User login

CASE: A complex presentation, a deferred diagnosis

J. M. is a 25-year-old white nulliparous woman who visits our office reporting pelvic pain. She says the pain began when she was 16 years old, when she was taken to the emergency room for what was thought to be appendicitis. There, she was given a diagnosis of acute, severe cystitis.

Several months later, J. M. began experiencing dysmenorrhea and was given an additional diagnosis of endometriosis, for which she was treated both medically and surgically.

By the time she visits our office, J. M.’s pain has become a daily occurrence that ranges in intensity from 1 to 10 on the numerical rating scale (10, most severe). The pain is mostly localized to the right lower quadrant (RLQ) and is exacerbated by menses and intercourse. She reports mild urinary urgency, voiding every 5 to 6 hours, and one to two episodes of nocturia daily. She has no gastrointestinal symptoms.

We identify four active myofascial trigger points in the RLQ, as well as uterine and adnexal tenderness upon examination. A diagnostic laparoscopy and histology confirm endometriosis, but only three lesions are observed.

After the operation, J. M. is given 5 mg of norethindrone acetate daily to ease the pain that is thought to arise from her endometriosis. Because the pain persists, we add injections of 0.25% bupivacaine at the myofascial trigger points every 4 to 6 weeks. Her pain diminishes for as long as 6 weeks after each injection.

Fifteen months after the laparoscopy, J. M. complains of the need to void every 2 hours because of discomfort and pain and continued nocturia. This time, she experiences no pain at the trigger points, but her bladder is exquisitely tender upon palpation. We order urinalysis and culture, both of which are negative. A potassium sensitivity test is markedly positive, however, confirming the suspected diagnosis of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome.

Could this diagnosis have been made earlier?

J. M. is a real patient in our clinical practice. Her case illustrates the challenges a gynecologist faces in diagnosing chronic pelvic pain. In retrospect, it is apparent that endometriosis was not a major generator of her pain. Instead, abdominal wall myofascial pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) were the major generators. Although her myofascial pain appeared to respond to treatment with bupivacaine, she began to clearly manifest symptoms of IC/PBS.

This article describes the often-thorny diagnosis of IC/PBS and discusses the theories that have been proposed to explain the syndrome. In Part 2 of this article, the many components of management are discussed.

Early diagnosis and treatment appear to improve the response to treatment and prevent progression to severe disease. Because the gynecologist is the physician who commonly sees women at the onset of chronic pelvic pain, he or she is ideally positioned to diagnose this disorder early in its course.

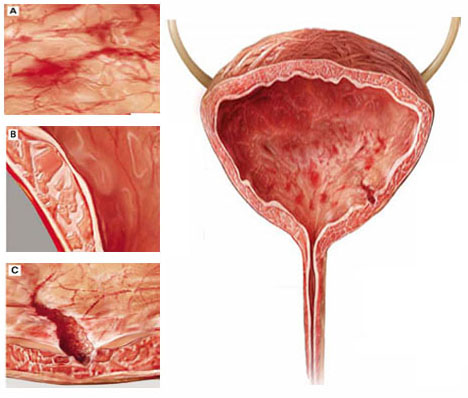

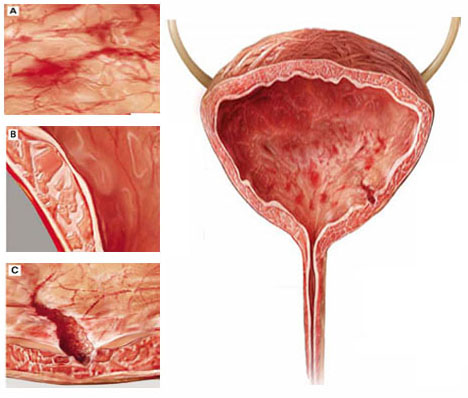

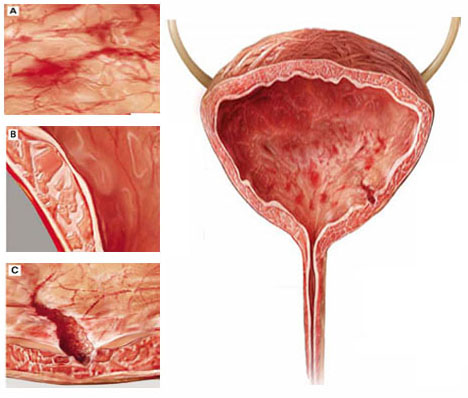

Although interstitial cystitis (IC) occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or malignancy, some pathology may become apparent during cystoscopy with hydrodistention. Potential findings include:

(A) glomerulations, or hemorrhages of the bladder mucosa

(B) damage to the urothelium

(C) Hunner’s ulcer, a defect of the urothelium that is pathognomonic for IC but uncommon.

What is IC/PBS?

This disorder consists of pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort related to the bladder and associated with a persistent urge to void. It occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or other pathology such as bladder carcinoma or cystitis induced by radiation or medication.

The term interstitial cystitis appears to have originated with New York gynecologist Alexander Johnston Chalmers Skene in 1887. Traditionally, interstitial cystitis was diagnosed only in severe cases in which bladder capacity was greatly reduced and Hunner’s ulcer, a fissuring of the bladder mucosa, was present at cystoscopy.1

In 1978, Messing and Stamey broadened the diagnosis of IC to include glomerulations at cystoscopy (FIGURE 1).2 It is now clear that the bladder can be a source of pelvic pain without these clinical findings. As a result, nomenclature has become confusing. Terms in current use include painful bladder syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and a combination of these names. Confusing matters further is the fact that these terms are not always used interchangeably.

Despite controversy over nomenclature and diagnostic criteria, there is no uncertainty that the lives of women who have IC/PBS are significantly altered by the disease. It adversely affects leisure activity, family relationships, and travel in 70% to 94% of patients.3 Suicidal thoughts are three to four times more likely in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population. Quality of life is markedly decreased across all domains, and depressive symptoms are much more common in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population.4

IC/PBS appears to affect women more often than men, and it is a frequent diagnosis among women who have chronic pelvic pain. For example, in a primary care population of women 15 to 73 years old who had chronic pelvic pain, about 30% were determined to have pain of urologic origin.5 It has been suggested, based on symptoms of urgency-frequency and a positive potassium sensitivity test, that approximately 85% of women who see a gynecologist for chronic pelvic pain have IC/PBS in addition to or instead of a gynecologic diagnosis.6 Among women given a diagnosis of endometriosis, 35% to 90% have been found to have IC/PBS as well.

FIGURE 1 Glomerulations are a common finding

Cystoscopy with hydrodistention often, but not always, reveals glomerulations (mucosal hemorrhages) in a patient who has interstitial cystitis.

