User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

High rates of work-related trauma, PTSD in intern physicians

Work-related posttraumatic stress disorder is three times higher in interns than the general population, new research shows.

Investigators assessed PTSD in more than 1,100 physicians at the end of their internship year and found that a little over half reported work-related trauma exposure, and of these, 20% screened positive for PTSD.

Overall, 10% of participants screened positive for PTSD by the end of the internship year, compared with a 12-month PTSD prevalence of 3.6% in the general population.

“Work-related trauma exposure and PTSD are common and underdiscussed phenomena among intern physicians,” lead author Mary Vance, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., said in an interview.

“I urge medical educators and policy makers to include this topic in their discussions about physician well-being and to implement effective interventions to mitigate the impact of work-related trauma and PTSD among physician trainees,” she said.

The study was published online June 8 in JAMA Network Open.

Burnout, depression, suicide

“Burnout, depression, and suicide are increasingly recognized as occupational mental health hazards among health care professionals, including physicians,” Dr. Vance said.

“However, in my professional experience as a physician and educator, despite observing anecdotal evidence among my peers and trainees that this is also an issue,” she added.

This gap prompted her “to investigate rates of work-related trauma exposure and PTSD among physicians.”

The researchers sent emails to 4,350 individuals during academic year 2018-2019, 2 months prior to starting internships. Of these, 2,129 agreed to participate and 1,134 (58.6% female, 61.6% non-Hispanic White; mean age, 27.52) completed the study.

Prior to beginning internship, participants completed a baseline survey that assessed demographic characteristics as well as medical education and psychological and psychosocial factors.

Participants completed follow-up surveys sent by email at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of the internship year. The surveys assessed stressful life events, concern over perceived medical errors in the past 3 months, and number of hours worked over the past week.

At month 12, current PTSD and symptoms of depression and anxiety were also assessed using the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5, the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale, respectively.

Participants were asked to self-report whether they ever had an episode of depression and to complete the Risky Families Questionnaire to assess if they had experienced childhood abuse, neglect, and family conflict. Additionally, they completed an 11-item scale developed specifically for the study regarding recent stressful events.

‘Crucible’ year

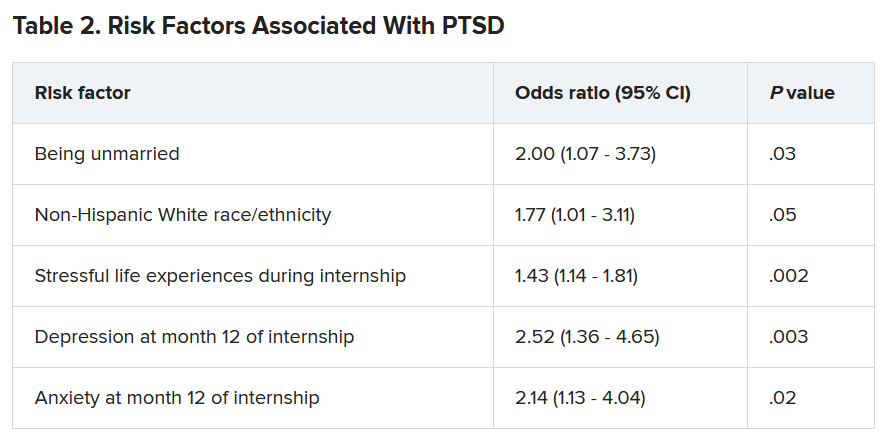

A total of 56.4% of respondents reported work-related trauma exposure, and among these, 19.0% screened positive for PTSD. One-tenth (10.8%) of the entire sample screened positive for PTSD by the end of internship year, which is three times higher than the 12-month prevalence of PTSD in the general population (3.6%), the authors noted.

Trauma exposure differed by specialty, ranging from 43.1% in anesthesiology to 72.4% in emergency medicine. Of the respondents in internal medicine, surgery, and medicine/pediatrics, 56.6%, 63.3%, and 71%, respectively, reported work-related trauma exposure.

Work-related PTSD also differed by specialty, ranging from 7.5% in ob.gyn. to 30.0% in pediatrics. Of respondents in internal medicine and family practice, 23.9% and 25.9%, respectively, reported work-related PTSD.

Dr. Vance called the intern year “a crucible, during which newly minted doctors receive intensive on-the-job training at the front lines of patient care [and] work long hours in rapidly shifting environments, often caring for critically ill patients.”

Work-related trauma exposure “is more likely to occur during this high-stress internship year than during the same year in the general population,” she said.

She noted that the “issue of workplace trauma and PTSD among health care workers became even more salient during the height of COVID,” adding that she expects it “to remain a pressure issue for healthcare workers in the post-COVID era.”

Call to action

Commenting on the study David A. Marcus, MD, chair, GME Physician Well-Being Committee, Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, N.Y., noted the study’s “relatively low response rate” is a “significant limitation” of the study.

An additional limitation is the lack of a baseline PTSD assessment, said Dr. Marcus, an assistant professor at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., who was not involved in the research.

Nevertheless, the “overall prevalence [of work-related PTSD] should serve as a call to action for physician leaders and for leaders in academic medicine,” he said.

Additionally, the study “reminds us that trauma-informed care should be an essential part of mental health support services provided to trainees and to physicians in general,” Dr. Marcus stated.

Also commenting on the study, Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, professor of medicine and medical education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., agreed.

“Organizational strategies should include system-level interventions to reduce the risk of frightening, horrible, or traumatic events from occurring in the workplace in the first place, as well as faculty development efforts to upskill teaching faculty in their ability to support trainees when such events do occur,” she said.

These approaches “should coincide with organizational efforts to support individual trainees by providing adequate time off after traumatic events, ensuring trainees can access affordable mental healthcare, and reducing other barriers to appropriate help-seeking, such as stigma, and efforts to build a culture of well-being,” suggested Dr. Dyrbye, who is codirector of the Mayo Clinic Program on Physician Wellbeing and was not involved in the study.

The study was supported by grants from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Vance and coauthors, Dr. Marcus, and Dr. Dyrbye reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Work-related posttraumatic stress disorder is three times higher in interns than the general population, new research shows.

Investigators assessed PTSD in more than 1,100 physicians at the end of their internship year and found that a little over half reported work-related trauma exposure, and of these, 20% screened positive for PTSD.

Overall, 10% of participants screened positive for PTSD by the end of the internship year, compared with a 12-month PTSD prevalence of 3.6% in the general population.

“Work-related trauma exposure and PTSD are common and underdiscussed phenomena among intern physicians,” lead author Mary Vance, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., said in an interview.

“I urge medical educators and policy makers to include this topic in their discussions about physician well-being and to implement effective interventions to mitigate the impact of work-related trauma and PTSD among physician trainees,” she said.

The study was published online June 8 in JAMA Network Open.

Burnout, depression, suicide

“Burnout, depression, and suicide are increasingly recognized as occupational mental health hazards among health care professionals, including physicians,” Dr. Vance said.

“However, in my professional experience as a physician and educator, despite observing anecdotal evidence among my peers and trainees that this is also an issue,” she added.

This gap prompted her “to investigate rates of work-related trauma exposure and PTSD among physicians.”

The researchers sent emails to 4,350 individuals during academic year 2018-2019, 2 months prior to starting internships. Of these, 2,129 agreed to participate and 1,134 (58.6% female, 61.6% non-Hispanic White; mean age, 27.52) completed the study.

Prior to beginning internship, participants completed a baseline survey that assessed demographic characteristics as well as medical education and psychological and psychosocial factors.

Participants completed follow-up surveys sent by email at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of the internship year. The surveys assessed stressful life events, concern over perceived medical errors in the past 3 months, and number of hours worked over the past week.

