User login

Bridging the Knowledge-Action Gap in Skin Cancer Prevention Among US Military Personnel

Skin cancer is a major health concern for military service members, who experience notably higher incidence rates than the general population.1 Active-duty military personnel are particularly vulnerable to prolonged sun exposure due to deployments, specialized training, and everyday outdoor duties.1 Despite skin cancer being the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in active-duty service members,2 tracking and documenting the quantity and diversity of these risk factors remain limited. This knowledge gap comes at high cost, simultaneously impairing military medicine preventive measures while burdening the military health care system with substantial expenditures.3 These findings underscore the critical need for targeted surveillance, early-detection programs, and policy-driven interventions to mitigate these medical and economic concerns.

Skin cancer has been recognized as a major health risk to the military population for decades, yet incidence and prevalence remain high. This phenomenon is closely linked to the inherent responsibilities and expectations of active-duty military members, including outdoor physical training, field exercises, standing in formation, and outdoor working environments—all of which can occur during peak sunlight hours. These risks are further elevated at duty stations in geographic regions with high levels of UV exposure, such as those in tropical and arid regions of the world. Certain military occupational specialties and missions may further introduce unique risk factors; for instance, pilots with frequent high-altitude missions experience heightened UV exposure and melanoma risk.4 Secondary to compounding determinants, the aviation, diving, and nuclear subgroups of the military community are particularly vulnerable to skin cancer.5

