User login

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men. The incidence of prostate cancer continues to rise. Roughly 220,800 men were expected to be newly diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2015.1 As the population ages and overall life expectancy increases, prostate cancer is likely to become a growing health care burden, especially because prostate cancer is primarily a disease of elderly males.

There have been no specific practice guidelines for managing prostate cancer in older adults, and the current management of older patients with prostate cancer is often suboptimal. Fortunately, the International Society of Geriatric Oncology recently assembled a multidisciplinary prostate cancer working group, which has begun offering guidelines on evidence-based treatments of prostate cancer in the geriatric population.

This article (part 1 of 2) provides a brief overview of prostate cancer epidemiology, pathology and screening in senior patients. The second part (to be published in August 2015) will focus on treatment.

Epidemiology

Currently more than 2 million men are estimated to have prostate cancer in the U.S. About 18% to 20% of U.S. males have a lifetime risk of developing prostate

cancer. Prostate cancer is mainly a disease of seniors aged between 60 and 70 years—the median age of prostate cancer at diagnosis is about 65 to 68 years. About 65% of new prostate cancers are diagnosed in males aged 65 years and 25% in males > aged 75 years.2 Most older patients with prostate cancer do not die of prostate cancer.

As the life expectancy of the general population increases, the risk of developing prostate cancer among seniors is also expected to proportionally rise. Historically, the cancer-specific mortality rate of prostate cancer in patients aged > 70 years was only 29% if managed either with active surveillance or hormonal manipulation.

Prevalence of Incidental Prostate Cancer

There is an abrupt age-dependent increase of prostate cancer incidence from the 5th decade of life on. Furthermore, there is a 1 in 3 chance of incidental prostate cancer in men aged between 60 to 69 years and a 46% prevalence in men aged > 70 years. Yin and colleagues found that 12% of patients in their study group harbored incidental, preclinical prostate cancer.3-5 The increasing prostate cancer incidence showed a strong and clear correlation with advancing age (Figure 1).

The lifetime probability of being diagnosed with prostate cancer also increases significantly with age.6,7 Patients with a life expectancy of < 5 years are unlikely

to benefit from cancer screening and may be more likely to experience complications and potential treatment-related harm as a result of screening. Therefore, estimating the patient’s residual life expectancy is a critical factor in the decision-making process for patients with prostate cancer. Life expectancy can differ, depending on various factors besides age, such as health, functional status, and medical comorbidities. The estimated age-related life expectancy for seniors has gradually increased over the previous 5 decades.8

Risk Factors

There are several risk factors for prostate cancer: age, race, and ethnicity; genetic factors; environmental and socioeconomic status; dietary status; and others. However, these factors may play only a limited role in the risk of prostate cancer, and a cautious approach and careful interpretation are required for their application in clinical practice.9,10

- Age. There is a sudden and dramatic increase in the prevalence of prostate cancer with advancing age. Prostate cancer is rarely diagnosed in men aged < 40 years, but thereafter, the incidence of prostate cancer climbs steadily.11 Surprisingly, subclinical microscopic prostate cancer was found at autopsy (death from unrelated causes) in a majority of senior males in their eighth decade of life.3

- Race/ethnicity. Epidemiologic studies in the U.S. found the highest incidence of prostate cancer in African American men (incidence rate of 235 per 100,000 African American vs 150 per 100,000 white men). Also, African American men tended to present with higher grades and stages of prostate cancer. There were much lower incidence rates of prostate cancer in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and American Indian and Alaska Natives (90 per 100,000, 126 per 100,000, and 78 per 100,000, respectively).9,10

- Diet. According to researchers, the western diet may be an important risk factors for prostate cancer. However, the actual relationship between obesity and prostate cancer is somewhat unclear, and any correlation is at present highly controversial. Some investigators have postulated that obesity can contribute to the development of prostate cancer; other studies have clearly established that obese patients, once diagnosed with prostate cancer, have inferior outcomes irrespective of the treatment modality used. Other studies, however, have suggested that certain hormonal profiles related to obesity may be protective against the development of prostate cancer.12,13

