User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Sleep disturbance not linked to age or IQ in early ASD

Sleep disturbance is not associated with age and IQ in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and disruptive behaviors, according to Cynthia R. Johnson, PhD, and her associates.

They assessed 177 children aged 3-7 who were participating in the Research Units on Behavioral Intervention study, a 24-week trial. All of the children had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, based on DSM-IV criteria. The diagnoses were corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised.

The children were randomized into a parent training group or a parent education group. After getting parents to complete several forms, including the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, Dr. Johnson and her associates found no age differences between children who fell into the category of “good sleepers” (n = 52), and those characterized as “poor sleepers” (n = 46) (P = .57). In both sleep groups, more than 70% of the children had an IQ of 70 or above, and no significant difference was found in good sleepers, compared with poor sleepers, in IQ variable (P = .87) (Sleep Med. 2018. 44:61-6).

In addition, the researchers found that poor sleepers had significantly higher scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist subscales of irritability, hyperactivity, stereotypic behavior, and social withdrawal/lethargy, compared with good sleepers. All subscales of the parenting stress index and the PSI total score also were significantly higher in the poor sleepers group, compared with children in the good sleepers group, reported Dr. Johnson of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates.

Additional studies are needed within a “comprehensive biopsychosocial model” to advance the understanding of why some children with autism experience disrupted sleep patterns and others do not. “, regardless of age and cognitive level,” Dr. Johnson and her associates concluded. “With improved sleep, better outcomes for children with ASD could be expected.”

Read the full study in Sleep Medicine

Sleep disturbance is not associated with age and IQ in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and disruptive behaviors, according to Cynthia R. Johnson, PhD, and her associates.

They assessed 177 children aged 3-7 who were participating in the Research Units on Behavioral Intervention study, a 24-week trial. All of the children had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, based on DSM-IV criteria. The diagnoses were corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised.

The children were randomized into a parent training group or a parent education group. After getting parents to complete several forms, including the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, Dr. Johnson and her associates found no age differences between children who fell into the category of “good sleepers” (n = 52), and those characterized as “poor sleepers” (n = 46) (P = .57). In both sleep groups, more than 70% of the children had an IQ of 70 or above, and no significant difference was found in good sleepers, compared with poor sleepers, in IQ variable (P = .87) (Sleep Med. 2018. 44:61-6).

In addition, the researchers found that poor sleepers had significantly higher scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist subscales of irritability, hyperactivity, stereotypic behavior, and social withdrawal/lethargy, compared with good sleepers. All subscales of the parenting stress index and the PSI total score also were significantly higher in the poor sleepers group, compared with children in the good sleepers group, reported Dr. Johnson of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates.

Additional studies are needed within a “comprehensive biopsychosocial model” to advance the understanding of why some children with autism experience disrupted sleep patterns and others do not. “, regardless of age and cognitive level,” Dr. Johnson and her associates concluded. “With improved sleep, better outcomes for children with ASD could be expected.”

Read the full study in Sleep Medicine

Sleep disturbance is not associated with age and IQ in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and disruptive behaviors, according to Cynthia R. Johnson, PhD, and her associates.

They assessed 177 children aged 3-7 who were participating in the Research Units on Behavioral Intervention study, a 24-week trial. All of the children had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, based on DSM-IV criteria. The diagnoses were corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised.

The children were randomized into a parent training group or a parent education group. After getting parents to complete several forms, including the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire, Dr. Johnson and her associates found no age differences between children who fell into the category of “good sleepers” (n = 52), and those characterized as “poor sleepers” (n = 46) (P = .57). In both sleep groups, more than 70% of the children had an IQ of 70 or above, and no significant difference was found in good sleepers, compared with poor sleepers, in IQ variable (P = .87) (Sleep Med. 2018. 44:61-6).

In addition, the researchers found that poor sleepers had significantly higher scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist subscales of irritability, hyperactivity, stereotypic behavior, and social withdrawal/lethargy, compared with good sleepers. All subscales of the parenting stress index and the PSI total score also were significantly higher in the poor sleepers group, compared with children in the good sleepers group, reported Dr. Johnson of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and her associates.

Additional studies are needed within a “comprehensive biopsychosocial model” to advance the understanding of why some children with autism experience disrupted sleep patterns and others do not. “, regardless of age and cognitive level,” Dr. Johnson and her associates concluded. “With improved sleep, better outcomes for children with ASD could be expected.”

Read the full study in Sleep Medicine

FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

Poor sleep, suicide risk linked in college students

Suicidal behaviors are associated with poor sleep in college students, even after controlling for depression, a cross-sectional analysis shows. Specifically, students were 6.54 times as likely to be classified with suicide risk if they were depressed and 2.70 times as likely if they had poor quality of sleep.

“Our findings add to a growing body of literature pointing to sleep as an important component to include in screening and intervention efforts to prevent suicidal ideation and attempts on college campuses,” wrote Stephen P. Becker, PhD, a pediatric psychologist affiliated with Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his colleagues.

Of the 1,700 college students included in this study (J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Jan 12:99:122-8), 82.7% of those classified with suicide risk had poor sleep quality, but only 31.3% of those with poor sleep quality were classified with suicide risk.

Most previous studies had looked only at insomnia or bad dreams rather than other aspects of poor sleep quality, and because this study used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, it was able to evaluate additional well-validated components of sleep. so that screening and intervention based on sleep quality can be more effective. This is important, because suicide is one of the leading causes of death among young adults.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

Read more about this study in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Suicidal behaviors are associated with poor sleep in college students, even after controlling for depression, a cross-sectional analysis shows. Specifically, students were 6.54 times as likely to be classified with suicide risk if they were depressed and 2.70 times as likely if they had poor quality of sleep.

“Our findings add to a growing body of literature pointing to sleep as an important component to include in screening and intervention efforts to prevent suicidal ideation and attempts on college campuses,” wrote Stephen P. Becker, PhD, a pediatric psychologist affiliated with Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his colleagues.

Of the 1,700 college students included in this study (J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Jan 12:99:122-8), 82.7% of those classified with suicide risk had poor sleep quality, but only 31.3% of those with poor sleep quality were classified with suicide risk.

Most previous studies had looked only at insomnia or bad dreams rather than other aspects of poor sleep quality, and because this study used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, it was able to evaluate additional well-validated components of sleep. so that screening and intervention based on sleep quality can be more effective. This is important, because suicide is one of the leading causes of death among young adults.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

Read more about this study in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Suicidal behaviors are associated with poor sleep in college students, even after controlling for depression, a cross-sectional analysis shows. Specifically, students were 6.54 times as likely to be classified with suicide risk if they were depressed and 2.70 times as likely if they had poor quality of sleep.

“Our findings add to a growing body of literature pointing to sleep as an important component to include in screening and intervention efforts to prevent suicidal ideation and attempts on college campuses,” wrote Stephen P. Becker, PhD, a pediatric psychologist affiliated with Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his colleagues.

Of the 1,700 college students included in this study (J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Jan 12:99:122-8), 82.7% of those classified with suicide risk had poor sleep quality, but only 31.3% of those with poor sleep quality were classified with suicide risk.

Most previous studies had looked only at insomnia or bad dreams rather than other aspects of poor sleep quality, and because this study used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, it was able to evaluate additional well-validated components of sleep. so that screening and intervention based on sleep quality can be more effective. This is important, because suicide is one of the leading causes of death among young adults.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

Read more about this study in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Delayed treatment for psychosis can have ‘deleterious’ effects

The longer that patients with schizophrenia go without treatment for a psychotic episode, the more their hippocampus atrophies, suggests a study published Feb. 21 in JAMA Psychiatry.

To conduct the study, researchers studied 71 patients between March 5, 2013, and Oct. 8, 2014, who were experiencing their first psychotic episode and were antipsychotic naive. The research team matched those patients with 73 healthy controls, treated the patients with antipsychotics, and performed MRIs on members of both groups at baseline and 8 weeks later. The primary outcome measure was change in left and right hippocampal volume integrity, which is inversely associated with hippocampal atrophy.

Results showed that many patients with psychosis had lower median hippocampal volume integrity. Furthermore, those . The duration of untreated psychosis was correlated with both decreases, but this association was only significant with left hippocampal volume integrity.

This relationship is “consistent with a persistent, possibly deleterious, effect of untreated psychosis on brain structure,” wrote Donald C. Goff, MD, of the psychiatry department at New York University, and his associates. “Larger longitudinal studies of longer duration are needed to examine the association between [duration of untreated psychosis], hippocampal volume, and clinical outcomes.”

Dr. Goff reported receiving research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Stanley Medical Research Institute, and Avanir Pharmaceuticals. Another author reported receiving support from numerous entities and honoraria for serving on an advisory board for Allergan. No other disclosures were reported.

Read more at JAMA Psychiatry.

The longer that patients with schizophrenia go without treatment for a psychotic episode, the more their hippocampus atrophies, suggests a study published Feb. 21 in JAMA Psychiatry.

To conduct the study, researchers studied 71 patients between March 5, 2013, and Oct. 8, 2014, who were experiencing their first psychotic episode and were antipsychotic naive. The research team matched those patients with 73 healthy controls, treated the patients with antipsychotics, and performed MRIs on members of both groups at baseline and 8 weeks later. The primary outcome measure was change in left and right hippocampal volume integrity, which is inversely associated with hippocampal atrophy.

Results showed that many patients with psychosis had lower median hippocampal volume integrity. Furthermore, those . The duration of untreated psychosis was correlated with both decreases, but this association was only significant with left hippocampal volume integrity.

