User login

American Headache Society updates guideline on neuroimaging for migraine

Migraine with atypical features may require neuroimaging, according to the guideline. These include an unusual aura; change in clinical features; a first or worst migraine; a migraine that presents with brainstem aura, confusion, or motor manifestation; migraine accompaniments in later life; headaches that are side-locked or posttraumatic; and aura that presents without headache.

Assessing the evidence

The recommendation to avoid MRI or CT in otherwise neurologically normal patients with migraine carried a grade A recommendation from the American Headache Society, while the specific considerations for neuroimaging was based on consensus and carried a grade C recommendation, according to lead author Randolph W. Evans, MD, of the department of neurology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and colleagues.

The recommendations, published in the journal Headache (2020 Feb;60(2):318-36), came from a systematic review of 23 studies of adults at least 18 years old who underwent MRI or CT during outpatient treatment for migraine between 1973 and 2018. Ten studies looked at CT neuroimaging in patients with migraine, nine studies examined MRI neuroimaging alone in patients with migraine, and four studies contained adults with headache or migraine who underwent either MRI or CT. The majority of studies analyzed were retrospective or cross-sectional in nature, while four studies were prospective observational studies.

Dr. Evans and colleagues noted that neuroimaging for patients with suspected migraine is ordered for a variety of reasons, such as excluding conditions that aren’t migraine, diagnostic certainty, cognitive bias, practice workflow, medicolegal concerns, addressing patient and family anxiety, and addressing clinician anxiety. Neuroimaging also can be costly, they said, adding up to an estimated $1 billion annually according to one study, and can lead to additional testing from findings that may not be clinically significant.

Good advice, with caveats

In an interview, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, said that while he generally does not like broad guideline recommendations, the recommendation made by the American Headache Society to avoid neuroimaging in patients with a normal neurological examination without any atypical features and red flags “takes most of the important factors into consideration and will work almost all the time.” The recommendation made by consensus for specific considerations of neuroimaging was issued by top headache specialists in the United States who reviewed the data, and it is unlikely a patient with a migraine as diagnosed by the International Classification of Headache Disorders with a normal neurological examination would have a significant abnormality that would appear with imaging, Dr. Rapoport said.

“If everyone caring for migraine patients knew these recommendations, and used them unless the patients fit the exclusions mentioned, we would have more efficient clinical practice and save lots of money on unnecessary scanning,” he said.

However, Dr. Rapoport, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, founder of the New England Center for Headache, and past president of The International Headache Society, said that not all clinicians will be convinced by the American Headache Society’s recommendations.

“Various third parties often jump on society recommendations or guidelines and prevent smart clinicians from doing what they need to do when they want to disregard the recommendation or guideline,” he explained. “More importantly, if a physician feels the need to think out of the box and image a patient without a clear reason, and the patient cannot pay for the scan when a medical insurance company refuses to authorize it, there can be a bad result if the patient does not get the study.”

Dr. Rapoport noted that the guideline does not address situations where neuroimaging may not pick up conditions that lead to migraine, such as a subarachnoid or subdural hemorrhage, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, or early aspects of low cerebrospinal fluid pressure syndrome. Anxiety on the part of the patient or the clinician is another area that can be addressed by future research, he said.

“If the clinician does a good job of explaining the odds of anything significant being found with a typical migraine history and normal examination, and the patient says [they] need an MRI with contrast to be sure, it will be difficult to dissuade them,” said Dr. Rapoport. “If you don’t order one, they will find a way to get one. If it is abnormal, you could be in trouble. Also, if the clinician has no good reason to do a scan but has anxiety about what is being missed, it will probably get done.”

There was no funding source for the guidelines. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board memberships, investigator appointments, speakers bureau positions, research support, and consultancies for a variety of pharmaceutical companies, agencies, institutions, publishers, and other organizations.

Migraine with atypical features may require neuroimaging, according to the guideline. These include an unusual aura; change in clinical features; a first or worst migraine; a migraine that presents with brainstem aura, confusion, or motor manifestation; migraine accompaniments in later life; headaches that are side-locked or posttraumatic; and aura that presents without headache.

Assessing the evidence

The recommendation to avoid MRI or CT in otherwise neurologically normal patients with migraine carried a grade A recommendation from the American Headache Society, while the specific considerations for neuroimaging was based on consensus and carried a grade C recommendation, according to lead author Randolph W. Evans, MD, of the department of neurology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and colleagues.

The recommendations, published in the journal Headache (2020 Feb;60(2):318-36), came from a systematic review of 23 studies of adults at least 18 years old who underwent MRI or CT during outpatient treatment for migraine between 1973 and 2018. Ten studies looked at CT neuroimaging in patients with migraine, nine studies examined MRI neuroimaging alone in patients with migraine, and four studies contained adults with headache or migraine who underwent either MRI or CT. The majority of studies analyzed were retrospective or cross-sectional in nature, while four studies were prospective observational studies.

Dr. Evans and colleagues noted that neuroimaging for patients with suspected migraine is ordered for a variety of reasons, such as excluding conditions that aren’t migraine, diagnostic certainty, cognitive bias, practice workflow, medicolegal concerns, addressing patient and family anxiety, and addressing clinician anxiety. Neuroimaging also can be costly, they said, adding up to an estimated $1 billion annually according to one study, and can lead to additional testing from findings that may not be clinically significant.

Good advice, with caveats

In an interview, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, said that while he generally does not like broad guideline recommendations, the recommendation made by the American Headache Society to avoid neuroimaging in patients with a normal neurological examination without any atypical features and red flags “takes most of the important factors into consideration and will work almost all the time.” The recommendation made by consensus for specific considerations of neuroimaging was issued by top headache specialists in the United States who reviewed the data, and it is unlikely a patient with a migraine as diagnosed by the International Classification of Headache Disorders with a normal neurological examination would have a significant abnormality that would appear with imaging, Dr. Rapoport said.

“If everyone caring for migraine patients knew these recommendations, and used them unless the patients fit the exclusions mentioned, we would have more efficient clinical practice and save lots of money on unnecessary scanning,” he said.

However, Dr. Rapoport, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, founder of the New England Center for Headache, and past president of The International Headache Society, said that not all clinicians will be convinced by the American Headache Society’s recommendations.

“Various third parties often jump on society recommendations or guidelines and prevent smart clinicians from doing what they need to do when they want to disregard the recommendation or guideline,” he explained. “More importantly, if a physician feels the need to think out of the box and image a patient without a clear reason, and the patient cannot pay for the scan when a medical insurance company refuses to authorize it, there can be a bad result if the patient does not get the study.”

Dr. Rapoport noted that the guideline does not address situations where neuroimaging may not pick up conditions that lead to migraine, such as a subarachnoid or subdural hemorrhage, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, or early aspects of low cerebrospinal fluid pressure syndrome. Anxiety on the part of the patient or the clinician is another area that can be addressed by future research, he said.

“If the clinician does a good job of explaining the odds of anything significant being found with a typical migraine history and normal examination, and the patient says [they] need an MRI with contrast to be sure, it will be difficult to dissuade them,” said Dr. Rapoport. “If you don’t order one, they will find a way to get one. If it is abnormal, you could be in trouble. Also, if the clinician has no good reason to do a scan but has anxiety about what is being missed, it will probably get done.”

There was no funding source for the guidelines. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board memberships, investigator appointments, speakers bureau positions, research support, and consultancies for a variety of pharmaceutical companies, agencies, institutions, publishers, and other organizations.

Migraine with atypical features may require neuroimaging, according to the guideline. These include an unusual aura; change in clinical features; a first or worst migraine; a migraine that presents with brainstem aura, confusion, or motor manifestation; migraine accompaniments in later life; headaches that are side-locked or posttraumatic; and aura that presents without headache.

Assessing the evidence

The recommendation to avoid MRI or CT in otherwise neurologically normal patients with migraine carried a grade A recommendation from the American Headache Society, while the specific considerations for neuroimaging was based on consensus and carried a grade C recommendation, according to lead author Randolph W. Evans, MD, of the department of neurology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and colleagues.

The recommendations, published in the journal Headache (2020 Feb;60(2):318-36), came from a systematic review of 23 studies of adults at least 18 years old who underwent MRI or CT during outpatient treatment for migraine between 1973 and 2018. Ten studies looked at CT neuroimaging in patients with migraine, nine studies examined MRI neuroimaging alone in patients with migraine, and four studies contained adults with headache or migraine who underwent either MRI or CT. The majority of studies analyzed were retrospective or cross-sectional in nature, while four studies were prospective observational studies.

Dr. Evans and colleagues noted that neuroimaging for patients with suspected migraine is ordered for a variety of reasons, such as excluding conditions that aren’t migraine, diagnostic certainty, cognitive bias, practice workflow, medicolegal concerns, addressing patient and family anxiety, and addressing clinician anxiety. Neuroimaging also can be costly, they said, adding up to an estimated $1 billion annually according to one study, and can lead to additional testing from findings that may not be clinically significant.

Good advice, with caveats

In an interview, Alan M. Rapoport, MD, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, said that while he generally does not like broad guideline recommendations, the recommendation made by the American Headache Society to avoid neuroimaging in patients with a normal neurological examination without any atypical features and red flags “takes most of the important factors into consideration and will work almost all the time.” The recommendation made by consensus for specific considerations of neuroimaging was issued by top headache specialists in the United States who reviewed the data, and it is unlikely a patient with a migraine as diagnosed by the International Classification of Headache Disorders with a normal neurological examination would have a significant abnormality that would appear with imaging, Dr. Rapoport said.

“If everyone caring for migraine patients knew these recommendations, and used them unless the patients fit the exclusions mentioned, we would have more efficient clinical practice and save lots of money on unnecessary scanning,” he said.

However, Dr. Rapoport, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, founder of the New England Center for Headache, and past president of The International Headache Society, said that not all clinicians will be convinced by the American Headache Society’s recommendations.

“Various third parties often jump on society recommendations or guidelines and prevent smart clinicians from doing what they need to do when they want to disregard the recommendation or guideline,” he explained. “More importantly, if a physician feels the need to think out of the box and image a patient without a clear reason, and the patient cannot pay for the scan when a medical insurance company refuses to authorize it, there can be a bad result if the patient does not get the study.”

Dr. Rapoport noted that the guideline does not address situations where neuroimaging may not pick up conditions that lead to migraine, such as a subarachnoid or subdural hemorrhage, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, or early aspects of low cerebrospinal fluid pressure syndrome. Anxiety on the part of the patient or the clinician is another area that can be addressed by future research, he said.

“If the clinician does a good job of explaining the odds of anything significant being found with a typical migraine history and normal examination, and the patient says [they] need an MRI with contrast to be sure, it will be difficult to dissuade them,” said Dr. Rapoport. “If you don’t order one, they will find a way to get one. If it is abnormal, you could be in trouble. Also, if the clinician has no good reason to do a scan but has anxiety about what is being missed, it will probably get done.”

There was no funding source for the guidelines. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board memberships, investigator appointments, speakers bureau positions, research support, and consultancies for a variety of pharmaceutical companies, agencies, institutions, publishers, and other organizations.

FROM HEADACHE

HIV free 30 months after stem cell transplant, is the London patient cured?

A patient with HIV remission induced by stem cell transplantation continues to be disease free at the 30-month mark.

The individual, referred to as the London patient, received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) for stage IVB Hodgkin lymphoma. The transplant donor was homozygous for the CCR5 delta-32 mutation, which confers immunity to HIV because there’s no point of entry for the virus into immune cells.

After extensive sampling of various tissues, including gut, lymph node, blood, semen, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Ravindra Kumar Gupta, MD, PhD, and colleagues found no detectable virus that was competent to replicate. However, they reported that the testing did detect some “fossilized” remnants of HIV DNA persisting in certain tissues.

The results were shared in a video presentation of the research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

The London patient’s HIV status had been reported the previous year at CROI 2019, but only blood samples were used in that analysis.

In a commentary accompanying the simultaneously published study in the Lancet, Jennifer Zerbato, PhD, and Sharon Lewin, FRACP, PHD, FAAHMS, asked: “A key question now for the area of HIV cure is how soon can one know if someone has been cured of HIV?

“We will need more than a handful of patients cured of HIV to really understand the duration of follow-up needed and the likelihood of an unexpected late rebound in virus replication,” continued Dr. Zerbato, of the University of Melbourne, and Dr. Lewin, of the Royal Melbourne Hospital and Monash University, also in Melbourne.

In their ongoing analysis of data from the London patient, Dr. Gupta, a virologist at the University of Cambridge (England), and associates constructed a mathematical model that maps the probability for lifetime remission or cure of HIV against several factors, including the degree of chimerism achieved with the stem cell transplant.

In this model, when chimerism reaches 80% in total HIV target cells, the probability of remission for life is 98%; when donor chimerism reaches 90%, the probability of lifetime remission is greater than 99%. Peripheral T-cell chimerism in the London patient has held steady at 99%.

Dr. Gupta and associates obtained some testing opportunistically: A PET-CT scan revealed an axillary lymph node that was biopsied after it was found to have avid radiotracer uptake. Similarly, the CSF sample was obtained in the course of a work-up for some neurologic symptoms that the London patient was having.

In contrast to the first patient who achieved ongoing HIV remission from a pair of stem cell transplants received over 13 years ago – the Berlin patient – the London patient did not receive whole-body radiation, but rather underwent a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen. The London patient experienced a bout of gut graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) about 2 months after his transplant, but has been free of GVHD in the interval. He hasn’t taken cytotoxic agents or any GVHD prophylaxis since 6 months post transplant.

Though there’s no sign of HIV that’s competent to replicate, “the London patient has shown somewhat slow CD4 reconstitution,” said Dr. Gupta and coauthors in discussing the results.

The patient had a reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) about 21 months after analytic treatment interruption (ATI) of antiretroviral therapy that was managed without any specific treatment, but he hasn’t experienced any opportunistic infections. However, his CD4 count didn’t rebound to pretransplant levels until 28 months after ATI. At that point, his CD4 count was 430 cells per mcL, or 23.5% of total T cells. The CD4:CD8 ratio was 0.86; normal range is 1.5-2.5.

The researchers used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) to look for packaging site and envelope (env) DNA fragments, and droplet digital PCR to quantify HIV-1 DNA.

The patient’s HIV-1 plasma load measured at 30 months post ATI on an ultrasensitive assay was below the lower limit of detection (less than 1 copy per mL). Semen viremia measured at 21 months was also below the lower limit of detection, as was CSF measured at 25 months.

Samples were taken from the patient’s rectum, cecum, sigmoid colon, and terminal ileum during a colonoscopy conducted 22 months post ATI; all tested negative for HIV DNA via droplet digital PCR.

The lymph node had large numbers of EBV-positive cells and was positive for HIV-1 env and long-terminal repeat by double-drop PCR, but no integrase DNA was detected. Additionally, no intact proviral DNA was found on assay.

Dr. Gupta and associates speculated that “EBV reactivation could have triggered EBV-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses and proliferation, potentially including CD4 T cells containing HIV-1 DNA.” Supporting this hypothesis, EBV-specific CD8 T-cell responses in peripheral blood were “robust,” and the researchers also saw some CD4 response.

“Similar to the Berlin patient, highly sensitive tests showed very low levels of so-called fossilized HIV-1 DNA in some tissue samples from the London patient. Residual HIV-1 DNA and axillary lymph node tissue could represent a defective clone that expanded during hyperplasia within the lymph note sampled,” noted Dr. Gupta and coauthors.

Responses of CD4 and CD8 T cells to HIV have also remained below the limit of detection, though cytomegalovirus-specific responses persist in the London patient.

As with the Berlin patient, standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing has remained positive in the London patient. “Standard ELISA testing, therefore, cannot be used as a marker for cure, although more work needs to be done to assess the role of detuned low-avidity antibody assays in defining cure,” noted Dr. Gupta and associates.

The ongoing follow-up plan for the London patient is to obtain viral load testing twice yearly up to 5 years post ATI, and then obtain yearly tests for a total of 10 years. Ongoing testing will confirm the investigators’ belief that “these findings probably represent the second recorded HIV-1 cure after CCR5 delta-32/delta-32 allo-HSCT, with evidence of residual low-level HIV-1 DNA.”

Dr. Zerbato and Dr. Lewin advised cautious optimism and ongoing surveillance: “In view of the many cells sampled in this case, and the absence of any intact virus, is the London patient truly cured? The additional data provided in this follow-up case report is certainly exciting and encouraging but, in the end, only time will tell.”

Dr. Gupta reported being a consultant for ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences; several coauthors also reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The work was funded by amfAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and the Wellcome Trust. Dr. Lewin reported grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the National Institutes of Health, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, Gilead Sciences, Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Leidos, the Wellcome Trust, the Australian Centre for HIV and Hepatitis Virology Research, and the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium. Dr. Zerbato reported grants from the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium,

SOURCE: Gupta R et al. Lancet. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-3018(20)30069-2.

A patient with HIV remission induced by stem cell transplantation continues to be disease free at the 30-month mark.

The individual, referred to as the London patient, received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) for stage IVB Hodgkin lymphoma. The transplant donor was homozygous for the CCR5 delta-32 mutation, which confers immunity to HIV because there’s no point of entry for the virus into immune cells.

After extensive sampling of various tissues, including gut, lymph node, blood, semen, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Ravindra Kumar Gupta, MD, PhD, and colleagues found no detectable virus that was competent to replicate. However, they reported that the testing did detect some “fossilized” remnants of HIV DNA persisting in certain tissues.

The results were shared in a video presentation of the research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

The London patient’s HIV status had been reported the previous year at CROI 2019, but only blood samples were used in that analysis.

In a commentary accompanying the simultaneously published study in the Lancet, Jennifer Zerbato, PhD, and Sharon Lewin, FRACP, PHD, FAAHMS, asked: “A key question now for the area of HIV cure is how soon can one know if someone has been cured of HIV?

“We will need more than a handful of patients cured of HIV to really understand the duration of follow-up needed and the likelihood of an unexpected late rebound in virus replication,” continued Dr. Zerbato, of the University of Melbourne, and Dr. Lewin, of the Royal Melbourne Hospital and Monash University, also in Melbourne.

In their ongoing analysis of data from the London patient, Dr. Gupta, a virologist at the University of Cambridge (England), and associates constructed a mathematical model that maps the probability for lifetime remission or cure of HIV against several factors, including the degree of chimerism achieved with the stem cell transplant.

In this model, when chimerism reaches 80% in total HIV target cells, the probability of remission for life is 98%; when donor chimerism reaches 90%, the probability of lifetime remission is greater than 99%. Peripheral T-cell chimerism in the London patient has held steady at 99%.

Dr. Gupta and associates obtained some testing opportunistically: A PET-CT scan revealed an axillary lymph node that was biopsied after it was found to have avid radiotracer uptake. Similarly, the CSF sample was obtained in the course of a work-up for some neurologic symptoms that the London patient was having.

In contrast to the first patient who achieved ongoing HIV remission from a pair of stem cell transplants received over 13 years ago – the Berlin patient – the London patient did not receive whole-body radiation, but rather underwent a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen. The London patient experienced a bout of gut graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) about 2 months after his transplant, but has been free of GVHD in the interval. He hasn’t taken cytotoxic agents or any GVHD prophylaxis since 6 months post transplant.

Though there’s no sign of HIV that’s competent to replicate, “the London patient has shown somewhat slow CD4 reconstitution,” said Dr. Gupta and coauthors in discussing the results.

The patient had a reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) about 21 months after analytic treatment interruption (ATI) of antiretroviral therapy that was managed without any specific treatment, but he hasn’t experienced any opportunistic infections. However, his CD4 count didn’t rebound to pretransplant levels until 28 months after ATI. At that point, his CD4 count was 430 cells per mcL, or 23.5% of total T cells. The CD4:CD8 ratio was 0.86; normal range is 1.5-2.5.

The researchers used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) to look for packaging site and envelope (env) DNA fragments, and droplet digital PCR to quantify HIV-1 DNA.

The patient’s HIV-1 plasma load measured at 30 months post ATI on an ultrasensitive assay was below the lower limit of detection (less than 1 copy per mL). Semen viremia measured at 21 months was also below the lower limit of detection, as was CSF measured at 25 months.

Samples were taken from the patient’s rectum, cecum, sigmoid colon, and terminal ileum during a colonoscopy conducted 22 months post ATI; all tested negative for HIV DNA via droplet digital PCR.

The lymph node had large numbers of EBV-positive cells and was positive for HIV-1 env and long-terminal repeat by double-drop PCR, but no integrase DNA was detected. Additionally, no intact proviral DNA was found on assay.

Dr. Gupta and associates speculated that “EBV reactivation could have triggered EBV-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses and proliferation, potentially including CD4 T cells containing HIV-1 DNA.” Supporting this hypothesis, EBV-specific CD8 T-cell responses in peripheral blood were “robust,” and the researchers also saw some CD4 response.

“Similar to the Berlin patient, highly sensitive tests showed very low levels of so-called fossilized HIV-1 DNA in some tissue samples from the London patient. Residual HIV-1 DNA and axillary lymph node tissue could represent a defective clone that expanded during hyperplasia within the lymph note sampled,” noted Dr. Gupta and coauthors.

Responses of CD4 and CD8 T cells to HIV have also remained below the limit of detection, though cytomegalovirus-specific responses persist in the London patient.

As with the Berlin patient, standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing has remained positive in the London patient. “Standard ELISA testing, therefore, cannot be used as a marker for cure, although more work needs to be done to assess the role of detuned low-avidity antibody assays in defining cure,” noted Dr. Gupta and associates.

The ongoing follow-up plan for the London patient is to obtain viral load testing twice yearly up to 5 years post ATI, and then obtain yearly tests for a total of 10 years. Ongoing testing will confirm the investigators’ belief that “these findings probably represent the second recorded HIV-1 cure after CCR5 delta-32/delta-32 allo-HSCT, with evidence of residual low-level HIV-1 DNA.”

Dr. Zerbato and Dr. Lewin advised cautious optimism and ongoing surveillance: “In view of the many cells sampled in this case, and the absence of any intact virus, is the London patient truly cured? The additional data provided in this follow-up case report is certainly exciting and encouraging but, in the end, only time will tell.”

Dr. Gupta reported being a consultant for ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences; several coauthors also reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The work was funded by amfAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and the Wellcome Trust. Dr. Lewin reported grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the National Institutes of Health, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, Gilead Sciences, Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Leidos, the Wellcome Trust, the Australian Centre for HIV and Hepatitis Virology Research, and the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium. Dr. Zerbato reported grants from the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium,

SOURCE: Gupta R et al. Lancet. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-3018(20)30069-2.

A patient with HIV remission induced by stem cell transplantation continues to be disease free at the 30-month mark.

The individual, referred to as the London patient, received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) for stage IVB Hodgkin lymphoma. The transplant donor was homozygous for the CCR5 delta-32 mutation, which confers immunity to HIV because there’s no point of entry for the virus into immune cells.

After extensive sampling of various tissues, including gut, lymph node, blood, semen, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Ravindra Kumar Gupta, MD, PhD, and colleagues found no detectable virus that was competent to replicate. However, they reported that the testing did detect some “fossilized” remnants of HIV DNA persisting in certain tissues.

The results were shared in a video presentation of the research during the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections, which was presented online this year. CROI organizers chose to hold a virtual meeting because of concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

The London patient’s HIV status had been reported the previous year at CROI 2019, but only blood samples were used in that analysis.

In a commentary accompanying the simultaneously published study in the Lancet, Jennifer Zerbato, PhD, and Sharon Lewin, FRACP, PHD, FAAHMS, asked: “A key question now for the area of HIV cure is how soon can one know if someone has been cured of HIV?

“We will need more than a handful of patients cured of HIV to really understand the duration of follow-up needed and the likelihood of an unexpected late rebound in virus replication,” continued Dr. Zerbato, of the University of Melbourne, and Dr. Lewin, of the Royal Melbourne Hospital and Monash University, also in Melbourne.

In their ongoing analysis of data from the London patient, Dr. Gupta, a virologist at the University of Cambridge (England), and associates constructed a mathematical model that maps the probability for lifetime remission or cure of HIV against several factors, including the degree of chimerism achieved with the stem cell transplant.

In this model, when chimerism reaches 80% in total HIV target cells, the probability of remission for life is 98%; when donor chimerism reaches 90%, the probability of lifetime remission is greater than 99%. Peripheral T-cell chimerism in the London patient has held steady at 99%.

Dr. Gupta and associates obtained some testing opportunistically: A PET-CT scan revealed an axillary lymph node that was biopsied after it was found to have avid radiotracer uptake. Similarly, the CSF sample was obtained in the course of a work-up for some neurologic symptoms that the London patient was having.

In contrast to the first patient who achieved ongoing HIV remission from a pair of stem cell transplants received over 13 years ago – the Berlin patient – the London patient did not receive whole-body radiation, but rather underwent a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen. The London patient experienced a bout of gut graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) about 2 months after his transplant, but has been free of GVHD in the interval. He hasn’t taken cytotoxic agents or any GVHD prophylaxis since 6 months post transplant.

Though there’s no sign of HIV that’s competent to replicate, “the London patient has shown somewhat slow CD4 reconstitution,” said Dr. Gupta and coauthors in discussing the results.

The patient had a reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) about 21 months after analytic treatment interruption (ATI) of antiretroviral therapy that was managed without any specific treatment, but he hasn’t experienced any opportunistic infections. However, his CD4 count didn’t rebound to pretransplant levels until 28 months after ATI. At that point, his CD4 count was 430 cells per mcL, or 23.5% of total T cells. The CD4:CD8 ratio was 0.86; normal range is 1.5-2.5.

The researchers used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) to look for packaging site and envelope (env) DNA fragments, and droplet digital PCR to quantify HIV-1 DNA.

The patient’s HIV-1 plasma load measured at 30 months post ATI on an ultrasensitive assay was below the lower limit of detection (less than 1 copy per mL). Semen viremia measured at 21 months was also below the lower limit of detection, as was CSF measured at 25 months.

Samples were taken from the patient’s rectum, cecum, sigmoid colon, and terminal ileum during a colonoscopy conducted 22 months post ATI; all tested negative for HIV DNA via droplet digital PCR.

The lymph node had large numbers of EBV-positive cells and was positive for HIV-1 env and long-terminal repeat by double-drop PCR, but no integrase DNA was detected. Additionally, no intact proviral DNA was found on assay.

Dr. Gupta and associates speculated that “EBV reactivation could have triggered EBV-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses and proliferation, potentially including CD4 T cells containing HIV-1 DNA.” Supporting this hypothesis, EBV-specific CD8 T-cell responses in peripheral blood were “robust,” and the researchers also saw some CD4 response.

“Similar to the Berlin patient, highly sensitive tests showed very low levels of so-called fossilized HIV-1 DNA in some tissue samples from the London patient. Residual HIV-1 DNA and axillary lymph node tissue could represent a defective clone that expanded during hyperplasia within the lymph note sampled,” noted Dr. Gupta and coauthors.

Responses of CD4 and CD8 T cells to HIV have also remained below the limit of detection, though cytomegalovirus-specific responses persist in the London patient.

As with the Berlin patient, standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing has remained positive in the London patient. “Standard ELISA testing, therefore, cannot be used as a marker for cure, although more work needs to be done to assess the role of detuned low-avidity antibody assays in defining cure,” noted Dr. Gupta and associates.

The ongoing follow-up plan for the London patient is to obtain viral load testing twice yearly up to 5 years post ATI, and then obtain yearly tests for a total of 10 years. Ongoing testing will confirm the investigators’ belief that “these findings probably represent the second recorded HIV-1 cure after CCR5 delta-32/delta-32 allo-HSCT, with evidence of residual low-level HIV-1 DNA.”

Dr. Zerbato and Dr. Lewin advised cautious optimism and ongoing surveillance: “In view of the many cells sampled in this case, and the absence of any intact virus, is the London patient truly cured? The additional data provided in this follow-up case report is certainly exciting and encouraging but, in the end, only time will tell.”

Dr. Gupta reported being a consultant for ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences; several coauthors also reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The work was funded by amfAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and the Wellcome Trust. Dr. Lewin reported grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the National Institutes of Health, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, Gilead Sciences, Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Leidos, the Wellcome Trust, the Australian Centre for HIV and Hepatitis Virology Research, and the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium. Dr. Zerbato reported grants from the Melbourne HIV Cure Consortium,

SOURCE: Gupta R et al. Lancet. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.1016/ S2352-3018(20)30069-2.

FROM CROI 2020

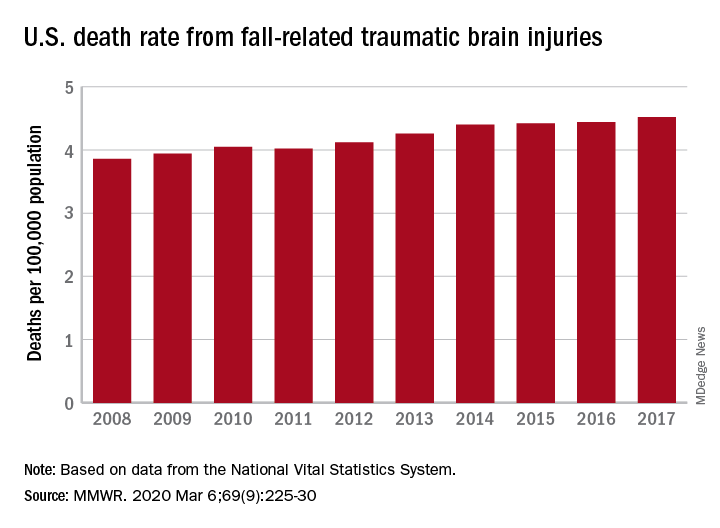

TBI deaths from falls on the rise

A 17% surge in mortality from fall-related traumatic brain injuries from 2008 to 2017 was driven largely by increases among those aged 75 years and older, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, the rate of deaths from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) caused by unintentional falls rose from 3.86 per 100,000 population in 2008 to 4.52 per 100,000 in 2017, as the number of deaths went from 12,311 to 17,408, said Alexis B. Peterson, PhD, and Scott R. Kegler, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

“This increase might be explained by longer survival following the onset of common diseases such as stroke, cancer, and heart disease or be attributable to the increasing population of older adults in the United States,” they suggested in the Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

The rate of fall-related TBI among Americans aged 75 years and older increased by an average of 2.6% per year from 2008 to 2017, compared with 1.8% in those aged 55-74. Over that same time, death rates dropped for those aged 35-44 (–0.3%), 18-34 (–1.1%), and 0-17 (–4.3%), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s multiple cause-of-death database.

The death rate increased fastest in residents of rural areas (2.9% per year), but deaths from fall-related TBI were up at all levels of urbanization. The largest central cities and fringe metro areas were up by 1.4% a year, with larger annual increases seen in medium-size cities (2.1%), small cities (2.2%), and small towns (2.1%), Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said.

Rates of TBI-related mortality in general are higher in rural areas, they noted, and “heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility of resources (e.g., access to high-level trauma centers and rehabilitative services) can result in disparities in postinjury outcomes.”

State-specific rates increased in 45 states, although Alaska was excluded from the analysis because of its small number of cases (less than 20). Increases were significant in 29 states, but none of the changes were significant in the 4 states with lower rates at the end of the study period, the investigators reported.

“In older adults, evidence-based fall prevention strategies can prevent falls and avert costly medical expenditures,” Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said, suggesting that health care providers “consider prescribing exercises that incorporate balance, strength and gait activities, such as tai chi, and reviewing and managing medications linked to falls.”

SOURCE: Peterson AB, Kegler SR. MMWR. 2019 Mar 6;69(9):225-30.

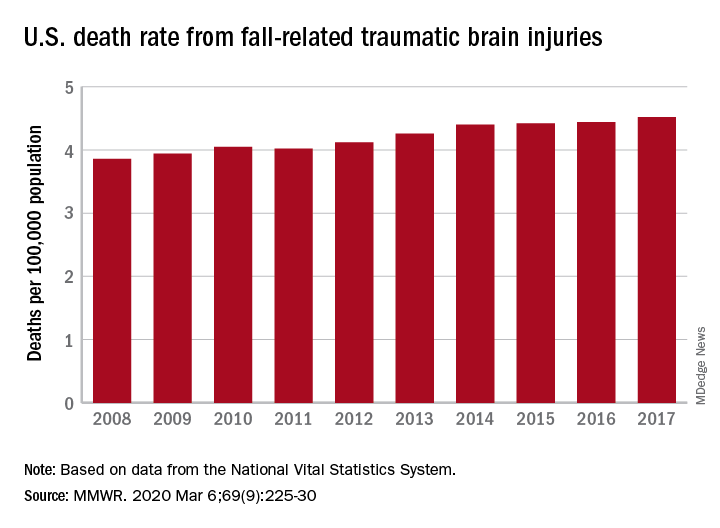

A 17% surge in mortality from fall-related traumatic brain injuries from 2008 to 2017 was driven largely by increases among those aged 75 years and older, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, the rate of deaths from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) caused by unintentional falls rose from 3.86 per 100,000 population in 2008 to 4.52 per 100,000 in 2017, as the number of deaths went from 12,311 to 17,408, said Alexis B. Peterson, PhD, and Scott R. Kegler, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

“This increase might be explained by longer survival following the onset of common diseases such as stroke, cancer, and heart disease or be attributable to the increasing population of older adults in the United States,” they suggested in the Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

The rate of fall-related TBI among Americans aged 75 years and older increased by an average of 2.6% per year from 2008 to 2017, compared with 1.8% in those aged 55-74. Over that same time, death rates dropped for those aged 35-44 (–0.3%), 18-34 (–1.1%), and 0-17 (–4.3%), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s multiple cause-of-death database.

The death rate increased fastest in residents of rural areas (2.9% per year), but deaths from fall-related TBI were up at all levels of urbanization. The largest central cities and fringe metro areas were up by 1.4% a year, with larger annual increases seen in medium-size cities (2.1%), small cities (2.2%), and small towns (2.1%), Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said.

Rates of TBI-related mortality in general are higher in rural areas, they noted, and “heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility of resources (e.g., access to high-level trauma centers and rehabilitative services) can result in disparities in postinjury outcomes.”

State-specific rates increased in 45 states, although Alaska was excluded from the analysis because of its small number of cases (less than 20). Increases were significant in 29 states, but none of the changes were significant in the 4 states with lower rates at the end of the study period, the investigators reported.

“In older adults, evidence-based fall prevention strategies can prevent falls and avert costly medical expenditures,” Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said, suggesting that health care providers “consider prescribing exercises that incorporate balance, strength and gait activities, such as tai chi, and reviewing and managing medications linked to falls.”

SOURCE: Peterson AB, Kegler SR. MMWR. 2019 Mar 6;69(9):225-30.

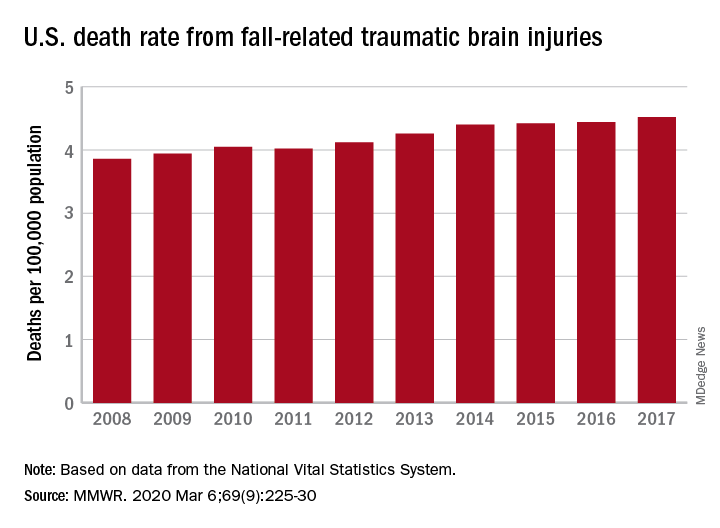

A 17% surge in mortality from fall-related traumatic brain injuries from 2008 to 2017 was driven largely by increases among those aged 75 years and older, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, the rate of deaths from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) caused by unintentional falls rose from 3.86 per 100,000 population in 2008 to 4.52 per 100,000 in 2017, as the number of deaths went from 12,311 to 17,408, said Alexis B. Peterson, PhD, and Scott R. Kegler, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

“This increase might be explained by longer survival following the onset of common diseases such as stroke, cancer, and heart disease or be attributable to the increasing population of older adults in the United States,” they suggested in the Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

The rate of fall-related TBI among Americans aged 75 years and older increased by an average of 2.6% per year from 2008 to 2017, compared with 1.8% in those aged 55-74. Over that same time, death rates dropped for those aged 35-44 (–0.3%), 18-34 (–1.1%), and 0-17 (–4.3%), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s multiple cause-of-death database.

The death rate increased fastest in residents of rural areas (2.9% per year), but deaths from fall-related TBI were up at all levels of urbanization. The largest central cities and fringe metro areas were up by 1.4% a year, with larger annual increases seen in medium-size cities (2.1%), small cities (2.2%), and small towns (2.1%), Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said.

Rates of TBI-related mortality in general are higher in rural areas, they noted, and “heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility of resources (e.g., access to high-level trauma centers and rehabilitative services) can result in disparities in postinjury outcomes.”

State-specific rates increased in 45 states, although Alaska was excluded from the analysis because of its small number of cases (less than 20). Increases were significant in 29 states, but none of the changes were significant in the 4 states with lower rates at the end of the study period, the investigators reported.

“In older adults, evidence-based fall prevention strategies can prevent falls and avert costly medical expenditures,” Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said, suggesting that health care providers “consider prescribing exercises that incorporate balance, strength and gait activities, such as tai chi, and reviewing and managing medications linked to falls.”

SOURCE: Peterson AB, Kegler SR. MMWR. 2019 Mar 6;69(9):225-30.

FROM MMWR

Stress-related disorders linked to later neurodegenerative diseases

Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress reaction, adjustment disorder, or other stress reactions had an 80% increased risk of vascular neurodegenerative diseases, according to results of the study, which was based on Swedish population registry data.

Risk of primary neurodegenerative diseases was increased as well in people with those conditions, but only by 31%, according to lead author Huan Song, MD, PhD, of Sichuan University in Chengdu, China.

“The stronger association observed for neurodegenerative diseases with a vascular component, compared with primary neurodegenerative diseases, suggested a considerable role of a possible cerebrovascular pathway,” Dr. Song and coauthors said in a report on the study appearing in JAMA Neurology.

While some previous studies have linked stress-related disorders to neurodegenerative diseases – particularly PTSD and dementia – this is believed to be the first, according to the investigators, to comprehensively evaluate all stress-related disorders in relation to the most common neurodegenerative conditions.

When considering neurodegenerative conditions separately, they found a statistically significant association between stress-related disorders and Alzheimer’s disease, while linkages with Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) were “comparable” but associations did not reach statistical significance, according to investigators.

Based on these findings, stress reduction should be recommended in addition to daily physical activity, mental activity, and a heart-healthy diet to potentially reduce risk of onset or worsening of cognitive decline, according to Chun Lim, MD, PhD, medical director of the cognitive neurology unit at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“We don’t really have great evidence that anything slows down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, but there are some suggestions that for people who lead heart-healthy lifestyles or adhere to a Mediterranean diet, fewer develop cognitive issues over 5-10 years,” Dr. Lim said in an interview. “Because of this paper, stress reduction may be one additional way to hopefully help these patients these patients that have or are concerned about cognitive issues.”

The population-matched cohort of the study included 61,748 individuals with stress-related disorders and 595,335 matched individuals without those disorders, while the sibling-matched cohort included 44,839 individuals with those disorders and 78,482 without. The median age at the start of follow-up was 47 years and 39.4% of those with stress-related disorders were male.

During follow-up, the incidence of neurodegenerative diseases per 1,000 person-years was 1.50 for individuals with stress-related disorders, versus 0.82 for those without stress-related disorders, according to the report. Risk of primary neurodegenerative diseases was increased among those with stress-related disorders, compared with those without, with a hazard ratio of 1.31 (95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.48). However, the risk of vascular neurodegenerative diseases was significantly higher, with an HR of 1.80 (95% CI, 1.40-2.31; P = .03 for the difference between hazard ratios).

Results of the matched sibling cohort supported results of the population-matched cohort, though the elevated risk of vascular neurodegenerative diseases among those with stress-related disorders was “slightly lower” than in the population-based cohort, Dr. Song and coauthors wrote in their report.

Beyond causing a host of hormonal and medical issues, stress can lead to sleep issues that may have long-term consequences, Dr. Lim noted in the interview.

“There’s some thought that quality sleep is important for memory formation, and if people are under a fair amount of stress and they have really poor sleep, that can also lead to cognitive issues including memory impairment,” he said.

“There are these multiple avenues that may be contributing to the accelerated development of these kinds of issues,” he added, “so I think this paper suggests more ways to counsel the patients about using lifestyle modifications to slow down the development of these cognitive impairments.”

Funding for the study came from the Swedish Research Council, Icelandic Research Fund; ,European Research Council the Karolinska Institutet, Swedish Research Council, and West China Hospital. Authors of the study provided disclosures related to those organizations as well as Shire/Takeda and Evolan.

SOURCE: Song H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Mar 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0117.

Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress reaction, adjustment disorder, or other stress reactions had an 80% increased risk of vascular neurodegenerative diseases, according to results of the study, which was based on Swedish population registry data.

Risk of primary neurodegenerative diseases was increased as well in people with those conditions, but only by 31%, according to lead author Huan Song, MD, PhD, of Sichuan University in Chengdu, China.

“The stronger association observed for neurodegenerative diseases with a vascular component, compared with primary neurodegenerative diseases, suggested a considerable role of a possible cerebrovascular pathway,” Dr. Song and coauthors said in a report on the study appearing in JAMA Neurology.

While some previous studies have linked stress-related disorders to neurodegenerative diseases – particularly PTSD and dementia – this is believed to be the first, according to the investigators, to comprehensively evaluate all stress-related disorders in relation to the most common neurodegenerative conditions.

When considering neurodegenerative conditions separately, they found a statistically significant association between stress-related disorders and Alzheimer’s disease, while linkages with Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) were “comparable” but associations did not reach statistical significance, according to investigators.

Based on these findings, stress reduction should be recommended in addition to daily physical activity, mental activity, and a heart-healthy diet to potentially reduce risk of onset or worsening of cognitive decline, according to Chun Lim, MD, PhD, medical director of the cognitive neurology unit at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“We don’t really have great evidence that anything slows down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, but there are some suggestions that for people who lead heart-healthy lifestyles or adhere to a Mediterranean diet, fewer develop cognitive issues over 5-10 years,” Dr. Lim said in an interview. “Because of this paper, stress reduction may be one additional way to hopefully help these patients these patients that have or are concerned about cognitive issues.”

The population-matched cohort of the study included 61,748 individuals with stress-related disorders and 595,335 matched individuals without those disorders, while the sibling-matched cohort included 44,839 individuals with those disorders and 78,482 without. The median age at the start of follow-up was 47 years and 39.4% of those with stress-related disorders were male.

During follow-up, the incidence of neurodegenerative diseases per 1,000 person-years was 1.50 for individuals with stress-related disorders, versus 0.82 for those without stress-related disorders, according to the report. Risk of primary neurodegenerative diseases was increased among those with stress-related disorders, compared with those without, with a hazard ratio of 1.31 (95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.48). However, the risk of vascular neurodegenerative diseases was significantly higher, with an HR of 1.80 (95% CI, 1.40-2.31; P = .03 for the difference between hazard ratios).

Results of the matched sibling cohort supported results of the population-matched cohort, though the elevated risk of vascular neurodegenerative diseases among those with stress-related disorders was “slightly lower” than in the population-based cohort, Dr. Song and coauthors wrote in their report.

Beyond causing a host of hormonal and medical issues, stress can lead to sleep issues that may have long-term consequences, Dr. Lim noted in the interview.

“There’s some thought that quality sleep is important for memory formation, and if people are under a fair amount of stress and they have really poor sleep, that can also lead to cognitive issues including memory impairment,” he said.

“There are these multiple avenues that may be contributing to the accelerated development of these kinds of issues,” he added, “so I think this paper suggests more ways to counsel the patients about using lifestyle modifications to slow down the development of these cognitive impairments.”

Funding for the study came from the Swedish Research Council, Icelandic Research Fund; ,European Research Council the Karolinska Institutet, Swedish Research Council, and West China Hospital. Authors of the study provided disclosures related to those organizations as well as Shire/Takeda and Evolan.

SOURCE: Song H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Mar 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0117.

Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress reaction, adjustment disorder, or other stress reactions had an 80% increased risk of vascular neurodegenerative diseases, according to results of the study, which was based on Swedish population registry data.

Risk of primary neurodegenerative diseases was increased as well in people with those conditions, but only by 31%, according to lead author Huan Song, MD, PhD, of Sichuan University in Chengdu, China.

“The stronger association observed for neurodegenerative diseases with a vascular component, compared with primary neurodegenerative diseases, suggested a considerable role of a possible cerebrovascular pathway,” Dr. Song and coauthors said in a report on the study appearing in JAMA Neurology.

While some previous studies have linked stress-related disorders to neurodegenerative diseases – particularly PTSD and dementia – this is believed to be the first, according to the investigators, to comprehensively evaluate all stress-related disorders in relation to the most common neurodegenerative conditions.

When considering neurodegenerative conditions separately, they found a statistically significant association between stress-related disorders and Alzheimer’s disease, while linkages with Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) were “comparable” but associations did not reach statistical significance, according to investigators.

Based on these findings, stress reduction should be recommended in addition to daily physical activity, mental activity, and a heart-healthy diet to potentially reduce risk of onset or worsening of cognitive decline, according to Chun Lim, MD, PhD, medical director of the cognitive neurology unit at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

“We don’t really have great evidence that anything slows down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, but there are some suggestions that for people who lead heart-healthy lifestyles or adhere to a Mediterranean diet, fewer develop cognitive issues over 5-10 years,” Dr. Lim said in an interview. “Because of this paper, stress reduction may be one additional way to hopefully help these patients these patients that have or are concerned about cognitive issues.”

The population-matched cohort of the study included 61,748 individuals with stress-related disorders and 595,335 matched individuals without those disorders, while the sibling-matched cohort included 44,839 individuals with those disorders and 78,482 without. The median age at the start of follow-up was 47 years and 39.4% of those with stress-related disorders were male.

During follow-up, the incidence of neurodegenerative diseases per 1,000 person-years was 1.50 for individuals with stress-related disorders, versus 0.82 for those without stress-related disorders, according to the report. Risk of primary neurodegenerative diseases was increased among those with stress-related disorders, compared with those without, with a hazard ratio of 1.31 (95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.48). However, the risk of vascular neurodegenerative diseases was significantly higher, with an HR of 1.80 (95% CI, 1.40-2.31; P = .03 for the difference between hazard ratios).

Results of the matched sibling cohort supported results of the population-matched cohort, though the elevated risk of vascular neurodegenerative diseases among those with stress-related disorders was “slightly lower” than in the population-based cohort, Dr. Song and coauthors wrote in their report.

Beyond causing a host of hormonal and medical issues, stress can lead to sleep issues that may have long-term consequences, Dr. Lim noted in the interview.

“There’s some thought that quality sleep is important for memory formation, and if people are under a fair amount of stress and they have really poor sleep, that can also lead to cognitive issues including memory impairment,” he said.

“There are these multiple avenues that may be contributing to the accelerated development of these kinds of issues,” he added, “so I think this paper suggests more ways to counsel the patients about using lifestyle modifications to slow down the development of these cognitive impairments.”

Funding for the study came from the Swedish Research Council, Icelandic Research Fund; ,European Research Council the Karolinska Institutet, Swedish Research Council, and West China Hospital. Authors of the study provided disclosures related to those organizations as well as Shire/Takeda and Evolan.

SOURCE: Song H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Mar 9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0117.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

USPSTF again deems evidence insufficient to recommend cognitive impairment screening in older adults

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has deemed the current evidence “insufficient” to make a recommendation in regard to screening for cognitive impairment in adults aged 65 years or older.

“More research is needed on the effect of screening and early detection of cognitive impairment on important patient, caregiver, and societal outcomes, including decision making, advance planning, and caregiver outcomes,” wrote lead author Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and fellow members of the task force. The statement was published in JAMA.

To update a 2014 recommendation from the USPSTF, which also found insufficient evidence to properly assess cognitive screening’s benefits and harms, the task force commissioned a systematic review of studies applicable to community-dwelling older adults who are not exhibiting signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment. For their statement, “cognitive impairment” is defined as mild cognitive impairment and mild to moderate dementia.

Ultimately, they determined several factors that limited the overall evidence, including the short duration of most trials and the heterogenous nature of interventions and inconsistencies in outcomes reported. Any evidence that suggested improvements was mostly applicable to patients with moderate dementia, meaning “its applicability to a screen-detected population is uncertain.”

Updating 2014 recommendations

Their statement was based on an evidence report, also published in JAMA, in which a team of researchers reviewed 287 studies that included more than 285,000 older adults; 92 of the studies were newly identified, while the other 195 were carried forward from the 2014 recommendation’s review. The researchers sought the answers to five key questions, carrying over the framework from the previous review.

“Despite the accumulation of new data, the conclusions for these key questions are essentially unchanged from the prior review,” wrote lead author Carrie D. Patnode, PhD, of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and coauthors.

Of the questions – which concerned the accuracy of screening instruments; the harms of screening; the harms of interventions; and if screening or interventions improved decision making or outcomes for the patient, family/caregiver, or society – moderate evidence was found to support the accuracy of the instruments, treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for patients with moderate dementia, and psychoeducation interventions for caregivers of patients with moderate dementia. At the same time, there was moderate evidence of adverse effects from acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in patients with moderate dementia.

“I think, eventually, there will be sufficient evidence to justify screening, once we have what I call a tiered approach,” Marwan Sabbagh, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, said in an interview. “The very near future will include blood tests for Alzheimer’s, or PET scans, or genetics, or something else. Right now, the cognitive screens lack the specificity and sensitivity, and the secondary screening infrastructure that would improve the accuracy doesn’t exist yet.

“I think this is a ‘not now,’ ” he added, “but I wouldn’t say ‘not ever.’ ”

Dr. Patnode and coauthors noted specific limitations in the evidence, including a lack of studies on how screening for and treating cognitive impairment affects decision making. In addition, details like quality of life and institutionalization were inconsistently reported, and “consistent and standardized reporting of results according to meaningful thresholds of clinical significance” would have been valuable across all measures.

Clinical implications

The implications of this report’s conclusions are substantial, especially as the rising prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia becomes a worldwide concern, wrote Ronald C. Petersen, PhD, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and Kristine Yaffe, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial.

Though the data does not explicitly support screening, Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe noted that it still may have benefits. An estimated 10% of cognitive impairment is caused by at least somewhat reversible causes, and screening could also be used to improve care in medical problems that are worsened by cognitive impairment. To find the true value of these efforts, they wrote, researchers need to design and execute additional clinical trials that “answer many of the important questions surrounding screening and treatment of cognitive impairment.”

“The absence of evidence for benefit may lead to inaction,” they added, noting that clinicians screening should still consider the value of screening on a case-by-case basis in order to keep up with the impact of new disease-modifying therapies for certain neurodegenerative diseases.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in meetings. One member reported receiving grants and personal fees from Healthwise. The study was funded by the Department of Health & Human Services. One of the authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe reported consulting for, and receiving funding from, various pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and government organizations.

SOURCES: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0435; Patnode CD et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22258.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has deemed the current evidence “insufficient” to make a recommendation in regard to screening for cognitive impairment in adults aged 65 years or older.

“More research is needed on the effect of screening and early detection of cognitive impairment on important patient, caregiver, and societal outcomes, including decision making, advance planning, and caregiver outcomes,” wrote lead author Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and fellow members of the task force. The statement was published in JAMA.

To update a 2014 recommendation from the USPSTF, which also found insufficient evidence to properly assess cognitive screening’s benefits and harms, the task force commissioned a systematic review of studies applicable to community-dwelling older adults who are not exhibiting signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment. For their statement, “cognitive impairment” is defined as mild cognitive impairment and mild to moderate dementia.

Ultimately, they determined several factors that limited the overall evidence, including the short duration of most trials and the heterogenous nature of interventions and inconsistencies in outcomes reported. Any evidence that suggested improvements was mostly applicable to patients with moderate dementia, meaning “its applicability to a screen-detected population is uncertain.”

Updating 2014 recommendations

Their statement was based on an evidence report, also published in JAMA, in which a team of researchers reviewed 287 studies that included more than 285,000 older adults; 92 of the studies were newly identified, while the other 195 were carried forward from the 2014 recommendation’s review. The researchers sought the answers to five key questions, carrying over the framework from the previous review.

“Despite the accumulation of new data, the conclusions for these key questions are essentially unchanged from the prior review,” wrote lead author Carrie D. Patnode, PhD, of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and coauthors.

Of the questions – which concerned the accuracy of screening instruments; the harms of screening; the harms of interventions; and if screening or interventions improved decision making or outcomes for the patient, family/caregiver, or society – moderate evidence was found to support the accuracy of the instruments, treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for patients with moderate dementia, and psychoeducation interventions for caregivers of patients with moderate dementia. At the same time, there was moderate evidence of adverse effects from acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in patients with moderate dementia.

“I think, eventually, there will be sufficient evidence to justify screening, once we have what I call a tiered approach,” Marwan Sabbagh, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, said in an interview. “The very near future will include blood tests for Alzheimer’s, or PET scans, or genetics, or something else. Right now, the cognitive screens lack the specificity and sensitivity, and the secondary screening infrastructure that would improve the accuracy doesn’t exist yet.

“I think this is a ‘not now,’ ” he added, “but I wouldn’t say ‘not ever.’ ”

Dr. Patnode and coauthors noted specific limitations in the evidence, including a lack of studies on how screening for and treating cognitive impairment affects decision making. In addition, details like quality of life and institutionalization were inconsistently reported, and “consistent and standardized reporting of results according to meaningful thresholds of clinical significance” would have been valuable across all measures.

Clinical implications

The implications of this report’s conclusions are substantial, especially as the rising prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia becomes a worldwide concern, wrote Ronald C. Petersen, PhD, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and Kristine Yaffe, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial.

Though the data does not explicitly support screening, Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe noted that it still may have benefits. An estimated 10% of cognitive impairment is caused by at least somewhat reversible causes, and screening could also be used to improve care in medical problems that are worsened by cognitive impairment. To find the true value of these efforts, they wrote, researchers need to design and execute additional clinical trials that “answer many of the important questions surrounding screening and treatment of cognitive impairment.”

“The absence of evidence for benefit may lead to inaction,” they added, noting that clinicians screening should still consider the value of screening on a case-by-case basis in order to keep up with the impact of new disease-modifying therapies for certain neurodegenerative diseases.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in meetings. One member reported receiving grants and personal fees from Healthwise. The study was funded by the Department of Health & Human Services. One of the authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe reported consulting for, and receiving funding from, various pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and government organizations.

SOURCES: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0435; Patnode CD et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22258.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has deemed the current evidence “insufficient” to make a recommendation in regard to screening for cognitive impairment in adults aged 65 years or older.

“More research is needed on the effect of screening and early detection of cognitive impairment on important patient, caregiver, and societal outcomes, including decision making, advance planning, and caregiver outcomes,” wrote lead author Douglas K. Owens, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and fellow members of the task force. The statement was published in JAMA.

To update a 2014 recommendation from the USPSTF, which also found insufficient evidence to properly assess cognitive screening’s benefits and harms, the task force commissioned a systematic review of studies applicable to community-dwelling older adults who are not exhibiting signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment. For their statement, “cognitive impairment” is defined as mild cognitive impairment and mild to moderate dementia.

Ultimately, they determined several factors that limited the overall evidence, including the short duration of most trials and the heterogenous nature of interventions and inconsistencies in outcomes reported. Any evidence that suggested improvements was mostly applicable to patients with moderate dementia, meaning “its applicability to a screen-detected population is uncertain.”

Updating 2014 recommendations

Their statement was based on an evidence report, also published in JAMA, in which a team of researchers reviewed 287 studies that included more than 285,000 older adults; 92 of the studies were newly identified, while the other 195 were carried forward from the 2014 recommendation’s review. The researchers sought the answers to five key questions, carrying over the framework from the previous review.

“Despite the accumulation of new data, the conclusions for these key questions are essentially unchanged from the prior review,” wrote lead author Carrie D. Patnode, PhD, of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and coauthors.

Of the questions – which concerned the accuracy of screening instruments; the harms of screening; the harms of interventions; and if screening or interventions improved decision making or outcomes for the patient, family/caregiver, or society – moderate evidence was found to support the accuracy of the instruments, treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for patients with moderate dementia, and psychoeducation interventions for caregivers of patients with moderate dementia. At the same time, there was moderate evidence of adverse effects from acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in patients with moderate dementia.

“I think, eventually, there will be sufficient evidence to justify screening, once we have what I call a tiered approach,” Marwan Sabbagh, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, said in an interview. “The very near future will include blood tests for Alzheimer’s, or PET scans, or genetics, or something else. Right now, the cognitive screens lack the specificity and sensitivity, and the secondary screening infrastructure that would improve the accuracy doesn’t exist yet.

“I think this is a ‘not now,’ ” he added, “but I wouldn’t say ‘not ever.’ ”

Dr. Patnode and coauthors noted specific limitations in the evidence, including a lack of studies on how screening for and treating cognitive impairment affects decision making. In addition, details like quality of life and institutionalization were inconsistently reported, and “consistent and standardized reporting of results according to meaningful thresholds of clinical significance” would have been valuable across all measures.

Clinical implications

The implications of this report’s conclusions are substantial, especially as the rising prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia becomes a worldwide concern, wrote Ronald C. Petersen, PhD, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and Kristine Yaffe, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial.

Though the data does not explicitly support screening, Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe noted that it still may have benefits. An estimated 10% of cognitive impairment is caused by at least somewhat reversible causes, and screening could also be used to improve care in medical problems that are worsened by cognitive impairment. To find the true value of these efforts, they wrote, researchers need to design and execute additional clinical trials that “answer many of the important questions surrounding screening and treatment of cognitive impairment.”

“The absence of evidence for benefit may lead to inaction,” they added, noting that clinicians screening should still consider the value of screening on a case-by-case basis in order to keep up with the impact of new disease-modifying therapies for certain neurodegenerative diseases.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in meetings. One member reported receiving grants and personal fees from Healthwise. The study was funded by the Department of Health & Human Services. One of the authors reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Petersen and Dr. Yaffe reported consulting for, and receiving funding from, various pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and government organizations.

SOURCES: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0435; Patnode CD et al. JAMA. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22258.

FROM JAMA

As costs for neurologic drugs rise, adherence to therapy drops

For their study, published online Feb. 19 in Neurology, Brian C. Callaghan, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues looked at claims records from a large national private insurer to identify new cases of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and neuropathy between 2001 and 2016, along with pharmacy records following diagnoses.

The researchers identified more than 52,000 patients with neuropathy on gabapentinoids and another 5,000 treated with serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for the same. They also identified some 20,000 patients with dementia taking cholinesterase inhibitors, and 3,000 with Parkinson’s disease taking dopamine agonists. Dr. Callaghan and colleagues compared patient adherence over 6 months for pairs of drugs in the same class with similar or equal efficacy, but with different costs to the patient.

Such cost differences can be stark: The researchers noted that the average 2016 out-of-pocket cost for 30 days of pregabalin, a drug used in the treatment of peripheral neuropathy, was $65.70, compared with $8.40 for gabapentin. With two common dementia drugs the difference was even more pronounced: $79.30 for rivastigmine compared with $3.10 for donepezil, both cholinesterase inhibitors with similar efficacy and tolerability.

Dr. Callaghan and colleagues found that such cost differences bore significantly on patient adherence. An increase of $50 in patient costs was seen decreasing adherence by 9% for neuropathy patients on gabapentinoids (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.91, 0.89-0.93) and by 12% for dementia patients on cholinesterase inhibitors (adjusted IRR 0.88, 0.86-0.91, P less than .05 for both). Similar price-linked decreases were seen for neuropathy patients on SNRIs and Parkinson’s patients on dopamine agonists, but the differences did not reach statistical significance.