At month 12, current PTSD and symptoms of depression and anxiety were also assessed using the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5, the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale, respectively.

Participants were asked to self-report whether they ever had an episode of depression and to complete the Risky Families Questionnaire to assess if they had experienced childhood abuse, neglect, and family conflict. Additionally, they completed an 11-item scale developed specifically for the study regarding recent stressful events.

‘Crucible’ year

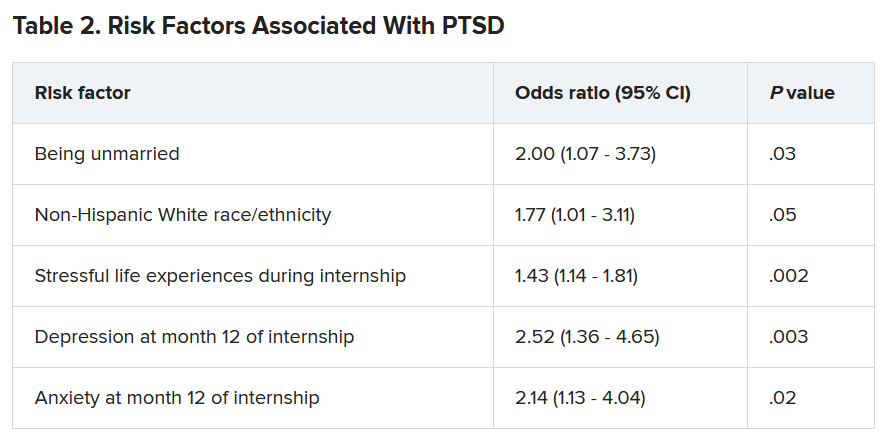

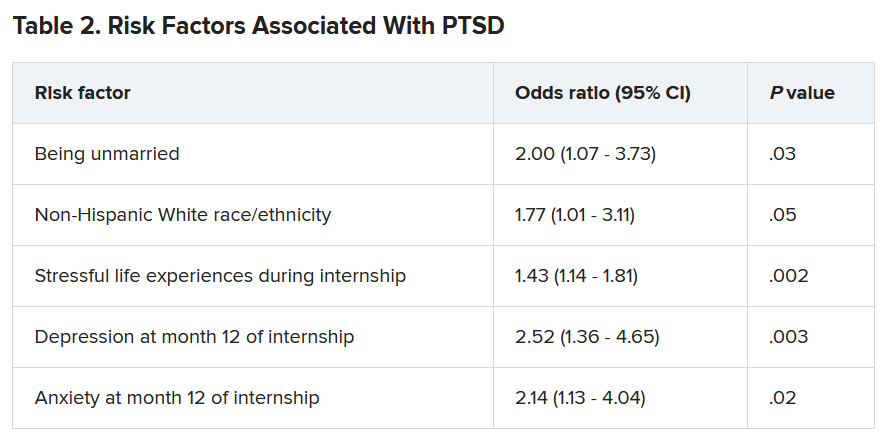

A total of 56.4% of respondents reported work-related trauma exposure, and among these, 19.0% screened positive for PTSD. One-tenth (10.8%) of the entire sample screened positive for PTSD by the end of internship year, which is three times higher than the 12-month prevalence of PTSD in the general population (3.6%), the authors noted.

Trauma exposure differed by specialty, ranging from 43.1% in anesthesiology to 72.4% in emergency medicine. Of the respondents in internal medicine, surgery, and medicine/pediatrics, 56.6%, 63.3%, and 71%, respectively, reported work-related trauma exposure.

Work-related PTSD also differed by specialty, ranging from 7.5% in ob.gyn. to 30.0% in pediatrics. Of respondents in internal medicine and family practice, 23.9% and 25.9%, respectively, reported work-related PTSD.

Dr. Vance called the intern year “a crucible, during which newly minted doctors receive intensive on-the-job training at the front lines of patient care [and] work long hours in rapidly shifting environments, often caring for critically ill patients.”

Work-related trauma exposure “is more likely to occur during this high-stress internship year than during the same year in the general population,” she said.

She noted that the “issue of workplace trauma and PTSD among health care workers became even more salient during the height of COVID,” adding that she expects it “to remain a pressure issue for healthcare workers in the post-COVID era.”

Call to action

Commenting on the study David A. Marcus, MD, chair, GME Physician Well-Being Committee, Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, N.Y., noted the study’s “relatively low response rate” is a “significant limitation” of the study.

An additional limitation is the lack of a baseline PTSD assessment, said Dr. Marcus, an assistant professor at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., who was not involved in the research.

Nevertheless, the “overall prevalence [of work-related PTSD] should serve as a call to action for physician leaders and for leaders in academic medicine,” he said.

Additionally, the study “reminds us that trauma-informed care should be an essential part of mental health support services provided to trainees and to physicians in general,” Dr. Marcus stated.

Also commenting on the study, Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, professor of medicine and medical education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., agreed.

“Organizational strategies should include system-level interventions to reduce the risk of frightening, horrible, or traumatic events from occurring in the workplace in the first place, as well as faculty development efforts to upskill teaching faculty in their ability to support trainees when such events do occur,” she said.

These approaches “should coincide with organizational efforts to support individual trainees by providing adequate time off after traumatic events, ensuring trainees can access affordable mental healthcare, and reducing other barriers to appropriate help-seeking, such as stigma, and efforts to build a culture of well-being,” suggested Dr. Dyrbye, who is codirector of the Mayo Clinic Program on Physician Wellbeing and was not involved in the study.

The study was supported by grants from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Vance and coauthors, Dr. Marcus, and Dr. Dyrbye reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Work-related posttraumatic stress disorder is three times higher in interns than the general population, new research shows.

Investigators assessed PTSD in more than 1,100 physicians at the end of their internship year and found that a little over half reported work-related trauma exposure, and of these, 20% screened positive for PTSD.

Overall, 10% of participants screened positive for PTSD by the end of the internship year, compared with a 12-month PTSD prevalence of 3.6% in the general population.

“Work-related trauma exposure and PTSD are common and underdiscussed phenomena among intern physicians,” lead author Mary Vance, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., said in an interview.

“I urge medical educators and policy makers to include this topic in their discussions about physician well-being and to implement effective interventions to mitigate the impact of work-related trauma and PTSD among physician trainees,” she said.

The study was published online June 8 in JAMA Network Open.

Burnout, depression, suicide

“Burnout, depression, and suicide are increasingly recognized as occupational mental health hazards among health care professionals, including physicians,” Dr. Vance said.

“However, in my professional experience as a physician and educator, despite observing anecdotal evidence among my peers and trainees that this is also an issue,” she added.

This gap prompted her “to investigate rates of work-related trauma exposure and PTSD among physicians.”

The researchers sent emails to 4,350 individuals during academic year 2018-2019, 2 months prior to starting internships. Of these, 2,129 agreed to participate and 1,134 (58.6% female, 61.6% non-Hispanic White; mean age, 27.52) completed the study.

Prior to beginning internship, participants completed a baseline survey that assessed demographic characteristics as well as medical education and psychological and psychosocial factors.

Participants completed follow-up surveys sent by email at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of the internship year. The surveys assessed stressful life events, concern over perceived medical errors in the past 3 months, and number of hours worked over the past week.

At month 12, current PTSD and symptoms of depression and anxiety were also assessed using the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5, the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale, respectively.

Participants were asked to self-report whether they ever had an episode of depression and to complete the Risky Families Questionnaire to assess if they had experienced childhood abuse, neglect, and family conflict. Additionally, they completed an 11-item scale developed specifically for the study regarding recent stressful events.