This relationship is “consistent with a persistent, possibly deleterious, effect of untreated psychosis on brain structure,” wrote Donald C. Goff, MD, of the psychiatry department at New York University, and his associates. “Larger longitudinal studies of longer duration are needed to examine the association between [duration of untreated psychosis], hippocampal volume, and clinical outcomes.”

Dr. Goff reported receiving research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Stanley Medical Research Institute, and Avanir Pharmaceuticals. Another author reported receiving support from numerous entities and honoraria for serving on an advisory board for Allergan. No other disclosures were reported.

Read more at JAMA Psychiatry.

The longer that patients with schizophrenia go without treatment for a psychotic episode, the more their hippocampus atrophies, suggests a study published Feb. 21 in JAMA Psychiatry.

To conduct the study, researchers studied 71 patients between March 5, 2013, and Oct. 8, 2014, who were experiencing their first psychotic episode and were antipsychotic naive. The research team matched those patients with 73 healthy controls, treated the patients with antipsychotics, and performed MRIs on members of both groups at baseline and 8 weeks later. The primary outcome measure was change in left and right hippocampal volume integrity, which is inversely associated with hippocampal atrophy.

Results showed that many patients with psychosis had lower median hippocampal volume integrity. Furthermore, those . The duration of untreated psychosis was correlated with both decreases, but this association was only significant with left hippocampal volume integrity.

This relationship is “consistent with a persistent, possibly deleterious, effect of untreated psychosis on brain structure,” wrote Donald C. Goff, MD, of the psychiatry department at New York University, and his associates. “Larger longitudinal studies of longer duration are needed to examine the association between [duration of untreated psychosis], hippocampal volume, and clinical outcomes.”

Dr. Goff reported receiving research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Stanley Medical Research Institute, and Avanir Pharmaceuticals. Another author reported receiving support from numerous entities and honoraria for serving on an advisory board for Allergan. No other disclosures were reported.

Read more at JAMA Psychiatry.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Virtual reality–based CBT may improve social participation in psychosis

Virtual reality–based cognitive-behavioral therapy could help reduce momentary paranoia and anxiety, and improve social cognition in individuals with psychotic disorders.

Researchers reported the results of a randomized controlled trial of personalized virtual reality-based cognitive-behavioral therapy in 116 patients with a DSM IV–diagnosed psychotic disorder and paranoid ideation in an article published online Feb. 8 in Lancet Psychiatry.

Similarly, the group that received virtual reality therapy showed significantly larger decreases in momentary anxiety, compared with those in the control group. Those decreases remained significant at follow-up.

Researchers also observed a significant drop in safety behaviors – such as lack of eye contact – in the group who received the virtual reality therapy. At follow-up, this group showed less paranoid ideation in the form of lower levels of ideas of persecution and social reference.

The treatment also was associated with a small increase in time spent with others at the 6-month follow-up; a decrease was seen in the control group. Patients who underwent virtual reality therapy also showed improvements in self-stigmatization and social functioning.

The authors noted that the benefits for social functioning might take some time to emerge after therapy, as patients in symptomatic remission do not immediately start spending more time with other people.

“When patients increasingly feel more comfortable in social situations and learn that other people are less threatening than anticipated, they might try and succeed to make and maintain social contacts and find hobbies and jobs,” the authors wrote.

However, no significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of depression and anxiety, or in quality of life measurements posttreatment and at follow-up.

Virtual reality–based CBT is intended to get around some of the limitations of exposure-based therapeutic exercises for paranoid ideation. In virtual reality settings, the environment and characters can be completely controlled by the therapist, and the therapy is real time rather than retrospective and therefore not as vulnerable to patient bias.

“Finally, many patients are reluctant or unable to undergo exposure because of strong paranoid fears or negative symptoms,” the authors wrote.

The therapy took place in four virtual social environments – a street, bus, café, and supermarket. The therapist was able to control the characteristics and responses of up to 40 human avatars, enabling personalized treatment exercises for each patient.

“Patients and therapists communicated during virtual reality sessions to explore and challenge suspicious thoughts during social situations, drop safety behaviors during social situations (such as avoiding eye contact with, keeping distance from, and refraining from communication with avatars), and test harm expectancies,” they wrote.

The sessions also were designed to target safety behaviors, such as avoiding eye contact, because such behavior prevents individuals from receiving social information that can improve social cognition and reduce the chance of incorrect paranoid appraisals.

Several limitations were cited. For example, because follow-up was restricted to 6 months, it was not possible to access the long-term effects of virtual reality-based CBT. Also, some of the patients opted not to participate in the study because traveling to the therapy location proved too frightening. “Thus our sample might have been biased, because some of the most paranoid and avoidant patients could not participate,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Fonds NutsOhra and Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30053-1.

Virtual reality–based cognitive-behavioral therapy could help reduce momentary paranoia and anxiety, and improve social cognition in individuals with psychotic disorders.

Researchers reported the results of a randomized controlled trial of personalized virtual reality-based cognitive-behavioral therapy in 116 patients with a DSM IV–diagnosed psychotic disorder and paranoid ideation in an article published online Feb. 8 in Lancet Psychiatry.

Similarly, the group that received virtual reality therapy showed significantly larger decreases in momentary anxiety, compared with those in the control group. Those decreases remained significant at follow-up.

Researchers also observed a significant drop in safety behaviors – such as lack of eye contact – in the group who received the virtual reality therapy. At follow-up, this group showed less paranoid ideation in the form of lower levels of ideas of persecution and social reference.

The treatment also was associated with a small increase in time spent with others at the 6-month follow-up; a decrease was seen in the control group. Patients who underwent virtual reality therapy also showed improvements in self-stigmatization and social functioning.

The authors noted that the benefits for social functioning might take some time to emerge after therapy, as patients in symptomatic remission do not immediately start spending more time with other people.

“When patients increasingly feel more comfortable in social situations and learn that other people are less threatening than anticipated, they might try and succeed to make and maintain social contacts and find hobbies and jobs,” the authors wrote.

However, no significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of depression and anxiety, or in quality of life measurements posttreatment and at follow-up.

Virtual reality–based CBT is intended to get around some of the limitations of exposure-based therapeutic exercises for paranoid ideation. In virtual reality settings, the environment and characters can be completely controlled by the therapist, and the therapy is real time rather than retrospective and therefore not as vulnerable to patient bias.

“Finally, many patients are reluctant or unable to undergo exposure because of strong paranoid fears or negative symptoms,” the authors wrote.

The therapy took place in four virtual social environments – a street, bus, café, and supermarket. The therapist was able to control the characteristics and responses of up to 40 human avatars, enabling personalized treatment exercises for each patient.

“Patients and therapists communicated during virtual reality sessions to explore and challenge suspicious thoughts during social situations, drop safety behaviors during social situations (such as avoiding eye contact with, keeping distance from, and refraining from communication with avatars), and test harm expectancies,” they wrote.

The sessions also were designed to target safety behaviors, such as avoiding eye contact, because such behavior prevents individuals from receiving social information that can improve social cognition and reduce the chance of incorrect paranoid appraisals.

Several limitations were cited. For example, because follow-up was restricted to 6 months, it was not possible to access the long-term effects of virtual reality-based CBT. Also, some of the patients opted not to participate in the study because traveling to the therapy location proved too frightening. “Thus our sample might have been biased, because some of the most paranoid and avoidant patients could not participate,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Fonds NutsOhra and Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30053-1.

Virtual reality–based cognitive-behavioral therapy could help reduce momentary paranoia and anxiety, and improve social cognition in individuals with psychotic disorders.

Researchers reported the results of a randomized controlled trial of personalized virtual reality-based cognitive-behavioral therapy in 116 patients with a DSM IV–diagnosed psychotic disorder and paranoid ideation in an article published online Feb. 8 in Lancet Psychiatry.

Similarly, the group that received virtual reality therapy showed significantly larger decreases in momentary anxiety, compared with those in the control group. Those decreases remained significant at follow-up.

Researchers also observed a significant drop in safety behaviors – such as lack of eye contact – in the group who received the virtual reality therapy. At follow-up, this group showed less paranoid ideation in the form of lower levels of ideas of persecution and social reference.

The treatment also was associated with a small increase in time spent with others at the 6-month follow-up; a decrease was seen in the control group. Patients who underwent virtual reality therapy also showed improvements in self-stigmatization and social functioning.

The authors noted that the benefits for social functioning might take some time to emerge after therapy, as patients in symptomatic remission do not immediately start spending more time with other people.

“When patients increasingly feel more comfortable in social situations and learn that other people are less threatening than anticipated, they might try and succeed to make and maintain social contacts and find hobbies and jobs,” the authors wrote.

However, no significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of depression and anxiety, or in quality of life measurements posttreatment and at follow-up.

Virtual reality–based CBT is intended to get around some of the limitations of exposure-based therapeutic exercises for paranoid ideation. In virtual reality settings, the environment and characters can be completely controlled by the therapist, and the therapy is real time rather than retrospective and therefore not as vulnerable to patient bias.

“Finally, many patients are reluctant or unable to undergo exposure because of strong paranoid fears or negative symptoms,” the authors wrote.

The therapy took place in four virtual social environments – a street, bus, café, and supermarket. The therapist was able to control the characteristics and responses of up to 40 human avatars, enabling personalized treatment exercises for each patient.

