User login

› Perform a hearing test when otitis media with effusion is present for 3 months or longer, or whenever you suspect a language delay, learning problems, or a significant hearing loss. C

› Use the results of the hearing test to guide management decisions. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › A mother brings in her 3-year-old son for a regular check-up. Her only concern is that for the past 2 weeks, he has not been sleeping through the night. She indicates that the sleeping problem began after he was diagnosed with and treated for an ear infection. Fortunately, this hasn’t affected his daily activity or energy, she says.

The child’s appetite is good and he speaks clearly, in 5-word sentences. He is meeting his developmental milestones, and appears well—sitting in his mother’s lap and playing with her smartphone. His head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat exam only turns up fluid behind his left tympanic membrane, which is not red or bulging. The right membrane appears normal, and he has no cervical lymphadenopathy. The rest of his exam is normal. How would you manage a patient like this?

"Glue ear" is often asymptomatic

Otitis media with effusion (OME) is defined as middle-ear effusion (MEE) in the absence of acute signs of infection. In children, OME—also referred to as “glue ear”—most often arises after acute otitis media (AOM). In adults, it often occurs in association with eustachian tube dysfunction, although OME is a separate diagnosis. (To learn more, see “What about OME in adults?”1,2.)

Experts have found it difficult to determine the exact incidence of OME because it is often asymptomatic. In addition, many cases quickly resolve on their own, making it challenging to diagnose. A 2-year prospective study of 2- to 6-year-old preschoolers revealed that MEE, diagnosed via monthly otoscopy and tympanometry, occurred at least once in 53% of the children in the first year and in 61% of the children in the second year.3 A second study followed 7-year-olds monthly for one year and found a 31% incidence of MEE using tympanometry.4 In the 25% of children found to have persistent MEE, the researchers noted spontaneous recovery after an average of 2 months.

We believe that nearly all children have experienced one episode of OME by the age of 3 years, but the prevalence of OME varies with age and the time of year. It is more prevalent in the winter than the summer months.5 OME is more common in Caucasian children than in African American or Asian children.6

Etiology remains elusive

Risk factors for children include a family history of OME, bottle-feeding, day care attendance, exposure to tobacco smoke, and a personal history of allergies.7,8 One study conducted on mice suggested that inherited structural abnormalities of the middle ear and eustachian tube may play a role as well.9 Some have suggested that effusions of OME in children result from chronic inflammation, for example, after AOM, and that the effusions are sterile; however, recent studies have demonstrated that a biofilm is formed by bacterial otopathogens in the effusion.10-12 The common pathogens found include nontypeable Haemophilus influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Inflammatory exudate or neutrophil infiltration is rare in the fluid, however.

The contribution of allergies to OME in children remains somewhat controversial. A retrospective review from the United Kingdom of 209 children with OME found a history of allergic rhinitis, asthma, and eczema in 89%, 36%, and 24%, respectively.13 However, this study was done at an allergy clinic, and it is possible that the data from the clinic’s specialized patient population are not generalizable. Gastroesophageal reflux may also be associated with OME in children. However, studies measuring the concentration of pepsin and pepsinogen in middle-ear fluid have provided conflicting results.14,15

Look for these signs and symptoms

OME is often asymptomatic. If a patient has clinical signs of an acute illness, including fever and an erythematous tympanic membrane, it’s important to evaluate for another cause. OME can present with hearing loss or a sense of fullness in the ear. While an infant cannot express the hearing loss, the parent may detect it when observing and interacting mwith the child. Parents are also likely to report that the child is experiencing sleep disturbances.16

Vertigo may occur with OME, although not often. It may manifest itself if the child stumbles or falls. An older child or adult with vertigo may say that it feels like the room is spinning.

Diagnosis relies on pneumatic otoscopy

On physical exam, the patient will likely appear well. Otoscopic examination reveals fluid behind a normal or retracted tympanic membrane; the fluid is often clear or yellowish in color.

A subcommittee comprised of members of the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS) published a clinical practice guideline in 2004 that delineates the current diagnosis and management of children between 2 months and 12 years of age with OME.17

Pneumatic otoscopy, which can reveal decreased or absent movement of the tympanic membrane (the result of fluid behind the membrane), is the primary diagnostic method recommended by the guideline. Tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry may also be used to make the diagnosis, especially when the presence of MEE is difficult to determine using pneumatic otoscopy.

CASE › Upon further discussion with the patient’s mother, you learn that the boy goes to day care 3 days a week and stays with his grandmother 2 days a week. His grandmother smokes outside of the home when he is staying with her.

After reviewing these risk factors with the mother (including the importance of smoking cessation for the grandmother), the mother asks if he needs antibiotics or a referral to a specialist for treating his OME.

How best to approach treatment

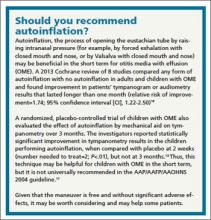

There are several management options to choose from, including watchful waiting, medication, and/or surgery. (Another option, autoinflation, which has shown some short-term benefits, is described in “Should you recommend autoinflation?”17-19.)