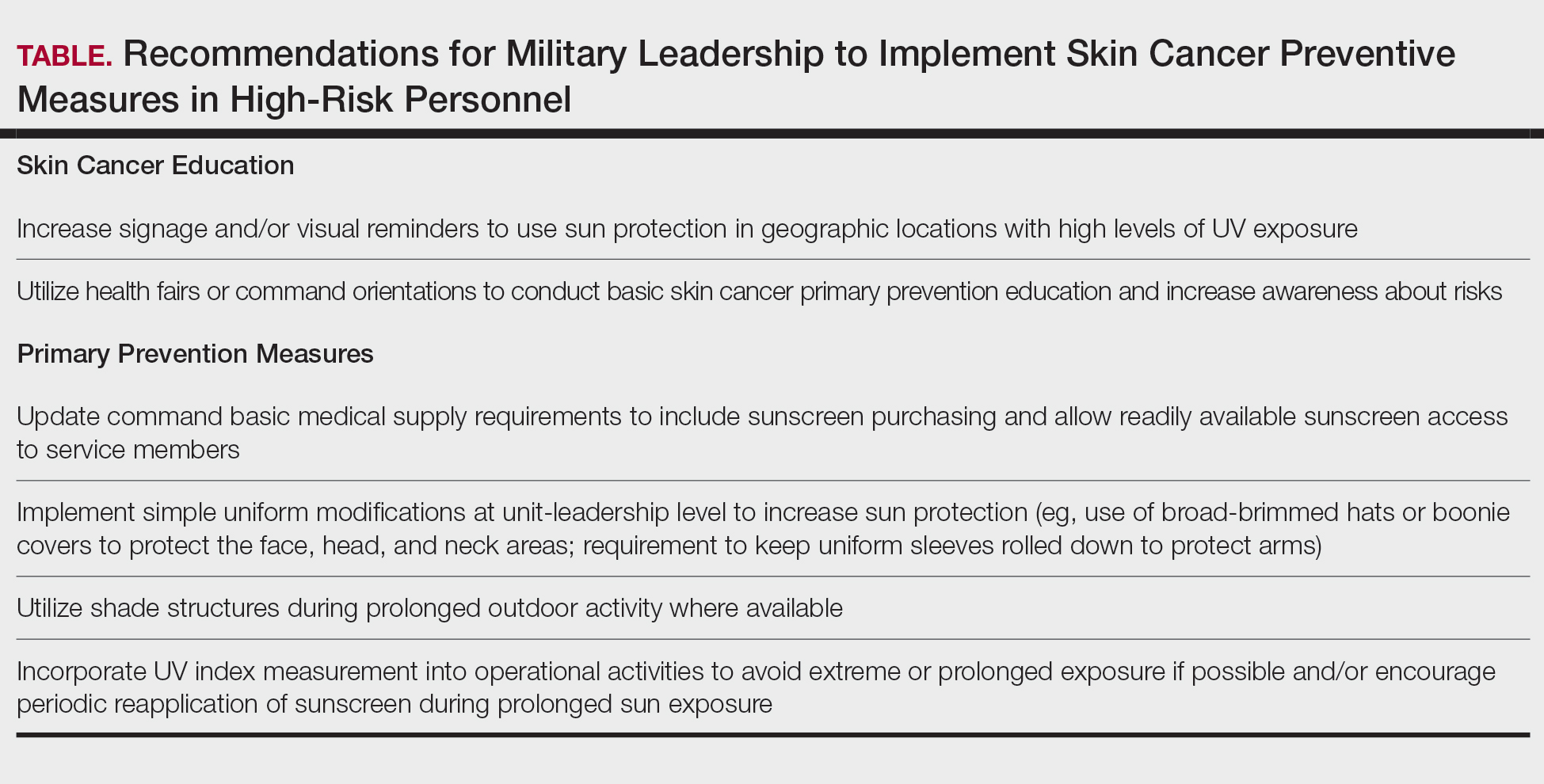

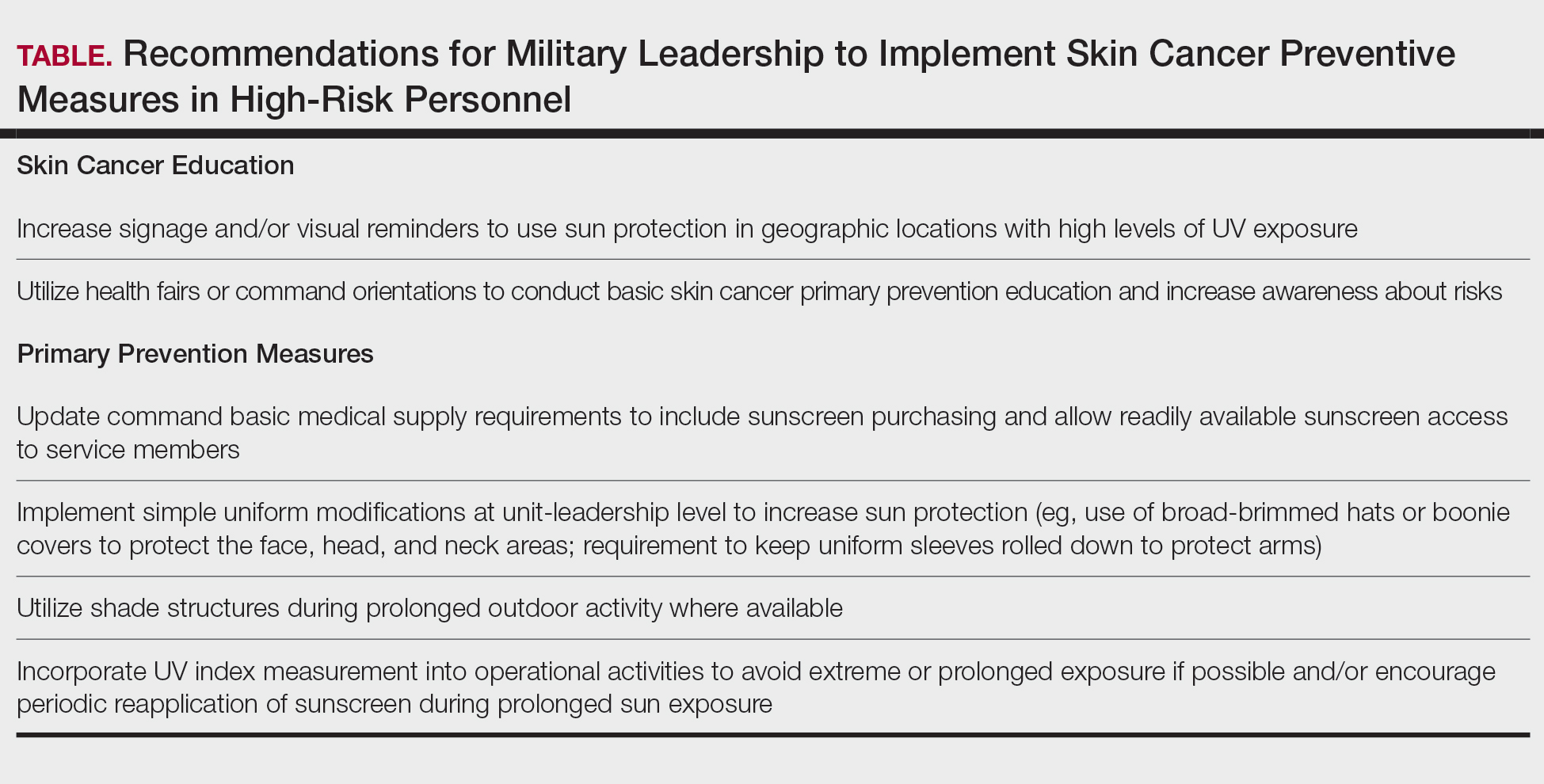

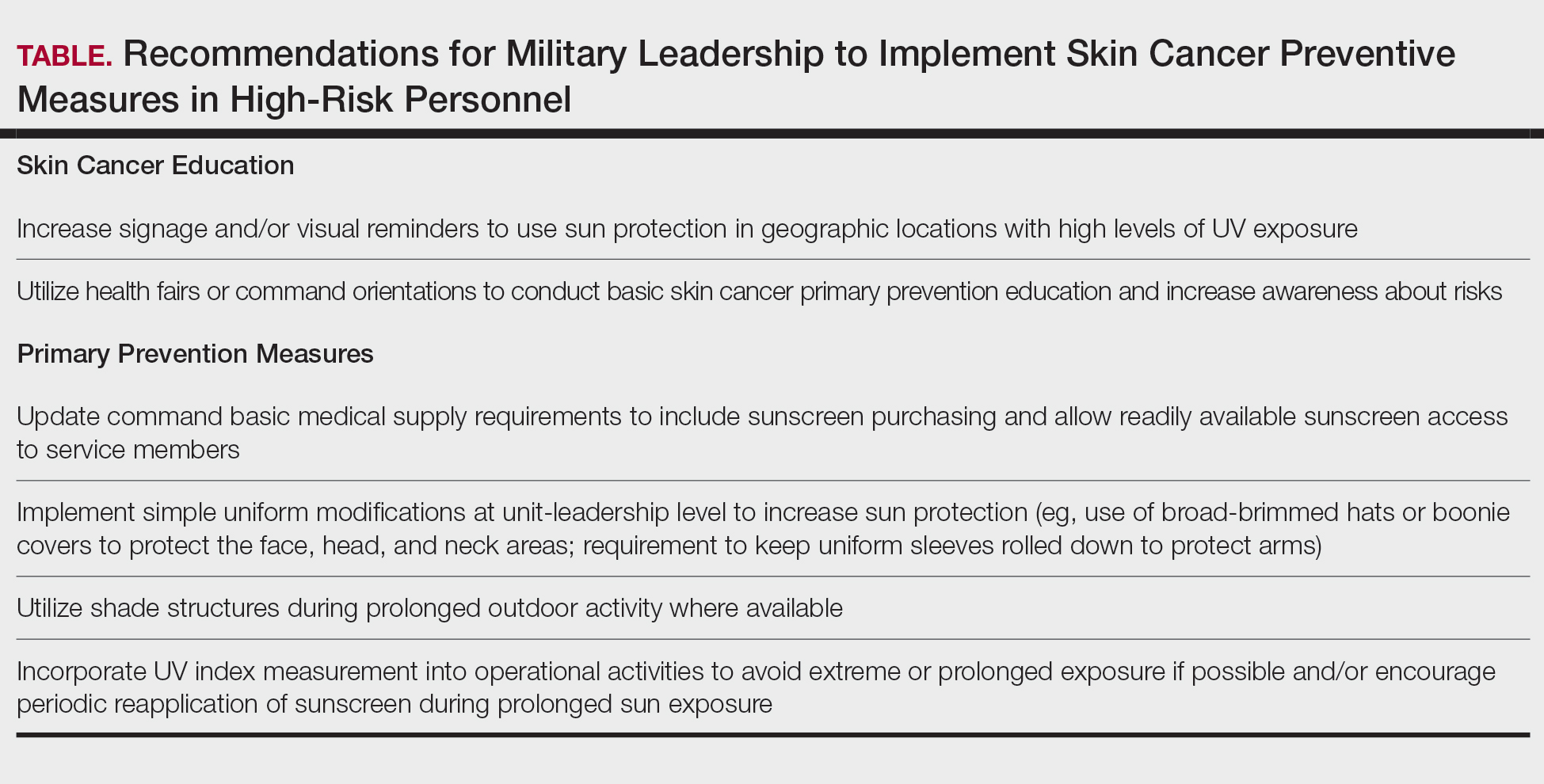

Despite well-documented risks, considerable gaps remain in quantifying and analyzing variations in UV exposure across military occupations, duty locations, and operational roles. Factors such as the existence of over 150 distinct military occupational specialties, frequent geographic relocations, and routine work in austere environments contribute to a wide range of UV exposure profiles that remain insufficiently characterized. This lack of comprehensive exposure data hinders the development of large-scale, targeted skin cancer prevention strategies. Initial approaches to addressing these challenges include enhanced surveillance, education, and policy initiatives. The Table presents practical recommendations for military leadership to consider in implementing preventive measures for skin cancer. Herein, we outline broader systemic strategies to bridge knowledge gaps and address underrecognized occupational risk factors for skin cancer in military service members; these elements include proposed modifications to the electronic Periodic Health Assessment (ePHA) and the development of standardized, military-specific screening and prevention guidelines to support early detection and resource optimization.

Skin Cancer Education for Service Members

Sunscreen and Signage—Diligent primary prevention offers a promising avenue for mitigating skin cancer incidence in military service members. Basic education and precautionary messaging on photoprotection can be widely implemented to simultaneously educate service members on the dangers of sun exposure while reinforcing healthy behaviors in real time. Simple low-cost initiatives such as strategically placed visual signage reminding service members to apply sunscreen in high UV environments can support consistent sun-safe practices. Educational efforts also should emphasize proper sunscreen use, including application on high-risk anatomic sites (eg, the face, neck, scalp, dorsal hands, and ears) and the essentiality of using sufficient quantities of broad-spectrum sunscreen for effective protection. Incorporating this guidance into training materials, briefings, and visual reminders allow seamless integration of photoprotection into service members’ daily routines without compromising operational efficiency.6 Younger service members, who may be less likely to prioritize preventive behaviors, may be particularly responsive to sun safety reminders in training areas, bases, and deployment zones.7 Health fairs and orientation briefs in high-UV regions also offer potential opportunities for targeted education.

Resources for Sun Protection in the Military

Sunscreen—Although sunscreen is critical in minimizing the risk for UV-induced skin cancer, its widespread use in the military is hindered by practical challenges related to accessibility and the need for consistent reapplication; for instance, providing free sunscreen dispensers at institutions for staff working under intense or prolonged UV exposure may improve sunscreen accessibility and use.8 Including sunscreen in standard-issue gear offers another logical way to embed its use into operational readiness as part of the routine protective measures.