Pathologic Evaluation

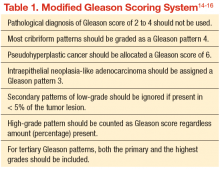

The original Gleason Grading System was devised based on the careful analysis of the cellular pattern of tumor architecture, using a 5-point scale: Tumor cells similar to normal-appearing prostate tissue were designated Gleason 1, 2, and 3; whereas cells/glands appearing abnormal were designated Gleason 4 and 5. The total Gleason score is the sum of the 2 most representative patterns, applied to both prostatectomy and needle biopsy specimens. The main differences from the original Gleason system, proposed by the 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology Modified Gleason System, are summarized in Table 1.

Early Detection and Screening

Although prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) detects many prostate cancer cases, concerns surrounding universal screening include the potential for overdiagnosis and overtreatment, along with the real possibility for adverse effects and complications from treatment. In addition, the recommendations for prostate cancer screening are not consistent among the various national health organizations. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends having an informed discussion between the health care provider and patient about the possible benefits and harms of screening. The discussion should not be initiated in men aged < 50 years (or aged < 45 years in men with high-risk features), and there is no need for screening in men with a life expectancy of < 10 years.

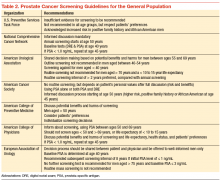

Prostate cancer screening may detect cancers that would not have become clinically significant. This is even more likely to be true when life expectancy decreases. Informed screening decisions in senior adults should be made according to the individual’s values and preferences in addition to the estimated outcomes and possible harms as a result of screening. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network offers similar recommendation to the ACS Screening Guidelines (Table 2).

Screening Recommendations for Seniors

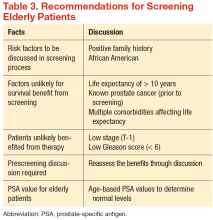

There have been no generally recognized guidelines on prostate cancer screening for seniors, although recently, Konety and colleagues published “The Iowa Prostate Cancer Consensus” for elderly prostate cancer patients (Table 3).17 The consensus includes:

- More prostate cancers are detected at an earlier stage, but many of them would never become clinically apparent in most patients’ life times

- A reduced mortality (either overall or disease specific) from screening is not proven during the course of 10-year follow-up

- Harms related to diagnostic and therapeutic procedures develop early and remain for an extended period, causing a negative impact on quality of life

- The small benefits of screening leading up to a prostatectomy are seen only after 12 years of follow-up and may be limited to a certain population group of

patients who are aged < 65 years - Current recommendations discourage the routine screening of seniors with short life expectancies (< 10 years) and depend on existing comorbidities and disease group risk

Conclusion

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in American men and the second most common cause of cancer death. Prostate cancer is almost twice as common among African Americans vs whites, and much less common in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, American Indian and Alaska Natives. Prostate cancer is generally a cancer of older seniors, and nearly 80% of seniors are estimated to harbor subclinical prostate cancer by their eighth decade of life.8 Prostate cancer screening is not universally recommended, and major professional associations support an informed, evidence-based, shared decision-making process between medical professionals and patients. This decision should include the careful consideration of patients’ life expectancy and existing medical comorbidities, always weighing the potential benefits against the possible screening and treatment-related harms.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin.2015;65(1):5-29.

2. Fitzpatrick JM. Management of localized prostate cancer in senior adults: the crucial role of comorbidity. BJU Int. 2008;101(suppl 2):16-22.

3. Yin M, Bastacky S, Chandran U, Becich MJ, Dhir R. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer in the general population: a study of healthy organ donors. J Urol. 2008;179(3):892-895.

4. Soos G, Tsakiris I, Szanto J, Turzo C, Haas PG, Dezso B.. The prevalence of prostate carcinoma and its precursor in Hungary: an autopsy study. Euro Urol. 2005;48(5):739-744.

