User login

A new

The authors reported that – with an average of five quarters postacquisition – there was no statistically significant differential between investor-owned and non–investor-owned practices “in total spending, overall use of dermatology procedures per patient, or specific high-volume and profitable procedures.”

Essentially, the study findings were equivocal, reported Robert Tyler Braun, PhD and his colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. “The results provide mixed support for both proponents and opponents of private equity acquisitions,” they wrote in the study, which was published in Health Affairs.

But two dermatologists not involved with the study said the analysis has significant limitations, including a lack of pathology data, a lack of Medicare data, and a lack of insight into how advanced practice clinicians, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, were used by the private equity (PE)–owned practices. The study was not able to track “incident to billing.”

Leaving out Medicare data is a “huge oversight,” Joseph K. Francis, MD, a Mohs surgeon at the University of Florida, Gainesville, said in an interview. “The study is fundamentally flawed.”

“With all of these limitations, it’s difficult to draw meaningful conclusions,” agreed Clifford Perlis, MD, Mbe, of Keystone Dermatology in King of Prussia, Pa.

Both Dr. Francis and Dr. Perlis also questioned the influence of one of the study’s primary sponsors, the Physicians Foundation, formed out of the settlement of a class action lawsuit against third-party payers.

In addition, Dr. Francis and Dr. Perlis said they thought the study did not follow the PE-owned practices for a long enough period of time after acquisition to detect any differences, and that the dataset – looking at practice acquisitions from 2012 to 2017 – was too old to paint a reliable picture of the current state of PE-owned practices. Acquisitions have accelerated since 2017.

In March 2021, Harvard researchers reported in JAMA Health Forum that PE purchases in health care peaked in the first quarter of 2018 and surged to almost as high a level in the fourth quarter of 2020, with 153 deals announced in the second half of the year. Of the 153 acquisitions, 98, or 64%, were for physician practices or other health care services.

Dr. Braun said his study focused on 2012-2017 because it was an available data set. And, he defended the snapshot, saying that he and his colleagues had as much as 4 years of postacquisition data for the practices that were purchased in 2013. He acknowledged there were less data on practices purchased from 2014 to 2016.

“It is possible that our results would change with a longer postacquisition period,” Dr. Braun said in an interview. But, he said there was no way to predict whether that change “would look better or worse for private equity.”

Modest price increases

The authors analyzed data from the Health Care Cost Institute, which aggregates claims for some 50 million individuals insured by Aetna, Humana, and United Healthcare. The data do not include Medicare claims.

They examined dermatologists in practices bought between 2013 and 2016 and compared them to dermatologists who were in practices not owned by private equity. Each dermatologist had to have at least 2 years of data, and the authors compared preacquisition with postacquisition data for those in PE-owned practices.

They identified 64 practices – with 246 dermatologists – bought by private investors. Preacquisition, PE practices were larger than non-PE practices, with 4.2 clinicians (including advanced practitioners) per practice, compared with 1.7 in non–investor-owned practices.

The authors looked at volume and prices for routine office visits (CPT code 99213), biopsies (11101), excisions (11602), destruction of first lesion (cryotherapy; 17000), and Mohs micrographic surgery (17311).

