User login

INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS: The gynecologist’s guide to diagnosis

CASE: A complex presentation, a deferred diagnosis

J. M. is a 25-year-old white nulliparous woman who visits our office reporting pelvic pain. She says the pain began when she was 16 years old, when she was taken to the emergency room for what was thought to be appendicitis. There, she was given a diagnosis of acute, severe cystitis.

Several months later, J. M. began experiencing dysmenorrhea and was given an additional diagnosis of endometriosis, for which she was treated both medically and surgically.

By the time she visits our office, J. M.’s pain has become a daily occurrence that ranges in intensity from 1 to 10 on the numerical rating scale (10, most severe). The pain is mostly localized to the right lower quadrant (RLQ) and is exacerbated by menses and intercourse. She reports mild urinary urgency, voiding every 5 to 6 hours, and one to two episodes of nocturia daily. She has no gastrointestinal symptoms.

We identify four active myofascial trigger points in the RLQ, as well as uterine and adnexal tenderness upon examination. A diagnostic laparoscopy and histology confirm endometriosis, but only three lesions are observed.

After the operation, J. M. is given 5 mg of norethindrone acetate daily to ease the pain that is thought to arise from her endometriosis. Because the pain persists, we add injections of 0.25% bupivacaine at the myofascial trigger points every 4 to 6 weeks. Her pain diminishes for as long as 6 weeks after each injection.

Fifteen months after the laparoscopy, J. M. complains of the need to void every 2 hours because of discomfort and pain and continued nocturia. This time, she experiences no pain at the trigger points, but her bladder is exquisitely tender upon palpation. We order urinalysis and culture, both of which are negative. A potassium sensitivity test is markedly positive, however, confirming the suspected diagnosis of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome.

Could this diagnosis have been made earlier?

J. M. is a real patient in our clinical practice. Her case illustrates the challenges a gynecologist faces in diagnosing chronic pelvic pain. In retrospect, it is apparent that endometriosis was not a major generator of her pain. Instead, abdominal wall myofascial pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) were the major generators. Although her myofascial pain appeared to respond to treatment with bupivacaine, she began to clearly manifest symptoms of IC/PBS.

This article describes the often-thorny diagnosis of IC/PBS and discusses the theories that have been proposed to explain the syndrome. In Part 2 of this article, the many components of management are discussed.

Early diagnosis and treatment appear to improve the response to treatment and prevent progression to severe disease. Because the gynecologist is the physician who commonly sees women at the onset of chronic pelvic pain, he or she is ideally positioned to diagnose this disorder early in its course.

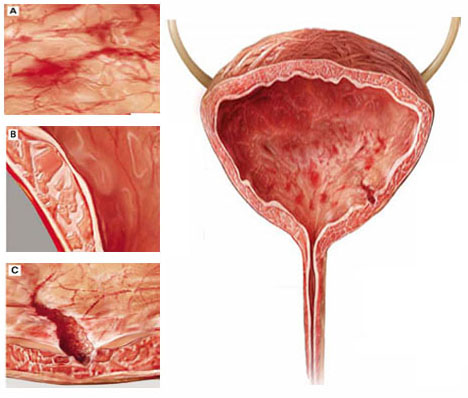

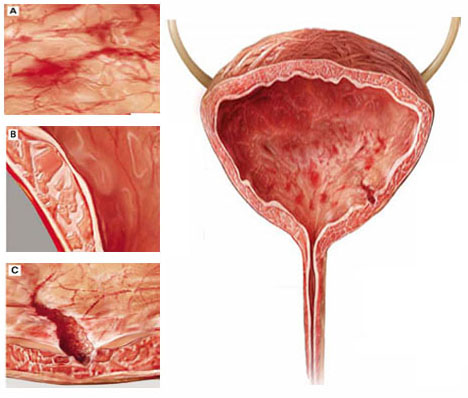

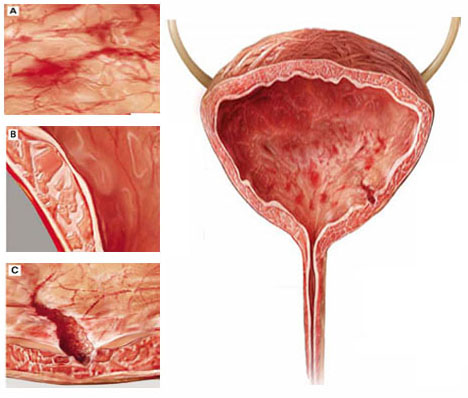

Although interstitial cystitis (IC) occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or malignancy, some pathology may become apparent during cystoscopy with hydrodistention. Potential findings include:

(A) glomerulations, or hemorrhages of the bladder mucosa

(B) damage to the urothelium

(C) Hunner’s ulcer, a defect of the urothelium that is pathognomonic for IC but uncommon.

What is IC/PBS?

This disorder consists of pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort related to the bladder and associated with a persistent urge to void. It occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or other pathology such as bladder carcinoma or cystitis induced by radiation or medication.

The term interstitial cystitis appears to have originated with New York gynecologist Alexander Johnston Chalmers Skene in 1887. Traditionally, interstitial cystitis was diagnosed only in severe cases in which bladder capacity was greatly reduced and Hunner’s ulcer, a fissuring of the bladder mucosa, was present at cystoscopy.1

In 1978, Messing and Stamey broadened the diagnosis of IC to include glomerulations at cystoscopy (FIGURE 1).2 It is now clear that the bladder can be a source of pelvic pain without these clinical findings. As a result, nomenclature has become confusing. Terms in current use include painful bladder syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and a combination of these names. Confusing matters further is the fact that these terms are not always used interchangeably.

Despite controversy over nomenclature and diagnostic criteria, there is no uncertainty that the lives of women who have IC/PBS are significantly altered by the disease. It adversely affects leisure activity, family relationships, and travel in 70% to 94% of patients.3 Suicidal thoughts are three to four times more likely in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population. Quality of life is markedly decreased across all domains, and depressive symptoms are much more common in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population.4

IC/PBS appears to affect women more often than men, and it is a frequent diagnosis among women who have chronic pelvic pain. For example, in a primary care population of women 15 to 73 years old who had chronic pelvic pain, about 30% were determined to have pain of urologic origin.5 It has been suggested, based on symptoms of urgency-frequency and a positive potassium sensitivity test, that approximately 85% of women who see a gynecologist for chronic pelvic pain have IC/PBS in addition to or instead of a gynecologic diagnosis.6 Among women given a diagnosis of endometriosis, 35% to 90% have been found to have IC/PBS as well.

FIGURE 1 Glomerulations are a common finding

Cystoscopy with hydrodistention often, but not always, reveals glomerulations (mucosal hemorrhages) in a patient who has interstitial cystitis.

Two screening tools may aid the diagnosis

IC/PBS is a clinical diagnosis, based on symptoms and signs. Although some controversy surrounds this statement, there is no question that we lack a gold-standard test to reliably make the diagnosis.