“Patients and therapists communicated during virtual reality sessions to explore and challenge suspicious thoughts during social situations, drop safety behaviors during social situations (such as avoiding eye contact with, keeping distance from, and refraining from communication with avatars), and test harm expectancies,” they wrote.

The sessions also were designed to target safety behaviors, such as avoiding eye contact, because such behavior prevents individuals from receiving social information that can improve social cognition and reduce the chance of incorrect paranoid appraisals.

Several limitations were cited. For example, because follow-up was restricted to 6 months, it was not possible to access the long-term effects of virtual reality-based CBT. Also, some of the patients opted not to participate in the study because traveling to the therapy location proved too frightening. “Thus our sample might have been biased, because some of the most paranoid and avoidant patients could not participate,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Fonds NutsOhra and Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30053-1.

FROM LANCET PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who received virtual reality–based CBT showed significantly less momentary paranoia and momentary anxiety, and less paranoid ideation, than controls.

Data source: Randomized controlled trial in 116 patients with psychotic disorders.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Fonds NutsOhra and Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Pot-Kolder RMCA et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30053-1.

Physicians often bypass cognition, depression screening in MS

SAN DIEGO – A new study finds that physicians at two . Physicians who did perform screening hardly ever used validated tools and often didn’t refer appropriate patients for higher-level care.

In addition, researchers interviewed 13 leading MS specialists from coast to coast and “found that about half reported not using formal screening tools to assess cognitive impairment and depression,” said study coauthor Tamar Sapir, PhD, chief scientific officer with Prime Education, a firm based in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., that provides a variety of health-related services such as training and research.

The study findings were presented at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. Three of the study authors spoke in interviews.

The researchers sought to understand how frequently MS patients are screened for cognitive problems and depression.

“Cognitive impairment is experienced by approximately half of patients with multiple sclerosis, yet many are never screened or treated, which can impact their daily activities, their ability to work, and overall quality of life,” Dr. Sapir said.

Depression, meanwhile, is believed to be much more common in patients with MS than in the general population, with one recent meta-analysis of 58 studies finding that the average prevalence was 31%. Other research suggests depression is underdiagnosed and undertreated in this population (J Neurol Sci. 2017 Jan 15;372:331-41; ISRN Neurology. 2012, Article ID 427102. doi: 10.5402/2012/427102).

For the current study, researchers tracked 300 patients at two unidentified MS clinics via their charts over a 2-year period from 2014 to 2016. Their median age was 52 years, 76% were women, and 15 had experienced at least one relapse within the previous 24 months.

“Screening for cognitive impairment and depression was documented for only 52% and 63% of MS patients, respectively, and only about a quarter of patients diagnosed with these conditions were referred to a higher level of care,” said lead author Guy J. Buckle, MD, MPH, of the Andrew C. Carlos MS Institute at Shepherd Center in Atlanta.

Among all 300 patients, just 2% and 4% were screened using a validated tool for cognitive impairment and depression, respectively.

The screening often turned up evidence of the conditions: Physicians saw signs of cognitive impairment in 69% and 78% of those screened aged under 65 years and aged 65 and older, respectively, and they detected depression in 71% and 54% of those screened in those two age groups, respectively.

Researchers also noted several disparities. “Cognitive screening was conducted more frequently in older, employed, or white patients, while the presence of cognitive impairment was documented more often in black, nonworking, and those on Medicare or Medicaid,” Dr. Buckle said. “Depression screening was performed most frequently in older or white patients, yet depression was more common in younger, nonworking patients and those on Medicare/Medicaid.”

In another part of their study, researchers surveyed 13 unidentified “national leaders” in MS research and treatment. Just seven said they used validated tools to screen for cognitive impairment and six said they used them to screen for depression.

“We hear from MS specialists that they want to be measuring for cognition but don’t know how to efficiently work it into their routine, how to approach the patient, and what tools to use,” said study coauthor Derrick S. Robertson, MD, of the University of South Florida, Tampa. “In addition, there is no one tool that is accepted in the MS treatment community.”

MS specialists who didn’t use the screening tests also pointed to factors like lack of reimbursement and lack of integration into electronic medical records. “Doubt very much that neurologists have time to use any of these tests,” one respondent said, referring to cognitive impairment screening.

What’s next? “There are several new exciting developments in clinical trials demonstrating efficacy of disease-modifying therapies in maintaining or improving cognition in patients with relapsing MS,” Dr. Robertson said. “This highlights the urgent need to overcome barriers to use of formal cognitive screening tools in clinical practice to identify patients who need a higher level of care, and perhaps even a change in treatment with the ultimate goal to improve quality of life and overall outcomes.”

Genentech funded the study through an educational grant. Dr. Sapir and three other study authors reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Buckle and Dr. Robertson reported multiple disclosures, including principle investigator and advisory board/panel member work.

SOURCE: Buckle GJ et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2018, abstract No. P161.

SAN DIEGO – A new study finds that physicians at two . Physicians who did perform screening hardly ever used validated tools and often didn’t refer appropriate patients for higher-level care.

In addition, researchers interviewed 13 leading MS specialists from coast to coast and “found that about half reported not using formal screening tools to assess cognitive impairment and depression,” said study coauthor Tamar Sapir, PhD, chief scientific officer with Prime Education, a firm based in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., that provides a variety of health-related services such as training and research.

The study findings were presented at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. Three of the study authors spoke in interviews.

The researchers sought to understand how frequently MS patients are screened for cognitive problems and depression.

“Cognitive impairment is experienced by approximately half of patients with multiple sclerosis, yet many are never screened or treated, which can impact their daily activities, their ability to work, and overall quality of life,” Dr. Sapir said.

Depression, meanwhile, is believed to be much more common in patients with MS than in the general population, with one recent meta-analysis of 58 studies finding that the average prevalence was 31%. Other research suggests depression is underdiagnosed and undertreated in this population (J Neurol Sci. 2017 Jan 15;372:331-41; ISRN Neurology. 2012, Article ID 427102. doi: 10.5402/2012/427102).

For the current study, researchers tracked 300 patients at two unidentified MS clinics via their charts over a 2-year period from 2014 to 2016. Their median age was 52 years, 76% were women, and 15 had experienced at least one relapse within the previous 24 months.

“Screening for cognitive impairment and depression was documented for only 52% and 63% of MS patients, respectively, and only about a quarter of patients diagnosed with these conditions were referred to a higher level of care,” said lead author Guy J. Buckle, MD, MPH, of the Andrew C. Carlos MS Institute at Shepherd Center in Atlanta.

Among all 300 patients, just 2% and 4% were screened using a validated tool for cognitive impairment and depression, respectively.

The screening often turned up evidence of the conditions: Physicians saw signs of cognitive impairment in 69% and 78% of those screened aged under 65 years and aged 65 and older, respectively, and they detected depression in 71% and 54% of those screened in those two age groups, respectively.

Researchers also noted several disparities. “Cognitive screening was conducted more frequently in older, employed, or white patients, while the presence of cognitive impairment was documented more often in black, nonworking, and those on Medicare or Medicaid,” Dr. Buckle said. “Depression screening was performed most frequently in older or white patients, yet depression was more common in younger, nonworking patients and those on Medicare/Medicaid.”

In another part of their study, researchers surveyed 13 unidentified “national leaders” in MS research and treatment. Just seven said they used validated tools to screen for cognitive impairment and six said they used them to screen for depression.

“We hear from MS specialists that they want to be measuring for cognition but don’t know how to efficiently work it into their routine, how to approach the patient, and what tools to use,” said study coauthor Derrick S. Robertson, MD, of the University of South Florida, Tampa. “In addition, there is no one tool that is accepted in the MS treatment community.”

MS specialists who didn’t use the screening tests also pointed to factors like lack of reimbursement and lack of integration into electronic medical records. “Doubt very much that neurologists have time to use any of these tests,” one respondent said, referring to cognitive impairment screening.

What’s next? “There are several new exciting developments in clinical trials demonstrating efficacy of disease-modifying therapies in maintaining or improving cognition in patients with relapsing MS,” Dr. Robertson said. “This highlights the urgent need to overcome barriers to use of formal cognitive screening tools in clinical practice to identify patients who need a higher level of care, and perhaps even a change in treatment with the ultimate goal to improve quality of life and overall outcomes.”

Genentech funded the study through an educational grant. Dr. Sapir and three other study authors reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Buckle and Dr. Robertson reported multiple disclosures, including principle investigator and advisory board/panel member work.

SOURCE: Buckle GJ et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2018, abstract No. P161.

SAN DIEGO – A new study finds that physicians at two . Physicians who did perform screening hardly ever used validated tools and often didn’t refer appropriate patients for higher-level care.

In addition, researchers interviewed 13 leading MS specialists from coast to coast and “found that about half reported not using formal screening tools to assess cognitive impairment and depression,” said study coauthor Tamar Sapir, PhD, chief scientific officer with Prime Education, a firm based in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., that provides a variety of health-related services such as training and research.

The study findings were presented at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. Three of the study authors spoke in interviews.

The researchers sought to understand how frequently MS patients are screened for cognitive problems and depression.

“Cognitive impairment is experienced by approximately half of patients with multiple sclerosis, yet many are never screened or treated, which can impact their daily activities, their ability to work, and overall quality of life,” Dr. Sapir said.

Depression, meanwhile, is believed to be much more common in patients with MS than in the general population, with one recent meta-analysis of 58 studies finding that the average prevalence was 31%. Other research suggests depression is underdiagnosed and undertreated in this population (J Neurol Sci. 2017 Jan 15;372:331-41; ISRN Neurology. 2012, Article ID 427102. doi: 10.5402/2012/427102).