‘Crucible’ year

A total of 56.4% of respondents reported work-related trauma exposure, and among these, 19.0% screened positive for PTSD. One-tenth (10.8%) of the entire sample screened positive for PTSD by the end of internship year, which is three times higher than the 12-month prevalence of PTSD in the general population (3.6%), the authors noted.

Trauma exposure differed by specialty, ranging from 43.1% in anesthesiology to 72.4% in emergency medicine. Of the respondents in internal medicine, surgery, and medicine/pediatrics, 56.6%, 63.3%, and 71%, respectively, reported work-related trauma exposure.

Work-related PTSD also differed by specialty, ranging from 7.5% in ob.gyn. to 30.0% in pediatrics. Of respondents in internal medicine and family practice, 23.9% and 25.9%, respectively, reported work-related PTSD.

Dr. Vance called the intern year “a crucible, during which newly minted doctors receive intensive on-the-job training at the front lines of patient care [and] work long hours in rapidly shifting environments, often caring for critically ill patients.”

Work-related trauma exposure “is more likely to occur during this high-stress internship year than during the same year in the general population,” she said.

She noted that the “issue of workplace trauma and PTSD among health care workers became even more salient during the height of COVID,” adding that she expects it “to remain a pressure issue for healthcare workers in the post-COVID era.”

Call to action

Commenting on the study David A. Marcus, MD, chair, GME Physician Well-Being Committee, Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, N.Y., noted the study’s “relatively low response rate” is a “significant limitation” of the study.

An additional limitation is the lack of a baseline PTSD assessment, said Dr. Marcus, an assistant professor at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., who was not involved in the research.

Nevertheless, the “overall prevalence [of work-related PTSD] should serve as a call to action for physician leaders and for leaders in academic medicine,” he said.

Additionally, the study “reminds us that trauma-informed care should be an essential part of mental health support services provided to trainees and to physicians in general,” Dr. Marcus stated.

Also commenting on the study, Lotte N. Dyrbye, MD, professor of medicine and medical education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., agreed.

“Organizational strategies should include system-level interventions to reduce the risk of frightening, horrible, or traumatic events from occurring in the workplace in the first place, as well as faculty development efforts to upskill teaching faculty in their ability to support trainees when such events do occur,” she said.

These approaches “should coincide with organizational efforts to support individual trainees by providing adequate time off after traumatic events, ensuring trainees can access affordable mental healthcare, and reducing other barriers to appropriate help-seeking, such as stigma, and efforts to build a culture of well-being,” suggested Dr. Dyrbye, who is codirector of the Mayo Clinic Program on Physician Wellbeing and was not involved in the study.

The study was supported by grants from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Vance and coauthors, Dr. Marcus, and Dr. Dyrbye reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ten killer steps to writing a great medical thriller

For many physicians and other professionals, aspirations of crafting a work of fiction are not uncommon — and with good reason. We are, after all, a generally well-disciplined bunch capable of completing complex tasks, and there is certainly no shortage of excitement and drama in medicine and surgery — ample fodder for thrilling stories. Nonetheless, writing a novel is a major commitment, and it requires persistence, patience, and dedicated time, especially for one with a busy medical career.

Getting started is not easy. Writing workshops are helpful, and in my case, I tried to mentor with some of the best. Before writing my novel, I attended workshops for aspiring novelists, given by noted physician authors Tess Gerritsen (Body Double, The Surgeon) and the late Michael Palmer (The Society, The Fifth Vial).

Writers are often advised to “write about what you know.” In my case, I combined my knowledge of medicine and my experience with the thoroughbred racing world to craft a thriller that one reviewer described as “Dick Francis meets Robin Cook.” For those who have never read the Dick Francis series, he was a renowned crime writer whose novels centered on horse racing in England. Having been an avid reader of both authors, that comparison was the ultimate compliment.

So against that backdrop, the novel Shedrow, along with some shared wisdom from a few legendary writers.

1. Start with the big “what if.” Any great story starts with that simple “what if” question. What if a series of high-profile executives in the managed care industry are serially murdered (Michael Palmer’s The Society)? What if a multimillion-dollar stallion dies suddenly under very mysterious circumstances on a supposedly secure farm in Kentucky (Dean DeLuke’s Shedrow)?

2. Put a MacGuffin to work in your story. Popularized by Alfred Hitchcock, the MacGuffin is that essential plot element that drives virtually all characters in the story, although it may be rather vague and meaningless to the story itself. In the iconic movie Pulp Fiction, the MacGuffin is the briefcase — everyone wants it, and we never do find out what’s in it.

3. Pacing is critical. Plot out the timeline of emotional highs and lows in a story. It should look like a rolling pattern of highs and lows that crescendo upward to the ultimate crisis. Take advantage of the fact that following any of those emotional peaks, you probably have the reader’s undivided attention. That would be a good time to provide backstory or fill in needed information for the reader – information that may be critical but perhaps not as exciting as what just transpired.

4. Torture your protagonists. Just when the reader thinks that the hero is finally home free, throw in another obstacle. Readers will empathize with the character and be drawn in by the unexpected hurdle.

5. Be original and surprise your readers. Create twists and turns that are totally unexpected, yet believable. This is easier said than done but will go a long way toward making your novel original, gripping, and unpredictable.

6. As a general rule, consider short sentences and short chapters. This is strictly a personal preference, but who can argue with James Patterson’s short chapters or with Robert Parker’s short and engaging sentences? Sentence length can be varied for effect, too, with shorter sentences serving to heighten action or increase tension.

7. Avoid the passive voice. Your readers want action. This is an important rule in almost any type of writing.

8. Keep descriptions brief. Long, drawn-out descriptions of the way characters look, or even setting descriptions, are easily overdone in a thriller. The thriller genre is very different from literary fiction in this regard. Stephen King advises writers to “just say what they see, then get on with the story.”

9. Sustain the reader’s interest throughout. Assess each chapter ending and determine whether the reader has been given enough reason to want to continue reading. Pose a question, end with a minor cliffhanger, or at least ensure that there is enough accumulated tension in the story.

10. Edit aggressively and cut out the fluff. Ernest Hemingway once confided to F. Scott Fitzgerald, “I write one page of masterpiece to 91 pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”

Dr. DeLuke is professor emeritus of oral and facial surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of the novel Shedrow.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For many physicians and other professionals, aspirations of crafting a work of fiction are not uncommon — and with good reason. We are, after all, a generally well-disciplined bunch capable of completing complex tasks, and there is certainly no shortage of excitement and drama in medicine and surgery — ample fodder for thrilling stories. Nonetheless, writing a novel is a major commitment, and it requires persistence, patience, and dedicated time, especially for one with a busy medical career.

Getting started is not easy. Writing workshops are helpful, and in my case, I tried to mentor with some of the best. Before writing my novel, I attended workshops for aspiring novelists, given by noted physician authors Tess Gerritsen (Body Double, The Surgeon) and the late Michael Palmer (The Society, The Fifth Vial).

Writers are often advised to “write about what you know.” In my case, I combined my knowledge of medicine and my experience with the thoroughbred racing world to craft a thriller that one reviewer described as “Dick Francis meets Robin Cook.” For those who have never read the Dick Francis series, he was a renowned crime writer whose novels centered on horse racing in England. Having been an avid reader of both authors, that comparison was the ultimate compliment.

So against that backdrop, the novel Shedrow, along with some shared wisdom from a few legendary writers.

1. Start with the big “what if.” Any great story starts with that simple “what if” question. What if a series of high-profile executives in the managed care industry are serially murdered (Michael Palmer’s The Society)? What if a multimillion-dollar stallion dies suddenly under very mysterious circumstances on a supposedly secure farm in Kentucky (Dean DeLuke’s Shedrow)?

