indicator of adolescent sexual activity.”11

Some authors have suggested that sexting is a contemporary risk behavior that is likely to correlate with other risk behaviors. Among young teens—seventh graders who were referred to a risk prevention trial because of behavioral/emotional difficulties—those who sexted were more likely to engage in early sexual behaviors.8 These younger at-risk teens also had less understanding of their emotions and greater difficulty in regulating their emotions.

Among the general population of high school students, teens who sext are more likely to be sexually active.3 High school girls who engaged in sexting were noted to engage in other risk behaviors, including having multiple partners in the past year and using alcohol or drugs before sex.3 Teens who had sent a sext were more likely to be sexually active 1 year later than teens who had not.11Studies of sexting among university students also have had mixed findings. One study found that among undergraduates, sexting was associated with substance use and other risk behaviors.9 Another young adult study found sexting was not related to sexual risk or psychological well-being.4

Legal issues affect psychiatrists as well as patients

As a psychiatrist evaluating K, what are your duties as a mandated reporter? Psychiatrists are legally required to report suspected maltreatment or abuse of children.12 The circumstances under which psychiatrists may have a mandate to report include when a psychiatrist:

- evaluates a child and suspects abuse

- suspects child abuse based on an adult patient’s report

- learns from a third party that a child may have been/is being abused.

Psychiatrists usually are not mandated to report other types of potentially criminal behavior. As such, reporting sexting might be considered a breach of confidentiality. Psychiatrists should be familiar with the specific reporting guidelines for the jurisdiction in which they practice. Psychiatrists who work with individuals who commit crimes should focus on changing the potentially dangerous behaviors rather than reporting them.

Does the transmission of naked photos of a minor in a sexual pose or act constitute child pornography or another criminal offense? The legal answer varies, but the role of the psychiatrist does not. Psychiatrists should educate their patients about potentially dangerous behaviors.

With regards to the legal consequences, some states classify underage sexting photos as child pornography. Others have less rigid definitions of child pornography and take into account the age of the participants and their intent. Such jurisdictions point out that sexting naked photos among adolescents is “age appropriate.” Some have enacted specific sexting laws to address the transmission of obscene material to a child through the Internet. In some jurisdictions, sexting laws are categorized to refer to behavior of individuals under or over age 18. The term “revenge porn” is used to refer to nonconsensual pornography with its dissemination motivated by spite.13 Some states have defined specific revenge porn laws to address the behavior. Currently, 20 states have sexting laws and 26 states have revenge porn laws.14 Twenty states address a minor age <18 sending the photo, while only 18 address the recipient. The law in this area can be complex and detailed, taking into account the age of the sender, the intentions of the sender, and the nature of the relationship between the sender and the recipient and the behavior of the recipient.

Laws regarding sexting vary greatly. Sexting may be a misdemeanor or a felony, depending on the state, the specific behavior, and the frequency. In the United States, 11 state laws include a diversion remedy—an option to pursue the case outside of the criminal juvenile system; 10 laws require counseling or another informal sanction; 11 states laws have the potential for misdemeanor punishment; and 4 state laws have the potential for felony punishment.14 Depending on the criminal charge, the perpetrator may have to register as a sex offender. For example, in some jurisdictions, a conviction for possession of child pornography requires sex offender registration. Thirty-eight states include juvenile sex offenders in their sex offender registries. Other states require juveniles to register if they are age ≥15 years or have been tried as an adult.15

The frequency of police involvement in sexting cases also greatly varies. A national study examining the characteristics of youth sexting cases revealed that law enforcement agencies handled approximately 3,477 cases of youth-produced sexual photos in 2008 and 2009.16 Situations that involved an adult or a minor engaged in malicious, nonconsensual, or abusive behavior comprised two-thirds of cases. Arrests occurred in 62% of the adult-involved cases and 36% of the aggravated youth-only cases. Arrests occurred in only 18% of investigated non-aggravated youth-only cases. Table 2 describes recent American sexting legal cases and their outcomes.

In K’s case, depending on the jurisdiction, K or her ex-boyfriend may be subject to arrest for child pornography, revenge pornography, or sexting.

Potential social and psychiatric consequences

What are the social and psychiatric ramifications for K? Aside from potential legal consequences of sexting, K is experiencing psychological and social consequences. She has developed depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Her ex-boyfriend’s dissemination of her nude photos on the school computer could be interpreted as cyberbullying. (The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children defines cyberbullying as “bullying through the use of technology or electronic devices such as telephones, cell phones, computers, and the Internet.”17 All 50 states have enacted laws against bullying; 48 states have electronic harassment in their bullying laws; and 22 states have laws specifically referencing “cyberbullying.”)

Her depressive symptoms developed in response to her feelings of guilt and shame related to sexting as well as the subsequent peer harassment. She is refusing to return to school because of her concerns about bullying. A careful inquiry into suicidality should be part of the evaluation when sexting has led to psychiatric symptoms. Several cases of sexting and cyberbullying have ended in suicide (Table 3).

How to ask patients about sexting

To screen patients for sexting, clinicians need to develop a new skill set, which at first may be uncomfortable. However, the questions to ask are not all that different from other questions about adolescent and young adult sexuality. The importance of patients seeing that we as physicians are comfortable with the topic and approachable about their sexual health cannot be overemphasized. When discussing sexting with patients, it is essential to:

- explain that you are asking questions about their sexual health because they are important to overall health

- engage patients in discussion in a nonthreatening and nonjudgmental way

- develop rapport so patients feel comfortable disclosing behavior that may be embarrassing

- listen to their stories and build a context for understanding their experiences. As you listen, ask questions when needed to help move the story along.