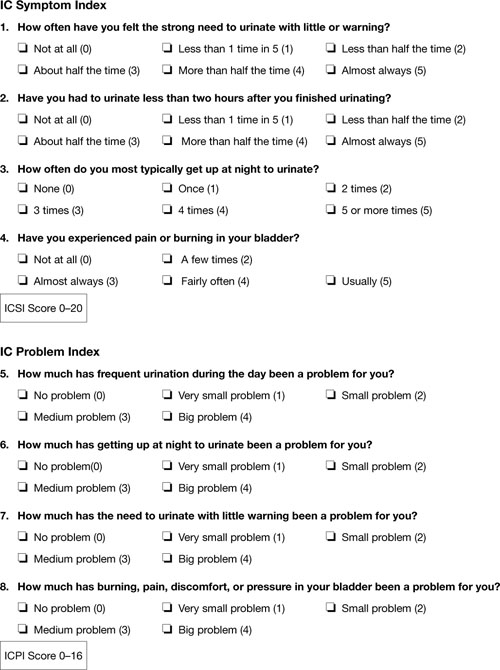

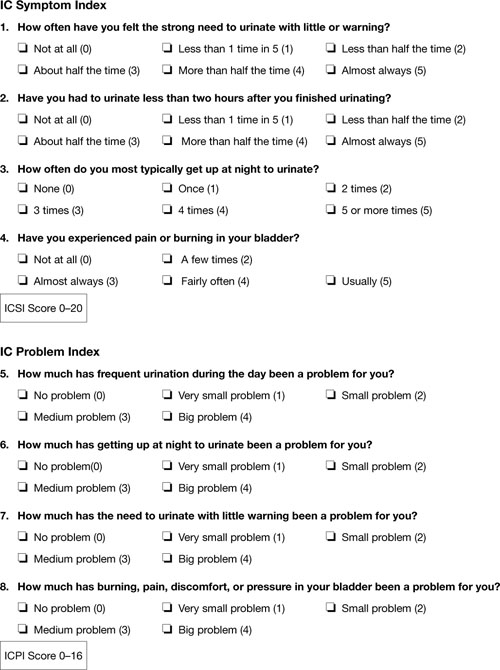

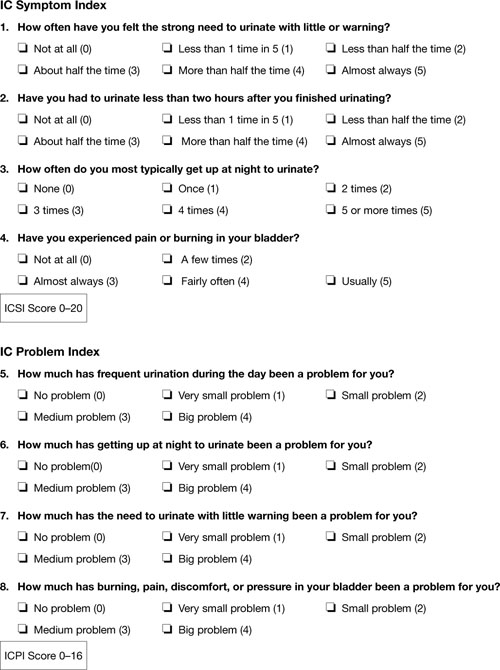

Two screening instruments are commonly used to identify patients in whom IC/PBS should be considered. One is the O’Leary-Sant questionnaire (TABLE 1), which incorporates two scales:

- the IC Symptom Index (ICSI)

- the IC Problem Index (ICPI).

The O’Leary-Sant questionnaire was not designed specifically to diagnose IC/PBS but to aid in its evaluation and management and to facilitate clinical research.

TABLE 1 The O’Leary Sant IC questionnaire

Please mark the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

TABLE 2

The Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Symptom Scale

Please circle the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1. | How many times do you go to the bathroom DURING THE DAY (to void or empty your bladder)? | 3-6 | 7-10 | 11-14 | 15-19 | 20 or more |

| 2. | How many times do you go to the bathroom AT NIGHT (to void or empty your bladder)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 or more |

| 3. | If you get up at night to void or empty your bladder, does it bother you? | Never | Mildly | Moderately | Severely | |

| 4. | Are you sexually active? No ___ Yes ___ | |||||

| 5. | If you are sexually active, do you now or have you ever had pain or symptoms during or after sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 6. | If you have pain with intercourse, does it make you avoid sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 7. | Do you have pain associated with your bladder or in your pelvis (lower abdomen, labia, vagina, urethra, perineum)? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 8. | Do you have urgency after voiding? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 9. | If you have pain, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 10. | Does your pain bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 11. | If you have urgency, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 12. | Does your urgency bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| PUR Score 0–35 | ||||||

In a busy gynecologic practice, routine use of one of these questionnaires can greatly facilitate identification of patients who may have IC/PBS.

Diagnosis can be straightforward—but often it isn’t

In many patients, diagnosis of IC/PBS is straightforward, with classic findings:

- pelvic pain

- urinary frequency (voiding every 1 or 2 hours)

- discomfort or increased pain (as opposed to a fear of losing urine) leading to urinary urge

- significant tenderness during single-digit palpation of the bladder at the time of pelvic examination

- nocturia in many cases.

Be aware that diagnosis can be more challenging when the patient is in the early course of the disease. About 90% of patients who have IC/PBS have only one symptom in the beginning—fewer than 10% experience the simultaneous onset of urgency, frequency, nocturia, and pain. The mean time from development of the initial symptom until manifestation of all symptoms ranges from 2 to 5 years.7 In about one third of patients, the initial symptom is urinary frequency and urgency preceding the onset of pain—but almost equal numbers of patients develop pelvic pain as a solitary symptom before the onset of any urinary symptoms.

Complicating matters is the fact that symptoms are often episodic early in the course of the disease. The episodic nature of symptoms often leads to multiple misdiagnoses such as urinary tract infection and recurrent or chronic cystitis. A history of empiric treatment of recurrent urinary tract infection without documentation of a positive culture is common in women who have IC/PBS. A patient who has early interstitial cystitis may respond to antibiotic treatment due to the natural waxing and waning of symptoms, the placebo effect, or an increase in fluid intake that usually accompanies antibiotic usage (dilute urine is less irritating to the bladder). Awareness of the possibility of IC/PBS in these patients is essential if diagnosis is to be made as early as possible.

Dyspareunia is another common symptom in patients who have IC/PBS. Pain during intercourse appears to arise from tenderness in the pelvic floor muscles as well as the bladder. It may also occur upon vaginal entry due to associated vulvar vestibulitis.8 In postmenopausal women, vulvovaginal atrophy may contribute to dyspareunia as well.

Also consider IC/PBS when a patient continues to experience pelvic pain after treatment of endometriosis or after hysterectomy. In one study, 80% of women who had persistent chronic pelvic pain after hysterectomy had interstitial cystitis.9 Among women who have endometriosis, we have found that 35% have IC/PBS (unpublished data). Chung reported that 85% of women who have endometriosis also have IC/PBS.10

Which diagnostic studies are useful?

To some extent, IC/PBS is a diagnosis of exclusion, as other possible causes of pelvic pain, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and nocturia must be excluded. Urinalysis and urine culture are essential tests in the evaluation of women suspected of having interstitial cystitis. Urinary tract infection must be excluded with a negative urine culture. If a patient has hematuria, urine cytology or cystoscopy is recommended to exclude malignancy. Urine cytology or cystoscopy is also recommended if the patient has a history of smoking (because of the strong association between bladder cancer and smoking) or is older than 50 years.

Some experts still insist that cystoscopic hydrodistention is necessary. Cystoscopy with hydrodistention under general or regional anesthesia has long been considered the “gold standard” diagnostic test for IC. Identification of a Hunner ulcer is pathognomonic, but it is an uncommon finding and one usually discovered only in advanced cases. More often, cystoscopy with hydrodistention in a patient who has IC reveals glomerulations, which are mucosal hemorrhages that exhibit a characteristic appearance upon second filling of the bladder (FIGURE 1).

The value of cystoscopy has recently been questioned because at least 10% of patients who have clear clinical evidence of interstitial cystitis have normal findings at the time of cystoscopic hydrodistention.11 Glomerulations have also been observed in asymptomatic patients after hydrodistention with as much as 950 mL of water. In at least one published study, glomerulations did not distinguish patients who had a clinical diagnosis of IC from asymptomatic women.12

The potassium sensitivity (parsons) test (PST) may be a useful diagnostic test for IC. It is based on the concept that patients who have the disease have a defective urothelium that allows cations to penetrate the bladder wall and depolarize the sensory C-fibers, generating lower urinary tract symptoms.13 An alternative explanation for this test may be that it identifies patients who have a hyperalgesic or allodynic bladder, whether or not there is a defect in the urothelium.

The test is performed by instilling 40 mL of sterile water into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is then asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The water is drained and 40 mL of a 0.4-molar solution of potassium chloride (40 mEq in 100 mL of water), containing a total of 16 mEq of potassium chloride, are instilled into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is again asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The test is positive when the patient reports a change of two points or more on the pain or urgency scale after instillation of potassium chloride solution.

The PST is negative in 96% of normal controls and positive in 70% to 80% of patients who have IC.14 Patients who have radiation cystitis or bacterial cystitis also have a positive response to the PST. Sensitivity of the test may decrease if the patient has recently been treated for IC, especially if the therapy involved dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or instillation of an anesthetic.

The PST can trigger the flare of severe symptoms in patients who have IC, so all women who have a positive test should receive a “rescue cocktail” after the potassium chloride solution is drained. Two of the most common rescue solutions are:

- 20,000 U of heparin mixed with 20 mL of 1% lidocaine

- a 15-mL mixture of 40,000 U of heparin, 8 mL of 2% lidocaine, and 3 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate.

The rescue cocktail usually reverses the urgency and pain brought on by potassium chloride.

A patient who has a high level of pain with IC may be unable to discern a change when potassium chloride solution is instilled, or she may be unable to tolerate the discomfort it causes. Instillation of an anesthetic agent into the bladder may be a useful diagnostic test in such a case. The rescue cocktail described above also provides an opportunity for patient and clinician to see whether her symptoms abate after introduction of the anesthetic agent.

Last, researchers have long sought a simple urinary biomarker that would be specific for IC, but none are available for routine clinical use.