For the current study, researchers tracked 300 patients at two unidentified MS clinics via their charts over a 2-year period from 2014 to 2016. Their median age was 52 years, 76% were women, and 15 had experienced at least one relapse within the previous 24 months.

“Screening for cognitive impairment and depression was documented for only 52% and 63% of MS patients, respectively, and only about a quarter of patients diagnosed with these conditions were referred to a higher level of care,” said lead author Guy J. Buckle, MD, MPH, of the Andrew C. Carlos MS Institute at Shepherd Center in Atlanta.

Among all 300 patients, just 2% and 4% were screened using a validated tool for cognitive impairment and depression, respectively.

The screening often turned up evidence of the conditions: Physicians saw signs of cognitive impairment in 69% and 78% of those screened aged under 65 years and aged 65 and older, respectively, and they detected depression in 71% and 54% of those screened in those two age groups, respectively.

Researchers also noted several disparities. “Cognitive screening was conducted more frequently in older, employed, or white patients, while the presence of cognitive impairment was documented more often in black, nonworking, and those on Medicare or Medicaid,” Dr. Buckle said. “Depression screening was performed most frequently in older or white patients, yet depression was more common in younger, nonworking patients and those on Medicare/Medicaid.”

In another part of their study, researchers surveyed 13 unidentified “national leaders” in MS research and treatment. Just seven said they used validated tools to screen for cognitive impairment and six said they used them to screen for depression.

“We hear from MS specialists that they want to be measuring for cognition but don’t know how to efficiently work it into their routine, how to approach the patient, and what tools to use,” said study coauthor Derrick S. Robertson, MD, of the University of South Florida, Tampa. “In addition, there is no one tool that is accepted in the MS treatment community.”

MS specialists who didn’t use the screening tests also pointed to factors like lack of reimbursement and lack of integration into electronic medical records. “Doubt very much that neurologists have time to use any of these tests,” one respondent said, referring to cognitive impairment screening.

What’s next? “There are several new exciting developments in clinical trials demonstrating efficacy of disease-modifying therapies in maintaining or improving cognition in patients with relapsing MS,” Dr. Robertson said. “This highlights the urgent need to overcome barriers to use of formal cognitive screening tools in clinical practice to identify patients who need a higher level of care, and perhaps even a change in treatment with the ultimate goal to improve quality of life and overall outcomes.”

Genentech funded the study through an educational grant. Dr. Sapir and three other study authors reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Buckle and Dr. Robertson reported multiple disclosures, including principle investigator and advisory board/panel member work.

SOURCE: Buckle GJ et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2018, abstract No. P161.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2018

Key clinical point: Screening often turns up signs of trouble, but many MS patients are not screened annually for depression and cognitive impairment.

Major finding: 52% and 63% of patients with MS were screened for cognitive impairment and depression, respectively, over a 1-year period. Study details: 2-year analysis of medical records from two MS clinics in the Southeast.

Disclosures: Genentech funded the study through an educational grant. Some of the study authors reported various disclosures.

Source: Buckle GJ et al. ACTRIMS Forum 2018, abstract No. P161.

Prazosin falls short for veterans’ PTSD-related sleep problems

The alpha-1 adrenergic receptor prazosin failed to improve recurring nightmares or sleep quality compared with placebo in veterans with PTSD in a 26-week randomized trial of 304 adult veterans.

In several previous randomized trials lasting fewer than 15 weeks, veterans with PTSD and recurring nightmares who received prazosin showed benefits, including improved sleep quality and PTSD symptoms, compared with placebo patients, wrote Murray A. Raskind, MD, of the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, and his colleagues.

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers randomized 152 veterans with sleep problems and PTSD to prazosin and 152 to a placebo. The participants were recruited from 12 VA medical centers. The average age of the participants was 52 years, more than 96% were male, and about two-thirds were white. Demographics were similar between the two groups.

After 10 weeks and after 26 weeks, there were no significant differences between the two groups in changes from baseline measures of recurring nightmares, using the mean change from baseline in Clinician-Administered PTSD Score item B2 (recurrent distressing dreams). Similarly, no significant differences appeared between the two groups based on Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores.

“A possible explanation for these negative results is selection bias resulting from recruitment of patients who were mainly in clinically stable condition, since symptoms in such patients were less likely to be ameliorated with antiadrenergic treatment,” reported Dr. Raskind and his colleagues.

The average maintenance dose of prazosin was 14.8 mg, compared with 16.4 mg in the placebo group; 187 male study participants reached the maximum dose of 20 mg/day (54% of the prazosin group and 70% of the placebo group).

After 10 weeks, no significant differences were found between the two groups in changes from baseline measures of “recurring distressing dreams,” using the mean change from baseline in Clinician-Administered PTSD Score item B2 (recurrent distressing dreams). The between group difference was 0.2. In addition, no significant differences were found at 10 weeks in the average change from baseline Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores.

Similarly, no significant differences appeared between the two groups at 26 weeks. “ since symptoms in such patients were less likely to be ameliorated with antiadrenergic treatment,” the researchers said.

On average, patients in the prazosin group had significantly greater decreases in blood pressure, compared with the placebo group. In addition, they had fewer reports of new or worsening suicidal ideation, compared with the placebo group (8% vs.15%).

“Given the concern about suicide among veterans, it is noteworthy that the specifically solicited adverse event of new or worsening suicidal ideation was less common in the prazosin group than in the placebo group, but the absolute number of events was small; this issue warrants further study,” the researchers said.

The study was limited by several factors, including the absence of screening for sleep apnea or sleep-disordered breathing, Dr. Raskind and his colleagues noted. However, the results suggest that “further studies with more refined characterization of autonomic nervous system activity and nocturnal behaviors are needed to determine whether there might be subgroups of veterans with PTSD who can benefit from prazosin.”

Dr. Raskind had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program.

SOURCE: Raskind MA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378:507-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507598.

The alpha-1 adrenergic receptor prazosin failed to improve recurring nightmares or sleep quality compared with placebo in veterans with PTSD in a 26-week randomized trial of 304 adult veterans.

In several previous randomized trials lasting fewer than 15 weeks, veterans with PTSD and recurring nightmares who received prazosin showed benefits, including improved sleep quality and PTSD symptoms, compared with placebo patients, wrote Murray A. Raskind, MD, of the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, and his colleagues.

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers randomized 152 veterans with sleep problems and PTSD to prazosin and 152 to a placebo. The participants were recruited from 12 VA medical centers. The average age of the participants was 52 years, more than 96% were male, and about two-thirds were white. Demographics were similar between the two groups.

After 10 weeks and after 26 weeks, there were no significant differences between the two groups in changes from baseline measures of recurring nightmares, using the mean change from baseline in Clinician-Administered PTSD Score item B2 (recurrent distressing dreams). Similarly, no significant differences appeared between the two groups based on Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores.

“A possible explanation for these negative results is selection bias resulting from recruitment of patients who were mainly in clinically stable condition, since symptoms in such patients were less likely to be ameliorated with antiadrenergic treatment,” reported Dr. Raskind and his colleagues.

The average maintenance dose of prazosin was 14.8 mg, compared with 16.4 mg in the placebo group; 187 male study participants reached the maximum dose of 20 mg/day (54% of the prazosin group and 70% of the placebo group).

After 10 weeks, no significant differences were found between the two groups in changes from baseline measures of “recurring distressing dreams,” using the mean change from baseline in Clinician-Administered PTSD Score item B2 (recurrent distressing dreams). The between group difference was 0.2. In addition, no significant differences were found at 10 weeks in the average change from baseline Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores.

Similarly, no significant differences appeared between the two groups at 26 weeks. “ since symptoms in such patients were less likely to be ameliorated with antiadrenergic treatment,” the researchers said.

On average, patients in the prazosin group had significantly greater decreases in blood pressure, compared with the placebo group. In addition, they had fewer reports of new or worsening suicidal ideation, compared with the placebo group (8% vs.15%).

“Given the concern about suicide among veterans, it is noteworthy that the specifically solicited adverse event of new or worsening suicidal ideation was less common in the prazosin group than in the placebo group, but the absolute number of events was small; this issue warrants further study,” the researchers said.

The study was limited by several factors, including the absence of screening for sleep apnea or sleep-disordered breathing, Dr. Raskind and his colleagues noted. However, the results suggest that “further studies with more refined characterization of autonomic nervous system activity and nocturnal behaviors are needed to determine whether there might be subgroups of veterans with PTSD who can benefit from prazosin.”

Dr. Raskind had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program.

SOURCE: Raskind MA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378:507-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507598.

The alpha-1 adrenergic receptor prazosin failed to improve recurring nightmares or sleep quality compared with placebo in veterans with PTSD in a 26-week randomized trial of 304 adult veterans.

In several previous randomized trials lasting fewer than 15 weeks, veterans with PTSD and recurring nightmares who received prazosin showed benefits, including improved sleep quality and PTSD symptoms, compared with placebo patients, wrote Murray A. Raskind, MD, of the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, and his colleagues.

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers randomized 152 veterans with sleep problems and PTSD to prazosin and 152 to a placebo. The participants were recruited from 12 VA medical centers. The average age of the participants was 52 years, more than 96% were male, and about two-thirds were white. Demographics were similar between the two groups.

After 10 weeks and after 26 weeks, there were no significant differences between the two groups in changes from baseline measures of recurring nightmares, using the mean change from baseline in Clinician-Administered PTSD Score item B2 (recurrent distressing dreams). Similarly, no significant differences appeared between the two groups based on Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores.