5. Sánchez-Chapado M, Olmedilla G, Cabeza M, Donat E, Ruiz A. Prevalence of prostate cancer and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in Caucasian Mediterranean males: an autopsy study. Prostate. 2003;54(3):238-247.

6. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):71-96.

7. Sun L, Caire AA, Robertson CN, et al. Men older than 70 years have higher risk prostate cancer and poorer survival in the early and late prostate specific antigen eras. J Urol. 2009;182(5):2242-2248.

8. Haas GP, Sakr WA. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997;47(5):273-287.

9. Miocinovic R. Epidemiology and risk factors. In: Klein EA, Jones JP, eds. Management of Prostate Cancer. 3rd ed. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2013:1-11.

10. Crawford ED. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Urology. 2003;62(6 suppl 1):3-12.

11. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277-300.

12. Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Height, body weight, and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6(8):557-563.

13. Gann PH, Hennekens CH, Ma J, Longcope C, Stampfer MJ. Prospective

study of sex hormone levels and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(16):1118-1126.

14. Epstein JI. An update of the Gleason grading system. J Urol. 2010;183(2):433-440.

15. Egevad L, Mazzucchelli R, Montironi R. Implications of the International Society of Urological Pathology modified Gleason grading system. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(4):426-434.

16. Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL; ISUP Grading Committee. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostate Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(9): 1228-1242.

17. Konety BR, Sharp VJ, Raut H, Williams RD. Screening and management of prostate cancer in elderly men: the Iowa Prostate Cancer Consensus. Urology. 2008;71(3):511-514.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men. The incidence of prostate cancer continues to rise. Roughly 220,800 men were expected to be newly diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2015.1 As the population ages and overall life expectancy increases, prostate cancer is likely to become a growing health care burden, especially because prostate cancer is primarily a disease of elderly males.

There have been no specific practice guidelines for managing prostate cancer in older adults, and the current management of older patients with prostate cancer is often suboptimal. Fortunately, the International Society of Geriatric Oncology recently assembled a multidisciplinary prostate cancer working group, which has begun offering guidelines on evidence-based treatments of prostate cancer in the geriatric population.

This article (part 1 of 2) provides a brief overview of prostate cancer epidemiology, pathology and screening in senior patients. The second part (to be published in August 2015) will focus on treatment.

Epidemiology

Currently more than 2 million men are estimated to have prostate cancer in the U.S. About 18% to 20% of U.S. males have a lifetime risk of developing prostate

cancer. Prostate cancer is mainly a disease of seniors aged between 60 and 70 years—the median age of prostate cancer at diagnosis is about 65 to 68 years. About 65% of new prostate cancers are diagnosed in males aged 65 years and 25% in males > aged 75 years.2 Most older patients with prostate cancer do not die of prostate cancer.

As the life expectancy of the general population increases, the risk of developing prostate cancer among seniors is also expected to proportionally rise. Historically, the cancer-specific mortality rate of prostate cancer in patients aged > 70 years was only 29% if managed either with active surveillance or hormonal manipulation.

Prevalence of Incidental Prostate Cancer

There is an abrupt age-dependent increase of prostate cancer incidence from the 5th decade of life on. Furthermore, there is a 1 in 3 chance of incidental prostate cancer in men aged between 60 to 69 years and a 46% prevalence in men aged > 70 years. Yin and colleagues found that 12% of patients in their study group harbored incidental, preclinical prostate cancer.3-5 The increasing prostate cancer incidence showed a strong and clear correlation with advancing age (Figure 1).