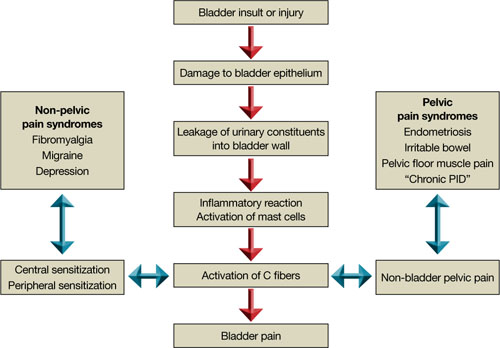

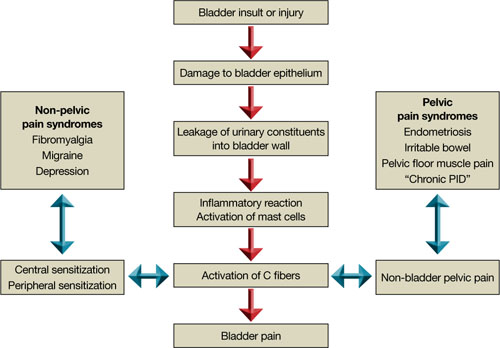

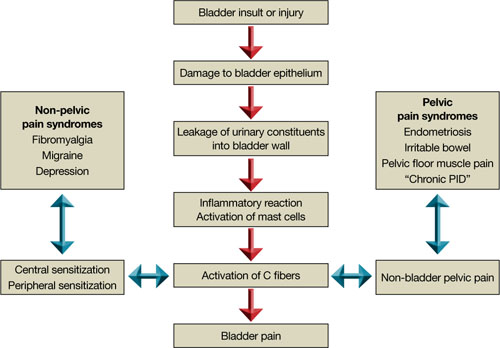

Although the cause of interstitial cystitis is unknown, two main theories have developed to explain it. The popular, single end-organ theory, illustrated by the pathway with red arrows in FIGURE 2, holds that an injury or insult to the bladder is the cause. When that injury fails to heal completely, the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder is left with a defect, allowing leakage of urinary components, such as potassium, into the mucosa and submucosa. This leakage triggers an inflammatory reaction and activates nociceptors in the bladder, including nociceptors that do not usually respond to bladder distention and stimulation (so-called silent nociceptors). Activation of these nociceptors generates allodynia in the bladder, meaning that normal distention of the bladder becomes painful.

There is evidence that other pathways also lead to IC/PBS, as illustrated by the blue, bidirectional arrows. Other generators of pelvic pain, both visceral and somatic, can neurologically activate bladder nociceptors at the central level, creating “crosstalk” and leading to bladder pain and IC/PBS. In such cases, antidromic transmission (efferent transmission in afferent nerves) can lead to neurogenic bladder inflammation and contribute further to pelvic pain. Examples of pelvic pain syndromes thought to have links to IC/PBS include endometriosis, irritable bowel syndrome, and pelvic floor tension myalgia.

In addition, there is evidence that nonpelvic syndromes, such as fibromyalgia and migraine, can lead to central or peripheral sensitization that results in IC/PBS. That is, sensitization leads to chronic bladder pain from injury or stimulation that would otherwise not cause pain.

As these theories suggest, it is likely that more than one disease and one disease pathway are encompassed within the syndrome called IC/PBS. In the opening case, it appears that a severe urinary tract infection and persistent myofascial pain, and possibly endometriosis, may have been variables leading to the development of IC/PBS.

FIGURE 2 Pathways to pain

Part 2 of this article reviews components of the treatment of IC/PBS and their stepwise application.

1. Hunner GL. A rare type of bladder ulcer in women: report of cases. Boston Med Surg. 1915;172.-

2. Messing EM, Stamey TA. Interstitial cystitis: early diagnosis, pathology, and treatment. Urology. 1978;12(4):381-392.

3. Koziol JA, Clark DC, Gittes RF, Tan EM. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: a survey of 374 patients. J Urol. 1993;149(3):465-469.

4. Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Hoffman A, Kreder KJ. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2002;167(4):1763-1767.

5. Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(11):1149-1155.

6. Parsons CL, Bullen M, Kahn BS, Stanford EJ, Willems JJ. Gynecologic presentation of interstitial cystitis as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98 (1):127-132.

7. Driscoll A, Teichman JM. How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol. 2001;166(6):2118-2120.

8. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996-1002.

9. Chung MK. Interstitial cystitis in persistent posthysterectomy chronic pelvic pain. JSLS. 2004;8(4):329-333.

10. Chung MK, Chung RR, Gordon D, Jennings C. The evil twins of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: endometriosis and interstitial cystitis. JSLS. 2002;6(4):311-314.

11. Messing EM. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1987;29(4 suppl):4-7.

12. Waxman JA, Sulak PJ, Kuehl TJ. Cystoscopic findings consistent with interstitial cystitis in normal women undergoing tubal ligation. J Urol. 1998;160(5):1663-1667.

13. Parsons CL, Zupkas P, Parsons JK. Intravesical potassium sensitivity in patients with interstitial cystitis and urethral syndrome. Urology. 2001;57(3):428-433.

14. Parsons CL, Stein PC, Bidair M, Lebow D. Abnormal sensitivity to intravesical potassium in interstitial cystitis and radiation cystitis. Neurourol Urodyn. 1994;13(5):515-520.

CASE: A complex presentation, a deferred diagnosis

J. M. is a 25-year-old white nulliparous woman who visits our office reporting pelvic pain. She says the pain began when she was 16 years old, when she was taken to the emergency room for what was thought to be appendicitis. There, she was given a diagnosis of acute, severe cystitis.

Several months later, J. M. began experiencing dysmenorrhea and was given an additional diagnosis of endometriosis, for which she was treated both medically and surgically.

By the time she visits our office, J. M.’s pain has become a daily occurrence that ranges in intensity from 1 to 10 on the numerical rating scale (10, most severe). The pain is mostly localized to the right lower quadrant (RLQ) and is exacerbated by menses and intercourse. She reports mild urinary urgency, voiding every 5 to 6 hours, and one to two episodes of nocturia daily. She has no gastrointestinal symptoms.

We identify four active myofascial trigger points in the RLQ, as well as uterine and adnexal tenderness upon examination. A diagnostic laparoscopy and histology confirm endometriosis, but only three lesions are observed.

After the operation, J. M. is given 5 mg of norethindrone acetate daily to ease the pain that is thought to arise from her endometriosis. Because the pain persists, we add injections of 0.25% bupivacaine at the myofascial trigger points every 4 to 6 weeks. Her pain diminishes for as long as 6 weeks after each injection.

Fifteen months after the laparoscopy, J. M. complains of the need to void every 2 hours because of discomfort and pain and continued nocturia. This time, she experiences no pain at the trigger points, but her bladder is exquisitely tender upon palpation. We order urinalysis and culture, both of which are negative. A potassium sensitivity test is markedly positive, however, confirming the suspected diagnosis of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome.

Could this diagnosis have been made earlier?

J. M. is a real patient in our clinical practice. Her case illustrates the challenges a gynecologist faces in diagnosing chronic pelvic pain. In retrospect, it is apparent that endometriosis was not a major generator of her pain. Instead, abdominal wall myofascial pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) were the major generators. Although her myofascial pain appeared to respond to treatment with bupivacaine, she began to clearly manifest symptoms of IC/PBS.

This article describes the often-thorny diagnosis of IC/PBS and discusses the theories that have been proposed to explain the syndrome. In Part 2 of this article, the many components of management are discussed.

Early diagnosis and treatment appear to improve the response to treatment and prevent progression to severe disease. Because the gynecologist is the physician who commonly sees women at the onset of chronic pelvic pain, he or she is ideally positioned to diagnose this disorder early in its course.

Although interstitial cystitis (IC) occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or malignancy, some pathology may become apparent during cystoscopy with hydrodistention. Potential findings include:

(A) glomerulations, or hemorrhages of the bladder mucosa

(B) damage to the urothelium

(C) Hunner’s ulcer, a defect of the urothelium that is pathognomonic for IC but uncommon.

What is IC/PBS?

This disorder consists of pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort related to the bladder and associated with a persistent urge to void. It occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or other pathology such as bladder carcinoma or cystitis induced by radiation or medication.

The term interstitial cystitis appears to have originated with New York gynecologist Alexander Johnston Chalmers Skene in 1887. Traditionally, interstitial cystitis was diagnosed only in severe cases in which bladder capacity was greatly reduced and Hunner’s ulcer, a fissuring of the bladder mucosa, was present at cystoscopy.1

In 1978, Messing and Stamey broadened the diagnosis of IC to include glomerulations at cystoscopy (FIGURE 1).2 It is now clear that the bladder can be a source of pelvic pain without these clinical findings. As a result, nomenclature has become confusing. Terms in current use include painful bladder syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and a combination of these names. Confusing matters further is the fact that these terms are not always used interchangeably.