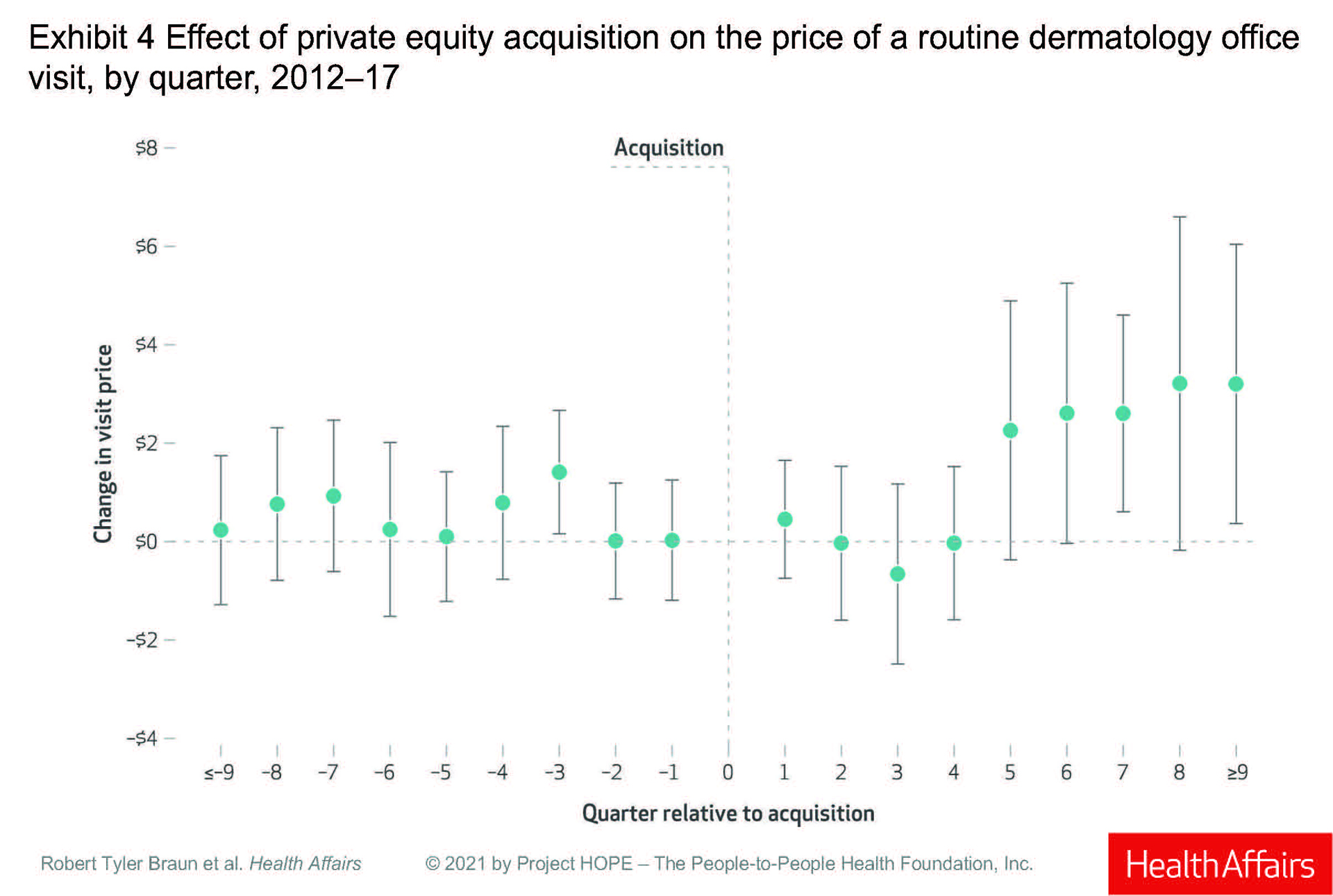

Prices for a routine office visit rose nominally in the first quarter after acquisition (under $1), stayed at 0 in the second quarter, decreased in the third quarter, and was 0 again in the fourth quarter. It was not until the fifth quarter post acquisition that prices rose, increasing by 3% ($2.26), and then rising 5% ($3.20) in the ninth quarter.

Dr. Braun said the price increases make sense because practices get “rolled up” into larger platforms, theoretically giving them more negotiating leverage with insurers. And he said the paper’s results “are consistent with physician practice consolidation research – mainly hospitals acquiring practices – that prices increase after acquisition.” He acknowledged that the dermatology paper found “more modest effects,” than other studies.

Dr. Francis, however, said the increases are basically “pocket change,” and that they reflect a failed promise from private investors that clinicians in PE-owned practices will be paid more. The small differences in pay may also mean that insurers are likely not acquiescing to the theoretical leverage of larger dermatology entities.

PE-owned dermatologists saw about 5% more patients per quarter initially, rising to 17% more per quarter by eight quarters after purchase, according to the study.

The study reported a significant increase in Mohs surgery and cryotherapy in the first quarter post purchase, and a significant increase in biopsies after eight quarters. But Dr. Braun and colleagues concluded that total spending per patient did not change significantly after acquisition. “That says that maybe physicians aren’t changing their behaviors that much,” Dr. Braun said in an interview.