The goals of management are to resolve the effusion, restore normal hearing (if diminished secondary to the effusion), and prevent future episodes or sequelae. The most significant complication of OME is permanent conductive hearing loss, but tinnitus, cholesteatoma, or tympanosclerosis may also occur.

In most patients, OME resolves without medical intervention. If additional action is required, however, the following options may be explored.

Medication. While the AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends against routine antibiotics for OME,17 it does note that a short course may provide short-term benefit to some patients (eg, those for whom a specialist referral or surgery is being considered).

A separate meta-analysis found that antibiotics improve clearance of the effusion within the first month after treatment (rate difference [RD]=0.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.03-0.29 in 12 studies analyzed), but effusion relapses were common, and no significant benefit was noted past the first month (RD=0.06; 95% CI, -0.03 to 0.14 in 8 studies).20

If you do use antibiotics, a 10- to 14-day course is preferred.17 Amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate and ceftibuten have been evaluated in separate clinical trials, but none has been clearly shown to have significant advantage over any other.21,22

Antihistamines, decongestants, and oral and intranasal corticosteroids have little effect on OME in children and are not recommended.17 A Cochrane review including 16 studies found that children receiving antihistamines and decongestants are unlikely to see their symptoms improve significantly, and many patients experience adverse effects from the medications23 (number needed to harm=9).

A randomized, double-blind trial involving 144 children <9 years of age with OME for at least 2 months evaluated 4 regimens involving amoxicillin alone or in combination with prednisolone. Children in the amoxicillin+prednisolone arms were significantly more likely to clear their effusions at 2 weeks (number needed to treat=6; P=.03), but not at 4 weeks (P=.12). At 4-month follow-up, effusions had recurred in 68.4% and 69.2% of those receiving amoxicillin+prednisolone and those receiving amoxicillin alone, respectively (P= .94).24

Surgery—or not? The AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends physicians perform hearing testing when OME is present for 3 months or longer, or at any time if language delay, learning problems, or a significant hearing loss is suspected in a child with OME. The results of the hearing test can help determine how to proceed, based on the hearing level noted for the better hearing ear.

You can manage children with hearing loss ≤20 dB and without speech, language, or developmental problems with watchful waiting. Children with hearing loss of 21 to 39 dB can be managed with watchful waiting or referred for surgery. If watchful waiting is pursued, there are interventions at home and at school that can help. These include speaking near the child, facing the child when speaking, and providing accommodations in school so the child sits closer to the teacher. Consider re-examination and repeat hearing tests every 3 to 6 months until the effusion has resolved or the child develops symptoms indicating surgical referral.

When hearing loss is ≥40 dB, the AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends that you make a referral for surgical evaluation (ALGORITHM).17

Other indications for referral to a surgeon for evaluation of tympanostomy tube placement include situations in which there is:

• structural damage to the tympanic membrane or middle ear (prompt referral is recommended)

• OME of ≥4 months’ duration with persistent hearing loss (≥40 dB) or other signs or symptoms related to the effusion

• bilateral OME for ≥3 months, unilateral OME ≥6 months, or total duration of any degree of OME ≥12 months.17

Any decision regarding surgery should involve an otolaryngologist, the primary care provider, and the patient and/or family. The AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends against adenoidectomy in children with persistent OME without an indication for the procedure other than OME (eg, chronic sinusitis or nasal obstruction).17

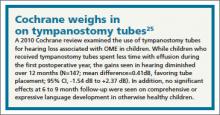

Keep in mind that evidence of lasting benefit (>12 months) is limited for surgery in most patients, and the surgical and anesthetic risks must be considered before moving forward.17 (For more on the evidence regarding surgery, see “Cochrane weighs in on tympanostomy tubes”.25) Tonsillectomy also does not appear to affect outcomes and is not advised.17

When a referral is always needed. Regardless of hearing status, promptly refer children with recurrent or persistent OME who are at risk of speech, language, or learning problems (including those with autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, Down’s syndrome, diagnosed speech or language delay, or craniofacial disorders such as cleft palate) to a specialist.17

CASE › You tell your young patient’s mother that watchful waiting is appropriate at this point, since his acute otitis media was only 2 weeks ago, and his OME likely started after the acute infection. Given that his speech is clear and he is otherwise meeting his milestones, you tell her that he does not need a referral at this time, but that she should bring him back in 4 weeks for reassessment. At the next visit, his effusion has resolved, and his mother reports he is sleeping well through the night again.

1. Lesinskas E. Factors affecting the results of nonsurgical treatment of secretory otitis media in adults. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003:30:7-14.

2. Chole RA, HH Sudhoff. Chronic otitis media, mastoiditis, and petrosis. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, MO. Mosby;2010:chap 139.

3. Casselbrant ML, Brostoff LM, Cantekin EI, et al. Otitis media with effusion in preschool children. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:428-436.

4. Lous J, Fiellau-Nikolajsen M. Epidemiology of middle-ear effusion and tubal dysfunction: a one year prospective study comprising monthly tympanometry in 387 non-selected seven-yearold children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1981;3:303-317.

5. Tos M, Holm-Jensen S, Sørensen CH. Changes in prevalence of secretory otitis from summer to winter in four-year-old children. Am J Otol. 1981;2:324-327.

6. Vernacchio L, Lesko SM, Vezina RM, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the diagnosis of otitis media in infancy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:795-804.

7. Owen MJ, Baldwin CD, Swank PR, et al. Relation of infant feeding practices, cigarette smoke exposure, and group child care to the onset and duration of otitis media with effusion in the first two years of life. J Pediatr. 1993;123:702-711.

8. Gultekin E, Develio˘gu ON, Yener M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for persistent otitis media with effusion in primary school children in Istanbul, Turkey. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37:145-149.

9. Depreux FF, Darrow K, Conner DA, et al. Eya4-deficient mice are a model for heritable otitis media. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:651-658.

10. Poetker DM, Lindstrom DR, Edmiston CE, et al. Microbiology of middle ear effusions from 292 patients undergoing tympanostomy tube placement for middle ear disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:799-804.

11. Hall-Stoodley L, Hu FZ, Gieseke A, et al. Direct detection of bacterial biofilms on the middle-ear mucosa of children with chronic otitis media. JAMA. 2006;296:202-211.

12. Brook I, Yocum P, Shah K, et al. Microbiology of serous otitis media in children: correlation with age and length of effusion. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:87-90.

13. Alles R, Parikh A, Hawk L, et al. The prevalence of atopic disorders in children with chronic otitis media with effusion. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2001;12:102-106.

14. Lieu JE, Muthappan PG, Uppaluri R. Association of reflux with otitis media in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:357-361.

15. O’Reilly RC, He Z, Bloedon E, et al. The role of extraesophageal reflux in otitis media in infants and children. Laryngoscope. 2008;118 (7 part 2, suppl 116):S1-S9.

16. Rosenfeld RM, Goldsmith AJ, Tetlus L, et al. Quality of life for children with otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1049-1054.

17. American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media With Effusion. Otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1412-1429.

18. Perera R, Glasziou PP, Heneghan CJ, et al Autoinflation for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD006285.

19. Stangerup SE, Sederberg-Olsen J, Balle V. Autoinflation as a treatment of secretory otitis media. A randomized controlled study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:149-152.

20. Williams RL, Chalmers TC, Stange KC, et al. Use of antibiotics in preventing recurrent acute otitis media and in treating otitis media with effusion. A meta-analytic attempt to resolve the brouhaha. JAMA. 1993;270:1344-1351.

21. Mandel EM, Casselbrant ML, Kurs-Lasky M, et al. Efficacy of ceftibuten compared with amoxicillin for otitis media with effusion in infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:409-414.

22. Chan KH, Mandel EM, Rockette HE, et al. A comparative study of amoxicillin-clavulanate and amoxicillin. Treatment of otitis media with effusion. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988; 114:142-146.

23. Griffin G, Flynn CA. Antihistamines and/or decongestants for otitis media with effusion (OME) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD003423.

24. Mandel EM, Casselbrant ML, Rockette HE, et al. Systemic steroid for chronic otitis media with effusion in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1071-1080.

25. Browning GG, Rovers MM, Williamson I, et al. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD001801.

› Perform a hearing test when otitis media with effusion is present for 3 months or longer, or whenever you suspect a language delay, learning problems, or a significant hearing loss. C

› Use the results of the hearing test to guide management decisions. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › A mother brings in her 3-year-old son for a regular check-up. Her only concern is that for the past 2 weeks, he has not been sleeping through the night. She indicates that the sleeping problem began after he was diagnosed with and treated for an ear infection. Fortunately, this hasn’t affected his daily activity or energy, she says.

The child’s appetite is good and he speaks clearly, in 5-word sentences. He is meeting his developmental milestones, and appears well—sitting in his mother’s lap and playing with her smartphone. His head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat exam only turns up fluid behind his left tympanic membrane, which is not red or bulging. The right membrane appears normal, and he has no cervical lymphadenopathy. The rest of his exam is normal. How would you manage a patient like this?

"Glue ear" is often asymptomatic

Otitis media with effusion (OME) is defined as middle-ear effusion (MEE) in the absence of acute signs of infection. In children, OME—also referred to as “glue ear”—most often arises after acute otitis media (AOM). In adults, it often occurs in association with eustachian tube dysfunction, although OME is a separate diagnosis. (To learn more, see “What about OME in adults?”1,2.)

Experts have found it difficult to determine the exact incidence of OME because it is often asymptomatic. In addition, many cases quickly resolve on their own, making it challenging to diagnose. A 2-year prospective study of 2- to 6-year-old preschoolers revealed that MEE, diagnosed via monthly otoscopy and tympanometry, occurred at least once in 53% of the children in the first year and in 61% of the children in the second year.3 A second study followed 7-year-olds monthly for one year and found a 31% incidence of MEE using tympanometry.4 In the 25% of children found to have persistent MEE, the researchers noted spontaneous recovery after an average of 2 months.

We believe that nearly all children have experienced one episode of OME by the age of 3 years, but the prevalence of OME varies with age and the time of year. It is more prevalent in the winter than the summer months.5 OME is more common in Caucasian children than in African American or Asian children.6

Etiology remains elusive

Risk factors for children include a family history of OME, bottle-feeding, day care attendance, exposure to tobacco smoke, and a personal history of allergies.7,8 One study conducted on mice suggested that inherited structural abnormalities of the middle ear and eustachian tube may play a role as well.9 Some have suggested that effusions of OME in children result from chronic inflammation, for example, after AOM, and that the effusions are sterile; however, recent studies have demonstrated that a biofilm is formed by bacterial otopathogens in the effusion.10-12 The common pathogens found include nontypeable Haemophilus influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Inflammatory exudate or neutrophil infiltration is rare in the fluid, however.

The contribution of allergies to OME in children remains somewhat controversial. A retrospective review from the United Kingdom of 209 children with OME found a history of allergic rhinitis, asthma, and eczema in 89%, 36%, and 24%, respectively.13 However, this study was done at an allergy clinic, and it is possible that the data from the clinic’s specialized patient population are not generalizable. Gastroesophageal reflux may also be associated with OME in children. However, studies measuring the concentration of pepsin and pepsinogen in middle-ear fluid have provided conflicting results.14,15

Look for these signs and symptoms

OME is often asymptomatic. If a patient has clinical signs of an acute illness, including fever and an erythematous tympanic membrane, it’s important to evaluate for another cause. OME can present with hearing loss or a sense of fullness in the ear. While an infant cannot express the hearing loss, the parent may detect it when observing and interacting mwith the child. Parents are also likely to report that the child is experiencing sleep disturbances.16

Vertigo may occur with OME, although not often. It may manifest itself if the child stumbles or falls. An older child or adult with vertigo may say that it feels like the room is spinning.

Diagnosis relies on pneumatic otoscopy

On physical exam, the patient will likely appear well. Otoscopic examination reveals fluid behind a normal or retracted tympanic membrane; the fluid is often clear or yellowish in color.

A subcommittee comprised of members of the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS) published a clinical practice guideline in 2004 that delineates the current diagnosis and management of children between 2 months and 12 years of age with OME.17

Pneumatic otoscopy, which can reveal decreased or absent movement of the tympanic membrane (the result of fluid behind the membrane), is the primary diagnostic method recommended by the guideline. Tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry may also be used to make the diagnosis, especially when the presence of MEE is difficult to determine using pneumatic otoscopy.

CASE › Upon further discussion with the patient’s mother, you learn that the boy goes to day care 3 days a week and stays with his grandmother 2 days a week. His grandmother smokes outside of the home when he is staying with her.

After reviewing these risk factors with the mother (including the importance of smoking cessation for the grandmother), the mother asks if he needs antibiotics or a referral to a specialist for treating his OME.

How best to approach treatment

There are several management options to choose from, including watchful waiting, medication, and/or surgery. (Another option, autoinflation, which has shown some short-term benefits, is described in “Should you recommend autoinflation?”17-19.)

The goals of management are to resolve the effusion, restore normal hearing (if diminished secondary to the effusion), and prevent future episodes or sequelae. The most significant complication of OME is permanent conductive hearing loss, but tinnitus, cholesteatoma, or tympanosclerosis may also occur.

In most patients, OME resolves without medical intervention. If additional action is required, however, the following options may be explored.

Medication. While the AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends against routine antibiotics for OME,17 it does note that a short course may provide short-term benefit to some patients (eg, those for whom a specialist referral or surgery is being considered).

A separate meta-analysis found that antibiotics improve clearance of the effusion within the first month after treatment (rate difference [RD]=0.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.03-0.29 in 12 studies analyzed), but effusion relapses were common, and no significant benefit was noted past the first month (RD=0.06; 95% CI, -0.03 to 0.14 in 8 studies).20

If you do use antibiotics, a 10- to 14-day course is preferred.17 Amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate and ceftibuten have been evaluated in separate clinical trials, but none has been clearly shown to have significant advantage over any other.21,22

Antihistamines, decongestants, and oral and intranasal corticosteroids have little effect on OME in children and are not recommended.17 A Cochrane review including 16 studies found that children receiving antihistamines and decongestants are unlikely to see their symptoms improve significantly, and many patients experience adverse effects from the medications23 (number needed to harm=9).