The lifetime probability of being diagnosed with prostate cancer also increases significantly with age.6,7 Patients with a life expectancy of < 5 years are unlikely

to benefit from cancer screening and may be more likely to experience complications and potential treatment-related harm as a result of screening. Therefore, estimating the patient’s residual life expectancy is a critical factor in the decision-making process for patients with prostate cancer. Life expectancy can differ, depending on various factors besides age, such as health, functional status, and medical comorbidities. The estimated age-related life expectancy for seniors has gradually increased over the previous 5 decades.8

Risk Factors

There are several risk factors for prostate cancer: age, race, and ethnicity; genetic factors; environmental and socioeconomic status; dietary status; and others. However, these factors may play only a limited role in the risk of prostate cancer, and a cautious approach and careful interpretation are required for their application in clinical practice.9,10

- Age. There is a sudden and dramatic increase in the prevalence of prostate cancer with advancing age. Prostate cancer is rarely diagnosed in men aged < 40 years, but thereafter, the incidence of prostate cancer climbs steadily.11 Surprisingly, subclinical microscopic prostate cancer was found at autopsy (death from unrelated causes) in a majority of senior males in their eighth decade of life.3

- Race/ethnicity. Epidemiologic studies in the U.S. found the highest incidence of prostate cancer in African American men (incidence rate of 235 per 100,000 African American vs 150 per 100,000 white men). Also, African American men tended to present with higher grades and stages of prostate cancer. There were much lower incidence rates of prostate cancer in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and American Indian and Alaska Natives (90 per 100,000, 126 per 100,000, and 78 per 100,000, respectively).9,10

- Diet. According to researchers, the western diet may be an important risk factors for prostate cancer. However, the actual relationship between obesity and prostate cancer is somewhat unclear, and any correlation is at present highly controversial. Some investigators have postulated that obesity can contribute to the development of prostate cancer; other studies have clearly established that obese patients, once diagnosed with prostate cancer, have inferior outcomes irrespective of the treatment modality used. Other studies, however, have suggested that certain hormonal profiles related to obesity may be protective against the development of prostate cancer.12,13

Pathologic Evaluation

The original Gleason Grading System was devised based on the careful analysis of the cellular pattern of tumor architecture, using a 5-point scale: Tumor cells similar to normal-appearing prostate tissue were designated Gleason 1, 2, and 3; whereas cells/glands appearing abnormal were designated Gleason 4 and 5. The total Gleason score is the sum of the 2 most representative patterns, applied to both prostatectomy and needle biopsy specimens. The main differences from the original Gleason system, proposed by the 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology Modified Gleason System, are summarized in Table 1.

Early Detection and Screening

Although prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) detects many prostate cancer cases, concerns surrounding universal screening include the potential for overdiagnosis and overtreatment, along with the real possibility for adverse effects and complications from treatment. In addition, the recommendations for prostate cancer screening are not consistent among the various national health organizations. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends having an informed discussion between the health care provider and patient about the possible benefits and harms of screening. The discussion should not be initiated in men aged < 50 years (or aged < 45 years in men with high-risk features), and there is no need for screening in men with a life expectancy of < 10 years.

Prostate cancer screening may detect cancers that would not have become clinically significant. This is even more likely to be true when life expectancy decreases. Informed screening decisions in senior adults should be made according to the individual’s values and preferences in addition to the estimated outcomes and possible harms as a result of screening. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network offers similar recommendation to the ACS Screening Guidelines (Table 2).

Screening Recommendations for Seniors

There have been no generally recognized guidelines on prostate cancer screening for seniors, although recently, Konety and colleagues published “The Iowa Prostate Cancer Consensus” for elderly prostate cancer patients (Table 3).17 The consensus includes:

- More prostate cancers are detected at an earlier stage, but many of them would never become clinically apparent in most patients’ life times

- A reduced mortality (either overall or disease specific) from screening is not proven during the course of 10-year follow-up

- Harms related to diagnostic and therapeutic procedures develop early and remain for an extended period, causing a negative impact on quality of life

- The small benefits of screening leading up to a prostatectomy are seen only after 12 years of follow-up and may be limited to a certain population group of

patients who are aged < 65 years - Current recommendations discourage the routine screening of seniors with short life expectancies (< 10 years) and depend on existing comorbidities and disease group risk