Two screening tools may aid the diagnosis

IC/PBS is a clinical diagnosis, based on symptoms and signs. Although some controversy surrounds this statement, there is no question that we lack a gold-standard test to reliably make the diagnosis.

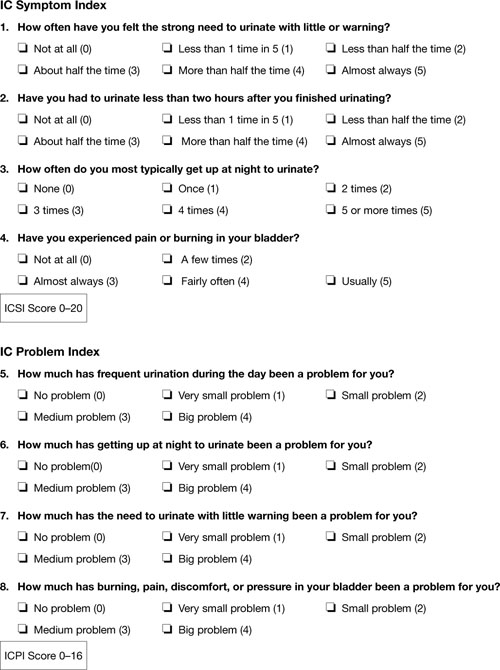

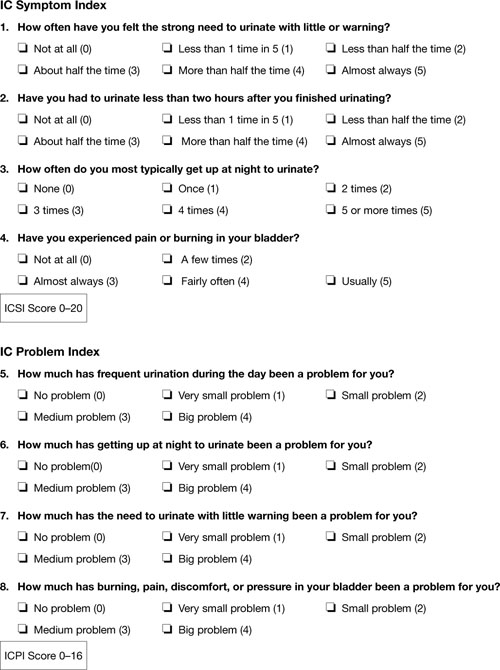

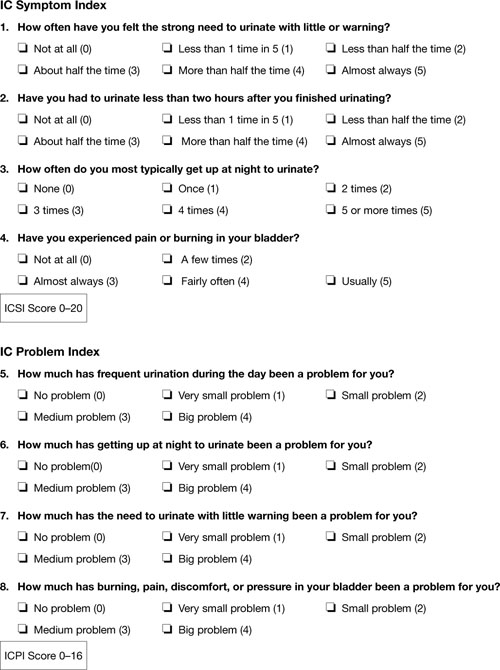

Two screening instruments are commonly used to identify patients in whom IC/PBS should be considered. One is the O’Leary-Sant questionnaire (TABLE 1), which incorporates two scales:

- the IC Symptom Index (ICSI)

- the IC Problem Index (ICPI).

The O’Leary-Sant questionnaire was not designed specifically to diagnose IC/PBS but to aid in its evaluation and management and to facilitate clinical research.

TABLE 1 The O’Leary Sant IC questionnaire

Please mark the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

TABLE 2

The Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Symptom Scale

Please circle the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1. | How many times do you go to the bathroom DURING THE DAY (to void or empty your bladder)? | 3-6 | 7-10 | 11-14 | 15-19 | 20 or more |

| 2. | How many times do you go to the bathroom AT NIGHT (to void or empty your bladder)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 or more |

| 3. | If you get up at night to void or empty your bladder, does it bother you? | Never | Mildly | Moderately | Severely | |

| 4. | Are you sexually active? No ___ Yes ___ | |||||

| 5. | If you are sexually active, do you now or have you ever had pain or symptoms during or after sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 6. | If you have pain with intercourse, does it make you avoid sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 7. | Do you have pain associated with your bladder or in your pelvis (lower abdomen, labia, vagina, urethra, perineum)? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 8. | Do you have urgency after voiding? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 9. | If you have pain, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 10. | Does your pain bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 11. | If you have urgency, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 12. | Does your urgency bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| PUR Score 0–35 | ||||||

In a busy gynecologic practice, routine use of one of these questionnaires can greatly facilitate identification of patients who may have IC/PBS.

Diagnosis can be straightforward—but often it isn’t

In many patients, diagnosis of IC/PBS is straightforward, with classic findings:

- pelvic pain

- urinary frequency (voiding every 1 or 2 hours)

- discomfort or increased pain (as opposed to a fear of losing urine) leading to urinary urge

- significant tenderness during single-digit palpation of the bladder at the time of pelvic examination

- nocturia in many cases.

Be aware that diagnosis can be more challenging when the patient is in the early course of the disease. About 90% of patients who have IC/PBS have only one symptom in the beginning—fewer than 10% experience the simultaneous onset of urgency, frequency, nocturia, and pain. The mean time from development of the initial symptom until manifestation of all symptoms ranges from 2 to 5 years.7 In about one third of patients, the initial symptom is urinary frequency and urgency preceding the onset of pain—but almost equal numbers of patients develop pelvic pain as a solitary symptom before the onset of any urinary symptoms.

Complicating matters is the fact that symptoms are often episodic early in the course of the disease. The episodic nature of symptoms often leads to multiple misdiagnoses such as urinary tract infection and recurrent or chronic cystitis. A history of empiric treatment of recurrent urinary tract infection without documentation of a positive culture is common in women who have IC/PBS. A patient who has early interstitial cystitis may respond to antibiotic treatment due to the natural waxing and waning of symptoms, the placebo effect, or an increase in fluid intake that usually accompanies antibiotic usage (dilute urine is less irritating to the bladder). Awareness of the possibility of IC/PBS in these patients is essential if diagnosis is to be made as early as possible.

Dyspareunia is another common symptom in patients who have IC/PBS. Pain during intercourse appears to arise from tenderness in the pelvic floor muscles as well as the bladder. It may also occur upon vaginal entry due to associated vulvar vestibulitis.8 In postmenopausal women, vulvovaginal atrophy may contribute to dyspareunia as well.