A randomized, double-blind trial involving 144 children <9 years of age with OME for at least 2 months evaluated 4 regimens involving amoxicillin alone or in combination with prednisolone. Children in the amoxicillin+prednisolone arms were significantly more likely to clear their effusions at 2 weeks (number needed to treat=6; P=.03), but not at 4 weeks (P=.12). At 4-month follow-up, effusions had recurred in 68.4% and 69.2% of those receiving amoxicillin+prednisolone and those receiving amoxicillin alone, respectively (P= .94).24

Surgery—or not? The AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends physicians perform hearing testing when OME is present for 3 months or longer, or at any time if language delay, learning problems, or a significant hearing loss is suspected in a child with OME. The results of the hearing test can help determine how to proceed, based on the hearing level noted for the better hearing ear.

You can manage children with hearing loss ≤20 dB and without speech, language, or developmental problems with watchful waiting. Children with hearing loss of 21 to 39 dB can be managed with watchful waiting or referred for surgery. If watchful waiting is pursued, there are interventions at home and at school that can help. These include speaking near the child, facing the child when speaking, and providing accommodations in school so the child sits closer to the teacher. Consider re-examination and repeat hearing tests every 3 to 6 months until the effusion has resolved or the child develops symptoms indicating surgical referral.

When hearing loss is ≥40 dB, the AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends that you make a referral for surgical evaluation (ALGORITHM).17

Other indications for referral to a surgeon for evaluation of tympanostomy tube placement include situations in which there is:

• structural damage to the tympanic membrane or middle ear (prompt referral is recommended)

• OME of ≥4 months’ duration with persistent hearing loss (≥40 dB) or other signs or symptoms related to the effusion

• bilateral OME for ≥3 months, unilateral OME ≥6 months, or total duration of any degree of OME ≥12 months.17

Any decision regarding surgery should involve an otolaryngologist, the primary care provider, and the patient and/or family. The AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends against adenoidectomy in children with persistent OME without an indication for the procedure other than OME (eg, chronic sinusitis or nasal obstruction).17

Keep in mind that evidence of lasting benefit (>12 months) is limited for surgery in most patients, and the surgical and anesthetic risks must be considered before moving forward.17 (For more on the evidence regarding surgery, see “Cochrane weighs in on tympanostomy tubes”.25) Tonsillectomy also does not appear to affect outcomes and is not advised.17

When a referral is always needed. Regardless of hearing status, promptly refer children with recurrent or persistent OME who are at risk of speech, language, or learning problems (including those with autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, Down’s syndrome, diagnosed speech or language delay, or craniofacial disorders such as cleft palate) to a specialist.17

CASE › You tell your young patient’s mother that watchful waiting is appropriate at this point, since his acute otitis media was only 2 weeks ago, and his OME likely started after the acute infection. Given that his speech is clear and he is otherwise meeting his milestones, you tell her that he does not need a referral at this time, but that she should bring him back in 4 weeks for reassessment. At the next visit, his effusion has resolved, and his mother reports he is sleeping well through the night again.

› Perform a hearing test when otitis media with effusion is present for 3 months or longer, or whenever you suspect a language delay, learning problems, or a significant hearing loss. C

› Use the results of the hearing test to guide management decisions. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › A mother brings in her 3-year-old son for a regular check-up. Her only concern is that for the past 2 weeks, he has not been sleeping through the night. She indicates that the sleeping problem began after he was diagnosed with and treated for an ear infection. Fortunately, this hasn’t affected his daily activity or energy, she says.

The child’s appetite is good and he speaks clearly, in 5-word sentences. He is meeting his developmental milestones, and appears well—sitting in his mother’s lap and playing with her smartphone. His head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat exam only turns up fluid behind his left tympanic membrane, which is not red or bulging. The right membrane appears normal, and he has no cervical lymphadenopathy. The rest of his exam is normal. How would you manage a patient like this?

"Glue ear" is often asymptomatic

Otitis media with effusion (OME) is defined as middle-ear effusion (MEE) in the absence of acute signs of infection. In children, OME—also referred to as “glue ear”—most often arises after acute otitis media (AOM). In adults, it often occurs in association with eustachian tube dysfunction, although OME is a separate diagnosis. (To learn more, see “What about OME in adults?”1,2.)

Experts have found it difficult to determine the exact incidence of OME because it is often asymptomatic. In addition, many cases quickly resolve on their own, making it challenging to diagnose. A 2-year prospective study of 2- to 6-year-old preschoolers revealed that MEE, diagnosed via monthly otoscopy and tympanometry, occurred at least once in 53% of the children in the first year and in 61% of the children in the second year.3 A second study followed 7-year-olds monthly for one year and found a 31% incidence of MEE using tympanometry.4 In the 25% of children found to have persistent MEE, the researchers noted spontaneous recovery after an average of 2 months.

