User login

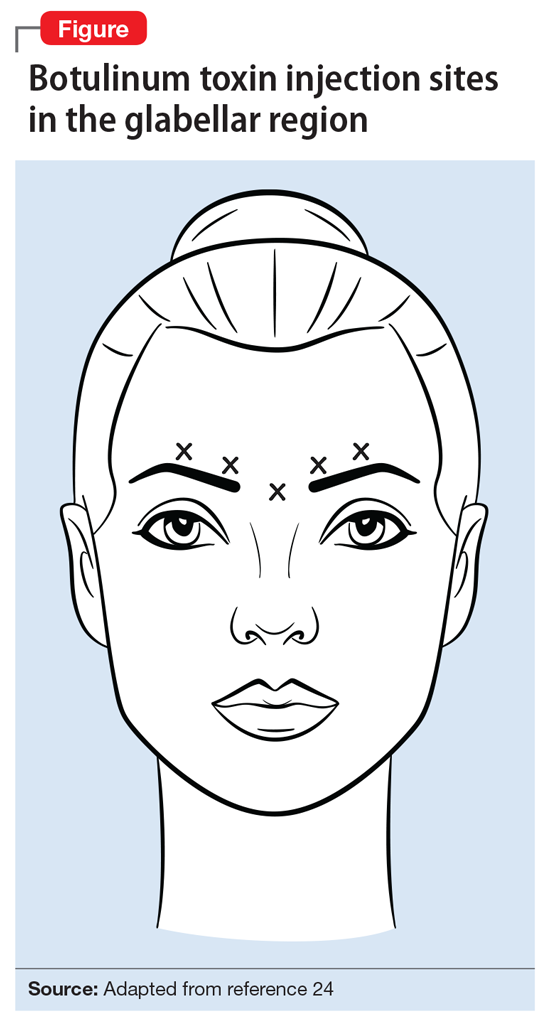

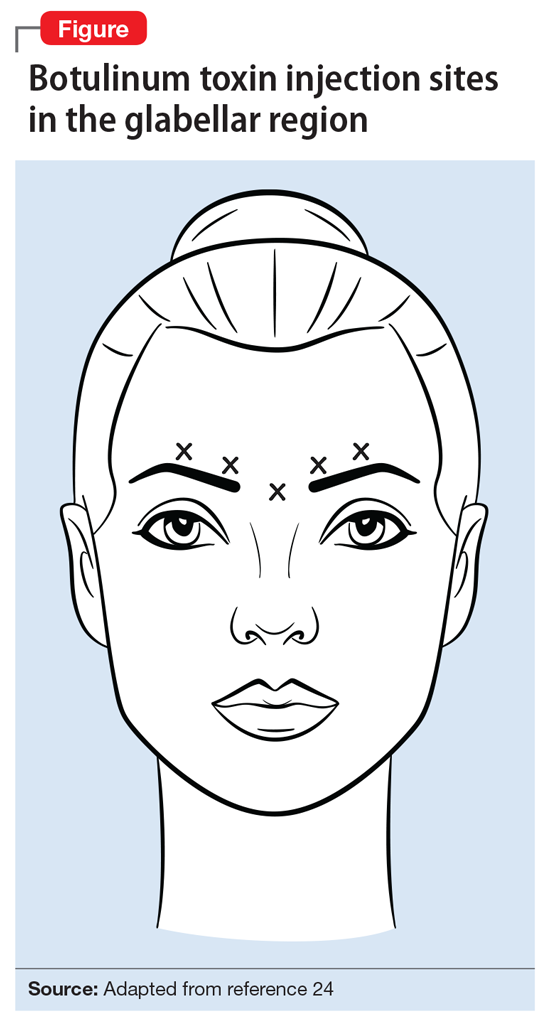

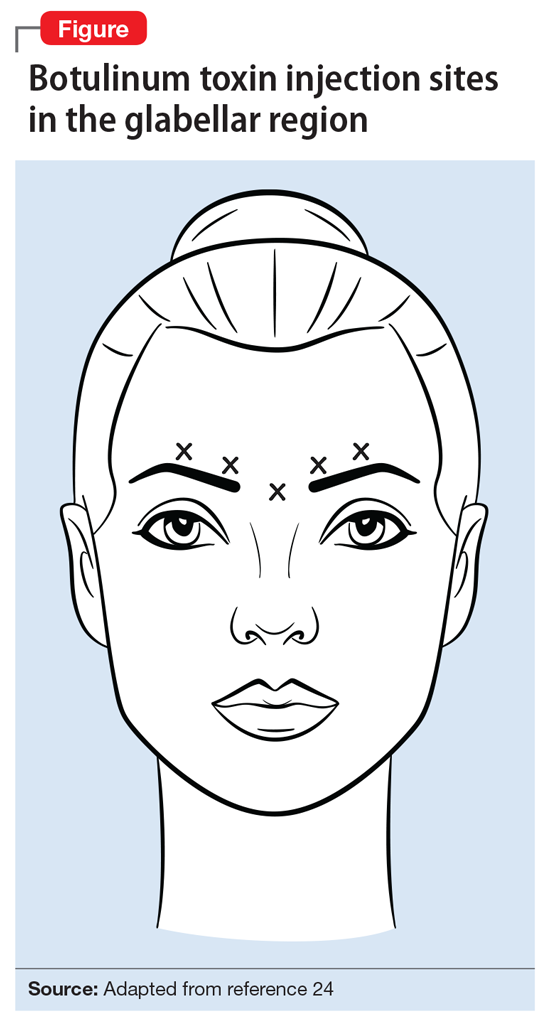

Botulinum toxin, a potent neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, has been used as treatment for a variety of medical indications for more than 25 years (Box1-12). Recently, researchers have been exploring the role of botulinum toxin in psychiatry, primarily as an adjunctive treatment for depression, but also for several other possible indications. Several studies, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), have provided evidence that glabellar botulinum toxin injections may be a safe and effective treatment for depression. In this article, we provide an update on the latest clinical trials that evaluated botulinum toxin for depression, and also summarize the evidence regarding other potential clinical psychiatric applications of botulinum toxin.

Several RCTs suggest efficacy for depression

The use of botulinum toxin to treat depression is based on the facial feedback hypothesis, which was first proposed by Charles Darwin in 187213 and further elaborated by William James,14,15 who emphasized the importance of the sensation of bodily changes in emotion. Contrary to the popular belief that emotions trigger physiological changes in the body, James postulated that peripheral bodily changes secondary to stimuli perception would exert a sensory feedback, generating emotions. The manipulation of human facial expression with an expression that is associated with a particular emotion (eg, holding a pen with teeth, leading to risorius/zygomaticus muscles contraction and a smile simulation) was found to influence participants’ affective responses in the presence of emotional stimuli (eg, rating cartoons as funnier), reinforcing the facial-feedback hypothesis.16,17

From a neurobiologic standpoint, facial botulinum toxin A (BTA) injections in rats were associated with increased serotonin and norepinephrine concentrations in the hypothalamus and striatum, respectively.18 Moreover, amygdala activity in response to angry vs happy faces, measured via functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), was found to be attenuated after BTA applications to muscles involved in angry facial expressions.19,20 Both the neurotransmitters as well as the aforementioned brain regions have been implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.21,22

Compared with those in the placebo group, participants in the BTA group had a higher response rate as measured by the HAM-D17 at 6 weeks after treatment (P = .02), especially female patients (P = .002). Response to BTA, defined as ≥50% reduction on the HAM-D17, occurred within 2 weeks, and lasted another 6 weeks before slightly wearing off. Assessment of the CSS-GFL showed a statistically significant change at 6 weeks (P < .001). This small study failed, however, to show significant remission rates (HAM-D17 ≤7) in the BTA group compared with placebo.

Box

Botulinum toxin is a potent neurotoxin from Clostridium botulinum. Its potential for therapeutic use was first noticed in 1817 by physician Justinus Kerner, who coined the term botulism.1 In 1897, bacteriologist Emile van Ermengem isolated the causative bacterium C. botulinum.2 It was later discovered that the toxin induces muscle paralysis by inhibiting acetylcholine release from presynaptic motor neurons at the neuromuscular junction3 and was then mainly investigated as a treatment for medical conditions involving excessive or abnormal muscular contraction.

In 1989, the FDA approved botulinum toxin A (BTA) for the treatment of strabismus, blepharospasm, and other facial nerve disorders. In 2000, both BTA and botulinum toxin B (BTB) were FDA-approved for the treatment of cervical dystonia, and BTA was approved for the cosmetic treatment of frown lines (glabellar, canthal, and forehead lines).4 Other approved clinical indications for BTA include urinary incontinence due to detrusor overactivity associated with a neurologic condition such as spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis; prophylaxis of headaches in chronic migraine patients; treatment of both upper and lower limb spasticity; severe axillary hyperhidrosis inadequately managed by topical agents; and the reduction of the severity of abnormal head position and neck pain.5 Its anticholinergic effects have been also investigated for treatment of hyperhidrosis as well as sialorrhea caused by neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.6-8 Multiple studies have shown that botulinum toxin can alleviate spasms of the gastrointestinal tract, aiding patients with dysphagia and achalasia.9-11 There is also growing evidence supporting the use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of chronic pain, including non-migraine types of headaches such as tension headaches; myofascial syndrome; and neuropathic pain.12

Continue to: In a second RCT involving 74 patients with depression...

In a second RCT involving 74 patients with depression, Finzi and Rosenthal25 observed statistically significant response and remission rates in participants who received BTA injections, as measured by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). Participants were given either BTA or saline injections and assessed at 3 visits across 6 weeks using the MADRS, CGI, and Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). Photographs of participants’ facial expressions were assessed using frown scores to see whether changes in facial expression were associated with improvement of depression.

This study was able to reproduce on a larger scale the results observed by Wollmer et al.23 It found a statistically significant increase in the rate of remission (MADRS ≤10) at 6 weeks following BTA injections (27%, P < .02), and that even patients who were not resistant to antidepressants could benefit from BTA. However, although there was an observable trend in improvement of frown scores associated with improved depression scores, the correlation between these 2 variables was not statistically significant.

In a crossover RCT, Magid et al26 observed the response to BTA vs placebo saline injections in 30 patients with moderate to severe frown lines. The study lasted 24 weeks; participants switched treatments at Week 12. Mood improvement was assessed using the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-21), BDI, and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Compared with patients who received placebo injections, those treated with BTA injections showed statistically significant response rates, but not remission rates. This study demonstrated continued improvement throughout the 24 weeks in participants who initially received BTA injections, despite having received placebo for the last 12 weeks, by which time the cosmetic effects of the initial injection had worn off. This suggests that the antidepressant effects of botulinum toxin may not depend entirely on its paralytic effects, but also on its impact on the neurotransmitters involved in the pathophysiology of depression.18 By demonstrating improvement in the placebo group once they were started on botulinum toxin, this study also was able to exclude the possibility that other variables may be responsible for the difference in the clinical course between the 2 groups. However, this study was limited by a small sample size, and it only included participants who had moderate to severe frown lines at baseline.

Zamanian et al27 examined the therapeutic effects of BTA injections in 28 Iranian patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) diagnosed according to DSM-5 criteria. At 6 weeks, there were significant improvements in BDI scores in patients who received BTA vs those receiving placebo. However, these changes were demonstrated at 6 weeks (not as early as 2 weeks), and patients didn’t achieve remission.

A large-scale, multicenter U.S. phase II RCT investigated the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of a single administration of 2 different doses of BTA (30 units or 50 units) as monotherapy for the treatment of moderate to severe depression in 258 women.28 Effects on depression were measured at 3, 6, and 9 weeks using the MADRS. Participants who received the 30-unit injection showed statistically significant improvement at 3 weeks (

More recently, in a case series, Chugh et al30 examined the effect of BTA in 42 patients (55% men) with severe treatment-resistant depression. Participants were given BTA injections in the glabellar region as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants and observed for at least 6 weeks. Depression severity was measured using HAM-D17, MADRS, and BDI at baseline and at 3 weeks. Changes in glabellar frown lines also were assessed using the CSS-GFL. The authors reported statistically significant improvements in HAM-D17 (

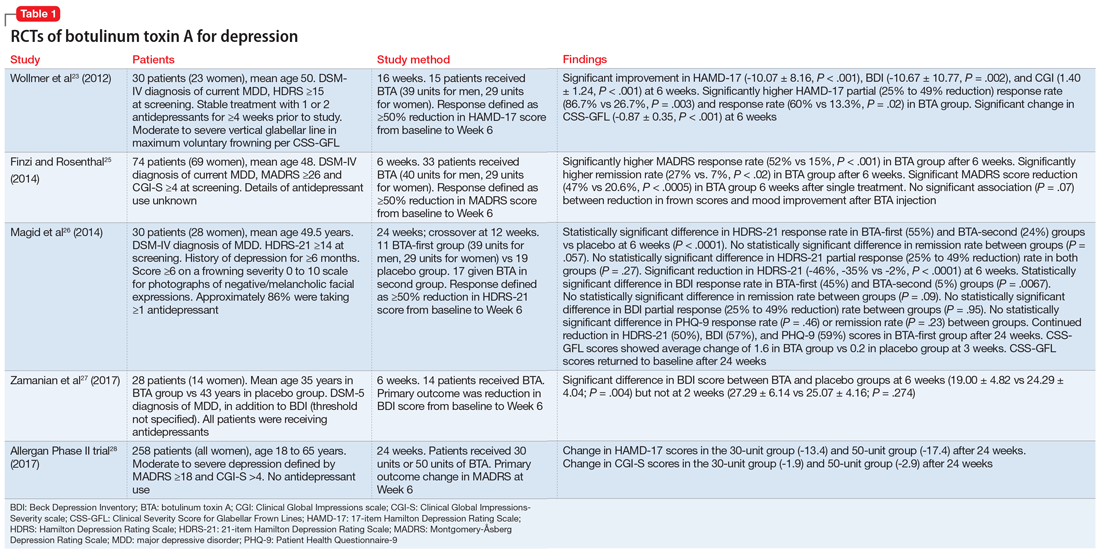

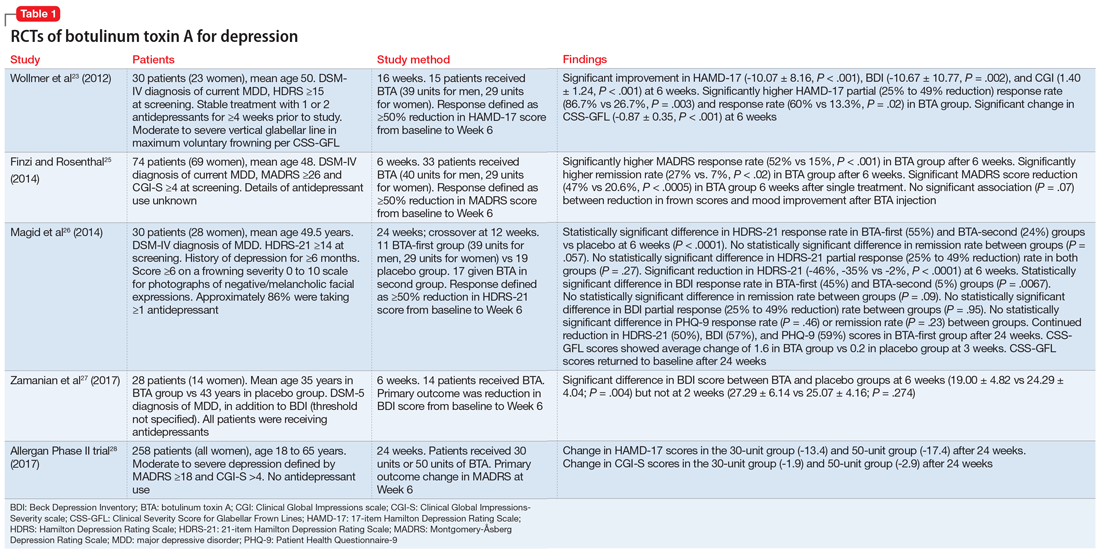

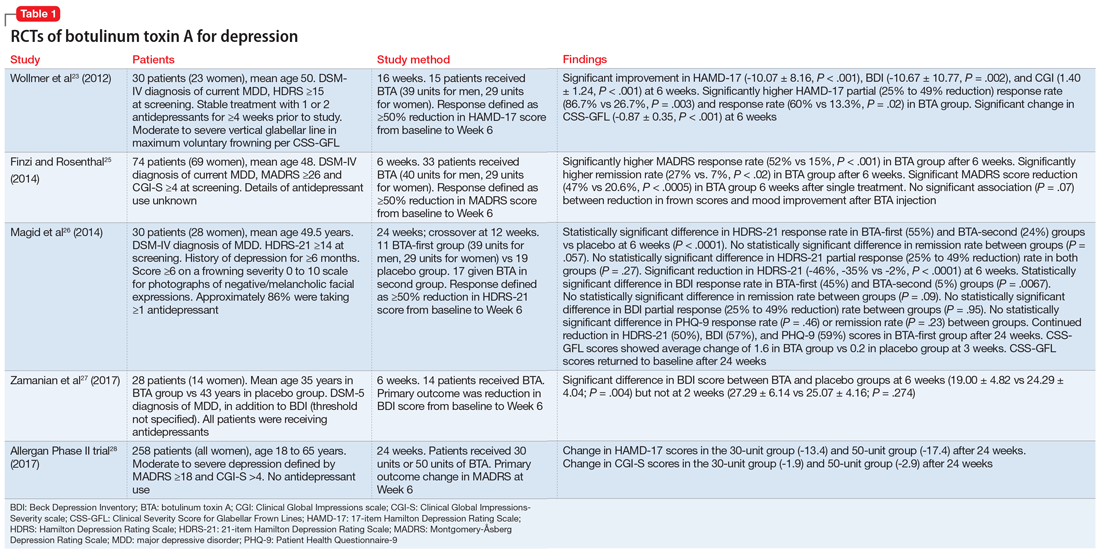

A summary of the RCTs of BTA for treating depression appears in Table 1.23,25-28

Continue to: Benefits for other psychiatric indications

Benefits for other psychiatric indications

Borderline personality disorder. In a case series of 6 women, BTA injections in the glabellar region were reported to be particularly effective for the treatment of borderline personality disorder symptoms that were resistant to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.31 Two to 6 weeks after a 29-unit injection, borderline personality disorder symptoms as measured by the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder and/or the Borderline Symptom List were shown to significantly improve by 49% to 94% from baseline (P ≤ .05). These findings emphasize the promising therapeutic role of BTA on depressive symptoms concomitant with the emotional lability, impulsivity, and negative emotions that usually characterize this personality disorder.31,32 A small sample size and lack of a placebo comparator are limitations of this research.

Neuroleptic-induced sialorrhea. Botulinum toxin injections in the salivary glands have been investigated for treating clozapine-induced sialorrhea because they are thought to directly inhibit the release of acetylcholine from salivary glands. One small RCT that used botulinum toxin B (BTB)33 and 1 case report that used BTA34 reported successful reduction in hypersalivation, with doses ranging from 150 to 500 units injected in each of the parotid and/or submandibular glands bilaterally. Although the treatment was well tolerated and lasted up to 16 weeks, larger studies are needed to replicate these findings.33-35

Orofacial tardive dyskinesia. Several case reports of orofacial tardive dyskinesia, including lingual dyskinesia and lingual protrusion dystonia, have found improvements in hyperkinetic movements following muscular BTA injections, such as in the genioglossus muscle in the case of tongue involvement.36-39 These cases were, however, described in the literature before the recent FDA approval of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 inhibitors valbenazine and deutetrabenazine for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia.40,41

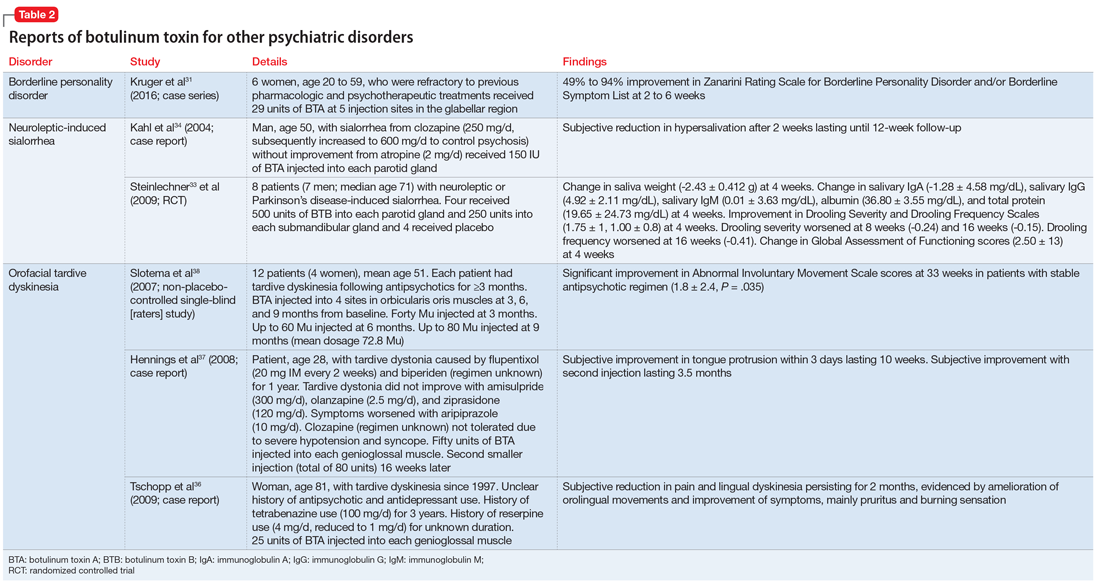

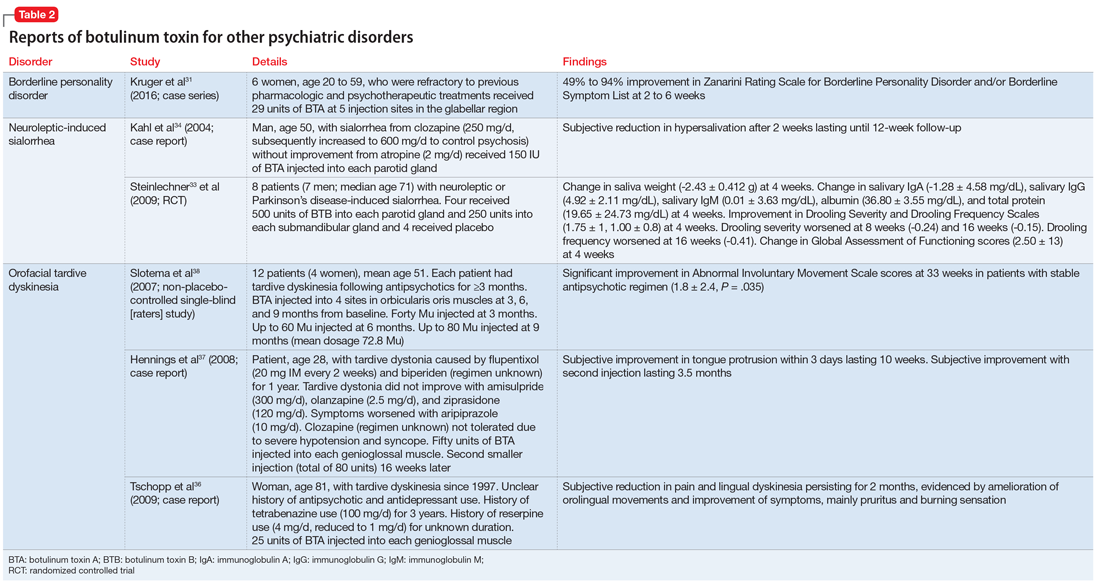

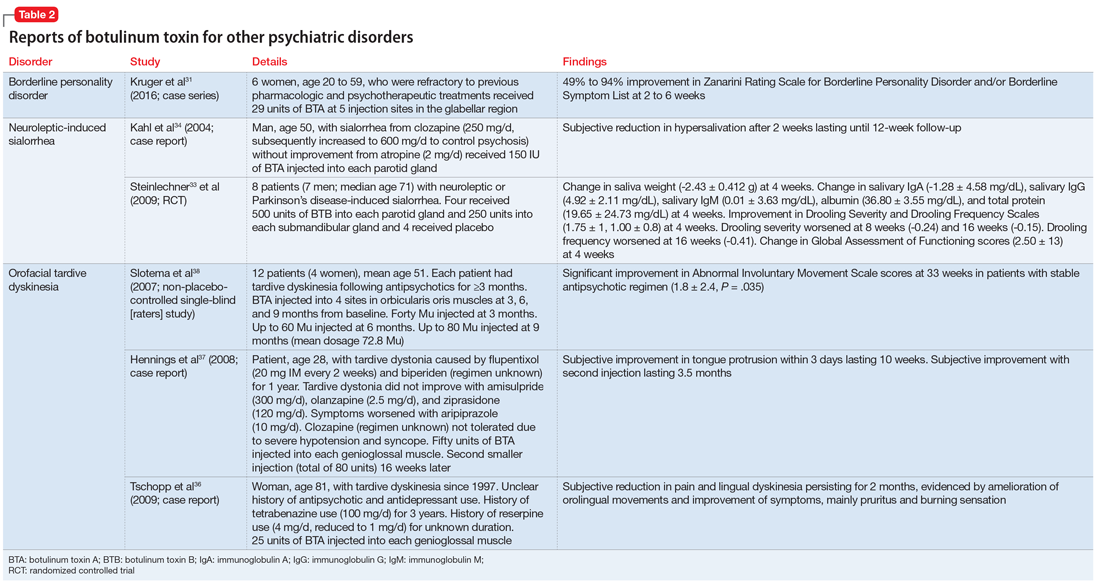

Studies examining botulinum toxin’s application in areas of psychiatry other than depression are summarized in Table 2.31,33,36-38

Continue to: Promising initial findings but multiple limitations

Promising initial findings but multiple limitations

Although BTA injections have been explored as a potential treatment for several psychiatric conditions, the bulk of recent evidence is derived from studies in patients with depressive disorders. BTA injections in the glabellar regions have been shown in small RCTs to be well-tolerated with overall promising improvement of depressive symptoms, optimally 6 weeks after a single injection. Moreover, BTA has been shown to be safe and long-lasting, which would be convenient for patients and might improve adherence to therapy.42-44 BTA’s antidepressant effects were shown to be independent of frown line severity or patient satisfaction with cosmetic effects.45 The trials by Wollmer et al,23 Finzi and Rosenthal,25 and Magid et al26 mainly studied BTA as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants in patients with ongoing unipolar depression. However, Finzi and Rosenthal25 included patients who were not medicated at the time of the study.

Pooled analysis of these 3 RCTs found that patients who received BTA monotherapy improved equally to those who received it as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants. Overall, on primary endpoint measures, a response rate of 54.2% was obtained in the BTA group compared with 10.7% among patients who received placebo saline injections (odds ratio [OR] 11.1, 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.3 to 28.8, number needed to treat [NNT] = 2.3) and a remission rate of 30.5% with BTA compared with 6.7% with placebo (OR 7.3, 95 % CI, 2.4 to 22.5, NNT = 4.2).46 However, remission rates tend to be higher in the augmentation groups, and so further studies are needed to compare both treatment strategies.

Nevertheless, these positive findings have been recently challenged by the results of the largest U.S. multicenter phase II RCT,28 which failed to find a significant antidepressant effect at 6 weeks with the 30-unit BTA injection, and also failed to prove a dose-effect relationship, as the 50-unit injection wasn’t superior to the lower dose and didn’t significantly differ from placebo. One hypothesis to explain this discrepancy may be the difference in injection sites between the treatment and placebo groups.47 Future studies need to address the various limitations of earlier clinical trials that mainly yielded promising results with BTA.

A major concern is the high rate of unblinding of participants and researchers in BTA trials, as the cosmetic effects of botulinum toxin injections make them easy to distinguish from saline injections. Ninety percent of participants in the Wollmer et al study23 were able to correctly guess their group allocation, while 60% of evaluators guessed correctly. Finzi and Rozenthal25 reported 52% of participants in the BTA group, 46% in the placebo group, and 73% of evaluators correctly guessed their allocation. Magid et al26 reported 75% of participants were able to guess the order of intervention they received. The high unblinding rates in these trials remains a significant limitation. There is a concern that this may lead to an underestimation of the placebo effect relative to clinical improvement, thus causing inflation of outcome differences between groups. Although various methods have been tried to minimize evaluator unblinding, such as placing surgical caps on participants’ faces during visits to hide the glabellar region, better methods need to be implemented to prevent unblinding of both raters and participants.

Furthermore, except for the multicenter phase II trial, most studies have been conducted in small samples, which limits their statistical power. Larger controlled trials will be needed to replicate the positive findings obtained in smaller RCTs.

Another limitation is that the majority of the well-designed RCTs were conducted in populations that were predominantly female, which makes it difficult to reliably assess treatment efficacy in men. This may be because cosmetic treatment with botulinum toxin injection is more favorably received by women than by men. A recent comparison48 of the studies by Wollmer et al23 and Finzi and Rosenthal25 discussed an interesting observation. Wollmer et al did not explicitly mention botulinum toxin when recruiting for the study, while Finzi and Rosenthal did. While approximately a quarter of the participants in the Wollmer et al study were male, Finzi and Rosenthal attracted an almost entirely female population. Perhaps there is a potential bias for females to be more attracted to these studies due to the secondary gain of receiving a cosmetic procedure.

In an attempt to understand predictors of positive response to botulinum toxin in patients with depression, Wollmer et al49 conducted a follow-up study in which they reassessed the data obtained from their initial RCT using the HAM-D agitation item scores to separate the 15 participants who received BTA into low-agitation (≤1 score on agitation item of the HAM-D scale) and high-agitation (≥2 score on agitation item of the HAM-D scale) groups. They found that the 9 participants who responded to BTA treatment had significantly higher baseline agitation scores than participants who did not respond (1.56 ± 0.88 vs 0.33 ± 0.52, P = .01). All of the participants who presented with higher agitation levels experienced response, compared with 40% of those with lower agitation levels (P = .04), although there was no significant difference in magnitude of improvement (14.2 ± 1.92 vs 8.0 ± 9.37, P = .07). The study added additional support to the facial feedback hypothesis, as it links the improvement of depression to facial muscle activation targeted by the injections. It also introduced a potential predictor of response to botulinum toxin treatment, highlighting potential factors to consider when enrolling patients in future investigations.

The case series of patients with borderline personality disorder31 also shed light on the potential positive effect of BTA treatment for a particular subtype of patients with depression—those with comorbid emotional instability—to consider as a therapeutic target for the future. Hence, inclusion criteria for future trials might potentially include patient age, gender, existence/quantification of prominent frown lines at baseline, severity of MDD, duration of depression, and personality characteristics of enrolled participants.

In conclusion, BTA injections appear promising as a treatment for depression as well as for other psychiatric disorders. Future studies should focus on identifying optimal candidates for this innovative treatment modality. Furthermore, BTA dosing and administration strategies (monotherapy vs adjunctive treatment to antidepressants) need to be further explored. As retrograde axonal transport of botulinum toxin has been demonstrated in animal studies, it would be interesting to further examine its effects in the human CNS to enhance our knowledge of the pathophysiology of botulinum and its potential applications in psychiatry.50

Bottom Line

Botulinum toxin shows promising antidepressant effects and may have a role in the treatment of several other psychiatric disorders. More research is needed to address limitations of previous studies and to establish an adequate treatment regimen.

Related Resources

- Wollmer MA, Magid M, Kruger TH. Botulinum toxin treatment in depression. In: Bewley A, Taylor RE, Reichenberg JS, et al (eds). Practical psychodermatology. Oxford, UK: Wiley; 2014.

- Wollmer MA, Neumann I, Magid M. et al. Shrink that frown! Botulinum toxin therapy is lifting the face of psychiatry. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153(4):540-548.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Biperiden • Akineton

Botulinum toxin A • Botox

Botulinum toxin B • Myobloc

Clozapine • Clozaril

Deutetrabenazine • Austedo

Flupentixol • Prolixin

Imipramine • Tofranil

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Reserpine • Serpalan, Serpasil

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Valbenazine • Ingrezza

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Erbguth FJ, Naumann M. Historical aspects of botulinum toxin. Justinus Kerner (1786-1862) and the “sausage” poison. Neurology. 1999;53(8):1850-1853.

2. Devriese PP. On the discovery of Clostridium botulinum. J History Neurosci. 1999;8(1):43-50.

3. Burgen ASV, Dickens F, Zatman LJ. The action of botulinum toxin on the neuro-muscular junction. J Physiol. 1949;109(1-2):10-24.

4. Jankovic J. Botulinum toxin in clinical practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(7):951-957.

5. BOTOX (OnabotulinumtoxinA) [package insert]. Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA; 2015.

6. Saadia D, Voustianiouk A, Wang AK, et al. Botulinum toxin type A in primary palmar hyperhidrosis. Randomized, single-blind, two-dose study. Neurology. 2001;57(11):2095-2099.

7. Naumann MK, Lowe NJ. Effect of botulinum toxin type A on quality of life measures in patients with excessive axillary sweating: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(6):1218-1226.

8. Giess R, Naumann M, Werner E, et al. Injections of botulinum toxin A into the salivary glands improve sialorrhea in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69(1):121-123.

9. Restivo DA, Palmeri A, Marchese-Ragona R. Botulinum toxin for cricopharyngeal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1174-1175.

10. Pasricha PJ, Ravich WJ, Hendrix T, et al. Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia. N Engl J Med. 1995(12);322:774-778.

11. Schiano TD, Parkman HP, Miller LS, et al. Use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of achalasia. Dig Dis. 1998;16(1):14-22.

12. Sim WS. Application of botulinum toxin in pain management. Korean J Pain. 2011;24(1):1-6.

13. Darwin C. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London, UK: John Murray; 1872:366.

14. James W. The principles of psychology, vol. 2. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company; 1890.

15. James W. II. —What is an emotion? Mind. 1884;os-IX(34):188-205.

16. Strack R, Martin LL, Stepper S. Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of facial expressions: a nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(5):768-777.

17. Larsen RJ, Kasimatis M, Frey K. Facilitating the furrowed brow: an unobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis applied to unpleasant affect. Cogn Emot. 1992;6(5):321-338.

18. Ibragic S, Matak I, Dracic A, et al. Effects of botulinum toxin type A facial injection on monoamines and their metabolites in sensory, limbic, and motor brain regions in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2016;617:213-217.

19. Hennenlotter A, Dresel C, Castrop F, et al. The link between facial feedback and neural activity within central circuitries of emotion—new insights from botulinum toxin-induced denervation of frown muscles. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(3):537-42

20. Kim MJ, Neta M, Davis FC, et al. Botulinum toxin-induced facial muscle paralysis affects amygdala responses to the perception emotional expressions: preliminary findings from an A-B-A design. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2014;4:11.

21. Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, et al. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002;34(1):13-25.

22. Pandya M, Altinay M, Malone DA Jr, et al. Where in the brain is depression? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(6):634-642.

23. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:574-581.

24. BOTOX Cosmetic [prescribing information]. Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA; 2017.

25. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA; a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

26. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. The treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24 week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

27. Zamanian A, Ghanbari Jolfaei A, Mehran G, et al. Efficacy of botox versus placebo for treatment of patients with major depression. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(7):982-984.

28. Allergan. OnabotulinumtoxinA as treatment for major depressive disorder in adult females. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02116361. Accessed October 26, 2018.

29. Allergan. Allergan reports topline phase II data supporting advancement of BOTOX® (onabotulinumtoxinA) for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). April 5, 2017. https://www.allergan.com/news/news/thomson-reuters/allergan-reports-topline-phase-ii-data-supporting. Accessed October 26, 2018.

30. Chugh S, Chhabria A, Jung S, et al. Botulinum toxin as a treatment for depression in a real-world setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(1):15-20.

31. Kruger TH, Magid M, Wollmer MA. Can botulinum toxin help patients with borderline personality disorder? Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(9):940-941.

32. Baumeister JC, Papa G, Foroni F. Deeper than skin deep – the effect of botulinum toxin-A on emotion processing. Toxicon. 2016;119:86-90.

33. Steinlechner S, Klein C, Moser A, et al. Botulinum toxin B as an effective and safe treatment for neuroleptic-induced sialorrhea. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010;207(4):593-597.

34. Kahl KG, Hagenah J, Zapf S, et al. Botulinum toxin as an effective treatment of clozapine-induced hypersalivation. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;173(1-2):229-230.

35. Bird AM, Smith TL, Walton AE. Current treatment strategies for clozapine-induced sialorrhea. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(5):667-675.

36. Tschopp L, Salazar Z, Micheli F. Botulinum toxin in painful tardive dyskinesia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(3):165-166.

37. Hennings JM, Krause E, Bötzel K, et al. Successful treatment of tardive lingual dystonia with botulinum toxin: case report and review of the literature. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(5):1167-1171.

38. Slotema CW, van Harten PN, Bruggeman R, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of orofacial tardive dyskinesia: a single blind study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(2):507-509.

39. Esper CD, Freeman A, Factor SA. Lingual protrusion dystonia: frequency, etiology and botulinum toxin therapy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(7):438-441.

40. Seeberger LC, Hauser RA. Valbenazine for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(12):1279-1287.

41. Citrome L. Deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved novel medication—What is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71(11):e13030.

42. Brin MF, Boodhoo TI, Pogoda JM, et al. Safety and tolerability of onabotulinumtoxinA in the tretment of facial lines: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from global clinical registration studies in 1678 participants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:961-970.

43. Beer K. Cost effectiveness of botulinum toxins for the treatment of depression: preliminary observations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):27-30.

44. Serna MC, Cruz I, Real J, et al. Duration and adherence of antidepressant treatment (2003-2007) based on prescription database. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(4):206-213.

45. Rechenberg JS, Hauptman AJ, Robertson HT, et al. Botulinum toxin for depression: Does patient appearance matter? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(1):171-173.

46. Magid M, Finzi E, Kruger THC, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(6):205-210.

47. Court, E. Allergan is still hopeful about using Botox to treat depression. April 8, 2017. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/allergan-is-still-hopeful-about-using-botox-to-treat-depression-2017-04-07. Accessed October 26, 2018.

48. Rudorfer MV. Botulinum toxin: does it have a place in the management of depression? CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):97-100.

49. Wollmer MA, Kalak N, Jung S, et al. Agitation predicts response of depression to botulinum toxin treatment in a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:36

50. Antonucci F, Rossi C, Gianfranceschi L, et al. Long-distance retrograde effects of botulinum neurotoxin A. J Neurosci. 2008;28(14):3689-3696.

Botulinum toxin, a potent neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, has been used as treatment for a variety of medical indications for more than 25 years (Box1-12). Recently, researchers have been exploring the role of botulinum toxin in psychiatry, primarily as an adjunctive treatment for depression, but also for several other possible indications. Several studies, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), have provided evidence that glabellar botulinum toxin injections may be a safe and effective treatment for depression. In this article, we provide an update on the latest clinical trials that evaluated botulinum toxin for depression, and also summarize the evidence regarding other potential clinical psychiatric applications of botulinum toxin.

Several RCTs suggest efficacy for depression

The use of botulinum toxin to treat depression is based on the facial feedback hypothesis, which was first proposed by Charles Darwin in 187213 and further elaborated by William James,14,15 who emphasized the importance of the sensation of bodily changes in emotion. Contrary to the popular belief that emotions trigger physiological changes in the body, James postulated that peripheral bodily changes secondary to stimuli perception would exert a sensory feedback, generating emotions. The manipulation of human facial expression with an expression that is associated with a particular emotion (eg, holding a pen with teeth, leading to risorius/zygomaticus muscles contraction and a smile simulation) was found to influence participants’ affective responses in the presence of emotional stimuli (eg, rating cartoons as funnier), reinforcing the facial-feedback hypothesis.16,17

From a neurobiologic standpoint, facial botulinum toxin A (BTA) injections in rats were associated with increased serotonin and norepinephrine concentrations in the hypothalamus and striatum, respectively.18 Moreover, amygdala activity in response to angry vs happy faces, measured via functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), was found to be attenuated after BTA applications to muscles involved in angry facial expressions.19,20 Both the neurotransmitters as well as the aforementioned brain regions have been implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.21,22

Compared with those in the placebo group, participants in the BTA group had a higher response rate as measured by the HAM-D17 at 6 weeks after treatment (P = .02), especially female patients (P = .002). Response to BTA, defined as ≥50% reduction on the HAM-D17, occurred within 2 weeks, and lasted another 6 weeks before slightly wearing off. Assessment of the CSS-GFL showed a statistically significant change at 6 weeks (P < .001). This small study failed, however, to show significant remission rates (HAM-D17 ≤7) in the BTA group compared with placebo.

Box

Botulinum toxin is a potent neurotoxin from Clostridium botulinum. Its potential for therapeutic use was first noticed in 1817 by physician Justinus Kerner, who coined the term botulism.1 In 1897, bacteriologist Emile van Ermengem isolated the causative bacterium C. botulinum.2 It was later discovered that the toxin induces muscle paralysis by inhibiting acetylcholine release from presynaptic motor neurons at the neuromuscular junction3 and was then mainly investigated as a treatment for medical conditions involving excessive or abnormal muscular contraction.

In 1989, the FDA approved botulinum toxin A (BTA) for the treatment of strabismus, blepharospasm, and other facial nerve disorders. In 2000, both BTA and botulinum toxin B (BTB) were FDA-approved for the treatment of cervical dystonia, and BTA was approved for the cosmetic treatment of frown lines (glabellar, canthal, and forehead lines).4 Other approved clinical indications for BTA include urinary incontinence due to detrusor overactivity associated with a neurologic condition such as spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis; prophylaxis of headaches in chronic migraine patients; treatment of both upper and lower limb spasticity; severe axillary hyperhidrosis inadequately managed by topical agents; and the reduction of the severity of abnormal head position and neck pain.5 Its anticholinergic effects have been also investigated for treatment of hyperhidrosis as well as sialorrhea caused by neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.6-8 Multiple studies have shown that botulinum toxin can alleviate spasms of the gastrointestinal tract, aiding patients with dysphagia and achalasia.9-11 There is also growing evidence supporting the use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of chronic pain, including non-migraine types of headaches such as tension headaches; myofascial syndrome; and neuropathic pain.12

Continue to: In a second RCT involving 74 patients with depression...

In a second RCT involving 74 patients with depression, Finzi and Rosenthal25 observed statistically significant response and remission rates in participants who received BTA injections, as measured by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). Participants were given either BTA or saline injections and assessed at 3 visits across 6 weeks using the MADRS, CGI, and Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). Photographs of participants’ facial expressions were assessed using frown scores to see whether changes in facial expression were associated with improvement of depression.

This study was able to reproduce on a larger scale the results observed by Wollmer et al.23 It found a statistically significant increase in the rate of remission (MADRS ≤10) at 6 weeks following BTA injections (27%, P < .02), and that even patients who were not resistant to antidepressants could benefit from BTA. However, although there was an observable trend in improvement of frown scores associated with improved depression scores, the correlation between these 2 variables was not statistically significant.

In a crossover RCT, Magid et al26 observed the response to BTA vs placebo saline injections in 30 patients with moderate to severe frown lines. The study lasted 24 weeks; participants switched treatments at Week 12. Mood improvement was assessed using the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-21), BDI, and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Compared with patients who received placebo injections, those treated with BTA injections showed statistically significant response rates, but not remission rates. This study demonstrated continued improvement throughout the 24 weeks in participants who initially received BTA injections, despite having received placebo for the last 12 weeks, by which time the cosmetic effects of the initial injection had worn off. This suggests that the antidepressant effects of botulinum toxin may not depend entirely on its paralytic effects, but also on its impact on the neurotransmitters involved in the pathophysiology of depression.18 By demonstrating improvement in the placebo group once they were started on botulinum toxin, this study also was able to exclude the possibility that other variables may be responsible for the difference in the clinical course between the 2 groups. However, this study was limited by a small sample size, and it only included participants who had moderate to severe frown lines at baseline.

Zamanian et al27 examined the therapeutic effects of BTA injections in 28 Iranian patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) diagnosed according to DSM-5 criteria. At 6 weeks, there were significant improvements in BDI scores in patients who received BTA vs those receiving placebo. However, these changes were demonstrated at 6 weeks (not as early as 2 weeks), and patients didn’t achieve remission.

A large-scale, multicenter U.S. phase II RCT investigated the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of a single administration of 2 different doses of BTA (30 units or 50 units) as monotherapy for the treatment of moderate to severe depression in 258 women.28 Effects on depression were measured at 3, 6, and 9 weeks using the MADRS. Participants who received the 30-unit injection showed statistically significant improvement at 3 weeks (

More recently, in a case series, Chugh et al30 examined the effect of BTA in 42 patients (55% men) with severe treatment-resistant depression. Participants were given BTA injections in the glabellar region as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants and observed for at least 6 weeks. Depression severity was measured using HAM-D17, MADRS, and BDI at baseline and at 3 weeks. Changes in glabellar frown lines also were assessed using the CSS-GFL. The authors reported statistically significant improvements in HAM-D17 (

A summary of the RCTs of BTA for treating depression appears in Table 1.23,25-28

Continue to: Benefits for other psychiatric indications

Benefits for other psychiatric indications

Borderline personality disorder. In a case series of 6 women, BTA injections in the glabellar region were reported to be particularly effective for the treatment of borderline personality disorder symptoms that were resistant to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.31 Two to 6 weeks after a 29-unit injection, borderline personality disorder symptoms as measured by the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder and/or the Borderline Symptom List were shown to significantly improve by 49% to 94% from baseline (P ≤ .05). These findings emphasize the promising therapeutic role of BTA on depressive symptoms concomitant with the emotional lability, impulsivity, and negative emotions that usually characterize this personality disorder.31,32 A small sample size and lack of a placebo comparator are limitations of this research.

Neuroleptic-induced sialorrhea. Botulinum toxin injections in the salivary glands have been investigated for treating clozapine-induced sialorrhea because they are thought to directly inhibit the release of acetylcholine from salivary glands. One small RCT that used botulinum toxin B (BTB)33 and 1 case report that used BTA34 reported successful reduction in hypersalivation, with doses ranging from 150 to 500 units injected in each of the parotid and/or submandibular glands bilaterally. Although the treatment was well tolerated and lasted up to 16 weeks, larger studies are needed to replicate these findings.33-35

Orofacial tardive dyskinesia. Several case reports of orofacial tardive dyskinesia, including lingual dyskinesia and lingual protrusion dystonia, have found improvements in hyperkinetic movements following muscular BTA injections, such as in the genioglossus muscle in the case of tongue involvement.36-39 These cases were, however, described in the literature before the recent FDA approval of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 inhibitors valbenazine and deutetrabenazine for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia.40,41

Studies examining botulinum toxin’s application in areas of psychiatry other than depression are summarized in Table 2.31,33,36-38

Continue to: Promising initial findings but multiple limitations

Promising initial findings but multiple limitations

Although BTA injections have been explored as a potential treatment for several psychiatric conditions, the bulk of recent evidence is derived from studies in patients with depressive disorders. BTA injections in the glabellar regions have been shown in small RCTs to be well-tolerated with overall promising improvement of depressive symptoms, optimally 6 weeks after a single injection. Moreover, BTA has been shown to be safe and long-lasting, which would be convenient for patients and might improve adherence to therapy.42-44 BTA’s antidepressant effects were shown to be independent of frown line severity or patient satisfaction with cosmetic effects.45 The trials by Wollmer et al,23 Finzi and Rosenthal,25 and Magid et al26 mainly studied BTA as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants in patients with ongoing unipolar depression. However, Finzi and Rosenthal25 included patients who were not medicated at the time of the study.

Pooled analysis of these 3 RCTs found that patients who received BTA monotherapy improved equally to those who received it as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants. Overall, on primary endpoint measures, a response rate of 54.2% was obtained in the BTA group compared with 10.7% among patients who received placebo saline injections (odds ratio [OR] 11.1, 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.3 to 28.8, number needed to treat [NNT] = 2.3) and a remission rate of 30.5% with BTA compared with 6.7% with placebo (OR 7.3, 95 % CI, 2.4 to 22.5, NNT = 4.2).46 However, remission rates tend to be higher in the augmentation groups, and so further studies are needed to compare both treatment strategies.

Nevertheless, these positive findings have been recently challenged by the results of the largest U.S. multicenter phase II RCT,28 which failed to find a significant antidepressant effect at 6 weeks with the 30-unit BTA injection, and also failed to prove a dose-effect relationship, as the 50-unit injection wasn’t superior to the lower dose and didn’t significantly differ from placebo. One hypothesis to explain this discrepancy may be the difference in injection sites between the treatment and placebo groups.47 Future studies need to address the various limitations of earlier clinical trials that mainly yielded promising results with BTA.

A major concern is the high rate of unblinding of participants and researchers in BTA trials, as the cosmetic effects of botulinum toxin injections make them easy to distinguish from saline injections. Ninety percent of participants in the Wollmer et al study23 were able to correctly guess their group allocation, while 60% of evaluators guessed correctly. Finzi and Rozenthal25 reported 52% of participants in the BTA group, 46% in the placebo group, and 73% of evaluators correctly guessed their allocation. Magid et al26 reported 75% of participants were able to guess the order of intervention they received. The high unblinding rates in these trials remains a significant limitation. There is a concern that this may lead to an underestimation of the placebo effect relative to clinical improvement, thus causing inflation of outcome differences between groups. Although various methods have been tried to minimize evaluator unblinding, such as placing surgical caps on participants’ faces during visits to hide the glabellar region, better methods need to be implemented to prevent unblinding of both raters and participants.

Furthermore, except for the multicenter phase II trial, most studies have been conducted in small samples, which limits their statistical power. Larger controlled trials will be needed to replicate the positive findings obtained in smaller RCTs.

Another limitation is that the majority of the well-designed RCTs were conducted in populations that were predominantly female, which makes it difficult to reliably assess treatment efficacy in men. This may be because cosmetic treatment with botulinum toxin injection is more favorably received by women than by men. A recent comparison48 of the studies by Wollmer et al23 and Finzi and Rosenthal25 discussed an interesting observation. Wollmer et al did not explicitly mention botulinum toxin when recruiting for the study, while Finzi and Rosenthal did. While approximately a quarter of the participants in the Wollmer et al study were male, Finzi and Rosenthal attracted an almost entirely female population. Perhaps there is a potential bias for females to be more attracted to these studies due to the secondary gain of receiving a cosmetic procedure.

In an attempt to understand predictors of positive response to botulinum toxin in patients with depression, Wollmer et al49 conducted a follow-up study in which they reassessed the data obtained from their initial RCT using the HAM-D agitation item scores to separate the 15 participants who received BTA into low-agitation (≤1 score on agitation item of the HAM-D scale) and high-agitation (≥2 score on agitation item of the HAM-D scale) groups. They found that the 9 participants who responded to BTA treatment had significantly higher baseline agitation scores than participants who did not respond (1.56 ± 0.88 vs 0.33 ± 0.52, P = .01). All of the participants who presented with higher agitation levels experienced response, compared with 40% of those with lower agitation levels (P = .04), although there was no significant difference in magnitude of improvement (14.2 ± 1.92 vs 8.0 ± 9.37, P = .07). The study added additional support to the facial feedback hypothesis, as it links the improvement of depression to facial muscle activation targeted by the injections. It also introduced a potential predictor of response to botulinum toxin treatment, highlighting potential factors to consider when enrolling patients in future investigations.

The case series of patients with borderline personality disorder31 also shed light on the potential positive effect of BTA treatment for a particular subtype of patients with depression—those with comorbid emotional instability—to consider as a therapeutic target for the future. Hence, inclusion criteria for future trials might potentially include patient age, gender, existence/quantification of prominent frown lines at baseline, severity of MDD, duration of depression, and personality characteristics of enrolled participants.

In conclusion, BTA injections appear promising as a treatment for depression as well as for other psychiatric disorders. Future studies should focus on identifying optimal candidates for this innovative treatment modality. Furthermore, BTA dosing and administration strategies (monotherapy vs adjunctive treatment to antidepressants) need to be further explored. As retrograde axonal transport of botulinum toxin has been demonstrated in animal studies, it would be interesting to further examine its effects in the human CNS to enhance our knowledge of the pathophysiology of botulinum and its potential applications in psychiatry.50

Bottom Line

Botulinum toxin shows promising antidepressant effects and may have a role in the treatment of several other psychiatric disorders. More research is needed to address limitations of previous studies and to establish an adequate treatment regimen.

Related Resources

- Wollmer MA, Magid M, Kruger TH. Botulinum toxin treatment in depression. In: Bewley A, Taylor RE, Reichenberg JS, et al (eds). Practical psychodermatology. Oxford, UK: Wiley; 2014.

- Wollmer MA, Neumann I, Magid M. et al. Shrink that frown! Botulinum toxin therapy is lifting the face of psychiatry. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153(4):540-548.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Biperiden • Akineton

Botulinum toxin A • Botox

Botulinum toxin B • Myobloc

Clozapine • Clozaril

Deutetrabenazine • Austedo

Flupentixol • Prolixin

Imipramine • Tofranil

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Reserpine • Serpalan, Serpasil

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Valbenazine • Ingrezza

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Botulinum toxin, a potent neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, has been used as treatment for a variety of medical indications for more than 25 years (Box1-12). Recently, researchers have been exploring the role of botulinum toxin in psychiatry, primarily as an adjunctive treatment for depression, but also for several other possible indications. Several studies, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), have provided evidence that glabellar botulinum toxin injections may be a safe and effective treatment for depression. In this article, we provide an update on the latest clinical trials that evaluated botulinum toxin for depression, and also summarize the evidence regarding other potential clinical psychiatric applications of botulinum toxin.

Several RCTs suggest efficacy for depression

The use of botulinum toxin to treat depression is based on the facial feedback hypothesis, which was first proposed by Charles Darwin in 187213 and further elaborated by William James,14,15 who emphasized the importance of the sensation of bodily changes in emotion. Contrary to the popular belief that emotions trigger physiological changes in the body, James postulated that peripheral bodily changes secondary to stimuli perception would exert a sensory feedback, generating emotions. The manipulation of human facial expression with an expression that is associated with a particular emotion (eg, holding a pen with teeth, leading to risorius/zygomaticus muscles contraction and a smile simulation) was found to influence participants’ affective responses in the presence of emotional stimuli (eg, rating cartoons as funnier), reinforcing the facial-feedback hypothesis.16,17

From a neurobiologic standpoint, facial botulinum toxin A (BTA) injections in rats were associated with increased serotonin and norepinephrine concentrations in the hypothalamus and striatum, respectively.18 Moreover, amygdala activity in response to angry vs happy faces, measured via functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), was found to be attenuated after BTA applications to muscles involved in angry facial expressions.19,20 Both the neurotransmitters as well as the aforementioned brain regions have been implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.21,22

Compared with those in the placebo group, participants in the BTA group had a higher response rate as measured by the HAM-D17 at 6 weeks after treatment (P = .02), especially female patients (P = .002). Response to BTA, defined as ≥50% reduction on the HAM-D17, occurred within 2 weeks, and lasted another 6 weeks before slightly wearing off. Assessment of the CSS-GFL showed a statistically significant change at 6 weeks (P < .001). This small study failed, however, to show significant remission rates (HAM-D17 ≤7) in the BTA group compared with placebo.

Box

Botulinum toxin is a potent neurotoxin from Clostridium botulinum. Its potential for therapeutic use was first noticed in 1817 by physician Justinus Kerner, who coined the term botulism.1 In 1897, bacteriologist Emile van Ermengem isolated the causative bacterium C. botulinum.2 It was later discovered that the toxin induces muscle paralysis by inhibiting acetylcholine release from presynaptic motor neurons at the neuromuscular junction3 and was then mainly investigated as a treatment for medical conditions involving excessive or abnormal muscular contraction.

In 1989, the FDA approved botulinum toxin A (BTA) for the treatment of strabismus, blepharospasm, and other facial nerve disorders. In 2000, both BTA and botulinum toxin B (BTB) were FDA-approved for the treatment of cervical dystonia, and BTA was approved for the cosmetic treatment of frown lines (glabellar, canthal, and forehead lines).4 Other approved clinical indications for BTA include urinary incontinence due to detrusor overactivity associated with a neurologic condition such as spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis; prophylaxis of headaches in chronic migraine patients; treatment of both upper and lower limb spasticity; severe axillary hyperhidrosis inadequately managed by topical agents; and the reduction of the severity of abnormal head position and neck pain.5 Its anticholinergic effects have been also investigated for treatment of hyperhidrosis as well as sialorrhea caused by neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.6-8 Multiple studies have shown that botulinum toxin can alleviate spasms of the gastrointestinal tract, aiding patients with dysphagia and achalasia.9-11 There is also growing evidence supporting the use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of chronic pain, including non-migraine types of headaches such as tension headaches; myofascial syndrome; and neuropathic pain.12

Continue to: In a second RCT involving 74 patients with depression...

In a second RCT involving 74 patients with depression, Finzi and Rosenthal25 observed statistically significant response and remission rates in participants who received BTA injections, as measured by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). Participants were given either BTA or saline injections and assessed at 3 visits across 6 weeks using the MADRS, CGI, and Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). Photographs of participants’ facial expressions were assessed using frown scores to see whether changes in facial expression were associated with improvement of depression.

This study was able to reproduce on a larger scale the results observed by Wollmer et al.23 It found a statistically significant increase in the rate of remission (MADRS ≤10) at 6 weeks following BTA injections (27%, P < .02), and that even patients who were not resistant to antidepressants could benefit from BTA. However, although there was an observable trend in improvement of frown scores associated with improved depression scores, the correlation between these 2 variables was not statistically significant.

In a crossover RCT, Magid et al26 observed the response to BTA vs placebo saline injections in 30 patients with moderate to severe frown lines. The study lasted 24 weeks; participants switched treatments at Week 12. Mood improvement was assessed using the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-21), BDI, and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Compared with patients who received placebo injections, those treated with BTA injections showed statistically significant response rates, but not remission rates. This study demonstrated continued improvement throughout the 24 weeks in participants who initially received BTA injections, despite having received placebo for the last 12 weeks, by which time the cosmetic effects of the initial injection had worn off. This suggests that the antidepressant effects of botulinum toxin may not depend entirely on its paralytic effects, but also on its impact on the neurotransmitters involved in the pathophysiology of depression.18 By demonstrating improvement in the placebo group once they were started on botulinum toxin, this study also was able to exclude the possibility that other variables may be responsible for the difference in the clinical course between the 2 groups. However, this study was limited by a small sample size, and it only included participants who had moderate to severe frown lines at baseline.

Zamanian et al27 examined the therapeutic effects of BTA injections in 28 Iranian patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) diagnosed according to DSM-5 criteria. At 6 weeks, there were significant improvements in BDI scores in patients who received BTA vs those receiving placebo. However, these changes were demonstrated at 6 weeks (not as early as 2 weeks), and patients didn’t achieve remission.

A large-scale, multicenter U.S. phase II RCT investigated the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of a single administration of 2 different doses of BTA (30 units or 50 units) as monotherapy for the treatment of moderate to severe depression in 258 women.28 Effects on depression were measured at 3, 6, and 9 weeks using the MADRS. Participants who received the 30-unit injection showed statistically significant improvement at 3 weeks (

More recently, in a case series, Chugh et al30 examined the effect of BTA in 42 patients (55% men) with severe treatment-resistant depression. Participants were given BTA injections in the glabellar region as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants and observed for at least 6 weeks. Depression severity was measured using HAM-D17, MADRS, and BDI at baseline and at 3 weeks. Changes in glabellar frown lines also were assessed using the CSS-GFL. The authors reported statistically significant improvements in HAM-D17 (

A summary of the RCTs of BTA for treating depression appears in Table 1.23,25-28

Continue to: Benefits for other psychiatric indications

Benefits for other psychiatric indications

Borderline personality disorder. In a case series of 6 women, BTA injections in the glabellar region were reported to be particularly effective for the treatment of borderline personality disorder symptoms that were resistant to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy.31 Two to 6 weeks after a 29-unit injection, borderline personality disorder symptoms as measured by the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder and/or the Borderline Symptom List were shown to significantly improve by 49% to 94% from baseline (P ≤ .05). These findings emphasize the promising therapeutic role of BTA on depressive symptoms concomitant with the emotional lability, impulsivity, and negative emotions that usually characterize this personality disorder.31,32 A small sample size and lack of a placebo comparator are limitations of this research.

Neuroleptic-induced sialorrhea. Botulinum toxin injections in the salivary glands have been investigated for treating clozapine-induced sialorrhea because they are thought to directly inhibit the release of acetylcholine from salivary glands. One small RCT that used botulinum toxin B (BTB)33 and 1 case report that used BTA34 reported successful reduction in hypersalivation, with doses ranging from 150 to 500 units injected in each of the parotid and/or submandibular glands bilaterally. Although the treatment was well tolerated and lasted up to 16 weeks, larger studies are needed to replicate these findings.33-35

Orofacial tardive dyskinesia. Several case reports of orofacial tardive dyskinesia, including lingual dyskinesia and lingual protrusion dystonia, have found improvements in hyperkinetic movements following muscular BTA injections, such as in the genioglossus muscle in the case of tongue involvement.36-39 These cases were, however, described in the literature before the recent FDA approval of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 inhibitors valbenazine and deutetrabenazine for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia.40,41

Studies examining botulinum toxin’s application in areas of psychiatry other than depression are summarized in Table 2.31,33,36-38

Continue to: Promising initial findings but multiple limitations

Promising initial findings but multiple limitations

Although BTA injections have been explored as a potential treatment for several psychiatric conditions, the bulk of recent evidence is derived from studies in patients with depressive disorders. BTA injections in the glabellar regions have been shown in small RCTs to be well-tolerated with overall promising improvement of depressive symptoms, optimally 6 weeks after a single injection. Moreover, BTA has been shown to be safe and long-lasting, which would be convenient for patients and might improve adherence to therapy.42-44 BTA’s antidepressant effects were shown to be independent of frown line severity or patient satisfaction with cosmetic effects.45 The trials by Wollmer et al,23 Finzi and Rosenthal,25 and Magid et al26 mainly studied BTA as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants in patients with ongoing unipolar depression. However, Finzi and Rosenthal25 included patients who were not medicated at the time of the study.

Pooled analysis of these 3 RCTs found that patients who received BTA monotherapy improved equally to those who received it as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants. Overall, on primary endpoint measures, a response rate of 54.2% was obtained in the BTA group compared with 10.7% among patients who received placebo saline injections (odds ratio [OR] 11.1, 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.3 to 28.8, number needed to treat [NNT] = 2.3) and a remission rate of 30.5% with BTA compared with 6.7% with placebo (OR 7.3, 95 % CI, 2.4 to 22.5, NNT = 4.2).46 However, remission rates tend to be higher in the augmentation groups, and so further studies are needed to compare both treatment strategies.

Nevertheless, these positive findings have been recently challenged by the results of the largest U.S. multicenter phase II RCT,28 which failed to find a significant antidepressant effect at 6 weeks with the 30-unit BTA injection, and also failed to prove a dose-effect relationship, as the 50-unit injection wasn’t superior to the lower dose and didn’t significantly differ from placebo. One hypothesis to explain this discrepancy may be the difference in injection sites between the treatment and placebo groups.47 Future studies need to address the various limitations of earlier clinical trials that mainly yielded promising results with BTA.

A major concern is the high rate of unblinding of participants and researchers in BTA trials, as the cosmetic effects of botulinum toxin injections make them easy to distinguish from saline injections. Ninety percent of participants in the Wollmer et al study23 were able to correctly guess their group allocation, while 60% of evaluators guessed correctly. Finzi and Rozenthal25 reported 52% of participants in the BTA group, 46% in the placebo group, and 73% of evaluators correctly guessed their allocation. Magid et al26 reported 75% of participants were able to guess the order of intervention they received. The high unblinding rates in these trials remains a significant limitation. There is a concern that this may lead to an underestimation of the placebo effect relative to clinical improvement, thus causing inflation of outcome differences between groups. Although various methods have been tried to minimize evaluator unblinding, such as placing surgical caps on participants’ faces during visits to hide the glabellar region, better methods need to be implemented to prevent unblinding of both raters and participants.

Furthermore, except for the multicenter phase II trial, most studies have been conducted in small samples, which limits their statistical power. Larger controlled trials will be needed to replicate the positive findings obtained in smaller RCTs.

Another limitation is that the majority of the well-designed RCTs were conducted in populations that were predominantly female, which makes it difficult to reliably assess treatment efficacy in men. This may be because cosmetic treatment with botulinum toxin injection is more favorably received by women than by men. A recent comparison48 of the studies by Wollmer et al23 and Finzi and Rosenthal25 discussed an interesting observation. Wollmer et al did not explicitly mention botulinum toxin when recruiting for the study, while Finzi and Rosenthal did. While approximately a quarter of the participants in the Wollmer et al study were male, Finzi and Rosenthal attracted an almost entirely female population. Perhaps there is a potential bias for females to be more attracted to these studies due to the secondary gain of receiving a cosmetic procedure.

In an attempt to understand predictors of positive response to botulinum toxin in patients with depression, Wollmer et al49 conducted a follow-up study in which they reassessed the data obtained from their initial RCT using the HAM-D agitation item scores to separate the 15 participants who received BTA into low-agitation (≤1 score on agitation item of the HAM-D scale) and high-agitation (≥2 score on agitation item of the HAM-D scale) groups. They found that the 9 participants who responded to BTA treatment had significantly higher baseline agitation scores than participants who did not respond (1.56 ± 0.88 vs 0.33 ± 0.52, P = .01). All of the participants who presented with higher agitation levels experienced response, compared with 40% of those with lower agitation levels (P = .04), although there was no significant difference in magnitude of improvement (14.2 ± 1.92 vs 8.0 ± 9.37, P = .07). The study added additional support to the facial feedback hypothesis, as it links the improvement of depression to facial muscle activation targeted by the injections. It also introduced a potential predictor of response to botulinum toxin treatment, highlighting potential factors to consider when enrolling patients in future investigations.

The case series of patients with borderline personality disorder31 also shed light on the potential positive effect of BTA treatment for a particular subtype of patients with depression—those with comorbid emotional instability—to consider as a therapeutic target for the future. Hence, inclusion criteria for future trials might potentially include patient age, gender, existence/quantification of prominent frown lines at baseline, severity of MDD, duration of depression, and personality characteristics of enrolled participants.

In conclusion, BTA injections appear promising as a treatment for depression as well as for other psychiatric disorders. Future studies should focus on identifying optimal candidates for this innovative treatment modality. Furthermore, BTA dosing and administration strategies (monotherapy vs adjunctive treatment to antidepressants) need to be further explored. As retrograde axonal transport of botulinum toxin has been demonstrated in animal studies, it would be interesting to further examine its effects in the human CNS to enhance our knowledge of the pathophysiology of botulinum and its potential applications in psychiatry.50

Bottom Line

Botulinum toxin shows promising antidepressant effects and may have a role in the treatment of several other psychiatric disorders. More research is needed to address limitations of previous studies and to establish an adequate treatment regimen.

Related Resources

- Wollmer MA, Magid M, Kruger TH. Botulinum toxin treatment in depression. In: Bewley A, Taylor RE, Reichenberg JS, et al (eds). Practical psychodermatology. Oxford, UK: Wiley; 2014.

- Wollmer MA, Neumann I, Magid M. et al. Shrink that frown! Botulinum toxin therapy is lifting the face of psychiatry. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153(4):540-548.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Biperiden • Akineton

Botulinum toxin A • Botox

Botulinum toxin B • Myobloc

Clozapine • Clozaril

Deutetrabenazine • Austedo

Flupentixol • Prolixin

Imipramine • Tofranil

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Reserpine • Serpalan, Serpasil

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Valbenazine • Ingrezza

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Erbguth FJ, Naumann M. Historical aspects of botulinum toxin. Justinus Kerner (1786-1862) and the “sausage” poison. Neurology. 1999;53(8):1850-1853.

2. Devriese PP. On the discovery of Clostridium botulinum. J History Neurosci. 1999;8(1):43-50.

3. Burgen ASV, Dickens F, Zatman LJ. The action of botulinum toxin on the neuro-muscular junction. J Physiol. 1949;109(1-2):10-24.

4. Jankovic J. Botulinum toxin in clinical practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(7):951-957.

5. BOTOX (OnabotulinumtoxinA) [package insert]. Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA; 2015.

6. Saadia D, Voustianiouk A, Wang AK, et al. Botulinum toxin type A in primary palmar hyperhidrosis. Randomized, single-blind, two-dose study. Neurology. 2001;57(11):2095-2099.

