User login

Cirrhosis, Child-Pugh score predict ERCP complications

Cirrhosis may increase the risk of complications from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), according to a retrospective study involving almost 700 patients.

The study also showed that Child-Pugh class was a better predictor of risk than Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, reported lead author Michelle Bernshteyn, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at State University of New York, Syracuse , and colleagues.

“There remains a scarcity in the literature regarding complications and adverse effects after ERCP in cirrhotic patients, particularly those incorporating Child-Pugh class and MELD score or type of intervention as predictors,” Dr. Bernshteyn said during a virtual presentation at the American College of Gastroenterology annual meeting. “Furthermore, literature review demonstrates inconsistency among results.”

To gain clarity, Dr. Bernshteyn and colleagues reviewed electronic medical records from 692 patients who underwent ERCP, of whom 174 had cirrhosis and 518 did not. For all patients, the investigators analyzed demographics, comorbidities, indications for ERCP, type of sedation, type of intervention, and complications within a 30-day period. Complications included bleeding, pancreatitis, cholangitis, perforation, mortality caused by ERCP, and mortality from other causes. Patients with cirrhosis were further analyzed based on etiology of cirrhosis, Child-Pugh class, and MELD score.

The analysis revealed that complications were significantly more common in patients with cirrhosis than in those without cirrhosis (21.30% vs. 13.51%; P = .015). No specific complications were significantly more common in patients with cirrhosis than in those without cirrhosis.

In patients with cirrhosis, 41.18% of Child-Pugh class C patients had complications, compared with 15.15% of class B patients and 19.30% of class A patients (P = .010). In contrast, MELD scores were not significantly associated with adverse events.

Further analysis showed that, in patients without cirrhosis, diagnostic-only ERCP and underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were associated with high rates of complications (P = .039 and P = .003, respectively). In patients with cirrhosis, underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension predicted adverse events (P = .009 and P = .003, respectively).

“The results of our study reaffirm that liver cirrhosis has an impact on the occurrence of complications during ERCP,” Dr. Bernshteyn said. “Child-Pugh class seems to be more reliable as compared to MELD score in predicting complications of ERCP in cirrhosis patients,” she added. “However, we are also aware that Child-Pugh and MELD scores are complementary to each other while evaluating outcomes of any surgery in patients with cirrhosis.”

In 2017, Udayakumar Navaneethan, MD, a gastroenterologist at AdventHealth Orlando’s Center for Interventional Endoscopy, and an assistant professor at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, and colleagues published a national database study concerning the safety of ERCP in patients with liver cirrhosis.

“[The present] study is important as it highlights the fact that ERCP is associated with significant complications in cirrhotic patients compared to those without cirrhosis,” Dr. Navaneethan said when asked to comment. “Also, Child-Pugh score appeared to be more reliable than MELD score in predicting complications of ERCP in cirrhotic patients.”

He went on to explain relevance for practicing clinicians. “The clinical implications of the study are that a detailed risk-benefit discussion needs to be done with patients with liver cirrhosis, particularly with advanced liver disease Child-Pugh class C, irrespective of the etiology,” Dr. Navaneethan said. “ERCP should be performed when there is clear evidence that the benefits outweigh the risks.” The investigators and Dr. Navaneethan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bernshteyn M et al. ACG 2020, Abstract S0982.

Cirrhosis may increase the risk of complications from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), according to a retrospective study involving almost 700 patients.

The study also showed that Child-Pugh class was a better predictor of risk than Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, reported lead author Michelle Bernshteyn, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at State University of New York, Syracuse , and colleagues.

“There remains a scarcity in the literature regarding complications and adverse effects after ERCP in cirrhotic patients, particularly those incorporating Child-Pugh class and MELD score or type of intervention as predictors,” Dr. Bernshteyn said during a virtual presentation at the American College of Gastroenterology annual meeting. “Furthermore, literature review demonstrates inconsistency among results.”

To gain clarity, Dr. Bernshteyn and colleagues reviewed electronic medical records from 692 patients who underwent ERCP, of whom 174 had cirrhosis and 518 did not. For all patients, the investigators analyzed demographics, comorbidities, indications for ERCP, type of sedation, type of intervention, and complications within a 30-day period. Complications included bleeding, pancreatitis, cholangitis, perforation, mortality caused by ERCP, and mortality from other causes. Patients with cirrhosis were further analyzed based on etiology of cirrhosis, Child-Pugh class, and MELD score.

The analysis revealed that complications were significantly more common in patients with cirrhosis than in those without cirrhosis (21.30% vs. 13.51%; P = .015). No specific complications were significantly more common in patients with cirrhosis than in those without cirrhosis.

In patients with cirrhosis, 41.18% of Child-Pugh class C patients had complications, compared with 15.15% of class B patients and 19.30% of class A patients (P = .010). In contrast, MELD scores were not significantly associated with adverse events.

Further analysis showed that, in patients without cirrhosis, diagnostic-only ERCP and underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were associated with high rates of complications (P = .039 and P = .003, respectively). In patients with cirrhosis, underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension predicted adverse events (P = .009 and P = .003, respectively).

“The results of our study reaffirm that liver cirrhosis has an impact on the occurrence of complications during ERCP,” Dr. Bernshteyn said. “Child-Pugh class seems to be more reliable as compared to MELD score in predicting complications of ERCP in cirrhosis patients,” she added. “However, we are also aware that Child-Pugh and MELD scores are complementary to each other while evaluating outcomes of any surgery in patients with cirrhosis.”

In 2017, Udayakumar Navaneethan, MD, a gastroenterologist at AdventHealth Orlando’s Center for Interventional Endoscopy, and an assistant professor at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, and colleagues published a national database study concerning the safety of ERCP in patients with liver cirrhosis.

“[The present] study is important as it highlights the fact that ERCP is associated with significant complications in cirrhotic patients compared to those without cirrhosis,” Dr. Navaneethan said when asked to comment. “Also, Child-Pugh score appeared to be more reliable than MELD score in predicting complications of ERCP in cirrhotic patients.”

He went on to explain relevance for practicing clinicians. “The clinical implications of the study are that a detailed risk-benefit discussion needs to be done with patients with liver cirrhosis, particularly with advanced liver disease Child-Pugh class C, irrespective of the etiology,” Dr. Navaneethan said. “ERCP should be performed when there is clear evidence that the benefits outweigh the risks.” The investigators and Dr. Navaneethan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bernshteyn M et al. ACG 2020, Abstract S0982.

Cirrhosis may increase the risk of complications from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), according to a retrospective study involving almost 700 patients.

The study also showed that Child-Pugh class was a better predictor of risk than Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, reported lead author Michelle Bernshteyn, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at State University of New York, Syracuse , and colleagues.

“There remains a scarcity in the literature regarding complications and adverse effects after ERCP in cirrhotic patients, particularly those incorporating Child-Pugh class and MELD score or type of intervention as predictors,” Dr. Bernshteyn said during a virtual presentation at the American College of Gastroenterology annual meeting. “Furthermore, literature review demonstrates inconsistency among results.”

To gain clarity, Dr. Bernshteyn and colleagues reviewed electronic medical records from 692 patients who underwent ERCP, of whom 174 had cirrhosis and 518 did not. For all patients, the investigators analyzed demographics, comorbidities, indications for ERCP, type of sedation, type of intervention, and complications within a 30-day period. Complications included bleeding, pancreatitis, cholangitis, perforation, mortality caused by ERCP, and mortality from other causes. Patients with cirrhosis were further analyzed based on etiology of cirrhosis, Child-Pugh class, and MELD score.

The analysis revealed that complications were significantly more common in patients with cirrhosis than in those without cirrhosis (21.30% vs. 13.51%; P = .015). No specific complications were significantly more common in patients with cirrhosis than in those without cirrhosis.

In patients with cirrhosis, 41.18% of Child-Pugh class C patients had complications, compared with 15.15% of class B patients and 19.30% of class A patients (P = .010). In contrast, MELD scores were not significantly associated with adverse events.

Further analysis showed that, in patients without cirrhosis, diagnostic-only ERCP and underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were associated with high rates of complications (P = .039 and P = .003, respectively). In patients with cirrhosis, underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension predicted adverse events (P = .009 and P = .003, respectively).

“The results of our study reaffirm that liver cirrhosis has an impact on the occurrence of complications during ERCP,” Dr. Bernshteyn said. “Child-Pugh class seems to be more reliable as compared to MELD score in predicting complications of ERCP in cirrhosis patients,” she added. “However, we are also aware that Child-Pugh and MELD scores are complementary to each other while evaluating outcomes of any surgery in patients with cirrhosis.”

In 2017, Udayakumar Navaneethan, MD, a gastroenterologist at AdventHealth Orlando’s Center for Interventional Endoscopy, and an assistant professor at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, and colleagues published a national database study concerning the safety of ERCP in patients with liver cirrhosis.

“[The present] study is important as it highlights the fact that ERCP is associated with significant complications in cirrhotic patients compared to those without cirrhosis,” Dr. Navaneethan said when asked to comment. “Also, Child-Pugh score appeared to be more reliable than MELD score in predicting complications of ERCP in cirrhotic patients.”

He went on to explain relevance for practicing clinicians. “The clinical implications of the study are that a detailed risk-benefit discussion needs to be done with patients with liver cirrhosis, particularly with advanced liver disease Child-Pugh class C, irrespective of the etiology,” Dr. Navaneethan said. “ERCP should be performed when there is clear evidence that the benefits outweigh the risks.” The investigators and Dr. Navaneethan reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bernshteyn M et al. ACG 2020, Abstract S0982.

FROM ACG 2020

Antibiotics fail to improve colon ischemia outcomes

Antibiotics may not significantly improve clinical outcomes in patients with colon ischemia (CI), regardless of severity level, based on a retrospective study involving more than 800 patients.

Given these findings, clinicians “should consider not giving antibiotics to patients with CI,” reported lead author Paul Feuerstadt, MD, of Yale University, New Haven , Conn., and colleagues.

“CI is the most common ischemic injury to the GI tract,” the investigators wrote in their abstract, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “The clinical utility of antibiotic treatment in CI is unclear and the literature is limited.”

Dr. Feuerstadt and colleagues analyzed data from 838 patients with biopsy-proven CI who were hospitalized between 2005 and 2017, of whom 413 and 425 had moderate and severe disease, respectively.

Across all patients, 67.7% received antibiotics. While there were no significant intergroup differences in age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, or sex, patients who received antibiotics were more likely to have severe CI (54.4% vs. 42.2%; P = .001), small-bowel involvement (12.0% vs. 5.7%; P = .04), and peritonitis (11.3% vs. 4.5%; P = 002), as well as require intensive care (26.1% vs. 19.9%; P = .04).

After adjusting for severity of CI, small-bowel involvement, and comorbidities, analysis revealed no significant associations between antibiotic use and 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, 30-day colectomy, 90-day recurrence, 90-day readmission, or length of stay. The primary outcome, 30-day mortality, remained insignificant in subgroup analyses based on CI severity and age.

Patients were most frequently prescribed ciprofloxacin-metronidazole (57.1%), followed by piperacillin-tazobactam (13.2%), ceftriaxone-metronidazole (11.1%), and other antibiotics (18.5%).

When each of these antimicrobials was compared with no antibiotic usage, only piperacillin-tazobactam correlated with a higher rate of 30-day mortality, based on an adjusted odds ratio of 3.4 (95% CI, 1.5-8.0; P = .0003). But most patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam underwent colectomy, which prompted independent analyses of patients who underwent colectomy and those who did not undergo colectomy. These findings showed no difference in 30-day mortality based on the type of antibiotic used.

During an oral presentation at the meeting, coauthor Karthik Gnanapandithan, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla, said, “In practice, it is reasonable to still use antibiotics in patients with small bowel ischemia and those with severe CI with a high risk of poor outcomes pending prospective studies.”

According to John F. Valentine, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, the present study “adds to the literature that questions the role of antibiotics in CI.”

Dr. Valentine noted that, even among patients with CI who have severe inflammation, “sepsis rarely occurs without frank perforation.”

Still, like Dr. Gnanapandithan, Dr. Valentine concluded that antibiotics are still a reasonable treatment option for certain patients with CI.

“The risks and potential benefits of antibiotics must be considered,” he said. “Until prospective studies are available, use of antibiotics in colon ischemia is reasonable in the setting of severe disease with peritoneal signs, signs of sepsis, pneumatosis, or portal venous gas.”

Dr. Feuerstadt disclosed relationships with Ferring/Rebiotix, Merck, and Roche. Dr. Valentine reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Antibiotics may not significantly improve clinical outcomes in patients with colon ischemia (CI), regardless of severity level, based on a retrospective study involving more than 800 patients.

Given these findings, clinicians “should consider not giving antibiotics to patients with CI,” reported lead author Paul Feuerstadt, MD, of Yale University, New Haven , Conn., and colleagues.

“CI is the most common ischemic injury to the GI tract,” the investigators wrote in their abstract, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “The clinical utility of antibiotic treatment in CI is unclear and the literature is limited.”

Dr. Feuerstadt and colleagues analyzed data from 838 patients with biopsy-proven CI who were hospitalized between 2005 and 2017, of whom 413 and 425 had moderate and severe disease, respectively.

Across all patients, 67.7% received antibiotics. While there were no significant intergroup differences in age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, or sex, patients who received antibiotics were more likely to have severe CI (54.4% vs. 42.2%; P = .001), small-bowel involvement (12.0% vs. 5.7%; P = .04), and peritonitis (11.3% vs. 4.5%; P = 002), as well as require intensive care (26.1% vs. 19.9%; P = .04).

After adjusting for severity of CI, small-bowel involvement, and comorbidities, analysis revealed no significant associations between antibiotic use and 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, 30-day colectomy, 90-day recurrence, 90-day readmission, or length of stay. The primary outcome, 30-day mortality, remained insignificant in subgroup analyses based on CI severity and age.

Patients were most frequently prescribed ciprofloxacin-metronidazole (57.1%), followed by piperacillin-tazobactam (13.2%), ceftriaxone-metronidazole (11.1%), and other antibiotics (18.5%).

When each of these antimicrobials was compared with no antibiotic usage, only piperacillin-tazobactam correlated with a higher rate of 30-day mortality, based on an adjusted odds ratio of 3.4 (95% CI, 1.5-8.0; P = .0003). But most patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam underwent colectomy, which prompted independent analyses of patients who underwent colectomy and those who did not undergo colectomy. These findings showed no difference in 30-day mortality based on the type of antibiotic used.

During an oral presentation at the meeting, coauthor Karthik Gnanapandithan, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla, said, “In practice, it is reasonable to still use antibiotics in patients with small bowel ischemia and those with severe CI with a high risk of poor outcomes pending prospective studies.”

According to John F. Valentine, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, the present study “adds to the literature that questions the role of antibiotics in CI.”

Dr. Valentine noted that, even among patients with CI who have severe inflammation, “sepsis rarely occurs without frank perforation.”

Still, like Dr. Gnanapandithan, Dr. Valentine concluded that antibiotics are still a reasonable treatment option for certain patients with CI.

“The risks and potential benefits of antibiotics must be considered,” he said. “Until prospective studies are available, use of antibiotics in colon ischemia is reasonable in the setting of severe disease with peritoneal signs, signs of sepsis, pneumatosis, or portal venous gas.”

Dr. Feuerstadt disclosed relationships with Ferring/Rebiotix, Merck, and Roche. Dr. Valentine reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Antibiotics may not significantly improve clinical outcomes in patients with colon ischemia (CI), regardless of severity level, based on a retrospective study involving more than 800 patients.

Given these findings, clinicians “should consider not giving antibiotics to patients with CI,” reported lead author Paul Feuerstadt, MD, of Yale University, New Haven , Conn., and colleagues.

“CI is the most common ischemic injury to the GI tract,” the investigators wrote in their abstract, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “The clinical utility of antibiotic treatment in CI is unclear and the literature is limited.”

Dr. Feuerstadt and colleagues analyzed data from 838 patients with biopsy-proven CI who were hospitalized between 2005 and 2017, of whom 413 and 425 had moderate and severe disease, respectively.

Across all patients, 67.7% received antibiotics. While there were no significant intergroup differences in age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, or sex, patients who received antibiotics were more likely to have severe CI (54.4% vs. 42.2%; P = .001), small-bowel involvement (12.0% vs. 5.7%; P = .04), and peritonitis (11.3% vs. 4.5%; P = 002), as well as require intensive care (26.1% vs. 19.9%; P = .04).

After adjusting for severity of CI, small-bowel involvement, and comorbidities, analysis revealed no significant associations between antibiotic use and 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, 30-day colectomy, 90-day recurrence, 90-day readmission, or length of stay. The primary outcome, 30-day mortality, remained insignificant in subgroup analyses based on CI severity and age.

Patients were most frequently prescribed ciprofloxacin-metronidazole (57.1%), followed by piperacillin-tazobactam (13.2%), ceftriaxone-metronidazole (11.1%), and other antibiotics (18.5%).

When each of these antimicrobials was compared with no antibiotic usage, only piperacillin-tazobactam correlated with a higher rate of 30-day mortality, based on an adjusted odds ratio of 3.4 (95% CI, 1.5-8.0; P = .0003). But most patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam underwent colectomy, which prompted independent analyses of patients who underwent colectomy and those who did not undergo colectomy. These findings showed no difference in 30-day mortality based on the type of antibiotic used.

During an oral presentation at the meeting, coauthor Karthik Gnanapandithan, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla, said, “In practice, it is reasonable to still use antibiotics in patients with small bowel ischemia and those with severe CI with a high risk of poor outcomes pending prospective studies.”

According to John F. Valentine, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, the present study “adds to the literature that questions the role of antibiotics in CI.”

Dr. Valentine noted that, even among patients with CI who have severe inflammation, “sepsis rarely occurs without frank perforation.”

Still, like Dr. Gnanapandithan, Dr. Valentine concluded that antibiotics are still a reasonable treatment option for certain patients with CI.

“The risks and potential benefits of antibiotics must be considered,” he said. “Until prospective studies are available, use of antibiotics in colon ischemia is reasonable in the setting of severe disease with peritoneal signs, signs of sepsis, pneumatosis, or portal venous gas.”

Dr. Feuerstadt disclosed relationships with Ferring/Rebiotix, Merck, and Roche. Dr. Valentine reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM ACG 2020

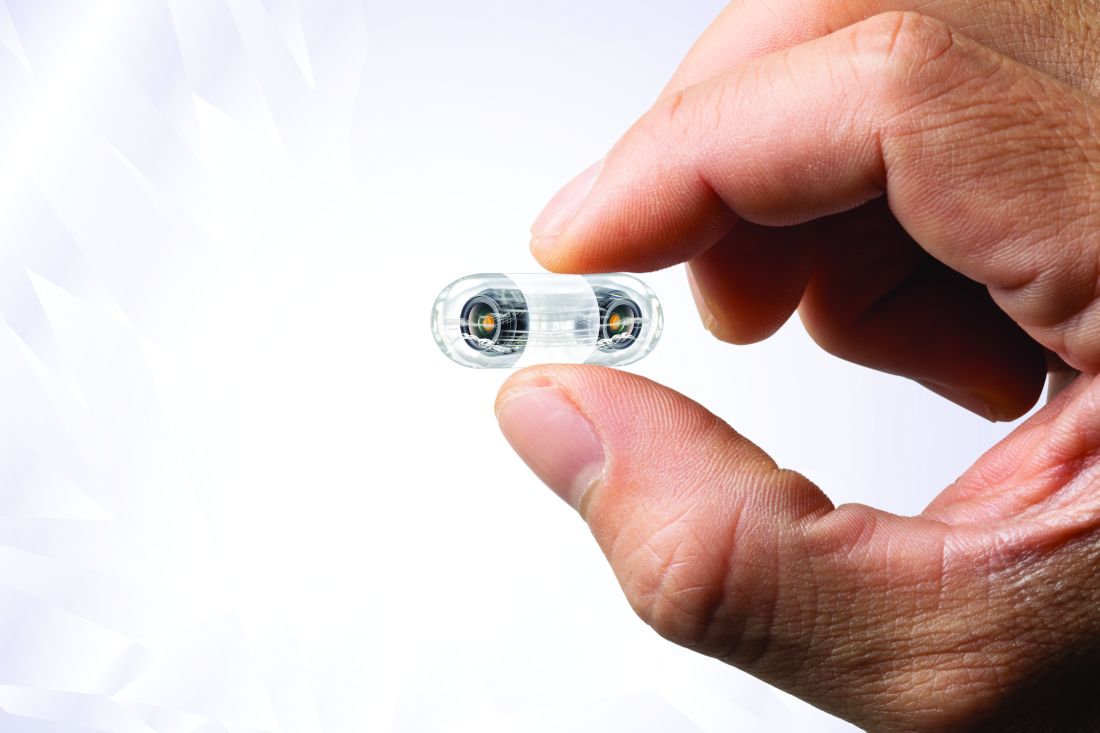

Video capsule endoscopy shows superiority, may reduce coronavirus exposure

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) offers an alternative triage tool for acute GI bleeding that may reduce personnel exposure to SARS-CoV-2, based on a cohort study with historical controls.

VCE should be considered even when rapid coronavirus testing is available, as active bleeding is more likely to be detected when evaluated sooner, potentially sparing patients from invasive procedures, reported lead author Shahrad Hakimian, MD, of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worchester, and colleagues.

“Endoscopists and staff are at high risk of exposure to coronavirus through aerosols, as well as unintended, unrecognized splashes that are well known to occur frequently during routine endoscopy,” Dr. Hakimian said during a virtual presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Although pretesting and delaying procedures as needed may mitigate risks of viral exposure, “many urgent procedures, such as endoscopic evaluation of gastrointestinal bleeding, can’t really wait,” Dr. Hakimian said.

Current guidelines recommend early upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy for evaluation of GI bleeding, but Dr. Hakimian noted that two out of three initial tests are nondiagnostic, so multiple procedures are often needed to find an answer.

In 2018, a randomized, controlled trial coauthored by Dr. Hakimian’s colleagues demonstrated how VCE may be a better approach, as it more frequently detected active bleeding than standard of care (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.36-5.64).

The present study built on these findings in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Hakimian and colleagues analyzed data from 50 consecutive, hemodynamically stable patients with severe anemia or suspected GI bleeding who underwent VCE as a first-line diagnostic modality from mid-March to mid-May 2020 (COVID arm). These patients were compared with 57 consecutive patients who were evaluated for acute GI bleeding or severe anemia with standard of care prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (pre-COVID arm).

Characteristics of the two cohorts were generally similar, although the COVID arm included a slightly older population, with a median age of 68 years, compared with a median age of 61.8 years for the pre-COVID arm (P = .03). Among presenting symptoms, hematochezia was less common in the COVID group (4% vs. 18%; P = .03). Comorbidities were not significantly different between cohorts.

Per the study design, 100% of patients in the COVID arm underwent VCE as their first diagnostic modality. In the pre-COVID arm, 82% of patients first underwent upper endoscopy, followed by colonoscopy (12%) and VCE (5%).

The main outcome, bleeding localization, did not differ between groups, whether this was confined to the first test, or in terms of final localization. But VCE was significantly better at detecting active bleeding or stigmata of bleeding, at a rate of 66%, compared with 28% in the pre-COVID group (P < .001). Patients in the COVID arm were also significantly less likely to need any invasive procedures (44% vs. 96%; P < .001).

No intergroup differences were observed in rates of blood transfusion, in-hospital or GI-bleed mortality, rebleeding, or readmission for bleeding.

“VCE appears to be a safe alternative to traditional diagnostic evaluation of GI bleeding in the era of COVID,” Dr. Hakimian concluded, noting that “the VCE-first strategy reduces the risk of staff exposure to endoscopic aerosols, conserves personal protective equipment, and reduces staff utilization.”

According to Neil Sengupta, MD, of the University of Chicago, “a VCE-first strategy in GI bleeding may be a useful triage tool in the COVID-19 era to determine which patients truly benefit from invasive endoscopy,” although he also noted that “further data are needed to determine the efficacy and safety of this approach.”

Lawrence Hookey, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., had a similar opinion.

“VCE appears to be a reasonable alternative in this patient group, at least as a first step,” Dr. Hookey said. “However, whether it truly makes a difference in the decision making process would have to be assessed prospectively via a randomized controlled trial or a decision analysis done in real time at various steps of the patient’s care path.”

Erik A. Holzwanger, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, suggested that these findings may “serve as a foundation” for similar studies, “as it appears COVID-19 will be an ongoing obstacle in endoscopy for the foreseeable future.”

“It would be interesting to have further discussion of timing of VCE, any COVID-19 transmission to staff during the VCE placement, and discussion of what constituted proceeding with endoscopic intervention [high-risk lesion, active bleeding] in both groups,” he added.

David Cave, MD, PhD, coauthor of the present study and the 2015 ACG clinical guideline for small bowel bleeding, said that VCE is gaining ground as the diagnostic of choice for GI bleeding, and patients prefer it, since it does not require anesthesia.

“This abstract is another clear pointer to the way in which, we should in the future, investigate gastrointestinal bleeding, both acute and chronic,” Dr. Cave said. “We are at an inflection point of transition to a new technology.”

Dr. Cave disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Olympus. The other investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) offers an alternative triage tool for acute GI bleeding that may reduce personnel exposure to SARS-CoV-2, based on a cohort study with historical controls.

VCE should be considered even when rapid coronavirus testing is available, as active bleeding is more likely to be detected when evaluated sooner, potentially sparing patients from invasive procedures, reported lead author Shahrad Hakimian, MD, of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worchester, and colleagues.

“Endoscopists and staff are at high risk of exposure to coronavirus through aerosols, as well as unintended, unrecognized splashes that are well known to occur frequently during routine endoscopy,” Dr. Hakimian said during a virtual presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Although pretesting and delaying procedures as needed may mitigate risks of viral exposure, “many urgent procedures, such as endoscopic evaluation of gastrointestinal bleeding, can’t really wait,” Dr. Hakimian said.

Current guidelines recommend early upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy for evaluation of GI bleeding, but Dr. Hakimian noted that two out of three initial tests are nondiagnostic, so multiple procedures are often needed to find an answer.

In 2018, a randomized, controlled trial coauthored by Dr. Hakimian’s colleagues demonstrated how VCE may be a better approach, as it more frequently detected active bleeding than standard of care (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.36-5.64).

The present study built on these findings in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Hakimian and colleagues analyzed data from 50 consecutive, hemodynamically stable patients with severe anemia or suspected GI bleeding who underwent VCE as a first-line diagnostic modality from mid-March to mid-May 2020 (COVID arm). These patients were compared with 57 consecutive patients who were evaluated for acute GI bleeding or severe anemia with standard of care prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (pre-COVID arm).

Characteristics of the two cohorts were generally similar, although the COVID arm included a slightly older population, with a median age of 68 years, compared with a median age of 61.8 years for the pre-COVID arm (P = .03). Among presenting symptoms, hematochezia was less common in the COVID group (4% vs. 18%; P = .03). Comorbidities were not significantly different between cohorts.

Per the study design, 100% of patients in the COVID arm underwent VCE as their first diagnostic modality. In the pre-COVID arm, 82% of patients first underwent upper endoscopy, followed by colonoscopy (12%) and VCE (5%).

The main outcome, bleeding localization, did not differ between groups, whether this was confined to the first test, or in terms of final localization. But VCE was significantly better at detecting active bleeding or stigmata of bleeding, at a rate of 66%, compared with 28% in the pre-COVID group (P < .001). Patients in the COVID arm were also significantly less likely to need any invasive procedures (44% vs. 96%; P < .001).

No intergroup differences were observed in rates of blood transfusion, in-hospital or GI-bleed mortality, rebleeding, or readmission for bleeding.

“VCE appears to be a safe alternative to traditional diagnostic evaluation of GI bleeding in the era of COVID,” Dr. Hakimian concluded, noting that “the VCE-first strategy reduces the risk of staff exposure to endoscopic aerosols, conserves personal protective equipment, and reduces staff utilization.”

According to Neil Sengupta, MD, of the University of Chicago, “a VCE-first strategy in GI bleeding may be a useful triage tool in the COVID-19 era to determine which patients truly benefit from invasive endoscopy,” although he also noted that “further data are needed to determine the efficacy and safety of this approach.”

Lawrence Hookey, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., had a similar opinion.

“VCE appears to be a reasonable alternative in this patient group, at least as a first step,” Dr. Hookey said. “However, whether it truly makes a difference in the decision making process would have to be assessed prospectively via a randomized controlled trial or a decision analysis done in real time at various steps of the patient’s care path.”

Erik A. Holzwanger, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, suggested that these findings may “serve as a foundation” for similar studies, “as it appears COVID-19 will be an ongoing obstacle in endoscopy for the foreseeable future.”

“It would be interesting to have further discussion of timing of VCE, any COVID-19 transmission to staff during the VCE placement, and discussion of what constituted proceeding with endoscopic intervention [high-risk lesion, active bleeding] in both groups,” he added.

David Cave, MD, PhD, coauthor of the present study and the 2015 ACG clinical guideline for small bowel bleeding, said that VCE is gaining ground as the diagnostic of choice for GI bleeding, and patients prefer it, since it does not require anesthesia.

“This abstract is another clear pointer to the way in which, we should in the future, investigate gastrointestinal bleeding, both acute and chronic,” Dr. Cave said. “We are at an inflection point of transition to a new technology.”

Dr. Cave disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Olympus. The other investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) offers an alternative triage tool for acute GI bleeding that may reduce personnel exposure to SARS-CoV-2, based on a cohort study with historical controls.

VCE should be considered even when rapid coronavirus testing is available, as active bleeding is more likely to be detected when evaluated sooner, potentially sparing patients from invasive procedures, reported lead author Shahrad Hakimian, MD, of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worchester, and colleagues.

“Endoscopists and staff are at high risk of exposure to coronavirus through aerosols, as well as unintended, unrecognized splashes that are well known to occur frequently during routine endoscopy,” Dr. Hakimian said during a virtual presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Although pretesting and delaying procedures as needed may mitigate risks of viral exposure, “many urgent procedures, such as endoscopic evaluation of gastrointestinal bleeding, can’t really wait,” Dr. Hakimian said.

Current guidelines recommend early upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy for evaluation of GI bleeding, but Dr. Hakimian noted that two out of three initial tests are nondiagnostic, so multiple procedures are often needed to find an answer.

In 2018, a randomized, controlled trial coauthored by Dr. Hakimian’s colleagues demonstrated how VCE may be a better approach, as it more frequently detected active bleeding than standard of care (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.36-5.64).

The present study built on these findings in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Hakimian and colleagues analyzed data from 50 consecutive, hemodynamically stable patients with severe anemia or suspected GI bleeding who underwent VCE as a first-line diagnostic modality from mid-March to mid-May 2020 (COVID arm). These patients were compared with 57 consecutive patients who were evaluated for acute GI bleeding or severe anemia with standard of care prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (pre-COVID arm).

Characteristics of the two cohorts were generally similar, although the COVID arm included a slightly older population, with a median age of 68 years, compared with a median age of 61.8 years for the pre-COVID arm (P = .03). Among presenting symptoms, hematochezia was less common in the COVID group (4% vs. 18%; P = .03). Comorbidities were not significantly different between cohorts.

Per the study design, 100% of patients in the COVID arm underwent VCE as their first diagnostic modality. In the pre-COVID arm, 82% of patients first underwent upper endoscopy, followed by colonoscopy (12%) and VCE (5%).

The main outcome, bleeding localization, did not differ between groups, whether this was confined to the first test, or in terms of final localization. But VCE was significantly better at detecting active bleeding or stigmata of bleeding, at a rate of 66%, compared with 28% in the pre-COVID group (P < .001). Patients in the COVID arm were also significantly less likely to need any invasive procedures (44% vs. 96%; P < .001).

No intergroup differences were observed in rates of blood transfusion, in-hospital or GI-bleed mortality, rebleeding, or readmission for bleeding.

“VCE appears to be a safe alternative to traditional diagnostic evaluation of GI bleeding in the era of COVID,” Dr. Hakimian concluded, noting that “the VCE-first strategy reduces the risk of staff exposure to endoscopic aerosols, conserves personal protective equipment, and reduces staff utilization.”

According to Neil Sengupta, MD, of the University of Chicago, “a VCE-first strategy in GI bleeding may be a useful triage tool in the COVID-19 era to determine which patients truly benefit from invasive endoscopy,” although he also noted that “further data are needed to determine the efficacy and safety of this approach.”

Lawrence Hookey, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., had a similar opinion.

“VCE appears to be a reasonable alternative in this patient group, at least as a first step,” Dr. Hookey said. “However, whether it truly makes a difference in the decision making process would have to be assessed prospectively via a randomized controlled trial or a decision analysis done in real time at various steps of the patient’s care path.”

Erik A. Holzwanger, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, suggested that these findings may “serve as a foundation” for similar studies, “as it appears COVID-19 will be an ongoing obstacle in endoscopy for the foreseeable future.”

“It would be interesting to have further discussion of timing of VCE, any COVID-19 transmission to staff during the VCE placement, and discussion of what constituted proceeding with endoscopic intervention [high-risk lesion, active bleeding] in both groups,” he added.

David Cave, MD, PhD, coauthor of the present study and the 2015 ACG clinical guideline for small bowel bleeding, said that VCE is gaining ground as the diagnostic of choice for GI bleeding, and patients prefer it, since it does not require anesthesia.

“This abstract is another clear pointer to the way in which, we should in the future, investigate gastrointestinal bleeding, both acute and chronic,” Dr. Cave said. “We are at an inflection point of transition to a new technology.”

Dr. Cave disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Olympus. The other investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM ACG 2020

Statins may lower risk of colorectal cancer

Statin use may significantly lower the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), based on a meta-analysis and systematic review.

In more than 15,000 patients with IBD, statin use was associated with a 60% reduced risk of CRC, reported lead author Kevin N. Singh, MD, of NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, and colleagues.

“Statin use has been linked with a risk reduction for cancers including hepatocellular carcinoma, breast, gastric, pancreatic, and biliary tract cancers, but data supporting the use of statins for chemoprevention against CRC is conflicting,” Dr. Singh said during a virtual presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

He noted a 2014 meta-analysis by Lytras and colleagues that reported a 9% CRC risk reduction in statin users who did not have IBD. In patients with IBD, data are scarce, according to Dr. Singh.

To further explore the relationship between statin use and CRC in patients without IBD, the investigators analyzed data from 52 studies, including 8 randomized clinical trials, 17 cohort studies, and 27 case-control studies. Of the 11,459,306 patients involved, approximately 2 million used statins and roughly 9 million did not.

To evaluate the same relationship in patients with IBD, the investigators conducted a separate meta-analysis involving 15,342 patients from 5 observational studies, 1 of which was an unpublished abstract. In the 4 published studies, 1,161 patients used statins while 12,145 did not.

In the non-IBD population, statin use was associated with a 20% reduced risk of CRC (pooled odds ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.88; P less than .001). In patients with IBD, statin use was associated with a 60% CRC risk reduction (pooled OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.19-0.86, P = .019).

Dr. Singh noted “significant heterogeneity” in both analyses (I2 greater than 75), most prominently in the IBD populations, which he ascribed to “differences in demographic features, ethnic groups, and risk factors for CRC.”

While publication bias was absent from the non-IBD analysis, it was detected in the IBD portion of the study. Dr. Singh said that selection bias may also have been present in the IBD analysis, due to exclusive use of observational studies.

“Prospective trials are needed to confirm the risk reduction of CRC in the IBD population, including whether the effects of statins differ between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients,” Dr. Singh said.

Additional analyses are underway, he added, including one that will account for the potentially confounding effect of aspirin use.

According to David E. Kaplan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, “The finding that statins are associated with reduced CRC in IBD provides additional support for the clinical importance of the antineoplastic effects of statins. This effect has been strongly observed in liver cancer, and is pending prospective validation.”

Dr. Kaplan also offered some mechanistic insight into why statins have an anticancer effect, pointing to “the centrality of cholesterol biosynthesis for development and/or progression of malignancy.”

The investigators and Dr. Kaplan reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Statin use may significantly lower the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), based on a meta-analysis and systematic review.

In more than 15,000 patients with IBD, statin use was associated with a 60% reduced risk of CRC, reported lead author Kevin N. Singh, MD, of NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, and colleagues.

“Statin use has been linked with a risk reduction for cancers including hepatocellular carcinoma, breast, gastric, pancreatic, and biliary tract cancers, but data supporting the use of statins for chemoprevention against CRC is conflicting,” Dr. Singh said during a virtual presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

He noted a 2014 meta-analysis by Lytras and colleagues that reported a 9% CRC risk reduction in statin users who did not have IBD. In patients with IBD, data are scarce, according to Dr. Singh.

To further explore the relationship between statin use and CRC in patients without IBD, the investigators analyzed data from 52 studies, including 8 randomized clinical trials, 17 cohort studies, and 27 case-control studies. Of the 11,459,306 patients involved, approximately 2 million used statins and roughly 9 million did not.

To evaluate the same relationship in patients with IBD, the investigators conducted a separate meta-analysis involving 15,342 patients from 5 observational studies, 1 of which was an unpublished abstract. In the 4 published studies, 1,161 patients used statins while 12,145 did not.

In the non-IBD population, statin use was associated with a 20% reduced risk of CRC (pooled odds ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.88; P less than .001). In patients with IBD, statin use was associated with a 60% CRC risk reduction (pooled OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.19-0.86, P = .019).

Dr. Singh noted “significant heterogeneity” in both analyses (I2 greater than 75), most prominently in the IBD populations, which he ascribed to “differences in demographic features, ethnic groups, and risk factors for CRC.”

While publication bias was absent from the non-IBD analysis, it was detected in the IBD portion of the study. Dr. Singh said that selection bias may also have been present in the IBD analysis, due to exclusive use of observational studies.

“Prospective trials are needed to confirm the risk reduction of CRC in the IBD population, including whether the effects of statins differ between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients,” Dr. Singh said.

Additional analyses are underway, he added, including one that will account for the potentially confounding effect of aspirin use.

According to David E. Kaplan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, “The finding that statins are associated with reduced CRC in IBD provides additional support for the clinical importance of the antineoplastic effects of statins. This effect has been strongly observed in liver cancer, and is pending prospective validation.”

Dr. Kaplan also offered some mechanistic insight into why statins have an anticancer effect, pointing to “the centrality of cholesterol biosynthesis for development and/or progression of malignancy.”

The investigators and Dr. Kaplan reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Statin use may significantly lower the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), based on a meta-analysis and systematic review.

In more than 15,000 patients with IBD, statin use was associated with a 60% reduced risk of CRC, reported lead author Kevin N. Singh, MD, of NYU Langone Medical Center in New York, and colleagues.

“Statin use has been linked with a risk reduction for cancers including hepatocellular carcinoma, breast, gastric, pancreatic, and biliary tract cancers, but data supporting the use of statins for chemoprevention against CRC is conflicting,” Dr. Singh said during a virtual presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

He noted a 2014 meta-analysis by Lytras and colleagues that reported a 9% CRC risk reduction in statin users who did not have IBD. In patients with IBD, data are scarce, according to Dr. Singh.

To further explore the relationship between statin use and CRC in patients without IBD, the investigators analyzed data from 52 studies, including 8 randomized clinical trials, 17 cohort studies, and 27 case-control studies. Of the 11,459,306 patients involved, approximately 2 million used statins and roughly 9 million did not.

To evaluate the same relationship in patients with IBD, the investigators conducted a separate meta-analysis involving 15,342 patients from 5 observational studies, 1 of which was an unpublished abstract. In the 4 published studies, 1,161 patients used statins while 12,145 did not.

In the non-IBD population, statin use was associated with a 20% reduced risk of CRC (pooled odds ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.88; P less than .001). In patients with IBD, statin use was associated with a 60% CRC risk reduction (pooled OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.19-0.86, P = .019).

Dr. Singh noted “significant heterogeneity” in both analyses (I2 greater than 75), most prominently in the IBD populations, which he ascribed to “differences in demographic features, ethnic groups, and risk factors for CRC.”

While publication bias was absent from the non-IBD analysis, it was detected in the IBD portion of the study. Dr. Singh said that selection bias may also have been present in the IBD analysis, due to exclusive use of observational studies.

“Prospective trials are needed to confirm the risk reduction of CRC in the IBD population, including whether the effects of statins differ between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients,” Dr. Singh said.

Additional analyses are underway, he added, including one that will account for the potentially confounding effect of aspirin use.

According to David E. Kaplan, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, “The finding that statins are associated with reduced CRC in IBD provides additional support for the clinical importance of the antineoplastic effects of statins. This effect has been strongly observed in liver cancer, and is pending prospective validation.”

Dr. Kaplan also offered some mechanistic insight into why statins have an anticancer effect, pointing to “the centrality of cholesterol biosynthesis for development and/or progression of malignancy.”

The investigators and Dr. Kaplan reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM ACG 2020

AHA adds recovery, emotional support to CPR guidelines

Highlights of new updated guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care from the American Heart Association include management of opioid-related emergencies; discussion of health disparities; and a new emphasis on physical, social, and emotional recovery after resuscitation.

The AHA is also exploring digital territory to improve CPR outcomes. The guidelines encourage use of mobile phone technology to summon trained laypeople to individuals requiring CPR, and an adaptive learning suite will be available online for personalized CPR instruction, with lessons catered to individual needs and knowledge levels.

These novel approaches reflect an ongoing effort by the AHA to ensure that the guidelines evolve rapidly with science and technology, reported Raina Merchant, MD, chair of the AHA Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues. In 2015, the committee shifted from 5-year updates to a continuous online review process, citing a need for more immediate implementation of practice-altering data, they wrote in Circulation.

And new approaches do appear to save lives, at least in a hospital setting.

Since 2004, in-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes have been improving, but similar gains have yet to be realized for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

“Much of the variation in survival rates is thought to be due to the strength of the Chain of Survival, the [five] critical actions that must occur in rapid succession to maximize the chance of survival from cardiac arrest,” the committee wrote.

Update adds sixth link to Chains of Survival: Recovery

“Recovery expectations and survivorship plans that address treatment, surveillance, and rehabilitation need to be provided to cardiac arrest survivors and their caregivers at hospital discharge to address the sequelae of cardiac arrest and optimize transitions of care to independent physical, social, emotional, and role function,” the committee wrote.

Dr. Merchant and colleagues identified three “critically important” recommendations for both cardiac arrest survivors and caregivers during the recovery process: structured psychological assessment; multimodal rehabilitation assessment and treatment; and comprehensive, multidisciplinary discharge planning.

The recovery process is now part of all four Chains of Survival, which are specific to in-hospital and out-of-hospital arrest for adults and children.

New advice on opioid overdoses and bystander training

Among instances of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, the committee noted that opioid overdoses are “sharply on the rise,” leading to new, scenario-specific recommendations. Among them, the committee encouraged lay rescuers and trained responders to activate emergency response systems immediately while awaiting improvements with naloxone and other interventions. They also suggested that, for individuals in known or suspected cardiac arrest, high-quality CPR, including compressions and ventilation, should be prioritized over naloxone administration.

In a broader discussion, the committee identified disparities in CPR training, which could explain lower rates of bystander CPR and poorer outcomes among certain demographics, such as black and Hispanic populations, as well as those with lower socioeconomic status.

“Targeting training efforts should consider barriers such as language, financial considerations, and poor access to information,” the committee wrote.

While low bystander CPR in these areas may be improved through mobile phone technology that alerts trained laypeople to individuals in need, the committee noted that this approach may be impacted by cultural and geographic factors. To date, use of mobile devices to improve bystander intervention rates has been demonstrated through “uniformly positive data,” but never in North America.

According to the guidelines, bystander intervention rates may also be improved through video-based learning, which is as effective as in-person, instructor-led training.

This led the AHA to create an online adaptive learning platform, which the organization describes as a “digital resuscitation portfolio” that connects programs and courses such as the Resuscitation Quality Improvement program and the HeartCode blended learning course.

“It will cover all of the guideline changes,” said Monica Sales, communications manager at the AHA. “It’s really groundbreaking because it’s the first time that we’re able to kind of close that gap between new science and new products.”

The online content also addresses CPR considerations for COVID-19, which were first addressed by interim CPR guidance published by the AHA in April.

According to Alexis Topjian, MD, coauthor of the present guidelines and pediatric critical care medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, CPR awareness is more important now than ever.

“The major message [of the guidelines] is that high-quality CPR saves lives,” she said. “So push hard, and push fast. You have the power in your hands to make a difference, more so than ever during this pandemic.”

Concerning coronavirus precautions, Dr. Topjian noted that roughly 70% of out-of-hospital CPR events involve people who know each other, so most bystanders have already been exposed to the person in need, thereby reducing the concern of infection.

When asked about performing CPR on strangers, Dr. Topjian remained encouraging, though she noted that decision making may be informed by local coronavirus rates.

“It’s always a personal choice,” she said.

More for clinicians

For clinicians, Dr. Topjian highlighted several recommendations, including use of epinephrine as soon as possible during CPR, preferential use of a cuffed endotracheal tube, continuous EEG monitoring during and after cardiac arrest, and rapid intervention for clinical seizures and of nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

From a pediatric perspective, Dr. Topjian pointed out a change in breathing rate for infants and children who are receiving CPR or rescue breathing with a pulse, from 12-20 breaths/min to 20-30 breaths/min. While not a new recommendation, Dr. Topjian also pointed out the lifesaving benefit of early defibrillation among pediatric patients.

The guidelines were funded by the American Heart Association. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with BTG Pharmaceuticals, Zoll Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and others.

SOURCE: American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Oct 20. Suppl 2.

Highlights of new updated guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care from the American Heart Association include management of opioid-related emergencies; discussion of health disparities; and a new emphasis on physical, social, and emotional recovery after resuscitation.

The AHA is also exploring digital territory to improve CPR outcomes. The guidelines encourage use of mobile phone technology to summon trained laypeople to individuals requiring CPR, and an adaptive learning suite will be available online for personalized CPR instruction, with lessons catered to individual needs and knowledge levels.

These novel approaches reflect an ongoing effort by the AHA to ensure that the guidelines evolve rapidly with science and technology, reported Raina Merchant, MD, chair of the AHA Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues. In 2015, the committee shifted from 5-year updates to a continuous online review process, citing a need for more immediate implementation of practice-altering data, they wrote in Circulation.

And new approaches do appear to save lives, at least in a hospital setting.

Since 2004, in-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes have been improving, but similar gains have yet to be realized for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

“Much of the variation in survival rates is thought to be due to the strength of the Chain of Survival, the [five] critical actions that must occur in rapid succession to maximize the chance of survival from cardiac arrest,” the committee wrote.

Update adds sixth link to Chains of Survival: Recovery

“Recovery expectations and survivorship plans that address treatment, surveillance, and rehabilitation need to be provided to cardiac arrest survivors and their caregivers at hospital discharge to address the sequelae of cardiac arrest and optimize transitions of care to independent physical, social, emotional, and role function,” the committee wrote.

Dr. Merchant and colleagues identified three “critically important” recommendations for both cardiac arrest survivors and caregivers during the recovery process: structured psychological assessment; multimodal rehabilitation assessment and treatment; and comprehensive, multidisciplinary discharge planning.

The recovery process is now part of all four Chains of Survival, which are specific to in-hospital and out-of-hospital arrest for adults and children.

New advice on opioid overdoses and bystander training

Among instances of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, the committee noted that opioid overdoses are “sharply on the rise,” leading to new, scenario-specific recommendations. Among them, the committee encouraged lay rescuers and trained responders to activate emergency response systems immediately while awaiting improvements with naloxone and other interventions. They also suggested that, for individuals in known or suspected cardiac arrest, high-quality CPR, including compressions and ventilation, should be prioritized over naloxone administration.

In a broader discussion, the committee identified disparities in CPR training, which could explain lower rates of bystander CPR and poorer outcomes among certain demographics, such as black and Hispanic populations, as well as those with lower socioeconomic status.

“Targeting training efforts should consider barriers such as language, financial considerations, and poor access to information,” the committee wrote.

While low bystander CPR in these areas may be improved through mobile phone technology that alerts trained laypeople to individuals in need, the committee noted that this approach may be impacted by cultural and geographic factors. To date, use of mobile devices to improve bystander intervention rates has been demonstrated through “uniformly positive data,” but never in North America.

According to the guidelines, bystander intervention rates may also be improved through video-based learning, which is as effective as in-person, instructor-led training.

This led the AHA to create an online adaptive learning platform, which the organization describes as a “digital resuscitation portfolio” that connects programs and courses such as the Resuscitation Quality Improvement program and the HeartCode blended learning course.

“It will cover all of the guideline changes,” said Monica Sales, communications manager at the AHA. “It’s really groundbreaking because it’s the first time that we’re able to kind of close that gap between new science and new products.”

The online content also addresses CPR considerations for COVID-19, which were first addressed by interim CPR guidance published by the AHA in April.

According to Alexis Topjian, MD, coauthor of the present guidelines and pediatric critical care medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, CPR awareness is more important now than ever.

“The major message [of the guidelines] is that high-quality CPR saves lives,” she said. “So push hard, and push fast. You have the power in your hands to make a difference, more so than ever during this pandemic.”

Concerning coronavirus precautions, Dr. Topjian noted that roughly 70% of out-of-hospital CPR events involve people who know each other, so most bystanders have already been exposed to the person in need, thereby reducing the concern of infection.

When asked about performing CPR on strangers, Dr. Topjian remained encouraging, though she noted that decision making may be informed by local coronavirus rates.

“It’s always a personal choice,” she said.

More for clinicians

For clinicians, Dr. Topjian highlighted several recommendations, including use of epinephrine as soon as possible during CPR, preferential use of a cuffed endotracheal tube, continuous EEG monitoring during and after cardiac arrest, and rapid intervention for clinical seizures and of nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

From a pediatric perspective, Dr. Topjian pointed out a change in breathing rate for infants and children who are receiving CPR or rescue breathing with a pulse, from 12-20 breaths/min to 20-30 breaths/min. While not a new recommendation, Dr. Topjian also pointed out the lifesaving benefit of early defibrillation among pediatric patients.

The guidelines were funded by the American Heart Association. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with BTG Pharmaceuticals, Zoll Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and others.

SOURCE: American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Oct 20. Suppl 2.

Highlights of new updated guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care from the American Heart Association include management of opioid-related emergencies; discussion of health disparities; and a new emphasis on physical, social, and emotional recovery after resuscitation.

The AHA is also exploring digital territory to improve CPR outcomes. The guidelines encourage use of mobile phone technology to summon trained laypeople to individuals requiring CPR, and an adaptive learning suite will be available online for personalized CPR instruction, with lessons catered to individual needs and knowledge levels.

These novel approaches reflect an ongoing effort by the AHA to ensure that the guidelines evolve rapidly with science and technology, reported Raina Merchant, MD, chair of the AHA Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues. In 2015, the committee shifted from 5-year updates to a continuous online review process, citing a need for more immediate implementation of practice-altering data, they wrote in Circulation.

And new approaches do appear to save lives, at least in a hospital setting.

Since 2004, in-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes have been improving, but similar gains have yet to be realized for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

“Much of the variation in survival rates is thought to be due to the strength of the Chain of Survival, the [five] critical actions that must occur in rapid succession to maximize the chance of survival from cardiac arrest,” the committee wrote.

Update adds sixth link to Chains of Survival: Recovery

“Recovery expectations and survivorship plans that address treatment, surveillance, and rehabilitation need to be provided to cardiac arrest survivors and their caregivers at hospital discharge to address the sequelae of cardiac arrest and optimize transitions of care to independent physical, social, emotional, and role function,” the committee wrote.

Dr. Merchant and colleagues identified three “critically important” recommendations for both cardiac arrest survivors and caregivers during the recovery process: structured psychological assessment; multimodal rehabilitation assessment and treatment; and comprehensive, multidisciplinary discharge planning.

The recovery process is now part of all four Chains of Survival, which are specific to in-hospital and out-of-hospital arrest for adults and children.

New advice on opioid overdoses and bystander training

Among instances of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, the committee noted that opioid overdoses are “sharply on the rise,” leading to new, scenario-specific recommendations. Among them, the committee encouraged lay rescuers and trained responders to activate emergency response systems immediately while awaiting improvements with naloxone and other interventions. They also suggested that, for individuals in known or suspected cardiac arrest, high-quality CPR, including compressions and ventilation, should be prioritized over naloxone administration.

In a broader discussion, the committee identified disparities in CPR training, which could explain lower rates of bystander CPR and poorer outcomes among certain demographics, such as black and Hispanic populations, as well as those with lower socioeconomic status.

“Targeting training efforts should consider barriers such as language, financial considerations, and poor access to information,” the committee wrote.

While low bystander CPR in these areas may be improved through mobile phone technology that alerts trained laypeople to individuals in need, the committee noted that this approach may be impacted by cultural and geographic factors. To date, use of mobile devices to improve bystander intervention rates has been demonstrated through “uniformly positive data,” but never in North America.

According to the guidelines, bystander intervention rates may also be improved through video-based learning, which is as effective as in-person, instructor-led training.

This led the AHA to create an online adaptive learning platform, which the organization describes as a “digital resuscitation portfolio” that connects programs and courses such as the Resuscitation Quality Improvement program and the HeartCode blended learning course.

“It will cover all of the guideline changes,” said Monica Sales, communications manager at the AHA. “It’s really groundbreaking because it’s the first time that we’re able to kind of close that gap between new science and new products.”

The online content also addresses CPR considerations for COVID-19, which were first addressed by interim CPR guidance published by the AHA in April.

According to Alexis Topjian, MD, coauthor of the present guidelines and pediatric critical care medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, CPR awareness is more important now than ever.

“The major message [of the guidelines] is that high-quality CPR saves lives,” she said. “So push hard, and push fast. You have the power in your hands to make a difference, more so than ever during this pandemic.”

Concerning coronavirus precautions, Dr. Topjian noted that roughly 70% of out-of-hospital CPR events involve people who know each other, so most bystanders have already been exposed to the person in need, thereby reducing the concern of infection.

When asked about performing CPR on strangers, Dr. Topjian remained encouraging, though she noted that decision making may be informed by local coronavirus rates.

“It’s always a personal choice,” she said.

More for clinicians

For clinicians, Dr. Topjian highlighted several recommendations, including use of epinephrine as soon as possible during CPR, preferential use of a cuffed endotracheal tube, continuous EEG monitoring during and after cardiac arrest, and rapid intervention for clinical seizures and of nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

From a pediatric perspective, Dr. Topjian pointed out a change in breathing rate for infants and children who are receiving CPR or rescue breathing with a pulse, from 12-20 breaths/min to 20-30 breaths/min. While not a new recommendation, Dr. Topjian also pointed out the lifesaving benefit of early defibrillation among pediatric patients.

The guidelines were funded by the American Heart Association. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with BTG Pharmaceuticals, Zoll Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and others.

SOURCE: American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Oct 20. Suppl 2.

FROM CIRCULATION

COVID-19: Convalescent plasma falls short in phase 2 trial

Convalescent plasma may not prevent progression to severe disease or reduce mortality risk in hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19, based on a phase 2 trial involving more than 400 patients in India.

The PLACID trial offers real-world data with “high generalizability,” according to lead author Anup Agarwal, MD, of the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, and colleagues.

“Evidence suggests that convalescent plasma collected from survivors of COVID-19 contains receptor binding domain specific antibodies with potent antiviral activity,” the investigators wrote in the BMJ. “However, effective titers of antiviral neutralizing antibodies, optimal timing for convalescent plasma treatment, optimal timing for plasma donation, and the severity class of patients who are likely to benefit from convalescent plasma remain unclear.”

According to Dr. Agarwal and colleagues, case series and observational studies have suggested that convalescent plasma may reduce viral load, hospital stay, and mortality, but randomized controlled trials to date have ended prematurely because of issues with enrollment and design, making PLACID the first randomized controlled trial of its kind to reach completion.

The open-label, multicenter study involved 464 hospitalized adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 via reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Enrollment also required a respiratory rate of more than 24 breaths/min with an oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 93% or less on room air, or a partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood/fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2 /FiO2 ) ratio between 200 and 300 mm Hg.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either best standard of care (control), or best standard of care plus convalescent plasma, which was given in two doses of 200 mL, 24 hours apart. Patients were assessed via clinical examination, chest imaging, and serial laboratory testing, the latter of which included neutralizing antibody titers on days 0, 3, and 7.

The primary outcome was a 28-day composite of progression to severe disease (PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 100 mm Hg) and all-cause mortality. An array of secondary outcomes were also reported, including symptom resolution, total duration of respiratory support, change in oxygen requirement, and others.

In the convalescent plasma group, 19% of patients progressed to severe disease or died within 28 days, compared with 18% of those in the control group (risk ratio, 1.04; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-1.54), suggesting no statistically significant benefit from the intervention. This lack of benefit was also found in a subgroup analysis of patients with detectable titers of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, and when progression to severe disease and all-cause mortality were analyzed independently across all patients.

Still, at day 7, patients treated with convalescent plasma were significantly more likely to have resolution of fatigue (RR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.02-1.42) and shortness of breath (RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.02-1.32). And at the same time point, patients treated with convalescent plasma were 20% more likely to test negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA (RR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.04-1.5).

In an accompanying editorial, Elizabeth B. Pathak, PhD, of the Women’s Institute for Independent Social Enquiry, Olney, Md., suggested that the reported symptom improvements need to be viewed with skepticism.

“These results should be interpreted with caution, because the trial was not blinded, so knowledge of treatment status could have influenced the reporting of subjective symptoms by patients who survived to day 7,” Dr. Pathak wrote.

Dr. Pathak noted that convalescent plasma did appear to have an antiviral effect, based on the higher rate of negative RNA test results at day 7. She hypothesized that the lack of major corresponding clinical benefit could be explained by detrimental thrombotic processes.

“The net effect of plasma is prothrombotic,” Dr. Pathak wrote, which should raise safety concerns, since “COVID-19 is a life-threatening thrombotic disorder.”

According to Dr. Pathak, large-scale datasets may be giving a false sense of security. She cited a recent safety analysis of 20,000 U.S. patients who received convalescent plasma, in which the investigators excluded 88.2% of cardiac events and 66.3% of thrombotic events, as these were deemed unrelated to transfusion; but this decision was made by the treating physician, without independent review or a defined protocol.

Michael J. Joyner, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., was the lead author of the above safety study, and is leading the Food and Drug Administration expanded access program for convalescent plasma in patients with COVID-19. He suggested that the study by Dr. Agarwal and colleagues was admirable, but flaws in the treatment protocol cast doubt upon the efficacy findings.

“It is very impressive that these investigators performed a large trial of convalescent plasma in the midst of a pandemic,” Dr. Joyner said. “Unfortunately it is unclear how generalizable the findings are because many of the units of plasma had either very low or no antibody titers and because the plasma was given late in the course of the disease. It has been known since at least the 1930s that antibody therapy works best when enough product is given either prophylactically or early in the course of disease.”

Dr. Joyner had a more positive interpretation of the reported symptom improvements.

“It is also interesting to note that while there was no mortality benefit, that – even with the limitations of the study – there was some evidence of improved patient physiology at 7 days,” he said. “So, at one level, [this is] a negative study, but at least [there are] some hints of efficacy given the suboptimal use case in the patients studied.”

The study was funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research, which employs several of the authors and PLACID Trial Collaborators. Dr. Pathak and Dr. Joyner reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Agarwal A et al. BMJ. 2020 Oct 23. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3939 .

Convalescent plasma may not prevent progression to severe disease or reduce mortality risk in hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19, based on a phase 2 trial involving more than 400 patients in India.

The PLACID trial offers real-world data with “high generalizability,” according to lead author Anup Agarwal, MD, of the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, and colleagues.

“Evidence suggests that convalescent plasma collected from survivors of COVID-19 contains receptor binding domain specific antibodies with potent antiviral activity,” the investigators wrote in the BMJ. “However, effective titers of antiviral neutralizing antibodies, optimal timing for convalescent plasma treatment, optimal timing for plasma donation, and the severity class of patients who are likely to benefit from convalescent plasma remain unclear.”

According to Dr. Agarwal and colleagues, case series and observational studies have suggested that convalescent plasma may reduce viral load, hospital stay, and mortality, but randomized controlled trials to date have ended prematurely because of issues with enrollment and design, making PLACID the first randomized controlled trial of its kind to reach completion.

The open-label, multicenter study involved 464 hospitalized adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 via reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Enrollment also required a respiratory rate of more than 24 breaths/min with an oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 93% or less on room air, or a partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood/fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2 /FiO2 ) ratio between 200 and 300 mm Hg.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either best standard of care (control), or best standard of care plus convalescent plasma, which was given in two doses of 200 mL, 24 hours apart. Patients were assessed via clinical examination, chest imaging, and serial laboratory testing, the latter of which included neutralizing antibody titers on days 0, 3, and 7.

The primary outcome was a 28-day composite of progression to severe disease (PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 100 mm Hg) and all-cause mortality. An array of secondary outcomes were also reported, including symptom resolution, total duration of respiratory support, change in oxygen requirement, and others.

In the convalescent plasma group, 19% of patients progressed to severe disease or died within 28 days, compared with 18% of those in the control group (risk ratio, 1.04; 95% confidence interval, 0.71-1.54), suggesting no statistically significant benefit from the intervention. This lack of benefit was also found in a subgroup analysis of patients with detectable titers of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, and when progression to severe disease and all-cause mortality were analyzed independently across all patients.

Still, at day 7, patients treated with convalescent plasma were significantly more likely to have resolution of fatigue (RR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.02-1.42) and shortness of breath (RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.02-1.32). And at the same time point, patients treated with convalescent plasma were 20% more likely to test negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA (RR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.04-1.5).

In an accompanying editorial, Elizabeth B. Pathak, PhD, of the Women’s Institute for Independent Social Enquiry, Olney, Md., suggested that the reported symptom improvements need to be viewed with skepticism.