Uniform Modifications—Adapting military uniforms and practices to improve sun protection plays a critical role in reducing skin cancer risk. Targeted protective gear for commonly sun-exposed areas can help mitigate UV exposure. One practical option is the use of wide-brimmed headgear (eg, boonie hats), which provide more face and neck coverage than standard-issue military caps, or covers. The wide-brimmed headgear currently is only selectively authorized during specific scenarios, such as field operations and training exercises, or at the discretion of unit-level leadership. Wide-brimmed headgear, already used by many service members, has been associated with up to a 17% reduction in UV exposure to inadequately protected areas, potentially lowering skin cancer risk.9,10 Similarly, a “sleeves-down” policy—requiring sleeves to remain unrolled and covering the forearms during outdoor activities—offers a simple way to minimize sun exposure without necessitating additional gear. Other specialized clothing items, including UV-blocking neck gaiters, photoprotective clothing, and lightweight gloves, also may be appropriate for high-risk groups and can be implemented in a relatively straightforward manner.

Shade Structures and UV Index Monitoring—Aside from uniform adaptation, physical barrier intervention can further complement skin cancer prevention efforts in the military. Shade structures offer a straightforward way to reduce UV exposure during prolonged outdoor activities. Incorporating daily UV index monitoring into operational guidance can help inform adjustments to training schedules and guide the implementation of additional sun protection measures, such as mandatory sunscreen application, use of wide-brimmed hats, or increased access to shaded rest areas during heavy sunlight hours. Currently, outdoor physical training is restricted during periods of high heat index, measured via Wet Bulb Globe Temperature, to reduce heat-related injuries. We argue that avoidance of nonoperational outdoor activity during peak UV index hours also should be incorporated into standardized policies. This intervention is of particular benefit to service members stationed in regions with a high UV index year-round, such as those stationed in the Middle East, Guam, Okinawa, and southern coastal United States bases.

Policy Changes to Support Photoprotective Measures

Annual Risk Factor Screening‐Screening—Effective secondary prevention efforts by military dermatologists remain an important measure in reducing the burden of skin cancer among military personnel; however, these efforts have become increasingly challenging due to 2 main factors—the diversity of military occupational specialties and their associated unique occupational risks as well as the limited availability of military dermatologists across all branches (approximately 100 active-duty dermatologists for nearly 3 million service members).11 Therefore, targeted interventions that enhance risk assessment, refined screening protocols, and leveraging of existing military health networks can improve early skin cancer detection while optimizing resource allocation.

