User login

Patterns and Predictors of Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are integral to the care of hospitalized patients in the United States.1 Consequently, utilization of these devices in acutely ill patients has steadily increased in the past decade.2 Although originally designed to support the delivery of total parenteral nutrition, PICCs have found broader applications in the hospital setting given the ease and safety of placement, the advances in technology that facilitate insertion, and the growing availability of specially trained vascular nurses that place these devices at the bedside.3 Furthermore, because they are placed in deeper veins of the arm, PICCs are more durable than peripheral catheters and can support venous access for extended durations.4-6

However, the growing use of PICCs has led to the realization that these devices are not without attendant risks. For example, PICCs are associated with venous thromboembolism (VTE) and central-line associated blood stream infection (CLABSI).7,8 Additionally, complications such as catheter occlusion and tip migration commonly occur and may interrupt care or necessitate device removal.9-11 Hence, thoughtful weighing of the risks against the benefits of PICC use prior to placement is necessary. To facilitate such decision-making, we developed the Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous (IV) Catheters (MAGIC) criteria,12 which is an evidence-based tool that defines when the use of a PICC is appropriate in hospitalized adults.

The use of PICCs for infusion of peripherally compatible therapies for 5 or fewer days is rated as inappropriate by MAGIC.12 This strategy is also endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of catheter-related infections.13 Despite these recommendations, short-term PICC use remains common. For example, a study conducted at a tertiary pediatric care center reported a trend toward shorter PICC dwell times and increasing rates of early removal.2 However, factors that prompt such short-term PICC use are poorly understood. Without understanding drivers and outcomes of short-term PICC use, interventions to prevent such practice are unlikely to succeed.

Therefore, by using data from a multicenter cohort study, we examined patterns of short-term PICC use and sought to identify which patient, provider, and device factors were associated with such use. We hypothesized that short-term placement would be associated with difficult venous access and would also be associated with the risk of major and minor complications.

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

We used data from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) Consortium to examine patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use.14 As a multi-institutional clinical quality initiative sponsored by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network, HMS aims to improve the quality of care by preventing adverse events in hospitalized medical patients.4,15-17 In January of 2014, dedicated, trained abstractors started collecting data on PICC placements at participating HMS hospitals by using a standard protocol and template for data collection. Patients who received PICCs while admitted to either a general medicine unit or an intensive care unit (ICU) during clinical care were eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they were (a) under the age of 18 years, (b) pregnant, (c) admitted to a nonmedical service (eg, surgery), or (d) admitted under observation status.

Every 14 days, each hospital collected data on the first 17 eligible patients that received a PICC, with at least 7 of these placements occurring in an ICU setting. All patients were prospectively followed until the PICC was removed, death, or until 70 days after insertion, whichever occurred first. For patients who had their PICC removed prior to hospital discharge, follow-up occurred via a review of medical records. For those discharged with a PICC in place, both medical record review and telephone follow-up were performed. To ensure data quality, annual random audits at each participating hospital were performed by the coordinating center at the University of Michigan.

For this analysis, we included all available data as of June 30, 2016. However, HMS hospitals continue to collect data on PICC use and outcomes as part of an ongoing clinical quality initiative to reduce the incidence of PICC-related complications.

Patient, Provider, and Device Data

Patient characteristics, including demographics, detailed medical history, comorbidities, physical findings, laboratory results, and medications were abstracted directly from medical records. To estimate the comorbidity burden, the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score was calculated for each patient by using data available in the medical record at the time of PICC placement.18 Data, such as the documented indication for PICC insertion and the reason for removal, were obtained directly from medical records. Provider characteristics, including the specialty of the attending physician at the time of insertion and the type of operator who inserted the PICC, were also collected. Institutional characteristics, such as total number of beds, teaching versus nonteaching, and urban versus rural, were obtained from hospital publicly reported data and semiannual surveys of HMS sites.19,20 Data on device characteristics, such as catheter gauge, coating, insertion attempts, tip location, and number of lumens, were abstracted from PICC insertion notes.

Outcomes of Interest

The outcome of interest was short-term PICC use, defined as PICCs removed within 5 days of insertion. Patients who expired with a PICC in situ were excluded. Secondary outcomes of interest included PICC-related complications, categorized as major (eg, symptomatic VTE and CLABSI) or minor (eg, catheter occlusion, superficial thrombosis, mechanical complications [kinking, coiling], exit site infection, and tip migration). Symptomatic VTE was defined as clinically diagnosed deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and/or pulmonary embolism (PE) not present at the time of PICC placement and confirmed via imaging (ultrasound or venogram for DVT; computed tomography scan, ventilation perfusion scan, or pulmonary angiogram for PE). CLABSI was defined in accordance with the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network criteria or according to Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendations.21,22 All minor PICC complications were defined in accordance with prior published definitions.4

Statistical Analysis

Cases of short-term PICC use were identified and compared with patients with a PICC dwell time of 6 or more days by patient, provider, and device characteristics. The initial analyses for the associations of putative factors with short-term PICC use were performed using χ2 or Wilcoxon tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Univariable mixed effect logistic regression models (with a random hospital-specific intercept) were then used to control for hospital-level clustering. Next, a mixed effects multivariable logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with short-term PICC use. Variables with P ≤ .25 were considered as candidate predictors for the final multivariable model, which was chosen through a stepwise variable selection algorithm performed on 1000 bootstrapped data sets.23 Variables in the final model were retained based on their frequency of selection in the bootstrapped samples, significance level, and contribution to the overall model likelihood. Results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). SAS for Windows (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for analyses.

Ethical and Regulatory Oversight

The study was classified as “not regulated” by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (HUM00078730).

RESULTS

Overall Characteristics of the Study Cohort

Characteristics of Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use

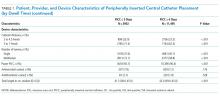

Of the 15,397 PICCs included, we identified 3902 PICCs (25.3%) with a dwell time of ≤5 days (median = 3 days; IQR, 2-4 days). When compared to PICCs that were in place for longer durations, no significant differences in age or comorbidity scores were observed. Importantly, despite recommendations to avoid PICCs in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] ≤ 59 ml/min), 1292 (33.1%) short-term PICCs occurred in patients that met such criteria.

Among short-term PICCs, 3618 (92.7%) were power-capable devices, 2785 (71.4%) were 5-French, and 2813 (72.1%) were multilumen. Indications for the use of short-term PICCs differed from longer term devices in important ways (P < .001). For example, the most common documented indication for short-term PICC use was difficult venous access (28.2%), while for long-term PICCs, it was antibiotic administration (39.8%). General internists and hospitalists were the most common attending physicians for patients with short-term and long-term PICCs (65.1% and 65.5%, respectively [P = .73]). Also, the proportion of critical care physicians responsible for patients with short versus long-term PICC use was similar (14.0% vs 15.0%, respectively [P = .123]). Of the short-term PICCs, 2583 (66.2%) were inserted by vascular access nurses, 795 (20.4%) by interventional radiologists, and 439 (11.3%) by advance practice professionals. Almost all of the PICCs placed ≤5 days (95.5%) were removed during hospitalization.

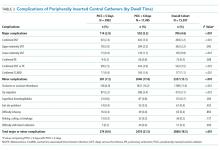

Complications Associated with Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use

DISCUSSION

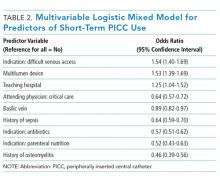

This large, multisite prospective cohort study is the first to examine patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use in hospitalized adults. By examining clinically granular data derived from the medical records of patients across 52 hospitals, we found that short-term use was common, representing 25% of all PICCs placed. Almost all such PICCs were removed prior to discharge, suggesting that they were placed primarily to meet acute needs during hospitalization. Multivariable models indicated that patients with difficult venous access, multilumen devices, and teaching hospital settings were associated with short-term use. Given that (a) short term PICC use is not recommended by published evidence-based guidelines,12,13 (b) both major and minor complications were not uncommon despite brief exposure, and (c) specific factors might be targeted to avoid such use, strategies to improve PICC decision-making in the hospital appear increasingly necessary.

In our study, difficult venous access was the most common documented indication for short-term PICC placement. For patients in whom an anticipated catheter dwell time of 5 days or less is expected, MAGIC recommends the consideration of midline or peripheral IV catheters placed under ultrasound guidance.12 A midline is a type of peripheral IV catheter that is about 7.5 cm to 25 cm in length and is typically inserted in the larger diameter veins of the upper extremity, such as the cephalic or basilic veins, with the tip terminating distal to the subclavian vein.7,12 While there is a paucity of information that directly compares PICCs to midlines, some data suggest a lower risk of bloodstream infection and thrombosis associated with the latter.24-26 For example, at one quaternary teaching hospital, house staff who are trained to insert midline catheters under ultrasound guidance in critically ill patients with difficult venous access reported no CLABSI and DVT events.26

Interestingly, multilumen catheters were used twice as often as single lumen catheters in patients with short-term PICCs. In these instances, the use of additional lumens is questionable, as infusion of multiple incompatible fluids was not commonly listed as an indication prompting PICC use. Because multilumen PICCs are associated with higher risks of both VTE and CLABSI compared to single lumen devices, such use represents an important safety concern.27-29 Institutional efforts that not only limit the use of multilumen PICCs but also fundamentally define when use of a PICC is appropriate may substantially improve outcomes related to vascular access.28,30,31We observed that short-term PICCs were more common in teaching compared to nonteaching hospitals. While the design of the present study precludes understanding the reasons for such a difference, some plausible theories include the presence of physician trainees who may not appreciate the risks of PICC use, diminishing peripheral IV access securement skills, and the lack of alternatives to PICC use. Educating trainees who most often order PICCs in teaching settings as to when they should or should not consider this device may represent an important quality improvement opportunity.32 Similarly, auditing and assessing the clinical skills of those entrusted to place peripheral IVs might prove helpful.33,34 Finally, the introduction of a midline program, or similar programs that expand the scope of vascular access teams to place alternative devices, should be explored as a means to improve PICC use and patient safety.

Our study also found that a third of patients who received PICCs for 5 or fewer days had moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. In these patients who may require renal replacement therapy, prior PICC placement is among the strongest predictors of arteriovenous fistula failure.35,36 Therefore, even though national guidelines discourage the use of PICCs in these patients and recommend alternative routes of venous access,12,37,38 such practice is clearly not happening. System-based interventions that begin by identifying patients who require vein preservation (eg, those with a GFR < 45 ml/min) and are therefore not appropriate for a PICC would be a welcomed first step in improving care for such patients.37,38Our study has limitations. First, the observational nature of the study limits the ability to assess for causality or to account for the effects of unmeasured confounders. Second, while the use of medical records to collect granular data is valuable, differences in documentation patterns within and across hospitals, including patterns of missing data, may produce a misclassification of covariates or outcomes. Third, while we found that higher rates of short-term PICC use were associated with teaching hospitals and patients with difficult venous access, we were unable to determine the precise reasons for this practice trend. Qualitative or mixed-methods approaches to understand provider decision-making in these settings would be welcomed.

Our study also has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically describe and evaluate patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use. The finding that PICCs placed for difficult venous access is a dominant category of short-term placement confirms clinical suspicions regarding inappropriate use and strengthens the need for pathways or protocols to manage such patients. Second, the inclusion of medical patients in diverse institutions offers not only real-world insights related to PICC use, but also offers findings that should be generalizable to other hospitals and health systems. Third, the use of a robust data collection strategy that emphasized standardized data collection, dedicated trained abstractors, and random audits to ensure data quality strengthen the findings of this work. Finally, our findings highlight an urgent need to develop policies related to PICC use, including limiting the use of multiple lumens and avoidance in patients with moderate to severe kidney disease.

In conclusion, short-term use of PICCs is prevalent and associated with key patient, provider, and device factors. Such use is also associated with complications, such as catheter occlusion, tip migration, VTE, and CLABSI. Limiting the use of multiple-lumen PICCs, enhancing education for when a PICC should be used, and defining strategies for patients with difficult access may help reduce inappropriate PICC use and improve patient safety. Future studies to examine implementation of such interventions would be welcomed.

Disclosure: Drs. Paje, Conlon, Swaminathan, and Boldenow disclose no conflicts of interest. Dr. Chopra has received honoraria for talks at hospitals as a visiting professor. Dr. Flanders discloses consultancies for the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the Society of Hospital Medicine, royalties from Wiley Publishing, honoraria for various talks at hospitals as a visiting professor, grants from the CDC Foundation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM), and Michigan Hospital Association, and expert witness testimony. Dr. Bernstein discloses consultancies for Blue Care Network and grants from BCBSM, Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kaatz discloses no relevant conflicts of interest. BCBSM and Blue Care Network provided support for the Michigan HMS Consortium as part of the BCBSM Value Partnerships program. Although BCBSM and HMS work collaboratively, the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints of BCBSM or any of its employees. Dr. Chopra is supported by a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1-K08-HS022835-01). BCBSM and Blue Care Network supported data collection at each participating site and funded the data coordinating center but had no role in study concept, interpretation of findings, or in the preparation, final approval, or decision to submit the manuscript.

1. Al Raiy B, Fakih MG, Bryan-Nomides N, et al. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters in the acute care setting: A safe alternative to high-risk short-term central venous catheters. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(2):149-153. PubMed

2. Gibson C, Connolly BL, Moineddin R, Mahant S, Filipescu D, Amaral JG. Peripherally inserted central catheters: use at a tertiary care pediatric center. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(9):1323-1331. PubMed

3. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S. The problem with peripherally inserted central catheters. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1527-1528. PubMed

4. Chopra V, Smith S, Swaminathan L, et al. Variations in Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use and Outcomes in Michigan Hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):548-551. PubMed

5. Cowl CT, Weinstock JV, Al-Jurf A, Ephgrave K, Murray JA, Dillon K. Complications and cost associated with parenteral nutrition delivered to hospitalized patients through either subclavian or peripherally-inserted central catheters. Clin Nutr. 2000;19(4):237-243. PubMed

6. MacDonald AS, Master SK, Moffitt EA. A comparative study of peripherally inserted silicone catheters for parenteral nutrition. Can J Anaesth. 1977;24(2):263-269. PubMed

7. Chopra V, O’Horo JC, Rogers MA, Maki DG, Safdar N. The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(9):908-918. PubMed

8. Chopra V, Anand S, Hickner A, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):311-325. PubMed

9. Beccaria P, Silvetti S, Mucci M, Battini I, Brambilla P, Zangrillo A. Contributing factors for a late spontaneous peripherally inserted central catheter migration: a case report and review of literature. J Vasc Access. 2015;16(3):178-182. PubMed

10. Turcotte S, Dube S, Beauchamp G. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters are not superior to central venous catheters in the acute care of surgical patients on the ward. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1605-1619. PubMed

11. Pikwer A, Akeson J, Lindgren S. Complications associated with peripheral or central routes for central venous cannulation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(1):65-71. PubMed

12. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results From a Multispecialty Panel Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Intern Med. 15 2015;163(6 Suppl):S1-S40. PubMed

13. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(4 Suppl 1):S1-S34. PubMed

14. Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium. 2016; http://mi-hms.org/. Accessed November 11, 2016.

15. Greene MT, Spyropoulos AC, Chopra V, et al. Validation of Risk Assessment Models of Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Medical Patients. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):1001.e1009-1001.e1018. PubMed

16. Greene MT, Flanders SA, Woller SC, Bernstein SJ, Chopra V. The Association Between PICC Use and Venous Thromboembolism in Upper and Lower Extremities. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):986-993. PubMed

17. Flanders SA, Greene MT, Grant P, et al. Hospital performance for pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and rate of venous thromboembolism : a cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1577-1584. PubMed

18. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619. PubMed

19. Hospital Bed Inventory. 2016; http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/HOSPBEDINV_October_3__2016_536834_7.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2016.

20. Compare Hospitals. 2016; http://www.leapfroggroup.org/compare-hospitals. Accessed November 22, 2016.

21. NHSN Patient Safety Component Manual. 2016; http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/pcsmanual_current.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2016.

22. Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1-45. PubMed

23. Austin PC, Tu JV. Bootstrap Methods for Developing Predictive Models. Am Stat. 2004;58(2):131-137.

24. Pathak R, Patel A, Enuh H, Adekunle O, Shrisgantharajah V, Diaz K. The Incidence of Central Line-Associated Bacteremia After the Introduction of Midline Catheters in a Ventilator Unit Population. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2015;23(3):131-134. PubMed

25. Adams DZ, Little A, Vinsant C, Khandelwal S. The Midline Catheter: A Clinical Review. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(3):252-258. PubMed

26. Deutsch GB, Sathyanarayana SA, Singh N, Nicastro J. Ultrasound-guided placement of midline catheters in the surgical intensive care unit: a cost-effective proposal for timely central line removal. J Surg Res. 2014;191(1):1-5. PubMed

27. Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream Infection, Venous Thrombosis, and Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters: Reappraising the Evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):733-741. PubMed

28. Ratz D, Hofer T, Flanders SA, Saint S, Chopra V. Limiting the Number of Lumens in Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters to Improve Outcomes and Reduce Cost: A Simulation Study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(7):811-817. PubMed

29. Pongruangporn M, Ajenjo MC, Russo AJ, et al. Patient- and device-specific risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(2):184-189. PubMed

30. Shannon RP, Patel B, Cummins D, Shannon AH, Ganguli G, Lu Y. Economics of central line--associated bloodstream infections. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(6 Suppl):7S-16S. PubMed

31. O’Brien J, Paquet F, Lindsay R, Valenti D. Insertion of PICCs with minimum number of lumens reduces complications and costs. J AmColl Radiol. 2013;10(11):864-868. PubMed

32. Wong BM, Etchells EE, Kuper A, Levinson W, Shojania KG. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1425-1439. PubMed

33. Conlon T, Himebauch A, Marie Cahill A, et al. 1246: Bedside Picc Placement by Pediatric Icu Providers Is Feasible and Safe. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12 Suppl 1):387.

34. Moran J, Colbert CY, Song J, et al. Screening for novel risk factors related to peripherally inserted central catheter-associated complications. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(8):481-489. PubMed

35. Gonsalves CF, Eschelman DJ, Sullivan KL, DuBois N, Bonn J. Incidence of central vein stenosis and occlusion following upper extremity PICC and port placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26(2):123-127. PubMed

36. El Ters M, Schears GJ, Taler SJ, et al. Association between prior peripherally inserted central catheters and lack of functioning arteriovenous fistulas: a case-control study in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(4):601-608. PubMed

37. Vascular Access 2006 Work Group. Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48 Suppl 1:S248-S273. PubMed

38. Hoggard J, Saad T, Schon D, et al. Guidelines for venous access in patients with chronic kidney disease. A Position Statement from the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology, Clinical Practice Committee and the Association for Vascular Access. Semin Dial. 2008;21(2):186-191. PubMed

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are integral to the care of hospitalized patients in the United States.1 Consequently, utilization of these devices in acutely ill patients has steadily increased in the past decade.2 Although originally designed to support the delivery of total parenteral nutrition, PICCs have found broader applications in the hospital setting given the ease and safety of placement, the advances in technology that facilitate insertion, and the growing availability of specially trained vascular nurses that place these devices at the bedside.3 Furthermore, because they are placed in deeper veins of the arm, PICCs are more durable than peripheral catheters and can support venous access for extended durations.4-6

However, the growing use of PICCs has led to the realization that these devices are not without attendant risks. For example, PICCs are associated with venous thromboembolism (VTE) and central-line associated blood stream infection (CLABSI).7,8 Additionally, complications such as catheter occlusion and tip migration commonly occur and may interrupt care or necessitate device removal.9-11 Hence, thoughtful weighing of the risks against the benefits of PICC use prior to placement is necessary. To facilitate such decision-making, we developed the Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous (IV) Catheters (MAGIC) criteria,12 which is an evidence-based tool that defines when the use of a PICC is appropriate in hospitalized adults.

The use of PICCs for infusion of peripherally compatible therapies for 5 or fewer days is rated as inappropriate by MAGIC.12 This strategy is also endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of catheter-related infections.13 Despite these recommendations, short-term PICC use remains common. For example, a study conducted at a tertiary pediatric care center reported a trend toward shorter PICC dwell times and increasing rates of early removal.2 However, factors that prompt such short-term PICC use are poorly understood. Without understanding drivers and outcomes of short-term PICC use, interventions to prevent such practice are unlikely to succeed.

Therefore, by using data from a multicenter cohort study, we examined patterns of short-term PICC use and sought to identify which patient, provider, and device factors were associated with such use. We hypothesized that short-term placement would be associated with difficult venous access and would also be associated with the risk of major and minor complications.

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

We used data from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) Consortium to examine patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use.14 As a multi-institutional clinical quality initiative sponsored by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network, HMS aims to improve the quality of care by preventing adverse events in hospitalized medical patients.4,15-17 In January of 2014, dedicated, trained abstractors started collecting data on PICC placements at participating HMS hospitals by using a standard protocol and template for data collection. Patients who received PICCs while admitted to either a general medicine unit or an intensive care unit (ICU) during clinical care were eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they were (a) under the age of 18 years, (b) pregnant, (c) admitted to a nonmedical service (eg, surgery), or (d) admitted under observation status.

Every 14 days, each hospital collected data on the first 17 eligible patients that received a PICC, with at least 7 of these placements occurring in an ICU setting. All patients were prospectively followed until the PICC was removed, death, or until 70 days after insertion, whichever occurred first. For patients who had their PICC removed prior to hospital discharge, follow-up occurred via a review of medical records. For those discharged with a PICC in place, both medical record review and telephone follow-up were performed. To ensure data quality, annual random audits at each participating hospital were performed by the coordinating center at the University of Michigan.

