User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Physician groups push back on Medicaid block grant plan

It took less than a day for physician groups to start pushing back at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services over its new Medicaid block grant plan, which was introduced on Jan. 30.

Dubbed “Healthy Adult Opportunity,” the agency is offering all states the chance to participate in a block grant program through the 1115 waiver process.

According to a fact sheet issued by the agency, the program will focus on “adults under age 65 who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability or their need for long term care services and supports, and who are not eligible under a state plan. Other very low-income parents, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people eligible on the basis of a disability will not be directly affected – except from the improvement that results from states reinvesting savings into strengthening their overall programs.”

States will be operating within a defined budget when participating in the program and expenditures exceeding that defined budget will not be eligible for additional federal funding. Budgets will be based on a state’s historic costs, as well as national and regional trends, and will be tied to inflation with the potential to have adjustments made for extraordinary events. States can set their baseline using the prior year’s total spending or a per-enrollee spending model.

A Jan. 30 letter to state Medicaid directors notes that states participating in the program “will be granted extensive flexibility to test alternative approaches to implementing their Medicaid programs, including the ability to make many ongoing program adjustments without the need for demonstration or state plan amendments that require prior approval.”

Among the activities states can engage in under this plan are adjusting cost-sharing requirements, adopting a closed formulary, and applying additional conditions of eligibility. Requests, if approved, will be approved for a 5-year initial period, with a renewal option of up to 10 years.

But physician groups are not seeing a benefit with this new block grant program.

“Moving to a block grant system will likely limit the ability of Medicaid patients to receive preventive and needed medical care from their family physicians, and it will only increase the health disparities that exist in these communities, worsen overall health outcomes, and ultimately increase costs,” Gary LeRoy, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement.

The American Medical Association concurred.

“The AMA opposes caps on federal Medicaid funding, such as block grants, because they would increase the number of uninsured and undermine Medicaid’s role as an indispensable safety net,” Patrice Harris, MD, the AMA’s president, said in a statement. “The AMA supports flexibility in Medicaid and encourages CMS to work with states to develop and test new Medicaid models that best meet the needs and priorities of low-income patients. While encouraging flexibility, the AMA is mindful that expanding Medicaid has been a literal lifesaver for low-income patients. We need to find ways to build on this success. We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail.”

Officials at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the changes have the potential to harm women and children’s health, as well as negatively impact physician reimbursement and ultimately access to care.

“Limits on the federal contribution to the Medicaid program would negatively impact patients by forcing states to reduce the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid coverage, eliminate covered services, and increase beneficiary cost-sharing,” ACOG President Ted Anderson, MD, said in a statement. “ACOG is also concerned that this block grant opportunity could lower physician reimbursement for certain services, forcing providers out of the program and jeopardizing patients’ ability to access health care services. Given our nation’s stark rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, we are alarmed by the Administration’s willingness to weaken physician payment in Medicaid.”

It took less than a day for physician groups to start pushing back at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services over its new Medicaid block grant plan, which was introduced on Jan. 30.

Dubbed “Healthy Adult Opportunity,” the agency is offering all states the chance to participate in a block grant program through the 1115 waiver process.

According to a fact sheet issued by the agency, the program will focus on “adults under age 65 who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability or their need for long term care services and supports, and who are not eligible under a state plan. Other very low-income parents, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people eligible on the basis of a disability will not be directly affected – except from the improvement that results from states reinvesting savings into strengthening their overall programs.”

States will be operating within a defined budget when participating in the program and expenditures exceeding that defined budget will not be eligible for additional federal funding. Budgets will be based on a state’s historic costs, as well as national and regional trends, and will be tied to inflation with the potential to have adjustments made for extraordinary events. States can set their baseline using the prior year’s total spending or a per-enrollee spending model.

A Jan. 30 letter to state Medicaid directors notes that states participating in the program “will be granted extensive flexibility to test alternative approaches to implementing their Medicaid programs, including the ability to make many ongoing program adjustments without the need for demonstration or state plan amendments that require prior approval.”

Among the activities states can engage in under this plan are adjusting cost-sharing requirements, adopting a closed formulary, and applying additional conditions of eligibility. Requests, if approved, will be approved for a 5-year initial period, with a renewal option of up to 10 years.

But physician groups are not seeing a benefit with this new block grant program.

“Moving to a block grant system will likely limit the ability of Medicaid patients to receive preventive and needed medical care from their family physicians, and it will only increase the health disparities that exist in these communities, worsen overall health outcomes, and ultimately increase costs,” Gary LeRoy, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement.

The American Medical Association concurred.

“The AMA opposes caps on federal Medicaid funding, such as block grants, because they would increase the number of uninsured and undermine Medicaid’s role as an indispensable safety net,” Patrice Harris, MD, the AMA’s president, said in a statement. “The AMA supports flexibility in Medicaid and encourages CMS to work with states to develop and test new Medicaid models that best meet the needs and priorities of low-income patients. While encouraging flexibility, the AMA is mindful that expanding Medicaid has been a literal lifesaver for low-income patients. We need to find ways to build on this success. We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail.”

Officials at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the changes have the potential to harm women and children’s health, as well as negatively impact physician reimbursement and ultimately access to care.

“Limits on the federal contribution to the Medicaid program would negatively impact patients by forcing states to reduce the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid coverage, eliminate covered services, and increase beneficiary cost-sharing,” ACOG President Ted Anderson, MD, said in a statement. “ACOG is also concerned that this block grant opportunity could lower physician reimbursement for certain services, forcing providers out of the program and jeopardizing patients’ ability to access health care services. Given our nation’s stark rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, we are alarmed by the Administration’s willingness to weaken physician payment in Medicaid.”

It took less than a day for physician groups to start pushing back at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services over its new Medicaid block grant plan, which was introduced on Jan. 30.

Dubbed “Healthy Adult Opportunity,” the agency is offering all states the chance to participate in a block grant program through the 1115 waiver process.

According to a fact sheet issued by the agency, the program will focus on “adults under age 65 who are not eligible for Medicaid on the basis of disability or their need for long term care services and supports, and who are not eligible under a state plan. Other very low-income parents, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people eligible on the basis of a disability will not be directly affected – except from the improvement that results from states reinvesting savings into strengthening their overall programs.”

States will be operating within a defined budget when participating in the program and expenditures exceeding that defined budget will not be eligible for additional federal funding. Budgets will be based on a state’s historic costs, as well as national and regional trends, and will be tied to inflation with the potential to have adjustments made for extraordinary events. States can set their baseline using the prior year’s total spending or a per-enrollee spending model.

A Jan. 30 letter to state Medicaid directors notes that states participating in the program “will be granted extensive flexibility to test alternative approaches to implementing their Medicaid programs, including the ability to make many ongoing program adjustments without the need for demonstration or state plan amendments that require prior approval.”

Among the activities states can engage in under this plan are adjusting cost-sharing requirements, adopting a closed formulary, and applying additional conditions of eligibility. Requests, if approved, will be approved for a 5-year initial period, with a renewal option of up to 10 years.

But physician groups are not seeing a benefit with this new block grant program.

“Moving to a block grant system will likely limit the ability of Medicaid patients to receive preventive and needed medical care from their family physicians, and it will only increase the health disparities that exist in these communities, worsen overall health outcomes, and ultimately increase costs,” Gary LeRoy, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement.

The American Medical Association concurred.

“The AMA opposes caps on federal Medicaid funding, such as block grants, because they would increase the number of uninsured and undermine Medicaid’s role as an indispensable safety net,” Patrice Harris, MD, the AMA’s president, said in a statement. “The AMA supports flexibility in Medicaid and encourages CMS to work with states to develop and test new Medicaid models that best meet the needs and priorities of low-income patients. While encouraging flexibility, the AMA is mindful that expanding Medicaid has been a literal lifesaver for low-income patients. We need to find ways to build on this success. We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail.”

Officials at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the changes have the potential to harm women and children’s health, as well as negatively impact physician reimbursement and ultimately access to care.

“Limits on the federal contribution to the Medicaid program would negatively impact patients by forcing states to reduce the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid coverage, eliminate covered services, and increase beneficiary cost-sharing,” ACOG President Ted Anderson, MD, said in a statement. “ACOG is also concerned that this block grant opportunity could lower physician reimbursement for certain services, forcing providers out of the program and jeopardizing patients’ ability to access health care services. Given our nation’s stark rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, we are alarmed by the Administration’s willingness to weaken physician payment in Medicaid.”

Is anxiety about the coronavirus out of proportion?

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.

In the meantime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, as of the week of Jan. 25, there have been 19 million cases of the flu in the United States. Of those stricken, 180,000 people have been hospitalized and 10,000 have died, including 68 pediatric patients. No cities are on lockdown, public transportation runs as usual, airports don’t screen passengers for flu symptoms, and Starbucks continues to serve vanilla lattes to any willing customer. Anxiety about illness is not new; we’ve seen it with SARS, Ebola, measles, and even around Chipotle’s food poisoning cases – to name just a few recent scares. We have also seen a lot of media on vaping-related deaths, and as of early January 2020, vaping-related illnesses affected 2,602 people with 59 deaths. It has been a topic of discussion among legislators, with an emphasis on either outlawing the flavoring that might appeal to younger people or simply outlawing e-cigarettes. No one, however, is talking about outlawing regular cigarettes, despite the fact that many people have switched from cigarettes to vaping products as a way to quit smoking. So, while vaping has caused 59 deaths since 2018, cigarettes are responsible for 480,000 fatalities a year in the United States and smokers live, on average, 10 years less than nonsmokers.

So what fuels anxiety about the latest health scare, and why aren’t we more anxious about the more common causes of premature mortality? Certainly, the newness and the unknown are factors in the coronavirus scare. It’s not certain how this illness was introduced into the human population, although one theory is that it started with the consumption of bats who carry the virus. It’s spreading fast, and in some people, it has been lethal. The incubation period is not known, or whether it is contagious before symptoms appear. Coronavirus is getting a lot of public health attention and the World Health Organization just announced that the virus is a public health emergency of international concern. On the televised news on Jan. 29, 2020, coronavirus was the top story in the United States, even though an impeachment trial is in progress for our country’s president.

The public health response of locking down cities may help contain the outbreak and prevent a global epidemic, although millions of people had already left Wuhan, so the heavy-handed attempt to prevent spread of the virus may well be too late. In the case of the Ebola virus – a much more lethal disease that was also thought to be introduced by bats – public health measures certainly curtailed global spread, and the epidemic of 2014-2016 was limited to 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths, nearly all of them in West Africa.

Most of the things that cause people to die are not new and are not topics the media chooses to sensationalize. Dissemination of news has changed over the decades, with so much more of it, instant reports on social media, and competition for viewers that leads journalists to pull at our emotions. And while we may, or may not, get flu shots and avoid those who have the flu, how and where we position both our anxiety and our resources does not always make sense. Certainly some people are predisposed to worry about both common and uncommon dangers, while others seem never to worry and engage in acts that many of us would consider dangerous. If we are looking for logic, it may be hard to find – there are those who would happily go bungee jumping but wouldn’t dream of leaving the house out without hand sanitizer.

The repercussions from this massive response to the Wuhan coronavirus are significant. For the millions of people on lockdown in China, each day gets emotionally harder; some may begin to have issues procuring food, and the financial losses for the economy will be significant. It’s not really possible to know yet if this response is warranted; we do know that infectious diseases can kill millions. The AIDS pandemic has taken the lives of 36 million people since 1981, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 resulted in an estimated 20 million to 50 million deaths after infecting 500 million people. Still, one might wonder if other, more mundane causes of morbidity and mortality – the ones that no longer garner our dread or make it to the front pages – might also be worthy of more hype and resources.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.

In the meantime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, as of the week of Jan. 25, there have been 19 million cases of the flu in the United States. Of those stricken, 180,000 people have been hospitalized and 10,000 have died, including 68 pediatric patients. No cities are on lockdown, public transportation runs as usual, airports don’t screen passengers for flu symptoms, and Starbucks continues to serve vanilla lattes to any willing customer. Anxiety about illness is not new; we’ve seen it with SARS, Ebola, measles, and even around Chipotle’s food poisoning cases – to name just a few recent scares. We have also seen a lot of media on vaping-related deaths, and as of early January 2020, vaping-related illnesses affected 2,602 people with 59 deaths. It has been a topic of discussion among legislators, with an emphasis on either outlawing the flavoring that might appeal to younger people or simply outlawing e-cigarettes. No one, however, is talking about outlawing regular cigarettes, despite the fact that many people have switched from cigarettes to vaping products as a way to quit smoking. So, while vaping has caused 59 deaths since 2018, cigarettes are responsible for 480,000 fatalities a year in the United States and smokers live, on average, 10 years less than nonsmokers.

So what fuels anxiety about the latest health scare, and why aren’t we more anxious about the more common causes of premature mortality? Certainly, the newness and the unknown are factors in the coronavirus scare. It’s not certain how this illness was introduced into the human population, although one theory is that it started with the consumption of bats who carry the virus. It’s spreading fast, and in some people, it has been lethal. The incubation period is not known, or whether it is contagious before symptoms appear. Coronavirus is getting a lot of public health attention and the World Health Organization just announced that the virus is a public health emergency of international concern. On the televised news on Jan. 29, 2020, coronavirus was the top story in the United States, even though an impeachment trial is in progress for our country’s president.

The public health response of locking down cities may help contain the outbreak and prevent a global epidemic, although millions of people had already left Wuhan, so the heavy-handed attempt to prevent spread of the virus may well be too late. In the case of the Ebola virus – a much more lethal disease that was also thought to be introduced by bats – public health measures certainly curtailed global spread, and the epidemic of 2014-2016 was limited to 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths, nearly all of them in West Africa.

Most of the things that cause people to die are not new and are not topics the media chooses to sensationalize. Dissemination of news has changed over the decades, with so much more of it, instant reports on social media, and competition for viewers that leads journalists to pull at our emotions. And while we may, or may not, get flu shots and avoid those who have the flu, how and where we position both our anxiety and our resources does not always make sense. Certainly some people are predisposed to worry about both common and uncommon dangers, while others seem never to worry and engage in acts that many of us would consider dangerous. If we are looking for logic, it may be hard to find – there are those who would happily go bungee jumping but wouldn’t dream of leaving the house out without hand sanitizer.

The repercussions from this massive response to the Wuhan coronavirus are significant. For the millions of people on lockdown in China, each day gets emotionally harder; some may begin to have issues procuring food, and the financial losses for the economy will be significant. It’s not really possible to know yet if this response is warranted; we do know that infectious diseases can kill millions. The AIDS pandemic has taken the lives of 36 million people since 1981, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 resulted in an estimated 20 million to 50 million deaths after infecting 500 million people. Still, one might wonder if other, more mundane causes of morbidity and mortality – the ones that no longer garner our dread or make it to the front pages – might also be worthy of more hype and resources.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.

In the meantime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, as of the week of Jan. 25, there have been 19 million cases of the flu in the United States. Of those stricken, 180,000 people have been hospitalized and 10,000 have died, including 68 pediatric patients. No cities are on lockdown, public transportation runs as usual, airports don’t screen passengers for flu symptoms, and Starbucks continues to serve vanilla lattes to any willing customer. Anxiety about illness is not new; we’ve seen it with SARS, Ebola, measles, and even around Chipotle’s food poisoning cases – to name just a few recent scares. We have also seen a lot of media on vaping-related deaths, and as of early January 2020, vaping-related illnesses affected 2,602 people with 59 deaths. It has been a topic of discussion among legislators, with an emphasis on either outlawing the flavoring that might appeal to younger people or simply outlawing e-cigarettes. No one, however, is talking about outlawing regular cigarettes, despite the fact that many people have switched from cigarettes to vaping products as a way to quit smoking. So, while vaping has caused 59 deaths since 2018, cigarettes are responsible for 480,000 fatalities a year in the United States and smokers live, on average, 10 years less than nonsmokers.

So what fuels anxiety about the latest health scare, and why aren’t we more anxious about the more common causes of premature mortality? Certainly, the newness and the unknown are factors in the coronavirus scare. It’s not certain how this illness was introduced into the human population, although one theory is that it started with the consumption of bats who carry the virus. It’s spreading fast, and in some people, it has been lethal. The incubation period is not known, or whether it is contagious before symptoms appear. Coronavirus is getting a lot of public health attention and the World Health Organization just announced that the virus is a public health emergency of international concern. On the televised news on Jan. 29, 2020, coronavirus was the top story in the United States, even though an impeachment trial is in progress for our country’s president.

The public health response of locking down cities may help contain the outbreak and prevent a global epidemic, although millions of people had already left Wuhan, so the heavy-handed attempt to prevent spread of the virus may well be too late. In the case of the Ebola virus – a much more lethal disease that was also thought to be introduced by bats – public health measures certainly curtailed global spread, and the epidemic of 2014-2016 was limited to 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths, nearly all of them in West Africa.

Most of the things that cause people to die are not new and are not topics the media chooses to sensationalize. Dissemination of news has changed over the decades, with so much more of it, instant reports on social media, and competition for viewers that leads journalists to pull at our emotions. And while we may, or may not, get flu shots and avoid those who have the flu, how and where we position both our anxiety and our resources does not always make sense. Certainly some people are predisposed to worry about both common and uncommon dangers, while others seem never to worry and engage in acts that many of us would consider dangerous. If we are looking for logic, it may be hard to find – there are those who would happily go bungee jumping but wouldn’t dream of leaving the house out without hand sanitizer.

The repercussions from this massive response to the Wuhan coronavirus are significant. For the millions of people on lockdown in China, each day gets emotionally harder; some may begin to have issues procuring food, and the financial losses for the economy will be significant. It’s not really possible to know yet if this response is warranted; we do know that infectious diseases can kill millions. The AIDS pandemic has taken the lives of 36 million people since 1981, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 resulted in an estimated 20 million to 50 million deaths after infecting 500 million people. Still, one might wonder if other, more mundane causes of morbidity and mortality – the ones that no longer garner our dread or make it to the front pages – might also be worthy of more hype and resources.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

CDC: Opioid prescribing and use rates down since 2010

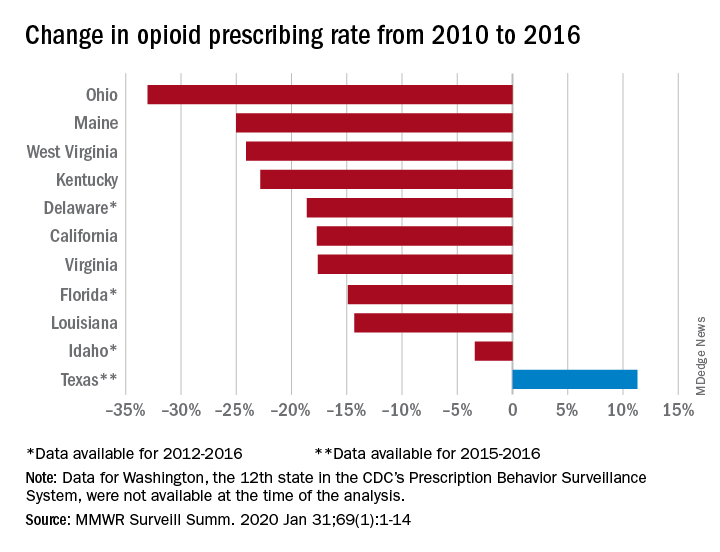

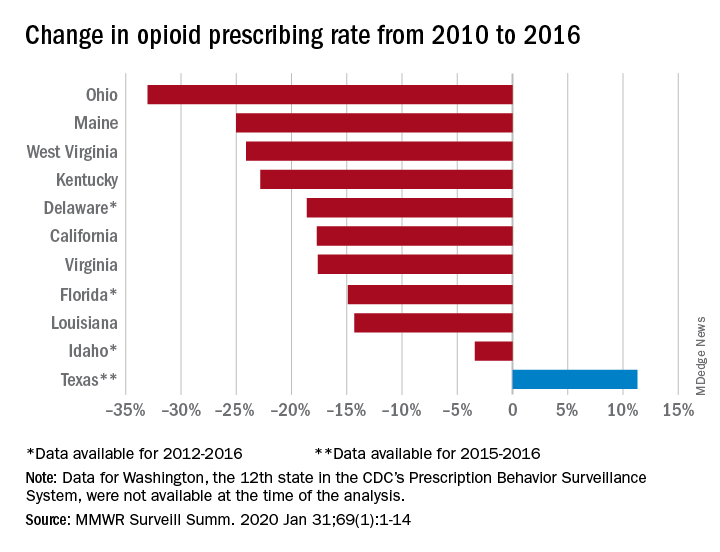

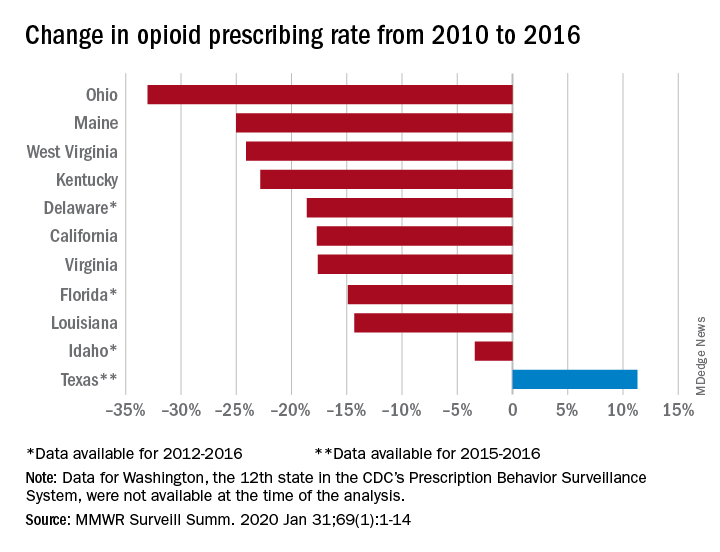

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

FROM MMWR SURVEILLANCE SUMMARIES

Dietary flavonol intake linked to reduced risk of Alzheimer’s

Onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was inversely associated with intake of flavonols, a subclass of flavonoids with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, according to the study authors.

The rate of developing AD was reduced by 50% among individuals reporting high intake of kaempferol, a flavonol plentiful in leafy green vegetables, and by 38% for high intake of the flavonols myricetin and isorhamnetin, researchers said in a report published in Neurology.

The findings are from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), a large, prospective study of older individuals in retirement communities and public housing in the Chicago area that has been ongoing since 1997.

“Although there is more work to be done, the associations that we observed are promising and deserve further study,” said Thomas M. Holland, MD, of the Rush Institute for Healthy Aging in Chicago, and coauthors.

Those associations between flavonol intake and AD help set the stage for U.S. POINTER and other randomized, controlled trials that seek to evaluate the effects of dietary interventions in a more rigorous way, according to Laura D. Baker, PhD, associate professor of internal medicine at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

“This kind of data helps us feel like we are looking in the right direction in the randomized, controlled trials,” Dr. Baker said in an interview.

Dr. Baker is an investigator in the U.S. POINTER study, which will in part evaluate the impact of the MIND diet, which has been shown to slow cognitive decline with age in a previously published MAP study.

However, in the absence of randomized, controlled trial data, Dr. Baker cautioned against “prematurely advocating” for specific dietary approaches when speaking to patients and caregivers now.

“What I say is, we know for sure that the standard American Heart Association diet has been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of heart disease, and in terms of brain health, if you can reduce risk of heart disease, you are protecting your brain,” she said in the interview.

The present MAP study linking a reduced rate of AD to flavonol consumption is believed to be the first of its kind, though two previous studies from the early 2000s did find inverse associations between incident AD and intake of flavonoids, of which flavonoids are just one subclass, said Dr. Holland and coinvestigators in their report.

Moreover, in a MAP study published in 2018, Martha Clare Morris, ScD, and coauthors concluded that consuming about a serving per day of green leafy vegetables and foods rich in kaempferol, among other nutrients and bioactive compounds, may help slow cognitive decline associated with aging.

To more specifically study the relationship between kaempferol and other flavonols and the development of AD, Dr. Holland and colleagues evaluated data for MAP participants who had completed a comprehensive food frequency questionnaire and underwent at least two evaluations to assess incidence of disease.

The mean age of the 921 individuals in the present analysis was 81 years, three-quarters were female, and over approximately 6 years of follow-up, 220 developed AD.

The rate of developing AD was 48% lower among participants reporting the highest total dietary intake of flavonols, compared with those reporting the lowest intake, Dr. Holland and coauthors reported.

Intake of the specific flavonols kaempferol, myricetin, and isorhamnetin were associated with incident AD reductions of 50%, 38%, and 38%, respectively. Another flavonol, quercetin, was by contrast not inversely associated with incident AD, according to the report.

Kaempferol was independently associated with AD in subsequent analyses, while there was no such independent association for myricetin, isorhamnetin, or quercetin, according to Dr. Holland and coinvestigators.

Further analyses of the data suggested the linkages between flavonols and AD were independent of lifestyle factors, dietary intakes, or cardiovascular conditions, they said in their report.

“Confirmation of these findings is warranted through other longitudinal epidemiologic studies and clinical trials, in addition to further elucidation of the biologic mechanisms,” they concluded.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the USDA Agricultural Research Service. Dr. Holland and coauthors said that they had no disclosures relevant to their report.

SOURCE: Holland TM et al. Neurology. 2020 Jan 29. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008981.

Onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was inversely associated with intake of flavonols, a subclass of flavonoids with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, according to the study authors.

The rate of developing AD was reduced by 50% among individuals reporting high intake of kaempferol, a flavonol plentiful in leafy green vegetables, and by 38% for high intake of the flavonols myricetin and isorhamnetin, researchers said in a report published in Neurology.

The findings are from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), a large, prospective study of older individuals in retirement communities and public housing in the Chicago area that has been ongoing since 1997.

“Although there is more work to be done, the associations that we observed are promising and deserve further study,” said Thomas M. Holland, MD, of the Rush Institute for Healthy Aging in Chicago, and coauthors.

Those associations between flavonol intake and AD help set the stage for U.S. POINTER and other randomized, controlled trials that seek to evaluate the effects of dietary interventions in a more rigorous way, according to Laura D. Baker, PhD, associate professor of internal medicine at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

“This kind of data helps us feel like we are looking in the right direction in the randomized, controlled trials,” Dr. Baker said in an interview.

Dr. Baker is an investigator in the U.S. POINTER study, which will in part evaluate the impact of the MIND diet, which has been shown to slow cognitive decline with age in a previously published MAP study.

However, in the absence of randomized, controlled trial data, Dr. Baker cautioned against “prematurely advocating” for specific dietary approaches when speaking to patients and caregivers now.

“What I say is, we know for sure that the standard American Heart Association diet has been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of heart disease, and in terms of brain health, if you can reduce risk of heart disease, you are protecting your brain,” she said in the interview.

The present MAP study linking a reduced rate of AD to flavonol consumption is believed to be the first of its kind, though two previous studies from the early 2000s did find inverse associations between incident AD and intake of flavonoids, of which flavonoids are just one subclass, said Dr. Holland and coinvestigators in their report.

Moreover, in a MAP study published in 2018, Martha Clare Morris, ScD, and coauthors concluded that consuming about a serving per day of green leafy vegetables and foods rich in kaempferol, among other nutrients and bioactive compounds, may help slow cognitive decline associated with aging.

To more specifically study the relationship between kaempferol and other flavonols and the development of AD, Dr. Holland and colleagues evaluated data for MAP participants who had completed a comprehensive food frequency questionnaire and underwent at least two evaluations to assess incidence of disease.

The mean age of the 921 individuals in the present analysis was 81 years, three-quarters were female, and over approximately 6 years of follow-up, 220 developed AD.

The rate of developing AD was 48% lower among participants reporting the highest total dietary intake of flavonols, compared with those reporting the lowest intake, Dr. Holland and coauthors reported.

Intake of the specific flavonols kaempferol, myricetin, and isorhamnetin were associated with incident AD reductions of 50%, 38%, and 38%, respectively. Another flavonol, quercetin, was by contrast not inversely associated with incident AD, according to the report.

Kaempferol was independently associated with AD in subsequent analyses, while there was no such independent association for myricetin, isorhamnetin, or quercetin, according to Dr. Holland and coinvestigators.

Further analyses of the data suggested the linkages between flavonols and AD were independent of lifestyle factors, dietary intakes, or cardiovascular conditions, they said in their report.

“Confirmation of these findings is warranted through other longitudinal epidemiologic studies and clinical trials, in addition to further elucidation of the biologic mechanisms,” they concluded.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the USDA Agricultural Research Service. Dr. Holland and coauthors said that they had no disclosures relevant to their report.

SOURCE: Holland TM et al. Neurology. 2020 Jan 29. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008981.

Onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was inversely associated with intake of flavonols, a subclass of flavonoids with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, according to the study authors.

The rate of developing AD was reduced by 50% among individuals reporting high intake of kaempferol, a flavonol plentiful in leafy green vegetables, and by 38% for high intake of the flavonols myricetin and isorhamnetin, researchers said in a report published in Neurology.

The findings are from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), a large, prospective study of older individuals in retirement communities and public housing in the Chicago area that has been ongoing since 1997.

“Although there is more work to be done, the associations that we observed are promising and deserve further study,” said Thomas M. Holland, MD, of the Rush Institute for Healthy Aging in Chicago, and coauthors.

Those associations between flavonol intake and AD help set the stage for U.S. POINTER and other randomized, controlled trials that seek to evaluate the effects of dietary interventions in a more rigorous way, according to Laura D. Baker, PhD, associate professor of internal medicine at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

“This kind of data helps us feel like we are looking in the right direction in the randomized, controlled trials,” Dr. Baker said in an interview.

Dr. Baker is an investigator in the U.S. POINTER study, which will in part evaluate the impact of the MIND diet, which has been shown to slow cognitive decline with age in a previously published MAP study.

However, in the absence of randomized, controlled trial data, Dr. Baker cautioned against “prematurely advocating” for specific dietary approaches when speaking to patients and caregivers now.

“What I say is, we know for sure that the standard American Heart Association diet has been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of heart disease, and in terms of brain health, if you can reduce risk of heart disease, you are protecting your brain,” she said in the interview.

The present MAP study linking a reduced rate of AD to flavonol consumption is believed to be the first of its kind, though two previous studies from the early 2000s did find inverse associations between incident AD and intake of flavonoids, of which flavonoids are just one subclass, said Dr. Holland and coinvestigators in their report.

Moreover, in a MAP study published in 2018, Martha Clare Morris, ScD, and coauthors concluded that consuming about a serving per day of green leafy vegetables and foods rich in kaempferol, among other nutrients and bioactive compounds, may help slow cognitive decline associated with aging.

To more specifically study the relationship between kaempferol and other flavonols and the development of AD, Dr. Holland and colleagues evaluated data for MAP participants who had completed a comprehensive food frequency questionnaire and underwent at least two evaluations to assess incidence of disease.

The mean age of the 921 individuals in the present analysis was 81 years, three-quarters were female, and over approximately 6 years of follow-up, 220 developed AD.

The rate of developing AD was 48% lower among participants reporting the highest total dietary intake of flavonols, compared with those reporting the lowest intake, Dr. Holland and coauthors reported.

Intake of the specific flavonols kaempferol, myricetin, and isorhamnetin were associated with incident AD reductions of 50%, 38%, and 38%, respectively. Another flavonol, quercetin, was by contrast not inversely associated with incident AD, according to the report.

Kaempferol was independently associated with AD in subsequent analyses, while there was no such independent association for myricetin, isorhamnetin, or quercetin, according to Dr. Holland and coinvestigators.

Further analyses of the data suggested the linkages between flavonols and AD were independent of lifestyle factors, dietary intakes, or cardiovascular conditions, they said in their report.

“Confirmation of these findings is warranted through other longitudinal epidemiologic studies and clinical trials, in addition to further elucidation of the biologic mechanisms,” they concluded.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the USDA Agricultural Research Service. Dr. Holland and coauthors said that they had no disclosures relevant to their report.

SOURCE: Holland TM et al. Neurology. 2020 Jan 29. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008981.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Understanding postpartum psychosis: From course to treatment

Although the last decade has brought appropriate increased interest in the diagnosis and treatment of postpartum depression, with screening initiatives across more than 40 states in place and even new medications being brought to market for treatment, far less attention has been given to diagnosis and treatment of a particularly serious psychiatric illness: postpartum psychosis.

Clinically, women can experience rapid mood changes, most often with the presentation that is consistent with a manic-like psychosis, with associated symptoms of delusional thinking, hallucinations, paranoia and either depression or elation, or an amalgam of these so-called “mixed symptoms.” Onset of symptoms typically is early, within 72 hours as is classically described, but may have a somewhat later time of onset in some women.

Many investigators have studied risk factors for postpartum psychosis, and it has been well established that a history of mood disorder, particularly bipolar disorder, is one of the strongest predictors of risk for postpartum psychosis. Women with histories of postpartum psychosis are at very high risk of recurrence, with as many as 70%-90% of women experiencing recurrence if not prophylaxed with an appropriate agent. From a clinical point of view, women with postpartum psychosis typically are hospitalized, given that this is both a psychiatric and potential obstetrical emergency. In fact, the data would suggest that although postpartum suicide and infanticide are not common, they can be a tragic concomitant of postpartum psychosis (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Dec 1;173[12]:1179-88).

A great amount of interest has been placed on the etiology of postpartum psychosis, as it’s a dramatic presentation with very rapid onset in the acute postpartum period. A rich evidence base with respect to an algorithm of treatment that maximizes likelihood of full recovery or sustaining of euthymia after recovery is limited. Few studies have looked systematically at the optimum way to treat postpartum psychosis. Clinical wisdom has dictated that, given the dramatic symptoms with which these patients present, most patients are treated with lithium and an antipsychotic medication as if they have a manic-like psychosis. It may take brief or extended periods of time for patients to stabilize. Once they are stabilized, one of the most challenging questions for clinicians is how long to treat. Again, an evidence base clearly informing this question is lacking.

Over the years, many clinicians have treated patients with postpartum psychosis as if they have bipolar disorder, given the index presentation of the illness, so some of these patients are treated with antimanic drugs indefinitely. However, clinical experience from several centers that treat women with postpartum psychosis suggests that in remitted patients, a proportion of them may be able to taper and discontinue treatment, then sustain well-being for protracted periods.

One obstacle with respect to treatment of postpartum psychosis derives from the short length of stay after delivery for many women. Some women who present with symptoms of postpartum psychosis in the first 24-48 hours frequently are managed with direct admission to an inpatient psychiatric service. But others may not develop symptoms until they are home, which may place both mother and newborn at risk.

Given that the risk for recurrent postpartum psychosis is so great (70%-90%), women with histories of postpartum psychosis invariably are prophylaxed with mood stabilizer prior to delivery in a subsequent pregnancy. In our own center, we have published on the value of such prophylactic intervention, not just in women with postpartum psychosis, but in women with bipolar disorder, who are, as noted, at great risk for developing postpartum psychotic symptoms (Am J Psychiatry. 1995 Nov;152[11]:1641-5.)

Although postpartum psychosis may be rare, over the last 3 decades we have seen a substantial number of women with postpartum psychosis and have been fascinated with the spectrum of symptoms with which some women with postpartum psychotic illness present. We also have been impressed with the time required for some women to recompensate from their illness and the course of their disorder after they have seemingly remitted. Some women appear to be able to discontinue treatment as noted above; others, particularly if there is any history of bipolar disorder, need to be maintained on treatment with mood stabilizer indefinitely.

To better understand the phenomenology of postpartum psychosis, as well as the longitudinal course of the illness, in 2019, the Mass General Hospital Postpartum Psychosis Project (MGHP3) was established. The project is conducted as a hospital-based registry where women with histories of postpartum psychosis over the last decade are invited to participate in an in-depth interview to understand both symptoms and course of underlying illness. This is complemented by obtaining a sample of saliva, which is used for genetic testing to try to identify a genetic underpinning associated with postpartum psychosis, as the question of genetic etiology of postpartum psychosis is still an open one.

As part of the MGHP3 project, clinicians across the country are able to contact perinatal psychiatrists in our center with expertise in the treatment of postpartum psychosis. Our psychiatrists also can counsel clinicians on issues regarding long-term management of postpartum psychosis because for many, knowledge of precisely how to manage this disorder or the follow-up treatment may be incomplete.

From a clinical point of view, the relevant questions really include not only acute treatment, which has already been outlined, but also the issue of duration of treatment. While some patients may be able to taper and discontinue treatment after, for example, a year of being totally well, to date we are unable to know who those patients are. We tend to be more conservative in our own center and treat patients with puerperal psychosis for a more protracted period of time, usually over several years. We also ask women about their family history of bipolar disorder or postpartum psychosis. Depending on the clinical course (if the patient really has sustained euthymia), we consider slow taper and ultimate discontinuation. As always, treatment decisions are tailored to individual clinical history, course, and patient wishes.

Postpartum psychosis remains one of the most serious illnesses that we find in reproductive psychiatry, and incomplete attention has been given to this devastating illness, which we read about periodically in newspapers and magazines. Greater understanding of postpartum psychosis will lead to a more precision-like psychiatric approach, tailoring treatment to the invariable heterogeneity of this illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Although the last decade has brought appropriate increased interest in the diagnosis and treatment of postpartum depression, with screening initiatives across more than 40 states in place and even new medications being brought to market for treatment, far less attention has been given to diagnosis and treatment of a particularly serious psychiatric illness: postpartum psychosis.

Clinically, women can experience rapid mood changes, most often with the presentation that is consistent with a manic-like psychosis, with associated symptoms of delusional thinking, hallucinations, paranoia and either depression or elation, or an amalgam of these so-called “mixed symptoms.” Onset of symptoms typically is early, within 72 hours as is classically described, but may have a somewhat later time of onset in some women.

Many investigators have studied risk factors for postpartum psychosis, and it has been well established that a history of mood disorder, particularly bipolar disorder, is one of the strongest predictors of risk for postpartum psychosis. Women with histories of postpartum psychosis are at very high risk of recurrence, with as many as 70%-90% of women experiencing recurrence if not prophylaxed with an appropriate agent. From a clinical point of view, women with postpartum psychosis typically are hospitalized, given that this is both a psychiatric and potential obstetrical emergency. In fact, the data would suggest that although postpartum suicide and infanticide are not common, they can be a tragic concomitant of postpartum psychosis (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Dec 1;173[12]:1179-88).

A great amount of interest has been placed on the etiology of postpartum psychosis, as it’s a dramatic presentation with very rapid onset in the acute postpartum period. A rich evidence base with respect to an algorithm of treatment that maximizes likelihood of full recovery or sustaining of euthymia after recovery is limited. Few studies have looked systematically at the optimum way to treat postpartum psychosis. Clinical wisdom has dictated that, given the dramatic symptoms with which these patients present, most patients are treated with lithium and an antipsychotic medication as if they have a manic-like psychosis. It may take brief or extended periods of time for patients to stabilize. Once they are stabilized, one of the most challenging questions for clinicians is how long to treat. Again, an evidence base clearly informing this question is lacking.

Over the years, many clinicians have treated patients with postpartum psychosis as if they have bipolar disorder, given the index presentation of the illness, so some of these patients are treated with antimanic drugs indefinitely. However, clinical experience from several centers that treat women with postpartum psychosis suggests that in remitted patients, a proportion of them may be able to taper and discontinue treatment, then sustain well-being for protracted periods.

One obstacle with respect to treatment of postpartum psychosis derives from the short length of stay after delivery for many women. Some women who present with symptoms of postpartum psychosis in the first 24-48 hours frequently are managed with direct admission to an inpatient psychiatric service. But others may not develop symptoms until they are home, which may place both mother and newborn at risk.

Given that the risk for recurrent postpartum psychosis is so great (70%-90%), women with histories of postpartum psychosis invariably are prophylaxed with mood stabilizer prior to delivery in a subsequent pregnancy. In our own center, we have published on the value of such prophylactic intervention, not just in women with postpartum psychosis, but in women with bipolar disorder, who are, as noted, at great risk for developing postpartum psychotic symptoms (Am J Psychiatry. 1995 Nov;152[11]:1641-5.)

Although postpartum psychosis may be rare, over the last 3 decades we have seen a substantial number of women with postpartum psychosis and have been fascinated with the spectrum of symptoms with which some women with postpartum psychotic illness present. We also have been impressed with the time required for some women to recompensate from their illness and the course of their disorder after they have seemingly remitted. Some women appear to be able to discontinue treatment as noted above; others, particularly if there is any history of bipolar disorder, need to be maintained on treatment with mood stabilizer indefinitely.

To better understand the phenomenology of postpartum psychosis, as well as the longitudinal course of the illness, in 2019, the Mass General Hospital Postpartum Psychosis Project (MGHP3) was established. The project is conducted as a hospital-based registry where women with histories of postpartum psychosis over the last decade are invited to participate in an in-depth interview to understand both symptoms and course of underlying illness. This is complemented by obtaining a sample of saliva, which is used for genetic testing to try to identify a genetic underpinning associated with postpartum psychosis, as the question of genetic etiology of postpartum psychosis is still an open one.

As part of the MGHP3 project, clinicians across the country are able to contact perinatal psychiatrists in our center with expertise in the treatment of postpartum psychosis. Our psychiatrists also can counsel clinicians on issues regarding long-term management of postpartum psychosis because for many, knowledge of precisely how to manage this disorder or the follow-up treatment may be incomplete.

From a clinical point of view, the relevant questions really include not only acute treatment, which has already been outlined, but also the issue of duration of treatment. While some patients may be able to taper and discontinue treatment after, for example, a year of being totally well, to date we are unable to know who those patients are. We tend to be more conservative in our own center and treat patients with puerperal psychosis for a more protracted period of time, usually over several years. We also ask women about their family history of bipolar disorder or postpartum psychosis. Depending on the clinical course (if the patient really has sustained euthymia), we consider slow taper and ultimate discontinuation. As always, treatment decisions are tailored to individual clinical history, course, and patient wishes.

Postpartum psychosis remains one of the most serious illnesses that we find in reproductive psychiatry, and incomplete attention has been given to this devastating illness, which we read about periodically in newspapers and magazines. Greater understanding of postpartum psychosis will lead to a more precision-like psychiatric approach, tailoring treatment to the invariable heterogeneity of this illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Although the last decade has brought appropriate increased interest in the diagnosis and treatment of postpartum depression, with screening initiatives across more than 40 states in place and even new medications being brought to market for treatment, far less attention has been given to diagnosis and treatment of a particularly serious psychiatric illness: postpartum psychosis.

Clinically, women can experience rapid mood changes, most often with the presentation that is consistent with a manic-like psychosis, with associated symptoms of delusional thinking, hallucinations, paranoia and either depression or elation, or an amalgam of these so-called “mixed symptoms.” Onset of symptoms typically is early, within 72 hours as is classically described, but may have a somewhat later time of onset in some women.

Many investigators have studied risk factors for postpartum psychosis, and it has been well established that a history of mood disorder, particularly bipolar disorder, is one of the strongest predictors of risk for postpartum psychosis. Women with histories of postpartum psychosis are at very high risk of recurrence, with as many as 70%-90% of women experiencing recurrence if not prophylaxed with an appropriate agent. From a clinical point of view, women with postpartum psychosis typically are hospitalized, given that this is both a psychiatric and potential obstetrical emergency. In fact, the data would suggest that although postpartum suicide and infanticide are not common, they can be a tragic concomitant of postpartum psychosis (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Dec 1;173[12]:1179-88).

A great amount of interest has been placed on the etiology of postpartum psychosis, as it’s a dramatic presentation with very rapid onset in the acute postpartum period. A rich evidence base with respect to an algorithm of treatment that maximizes likelihood of full recovery or sustaining of euthymia after recovery is limited. Few studies have looked systematically at the optimum way to treat postpartum psychosis. Clinical wisdom has dictated that, given the dramatic symptoms with which these patients present, most patients are treated with lithium and an antipsychotic medication as if they have a manic-like psychosis. It may take brief or extended periods of time for patients to stabilize. Once they are stabilized, one of the most challenging questions for clinicians is how long to treat. Again, an evidence base clearly informing this question is lacking.

Over the years, many clinicians have treated patients with postpartum psychosis as if they have bipolar disorder, given the index presentation of the illness, so some of these patients are treated with antimanic drugs indefinitely. However, clinical experience from several centers that treat women with postpartum psychosis suggests that in remitted patients, a proportion of them may be able to taper and discontinue treatment, then sustain well-being for protracted periods.

One obstacle with respect to treatment of postpartum psychosis derives from the short length of stay after delivery for many women. Some women who present with symptoms of postpartum psychosis in the first 24-48 hours frequently are managed with direct admission to an inpatient psychiatric service. But others may not develop symptoms until they are home, which may place both mother and newborn at risk.

Given that the risk for recurrent postpartum psychosis is so great (70%-90%), women with histories of postpartum psychosis invariably are prophylaxed with mood stabilizer prior to delivery in a subsequent pregnancy. In our own center, we have published on the value of such prophylactic intervention, not just in women with postpartum psychosis, but in women with bipolar disorder, who are, as noted, at great risk for developing postpartum psychotic symptoms (Am J Psychiatry. 1995 Nov;152[11]:1641-5.)

Although postpartum psychosis may be rare, over the last 3 decades we have seen a substantial number of women with postpartum psychosis and have been fascinated with the spectrum of symptoms with which some women with postpartum psychotic illness present. We also have been impressed with the time required for some women to recompensate from their illness and the course of their disorder after they have seemingly remitted. Some women appear to be able to discontinue treatment as noted above; others, particularly if there is any history of bipolar disorder, need to be maintained on treatment with mood stabilizer indefinitely.

To better understand the phenomenology of postpartum psychosis, as well as the longitudinal course of the illness, in 2019, the Mass General Hospital Postpartum Psychosis Project (MGHP3) was established. The project is conducted as a hospital-based registry where women with histories of postpartum psychosis over the last decade are invited to participate in an in-depth interview to understand both symptoms and course of underlying illness. This is complemented by obtaining a sample of saliva, which is used for genetic testing to try to identify a genetic underpinning associated with postpartum psychosis, as the question of genetic etiology of postpartum psychosis is still an open one.

As part of the MGHP3 project, clinicians across the country are able to contact perinatal psychiatrists in our center with expertise in the treatment of postpartum psychosis. Our psychiatrists also can counsel clinicians on issues regarding long-term management of postpartum psychosis because for many, knowledge of precisely how to manage this disorder or the follow-up treatment may be incomplete.

From a clinical point of view, the relevant questions really include not only acute treatment, which has already been outlined, but also the issue of duration of treatment. While some patients may be able to taper and discontinue treatment after, for example, a year of being totally well, to date we are unable to know who those patients are. We tend to be more conservative in our own center and treat patients with puerperal psychosis for a more protracted period of time, usually over several years. We also ask women about their family history of bipolar disorder or postpartum psychosis. Depending on the clinical course (if the patient really has sustained euthymia), we consider slow taper and ultimate discontinuation. As always, treatment decisions are tailored to individual clinical history, course, and patient wishes.

Postpartum psychosis remains one of the most serious illnesses that we find in reproductive psychiatry, and incomplete attention has been given to this devastating illness, which we read about periodically in newspapers and magazines. Greater understanding of postpartum psychosis will lead to a more precision-like psychiatric approach, tailoring treatment to the invariable heterogeneity of this illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Docs weigh pulling out of MIPS over paltry payments

If you’ve knocked yourself out to earn a Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) bonus payment, it’s pretty safe to say that getting a 1.68% payment boost probably didn’t feel like a “win” that was worth the effort.

And although it saved you from having a negative 5% payment adjustment, many physicians don’t feel that it was worth the effort.

On Jan. 6, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced the 2020 payouts for MIPS.

Based on 2018 participation, the bonus for those who scored a perfect 100 is only a 1.68% boost in Medicare reimbursement, slightly lower than last year’s 1.88%. This decline comes as no surprise as the agency leader admits: “As the program matures, we expect that the increases in the performance thresholds in future program years will create a smaller distribution of positive payment adjustments.” Overall, more than 97% of participants avoided having a negative 5% payment adjustment.

Indeed, these bonus monies are based on a short-term appropriation of extra funds from Congress. After these temporary funds are no longer available, there will be little, if any, monies to distribute as the program is based on a “losers-feed-the-winners” construct.

It may be very tempting for many physicians to decide to ignore MIPS, with the rationale that 1.68% is not worth the effort. But don’t let your foot off the gas pedal yet, since the penalty for not participating in 2020 is a substantial 9%.

However, it is certainly time to reconsider efforts to participate at the highest level.

Should you or shouldn’t you bother with MIPS?

Let’s say you have $75,000 in revenue from Medicare Part B per year. Depending on the services you offer in your practice, that equates to 500-750 encounters with Medicare beneficiaries per year. (A reminder that MIPS affects only Part B; Medicare Advantage plans do not partake in the program.)

The recent announcement reveals that perfection would equate to an additional $1,260 per year. That’s only if you received the full 100 points; if you were simply an “exceptional performer,” the government will allot an additional $157. That’s less than you get paid for a single office visit.