The ePHA is an online screening tool used annually by all service members to evaluate their overall health. Presently, the ePHA lacks specific questions to assess sun exposure and skin cancer risks. Integrating annual skin cancer risk factor assessments into the ePHA would offer a practical and straightforward approach to identifying at-risk individuals, as suggested by Newnam et al12 in 2022. Skin cancer risk factor assessments allow for targeted data collection related to sun exposure history, family history, and personal risk factors, which can be used to determine individualized risk stratification to assess the need for early secondary prevention measures and specialist referral. These ePHA data can also support population-based analyses to inform preventive strategies and address knowledge gaps related to high-risk exposures, such as extended field exercises or assignments in high-UV regions, that may impede effective skin cancer prevention.

Development of Military-Specific Screening Guidelines—Given the limited number of military dermatologists, a standardized risk-assessment tool could enhance early detection of skin cancer and streamline the referral process. We propose a military-specific skin cancer screening algorithm or risk nomogram that could help to consolidate risk factors into a clear and actionable framework for more efficient triage and appropriate allocation of dermatologic resources and manpower. This nomogram could be developed by military dermatologists and then implemented on a command level, affording primary care providers a useful tool to expedite evaluation of individuals at higher risk for skin cancer while simultaneously promoting judicious use of limited dermatology resources.

Although the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not universally recommend routine skin cancer screenings for asymptomatic adults, military service members are exposed to higher occupational risks than the general population, as previously mentioned. Currently, there is no standardized screening guideline across all military services due to the unique nature and exposure risks for each branch of service and their varied occupations; however, we propose the development of basic standardized screening guidelines by adapting the framework of the United States Preventive Services Task Force and adjusting for military-specific UV exposure and occupational risks to improve early detection of skin cancer. These guidelines could be updated and tailored appropriately when additional population-based data are collected and analyzed through ePHA.

Critiques and Limitations of Implementation

Several challenges and limitations must be considered when attempting to integrate large-scale preventive measures for skin cancer within the US military. A primary concern is the extent to which military resources should be allocated to prevention when off-duty sun exposure remains largely beyond institutional control. Although military health initiatives can address workplace risk through education and policy, individual decisions during both work and leisure time remain a major variable that cannot be feasibly controlled. Cultural and operational barriers also pose challenges; for instance, the US Marine Corps maintains a strong cultural identity tied to uniform appearance, making it difficult to implement widespread changes to clothing-based sun-protection measures. Institutional changes, particularly those involving uniforms, likely will face substantial administrative resistance and potential operational limitations. When broad uniform modifications are unattainable, a more feasible approach may be to encourage unit-level leadership to authorize and promote the frequent use of nonuniform protective measures.

Furthermore, integrating additional skin cancer risk questions into the already extensive ePHA means extra time required to complete the assessment; this adds to service members’ administrative burden, potentially leading to reduced timely compliance, rushed responses, and survey fatigue, which threaten data quality. If new items are to be included, they should be carefully selected for efficiency and clinical relevance. Existing validated questionnaires such as those from the study by Lyford et al7 published in 2021 can serve as a foundation.

Another critical limitation is access to dermatologic care for active-duty service members. Raising awareness of skin cancer risk without ensuring adequate resources may create ethical concerns, particularly in high-risk environments such as the Middle East and Indo-Pacific. Additionally, because skin cancer often develops years or decades after exposure, securing early buy-in from service members and their leaders can be challenging. These concerns make it clear that, while skin cancer prevention is important, implementing widespread measures is not straightforward and requires a practical and balanced approach.

Final Thoughts

Implementing prevention strategies for skin cancer in the military requires balancing evidence-based recommendations with the practical realities of military culture, resource limitations, and operational demands. Challenges remain for dermatologists in providing targeted recommendations due to the multifaceted nature of military roles, including over 150 Navy Military Occupational Specialties, limited familiarity with the unique UV exposure risks associated with each occupation, and variability in local and regional policies on uniform wear, physical training requirements, and other operational practices. Although targeted prevention measures are difficult to establish in the setting of these knowledge gaps, leveraging unit-level leadership to align with existing screening guidelines and optimizing primary prevention measures can be meaningful steps toward reducing skin cancer risk for military service members while maintaining mission readiness.

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancerincidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Lee T, Taubman SB, Williams VF. Incident diagnoses of non-melanoma skin cancer, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005-2014. MSMR. 2016;23:2-6.

- Krivda KR, Watson NL, Lyford WH, et al. The burden of skin cancer in the military health system, 2017-2022. Cutis. 2024;113:200-215. doi:10.12788/cutis.1015

- Sanlorenzo M, Wehner MR, Linos E, et al. The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:51-58. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1077

- Brundage JF, Williams VF, Stahlman S, et al. Incidence rates of malignant melanoma in relation to years of military service, overall and in selected military occupational groups, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2015. MMSR. 2017;24:8-14.

- Subramaniam P, Olsen CM, Thompson BS, et al, for the QSkin Sun and Health Study Investigators. Anatomical distributions of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in a population-based study in Queensland, Australia. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:175-182. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4070

- Lyford WH, Crotty A, Logemann NF. Sun exposure prevention practices within U.S. naval aviation. Mil Med. 2021;186:1169-1175. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab099

- Wood M, Raisanen T, Polcari I. Observational study of free public sunscreen dispenser use at a major US outdoor event. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:164-166.

- Schissel D. Operation shadow warrior: a quantitative analysis of the ultraviolet radiation protection demonstrated by various headgear. Mil Med. 2001;166:783-785.

- Milch JM, Logemann NF. Photoprotection prevents skin cancer: let’s make it fashionable to wear sun-protective clothing. Cutis. 2017;99:89-92.

- Association of Military Dermatologists. (n.d.). Military dermatology. https://militaryderm.org/military-dermatology/

- Newnam R, Le-Jenkins U, Rutledge C, et al. The association of skin cancer prevention knowledge, sun-protective attitudes, and sunprotective behaviors in a Navy population. Mil Med. 2024;189:1-7. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac285

Skin cancer is a major health concern for military service members, who experience notably higher incidence rates than the general population.1 Active-duty military personnel are particularly vulnerable to prolonged sun exposure due to deployments, specialized training, and everyday outdoor duties.1 Despite skin cancer being the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in active-duty service members,2 tracking and documenting the quantity and diversity of these risk factors remain limited. This knowledge gap comes at high cost, simultaneously impairing military medicine preventive measures while burdening the military health care system with substantial expenditures.3 These findings underscore the critical need for targeted surveillance, early-detection programs, and policy-driven interventions to mitigate these medical and economic concerns.

