User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Does PREDICT accurately estimate breast cancer survival?

The PREDICT score does not seem to be particularly accurate when it comes to estimating overall survival (OS) in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer who are treated with modern chemotherapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapies. This is the conclusion of an international study published in the journal npj Breast Cancer. The work was supervised by Matteo Lambertini, MD, PhD, an oncologist at the IRCCS San Martino Polyclinic Hospital in Genoa, Italy.

As the authors explain, “PREDICT is a publicly available online tool that helps to predict the individual prognosis of patients with early breast cancer and to show the impact of adjuvant treatments administered after breast cancer surgery.” The tool uses traditional clinical-pathological factors. The authors also point out that the original version of this tool was validated in several datasets of patients with breast cancer. In 2011, it was updated to include HER2 status.

The investigators noted that, although the use of PREDICT is recommended to aid decision-making in the adjuvant setting, its prognostic role in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer who are treated with modern chemotherapy and anti-HER2 therapies – even trastuzumab-based ones – remains unclear.

Therefore, they decided to analyze PREDICT’s prognostic performance using data extracted from the ALTTO trial, the largest adjuvant study ever conducted in the field of HER2-positive early breast cancer. That trial “represented a unique opportunity to investigate the reliability and prognostic performance of PREDICT in women with HER2-positive disease,” according to the investigators. They went on to specify that ALTTO evaluated adjuvant lapatinib plus trastuzumab vs. trastuzumab alone in 8,381 patients – 2,794 of whom were included in their own analysis.

What the analysis found was that, overall, PREDICT underestimated 5-year OS by 6.7%. The observed 5-year OS was 94.7%, and the predicted 5-year OS was 88.0%.

The highest absolute differences were observed for patients with hormone receptor–negative disease, nodal involvement, and large tumor size (13.0%, 15.8%, and 15.3%, respectively),” they wrote. Furthermore, they reported that “the suboptimal performance of this prognostic tool was observed irrespective of type of anti-HER2 treatment, type of chemotherapy regimen, age of the patients at the time of diagnosis, central hormone receptor status, pathological nodal status, and pathological tumor size.”

To potentially explain the reasons for the underestimation of patients’ OS, the authors questioned whether the population used to validate PREDICT accurately mirrored the real-world population of patients with HER2-positive disease treated in the modern era with effective chemotherapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapies. “Moreover, the current standard of care for early breast cancer is even superior to the treatment received by many patients in the ALTTO study. … As such, the discordance between OS estimated by PREDICT and the current real-world OS is expected to be even higher. Therefore,” the researchers concluded, “our results suggest that the current version of PREDICT should be used with caution for prognostication in HER2-positive early breast cancer patients treated in the modern era with effective chemotherapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapies.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from Univadis Italy.

The PREDICT score does not seem to be particularly accurate when it comes to estimating overall survival (OS) in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer who are treated with modern chemotherapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapies. This is the conclusion of an international study published in the journal npj Breast Cancer. The work was supervised by Matteo Lambertini, MD, PhD, an oncologist at the IRCCS San Martino Polyclinic Hospital in Genoa, Italy.

As the authors explain, “PREDICT is a publicly available online tool that helps to predict the individual prognosis of patients with early breast cancer and to show the impact of adjuvant treatments administered after breast cancer surgery.” The tool uses traditional clinical-pathological factors. The authors also point out that the original version of this tool was validated in several datasets of patients with breast cancer. In 2011, it was updated to include HER2 status.

The investigators noted that, although the use of PREDICT is recommended to aid decision-making in the adjuvant setting, its prognostic role in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer who are treated with modern chemotherapy and anti-HER2 therapies – even trastuzumab-based ones – remains unclear.

Therefore, they decided to analyze PREDICT’s prognostic performance using data extracted from the ALTTO trial, the largest adjuvant study ever conducted in the field of HER2-positive early breast cancer. That trial “represented a unique opportunity to investigate the reliability and prognostic performance of PREDICT in women with HER2-positive disease,” according to the investigators. They went on to specify that ALTTO evaluated adjuvant lapatinib plus trastuzumab vs. trastuzumab alone in 8,381 patients – 2,794 of whom were included in their own analysis.

What the analysis found was that, overall, PREDICT underestimated 5-year OS by 6.7%. The observed 5-year OS was 94.7%, and the predicted 5-year OS was 88.0%.

The highest absolute differences were observed for patients with hormone receptor–negative disease, nodal involvement, and large tumor size (13.0%, 15.8%, and 15.3%, respectively),” they wrote. Furthermore, they reported that “the suboptimal performance of this prognostic tool was observed irrespective of type of anti-HER2 treatment, type of chemotherapy regimen, age of the patients at the time of diagnosis, central hormone receptor status, pathological nodal status, and pathological tumor size.”

To potentially explain the reasons for the underestimation of patients’ OS, the authors questioned whether the population used to validate PREDICT accurately mirrored the real-world population of patients with HER2-positive disease treated in the modern era with effective chemotherapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapies. “Moreover, the current standard of care for early breast cancer is even superior to the treatment received by many patients in the ALTTO study. … As such, the discordance between OS estimated by PREDICT and the current real-world OS is expected to be even higher. Therefore,” the researchers concluded, “our results suggest that the current version of PREDICT should be used with caution for prognostication in HER2-positive early breast cancer patients treated in the modern era with effective chemotherapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapies.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from Univadis Italy.

The PREDICT score does not seem to be particularly accurate when it comes to estimating overall survival (OS) in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer who are treated with modern chemotherapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapies. This is the conclusion of an international study published in the journal npj Breast Cancer. The work was supervised by Matteo Lambertini, MD, PhD, an oncologist at the IRCCS San Martino Polyclinic Hospital in Genoa, Italy.

As the authors explain, “PREDICT is a publicly available online tool that helps to predict the individual prognosis of patients with early breast cancer and to show the impact of adjuvant treatments administered after breast cancer surgery.” The tool uses traditional clinical-pathological factors. The authors also point out that the original version of this tool was validated in several datasets of patients with breast cancer. In 2011, it was updated to include HER2 status.

The investigators noted that, although the use of PREDICT is recommended to aid decision-making in the adjuvant setting, its prognostic role in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer who are treated with modern chemotherapy and anti-HER2 therapies – even trastuzumab-based ones – remains unclear.

Therefore, they decided to analyze PREDICT’s prognostic performance using data extracted from the ALTTO trial, the largest adjuvant study ever conducted in the field of HER2-positive early breast cancer. That trial “represented a unique opportunity to investigate the reliability and prognostic performance of PREDICT in women with HER2-positive disease,” according to the investigators. They went on to specify that ALTTO evaluated adjuvant lapatinib plus trastuzumab vs. trastuzumab alone in 8,381 patients – 2,794 of whom were included in their own analysis.

What the analysis found was that, overall, PREDICT underestimated 5-year OS by 6.7%. The observed 5-year OS was 94.7%, and the predicted 5-year OS was 88.0%.

The highest absolute differences were observed for patients with hormone receptor–negative disease, nodal involvement, and large tumor size (13.0%, 15.8%, and 15.3%, respectively),” they wrote. Furthermore, they reported that “the suboptimal performance of this prognostic tool was observed irrespective of type of anti-HER2 treatment, type of chemotherapy regimen, age of the patients at the time of diagnosis, central hormone receptor status, pathological nodal status, and pathological tumor size.”

To potentially explain the reasons for the underestimation of patients’ OS, the authors questioned whether the population used to validate PREDICT accurately mirrored the real-world population of patients with HER2-positive disease treated in the modern era with effective chemotherapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapies. “Moreover, the current standard of care for early breast cancer is even superior to the treatment received by many patients in the ALTTO study. … As such, the discordance between OS estimated by PREDICT and the current real-world OS is expected to be even higher. Therefore,” the researchers concluded, “our results suggest that the current version of PREDICT should be used with caution for prognostication in HER2-positive early breast cancer patients treated in the modern era with effective chemotherapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapies.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from Univadis Italy.

FROM NPJ BREAST CANCER

‘Obesity paradox’ in AFib challenged as mortality climbs with BMI

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) is U-shaped, with the risk highest in those who are underweight or severely obese and lowest in patients defined simply as obese, a registry analysis suggests. It also showed a similar relationship between BMI and risk for new or worsening heart failure (HF).

Mortality bottomed out at a BMI of about 30-35 kg/m2, which suggests that mild obesity was protective, compared even with “normal-weight” or “overweight” BMI. Still, mortality went up sharply from there with rising BMI.

But higher BMI, a surrogate for obesity, apparently didn’t worsen outcomes by itself. The risk for death from any cause at higher obesity levels was found to depend a lot on related risk factors and comorbidities when the analysis controlled for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

The findings suggest an inverse relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in AFib only for patients with BMI less than about 30. They therefore argue against any “obesity paradox” in AFib that posits consistently better survival with increasing levels of obesity, say researchers, based on their analysis of patients with new-onset AFib in the GARFIELD-AF registry.

“It’s common practice now for clinicians to discuss weight within a clinic setting when they’re talking to their AFib patients,” observed Christian Fielder Camm, BM, BCh, University of Oxford (England), and Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, England. So studies suggesting an inverse association between BMI and AFib-related risk can be a concern.

Such studies “seem to suggest that once you’ve got AFib, maintaining a high or very high BMI may in some way be protective – which is contrary to what would seem to make sense and certainly contrary to what our results have shown,” Dr. Camm told this news organization.

“I think that having further evidence now to suggest, actually, that greater BMI is associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality and heart failure helps reframe that discussion at the physician-patient interaction level more clearly, and ensures that we’re able to talk to our patients appropriately about risks associated with BMI and atrial fibrillation,” said Dr. Camm, who is lead author on the analysis published in Open Heart.

“Obesity is a cause of most cardiovascular diseases, but [these] data would support that being overweight or having mild obesity does not increase the risk,” observed Carl J. Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans, La., and the Ochsner Clinical School at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

“At a BMI of 40, it’s very important for them to lose weight for their long-term prognosis,” Dr. Lavie noted, but “at a BMI of 30, the important thing would be to prevent further weight gain. And if they could keep their BMI of 30, they should have a good prognosis. Their prognosis would be particularly good if they didn’t gain weight and put themselves in a more extreme obesity class that is associated with worse risk.”

The current analysis, Dr. Lavie said, “is way better than the AFFIRM study,” which yielded an obesity-paradox report on its patients with AFib about a dozen years ago. “It’s got more data, more numbers, more statistical power,” and breaks BMI into more categories.

That previous analysis based on the influential AFFIRM randomized trial separated its 4,060 patients with AFib into normal (BMI, 18.5-25), overweight (BMI, 25-30), and obese (BMI, > 30) categories, per the convention at the time. It concluded that “obese patients with atrial fibrillation appear to have better long-term outcomes than nonobese patients.”

Bleeding risk on oral anticoagulants

Also noteworthy in the current analysis, variation in BMI didn’t seem to affect mortality or risk for major bleeding or nonhemorrhagic stroke according to choice of oral anticoagulant – whether a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).

“We saw that even in the obese and extremely obese group, all-cause mortality was lower in the group taking NOACs, compared with taking warfarin,” Dr. Camm observed, “which goes against the idea that we would need any kind of dose adjustments for increased BMI.”

Indeed, the report notes, use of NOACs, compared with VKA, was associated with a 23% drop in risk for death among patients who were either normal weight or overweight and also in those who were obese or extremely obese.

Those findings “are basically saying that the NOACs look better than warfarin regardless of weight,” agreed Dr. Lavie. “The problem is that the study is not very powered.”

Whereas the benefits of NOACs, compared to VKA, seem similar for patients with a BMI of 30 or 34, compared with a BMI of 23, for example, “none of the studies has many people with 50 BMI.” Many clinicians “feel uncomfortable giving the same dose of NOAC to somebody who has a 60 BMI,” he said. At least with warfarin, “you can check the INR [international normalized ratio].”

The current analysis included 40,482 patients with recently diagnosed AFib and at least one other stroke risk factor from among the registry’s more than 50,000 patients from 35 countries, enrolled from 2010 to 2016. They were followed for 2 years.

The 703 patients with BMI under 18.5 at AFib diagnosis were classified per World Health Organization definitions as underweight; the 13,095 with BMI 18.5-25 as normal weight; the 15,043 with BMI 25-30 as overweight; the 7,560 with BMI 30-35 as obese; and the 4,081 with BMI above 35 as extremely obese. Their ages averaged 71 years, and 55.6% were men.

BMI effects on different outcomes

Relationships between BMI and all-cause mortality and between BMI and new or worsening HF emerged as U-shaped, the risk climbing with both increasing and decreasing BMI. The nadir BMI for risk was about 30 in the case of mortality and about 25 for new or worsening HF.

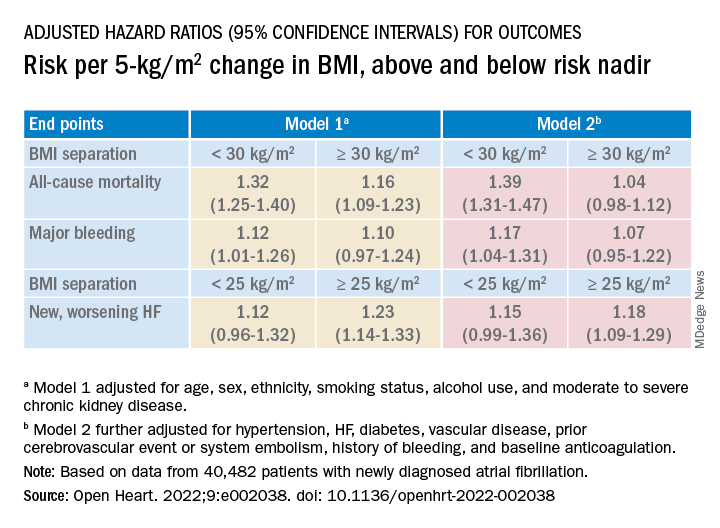

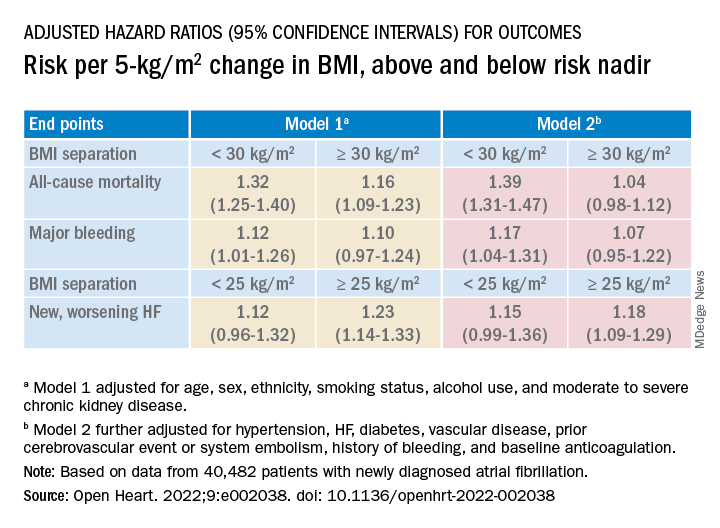

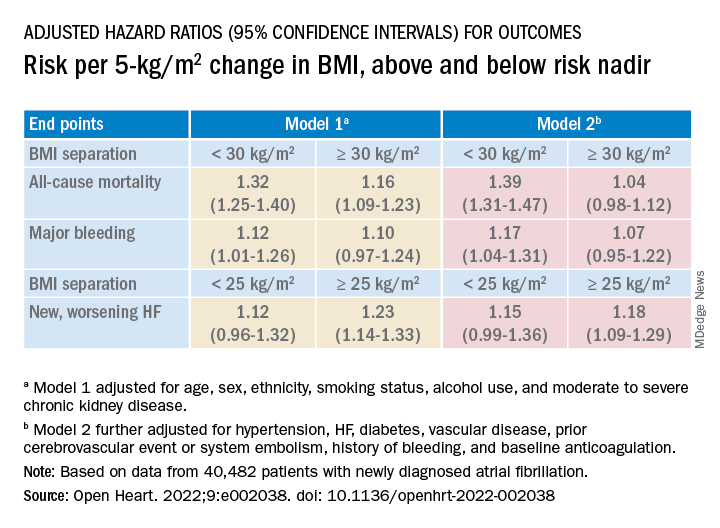

The all-cause mortality risk rose by 32% for every 5 BMI points lower than a BMI of 30, and by 16% for every 5 BMI points higher than 30, in a partially adjusted analysis. The risk for new or worsening HF rose significantly with increasing but not decreasing BMI, and the reverse was observed for the endpoint of major bleeding.

The effect of BMI on all-cause mortality was “substantially attenuated” when the analysis was further adjusted with “likely mediators of any association between BMI and outcomes,” including hypertension, diabetes, HF, cerebrovascular events, and history of bleeding, Dr. Camm said.

That blunted BMI-mortality relationship, he said, “suggests that a lot of the effect is mediated through relatively traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.”

The 2010 AFFIRM analysis by BMI, Dr. Lavie noted, “didn’t even look at the underweight; they actually threw them out.” Yet, such patients with AFib, who tend to be extremely frail or have chronic diseases or conditions other than the arrhythmia, are common. A take-home of the current study is that “the underweight with atrial fibrillation have a really bad prognosis.”

That message isn’t heard as much, he observed, “but is as important as saying that BMI 30 has the best prognosis. The worst prognosis is with the underweight or the really extreme obese.”

Dr. Camm discloses research funding from the British Heart Foundation. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Lavie has previously disclosed serving as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health and DSM Nutritional Products and is the author of “The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier” (Avery, 2014).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) is U-shaped, with the risk highest in those who are underweight or severely obese and lowest in patients defined simply as obese, a registry analysis suggests. It also showed a similar relationship between BMI and risk for new or worsening heart failure (HF).

Mortality bottomed out at a BMI of about 30-35 kg/m2, which suggests that mild obesity was protective, compared even with “normal-weight” or “overweight” BMI. Still, mortality went up sharply from there with rising BMI.

But higher BMI, a surrogate for obesity, apparently didn’t worsen outcomes by itself. The risk for death from any cause at higher obesity levels was found to depend a lot on related risk factors and comorbidities when the analysis controlled for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

The findings suggest an inverse relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in AFib only for patients with BMI less than about 30. They therefore argue against any “obesity paradox” in AFib that posits consistently better survival with increasing levels of obesity, say researchers, based on their analysis of patients with new-onset AFib in the GARFIELD-AF registry.

“It’s common practice now for clinicians to discuss weight within a clinic setting when they’re talking to their AFib patients,” observed Christian Fielder Camm, BM, BCh, University of Oxford (England), and Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, England. So studies suggesting an inverse association between BMI and AFib-related risk can be a concern.

Such studies “seem to suggest that once you’ve got AFib, maintaining a high or very high BMI may in some way be protective – which is contrary to what would seem to make sense and certainly contrary to what our results have shown,” Dr. Camm told this news organization.

“I think that having further evidence now to suggest, actually, that greater BMI is associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality and heart failure helps reframe that discussion at the physician-patient interaction level more clearly, and ensures that we’re able to talk to our patients appropriately about risks associated with BMI and atrial fibrillation,” said Dr. Camm, who is lead author on the analysis published in Open Heart.

“Obesity is a cause of most cardiovascular diseases, but [these] data would support that being overweight or having mild obesity does not increase the risk,” observed Carl J. Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans, La., and the Ochsner Clinical School at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

“At a BMI of 40, it’s very important for them to lose weight for their long-term prognosis,” Dr. Lavie noted, but “at a BMI of 30, the important thing would be to prevent further weight gain. And if they could keep their BMI of 30, they should have a good prognosis. Their prognosis would be particularly good if they didn’t gain weight and put themselves in a more extreme obesity class that is associated with worse risk.”

The current analysis, Dr. Lavie said, “is way better than the AFFIRM study,” which yielded an obesity-paradox report on its patients with AFib about a dozen years ago. “It’s got more data, more numbers, more statistical power,” and breaks BMI into more categories.

That previous analysis based on the influential AFFIRM randomized trial separated its 4,060 patients with AFib into normal (BMI, 18.5-25), overweight (BMI, 25-30), and obese (BMI, > 30) categories, per the convention at the time. It concluded that “obese patients with atrial fibrillation appear to have better long-term outcomes than nonobese patients.”

Bleeding risk on oral anticoagulants

Also noteworthy in the current analysis, variation in BMI didn’t seem to affect mortality or risk for major bleeding or nonhemorrhagic stroke according to choice of oral anticoagulant – whether a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).

“We saw that even in the obese and extremely obese group, all-cause mortality was lower in the group taking NOACs, compared with taking warfarin,” Dr. Camm observed, “which goes against the idea that we would need any kind of dose adjustments for increased BMI.”

Indeed, the report notes, use of NOACs, compared with VKA, was associated with a 23% drop in risk for death among patients who were either normal weight or overweight and also in those who were obese or extremely obese.

Those findings “are basically saying that the NOACs look better than warfarin regardless of weight,” agreed Dr. Lavie. “The problem is that the study is not very powered.”

Whereas the benefits of NOACs, compared to VKA, seem similar for patients with a BMI of 30 or 34, compared with a BMI of 23, for example, “none of the studies has many people with 50 BMI.” Many clinicians “feel uncomfortable giving the same dose of NOAC to somebody who has a 60 BMI,” he said. At least with warfarin, “you can check the INR [international normalized ratio].”

The current analysis included 40,482 patients with recently diagnosed AFib and at least one other stroke risk factor from among the registry’s more than 50,000 patients from 35 countries, enrolled from 2010 to 2016. They were followed for 2 years.

The 703 patients with BMI under 18.5 at AFib diagnosis were classified per World Health Organization definitions as underweight; the 13,095 with BMI 18.5-25 as normal weight; the 15,043 with BMI 25-30 as overweight; the 7,560 with BMI 30-35 as obese; and the 4,081 with BMI above 35 as extremely obese. Their ages averaged 71 years, and 55.6% were men.

BMI effects on different outcomes

Relationships between BMI and all-cause mortality and between BMI and new or worsening HF emerged as U-shaped, the risk climbing with both increasing and decreasing BMI. The nadir BMI for risk was about 30 in the case of mortality and about 25 for new or worsening HF.

The all-cause mortality risk rose by 32% for every 5 BMI points lower than a BMI of 30, and by 16% for every 5 BMI points higher than 30, in a partially adjusted analysis. The risk for new or worsening HF rose significantly with increasing but not decreasing BMI, and the reverse was observed for the endpoint of major bleeding.

The effect of BMI on all-cause mortality was “substantially attenuated” when the analysis was further adjusted with “likely mediators of any association between BMI and outcomes,” including hypertension, diabetes, HF, cerebrovascular events, and history of bleeding, Dr. Camm said.

That blunted BMI-mortality relationship, he said, “suggests that a lot of the effect is mediated through relatively traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.”

The 2010 AFFIRM analysis by BMI, Dr. Lavie noted, “didn’t even look at the underweight; they actually threw them out.” Yet, such patients with AFib, who tend to be extremely frail or have chronic diseases or conditions other than the arrhythmia, are common. A take-home of the current study is that “the underweight with atrial fibrillation have a really bad prognosis.”

That message isn’t heard as much, he observed, “but is as important as saying that BMI 30 has the best prognosis. The worst prognosis is with the underweight or the really extreme obese.”

Dr. Camm discloses research funding from the British Heart Foundation. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Lavie has previously disclosed serving as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health and DSM Nutritional Products and is the author of “The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier” (Avery, 2014).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) is U-shaped, with the risk highest in those who are underweight or severely obese and lowest in patients defined simply as obese, a registry analysis suggests. It also showed a similar relationship between BMI and risk for new or worsening heart failure (HF).

Mortality bottomed out at a BMI of about 30-35 kg/m2, which suggests that mild obesity was protective, compared even with “normal-weight” or “overweight” BMI. Still, mortality went up sharply from there with rising BMI.

But higher BMI, a surrogate for obesity, apparently didn’t worsen outcomes by itself. The risk for death from any cause at higher obesity levels was found to depend a lot on related risk factors and comorbidities when the analysis controlled for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

The findings suggest an inverse relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in AFib only for patients with BMI less than about 30. They therefore argue against any “obesity paradox” in AFib that posits consistently better survival with increasing levels of obesity, say researchers, based on their analysis of patients with new-onset AFib in the GARFIELD-AF registry.

“It’s common practice now for clinicians to discuss weight within a clinic setting when they’re talking to their AFib patients,” observed Christian Fielder Camm, BM, BCh, University of Oxford (England), and Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, England. So studies suggesting an inverse association between BMI and AFib-related risk can be a concern.

Such studies “seem to suggest that once you’ve got AFib, maintaining a high or very high BMI may in some way be protective – which is contrary to what would seem to make sense and certainly contrary to what our results have shown,” Dr. Camm told this news organization.

“I think that having further evidence now to suggest, actually, that greater BMI is associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality and heart failure helps reframe that discussion at the physician-patient interaction level more clearly, and ensures that we’re able to talk to our patients appropriately about risks associated with BMI and atrial fibrillation,” said Dr. Camm, who is lead author on the analysis published in Open Heart.

“Obesity is a cause of most cardiovascular diseases, but [these] data would support that being overweight or having mild obesity does not increase the risk,” observed Carl J. Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans, La., and the Ochsner Clinical School at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

“At a BMI of 40, it’s very important for them to lose weight for their long-term prognosis,” Dr. Lavie noted, but “at a BMI of 30, the important thing would be to prevent further weight gain. And if they could keep their BMI of 30, they should have a good prognosis. Their prognosis would be particularly good if they didn’t gain weight and put themselves in a more extreme obesity class that is associated with worse risk.”

The current analysis, Dr. Lavie said, “is way better than the AFFIRM study,” which yielded an obesity-paradox report on its patients with AFib about a dozen years ago. “It’s got more data, more numbers, more statistical power,” and breaks BMI into more categories.

That previous analysis based on the influential AFFIRM randomized trial separated its 4,060 patients with AFib into normal (BMI, 18.5-25), overweight (BMI, 25-30), and obese (BMI, > 30) categories, per the convention at the time. It concluded that “obese patients with atrial fibrillation appear to have better long-term outcomes than nonobese patients.”

Bleeding risk on oral anticoagulants

Also noteworthy in the current analysis, variation in BMI didn’t seem to affect mortality or risk for major bleeding or nonhemorrhagic stroke according to choice of oral anticoagulant – whether a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).

“We saw that even in the obese and extremely obese group, all-cause mortality was lower in the group taking NOACs, compared with taking warfarin,” Dr. Camm observed, “which goes against the idea that we would need any kind of dose adjustments for increased BMI.”

Indeed, the report notes, use of NOACs, compared with VKA, was associated with a 23% drop in risk for death among patients who were either normal weight or overweight and also in those who were obese or extremely obese.

Those findings “are basically saying that the NOACs look better than warfarin regardless of weight,” agreed Dr. Lavie. “The problem is that the study is not very powered.”

Whereas the benefits of NOACs, compared to VKA, seem similar for patients with a BMI of 30 or 34, compared with a BMI of 23, for example, “none of the studies has many people with 50 BMI.” Many clinicians “feel uncomfortable giving the same dose of NOAC to somebody who has a 60 BMI,” he said. At least with warfarin, “you can check the INR [international normalized ratio].”

The current analysis included 40,482 patients with recently diagnosed AFib and at least one other stroke risk factor from among the registry’s more than 50,000 patients from 35 countries, enrolled from 2010 to 2016. They were followed for 2 years.

The 703 patients with BMI under 18.5 at AFib diagnosis were classified per World Health Organization definitions as underweight; the 13,095 with BMI 18.5-25 as normal weight; the 15,043 with BMI 25-30 as overweight; the 7,560 with BMI 30-35 as obese; and the 4,081 with BMI above 35 as extremely obese. Their ages averaged 71 years, and 55.6% were men.

BMI effects on different outcomes

Relationships between BMI and all-cause mortality and between BMI and new or worsening HF emerged as U-shaped, the risk climbing with both increasing and decreasing BMI. The nadir BMI for risk was about 30 in the case of mortality and about 25 for new or worsening HF.

The all-cause mortality risk rose by 32% for every 5 BMI points lower than a BMI of 30, and by 16% for every 5 BMI points higher than 30, in a partially adjusted analysis. The risk for new or worsening HF rose significantly with increasing but not decreasing BMI, and the reverse was observed for the endpoint of major bleeding.

The effect of BMI on all-cause mortality was “substantially attenuated” when the analysis was further adjusted with “likely mediators of any association between BMI and outcomes,” including hypertension, diabetes, HF, cerebrovascular events, and history of bleeding, Dr. Camm said.

That blunted BMI-mortality relationship, he said, “suggests that a lot of the effect is mediated through relatively traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.”

The 2010 AFFIRM analysis by BMI, Dr. Lavie noted, “didn’t even look at the underweight; they actually threw them out.” Yet, such patients with AFib, who tend to be extremely frail or have chronic diseases or conditions other than the arrhythmia, are common. A take-home of the current study is that “the underweight with atrial fibrillation have a really bad prognosis.”

That message isn’t heard as much, he observed, “but is as important as saying that BMI 30 has the best prognosis. The worst prognosis is with the underweight or the really extreme obese.”

Dr. Camm discloses research funding from the British Heart Foundation. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Lavie has previously disclosed serving as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health and DSM Nutritional Products and is the author of “The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier” (Avery, 2014).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM OPEN HEART

Strength training overcomes bone effects of vegan diet

People who maintain a vegan diet show significant deficits in bone microarchitecture, compared with omnivores; however, resistance training not only appears to improve those deficits but may have a stronger effect in vegans, suggesting an important strategy in maintaining bone health with a vegan diet.

“We expected better bone structure in both vegans and omnivores who reported resistance training,” first author Robert Wakolbinger-Habel, MD, PhD, of St. Vincent Hospital Vienna and the Medical University of Vienna, said in an interview.

“However, we expected [there would still be] differences in structure between vegans and omnivores [who practiced resistance training], as previous literature reported higher fracture rates in vegans,” he said. “Still, the positive message is that ‘pumping iron’ could counterbalance these differences between vegans and omnivores.”

The research was published online in The Endocrine Society’s Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Exercise significantly impacts bone health in vegans

The potential effects of the plant-based vegan diet on bone health have been reported in studies linking the diet to an increased risk of fractures and lower bone mineral density (BMD), with common theories including lower bone- and muscle-building protein in vegan diets.

However, most previous studies have not considered other key factors, such as the effects of exercise, the authors noted.

“While previous studies on bone health in vegans only took BMD, biochemical and nutritional parameters into account, they did not consider the significant effects of physical activity,” they wrote.

“By ignoring these effects, important factors influencing bone health are neglected.”

For the study, 88 participants were enrolled in Vienna, with vegan participants recruited with the help of the Austrian Vegan Society.

Importantly, the study documented participants’ bone microarchitecture, a key measure of bone strength that has also not been previously investigated in vegans, using high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT.

Inclusion criteria included maintaining an omnivore diet of meat and plant-based foods or a vegan diet for at least 5 years, not being underweight or obese (body mass index [BMI], 18.5-30 kg/m2), being age 30-50 years, and being premenopausal.

Of the participants, 43 were vegan and 45 were omnivores, with generally equal ratios of men and women.

Vegan bone deficits disappear with strength training

Overall, compared with omnivores, the vegan group showed significant deficits in 7 of 14 measures of BMI-adjusted trabecular and cortical structure (all P < .05).

Among participants who reported no resistance training, vegans still showed significant decreases in bone microarchitecture, compared with omnivores, including radius trabecular BMD, radius trabecular bone volume fraction, and other tibial and cortical bone microarchitecture measures.

However, among those who did report progressive resistant training (20 vegans and 25 omnivores), defined as using machines, free weights, or bodyweight resistance exercises at least once a week, those differences disappeared and there were no significant differences in BMI-adjusted bone microarchitecture between vegans and omnivores after the 5 years.

Of note, no significant differences in bone microarchitecture were observed between those who performed exclusively aerobic activities and those who reported no sports activities in the vegan or omnivore group.

Based on the findings, “other types of exercise such as aerobics, cycling, etc, would not be sufficient for a similar positive effect on bone [as resistance training],” Dr. Wakolbinger-Habel said.

Although the findings suggest that resistance training seemed to allow vegans to “catch up” with omnivores in terms of bone microarchitecture, Dr. Wakolbinger-Habel cautioned that a study limitation is the relatively low number of participants.

“The absolute numbers suggest that in vegans the differences, and the relative effect, respectively of resistance training might be larger,” he said. “However, the number of participants in the subgroups is small and it is still an observational study, so we need to be careful in drawing causal conclusions.”

Serum bone markers were within normal ranges across all subgroups. And although there were some correlations between nutrient intake and bone microarchitecture among vegans who did and did not practice resistance training, no conclusions could be drawn from that data, the authors noted.

“Based on our data, the structural [differences between vegans and omnivores] cannot solely be explained by deficits in certain nutrients according to lifestyle,” the authors concluded.

Mechanisms

The mechanisms by which progressive resistance training could result in the benefits include that mechanical loads trigger stimulation of key pathways involved in bone formation, or mechanotransduction, the authors explained.

The unique effects have been observed in other studies, including one study showing that, among young adult runners, the addition of resistance training once a week was associated with significantly greater BMD.

“Veganism is a global trend with strongly increasing numbers of people worldwide adhering to a purely plant-based diet,” first author Christian Muschitz, MD, also of St. Vincent Hospital Vienna and the Medical University of Vienna, said in a press statement.

“Our study showed resistance training offsets diminished bone structure in vegan people when compared to omnivores,” he said.

Dr. Wakolbinger-Habel recommended that, based on the findings, “exercise, including resistance training, should be strongly advocated [for vegans], I would say, at least two times per week.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who maintain a vegan diet show significant deficits in bone microarchitecture, compared with omnivores; however, resistance training not only appears to improve those deficits but may have a stronger effect in vegans, suggesting an important strategy in maintaining bone health with a vegan diet.

“We expected better bone structure in both vegans and omnivores who reported resistance training,” first author Robert Wakolbinger-Habel, MD, PhD, of St. Vincent Hospital Vienna and the Medical University of Vienna, said in an interview.

“However, we expected [there would still be] differences in structure between vegans and omnivores [who practiced resistance training], as previous literature reported higher fracture rates in vegans,” he said. “Still, the positive message is that ‘pumping iron’ could counterbalance these differences between vegans and omnivores.”

The research was published online in The Endocrine Society’s Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Exercise significantly impacts bone health in vegans

The potential effects of the plant-based vegan diet on bone health have been reported in studies linking the diet to an increased risk of fractures and lower bone mineral density (BMD), with common theories including lower bone- and muscle-building protein in vegan diets.

However, most previous studies have not considered other key factors, such as the effects of exercise, the authors noted.

“While previous studies on bone health in vegans only took BMD, biochemical and nutritional parameters into account, they did not consider the significant effects of physical activity,” they wrote.

“By ignoring these effects, important factors influencing bone health are neglected.”

For the study, 88 participants were enrolled in Vienna, with vegan participants recruited with the help of the Austrian Vegan Society.

Importantly, the study documented participants’ bone microarchitecture, a key measure of bone strength that has also not been previously investigated in vegans, using high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT.

Inclusion criteria included maintaining an omnivore diet of meat and plant-based foods or a vegan diet for at least 5 years, not being underweight or obese (body mass index [BMI], 18.5-30 kg/m2), being age 30-50 years, and being premenopausal.

Of the participants, 43 were vegan and 45 were omnivores, with generally equal ratios of men and women.

Vegan bone deficits disappear with strength training

Overall, compared with omnivores, the vegan group showed significant deficits in 7 of 14 measures of BMI-adjusted trabecular and cortical structure (all P < .05).

Among participants who reported no resistance training, vegans still showed significant decreases in bone microarchitecture, compared with omnivores, including radius trabecular BMD, radius trabecular bone volume fraction, and other tibial and cortical bone microarchitecture measures.

However, among those who did report progressive resistant training (20 vegans and 25 omnivores), defined as using machines, free weights, or bodyweight resistance exercises at least once a week, those differences disappeared and there were no significant differences in BMI-adjusted bone microarchitecture between vegans and omnivores after the 5 years.

Of note, no significant differences in bone microarchitecture were observed between those who performed exclusively aerobic activities and those who reported no sports activities in the vegan or omnivore group.

Based on the findings, “other types of exercise such as aerobics, cycling, etc, would not be sufficient for a similar positive effect on bone [as resistance training],” Dr. Wakolbinger-Habel said.

Although the findings suggest that resistance training seemed to allow vegans to “catch up” with omnivores in terms of bone microarchitecture, Dr. Wakolbinger-Habel cautioned that a study limitation is the relatively low number of participants.

“The absolute numbers suggest that in vegans the differences, and the relative effect, respectively of resistance training might be larger,” he said. “However, the number of participants in the subgroups is small and it is still an observational study, so we need to be careful in drawing causal conclusions.”

Serum bone markers were within normal ranges across all subgroups. And although there were some correlations between nutrient intake and bone microarchitecture among vegans who did and did not practice resistance training, no conclusions could be drawn from that data, the authors noted.

“Based on our data, the structural [differences between vegans and omnivores] cannot solely be explained by deficits in certain nutrients according to lifestyle,” the authors concluded.

Mechanisms

The mechanisms by which progressive resistance training could result in the benefits include that mechanical loads trigger stimulation of key pathways involved in bone formation, or mechanotransduction, the authors explained.

The unique effects have been observed in other studies, including one study showing that, among young adult runners, the addition of resistance training once a week was associated with significantly greater BMD.

“Veganism is a global trend with strongly increasing numbers of people worldwide adhering to a purely plant-based diet,” first author Christian Muschitz, MD, also of St. Vincent Hospital Vienna and the Medical University of Vienna, said in a press statement.

“Our study showed resistance training offsets diminished bone structure in vegan people when compared to omnivores,” he said.

Dr. Wakolbinger-Habel recommended that, based on the findings, “exercise, including resistance training, should be strongly advocated [for vegans], I would say, at least two times per week.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who maintain a vegan diet show significant deficits in bone microarchitecture, compared with omnivores; however, resistance training not only appears to improve those deficits but may have a stronger effect in vegans, suggesting an important strategy in maintaining bone health with a vegan diet.

“We expected better bone structure in both vegans and omnivores who reported resistance training,” first author Robert Wakolbinger-Habel, MD, PhD, of St. Vincent Hospital Vienna and the Medical University of Vienna, said in an interview.

“However, we expected [there would still be] differences in structure between vegans and omnivores [who practiced resistance training], as previous literature reported higher fracture rates in vegans,” he said. “Still, the positive message is that ‘pumping iron’ could counterbalance these differences between vegans and omnivores.”

The research was published online in The Endocrine Society’s Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Exercise significantly impacts bone health in vegans

The potential effects of the plant-based vegan diet on bone health have been reported in studies linking the diet to an increased risk of fractures and lower bone mineral density (BMD), with common theories including lower bone- and muscle-building protein in vegan diets.

However, most previous studies have not considered other key factors, such as the effects of exercise, the authors noted.

“While previous studies on bone health in vegans only took BMD, biochemical and nutritional parameters into account, they did not consider the significant effects of physical activity,” they wrote.

“By ignoring these effects, important factors influencing bone health are neglected.”

For the study, 88 participants were enrolled in Vienna, with vegan participants recruited with the help of the Austrian Vegan Society.

Importantly, the study documented participants’ bone microarchitecture, a key measure of bone strength that has also not been previously investigated in vegans, using high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT.

Inclusion criteria included maintaining an omnivore diet of meat and plant-based foods or a vegan diet for at least 5 years, not being underweight or obese (body mass index [BMI], 18.5-30 kg/m2), being age 30-50 years, and being premenopausal.

Of the participants, 43 were vegan and 45 were omnivores, with generally equal ratios of men and women.

Vegan bone deficits disappear with strength training

Overall, compared with omnivores, the vegan group showed significant deficits in 7 of 14 measures of BMI-adjusted trabecular and cortical structure (all P < .05).

Among participants who reported no resistance training, vegans still showed significant decreases in bone microarchitecture, compared with omnivores, including radius trabecular BMD, radius trabecular bone volume fraction, and other tibial and cortical bone microarchitecture measures.

However, among those who did report progressive resistant training (20 vegans and 25 omnivores), defined as using machines, free weights, or bodyweight resistance exercises at least once a week, those differences disappeared and there were no significant differences in BMI-adjusted bone microarchitecture between vegans and omnivores after the 5 years.

Of note, no significant differences in bone microarchitecture were observed between those who performed exclusively aerobic activities and those who reported no sports activities in the vegan or omnivore group.

Based on the findings, “other types of exercise such as aerobics, cycling, etc, would not be sufficient for a similar positive effect on bone [as resistance training],” Dr. Wakolbinger-Habel said.

Although the findings suggest that resistance training seemed to allow vegans to “catch up” with omnivores in terms of bone microarchitecture, Dr. Wakolbinger-Habel cautioned that a study limitation is the relatively low number of participants.

“The absolute numbers suggest that in vegans the differences, and the relative effect, respectively of resistance training might be larger,” he said. “However, the number of participants in the subgroups is small and it is still an observational study, so we need to be careful in drawing causal conclusions.”

Serum bone markers were within normal ranges across all subgroups. And although there were some correlations between nutrient intake and bone microarchitecture among vegans who did and did not practice resistance training, no conclusions could be drawn from that data, the authors noted.

“Based on our data, the structural [differences between vegans and omnivores] cannot solely be explained by deficits in certain nutrients according to lifestyle,” the authors concluded.

Mechanisms

The mechanisms by which progressive resistance training could result in the benefits include that mechanical loads trigger stimulation of key pathways involved in bone formation, or mechanotransduction, the authors explained.

The unique effects have been observed in other studies, including one study showing that, among young adult runners, the addition of resistance training once a week was associated with significantly greater BMD.

“Veganism is a global trend with strongly increasing numbers of people worldwide adhering to a purely plant-based diet,” first author Christian Muschitz, MD, also of St. Vincent Hospital Vienna and the Medical University of Vienna, said in a press statement.

“Our study showed resistance training offsets diminished bone structure in vegan people when compared to omnivores,” he said.

Dr. Wakolbinger-Habel recommended that, based on the findings, “exercise, including resistance training, should be strongly advocated [for vegans], I would say, at least two times per week.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM

Patients who won’t pay: What’s your recourse?

Owing to the pandemic, job loss, and the possible loss of health insurance, patients have had more difficulty managing copays, coinsurance, and deductibles, not to mention other out-of-pocket health care charges.

“Many of our patients have lost their jobs or have had their hours cut back, and as a result, they are struggling to make ends meet,” said Ahmad Chaudhry, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon in Lexington, Ky. “However, we cannot continue to provide care if our patients do not pay their bills.”

This news organization asked physicians what they do when their patients don’t pay. About 43% said that they continue to treat them and develop a payment plan; 13% send their bill to collections; 12% continue their care and write off their balance, and 25% choose other actions. Only 8% of physicians drop patients if they don’t pay.

Because you need to pay your own bills, what can you do about nonpaying patients?

Start with price transparency

In the past, patients never knew what their lab work or a chest EKG would cost because it wasn’t listed anywhere, and it was usually more than expected. Because of new legislation concerning health care price transparency, hospitals, health plans, and insurers must pony up with the actual fees, making them transparent to patients. Physician practices should follow suit and keep prices transparent too. Patients are more likely to pay their bills when prepared for the expense.

Patients with insurance often don’t know what they’ll be paying for their visit or their tests because they don’t know how much insurance will cover and what will be left for them to pay. Also, they may not know if they’ve met their deductible yet so they’re unsure whether insurance will even kick in. And patients without insurance still need to know what their costs will be upfront.

According to 10 insights from the Primary Care Consumer Choice Survey, 74% of health care consumers were willing to pay a $50 out-of-pocket charge to know the cost of their primary care visit.

Provide payment plans

Many patients have always needed payment plans. It’s one thing to post a sign at check-in telling patients that all monies are due at the time of service, but it’s another reality for a patient who can’t fork over the $250 charge they just unexpectedly spent in your office.

Discover Financial Services recently ran a survey, with results presented in the press release Americans are Delaying Non-Emergency Medical Care in Higher Numbers than Last Year, and found that many Americans with medical debt are delaying nonemergency medical care. For example, they put off seeing a specialist (52%), seeing a doctor for sickness (41%), and undergoing treatment plans recommended by their doctor (31%).

Turning an account over to collections should be a last resort. In addition, agencies typically charge 30%-40% of the total collected off the top.

Though collecting that amount is better than nothing, using a collection agency may have unexpected consequences. For instance, you’re trusting the agency you hire to collect to represent you and act on your practice’s behalf. If they’re rude or their tactics are harsh in the eyes of the patient or their relatives, it’s your reputation that is on the line.

Rather than use a collection agency, you could collect the payments yourself. When a patient fails to pay within about 3 months, begin mailing statements from the office, followed by firm but generous phone calls trying to collect. Industry estimates put the average cost of sending an invoice, including staff labor, printing, and postage, at about $35 per mailer. Some practices combat the added costs by offering a 20% prompt-pay discount. Offering payment plans is another option that helps garner eventual payment. Plus, practices should direct patients to third-party lenders such as CareCredit for larger bills.

On occasion, some small practices may allow a swap, such as allowing a patient to provide a service such as plumbing, electrical, or painting in exchange for working off the bill. Though it’s not ideal when it comes to finances, you may find it can work in a pinch for a cash-strapped patient. Make sure to keep records of what bills the patient’s work goes toward.

It often helps to incentivize your billing staff to follow up regularly, with various suggestions and tactics, to get patients to pay their bills. The incentive amount you offer will probably be less than if you had to use a collection agency.

Have a payment policy

Because your practice’s primary job is caring for patients’ physical and emotional needs, payment collection without coming off as insensitive can be tricky. “We understand these are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to work with our patients,” said Dr. Chaudhry. Having a written payment policy can help build the bridge. A policy lets patients know what they can expect and can help prevent surprises over what occurs in the event of nonpayment. Your written policy should include:

- When payment is due.

- How the practice handles copays and deductibles.

- What forms of payment are accepted.

- Your policy regarding nonpayment.

Why patients don’t pay

A 2021 Healthcare Consumer Experience Study from Cedar found that medical bills are a source of anxiety and frustration for most patients, affecting their financial experience. More than half of the respondents said that paying a medical bill is stressful. Complicating matters, many health care practices rely on outdated payment systems, which may not provide patients with a clear view of what they owe and how to pay it.

The study found that 53% of respondents find understanding their plan’s coverage and benefits stressful, and 37% of patients won’t pay their bill if they can’t understand it.

People may think the patient is trying to get out of paying, which, of course, is sometimes true, but most of the time they want to pay, concluded the study. Most patients need a better explanation, communication, and accurate accounting of their out-of-pocket costs.

What can doctors do?

If you’re a physician who regularly sees patients who have problems paying their bills, you can take a few steps to minimize the financial impact on your practice:

- Bill the patient’s insurance directly to ensure you receive at least partial payment.

- Keep adequate records of services in case you need to pursue legal action.

- “Be understanding and flexible when it comes to payment arrangements, as this can often be the difference between getting paid and not getting paid at all,” said Dr. Chaudhry.

Distance yourself

When discussing payment policies, physicians should try to distance themselves from the actual collection process as much as possible. Well-meaning physicians often tell patients things like they can “figure something out “ financially or “work them in” during a scheduling conflict, but that often undermines the authority and credibility of the practice’s office staff. Plus, it teaches patients they can get their way if they work on the doctor’s soft spot – something you don’t want to encourage.

By following some of these measures, you can help ensure that your practice continues to thrive despite the challenges posed by nonpaying patients.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Owing to the pandemic, job loss, and the possible loss of health insurance, patients have had more difficulty managing copays, coinsurance, and deductibles, not to mention other out-of-pocket health care charges.

“Many of our patients have lost their jobs or have had their hours cut back, and as a result, they are struggling to make ends meet,” said Ahmad Chaudhry, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon in Lexington, Ky. “However, we cannot continue to provide care if our patients do not pay their bills.”

This news organization asked physicians what they do when their patients don’t pay. About 43% said that they continue to treat them and develop a payment plan; 13% send their bill to collections; 12% continue their care and write off their balance, and 25% choose other actions. Only 8% of physicians drop patients if they don’t pay.

Because you need to pay your own bills, what can you do about nonpaying patients?

Start with price transparency

In the past, patients never knew what their lab work or a chest EKG would cost because it wasn’t listed anywhere, and it was usually more than expected. Because of new legislation concerning health care price transparency, hospitals, health plans, and insurers must pony up with the actual fees, making them transparent to patients. Physician practices should follow suit and keep prices transparent too. Patients are more likely to pay their bills when prepared for the expense.

Patients with insurance often don’t know what they’ll be paying for their visit or their tests because they don’t know how much insurance will cover and what will be left for them to pay. Also, they may not know if they’ve met their deductible yet so they’re unsure whether insurance will even kick in. And patients without insurance still need to know what their costs will be upfront.

According to 10 insights from the Primary Care Consumer Choice Survey, 74% of health care consumers were willing to pay a $50 out-of-pocket charge to know the cost of their primary care visit.

Provide payment plans

Many patients have always needed payment plans. It’s one thing to post a sign at check-in telling patients that all monies are due at the time of service, but it’s another reality for a patient who can’t fork over the $250 charge they just unexpectedly spent in your office.

Discover Financial Services recently ran a survey, with results presented in the press release Americans are Delaying Non-Emergency Medical Care in Higher Numbers than Last Year, and found that many Americans with medical debt are delaying nonemergency medical care. For example, they put off seeing a specialist (52%), seeing a doctor for sickness (41%), and undergoing treatment plans recommended by their doctor (31%).

Turning an account over to collections should be a last resort. In addition, agencies typically charge 30%-40% of the total collected off the top.

Though collecting that amount is better than nothing, using a collection agency may have unexpected consequences. For instance, you’re trusting the agency you hire to collect to represent you and act on your practice’s behalf. If they’re rude or their tactics are harsh in the eyes of the patient or their relatives, it’s your reputation that is on the line.

Rather than use a collection agency, you could collect the payments yourself. When a patient fails to pay within about 3 months, begin mailing statements from the office, followed by firm but generous phone calls trying to collect. Industry estimates put the average cost of sending an invoice, including staff labor, printing, and postage, at about $35 per mailer. Some practices combat the added costs by offering a 20% prompt-pay discount. Offering payment plans is another option that helps garner eventual payment. Plus, practices should direct patients to third-party lenders such as CareCredit for larger bills.

On occasion, some small practices may allow a swap, such as allowing a patient to provide a service such as plumbing, electrical, or painting in exchange for working off the bill. Though it’s not ideal when it comes to finances, you may find it can work in a pinch for a cash-strapped patient. Make sure to keep records of what bills the patient’s work goes toward.

It often helps to incentivize your billing staff to follow up regularly, with various suggestions and tactics, to get patients to pay their bills. The incentive amount you offer will probably be less than if you had to use a collection agency.

Have a payment policy

Because your practice’s primary job is caring for patients’ physical and emotional needs, payment collection without coming off as insensitive can be tricky. “We understand these are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to work with our patients,” said Dr. Chaudhry. Having a written payment policy can help build the bridge. A policy lets patients know what they can expect and can help prevent surprises over what occurs in the event of nonpayment. Your written policy should include:

- When payment is due.

- How the practice handles copays and deductibles.

- What forms of payment are accepted.

- Your policy regarding nonpayment.

Why patients don’t pay

A 2021 Healthcare Consumer Experience Study from Cedar found that medical bills are a source of anxiety and frustration for most patients, affecting their financial experience. More than half of the respondents said that paying a medical bill is stressful. Complicating matters, many health care practices rely on outdated payment systems, which may not provide patients with a clear view of what they owe and how to pay it.

The study found that 53% of respondents find understanding their plan’s coverage and benefits stressful, and 37% of patients won’t pay their bill if they can’t understand it.

People may think the patient is trying to get out of paying, which, of course, is sometimes true, but most of the time they want to pay, concluded the study. Most patients need a better explanation, communication, and accurate accounting of their out-of-pocket costs.

What can doctors do?

If you’re a physician who regularly sees patients who have problems paying their bills, you can take a few steps to minimize the financial impact on your practice:

- Bill the patient’s insurance directly to ensure you receive at least partial payment.

- Keep adequate records of services in case you need to pursue legal action.

- “Be understanding and flexible when it comes to payment arrangements, as this can often be the difference between getting paid and not getting paid at all,” said Dr. Chaudhry.

Distance yourself

When discussing payment policies, physicians should try to distance themselves from the actual collection process as much as possible. Well-meaning physicians often tell patients things like they can “figure something out “ financially or “work them in” during a scheduling conflict, but that often undermines the authority and credibility of the practice’s office staff. Plus, it teaches patients they can get their way if they work on the doctor’s soft spot – something you don’t want to encourage.

By following some of these measures, you can help ensure that your practice continues to thrive despite the challenges posed by nonpaying patients.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Owing to the pandemic, job loss, and the possible loss of health insurance, patients have had more difficulty managing copays, coinsurance, and deductibles, not to mention other out-of-pocket health care charges.

“Many of our patients have lost their jobs or have had their hours cut back, and as a result, they are struggling to make ends meet,” said Ahmad Chaudhry, MD, a cardiothoracic surgeon in Lexington, Ky. “However, we cannot continue to provide care if our patients do not pay their bills.”

This news organization asked physicians what they do when their patients don’t pay. About 43% said that they continue to treat them and develop a payment plan; 13% send their bill to collections; 12% continue their care and write off their balance, and 25% choose other actions. Only 8% of physicians drop patients if they don’t pay.

Because you need to pay your own bills, what can you do about nonpaying patients?

Start with price transparency

In the past, patients never knew what their lab work or a chest EKG would cost because it wasn’t listed anywhere, and it was usually more than expected. Because of new legislation concerning health care price transparency, hospitals, health plans, and insurers must pony up with the actual fees, making them transparent to patients. Physician practices should follow suit and keep prices transparent too. Patients are more likely to pay their bills when prepared for the expense.

Patients with insurance often don’t know what they’ll be paying for their visit or their tests because they don’t know how much insurance will cover and what will be left for them to pay. Also, they may not know if they’ve met their deductible yet so they’re unsure whether insurance will even kick in. And patients without insurance still need to know what their costs will be upfront.

According to 10 insights from the Primary Care Consumer Choice Survey, 74% of health care consumers were willing to pay a $50 out-of-pocket charge to know the cost of their primary care visit.

Provide payment plans

Many patients have always needed payment plans. It’s one thing to post a sign at check-in telling patients that all monies are due at the time of service, but it’s another reality for a patient who can’t fork over the $250 charge they just unexpectedly spent in your office.

Discover Financial Services recently ran a survey, with results presented in the press release Americans are Delaying Non-Emergency Medical Care in Higher Numbers than Last Year, and found that many Americans with medical debt are delaying nonemergency medical care. For example, they put off seeing a specialist (52%), seeing a doctor for sickness (41%), and undergoing treatment plans recommended by their doctor (31%).

Turning an account over to collections should be a last resort. In addition, agencies typically charge 30%-40% of the total collected off the top.

Though collecting that amount is better than nothing, using a collection agency may have unexpected consequences. For instance, you’re trusting the agency you hire to collect to represent you and act on your practice’s behalf. If they’re rude or their tactics are harsh in the eyes of the patient or their relatives, it’s your reputation that is on the line.

Rather than use a collection agency, you could collect the payments yourself. When a patient fails to pay within about 3 months, begin mailing statements from the office, followed by firm but generous phone calls trying to collect. Industry estimates put the average cost of sending an invoice, including staff labor, printing, and postage, at about $35 per mailer. Some practices combat the added costs by offering a 20% prompt-pay discount. Offering payment plans is another option that helps garner eventual payment. Plus, practices should direct patients to third-party lenders such as CareCredit for larger bills.

On occasion, some small practices may allow a swap, such as allowing a patient to provide a service such as plumbing, electrical, or painting in exchange for working off the bill. Though it’s not ideal when it comes to finances, you may find it can work in a pinch for a cash-strapped patient. Make sure to keep records of what bills the patient’s work goes toward.

It often helps to incentivize your billing staff to follow up regularly, with various suggestions and tactics, to get patients to pay their bills. The incentive amount you offer will probably be less than if you had to use a collection agency.

Have a payment policy

Because your practice’s primary job is caring for patients’ physical and emotional needs, payment collection without coming off as insensitive can be tricky. “We understand these are difficult times for everyone, and we are doing our best to work with our patients,” said Dr. Chaudhry. Having a written payment policy can help build the bridge. A policy lets patients know what they can expect and can help prevent surprises over what occurs in the event of nonpayment. Your written policy should include:

- When payment is due.

- How the practice handles copays and deductibles.

- What forms of payment are accepted.

- Your policy regarding nonpayment.

Why patients don’t pay

A 2021 Healthcare Consumer Experience Study from Cedar found that medical bills are a source of anxiety and frustration for most patients, affecting their financial experience. More than half of the respondents said that paying a medical bill is stressful. Complicating matters, many health care practices rely on outdated payment systems, which may not provide patients with a clear view of what they owe and how to pay it.

The study found that 53% of respondents find understanding their plan’s coverage and benefits stressful, and 37% of patients won’t pay their bill if they can’t understand it.

People may think the patient is trying to get out of paying, which, of course, is sometimes true, but most of the time they want to pay, concluded the study. Most patients need a better explanation, communication, and accurate accounting of their out-of-pocket costs.

What can doctors do?

If you’re a physician who regularly sees patients who have problems paying their bills, you can take a few steps to minimize the financial impact on your practice:

- Bill the patient’s insurance directly to ensure you receive at least partial payment.

- Keep adequate records of services in case you need to pursue legal action.

- “Be understanding and flexible when it comes to payment arrangements, as this can often be the difference between getting paid and not getting paid at all,” said Dr. Chaudhry.

Distance yourself

When discussing payment policies, physicians should try to distance themselves from the actual collection process as much as possible. Well-meaning physicians often tell patients things like they can “figure something out “ financially or “work them in” during a scheduling conflict, but that often undermines the authority and credibility of the practice’s office staff. Plus, it teaches patients they can get their way if they work on the doctor’s soft spot – something you don’t want to encourage.

By following some of these measures, you can help ensure that your practice continues to thrive despite the challenges posed by nonpaying patients.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Blood pressure smartphone app fails to beat standard self-monitoring

Here’s another vote for less screen time.

“By itself, standard self-measured blood pressure (SMBP) has minimal effect on BP control,” wrote lead author Mark J. Pletcher, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues in JAMA Internal Medicine. “To improve BP control, SMBP must be accompanied by patient feedback, counseling, or other cointerventions, and the BP-lowering effects of SMBP appear to be proportional to the intensity of the cointervention.”

While this is known, higher-intensity cointerventions demand both money and time, prompting development of new devices that link with smartphone apps, they continued.

In the prospective randomized trial, patients with hypertension were randomly assigned to self-measure their blood pressure using a standard device that paired with a connected smartphone application or to self-measure their blood pressure with a standard device alone. Both groups achieved about an 11 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP over 6 months, reported similar levels of satisfaction with the monitoring process, and shared their readings with their physicians with similar frequency.

Methods

Dr. Pletcher and colleagues enrolled 2,101 adults who self-reported a systolic BP greater than 145 mm Hg and expressed a commitment to reduce their BP by at least 10 points in their trial. The participants, who were generally middle-aged or older, were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to monitor their BP using standard SMBP or “enhanced” SMBP. The standard group used the OMRON BP monitor alone, while the enhanced group used the same BP monitor coupled with the OMRON Connect smartphone app.

After 6 months of follow-up for each patient, mean BP reduction from baseline in the standard group was 10.6 mm Hg, compared with 10.7 mm Hg in the enhanced group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .81). While slightly more patients in the enhanced group achieved a BP lower than 140/90 mm Hg (32% vs. 29%; odds ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.34), this trend did not extend below the 130/80 mm Hg threshold.

Other secondary outcomes were also similar between groups. For example, 70% of participants in the enhanced group said they would recommend their SMBP process to a friend, compared with 69% of participants who followed the standard monitoring approach. The smartphone app had little impact on sharing readings with physicians, either, based on a 44% share rate in the enhanced group versus 48% in the standard group (P = .22).

“Enhanced SMBP does not provide any additional reduction in BP,” the investigators concluded.

New devices that link with smartphone apps, like the one used in this trial, “transmit BP measurements via wireless connection to the patient’s smartphone, where they are processed in a smartphone application to support tracking, visualization, interpretation, reminders to measure BP and/or take medications; recommendations for lifestyle interventions, medication adherence, or to discuss their BP with their clinician; and communications (for example, emailing a summary to a family member or clinician),” the researchers explained. While these devices are “only slightly more expensive than standard SMBP devices,” their relative efficacy over standard SMBP is “unclear.”

Findings can likely be extrapolated to other apps

Although the trial evaluated just one smartphone app, Dr. Pletcher suggested that the findings can likely be extrapolated to other apps.

“Most basic BP-tracking apps have some version or subset of the same essential functionality,” he said, in an interview. “My guess is that apps that meet this description without some substantially different technology or feature would likely show the same basic results as we did.”

Making a similar remark, Matthew Jung, MD, of Keck Medicine of USC, Los Angeles, stated that the findings can be “reasonably extrapolated” to other BP-tracking apps with similar functionality “if we put aside the study’s issues with power.”

When it comes to smartphone apps, active engagement is needed to achieve greater impacts on blood pressure, Dr. Pletcher said, but “there is so much competition for people’s attention on their phone that it is hard to maintain active engagement with any health-related app for long.”