Dr. Perlis disagreed, noting that practices rarely change quickly. “Anecdotally, most groups that are taken over, nothing changes initially,” while the new owners are getting a feel for the practice.

He also said the paper erred in not addressing quality of and access to care. “Quality and patient satisfaction and access are also other important factors that need to be examined.”

Not benign players

Both Dr. Perlis and Dr. Francis said the study may have been improved by having a dermatologist as a coauthor. Dr. Braun countered that he and his colleagues consulted several dermatologists during the course of the study, and that they also conducted 30 interviews with proponents and opponents of PE ownership.

The authors warned of what they viewed as some disturbing trends in PE-owned practices, including what Dr. Braun called “stealth” consolidation – investors making small purchases that fall outside of federal regulation, and then amassing them into large entities.

He also commented that it was “alarming” that PE-owned practices were hiring a larger number of advanced practitioners. The authors also expressed concern about leveraged buyouts, in which investors require a practice to carry high debt loads that can eventually drive it into bankruptcy.

“These are not benign players,” said Dr. Francis. He noted that it took “an act of Congress to stop surprise billing,” a tactic employed by PE-owned health care entities. “Policy makers should be looking at what’s best for patients, especially Medicare and vulnerable patients.”

Dr. Perlis also has qualms about PE-owned practices. “The money to support returns to investors has to come from somewhere and that creates an inherent tension between patient care and optimizing revenue for investors,” he said. “It’s a pretty head-on conflict.”

A new

The authors reported that – with an average of five quarters postacquisition – there was no statistically significant differential between investor-owned and non–investor-owned practices “in total spending, overall use of dermatology procedures per patient, or specific high-volume and profitable procedures.”

Essentially, the study findings were equivocal, reported Robert Tyler Braun, PhD and his colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. “The results provide mixed support for both proponents and opponents of private equity acquisitions,” they wrote in the study, which was published in Health Affairs.

But two dermatologists not involved with the study said the analysis has significant limitations, including a lack of pathology data, a lack of Medicare data, and a lack of insight into how advanced practice clinicians, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, were used by the private equity (PE)–owned practices. The study was not able to track “incident to billing.”

Leaving out Medicare data is a “huge oversight,” Joseph K. Francis, MD, a Mohs surgeon at the University of Florida, Gainesville, said in an interview. “The study is fundamentally flawed.”

“With all of these limitations, it’s difficult to draw meaningful conclusions,” agreed Clifford Perlis, MD, Mbe, of Keystone Dermatology in King of Prussia, Pa.

Both Dr. Francis and Dr. Perlis also questioned the influence of one of the study’s primary sponsors, the Physicians Foundation, formed out of the settlement of a class action lawsuit against third-party payers.

In addition, Dr. Francis and Dr. Perlis said they thought the study did not follow the PE-owned practices for a long enough period of time after acquisition to detect any differences, and that the dataset – looking at practice acquisitions from 2012 to 2017 – was too old to paint a reliable picture of the current state of PE-owned practices. Acquisitions have accelerated since 2017.

In March 2021, Harvard researchers reported in JAMA Health Forum that PE purchases in health care peaked in the first quarter of 2018 and surged to almost as high a level in the fourth quarter of 2020, with 153 deals announced in the second half of the year. Of the 153 acquisitions, 98, or 64%, were for physician practices or other health care services.

Dr. Braun said his study focused on 2012-2017 because it was an available data set. And, he defended the snapshot, saying that he and his colleagues had as much as 4 years of postacquisition data for the practices that were purchased in 2013. He acknowledged there were less data on practices purchased from 2014 to 2016.

“It is possible that our results would change with a longer postacquisition period,” Dr. Braun said in an interview. But, he said there was no way to predict whether that change “would look better or worse for private equity.”

Modest price increases

The authors analyzed data from the Health Care Cost Institute, which aggregates claims for some 50 million individuals insured by Aetna, Humana, and United Healthcare. The data do not include Medicare claims.

They examined dermatologists in practices bought between 2013 and 2016 and compared them to dermatologists who were in practices not owned by private equity. Each dermatologist had to have at least 2 years of data, and the authors compared preacquisition with postacquisition data for those in PE-owned practices.