Sometimes when asking about topics that are uncomfortable, clinicians revert from open-ended to closed-ended questions, but when asking about a patient’s sexual life, it is especially important to be open-ended and ask questions in a nonjudgmental way. Contextualizing sexual questions by (for example) asking them while discussing the teen’s relationships will make them seem more natural.18 To best understand, inquire explicitly about specific behaviors, but do so without appearing voyeuristic.18

Sexting may precede sexual intercourse. Keep in mind that a patient may report that she (he) is not sexually active but still may be involved in sexting. Therefore, discuss sexting even if your patient reports not being sexually active. By understanding the prevalence of sexting among teens, you can ask questions in a normalizing way. Clinicians can inquire about sexting while discussing relationships and dating or online risk behaviors.

Also consider whether any of your patient’s sexual behaviors, including sexting, are the result of coercion: “Some of my patients tell me they feel pressured or coerced into having sex. Have you ever felt this way?”19 and “Have you ever been picked on or bullied? Is that still a problem?” are suggested safety screening questions about bullying,18 and one can also ask about specific cyberbullying behaviors.

Sexting includes sending sexually explicit (or sexually suggestive) text messages and photos, usually by cell phone. This article focuses on sexts involving photos. Cell phones are almost ubiquitous among American teens, and with technological advances, sexts are getting easier to send. Sexting may occur to initiate a relationship or sustain one. Some teenagers are coerced into sexting. Many people do not realize the potential long-term consequences of sexting—particularly because of the impulsive nature of sexting and the belief that the behavior is harmless.

Media attention has recently focused on teens who face legal charges related to sexting. Sexting photos may be considered child pornography—even though the teens made it themselves. There are also social consequences to sexting. Photos meant to be private are sometimes forwarded to others. Cyberbullying is not uncommon with teen sexting, and suicides after experiencing this behavior have been reported.

Sexting may be a form of modern flirtation, but in some cases, it may be a marker of other risk behaviors, such as substance abuse. Psychiatrists must be aware of the frequency and meaning of this potentially dangerous behavior. Clinicians should feel comfortable asking their patients about it and provide education and counseling.

CASE

Private photos get shared

K, age 14, a freshman with no psychiatric history, is referred to you by her school psychologist for evaluation of suicidal ideation. K reports depressed mood, poor sleep, inattention, loss of appetite, anhedonia, and feelings of guilt for the past month. She recently ended a relationship with her boyfriend of 1 year after she learned that he had shared with his friends naked photos of her that she had sent him. The school administration learned of the photos when a student posted them on one of the school computers.

K’s boyfriend, age 16, was suspended after the school learned that he had shared the photos without K’s consent. K, who is a good student, missed several days of school, including cheerleading practice; previously she had never missed a day of school.

On evaluation, K is tearful, stating that her life is “over.” She says that her ex-boyfriend’s friends are harassing her, calling her “slut” and making sexual comments. She also feels guilty, because she learned that the police interviewed her ex-boyfriend in connection with posting her photos on the Internet. In a text, he said he “might get charged with child pornography.” On further questioning, K confides that she had naked photos of her ex-boyfriend on her phone. She admits to sharing the pictures with her best friend, because she was “angry and wanted to get back” at her ex-boyfriend. She also reports a several-month history of sexting with her ex-boyfriend. K deleted the photos and texts after learning that her ex-boyfriend “was in trouble with the police.”

K has no prior sexual experience. She dated 1 boy her age prior to her ex-boyfriend. She had never been evaluated by a mental health clinician. She is dysphoric and reports feeling “hopeless … Unless this can be erased, I can’t go back to school.”

Sexting: What is the extent of the problem?

The true prevalence of sexting is difficult to ascertain, because different studies have used different definitions and methodologies. However, the rates are far from negligible. Sexting rates increase with age, over the teen years.1-3 Among American minors, 2.5% to 28% of middle school and high school students report that they have sent a sext (Table 11-9). Studies of American young adults (age ≥18) and university students have found 30% to 60% have sent sexts, and >40% have received a sext.4,5

Many people receive sexts—including individuals who are not the intended recipient. In 1 study, although most teens intended to share sexts only with their boyfriend/girlfriend, 25% to 33% had received sext photos intended for other people.6 In another recent study, 25% of teens had forwarded a sext that they received.7 Moreover, 12% of teenage boys and 5% of teenage girls had sent a sexually explicit photo that they took of another teen to a third person.7 Forwarding sexts can add exponentially to the psychosocial risks of the photographed teenager.

Who sexts? Current research indicates that the likelihood of sexting is related to age, personality, and social situation. Teens are approaching the peak age of their sex drive, and often are curious and feel invincible. Teens are more impulsive than adults. When it takes less than a minute to send a sext, irreversible poor choices can be made quickly. Teens who send sexts often engage in more text messaging than other teens.7

Teens may use sexting to initiate or sustain a relationship. Sexts also may be sent because of coercion. More than one-half of girls cited pressure to sext from a boy.6 Temple et al3 found that more than one-half of their study sample had been asked to send a sext. Girls were more likely than boys to be asked to send a sext; most were troubled by this.

One study that assessed knowledge of potential legal consequences of sexting found that many teens who sent sexts were aware of the potential consequences.7 Regarding personality traits, sexting among undergraduates was predicted by neuroticism and low agreeableness.10 Conversely, sending text messages with sexually suggestive writing was predicted by extraversion and problematic cell phone use.

