User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

U.S. suicide rate in 2019 took first downturn in 14 years

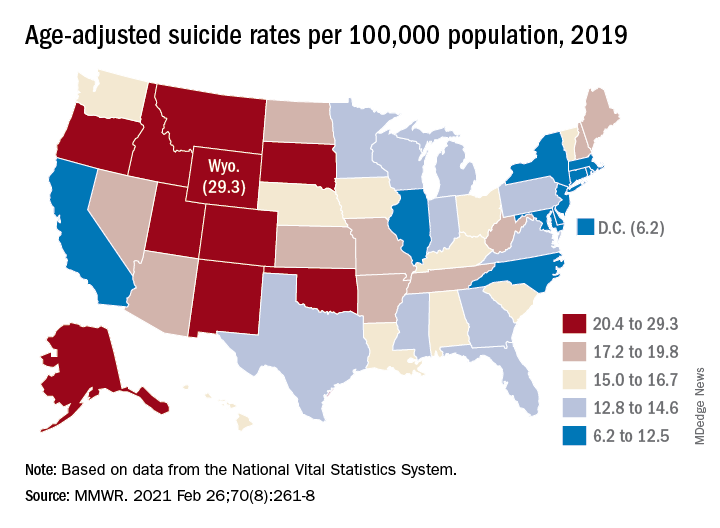

In 2019, the U.S. suicide rate dropped for the first time in 14 years, driven largely by a significant decline in firearm-related deaths, according to a new analysis of National Vital Statistics System data.

Since firearms are the “most common and most lethal” mechanism of suicide, the drop in deaths is “particularly encouraging,” Deborah M. Stone, ScD, MSW, MPH, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The national suicide rate decreased from 14.2 per 100,000 population in 2018 to 13.9 per 100,000 in 2019, a statistically significant drop of 2.1% that reversed a 20-year trend that saw the rate increase by 33% since 1999, they said.

The rate for firearm use, which is involved in half of all suicides, declined from 7.0 per 100,000 to 6.8, for a significant change of 2.9%, said Dr. Stone and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

The only other method with a drop in suicide rate from 2018 to 2019 was suffocation – the second most common mechanism of injury – but the relative change of 2.3% was not significant, they noted.

Significant declines also occurred in several subgroups: Whites; those aged 15-24, 55-64, and 65-74 years; and those living in counties classified as large fringe metropolitan or micropolitan (urban cluster of ≥ 10,000 but less than 50,000 population), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

the investigators wrote.

The states with significant increases were Hawaii (30.3%) and Nebraska (20.1%), while declines in the suicide rate were significant in five states – Idaho, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Virginia, Dr. Stone and associates reported. Altogether, the rate fell in 31 states, increased in 18, and did not change in 2.

The significance of those changes varied between males and females. Declines were significant for females in Indiana, Massachusetts, and Washington, and for males in Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and West Virginia. Minnesota was the only state with a significant increase among females, with Hawaii and Wyoming posting increases for males, they said.

As the response to the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the investigators pointed out, “prevention is more important than ever. Past research indicates that suicide rates remain stable or decline during infrastructure disruption (e.g., natural disasters), only to rise afterwards as the longer-term sequelae unfold in persons, families, and communities.”

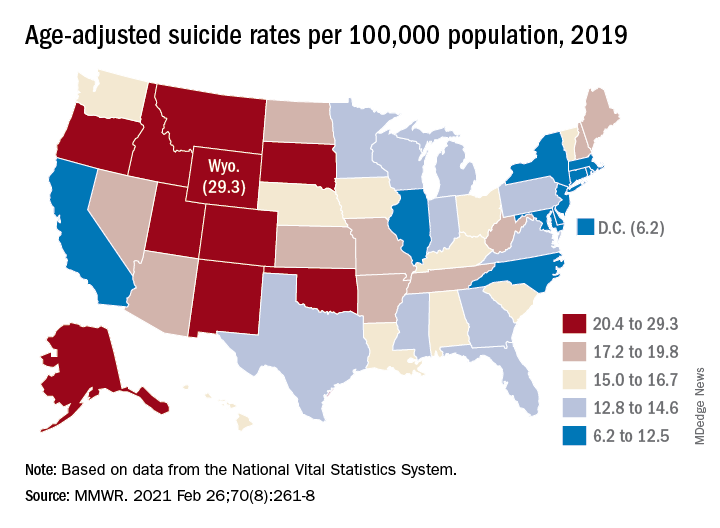

In 2019, the U.S. suicide rate dropped for the first time in 14 years, driven largely by a significant decline in firearm-related deaths, according to a new analysis of National Vital Statistics System data.

Since firearms are the “most common and most lethal” mechanism of suicide, the drop in deaths is “particularly encouraging,” Deborah M. Stone, ScD, MSW, MPH, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The national suicide rate decreased from 14.2 per 100,000 population in 2018 to 13.9 per 100,000 in 2019, a statistically significant drop of 2.1% that reversed a 20-year trend that saw the rate increase by 33% since 1999, they said.

The rate for firearm use, which is involved in half of all suicides, declined from 7.0 per 100,000 to 6.8, for a significant change of 2.9%, said Dr. Stone and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

The only other method with a drop in suicide rate from 2018 to 2019 was suffocation – the second most common mechanism of injury – but the relative change of 2.3% was not significant, they noted.

Significant declines also occurred in several subgroups: Whites; those aged 15-24, 55-64, and 65-74 years; and those living in counties classified as large fringe metropolitan or micropolitan (urban cluster of ≥ 10,000 but less than 50,000 population), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

the investigators wrote.

The states with significant increases were Hawaii (30.3%) and Nebraska (20.1%), while declines in the suicide rate were significant in five states – Idaho, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Virginia, Dr. Stone and associates reported. Altogether, the rate fell in 31 states, increased in 18, and did not change in 2.

The significance of those changes varied between males and females. Declines were significant for females in Indiana, Massachusetts, and Washington, and for males in Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and West Virginia. Minnesota was the only state with a significant increase among females, with Hawaii and Wyoming posting increases for males, they said.

As the response to the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the investigators pointed out, “prevention is more important than ever. Past research indicates that suicide rates remain stable or decline during infrastructure disruption (e.g., natural disasters), only to rise afterwards as the longer-term sequelae unfold in persons, families, and communities.”

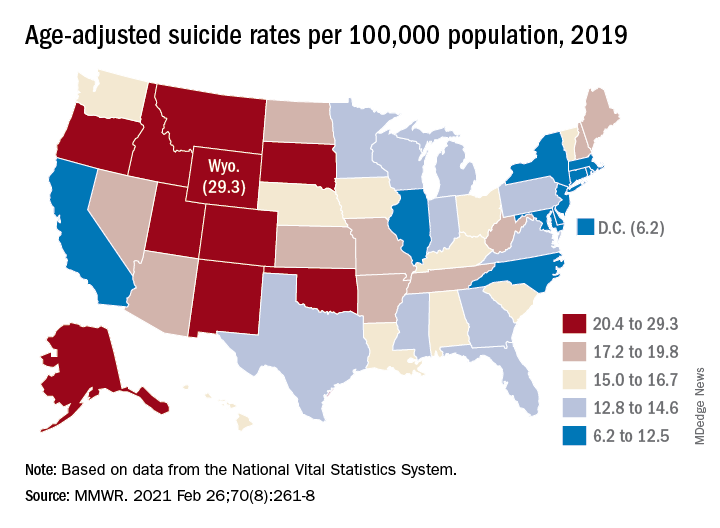

In 2019, the U.S. suicide rate dropped for the first time in 14 years, driven largely by a significant decline in firearm-related deaths, according to a new analysis of National Vital Statistics System data.