7. Naumann MK, Lowe NJ. Effect of botulinum toxin type A on quality of life measures in patients with excessive axillary sweating: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(6):1218-1226.

8. Giess R, Naumann M, Werner E, et al. Injections of botulinum toxin A into the salivary glands improve sialorrhea in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69(1):121-123.

9. Restivo DA, Palmeri A, Marchese-Ragona R. Botulinum toxin for cricopharyngeal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1174-1175.

10. Pasricha PJ, Ravich WJ, Hendrix T, et al. Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia. N Engl J Med. 1995(12);322:774-778.

11. Schiano TD, Parkman HP, Miller LS, et al. Use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of achalasia. Dig Dis. 1998;16(1):14-22.

12. Sim WS. Application of botulinum toxin in pain management. Korean J Pain. 2011;24(1):1-6.

13. Darwin C. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London, UK: John Murray; 1872:366.

14. James W. The principles of psychology, vol. 2. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company; 1890.

15. James W. II. —What is an emotion? Mind. 1884;os-IX(34):188-205.

16. Strack R, Martin LL, Stepper S. Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of facial expressions: a nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(5):768-777.

17. Larsen RJ, Kasimatis M, Frey K. Facilitating the furrowed brow: an unobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis applied to unpleasant affect. Cogn Emot. 1992;6(5):321-338.

18. Ibragic S, Matak I, Dracic A, et al. Effects of botulinum toxin type A facial injection on monoamines and their metabolites in sensory, limbic, and motor brain regions in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2016;617:213-217.

19. Hennenlotter A, Dresel C, Castrop F, et al. The link between facial feedback and neural activity within central circuitries of emotion—new insights from botulinum toxin-induced denervation of frown muscles. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(3):537-42

20. Kim MJ, Neta M, Davis FC, et al. Botulinum toxin-induced facial muscle paralysis affects amygdala responses to the perception emotional expressions: preliminary findings from an A-B-A design. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2014;4:11.

21. Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, et al. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002;34(1):13-25.

22. Pandya M, Altinay M, Malone DA Jr, et al. Where in the brain is depression? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(6):634-642.

23. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:574-581.

24. BOTOX Cosmetic [prescribing information]. Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA; 2017.

25. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA; a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

26. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. The treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24 week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

27. Zamanian A, Ghanbari Jolfaei A, Mehran G, et al. Efficacy of botox versus placebo for treatment of patients with major depression. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(7):982-984.

28. Allergan. OnabotulinumtoxinA as treatment for major depressive disorder in adult females. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02116361. Accessed October 26, 2018.

29. Allergan. Allergan reports topline phase II data supporting advancement of BOTOX® (onabotulinumtoxinA) for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). April 5, 2017. https://www.allergan.com/news/news/thomson-reuters/allergan-reports-topline-phase-ii-data-supporting. Accessed October 26, 2018.

30. Chugh S, Chhabria A, Jung S, et al. Botulinum toxin as a treatment for depression in a real-world setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(1):15-20.

31. Kruger TH, Magid M, Wollmer MA. Can botulinum toxin help patients with borderline personality disorder? Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(9):940-941.

32. Baumeister JC, Papa G, Foroni F. Deeper than skin deep – the effect of botulinum toxin-A on emotion processing. Toxicon. 2016;119:86-90.

33. Steinlechner S, Klein C, Moser A, et al. Botulinum toxin B as an effective and safe treatment for neuroleptic-induced sialorrhea. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010;207(4):593-597.

34. Kahl KG, Hagenah J, Zapf S, et al. Botulinum toxin as an effective treatment of clozapine-induced hypersalivation. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;173(1-2):229-230.

35. Bird AM, Smith TL, Walton AE. Current treatment strategies for clozapine-induced sialorrhea. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(5):667-675.

36. Tschopp L, Salazar Z, Micheli F. Botulinum toxin in painful tardive dyskinesia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(3):165-166.

37. Hennings JM, Krause E, Bötzel K, et al. Successful treatment of tardive lingual dystonia with botulinum toxin: case report and review of the literature. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(5):1167-1171.

38. Slotema CW, van Harten PN, Bruggeman R, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of orofacial tardive dyskinesia: a single blind study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(2):507-509.

39. Esper CD, Freeman A, Factor SA. Lingual protrusion dystonia: frequency, etiology and botulinum toxin therapy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(7):438-441.

40. Seeberger LC, Hauser RA. Valbenazine for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(12):1279-1287.

41. Citrome L. Deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved novel medication—What is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71(11):e13030.

42. Brin MF, Boodhoo TI, Pogoda JM, et al. Safety and tolerability of onabotulinumtoxinA in the tretment of facial lines: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from global clinical registration studies in 1678 participants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:961-970.

43. Beer K. Cost effectiveness of botulinum toxins for the treatment of depression: preliminary observations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):27-30.

44. Serna MC, Cruz I, Real J, et al. Duration and adherence of antidepressant treatment (2003-2007) based on prescription database. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(4):206-213.

45. Rechenberg JS, Hauptman AJ, Robertson HT, et al. Botulinum toxin for depression: Does patient appearance matter? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(1):171-173.

46. Magid M, Finzi E, Kruger THC, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(6):205-210.

47. Court, E. Allergan is still hopeful about using Botox to treat depression. April 8, 2017. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/allergan-is-still-hopeful-about-using-botox-to-treat-depression-2017-04-07. Accessed October 26, 2018.

48. Rudorfer MV. Botulinum toxin: does it have a place in the management of depression? CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):97-100.

49. Wollmer MA, Kalak N, Jung S, et al. Agitation predicts response of depression to botulinum toxin treatment in a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:36

50. Antonucci F, Rossi C, Gianfranceschi L, et al. Long-distance retrograde effects of botulinum neurotoxin A. J Neurosci. 2008;28(14):3689-3696.

1. Erbguth FJ, Naumann M. Historical aspects of botulinum toxin. Justinus Kerner (1786-1862) and the “sausage” poison. Neurology. 1999;53(8):1850-1853.

2. Devriese PP. On the discovery of Clostridium botulinum. J History Neurosci. 1999;8(1):43-50.

3. Burgen ASV, Dickens F, Zatman LJ. The action of botulinum toxin on the neuro-muscular junction. J Physiol. 1949;109(1-2):10-24.

4. Jankovic J. Botulinum toxin in clinical practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(7):951-957.

5. BOTOX (OnabotulinumtoxinA) [package insert]. Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA; 2015.

6. Saadia D, Voustianiouk A, Wang AK, et al. Botulinum toxin type A in primary palmar hyperhidrosis. Randomized, single-blind, two-dose study. Neurology. 2001;57(11):2095-2099.

7. Naumann MK, Lowe NJ. Effect of botulinum toxin type A on quality of life measures in patients with excessive axillary sweating: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(6):1218-1226.

8. Giess R, Naumann M, Werner E, et al. Injections of botulinum toxin A into the salivary glands improve sialorrhea in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69(1):121-123.

9. Restivo DA, Palmeri A, Marchese-Ragona R. Botulinum toxin for cricopharyngeal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1174-1175.

10. Pasricha PJ, Ravich WJ, Hendrix T, et al. Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia. N Engl J Med. 1995(12);322:774-778.

11. Schiano TD, Parkman HP, Miller LS, et al. Use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of achalasia. Dig Dis. 1998;16(1):14-22.

12. Sim WS. Application of botulinum toxin in pain management. Korean J Pain. 2011;24(1):1-6.

13. Darwin C. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London, UK: John Murray; 1872:366.

14. James W. The principles of psychology, vol. 2. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company; 1890.

15. James W. II. —What is an emotion? Mind. 1884;os-IX(34):188-205.

16. Strack R, Martin LL, Stepper S. Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of facial expressions: a nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(5):768-777.

17. Larsen RJ, Kasimatis M, Frey K. Facilitating the furrowed brow: an unobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis applied to unpleasant affect. Cogn Emot. 1992;6(5):321-338.

18. Ibragic S, Matak I, Dracic A, et al. Effects of botulinum toxin type A facial injection on monoamines and their metabolites in sensory, limbic, and motor brain regions in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2016;617:213-217.

19. Hennenlotter A, Dresel C, Castrop F, et al. The link between facial feedback and neural activity within central circuitries of emotion—new insights from botulinum toxin-induced denervation of frown muscles. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(3):537-42

20. Kim MJ, Neta M, Davis FC, et al. Botulinum toxin-induced facial muscle paralysis affects amygdala responses to the perception emotional expressions: preliminary findings from an A-B-A design. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2014;4:11.

21. Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, et al. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002;34(1):13-25.

22. Pandya M, Altinay M, Malone DA Jr, et al. Where in the brain is depression? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(6):634-642.

23. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:574-581.

24. BOTOX Cosmetic [prescribing information]. Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA; 2017.

25. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA; a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

26. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. The treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24 week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

27. Zamanian A, Ghanbari Jolfaei A, Mehran G, et al. Efficacy of botox versus placebo for treatment of patients with major depression. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(7):982-984.

28. Allergan. OnabotulinumtoxinA as treatment for major depressive disorder in adult females. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02116361. Accessed October 26, 2018.

29. Allergan. Allergan reports topline phase II data supporting advancement of BOTOX® (onabotulinumtoxinA) for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). April 5, 2017. https://www.allergan.com/news/news/thomson-reuters/allergan-reports-topline-phase-ii-data-supporting. Accessed October 26, 2018.

30. Chugh S, Chhabria A, Jung S, et al. Botulinum toxin as a treatment for depression in a real-world setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(1):15-20.

31. Kruger TH, Magid M, Wollmer MA. Can botulinum toxin help patients with borderline personality disorder? Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(9):940-941.

32. Baumeister JC, Papa G, Foroni F. Deeper than skin deep – the effect of botulinum toxin-A on emotion processing. Toxicon. 2016;119:86-90.

33. Steinlechner S, Klein C, Moser A, et al. Botulinum toxin B as an effective and safe treatment for neuroleptic-induced sialorrhea. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010;207(4):593-597.