Despite controversy over nomenclature and diagnostic criteria, there is no uncertainty that the lives of women who have IC/PBS are significantly altered by the disease. It adversely affects leisure activity, family relationships, and travel in 70% to 94% of patients.3 Suicidal thoughts are three to four times more likely in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population. Quality of life is markedly decreased across all domains, and depressive symptoms are much more common in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population.4

IC/PBS appears to affect women more often than men, and it is a frequent diagnosis among women who have chronic pelvic pain. For example, in a primary care population of women 15 to 73 years old who had chronic pelvic pain, about 30% were determined to have pain of urologic origin.5 It has been suggested, based on symptoms of urgency-frequency and a positive potassium sensitivity test, that approximately 85% of women who see a gynecologist for chronic pelvic pain have IC/PBS in addition to or instead of a gynecologic diagnosis.6 Among women given a diagnosis of endometriosis, 35% to 90% have been found to have IC/PBS as well.

FIGURE 1 Glomerulations are a common finding

Cystoscopy with hydrodistention often, but not always, reveals glomerulations (mucosal hemorrhages) in a patient who has interstitial cystitis.

Two screening tools may aid the diagnosis

IC/PBS is a clinical diagnosis, based on symptoms and signs. Although some controversy surrounds this statement, there is no question that we lack a gold-standard test to reliably make the diagnosis.

Two screening instruments are commonly used to identify patients in whom IC/PBS should be considered. One is the O’Leary-Sant questionnaire (TABLE 1), which incorporates two scales:

- the IC Symptom Index (ICSI)

- the IC Problem Index (ICPI).

The O’Leary-Sant questionnaire was not designed specifically to diagnose IC/PBS but to aid in its evaluation and management and to facilitate clinical research.

TABLE 1 The O’Leary Sant IC questionnaire

Please mark the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

TABLE 2

The Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Symptom Scale

Please circle the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1. | How many times do you go to the bathroom DURING THE DAY (to void or empty your bladder)? | 3-6 | 7-10 | 11-14 | 15-19 | 20 or more |

| 2. | How many times do you go to the bathroom AT NIGHT (to void or empty your bladder)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 or more |

| 3. | If you get up at night to void or empty your bladder, does it bother you? | Never | Mildly | Moderately | Severely | |

| 4. | Are you sexually active? No ___ Yes ___ | |||||

| 5. | If you are sexually active, do you now or have you ever had pain or symptoms during or after sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 6. | If you have pain with intercourse, does it make you avoid sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 7. | Do you have pain associated with your bladder or in your pelvis (lower abdomen, labia, vagina, urethra, perineum)? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 8. | Do you have urgency after voiding? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 9. | If you have pain, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 10. | Does your pain bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 11. | If you have urgency, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 12. | Does your urgency bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| PUR Score 0–35 | ||||||

In a busy gynecologic practice, routine use of one of these questionnaires can greatly facilitate identification of patients who may have IC/PBS.

Diagnosis can be straightforward—but often it isn’t

In many patients, diagnosis of IC/PBS is straightforward, with classic findings:

- pelvic pain

- urinary frequency (voiding every 1 or 2 hours)

- discomfort or increased pain (as opposed to a fear of losing urine) leading to urinary urge

- significant tenderness during single-digit palpation of the bladder at the time of pelvic examination

- nocturia in many cases.

Be aware that diagnosis can be more challenging when the patient is in the early course of the disease. About 90% of patients who have IC/PBS have only one symptom in the beginning—fewer than 10% experience the simultaneous onset of urgency, frequency, nocturia, and pain. The mean time from development of the initial symptom until manifestation of all symptoms ranges from 2 to 5 years.7 In about one third of patients, the initial symptom is urinary frequency and urgency preceding the onset of pain—but almost equal numbers of patients develop pelvic pain as a solitary symptom before the onset of any urinary symptoms.

Complicating matters is the fact that symptoms are often episodic early in the course of the disease. The episodic nature of symptoms often leads to multiple misdiagnoses such as urinary tract infection and recurrent or chronic cystitis. A history of empiric treatment of recurrent urinary tract infection without documentation of a positive culture is common in women who have IC/PBS. A patient who has early interstitial cystitis may respond to antibiotic treatment due to the natural waxing and waning of symptoms, the placebo effect, or an increase in fluid intake that usually accompanies antibiotic usage (dilute urine is less irritating to the bladder). Awareness of the possibility of IC/PBS in these patients is essential if diagnosis is to be made as early as possible.

Dyspareunia is another common symptom in patients who have IC/PBS. Pain during intercourse appears to arise from tenderness in the pelvic floor muscles as well as the bladder. It may also occur upon vaginal entry due to associated vulvar vestibulitis.8 In postmenopausal women, vulvovaginal atrophy may contribute to dyspareunia as well.

Also consider IC/PBS when a patient continues to experience pelvic pain after treatment of endometriosis or after hysterectomy. In one study, 80% of women who had persistent chronic pelvic pain after hysterectomy had interstitial cystitis.9 Among women who have endometriosis, we have found that 35% have IC/PBS (unpublished data). Chung reported that 85% of women who have endometriosis also have IC/PBS.10

Which diagnostic studies are useful?

To some extent, IC/PBS is a diagnosis of exclusion, as other possible causes of pelvic pain, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and nocturia must be excluded. Urinalysis and urine culture are essential tests in the evaluation of women suspected of having interstitial cystitis. Urinary tract infection must be excluded with a negative urine culture. If a patient has hematuria, urine cytology or cystoscopy is recommended to exclude malignancy. Urine cytology or cystoscopy is also recommended if the patient has a history of smoking (because of the strong association between bladder cancer and smoking) or is older than 50 years.

Some experts still insist that cystoscopic hydrodistention is necessary. Cystoscopy with hydrodistention under general or regional anesthesia has long been considered the “gold standard” diagnostic test for IC. Identification of a Hunner ulcer is pathognomonic, but it is an uncommon finding and one usually discovered only in advanced cases. More often, cystoscopy with hydrodistention in a patient who has IC reveals glomerulations, which are mucosal hemorrhages that exhibit a characteristic appearance upon second filling of the bladder (FIGURE 1).

The value of cystoscopy has recently been questioned because at least 10% of patients who have clear clinical evidence of interstitial cystitis have normal findings at the time of cystoscopic hydrodistention.11 Glomerulations have also been observed in asymptomatic patients after hydrodistention with as much as 950 mL of water. In at least one published study, glomerulations did not distinguish patients who had a clinical diagnosis of IC from asymptomatic women.12

The potassium sensitivity (parsons) test (PST) may be a useful diagnostic test for IC. It is based on the concept that patients who have the disease have a defective urothelium that allows cations to penetrate the bladder wall and depolarize the sensory C-fibers, generating lower urinary tract symptoms.13 An alternative explanation for this test may be that it identifies patients who have a hyperalgesic or allodynic bladder, whether or not there is a defect in the urothelium.

The test is performed by instilling 40 mL of sterile water into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is then asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The water is drained and 40 mL of a 0.4-molar solution of potassium chloride (40 mEq in 100 mL of water), containing a total of 16 mEq of potassium chloride, are instilled into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is again asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The test is positive when the patient reports a change of two points or more on the pain or urgency scale after instillation of potassium chloride solution.

The PST is negative in 96% of normal controls and positive in 70% to 80% of patients who have IC.14 Patients who have radiation cystitis or bacterial cystitis also have a positive response to the PST. Sensitivity of the test may decrease if the patient has recently been treated for IC, especially if the therapy involved dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or instillation of an anesthetic.

The PST can trigger the flare of severe symptoms in patients who have IC, so all women who have a positive test should receive a “rescue cocktail” after the potassium chloride solution is drained. Two of the most common rescue solutions are:

- 20,000 U of heparin mixed with 20 mL of 1% lidocaine

- a 15-mL mixture of 40,000 U of heparin, 8 mL of 2% lidocaine, and 3 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate.

The rescue cocktail usually reverses the urgency and pain brought on by potassium chloride.

A patient who has a high level of pain with IC may be unable to discern a change when potassium chloride solution is instilled, or she may be unable to tolerate the discomfort it causes. Instillation of an anesthetic agent into the bladder may be a useful diagnostic test in such a case. The rescue cocktail described above also provides an opportunity for patient and clinician to see whether her symptoms abate after introduction of the anesthetic agent.

Last, researchers have long sought a simple urinary biomarker that would be specific for IC, but none are available for routine clinical use.

Although the cause of interstitial cystitis is unknown, two main theories have developed to explain it. The popular, single end-organ theory, illustrated by the pathway with red arrows in FIGURE 2, holds that an injury or insult to the bladder is the cause. When that injury fails to heal completely, the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder is left with a defect, allowing leakage of urinary components, such as potassium, into the mucosa and submucosa. This leakage triggers an inflammatory reaction and activates nociceptors in the bladder, including nociceptors that do not usually respond to bladder distention and stimulation (so-called silent nociceptors). Activation of these nociceptors generates allodynia in the bladder, meaning that normal distention of the bladder becomes painful.

There is evidence that other pathways also lead to IC/PBS, as illustrated by the blue, bidirectional arrows. Other generators of pelvic pain, both visceral and somatic, can neurologically activate bladder nociceptors at the central level, creating “crosstalk” and leading to bladder pain and IC/PBS. In such cases, antidromic transmission (efferent transmission in afferent nerves) can lead to neurogenic bladder inflammation and contribute further to pelvic pain. Examples of pelvic pain syndromes thought to have links to IC/PBS include endometriosis, irritable bowel syndrome, and pelvic floor tension myalgia.

In addition, there is evidence that nonpelvic syndromes, such as fibromyalgia and migraine, can lead to central or peripheral sensitization that results in IC/PBS. That is, sensitization leads to chronic bladder pain from injury or stimulation that would otherwise not cause pain.

As these theories suggest, it is likely that more than one disease and one disease pathway are encompassed within the syndrome called IC/PBS. In the opening case, it appears that a severe urinary tract infection and persistent myofascial pain, and possibly endometriosis, may have been variables leading to the development of IC/PBS.

FIGURE 2 Pathways to pain

Part 2 of this article reviews components of the treatment of IC/PBS and their stepwise application.

CASE: A complex presentation, a deferred diagnosis

J. M. is a 25-year-old white nulliparous woman who visits our office reporting pelvic pain. She says the pain began when she was 16 years old, when she was taken to the emergency room for what was thought to be appendicitis. There, she was given a diagnosis of acute, severe cystitis.

Several months later, J. M. began experiencing dysmenorrhea and was given an additional diagnosis of endometriosis, for which she was treated both medically and surgically.

By the time she visits our office, J. M.’s pain has become a daily occurrence that ranges in intensity from 1 to 10 on the numerical rating scale (10, most severe). The pain is mostly localized to the right lower quadrant (RLQ) and is exacerbated by menses and intercourse. She reports mild urinary urgency, voiding every 5 to 6 hours, and one to two episodes of nocturia daily. She has no gastrointestinal symptoms.

We identify four active myofascial trigger points in the RLQ, as well as uterine and adnexal tenderness upon examination. A diagnostic laparoscopy and histology confirm endometriosis, but only three lesions are observed.

After the operation, J. M. is given 5 mg of norethindrone acetate daily to ease the pain that is thought to arise from her endometriosis. Because the pain persists, we add injections of 0.25% bupivacaine at the myofascial trigger points every 4 to 6 weeks. Her pain diminishes for as long as 6 weeks after each injection.

Fifteen months after the laparoscopy, J. M. complains of the need to void every 2 hours because of discomfort and pain and continued nocturia. This time, she experiences no pain at the trigger points, but her bladder is exquisitely tender upon palpation. We order urinalysis and culture, both of which are negative. A potassium sensitivity test is markedly positive, however, confirming the suspected diagnosis of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome.

Could this diagnosis have been made earlier?

J. M. is a real patient in our clinical practice. Her case illustrates the challenges a gynecologist faces in diagnosing chronic pelvic pain. In retrospect, it is apparent that endometriosis was not a major generator of her pain. Instead, abdominal wall myofascial pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) were the major generators. Although her myofascial pain appeared to respond to treatment with bupivacaine, she began to clearly manifest symptoms of IC/PBS.

This article describes the often-thorny diagnosis of IC/PBS and discusses the theories that have been proposed to explain the syndrome. In Part 2 of this article, the many components of management are discussed.

Early diagnosis and treatment appear to improve the response to treatment and prevent progression to severe disease. Because the gynecologist is the physician who commonly sees women at the onset of chronic pelvic pain, he or she is ideally positioned to diagnose this disorder early in its course.

Although interstitial cystitis (IC) occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or malignancy, some pathology may become apparent during cystoscopy with hydrodistention. Potential findings include:

(A) glomerulations, or hemorrhages of the bladder mucosa

(B) damage to the urothelium

(C) Hunner’s ulcer, a defect of the urothelium that is pathognomonic for IC but uncommon.

What is IC/PBS?

This disorder consists of pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort related to the bladder and associated with a persistent urge to void. It occurs in the absence of urinary tract infection or other pathology such as bladder carcinoma or cystitis induced by radiation or medication.

The term interstitial cystitis appears to have originated with New York gynecologist Alexander Johnston Chalmers Skene in 1887. Traditionally, interstitial cystitis was diagnosed only in severe cases in which bladder capacity was greatly reduced and Hunner’s ulcer, a fissuring of the bladder mucosa, was present at cystoscopy.1

In 1978, Messing and Stamey broadened the diagnosis of IC to include glomerulations at cystoscopy (FIGURE 1).2 It is now clear that the bladder can be a source of pelvic pain without these clinical findings. As a result, nomenclature has become confusing. Terms in current use include painful bladder syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and a combination of these names. Confusing matters further is the fact that these terms are not always used interchangeably.

Despite controversy over nomenclature and diagnostic criteria, there is no uncertainty that the lives of women who have IC/PBS are significantly altered by the disease. It adversely affects leisure activity, family relationships, and travel in 70% to 94% of patients.3 Suicidal thoughts are three to four times more likely in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population. Quality of life is markedly decreased across all domains, and depressive symptoms are much more common in women who have IC/PBS than in the general population.4

IC/PBS appears to affect women more often than men, and it is a frequent diagnosis among women who have chronic pelvic pain. For example, in a primary care population of women 15 to 73 years old who had chronic pelvic pain, about 30% were determined to have pain of urologic origin.5 It has been suggested, based on symptoms of urgency-frequency and a positive potassium sensitivity test, that approximately 85% of women who see a gynecologist for chronic pelvic pain have IC/PBS in addition to or instead of a gynecologic diagnosis.6 Among women given a diagnosis of endometriosis, 35% to 90% have been found to have IC/PBS as well.

FIGURE 1 Glomerulations are a common finding

Cystoscopy with hydrodistention often, but not always, reveals glomerulations (mucosal hemorrhages) in a patient who has interstitial cystitis.

Two screening tools may aid the diagnosis

IC/PBS is a clinical diagnosis, based on symptoms and signs. Although some controversy surrounds this statement, there is no question that we lack a gold-standard test to reliably make the diagnosis.

Two screening instruments are commonly used to identify patients in whom IC/PBS should be considered. One is the O’Leary-Sant questionnaire (TABLE 1), which incorporates two scales:

- the IC Symptom Index (ICSI)

- the IC Problem Index (ICPI).

The O’Leary-Sant questionnaire was not designed specifically to diagnose IC/PBS but to aid in its evaluation and management and to facilitate clinical research.

TABLE 1 The O’Leary Sant IC questionnaire

Please mark the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

TABLE 2

The Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Symptom Scale

Please circle the answer that best describes your bladder function and symptoms.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1. | How many times do you go to the bathroom DURING THE DAY (to void or empty your bladder)? | 3-6 | 7-10 | 11-14 | 15-19 | 20 or more |

| 2. | How many times do you go to the bathroom AT NIGHT (to void or empty your bladder)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 or more |

| 3. | If you get up at night to void or empty your bladder, does it bother you? | Never | Mildly | Moderately | Severely | |

| 4. | Are you sexually active? No ___ Yes ___ | |||||

| 5. | If you are sexually active, do you now or have you ever had pain or symptoms during or after sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 6. | If you have pain with intercourse, does it make you avoid sexual intercourse? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 7. | Do you have pain associated with your bladder or in your pelvis (lower abdomen, labia, vagina, urethra, perineum)? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 8. | Do you have urgency after voiding? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 9. | If you have pain, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 10. | Does your pain bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| 11. | If you have urgency, is it usually | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 12. | Does your urgency bother you? | Never | Occasionally | Usually | Always | |

| PUR Score 0–35 | ||||||

In a busy gynecologic practice, routine use of one of these questionnaires can greatly facilitate identification of patients who may have IC/PBS.

Diagnosis can be straightforward—but often it isn’t

In many patients, diagnosis of IC/PBS is straightforward, with classic findings:

- pelvic pain

- urinary frequency (voiding every 1 or 2 hours)

- discomfort or increased pain (as opposed to a fear of losing urine) leading to urinary urge

- significant tenderness during single-digit palpation of the bladder at the time of pelvic examination

- nocturia in many cases.

Be aware that diagnosis can be more challenging when the patient is in the early course of the disease. About 90% of patients who have IC/PBS have only one symptom in the beginning—fewer than 10% experience the simultaneous onset of urgency, frequency, nocturia, and pain. The mean time from development of the initial symptom until manifestation of all symptoms ranges from 2 to 5 years.7 In about one third of patients, the initial symptom is urinary frequency and urgency preceding the onset of pain—but almost equal numbers of patients develop pelvic pain as a solitary symptom before the onset of any urinary symptoms.

Complicating matters is the fact that symptoms are often episodic early in the course of the disease. The episodic nature of symptoms often leads to multiple misdiagnoses such as urinary tract infection and recurrent or chronic cystitis. A history of empiric treatment of recurrent urinary tract infection without documentation of a positive culture is common in women who have IC/PBS. A patient who has early interstitial cystitis may respond to antibiotic treatment due to the natural waxing and waning of symptoms, the placebo effect, or an increase in fluid intake that usually accompanies antibiotic usage (dilute urine is less irritating to the bladder). Awareness of the possibility of IC/PBS in these patients is essential if diagnosis is to be made as early as possible.

Dyspareunia is another common symptom in patients who have IC/PBS. Pain during intercourse appears to arise from tenderness in the pelvic floor muscles as well as the bladder. It may also occur upon vaginal entry due to associated vulvar vestibulitis.8 In postmenopausal women, vulvovaginal atrophy may contribute to dyspareunia as well.

Also consider IC/PBS when a patient continues to experience pelvic pain after treatment of endometriosis or after hysterectomy. In one study, 80% of women who had persistent chronic pelvic pain after hysterectomy had interstitial cystitis.9 Among women who have endometriosis, we have found that 35% have IC/PBS (unpublished data). Chung reported that 85% of women who have endometriosis also have IC/PBS.10

Which diagnostic studies are useful?

To some extent, IC/PBS is a diagnosis of exclusion, as other possible causes of pelvic pain, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and nocturia must be excluded. Urinalysis and urine culture are essential tests in the evaluation of women suspected of having interstitial cystitis. Urinary tract infection must be excluded with a negative urine culture. If a patient has hematuria, urine cytology or cystoscopy is recommended to exclude malignancy. Urine cytology or cystoscopy is also recommended if the patient has a history of smoking (because of the strong association between bladder cancer and smoking) or is older than 50 years.

Some experts still insist that cystoscopic hydrodistention is necessary. Cystoscopy with hydrodistention under general or regional anesthesia has long been considered the “gold standard” diagnostic test for IC. Identification of a Hunner ulcer is pathognomonic, but it is an uncommon finding and one usually discovered only in advanced cases. More often, cystoscopy with hydrodistention in a patient who has IC reveals glomerulations, which are mucosal hemorrhages that exhibit a characteristic appearance upon second filling of the bladder (FIGURE 1).

The value of cystoscopy has recently been questioned because at least 10% of patients who have clear clinical evidence of interstitial cystitis have normal findings at the time of cystoscopic hydrodistention.11 Glomerulations have also been observed in asymptomatic patients after hydrodistention with as much as 950 mL of water. In at least one published study, glomerulations did not distinguish patients who had a clinical diagnosis of IC from asymptomatic women.12

The potassium sensitivity (parsons) test (PST) may be a useful diagnostic test for IC. It is based on the concept that patients who have the disease have a defective urothelium that allows cations to penetrate the bladder wall and depolarize the sensory C-fibers, generating lower urinary tract symptoms.13 An alternative explanation for this test may be that it identifies patients who have a hyperalgesic or allodynic bladder, whether or not there is a defect in the urothelium.

The test is performed by instilling 40 mL of sterile water into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is then asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The water is drained and 40 mL of a 0.4-molar solution of potassium chloride (40 mEq in 100 mL of water), containing a total of 16 mEq of potassium chloride, are instilled into the bladder for 5 minutes. The patient is again asked to rate any change in urgency and pain over baseline levels. The test is positive when the patient reports a change of two points or more on the pain or urgency scale after instillation of potassium chloride solution.

The PST is negative in 96% of normal controls and positive in 70% to 80% of patients who have IC.14 Patients who have radiation cystitis or bacterial cystitis also have a positive response to the PST. Sensitivity of the test may decrease if the patient has recently been treated for IC, especially if the therapy involved dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or instillation of an anesthetic.

The PST can trigger the flare of severe symptoms in patients who have IC, so all women who have a positive test should receive a “rescue cocktail” after the potassium chloride solution is drained. Two of the most common rescue solutions are:

- 20,000 U of heparin mixed with 20 mL of 1% lidocaine

- a 15-mL mixture of 40,000 U of heparin, 8 mL of 2% lidocaine, and 3 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate.

The rescue cocktail usually reverses the urgency and pain brought on by potassium chloride.

A patient who has a high level of pain with IC may be unable to discern a change when potassium chloride solution is instilled, or she may be unable to tolerate the discomfort it causes. Instillation of an anesthetic agent into the bladder may be a useful diagnostic test in such a case. The rescue cocktail described above also provides an opportunity for patient and clinician to see whether her symptoms abate after introduction of the anesthetic agent.

Last, researchers have long sought a simple urinary biomarker that would be specific for IC, but none are available for routine clinical use.

Although the cause of interstitial cystitis is unknown, two main theories have developed to explain it. The popular, single end-organ theory, illustrated by the pathway with red arrows in FIGURE 2, holds that an injury or insult to the bladder is the cause. When that injury fails to heal completely, the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder is left with a defect, allowing leakage of urinary components, such as potassium, into the mucosa and submucosa. This leakage triggers an inflammatory reaction and activates nociceptors in the bladder, including nociceptors that do not usually respond to bladder distention and stimulation (so-called silent nociceptors). Activation of these nociceptors generates allodynia in the bladder, meaning that normal distention of the bladder becomes painful.

There is evidence that other pathways also lead to IC/PBS, as illustrated by the blue, bidirectional arrows. Other generators of pelvic pain, both visceral and somatic, can neurologically activate bladder nociceptors at the central level, creating “crosstalk” and leading to bladder pain and IC/PBS. In such cases, antidromic transmission (efferent transmission in afferent nerves) can lead to neurogenic bladder inflammation and contribute further to pelvic pain. Examples of pelvic pain syndromes thought to have links to IC/PBS include endometriosis, irritable bowel syndrome, and pelvic floor tension myalgia.

In addition, there is evidence that nonpelvic syndromes, such as fibromyalgia and migraine, can lead to central or peripheral sensitization that results in IC/PBS. That is, sensitization leads to chronic bladder pain from injury or stimulation that would otherwise not cause pain.

As these theories suggest, it is likely that more than one disease and one disease pathway are encompassed within the syndrome called IC/PBS. In the opening case, it appears that a severe urinary tract infection and persistent myofascial pain, and possibly endometriosis, may have been variables leading to the development of IC/PBS.

FIGURE 2 Pathways to pain

Part 2 of this article reviews components of the treatment of IC/PBS and their stepwise application.

1. Hunner GL. A rare type of bladder ulcer in women: report of cases. Boston Med Surg. 1915;172.-

2. Messing EM, Stamey TA. Interstitial cystitis: early diagnosis, pathology, and treatment. Urology. 1978;12(4):381-392.

3. Koziol JA, Clark DC, Gittes RF, Tan EM. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: a survey of 374 patients. J Urol. 1993;149(3):465-469.

4. Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Hoffman A, Kreder KJ. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2002;167(4):1763-1767.

5. Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(11):1149-1155.

6. Parsons CL, Bullen M, Kahn BS, Stanford EJ, Willems JJ. Gynecologic presentation of interstitial cystitis as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98 (1):127-132.

7. Driscoll A, Teichman JM. How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol. 2001;166(6):2118-2120.

8. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996-1002.

9. Chung MK. Interstitial cystitis in persistent posthysterectomy chronic pelvic pain. JSLS. 2004;8(4):329-333.

10. Chung MK, Chung RR, Gordon D, Jennings C. The evil twins of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: endometriosis and interstitial cystitis. JSLS. 2002;6(4):311-314.

11. Messing EM. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1987;29(4 suppl):4-7.

12. Waxman JA, Sulak PJ, Kuehl TJ. Cystoscopic findings consistent with interstitial cystitis in normal women undergoing tubal ligation. J Urol. 1998;160(5):1663-1667.

13. Parsons CL, Zupkas P, Parsons JK. Intravesical potassium sensitivity in patients with interstitial cystitis and urethral syndrome. Urology. 2001;57(3):428-433.

14. Parsons CL, Stein PC, Bidair M, Lebow D. Abnormal sensitivity to intravesical potassium in interstitial cystitis and radiation cystitis. Neurourol Urodyn. 1994;13(5):515-520.

1. Hunner GL. A rare type of bladder ulcer in women: report of cases. Boston Med Surg. 1915;172.-

2. Messing EM, Stamey TA. Interstitial cystitis: early diagnosis, pathology, and treatment. Urology. 1978;12(4):381-392.

3. Koziol JA, Clark DC, Gittes RF, Tan EM. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: a survey of 374 patients. J Urol. 1993;149(3):465-469.

4. Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Hoffman A, Kreder KJ. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2002;167(4):1763-1767.

5. Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(11):1149-1155.

6. Parsons CL, Bullen M, Kahn BS, Stanford EJ, Willems JJ. Gynecologic presentation of interstitial cystitis as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98 (1):127-132.

7. Driscoll A, Teichman JM. How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol. 2001;166(6):2118-2120.

8. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996-1002.

9. Chung MK. Interstitial cystitis in persistent posthysterectomy chronic pelvic pain. JSLS. 2004;8(4):329-333.

10. Chung MK, Chung RR, Gordon D, Jennings C. The evil twins of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: endometriosis and interstitial cystitis. JSLS. 2002;6(4):311-314.

11. Messing EM. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1987;29(4 suppl):4-7.

12. Waxman JA, Sulak PJ, Kuehl TJ. Cystoscopic findings consistent with interstitial cystitis in normal women undergoing tubal ligation. J Urol. 1998;160(5):1663-1667.

13. Parsons CL, Zupkas P, Parsons JK. Intravesical potassium sensitivity in patients with interstitial cystitis and urethral syndrome. Urology. 2001;57(3):428-433.

14. Parsons CL, Stein PC, Bidair M, Lebow D. Abnormal sensitivity to intravesical potassium in interstitial cystitis and radiation cystitis. Neurourol Urodyn. 1994;13(5):515-520.

When treating interstitial cystitis, address all sources of pain

Dr. Howard is a speaker and consultant for Ortho Women’s Health and Urology and a consultant for Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology.

In Part 1 of this article, I discussed an actual case of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) that was diagnosed in our clinic. That diagnosis was challenging, made over a period longer than 1 year. Regrettably, such a delay is not unusual—especially in patients who already have another diagnosis, such as endometriosis, as was true in that case.

Once a diagnosis of IC/PBS has been made, the first, crucial step is educating and involving the patient in her diagnosis and treatment, as she is more likely to accept the need for chronic, multimodal therapy. As I mentioned in Part 1, early diagnosis may be especially important. Response to treatment in patients who have a short duration of symptoms (less than 2.5 years) is 75% to 80%, and treatment often leads to clinical remission.

Here, I lay out the numerous treatment modalities the clinician can draw from to manage this complex disease. Therapy generally involves dietary manipulation, urothelial therapy such as intravesical heparin or oral pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS), and a tricyclic antidepressant for its neurolytic properties. Second-line therapies include mast-cell stabilization with antihistamines and other neurolytic agents.

The only FDA-approved treatments, however, are intravesical dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and oral PPS.

Eliminate as many sources of pain as possible

IC/PBS is a complex chronic pain syndrome, so it is critical to identify all potential sources of pain, or pain generators, and to eliminate or treat as many of them as possible. The goal of this approach is to decrease the volume of nociceptive input to the dorsal horn. Although we lack substantial supporting evidence, the hope is that this approach may allow the dorsal horn and central nervous system to “down-regulate” and potentially normalize, or at least allow pain-modulating mechanisms to “gate” the noxious stimuli arriving at the dorsal horn and decrease the intensity of pain. This approach leads to a need for multimodal therapy in most patients.

Dietary changes may help

Patients who have IC often report exacerbation of symptoms with the intake of certain foods or fluids, suggesting that dietary modification or restriction may be therapeutic (TABLE). More than 50% of patients report exacerbation of symptoms with acidic foods, carbonated drinks, alcoholic beverages, and caffeine. The elimination of these foods and beverages often results in significant improvement of symptoms. Calcium glycerophosphate (Prelief) prevents food-related exacerbation in about 70% of patients.

TABLE

Foods that may irritate the urinary tract

| Alcoholic beverages |

| Apple and apple juice |

| Cantaloupe |

| Carbonated drinks |

| Chili and similar spicy foods |

| Chocolate |

| Citrus fruit |

| Coffee |

| Cranberry and cranberry juice |

| Grape |

| Guava |

| Peach |

| Pineapple |

| Plum |

| Strawberry |

| Sugar |

| Tea |

| Tomato and tomato juice |

| Vinegar |

| Vitamin B complex |

DMSO may ease symptoms, but treatment can be painful

DMSO (RIMSO-50) was the first drug approved by the FDA for treatment of IC. It is approved for intravesical instillation, which can be performed in the office. A small urethral catheter (8–12 French) is inserted, and the bladder is emptied. A 50-mL volume of 50% DMSO is instilled, and the catheter is removed. After waiting 15 to 30 minutes, the patient voids. Treatments are usually repeated at 1- to 2-week intervals.

Some patients find DMSO treatment painful. In that case, a pretreatment dose of ibuprofen (800 mg orally), naproxen sodium (550 mg orally), or ketorolac tromethamine (10 mg orally) may be considered.

Some patients complain of significant irritation and burning of the urethra with DMSO. For them, the urethra may be anesthetized with 2% topical lidocaine. In addition, the catheter may be left inside the urethra and clamped during the 15 to 30 minutes of treatment, allowing emptying of the DMSO via the catheter before removal. In the 10% of patients who experience painful bladder spasms, anticholinergic medications or belladonna and opium suppositories may provide relief.

All patients note a garlic-like odor of breath and taste in the mouth for 24 to 48 hours after DMSO therapy, due to excretion via the respiratory system as dimethylsulfide. This can be personally and socially unpleasant for the patient, so it is critical that she be counseled about this side effect beforehand.

DMSO has very low systemic toxicity. However, it has been reported to be teratogenic in animal studies, so its use in pregnancy is contraindicated.

The one published randomized, clinical trial of DMSO showed marked improvement in symptoms in 53% of patients treated every 2 weeks for a total of eight treatments, compared with 18% of patients treated with placebo (number needed to treat [NNT], 2.8).1

Oral PPS may ease symptoms—after several months of use

Pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS) is a semi-synthetically produced heparin-like macro-molecular carbohydrate derivative, which chemically and structurally resembles glycosaminoglycans. In 1996, PPS became the first oral drug approved for the treatment of IC. It is sold under the brand name Elmiron. Its efficacy is thought to derive from its glycosaminoglycan-like characteristics, which act to restore integrity of the urothelial barrier. The recommended dosage is 100 mg three times daily. PPS is cleared in the urine.

Randomized, controlled trials of the efficacy of PPS have produced mixed results; at 3 months, however, it appears to produce a 25% to 50% response rate, compared with a placebo response rate of 13% to 23%, yielding a NNT of about 4.2,3 Pelvic pain diminished in as many as 45% of patients, compared with about 18% in the placebo group.

Because of its mode of action, therapeutic response is delayed. The patient generally does not respond before about 3 months of treatment, but it can be as long as 12 months.4 In general, a 6-month trial should be completed before concluding that the patient is unresponsive to PPS. A positive PST may be predictive of response to PPS.5

PPS has low toxicity and few side effects. In rare cases, the transaminase level may rise. Headache, nausea, diarrhea, dizziness, skin rash, peripheral edema, and hair loss are the most common side effects, but they occur in fewer than 10% of patients.6 In randomized trials of PPS, in fact, adverse effects often occurred at a higher rate in the placebo group.3 No serious interactions between oral PPS and other medications have been reported.

Some data suggest that PPS may be effective when it is administered intravesically.7 This may be an option for patients who experience side effects after oral administration.

Among tricyclics, amitriptyline is most effective

Tricyclic antidepressants have proved to be effective in the treatment of IC, particularly amitriptyline, the most commonly prescribed tricyclic for the disease. Amitriptyline has multiple modes of action. Its anticholinergic effects reduce urinary frequency, and its sedating effects improve sleep and help decrease nocturia. Tricyclics effectively treat neuropathic pain—a mode of action that is probably important in IC.

The efficacy of amitriptyline has been confirmed in at least one randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of 50 patients with IC.8 Mean symptom scores decreased by 31% among patients treated with amitriptyline, compared with 13% in the placebo-treated group. Pain scores diminished by 43% in the amitriptyline group, compared with a 2% increase in the placebo group. Among patients treated with amitriptyline, 53% rated their satisfaction “good” or “excellent,” compared with 4% in the placebo group, yielding a NNT of 2. Anticholinergic side effects, especially dry mouth, were reported by 92% of patients treated with amitriptyline, compared with 21% of those treated with placebo. Final dosages of amitriptyline in this study were:

- 25 mg in 29% of patients

- 50 mg in 37.5%

- 75 mg in 21%

- 100 mg in 12.5%.

Patients self-titrated, based on efficacy and side effects.

This clinical trial confirms the clinical impression that amitriptyline is effective and relatively well tolerated, and that dosages lower than those used for the treatment of depression are adequate for treatment of IC.

Physical therapy may be effective in intractable cases

The pelvic floor muscles can become a source of persistent pain even if bladder inflammation and up-regulation are aggressively treated. Treatment of any pelvic floor muscle dysfunction and hypertonus is an important component of management in patients who have IC. Physical therapy techniques that involve manual or soft-tissue manipulation can be used to improve symptoms moderately or markedly in as many as 83% of patients who have failed a more traditional approach to IC.9 A published clinical trial suggests that physical therapy is effective in the treatment of IC/PBS.10

Intravesical heparin has no effect on coagulation

Heparin is thought to repair the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder, or at least to coat and protect bladder epithelium. It can be used intravesically with minimal concern for anticoagulation. Because heparin is insignificantly absorbed into the circulation from the bladder, a partial thromboplastin time assay is not needed.

Heparin is usually instilled in combination with other medications—either dimethylsulfoxide or local anesthetic agents.

No randomized trials of intravesical heparin treatment hve been performed.

Local anesthetics are effective, observational data indicate

Intravesical administration of local anesthetic agents—usually lidocaine—appears to provide significant relief from pelvic pain arising from IC. Only observational data on their use are available, however.

Treatment with these agents reflects the newer concept that IC-related pain may be neuropathic and that local anesthetics may down-regulate the bladder afferent nerves.11 Parsons noted that 80% of patients experienced pain relief after intravesical treatment with a therapeutic solution of 40,000 U of heparin, 8 mL of 2% lidocaine, and 3 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate, given three times weekly for 2 weeks. Pain relief was sustained for at least 48 hours after the last instillation.

Lidocaine has also been used intravesically at a dosage of 20 mL of 1% solution. Most reports of local anesthetic usage have included heparin at dosages of 10,000 to 40,000 U, but not all have included the addition of sodium bicarbonate, which may increase absorption of local anesthetic agents into the bladder epithelium and improve efficacy.12 The instillation of local anesthetics is common in practice, but clinical trials are needed to confirm its safety and efficacy.

Consider an antihistamine if there is a history of allergy

Activated mast cells play a role in the inflammatory response of the bladder in many patients who have IC. Medications that stabilize and reduce mast cell activation may be effective, especially in patients who have a history of significant allergy. For example, in an open-label study, hydroxyzine reduced symptoms by 40% overall, but it reduced them by 55% in patients who had a history of significant allergy.13 PPS is a potent antihistamine, as well as an effective glycosaminoglycan in the bladder micellar formation. Hydroxyzine, like PPS, may have to be administered for several months before symptoms improve significantly, so patients should continue treatment for 3 to 6 months before making a decision about efficacy.

The one published randomized, clinical trial of hydroxyzine yielded a response rate of 31%, compared with 20% among patients who did not receive the drug, but this difference failed to reach statistical significance.14

Anticonvulsants are largely untested in treatment of IC

Several anticonvulsants have proved to be effective in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Although they have been suggested as a possible treatment for IC, their efficacy in this regard has not been well established.

Gabapentin is an anticonvulsant commonly used to treat pain. In an uncontrolled, open-label trial, the drug reduced pain in 10 (48%) of 21 patients who had IC, but four patients (20%) dropped out due to side effects.15

Is hormonal manipulation useful?

One observational study suggests that hormonal manipulation may improve bladder symptoms of IC.16 Twenty-three of 46 women in this series experienced a notable perimenstrual increase in IC-related pain. Fifteen of the 23 were treated with leuprolide acetate, a combined oral contraceptive, or hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. All but one also had a gynecologic diagnosis of endometriosis, pelvic congestion syndrome, or chronic pelvic inflammatory disease. Thirteen of the 15 experienced sustained improvement of symptoms attributed to IC. The bottom line: Consider cyclic suppression in patients who have a history of perimenstrual flare.

Three initial modalities yield good results

In our clinic, we tend to start patients on both PPS and amitriptyline. If the patient has a high level of pain, we include bladder instillation with lidocaine and heparin to see whether they provide immediate pain relief. More than 50% of our patients are adequately treated with these three modalities. The addition of other treatments depends on the patient’s response to and tolerance of these initial treatments.

Other nonbladder sources of pain should also be identified and treated, such as irritable bowel syndrome, endometriosis, vulvodynia, and pelvic floor tension myalgia.

The effectiveness of multimodality therapy has not been well studied. A great deal more research is needed, particularly randomized, placebo-controlled studies.

CASE RESOLVED: A multimodal approach alleviates severe pain

Twenty-five-year-old J. M. has just been given a diagnosis of IC/PBS. We advise her to avoid caffeine, carbonated drinks, alcoholic beverages, and acidic foods. We also prescribe oral PPS and teach her how to instill heparin and lidocaine into her bladder.

Because J. M. was given an earlier diagnosis of endometriosis, we also continue hormonal suppression with norethindrone acetate.

When her pain remains bothersome after 6 months, we add 600 mg of gabapentin each night.

Four years after her first visit to our office, J. M. reports pain levels that range from 0 to 4, with occasional flares to 4 with breakthrough bleeding. She now voids at intervals of 4 to 6 hours and reports no nocturia.

Part 1: Interstitial cystituis- The gynecologist's guide to diagnosis

1. Perez-Marrero R, Emerson LE, Feltis JT. A controlled study of dimethyl sulfoxide in interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1988;140(1):36-39.

2. Parsons CL, Benson G, Childs SJ, Hanno P, Sant GR, Webster G. A quantitatively controlled method to study prospectively interstitial cystitis and demonstrate the efficacy of pentosanpolysulfate. J Urol. 1993;150(3):845-848.

3. Mulholland SG, Hanno P, Parsons CL, Sant GR, Staskin DR. Pentosan polysulfate sodium for therapy of interstitial cystitis. A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical study. Urology. 1990;35(6):552-558.

4. Hanno PM. Analysis of long-term Elmiron therapy for interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1997;49(5A suppl):93-99.

5. Teichman JM, Nielsen-Omeis BJ. Potassium leak test predicts outcome in interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1999;161(6):1791-1796.

6. Jepsen JV, Sall M, Rhodes PR, Schmidt D, Messing E, Bruskewitz RC. Long-term experience with pentosanpolysulfate in interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1998;51(3):381-387.

7. Bade JJ, Laseur M, Nieuwenburg A, van der Weele LT, Mensink HJ. A placebo-controlled study of intravesical pentosanpolysulphate for the treatment of interstitial cystitis. Br J Urol. 1997;79(2):168-171.

8. van Ophoven A, Pokupic S, Heinecke A, Hertle L. A prospective, randomized, placebo controlled, double-blind study of amitriptyline for the treatment of interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2004;172(2):533-536.

9. Weiss JM. Pelvic floor myofascial trigger points: manual therapy for interstitial cystitis and the urgency-frequency syndrome. J Urol. 2001;166(6):2226-2231.

10. FitzGerald MP, Anderson RU, Potts J, et al. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J Urol. 2009;182(2):570-580.

11. Parsons CL. Successful downregulation of bladder sensory nerves with combination of heparin and alkalinized lidocaine in patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2005;65(1):45-48.

12. Henry R, Patterson L, Avery N, et al. Absorption of alkalized intravesical lidocaine in normal and inflamed bladders: a simple method for improving bladder anesthesia. J Urol. 2001;165(6 Pt 1):1900-1903.

13. Theoharides TC, Sant GR. Hydroxyzine therapy for interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1997;49(supple 5A):108-110.

14. Sant GR, Propert KJ, Hanno PM, et al. A pilot clinical trial of oral pentosan polysulfate and oral hydroxyzine in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2003;170(3):810-815.

15. Sasaki K, Smith CP, Chuang YC, Lee JY, Kim JC, Chancellor MB. Oral gabapentin (neurontin) treatment of refractory genitourinary tract pain. Tech Urol. 2001;7(1):47-49.

16. Lentz GM, Bavendam T, Stenchever MA, Miller JL, Smalldridge J. Hormonal manipulation in women with chronic, cyclic irritable bladder symptoms and pelvic pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1268-1273.

Dr. Howard is a speaker and consultant for Ortho Women’s Health and Urology and a consultant for Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology.

In Part 1 of this article, I discussed an actual case of interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS) that was diagnosed in our clinic. That diagnosis was challenging, made over a period longer than 1 year. Regrettably, such a delay is not unusual—especially in patients who already have another diagnosis, such as endometriosis, as was true in that case.

Once a diagnosis of IC/PBS has been made, the first, crucial step is educating and involving the patient in her diagnosis and treatment, as she is more likely to accept the need for chronic, multimodal therapy. As I mentioned in Part 1, early diagnosis may be especially important. Response to treatment in patients who have a short duration of symptoms (less than 2.5 years) is 75% to 80%, and treatment often leads to clinical remission.

Here, I lay out the numerous treatment modalities the clinician can draw from to manage this complex disease. Therapy generally involves dietary manipulation, urothelial therapy such as intravesical heparin or oral pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS), and a tricyclic antidepressant for its neurolytic properties. Second-line therapies include mast-cell stabilization with antihistamines and other neurolytic agents.

The only FDA-approved treatments, however, are intravesical dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and oral PPS.

Eliminate as many sources of pain as possible