Also consider IC/PBS when a patient continues to experience pelvic pain after treatment of endometriosis or after hysterectomy. In one study, 80% of women who had persistent chronic pelvic pain after hysterectomy had interstitial cystitis.9 Among women who have endometriosis, we have found that 35% have IC/PBS (unpublished data). Chung reported that 85% of women who have endometriosis also have IC/PBS.10

Which diagnostic studies are useful?

To some extent, IC/PBS is a diagnosis of exclusion, as other possible causes of pelvic pain, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and nocturia must be excluded. Urinalysis and urine culture are essential tests in the evaluation of women suspected of having interstitial cystitis. Urinary tract infection must be excluded with a negative urine culture. If a patient has hematuria, urine cytology or cystoscopy is recommended to exclude malignancy. Urine cytology or cystoscopy is also recommended if the patient has a history of smoking (because of the strong association between bladder cancer and smoking) or is older than 50 years.

Some experts still insist that cystoscopic hydrodistention is necessary. Cystoscopy with hydrodistention under general or regional anesthesia has long been considered the “gold standard” diagnostic test for IC. Identification of a Hunner ulcer is pathognomonic, but it is an uncommon finding and one usually discovered only in advanced cases. More often, cystoscopy with hydrodistention in a patient who has IC reveals glomerulations, which are mucosal hemorrhages that exhibit a characteristic appearance upon second filling of the bladder (FIGURE 1).

The value of cystoscopy has recently been questioned because at least 10% of patients who have clear clinical evidence of interstitial cystitis have normal findings at the time of cystoscopic hydrodistention.11 Glomerulations have also been observed in asymptomatic patients after hydrodistention with as much as 950 mL of water. In at least one published study, glomerulations did not distinguish patients who had a clinical diagnosis of IC from asymptomatic women.12

The potassium sensitivity (parsons) test (PST) may be a useful diagnostic test for IC. It is based on the concept that patients who have the disease have a defective urothelium that allows cations to penetrate the bladder wall and depolarize the sensory C-fibers, generating lower urinary tract symptoms.13 An alternative explanation for this test may be that it identifies patients who have a hyperalgesic or allodynic bladder, whether or not there is a defect in the urothelium.

The test is performed by instilling 40 mL of sterile water into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is then asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The water is drained and 40 mL of a 0.4-molar solution of potassium chloride (40 mEq in 100 mL of water), containing a total of 16 mEq of potassium chloride, are instilled into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is again asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The test is positive when the patient reports a change of two points or more on the pain or urgency scale after instillation of potassium chloride solution.

The PST is negative in 96% of normal controls and positive in 70% to 80% of patients who have IC.14 Patients who have radiation cystitis or bacterial cystitis also have a positive response to the PST. Sensitivity of the test may decrease if the patient has recently been treated for IC, especially if the therapy involved dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or instillation of an anesthetic.

The PST can trigger the flare of severe symptoms in patients who have IC, so all women who have a positive test should receive a “rescue cocktail” after the potassium chloride solution is drained. Two of the most common rescue solutions are:

- 20,000 U of heparin mixed with 20 mL of 1% lidocaine

- a 15-mL mixture of 40,000 U of heparin, 8 mL of 2% lidocaine, and 3 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate.

The rescue cocktail usually reverses the urgency and pain brought on by potassium chloride.

A patient who has a high level of pain with IC may be unable to discern a change when potassium chloride solution is instilled, or she may be unable to tolerate the discomfort it causes. Instillation of an anesthetic agent into the bladder may be a useful diagnostic test in such a case. The rescue cocktail described above also provides an opportunity for patient and clinician to see whether her symptoms abate after introduction of the anesthetic agent.

Last, researchers have long sought a simple urinary biomarker that would be specific for IC, but none are available for routine clinical use.

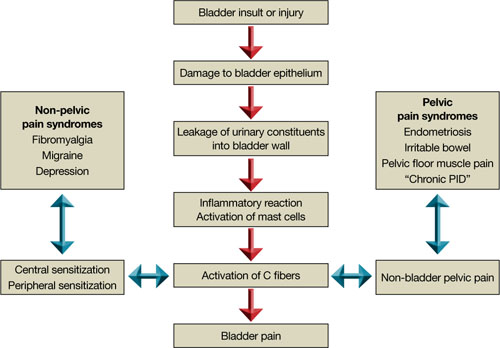

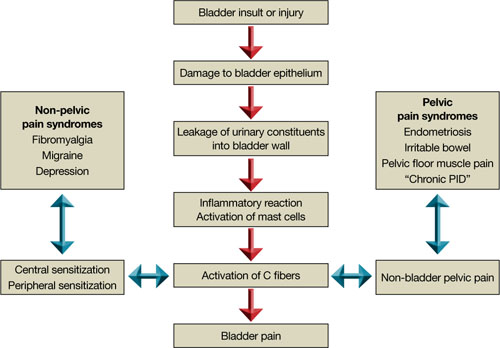

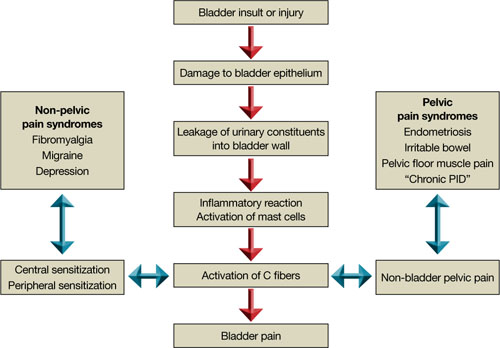

Although the cause of interstitial cystitis is unknown, two main theories have developed to explain it. The popular, single end-organ theory, illustrated by the pathway with red arrows in FIGURE 2, holds that an injury or insult to the bladder is the cause. When that injury fails to heal completely, the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder is left with a defect, allowing leakage of urinary components, such as potassium, into the mucosa and submucosa. This leakage triggers an inflammatory reaction and activates nociceptors in the bladder, including nociceptors that do not usually respond to bladder distention and stimulation (so-called silent nociceptors). Activation of these nociceptors generates allodynia in the bladder, meaning that normal distention of the bladder becomes painful.

There is evidence that other pathways also lead to IC/PBS, as illustrated by the blue, bidirectional arrows. Other generators of pelvic pain, both visceral and somatic, can neurologically activate bladder nociceptors at the central level, creating “crosstalk” and leading to bladder pain and IC/PBS. In such cases, antidromic transmission (efferent transmission in afferent nerves) can lead to neurogenic bladder inflammation and contribute further to pelvic pain. Examples of pelvic pain syndromes thought to have links to IC/PBS include endometriosis, irritable bowel syndrome, and pelvic floor tension myalgia.