Since firearms are the “most common and most lethal” mechanism of suicide, the drop in deaths is “particularly encouraging,” Deborah M. Stone, ScD, MSW, MPH, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The national suicide rate decreased from 14.2 per 100,000 population in 2018 to 13.9 per 100,000 in 2019, a statistically significant drop of 2.1% that reversed a 20-year trend that saw the rate increase by 33% since 1999, they said.

The rate for firearm use, which is involved in half of all suicides, declined from 7.0 per 100,000 to 6.8, for a significant change of 2.9%, said Dr. Stone and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

The only other method with a drop in suicide rate from 2018 to 2019 was suffocation – the second most common mechanism of injury – but the relative change of 2.3% was not significant, they noted.

Significant declines also occurred in several subgroups: Whites; those aged 15-24, 55-64, and 65-74 years; and those living in counties classified as large fringe metropolitan or micropolitan (urban cluster of ≥ 10,000 but less than 50,000 population), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

the investigators wrote.

The states with significant increases were Hawaii (30.3%) and Nebraska (20.1%), while declines in the suicide rate were significant in five states – Idaho, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Virginia, Dr. Stone and associates reported. Altogether, the rate fell in 31 states, increased in 18, and did not change in 2.

The significance of those changes varied between males and females. Declines were significant for females in Indiana, Massachusetts, and Washington, and for males in Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and West Virginia. Minnesota was the only state with a significant increase among females, with Hawaii and Wyoming posting increases for males, they said.

As the response to the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the investigators pointed out, “prevention is more important than ever. Past research indicates that suicide rates remain stable or decline during infrastructure disruption (e.g., natural disasters), only to rise afterwards as the longer-term sequelae unfold in persons, families, and communities.”

FROM MMWR

Do antidepressants increase the risk of brain bleeds?

Contrary to previous findings, results of a large observational study show. However, at least one expert urged caution in interpreting the finding.

“These findings are important, especially since depression is common after stroke and SSRIs are some of the first drugs considered for people,” Mithilesh Siddu, MD, of the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital, also in Miami, said in a statement.

However, Dr. Siddu said “more research is needed to confirm our findings and to also examine if SSRIs prescribed after a stroke may be linked to risk of a second stroke.”

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Widely prescribed

SSRIs, the most widely prescribed antidepressant in the United States, have previously been linked to an increased risk of ICH, possibly as a result of impaired platelet function.

To investigate further, the researchers analyzed data from the Florida Stroke Registry (FSR). They identified 127,915 patients who suffered ICH from January 2010 to December 2019 and for whom information on antidepressant use was available.

They analyzed the proportion of cases presenting with ICH among antidepressant users and the rate of SSRI prescription among stroke patients discharged on antidepressant therapy.

The researchers found that 11% of those who had been prescribed antidepressants had an ICH, compared with 14% of those who had not.

Antidepressant users were more likely to be female; non-Hispanic White; have hypertension; have diabetes; and use oral anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and statins prior to hospital presentation for ICH.

In multivariable analyses adjusting for age, race, prior history of hypertension, diabetes and prior oral anticoagulant, antiplatelet and statin use, antidepressant users were just as likely to present with spontaneous ICH as nonantidepressant users (odds ratio, 0.92; 95% confidence interval, 0.85-1.01).

A total of 3.4% of all ICH patients and 9% of those in whom specific antidepressant information was available were discharged home on an antidepressant, most commonly an SSRI (74%).

The authors noted a key limitation of the study: Some details regarding the length, dosage, and type of antidepressants were not available.

Interpret with caution

In a comment, Shaheen Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist in Newton, Mass., and executive director of the Global Neuroscience Initiative Foundation, urged caution in making any firm conclusions based on this study.

“We have two questions here: One, is SSRI use a risk factor for first-time intracerebral hemorrhage, and two, is SSRI use after an ICH a risk factor for additional hemorrhages,” said Dr. Lakhan, who was not involved with the study.

“This study incompletely addresses the first because it is known that SSRIs have a variety of potencies. For instance, paroxetine is a strong inhibitor of serotonin reuptake, whereas bupropion is weak. Hypothetically, the former has a greater risk of ICH. Because this study did not stratify by type of antidepressant, it is not possible to tease these out,” Dr. Lakhan said.

“The second question is completely unaddressed by this study and is the real concern in clinical practice, because the chance of rebleed is much higher than the risk of first-time ICH in the general population,” he added.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Siddu and Dr. Lakhan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Contrary to previous findings, results of a large observational study show. However, at least one expert urged caution in interpreting the finding.

“These findings are important, especially since depression is common after stroke and SSRIs are some of the first drugs considered for people,” Mithilesh Siddu, MD, of the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital, also in Miami, said in a statement.

However, Dr. Siddu said “more research is needed to confirm our findings and to also examine if SSRIs prescribed after a stroke may be linked to risk of a second stroke.”

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Widely prescribed

SSRIs, the most widely prescribed antidepressant in the United States, have previously been linked to an increased risk of ICH, possibly as a result of impaired platelet function.

To investigate further, the researchers analyzed data from the Florida Stroke Registry (FSR). They identified 127,915 patients who suffered ICH from January 2010 to December 2019 and for whom information on antidepressant use was available.

They analyzed the proportion of cases presenting with ICH among antidepressant users and the rate of SSRI prescription among stroke patients discharged on antidepressant therapy.

The researchers found that 11% of those who had been prescribed antidepressants had an ICH, compared with 14% of those who had not.

Antidepressant users were more likely to be female; non-Hispanic White; have hypertension; have diabetes; and use oral anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and statins prior to hospital presentation for ICH.

In multivariable analyses adjusting for age, race, prior history of hypertension, diabetes and prior oral anticoagulant, antiplatelet and statin use, antidepressant users were just as likely to present with spontaneous ICH as nonantidepressant users (odds ratio, 0.92; 95% confidence interval, 0.85-1.01).

A total of 3.4% of all ICH patients and 9% of those in whom specific antidepressant information was available were discharged home on an antidepressant, most commonly an SSRI (74%).

The authors noted a key limitation of the study: Some details regarding the length, dosage, and type of antidepressants were not available.

Interpret with caution

In a comment, Shaheen Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist in Newton, Mass., and executive director of the Global Neuroscience Initiative Foundation, urged caution in making any firm conclusions based on this study.

“We have two questions here: One, is SSRI use a risk factor for first-time intracerebral hemorrhage, and two, is SSRI use after an ICH a risk factor for additional hemorrhages,” said Dr. Lakhan, who was not involved with the study.

“This study incompletely addresses the first because it is known that SSRIs have a variety of potencies. For instance, paroxetine is a strong inhibitor of serotonin reuptake, whereas bupropion is weak. Hypothetically, the former has a greater risk of ICH. Because this study did not stratify by type of antidepressant, it is not possible to tease these out,” Dr. Lakhan said.

“The second question is completely unaddressed by this study and is the real concern in clinical practice, because the chance of rebleed is much higher than the risk of first-time ICH in the general population,” he added.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Siddu and Dr. Lakhan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Contrary to previous findings, results of a large observational study show. However, at least one expert urged caution in interpreting the finding.

“These findings are important, especially since depression is common after stroke and SSRIs are some of the first drugs considered for people,” Mithilesh Siddu, MD, of the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital, also in Miami, said in a statement.

However, Dr. Siddu said “more research is needed to confirm our findings and to also examine if SSRIs prescribed after a stroke may be linked to risk of a second stroke.”

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Widely prescribed

SSRIs, the most widely prescribed antidepressant in the United States, have previously been linked to an increased risk of ICH, possibly as a result of impaired platelet function.

To investigate further, the researchers analyzed data from the Florida Stroke Registry (FSR). They identified 127,915 patients who suffered ICH from January 2010 to December 2019 and for whom information on antidepressant use was available.