For this analysis, we included all available data as of June 30, 2016. However, HMS hospitals continue to collect data on PICC use and outcomes as part of an ongoing clinical quality initiative to reduce the incidence of PICC-related complications.

Patient, Provider, and Device Data

Patient characteristics, including demographics, detailed medical history, comorbidities, physical findings, laboratory results, and medications were abstracted directly from medical records. To estimate the comorbidity burden, the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score was calculated for each patient by using data available in the medical record at the time of PICC placement.18 Data, such as the documented indication for PICC insertion and the reason for removal, were obtained directly from medical records. Provider characteristics, including the specialty of the attending physician at the time of insertion and the type of operator who inserted the PICC, were also collected. Institutional characteristics, such as total number of beds, teaching versus nonteaching, and urban versus rural, were obtained from hospital publicly reported data and semiannual surveys of HMS sites.19,20 Data on device characteristics, such as catheter gauge, coating, insertion attempts, tip location, and number of lumens, were abstracted from PICC insertion notes.

Outcomes of Interest

The outcome of interest was short-term PICC use, defined as PICCs removed within 5 days of insertion. Patients who expired with a PICC in situ were excluded. Secondary outcomes of interest included PICC-related complications, categorized as major (eg, symptomatic VTE and CLABSI) or minor (eg, catheter occlusion, superficial thrombosis, mechanical complications [kinking, coiling], exit site infection, and tip migration). Symptomatic VTE was defined as clinically diagnosed deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and/or pulmonary embolism (PE) not present at the time of PICC placement and confirmed via imaging (ultrasound or venogram for DVT; computed tomography scan, ventilation perfusion scan, or pulmonary angiogram for PE). CLABSI was defined in accordance with the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network criteria or according to Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendations.21,22 All minor PICC complications were defined in accordance with prior published definitions.4

Statistical Analysis

Cases of short-term PICC use were identified and compared with patients with a PICC dwell time of 6 or more days by patient, provider, and device characteristics. The initial analyses for the associations of putative factors with short-term PICC use were performed using χ2 or Wilcoxon tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Univariable mixed effect logistic regression models (with a random hospital-specific intercept) were then used to control for hospital-level clustering. Next, a mixed effects multivariable logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with short-term PICC use. Variables with P ≤ .25 were considered as candidate predictors for the final multivariable model, which was chosen through a stepwise variable selection algorithm performed on 1000 bootstrapped data sets.23 Variables in the final model were retained based on their frequency of selection in the bootstrapped samples, significance level, and contribution to the overall model likelihood. Results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). SAS for Windows (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for analyses.

Ethical and Regulatory Oversight

The study was classified as “not regulated” by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (HUM00078730).

RESULTS

Overall Characteristics of the Study Cohort

Characteristics of Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use

Of the 15,397 PICCs included, we identified 3902 PICCs (25.3%) with a dwell time of ≤5 days (median = 3 days; IQR, 2-4 days). When compared to PICCs that were in place for longer durations, no significant differences in age or comorbidity scores were observed. Importantly, despite recommendations to avoid PICCs in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] ≤ 59 ml/min), 1292 (33.1%) short-term PICCs occurred in patients that met such criteria.

Among short-term PICCs, 3618 (92.7%) were power-capable devices, 2785 (71.4%) were 5-French, and 2813 (72.1%) were multilumen. Indications for the use of short-term PICCs differed from longer term devices in important ways (P < .001). For example, the most common documented indication for short-term PICC use was difficult venous access (28.2%), while for long-term PICCs, it was antibiotic administration (39.8%). General internists and hospitalists were the most common attending physicians for patients with short-term and long-term PICCs (65.1% and 65.5%, respectively [P = .73]). Also, the proportion of critical care physicians responsible for patients with short versus long-term PICC use was similar (14.0% vs 15.0%, respectively [P = .123]). Of the short-term PICCs, 2583 (66.2%) were inserted by vascular access nurses, 795 (20.4%) by interventional radiologists, and 439 (11.3%) by advance practice professionals. Almost all of the PICCs placed ≤5 days (95.5%) were removed during hospitalization.

Complications Associated with Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use

DISCUSSION

This large, multisite prospective cohort study is the first to examine patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use in hospitalized adults. By examining clinically granular data derived from the medical records of patients across 52 hospitals, we found that short-term use was common, representing 25% of all PICCs placed. Almost all such PICCs were removed prior to discharge, suggesting that they were placed primarily to meet acute needs during hospitalization. Multivariable models indicated that patients with difficult venous access, multilumen devices, and teaching hospital settings were associated with short-term use. Given that (a) short term PICC use is not recommended by published evidence-based guidelines,12,13 (b) both major and minor complications were not uncommon despite brief exposure, and (c) specific factors might be targeted to avoid such use, strategies to improve PICC decision-making in the hospital appear increasingly necessary.

In our study, difficult venous access was the most common documented indication for short-term PICC placement. For patients in whom an anticipated catheter dwell time of 5 days or less is expected, MAGIC recommends the consideration of midline or peripheral IV catheters placed under ultrasound guidance.12 A midline is a type of peripheral IV catheter that is about 7.5 cm to 25 cm in length and is typically inserted in the larger diameter veins of the upper extremity, such as the cephalic or basilic veins, with the tip terminating distal to the subclavian vein.7,12 While there is a paucity of information that directly compares PICCs to midlines, some data suggest a lower risk of bloodstream infection and thrombosis associated with the latter.24-26 For example, at one quaternary teaching hospital, house staff who are trained to insert midline catheters under ultrasound guidance in critically ill patients with difficult venous access reported no CLABSI and DVT events.26

Interestingly, multilumen catheters were used twice as often as single lumen catheters in patients with short-term PICCs. In these instances, the use of additional lumens is questionable, as infusion of multiple incompatible fluids was not commonly listed as an indication prompting PICC use. Because multilumen PICCs are associated with higher risks of both VTE and CLABSI compared to single lumen devices, such use represents an important safety concern.27-29 Institutional efforts that not only limit the use of multilumen PICCs but also fundamentally define when use of a PICC is appropriate may substantially improve outcomes related to vascular access.28,30,31We observed that short-term PICCs were more common in teaching compared to nonteaching hospitals. While the design of the present study precludes understanding the reasons for such a difference, some plausible theories include the presence of physician trainees who may not appreciate the risks of PICC use, diminishing peripheral IV access securement skills, and the lack of alternatives to PICC use. Educating trainees who most often order PICCs in teaching settings as to when they should or should not consider this device may represent an important quality improvement opportunity.32 Similarly, auditing and assessing the clinical skills of those entrusted to place peripheral IVs might prove helpful.33,34 Finally, the introduction of a midline program, or similar programs that expand the scope of vascular access teams to place alternative devices, should be explored as a means to improve PICC use and patient safety.

Our study also found that a third of patients who received PICCs for 5 or fewer days had moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. In these patients who may require renal replacement therapy, prior PICC placement is among the strongest predictors of arteriovenous fistula failure.35,36 Therefore, even though national guidelines discourage the use of PICCs in these patients and recommend alternative routes of venous access,12,37,38 such practice is clearly not happening. System-based interventions that begin by identifying patients who require vein preservation (eg, those with a GFR < 45 ml/min) and are therefore not appropriate for a PICC would be a welcomed first step in improving care for such patients.37,38Our study has limitations. First, the observational nature of the study limits the ability to assess for causality or to account for the effects of unmeasured confounders. Second, while the use of medical records to collect granular data is valuable, differences in documentation patterns within and across hospitals, including patterns of missing data, may produce a misclassification of covariates or outcomes. Third, while we found that higher rates of short-term PICC use were associated with teaching hospitals and patients with difficult venous access, we were unable to determine the precise reasons for this practice trend. Qualitative or mixed-methods approaches to understand provider decision-making in these settings would be welcomed.

Our study also has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically describe and evaluate patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use. The finding that PICCs placed for difficult venous access is a dominant category of short-term placement confirms clinical suspicions regarding inappropriate use and strengthens the need for pathways or protocols to manage such patients. Second, the inclusion of medical patients in diverse institutions offers not only real-world insights related to PICC use, but also offers findings that should be generalizable to other hospitals and health systems. Third, the use of a robust data collection strategy that emphasized standardized data collection, dedicated trained abstractors, and random audits to ensure data quality strengthen the findings of this work. Finally, our findings highlight an urgent need to develop policies related to PICC use, including limiting the use of multiple lumens and avoidance in patients with moderate to severe kidney disease.

In conclusion, short-term use of PICCs is prevalent and associated with key patient, provider, and device factors. Such use is also associated with complications, such as catheter occlusion, tip migration, VTE, and CLABSI. Limiting the use of multiple-lumen PICCs, enhancing education for when a PICC should be used, and defining strategies for patients with difficult access may help reduce inappropriate PICC use and improve patient safety. Future studies to examine implementation of such interventions would be welcomed.

Disclosure: Drs. Paje, Conlon, Swaminathan, and Boldenow disclose no conflicts of interest. Dr. Chopra has received honoraria for talks at hospitals as a visiting professor. Dr. Flanders discloses consultancies for the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the Society of Hospital Medicine, royalties from Wiley Publishing, honoraria for various talks at hospitals as a visiting professor, grants from the CDC Foundation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM), and Michigan Hospital Association, and expert witness testimony. Dr. Bernstein discloses consultancies for Blue Care Network and grants from BCBSM, Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kaatz discloses no relevant conflicts of interest. BCBSM and Blue Care Network provided support for the Michigan HMS Consortium as part of the BCBSM Value Partnerships program. Although BCBSM and HMS work collaboratively, the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints of BCBSM or any of its employees. Dr. Chopra is supported by a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1-K08-HS022835-01). BCBSM and Blue Care Network supported data collection at each participating site and funded the data coordinating center but had no role in study concept, interpretation of findings, or in the preparation, final approval, or decision to submit the manuscript.

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are integral to the care of hospitalized patients in the United States.1 Consequently, utilization of these devices in acutely ill patients has steadily increased in the past decade.2 Although originally designed to support the delivery of total parenteral nutrition, PICCs have found broader applications in the hospital setting given the ease and safety of placement, the advances in technology that facilitate insertion, and the growing availability of specially trained vascular nurses that place these devices at the bedside.3 Furthermore, because they are placed in deeper veins of the arm, PICCs are more durable than peripheral catheters and can support venous access for extended durations.4-6

However, the growing use of PICCs has led to the realization that these devices are not without attendant risks. For example, PICCs are associated with venous thromboembolism (VTE) and central-line associated blood stream infection (CLABSI).7,8 Additionally, complications such as catheter occlusion and tip migration commonly occur and may interrupt care or necessitate device removal.9-11 Hence, thoughtful weighing of the risks against the benefits of PICC use prior to placement is necessary. To facilitate such decision-making, we developed the Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous (IV) Catheters (MAGIC) criteria,12 which is an evidence-based tool that defines when the use of a PICC is appropriate in hospitalized adults.

The use of PICCs for infusion of peripherally compatible therapies for 5 or fewer days is rated as inappropriate by MAGIC.12 This strategy is also endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of catheter-related infections.13 Despite these recommendations, short-term PICC use remains common. For example, a study conducted at a tertiary pediatric care center reported a trend toward shorter PICC dwell times and increasing rates of early removal.2 However, factors that prompt such short-term PICC use are poorly understood. Without understanding drivers and outcomes of short-term PICC use, interventions to prevent such practice are unlikely to succeed.

Therefore, by using data from a multicenter cohort study, we examined patterns of short-term PICC use and sought to identify which patient, provider, and device factors were associated with such use. We hypothesized that short-term placement would be associated with difficult venous access and would also be associated with the risk of major and minor complications.

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

We used data from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) Consortium to examine patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use.14 As a multi-institutional clinical quality initiative sponsored by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network, HMS aims to improve the quality of care by preventing adverse events in hospitalized medical patients.4,15-17 In January of 2014, dedicated, trained abstractors started collecting data on PICC placements at participating HMS hospitals by using a standard protocol and template for data collection. Patients who received PICCs while admitted to either a general medicine unit or an intensive care unit (ICU) during clinical care were eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they were (a) under the age of 18 years, (b) pregnant, (c) admitted to a nonmedical service (eg, surgery), or (d) admitted under observation status.

Every 14 days, each hospital collected data on the first 17 eligible patients that received a PICC, with at least 7 of these placements occurring in an ICU setting. All patients were prospectively followed until the PICC was removed, death, or until 70 days after insertion, whichever occurred first. For patients who had their PICC removed prior to hospital discharge, follow-up occurred via a review of medical records. For those discharged with a PICC in place, both medical record review and telephone follow-up were performed. To ensure data quality, annual random audits at each participating hospital were performed by the coordinating center at the University of Michigan.

For this analysis, we included all available data as of June 30, 2016. However, HMS hospitals continue to collect data on PICC use and outcomes as part of an ongoing clinical quality initiative to reduce the incidence of PICC-related complications.

Patient, Provider, and Device Data

Patient characteristics, including demographics, detailed medical history, comorbidities, physical findings, laboratory results, and medications were abstracted directly from medical records. To estimate the comorbidity burden, the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score was calculated for each patient by using data available in the medical record at the time of PICC placement.18 Data, such as the documented indication for PICC insertion and the reason for removal, were obtained directly from medical records. Provider characteristics, including the specialty of the attending physician at the time of insertion and the type of operator who inserted the PICC, were also collected. Institutional characteristics, such as total number of beds, teaching versus nonteaching, and urban versus rural, were obtained from hospital publicly reported data and semiannual surveys of HMS sites.19,20 Data on device characteristics, such as catheter gauge, coating, insertion attempts, tip location, and number of lumens, were abstracted from PICC insertion notes.

Outcomes of Interest

The outcome of interest was short-term PICC use, defined as PICCs removed within 5 days of insertion. Patients who expired with a PICC in situ were excluded. Secondary outcomes of interest included PICC-related complications, categorized as major (eg, symptomatic VTE and CLABSI) or minor (eg, catheter occlusion, superficial thrombosis, mechanical complications [kinking, coiling], exit site infection, and tip migration). Symptomatic VTE was defined as clinically diagnosed deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and/or pulmonary embolism (PE) not present at the time of PICC placement and confirmed via imaging (ultrasound or venogram for DVT; computed tomography scan, ventilation perfusion scan, or pulmonary angiogram for PE). CLABSI was defined in accordance with the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network criteria or according to Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendations.21,22 All minor PICC complications were defined in accordance with prior published definitions.4

Statistical Analysis

Cases of short-term PICC use were identified and compared with patients with a PICC dwell time of 6 or more days by patient, provider, and device characteristics. The initial analyses for the associations of putative factors with short-term PICC use were performed using χ2 or Wilcoxon tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Univariable mixed effect logistic regression models (with a random hospital-specific intercept) were then used to control for hospital-level clustering. Next, a mixed effects multivariable logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with short-term PICC use. Variables with P ≤ .25 were considered as candidate predictors for the final multivariable model, which was chosen through a stepwise variable selection algorithm performed on 1000 bootstrapped data sets.23 Variables in the final model were retained based on their frequency of selection in the bootstrapped samples, significance level, and contribution to the overall model likelihood. Results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). SAS for Windows (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for analyses.

Ethical and Regulatory Oversight

The study was classified as “not regulated” by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (HUM00078730).

RESULTS

Overall Characteristics of the Study Cohort

Characteristics of Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use

Of the 15,397 PICCs included, we identified 3902 PICCs (25.3%) with a dwell time of ≤5 days (median = 3 days; IQR, 2-4 days). When compared to PICCs that were in place for longer durations, no significant differences in age or comorbidity scores were observed. Importantly, despite recommendations to avoid PICCs in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] ≤ 59 ml/min), 1292 (33.1%) short-term PICCs occurred in patients that met such criteria.

Among short-term PICCs, 3618 (92.7%) were power-capable devices, 2785 (71.4%) were 5-French, and 2813 (72.1%) were multilumen. Indications for the use of short-term PICCs differed from longer term devices in important ways (P < .001). For example, the most common documented indication for short-term PICC use was difficult venous access (28.2%), while for long-term PICCs, it was antibiotic administration (39.8%). General internists and hospitalists were the most common attending physicians for patients with short-term and long-term PICCs (65.1% and 65.5%, respectively [P = .73]). Also, the proportion of critical care physicians responsible for patients with short versus long-term PICC use was similar (14.0% vs 15.0%, respectively [P = .123]). Of the short-term PICCs, 2583 (66.2%) were inserted by vascular access nurses, 795 (20.4%) by interventional radiologists, and 439 (11.3%) by advance practice professionals. Almost all of the PICCs placed ≤5 days (95.5%) were removed during hospitalization.

Complications Associated with Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use

DISCUSSION

This large, multisite prospective cohort study is the first to examine patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use in hospitalized adults. By examining clinically granular data derived from the medical records of patients across 52 hospitals, we found that short-term use was common, representing 25% of all PICCs placed. Almost all such PICCs were removed prior to discharge, suggesting that they were placed primarily to meet acute needs during hospitalization. Multivariable models indicated that patients with difficult venous access, multilumen devices, and teaching hospital settings were associated with short-term use. Given that (a) short term PICC use is not recommended by published evidence-based guidelines,12,13 (b) both major and minor complications were not uncommon despite brief exposure, and (c) specific factors might be targeted to avoid such use, strategies to improve PICC decision-making in the hospital appear increasingly necessary.

In our study, difficult venous access was the most common documented indication for short-term PICC placement. For patients in whom an anticipated catheter dwell time of 5 days or less is expected, MAGIC recommends the consideration of midline or peripheral IV catheters placed under ultrasound guidance.12 A midline is a type of peripheral IV catheter that is about 7.5 cm to 25 cm in length and is typically inserted in the larger diameter veins of the upper extremity, such as the cephalic or basilic veins, with the tip terminating distal to the subclavian vein.7,12 While there is a paucity of information that directly compares PICCs to midlines, some data suggest a lower risk of bloodstream infection and thrombosis associated with the latter.24-26 For example, at one quaternary teaching hospital, house staff who are trained to insert midline catheters under ultrasound guidance in critically ill patients with difficult venous access reported no CLABSI and DVT events.26

Interestingly, multilumen catheters were used twice as often as single lumen catheters in patients with short-term PICCs. In these instances, the use of additional lumens is questionable, as infusion of multiple incompatible fluids was not commonly listed as an indication prompting PICC use. Because multilumen PICCs are associated with higher risks of both VTE and CLABSI compared to single lumen devices, such use represents an important safety concern.27-29 Institutional efforts that not only limit the use of multilumen PICCs but also fundamentally define when use of a PICC is appropriate may substantially improve outcomes related to vascular access.28,30,31We observed that short-term PICCs were more common in teaching compared to nonteaching hospitals. While the design of the present study precludes understanding the reasons for such a difference, some plausible theories include the presence of physician trainees who may not appreciate the risks of PICC use, diminishing peripheral IV access securement skills, and the lack of alternatives to PICC use. Educating trainees who most often order PICCs in teaching settings as to when they should or should not consider this device may represent an important quality improvement opportunity.32 Similarly, auditing and assessing the clinical skills of those entrusted to place peripheral IVs might prove helpful.33,34 Finally, the introduction of a midline program, or similar programs that expand the scope of vascular access teams to place alternative devices, should be explored as a means to improve PICC use and patient safety.

Our study also found that a third of patients who received PICCs for 5 or fewer days had moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. In these patients who may require renal replacement therapy, prior PICC placement is among the strongest predictors of arteriovenous fistula failure.35,36 Therefore, even though national guidelines discourage the use of PICCs in these patients and recommend alternative routes of venous access,12,37,38 such practice is clearly not happening. System-based interventions that begin by identifying patients who require vein preservation (eg, those with a GFR < 45 ml/min) and are therefore not appropriate for a PICC would be a welcomed first step in improving care for such patients.37,38Our study has limitations. First, the observational nature of the study limits the ability to assess for causality or to account for the effects of unmeasured confounders. Second, while the use of medical records to collect granular data is valuable, differences in documentation patterns within and across hospitals, including patterns of missing data, may produce a misclassification of covariates or outcomes. Third, while we found that higher rates of short-term PICC use were associated with teaching hospitals and patients with difficult venous access, we were unable to determine the precise reasons for this practice trend. Qualitative or mixed-methods approaches to understand provider decision-making in these settings would be welcomed.

Our study also has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically describe and evaluate patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use. The finding that PICCs placed for difficult venous access is a dominant category of short-term placement confirms clinical suspicions regarding inappropriate use and strengthens the need for pathways or protocols to manage such patients. Second, the inclusion of medical patients in diverse institutions offers not only real-world insights related to PICC use, but also offers findings that should be generalizable to other hospitals and health systems. Third, the use of a robust data collection strategy that emphasized standardized data collection, dedicated trained abstractors, and random audits to ensure data quality strengthen the findings of this work. Finally, our findings highlight an urgent need to develop policies related to PICC use, including limiting the use of multiple lumens and avoidance in patients with moderate to severe kidney disease.

In conclusion, short-term use of PICCs is prevalent and associated with key patient, provider, and device factors. Such use is also associated with complications, such as catheter occlusion, tip migration, VTE, and CLABSI. Limiting the use of multiple-lumen PICCs, enhancing education for when a PICC should be used, and defining strategies for patients with difficult access may help reduce inappropriate PICC use and improve patient safety. Future studies to examine implementation of such interventions would be welcomed.