Skin cancer has been recognized as a major health risk to the military population for decades, yet incidence and prevalence remain high. This phenomenon is closely linked to the inherent responsibilities and expectations of active-duty military members, including outdoor physical training, field exercises, standing in formation, and outdoor working environments—all of which can occur during peak sunlight hours. These risks are further elevated at duty stations in geographic regions with high levels of UV exposure, such as those in tropical and arid regions of the world. Certain military occupational specialties and missions may further introduce unique risk factors; for instance, pilots with frequent high-altitude missions experience heightened UV exposure and melanoma risk.4 Secondary to compounding determinants, the aviation, diving, and nuclear subgroups of the military community are particularly vulnerable to skin cancer.5

Despite well-documented risks, considerable gaps remain in quantifying and analyzing variations in UV exposure across military occupations, duty locations, and operational roles. Factors such as the existence of over 150 distinct military occupational specialties, frequent geographic relocations, and routine work in austere environments contribute to a wide range of UV exposure profiles that remain insufficiently characterized. This lack of comprehensive exposure data hinders the development of large-scale, targeted skin cancer prevention strategies. Initial approaches to addressing these challenges include enhanced surveillance, education, and policy initiatives. The Table presents practical recommendations for military leadership to consider in implementing preventive measures for skin cancer. Herein, we outline broader systemic strategies to bridge knowledge gaps and address underrecognized occupational risk factors for skin cancer in military service members; these elements include proposed modifications to the electronic Periodic Health Assessment (ePHA) and the development of standardized, military-specific screening and prevention guidelines to support early detection and resource optimization.

Skin Cancer Education for Service Members

Sunscreen and Signage—Diligent primary prevention offers a promising avenue for mitigating skin cancer incidence in military service members. Basic education and precautionary messaging on photoprotection can be widely implemented to simultaneously educate service members on the dangers of sun exposure while reinforcing healthy behaviors in real time. Simple low-cost initiatives such as strategically placed visual signage reminding service members to apply sunscreen in high UV environments can support consistent sun-safe practices. Educational efforts also should emphasize proper sunscreen use, including application on high-risk anatomic sites (eg, the face, neck, scalp, dorsal hands, and ears) and the essentiality of using sufficient quantities of broad-spectrum sunscreen for effective protection. Incorporating this guidance into training materials, briefings, and visual reminders allow seamless integration of photoprotection into service members’ daily routines without compromising operational efficiency.6 Younger service members, who may be less likely to prioritize preventive behaviors, may be particularly responsive to sun safety reminders in training areas, bases, and deployment zones.7 Health fairs and orientation briefs in high-UV regions also offer potential opportunities for targeted education.

Resources for Sun Protection in the Military

Sunscreen—Although sunscreen is critical in minimizing the risk for UV-induced skin cancer, its widespread use in the military is hindered by practical challenges related to accessibility and the need for consistent reapplication; for instance, providing free sunscreen dispensers at institutions for staff working under intense or prolonged UV exposure may improve sunscreen accessibility and use.8 Including sunscreen in standard-issue gear offers another logical way to embed its use into operational readiness as part of the routine protective measures.

Uniform Modifications—Adapting military uniforms and practices to improve sun protection plays a critical role in reducing skin cancer risk. Targeted protective gear for commonly sun-exposed areas can help mitigate UV exposure. One practical option is the use of wide-brimmed headgear (eg, boonie hats), which provide more face and neck coverage than standard-issue military caps, or covers. The wide-brimmed headgear currently is only selectively authorized during specific scenarios, such as field operations and training exercises, or at the discretion of unit-level leadership. Wide-brimmed headgear, already used by many service members, has been associated with up to a 17% reduction in UV exposure to inadequately protected areas, potentially lowering skin cancer risk.9,10 Similarly, a “sleeves-down” policy—requiring sleeves to remain unrolled and covering the forearms during outdoor activities—offers a simple way to minimize sun exposure without necessitating additional gear. Other specialized clothing items, including UV-blocking neck gaiters, photoprotective clothing, and lightweight gloves, also may be appropriate for high-risk groups and can be implemented in a relatively straightforward manner.

Shade Structures and UV Index Monitoring—Aside from uniform adaptation, physical barrier intervention can further complement skin cancer prevention efforts in the military. Shade structures offer a straightforward way to reduce UV exposure during prolonged outdoor activities. Incorporating daily UV index monitoring into operational guidance can help inform adjustments to training schedules and guide the implementation of additional sun protection measures, such as mandatory sunscreen application, use of wide-brimmed hats, or increased access to shaded rest areas during heavy sunlight hours. Currently, outdoor physical training is restricted during periods of high heat index, measured via Wet Bulb Globe Temperature, to reduce heat-related injuries. We argue that avoidance of nonoperational outdoor activity during peak UV index hours also should be incorporated into standardized policies. This intervention is of particular benefit to service members stationed in regions with a high UV index year-round, such as those stationed in the Middle East, Guam, Okinawa, and southern coastal United States bases.

Policy Changes to Support Photoprotective Measures

Annual Risk Factor Screening‐Screening—Effective secondary prevention efforts by military dermatologists remain an important measure in reducing the burden of skin cancer among military personnel; however, these efforts have become increasingly challenging due to 2 main factors—the diversity of military occupational specialties and their associated unique occupational risks as well as the limited availability of military dermatologists across all branches (approximately 100 active-duty dermatologists for nearly 3 million service members).11 Therefore, targeted interventions that enhance risk assessment, refined screening protocols, and leveraging of existing military health networks can improve early skin cancer detection while optimizing resource allocation.

The ePHA is an online screening tool used annually by all service members to evaluate their overall health. Presently, the ePHA lacks specific questions to assess sun exposure and skin cancer risks. Integrating annual skin cancer risk factor assessments into the ePHA would offer a practical and straightforward approach to identifying at-risk individuals, as suggested by Newnam et al12 in 2022. Skin cancer risk factor assessments allow for targeted data collection related to sun exposure history, family history, and personal risk factors, which can be used to determine individualized risk stratification to assess the need for early secondary prevention measures and specialist referral. These ePHA data can also support population-based analyses to inform preventive strategies and address knowledge gaps related to high-risk exposures, such as extended field exercises or assignments in high-UV regions, that may impede effective skin cancer prevention.