We believe that nearly all children have experienced one episode of OME by the age of 3 years, but the prevalence of OME varies with age and the time of year. It is more prevalent in the winter than the summer months.5 OME is more common in Caucasian children than in African American or Asian children.6

Etiology remains elusive

Risk factors for children include a family history of OME, bottle-feeding, day care attendance, exposure to tobacco smoke, and a personal history of allergies.7,8 One study conducted on mice suggested that inherited structural abnormalities of the middle ear and eustachian tube may play a role as well.9 Some have suggested that effusions of OME in children result from chronic inflammation, for example, after AOM, and that the effusions are sterile; however, recent studies have demonstrated that a biofilm is formed by bacterial otopathogens in the effusion.10-12 The common pathogens found include nontypeable Haemophilus influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Inflammatory exudate or neutrophil infiltration is rare in the fluid, however.

The contribution of allergies to OME in children remains somewhat controversial. A retrospective review from the United Kingdom of 209 children with OME found a history of allergic rhinitis, asthma, and eczema in 89%, 36%, and 24%, respectively.13 However, this study was done at an allergy clinic, and it is possible that the data from the clinic’s specialized patient population are not generalizable. Gastroesophageal reflux may also be associated with OME in children. However, studies measuring the concentration of pepsin and pepsinogen in middle-ear fluid have provided conflicting results.14,15

Look for these signs and symptoms

OME is often asymptomatic. If a patient has clinical signs of an acute illness, including fever and an erythematous tympanic membrane, it’s important to evaluate for another cause. OME can present with hearing loss or a sense of fullness in the ear. While an infant cannot express the hearing loss, the parent may detect it when observing and interacting mwith the child. Parents are also likely to report that the child is experiencing sleep disturbances.16

Vertigo may occur with OME, although not often. It may manifest itself if the child stumbles or falls. An older child or adult with vertigo may say that it feels like the room is spinning.

Diagnosis relies on pneumatic otoscopy

On physical exam, the patient will likely appear well. Otoscopic examination reveals fluid behind a normal or retracted tympanic membrane; the fluid is often clear or yellowish in color.

A subcommittee comprised of members of the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS) published a clinical practice guideline in 2004 that delineates the current diagnosis and management of children between 2 months and 12 years of age with OME.17

Pneumatic otoscopy, which can reveal decreased or absent movement of the tympanic membrane (the result of fluid behind the membrane), is the primary diagnostic method recommended by the guideline. Tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry may also be used to make the diagnosis, especially when the presence of MEE is difficult to determine using pneumatic otoscopy.

CASE › Upon further discussion with the patient’s mother, you learn that the boy goes to day care 3 days a week and stays with his grandmother 2 days a week. His grandmother smokes outside of the home when he is staying with her.

After reviewing these risk factors with the mother (including the importance of smoking cessation for the grandmother), the mother asks if he needs antibiotics or a referral to a specialist for treating his OME.

How best to approach treatment

There are several management options to choose from, including watchful waiting, medication, and/or surgery. (Another option, autoinflation, which has shown some short-term benefits, is described in “Should you recommend autoinflation?”17-19.)

The goals of management are to resolve the effusion, restore normal hearing (if diminished secondary to the effusion), and prevent future episodes or sequelae. The most significant complication of OME is permanent conductive hearing loss, but tinnitus, cholesteatoma, or tympanosclerosis may also occur.

In most patients, OME resolves without medical intervention. If additional action is required, however, the following options may be explored.

Medication. While the AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends against routine antibiotics for OME,17 it does note that a short course may provide short-term benefit to some patients (eg, those for whom a specialist referral or surgery is being considered).

A separate meta-analysis found that antibiotics improve clearance of the effusion within the first month after treatment (rate difference [RD]=0.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.03-0.29 in 12 studies analyzed), but effusion relapses were common, and no significant benefit was noted past the first month (RD=0.06; 95% CI, -0.03 to 0.14 in 8 studies).20

If you do use antibiotics, a 10- to 14-day course is preferred.17 Amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate and ceftibuten have been evaluated in separate clinical trials, but none has been clearly shown to have significant advantage over any other.21,22

Antihistamines, decongestants, and oral and intranasal corticosteroids have little effect on OME in children and are not recommended.17 A Cochrane review including 16 studies found that children receiving antihistamines and decongestants are unlikely to see their symptoms improve significantly, and many patients experience adverse effects from the medications23 (number needed to harm=9).

A randomized, double-blind trial involving 144 children <9 years of age with OME for at least 2 months evaluated 4 regimens involving amoxicillin alone or in combination with prednisolone. Children in the amoxicillin+prednisolone arms were significantly more likely to clear their effusions at 2 weeks (number needed to treat=6; P=.03), but not at 4 weeks (P=.12). At 4-month follow-up, effusions had recurred in 68.4% and 69.2% of those receiving amoxicillin+prednisolone and those receiving amoxicillin alone, respectively (P= .94).24

Surgery—or not? The AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends physicians perform hearing testing when OME is present for 3 months or longer, or at any time if language delay, learning problems, or a significant hearing loss is suspected in a child with OME. The results of the hearing test can help determine how to proceed, based on the hearing level noted for the better hearing ear.

You can manage children with hearing loss ≤20 dB and without speech, language, or developmental problems with watchful waiting. Children with hearing loss of 21 to 39 dB can be managed with watchful waiting or referred for surgery. If watchful waiting is pursued, there are interventions at home and at school that can help. These include speaking near the child, facing the child when speaking, and providing accommodations in school so the child sits closer to the teacher. Consider re-examination and repeat hearing tests every 3 to 6 months until the effusion has resolved or the child develops symptoms indicating surgical referral.

When hearing loss is ≥40 dB, the AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends that you make a referral for surgical evaluation (ALGORITHM).17

Other indications for referral to a surgeon for evaluation of tympanostomy tube placement include situations in which there is:

• structural damage to the tympanic membrane or middle ear (prompt referral is recommended)

• OME of ≥4 months’ duration with persistent hearing loss (≥40 dB) or other signs or symptoms related to the effusion

• bilateral OME for ≥3 months, unilateral OME ≥6 months, or total duration of any degree of OME ≥12 months.17

Any decision regarding surgery should involve an otolaryngologist, the primary care provider, and the patient and/or family. The AAP/AAFP/AAOHNS guideline recommends against adenoidectomy in children with persistent OME without an indication for the procedure other than OME (eg, chronic sinusitis or nasal obstruction).17

Keep in mind that evidence of lasting benefit (>12 months) is limited for surgery in most patients, and the surgical and anesthetic risks must be considered before moving forward.17 (For more on the evidence regarding surgery, see “Cochrane weighs in on tympanostomy tubes”.25) Tonsillectomy also does not appear to affect outcomes and is not advised.17

When a referral is always needed. Regardless of hearing status, promptly refer children with recurrent or persistent OME who are at risk of speech, language, or learning problems (including those with autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, Down’s syndrome, diagnosed speech or language delay, or craniofacial disorders such as cleft palate) to a specialist.17

CASE › You tell your young patient’s mother that watchful waiting is appropriate at this point, since his acute otitis media was only 2 weeks ago, and his OME likely started after the acute infection. Given that his speech is clear and he is otherwise meeting his milestones, you tell her that he does not need a referral at this time, but that she should bring him back in 4 weeks for reassessment. At the next visit, his effusion has resolved, and his mother reports he is sleeping well through the night again.

1. Lesinskas E. Factors affecting the results of nonsurgical treatment of secretory otitis media in adults. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003:30:7-14.

2. Chole RA, HH Sudhoff. Chronic otitis media, mastoiditis, and petrosis. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, MO. Mosby;2010:chap 139.

3. Casselbrant ML, Brostoff LM, Cantekin EI, et al. Otitis media with effusion in preschool children. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:428-436.

4. Lous J, Fiellau-Nikolajsen M. Epidemiology of middle-ear effusion and tubal dysfunction: a one year prospective study comprising monthly tympanometry in 387 non-selected seven-yearold children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1981;3:303-317.

5. Tos M, Holm-Jensen S, Sørensen CH. Changes in prevalence of secretory otitis from summer to winter in four-year-old children. Am J Otol. 1981;2:324-327.

6. Vernacchio L, Lesko SM, Vezina RM, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the diagnosis of otitis media in infancy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:795-804.

7. Owen MJ, Baldwin CD, Swank PR, et al. Relation of infant feeding practices, cigarette smoke exposure, and group child care to the onset and duration of otitis media with effusion in the first two years of life. J Pediatr. 1993;123:702-711.

8. Gultekin E, Develio˘gu ON, Yener M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for persistent otitis media with effusion in primary school children in Istanbul, Turkey. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37:145-149.

9. Depreux FF, Darrow K, Conner DA, et al. Eya4-deficient mice are a model for heritable otitis media. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:651-658.

10. Poetker DM, Lindstrom DR, Edmiston CE, et al. Microbiology of middle ear effusions from 292 patients undergoing tympanostomy tube placement for middle ear disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:799-804.

11. Hall-Stoodley L, Hu FZ, Gieseke A, et al. Direct detection of bacterial biofilms on the middle-ear mucosa of children with chronic otitis media. JAMA. 2006;296:202-211.

12. Brook I, Yocum P, Shah K, et al. Microbiology of serous otitis media in children: correlation with age and length of effusion. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:87-90.

13. Alles R, Parikh A, Hawk L, et al. The prevalence of atopic disorders in children with chronic otitis media with effusion. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2001;12:102-106.

14. Lieu JE, Muthappan PG, Uppaluri R. Association of reflux with otitis media in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:357-361.

15. O’Reilly RC, He Z, Bloedon E, et al. The role of extraesophageal reflux in otitis media in infants and children. Laryngoscope. 2008;118 (7 part 2, suppl 116):S1-S9.

16. Rosenfeld RM, Goldsmith AJ, Tetlus L, et al. Quality of life for children with otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1049-1054.

17. American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media With Effusion. Otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1412-1429.

18. Perera R, Glasziou PP, Heneghan CJ, et al Autoinflation for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD006285.