2. Put a MacGuffin to work in your story. Popularized by Alfred Hitchcock, the MacGuffin is that essential plot element that drives virtually all characters in the story, although it may be rather vague and meaningless to the story itself. In the iconic movie Pulp Fiction, the MacGuffin is the briefcase — everyone wants it, and we never do find out what’s in it.

3. Pacing is critical. Plot out the timeline of emotional highs and lows in a story. It should look like a rolling pattern of highs and lows that crescendo upward to the ultimate crisis. Take advantage of the fact that following any of those emotional peaks, you probably have the reader’s undivided attention. That would be a good time to provide backstory or fill in needed information for the reader – information that may be critical but perhaps not as exciting as what just transpired.

4. Torture your protagonists. Just when the reader thinks that the hero is finally home free, throw in another obstacle. Readers will empathize with the character and be drawn in by the unexpected hurdle.

5. Be original and surprise your readers. Create twists and turns that are totally unexpected, yet believable. This is easier said than done but will go a long way toward making your novel original, gripping, and unpredictable.

6. As a general rule, consider short sentences and short chapters. This is strictly a personal preference, but who can argue with James Patterson’s short chapters or with Robert Parker’s short and engaging sentences? Sentence length can be varied for effect, too, with shorter sentences serving to heighten action or increase tension.

7. Avoid the passive voice. Your readers want action. This is an important rule in almost any type of writing.

8. Keep descriptions brief. Long, drawn-out descriptions of the way characters look, or even setting descriptions, are easily overdone in a thriller. The thriller genre is very different from literary fiction in this regard. Stephen King advises writers to “just say what they see, then get on with the story.”

9. Sustain the reader’s interest throughout. Assess each chapter ending and determine whether the reader has been given enough reason to want to continue reading. Pose a question, end with a minor cliffhanger, or at least ensure that there is enough accumulated tension in the story.

10. Edit aggressively and cut out the fluff. Ernest Hemingway once confided to F. Scott Fitzgerald, “I write one page of masterpiece to 91 pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”

Dr. DeLuke is professor emeritus of oral and facial surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of the novel Shedrow.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For many physicians and other professionals, aspirations of crafting a work of fiction are not uncommon — and with good reason. We are, after all, a generally well-disciplined bunch capable of completing complex tasks, and there is certainly no shortage of excitement and drama in medicine and surgery — ample fodder for thrilling stories. Nonetheless, writing a novel is a major commitment, and it requires persistence, patience, and dedicated time, especially for one with a busy medical career.

Getting started is not easy. Writing workshops are helpful, and in my case, I tried to mentor with some of the best. Before writing my novel, I attended workshops for aspiring novelists, given by noted physician authors Tess Gerritsen (Body Double, The Surgeon) and the late Michael Palmer (The Society, The Fifth Vial).

Writers are often advised to “write about what you know.” In my case, I combined my knowledge of medicine and my experience with the thoroughbred racing world to craft a thriller that one reviewer described as “Dick Francis meets Robin Cook.” For those who have never read the Dick Francis series, he was a renowned crime writer whose novels centered on horse racing in England. Having been an avid reader of both authors, that comparison was the ultimate compliment.

So against that backdrop, the novel Shedrow, along with some shared wisdom from a few legendary writers.

1. Start with the big “what if.” Any great story starts with that simple “what if” question. What if a series of high-profile executives in the managed care industry are serially murdered (Michael Palmer’s The Society)? What if a multimillion-dollar stallion dies suddenly under very mysterious circumstances on a supposedly secure farm in Kentucky (Dean DeLuke’s Shedrow)?

2. Put a MacGuffin to work in your story. Popularized by Alfred Hitchcock, the MacGuffin is that essential plot element that drives virtually all characters in the story, although it may be rather vague and meaningless to the story itself. In the iconic movie Pulp Fiction, the MacGuffin is the briefcase — everyone wants it, and we never do find out what’s in it.

3. Pacing is critical. Plot out the timeline of emotional highs and lows in a story. It should look like a rolling pattern of highs and lows that crescendo upward to the ultimate crisis. Take advantage of the fact that following any of those emotional peaks, you probably have the reader’s undivided attention. That would be a good time to provide backstory or fill in needed information for the reader – information that may be critical but perhaps not as exciting as what just transpired.

4. Torture your protagonists. Just when the reader thinks that the hero is finally home free, throw in another obstacle. Readers will empathize with the character and be drawn in by the unexpected hurdle.

5. Be original and surprise your readers. Create twists and turns that are totally unexpected, yet believable. This is easier said than done but will go a long way toward making your novel original, gripping, and unpredictable.

6. As a general rule, consider short sentences and short chapters. This is strictly a personal preference, but who can argue with James Patterson’s short chapters or with Robert Parker’s short and engaging sentences? Sentence length can be varied for effect, too, with shorter sentences serving to heighten action or increase tension.

7. Avoid the passive voice. Your readers want action. This is an important rule in almost any type of writing.

8. Keep descriptions brief. Long, drawn-out descriptions of the way characters look, or even setting descriptions, are easily overdone in a thriller. The thriller genre is very different from literary fiction in this regard. Stephen King advises writers to “just say what they see, then get on with the story.”

9. Sustain the reader’s interest throughout. Assess each chapter ending and determine whether the reader has been given enough reason to want to continue reading. Pose a question, end with a minor cliffhanger, or at least ensure that there is enough accumulated tension in the story.

10. Edit aggressively and cut out the fluff. Ernest Hemingway once confided to F. Scott Fitzgerald, “I write one page of masterpiece to 91 pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”

Dr. DeLuke is professor emeritus of oral and facial surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of the novel Shedrow.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Memory benefit seen with antihypertensives crossing blood-brain barrier

Over a 3-year period, cognitively normal older adults taking BBB-crossing antihypertensives demonstrated superior verbal memory, compared with similar individuals receiving non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, reported lead author Jean K. Ho, PhD, of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues.

According to the investigators, the findings add color to a known link between hypertension and neurologic degeneration, and may aid the search for new therapeutic targets.

“Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia, possibly through its effects on both cerebrovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Ho and colleagues wrote in Hypertension. “Studies of antihypertensive treatments have reported possible salutary effects on cognition and cerebrovascular disease, as well as Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology.”

In a previous study, individuals younger than 75 years exposed to antihypertensives had an 8% decreased risk of dementia per year of use, while another trial showed that intensive blood pressure–lowering therapy reduced mild cognitive impairment by 19%.

“Despite these encouraging findings ... larger meta-analytic studies have been hampered by the fact that pharmacokinetic properties are typically not considered in existing studies or routine clinical practice,” wrote Dr. Ho and colleagues. “The present study sought to fill this gap [in that it was] a large and longitudinal meta-analytic study of existing data recoded to assess the effects of BBB-crossing potential in renin-angiotensin system [RAS] treatments among hypertensive adults.”

Methods and results

The meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, and retrospective observational studies. The researchers assessed data on 12,849 individuals from 14 cohorts that received either BBB-crossing or non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives.

The BBB-crossing properties of RAS treatments were identified by a literature review. Of ACE inhibitors, captopril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril, and trandolapril were classified as BBB crossing, and benazepril, enalapril, moexipril, and quinapril were classified as non–BBB-crossing. Of ARBs, telmisartan and candesartan were considered BBB-crossing, and olmesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, and losartan were tagged as non–BBB-crossing.

Cognition was assessed via the following seven domains: executive function, attention, verbal memory learning, language, mental status, recall, and processing speed.

Compared with individuals taking non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, those taking BBB-crossing agents had significantly superior verbal memory (recall), with a maximum effect size of 0.07 (P = .03).

According to the investigators, this finding was particularly noteworthy, as the BBB-crossing group had relatively higher vascular risk burden and lower mean education level.

“These differences make it all the more remarkable that the BBB-crossing group displayed better memory ability over time despite these cognitive disadvantages,” the investigators wrote.

Still, not all the findings favored BBB-crossing agents. Individuals in the BBB-crossing group had relatively inferior attention ability, with a minimum effect size of –0.17 (P = .02).

The other cognitive measures were not significantly different between groups.

Clinicians may consider findings after accounting for other factors

Principal investigator Daniel A. Nation, PhD, associate professor of psychological science and a faculty member of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, suggested that the small difference in verbal memory between groups could be clinically significant over a longer period of time.

“Although the overall effect size was pretty small, if you look at how long it would take for someone [with dementia] to progress over many years of decline, it would actually end up being a pretty big effect,” Dr. Nation said in an interview. “Small effect sizes could actually end up preventing a lot of cases of dementia,” he added.

The conflicting results in the BBB-crossing group – better verbal memory but worse attention ability – were “surprising,” he noted.

“I sort of didn’t believe it at first,” Dr. Nation said, “because the memory finding is sort of replication – we’d observed the same exact effect on memory in a smaller sample in another study. ... The attention [finding], going another way, was a new thing.”

Dr. Nation suggested that the intergroup differences in attention ability may stem from idiosyncrasies of the tests used to measure that domain, which can be impacted by cardiovascular or brain vascular disease. Or it could be caused by something else entirely, he said, noting that further investigation is needed.

He added that the improvements in verbal memory within the BBB-crossing group could be caused by direct effects on the brain. He pointed out that certain ACE polymorphisms have been linked with Alzheimer’s disease risk, and those same polymorphisms, in animal models, lead to neurodegeneration, with reversal possible through administration of ACE inhibitors.

“It could be that what we’re observing has nothing really to do with blood pressure,” Dr. Nation explained. “This could be a neuronal effect on learning memory systems.”

He went on to suggest that clinicians may consider these findings when selecting antihypertensive agents for their patients, with the caveat that all other prescribing factors have already been taking to account.

“In the event that you’re going to give an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker anyway, and it ends up being a somewhat arbitrary decision in terms of which specific drug you’re going to give, then perhaps this is a piece of information you would take into account – that one gets in the brain and one doesn’t – in somebody at risk for cognitive decline,” Dr. Nation said.

Exact mechanisms of action unknown

Hélène Girouard, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology and physiology at the University of Montreal, said in an interview that the findings are “of considerable importance, knowing that brain alterations could begin as much as 30 years before manifestation of dementia.”

Since 2003, Dr. Girouard has been studying the cognitive effects of antihypertensive medications. She noted that previous studies involving rodents “have shown beneficial effects [of BBB-crossing antihypertensive drugs] on cognition independent of their effects on blood pressure.”

The drugs’ exact mechanisms of action, however, remain elusive, according to Dr. Girouard, who offered several possible explanations, including amelioration of BBB disruption, brain inflammation, cerebral blood flow dysregulation, cholinergic dysfunction, and neurologic deficits. “Whether these mechanisms may explain Ho and colleagues’ observations remains to be established,” she added.

Andrea L. Schneider, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, applauded the study, but ultimately suggested that more research is needed to impact clinical decision-making.

“The results of this important and well-done study suggest that further investigation into targeted mechanism-based approaches to selecting hypertension treatment agents, with a specific focus on cognitive outcomes, is warranted,” Dr. Schneider said in an interview. “Before changing clinical practice, further work is necessary to disentangle contributions of medication mechanism, comorbid vascular risk factors, and achieved blood pressure reduction, among others.”

The investigators disclosed support from the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Waksman Foundation of Japan, and others. The interviewees reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Over a 3-year period, cognitively normal older adults taking BBB-crossing antihypertensives demonstrated superior verbal memory, compared with similar individuals receiving non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, reported lead author Jean K. Ho, PhD, of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues.

According to the investigators, the findings add color to a known link between hypertension and neurologic degeneration, and may aid the search for new therapeutic targets.

“Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia, possibly through its effects on both cerebrovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Ho and colleagues wrote in Hypertension. “Studies of antihypertensive treatments have reported possible salutary effects on cognition and cerebrovascular disease, as well as Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology.”

In a previous study, individuals younger than 75 years exposed to antihypertensives had an 8% decreased risk of dementia per year of use, while another trial showed that intensive blood pressure–lowering therapy reduced mild cognitive impairment by 19%.

“Despite these encouraging findings ... larger meta-analytic studies have been hampered by the fact that pharmacokinetic properties are typically not considered in existing studies or routine clinical practice,” wrote Dr. Ho and colleagues. “The present study sought to fill this gap [in that it was] a large and longitudinal meta-analytic study of existing data recoded to assess the effects of BBB-crossing potential in renin-angiotensin system [RAS] treatments among hypertensive adults.”

Methods and results

The meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, and retrospective observational studies. The researchers assessed data on 12,849 individuals from 14 cohorts that received either BBB-crossing or non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives.

The BBB-crossing properties of RAS treatments were identified by a literature review. Of ACE inhibitors, captopril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril, and trandolapril were classified as BBB crossing, and benazepril, enalapril, moexipril, and quinapril were classified as non–BBB-crossing. Of ARBs, telmisartan and candesartan were considered BBB-crossing, and olmesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, and losartan were tagged as non–BBB-crossing.

Cognition was assessed via the following seven domains: executive function, attention, verbal memory learning, language, mental status, recall, and processing speed.

Compared with individuals taking non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, those taking BBB-crossing agents had significantly superior verbal memory (recall), with a maximum effect size of 0.07 (P = .03).

According to the investigators, this finding was particularly noteworthy, as the BBB-crossing group had relatively higher vascular risk burden and lower mean education level.

“These differences make it all the more remarkable that the BBB-crossing group displayed better memory ability over time despite these cognitive disadvantages,” the investigators wrote.

Still, not all the findings favored BBB-crossing agents. Individuals in the BBB-crossing group had relatively inferior attention ability, with a minimum effect size of –0.17 (P = .02).

The other cognitive measures were not significantly different between groups.

Clinicians may consider findings after accounting for other factors

Principal investigator Daniel A. Nation, PhD, associate professor of psychological science and a faculty member of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, suggested that the small difference in verbal memory between groups could be clinically significant over a longer period of time.

“Although the overall effect size was pretty small, if you look at how long it would take for someone [with dementia] to progress over many years of decline, it would actually end up being a pretty big effect,” Dr. Nation said in an interview. “Small effect sizes could actually end up preventing a lot of cases of dementia,” he added.

The conflicting results in the BBB-crossing group – better verbal memory but worse attention ability – were “surprising,” he noted.

“I sort of didn’t believe it at first,” Dr. Nation said, “because the memory finding is sort of replication – we’d observed the same exact effect on memory in a smaller sample in another study. ... The attention [finding], going another way, was a new thing.”

Dr. Nation suggested that the intergroup differences in attention ability may stem from idiosyncrasies of the tests used to measure that domain, which can be impacted by cardiovascular or brain vascular disease. Or it could be caused by something else entirely, he said, noting that further investigation is needed.

He added that the improvements in verbal memory within the BBB-crossing group could be caused by direct effects on the brain. He pointed out that certain ACE polymorphisms have been linked with Alzheimer’s disease risk, and those same polymorphisms, in animal models, lead to neurodegeneration, with reversal possible through administration of ACE inhibitors.