Development of Military-Specific Screening Guidelines—Given the limited number of military dermatologists, a standardized risk-assessment tool could enhance early detection of skin cancer and streamline the referral process. We propose a military-specific skin cancer screening algorithm or risk nomogram that could help to consolidate risk factors into a clear and actionable framework for more efficient triage and appropriate allocation of dermatologic resources and manpower. This nomogram could be developed by military dermatologists and then implemented on a command level, affording primary care providers a useful tool to expedite evaluation of individuals at higher risk for skin cancer while simultaneously promoting judicious use of limited dermatology resources.

Although the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not universally recommend routine skin cancer screenings for asymptomatic adults, military service members are exposed to higher occupational risks than the general population, as previously mentioned. Currently, there is no standardized screening guideline across all military services due to the unique nature and exposure risks for each branch of service and their varied occupations; however, we propose the development of basic standardized screening guidelines by adapting the framework of the United States Preventive Services Task Force and adjusting for military-specific UV exposure and occupational risks to improve early detection of skin cancer. These guidelines could be updated and tailored appropriately when additional population-based data are collected and analyzed through ePHA.

Critiques and Limitations of Implementation

Several challenges and limitations must be considered when attempting to integrate large-scale preventive measures for skin cancer within the US military. A primary concern is the extent to which military resources should be allocated to prevention when off-duty sun exposure remains largely beyond institutional control. Although military health initiatives can address workplace risk through education and policy, individual decisions during both work and leisure time remain a major variable that cannot be feasibly controlled. Cultural and operational barriers also pose challenges; for instance, the US Marine Corps maintains a strong cultural identity tied to uniform appearance, making it difficult to implement widespread changes to clothing-based sun-protection measures. Institutional changes, particularly those involving uniforms, likely will face substantial administrative resistance and potential operational limitations. When broad uniform modifications are unattainable, a more feasible approach may be to encourage unit-level leadership to authorize and promote the frequent use of nonuniform protective measures.

Furthermore, integrating additional skin cancer risk questions into the already extensive ePHA means extra time required to complete the assessment; this adds to service members’ administrative burden, potentially leading to reduced timely compliance, rushed responses, and survey fatigue, which threaten data quality. If new items are to be included, they should be carefully selected for efficiency and clinical relevance. Existing validated questionnaires such as those from the study by Lyford et al7 published in 2021 can serve as a foundation.

Another critical limitation is access to dermatologic care for active-duty service members. Raising awareness of skin cancer risk without ensuring adequate resources may create ethical concerns, particularly in high-risk environments such as the Middle East and Indo-Pacific. Additionally, because skin cancer often develops years or decades after exposure, securing early buy-in from service members and their leaders can be challenging. These concerns make it clear that, while skin cancer prevention is important, implementing widespread measures is not straightforward and requires a practical and balanced approach.

Final Thoughts

Implementing prevention strategies for skin cancer in the military requires balancing evidence-based recommendations with the practical realities of military culture, resource limitations, and operational demands. Challenges remain for dermatologists in providing targeted recommendations due to the multifaceted nature of military roles, including over 150 Navy Military Occupational Specialties, limited familiarity with the unique UV exposure risks associated with each occupation, and variability in local and regional policies on uniform wear, physical training requirements, and other operational practices. Although targeted prevention measures are difficult to establish in the setting of these knowledge gaps, leveraging unit-level leadership to align with existing screening guidelines and optimizing primary prevention measures can be meaningful steps toward reducing skin cancer risk for military service members while maintaining mission readiness.

Skin cancer is a major health concern for military service members, who experience notably higher incidence rates than the general population.1 Active-duty military personnel are particularly vulnerable to prolonged sun exposure due to deployments, specialized training, and everyday outdoor duties.1 Despite skin cancer being the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in active-duty service members,2 tracking and documenting the quantity and diversity of these risk factors remain limited. This knowledge gap comes at high cost, simultaneously impairing military medicine preventive measures while burdening the military health care system with substantial expenditures.3 These findings underscore the critical need for targeted surveillance, early-detection programs, and policy-driven interventions to mitigate these medical and economic concerns.

Skin cancer has been recognized as a major health risk to the military population for decades, yet incidence and prevalence remain high. This phenomenon is closely linked to the inherent responsibilities and expectations of active-duty military members, including outdoor physical training, field exercises, standing in formation, and outdoor working environments—all of which can occur during peak sunlight hours. These risks are further elevated at duty stations in geographic regions with high levels of UV exposure, such as those in tropical and arid regions of the world. Certain military occupational specialties and missions may further introduce unique risk factors; for instance, pilots with frequent high-altitude missions experience heightened UV exposure and melanoma risk.4 Secondary to compounding determinants, the aviation, diving, and nuclear subgroups of the military community are particularly vulnerable to skin cancer.5

Despite well-documented risks, considerable gaps remain in quantifying and analyzing variations in UV exposure across military occupations, duty locations, and operational roles. Factors such as the existence of over 150 distinct military occupational specialties, frequent geographic relocations, and routine work in austere environments contribute to a wide range of UV exposure profiles that remain insufficiently characterized. This lack of comprehensive exposure data hinders the development of large-scale, targeted skin cancer prevention strategies. Initial approaches to addressing these challenges include enhanced surveillance, education, and policy initiatives. The Table presents practical recommendations for military leadership to consider in implementing preventive measures for skin cancer. Herein, we outline broader systemic strategies to bridge knowledge gaps and address underrecognized occupational risk factors for skin cancer in military service members; these elements include proposed modifications to the electronic Periodic Health Assessment (ePHA) and the development of standardized, military-specific screening and prevention guidelines to support early detection and resource optimization.