In addition, there is evidence that nonpelvic syndromes, such as fibromyalgia and migraine, can lead to central or peripheral sensitization that results in IC/PBS. That is, sensitization leads to chronic bladder pain from injury or stimulation that would otherwise not cause pain.

As these theories suggest, it is likely that more than one disease and one disease pathway are encompassed within the syndrome called IC/PBS. In the opening case, it appears that a severe urinary tract infection and persistent myofascial pain, and possibly endometriosis, may have been variables leading to the development of IC/PBS.

FIGURE 2 Pathways to pain

Part 2 of this article reviews components of the treatment of IC/PBS and their stepwise application.

1. Hunner GL. A rare type of bladder ulcer in women: report of cases. Boston Med Surg. 1915;172.-

2. Messing EM, Stamey TA. Interstitial cystitis: early diagnosis, pathology, and treatment. Urology. 1978;12(4):381-392.

3. Koziol JA, Clark DC, Gittes RF, Tan EM. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: a survey of 374 patients. J Urol. 1993;149(3):465-469.

4. Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Hoffman A, Kreder KJ. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2002;167(4):1763-1767.

5. Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(11):1149-1155.

6. Parsons CL, Bullen M, Kahn BS, Stanford EJ, Willems JJ. Gynecologic presentation of interstitial cystitis as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98 (1):127-132.

7. Driscoll A, Teichman JM. How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol. 2001;166(6):2118-2120.

8. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996-1002.

9. Chung MK. Interstitial cystitis in persistent posthysterectomy chronic pelvic pain. JSLS. 2004;8(4):329-333.

10. Chung MK, Chung RR, Gordon D, Jennings C. The evil twins of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: endometriosis and interstitial cystitis. JSLS. 2002;6(4):311-314.

11. Messing EM. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1987;29(4 suppl):4-7.

12. Waxman JA, Sulak PJ, Kuehl TJ. Cystoscopic findings consistent with interstitial cystitis in normal women undergoing tubal ligation. J Urol. 1998;160(5):1663-1667.

13. Parsons CL, Zupkas P, Parsons JK. Intravesical potassium sensitivity in patients with interstitial cystitis and urethral syndrome. Urology. 2001;57(3):428-433.

14. Parsons CL, Stein PC, Bidair M, Lebow D. Abnormal sensitivity to intravesical potassium in interstitial cystitis and radiation cystitis. Neurourol Urodyn. 1994;13(5):515-520.

CASE: A complex presentation, a deferred diagnosis

J. M. is a 25-year-old white nulliparous woman who visits our office reporting pelvic pain. She says the pain began when she was 16 years old, when she was taken to the emergency room for what was thought to be appendicitis. There, she was given a diagnosis of acute, severe cystitis.

Several months later, J. M. began experiencing dysmenorrhea and was given an additional diagnosis of endometriosis, for which she was treated both medically and surgically.

By the time she visits our office, J. M.’s pain has become a daily occurrence that ranges in intensity from 1 to 10 on the numerical rating scale (10, most severe). The pain is mostly localized to the right lower quadrant (RLQ) and is exacerbated by menses and intercourse. She reports mild urinary urgency, voiding every 5 to 6 hours, and one to two episodes of nocturia daily. She has no gastrointestinal symptoms.

We identify four active myofascial trigger points in the RLQ, as well as uterine and adnexal tenderness upon examination. A diagnostic laparoscopy and histology confirm endometriosis, but only three lesions are observed.

After the operation, J. M. is given 5 mg of norethindrone acetate daily to ease the pain that is thought to arise from her endometriosis. Because the pain persists, we add injections of 0.25% bupivacaine at the myofascial trigger points every 4 to 6 weeks. Her pain diminishes for as long as 6 weeks after each injection.

Fifteen months after the laparoscopy, J. M. complains of the need to void every 2 hours because of discomfort and pain and continued nocturia. This time, she experiences no pain at the trigger points, but her bladder is exquisitely tender upon palpation. We order urinalysis and culture, both of which are negative. A potassium sensitivity test is markedly positive, however, confirming the suspected diagnosis of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome.

Could this diagnosis have been made earlier?

J. M. is a real patient in our clinical practice. Her case illustrates the challenges a gynecologist faces in diagnosing chronic pelvic pain. In retrospect, it is apparent that endometriosis was not a major generator of her pain. Instead, abdominal wall myofascial pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) were the major generators. Although her myofascial pain appeared to respond to treatment with bupivacaine, she began to clearly manifest symptoms of IC/PBS.

This article describes the often-thorny diagnosis of IC/PBS and discusses the theories that have been proposed to explain the syndrome. In Part 2 of this article, the many components of management are discussed.

Early diagnosis and treatment appear to improve the response to treatment and prevent progression to severe disease. Because the gynecologist is the physician who commonly sees women at the onset of chronic pelvic pain, he or she is ideally positioned to diagnose this disorder early in its course.

Although interstitial cystitis (IC) occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or malignancy, some pathology may become apparent during cystoscopy with hydrodistention. Potential findings include:

(A) glomerulations, or hemorrhages of the bladder mucosa

(B) damage to the urothelium

(C) Hunner’s ulcer, a defect of the urothelium that is pathognomonic for IC but uncommon.

What is IC/PBS?

This disorder consists of pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort related to the bladder and associated with a persistent urge to void. It occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or other pathology such as bladder carcinoma or cystitis induced by radiation or medication.

The term interstitial cystitis appears to have originated with New York gynecologist Alexander Johnston Chalmers Skene in 1887. Traditionally, interstitial cystitis was diagnosed only in severe cases in which bladder capacity was greatly reduced and Hunner’s ulcer, a fissuring of the bladder mucosa, was present at cystoscopy.1

In 1978, Messing and Stamey broadened the diagnosis of IC to include glomerulations at cystoscopy (FIGURE 1).2 It is now clear that the bladder can be a source of pelvic pain without these clinical findings. As a result, nomenclature has become confusing. Terms in current use include painful bladder syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and a combination of these names. Confusing matters further is the fact that these terms are not always used interchangeably.

Despite controversy over nomenclature and diagnostic criteria, there is no uncertainty that the lives of women who have IC/PBS are significantly altered by the disease. It adversely affects leisure activity, family relationships, and travel in 70% to 94% of patients.3 Suicidal thoughts are three to four times more likely in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population. Quality of life is markedly decreased across all domains, and depressive symptoms are much more common in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population.4

IC/PBS appears to affect women more often than men, and it is a frequent diagnosis among women who have chronic pelvic pain. For example, in a primary care population of women 15 to 73 years old who had chronic pelvic pain, about 30% were determined to have pain of urologic origin.5 It has been suggested, based on symptoms of urgency-frequency and a positive potassium sensitivity test, that approximately 85% of women who see a gynecologist for chronic pelvic pain have IC/PBS in addition to or instead of a gynecologic diagnosis.6 Among women given a diagnosis of endometriosis, 35% to 90% have been found to have IC/PBS as well.