“A possible explanation for these negative results is selection bias resulting from recruitment of patients who were mainly in clinically stable condition, since symptoms in such patients were less likely to be ameliorated with antiadrenergic treatment,” reported Dr. Raskind and his colleagues.

The average maintenance dose of prazosin was 14.8 mg, compared with 16.4 mg in the placebo group; 187 male study participants reached the maximum dose of 20 mg/day (54% of the prazosin group and 70% of the placebo group).

After 10 weeks, no significant differences were found between the two groups in changes from baseline measures of “recurring distressing dreams,” using the mean change from baseline in Clinician-Administered PTSD Score item B2 (recurrent distressing dreams). The between group difference was 0.2. In addition, no significant differences were found at 10 weeks in the average change from baseline Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores.

Similarly, no significant differences appeared between the two groups at 26 weeks. “ since symptoms in such patients were less likely to be ameliorated with antiadrenergic treatment,” the researchers said.

On average, patients in the prazosin group had significantly greater decreases in blood pressure, compared with the placebo group. In addition, they had fewer reports of new or worsening suicidal ideation, compared with the placebo group (8% vs.15%).

“Given the concern about suicide among veterans, it is noteworthy that the specifically solicited adverse event of new or worsening suicidal ideation was less common in the prazosin group than in the placebo group, but the absolute number of events was small; this issue warrants further study,” the researchers said.

The study was limited by several factors, including the absence of screening for sleep apnea or sleep-disordered breathing, Dr. Raskind and his colleagues noted. However, the results suggest that “further studies with more refined characterization of autonomic nervous system activity and nocturnal behaviors are needed to determine whether there might be subgroups of veterans with PTSD who can benefit from prazosin.”

Dr. Raskind had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program.

SOURCE: Raskind MA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378:507-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507598.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Prazosin had no apparent effect on recurrent distressing dreams or sleep quality in veterans with PTSD.

Major finding: The between-group difference in scores on a measure of “recurrent distressing dreams” between the prazosin and placebo groups was a nonsignificant 0.2.

Study details: The data come from a randomized trial of 304 military veterans with PTSD who reported frequent nightmares.

Disclosures: Dr. Raskind had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program.

Source: Raskind MA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:507-17.

Schizophrenia and gender: Do neurosteroids account for differences?

Neurosteroids may be tied to the gender differences found in the susceptibility to schizophrenia, a cross-sectional, case control study showed.

“These findings suggest that neurosteroids are involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia in male patients but not so much in female patients,” reported Yu-Chi Huang, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, and associates.

To conduct the study, the researchers recruited 65 patients with schizophrenia from an outpatient department and psychiatry ward of the hospital. Eligible patients were aged 18-65 years, diagnosed with schizophrenia as defined by the DSM-IV-TR, and taking a stable dose of antipsychotics for at least 1 month before the start of the study. In addition, the participants could have no history of major physical illnesses and had to be of ethnic Han Chinese origin. Thirty-six of the patients were men.

The control group was made up of 103 healthy hospital staff and community members who were within the same age range as the patients. The controls could have no history of illicit drug use, physical illnesses, or psychiatric disorders and had to be ethnic Han Chinese. Forty-seven members of the control group were males (Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017 Oct;84:87-93).

Participants fasted and blood samples were obtained. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels were measured using the DHEA ELISA [enyme-linked immunosorbent assay] – ADKI-900-093, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels were measured with the Architect DHEA-S reagent kit, and pregnenolone levels were measured using the pregnenolone ELISA kit. Psychiatric diagnoses were assessed for both groups using a psychiatric interview based on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Several factors tied to schizophrenia were evaluated, including the age of onset, illness duration, and use of antipsychotics. The numbers were placed into a database and analyzed.

After controlling for age and body mass index, the researchers found that in male patients with schizophrenia, DHEA and DHEAS serum levels were positively associated with the age of onset of schizophrenia (P less than .05) and negatively associated with the duration of illness (P less than .05). (P less than .05 ). Furthermore, the levels of DHEA, DHEAS, and pregnenolone were lower among the male schizophrenia patients, compared with the serum levels of the healthy male controls. No differences were found in serum levels among the female patients with schizophrenia and the healthy controls.

The findings suggest that DHEA, DHEAS, and pregnenolone could be markers of the duration of illness and the severity of general symptoms among male patients with schizophrenia. To read the entire study, click here.

Neurosteroids may be tied to the gender differences found in the susceptibility to schizophrenia, a cross-sectional, case control study showed.

“These findings suggest that neurosteroids are involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia in male patients but not so much in female patients,” reported Yu-Chi Huang, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, and associates.

To conduct the study, the researchers recruited 65 patients with schizophrenia from an outpatient department and psychiatry ward of the hospital. Eligible patients were aged 18-65 years, diagnosed with schizophrenia as defined by the DSM-IV-TR, and taking a stable dose of antipsychotics for at least 1 month before the start of the study. In addition, the participants could have no history of major physical illnesses and had to be of ethnic Han Chinese origin. Thirty-six of the patients were men.

The control group was made up of 103 healthy hospital staff and community members who were within the same age range as the patients. The controls could have no history of illicit drug use, physical illnesses, or psychiatric disorders and had to be ethnic Han Chinese. Forty-seven members of the control group were males (Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017 Oct;84:87-93).

Participants fasted and blood samples were obtained. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels were measured using the DHEA ELISA [enyme-linked immunosorbent assay] – ADKI-900-093, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels were measured with the Architect DHEA-S reagent kit, and pregnenolone levels were measured using the pregnenolone ELISA kit. Psychiatric diagnoses were assessed for both groups using a psychiatric interview based on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Several factors tied to schizophrenia were evaluated, including the age of onset, illness duration, and use of antipsychotics. The numbers were placed into a database and analyzed.

After controlling for age and body mass index, the researchers found that in male patients with schizophrenia, DHEA and DHEAS serum levels were positively associated with the age of onset of schizophrenia (P less than .05) and negatively associated with the duration of illness (P less than .05). (P less than .05 ). Furthermore, the levels of DHEA, DHEAS, and pregnenolone were lower among the male schizophrenia patients, compared with the serum levels of the healthy male controls. No differences were found in serum levels among the female patients with schizophrenia and the healthy controls.

The findings suggest that DHEA, DHEAS, and pregnenolone could be markers of the duration of illness and the severity of general symptoms among male patients with schizophrenia. To read the entire study, click here.

Neurosteroids may be tied to the gender differences found in the susceptibility to schizophrenia, a cross-sectional, case control study showed.

“These findings suggest that neurosteroids are involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia in male patients but not so much in female patients,” reported Yu-Chi Huang, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, and associates.

To conduct the study, the researchers recruited 65 patients with schizophrenia from an outpatient department and psychiatry ward of the hospital. Eligible patients were aged 18-65 years, diagnosed with schizophrenia as defined by the DSM-IV-TR, and taking a stable dose of antipsychotics for at least 1 month before the start of the study. In addition, the participants could have no history of major physical illnesses and had to be of ethnic Han Chinese origin. Thirty-six of the patients were men.

The control group was made up of 103 healthy hospital staff and community members who were within the same age range as the patients. The controls could have no history of illicit drug use, physical illnesses, or psychiatric disorders and had to be ethnic Han Chinese. Forty-seven members of the control group were males (Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017 Oct;84:87-93).

Participants fasted and blood samples were obtained. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels were measured using the DHEA ELISA [enyme-linked immunosorbent assay] – ADKI-900-093, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels were measured with the Architect DHEA-S reagent kit, and pregnenolone levels were measured using the pregnenolone ELISA kit. Psychiatric diagnoses were assessed for both groups using a psychiatric interview based on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Several factors tied to schizophrenia were evaluated, including the age of onset, illness duration, and use of antipsychotics. The numbers were placed into a database and analyzed.

After controlling for age and body mass index, the researchers found that in male patients with schizophrenia, DHEA and DHEAS serum levels were positively associated with the age of onset of schizophrenia (P less than .05) and negatively associated with the duration of illness (P less than .05). (P less than .05 ). Furthermore, the levels of DHEA, DHEAS, and pregnenolone were lower among the male schizophrenia patients, compared with the serum levels of the healthy male controls. No differences were found in serum levels among the female patients with schizophrenia and the healthy controls.

The findings suggest that DHEA, DHEAS, and pregnenolone could be markers of the duration of illness and the severity of general symptoms among male patients with schizophrenia. To read the entire study, click here.