Skin Cancer Education for Service Members

Sunscreen and Signage—Diligent primary prevention offers a promising avenue for mitigating skin cancer incidence in military service members. Basic education and precautionary messaging on photoprotection can be widely implemented to simultaneously educate service members on the dangers of sun exposure while reinforcing healthy behaviors in real time. Simple low-cost initiatives such as strategically placed visual signage reminding service members to apply sunscreen in high UV environments can support consistent sun-safe practices. Educational efforts also should emphasize proper sunscreen use, including application on high-risk anatomic sites (eg, the face, neck, scalp, dorsal hands, and ears) and the essentiality of using sufficient quantities of broad-spectrum sunscreen for effective protection. Incorporating this guidance into training materials, briefings, and visual reminders allow seamless integration of photoprotection into service members’ daily routines without compromising operational efficiency.6 Younger service members, who may be less likely to prioritize preventive behaviors, may be particularly responsive to sun safety reminders in training areas, bases, and deployment zones.7 Health fairs and orientation briefs in high-UV regions also offer potential opportunities for targeted education.

Resources for Sun Protection in the Military

Sunscreen—Although sunscreen is critical in minimizing the risk for UV-induced skin cancer, its widespread use in the military is hindered by practical challenges related to accessibility and the need for consistent reapplication; for instance, providing free sunscreen dispensers at institutions for staff working under intense or prolonged UV exposure may improve sunscreen accessibility and use.8 Including sunscreen in standard-issue gear offers another logical way to embed its use into operational readiness as part of the routine protective measures.

Uniform Modifications—Adapting military uniforms and practices to improve sun protection plays a critical role in reducing skin cancer risk. Targeted protective gear for commonly sun-exposed areas can help mitigate UV exposure. One practical option is the use of wide-brimmed headgear (eg, boonie hats), which provide more face and neck coverage than standard-issue military caps, or covers. The wide-brimmed headgear currently is only selectively authorized during specific scenarios, such as field operations and training exercises, or at the discretion of unit-level leadership. Wide-brimmed headgear, already used by many service members, has been associated with up to a 17% reduction in UV exposure to inadequately protected areas, potentially lowering skin cancer risk.9,10 Similarly, a “sleeves-down” policy—requiring sleeves to remain unrolled and covering the forearms during outdoor activities—offers a simple way to minimize sun exposure without necessitating additional gear. Other specialized clothing items, including UV-blocking neck gaiters, photoprotective clothing, and lightweight gloves, also may be appropriate for high-risk groups and can be implemented in a relatively straightforward manner.

Shade Structures and UV Index Monitoring—Aside from uniform adaptation, physical barrier intervention can further complement skin cancer prevention efforts in the military. Shade structures offer a straightforward way to reduce UV exposure during prolonged outdoor activities. Incorporating daily UV index monitoring into operational guidance can help inform adjustments to training schedules and guide the implementation of additional sun protection measures, such as mandatory sunscreen application, use of wide-brimmed hats, or increased access to shaded rest areas during heavy sunlight hours. Currently, outdoor physical training is restricted during periods of high heat index, measured via Wet Bulb Globe Temperature, to reduce heat-related injuries. We argue that avoidance of nonoperational outdoor activity during peak UV index hours also should be incorporated into standardized policies. This intervention is of particular benefit to service members stationed in regions with a high UV index year-round, such as those stationed in the Middle East, Guam, Okinawa, and southern coastal United States bases.

Policy Changes to Support Photoprotective Measures

Annual Risk Factor Screening‐Screening—Effective secondary prevention efforts by military dermatologists remain an important measure in reducing the burden of skin cancer among military personnel; however, these efforts have become increasingly challenging due to 2 main factors—the diversity of military occupational specialties and their associated unique occupational risks as well as the limited availability of military dermatologists across all branches (approximately 100 active-duty dermatologists for nearly 3 million service members).11 Therefore, targeted interventions that enhance risk assessment, refined screening protocols, and leveraging of existing military health networks can improve early skin cancer detection while optimizing resource allocation.

The ePHA is an online screening tool used annually by all service members to evaluate their overall health. Presently, the ePHA lacks specific questions to assess sun exposure and skin cancer risks. Integrating annual skin cancer risk factor assessments into the ePHA would offer a practical and straightforward approach to identifying at-risk individuals, as suggested by Newnam et al12 in 2022. Skin cancer risk factor assessments allow for targeted data collection related to sun exposure history, family history, and personal risk factors, which can be used to determine individualized risk stratification to assess the need for early secondary prevention measures and specialist referral. These ePHA data can also support population-based analyses to inform preventive strategies and address knowledge gaps related to high-risk exposures, such as extended field exercises or assignments in high-UV regions, that may impede effective skin cancer prevention.

Development of Military-Specific Screening Guidelines—Given the limited number of military dermatologists, a standardized risk-assessment tool could enhance early detection of skin cancer and streamline the referral process. We propose a military-specific skin cancer screening algorithm or risk nomogram that could help to consolidate risk factors into a clear and actionable framework for more efficient triage and appropriate allocation of dermatologic resources and manpower. This nomogram could be developed by military dermatologists and then implemented on a command level, affording primary care providers a useful tool to expedite evaluation of individuals at higher risk for skin cancer while simultaneously promoting judicious use of limited dermatology resources.

Although the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not universally recommend routine skin cancer screenings for asymptomatic adults, military service members are exposed to higher occupational risks than the general population, as previously mentioned. Currently, there is no standardized screening guideline across all military services due to the unique nature and exposure risks for each branch of service and their varied occupations; however, we propose the development of basic standardized screening guidelines by adapting the framework of the United States Preventive Services Task Force and adjusting for military-specific UV exposure and occupational risks to improve early detection of skin cancer. These guidelines could be updated and tailored appropriately when additional population-based data are collected and analyzed through ePHA.

Critiques and Limitations of Implementation

Several challenges and limitations must be considered when attempting to integrate large-scale preventive measures for skin cancer within the US military. A primary concern is the extent to which military resources should be allocated to prevention when off-duty sun exposure remains largely beyond institutional control. Although military health initiatives can address workplace risk through education and policy, individual decisions during both work and leisure time remain a major variable that cannot be feasibly controlled. Cultural and operational barriers also pose challenges; for instance, the US Marine Corps maintains a strong cultural identity tied to uniform appearance, making it difficult to implement widespread changes to clothing-based sun-protection measures. Institutional changes, particularly those involving uniforms, likely will face substantial administrative resistance and potential operational limitations. When broad uniform modifications are unattainable, a more feasible approach may be to encourage unit-level leadership to authorize and promote the frequent use of nonuniform protective measures.