FIGURE 1 Glomerulations are a common finding

Cystoscopy with hydrodistention often, but not always, reveals glomerulations (mucosal hemorrhages) in a patient who has interstitial cystitis.

Two screening tools may aid the diagnosis

IC/PBS is a clinical diagnosis, based on symptoms and signs. Although some controversy surrounds this statement, there is no question that we lack a gold-standard test to reliably make the diagnosis.

Two screening instruments are commonly used to identify patients in whom IC/PBS should be considered. One is the O’Leary-Sant questionnaire (TABLE 1), which incorporates two scales:

- the IC Symptom Index (ICSI)

- the IC Problem Index (ICPI).

The O’Leary-Sant questionnaire was not designed specifically to diagnose IC/PBS but to aid in its evaluation and management and to facilitate clinical research.

TABLE 1 The O’Leary Sant IC questionnaire

Please mark the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

TABLE 2

The Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Symptom Scale

Please circle the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1. | How many times do you go to the bathroom DURING THE DAY (to void or empty your bladder)? | 3-6 | 7-10 | 11-14 | 15-19 | 20 or more |

| 2. | How many times do you go to the bathroom AT NIGHT (to void or empty your bladder)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 or more |

| 3. | If you get up at night to void or empty your bladder, does it bother you? | Never | Mildly | Moderately | Severely | |

| 4. | Are you sexually active? No ___ Yes ___ | |||||

| 5. | If you are sexually active, do you now or have you ever had pain or symptoms during or after sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 6. | If you have pain with intercourse, does it make you avoid sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 7. | Do you have pain associated with your bladder or in your pelvis (lower abdomen, labia, vagina, urethra, perineum)? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 8. | Do you have urgency after voiding? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 9. | If you have pain, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 10. | Does your pain bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 11. | If you have urgency, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 12. | Does your urgency bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| PUR Score 0–35 | ||||||

In a busy gynecologic practice, routine use of one of these questionnaires can greatly facilitate identification of patients who may have IC/PBS.

Diagnosis can be straightforward—but often it isn’t

In many patients, diagnosis of IC/PBS is straightforward, with classic findings:

- pelvic pain

- urinary frequency (voiding every 1 or 2 hours)

- discomfort or increased pain (as opposed to a fear of losing urine) leading to urinary urge

- significant tenderness during single-digit palpation of the bladder at the time of pelvic examination

- nocturia in many cases.

Be aware that diagnosis can be more challenging when the patient is in the early course of the disease. About 90% of patients who have IC/PBS have only one symptom in the beginning—fewer than 10% experience the simultaneous onset of urgency, frequency, nocturia, and pain. The mean time from development of the initial symptom until manifestation of all symptoms ranges from 2 to 5 years.7 In about one third of patients, the initial symptom is urinary frequency and urgency preceding the onset of pain—but almost equal numbers of patients develop pelvic pain as a solitary symptom before the onset of any urinary symptoms.

Complicating matters is the fact that symptoms are often episodic early in the course of the disease. The episodic nature of symptoms often leads to multiple misdiagnoses such as urinary tract infection and recurrent or chronic cystitis. A history of empiric treatment of recurrent urinary tract infection without documentation of a positive culture is common in women who have IC/PBS. A patient who has early interstitial cystitis may respond to antibiotic treatment due to the natural waxing and waning of symptoms, the placebo effect, or an increase in fluid intake that usually accompanies antibiotic usage (dilute urine is less irritating to the bladder). Awareness of the possibility of IC/PBS in these patients is essential if diagnosis is to be made as early as possible.

Dyspareunia is another common symptom in patients who have IC/PBS. Pain during intercourse appears to arise from tenderness in the pelvic floor muscles as well as the bladder. It may also occur upon vaginal entry due to associated vulvar vestibulitis.8 In postmenopausal women, vulvovaginal atrophy may contribute to dyspareunia as well.

Also consider IC/PBS when a patient continues to experience pelvic pain after treatment of endometriosis or after hysterectomy. In one study, 80% of women who had persistent chronic pelvic pain after hysterectomy had interstitial cystitis.9 Among women who have endometriosis, we have found that 35% have IC/PBS (unpublished data). Chung reported that 85% of women who have endometriosis also have IC/PBS.10

Which diagnostic studies are useful?

To some extent, IC/PBS is a diagnosis of exclusion, as other possible causes of pelvic pain, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and nocturia must be excluded. Urinalysis and urine culture are essential tests in the evaluation of women suspected of having interstitial cystitis. Urinary tract infection must be excluded with a negative urine culture. If a patient has hematuria, urine cytology or cystoscopy is recommended to exclude malignancy. Urine cytology or cystoscopy is also recommended if the patient has a history of smoking (because of the strong association between bladder cancer and smoking) or is older than 50 years.

Some experts still insist that cystoscopic hydrodistention is necessary. Cystoscopy with hydrodistention under general or regional anesthesia has long been considered the “gold standard” diagnostic test for IC. Identification of a Hunner ulcer is pathognomonic, but it is an uncommon finding and one usually discovered only in advanced cases. More often, cystoscopy with hydrodistention in a patient who has IC reveals glomerulations, which are mucosal hemorrhages that exhibit a characteristic appearance upon second filling of the bladder (FIGURE 1).

The value of cystoscopy has recently been questioned because at least 10% of patients who have clear clinical evidence of interstitial cystitis have normal findings at the time of cystoscopic hydrodistention.11 Glomerulations have also been observed in asymptomatic patients after hydrodistention with as much as 950 mL of water. In at least one published study, glomerulations did not distinguish patients who had a clinical diagnosis of IC from asymptomatic women.12

The potassium sensitivity (parsons) test (PST) may be a useful diagnostic test for IC. It is based on the concept that patients who have the disease have a defective urothelium that allows cations to penetrate the bladder wall and depolarize the sensory C-fibers, generating lower urinary tract symptoms.13 An alternative explanation for this test may be that it identifies patients who have a hyperalgesic or allodynic bladder, whether or not there is a defect in the urothelium.

The test is performed by instilling 40 mL of sterile water into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is then asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The water is drained and 40 mL of a 0.4-molar solution of potassium chloride (40 mEq in 100 mL of water), containing a total of 16 mEq of potassium chloride, are instilled into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is again asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The test is positive when the patient reports a change of two points or more on the pain or urgency scale after instillation of potassium chloride solution.

The PST is negative in 96% of normal controls and positive in 70% to 80% of patients who have IC.14 Patients who have radiation cystitis or bacterial cystitis also have a positive response to the PST. Sensitivity of the test may decrease if the patient has recently been treated for IC, especially if the therapy involved dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or instillation of an anesthetic.