“It could be that what we’re observing has nothing really to do with blood pressure,” Dr. Nation explained. “This could be a neuronal effect on learning memory systems.”

He went on to suggest that clinicians may consider these findings when selecting antihypertensive agents for their patients, with the caveat that all other prescribing factors have already been taking to account.

“In the event that you’re going to give an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker anyway, and it ends up being a somewhat arbitrary decision in terms of which specific drug you’re going to give, then perhaps this is a piece of information you would take into account – that one gets in the brain and one doesn’t – in somebody at risk for cognitive decline,” Dr. Nation said.

Exact mechanisms of action unknown

Hélène Girouard, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology and physiology at the University of Montreal, said in an interview that the findings are “of considerable importance, knowing that brain alterations could begin as much as 30 years before manifestation of dementia.”

Since 2003, Dr. Girouard has been studying the cognitive effects of antihypertensive medications. She noted that previous studies involving rodents “have shown beneficial effects [of BBB-crossing antihypertensive drugs] on cognition independent of their effects on blood pressure.”

The drugs’ exact mechanisms of action, however, remain elusive, according to Dr. Girouard, who offered several possible explanations, including amelioration of BBB disruption, brain inflammation, cerebral blood flow dysregulation, cholinergic dysfunction, and neurologic deficits. “Whether these mechanisms may explain Ho and colleagues’ observations remains to be established,” she added.

Andrea L. Schneider, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, applauded the study, but ultimately suggested that more research is needed to impact clinical decision-making.

“The results of this important and well-done study suggest that further investigation into targeted mechanism-based approaches to selecting hypertension treatment agents, with a specific focus on cognitive outcomes, is warranted,” Dr. Schneider said in an interview. “Before changing clinical practice, further work is necessary to disentangle contributions of medication mechanism, comorbid vascular risk factors, and achieved blood pressure reduction, among others.”

The investigators disclosed support from the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Waksman Foundation of Japan, and others. The interviewees reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Over a 3-year period, cognitively normal older adults taking BBB-crossing antihypertensives demonstrated superior verbal memory, compared with similar individuals receiving non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, reported lead author Jean K. Ho, PhD, of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues.

According to the investigators, the findings add color to a known link between hypertension and neurologic degeneration, and may aid the search for new therapeutic targets.

“Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia, possibly through its effects on both cerebrovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Ho and colleagues wrote in Hypertension. “Studies of antihypertensive treatments have reported possible salutary effects on cognition and cerebrovascular disease, as well as Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology.”

In a previous study, individuals younger than 75 years exposed to antihypertensives had an 8% decreased risk of dementia per year of use, while another trial showed that intensive blood pressure–lowering therapy reduced mild cognitive impairment by 19%.

“Despite these encouraging findings ... larger meta-analytic studies have been hampered by the fact that pharmacokinetic properties are typically not considered in existing studies or routine clinical practice,” wrote Dr. Ho and colleagues. “The present study sought to fill this gap [in that it was] a large and longitudinal meta-analytic study of existing data recoded to assess the effects of BBB-crossing potential in renin-angiotensin system [RAS] treatments among hypertensive adults.”

Methods and results

The meta-analysis included randomized clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, and retrospective observational studies. The researchers assessed data on 12,849 individuals from 14 cohorts that received either BBB-crossing or non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives.

The BBB-crossing properties of RAS treatments were identified by a literature review. Of ACE inhibitors, captopril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril, and trandolapril were classified as BBB crossing, and benazepril, enalapril, moexipril, and quinapril were classified as non–BBB-crossing. Of ARBs, telmisartan and candesartan were considered BBB-crossing, and olmesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, and losartan were tagged as non–BBB-crossing.

Cognition was assessed via the following seven domains: executive function, attention, verbal memory learning, language, mental status, recall, and processing speed.

Compared with individuals taking non–BBB-crossing antihypertensives, those taking BBB-crossing agents had significantly superior verbal memory (recall), with a maximum effect size of 0.07 (P = .03).

According to the investigators, this finding was particularly noteworthy, as the BBB-crossing group had relatively higher vascular risk burden and lower mean education level.

“These differences make it all the more remarkable that the BBB-crossing group displayed better memory ability over time despite these cognitive disadvantages,” the investigators wrote.

Still, not all the findings favored BBB-crossing agents. Individuals in the BBB-crossing group had relatively inferior attention ability, with a minimum effect size of –0.17 (P = .02).

The other cognitive measures were not significantly different between groups.

Clinicians may consider findings after accounting for other factors

Principal investigator Daniel A. Nation, PhD, associate professor of psychological science and a faculty member of the Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders at the University of California, Irvine, suggested that the small difference in verbal memory between groups could be clinically significant over a longer period of time.

“Although the overall effect size was pretty small, if you look at how long it would take for someone [with dementia] to progress over many years of decline, it would actually end up being a pretty big effect,” Dr. Nation said in an interview. “Small effect sizes could actually end up preventing a lot of cases of dementia,” he added.

The conflicting results in the BBB-crossing group – better verbal memory but worse attention ability – were “surprising,” he noted.

“I sort of didn’t believe it at first,” Dr. Nation said, “because the memory finding is sort of replication – we’d observed the same exact effect on memory in a smaller sample in another study. ... The attention [finding], going another way, was a new thing.”

Dr. Nation suggested that the intergroup differences in attention ability may stem from idiosyncrasies of the tests used to measure that domain, which can be impacted by cardiovascular or brain vascular disease. Or it could be caused by something else entirely, he said, noting that further investigation is needed.

He added that the improvements in verbal memory within the BBB-crossing group could be caused by direct effects on the brain. He pointed out that certain ACE polymorphisms have been linked with Alzheimer’s disease risk, and those same polymorphisms, in animal models, lead to neurodegeneration, with reversal possible through administration of ACE inhibitors.

“It could be that what we’re observing has nothing really to do with blood pressure,” Dr. Nation explained. “This could be a neuronal effect on learning memory systems.”

He went on to suggest that clinicians may consider these findings when selecting antihypertensive agents for their patients, with the caveat that all other prescribing factors have already been taking to account.

“In the event that you’re going to give an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker anyway, and it ends up being a somewhat arbitrary decision in terms of which specific drug you’re going to give, then perhaps this is a piece of information you would take into account – that one gets in the brain and one doesn’t – in somebody at risk for cognitive decline,” Dr. Nation said.

Exact mechanisms of action unknown

Hélène Girouard, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology and physiology at the University of Montreal, said in an interview that the findings are “of considerable importance, knowing that brain alterations could begin as much as 30 years before manifestation of dementia.”

Since 2003, Dr. Girouard has been studying the cognitive effects of antihypertensive medications. She noted that previous studies involving rodents “have shown beneficial effects [of BBB-crossing antihypertensive drugs] on cognition independent of their effects on blood pressure.”

The drugs’ exact mechanisms of action, however, remain elusive, according to Dr. Girouard, who offered several possible explanations, including amelioration of BBB disruption, brain inflammation, cerebral blood flow dysregulation, cholinergic dysfunction, and neurologic deficits. “Whether these mechanisms may explain Ho and colleagues’ observations remains to be established,” she added.

Andrea L. Schneider, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, applauded the study, but ultimately suggested that more research is needed to impact clinical decision-making.

“The results of this important and well-done study suggest that further investigation into targeted mechanism-based approaches to selecting hypertension treatment agents, with a specific focus on cognitive outcomes, is warranted,” Dr. Schneider said in an interview. “Before changing clinical practice, further work is necessary to disentangle contributions of medication mechanism, comorbid vascular risk factors, and achieved blood pressure reduction, among others.”

The investigators disclosed support from the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Waksman Foundation of Japan, and others. The interviewees reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM HYPERTENSION

How dreams might prepare you for what’s next

What you experience in your dreams might feel random and disjointed, but that chaos during sleep might serve a function, according to Erin Wamsley, PhD, an associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Furman University in Greenville, S.C. In fact, evidence uncovered by Dr. Wamsley and associates suggests that

Previous research and anecdotal evidence have shown that dreams use fragments of past experiences, Dr. Wamsley explained. While studying dreams, her team found that the mind is using select fragments of past experiences to prepare for a known upcoming event.

“This is new evidence that dreams reflect a memory-processing function,” said Dr. Wamsley, who presented the work at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Some high performers already use past experiences to excel in future events. For instance, Michael Phelps, the most decorated Olympic swimmer, with 28 medals, would “mentally rehearse” his swims for up to 2 hours per day, according to his coach, Bob Bowman.

Using sleep to strengthen this process is an exciting prospect that scientists have been eager to figure out, said Allison Brager, PhD, director of human performance at the U.S. Army Warrior Fitness Training Center. Deep REM sleep can lead to improved learning and memory, she said. “So, hypothetically, better dreams mean better sleep, and that equals better performance.”

For their research, Dr. Wamsley’s team hooked 48 students up to a polysomnography machine to measure sleep cycles and how often they were in a deep REM sleep. The students who took part in the study spent the night in a sleep lab.

The students were woken up multiple times during the night and asked to report what they were dreaming about.

In the morning, they were given their reports and asked to identify familiar features or potential sources for particular dreams. More than half the dreams were tied to a memory the students recalled. One-quarter of the dreams were related to specific upcoming events the students reported. And about 40% of the dreams with a future event in them also included memories of past experiences. This was more common the longer the students dreamed, the scientists explained.

And this was also more common later in the night, possibly because the dreamer is closer to waking and the anticipated event is approaching, Dr. Wamsley said.

Studying dreams is a tricky, subjective business and not always taken as seriously as other aspects of sleep and neuroscience because it involves questions of human consciousness itself, said Erik Hoel, PhD, a research assistant professor of neuroscience at Tufts University in Medford, Mass.

In a recent report published in Patterns, he suggested that our weirdest dreams help our brains process our day-to-day experiences in a way that enables deeper learning.

“This type of research is challenged by the method,” Dr. Hoel said.

In the Wamsley study, “waking people up from a deep sleep and asking them to recollect their dream content will only get you part of the experience because it fades so quickly.” That said, the value of connecting what happens as a result could be meaningful, he noted. For example, study participants could be asked whether their future event went as planned and whether they think the outcome was related to how well they “prepared” in their dreams.

Even then, it would still be a subjective analysis. But going in those directions might lead to meaningful new training, Dr. Hoel said.

And training yourself to recall only specific memories right before sleep might prepare your mind in a focused way for certain events, from giving a presentation to having a difficult conversation with someone, or maybe even winning at the Olympics.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

What you experience in your dreams might feel random and disjointed, but that chaos during sleep might serve a function, according to Erin Wamsley, PhD, an associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Furman University in Greenville, S.C. In fact, evidence uncovered by Dr. Wamsley and associates suggests that

Previous research and anecdotal evidence have shown that dreams use fragments of past experiences, Dr. Wamsley explained. While studying dreams, her team found that the mind is using select fragments of past experiences to prepare for a known upcoming event.

“This is new evidence that dreams reflect a memory-processing function,” said Dr. Wamsley, who presented the work at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Some high performers already use past experiences to excel in future events. For instance, Michael Phelps, the most decorated Olympic swimmer, with 28 medals, would “mentally rehearse” his swims for up to 2 hours per day, according to his coach, Bob Bowman.

Using sleep to strengthen this process is an exciting prospect that scientists have been eager to figure out, said Allison Brager, PhD, director of human performance at the U.S. Army Warrior Fitness Training Center. Deep REM sleep can lead to improved learning and memory, she said. “So, hypothetically, better dreams mean better sleep, and that equals better performance.”

For their research, Dr. Wamsley’s team hooked 48 students up to a polysomnography machine to measure sleep cycles and how often they were in a deep REM sleep. The students who took part in the study spent the night in a sleep lab.

The students were woken up multiple times during the night and asked to report what they were dreaming about.

In the morning, they were given their reports and asked to identify familiar features or potential sources for particular dreams. More than half the dreams were tied to a memory the students recalled. One-quarter of the dreams were related to specific upcoming events the students reported. And about 40% of the dreams with a future event in them also included memories of past experiences. This was more common the longer the students dreamed, the scientists explained.

And this was also more common later in the night, possibly because the dreamer is closer to waking and the anticipated event is approaching, Dr. Wamsley said.

Studying dreams is a tricky, subjective business and not always taken as seriously as other aspects of sleep and neuroscience because it involves questions of human consciousness itself, said Erik Hoel, PhD, a research assistant professor of neuroscience at Tufts University in Medford, Mass.

In a recent report published in Patterns, he suggested that our weirdest dreams help our brains process our day-to-day experiences in a way that enables deeper learning.

“This type of research is challenged by the method,” Dr. Hoel said.

In the Wamsley study, “waking people up from a deep sleep and asking them to recollect their dream content will only get you part of the experience because it fades so quickly.” That said, the value of connecting what happens as a result could be meaningful, he noted. For example, study participants could be asked whether their future event went as planned and whether they think the outcome was related to how well they “prepared” in their dreams.

Even then, it would still be a subjective analysis. But going in those directions might lead to meaningful new training, Dr. Hoel said.

And training yourself to recall only specific memories right before sleep might prepare your mind in a focused way for certain events, from giving a presentation to having a difficult conversation with someone, or maybe even winning at the Olympics.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

What you experience in your dreams might feel random and disjointed, but that chaos during sleep might serve a function, according to Erin Wamsley, PhD, an associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Furman University in Greenville, S.C. In fact, evidence uncovered by Dr. Wamsley and associates suggests that

Previous research and anecdotal evidence have shown that dreams use fragments of past experiences, Dr. Wamsley explained. While studying dreams, her team found that the mind is using select fragments of past experiences to prepare for a known upcoming event.

“This is new evidence that dreams reflect a memory-processing function,” said Dr. Wamsley, who presented the work at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Some high performers already use past experiences to excel in future events. For instance, Michael Phelps, the most decorated Olympic swimmer, with 28 medals, would “mentally rehearse” his swims for up to 2 hours per day, according to his coach, Bob Bowman.

Using sleep to strengthen this process is an exciting prospect that scientists have been eager to figure out, said Allison Brager, PhD, director of human performance at the U.S. Army Warrior Fitness Training Center. Deep REM sleep can lead to improved learning and memory, she said. “So, hypothetically, better dreams mean better sleep, and that equals better performance.”

For their research, Dr. Wamsley’s team hooked 48 students up to a polysomnography machine to measure sleep cycles and how often they were in a deep REM sleep. The students who took part in the study spent the night in a sleep lab.

The students were woken up multiple times during the night and asked to report what they were dreaming about.

In the morning, they were given their reports and asked to identify familiar features or potential sources for particular dreams. More than half the dreams were tied to a memory the students recalled. One-quarter of the dreams were related to specific upcoming events the students reported. And about 40% of the dreams with a future event in them also included memories of past experiences. This was more common the longer the students dreamed, the scientists explained.

And this was also more common later in the night, possibly because the dreamer is closer to waking and the anticipated event is approaching, Dr. Wamsley said.

Studying dreams is a tricky, subjective business and not always taken as seriously as other aspects of sleep and neuroscience because it involves questions of human consciousness itself, said Erik Hoel, PhD, a research assistant professor of neuroscience at Tufts University in Medford, Mass.

In a recent report published in Patterns, he suggested that our weirdest dreams help our brains process our day-to-day experiences in a way that enables deeper learning.

“This type of research is challenged by the method,” Dr. Hoel said.

In the Wamsley study, “waking people up from a deep sleep and asking them to recollect their dream content will only get you part of the experience because it fades so quickly.” That said, the value of connecting what happens as a result could be meaningful, he noted. For example, study participants could be asked whether their future event went as planned and whether they think the outcome was related to how well they “prepared” in their dreams.

Even then, it would still be a subjective analysis. But going in those directions might lead to meaningful new training, Dr. Hoel said.

And training yourself to recall only specific memories right before sleep might prepare your mind in a focused way for certain events, from giving a presentation to having a difficult conversation with someone, or maybe even winning at the Olympics.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM SLEEP 2021

Cortical surface changes tied to risk for movement disorders in schizophrenia

Schizophrenia patients with parkinsonism show distinctive patterns of cortical surface markers, compared with schizophrenia patients without parkinsonism and healthy controls, results of a multimodal magnetic resonance imaging study suggest.

Sensorimotor abnormalities are common in schizophrenia patients, however, “the neurobiological mechanisms underlying parkinsonism in [schizophrenia], which in treated samples represents the unity of interplay between spontaneous and antipsychotic drug-exacerbated movement disorder, are poorly understood,” wrote Robert Christian Wolf, MD, of Heidelberg (Germany) University, and colleagues.

In a study published in Schizophrenia Research (2021 May;231:54-60), the investigators examined brain imaging findings from 20 healthy controls, 38 schizophrenia patients with parkinsonism (SZ-P), and 35 schizophrenia patients without parkinsonism (SZ-nonP). Dr. Wolf and colleagues examined three cortical surface markers: cortical thickness, complexity of cortical folding, and sulcus depth.

Compared with SZ-nonP patients, the SZ-P patients showed significantly increased complexity of cortical folding in the left supplementary motor cortex (SMC) and significantly decreased left postcentral sulcus (PCS) depth. In addition, left SMC activity was higher in both SZ-P and SZ-nonP patient groups, compared with controls.

In a regression analysis, the researchers examined relationships between parkinsonism severity and brain structure. They found that parkinsonism severity was negatively associated with left middle frontal complexity of cortical folding and left anterior cingulate cortex cortical thickness.

“Overall, the data support the notion that cortical features of distinct neurodevelopmental origin, particularly cortical folding indices such as [complexity of cortical folding] and sulcus depth, contribute to the pathogenesis of parkinsonism in SZ,” the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the cross-sectional design, the potential limitations of the Simpson-Angus Scale in characterizing parkinsonism, the inability to record lifetime antibiotics exposure in the patient population, and the inability to identify changes in brain stem nuclei, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the well-matched study groups and use of multimodal MRI, they said.

Consequently, “,” and suggest a link between abnormal neurodevelopmental processes and an increased risk for movement disorders in schizophrenia, they concluded.

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Dr. Wolf and colleagues disclosed no conflicts.

Schizophrenia patients with parkinsonism show distinctive patterns of cortical surface markers, compared with schizophrenia patients without parkinsonism and healthy controls, results of a multimodal magnetic resonance imaging study suggest.

Sensorimotor abnormalities are common in schizophrenia patients, however, “the neurobiological mechanisms underlying parkinsonism in [schizophrenia], which in treated samples represents the unity of interplay between spontaneous and antipsychotic drug-exacerbated movement disorder, are poorly understood,” wrote Robert Christian Wolf, MD, of Heidelberg (Germany) University, and colleagues.

In a study published in Schizophrenia Research (2021 May;231:54-60), the investigators examined brain imaging findings from 20 healthy controls, 38 schizophrenia patients with parkinsonism (SZ-P), and 35 schizophrenia patients without parkinsonism (SZ-nonP). Dr. Wolf and colleagues examined three cortical surface markers: cortical thickness, complexity of cortical folding, and sulcus depth.

Compared with SZ-nonP patients, the SZ-P patients showed significantly increased complexity of cortical folding in the left supplementary motor cortex (SMC) and significantly decreased left postcentral sulcus (PCS) depth. In addition, left SMC activity was higher in both SZ-P and SZ-nonP patient groups, compared with controls.

In a regression analysis, the researchers examined relationships between parkinsonism severity and brain structure. They found that parkinsonism severity was negatively associated with left middle frontal complexity of cortical folding and left anterior cingulate cortex cortical thickness.

“Overall, the data support the notion that cortical features of distinct neurodevelopmental origin, particularly cortical folding indices such as [complexity of cortical folding] and sulcus depth, contribute to the pathogenesis of parkinsonism in SZ,” the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the cross-sectional design, the potential limitations of the Simpson-Angus Scale in characterizing parkinsonism, the inability to record lifetime antibiotics exposure in the patient population, and the inability to identify changes in brain stem nuclei, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the well-matched study groups and use of multimodal MRI, they said.

Consequently, “,” and suggest a link between abnormal neurodevelopmental processes and an increased risk for movement disorders in schizophrenia, they concluded.

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Dr. Wolf and colleagues disclosed no conflicts.

Schizophrenia patients with parkinsonism show distinctive patterns of cortical surface markers, compared with schizophrenia patients without parkinsonism and healthy controls, results of a multimodal magnetic resonance imaging study suggest.

Sensorimotor abnormalities are common in schizophrenia patients, however, “the neurobiological mechanisms underlying parkinsonism in [schizophrenia], which in treated samples represents the unity of interplay between spontaneous and antipsychotic drug-exacerbated movement disorder, are poorly understood,” wrote Robert Christian Wolf, MD, of Heidelberg (Germany) University, and colleagues.

In a study published in Schizophrenia Research (2021 May;231:54-60), the investigators examined brain imaging findings from 20 healthy controls, 38 schizophrenia patients with parkinsonism (SZ-P), and 35 schizophrenia patients without parkinsonism (SZ-nonP). Dr. Wolf and colleagues examined three cortical surface markers: cortical thickness, complexity of cortical folding, and sulcus depth.

Compared with SZ-nonP patients, the SZ-P patients showed significantly increased complexity of cortical folding in the left supplementary motor cortex (SMC) and significantly decreased left postcentral sulcus (PCS) depth. In addition, left SMC activity was higher in both SZ-P and SZ-nonP patient groups, compared with controls.

In a regression analysis, the researchers examined relationships between parkinsonism severity and brain structure. They found that parkinsonism severity was negatively associated with left middle frontal complexity of cortical folding and left anterior cingulate cortex cortical thickness.

“Overall, the data support the notion that cortical features of distinct neurodevelopmental origin, particularly cortical folding indices such as [complexity of cortical folding] and sulcus depth, contribute to the pathogenesis of parkinsonism in SZ,” the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the cross-sectional design, the potential limitations of the Simpson-Angus Scale in characterizing parkinsonism, the inability to record lifetime antibiotics exposure in the patient population, and the inability to identify changes in brain stem nuclei, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the well-matched study groups and use of multimodal MRI, they said.

Consequently, “,” and suggest a link between abnormal neurodevelopmental processes and an increased risk for movement disorders in schizophrenia, they concluded.

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Dr. Wolf and colleagues disclosed no conflicts.

FROM SCHIZOPHRENIA RESEARCH

Is trouble falling asleep a modifiable risk factor for dementia?

, new research suggests.

Trouble falling asleep “may be a modifiable risk factor for later-life cognitive impairment and dementia,” said lead author Afsara Zaheed, a PhD candidate in clinical science, department of psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.