Furthermore, integrating additional skin cancer risk questions into the already extensive ePHA means extra time required to complete the assessment; this adds to service members’ administrative burden, potentially leading to reduced timely compliance, rushed responses, and survey fatigue, which threaten data quality. If new items are to be included, they should be carefully selected for efficiency and clinical relevance. Existing validated questionnaires such as those from the study by Lyford et al7 published in 2021 can serve as a foundation.

Another critical limitation is access to dermatologic care for active-duty service members. Raising awareness of skin cancer risk without ensuring adequate resources may create ethical concerns, particularly in high-risk environments such as the Middle East and Indo-Pacific. Additionally, because skin cancer often develops years or decades after exposure, securing early buy-in from service members and their leaders can be challenging. These concerns make it clear that, while skin cancer prevention is important, implementing widespread measures is not straightforward and requires a practical and balanced approach.

Final Thoughts

Implementing prevention strategies for skin cancer in the military requires balancing evidence-based recommendations with the practical realities of military culture, resource limitations, and operational demands. Challenges remain for dermatologists in providing targeted recommendations due to the multifaceted nature of military roles, including over 150 Navy Military Occupational Specialties, limited familiarity with the unique UV exposure risks associated with each occupation, and variability in local and regional policies on uniform wear, physical training requirements, and other operational practices. Although targeted prevention measures are difficult to establish in the setting of these knowledge gaps, leveraging unit-level leadership to align with existing screening guidelines and optimizing primary prevention measures can be meaningful steps toward reducing skin cancer risk for military service members while maintaining mission readiness.

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancerincidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Lee T, Taubman SB, Williams VF. Incident diagnoses of non-melanoma skin cancer, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005-2014. MSMR. 2016;23:2-6.

- Krivda KR, Watson NL, Lyford WH, et al. The burden of skin cancer in the military health system, 2017-2022. Cutis. 2024;113:200-215. doi:10.12788/cutis.1015

- Sanlorenzo M, Wehner MR, Linos E, et al. The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:51-58. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1077

- Brundage JF, Williams VF, Stahlman S, et al. Incidence rates of malignant melanoma in relation to years of military service, overall and in selected military occupational groups, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2015. MMSR. 2017;24:8-14.

- Subramaniam P, Olsen CM, Thompson BS, et al, for the QSkin Sun and Health Study Investigators. Anatomical distributions of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in a population-based study in Queensland, Australia. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:175-182. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4070

- Lyford WH, Crotty A, Logemann NF. Sun exposure prevention practices within U.S. naval aviation. Mil Med. 2021;186:1169-1175. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab099

- Wood M, Raisanen T, Polcari I. Observational study of free public sunscreen dispenser use at a major US outdoor event. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:164-166.

- Schissel D. Operation shadow warrior: a quantitative analysis of the ultraviolet radiation protection demonstrated by various headgear. Mil Med. 2001;166:783-785.

- Milch JM, Logemann NF. Photoprotection prevents skin cancer: let’s make it fashionable to wear sun-protective clothing. Cutis. 2017;99:89-92.

- Association of Military Dermatologists. (n.d.). Military dermatology. https://militaryderm.org/military-dermatology/

- Newnam R, Le-Jenkins U, Rutledge C, et al. The association of skin cancer prevention knowledge, sun-protective attitudes, and sunprotective behaviors in a Navy population. Mil Med. 2024;189:1-7. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac285

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancerincidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Lee T, Taubman SB, Williams VF. Incident diagnoses of non-melanoma skin cancer, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005-2014. MSMR. 2016;23:2-6.

- Krivda KR, Watson NL, Lyford WH, et al. The burden of skin cancer in the military health system, 2017-2022. Cutis. 2024;113:200-215. doi:10.12788/cutis.1015

- Sanlorenzo M, Wehner MR, Linos E, et al. The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:51-58. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1077

- Brundage JF, Williams VF, Stahlman S, et al. Incidence rates of malignant melanoma in relation to years of military service, overall and in selected military occupational groups, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2015. MMSR. 2017;24:8-14.

- Subramaniam P, Olsen CM, Thompson BS, et al, for the QSkin Sun and Health Study Investigators. Anatomical distributions of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in a population-based study in Queensland, Australia. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:175-182. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4070

- Lyford WH, Crotty A, Logemann NF. Sun exposure prevention practices within U.S. naval aviation. Mil Med. 2021;186:1169-1175. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab099

- Wood M, Raisanen T, Polcari I. Observational study of free public sunscreen dispenser use at a major US outdoor event. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:164-166.

- Schissel D. Operation shadow warrior: a quantitative analysis of the ultraviolet radiation protection demonstrated by various headgear. Mil Med. 2001;166:783-785.

- Milch JM, Logemann NF. Photoprotection prevents skin cancer: let’s make it fashionable to wear sun-protective clothing. Cutis. 2017;99:89-92.

- Association of Military Dermatologists. (n.d.). Military dermatology. https://militaryderm.org/military-dermatology/

- Newnam R, Le-Jenkins U, Rutledge C, et al. The association of skin cancer prevention knowledge, sun-protective attitudes, and sunprotective behaviors in a Navy population. Mil Med. 2024;189:1-7. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac285

Bridging the Knowledge-Action Gap in Skin Cancer Prevention Among US Military Personnel

Bridging the Knowledge-Action Gap in Skin Cancer Prevention Among US Military Personnel

PRACTICE POINTS

- Military personnel face elevated skin cancer risks due to prolonged occupational UV exposure.

- Medical providers can partner with unit-level leadership to implement low-cost interventions such as shade structures and uniform modifications.

- Annual sun exposure risk assessments should be integrated into the military Electronic Periodic Health Assessment for targeted screening and early intervention of risk factors.

- Photoprotective gear and signage in high—UV index areas can improve service member awareness and adherence to preventive measures.