Comorbidities. There are mixed findings about whether sexting is simply a modern dating strategy or a marker of other risk behaviors; age may play an important discriminating role. Sexual activity appears to be correlated with sexting. According to Temple and Choi,11 “Sexting fits within the context of adolescent sexual development and may be a viable indicator of adolescent sexual activity.”11

Some authors have suggested that sexting is a contemporary risk behavior that is likely to correlate with other risk behaviors. Among young teens—seventh graders who were referred to a risk prevention trial because of behavioral/emotional difficulties—those who sexted were more likely to engage in early sexual behaviors.8 These younger at-risk teens also had less understanding of their emotions and greater difficulty in regulating their emotions.

Among the general population of high school students, teens who sext are more likely to be sexually active.3 High school girls who engaged in sexting were noted to engage in other risk behaviors, including having multiple partners in the past year and using alcohol or drugs before sex.3 Teens who had sent a sext were more likely to be sexually active 1 year later than teens who had not.11Studies of sexting among university students also have had mixed findings. One study found that among undergraduates, sexting was associated with substance use and other risk behaviors.9 Another young adult study found sexting was not related to sexual risk or psychological well-being.4

Legal issues affect psychiatrists as well as patients

As a psychiatrist evaluating K, what are your duties as a mandated reporter? Psychiatrists are legally required to report suspected maltreatment or abuse of children.12 The circumstances under which psychiatrists may have a mandate to report include when a psychiatrist:

- evaluates a child and suspects abuse

- suspects child abuse based on an adult patient’s report

- learns from a third party that a child may have been/is being abused.

Psychiatrists usually are not mandated to report other types of potentially criminal behavior. As such, reporting sexting might be considered a breach of confidentiality. Psychiatrists should be familiar with the specific reporting guidelines for the jurisdiction in which they practice. Psychiatrists who work with individuals who commit crimes should focus on changing the potentially dangerous behaviors rather than reporting them.

Does the transmission of naked photos of a minor in a sexual pose or act constitute child pornography or another criminal offense? The legal answer varies, but the role of the psychiatrist does not. Psychiatrists should educate their patients about potentially dangerous behaviors.

With regards to the legal consequences, some states classify underage sexting photos as child pornography. Others have less rigid definitions of child pornography and take into account the age of the participants and their intent. Such jurisdictions point out that sexting naked photos among adolescents is “age appropriate.” Some have enacted specific sexting laws to address the transmission of obscene material to a child through the Internet. In some jurisdictions, sexting laws are categorized to refer to behavior of individuals under or over age 18. The term “revenge porn” is used to refer to nonconsensual pornography with its dissemination motivated by spite.13 Some states have defined specific revenge porn laws to address the behavior. Currently, 20 states have sexting laws and 26 states have revenge porn laws.14 Twenty states address a minor age <18 sending the photo, while only 18 address the recipient. The law in this area can be complex and detailed, taking into account the age of the sender, the intentions of the sender, and the nature of the relationship between the sender and the recipient and the behavior of the recipient.

Laws regarding sexting vary greatly. Sexting may be a misdemeanor or a felony, depending on the state, the specific behavior, and the frequency. In the United States, 11 state laws include a diversion remedy—an option to pursue the case outside of the criminal juvenile system; 10 laws require counseling or another informal sanction; 11 states laws have the potential for misdemeanor punishment; and 4 state laws have the potential for felony punishment.14 Depending on the criminal charge, the perpetrator may have to register as a sex offender. For example, in some jurisdictions, a conviction for possession of child pornography requires sex offender registration. Thirty-eight states include juvenile sex offenders in their sex offender registries. Other states require juveniles to register if they are age ≥15 years or have been tried as an adult.15

The frequency of police involvement in sexting cases also greatly varies. A national study examining the characteristics of youth sexting cases revealed that law enforcement agencies handled approximately 3,477 cases of youth-produced sexual photos in 2008 and 2009.16 Situations that involved an adult or a minor engaged in malicious, nonconsensual, or abusive behavior comprised two-thirds of cases. Arrests occurred in 62% of the adult-involved cases and 36% of the aggravated youth-only cases. Arrests occurred in only 18% of investigated non-aggravated youth-only cases. Table 2 describes recent American sexting legal cases and their outcomes.

In K’s case, depending on the jurisdiction, K or her ex-boyfriend may be subject to arrest for child pornography, revenge pornography, or sexting.

Potential social and psychiatric consequences

What are the social and psychiatric ramifications for K? Aside from potential legal consequences of sexting, K is experiencing psychological and social consequences. She has developed depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Her ex-boyfriend’s dissemination of her nude photos on the school computer could be interpreted as cyberbullying. (The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children defines cyberbullying as “bullying through the use of technology or electronic devices such as telephones, cell phones, computers, and the Internet.”17 All 50 states have enacted laws against bullying; 48 states have electronic harassment in their bullying laws; and 22 states have laws specifically referencing “cyberbullying.”)

Her depressive symptoms developed in response to her feelings of guilt and shame related to sexting as well as the subsequent peer harassment. She is refusing to return to school because of her concerns about bullying. A careful inquiry into suicidality should be part of the evaluation when sexting has led to psychiatric symptoms. Several cases of sexting and cyberbullying have ended in suicide (Table 3).