Conclusion

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in American men and the second most common cause of cancer death. Prostate cancer is almost twice as common among African Americans vs whites, and much less common in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, American Indian and Alaska Natives. Prostate cancer is generally a cancer of older seniors, and nearly 80% of seniors are estimated to harbor subclinical prostate cancer by their eighth decade of life.8 Prostate cancer screening is not universally recommended, and major professional associations support an informed, evidence-based, shared decision-making process between medical professionals and patients. This decision should include the careful consideration of patients’ life expectancy and existing medical comorbidities, always weighing the potential benefits against the possible screening and treatment-related harms.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men. The incidence of prostate cancer continues to rise. Roughly 220,800 men were expected to be newly diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2015.1 As the population ages and overall life expectancy increases, prostate cancer is likely to become a growing health care burden, especially because prostate cancer is primarily a disease of elderly males.

There have been no specific practice guidelines for managing prostate cancer in older adults, and the current management of older patients with prostate cancer is often suboptimal. Fortunately, the International Society of Geriatric Oncology recently assembled a multidisciplinary prostate cancer working group, which has begun offering guidelines on evidence-based treatments of prostate cancer in the geriatric population.

This article (part 1 of 2) provides a brief overview of prostate cancer epidemiology, pathology and screening in senior patients. The second part (to be published in August 2015) will focus on treatment.

Epidemiology

Currently more than 2 million men are estimated to have prostate cancer in the U.S. About 18% to 20% of U.S. males have a lifetime risk of developing prostate

cancer. Prostate cancer is mainly a disease of seniors aged between 60 and 70 years—the median age of prostate cancer at diagnosis is about 65 to 68 years. About 65% of new prostate cancers are diagnosed in males aged 65 years and 25% in males > aged 75 years.2 Most older patients with prostate cancer do not die of prostate cancer.

As the life expectancy of the general population increases, the risk of developing prostate cancer among seniors is also expected to proportionally rise. Historically, the cancer-specific mortality rate of prostate cancer in patients aged > 70 years was only 29% if managed either with active surveillance or hormonal manipulation.

Prevalence of Incidental Prostate Cancer

There is an abrupt age-dependent increase of prostate cancer incidence from the 5th decade of life on. Furthermore, there is a 1 in 3 chance of incidental prostate cancer in men aged between 60 to 69 years and a 46% prevalence in men aged > 70 years. Yin and colleagues found that 12% of patients in their study group harbored incidental, preclinical prostate cancer.3-5 The increasing prostate cancer incidence showed a strong and clear correlation with advancing age (Figure 1).

The lifetime probability of being diagnosed with prostate cancer also increases significantly with age.6,7 Patients with a life expectancy of < 5 years are unlikely

to benefit from cancer screening and may be more likely to experience complications and potential treatment-related harm as a result of screening. Therefore, estimating the patient’s residual life expectancy is a critical factor in the decision-making process for patients with prostate cancer. Life expectancy can differ, depending on various factors besides age, such as health, functional status, and medical comorbidities. The estimated age-related life expectancy for seniors has gradually increased over the previous 5 decades.8

Risk Factors

There are several risk factors for prostate cancer: age, race, and ethnicity; genetic factors; environmental and socioeconomic status; dietary status; and others. However, these factors may play only a limited role in the risk of prostate cancer, and a cautious approach and careful interpretation are required for their application in clinical practice.9,10

- Age. There is a sudden and dramatic increase in the prevalence of prostate cancer with advancing age. Prostate cancer is rarely diagnosed in men aged < 40 years, but thereafter, the incidence of prostate cancer climbs steadily.11 Surprisingly, subclinical microscopic prostate cancer was found at autopsy (death from unrelated causes) in a majority of senior males in their eighth decade of life.3

- Race/ethnicity. Epidemiologic studies in the U.S. found the highest incidence of prostate cancer in African American men (incidence rate of 235 per 100,000 African American vs 150 per 100,000 white men). Also, African American men tended to present with higher grades and stages of prostate cancer. There were much lower incidence rates of prostate cancer in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and American Indian and Alaska Natives (90 per 100,000, 126 per 100,000, and 78 per 100,000, respectively).9,10

- Diet. According to researchers, the western diet may be an important risk factors for prostate cancer. However, the actual relationship between obesity and prostate cancer is somewhat unclear, and any correlation is at present highly controversial. Some investigators have postulated that obesity can contribute to the development of prostate cancer; other studies have clearly established that obese patients, once diagnosed with prostate cancer, have inferior outcomes irrespective of the treatment modality used. Other studies, however, have suggested that certain hormonal profiles related to obesity may be protective against the development of prostate cancer.12,13

Pathologic Evaluation

The original Gleason Grading System was devised based on the careful analysis of the cellular pattern of tumor architecture, using a 5-point scale: Tumor cells similar to normal-appearing prostate tissue were designated Gleason 1, 2, and 3; whereas cells/glands appearing abnormal were designated Gleason 4 and 5. The total Gleason score is the sum of the 2 most representative patterns, applied to both prostatectomy and needle biopsy specimens. The main differences from the original Gleason system, proposed by the 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology Modified Gleason System, are summarized in Table 1.

Early Detection and Screening

Although prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) detects many prostate cancer cases, concerns surrounding universal screening include the potential for overdiagnosis and overtreatment, along with the real possibility for adverse effects and complications from treatment. In addition, the recommendations for prostate cancer screening are not consistent among the various national health organizations. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends having an informed discussion between the health care provider and patient about the possible benefits and harms of screening. The discussion should not be initiated in men aged < 50 years (or aged < 45 years in men with high-risk features), and there is no need for screening in men with a life expectancy of < 10 years.

Prostate cancer screening may detect cancers that would not have become clinically significant. This is even more likely to be true when life expectancy decreases. Informed screening decisions in senior adults should be made according to the individual’s values and preferences in addition to the estimated outcomes and possible harms as a result of screening. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network offers similar recommendation to the ACS Screening Guidelines (Table 2).

Screening Recommendations for Seniors

There have been no generally recognized guidelines on prostate cancer screening for seniors, although recently, Konety and colleagues published “The Iowa Prostate Cancer Consensus” for elderly prostate cancer patients (Table 3).17 The consensus includes:

- More prostate cancers are detected at an earlier stage, but many of them would never become clinically apparent in most patients’ life times

- A reduced mortality (either overall or disease specific) from screening is not proven during the course of 10-year follow-up

- Harms related to diagnostic and therapeutic procedures develop early and remain for an extended period, causing a negative impact on quality of life

- The small benefits of screening leading up to a prostatectomy are seen only after 12 years of follow-up and may be limited to a certain population group of

patients who are aged < 65 years - Current recommendations discourage the routine screening of seniors with short life expectancies (< 10 years) and depend on existing comorbidities and disease group risk

Conclusion

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in American men and the second most common cause of cancer death. Prostate cancer is almost twice as common among African Americans vs whites, and much less common in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, American Indian and Alaska Natives. Prostate cancer is generally a cancer of older seniors, and nearly 80% of seniors are estimated to harbor subclinical prostate cancer by their eighth decade of life.8 Prostate cancer screening is not universally recommended, and major professional associations support an informed, evidence-based, shared decision-making process between medical professionals and patients. This decision should include the careful consideration of patients’ life expectancy and existing medical comorbidities, always weighing the potential benefits against the possible screening and treatment-related harms.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin.2015;65(1):5-29.

2. Fitzpatrick JM. Management of localized prostate cancer in senior adults: the crucial role of comorbidity. BJU Int. 2008;101(suppl 2):16-22.

3. Yin M, Bastacky S, Chandran U, Becich MJ, Dhir R. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer in the general population: a study of healthy organ donors. J Urol. 2008;179(3):892-895.