The PST can trigger the flare of severe symptoms in patients who have IC, so all women who have a positive test should receive a “rescue cocktail” after the potassium chloride solution is drained. Two of the most common rescue solutions are:

- 20,000 U of heparin mixed with 20 mL of 1% lidocaine

- a 15-mL mixture of 40,000 U of heparin, 8 mL of 2% lidocaine, and 3 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate.

The rescue cocktail usually reverses the urgency and pain brought on by potassium chloride.

A patient who has a high level of pain with IC may be unable to discern a change when potassium chloride solution is instilled, or she may be unable to tolerate the discomfort it causes. Instillation of an anesthetic agent into the bladder may be a useful diagnostic test in such a case. The rescue cocktail described above also provides an opportunity for patient and clinician to see whether her symptoms abate after introduction of the anesthetic agent.

Last, researchers have long sought a simple urinary biomarker that would be specific for IC, but none are available for routine clinical use.

Although the cause of interstitial cystitis is unknown, two main theories have developed to explain it. The popular, single end-organ theory, illustrated by the pathway with red arrows in FIGURE 2, holds that an injury or insult to the bladder is the cause. When that injury fails to heal completely, the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder is left with a defect, allowing leakage of urinary components, such as potassium, into the mucosa and submucosa. This leakage triggers an inflammatory reaction and activates nociceptors in the bladder, including nociceptors that do not usually respond to bladder distention and stimulation (so-called silent nociceptors). Activation of these nociceptors generates allodynia in the bladder, meaning that normal distention of the bladder becomes painful.

There is evidence that other pathways also lead to IC/PBS, as illustrated by the blue, bidirectional arrows. Other generators of pelvic pain, both visceral and somatic, can neurologically activate bladder nociceptors at the central level, creating “crosstalk” and leading to bladder pain and IC/PBS. In such cases, antidromic transmission (efferent transmission in afferent nerves) can lead to neurogenic bladder inflammation and contribute further to pelvic pain. Examples of pelvic pain syndromes thought to have links to IC/PBS include endometriosis, irritable bowel syndrome, and pelvic floor tension myalgia.

In addition, there is evidence that nonpelvic syndromes, such as fibromyalgia and migraine, can lead to central or peripheral sensitization that results in IC/PBS. That is, sensitization leads to chronic bladder pain from injury or stimulation that would otherwise not cause pain.

As these theories suggest, it is likely that more than one disease and one disease pathway are encompassed within the syndrome called IC/PBS. In the opening case, it appears that a severe urinary tract infection and persistent myofascial pain, and possibly endometriosis, may have been variables leading to the development of IC/PBS.

FIGURE 2 Pathways to pain

Part 2 of this article reviews components of the treatment of IC/PBS and their stepwise application.

CASE: A complex presentation, a deferred diagnosis

J. M. is a 25-year-old white nulliparous woman who visits our office reporting pelvic pain. She says the pain began when she was 16 years old, when she was taken to the emergency room for what was thought to be appendicitis. There, she was given a diagnosis of acute, severe cystitis.

Several months later, J. M. began experiencing dysmenorrhea and was given an additional diagnosis of endometriosis, for which she was treated both medically and surgically.

By the time she visits our office, J. M.’s pain has become a daily occurrence that ranges in intensity from 1 to 10 on the numerical rating scale (10, most severe). The pain is mostly localized to the right lower quadrant (RLQ) and is exacerbated by menses and intercourse. She reports mild urinary urgency, voiding every 5 to 6 hours, and one to two episodes of nocturia daily. She has no gastrointestinal symptoms.

We identify four active myofascial trigger points in the RLQ, as well as uterine and adnexal tenderness upon examination. A diagnostic laparoscopy and histology confirm endometriosis, but only three lesions are observed.

After the operation, J. M. is given 5 mg of norethindrone acetate daily to ease the pain that is thought to arise from her endometriosis. Because the pain persists, we add injections of 0.25% bupivacaine at the myofascial trigger points every 4 to 6 weeks. Her pain diminishes for as long as 6 weeks after each injection.

Fifteen months after the laparoscopy, J. M. complains of the need to void every 2 hours because of discomfort and pain and continued nocturia. This time, she experiences no pain at the trigger points, but her bladder is exquisitely tender upon palpation. We order urinalysis and culture, both of which are negative. A potassium sensitivity test is markedly positive, however, confirming the suspected diagnosis of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome.

Could this diagnosis have been made earlier?

J. M. is a real patient in our clinical practice. Her case illustrates the challenges a gynecologist faces in diagnosing chronic pelvic pain. In retrospect, it is apparent that endometriosis was not a major generator of her pain. Instead, abdominal wall myofascial pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) were the major generators. Although her myofascial pain appeared to respond to treatment with bupivacaine, she began to clearly manifest symptoms of IC/PBS.

This article describes the often-thorny diagnosis of IC/PBS and discusses the theories that have been proposed to explain the syndrome. In Part 2 of this article, the many components of management are discussed.

Early diagnosis and treatment appear to improve the response to treatment and prevent progression to severe disease. Because the gynecologist is the physician who commonly sees women at the onset of chronic pelvic pain, he or she is ideally positioned to diagnose this disorder early in its course.

Although interstitial cystitis (IC) occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or malignancy, some pathology may become apparent during cystoscopy with hydrodistention. Potential findings include:

(A) glomerulations, or hemorrhages of the bladder mucosa

(B) damage to the urothelium

(C) Hunner’s ulcer, a defect of the urothelium that is pathognomonic for IC but uncommon.

What is IC/PBS?

This disorder consists of pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort related to the bladder and associated with a persistent urge to void. It occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or other pathology such as bladder carcinoma or cystitis induced by radiation or medication.

The term interstitial cystitis appears to have originated with New York gynecologist Alexander Johnston Chalmers Skene in 1887. Traditionally, interstitial cystitis was diagnosed only in severe cases in which bladder capacity was greatly reduced and Hunner’s ulcer, a fissuring of the bladder mucosa, was present at cystoscopy.1

In 1978, Messing and Stamey broadened the diagnosis of IC to include glomerulations at cystoscopy (FIGURE 1).2 It is now clear that the bladder can be a source of pelvic pain without these clinical findings. As a result, nomenclature has become confusing. Terms in current use include painful bladder syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and a combination of these names. Confusing matters further is the fact that these terms are not always used interchangeably.