19. Stangerup SE, Sederberg-Olsen J, Balle V. Autoinflation as a treatment of secretory otitis media. A randomized controlled study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:149-152.

20. Williams RL, Chalmers TC, Stange KC, et al. Use of antibiotics in preventing recurrent acute otitis media and in treating otitis media with effusion. A meta-analytic attempt to resolve the brouhaha. JAMA. 1993;270:1344-1351.

21. Mandel EM, Casselbrant ML, Kurs-Lasky M, et al. Efficacy of ceftibuten compared with amoxicillin for otitis media with effusion in infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:409-414.

22. Chan KH, Mandel EM, Rockette HE, et al. A comparative study of amoxicillin-clavulanate and amoxicillin. Treatment of otitis media with effusion. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988; 114:142-146.

23. Griffin G, Flynn CA. Antihistamines and/or decongestants for otitis media with effusion (OME) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD003423.

24. Mandel EM, Casselbrant ML, Rockette HE, et al. Systemic steroid for chronic otitis media with effusion in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1071-1080.

25. Browning GG, Rovers MM, Williamson I, et al. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD001801.

1. Lesinskas E. Factors affecting the results of nonsurgical treatment of secretory otitis media in adults. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003:30:7-14.

2. Chole RA, HH Sudhoff. Chronic otitis media, mastoiditis, and petrosis. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 5th ed. Maryland Heights, MO. Mosby;2010:chap 139.

3. Casselbrant ML, Brostoff LM, Cantekin EI, et al. Otitis media with effusion in preschool children. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:428-436.

4. Lous J, Fiellau-Nikolajsen M. Epidemiology of middle-ear effusion and tubal dysfunction: a one year prospective study comprising monthly tympanometry in 387 non-selected seven-yearold children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1981;3:303-317.

5. Tos M, Holm-Jensen S, Sørensen CH. Changes in prevalence of secretory otitis from summer to winter in four-year-old children. Am J Otol. 1981;2:324-327.

6. Vernacchio L, Lesko SM, Vezina RM, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the diagnosis of otitis media in infancy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:795-804.

7. Owen MJ, Baldwin CD, Swank PR, et al. Relation of infant feeding practices, cigarette smoke exposure, and group child care to the onset and duration of otitis media with effusion in the first two years of life. J Pediatr. 1993;123:702-711.

8. Gultekin E, Develio˘gu ON, Yener M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for persistent otitis media with effusion in primary school children in Istanbul, Turkey. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37:145-149.

9. Depreux FF, Darrow K, Conner DA, et al. Eya4-deficient mice are a model for heritable otitis media. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:651-658.

10. Poetker DM, Lindstrom DR, Edmiston CE, et al. Microbiology of middle ear effusions from 292 patients undergoing tympanostomy tube placement for middle ear disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:799-804.

11. Hall-Stoodley L, Hu FZ, Gieseke A, et al. Direct detection of bacterial biofilms on the middle-ear mucosa of children with chronic otitis media. JAMA. 2006;296:202-211.

12. Brook I, Yocum P, Shah K, et al. Microbiology of serous otitis media in children: correlation with age and length of effusion. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:87-90.

13. Alles R, Parikh A, Hawk L, et al. The prevalence of atopic disorders in children with chronic otitis media with effusion. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2001;12:102-106.

14. Lieu JE, Muthappan PG, Uppaluri R. Association of reflux with otitis media in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:357-361.

15. O’Reilly RC, He Z, Bloedon E, et al. The role of extraesophageal reflux in otitis media in infants and children. Laryngoscope. 2008;118 (7 part 2, suppl 116):S1-S9.

16. Rosenfeld RM, Goldsmith AJ, Tetlus L, et al. Quality of life for children with otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1049-1054.

17. American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media With Effusion. Otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1412-1429.

18. Perera R, Glasziou PP, Heneghan CJ, et al Autoinflation for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD006285.

19. Stangerup SE, Sederberg-Olsen J, Balle V. Autoinflation as a treatment of secretory otitis media. A randomized controlled study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:149-152.

20. Williams RL, Chalmers TC, Stange KC, et al. Use of antibiotics in preventing recurrent acute otitis media and in treating otitis media with effusion. A meta-analytic attempt to resolve the brouhaha. JAMA. 1993;270:1344-1351.

21. Mandel EM, Casselbrant ML, Kurs-Lasky M, et al. Efficacy of ceftibuten compared with amoxicillin for otitis media with effusion in infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:409-414.

22. Chan KH, Mandel EM, Rockette HE, et al. A comparative study of amoxicillin-clavulanate and amoxicillin. Treatment of otitis media with effusion. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988; 114:142-146.

23. Griffin G, Flynn CA. Antihistamines and/or decongestants for otitis media with effusion (OME) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD003423.

24. Mandel EM, Casselbrant ML, Rockette HE, et al. Systemic steroid for chronic otitis media with effusion in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1071-1080.

25. Browning GG, Rovers MM, Williamson I, et al. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD001801.