4. Soos G, Tsakiris I, Szanto J, Turzo C, Haas PG, Dezso B.. The prevalence of prostate carcinoma and its precursor in Hungary: an autopsy study. Euro Urol. 2005;48(5):739-744.

5. Sánchez-Chapado M, Olmedilla G, Cabeza M, Donat E, Ruiz A. Prevalence of prostate cancer and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in Caucasian Mediterranean males: an autopsy study. Prostate. 2003;54(3):238-247.

6. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):71-96.

7. Sun L, Caire AA, Robertson CN, et al. Men older than 70 years have higher risk prostate cancer and poorer survival in the early and late prostate specific antigen eras. J Urol. 2009;182(5):2242-2248.

8. Haas GP, Sakr WA. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997;47(5):273-287.

9. Miocinovic R. Epidemiology and risk factors. In: Klein EA, Jones JP, eds. Management of Prostate Cancer. 3rd ed. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2013:1-11.

10. Crawford ED. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Urology. 2003;62(6 suppl 1):3-12.

11. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277-300.

12. Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Height, body weight, and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6(8):557-563.

13. Gann PH, Hennekens CH, Ma J, Longcope C, Stampfer MJ. Prospective

study of sex hormone levels and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(16):1118-1126.

14. Epstein JI. An update of the Gleason grading system. J Urol. 2010;183(2):433-440.

15. Egevad L, Mazzucchelli R, Montironi R. Implications of the International Society of Urological Pathology modified Gleason grading system. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(4):426-434.

16. Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL; ISUP Grading Committee. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostate Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(9): 1228-1242.

17. Konety BR, Sharp VJ, Raut H, Williams RD. Screening and management of prostate cancer in elderly men: the Iowa Prostate Cancer Consensus. Urology. 2008;71(3):511-514.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin.2015;65(1):5-29.

2. Fitzpatrick JM. Management of localized prostate cancer in senior adults: the crucial role of comorbidity. BJU Int. 2008;101(suppl 2):16-22.

3. Yin M, Bastacky S, Chandran U, Becich MJ, Dhir R. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer in the general population: a study of healthy organ donors. J Urol. 2008;179(3):892-895.

4. Soos G, Tsakiris I, Szanto J, Turzo C, Haas PG, Dezso B.. The prevalence of prostate carcinoma and its precursor in Hungary: an autopsy study. Euro Urol. 2005;48(5):739-744.

5. Sánchez-Chapado M, Olmedilla G, Cabeza M, Donat E, Ruiz A. Prevalence of prostate cancer and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in Caucasian Mediterranean males: an autopsy study. Prostate. 2003;54(3):238-247.

6. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):71-96.

7. Sun L, Caire AA, Robertson CN, et al. Men older than 70 years have higher risk prostate cancer and poorer survival in the early and late prostate specific antigen eras. J Urol. 2009;182(5):2242-2248.

8. Haas GP, Sakr WA. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997;47(5):273-287.

9. Miocinovic R. Epidemiology and risk factors. In: Klein EA, Jones JP, eds. Management of Prostate Cancer. 3rd ed. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2013:1-11.

10. Crawford ED. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. Urology. 2003;62(6 suppl 1):3-12.

11. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277-300.

12. Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Height, body weight, and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6(8):557-563.

13. Gann PH, Hennekens CH, Ma J, Longcope C, Stampfer MJ. Prospective

study of sex hormone levels and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(16):1118-1126.

14. Epstein JI. An update of the Gleason grading system. J Urol. 2010;183(2):433-440.

15. Egevad L, Mazzucchelli R, Montironi R. Implications of the International Society of Urological Pathology modified Gleason grading system. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(4):426-434.

16. Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL; ISUP Grading Committee. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostate Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(9): 1228-1242.

17. Konety BR, Sharp VJ, Raut H, Williams RD. Screening and management of prostate cancer in elderly men: the Iowa Prostate Cancer Consensus. Urology. 2008;71(3):511-514.