They analyzed the proportion of cases presenting with ICH among antidepressant users and the rate of SSRI prescription among stroke patients discharged on antidepressant therapy.

The researchers found that 11% of those who had been prescribed antidepressants had an ICH, compared with 14% of those who had not.

Antidepressant users were more likely to be female; non-Hispanic White; have hypertension; have diabetes; and use oral anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and statins prior to hospital presentation for ICH.

In multivariable analyses adjusting for age, race, prior history of hypertension, diabetes and prior oral anticoagulant, antiplatelet and statin use, antidepressant users were just as likely to present with spontaneous ICH as nonantidepressant users (odds ratio, 0.92; 95% confidence interval, 0.85-1.01).

A total of 3.4% of all ICH patients and 9% of those in whom specific antidepressant information was available were discharged home on an antidepressant, most commonly an SSRI (74%).

The authors noted a key limitation of the study: Some details regarding the length, dosage, and type of antidepressants were not available.

Interpret with caution

In a comment, Shaheen Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist in Newton, Mass., and executive director of the Global Neuroscience Initiative Foundation, urged caution in making any firm conclusions based on this study.

“We have two questions here: One, is SSRI use a risk factor for first-time intracerebral hemorrhage, and two, is SSRI use after an ICH a risk factor for additional hemorrhages,” said Dr. Lakhan, who was not involved with the study.

“This study incompletely addresses the first because it is known that SSRIs have a variety of potencies. For instance, paroxetine is a strong inhibitor of serotonin reuptake, whereas bupropion is weak. Hypothetically, the former has a greater risk of ICH. Because this study did not stratify by type of antidepressant, it is not possible to tease these out,” Dr. Lakhan said.

“The second question is completely unaddressed by this study and is the real concern in clinical practice, because the chance of rebleed is much higher than the risk of first-time ICH in the general population,” he added.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Siddu and Dr. Lakhan disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAN 2021

Docs become dog groomers and warehouse workers after COVID-19 work loss

One of the biggest conundrums of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the simultaneous panic-hiring of medical professionals in hot spots and significant downsizing of staff across the country. From huge hospital systems to private practices, the stoppage of breast reductions and knee replacements, not to mention the drops in motor vehicle accidents and bar fights, have quieted operating rooms and emergency departments and put doctors’ jobs on the chopping block. A widely cited survey suggests that 21% of doctors have had a work reduction due to COVID-19.

For many American doctors, this is their first extended period of unemployment. Unlike engineers or those with MBAs who might see their fortunes rise and fall with the whims of recessions and boom times, physicians are not exactly accustomed to being laid off. However, doctors were already smarting for years due to falling salaries and decreased autonomy, punctuated by endless clicks on electronic medical records software.

Stephanie Eschenbach Morgan, MD, a breast radiologist in North Carolina, trained for 10 years after college before earning a true physician’s salary.

“Being furloughed was awful. Initially, it was only going to be 2 weeks, and then it turned into 2 months with no pay,” she reflected.

Dr. Eschenbach Morgan and her surgeon husband, who lost a full quarter’s salary, had to ask for grace periods on their credit card and mortgage payments because they had paid a large tax bill right before the pandemic began. “We couldn’t get any stimulus help, so that added insult to injury,” she said.

With her time spent waiting in a holding pattern, Dr. Eschenbach Morgan homeschooled her two young children and started putting a home gym together. She went on a home organizing spree, started a garden, and, perhaps most impressively, caught up with 5 years of photo albums.

A bonus she noted: “I didn’t set an alarm for 2 months.”

Shella Farooki, MD, a radiologist in California, was also focused on homeschooling, itself a demanding job, and veered toward retirement. When one of her work contracts furloughed her (“at one point, I made $30K a month for [their business]”), she started saving money at home, teaching the kids, and applied for a Paycheck Protection Program loan. Her husband, a hospitalist, had had his shifts cut. Dr. Farooki tried a radiology artificial intelligence firm but backed out when she was asked to read 9,200 studies for them for $2,000 per month.

Now, she thinks about leaving medicine “every day.”

Some doctors are questioning whether they should be in medicine in the first place. Family medicine physician Jonathan Polak, MD, faced with his own pink slip, turned to pink T-shirts instead. His girlfriend manages an outlet of the teen fashion retailer Justice. Dr. Polak, who finished his residency just 2 years ago, didn’t hesitate to take a $10-an-hour gig as a stock doc, once even finding himself delivering a shelving unit from the shuttering store to a physician fleeing the city for rural New Hampshire to “escape.”

There’s no escape for him – yet. Saddled with “astronomical” student loans, he had considered grocery store work as well. Dr. Polak knows he can’t work part time or go into teaching long term, as he might like.

Even so, he’s doing everything he can to not be in patient care for the long haul – it’s just not what he thought it would be.

“The culture of medicine, bureaucracy, endless paperwork and charting, and threat of litigation sucks a lot of the joy out of it to the point that I don’t see myself doing it forever when imagining myself 5-10 years into it.”

Still, he recently took an 18-month hospital contract that will force him to move to Florida, but he’s also been turning himself into a veritable Renaissance man; composing music, training for an ultramarathon, studying the latest medical findings, roadtripping, and launching a podcast about dog grooming with a master groomer. “We found parallels between medicine and dog grooming,” he says, somewhat convincingly.

Also working the ruff life is Jen Tserng, MD, a former forensic pathologist who landed on news websites in recent years for becoming a professional dogwalker and housesitter without a permanent home. Dr. Tserng knows doctors were restless and unhappy before COVID-19, their thoughts wandering where the grass might be greener.

As her profile grew, she found her inbox gathering messages from disaffected medical minions: students with a fear of failing or staring down residency application season and employed doctors sick of the constant grind. As she recounted those de facto life coach conversations (“What do you really enjoy?” “Do you really like dogs?”) by phone from New York, she said matter-of-factly, “They don’t call because of COVID. They call because they hate their lives.”

Michelle Mudge-Riley, MD, a physician in Texas, has been seeing this shift for some time as well. She recently held a virtual version of her Physicians Helping Physicians conference, where doctors hear from their peers working successfully in fields like pharmaceuticals and real estate investing.

When COVID-19 hit, Dr. Mudge-Riley quickly pivoted to a virtual platform, where the MDs and DOs huddled in breakout rooms having honest chats about their fears and tentative hopes about their new careers.

“There has been increased interest in nonclinical exploration into full- and part-time careers, as well as side hustles, since COVID began,” she said. “Many physicians have had their hours or pay cut, and some have been laid off. Others are furloughed. Some just want out of an environment where they don’t feel safe.”

An ear, nose, and throat surgeon, Maansi Doshi, MD, from central California, didn’t feel safe – so she left. She had returned from India sick with a mystery virus right as the pandemic began (she said her COVID-19 tests were all negative) and was waiting to get well enough to go back to her private practice job. However, she said she clashed with Trump-supporting colleagues she feared might not be taking the pandemic seriously enough.

Finally getting over a relapse of her mystery virus, Dr. Doshi emailed her resignation in May. Her husband, family practice doctor Mark Mangiapane, MD, gave his job notice weeks later in solidarity because he worked in the same building. Together, they have embraced gardening, a Peloton splurge, and learning business skills to open private practices – solo primary care for him; ENT with a focus on her favorite surgery, rhinoplasty, for her.

Dr. Mangiapane had considered editing medical brochures and also tried to apply for a job as a county public health officer in rural California, but he received his own shock when he learned the county intended to open schools in the midst of the pandemic despite advisement to the contrary by the former health officer.

He retreated from job listings altogether after hearing his would-be peers were getting death threats – targeting their children.

Both doctors felt COVID-19 pushed them beyond their comfort zones. “If COVID hadn’t happened, I would be working. ... Be ‘owned.’ In a weird way, COVID made me more independent and take a risk with my career.”

Obstetrician Kwandaa Roberts, MD, certainly did; she took a budding interest in decorating dollhouses straight to Instagram and national news fame, and she is now a TV-show expert on “Sell This House.”

Like Dr. Doshi and Dr. Mangiapane, Dr. Polak wants to be more in control of his future – even if selling T-shirts at a mall means a certain loss of status along the way.

“Aside from my passion to learn and to have that connection with people, I went into medicine ... because of the job security I thought existed,” he said. “I would say that my getting furloughed has changed my view of the United States in a dramatic way. I do not feel as confident in the U.S. economy and general way of life as I did a year ago. And I am taking a number of steps to put myself in a more fluid, adaptable position in case another crisis like this occurs or if the current state of things worsens.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the biggest conundrums of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the simultaneous panic-hiring of medical professionals in hot spots and significant downsizing of staff across the country. From huge hospital systems to private practices, the stoppage of breast reductions and knee replacements, not to mention the drops in motor vehicle accidents and bar fights, have quieted operating rooms and emergency departments and put doctors’ jobs on the chopping block. A widely cited survey suggests that 21% of doctors have had a work reduction due to COVID-19.

For many American doctors, this is their first extended period of unemployment. Unlike engineers or those with MBAs who might see their fortunes rise and fall with the whims of recessions and boom times, physicians are not exactly accustomed to being laid off. However, doctors were already smarting for years due to falling salaries and decreased autonomy, punctuated by endless clicks on electronic medical records software.

Stephanie Eschenbach Morgan, MD, a breast radiologist in North Carolina, trained for 10 years after college before earning a true physician’s salary.

“Being furloughed was awful. Initially, it was only going to be 2 weeks, and then it turned into 2 months with no pay,” she reflected.

Dr. Eschenbach Morgan and her surgeon husband, who lost a full quarter’s salary, had to ask for grace periods on their credit card and mortgage payments because they had paid a large tax bill right before the pandemic began. “We couldn’t get any stimulus help, so that added insult to injury,” she said.

With her time spent waiting in a holding pattern, Dr. Eschenbach Morgan homeschooled her two young children and started putting a home gym together. She went on a home organizing spree, started a garden, and, perhaps most impressively, caught up with 5 years of photo albums.

A bonus she noted: “I didn’t set an alarm for 2 months.”

Shella Farooki, MD, a radiologist in California, was also focused on homeschooling, itself a demanding job, and veered toward retirement. When one of her work contracts furloughed her (“at one point, I made $30K a month for [their business]”), she started saving money at home, teaching the kids, and applied for a Paycheck Protection Program loan. Her husband, a hospitalist, had had his shifts cut. Dr. Farooki tried a radiology artificial intelligence firm but backed out when she was asked to read 9,200 studies for them for $2,000 per month.

Now, she thinks about leaving medicine “every day.”

Some doctors are questioning whether they should be in medicine in the first place. Family medicine physician Jonathan Polak, MD, faced with his own pink slip, turned to pink T-shirts instead. His girlfriend manages an outlet of the teen fashion retailer Justice. Dr. Polak, who finished his residency just 2 years ago, didn’t hesitate to take a $10-an-hour gig as a stock doc, once even finding himself delivering a shelving unit from the shuttering store to a physician fleeing the city for rural New Hampshire to “escape.”

There’s no escape for him – yet. Saddled with “astronomical” student loans, he had considered grocery store work as well. Dr. Polak knows he can’t work part time or go into teaching long term, as he might like.

Even so, he’s doing everything he can to not be in patient care for the long haul – it’s just not what he thought it would be.

“The culture of medicine, bureaucracy, endless paperwork and charting, and threat of litigation sucks a lot of the joy out of it to the point that I don’t see myself doing it forever when imagining myself 5-10 years into it.”

Still, he recently took an 18-month hospital contract that will force him to move to Florida, but he’s also been turning himself into a veritable Renaissance man; composing music, training for an ultramarathon, studying the latest medical findings, roadtripping, and launching a podcast about dog grooming with a master groomer. “We found parallels between medicine and dog grooming,” he says, somewhat convincingly.

Also working the ruff life is Jen Tserng, MD, a former forensic pathologist who landed on news websites in recent years for becoming a professional dogwalker and housesitter without a permanent home. Dr. Tserng knows doctors were restless and unhappy before COVID-19, their thoughts wandering where the grass might be greener.

As her profile grew, she found her inbox gathering messages from disaffected medical minions: students with a fear of failing or staring down residency application season and employed doctors sick of the constant grind. As she recounted those de facto life coach conversations (“What do you really enjoy?” “Do you really like dogs?”) by phone from New York, she said matter-of-factly, “They don’t call because of COVID. They call because they hate their lives.”

Michelle Mudge-Riley, MD, a physician in Texas, has been seeing this shift for some time as well. She recently held a virtual version of her Physicians Helping Physicians conference, where doctors hear from their peers working successfully in fields like pharmaceuticals and real estate investing.

When COVID-19 hit, Dr. Mudge-Riley quickly pivoted to a virtual platform, where the MDs and DOs huddled in breakout rooms having honest chats about their fears and tentative hopes about their new careers.

“There has been increased interest in nonclinical exploration into full- and part-time careers, as well as side hustles, since COVID began,” she said. “Many physicians have had their hours or pay cut, and some have been laid off. Others are furloughed. Some just want out of an environment where they don’t feel safe.”

An ear, nose, and throat surgeon, Maansi Doshi, MD, from central California, didn’t feel safe – so she left. She had returned from India sick with a mystery virus right as the pandemic began (she said her COVID-19 tests were all negative) and was waiting to get well enough to go back to her private practice job. However, she said she clashed with Trump-supporting colleagues she feared might not be taking the pandemic seriously enough.

Finally getting over a relapse of her mystery virus, Dr. Doshi emailed her resignation in May. Her husband, family practice doctor Mark Mangiapane, MD, gave his job notice weeks later in solidarity because he worked in the same building. Together, they have embraced gardening, a Peloton splurge, and learning business skills to open private practices – solo primary care for him; ENT with a focus on her favorite surgery, rhinoplasty, for her.

Dr. Mangiapane had considered editing medical brochures and also tried to apply for a job as a county public health officer in rural California, but he received his own shock when he learned the county intended to open schools in the midst of the pandemic despite advisement to the contrary by the former health officer.

He retreated from job listings altogether after hearing his would-be peers were getting death threats – targeting their children.

Both doctors felt COVID-19 pushed them beyond their comfort zones. “If COVID hadn’t happened, I would be working. ... Be ‘owned.’ In a weird way, COVID made me more independent and take a risk with my career.”

Obstetrician Kwandaa Roberts, MD, certainly did; she took a budding interest in decorating dollhouses straight to Instagram and national news fame, and she is now a TV-show expert on “Sell This House.”

Like Dr. Doshi and Dr. Mangiapane, Dr. Polak wants to be more in control of his future – even if selling T-shirts at a mall means a certain loss of status along the way.

“Aside from my passion to learn and to have that connection with people, I went into medicine ... because of the job security I thought existed,” he said. “I would say that my getting furloughed has changed my view of the United States in a dramatic way. I do not feel as confident in the U.S. economy and general way of life as I did a year ago. And I am taking a number of steps to put myself in a more fluid, adaptable position in case another crisis like this occurs or if the current state of things worsens.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the biggest conundrums of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the simultaneous panic-hiring of medical professionals in hot spots and significant downsizing of staff across the country. From huge hospital systems to private practices, the stoppage of breast reductions and knee replacements, not to mention the drops in motor vehicle accidents and bar fights, have quieted operating rooms and emergency departments and put doctors’ jobs on the chopping block. A widely cited survey suggests that 21% of doctors have had a work reduction due to COVID-19.

For many American doctors, this is their first extended period of unemployment. Unlike engineers or those with MBAs who might see their fortunes rise and fall with the whims of recessions and boom times, physicians are not exactly accustomed to being laid off. However, doctors were already smarting for years due to falling salaries and decreased autonomy, punctuated by endless clicks on electronic medical records software.

Stephanie Eschenbach Morgan, MD, a breast radiologist in North Carolina, trained for 10 years after college before earning a true physician’s salary.

“Being furloughed was awful. Initially, it was only going to be 2 weeks, and then it turned into 2 months with no pay,” she reflected.

Dr. Eschenbach Morgan and her surgeon husband, who lost a full quarter’s salary, had to ask for grace periods on their credit card and mortgage payments because they had paid a large tax bill right before the pandemic began. “We couldn’t get any stimulus help, so that added insult to injury,” she said.

With her time spent waiting in a holding pattern, Dr. Eschenbach Morgan homeschooled her two young children and started putting a home gym together. She went on a home organizing spree, started a garden, and, perhaps most impressively, caught up with 5 years of photo albums.

A bonus she noted: “I didn’t set an alarm for 2 months.”

Shella Farooki, MD, a radiologist in California, was also focused on homeschooling, itself a demanding job, and veered toward retirement. When one of her work contracts furloughed her (“at one point, I made $30K a month for [their business]”), she started saving money at home, teaching the kids, and applied for a Paycheck Protection Program loan. Her husband, a hospitalist, had had his shifts cut. Dr. Farooki tried a radiology artificial intelligence firm but backed out when she was asked to read 9,200 studies for them for $2,000 per month.

Now, she thinks about leaving medicine “every day.”

Some doctors are questioning whether they should be in medicine in the first place. Family medicine physician Jonathan Polak, MD, faced with his own pink slip, turned to pink T-shirts instead. His girlfriend manages an outlet of the teen fashion retailer Justice. Dr. Polak, who finished his residency just 2 years ago, didn’t hesitate to take a $10-an-hour gig as a stock doc, once even finding himself delivering a shelving unit from the shuttering store to a physician fleeing the city for rural New Hampshire to “escape.”

There’s no escape for him – yet. Saddled with “astronomical” student loans, he had considered grocery store work as well. Dr. Polak knows he can’t work part time or go into teaching long term, as he might like.

Even so, he’s doing everything he can to not be in patient care for the long haul – it’s just not what he thought it would be.

“The culture of medicine, bureaucracy, endless paperwork and charting, and threat of litigation sucks a lot of the joy out of it to the point that I don’t see myself doing it forever when imagining myself 5-10 years into it.”

Still, he recently took an 18-month hospital contract that will force him to move to Florida, but he’s also been turning himself into a veritable Renaissance man; composing music, training for an ultramarathon, studying the latest medical findings, roadtripping, and launching a podcast about dog grooming with a master groomer. “We found parallels between medicine and dog grooming,” he says, somewhat convincingly.

Also working the ruff life is Jen Tserng, MD, a former forensic pathologist who landed on news websites in recent years for becoming a professional dogwalker and housesitter without a permanent home. Dr. Tserng knows doctors were restless and unhappy before COVID-19, their thoughts wandering where the grass might be greener.

As her profile grew, she found her inbox gathering messages from disaffected medical minions: students with a fear of failing or staring down residency application season and employed doctors sick of the constant grind. As she recounted those de facto life coach conversations (“What do you really enjoy?” “Do you really like dogs?”) by phone from New York, she said matter-of-factly, “They don’t call because of COVID. They call because they hate their lives.”

Michelle Mudge-Riley, MD, a physician in Texas, has been seeing this shift for some time as well. She recently held a virtual version of her Physicians Helping Physicians conference, where doctors hear from their peers working successfully in fields like pharmaceuticals and real estate investing.

When COVID-19 hit, Dr. Mudge-Riley quickly pivoted to a virtual platform, where the MDs and DOs huddled in breakout rooms having honest chats about their fears and tentative hopes about their new careers.

“There has been increased interest in nonclinical exploration into full- and part-time careers, as well as side hustles, since COVID began,” she said. “Many physicians have had their hours or pay cut, and some have been laid off. Others are furloughed. Some just want out of an environment where they don’t feel safe.”

An ear, nose, and throat surgeon, Maansi Doshi, MD, from central California, didn’t feel safe – so she left. She had returned from India sick with a mystery virus right as the pandemic began (she said her COVID-19 tests were all negative) and was waiting to get well enough to go back to her private practice job. However, she said she clashed with Trump-supporting colleagues she feared might not be taking the pandemic seriously enough.

Finally getting over a relapse of her mystery virus, Dr. Doshi emailed her resignation in May. Her husband, family practice doctor Mark Mangiapane, MD, gave his job notice weeks later in solidarity because he worked in the same building. Together, they have embraced gardening, a Peloton splurge, and learning business skills to open private practices – solo primary care for him; ENT with a focus on her favorite surgery, rhinoplasty, for her.

Dr. Mangiapane had considered editing medical brochures and also tried to apply for a job as a county public health officer in rural California, but he received his own shock when he learned the county intended to open schools in the midst of the pandemic despite advisement to the contrary by the former health officer.

He retreated from job listings altogether after hearing his would-be peers were getting death threats – targeting their children.

Both doctors felt COVID-19 pushed them beyond their comfort zones. “If COVID hadn’t happened, I would be working. ... Be ‘owned.’ In a weird way, COVID made me more independent and take a risk with my career.”

Obstetrician Kwandaa Roberts, MD, certainly did; she took a budding interest in decorating dollhouses straight to Instagram and national news fame, and she is now a TV-show expert on “Sell This House.”

Like Dr. Doshi and Dr. Mangiapane, Dr. Polak wants to be more in control of his future – even if selling T-shirts at a mall means a certain loss of status along the way.

“Aside from my passion to learn and to have that connection with people, I went into medicine ... because of the job security I thought existed,” he said. “I would say that my getting furloughed has changed my view of the United States in a dramatic way. I do not feel as confident in the U.S. economy and general way of life as I did a year ago. And I am taking a number of steps to put myself in a more fluid, adaptable position in case another crisis like this occurs or if the current state of things worsens.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Physician Support Line: One psychiatrist strives to make a difference

Have you ever had a really good idea about how to improve the delivery of mental health services? An idea that would help people, but that would require passion, innovation, and hard work to implement, and one that immediately is beset with a list of reasons why it can not be implemented?

Mona Masood, DO, had an idea. The Pennsylvania psychiatrist was asked to help moderate a Facebook group started by one of her infectious disease colleagues last winter – a private Facebook group for physicians working with COVID-19 patients.

“The group was getting posts from frontline workers about how depressed and hopeless they were feeling.” Dr. Masood said. “People were posting about how they were having escape fantasies and how they regretted becoming physicians. It became clear that there was a need for more support.”

psychiatrist volunteers would take calls from physicians who needed someone to talk to – the psychiatrist would provide a sympathetic ear and have a list of resources, but this would be support, not treatment. There would be no prescriptions, no treatment relationship, no reporting to licensing boards or employers. The calls would be anonymous.

She posted her idea on the Facebook group, and the response was immediate. “There were a lot of emails – 200 psychiatrists responded saying: “Sign me up.” A Zoom meeting was set up, and the process was set in motion.

Dr. Masood used a Google document for weekly sign-ups so the volunteer psychiatrists could choose times. “We had to pay for an upgraded Google suite package for that many users. Getting this up and running was like the saying about building a plane as you fly it,” Dr. Masood said. “It forced so much so quickly because there was this acknowledgment that the need was there.”