They identified 64 practices – with 246 dermatologists – bought by private investors. Preacquisition, PE practices were larger than non-PE practices, with 4.2 clinicians (including advanced practitioners) per practice, compared with 1.7 in non–investor-owned practices.

The authors looked at volume and prices for routine office visits (CPT code 99213), biopsies (11101), excisions (11602), destruction of first lesion (cryotherapy; 17000), and Mohs micrographic surgery (17311).

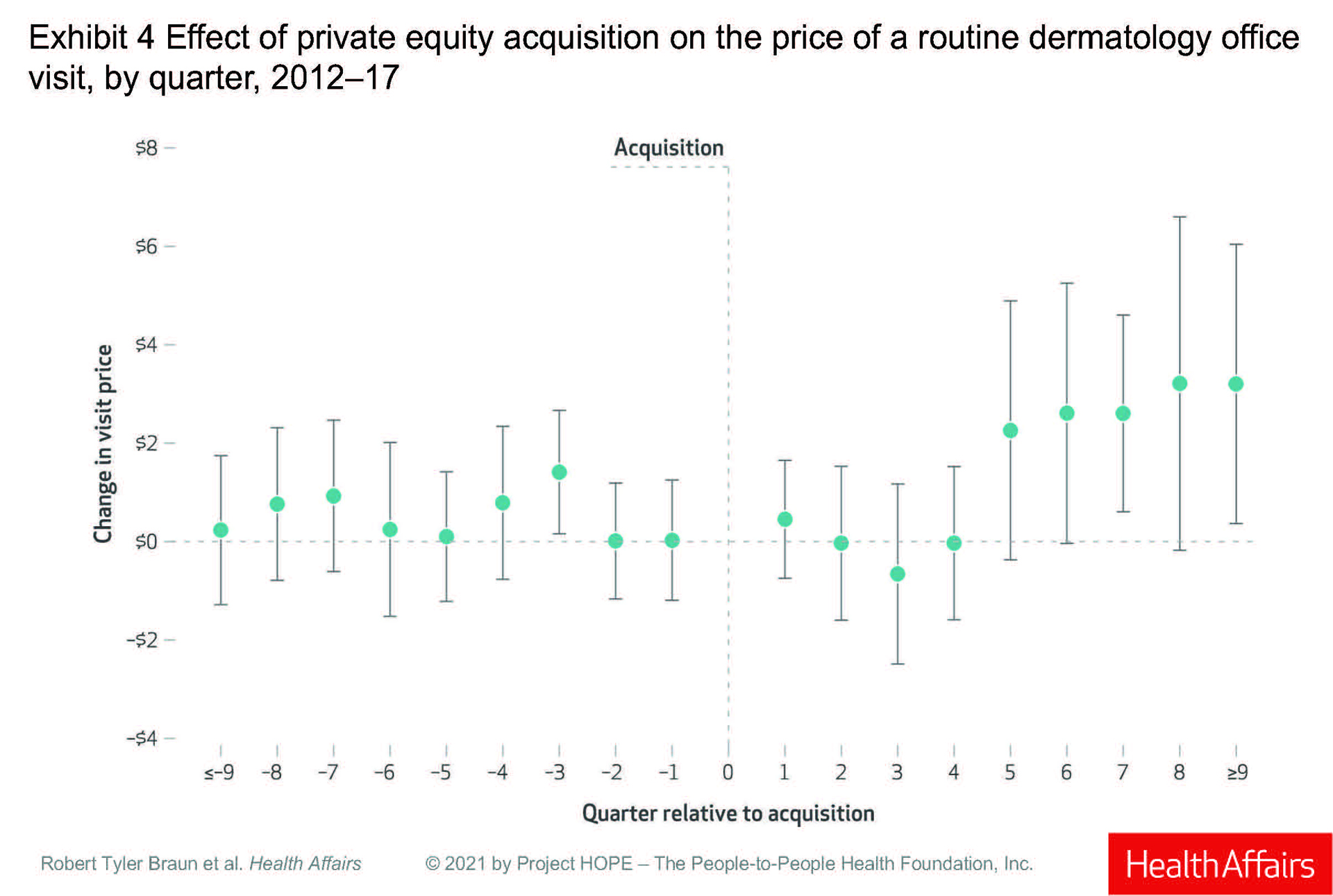

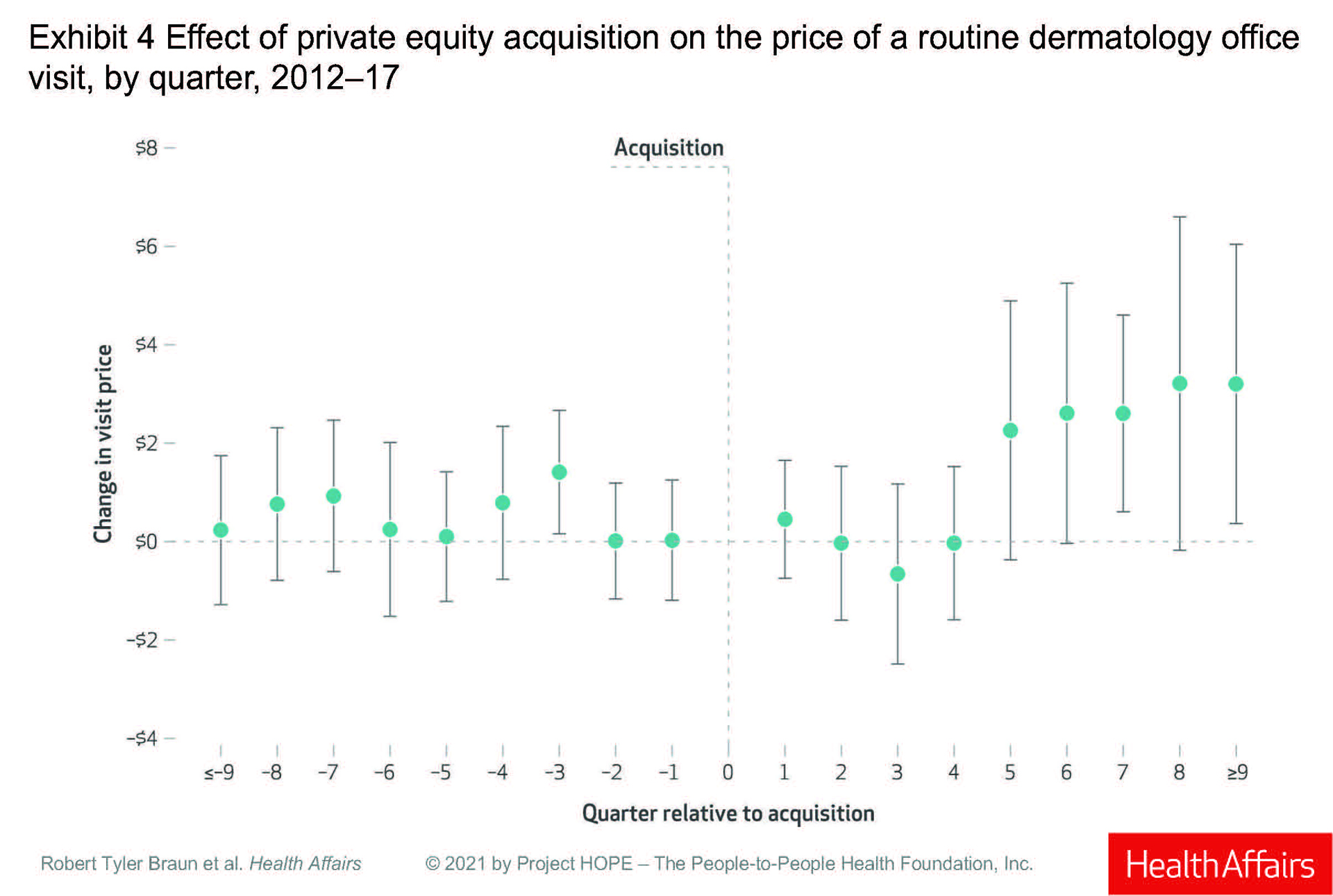

Prices for a routine office visit rose nominally in the first quarter after acquisition (under $1), stayed at 0 in the second quarter, decreased in the third quarter, and was 0 again in the fourth quarter. It was not until the fifth quarter post acquisition that prices rose, increasing by 3% ($2.26), and then rising 5% ($3.20) in the ninth quarter.

Dr. Braun said the price increases make sense because practices get “rolled up” into larger platforms, theoretically giving them more negotiating leverage with insurers. And he said the paper’s results “are consistent with physician practice consolidation research – mainly hospitals acquiring practices – that prices increase after acquisition.” He acknowledged that the dermatology paper found “more modest effects,” than other studies.

Dr. Francis, however, said the increases are basically “pocket change,” and that they reflect a failed promise from private investors that clinicians in PE-owned practices will be paid more. The small differences in pay may also mean that insurers are likely not acquiescing to the theoretical leverage of larger dermatology entities.

PE-owned dermatologists saw about 5% more patients per quarter initially, rising to 17% more per quarter by eight quarters after purchase, according to the study.

The study reported a significant increase in Mohs surgery and cryotherapy in the first quarter post purchase, and a significant increase in biopsies after eight quarters. But Dr. Braun and colleagues concluded that total spending per patient did not change significantly after acquisition. “That says that maybe physicians aren’t changing their behaviors that much,” Dr. Braun said in an interview.

Dr. Perlis disagreed, noting that practices rarely change quickly. “Anecdotally, most groups that are taken over, nothing changes initially,” while the new owners are getting a feel for the practice.

He also said the paper erred in not addressing quality of and access to care. “Quality and patient satisfaction and access are also other important factors that need to be examined.”

Not benign players

Both Dr. Perlis and Dr. Francis said the study may have been improved by having a dermatologist as a coauthor. Dr. Braun countered that he and his colleagues consulted several dermatologists during the course of the study, and that they also conducted 30 interviews with proponents and opponents of PE ownership.

The authors warned of what they viewed as some disturbing trends in PE-owned practices, including what Dr. Braun called “stealth” consolidation – investors making small purchases that fall outside of federal regulation, and then amassing them into large entities.

He also commented that it was “alarming” that PE-owned practices were hiring a larger number of advanced practitioners. The authors also expressed concern about leveraged buyouts, in which investors require a practice to carry high debt loads that can eventually drive it into bankruptcy.

“These are not benign players,” said Dr. Francis. He noted that it took “an act of Congress to stop surprise billing,” a tactic employed by PE-owned health care entities. “Policy makers should be looking at what’s best for patients, especially Medicare and vulnerable patients.”

Dr. Perlis also has qualms about PE-owned practices. “The money to support returns to investors has to come from somewhere and that creates an inherent tension between patient care and optimizing revenue for investors,” he said. “It’s a pretty head-on conflict.”

A new

The authors reported that – with an average of five quarters postacquisition – there was no statistically significant differential between investor-owned and non–investor-owned practices “in total spending, overall use of dermatology procedures per patient, or specific high-volume and profitable procedures.”

Essentially, the study findings were equivocal, reported Robert Tyler Braun, PhD and his colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. “The results provide mixed support for both proponents and opponents of private equity acquisitions,” they wrote in the study, which was published in Health Affairs.

But two dermatologists not involved with the study said the analysis has significant limitations, including a lack of pathology data, a lack of Medicare data, and a lack of insight into how advanced practice clinicians, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, were used by the private equity (PE)–owned practices. The study was not able to track “incident to billing.”

Leaving out Medicare data is a “huge oversight,” Joseph K. Francis, MD, a Mohs surgeon at the University of Florida, Gainesville, said in an interview. “The study is fundamentally flawed.”

“With all of these limitations, it’s difficult to draw meaningful conclusions,” agreed Clifford Perlis, MD, Mbe, of Keystone Dermatology in King of Prussia, Pa.

Both Dr. Francis and Dr. Perlis also questioned the influence of one of the study’s primary sponsors, the Physicians Foundation, formed out of the settlement of a class action lawsuit against third-party payers.

In addition, Dr. Francis and Dr. Perlis said they thought the study did not follow the PE-owned practices for a long enough period of time after acquisition to detect any differences, and that the dataset – looking at practice acquisitions from 2012 to 2017 – was too old to paint a reliable picture of the current state of PE-owned practices. Acquisitions have accelerated since 2017.

In March 2021, Harvard researchers reported in JAMA Health Forum that PE purchases in health care peaked in the first quarter of 2018 and surged to almost as high a level in the fourth quarter of 2020, with 153 deals announced in the second half of the year. Of the 153 acquisitions, 98, or 64%, were for physician practices or other health care services.

Dr. Braun said his study focused on 2012-2017 because it was an available data set. And, he defended the snapshot, saying that he and his colleagues had as much as 4 years of postacquisition data for the practices that were purchased in 2013. He acknowledged there were less data on practices purchased from 2014 to 2016.

“It is possible that our results would change with a longer postacquisition period,” Dr. Braun said in an interview. But, he said there was no way to predict whether that change “would look better or worse for private equity.”

Modest price increases

The authors analyzed data from the Health Care Cost Institute, which aggregates claims for some 50 million individuals insured by Aetna, Humana, and United Healthcare. The data do not include Medicare claims.

They examined dermatologists in practices bought between 2013 and 2016 and compared them to dermatologists who were in practices not owned by private equity. Each dermatologist had to have at least 2 years of data, and the authors compared preacquisition with postacquisition data for those in PE-owned practices.

They identified 64 practices – with 246 dermatologists – bought by private investors. Preacquisition, PE practices were larger than non-PE practices, with 4.2 clinicians (including advanced practitioners) per practice, compared with 1.7 in non–investor-owned practices.

The authors looked at volume and prices for routine office visits (CPT code 99213), biopsies (11101), excisions (11602), destruction of first lesion (cryotherapy; 17000), and Mohs micrographic surgery (17311).

Prices for a routine office visit rose nominally in the first quarter after acquisition (under $1), stayed at 0 in the second quarter, decreased in the third quarter, and was 0 again in the fourth quarter. It was not until the fifth quarter post acquisition that prices rose, increasing by 3% ($2.26), and then rising 5% ($3.20) in the ninth quarter.

Dr. Braun said the price increases make sense because practices get “rolled up” into larger platforms, theoretically giving them more negotiating leverage with insurers. And he said the paper’s results “are consistent with physician practice consolidation research – mainly hospitals acquiring practices – that prices increase after acquisition.” He acknowledged that the dermatology paper found “more modest effects,” than other studies.

Dr. Francis, however, said the increases are basically “pocket change,” and that they reflect a failed promise from private investors that clinicians in PE-owned practices will be paid more. The small differences in pay may also mean that insurers are likely not acquiescing to the theoretical leverage of larger dermatology entities.

PE-owned dermatologists saw about 5% more patients per quarter initially, rising to 17% more per quarter by eight quarters after purchase, according to the study.

The study reported a significant increase in Mohs surgery and cryotherapy in the first quarter post purchase, and a significant increase in biopsies after eight quarters. But Dr. Braun and colleagues concluded that total spending per patient did not change significantly after acquisition. “That says that maybe physicians aren’t changing their behaviors that much,” Dr. Braun said in an interview.

Dr. Perlis disagreed, noting that practices rarely change quickly. “Anecdotally, most groups that are taken over, nothing changes initially,” while the new owners are getting a feel for the practice.

He also said the paper erred in not addressing quality of and access to care. “Quality and patient satisfaction and access are also other important factors that need to be examined.”

Not benign players

Both Dr. Perlis and Dr. Francis said the study may have been improved by having a dermatologist as a coauthor. Dr. Braun countered that he and his colleagues consulted several dermatologists during the course of the study, and that they also conducted 30 interviews with proponents and opponents of PE ownership.

The authors warned of what they viewed as some disturbing trends in PE-owned practices, including what Dr. Braun called “stealth” consolidation – investors making small purchases that fall outside of federal regulation, and then amassing them into large entities.

He also commented that it was “alarming” that PE-owned practices were hiring a larger number of advanced practitioners. The authors also expressed concern about leveraged buyouts, in which investors require a practice to carry high debt loads that can eventually drive it into bankruptcy.

“These are not benign players,” said Dr. Francis. He noted that it took “an act of Congress to stop surprise billing,” a tactic employed by PE-owned health care entities. “Policy makers should be looking at what’s best for patients, especially Medicare and vulnerable patients.”

Dr. Perlis also has qualms about PE-owned practices. “The money to support returns to investors has to come from somewhere and that creates an inherent tension between patient care and optimizing revenue for investors,” he said. “It’s a pretty head-on conflict.”

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS