User login

Tic disorders are associated with obesity and diabetes

The movement disorders are associated with cardiometabolic problems “even after taking into account a number of covariates and shared familial confounders and excluding relevant psychiatric comorbidities,” the researchers wrote. “The results highlight the importance of carefully monitoring cardiometabolic health in patients with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder across the lifespan, particularly in those with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).”

Gustaf Brander, a researcher in the department of clinical neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and his colleagues conducted a longitudinal population-based cohort study of individuals living in Sweden between Jan. 1, 1973, and Dec. 31, 2013. The researchers assessed outcomes for patients with previously validated diagnoses of Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder in the Swedish National Patient Register. Main outcomes included obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, and cardiovascular diseases, including ischemic heart diseases, arrhythmia, cerebrovascular diseases, transient ischemic attack, and arteriosclerosis. In addition, the researchers identified families with full siblings discordant for Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder.

Of the more than 14 million individuals in the cohort, 7,804 (76.4% male; median age at first diagnosis, 13.3 years) had a diagnosis of Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder in specialist care. Furthermore, the cohort included 5,141 families with full siblings who were discordant for these disorders.

Individuals with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder had a higher risk for any metabolic or cardiovascular disorder, compared with the general population (hazard ratio adjusted by sex and birth year [aHR], 1.99) and sibling controls (aHR, 1.37). Specifically, individuals with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder had higher risks for obesity (aHR, 2.76), T2DM(aHR, 1.67), and circulatory system diseases (aHR, 1.76).

The increased risk of any cardiometabolic disorder was significantly greater for males than it was for females (aHRs, 2.13 vs. 1.79), as was the risk of obesity (aHRs, 3.24 vs. 1.97).

The increased risk for cardiometabolic disorders in this patient population was evident by age 8 years. Exclusion of those patients with comorbid ADHD reduced but did not eliminate the risk (aHR, 1.52). The exclusion of other comorbidities did not significantly affect the results. Among patients with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder, those who had received antipsychotic treatment for more than 1 year were significantly less likely to have metabolic and cardiovascular disorders, compared with patients not taking antipsychotic medication. This association may be related to “greater medical vigilance” and “should not be taken as evidence that antipsychotics are free from cardiometabolic adverse effects,” the authors noted.

The study was supported by a research grant from Tourettes Action. In addition, authors reported support from the Swedish Research Council and a Karolinska Institutet PhD stipend. Two authors disclosed personal fees from publishers, and one author disclosed grants and other funding from Shire.

SOURCE: Brander G et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4279.

The movement disorders are associated with cardiometabolic problems “even after taking into account a number of covariates and shared familial confounders and excluding relevant psychiatric comorbidities,” the researchers wrote. “The results highlight the importance of carefully monitoring cardiometabolic health in patients with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder across the lifespan, particularly in those with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).”

Gustaf Brander, a researcher in the department of clinical neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and his colleagues conducted a longitudinal population-based cohort study of individuals living in Sweden between Jan. 1, 1973, and Dec. 31, 2013. The researchers assessed outcomes for patients with previously validated diagnoses of Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder in the Swedish National Patient Register. Main outcomes included obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, and cardiovascular diseases, including ischemic heart diseases, arrhythmia, cerebrovascular diseases, transient ischemic attack, and arteriosclerosis. In addition, the researchers identified families with full siblings discordant for Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder.

Of the more than 14 million individuals in the cohort, 7,804 (76.4% male; median age at first diagnosis, 13.3 years) had a diagnosis of Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder in specialist care. Furthermore, the cohort included 5,141 families with full siblings who were discordant for these disorders.

Individuals with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder had a higher risk for any metabolic or cardiovascular disorder, compared with the general population (hazard ratio adjusted by sex and birth year [aHR], 1.99) and sibling controls (aHR, 1.37). Specifically, individuals with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder had higher risks for obesity (aHR, 2.76), T2DM(aHR, 1.67), and circulatory system diseases (aHR, 1.76).

The increased risk of any cardiometabolic disorder was significantly greater for males than it was for females (aHRs, 2.13 vs. 1.79), as was the risk of obesity (aHRs, 3.24 vs. 1.97).

The increased risk for cardiometabolic disorders in this patient population was evident by age 8 years. Exclusion of those patients with comorbid ADHD reduced but did not eliminate the risk (aHR, 1.52). The exclusion of other comorbidities did not significantly affect the results. Among patients with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder, those who had received antipsychotic treatment for more than 1 year were significantly less likely to have metabolic and cardiovascular disorders, compared with patients not taking antipsychotic medication. This association may be related to “greater medical vigilance” and “should not be taken as evidence that antipsychotics are free from cardiometabolic adverse effects,” the authors noted.

The study was supported by a research grant from Tourettes Action. In addition, authors reported support from the Swedish Research Council and a Karolinska Institutet PhD stipend. Two authors disclosed personal fees from publishers, and one author disclosed grants and other funding from Shire.

SOURCE: Brander G et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4279.

The movement disorders are associated with cardiometabolic problems “even after taking into account a number of covariates and shared familial confounders and excluding relevant psychiatric comorbidities,” the researchers wrote. “The results highlight the importance of carefully monitoring cardiometabolic health in patients with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder across the lifespan, particularly in those with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).”

Gustaf Brander, a researcher in the department of clinical neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and his colleagues conducted a longitudinal population-based cohort study of individuals living in Sweden between Jan. 1, 1973, and Dec. 31, 2013. The researchers assessed outcomes for patients with previously validated diagnoses of Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder in the Swedish National Patient Register. Main outcomes included obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, and cardiovascular diseases, including ischemic heart diseases, arrhythmia, cerebrovascular diseases, transient ischemic attack, and arteriosclerosis. In addition, the researchers identified families with full siblings discordant for Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder.

Of the more than 14 million individuals in the cohort, 7,804 (76.4% male; median age at first diagnosis, 13.3 years) had a diagnosis of Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder in specialist care. Furthermore, the cohort included 5,141 families with full siblings who were discordant for these disorders.

Individuals with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder had a higher risk for any metabolic or cardiovascular disorder, compared with the general population (hazard ratio adjusted by sex and birth year [aHR], 1.99) and sibling controls (aHR, 1.37). Specifically, individuals with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder had higher risks for obesity (aHR, 2.76), T2DM(aHR, 1.67), and circulatory system diseases (aHR, 1.76).

The increased risk of any cardiometabolic disorder was significantly greater for males than it was for females (aHRs, 2.13 vs. 1.79), as was the risk of obesity (aHRs, 3.24 vs. 1.97).

The increased risk for cardiometabolic disorders in this patient population was evident by age 8 years. Exclusion of those patients with comorbid ADHD reduced but did not eliminate the risk (aHR, 1.52). The exclusion of other comorbidities did not significantly affect the results. Among patients with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder, those who had received antipsychotic treatment for more than 1 year were significantly less likely to have metabolic and cardiovascular disorders, compared with patients not taking antipsychotic medication. This association may be related to “greater medical vigilance” and “should not be taken as evidence that antipsychotics are free from cardiometabolic adverse effects,” the authors noted.

The study was supported by a research grant from Tourettes Action. In addition, authors reported support from the Swedish Research Council and a Karolinska Institutet PhD stipend. Two authors disclosed personal fees from publishers, and one author disclosed grants and other funding from Shire.

SOURCE: Brander G et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4279.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Monitor cardiometabolic health in patients with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder.

Major finding: Patients with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder have a higher risk of metabolic or cardiovascular disorders, compared with the general population (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.99) and sibling controls (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.37).

Study details: A Swedish longitudinal, population-based cohort study of 7,804 individuals with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a research grant from Tourettes Action. Authors reported support from the Swedish Research Council and a Karolinska Institutet PhD stipend. Two authors disclosed personal fees from publishers, and one author disclosed grants and other funding from Shire.

Source: Brander G et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4279.

Soy didn’t up all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors

A cohort of Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors had no increased mortality from soy intake, according to a new study.

The work adds to the existing body of evidence that women with breast cancer, or risk for breast cancer, don’t need to modify their soy intake to mitigate risk, said the study’s first author, Suzanne C. Ho, PhD.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Ho noted that the combination of increasing breast cancer incidence and improved outcome has resulted in larger numbers of breast cancer survivors in Hong Kong, where she is professor emerita at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The prospective, ongoing study examines the association between soy intake pre- and postdiagnosis and total mortality for Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors. Dr. Ho said that she and her colleagues hypothesized that they would not see higher mortality among women who had higher soy intake – and this was the case.

Of 1,497 breast cancer survivors drawn from two facilities in Hong Kong, those who consumed higher quantities of dietary soy did not have increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

There are theoretical underpinnings for thinking that soy could be a player in cancer risk, but the biochemistry and epidemiology behind the studies are complicated. Estrogen plays a role in human breast cancer, and many modern breast cancer treatments actually dampen endogenous estrogens.

However, epidemiologic data have shown that consumption of soy-based foods – which contain phytoestrogens, primarily in the form of isoflavones – is inversely associated with developing breast cancer.

This is all part of why soy-based foods have been thought of as a mixed bag with regard to breast cancer: Soy isoflavones are, said Dr. Ho, “Natural estrogen receptor modulators that possess both estrogenlike and antiestrogenic properties.”

Other chemicals contained in soy may fight cancer, with effects that are antioxidative and strengthen immune response. Soy constituents also inhibit DNA topoisomerase I and II, proteases, tyrosine kinases, and inositol phosphate, effects that can slow tumor growth. Still, one soy isoflavone, genistein, actually can promote growth of estrogen-dependent tumors in rats, said Dr. Ho

Dr. Ho and her colleagues enrolled Hong Kong residents for the study of mortality among breast cancer survivors. Participants were included if they were Chinese, female, aged 24-77 years, and had their first primary breast cancer histologically confirmed within 12 months of entering the study. Cancer had to be graded below stage III.

Using a 109-item validated food questionnaire, investigators gathered information about participants’ soy intake and general diet for the year prior to breast cancer diagnosis. Other patient characteristics, relevant prognostic information from medical records, and anthropometric data were collected at baseline, and repeated at 18, 36, and 60 months.

The primary outcome measure – all-cause mortality during the follow-up period – was tracked for a mean 50.9 months, with a 78% retention rate for study participants, said Dr. Ho. In total, 96 patients died during follow-up, making up 5.9% of the premenopausal and 7% of the postmenopausal participants.

Statistical analysis corrected for potential confounders, including patient and disease characteristics and treatment modalities, as well as overall energy consumption.

Patients were evenly divided into tertiles of soy isoflavone intake, with cutpoints of 3.77 mg/1,000 kcal and 10.05 mg/1,000 kcal for the lower limit of the two higher tertiles. For the highest tertile, though, mean isoflavone intake was actually 20.87 mg/1,000 kcal.

Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics did not differ significantly among the tertiles.

An adjusted statistical analysis looked at pre- and postmenopausal women separately by tertile of soy isoflavone consumption, setting the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality at 1.00 for women in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

For premenopausal women in the middle tertile, the HR was 0.45 (95% confidence interval, 0.20-1.00), and 0.86 for those in the highest tertile (95% CI, 0.43-1.72); 782 participants, in all, were premenopausal.

For the 715 postmenopausal women, the HR for those in the middle tertile of soy consumption was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.43-2.05), and 1.11 in the highest (95% CI, 0.54-2.29).

Taking all pre- and postmenopausal participants together, those in the middle tertile of soy isoflavone intake had an all-cause mortality HR of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.37-1.09). For the highest tertile of the full cohort, the HR was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.58-1.55).

Confidence intervals were wide in these findings, but Dr. Ho noted that “moderate soy food intake might be associated with better survival.”

“Prediagnosis soy intake did not increase the risk of all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors,” said Dr. Ho, findings she called “consistent with the literature that soy consumption does not adversely effect breast cancer survival.”

The study is ongoing, she explained, and “longer follow-up will provide further evidence on the effect of pre- and postdiagnosis soy intake on breast cancer outcomes.”

The study had a homogeneous population of southern Chinese women, with fairly good retention and robust statistical adjustment for confounders. However, it wasn’t possible to assess bioavailability of isoflavones and their metabolites, which can vary according to individual microbiota. Also, researchers did not track whether patients used traditional Chinese medicine.

The World Cancer Research Fund International supported the study. Dr. Ho reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ho S et al. NAMS 2018, Abstract S-23.

A cohort of Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors had no increased mortality from soy intake, according to a new study.

The work adds to the existing body of evidence that women with breast cancer, or risk for breast cancer, don’t need to modify their soy intake to mitigate risk, said the study’s first author, Suzanne C. Ho, PhD.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Ho noted that the combination of increasing breast cancer incidence and improved outcome has resulted in larger numbers of breast cancer survivors in Hong Kong, where she is professor emerita at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The prospective, ongoing study examines the association between soy intake pre- and postdiagnosis and total mortality for Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors. Dr. Ho said that she and her colleagues hypothesized that they would not see higher mortality among women who had higher soy intake – and this was the case.

Of 1,497 breast cancer survivors drawn from two facilities in Hong Kong, those who consumed higher quantities of dietary soy did not have increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

There are theoretical underpinnings for thinking that soy could be a player in cancer risk, but the biochemistry and epidemiology behind the studies are complicated. Estrogen plays a role in human breast cancer, and many modern breast cancer treatments actually dampen endogenous estrogens.

However, epidemiologic data have shown that consumption of soy-based foods – which contain phytoestrogens, primarily in the form of isoflavones – is inversely associated with developing breast cancer.

This is all part of why soy-based foods have been thought of as a mixed bag with regard to breast cancer: Soy isoflavones are, said Dr. Ho, “Natural estrogen receptor modulators that possess both estrogenlike and antiestrogenic properties.”

Other chemicals contained in soy may fight cancer, with effects that are antioxidative and strengthen immune response. Soy constituents also inhibit DNA topoisomerase I and II, proteases, tyrosine kinases, and inositol phosphate, effects that can slow tumor growth. Still, one soy isoflavone, genistein, actually can promote growth of estrogen-dependent tumors in rats, said Dr. Ho

Dr. Ho and her colleagues enrolled Hong Kong residents for the study of mortality among breast cancer survivors. Participants were included if they were Chinese, female, aged 24-77 years, and had their first primary breast cancer histologically confirmed within 12 months of entering the study. Cancer had to be graded below stage III.

Using a 109-item validated food questionnaire, investigators gathered information about participants’ soy intake and general diet for the year prior to breast cancer diagnosis. Other patient characteristics, relevant prognostic information from medical records, and anthropometric data were collected at baseline, and repeated at 18, 36, and 60 months.

The primary outcome measure – all-cause mortality during the follow-up period – was tracked for a mean 50.9 months, with a 78% retention rate for study participants, said Dr. Ho. In total, 96 patients died during follow-up, making up 5.9% of the premenopausal and 7% of the postmenopausal participants.

Statistical analysis corrected for potential confounders, including patient and disease characteristics and treatment modalities, as well as overall energy consumption.

Patients were evenly divided into tertiles of soy isoflavone intake, with cutpoints of 3.77 mg/1,000 kcal and 10.05 mg/1,000 kcal for the lower limit of the two higher tertiles. For the highest tertile, though, mean isoflavone intake was actually 20.87 mg/1,000 kcal.

Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics did not differ significantly among the tertiles.

An adjusted statistical analysis looked at pre- and postmenopausal women separately by tertile of soy isoflavone consumption, setting the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality at 1.00 for women in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

For premenopausal women in the middle tertile, the HR was 0.45 (95% confidence interval, 0.20-1.00), and 0.86 for those in the highest tertile (95% CI, 0.43-1.72); 782 participants, in all, were premenopausal.

For the 715 postmenopausal women, the HR for those in the middle tertile of soy consumption was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.43-2.05), and 1.11 in the highest (95% CI, 0.54-2.29).

Taking all pre- and postmenopausal participants together, those in the middle tertile of soy isoflavone intake had an all-cause mortality HR of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.37-1.09). For the highest tertile of the full cohort, the HR was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.58-1.55).

Confidence intervals were wide in these findings, but Dr. Ho noted that “moderate soy food intake might be associated with better survival.”

“Prediagnosis soy intake did not increase the risk of all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors,” said Dr. Ho, findings she called “consistent with the literature that soy consumption does not adversely effect breast cancer survival.”

The study is ongoing, she explained, and “longer follow-up will provide further evidence on the effect of pre- and postdiagnosis soy intake on breast cancer outcomes.”

The study had a homogeneous population of southern Chinese women, with fairly good retention and robust statistical adjustment for confounders. However, it wasn’t possible to assess bioavailability of isoflavones and their metabolites, which can vary according to individual microbiota. Also, researchers did not track whether patients used traditional Chinese medicine.

The World Cancer Research Fund International supported the study. Dr. Ho reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ho S et al. NAMS 2018, Abstract S-23.

A cohort of Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors had no increased mortality from soy intake, according to a new study.

The work adds to the existing body of evidence that women with breast cancer, or risk for breast cancer, don’t need to modify their soy intake to mitigate risk, said the study’s first author, Suzanne C. Ho, PhD.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Ho noted that the combination of increasing breast cancer incidence and improved outcome has resulted in larger numbers of breast cancer survivors in Hong Kong, where she is professor emerita at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The prospective, ongoing study examines the association between soy intake pre- and postdiagnosis and total mortality for Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors. Dr. Ho said that she and her colleagues hypothesized that they would not see higher mortality among women who had higher soy intake – and this was the case.

Of 1,497 breast cancer survivors drawn from two facilities in Hong Kong, those who consumed higher quantities of dietary soy did not have increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

There are theoretical underpinnings for thinking that soy could be a player in cancer risk, but the biochemistry and epidemiology behind the studies are complicated. Estrogen plays a role in human breast cancer, and many modern breast cancer treatments actually dampen endogenous estrogens.

However, epidemiologic data have shown that consumption of soy-based foods – which contain phytoestrogens, primarily in the form of isoflavones – is inversely associated with developing breast cancer.

This is all part of why soy-based foods have been thought of as a mixed bag with regard to breast cancer: Soy isoflavones are, said Dr. Ho, “Natural estrogen receptor modulators that possess both estrogenlike and antiestrogenic properties.”

Other chemicals contained in soy may fight cancer, with effects that are antioxidative and strengthen immune response. Soy constituents also inhibit DNA topoisomerase I and II, proteases, tyrosine kinases, and inositol phosphate, effects that can slow tumor growth. Still, one soy isoflavone, genistein, actually can promote growth of estrogen-dependent tumors in rats, said Dr. Ho

Dr. Ho and her colleagues enrolled Hong Kong residents for the study of mortality among breast cancer survivors. Participants were included if they were Chinese, female, aged 24-77 years, and had their first primary breast cancer histologically confirmed within 12 months of entering the study. Cancer had to be graded below stage III.

Using a 109-item validated food questionnaire, investigators gathered information about participants’ soy intake and general diet for the year prior to breast cancer diagnosis. Other patient characteristics, relevant prognostic information from medical records, and anthropometric data were collected at baseline, and repeated at 18, 36, and 60 months.

The primary outcome measure – all-cause mortality during the follow-up period – was tracked for a mean 50.9 months, with a 78% retention rate for study participants, said Dr. Ho. In total, 96 patients died during follow-up, making up 5.9% of the premenopausal and 7% of the postmenopausal participants.

Statistical analysis corrected for potential confounders, including patient and disease characteristics and treatment modalities, as well as overall energy consumption.

Patients were evenly divided into tertiles of soy isoflavone intake, with cutpoints of 3.77 mg/1,000 kcal and 10.05 mg/1,000 kcal for the lower limit of the two higher tertiles. For the highest tertile, though, mean isoflavone intake was actually 20.87 mg/1,000 kcal.

Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics did not differ significantly among the tertiles.

An adjusted statistical analysis looked at pre- and postmenopausal women separately by tertile of soy isoflavone consumption, setting the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality at 1.00 for women in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

For premenopausal women in the middle tertile, the HR was 0.45 (95% confidence interval, 0.20-1.00), and 0.86 for those in the highest tertile (95% CI, 0.43-1.72); 782 participants, in all, were premenopausal.

For the 715 postmenopausal women, the HR for those in the middle tertile of soy consumption was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.43-2.05), and 1.11 in the highest (95% CI, 0.54-2.29).

Taking all pre- and postmenopausal participants together, those in the middle tertile of soy isoflavone intake had an all-cause mortality HR of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.37-1.09). For the highest tertile of the full cohort, the HR was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.58-1.55).

Confidence intervals were wide in these findings, but Dr. Ho noted that “moderate soy food intake might be associated with better survival.”

“Prediagnosis soy intake did not increase the risk of all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors,” said Dr. Ho, findings she called “consistent with the literature that soy consumption does not adversely effect breast cancer survival.”

The study is ongoing, she explained, and “longer follow-up will provide further evidence on the effect of pre- and postdiagnosis soy intake on breast cancer outcomes.”

The study had a homogeneous population of southern Chinese women, with fairly good retention and robust statistical adjustment for confounders. However, it wasn’t possible to assess bioavailability of isoflavones and their metabolites, which can vary according to individual microbiota. Also, researchers did not track whether patients used traditional Chinese medicine.

The World Cancer Research Fund International supported the study. Dr. Ho reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ho S et al. NAMS 2018, Abstract S-23.

REPORTING FROM NAMS 2018

Key clinical point: Soy consumption did not increase mortality risk in breast cancer survivors.

Major finding: The hazard ratios for all-cause mortality were 0.63 and 0.95 for the two highest tertiles of soy consumption.

Study details: An ongoing prospective cohort study of 1,497 female breast cancer survivors in Hong Kong.

Disclosures: The World Cancer Research Fund International supported the study. Dr. Ho reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Ho S et al. NAMS 2018, Abstract S-23.

Daily News Special: SABCS

Stories include: uUing low-dose tamoxifen, the latest findings from the KATHERINE trial, results of a meta-analysis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and capecitabine in early stage triple negative breast cancer.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Stories include: uUing low-dose tamoxifen, the latest findings from the KATHERINE trial, results of a meta-analysis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and capecitabine in early stage triple negative breast cancer.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Stories include: uUing low-dose tamoxifen, the latest findings from the KATHERINE trial, results of a meta-analysis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and capecitabine in early stage triple negative breast cancer.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Neoadjuvant degarelix more effective than triptorelin for ovarian suppression

Degarelix, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist approved for prostate cancer, was more effective than a GnRH agonist in achieving ovarian function suppression in women with breast cancer, results of a randomized trial show.

Ovarian function suppression was achieved more rapidly and maintained more effectively with degarelix, compared with triptorelin, in the premenopausal women who were receiving letrozole for neoadjuvant endocrine therapy, investigators said.

Adverse events including hot flashes and injection site reactions were reported more often with degarelix versus the GnRH agonist in this randomized, phase 2 trial of 51 subjects.

Additional research is needed to determine whether degarelix results in superior disease control versus the current standard of care, reported Silvia Dellapasqua, MD, of the European Institute of Oncology IRCCS in Milan, Italy, and coinvestigators.

“The study is hypothesis-generating, and supports later studies to assess whether maintenance of ovarian function suppression with degarelix translates into a better clinical outcome and is worth a trade-off of increased rate of some adverse events,” the researchers wrote. The report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive degarelix plus letrozole or triptorelin plus letrozole for six 28-day cycles. Degarelix was administered subcutaneously on day 1 of each cycle, while triptorelin was administered intramuscularly on day 1 of each cycle, and oral letrozole was to be taken daily. Surgery was performed a few weeks after the last injection.

All patients achieved optimal ovarian function suppression by the end of the first cycle. However, that endpoint was achieved significantly faster among patients in the degarelix arm, at a median of 3 days, versus a median of 14 days for the GnRH agonist, the investigators reported.

The optimal ovarian function suppression was seen three times faster with degarelix (hazard ratio, 3.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-5.65; P less than 001), they added.

One hundred percent of patients receiving degarelix and letrozole maintained optimal ovarian function suppression throughout the study, while about 15% of patients assigned to triptorelin had suboptimal suppression after that first cycle.

The group of patients receiving degarelix had a higher rate of node-negative disease at surgery, and a higher rate of breast-conserving surgery compared with the triptorelin group, the investigators said.

There were two grade 3 adverse events, hypertension and anemia, which both occurred in the triptorelin group, and no grade 4 adverse events. The most common adverse events reported were hot flashes, occurring in 80.0% and 69.2% of the degarelix and triptorelin groups, respectively; arthralgias in 32.0% and 53.8%; insomnia in 24.0% and 11.5%; injection site reactions in 24.0% and 0%; and nausea in 16.0% and 3.8%.

The study was supported by Ferring, and by the International Breast Cancer Study Group via Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research, Cancer Research Switzerland, Oncosuisse, Swiss Cancer League, and the Foundation for Clinical Cancer Research of Eastern Switzerland. The authors reported disclosures related to Ferring, Novartis, Ipsen, DVAX, Roche, Genentech, Pfizer, Celgene, and Merck, among others.

SOURCE: Dellapasqua S et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Dec 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00296.

Degarelix, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist approved for prostate cancer, was more effective than a GnRH agonist in achieving ovarian function suppression in women with breast cancer, results of a randomized trial show.

Ovarian function suppression was achieved more rapidly and maintained more effectively with degarelix, compared with triptorelin, in the premenopausal women who were receiving letrozole for neoadjuvant endocrine therapy, investigators said.

Adverse events including hot flashes and injection site reactions were reported more often with degarelix versus the GnRH agonist in this randomized, phase 2 trial of 51 subjects.

Additional research is needed to determine whether degarelix results in superior disease control versus the current standard of care, reported Silvia Dellapasqua, MD, of the European Institute of Oncology IRCCS in Milan, Italy, and coinvestigators.

“The study is hypothesis-generating, and supports later studies to assess whether maintenance of ovarian function suppression with degarelix translates into a better clinical outcome and is worth a trade-off of increased rate of some adverse events,” the researchers wrote. The report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive degarelix plus letrozole or triptorelin plus letrozole for six 28-day cycles. Degarelix was administered subcutaneously on day 1 of each cycle, while triptorelin was administered intramuscularly on day 1 of each cycle, and oral letrozole was to be taken daily. Surgery was performed a few weeks after the last injection.

All patients achieved optimal ovarian function suppression by the end of the first cycle. However, that endpoint was achieved significantly faster among patients in the degarelix arm, at a median of 3 days, versus a median of 14 days for the GnRH agonist, the investigators reported.

The optimal ovarian function suppression was seen three times faster with degarelix (hazard ratio, 3.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-5.65; P less than 001), they added.

One hundred percent of patients receiving degarelix and letrozole maintained optimal ovarian function suppression throughout the study, while about 15% of patients assigned to triptorelin had suboptimal suppression after that first cycle.

The group of patients receiving degarelix had a higher rate of node-negative disease at surgery, and a higher rate of breast-conserving surgery compared with the triptorelin group, the investigators said.

There were two grade 3 adverse events, hypertension and anemia, which both occurred in the triptorelin group, and no grade 4 adverse events. The most common adverse events reported were hot flashes, occurring in 80.0% and 69.2% of the degarelix and triptorelin groups, respectively; arthralgias in 32.0% and 53.8%; insomnia in 24.0% and 11.5%; injection site reactions in 24.0% and 0%; and nausea in 16.0% and 3.8%.

The study was supported by Ferring, and by the International Breast Cancer Study Group via Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research, Cancer Research Switzerland, Oncosuisse, Swiss Cancer League, and the Foundation for Clinical Cancer Research of Eastern Switzerland. The authors reported disclosures related to Ferring, Novartis, Ipsen, DVAX, Roche, Genentech, Pfizer, Celgene, and Merck, among others.

SOURCE: Dellapasqua S et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Dec 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00296.

Degarelix, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist approved for prostate cancer, was more effective than a GnRH agonist in achieving ovarian function suppression in women with breast cancer, results of a randomized trial show.

Ovarian function suppression was achieved more rapidly and maintained more effectively with degarelix, compared with triptorelin, in the premenopausal women who were receiving letrozole for neoadjuvant endocrine therapy, investigators said.

Adverse events including hot flashes and injection site reactions were reported more often with degarelix versus the GnRH agonist in this randomized, phase 2 trial of 51 subjects.

Additional research is needed to determine whether degarelix results in superior disease control versus the current standard of care, reported Silvia Dellapasqua, MD, of the European Institute of Oncology IRCCS in Milan, Italy, and coinvestigators.

“The study is hypothesis-generating, and supports later studies to assess whether maintenance of ovarian function suppression with degarelix translates into a better clinical outcome and is worth a trade-off of increased rate of some adverse events,” the researchers wrote. The report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive degarelix plus letrozole or triptorelin plus letrozole for six 28-day cycles. Degarelix was administered subcutaneously on day 1 of each cycle, while triptorelin was administered intramuscularly on day 1 of each cycle, and oral letrozole was to be taken daily. Surgery was performed a few weeks after the last injection.

All patients achieved optimal ovarian function suppression by the end of the first cycle. However, that endpoint was achieved significantly faster among patients in the degarelix arm, at a median of 3 days, versus a median of 14 days for the GnRH agonist, the investigators reported.

The optimal ovarian function suppression was seen three times faster with degarelix (hazard ratio, 3.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-5.65; P less than 001), they added.

One hundred percent of patients receiving degarelix and letrozole maintained optimal ovarian function suppression throughout the study, while about 15% of patients assigned to triptorelin had suboptimal suppression after that first cycle.

The group of patients receiving degarelix had a higher rate of node-negative disease at surgery, and a higher rate of breast-conserving surgery compared with the triptorelin group, the investigators said.

There were two grade 3 adverse events, hypertension and anemia, which both occurred in the triptorelin group, and no grade 4 adverse events. The most common adverse events reported were hot flashes, occurring in 80.0% and 69.2% of the degarelix and triptorelin groups, respectively; arthralgias in 32.0% and 53.8%; insomnia in 24.0% and 11.5%; injection site reactions in 24.0% and 0%; and nausea in 16.0% and 3.8%.

The study was supported by Ferring, and by the International Breast Cancer Study Group via Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research, Cancer Research Switzerland, Oncosuisse, Swiss Cancer League, and the Foundation for Clinical Cancer Research of Eastern Switzerland. The authors reported disclosures related to Ferring, Novartis, Ipsen, DVAX, Roche, Genentech, Pfizer, Celgene, and Merck, among others.

SOURCE: Dellapasqua S et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Dec 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00296.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Degarelix, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist approved for prostate cancer, was more effective than the GnRH agonist triptorelin in achieving ovarian function suppression.

Major finding: Ovarian function suppression occurred three times faster with degarelix (hazard ratio, 3.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.65-5.65; P less than .001) and in contrast to the triptorelin group, none had suboptimal suppression on subsequent cycles.

Study details: A randomized phase 2 trial including 51 premenopausal women receiving letrozole for locally advanced, endocrine-responsive breast cancer.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by Ferring. Authors reported disclosures related to Ferring, Novartis, Ipsen, DVAX, Roche, Genentech, Pfizer, Celgene, and Merck, among others.

Source: Dellapasqua S et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Dec 27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00296.

As deep sleep decreases, Alzheimer’s pathology – particularly tau – increases

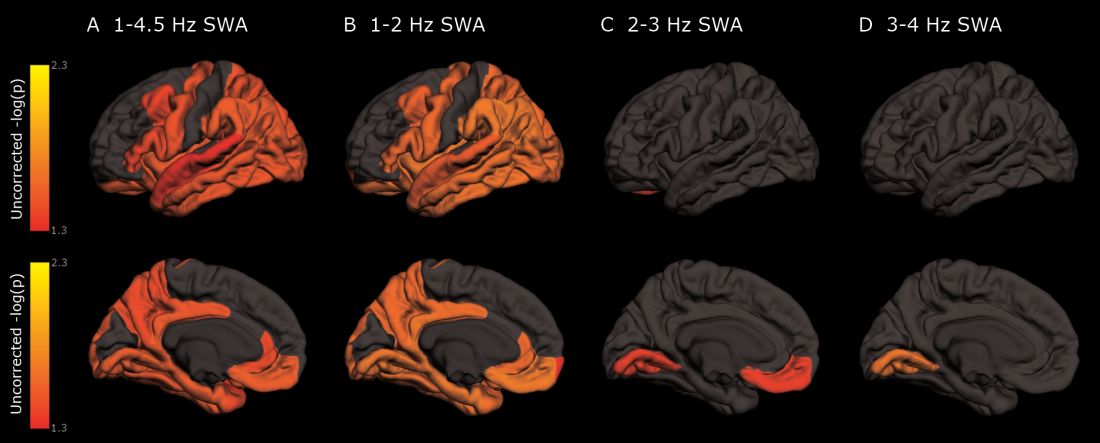

The protein was evident in areas associated with memory consolidation, typically affected in Alzheimer’s disease: the entorhinal, parahippocampal, inferior parietal, insula, isthmus cingulate, lingual, supramarginal, and orbitofrontal regions.

Because the findings were observed in a population of cognitively normal and minimally impaired subjects, they suggest a role for sleep studies in assessing the risk for cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, and in monitoring patients with the disease, reported Brendan P. Lucey, MD, and his colleagues. The report is in Science and Translational Medicine (Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11:eaau6550).

“With the rising incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in an aging population, our findings have potential application in both clinical trials and patient screening for Alzheimer’s disease to noninvasively monitor for progression of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” wrote Dr. Lucey, director of the Sleep Medicine Center and assistant professor of neurology at Washington University in St. Louis. “For instance, periodically measuring non-REM slow wave activity, in conjunction with other biomarkers, may have utility for monitoring Alzheimer’s disease risk or response to an Alzheimer’s disease treatment.”

Dr. Lucey and his colleagues examined sleep architecture and tau and amyloid deposition in 119 subjects enrolled in longitudinal aging studies. For 6 nights, subjects slept with a single-channel EEG monitor on. They also underwent cognitive testing and genotyping for Alzheimer’s disease risk factors.

Subjects were a mean of 74 years old. Almost 80% had normal cognition as measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR); the remainder had very mild cognitive impairment (CDR 0.5)

Among those with positive biomarker findings, sleep architecture was altered in several ways: lower REM latency, lower wake after sleep onset, prolonged sleep-onset latency, and longer self-reported total sleep time. The differences were evident in those with normal cognition, but even more pronounced in those with mild cognitive impairment. Despite the longer sleep times, however, sleep efficiency was decreased.

Decreased non-REM slow wave activity was associated with increased tau deposition. The protein was largely concentrated in areas of typical Alzheimer’s disease pathology (entorhinal, parahippocampal, orbital frontal, precuneus, inferior parietal, and inferior temporal regions). There were no significant associations between non-REM slow wave activity and amyloid deposits.

Other sleep parameters, however, were associated with amyloid, including REM latency and sleep latency, “suggesting that as amyloid-beta deposition increased, the time to fall asleep and enter REM sleep decreased,” the investigators said.

Those with tau pathology also slept longer, reporting more daytime naps. “This suggests that participants with greater tau pathology experienced daytime sleepiness despite increased total sleep time.”

“These results, coupled with the non-REM slow wave activity findings, suggest that the quality of sleep decreases with increasing tau despite increased sleep time.” Questions about napping should probably be included in dementia screening discussions, they said.

The study was largely funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lucey had no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Lucey BP et al. Sci Transl Med 2019 Jan 9;11:eaau6550.

The protein was evident in areas associated with memory consolidation, typically affected in Alzheimer’s disease: the entorhinal, parahippocampal, inferior parietal, insula, isthmus cingulate, lingual, supramarginal, and orbitofrontal regions.

Because the findings were observed in a population of cognitively normal and minimally impaired subjects, they suggest a role for sleep studies in assessing the risk for cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, and in monitoring patients with the disease, reported Brendan P. Lucey, MD, and his colleagues. The report is in Science and Translational Medicine (Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11:eaau6550).

“With the rising incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in an aging population, our findings have potential application in both clinical trials and patient screening for Alzheimer’s disease to noninvasively monitor for progression of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” wrote Dr. Lucey, director of the Sleep Medicine Center and assistant professor of neurology at Washington University in St. Louis. “For instance, periodically measuring non-REM slow wave activity, in conjunction with other biomarkers, may have utility for monitoring Alzheimer’s disease risk or response to an Alzheimer’s disease treatment.”

Dr. Lucey and his colleagues examined sleep architecture and tau and amyloid deposition in 119 subjects enrolled in longitudinal aging studies. For 6 nights, subjects slept with a single-channel EEG monitor on. They also underwent cognitive testing and genotyping for Alzheimer’s disease risk factors.

Subjects were a mean of 74 years old. Almost 80% had normal cognition as measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR); the remainder had very mild cognitive impairment (CDR 0.5)

Among those with positive biomarker findings, sleep architecture was altered in several ways: lower REM latency, lower wake after sleep onset, prolonged sleep-onset latency, and longer self-reported total sleep time. The differences were evident in those with normal cognition, but even more pronounced in those with mild cognitive impairment. Despite the longer sleep times, however, sleep efficiency was decreased.

Decreased non-REM slow wave activity was associated with increased tau deposition. The protein was largely concentrated in areas of typical Alzheimer’s disease pathology (entorhinal, parahippocampal, orbital frontal, precuneus, inferior parietal, and inferior temporal regions). There were no significant associations between non-REM slow wave activity and amyloid deposits.

Other sleep parameters, however, were associated with amyloid, including REM latency and sleep latency, “suggesting that as amyloid-beta deposition increased, the time to fall asleep and enter REM sleep decreased,” the investigators said.

Those with tau pathology also slept longer, reporting more daytime naps. “This suggests that participants with greater tau pathology experienced daytime sleepiness despite increased total sleep time.”

“These results, coupled with the non-REM slow wave activity findings, suggest that the quality of sleep decreases with increasing tau despite increased sleep time.” Questions about napping should probably be included in dementia screening discussions, they said.

The study was largely funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lucey had no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Lucey BP et al. Sci Transl Med 2019 Jan 9;11:eaau6550.

The protein was evident in areas associated with memory consolidation, typically affected in Alzheimer’s disease: the entorhinal, parahippocampal, inferior parietal, insula, isthmus cingulate, lingual, supramarginal, and orbitofrontal regions.

Because the findings were observed in a population of cognitively normal and minimally impaired subjects, they suggest a role for sleep studies in assessing the risk for cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, and in monitoring patients with the disease, reported Brendan P. Lucey, MD, and his colleagues. The report is in Science and Translational Medicine (Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11:eaau6550).

“With the rising incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in an aging population, our findings have potential application in both clinical trials and patient screening for Alzheimer’s disease to noninvasively monitor for progression of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” wrote Dr. Lucey, director of the Sleep Medicine Center and assistant professor of neurology at Washington University in St. Louis. “For instance, periodically measuring non-REM slow wave activity, in conjunction with other biomarkers, may have utility for monitoring Alzheimer’s disease risk or response to an Alzheimer’s disease treatment.”

Dr. Lucey and his colleagues examined sleep architecture and tau and amyloid deposition in 119 subjects enrolled in longitudinal aging studies. For 6 nights, subjects slept with a single-channel EEG monitor on. They also underwent cognitive testing and genotyping for Alzheimer’s disease risk factors.

Subjects were a mean of 74 years old. Almost 80% had normal cognition as measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR); the remainder had very mild cognitive impairment (CDR 0.5)

Among those with positive biomarker findings, sleep architecture was altered in several ways: lower REM latency, lower wake after sleep onset, prolonged sleep-onset latency, and longer self-reported total sleep time. The differences were evident in those with normal cognition, but even more pronounced in those with mild cognitive impairment. Despite the longer sleep times, however, sleep efficiency was decreased.

Decreased non-REM slow wave activity was associated with increased tau deposition. The protein was largely concentrated in areas of typical Alzheimer’s disease pathology (entorhinal, parahippocampal, orbital frontal, precuneus, inferior parietal, and inferior temporal regions). There were no significant associations between non-REM slow wave activity and amyloid deposits.

Other sleep parameters, however, were associated with amyloid, including REM latency and sleep latency, “suggesting that as amyloid-beta deposition increased, the time to fall asleep and enter REM sleep decreased,” the investigators said.

Those with tau pathology also slept longer, reporting more daytime naps. “This suggests that participants with greater tau pathology experienced daytime sleepiness despite increased total sleep time.”

“These results, coupled with the non-REM slow wave activity findings, suggest that the quality of sleep decreases with increasing tau despite increased sleep time.” Questions about napping should probably be included in dementia screening discussions, they said.

The study was largely funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lucey had no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Lucey BP et al. Sci Transl Med 2019 Jan 9;11:eaau6550.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Cognitively normal subjects with tau deposition experience altered sleep patterns.

Major finding: Decreased time in non-REM deep sleep was associated with increased tau pathology in Alzheimer’s-affected brain regions and in cerebrospinal fluid.

Study details: The prospective longitudinal study comprised 119 subjects.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Lucey BP et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Jan 9;11:eaau6550.

Alcohol use, psychological distress associated with possible RBD

(RBD), according to a population-based cohort study published in Neurology. In addition, the results also replicate previous findings of an association between possible RBD and smoking, low education, and male sex.

The risk factors for RBD have been studied comparatively little. “While much is still unknown about RBD, it can be caused by medications or it may be an early sign of another neurologic condition like Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, or multiple system atrophy,” according to Ronald B. Postuma, MD, an associate professor at McGill University, Montreal. “Identifying lifestyle and personal risk factors linked to this sleep disorder may lead to finding ways to reduce the chances of developing it.”

To assess sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical correlates of possible RBD, Dr. Postuma and his colleagues examined baseline data collected between 2012 and 2015 in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA), which included 30,097 participants. To screen for possible RBD, the CLSA researchers asked patients, “Have you ever been told, or suspected yourself, that you seem to ‘act out your dreams’ while asleep [e.g., punching, flailing your arms in the air, making running movements, etc.]?” Participants answered additional questions to rule out RBD mimics. Patients with symptom onset before age 20 years, positive apnea screen, or a diagnosis of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, parkinsonism, or Parkinson’s disease were excluded from analysis.

In all, 3,271 participants screened positive for possible RBD. After the investigators excluded participants with potential mimics, 958 patients (about 3.2% of the total population) remained in the analysis. Approximately 59% of patients with possible RBD were male, compared with 42% of controls. Patients with possible RBD were more likely to be married, in a common-law relationship, or widowed.

Participants with possible RBD had slightly less education (estimated mean, 13.2 years vs. 13.6 years) and lower income, compared with controls. Participants with possible RBD retired at a slightly younger age (57.5 years vs. 58.6 years) and were more likely to have retired because of health concerns (28.9% vs. 22.0%), compared with controls.

In addition, patients with possible RBD were more likely to drink more and to be moderate to heavy drinkers than controls; they were also more likely to be current or past smokers. Antidepressant use was more frequent and psychological distress was greater among participants with possible RBD.

When the investigators performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis, the associations between possible RBD and male sex and relationship status remained. Lower educational level, but not income level, also remained associated with possible RBD. Furthermore, retirement age and having reported retirement because of health concerns remained significantly associated with possible RBD, as did the amount of alcohol consumed weekly and moderate to heavy drinking. Sensitivity analyses did not change the results significantly.

One of the study’s limitations is its reliance on self-report to identify participants with possible RBD, the authors wrote. The prevalence of possible RBD in the study was 3.2%, but research using polysomnography has found a prevalence of about 1%. Thus, the majority of cases in this study may have other disorders such as restless legs syndrome or periodic limb movements. Furthermore, many participants who enact their dreams (such as unmarried people) are likely unaware of it. Finally, the researchers did not measure several variables of interest, such as consumption of caffeinated products.

“The main advantages of our current study are the large sample size; the systematic population-based sampling; the capacity to adjust for diverse potential confounding variables, including mental illness; and the ability to screen out RBD mimics,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Postuma RB et al. Neurology. 2018 Dec 26. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006849.

(RBD), according to a population-based cohort study published in Neurology. In addition, the results also replicate previous findings of an association between possible RBD and smoking, low education, and male sex.

The risk factors for RBD have been studied comparatively little. “While much is still unknown about RBD, it can be caused by medications or it may be an early sign of another neurologic condition like Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, or multiple system atrophy,” according to Ronald B. Postuma, MD, an associate professor at McGill University, Montreal. “Identifying lifestyle and personal risk factors linked to this sleep disorder may lead to finding ways to reduce the chances of developing it.”

To assess sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical correlates of possible RBD, Dr. Postuma and his colleagues examined baseline data collected between 2012 and 2015 in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA), which included 30,097 participants. To screen for possible RBD, the CLSA researchers asked patients, “Have you ever been told, or suspected yourself, that you seem to ‘act out your dreams’ while asleep [e.g., punching, flailing your arms in the air, making running movements, etc.]?” Participants answered additional questions to rule out RBD mimics. Patients with symptom onset before age 20 years, positive apnea screen, or a diagnosis of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, parkinsonism, or Parkinson’s disease were excluded from analysis.

In all, 3,271 participants screened positive for possible RBD. After the investigators excluded participants with potential mimics, 958 patients (about 3.2% of the total population) remained in the analysis. Approximately 59% of patients with possible RBD were male, compared with 42% of controls. Patients with possible RBD were more likely to be married, in a common-law relationship, or widowed.

Participants with possible RBD had slightly less education (estimated mean, 13.2 years vs. 13.6 years) and lower income, compared with controls. Participants with possible RBD retired at a slightly younger age (57.5 years vs. 58.6 years) and were more likely to have retired because of health concerns (28.9% vs. 22.0%), compared with controls.

In addition, patients with possible RBD were more likely to drink more and to be moderate to heavy drinkers than controls; they were also more likely to be current or past smokers. Antidepressant use was more frequent and psychological distress was greater among participants with possible RBD.

When the investigators performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis, the associations between possible RBD and male sex and relationship status remained. Lower educational level, but not income level, also remained associated with possible RBD. Furthermore, retirement age and having reported retirement because of health concerns remained significantly associated with possible RBD, as did the amount of alcohol consumed weekly and moderate to heavy drinking. Sensitivity analyses did not change the results significantly.

One of the study’s limitations is its reliance on self-report to identify participants with possible RBD, the authors wrote. The prevalence of possible RBD in the study was 3.2%, but research using polysomnography has found a prevalence of about 1%. Thus, the majority of cases in this study may have other disorders such as restless legs syndrome or periodic limb movements. Furthermore, many participants who enact their dreams (such as unmarried people) are likely unaware of it. Finally, the researchers did not measure several variables of interest, such as consumption of caffeinated products.

“The main advantages of our current study are the large sample size; the systematic population-based sampling; the capacity to adjust for diverse potential confounding variables, including mental illness; and the ability to screen out RBD mimics,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Postuma RB et al. Neurology. 2018 Dec 26. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006849.

(RBD), according to a population-based cohort study published in Neurology. In addition, the results also replicate previous findings of an association between possible RBD and smoking, low education, and male sex.

The risk factors for RBD have been studied comparatively little. “While much is still unknown about RBD, it can be caused by medications or it may be an early sign of another neurologic condition like Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, or multiple system atrophy,” according to Ronald B. Postuma, MD, an associate professor at McGill University, Montreal. “Identifying lifestyle and personal risk factors linked to this sleep disorder may lead to finding ways to reduce the chances of developing it.”

To assess sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical correlates of possible RBD, Dr. Postuma and his colleagues examined baseline data collected between 2012 and 2015 in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA), which included 30,097 participants. To screen for possible RBD, the CLSA researchers asked patients, “Have you ever been told, or suspected yourself, that you seem to ‘act out your dreams’ while asleep [e.g., punching, flailing your arms in the air, making running movements, etc.]?” Participants answered additional questions to rule out RBD mimics. Patients with symptom onset before age 20 years, positive apnea screen, or a diagnosis of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, parkinsonism, or Parkinson’s disease were excluded from analysis.

In all, 3,271 participants screened positive for possible RBD. After the investigators excluded participants with potential mimics, 958 patients (about 3.2% of the total population) remained in the analysis. Approximately 59% of patients with possible RBD were male, compared with 42% of controls. Patients with possible RBD were more likely to be married, in a common-law relationship, or widowed.

Participants with possible RBD had slightly less education (estimated mean, 13.2 years vs. 13.6 years) and lower income, compared with controls. Participants with possible RBD retired at a slightly younger age (57.5 years vs. 58.6 years) and were more likely to have retired because of health concerns (28.9% vs. 22.0%), compared with controls.

In addition, patients with possible RBD were more likely to drink more and to be moderate to heavy drinkers than controls; they were also more likely to be current or past smokers. Antidepressant use was more frequent and psychological distress was greater among participants with possible RBD.

When the investigators performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis, the associations between possible RBD and male sex and relationship status remained. Lower educational level, but not income level, also remained associated with possible RBD. Furthermore, retirement age and having reported retirement because of health concerns remained significantly associated with possible RBD, as did the amount of alcohol consumed weekly and moderate to heavy drinking. Sensitivity analyses did not change the results significantly.

One of the study’s limitations is its reliance on self-report to identify participants with possible RBD, the authors wrote. The prevalence of possible RBD in the study was 3.2%, but research using polysomnography has found a prevalence of about 1%. Thus, the majority of cases in this study may have other disorders such as restless legs syndrome or periodic limb movements. Furthermore, many participants who enact their dreams (such as unmarried people) are likely unaware of it. Finally, the researchers did not measure several variables of interest, such as consumption of caffeinated products.

“The main advantages of our current study are the large sample size; the systematic population-based sampling; the capacity to adjust for diverse potential confounding variables, including mental illness; and the ability to screen out RBD mimics,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Postuma RB et al. Neurology. 2018 Dec 26. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006849.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Alcohol use and psychological distress are associated with possible REM sleep behavior disorder.

Major finding: A self-report questionnaire yielded a 3.2% prevalence of possible REM sleep behavior disorder.

Study details: A prospective, population-based cohort study of 30,097 participants.

Disclosures: The Canadian government provided funding for the research.

Source: Postuma RB et al. Neurology. 2018 Dec 26. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006849.

Daclizumab beta may be superior to interferon beta on MS disability progression

(MS), according to research published in the December 2018 issue of the Multiple Sclerosis Journal. The benefits are observed in the overall patient population, as well as in subgroups of patients based on demographic and disease characteristics.

Biogen and AbbVie, the manufacturers of daclizumab beta, voluntarily removed the therapy from the market in March 2018 because of safety concerns that included reports of severe liver damage and conditions associated with the immune system.

The phase 3 DECIDE study (NCT01064401) compared the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous daclizumab beta (150 mg) every 4 weeks with those of intramuscular interferon beta-1a (30 mcg) once weekly in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Daclizumab beta reduced the risk of 24-week confirmed disability progression as assessed by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) by 27%, compared with interferon beta-1a. Daclizumab beta also was associated with a greater median change from baseline to week 96 in MS Functional Composite (MSFC) score and a 24% reduction in the risk of clinically meaningful worsening on the physical impact subscale of the patient-reported 29-Item MS Impact Scale (MSIS-29 PHYS).

To shed light on the treatment’s effects in various demographic groups and in patients with specific clinical characteristics, Stanley L. Cohan, MD, PhD, medical director of Providence MS Center in Portland, Ore., and colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of DECIDE data to examine the treatment effects of daclizumab beta and interferon beta-1a on patient disability or impairment in specific patient subgroups. The investigators examined results according to demographic characteristics, such as age (that is, 35 years or younger and older than 35 years) and sex. They also examined results in subgroups with the following baseline disease characteristics: disability (as defined by EDSS score), relapses in the previous 12 months, disease duration, presence of gadolinium enhancing lesions, T2 hyperintense lesion volume, disease activity, prior use of disease-modifying treatment, and prior use of interferon beta.

Dr. Cohan and colleagues focused on the following three outcome measures: 24-week confirmed disability progression (as measured by EDSS), 24-week sustained worsening on the MSFC, and the proportion of patients with clinically meaningful worsening in MSIS-29 PHYS at week 96. The researchers defined 24-week confirmed disability progression as an increase in the EDSS score of one or more points from a baseline score of 1 or higher or 1.5 points or more from a baseline score of 0 as confirmed after 24 weeks. They defined 24-week sustained worsening on the MSFC as worsening of 20% or more on the Timed 25-Foot Walk, worsening of 20% or more on Nine-Hole Peg Test, or a decrease of four or more points on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test sustained for 24 weeks.

Of the 1,841 patients enrolled in DECIDE, 922 were randomized to interferon beta-1a, and 919 were randomized to daclizumab beta. The treatment groups were well balanced in terms of demographic characteristics. Patients’ mean age was approximately 36 years, 68% of participants were female, and 90% of patients were white. Mean time since diagnosis at baseline was about 4 years, mean number of relapses in the previous year was 1.6, and mean baseline EDSS score was 2.5.

Daclizumab beta was associated with a lower risk of 24-week confirmed disability progression, compared with interferon beta-1a, in all subgroups. Patients aged 35 years or younger had the greatest risk reduction.

The proportion of patients who had 24-week sustained worsening on the MSFC at week 96 was 24% for daclizumab beta and 28% for interferon beta-1a. In the whole study population, daclizumab beta reduced the risk of this outcome by 20%, compared with interferon beta-1a. Daclizumab beta resulted in improved outcomes among all subgroups, compared with interferon beta-1a.

In addition, daclizumab beta reduced the risk of a clinically meaningful worsening of MSIS-29 PHYS at week 96 by 24%, compared with interferon beta-1a. The investigators observed trends favoring daclizumab beta in all subgroups.

“These analyses should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating for future studies,” said Dr. Cohan and colleagues. They observed that some of the subgroups analyzed had small sample sizes and that no adjustments were made for multiple testing. Nevertheless, the results suggest that daclizumab beta has superior efficacy, compared with interferon beta-1a, regardless of patients’ demographic and disease characteristics, they concluded.

Biogen and AbbVie Biotherapeutics supported the study.

SOURCE: Cohan S et al. Mult Scler J. 2018. doi: 10.1177/1352458517735190.

This article was updated on 3/22/19.

(MS), according to research published in the December 2018 issue of the Multiple Sclerosis Journal. The benefits are observed in the overall patient population, as well as in subgroups of patients based on demographic and disease characteristics.

Biogen and AbbVie, the manufacturers of daclizumab beta, voluntarily removed the therapy from the market in March 2018 because of safety concerns that included reports of severe liver damage and conditions associated with the immune system.

The phase 3 DECIDE study (NCT01064401) compared the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous daclizumab beta (150 mg) every 4 weeks with those of intramuscular interferon beta-1a (30 mcg) once weekly in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Daclizumab beta reduced the risk of 24-week confirmed disability progression as assessed by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) by 27%, compared with interferon beta-1a. Daclizumab beta also was associated with a greater median change from baseline to week 96 in MS Functional Composite (MSFC) score and a 24% reduction in the risk of clinically meaningful worsening on the physical impact subscale of the patient-reported 29-Item MS Impact Scale (MSIS-29 PHYS).

To shed light on the treatment’s effects in various demographic groups and in patients with specific clinical characteristics, Stanley L. Cohan, MD, PhD, medical director of Providence MS Center in Portland, Ore., and colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of DECIDE data to examine the treatment effects of daclizumab beta and interferon beta-1a on patient disability or impairment in specific patient subgroups. The investigators examined results according to demographic characteristics, such as age (that is, 35 years or younger and older than 35 years) and sex. They also examined results in subgroups with the following baseline disease characteristics: disability (as defined by EDSS score), relapses in the previous 12 months, disease duration, presence of gadolinium enhancing lesions, T2 hyperintense lesion volume, disease activity, prior use of disease-modifying treatment, and prior use of interferon beta.

Dr. Cohan and colleagues focused on the following three outcome measures: 24-week confirmed disability progression (as measured by EDSS), 24-week sustained worsening on the MSFC, and the proportion of patients with clinically meaningful worsening in MSIS-29 PHYS at week 96. The researchers defined 24-week confirmed disability progression as an increase in the EDSS score of one or more points from a baseline score of 1 or higher or 1.5 points or more from a baseline score of 0 as confirmed after 24 weeks. They defined 24-week sustained worsening on the MSFC as worsening of 20% or more on the Timed 25-Foot Walk, worsening of 20% or more on Nine-Hole Peg Test, or a decrease of four or more points on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test sustained for 24 weeks.

Of the 1,841 patients enrolled in DECIDE, 922 were randomized to interferon beta-1a, and 919 were randomized to daclizumab beta. The treatment groups were well balanced in terms of demographic characteristics. Patients’ mean age was approximately 36 years, 68% of participants were female, and 90% of patients were white. Mean time since diagnosis at baseline was about 4 years, mean number of relapses in the previous year was 1.6, and mean baseline EDSS score was 2.5.

Daclizumab beta was associated with a lower risk of 24-week confirmed disability progression, compared with interferon beta-1a, in all subgroups. Patients aged 35 years or younger had the greatest risk reduction.

The proportion of patients who had 24-week sustained worsening on the MSFC at week 96 was 24% for daclizumab beta and 28% for interferon beta-1a. In the whole study population, daclizumab beta reduced the risk of this outcome by 20%, compared with interferon beta-1a. Daclizumab beta resulted in improved outcomes among all subgroups, compared with interferon beta-1a.

In addition, daclizumab beta reduced the risk of a clinically meaningful worsening of MSIS-29 PHYS at week 96 by 24%, compared with interferon beta-1a. The investigators observed trends favoring daclizumab beta in all subgroups.

“These analyses should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating for future studies,” said Dr. Cohan and colleagues. They observed that some of the subgroups analyzed had small sample sizes and that no adjustments were made for multiple testing. Nevertheless, the results suggest that daclizumab beta has superior efficacy, compared with interferon beta-1a, regardless of patients’ demographic and disease characteristics, they concluded.

Biogen and AbbVie Biotherapeutics supported the study.

SOURCE: Cohan S et al. Mult Scler J. 2018. doi: 10.1177/1352458517735190.

This article was updated on 3/22/19.

(MS), according to research published in the December 2018 issue of the Multiple Sclerosis Journal. The benefits are observed in the overall patient population, as well as in subgroups of patients based on demographic and disease characteristics.

Biogen and AbbVie, the manufacturers of daclizumab beta, voluntarily removed the therapy from the market in March 2018 because of safety concerns that included reports of severe liver damage and conditions associated with the immune system.

The phase 3 DECIDE study (NCT01064401) compared the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous daclizumab beta (150 mg) every 4 weeks with those of intramuscular interferon beta-1a (30 mcg) once weekly in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Daclizumab beta reduced the risk of 24-week confirmed disability progression as assessed by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) by 27%, compared with interferon beta-1a. Daclizumab beta also was associated with a greater median change from baseline to week 96 in MS Functional Composite (MSFC) score and a 24% reduction in the risk of clinically meaningful worsening on the physical impact subscale of the patient-reported 29-Item MS Impact Scale (MSIS-29 PHYS).

To shed light on the treatment’s effects in various demographic groups and in patients with specific clinical characteristics, Stanley L. Cohan, MD, PhD, medical director of Providence MS Center in Portland, Ore., and colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of DECIDE data to examine the treatment effects of daclizumab beta and interferon beta-1a on patient disability or impairment in specific patient subgroups. The investigators examined results according to demographic characteristics, such as age (that is, 35 years or younger and older than 35 years) and sex. They also examined results in subgroups with the following baseline disease characteristics: disability (as defined by EDSS score), relapses in the previous 12 months, disease duration, presence of gadolinium enhancing lesions, T2 hyperintense lesion volume, disease activity, prior use of disease-modifying treatment, and prior use of interferon beta.

Dr. Cohan and colleagues focused on the following three outcome measures: 24-week confirmed disability progression (as measured by EDSS), 24-week sustained worsening on the MSFC, and the proportion of patients with clinically meaningful worsening in MSIS-29 PHYS at week 96. The researchers defined 24-week confirmed disability progression as an increase in the EDSS score of one or more points from a baseline score of 1 or higher or 1.5 points or more from a baseline score of 0 as confirmed after 24 weeks. They defined 24-week sustained worsening on the MSFC as worsening of 20% or more on the Timed 25-Foot Walk, worsening of 20% or more on Nine-Hole Peg Test, or a decrease of four or more points on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test sustained for 24 weeks.

Of the 1,841 patients enrolled in DECIDE, 922 were randomized to interferon beta-1a, and 919 were randomized to daclizumab beta. The treatment groups were well balanced in terms of demographic characteristics. Patients’ mean age was approximately 36 years, 68% of participants were female, and 90% of patients were white. Mean time since diagnosis at baseline was about 4 years, mean number of relapses in the previous year was 1.6, and mean baseline EDSS score was 2.5.

Daclizumab beta was associated with a lower risk of 24-week confirmed disability progression, compared with interferon beta-1a, in all subgroups. Patients aged 35 years or younger had the greatest risk reduction.

The proportion of patients who had 24-week sustained worsening on the MSFC at week 96 was 24% for daclizumab beta and 28% for interferon beta-1a. In the whole study population, daclizumab beta reduced the risk of this outcome by 20%, compared with interferon beta-1a. Daclizumab beta resulted in improved outcomes among all subgroups, compared with interferon beta-1a.

In addition, daclizumab beta reduced the risk of a clinically meaningful worsening of MSIS-29 PHYS at week 96 by 24%, compared with interferon beta-1a. The investigators observed trends favoring daclizumab beta in all subgroups.