Disclosure: Drs. Paje, Conlon, Swaminathan, and Boldenow disclose no conflicts of interest. Dr. Chopra has received honoraria for talks at hospitals as a visiting professor. Dr. Flanders discloses consultancies for the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the Society of Hospital Medicine, royalties from Wiley Publishing, honoraria for various talks at hospitals as a visiting professor, grants from the CDC Foundation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM), and Michigan Hospital Association, and expert witness testimony. Dr. Bernstein discloses consultancies for Blue Care Network and grants from BCBSM, Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kaatz discloses no relevant conflicts of interest. BCBSM and Blue Care Network provided support for the Michigan HMS Consortium as part of the BCBSM Value Partnerships program. Although BCBSM and HMS work collaboratively, the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints of BCBSM or any of its employees. Dr. Chopra is supported by a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1-K08-HS022835-01). BCBSM and Blue Care Network supported data collection at each participating site and funded the data coordinating center but had no role in study concept, interpretation of findings, or in the preparation, final approval, or decision to submit the manuscript.

1. Al Raiy B, Fakih MG, Bryan-Nomides N, et al. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters in the acute care setting: A safe alternative to high-risk short-term central venous catheters. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(2):149-153. PubMed

2. Gibson C, Connolly BL, Moineddin R, Mahant S, Filipescu D, Amaral JG. Peripherally inserted central catheters: use at a tertiary care pediatric center. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(9):1323-1331. PubMed

3. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S. The problem with peripherally inserted central catheters. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1527-1528. PubMed

4. Chopra V, Smith S, Swaminathan L, et al. Variations in Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use and Outcomes in Michigan Hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):548-551. PubMed

5. Cowl CT, Weinstock JV, Al-Jurf A, Ephgrave K, Murray JA, Dillon K. Complications and cost associated with parenteral nutrition delivered to hospitalized patients through either subclavian or peripherally-inserted central catheters. Clin Nutr. 2000;19(4):237-243. PubMed

6. MacDonald AS, Master SK, Moffitt EA. A comparative study of peripherally inserted silicone catheters for parenteral nutrition. Can J Anaesth. 1977;24(2):263-269. PubMed

7. Chopra V, O’Horo JC, Rogers MA, Maki DG, Safdar N. The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(9):908-918. PubMed

8. Chopra V, Anand S, Hickner A, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):311-325. PubMed

9. Beccaria P, Silvetti S, Mucci M, Battini I, Brambilla P, Zangrillo A. Contributing factors for a late spontaneous peripherally inserted central catheter migration: a case report and review of literature. J Vasc Access. 2015;16(3):178-182. PubMed

10. Turcotte S, Dube S, Beauchamp G. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters are not superior to central venous catheters in the acute care of surgical patients on the ward. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1605-1619. PubMed

11. Pikwer A, Akeson J, Lindgren S. Complications associated with peripheral or central routes for central venous cannulation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(1):65-71. PubMed

12. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results From a Multispecialty Panel Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Intern Med. 15 2015;163(6 Suppl):S1-S40. PubMed

13. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(4 Suppl 1):S1-S34. PubMed

14. Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium. 2016; http://mi-hms.org/. Accessed November 11, 2016.

15. Greene MT, Spyropoulos AC, Chopra V, et al. Validation of Risk Assessment Models of Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Medical Patients. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):1001.e1009-1001.e1018. PubMed

16. Greene MT, Flanders SA, Woller SC, Bernstein SJ, Chopra V. The Association Between PICC Use and Venous Thromboembolism in Upper and Lower Extremities. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):986-993. PubMed

17. Flanders SA, Greene MT, Grant P, et al. Hospital performance for pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and rate of venous thromboembolism : a cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1577-1584. PubMed

18. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619. PubMed

19. Hospital Bed Inventory. 2016; http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/HOSPBEDINV_October_3__2016_536834_7.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2016.

20. Compare Hospitals. 2016; http://www.leapfroggroup.org/compare-hospitals. Accessed November 22, 2016.

21. NHSN Patient Safety Component Manual. 2016; http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/pcsmanual_current.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2016.

22. Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1-45. PubMed

23. Austin PC, Tu JV. Bootstrap Methods for Developing Predictive Models. Am Stat. 2004;58(2):131-137.

24. Pathak R, Patel A, Enuh H, Adekunle O, Shrisgantharajah V, Diaz K. The Incidence of Central Line-Associated Bacteremia After the Introduction of Midline Catheters in a Ventilator Unit Population. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2015;23(3):131-134. PubMed

25. Adams DZ, Little A, Vinsant C, Khandelwal S. The Midline Catheter: A Clinical Review. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(3):252-258. PubMed

26. Deutsch GB, Sathyanarayana SA, Singh N, Nicastro J. Ultrasound-guided placement of midline catheters in the surgical intensive care unit: a cost-effective proposal for timely central line removal. J Surg Res. 2014;191(1):1-5. PubMed

27. Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream Infection, Venous Thrombosis, and Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters: Reappraising the Evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):733-741. PubMed

28. Ratz D, Hofer T, Flanders SA, Saint S, Chopra V. Limiting the Number of Lumens in Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters to Improve Outcomes and Reduce Cost: A Simulation Study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(7):811-817. PubMed

29. Pongruangporn M, Ajenjo MC, Russo AJ, et al. Patient- and device-specific risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(2):184-189. PubMed

30. Shannon RP, Patel B, Cummins D, Shannon AH, Ganguli G, Lu Y. Economics of central line--associated bloodstream infections. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(6 Suppl):7S-16S. PubMed

31. O’Brien J, Paquet F, Lindsay R, Valenti D. Insertion of PICCs with minimum number of lumens reduces complications and costs. J AmColl Radiol. 2013;10(11):864-868. PubMed

32. Wong BM, Etchells EE, Kuper A, Levinson W, Shojania KG. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1425-1439. PubMed

33. Conlon T, Himebauch A, Marie Cahill A, et al. 1246: Bedside Picc Placement by Pediatric Icu Providers Is Feasible and Safe. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12 Suppl 1):387.

34. Moran J, Colbert CY, Song J, et al. Screening for novel risk factors related to peripherally inserted central catheter-associated complications. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(8):481-489. PubMed

35. Gonsalves CF, Eschelman DJ, Sullivan KL, DuBois N, Bonn J. Incidence of central vein stenosis and occlusion following upper extremity PICC and port placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26(2):123-127. PubMed

36. El Ters M, Schears GJ, Taler SJ, et al. Association between prior peripherally inserted central catheters and lack of functioning arteriovenous fistulas: a case-control study in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(4):601-608. PubMed

37. Vascular Access 2006 Work Group. Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48 Suppl 1:S248-S273. PubMed

38. Hoggard J, Saad T, Schon D, et al. Guidelines for venous access in patients with chronic kidney disease. A Position Statement from the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology, Clinical Practice Committee and the Association for Vascular Access. Semin Dial. 2008;21(2):186-191. PubMed

1. Al Raiy B, Fakih MG, Bryan-Nomides N, et al. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters in the acute care setting: A safe alternative to high-risk short-term central venous catheters. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(2):149-153. PubMed

2. Gibson C, Connolly BL, Moineddin R, Mahant S, Filipescu D, Amaral JG. Peripherally inserted central catheters: use at a tertiary care pediatric center. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(9):1323-1331. PubMed

3. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S. The problem with peripherally inserted central catheters. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1527-1528. PubMed

4. Chopra V, Smith S, Swaminathan L, et al. Variations in Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use and Outcomes in Michigan Hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):548-551. PubMed

5. Cowl CT, Weinstock JV, Al-Jurf A, Ephgrave K, Murray JA, Dillon K. Complications and cost associated with parenteral nutrition delivered to hospitalized patients through either subclavian or peripherally-inserted central catheters. Clin Nutr. 2000;19(4):237-243. PubMed

6. MacDonald AS, Master SK, Moffitt EA. A comparative study of peripherally inserted silicone catheters for parenteral nutrition. Can J Anaesth. 1977;24(2):263-269. PubMed

7. Chopra V, O’Horo JC, Rogers MA, Maki DG, Safdar N. The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(9):908-918. PubMed

8. Chopra V, Anand S, Hickner A, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):311-325. PubMed

9. Beccaria P, Silvetti S, Mucci M, Battini I, Brambilla P, Zangrillo A. Contributing factors for a late spontaneous peripherally inserted central catheter migration: a case report and review of literature. J Vasc Access. 2015;16(3):178-182. PubMed

10. Turcotte S, Dube S, Beauchamp G. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters are not superior to central venous catheters in the acute care of surgical patients on the ward. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1605-1619. PubMed

11. Pikwer A, Akeson J, Lindgren S. Complications associated with peripheral or central routes for central venous cannulation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(1):65-71. PubMed

12. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results From a Multispecialty Panel Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Intern Med. 15 2015;163(6 Suppl):S1-S40. PubMed

13. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(4 Suppl 1):S1-S34. PubMed

14. Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium. 2016; http://mi-hms.org/. Accessed November 11, 2016.

15. Greene MT, Spyropoulos AC, Chopra V, et al. Validation of Risk Assessment Models of Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Medical Patients. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):1001.e1009-1001.e1018. PubMed

16. Greene MT, Flanders SA, Woller SC, Bernstein SJ, Chopra V. The Association Between PICC Use and Venous Thromboembolism in Upper and Lower Extremities. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):986-993. PubMed

17. Flanders SA, Greene MT, Grant P, et al. Hospital performance for pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and rate of venous thromboembolism : a cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1577-1584. PubMed

18. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619. PubMed

19. Hospital Bed Inventory. 2016; http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/HOSPBEDINV_October_3__2016_536834_7.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2016.

20. Compare Hospitals. 2016; http://www.leapfroggroup.org/compare-hospitals. Accessed November 22, 2016.

21. NHSN Patient Safety Component Manual. 2016; http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/pcsmanual_current.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2016.

22. Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1-45. PubMed

23. Austin PC, Tu JV. Bootstrap Methods for Developing Predictive Models. Am Stat. 2004;58(2):131-137.

24. Pathak R, Patel A, Enuh H, Adekunle O, Shrisgantharajah V, Diaz K. The Incidence of Central Line-Associated Bacteremia After the Introduction of Midline Catheters in a Ventilator Unit Population. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2015;23(3):131-134. PubMed

25. Adams DZ, Little A, Vinsant C, Khandelwal S. The Midline Catheter: A Clinical Review. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(3):252-258. PubMed

26. Deutsch GB, Sathyanarayana SA, Singh N, Nicastro J. Ultrasound-guided placement of midline catheters in the surgical intensive care unit: a cost-effective proposal for timely central line removal. J Surg Res. 2014;191(1):1-5. PubMed

27. Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream Infection, Venous Thrombosis, and Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters: Reappraising the Evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):733-741. PubMed

28. Ratz D, Hofer T, Flanders SA, Saint S, Chopra V. Limiting the Number of Lumens in Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters to Improve Outcomes and Reduce Cost: A Simulation Study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(7):811-817. PubMed

29. Pongruangporn M, Ajenjo MC, Russo AJ, et al. Patient- and device-specific risk factors for peripherally inserted central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(2):184-189. PubMed

30. Shannon RP, Patel B, Cummins D, Shannon AH, Ganguli G, Lu Y. Economics of central line--associated bloodstream infections. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(6 Suppl):7S-16S. PubMed

31. O’Brien J, Paquet F, Lindsay R, Valenti D. Insertion of PICCs with minimum number of lumens reduces complications and costs. J AmColl Radiol. 2013;10(11):864-868. PubMed

32. Wong BM, Etchells EE, Kuper A, Levinson W, Shojania KG. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1425-1439. PubMed

33. Conlon T, Himebauch A, Marie Cahill A, et al. 1246: Bedside Picc Placement by Pediatric Icu Providers Is Feasible and Safe. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12 Suppl 1):387.

34. Moran J, Colbert CY, Song J, et al. Screening for novel risk factors related to peripherally inserted central catheter-associated complications. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(8):481-489. PubMed

35. Gonsalves CF, Eschelman DJ, Sullivan KL, DuBois N, Bonn J. Incidence of central vein stenosis and occlusion following upper extremity PICC and port placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26(2):123-127. PubMed

36. El Ters M, Schears GJ, Taler SJ, et al. Association between prior peripherally inserted central catheters and lack of functioning arteriovenous fistulas: a case-control study in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(4):601-608. PubMed

37. Vascular Access 2006 Work Group. Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48 Suppl 1:S248-S273. PubMed

38. Hoggard J, Saad T, Schon D, et al. Guidelines for venous access in patients with chronic kidney disease. A Position Statement from the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology, Clinical Practice Committee and the Association for Vascular Access. Semin Dial. 2008;21(2):186-191. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Perception of Resources Spent on Defensive Medicine and History of Being Sued Among Hospitalists: Results from a National Survey

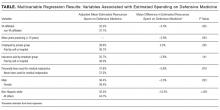

Annual healthcare costs in the United States are over $3 trillion and are garnering significant national attention.1 The United States spends approximately 2.5 times more per capita on healthcare when compared to other developed nations.2 One source of unnecessary cost in healthcare is defensive medicine. Defensive medicine has been defined by Congress as occurring “when doctors order tests, procedures, or visits, or avoid certain high-risk patients or procedures, primarily (but not necessarily) because of concern about malpractice liability.”3

Though difficult to assess, in 1 study, defensive medicine was estimated to cost $45 billion annually.4 While general agreement exists that physicians practice defensive medicine, the extent of defensive practices and the subsequent impact on healthcare costs remain unclear. This is especially true for a group of clinicians that is rapidly increasing in number: hospitalists. Currently, there are more than 50,000 hospitalists in the United States,5 yet the prevalence of defensive medicine in this relatively new specialty is unknown. Inpatient care is complex and time constraints can impede establishing an optimal therapeutic relationship with the patient, potentially raising liability fears. We therefore sought to quantify hospitalist physician estimates of the cost of defensive medicine and assess correlates of their estimates. As being sued might spur defensive behaviors, we also assessed how many hospitalists reported being sued and whether this was associated with their estimates of defensive medicine.

METHODS

Survey Questionnaire

In a previously published survey-based analysis, we reported on physician practice and overuse for 2 common scenarios in hospital medicine: preoperative evaluation and management of uncomplicated syncope.6 After responding to the vignettes, each physician was asked to provide demographic and employment information and malpractice history. In addition, they were asked the following: In your best estimation, what percentage of healthcare-related resources (eg, hospital admissions, diagnostic testing, treatment) are spent purely because of defensive medicine concerns? __________% resources

Survey Sample & Administration

The survey was sent to a sample of 1753 hospitalists, randomly identified through the Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM) database of members and annual meeting attendees. It is estimated that almost 30% of practicing hospitalists in the United States are members of the SHM.5 A full description of the sampling methodology was previously published.6 Selected hospitalists were mailed surveys, a $20 financial incentive, and subsequent reminders between June and October 2011.

The study was exempted from institutional review board review by the University of Michigan and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

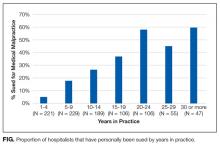

Variables