Despite controversy over nomenclature and diagnostic criteria, there is no uncertainty that the lives of women who have IC/PBS are significantly altered by the disease. It adversely affects leisure activity, family relationships, and travel in 70% to 94% of patients.3 Suicidal thoughts are three to four times more likely in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population. Quality of life is markedly decreased across all domains, and depressive symptoms are much more common in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population.4

IC/PBS appears to affect women more often than men, and it is a frequent diagnosis among women who have chronic pelvic pain. For example, in a primary care population of women 15 to 73 years old who had chronic pelvic pain, about 30% were determined to have pain of urologic origin.5 It has been suggested, based on symptoms of urgency-frequency and a positive potassium sensitivity test, that approximately 85% of women who see a gynecologist for chronic pelvic pain have IC/PBS in addition to or instead of a gynecologic diagnosis.6 Among women given a diagnosis of endometriosis, 35% to 90% have been found to have IC/PBS as well.

FIGURE 1 Glomerulations are a common finding

Cystoscopy with hydrodistention often, but not always, reveals glomerulations (mucosal hemorrhages) in a patient who has interstitial cystitis.

Two screening tools may aid the diagnosis

IC/PBS is a clinical diagnosis, based on symptoms and signs. Although some controversy surrounds this statement, there is no question that we lack a gold-standard test to reliably make the diagnosis.

Two screening instruments are commonly used to identify patients in whom IC/PBS should be considered. One is the O’Leary-Sant questionnaire (TABLE 1), which incorporates two scales:

- the IC Symptom Index (ICSI)

- the IC Problem Index (ICPI).

The O’Leary-Sant questionnaire was not designed specifically to diagnose IC/PBS but to aid in its evaluation and management and to facilitate clinical research.

TABLE 1 The O’Leary Sant IC questionnaire

Please mark the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

TABLE 2

The Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Symptom Scale

Please circle the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1. | How many times do you go to the bathroom DURING THE DAY (to void or empty your bladder)? | 3-6 | 7-10 | 11-14 | 15-19 | 20 or more |

| 2. | How many times do you go to the bathroom AT NIGHT (to void or empty your bladder)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 or more |

| 3. | If you get up at night to void or empty your bladder, does it bother you? | Never | Mildly | Moderately | Severely | |

| 4. | Are you sexually active? No ___ Yes ___ | |||||

| 5. | If you are sexually active, do you now or have you ever had pain or symptoms during or after sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 6. | If you have pain with intercourse, does it make you avoid sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 7. | Do you have pain associated with your bladder or in your pelvis (lower abdomen, labia, vagina, urethra, perineum)? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 8. | Do you have urgency after voiding? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 9. | If you have pain, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 10. | Does your pain bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 11. | If you have urgency, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 12. | Does your urgency bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| PUR Score 0–35 | ||||||

In a busy gynecologic practice, routine use of one of these questionnaires can greatly facilitate identification of patients who may have IC/PBS.

Diagnosis can be straightforward—but often it isn’t

In many patients, diagnosis of IC/PBS is straightforward, with classic findings:

- pelvic pain

- urinary frequency (voiding every 1 or 2 hours)

- discomfort or increased pain (as opposed to a fear of losing urine) leading to urinary urge

- significant tenderness during single-digit palpation of the bladder at the time of pelvic examination

- nocturia in many cases.

Be aware that diagnosis can be more challenging when the patient is in the early course of the disease. About 90% of patients who have IC/PBS have only one symptom in the beginning—fewer than 10% experience the simultaneous onset of urgency, frequency, nocturia, and pain. The mean time from development of the initial symptom until manifestation of all symptoms ranges from 2 to 5 years.7 In about one third of patients, the initial symptom is urinary frequency and urgency preceding the onset of pain—but almost equal numbers of patients develop pelvic pain as a solitary symptom before the onset of any urinary symptoms.

Complicating matters is the fact that symptoms are often episodic early in the course of the disease. The episodic nature of symptoms often leads to multiple misdiagnoses such as urinary tract infection and recurrent or chronic cystitis. A history of empiric treatment of recurrent urinary tract infection without documentation of a positive culture is common in women who have IC/PBS. A patient who has early interstitial cystitis may respond to antibiotic treatment due to the natural waxing and waning of symptoms, the placebo effect, or an increase in fluid intake that usually accompanies antibiotic usage (dilute urine is less irritating to the bladder). Awareness of the possibility of IC/PBS in these patients is essential if diagnosis is to be made as early as possible.

Dyspareunia is another common symptom in patients who have IC/PBS. Pain during intercourse appears to arise from tenderness in the pelvic floor muscles as well as the bladder. It may also occur upon vaginal entry due to associated vulvar vestibulitis.8 In postmenopausal women, vulvovaginal atrophy may contribute to dyspareunia as well.

Also consider IC/PBS when a patient continues to experience pelvic pain after treatment of endometriosis or after hysterectomy. In one study, 80% of women who had persistent chronic pelvic pain after hysterectomy had interstitial cystitis.9 Among women who have endometriosis, we have found that 35% have IC/PBS (unpublished data). Chung reported that 85% of women who have endometriosis also have IC/PBS.10

Which diagnostic studies are useful?

To some extent, IC/PBS is a diagnosis of exclusion, as other possible causes of pelvic pain, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and nocturia must be excluded. Urinalysis and urine culture are essential tests in the evaluation of women suspected of having interstitial cystitis. Urinary tract infection must be excluded with a negative urine culture. If a patient has hematuria, urine cytology or cystoscopy is recommended to exclude malignancy. Urine cytology or cystoscopy is also recommended if the patient has a history of smoking (because of the strong association between bladder cancer and smoking) or is older than 50 years.

Some experts still insist that cystoscopic hydrodistention is necessary. Cystoscopy with hydrodistention under general or regional anesthesia has long been considered the “gold standard” diagnostic test for IC. Identification of a Hunner ulcer is pathognomonic, but it is an uncommon finding and one usually discovered only in advanced cases. More often, cystoscopy with hydrodistention in a patient who has IC reveals glomerulations, which are mucosal hemorrhages that exhibit a characteristic appearance upon second filling of the bladder (FIGURE 1).

The value of cystoscopy has recently been questioned because at least 10% of patients who have clear clinical evidence of interstitial cystitis have normal findings at the time of cystoscopic hydrodistention.11 Glomerulations have also been observed in asymptomatic patients after hydrodistention with as much as 950 mL of water. In at least one published study, glomerulations did not distinguish patients who had a clinical diagnosis of IC from asymptomatic women.12

The potassium sensitivity (parsons) test (PST) may be a useful diagnostic test for IC. It is based on the concept that patients who have the disease have a defective urothelium that allows cations to penetrate the bladder wall and depolarize the sensory C-fibers, generating lower urinary tract symptoms.13 An alternative explanation for this test may be that it identifies patients who have a hyperalgesic or allodynic bladder, whether or not there is a defect in the urothelium.