FROM PSYCHONEUROENDOCRINOLOGY

Benzodiazepines: Sensible prescribing in light of the risks

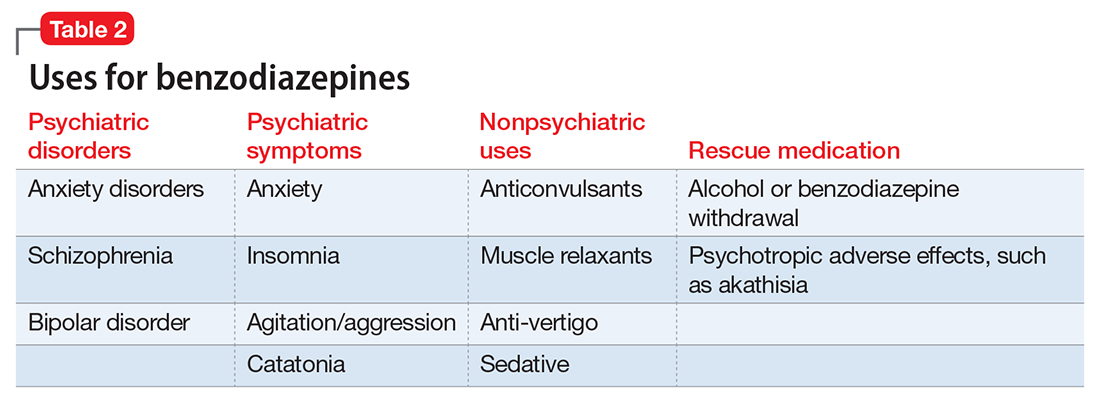

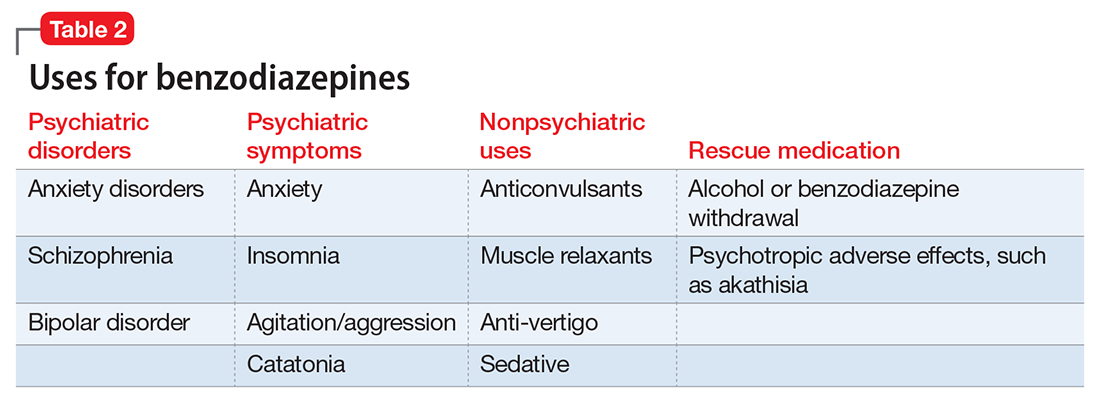

As a group, anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the Unites States, affecting 40 million adults. There is a nearly 30% lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in the general population.1 DSM-5 anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), panic disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. Although DSM-IV-TR also classified obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as anxiety disorders, these diagnoses were reclassified in DSM-5. Anxiety also is a frequent symptom of many other psychiatric disorders, especially major depressive disorder.

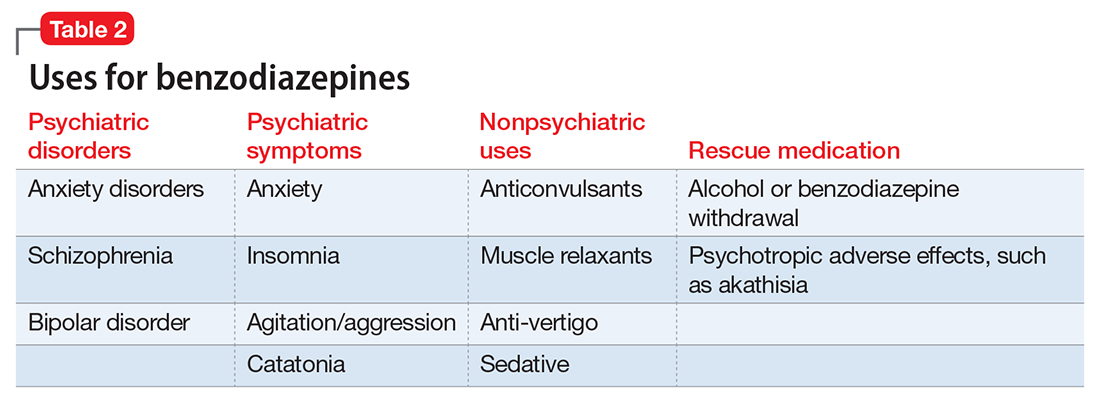

Although benzodiazepines have many potential uses, they also carry risks that prescribers should recognize. This article reviews some of the risks of benzodiazepine use, identifies patients with higher risks of adverse effects, and presents a practical approach to prescribing these medications.

A wide range of risks

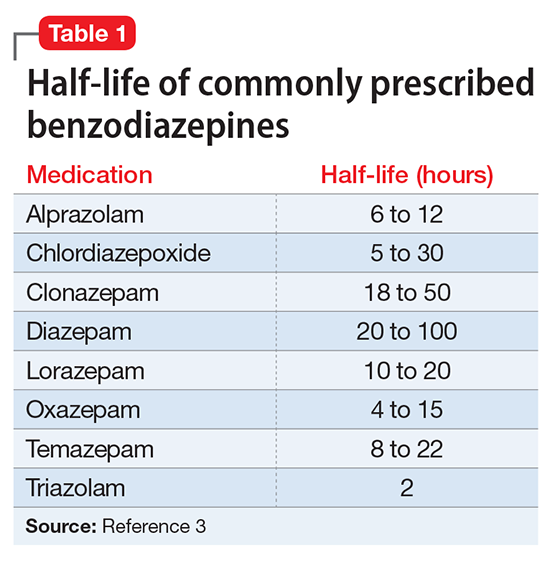

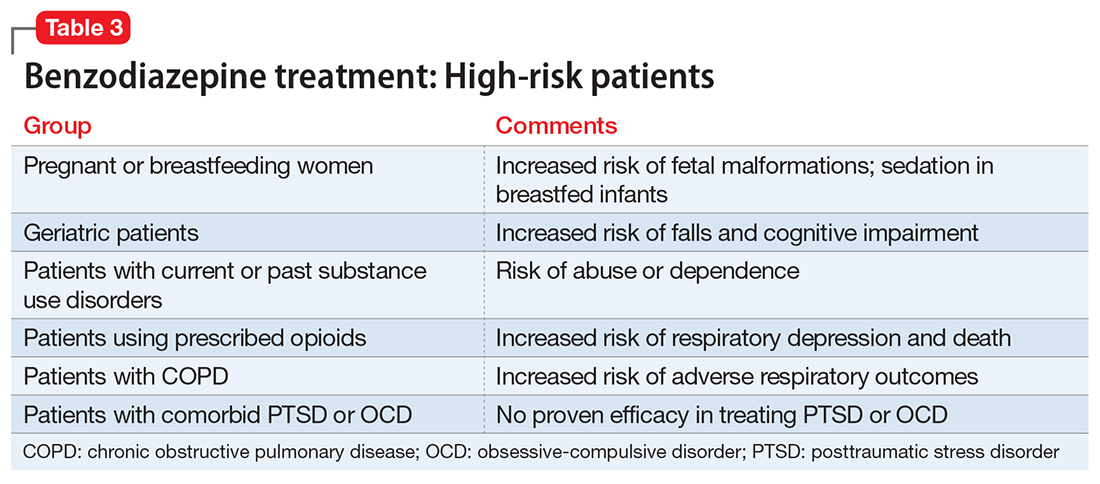

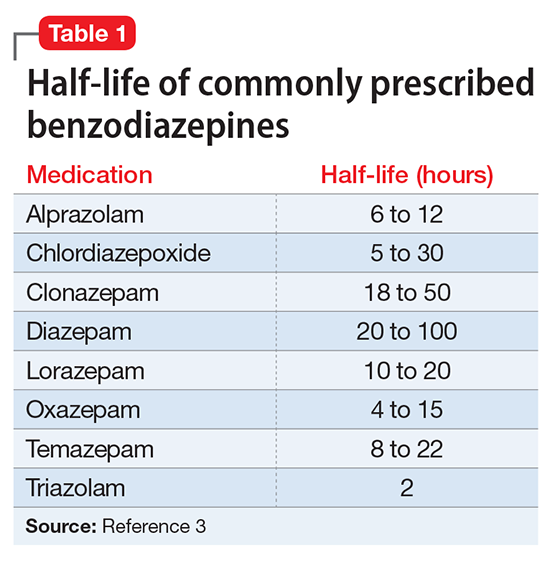

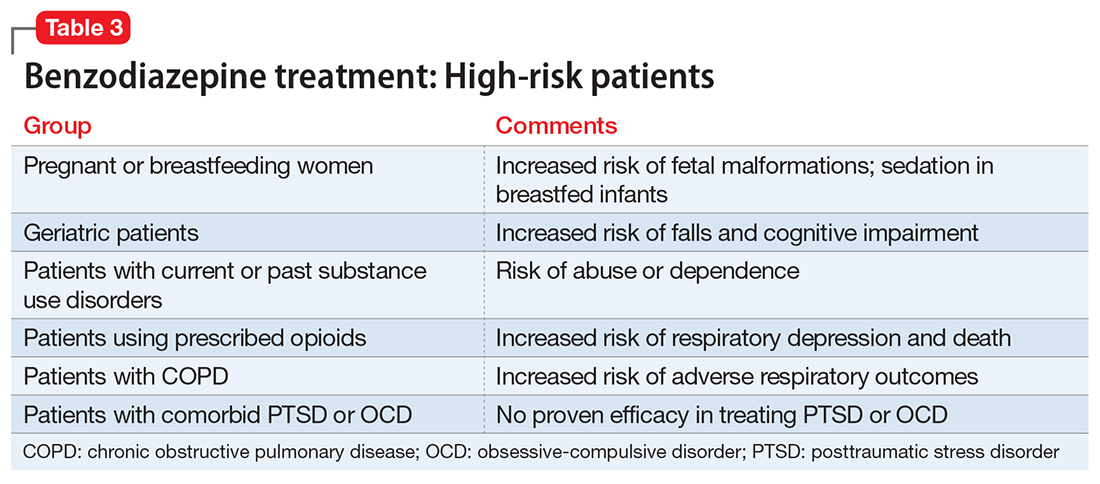

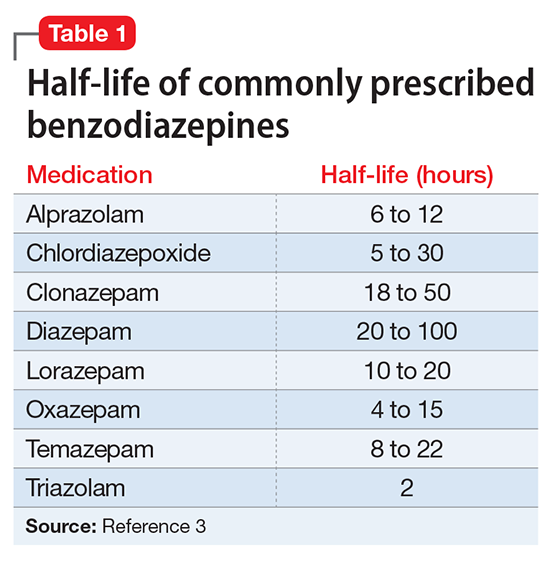

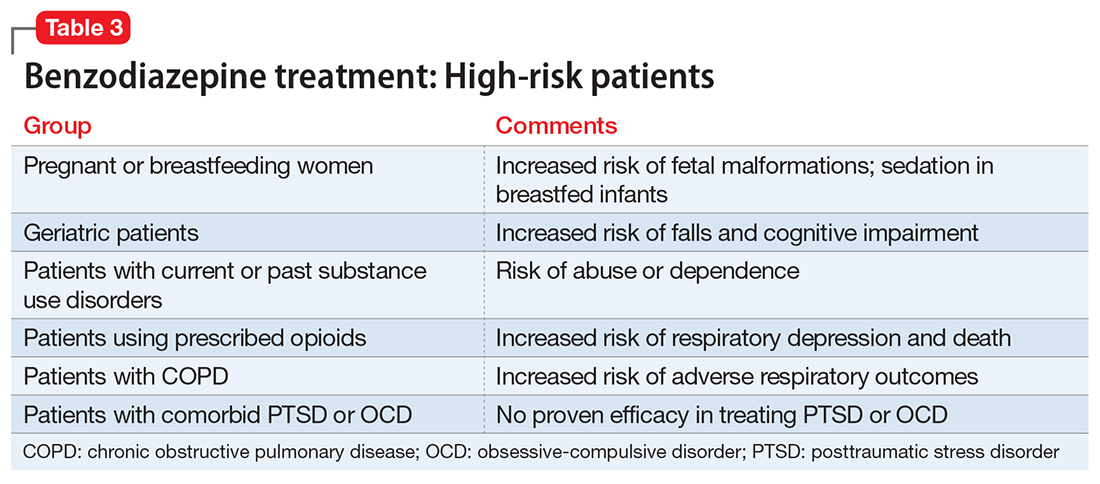

Abuse and addiction. Perhaps the most commonly recognized risk associated with benzodiazepine use is the potential for abuse and addiction.4 Prolonged benzodiazepine use typically results in physiologic tolerance, requiring higher dosing to achieve the same initial effect.5 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recognize the potential for benzodiazepine use to result in symptoms of dependence, including cravings and withdrawal, stating that “with ongoing use, all benzodiazepines will produce physiological dependence in most patients.”6 High-potency, short-acting compounds such as alprazolam have a higher risk for dependence, toxicity, and abuse.7 However, long-acting benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) also can be habit-forming.8 Because of these properties, it is generally advisable to avoid prescribing benzodiazepines (and short-acting compounds in particular) when treating patients with current or past substance use disorders, except when treating withdrawal.9

Limited efficacy for other disorders. Although benzodiazepines can help reduce anxiety in patients with anxiety disorders, they have shown less promise in treating other disorders in which anxiety is a common symptom. Treating PTSD with benzodiazepines does not appear to offer any advantage over placebo, and may even result in increased symptoms over time.10,11 There is limited evidence supporting the use of benzodiazepines to treat OCD.12,13 Patients with borderline personality disorder who are treated with benzodiazepines may experience an increase in behavioral dysregulation.14

Physical ailments. Benzodiazepines can affect comorbid physical ailments. One study found that long-term benzodiazepine use among patients with comorbid pain disorders was correlated with high utilization of medical services and high disability levels.15 Benzodiazepine use also has been associated with an increased risk of exacerbating respiratory conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,16 and increased risk of pneumonia.17,18

Pregnancy and breastfeeding. Benzodiazepines carry risks for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Benzodiazepine use during pregnancy may increase the relative risk of major malformations and oral clefts. It also may result in neonatal lethargy, sedation, and weight loss. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can occur in the neonate.19 Benzodiazepines are secreted in breast milk and can result in sedation among breastfed infants.20

Geriatric patients. Older adults may be particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults recommends against prescribing benzodiazepines to geriatric patients.21 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with an increased risk for falls among older adults,22,23 with an increased risk of fractures24 that can be fatal.25 Benzodiazepines also have been associated with an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and dementia.26,27 Despite the documented risks of using benzodiazepines in geriatric patients, benzodiazepines continue to be frequently prescribed to this age group.28,29 One study found that the rate of prescribing benzodiazepines by primary care physicians increased from 2003 to 2012, primarily among older adults with no diagnosis of pain or a psychiatric disorder.30

Mortality. Benzodiazepine use also carries an increased risk of mortality. Benzodiazepine users are at increased risk of motor vehicle accidents because of difficulty maintaining road position.31 Some research has shown that patients with schizophrenia treated with benzodiazepines have an increased risk of death compared with those who are prescribed antipsychotics or antidepressants.32 Another study showed that patients with schizophrenia who were prescribed benzodiazepines had a greater risk of death by suicide and accidental poisoning.33 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with suicidal ideation and an increased risk of suicide.34 Prescription opioids and benzodiazepines are the top 2 causes of overdose-related deaths (benzodiazepines are involved in approximately 31% of fatal overdoses35), and from 2002 to 2015 there was a 4.3-fold increase in deaths from benzodiazepine overdose in the United States.36 CDC guidelines recommend against co-prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines because of the risk of death by respiratory depression.37 As of August 2016, the FDA required black-box warnings for opioids and benzodiazepines regarding the risk of respiratory depression and death when these agents are used in combination, noting that “If these medicines are prescribed together, limit the dosages and duration of each drug to the minimum possible while achieving the desired clinical effect.”38,39

A sensible approach to prescribing

Given the risks posed by benzodiazepines, what would constitute a sensible approach to their use? Clearly, there are some patients for whom benzodiazepine use should be minimized or avoided (Table 3). In a patient who is deemed a good candidate for benzodiazepines, a long-acting agent may be preferable because of the increased risk of dependence associated with short-acting compounds. Start with a low dose, and use the lowest dose that adequately treats the patient’s symptoms.40 Using scheduled rather than “as-needed” dosing may help reduce behavioral escape patterns that reinforce anxiety and dependence in the long term.

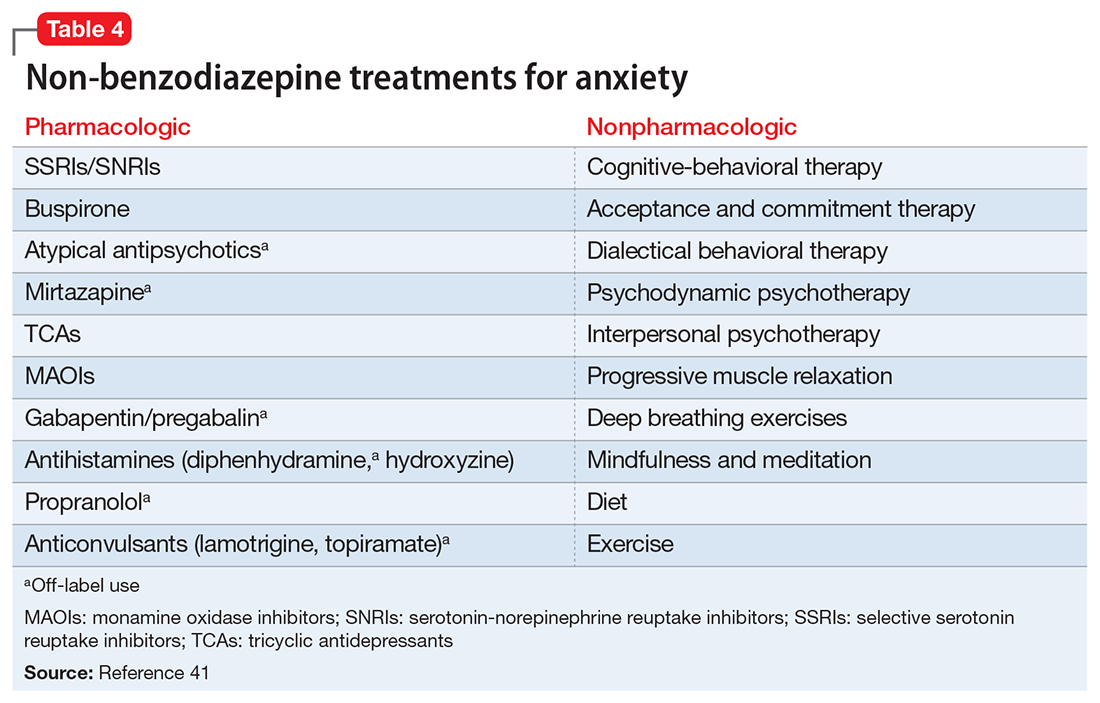

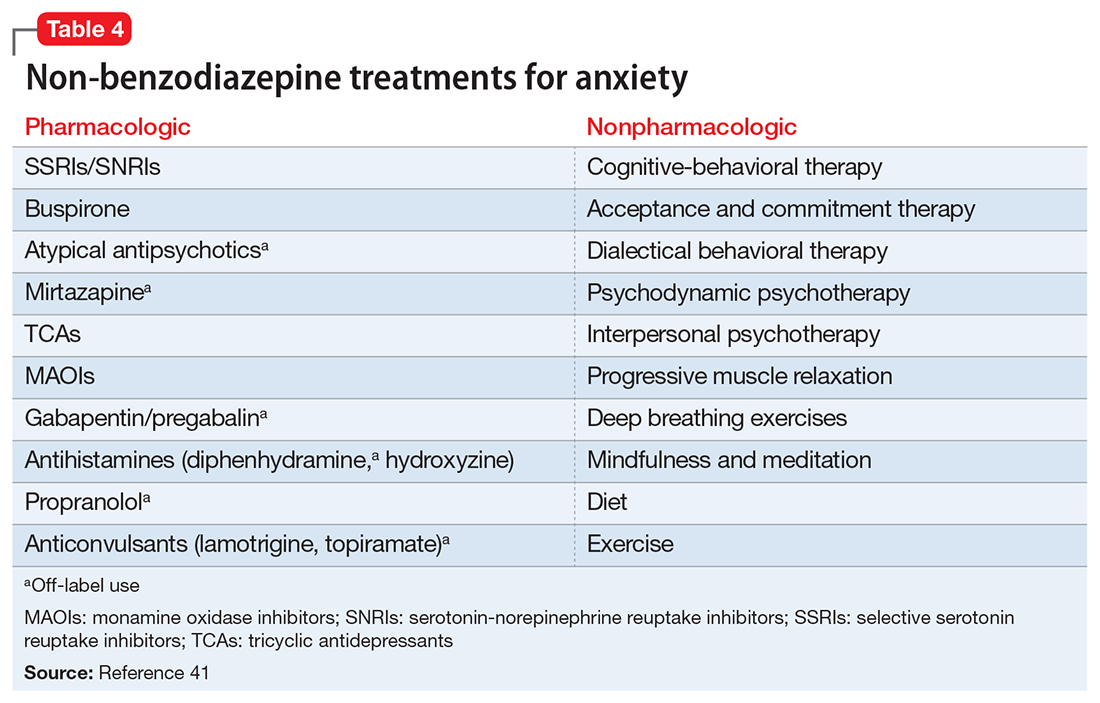

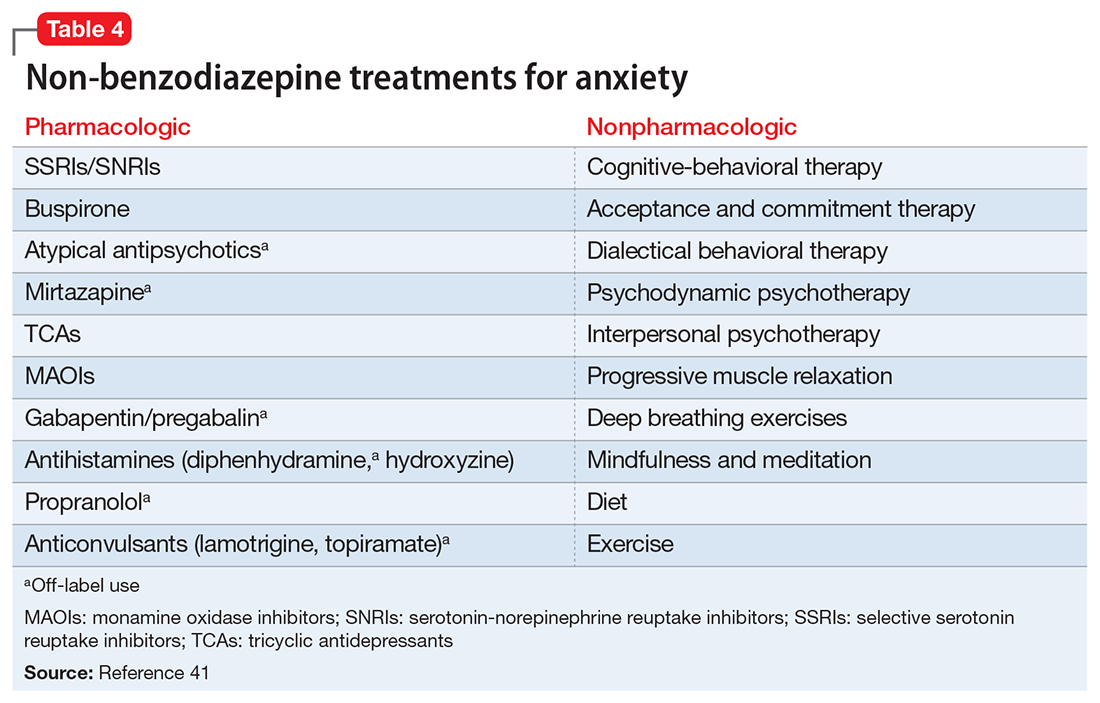

Before starting a patient on a benzodiazepine, discuss with him (her) the risks of use and an exit plan to discontinue the medication. For example, a benzodiazepine may be prescribed at the same time as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), with the goal of weaning off the benzodiazepine once the SSRI has achieved efficacy.6 Inform the patient that prescribing or treatment may be terminated if it is discovered that the patient is abusing or diverting the medication (regularly reviewing the state prescription monitoring program database can help determine if this has occurred). Strongly consider using non-benzodiazepine treatments for anxiety with (or eventually in place of) benzodiazepines (Table 441).

Reducing or stopping benzodiazepines can be challenging.42 Patients often are reluctant to stop such medications, and abrupt cessation can cause severe withdrawal. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can be severe or even fatal. Therefore, a safe and collaborative approach to reducing or stopping benzodiazepines is necessary. A starting point might be to review the risks associated with benzodiazepine use with the patient and ask about the frequency of use. Discuss with the patient a slow taper, perhaps reducing the dose by 10% to 25% increments weekly to biweekly.43,44 Less motivated patients may require a slower taper, more time, or repeated discussions. When starting a dose reduction, notify the patient that some rebound anxiety or insomnia are to be expected. With any progress the patient makes toward reducing his usage, congratulate him on such progress.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Balon R, Fava GA, Rickels K. Need for a realistic appraisal of benzodiazepines. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):243-244.

3. Ashton CH. Benzodiazepine equivalence table. http://www.benzo.org.uk/bzequiv.htm. Revised April 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Commonly abused drugs. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/commonly_abused_drugs_3.pdf. Revised January 2016. Accessed January 9, 2018.

5. Licata SC, Rowlett JK. Abuse and dependence liability of benzodiazepine-type drugs: GABA(A) receptor modulation and beyond. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90(1):74-89.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, second edition. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed May 3, 2017.

7. Salzman C. The APA Task Force report on benzodiazepine dependence, toxicity, and abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(2):151-152.

8. Bushnell GA, Stürmer T, Gaynes BN, et al. Simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use and subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in adults with depression, United States, 2001-2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):747-755.

9. O’Brien PL, Karnell LH, Gokhale M, et al. Prescribing of benzodiazepines and opioids to individuals with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:223-230.

10. Mellman TA, Bustamante V, David D, et al. Hypnotic medication in the aftermath of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1183-1184.

11. Gelpin E, Bonne O, Peri T, et al. Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(9):390-394.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd.pdf. Published July 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

13. Abdel-Ahad P, Kazour F. Non-antidepressant pharmacological treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a comprehensive review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10(2):97-111.

14. Gardner DL, Cowdry RW. Alprazolam-induced dyscontrol in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(1):98-100.

15. Ciccone DS, Just N, Bandilla EB, et al. Psychological correlates of opioid use in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain: a preliminary test of the downhill spiral hypothesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(3):180-192.

16. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

17. Obiora E, Hubbard R, Sanders RD, et al. The impact of benzodiazepines on occurrence of pneumonia and mortality from pneumonia: a nested case-control and survival analysis in a population-based cohort. Thorax. 2013;68(2):163-170.

18. Taipale H, Tolppanen AM, Koponen M, et al. Risk of pneumonia associated with incident benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling adults with Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2017;189(14):E519-E529.

19. Iqbal MM, Sobhan T, Ryals T. Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant. Psychiatric Serv. 2002;53:39-49.

20. U.S. National Library of Medicine, TOXNET Toxicology Data Network. Lactmed: alprazolam. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search2/r?dbs+lactmed:@term+@DOCNO+335. Accessed May 3, 2017.

21. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

22. Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falls in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):682-685.

23. Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952-1960.

24. Bolton JM, Morin SN, Majumdar SR, et al. Association of mental disorders and related medication use with risk for major osteoporotic fractures. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):641-648.

25. Pariente A, Dartiques JF, Benichou J, et al. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(1):61-70.

26. Lagnaoui R, Tournier M, Moride Y, et al. The risk of cognitive impairment in older community-dwelling women after benzodiazepine use. Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):226-228.