How to ask patients about sexting

To screen patients for sexting, clinicians need to develop a new skill set, which at first may be uncomfortable. However, the questions to ask are not all that different from other questions about adolescent and young adult sexuality. The importance of patients seeing that we as physicians are comfortable with the topic and approachable about their sexual health cannot be overemphasized. When discussing sexting with patients, it is essential to:

- explain that you are asking questions about their sexual health because they are important to overall health

- engage patients in discussion in a nonthreatening and nonjudgmental way

- develop rapport so patients feel comfortable disclosing behavior that may be embarrassing

- listen to their stories and build a context for understanding their experiences. As you listen, ask questions when needed to help move the story along.

Sometimes when asking about topics that are uncomfortable, clinicians revert from open-ended to closed-ended questions, but when asking about a patient’s sexual life, it is especially important to be open-ended and ask questions in a nonjudgmental way. Contextualizing sexual questions by (for example) asking them while discussing the teen’s relationships will make them seem more natural.18 To best understand, inquire explicitly about specific behaviors, but do so without appearing voyeuristic.18

Sexting may precede sexual intercourse. Keep in mind that a patient may report that she (he) is not sexually active but still may be involved in sexting. Therefore, discuss sexting even if your patient reports not being sexually active. By understanding the prevalence of sexting among teens, you can ask questions in a normalizing way. Clinicians can inquire about sexting while discussing relationships and dating or online risk behaviors.

Also consider whether any of your patient’s sexual behaviors, including sexting, are the result of coercion: “Some of my patients tell me they feel pressured or coerced into having sex. Have you ever felt this way?”19 and “Have you ever been picked on or bullied? Is that still a problem?” are suggested safety screening questions about bullying,18 and one can also ask about specific cyberbullying behaviors.

1. Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Jones LM, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of youth sexting: a national study. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):13-20.

2. Lenhart A. Teens and sexting. The Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2009/12/15/teens-and-sexting. Published December 15, 2009. Accessed October 31, 2017.

3. Temple JR, Paul JA, van den Berg P, et al. Teen sexting and its association with sexual behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(9):828-833.

4. Gordon-Messer D, Bauermeister JA, Grodzinski A, et al. Sexting among young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):301-306.

5. Henderson L. Sexting and sexual relationships among teens and young adults. McNair Scholars Research Journal. 2011;7(1):31-39.

6. The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Sex and tech: results from a survey of teens and young adults. https://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/sex_and_tech_summary.pdf. Published December 2008. Accessed October 31, 2017.

7. Strassberg DS, McKinnon RK, Sustaíta MA, et al. Sexting by high school students: an exploratory and descriptive study. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(1):15-21.

8. Houck CD, Barker D, Rizzo C, et al. Sexting and sexual behavior in at-risk adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):e276-e282.

9. Benotsch EG, Snipes DJ, Martin AM, et al. Sexting, substance use, and sexual risk behavior in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):307-313.

10. Delevi R, Weisskirch RS. Personality factors as predictors of sexting. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(6):2589-2594.

11. Temple JR, Choi H. Longitudinal association between teen sexting and sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):1287-1292.

12. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psych Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

13. Citron DK, Franks MA. Criminalizing revenge porn. Wake Forest Law Review. 2014;49:345-391.

14. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. State cyberbullying laws: a brief review of state cyberbullying laws and policies. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/Bullying-and-Cyberbullying-Laws.pdf. Updated 2016. Accessed October 31, 2017.

15. Beitsch R. States slowly scale back juvenile sex offender registries. The Pew Charitable Trusts. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2015/11/19/states-slowly-scale-back-juvenile-sex-offender-registries. Published November 19, 2015. Accessed October 31, 2017.

16. Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ. How often are teens arrested for sexting? Data from a national sample of police cases. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):4-12.

17. The Campus School at Boston College. Bullying prevention policy. https://www.bc.edu/bc-web/schools/lsoe/sites/campus-school/who-we-are/policies-and-procedures/bullying-prevention-policy.html. Accessed October 31, 2017.

18. Goldenring JM, Rosen DS. Getting into adolescent heads: an essential update. Contemporary Pediatrics. 2004;21(1):64.

19. Klein DA, Goldenring JM, Adelman WP. HEEADSSS 3.0: the psychosocial interview for adolescents updated for a new century fueled by media. Contemporary Pediatrics. http://contemporarypediatrics.modernmedicine.com/contemporary-pediatrics/content/tags/adolescent-medicine/heeadsss-30-psychosocial-interview-adolesce?page=full. Published January 1, 2014. Accessed October 31, 2017.

1. Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Jones LM, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of youth sexting: a national study. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):13-20.

2. Lenhart A. Teens and sexting. The Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2009/12/15/teens-and-sexting. Published December 15, 2009. Accessed October 31, 2017.

3. Temple JR, Paul JA, van den Berg P, et al. Teen sexting and its association with sexual behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(9):828-833.

4. Gordon-Messer D, Bauermeister JA, Grodzinski A, et al. Sexting among young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):301-306.

5. Henderson L. Sexting and sexual relationships among teens and young adults. McNair Scholars Research Journal. 2011;7(1):31-39.

6. The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Sex and tech: results from a survey of teens and young adults. https://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/sex_and_tech_summary.pdf. Published December 2008. Accessed October 31, 2017.

7. Strassberg DS, McKinnon RK, Sustaíta MA, et al. Sexting by high school students: an exploratory and descriptive study. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(1):15-21.

8. Houck CD, Barker D, Rizzo C, et al. Sexting and sexual behavior in at-risk adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):e276-e282.

9. Benotsch EG, Snipes DJ, Martin AM, et al. Sexting, substance use, and sexual risk behavior in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):307-313.

10. Delevi R, Weisskirch RS. Personality factors as predictors of sexting. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(6):2589-2594.

11. Temple JR, Choi H. Longitudinal association between teen sexting and sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):1287-1292.

12. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psych Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

13. Citron DK, Franks MA. Criminalizing revenge porn. Wake Forest Law Review. 2014;49:345-391.

14. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. State cyberbullying laws: a brief review of state cyberbullying laws and policies. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://cyberbullying.org/Bullying-and-Cyberbullying-Laws.pdf. Updated 2016. Accessed October 31, 2017.

15. Beitsch R. States slowly scale back juvenile sex offender registries. The Pew Charitable Trusts. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2015/11/19/states-slowly-scale-back-juvenile-sex-offender-registries. Published November 19, 2015. Accessed October 31, 2017.

16. Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ. How often are teens arrested for sexting? Data from a national sample of police cases. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):4-12.

17. The Campus School at Boston College. Bullying prevention policy. https://www.bc.edu/bc-web/schools/lsoe/sites/campus-school/who-we-are/policies-and-procedures/bullying-prevention-policy.html. Accessed October 31, 2017.

18. Goldenring JM, Rosen DS. Getting into adolescent heads: an essential update. Contemporary Pediatrics. 2004;21(1):64.

19. Klein DA, Goldenring JM, Adelman WP. HEEADSSS 3.0: the psychosocial interview for adolescents updated for a new century fueled by media. Contemporary Pediatrics. http://contemporarypediatrics.modernmedicine.com/contemporary-pediatrics/content/tags/adolescent-medicine/heeadsss-30-psychosocial-interview-adolesce?page=full. Published January 1, 2014. Accessed October 31, 2017.

The dawn of precision psychiatry

Imagine being able to precisely select the medication with the optimal efficacy, safety, and tolerability at the outset of treatment for every psychiatric patient who needs pharmacotherapy. Imagine how much the patient would appreciate not receiving a series of drugs and suffering multiple adverse effects and unremitting symptoms until the “right medication” is identified. Imagine how gratifying it would be for you as a psychiatrist to watch every one of your patients improve rapidly with minimal complaints or adverse effects.

Precision psychiatry is the indispensable vehicle to achieve personalized medicine for psychiatric patients. Precision psychiatry is a cherished goal, but it remains an aspirational objective. Other medical specialties, especially oncology and cardiology, have made remarkable strides in precision medicine, but the journey to precision psychiatry is still in its early stages. Yet there is every reason to believe that we are making progress toward that cherished goal.

To implement precision psychiatry, we must be able to identify the biosignature of each patient’s psychiatric brain disorder. But there is a formidable challenge to overcome: the complex, extensive heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders, which requires intense and inspired neurobiology research. So, while clinicians go on with the mundane trial-and-error approach of contemporary psychopharmacology, psychiatric neuroscientists are diligently deconstructing major psychiatric disorders into specific biotypes with unique biosignatures that will one day guide accurate and prompt clinical management.

Psychiatric practitioners may be too busy to keep tabs on the progress being made in identifying various biomarkers that are the key ingredients to decoding the biosignature of each psychiatric patient. Take schizophrenia, for example. There are myriad clinical variations that comprise this heterogeneous brain syndrome, including level of premorbid functioning; acute vs gradual onset of psychosis; the type and severity of hallucinations or delusions; the dimensional spectrum of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments; the presence and intensity of suicidal or homicidal urges; and the type of medical and psychiatric comorbidities. No wonder every patient is a unique and fascinating clinical puzzle, and yet, patients with schizophrenia are still being homogenized under a single DSM diagnostic category.

There are hundreds of biomarkers in schizophrenia,1 but none can be used clinically until the biosignatures of the many diseases within the schizophrenia syndrome are identified. That grueling research quest will take time, given that so far >340 risk genes for schizophrenia have been discovered, along with countless copy number variants representing gene deletions or duplications, plus dozens of de novo mutations that preclude coding for any protein. Add to these the numerous prenatal pregnancy adverse events, delivery complications, and early childhood abuse—all of which are associated with neurodevelopmental disruptions that set up the brain for schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adulthood—and we have a perplexing conundrum to tackle.

Precision psychiatry will ultimately enable practitioners to recognize various psychotic diseases that are more specific than the current DSM psychosis categories. Further, precision psychiatry will provide guidance as to which member within a class of so-called “me-too” drugs is the optimal match for each patient. This will stand in stark contrast to the chaotic hit-or-miss approach.

Precision psychiatry also will reveal the absurdity of current FDA clinical trials design for drug development. How can a molecule with a putative mechanism of action relevant to a specific biotype be administered to a hodgepodge of heterogeneous biotypes that have been lumped in 1 clinical category, and yet be expected to exert efficacy in most biotypes? It is a small miracle that some new drugs beat placebo despite the extensive variability in both placebo responses and drug responses. But it is well known that in all FDA placebo-controlled trials, the therapeutic response across the patient population varies from extremely high to extremely low, and worsening may even occur in a subset of patients receiving either the active drug or placebo. Perhaps drug response should be used as 1 methodology to classify biotypes of patients encompassed within a heterogeneous syndrome such as schizophrenia.

Precision psychiatry will represent a huge paradigm shift in the science and practice of our specialty. In his landmark book, Thomas Kuhn defined a paradigm as “an entire worldview in which a theory exists and all the implications that come from that view.”2 Precision psychiatry will completely disrupt the current antiquated clinical paradigm, transforming psychiatry into the clinical neuroscience it is. Many “omics,” such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, and metagenomics, will inevitably find their way into the jargon of psychiatrists.3

A marriage of science and technology is essential for the emergence of precision psychiatry. To achieve this transformative amalgamation, we need to reconfigure our concepts, reengineer our methods, reinvent our models, and redesign our approaches to patient care.

As Peter Drucker said, “The best way to predict the future is to create it.”4 Precision psychiatry is our future. Let’s create it!

1. Nasrallah HA.

2. Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1964.

3. Nasrallah HA. Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):17-18.

4. Cohen WA. Drucker on leadership: new lessons from the father of modern management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

Imagine being able to precisely select the medication with the optimal efficacy, safety, and tolerability at the outset of treatment for every psychiatric patient who needs pharmacotherapy. Imagine how much the patient would appreciate not receiving a series of drugs and suffering multiple adverse effects and unremitting symptoms until the “right medication” is identified. Imagine how gratifying it would be for you as a psychiatrist to watch every one of your patients improve rapidly with minimal complaints or adverse effects.

Precision psychiatry is the indispensable vehicle to achieve personalized medicine for psychiatric patients. Precision psychiatry is a cherished goal, but it remains an aspirational objective. Other medical specialties, especially oncology and cardiology, have made remarkable strides in precision medicine, but the journey to precision psychiatry is still in its early stages. Yet there is every reason to believe that we are making progress toward that cherished goal.

To implement precision psychiatry, we must be able to identify the biosignature of each patient’s psychiatric brain disorder. But there is a formidable challenge to overcome: the complex, extensive heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders, which requires intense and inspired neurobiology research. So, while clinicians go on with the mundane trial-and-error approach of contemporary psychopharmacology, psychiatric neuroscientists are diligently deconstructing major psychiatric disorders into specific biotypes with unique biosignatures that will one day guide accurate and prompt clinical management.

Psychiatric practitioners may be too busy to keep tabs on the progress being made in identifying various biomarkers that are the key ingredients to decoding the biosignature of each psychiatric patient. Take schizophrenia, for example. There are myriad clinical variations that comprise this heterogeneous brain syndrome, including level of premorbid functioning; acute vs gradual onset of psychosis; the type and severity of hallucinations or delusions; the dimensional spectrum of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments; the presence and intensity of suicidal or homicidal urges; and the type of medical and psychiatric comorbidities. No wonder every patient is a unique and fascinating clinical puzzle, and yet, patients with schizophrenia are still being homogenized under a single DSM diagnostic category.

There are hundreds of biomarkers in schizophrenia,1 but none can be used clinically until the biosignatures of the many diseases within the schizophrenia syndrome are identified. That grueling research quest will take time, given that so far >340 risk genes for schizophrenia have been discovered, along with countless copy number variants representing gene deletions or duplications, plus dozens of de novo mutations that preclude coding for any protein. Add to these the numerous prenatal pregnancy adverse events, delivery complications, and early childhood abuse—all of which are associated with neurodevelopmental disruptions that set up the brain for schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adulthood—and we have a perplexing conundrum to tackle.

Precision psychiatry will ultimately enable practitioners to recognize various psychotic diseases that are more specific than the current DSM psychosis categories. Further, precision psychiatry will provide guidance as to which member within a class of so-called “me-too” drugs is the optimal match for each patient. This will stand in stark contrast to the chaotic hit-or-miss approach.

Precision psychiatry also will reveal the absurdity of current FDA clinical trials design for drug development. How can a molecule with a putative mechanism of action relevant to a specific biotype be administered to a hodgepodge of heterogeneous biotypes that have been lumped in 1 clinical category, and yet be expected to exert efficacy in most biotypes? It is a small miracle that some new drugs beat placebo despite the extensive variability in both placebo responses and drug responses. But it is well known that in all FDA placebo-controlled trials, the therapeutic response across the patient population varies from extremely high to extremely low, and worsening may even occur in a subset of patients receiving either the active drug or placebo. Perhaps drug response should be used as 1 methodology to classify biotypes of patients encompassed within a heterogeneous syndrome such as schizophrenia.

Precision psychiatry will represent a huge paradigm shift in the science and practice of our specialty. In his landmark book, Thomas Kuhn defined a paradigm as “an entire worldview in which a theory exists and all the implications that come from that view.”2 Precision psychiatry will completely disrupt the current antiquated clinical paradigm, transforming psychiatry into the clinical neuroscience it is. Many “omics,” such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, and metagenomics, will inevitably find their way into the jargon of psychiatrists.3

A marriage of science and technology is essential for the emergence of precision psychiatry. To achieve this transformative amalgamation, we need to reconfigure our concepts, reengineer our methods, reinvent our models, and redesign our approaches to patient care.

As Peter Drucker said, “The best way to predict the future is to create it.”4 Precision psychiatry is our future. Let’s create it!

Imagine being able to precisely select the medication with the optimal efficacy, safety, and tolerability at the outset of treatment for every psychiatric patient who needs pharmacotherapy. Imagine how much the patient would appreciate not receiving a series of drugs and suffering multiple adverse effects and unremitting symptoms until the “right medication” is identified. Imagine how gratifying it would be for you as a psychiatrist to watch every one of your patients improve rapidly with minimal complaints or adverse effects.

Precision psychiatry is the indispensable vehicle to achieve personalized medicine for psychiatric patients. Precision psychiatry is a cherished goal, but it remains an aspirational objective. Other medical specialties, especially oncology and cardiology, have made remarkable strides in precision medicine, but the journey to precision psychiatry is still in its early stages. Yet there is every reason to believe that we are making progress toward that cherished goal.

To implement precision psychiatry, we must be able to identify the biosignature of each patient’s psychiatric brain disorder. But there is a formidable challenge to overcome: the complex, extensive heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders, which requires intense and inspired neurobiology research. So, while clinicians go on with the mundane trial-and-error approach of contemporary psychopharmacology, psychiatric neuroscientists are diligently deconstructing major psychiatric disorders into specific biotypes with unique biosignatures that will one day guide accurate and prompt clinical management.

Psychiatric practitioners may be too busy to keep tabs on the progress being made in identifying various biomarkers that are the key ingredients to decoding the biosignature of each psychiatric patient. Take schizophrenia, for example. There are myriad clinical variations that comprise this heterogeneous brain syndrome, including level of premorbid functioning; acute vs gradual onset of psychosis; the type and severity of hallucinations or delusions; the dimensional spectrum of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments; the presence and intensity of suicidal or homicidal urges; and the type of medical and psychiatric comorbidities. No wonder every patient is a unique and fascinating clinical puzzle, and yet, patients with schizophrenia are still being homogenized under a single DSM diagnostic category.

There are hundreds of biomarkers in schizophrenia,1 but none can be used clinically until the biosignatures of the many diseases within the schizophrenia syndrome are identified. That grueling research quest will take time, given that so far >340 risk genes for schizophrenia have been discovered, along with countless copy number variants representing gene deletions or duplications, plus dozens of de novo mutations that preclude coding for any protein. Add to these the numerous prenatal pregnancy adverse events, delivery complications, and early childhood abuse—all of which are associated with neurodevelopmental disruptions that set up the brain for schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adulthood—and we have a perplexing conundrum to tackle.

Precision psychiatry will ultimately enable practitioners to recognize various psychotic diseases that are more specific than the current DSM psychosis categories. Further, precision psychiatry will provide guidance as to which member within a class of so-called “me-too” drugs is the optimal match for each patient. This will stand in stark contrast to the chaotic hit-or-miss approach.

Precision psychiatry also will reveal the absurdity of current FDA clinical trials design for drug development. How can a molecule with a putative mechanism of action relevant to a specific biotype be administered to a hodgepodge of heterogeneous biotypes that have been lumped in 1 clinical category, and yet be expected to exert efficacy in most biotypes? It is a small miracle that some new drugs beat placebo despite the extensive variability in both placebo responses and drug responses. But it is well known that in all FDA placebo-controlled trials, the therapeutic response across the patient population varies from extremely high to extremely low, and worsening may even occur in a subset of patients receiving either the active drug or placebo. Perhaps drug response should be used as 1 methodology to classify biotypes of patients encompassed within a heterogeneous syndrome such as schizophrenia.

Precision psychiatry will represent a huge paradigm shift in the science and practice of our specialty. In his landmark book, Thomas Kuhn defined a paradigm as “an entire worldview in which a theory exists and all the implications that come from that view.”2 Precision psychiatry will completely disrupt the current antiquated clinical paradigm, transforming psychiatry into the clinical neuroscience it is. Many “omics,” such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, and metagenomics, will inevitably find their way into the jargon of psychiatrists.3

A marriage of science and technology is essential for the emergence of precision psychiatry. To achieve this transformative amalgamation, we need to reconfigure our concepts, reengineer our methods, reinvent our models, and redesign our approaches to patient care.

As Peter Drucker said, “The best way to predict the future is to create it.”4 Precision psychiatry is our future. Let’s create it!

1. Nasrallah HA.

2. Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1964.

3. Nasrallah HA. Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):17-18.

4. Cohen WA. Drucker on leadership: new lessons from the father of modern management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

1. Nasrallah HA.

2. Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1964.

3. Nasrallah HA. Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):17-18.

4. Cohen WA. Drucker on leadership: new lessons from the father of modern management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

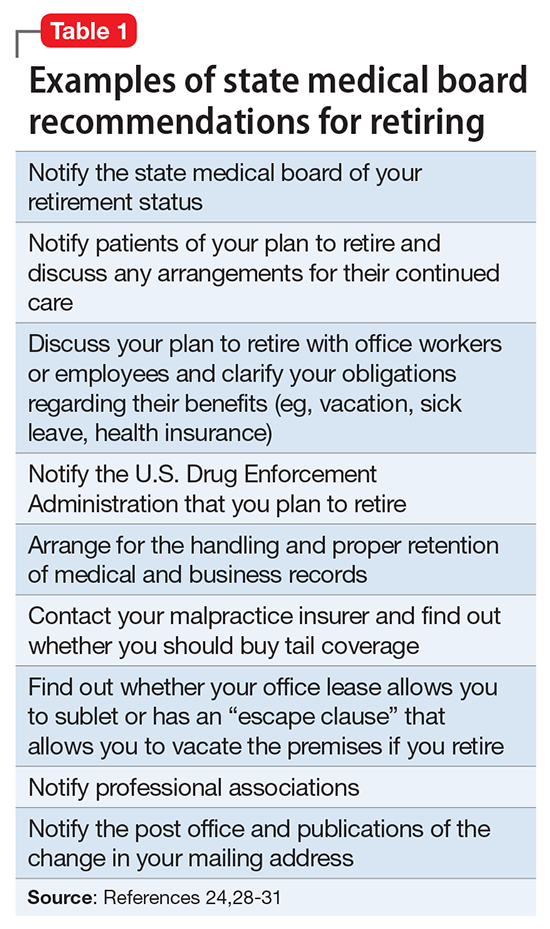

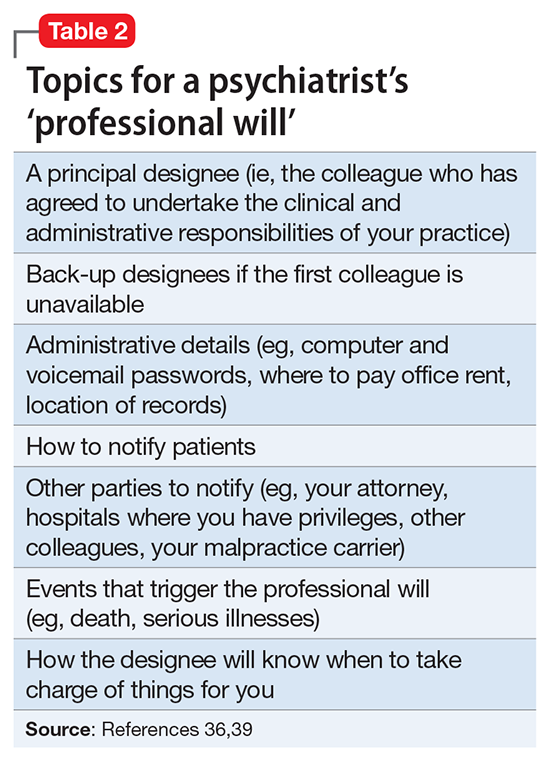

The end of the line: Concluding your practice when facing serious illness

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I have a possibly fatal disease. So far, my symptoms and treatment haven’t kept me from my usual activities. But if my illness worsens, I’ll have to quit practicing psychiatry. What should I be doing now to make sure I fulfill my ethical and legal obligations to my patients?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

“Remember, with great power comes great responsibility.”

- Peter Parker, Spider-Man (2002)

Peter Parker’s movie-ending statement applies to doctors as well as Spider-Man. Although we don’t swing from building to building to save cities from heinous villains, practicing medicine is a privilege that society bestows only upon physicians who retain the knowledge, skills, and ability to treat patients competently.

Doctors retire from practice for many reasons, including when deteriorating physical health or cognitive capacity prevents them from performing clinical duties properly. Dr. F’s situation is not rare. As the physician population ages,1,2 a growing number of his colleagues will face similar circumstances,3,4 and with them, the responsibility and emotional turmoil of arranging to end their medical practices.

In many ways, concluding a psychiatric practice is similar to retiring from practice in other specialties. But because we care for patients’ minds as well as their bodies, retirement affects psychiatrists in distinctive ways that reflect our patients’ feelings toward us and our feelings toward them. To answer Dr. F’s question, this article considers having to stop practicing from 3 vantage points:

- the emotional impact on patients

- the emotional impact on the psychiatrist

- fulfilling one’s legal obligations while attending to the emotions of patients as well as oneself.

Emotional impact on patients

A content analysis study suggests that the traits patients appreciate in family physicians include the availability to listen, caring and compassion, trusted medical judgment, conveying the patient’s importance during encounters, feelings of connectedness, knowledge and understanding of the patient’s family, and relationship longevity.5 The same factors likely apply to relationships between psychiatrists and their patients, particularly if treatment encounters have extended over years and have involved conversations beyond those needed merely to write prescriptions.

Psychoanalytic publications offer many descriptions of patients’ reactions to the illness or death of their mental health professional. A 1978 study of 27 analysands whose physicians died during ongoing therapy reported reactions that ranged from a minimal impact to protracted mourning accompanied by helplessness, intense crying, and recurrent dreams about the analyst.6 Although a few patients were relieved that death had ended a difficult treatment, many were angry at their doctor for not attending to self-care and for breaking their treatment agreement, or because they had missed out on hoped-for benefits.

A 2010 study described the pain and distress that patients may experience following the death of their analyst or psychotherapist. These accounts emphasized the emotional isolation of grieving patients, who do not have the social support that bereaved persons receive after losing a loved one.7 Successful psychotherapy provides a special relationship characterized by trust, intimacy, and safety. But if the therapist suddenly dies, this relationship “is transformed into a solitude like no other.”8

Because the sudden “rupture of an analytic process is bound to be traumatic and may cause iatrogenic injury to the patient,” Traesdal9 advocates that therapists in situations similar to Dr. F’s discuss their possible death “on the reality level at least once during any analysis or psychotherapy.… It is extremely helpful to a patient to have discussed … how to handle the situation” if the therapist dies. This discussion also offers the patient an opportunity to confront a cultural taboo around death and to increase capacity to tolerate pain, illness, and aging.10,11

Most psychiatric care today is not psychoanalysis; psychiatrists provide other forms of care that create less intense doctor–patient relationships. Yet knowledge of these kinds of reactions may help Dr. F stay attuned to his patients’ concerns and to contemplate what they may experience, to greater or lesser degrees, if his health declines.

Retirement’s emotional impact on the psychiatrist

Published guidance on concluding a psychiatric practice is sparse, considering that all psychiatrists are mortal and stop practicing at some point.12Not thinking about or planning for retirement is a psychiatric tradition that started with Freud. He saw patients until shortly before his death and did not seem to have planned for ending his practice, despite suffering with jaw cancer for 16 years.13

Practicing medicine often is more than just a career; it is a core aspect of many physicians’ identity.14 Most of us spend a large fraction of our waking hours caring for patients and meeting other job requirements (eg, teaching, maintaining knowledge and skills), and many of us have scant time to pursue nonmedical interests. An intense prioritization of one’s “medical identity” makes retirement a blow to a doctor’s self-worth and sense of meaning in life.15,16