The test is performed by instilling 40 mL of sterile water into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is then asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The water is drained and 40 mL of a 0.4-molar solution of potassium chloride (40 mEq in 100 mL of water), containing a total of 16 mEq of potassium chloride, are instilled into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is again asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The test is positive when the patient reports a change of two points or more on the pain or urgency scale after instillation of potassium chloride solution.

The PST is negative in 96% of normal controls and positive in 70% to 80% of patients who have IC.14 Patients who have radiation cystitis or bacterial cystitis also have a positive response to the PST. Sensitivity of the test may decrease if the patient has recently been treated for IC, especially if the therapy involved dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or instillation of an anesthetic.

The PST can trigger the flare of severe symptoms in patients who have IC, so all women who have a positive test should receive a “rescue cocktail” after the potassium chloride solution is drained. Two of the most common rescue solutions are:

- 20,000 U of heparin mixed with 20 mL of 1% lidocaine

- a 15-mL mixture of 40,000 U of heparin, 8 mL of 2% lidocaine, and 3 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate.

The rescue cocktail usually reverses the urgency and pain brought on by potassium chloride.

A patient who has a high level of pain with IC may be unable to discern a change when potassium chloride solution is instilled, or she may be unable to tolerate the discomfort it causes. Instillation of an anesthetic agent into the bladder may be a useful diagnostic test in such a case. The rescue cocktail described above also provides an opportunity for patient and clinician to see whether her symptoms abate after introduction of the anesthetic agent.

Last, researchers have long sought a simple urinary biomarker that would be specific for IC, but none are available for routine clinical use.

Although the cause of interstitial cystitis is unknown, two main theories have developed to explain it. The popular, single end-organ theory, illustrated by the pathway with red arrows in FIGURE 2, holds that an injury or insult to the bladder is the cause. When that injury fails to heal completely, the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder is left with a defect, allowing leakage of urinary components, such as potassium, into the mucosa and submucosa. This leakage triggers an inflammatory reaction and activates nociceptors in the bladder, including nociceptors that do not usually respond to bladder distention and stimulation (so-called silent nociceptors). Activation of these nociceptors generates allodynia in the bladder, meaning that normal distention of the bladder becomes painful.

There is evidence that other pathways also lead to IC/PBS, as illustrated by the blue, bidirectional arrows. Other generators of pelvic pain, both visceral and somatic, can neurologically activate bladder nociceptors at the central level, creating “crosstalk” and leading to bladder pain and IC/PBS. In such cases, antidromic transmission (efferent transmission in afferent nerves) can lead to neurogenic bladder inflammation and contribute further to pelvic pain. Examples of pelvic pain syndromes thought to have links to IC/PBS include endometriosis, irritable bowel syndrome, and pelvic floor tension myalgia.

In addition, there is evidence that nonpelvic syndromes, such as fibromyalgia and migraine, can lead to central or peripheral sensitization that results in IC/PBS. That is, sensitization leads to chronic bladder pain from injury or stimulation that would otherwise not cause pain.

As these theories suggest, it is likely that more than one disease and one disease pathway are encompassed within the syndrome called IC/PBS. In the opening case, it appears that a severe urinary tract infection and persistent myofascial pain, and possibly endometriosis, may have been variables leading to the development of IC/PBS.

FIGURE 2 Pathways to pain

Part 2 of this article reviews components of the treatment of IC/PBS and their stepwise application.

1. Hunner GL. A rare type of bladder ulcer in women: report of cases. Boston Med Surg. 1915;172.-

2. Messing EM, Stamey TA. Interstitial cystitis: early diagnosis, pathology, and treatment. Urology. 1978;12(4):381-392.

3. Koziol JA, Clark DC, Gittes RF, Tan EM. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: a survey of 374 patients. J Urol. 1993;149(3):465-469.

4. Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Hoffman A, Kreder KJ. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2002;167(4):1763-1767.

5. Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(11):1149-1155.

6. Parsons CL, Bullen M, Kahn BS, Stanford EJ, Willems JJ. Gynecologic presentation of interstitial cystitis as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98 (1):127-132.

7. Driscoll A, Teichman JM. How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol. 2001;166(6):2118-2120.

8. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996-1002.

9. Chung MK. Interstitial cystitis in persistent posthysterectomy chronic pelvic pain. JSLS. 2004;8(4):329-333.

10. Chung MK, Chung RR, Gordon D, Jennings C. The evil twins of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: endometriosis and interstitial cystitis. JSLS. 2002;6(4):311-314.

11. Messing EM. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1987;29(4 suppl):4-7.

12. Waxman JA, Sulak PJ, Kuehl TJ. Cystoscopic findings consistent with interstitial cystitis in normal women undergoing tubal ligation. J Urol. 1998;160(5):1663-1667.

13. Parsons CL, Zupkas P, Parsons JK. Intravesical potassium sensitivity in patients with interstitial cystitis and urethral syndrome. Urology. 2001;57(3):428-433.

14. Parsons CL, Stein PC, Bidair M, Lebow D. Abnormal sensitivity to intravesical potassium in interstitial cystitis and radiation cystitis. Neurourol Urodyn. 1994;13(5):515-520.

1. Hunner GL. A rare type of bladder ulcer in women: report of cases. Boston Med Surg. 1915;172.-

2. Messing EM, Stamey TA. Interstitial cystitis: early diagnosis, pathology, and treatment. Urology. 1978;12(4):381-392.

3. Koziol JA, Clark DC, Gittes RF, Tan EM. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: a survey of 374 patients. J Urol. 1993;149(3):465-469.

4. Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Hoffman A, Kreder KJ. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2002;167(4):1763-1767.

5. Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(11):1149-1155.

6. Parsons CL, Bullen M, Kahn BS, Stanford EJ, Willems JJ. Gynecologic presentation of interstitial cystitis as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98 (1):127-132.

7. Driscoll A, Teichman JM. How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol. 2001;166(6):2118-2120.

8. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996-1002.

9. Chung MK. Interstitial cystitis in persistent posthysterectomy chronic pelvic pain. JSLS. 2004;8(4):329-333.

10. Chung MK, Chung RR, Gordon D, Jennings C. The evil twins of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: endometriosis and interstitial cystitis. JSLS. 2002;6(4):311-314.

11. Messing EM. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1987;29(4 suppl):4-7.

12. Waxman JA, Sulak PJ, Kuehl TJ. Cystoscopic findings consistent with interstitial cystitis in normal women undergoing tubal ligation. J Urol. 1998;160(5):1663-1667.

13. Parsons CL, Zupkas P, Parsons JK. Intravesical potassium sensitivity in patients with interstitial cystitis and urethral syndrome. Urology. 2001;57(3):428-433.

14. Parsons CL, Stein PC, Bidair M, Lebow D. Abnormal sensitivity to intravesical potassium in interstitial cystitis and radiation cystitis. Neurourol Urodyn. 1994;13(5):515-520.