Initially, the support line launched with a telehealth platform, but there was a problem. “Many doctors don’t want to be seen; they worry about being recognized.” Dr. Masood researched hotline phone services and was able to get one for a reduced fee. The volunteers have an App on their smartphones that enables them to log in at the start of their shifts and log out at the end. In addition to the logistics of coordinating the volunteers – now numbering over 700 – the group found a health care law firm that provided pro bono services to review the policies and procedures.

Now that the support line is running, Dr. Masood is able to set up the day’s volunteers for the support line connection in a few minutes each morning, but the beginning was not easy. Her private practice transitioned to telemedicine, and her two children were home with one in virtual school. “At first, it was like another full-time job.” She still remains available for trouble-shooting during the day. It’s a project she has taken on with passion.

The support line began as a response to watching colleagues struggle with COVID. Since it launched, there have been approximately 2,000 calls. Calls typically last for 20 to 90 minutes, and no one has called with a suicidal crisis. It is now open to doctors and medical students looking for support for any reason. “Physicians call with all kinds of issues. In the first 3 months, it was COVID, but then they called with other concerns – there were doctors who called with election anxiety, really anything that affects the general public also affects us.”

The group has also offered Saturday didactic sessions for volunteers and weekly debriefing sessions. Dr. Masood has been approached by Vibrant Emotional Health, the administrator of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, about resources to help with funding – until now, this endeavor has had no financing – and she is hopeful that their financial support will allow the support line to sustain itself and grow. Future directions include advocating for systemic change in how physician mental health and wellness issues are addressed.

The Physician Support Line was one psychiatrist’s vision for how to address a problem. Like so many things related to this pandemic, it happened quickly and with surprising efficiency. Implementing this service, however, was not easy – it required hard work, innovative thinking, and passion. Those looking for someone to listen can call 1-888-409-0141 and psychiatrists who wish to volunteer can sign up at physiciansupportline.com/volunteer-info.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore.

Have you ever had a really good idea about how to improve the delivery of mental health services? An idea that would help people, but that would require passion, innovation, and hard work to implement, and one that immediately is beset with a list of reasons why it can not be implemented?

Mona Masood, DO, had an idea. The Pennsylvania psychiatrist was asked to help moderate a Facebook group started by one of her infectious disease colleagues last winter – a private Facebook group for physicians working with COVID-19 patients.

“The group was getting posts from frontline workers about how depressed and hopeless they were feeling.” Dr. Masood said. “People were posting about how they were having escape fantasies and how they regretted becoming physicians. It became clear that there was a need for more support.”

psychiatrist volunteers would take calls from physicians who needed someone to talk to – the psychiatrist would provide a sympathetic ear and have a list of resources, but this would be support, not treatment. There would be no prescriptions, no treatment relationship, no reporting to licensing boards or employers. The calls would be anonymous.

She posted her idea on the Facebook group, and the response was immediate. “There were a lot of emails – 200 psychiatrists responded saying: “Sign me up.” A Zoom meeting was set up, and the process was set in motion.

Dr. Masood used a Google document for weekly sign-ups so the volunteer psychiatrists could choose times. “We had to pay for an upgraded Google suite package for that many users. Getting this up and running was like the saying about building a plane as you fly it,” Dr. Masood said. “It forced so much so quickly because there was this acknowledgment that the need was there.”

Initially, the support line launched with a telehealth platform, but there was a problem. “Many doctors don’t want to be seen; they worry about being recognized.” Dr. Masood researched hotline phone services and was able to get one for a reduced fee. The volunteers have an App on their smartphones that enables them to log in at the start of their shifts and log out at the end. In addition to the logistics of coordinating the volunteers – now numbering over 700 – the group found a health care law firm that provided pro bono services to review the policies and procedures.

Now that the support line is running, Dr. Masood is able to set up the day’s volunteers for the support line connection in a few minutes each morning, but the beginning was not easy. Her private practice transitioned to telemedicine, and her two children were home with one in virtual school. “At first, it was like another full-time job.” She still remains available for trouble-shooting during the day. It’s a project she has taken on with passion.

The support line began as a response to watching colleagues struggle with COVID. Since it launched, there have been approximately 2,000 calls. Calls typically last for 20 to 90 minutes, and no one has called with a suicidal crisis. It is now open to doctors and medical students looking for support for any reason. “Physicians call with all kinds of issues. In the first 3 months, it was COVID, but then they called with other concerns – there were doctors who called with election anxiety, really anything that affects the general public also affects us.”

The group has also offered Saturday didactic sessions for volunteers and weekly debriefing sessions. Dr. Masood has been approached by Vibrant Emotional Health, the administrator of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, about resources to help with funding – until now, this endeavor has had no financing – and she is hopeful that their financial support will allow the support line to sustain itself and grow. Future directions include advocating for systemic change in how physician mental health and wellness issues are addressed.

The Physician Support Line was one psychiatrist’s vision for how to address a problem. Like so many things related to this pandemic, it happened quickly and with surprising efficiency. Implementing this service, however, was not easy – it required hard work, innovative thinking, and passion. Those looking for someone to listen can call 1-888-409-0141 and psychiatrists who wish to volunteer can sign up at physiciansupportline.com/volunteer-info.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore.

Have you ever had a really good idea about how to improve the delivery of mental health services? An idea that would help people, but that would require passion, innovation, and hard work to implement, and one that immediately is beset with a list of reasons why it can not be implemented?

Mona Masood, DO, had an idea. The Pennsylvania psychiatrist was asked to help moderate a Facebook group started by one of her infectious disease colleagues last winter – a private Facebook group for physicians working with COVID-19 patients.

“The group was getting posts from frontline workers about how depressed and hopeless they were feeling.” Dr. Masood said. “People were posting about how they were having escape fantasies and how they regretted becoming physicians. It became clear that there was a need for more support.”

psychiatrist volunteers would take calls from physicians who needed someone to talk to – the psychiatrist would provide a sympathetic ear and have a list of resources, but this would be support, not treatment. There would be no prescriptions, no treatment relationship, no reporting to licensing boards or employers. The calls would be anonymous.

She posted her idea on the Facebook group, and the response was immediate. “There were a lot of emails – 200 psychiatrists responded saying: “Sign me up.” A Zoom meeting was set up, and the process was set in motion.

Dr. Masood used a Google document for weekly sign-ups so the volunteer psychiatrists could choose times. “We had to pay for an upgraded Google suite package for that many users. Getting this up and running was like the saying about building a plane as you fly it,” Dr. Masood said. “It forced so much so quickly because there was this acknowledgment that the need was there.”

Initially, the support line launched with a telehealth platform, but there was a problem. “Many doctors don’t want to be seen; they worry about being recognized.” Dr. Masood researched hotline phone services and was able to get one for a reduced fee. The volunteers have an App on their smartphones that enables them to log in at the start of their shifts and log out at the end. In addition to the logistics of coordinating the volunteers – now numbering over 700 – the group found a health care law firm that provided pro bono services to review the policies and procedures.

Now that the support line is running, Dr. Masood is able to set up the day’s volunteers for the support line connection in a few minutes each morning, but the beginning was not easy. Her private practice transitioned to telemedicine, and her two children were home with one in virtual school. “At first, it was like another full-time job.” She still remains available for trouble-shooting during the day. It’s a project she has taken on with passion.

The support line began as a response to watching colleagues struggle with COVID. Since it launched, there have been approximately 2,000 calls. Calls typically last for 20 to 90 minutes, and no one has called with a suicidal crisis. It is now open to doctors and medical students looking for support for any reason. “Physicians call with all kinds of issues. In the first 3 months, it was COVID, but then they called with other concerns – there were doctors who called with election anxiety, really anything that affects the general public also affects us.”

The group has also offered Saturday didactic sessions for volunteers and weekly debriefing sessions. Dr. Masood has been approached by Vibrant Emotional Health, the administrator of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, about resources to help with funding – until now, this endeavor has had no financing – and she is hopeful that their financial support will allow the support line to sustain itself and grow. Future directions include advocating for systemic change in how physician mental health and wellness issues are addressed.

The Physician Support Line was one psychiatrist’s vision for how to address a problem. Like so many things related to this pandemic, it happened quickly and with surprising efficiency. Implementing this service, however, was not easy – it required hard work, innovative thinking, and passion. Those looking for someone to listen can call 1-888-409-0141 and psychiatrists who wish to volunteer can sign up at physiciansupportline.com/volunteer-info.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore.

The psychiatrist’s role in navigating a toxic news cycle

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Gregory Scott Brown, an Austin (Tex.)-based psychiatrist and an affiliate faculty member at the University of Texas Dell Medical School.

Recently, a patient of mine told me that, because of the political environment we find ourselves in, he’s avoiding conversations with some of his longtime friends. Because of this, he’s feeling even more isolated than before.

We’re all coming off the heels of a tough year, and many of us expected that when we entered 2021 we’d quickly turn the page and life would get a whole lot easier. Since the reality is that we’re still dealing with deep divisions, social injustices, and the politicization of evidence-based medicine, emotions are naturally running high.

In listening to my patients over the past few weeks, there’s definitely a sense of optimism about coronavirus vaccines and getting back to life as usual. But there’s also a lingering sense of uncertainty and fear, especially when it comes to the possibility of saying the wrong thing, offending our friends, or just having conversations with people we may disagree with. I’m hearing concerns from my patients that 2020 exposed a dormant hatred that was brewing in the underbelly of our society, in our politics, and in our institutions. Patients are telling me that these concerns are making them anxious and some are avoiding interacting with people they may disagree with altogether because they’re afraid of the difficult conversations that may follow.

Since, like many of my patients as well as many of you, I follow the news, including stories of COVID-related deaths, economic hardships, peaceful protests gone bad, and political vitriol, I’ve had to remind myself about the importance of intentional kindness for effective communication and for supporting mental health.

I was reminded of the paper “Hate in the Counter-Transference” by the well-known pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. He focuses on how to manage and sort through the strong emotions that may be experienced even during an encounter between a therapist and a patient. Although some of what he has to say doesn’t translate well to modern times, his recommendation that we acknowledge and try to normalize some of our feelings does. And this is how I’ve been starting a conversation with my patients – just by normalizing things a bit.

The past year or so has brought with it a range of intense emotions, including frustration, exhaustion, and some degree of sadness for most of us. When we’re self-aware about our feelings, we can make sense of them early on so that they don’t evolve into maladaptive ones like unhinged anger or hatred. My patients and I actively discuss how our feelings don’t have to get in the way of our ability to live and to interact with each other as we’d like to.

Considering the basic tenets of kindness is a good place to start. I recently spoke with Kelli Harding, MD, a psychiatrist and author of The Rabbit Effect: Live Longer, Happier, and Healthier with the Groundbreaking Science of Kindness. She pointed to research suggesting that kindness can benefit multiple areas of our health, from reducing cardiovascular events to improving mood and anxiety. In her book, she notes that

I tell my patients that we can’t always change our environment, but we can definitely change how we respond to it. This doesn’t mean it’s always an easy process, but there are things we can do. First, we have to acknowledge that some degree of conflict or cordial disagreement is inevitable and it doesn’t have to disrupt our mood.

An interesting study on conflict management pointed out that healthy conflict is actually beneficial in some cases. For instance, in the work environment, conflict can help with team development and better group decision-making. But it’s rigid personality differences, poor communication, emotional stress, and lack of candor that may contribute to so-called high-tension events, and this is where conflict can go awry. These are the areas that we can all focus on improving, not only for performance benefits but for our overall health and well-being as well.

The authors also recommend an active style of engagement as a technique to manage conflict, but in a way that feels both natural and safe. Other authors agree that so-called engaged coping is associated with a higher sense of control and overall improved psychological well-being. What this means is that avoidance may be necessary in the short term, but over time it may lead to more emotional stress and anxiety.

Overcoming the tendency to avoid requires both motivation and self-awareness. We need to know about patterns in our own behavior and how the behavior of others can push our buttons and spiral a healthy disagreement into a heated argument.

I like to recommend the hunger, angry, lonely, tired (HALT) model, which is often used as a self-care gauge in addiction treatment and to reduce medication errors. But I think it’s also a useful way to assess personal readiness for having a difficult conversation. I tell my patients to ask themselves in this moment: “Am I hungry, angry, lonely, or tired?” And if they are, perhaps it’s not the best time for the conversation.

Because 2020 brought with it a new set of challenges, it also forced many of us to focus on things that we just didn’t pay as much attention to before, including checking in on our feelings and the feelings of those around us. It also taught us to pay attention to the way and manner in which we communicate. I think that kindness is much easier to carry into difficult conversations if we approach them with a sense of curiosity before judgment. Ultimately, kindness is one of the best tools for balancing the intense emotions that many of us are feeling right now.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Gregory Scott Brown, an Austin (Tex.)-based psychiatrist and an affiliate faculty member at the University of Texas Dell Medical School.

Recently, a patient of mine told me that, because of the political environment we find ourselves in, he’s avoiding conversations with some of his longtime friends. Because of this, he’s feeling even more isolated than before.

We’re all coming off the heels of a tough year, and many of us expected that when we entered 2021 we’d quickly turn the page and life would get a whole lot easier. Since the reality is that we’re still dealing with deep divisions, social injustices, and the politicization of evidence-based medicine, emotions are naturally running high.

In listening to my patients over the past few weeks, there’s definitely a sense of optimism about coronavirus vaccines and getting back to life as usual. But there’s also a lingering sense of uncertainty and fear, especially when it comes to the possibility of saying the wrong thing, offending our friends, or just having conversations with people we may disagree with. I’m hearing concerns from my patients that 2020 exposed a dormant hatred that was brewing in the underbelly of our society, in our politics, and in our institutions. Patients are telling me that these concerns are making them anxious and some are avoiding interacting with people they may disagree with altogether because they’re afraid of the difficult conversations that may follow.

Since, like many of my patients as well as many of you, I follow the news, including stories of COVID-related deaths, economic hardships, peaceful protests gone bad, and political vitriol, I’ve had to remind myself about the importance of intentional kindness for effective communication and for supporting mental health.

I was reminded of the paper “Hate in the Counter-Transference” by the well-known pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. He focuses on how to manage and sort through the strong emotions that may be experienced even during an encounter between a therapist and a patient. Although some of what he has to say doesn’t translate well to modern times, his recommendation that we acknowledge and try to normalize some of our feelings does. And this is how I’ve been starting a conversation with my patients – just by normalizing things a bit.

The past year or so has brought with it a range of intense emotions, including frustration, exhaustion, and some degree of sadness for most of us. When we’re self-aware about our feelings, we can make sense of them early on so that they don’t evolve into maladaptive ones like unhinged anger or hatred. My patients and I actively discuss how our feelings don’t have to get in the way of our ability to live and to interact with each other as we’d like to.

Considering the basic tenets of kindness is a good place to start. I recently spoke with Kelli Harding, MD, a psychiatrist and author of The Rabbit Effect: Live Longer, Happier, and Healthier with the Groundbreaking Science of Kindness. She pointed to research suggesting that kindness can benefit multiple areas of our health, from reducing cardiovascular events to improving mood and anxiety. In her book, she notes that

I tell my patients that we can’t always change our environment, but we can definitely change how we respond to it. This doesn’t mean it’s always an easy process, but there are things we can do. First, we have to acknowledge that some degree of conflict or cordial disagreement is inevitable and it doesn’t have to disrupt our mood.

An interesting study on conflict management pointed out that healthy conflict is actually beneficial in some cases. For instance, in the work environment, conflict can help with team development and better group decision-making. But it’s rigid personality differences, poor communication, emotional stress, and lack of candor that may contribute to so-called high-tension events, and this is where conflict can go awry. These are the areas that we can all focus on improving, not only for performance benefits but for our overall health and well-being as well.

The authors also recommend an active style of engagement as a technique to manage conflict, but in a way that feels both natural and safe. Other authors agree that so-called engaged coping is associated with a higher sense of control and overall improved psychological well-being. What this means is that avoidance may be necessary in the short term, but over time it may lead to more emotional stress and anxiety.

Overcoming the tendency to avoid requires both motivation and self-awareness. We need to know about patterns in our own behavior and how the behavior of others can push our buttons and spiral a healthy disagreement into a heated argument.

I like to recommend the hunger, angry, lonely, tired (HALT) model, which is often used as a self-care gauge in addiction treatment and to reduce medication errors. But I think it’s also a useful way to assess personal readiness for having a difficult conversation. I tell my patients to ask themselves in this moment: “Am I hungry, angry, lonely, or tired?” And if they are, perhaps it’s not the best time for the conversation.

Because 2020 brought with it a new set of challenges, it also forced many of us to focus on things that we just didn’t pay as much attention to before, including checking in on our feelings and the feelings of those around us. It also taught us to pay attention to the way and manner in which we communicate. I think that kindness is much easier to carry into difficult conversations if we approach them with a sense of curiosity before judgment. Ultimately, kindness is one of the best tools for balancing the intense emotions that many of us are feeling right now.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Gregory Scott Brown, an Austin (Tex.)-based psychiatrist and an affiliate faculty member at the University of Texas Dell Medical School.

Recently, a patient of mine told me that, because of the political environment we find ourselves in, he’s avoiding conversations with some of his longtime friends. Because of this, he’s feeling even more isolated than before.

We’re all coming off the heels of a tough year, and many of us expected that when we entered 2021 we’d quickly turn the page and life would get a whole lot easier. Since the reality is that we’re still dealing with deep divisions, social injustices, and the politicization of evidence-based medicine, emotions are naturally running high.

In listening to my patients over the past few weeks, there’s definitely a sense of optimism about coronavirus vaccines and getting back to life as usual. But there’s also a lingering sense of uncertainty and fear, especially when it comes to the possibility of saying the wrong thing, offending our friends, or just having conversations with people we may disagree with. I’m hearing concerns from my patients that 2020 exposed a dormant hatred that was brewing in the underbelly of our society, in our politics, and in our institutions. Patients are telling me that these concerns are making them anxious and some are avoiding interacting with people they may disagree with altogether because they’re afraid of the difficult conversations that may follow.

Since, like many of my patients as well as many of you, I follow the news, including stories of COVID-related deaths, economic hardships, peaceful protests gone bad, and political vitriol, I’ve had to remind myself about the importance of intentional kindness for effective communication and for supporting mental health.

I was reminded of the paper “Hate in the Counter-Transference” by the well-known pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. He focuses on how to manage and sort through the strong emotions that may be experienced even during an encounter between a therapist and a patient. Although some of what he has to say doesn’t translate well to modern times, his recommendation that we acknowledge and try to normalize some of our feelings does. And this is how I’ve been starting a conversation with my patients – just by normalizing things a bit.

The past year or so has brought with it a range of intense emotions, including frustration, exhaustion, and some degree of sadness for most of us. When we’re self-aware about our feelings, we can make sense of them early on so that they don’t evolve into maladaptive ones like unhinged anger or hatred. My patients and I actively discuss how our feelings don’t have to get in the way of our ability to live and to interact with each other as we’d like to.

Considering the basic tenets of kindness is a good place to start. I recently spoke with Kelli Harding, MD, a psychiatrist and author of The Rabbit Effect: Live Longer, Happier, and Healthier with the Groundbreaking Science of Kindness. She pointed to research suggesting that kindness can benefit multiple areas of our health, from reducing cardiovascular events to improving mood and anxiety. In her book, she notes that

I tell my patients that we can’t always change our environment, but we can definitely change how we respond to it. This doesn’t mean it’s always an easy process, but there are things we can do. First, we have to acknowledge that some degree of conflict or cordial disagreement is inevitable and it doesn’t have to disrupt our mood.

An interesting study on conflict management pointed out that healthy conflict is actually beneficial in some cases. For instance, in the work environment, conflict can help with team development and better group decision-making. But it’s rigid personality differences, poor communication, emotional stress, and lack of candor that may contribute to so-called high-tension events, and this is where conflict can go awry. These are the areas that we can all focus on improving, not only for performance benefits but for our overall health and well-being as well.

The authors also recommend an active style of engagement as a technique to manage conflict, but in a way that feels both natural and safe. Other authors agree that so-called engaged coping is associated with a higher sense of control and overall improved psychological well-being. What this means is that avoidance may be necessary in the short term, but over time it may lead to more emotional stress and anxiety.

Overcoming the tendency to avoid requires both motivation and self-awareness. We need to know about patterns in our own behavior and how the behavior of others can push our buttons and spiral a healthy disagreement into a heated argument.

I like to recommend the hunger, angry, lonely, tired (HALT) model, which is often used as a self-care gauge in addiction treatment and to reduce medication errors. But I think it’s also a useful way to assess personal readiness for having a difficult conversation. I tell my patients to ask themselves in this moment: “Am I hungry, angry, lonely, or tired?” And if they are, perhaps it’s not the best time for the conversation.

Because 2020 brought with it a new set of challenges, it also forced many of us to focus on things that we just didn’t pay as much attention to before, including checking in on our feelings and the feelings of those around us. It also taught us to pay attention to the way and manner in which we communicate. I think that kindness is much easier to carry into difficult conversations if we approach them with a sense of curiosity before judgment. Ultimately, kindness is one of the best tools for balancing the intense emotions that many of us are feeling right now.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Landmark’ schizophrenia drug in the wings?

A novel therapy that combines a muscarinic receptor agonist with an anticholinergic agent is associated with a greater reduction in psychosis symptoms, compared with placebo, new research shows.

In a randomized, phase 2 trial composed of nearly 200 participants, xanomeline-trospium (KarXT) was generally well tolerated and had none of the common side effects linked to current antipsychotics, including weight gain and extrapyramidal symptoms such as dystonia, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia.

“The results showing robust therapeutic efficacy of a non–dopamine targeting antipsychotic drug is an important milestone in the advance of the therapeutics of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders,” coinvestigator Jeffrey A. Lieberman, MD, professor and chairman in the department of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

If approved, the new agent will be a “landmark” drug, Dr. Lieberman added.

The study was published in the Feb. 25, 2021, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Long journey

The journey to develop an effective schizophrenia drug that reduces psychosis symptoms without onerous side effects has been a long one full of excitement and disappointment.

First-generation antipsychotics, dating back to the 1950s, targeted the postsynaptic dopamine-2 (D2) receptor. At the time, it was a “breakthrough” similar in scope to insulin for diabetes or antibiotics for infections, said Dr. Lieberman.

That was followed by development of numerous “me too” drugs with the same mechanism of action. However, these drugs had significant side effects, especially neurologic adverse events such as parkinsonism.

In 1989, second-generation antipsychotics were introduced, beginning with clozapine. They still targeted the D2 receptor but were “kinder and gentler,” Dr. Lieberman noted. “They didn’t bind to [the receptor] with such affinity that it shut things down completely, so had fewer neurologic side effects.”

However, these agents had other adverse consequences, such as weight gain and other metabolic effects including hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia.