User login

It's Not About Pager Replacement

Clinical communication among healthcare providers to coordinate patient care is important, accounting for the majority of information exchanges in healthcare.[1, 2] Breakdowns in communication have therefore been identified as the major contributor to medical errors.[3, 4, 5]

There is a growing literature related to asynchronous clinical communication practices, or communication that does not occur at the same time in hospitals, and the limitations of using the traditional numeric pager. These include the inability to indicate the urgency of the message, frequent interruptions, contacting the wrong physician, and inefficiencies coordinating care across multiple disciplines and specialties.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

Hospitals have implemented a variety of health information technology (HIT) solutions to replace the numeric pager and address these clinical communication issues, including the use of alphanumeric pagers, smartphone devices, and Web‐based applications that allow clinicians to triage the urgency of issues.[13, 14, 15, 16] Although these solutions have resolved some of the deficiencies previously identified, issues relating to the impact on the interprofessional nature of healthcare remain unaddressed.[17] In some cases, the implementation of HIT has created unintended consequences that have an impact on effective communication.

One of the widely cited examples of HIT creating unintended consequences is the implementation of computerized physician order entry systems.[18, 19, 20] Other studies looking more broadly at patient information systems have identified problems caused by poor user interfaces that promoted errors in entry and retrieval of data, inflexible features forcing clinician workarounds, and technology designs that impeded clinical workflow.[21, 22, 23]

These observations suggest that although many of the issues with clinical communication stem from the reliance on numeric paging, simply replacing pagers with newer technology may not solve the problems and can in fact create other unintended consequences. These include unintended consequences resulting from the sociotechnical aspects of HIT, which is the interplay of technology with existing clinical workflow, culture, and social interactions.[21] Our institution recently implemented a Web‐based messaging system to replace the use of numeric pagers. We aimed to evaluate the unintended consequences resulting from the implementation of this system and to describe their impact on the delivery of clinical care on a general internal medicine (GIM) service.

METHODS

This was a pre‐post mixed‐methods study utilizing both quantitative and qualitative measures. We integrated these 2 data‐collection methods to improve the quality of the results. The study was conducted on the GIM service at the University Health Network Toronto Western Hospital site, a tertiary‐care academic teaching center fully affiliated with the University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada). The GIM service at Toronto Western Hospital consists of 4 clinical teams, each staffed by an attending physician, 3 to 4 residents, and 2 to 3 medical students.

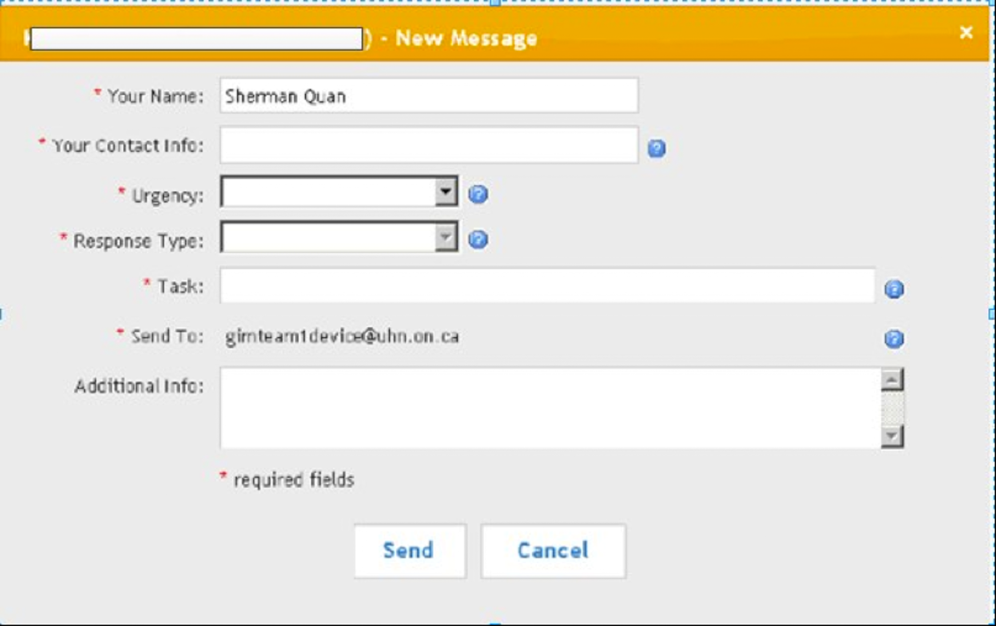

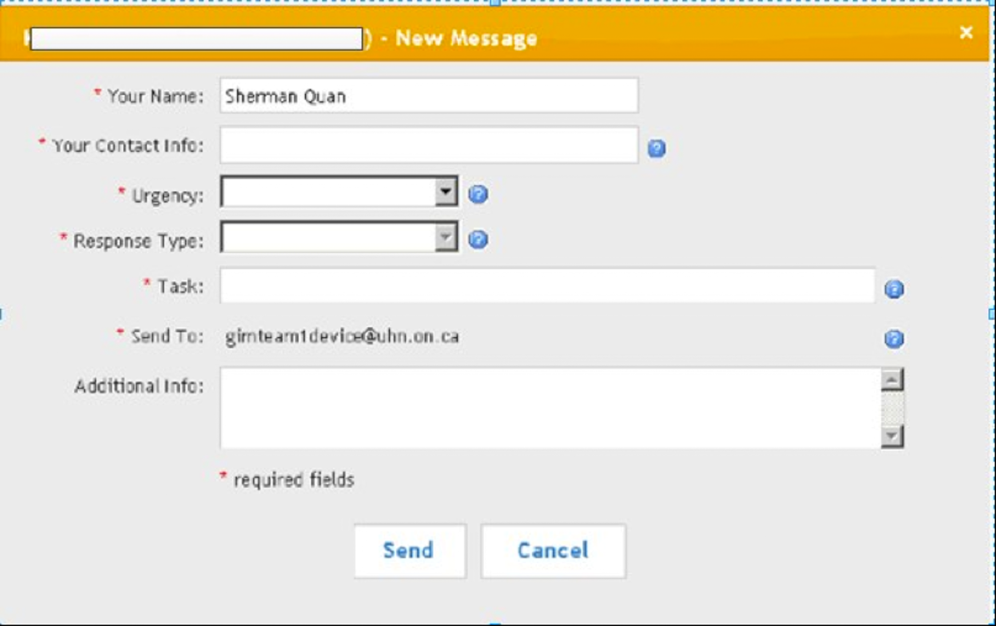

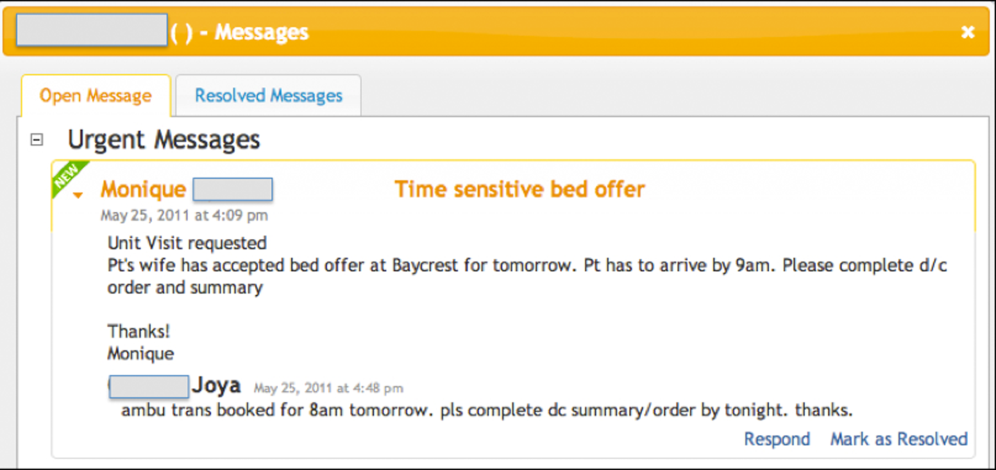

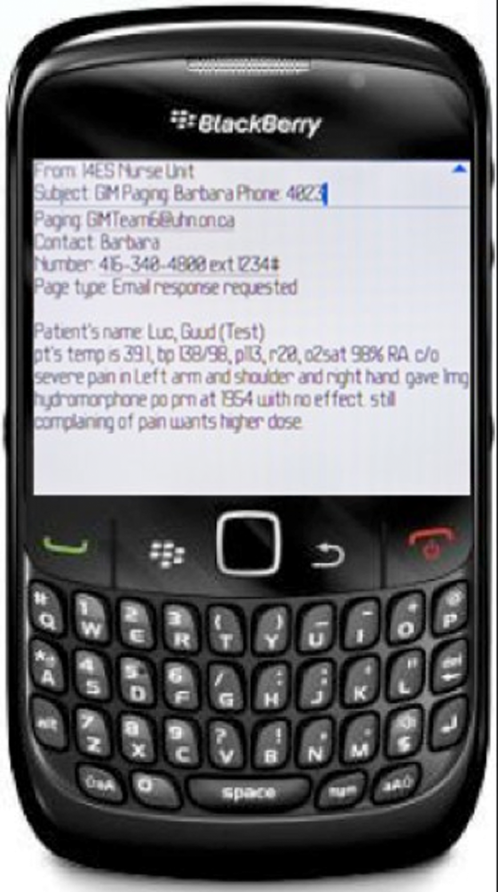

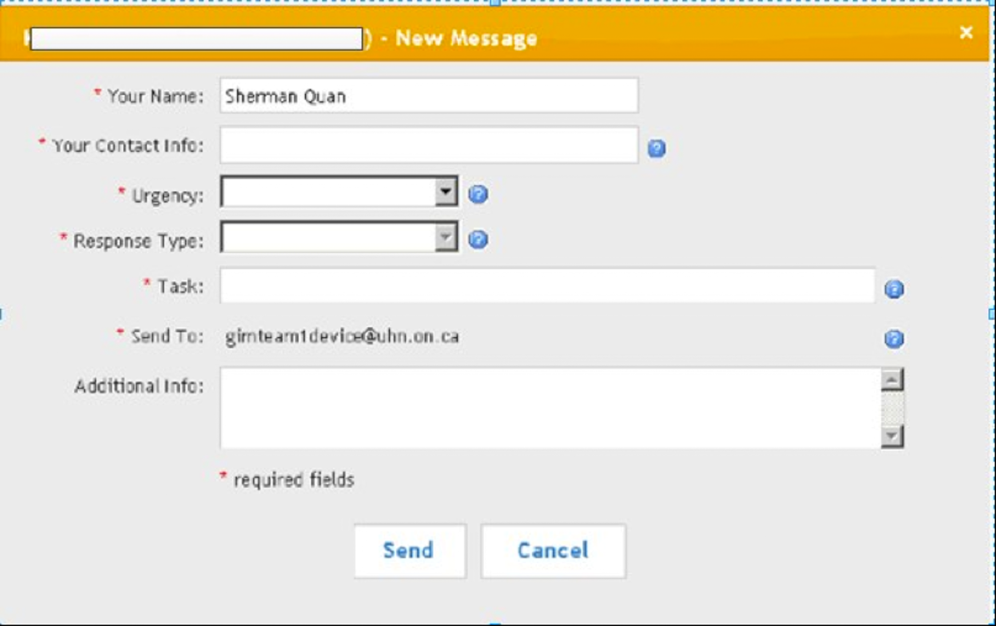

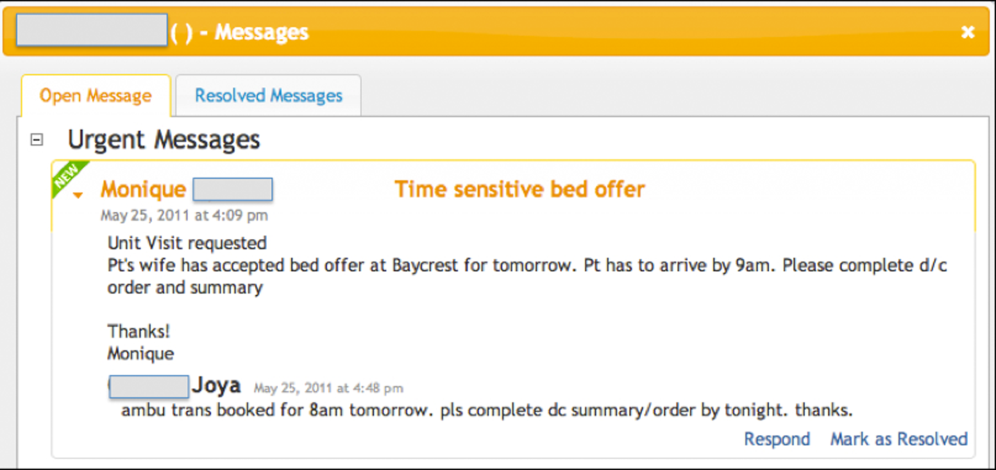

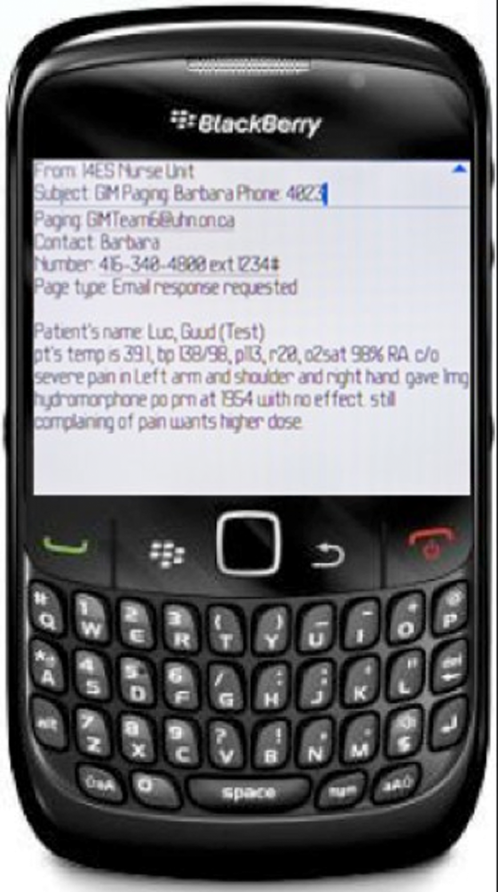

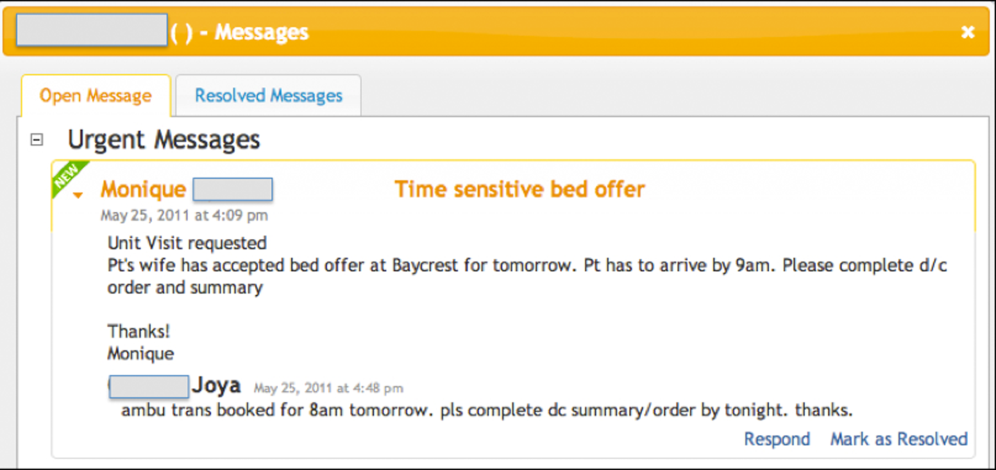

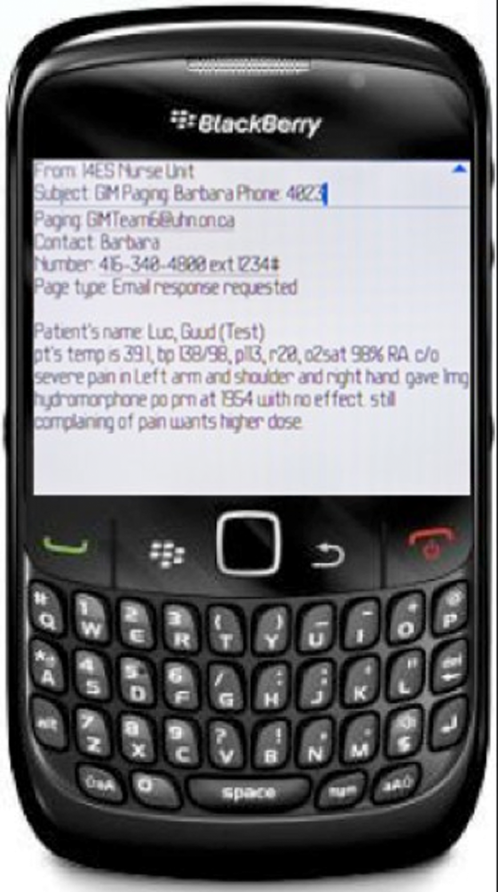

Prior to this study, nonface‐to‐face communication on the wards was facilitated through numeric paging, where nurses, pharmacists, and social workers on the GIM wards would page residents to a hospital phone and wait for them to call back. Figures 1, 2, and 3 visualize the Web‐based messaging system we implemented at the University Health Network in May 2010. All residents on the service were provided smartphones that they used for communication. In addition to these, there was a dedicated team smartphone that acted as a central point of contact for the team 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and was carried by the physician covering the team at the time. The system allowed nurses, pharmacists, and social workers to triage the urgency of messages and include details providing context to the issue. Issues flagged as urgent were immediately sent to the team smartphone by e‐mail to alert the physician, who could respond from the smartphone. These messages could be forwarded to a team member, often the physician most familiar with the patient, to address. Issues flagged as nonurgent were posted to the system's message board, which the physicians accessed by logging into the Web‐based messaging system on a regular basis. The message board was designed to allow physicians to respond to multiple non‐urgent issues at once. To close the loop on communication, logic was developed so that if a physician did not respond to a non‐urgent message within the specified timeframe, the message was escalated and sent as an alerting e‐mail to the team smartphone every 15 minutes until it was addressed. The timeframes for responding varied from 1 hour to not needing a response until the next morning.

Ongoing training on the use of the system was built into the clinical orientation for the physician and nursing staff, as turnover in an academic teaching hospital is quite high. The orientation included instructions on how to use the features of the Web‐based messaging system but also provided guidelines on general etiquette with using the system to ensure sustainability of the communication process. For example, physicians were asked to check the system regularly, as the process worked only if they responded to messages. Nurses were asked not to send messages during scheduled educational sessions unless necessary and to limit messages they flagged as urgent to ones that were in fact urgent.

Our quantitative evaluation compared interruptions, which we define as communication that caused a medical resident to stop current activity to address, before and after the implementation of the Web‐based messaging system to assess the volume and time distribution of messages, and compared these results with our qualitative evaluation. For the pre‐implementation phase, interruptions were all numeric pages sent to all residents during the period of July 1427, 2008. For the post‐implementation phase, interruptions were the e‐mails sent directly to the team smartphones from the Web‐based messaging system to all residents during the period of October 1124, 2010. We excluded messages from the postimplementation phase if the same message was sent >10 times, typically indicating technical issues such as a malfunction of the smartphone causing the escalation process to continue.

Our qualitative evaluation consisted of semistructured interviews that were conducted after implementation. A research coordinator sent e‐mails to potential physician participants during a 1‐month rotation (n=16), and nurses (N=50), pharmacists (N=4), and social workers (N=4) from a representative ward inviting them to be part of this study. A set of open‐ended questions (see Supporting Information, Appendix A, in the online version of this article) developed based on informal feedback regarding the system provided by physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers served as a guide to highlight key themes of interest. Based on the participants' responses, further questions were asked to drill down into more detail. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymized.

The interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis to generate categories and overarching themes.[24, 25] Once the coding structure was developed, the transcripts were imported into qualitative analysis software (NVivo 9, QSR International) and then coded and analyzed, pulling the key themes that emerged from the text to be used in interpreting the data.

RESULTS

Our quantitative before‐after comparison of clinical messages sent to physicians revealed an increase in interruptions. We compared these results to the results of our interviews to understand why this might have occurred. Several key themes emerged from the analysis of the interviews, including increase in interruptions, accountability, and tactics to improve personal productivity. We interviewed 5 physicians, 8 nurses, 2 pharmacists, and 2 social workers.

Pre‐Post System Usage Data: Quantitative Assessment

Table 1 outlines the number of numeric pages sent during the pre‐implementation phase of July 1427, 2008. All pages sent immediately alerted the resident and so were all considered interruptions. Table 1 also outlines the number of urgent and escalation messages sent via e‐mail to the residents during the post‐implementation phase of October 1124, 2010. All messages were sent immediately to the team smartphone alerting the resident and so were all considered interruptions. During both timeframes, there were 15 resident physicians on service. During the pre‐implementation phase, 117 patients were admitted to the GIM service, and 162 patients were admitted during the post‐implementation phase.

| Numeric Paging (Predata) | Advance Communication System (Postdata) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pages sent | 710 | Urgent | 951 |

| Interruptions | 710 | Escalations | 1245 |

| Interruptions per resident per day | 3 | Interruptions | 2196 |

| Interruptions per resident per day | 10 | ||

Table 1 shows that the number of interruptions in the pre‐implementation phase was 710 (3 per resident per day) compared with 2196 (10 per resident per day) in the post‐implementation phase, a 233% increase in interruptions. Because admissions were higher in the post‐implementation phase, it is possible that higher patient volumes could have contributed to the increase in interruptions.

Semi‐Structured Interviews: Qualitative Assessment

Increase in Interruptions

The intent of the web‐based messaging system was to reduce interruptions by triaging clinical messages and allowing healthcare professionals to respond to multiple non‐urgent issues at once. The unexpected result, however, was that the frequency at which physicians were interrupted actually increased following implementation.

I feel like I'm constantly bombarded with things Just psychologically I feel like it's harassing me a lot more than the pager used to. [MD02, physician]

Yes. Definitely, I'm paging them more frequently in general than I would have previously. [RN02, nurse]

Increased interruptions occurred in part because traditional barriers to paging, like having to wait by a phone for a response, were eliminated by the new system. Sending a message was easy, and with the reliability introduced through team‐based paging, there was greater temptation to send separate messages for singular issues.

I think [that] before, things were saved up and then paged and given all at once. And now it's, like, there's a temptation just to send things all the time, like, small issues. [AH01, pharmacist]

Communication also increased due to the impersonal nature of the electronic system. With many of the barriers to communicating removed, such as receiving immediate feedback regarding the appropriateness of a message, staff no longer hesitated when sending messages regarding less‐important issues.

So some stuff that you may have not wanted to call for before 'cause it's kind of silly, you can just send it information‐only. So they're aware 'cause the thing about with using electronics it's a lot more impersonal and indirect. [RN03, nurse]

At the same time, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers acknowledged that receiving all of this additional, sometimes unnecessary, information could be frustrating for the physicians. This recognition alone, however, was not sufficient to modify their behavior.

So I find that I can imagine for them it may be a little frustrating 'cause they're getting all these tidbits of information. [RN03, nurse]

I'm sure they get overwhelmed and I've had the feedback from the team They were saying that they were getting constantly paged, not by me, just by me, but by everybody. [AH01, pharmacist]

Accountability

As part of their professional practice, nurses described a medico‐legal obligation to inform physicians about relevant patient issues such as abnormal laboratory values. A culture of accountability, therefore, underpinned many of the actions taken by the nurses, reinforced because the electronic messages sent through the system were permanent and retrievable. The physicians also used the system as an electronic record of discussions that occurred.

Because it's just, like, this thing about accountability in terms of letting them know, that they are aware. [RN03, nurse]

And I think everything you do is recorded, like, you can go back and check, so there's that legal piece, which I guess covers you, in terms of time you called, those things which are critical, what you are calling for. [RN09, nurse]

'Cause I use it now as a reference. So even if I have a phone conversation with a nurse, based on a message that we've had, I will record what we said and send it. [MD03, physician]

Some of the more junior nurses periodically felt unsure or uncomfortable with clinical situations and would send a message to the physician to share their concerns. The messaging reassured the nurses and made them feel like they were fulfilling their professional responsibilities.

So a senior nurse could probably take a look at some situation and they can acknowledge whether the issue is urgent or nonurgent But from a novice perspective, as you're still learning it kind of gives you peace of mind and feels like you're filling your responsibility and accountability, that you're passing on the messages. [RN03, nurse]

Whereas nurses felt they were fulfilling their professional obligations, some physicians felt that nurses were using the system to absolve themselves of their clinical responsibilities.

Some just feel the need to send everything on there and maybe they feel that by sending it on here they absolve themselves of responsibility. [MD05, physician]

Other clinicians felt that the system created more of a responsibility or obligation for the physicians to respond. They believed the escalation feature of the system helped ensure the physicians responded in some fashion to close the loop.

[T]hey have the responsibility to answer it if it's an urgent message and because it keeps coming on to remind them. [AH02, social worker]

Interestingly, there were physicians that identified the opposite and felt the system created less of a responsibility or obligation for them to respond. By knowing the context of the message, it gave them the ability to prioritize or ignore the message if they knew it was not life threatening.

[T]here's less of a responsibility or an obligation They get a message and then they can actually delay the process So in a way it actually allows us to kind of get away with some things and that happens because, you know, we're prioritizing something that we're doing as being more important to us. [MD01, physician]

Tactics to Improve Personal Productivity

The web‐based messaging system's triaging feature allows the sender of the message to indicate whether an issue is urgent or non‐urgent. Urgent issues result in an immediate e‐mail that is intended to elicit an immediate response. Some of the nurses, pharmacists, and social workers exploited features of the system to elicit immediate responses from the physicians for non‐urgent issues, including using their knowledge of the urgent and non‐urgent features of the system to interrupt the physicians.

I kind of cheat and don't use the system properly. So every message I send I always send it as urgent because I want it go to the smartphone. [AH01, pharmacist]

I like that if you know how to use the urgent and nonurgent features effectively it generally works quite well in getting a response in a timely fashion. [RN02, nurse]

One tactic that physicians perceived the nurses were using to elicit a response from them was to exaggerate the severity or urgency of the issue in their message.

Some details will be sort of cherry picked to make the issue sound very dire I'll give you a classic, like, high blood pressure and patient has a headache. So initially, you know, I have to think, does this patient have a hypertensive emergency? So by putting sort of history together in this way, that sort of suggestive way, then yeah. [MD03, physician]

The nurses, pharmacists. and social workers frequently exaggerated the urgency of their clinical messages at the end of their shifts in an effort to resolve outstanding issues immediately in order to avoid transferring tasks to another colleague or delaying them until the next day.

But in terms of a shift change, for example, I need a response now 'cause that is a lot of times where it is that although it's not clinically urgent it's time sensitive. So it is urgent. [RN02, nurse]

I do also notice that around changeover time, issues that have been sort of chronically or have preexisting, become urgent issues. [MD01, physician]

Messages were also sent inappropriately as urgent as a strategy to ensure the physician dealt with the issue promptly and did not forget to complete the requested task associated with the issue.

Everybody puts urgent because we want the response immediately. Otherwise, if you put nonurgent, the doctors will just drag and drag and will forget to respond to the issue. [RN09, nurse]

However, because physicians received context clarifying the urgency of the message, they were able to prioritize their tasks and defer less‐important issues without compromising patient safety or quality of care, allowing them to use their time more productively. This, however, did not always align with the sender's request.

I think the key thing is that the information coming to us is text and it describes the issue. So we can, at our end, then we can make a call as to what the priority is. [MD03, physician]

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate a Web‐based messaging system and identify the unintended consequences observed with implementing HIT to improve clinical communication. This is an important study because healthcare organizations are beginning to develop strategies for improving clinical communication but believe the solution involves simply replacing pager technology. Support for this approach is seen with larger vendors in the smartphone and communication industry, who promote their products as pager‐replacement solutions and even help customers develop pager‐replacement strategies.[26, 27, 28] Simply replacing pagers with smartphones and sending text messages will have only a limited impact on improving clinical communication and will likely result in unintended negative consequences, as seen in this study.

Whereas the Web‐based messaging system was designed to reduce interruptions from clinical messaging, interruptions actually increased, although the mental burden of each interruption was likely lower because responding to a text message is less interruptive than finding a telephone to answer a page. A key contributor to this effect was a culture of accountability among nurses, pharmacists, and social workers who felt it was their professional obligation to notify physicians about all issues of concern. This belief and related behavior is aligned with the standards promoted by professional regulatory bodies that identify accountability as a vital practice expectation.[29] Nurses and nursing staff take responsibility for the care they provide and answer for their own judgments and actions.[30] The system eliminated many of the previous barriers to paging and provided a less‐personal form of communication. The cumulative and unexpected outcome was an increase of interruptions for physicians and the adoption of workarounds by all healthcare professionals to improve personal productivity. Although the system was built in an iterative fashion with frontline clinicians, it is likely that oversights in the design of the system also contributed to these problems, which speaks to the complexity of clinical communication. Centralizing communication to the team smartphone could have overburdened the physicians covering it at the time, causing them to ignore messages because they were too busy to address them.

There were limitations to this study. One limitation was that this study examined only a cross‐section of messaging activity at a given point in time, and therefore it may not be representative of the behaviors of the physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers over time as the culture of the environment evolves and they adjust to the new technology. The pre‐implementation data were collected 2 years prior to the post‐implementation data, but it was necessary to use data this old because other interventions were implemented prior to the Web‐based messaging system, so baseline paging data were no longer available. Whereas most clinical disciplines were represented in the interviews, the sample included only 17 participants from 1 clinical service, so generalizability of the results may be limited.

Although the reliance on numeric paging technology was previously identified as a primary source of problems with communication, the real issues are much more complex. This study highlighted that many of the underlying obstacles relate to existing social interactions and habits of multiple professions working together. Failures in collaboration among healthcare professionals have a negative impact on health outcomes and routinely stem from the lack of explicit definitions of roles, the absence of clear leadership, insufficient time for team‐building, the us‐and‐them effects created by professional socialization, and frustration created by power and status differentials of each discipline.[31, 32, 33] Therefore, it is critical that healthcare organizations focus on the people and clinical processes when implementing technology to solve issues with clinical communication. These observations are consistent with other studies examining the unintended consequences caused by the sociotechnical aspects of HIT implementation, where workarounds to game the system were also employed.[21]

In summary, improving clinical communication cannot be achieved simply by replacing pagers with newer technology; it requires a fundamental shift in how healthcare professionals interact, with a focus on the sociotechnical aspects of HIT. As patient volumes and the complexity of care continue to increase, more effective methods for facilitating interprofessional communication and collaboration must be developed.

Acknowledgements

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- . When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277–286.

- , , , et al. Synchronous communication facilitates interruptive workflow for attending physicians and nurses in clinical settings. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(9):629–637.

- , , , et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):377–384.

- , , . Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186–194.

- The Joint Commission. Improving America's Hospitals: The Joint Commission's Annual Report on Quality and Safety. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2007. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2007_Annual_Report.pdf. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- , . Residents' suggestions for reducing errors in teaching hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(9):851–855.

- , . Interruptions in healthcare: theoretical views. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(5):293–307.

- , , , et al. Frequency and clinical importance of pages sent to the wrong physician. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(11):1072–1073.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–407.

- , , , , , . Towards safer interprofessional communication: Constructing a model of “utility” from preoperative team briefings. J Interprof Care. 2006;20(5):471–483.

- , , . Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice‐based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD000072.

- , . The effects of hands free communication devices on clinical communication: balancing communication access needs with user control. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008;621–625.

- , , , , . Beyond paging: building a web‐based communication tool for nurses and physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):105–110.

- , , , et al. The use of smartphones for clinical communication on internal medicine wards. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):553–559.

- , , , . Implementation and evaluation of an alpha‐numeric paging system on a resident inpatient teaching service. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):E34–E40.

- , , , et al. Effects of clinical communication interventions in hospitals: a systematic review of information and communication technology adoptions for improved communication between clinicians. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(11):723–732.

- , , , et al. An evaluation of the use of smartphones to communicate between clinicians: a mixed‐methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e59.

- , , . Computerized physician order entry in the critical care environment: a review of current literature. J Intensive Care Med. 2011;26(3):165–171.

- , , , et al. Factors contributing to an increase in duplicate medication order errors after CPOE implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(6):774–782.

- , , , et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1197–1203.

- , , . Unintended consequences of information technologies in health care—an interactive sociotechnical analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(5):542–549.

- . Why did that happen? Exploring the proliferation of barely usable software in healthcare systems. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;(15 suppl 1):i76–i81.

- , , . Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system‐related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104–112.

- , , . An overview of three different approaches to the interpretation of qualitative data. Part 1: Theoretical issues. Nurse Res. 2002;10(1):30–42.

- , . Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Research in Motion, Amcom Software. Six things hospitals need to know about replacing pagers with smartphones. Available at: http://us.blackberry.com/business/industry/healthcare/6ThingstoKnow_ReplacingHospitalPagers_WhitePaper.pdf. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- Vocera, Wallace Wireless. The Longstreet Clinic: replacing pagers, supercharging communication with WIC pager. Available at: http://www.vocera.com/assets/pdf/case_studies/cs_longstreetclinic_0910_v1.pdf. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- Amcom Software reports strong momentum with its new smartphone messaging and pager replacement solution [press release]. Minneapolis, MN: Amcom Software; September 29, 2010. Available at: http://www.amcomsoftware.com/News/09‐29‐10.aspx. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- College of Nurses of Ontario. 2011 standards and guidelines. Availableat: http://www.cno.org/en/learn‐about‐standards‐guidelines/publications‐list/standards‐and‐guidelines. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- , , . Accountability and responsibility: principle of nursing practice B. Nurs Stand. 2011;25(29):35–36.

- , , , , . The association between interdisciplinary collaboration and patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Heart Lung. 1992;21(1):18–24.

- . Professionalization and socialization in interprofessional collaboration. In: Casto RM, Julia MC, eds. Interprofessional Care and Collaborative Practice. 1st ed. Independence, KY: Cengage Learning; 1994:23–31.

- , . Knowledge translation and interprofessional collaboration: where the rubber of evidence‐based care hits the road of teamwork. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):46–54.

Clinical communication among healthcare providers to coordinate patient care is important, accounting for the majority of information exchanges in healthcare.[1, 2] Breakdowns in communication have therefore been identified as the major contributor to medical errors.[3, 4, 5]

There is a growing literature related to asynchronous clinical communication practices, or communication that does not occur at the same time in hospitals, and the limitations of using the traditional numeric pager. These include the inability to indicate the urgency of the message, frequent interruptions, contacting the wrong physician, and inefficiencies coordinating care across multiple disciplines and specialties.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

Hospitals have implemented a variety of health information technology (HIT) solutions to replace the numeric pager and address these clinical communication issues, including the use of alphanumeric pagers, smartphone devices, and Web‐based applications that allow clinicians to triage the urgency of issues.[13, 14, 15, 16] Although these solutions have resolved some of the deficiencies previously identified, issues relating to the impact on the interprofessional nature of healthcare remain unaddressed.[17] In some cases, the implementation of HIT has created unintended consequences that have an impact on effective communication.

One of the widely cited examples of HIT creating unintended consequences is the implementation of computerized physician order entry systems.[18, 19, 20] Other studies looking more broadly at patient information systems have identified problems caused by poor user interfaces that promoted errors in entry and retrieval of data, inflexible features forcing clinician workarounds, and technology designs that impeded clinical workflow.[21, 22, 23]

These observations suggest that although many of the issues with clinical communication stem from the reliance on numeric paging, simply replacing pagers with newer technology may not solve the problems and can in fact create other unintended consequences. These include unintended consequences resulting from the sociotechnical aspects of HIT, which is the interplay of technology with existing clinical workflow, culture, and social interactions.[21] Our institution recently implemented a Web‐based messaging system to replace the use of numeric pagers. We aimed to evaluate the unintended consequences resulting from the implementation of this system and to describe their impact on the delivery of clinical care on a general internal medicine (GIM) service.

METHODS

This was a pre‐post mixed‐methods study utilizing both quantitative and qualitative measures. We integrated these 2 data‐collection methods to improve the quality of the results. The study was conducted on the GIM service at the University Health Network Toronto Western Hospital site, a tertiary‐care academic teaching center fully affiliated with the University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada). The GIM service at Toronto Western Hospital consists of 4 clinical teams, each staffed by an attending physician, 3 to 4 residents, and 2 to 3 medical students.

Prior to this study, nonface‐to‐face communication on the wards was facilitated through numeric paging, where nurses, pharmacists, and social workers on the GIM wards would page residents to a hospital phone and wait for them to call back. Figures 1, 2, and 3 visualize the Web‐based messaging system we implemented at the University Health Network in May 2010. All residents on the service were provided smartphones that they used for communication. In addition to these, there was a dedicated team smartphone that acted as a central point of contact for the team 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and was carried by the physician covering the team at the time. The system allowed nurses, pharmacists, and social workers to triage the urgency of messages and include details providing context to the issue. Issues flagged as urgent were immediately sent to the team smartphone by e‐mail to alert the physician, who could respond from the smartphone. These messages could be forwarded to a team member, often the physician most familiar with the patient, to address. Issues flagged as nonurgent were posted to the system's message board, which the physicians accessed by logging into the Web‐based messaging system on a regular basis. The message board was designed to allow physicians to respond to multiple non‐urgent issues at once. To close the loop on communication, logic was developed so that if a physician did not respond to a non‐urgent message within the specified timeframe, the message was escalated and sent as an alerting e‐mail to the team smartphone every 15 minutes until it was addressed. The timeframes for responding varied from 1 hour to not needing a response until the next morning.

Ongoing training on the use of the system was built into the clinical orientation for the physician and nursing staff, as turnover in an academic teaching hospital is quite high. The orientation included instructions on how to use the features of the Web‐based messaging system but also provided guidelines on general etiquette with using the system to ensure sustainability of the communication process. For example, physicians were asked to check the system regularly, as the process worked only if they responded to messages. Nurses were asked not to send messages during scheduled educational sessions unless necessary and to limit messages they flagged as urgent to ones that were in fact urgent.

Our quantitative evaluation compared interruptions, which we define as communication that caused a medical resident to stop current activity to address, before and after the implementation of the Web‐based messaging system to assess the volume and time distribution of messages, and compared these results with our qualitative evaluation. For the pre‐implementation phase, interruptions were all numeric pages sent to all residents during the period of July 1427, 2008. For the post‐implementation phase, interruptions were the e‐mails sent directly to the team smartphones from the Web‐based messaging system to all residents during the period of October 1124, 2010. We excluded messages from the postimplementation phase if the same message was sent >10 times, typically indicating technical issues such as a malfunction of the smartphone causing the escalation process to continue.

Our qualitative evaluation consisted of semistructured interviews that were conducted after implementation. A research coordinator sent e‐mails to potential physician participants during a 1‐month rotation (n=16), and nurses (N=50), pharmacists (N=4), and social workers (N=4) from a representative ward inviting them to be part of this study. A set of open‐ended questions (see Supporting Information, Appendix A, in the online version of this article) developed based on informal feedback regarding the system provided by physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers served as a guide to highlight key themes of interest. Based on the participants' responses, further questions were asked to drill down into more detail. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymized.

The interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis to generate categories and overarching themes.[24, 25] Once the coding structure was developed, the transcripts were imported into qualitative analysis software (NVivo 9, QSR International) and then coded and analyzed, pulling the key themes that emerged from the text to be used in interpreting the data.

RESULTS

Our quantitative before‐after comparison of clinical messages sent to physicians revealed an increase in interruptions. We compared these results to the results of our interviews to understand why this might have occurred. Several key themes emerged from the analysis of the interviews, including increase in interruptions, accountability, and tactics to improve personal productivity. We interviewed 5 physicians, 8 nurses, 2 pharmacists, and 2 social workers.

Pre‐Post System Usage Data: Quantitative Assessment

Table 1 outlines the number of numeric pages sent during the pre‐implementation phase of July 1427, 2008. All pages sent immediately alerted the resident and so were all considered interruptions. Table 1 also outlines the number of urgent and escalation messages sent via e‐mail to the residents during the post‐implementation phase of October 1124, 2010. All messages were sent immediately to the team smartphone alerting the resident and so were all considered interruptions. During both timeframes, there were 15 resident physicians on service. During the pre‐implementation phase, 117 patients were admitted to the GIM service, and 162 patients were admitted during the post‐implementation phase.

| Numeric Paging (Predata) | Advance Communication System (Postdata) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pages sent | 710 | Urgent | 951 |

| Interruptions | 710 | Escalations | 1245 |

| Interruptions per resident per day | 3 | Interruptions | 2196 |

| Interruptions per resident per day | 10 | ||

Table 1 shows that the number of interruptions in the pre‐implementation phase was 710 (3 per resident per day) compared with 2196 (10 per resident per day) in the post‐implementation phase, a 233% increase in interruptions. Because admissions were higher in the post‐implementation phase, it is possible that higher patient volumes could have contributed to the increase in interruptions.

Semi‐Structured Interviews: Qualitative Assessment

Increase in Interruptions

The intent of the web‐based messaging system was to reduce interruptions by triaging clinical messages and allowing healthcare professionals to respond to multiple non‐urgent issues at once. The unexpected result, however, was that the frequency at which physicians were interrupted actually increased following implementation.

I feel like I'm constantly bombarded with things Just psychologically I feel like it's harassing me a lot more than the pager used to. [MD02, physician]

Yes. Definitely, I'm paging them more frequently in general than I would have previously. [RN02, nurse]

Increased interruptions occurred in part because traditional barriers to paging, like having to wait by a phone for a response, were eliminated by the new system. Sending a message was easy, and with the reliability introduced through team‐based paging, there was greater temptation to send separate messages for singular issues.

I think [that] before, things were saved up and then paged and given all at once. And now it's, like, there's a temptation just to send things all the time, like, small issues. [AH01, pharmacist]

Communication also increased due to the impersonal nature of the electronic system. With many of the barriers to communicating removed, such as receiving immediate feedback regarding the appropriateness of a message, staff no longer hesitated when sending messages regarding less‐important issues.

So some stuff that you may have not wanted to call for before 'cause it's kind of silly, you can just send it information‐only. So they're aware 'cause the thing about with using electronics it's a lot more impersonal and indirect. [RN03, nurse]

At the same time, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers acknowledged that receiving all of this additional, sometimes unnecessary, information could be frustrating for the physicians. This recognition alone, however, was not sufficient to modify their behavior.

So I find that I can imagine for them it may be a little frustrating 'cause they're getting all these tidbits of information. [RN03, nurse]

I'm sure they get overwhelmed and I've had the feedback from the team They were saying that they were getting constantly paged, not by me, just by me, but by everybody. [AH01, pharmacist]

Accountability

As part of their professional practice, nurses described a medico‐legal obligation to inform physicians about relevant patient issues such as abnormal laboratory values. A culture of accountability, therefore, underpinned many of the actions taken by the nurses, reinforced because the electronic messages sent through the system were permanent and retrievable. The physicians also used the system as an electronic record of discussions that occurred.

Because it's just, like, this thing about accountability in terms of letting them know, that they are aware. [RN03, nurse]

And I think everything you do is recorded, like, you can go back and check, so there's that legal piece, which I guess covers you, in terms of time you called, those things which are critical, what you are calling for. [RN09, nurse]

'Cause I use it now as a reference. So even if I have a phone conversation with a nurse, based on a message that we've had, I will record what we said and send it. [MD03, physician]

Some of the more junior nurses periodically felt unsure or uncomfortable with clinical situations and would send a message to the physician to share their concerns. The messaging reassured the nurses and made them feel like they were fulfilling their professional responsibilities.

So a senior nurse could probably take a look at some situation and they can acknowledge whether the issue is urgent or nonurgent But from a novice perspective, as you're still learning it kind of gives you peace of mind and feels like you're filling your responsibility and accountability, that you're passing on the messages. [RN03, nurse]

Whereas nurses felt they were fulfilling their professional obligations, some physicians felt that nurses were using the system to absolve themselves of their clinical responsibilities.

Some just feel the need to send everything on there and maybe they feel that by sending it on here they absolve themselves of responsibility. [MD05, physician]

Other clinicians felt that the system created more of a responsibility or obligation for the physicians to respond. They believed the escalation feature of the system helped ensure the physicians responded in some fashion to close the loop.

[T]hey have the responsibility to answer it if it's an urgent message and because it keeps coming on to remind them. [AH02, social worker]

Interestingly, there were physicians that identified the opposite and felt the system created less of a responsibility or obligation for them to respond. By knowing the context of the message, it gave them the ability to prioritize or ignore the message if they knew it was not life threatening.

[T]here's less of a responsibility or an obligation They get a message and then they can actually delay the process So in a way it actually allows us to kind of get away with some things and that happens because, you know, we're prioritizing something that we're doing as being more important to us. [MD01, physician]

Tactics to Improve Personal Productivity

The web‐based messaging system's triaging feature allows the sender of the message to indicate whether an issue is urgent or non‐urgent. Urgent issues result in an immediate e‐mail that is intended to elicit an immediate response. Some of the nurses, pharmacists, and social workers exploited features of the system to elicit immediate responses from the physicians for non‐urgent issues, including using their knowledge of the urgent and non‐urgent features of the system to interrupt the physicians.

I kind of cheat and don't use the system properly. So every message I send I always send it as urgent because I want it go to the smartphone. [AH01, pharmacist]

I like that if you know how to use the urgent and nonurgent features effectively it generally works quite well in getting a response in a timely fashion. [RN02, nurse]

One tactic that physicians perceived the nurses were using to elicit a response from them was to exaggerate the severity or urgency of the issue in their message.

Some details will be sort of cherry picked to make the issue sound very dire I'll give you a classic, like, high blood pressure and patient has a headache. So initially, you know, I have to think, does this patient have a hypertensive emergency? So by putting sort of history together in this way, that sort of suggestive way, then yeah. [MD03, physician]

The nurses, pharmacists. and social workers frequently exaggerated the urgency of their clinical messages at the end of their shifts in an effort to resolve outstanding issues immediately in order to avoid transferring tasks to another colleague or delaying them until the next day.

But in terms of a shift change, for example, I need a response now 'cause that is a lot of times where it is that although it's not clinically urgent it's time sensitive. So it is urgent. [RN02, nurse]

I do also notice that around changeover time, issues that have been sort of chronically or have preexisting, become urgent issues. [MD01, physician]

Messages were also sent inappropriately as urgent as a strategy to ensure the physician dealt with the issue promptly and did not forget to complete the requested task associated with the issue.

Everybody puts urgent because we want the response immediately. Otherwise, if you put nonurgent, the doctors will just drag and drag and will forget to respond to the issue. [RN09, nurse]

However, because physicians received context clarifying the urgency of the message, they were able to prioritize their tasks and defer less‐important issues without compromising patient safety or quality of care, allowing them to use their time more productively. This, however, did not always align with the sender's request.

I think the key thing is that the information coming to us is text and it describes the issue. So we can, at our end, then we can make a call as to what the priority is. [MD03, physician]

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate a Web‐based messaging system and identify the unintended consequences observed with implementing HIT to improve clinical communication. This is an important study because healthcare organizations are beginning to develop strategies for improving clinical communication but believe the solution involves simply replacing pager technology. Support for this approach is seen with larger vendors in the smartphone and communication industry, who promote their products as pager‐replacement solutions and even help customers develop pager‐replacement strategies.[26, 27, 28] Simply replacing pagers with smartphones and sending text messages will have only a limited impact on improving clinical communication and will likely result in unintended negative consequences, as seen in this study.

Whereas the Web‐based messaging system was designed to reduce interruptions from clinical messaging, interruptions actually increased, although the mental burden of each interruption was likely lower because responding to a text message is less interruptive than finding a telephone to answer a page. A key contributor to this effect was a culture of accountability among nurses, pharmacists, and social workers who felt it was their professional obligation to notify physicians about all issues of concern. This belief and related behavior is aligned with the standards promoted by professional regulatory bodies that identify accountability as a vital practice expectation.[29] Nurses and nursing staff take responsibility for the care they provide and answer for their own judgments and actions.[30] The system eliminated many of the previous barriers to paging and provided a less‐personal form of communication. The cumulative and unexpected outcome was an increase of interruptions for physicians and the adoption of workarounds by all healthcare professionals to improve personal productivity. Although the system was built in an iterative fashion with frontline clinicians, it is likely that oversights in the design of the system also contributed to these problems, which speaks to the complexity of clinical communication. Centralizing communication to the team smartphone could have overburdened the physicians covering it at the time, causing them to ignore messages because they were too busy to address them.

There were limitations to this study. One limitation was that this study examined only a cross‐section of messaging activity at a given point in time, and therefore it may not be representative of the behaviors of the physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers over time as the culture of the environment evolves and they adjust to the new technology. The pre‐implementation data were collected 2 years prior to the post‐implementation data, but it was necessary to use data this old because other interventions were implemented prior to the Web‐based messaging system, so baseline paging data were no longer available. Whereas most clinical disciplines were represented in the interviews, the sample included only 17 participants from 1 clinical service, so generalizability of the results may be limited.

Although the reliance on numeric paging technology was previously identified as a primary source of problems with communication, the real issues are much more complex. This study highlighted that many of the underlying obstacles relate to existing social interactions and habits of multiple professions working together. Failures in collaboration among healthcare professionals have a negative impact on health outcomes and routinely stem from the lack of explicit definitions of roles, the absence of clear leadership, insufficient time for team‐building, the us‐and‐them effects created by professional socialization, and frustration created by power and status differentials of each discipline.[31, 32, 33] Therefore, it is critical that healthcare organizations focus on the people and clinical processes when implementing technology to solve issues with clinical communication. These observations are consistent with other studies examining the unintended consequences caused by the sociotechnical aspects of HIT implementation, where workarounds to game the system were also employed.[21]

In summary, improving clinical communication cannot be achieved simply by replacing pagers with newer technology; it requires a fundamental shift in how healthcare professionals interact, with a focus on the sociotechnical aspects of HIT. As patient volumes and the complexity of care continue to increase, more effective methods for facilitating interprofessional communication and collaboration must be developed.

Acknowledgements

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Clinical communication among healthcare providers to coordinate patient care is important, accounting for the majority of information exchanges in healthcare.[1, 2] Breakdowns in communication have therefore been identified as the major contributor to medical errors.[3, 4, 5]

There is a growing literature related to asynchronous clinical communication practices, or communication that does not occur at the same time in hospitals, and the limitations of using the traditional numeric pager. These include the inability to indicate the urgency of the message, frequent interruptions, contacting the wrong physician, and inefficiencies coordinating care across multiple disciplines and specialties.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

Hospitals have implemented a variety of health information technology (HIT) solutions to replace the numeric pager and address these clinical communication issues, including the use of alphanumeric pagers, smartphone devices, and Web‐based applications that allow clinicians to triage the urgency of issues.[13, 14, 15, 16] Although these solutions have resolved some of the deficiencies previously identified, issues relating to the impact on the interprofessional nature of healthcare remain unaddressed.[17] In some cases, the implementation of HIT has created unintended consequences that have an impact on effective communication.

One of the widely cited examples of HIT creating unintended consequences is the implementation of computerized physician order entry systems.[18, 19, 20] Other studies looking more broadly at patient information systems have identified problems caused by poor user interfaces that promoted errors in entry and retrieval of data, inflexible features forcing clinician workarounds, and technology designs that impeded clinical workflow.[21, 22, 23]

These observations suggest that although many of the issues with clinical communication stem from the reliance on numeric paging, simply replacing pagers with newer technology may not solve the problems and can in fact create other unintended consequences. These include unintended consequences resulting from the sociotechnical aspects of HIT, which is the interplay of technology with existing clinical workflow, culture, and social interactions.[21] Our institution recently implemented a Web‐based messaging system to replace the use of numeric pagers. We aimed to evaluate the unintended consequences resulting from the implementation of this system and to describe their impact on the delivery of clinical care on a general internal medicine (GIM) service.

METHODS

This was a pre‐post mixed‐methods study utilizing both quantitative and qualitative measures. We integrated these 2 data‐collection methods to improve the quality of the results. The study was conducted on the GIM service at the University Health Network Toronto Western Hospital site, a tertiary‐care academic teaching center fully affiliated with the University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada). The GIM service at Toronto Western Hospital consists of 4 clinical teams, each staffed by an attending physician, 3 to 4 residents, and 2 to 3 medical students.

Prior to this study, nonface‐to‐face communication on the wards was facilitated through numeric paging, where nurses, pharmacists, and social workers on the GIM wards would page residents to a hospital phone and wait for them to call back. Figures 1, 2, and 3 visualize the Web‐based messaging system we implemented at the University Health Network in May 2010. All residents on the service were provided smartphones that they used for communication. In addition to these, there was a dedicated team smartphone that acted as a central point of contact for the team 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and was carried by the physician covering the team at the time. The system allowed nurses, pharmacists, and social workers to triage the urgency of messages and include details providing context to the issue. Issues flagged as urgent were immediately sent to the team smartphone by e‐mail to alert the physician, who could respond from the smartphone. These messages could be forwarded to a team member, often the physician most familiar with the patient, to address. Issues flagged as nonurgent were posted to the system's message board, which the physicians accessed by logging into the Web‐based messaging system on a regular basis. The message board was designed to allow physicians to respond to multiple non‐urgent issues at once. To close the loop on communication, logic was developed so that if a physician did not respond to a non‐urgent message within the specified timeframe, the message was escalated and sent as an alerting e‐mail to the team smartphone every 15 minutes until it was addressed. The timeframes for responding varied from 1 hour to not needing a response until the next morning.

Ongoing training on the use of the system was built into the clinical orientation for the physician and nursing staff, as turnover in an academic teaching hospital is quite high. The orientation included instructions on how to use the features of the Web‐based messaging system but also provided guidelines on general etiquette with using the system to ensure sustainability of the communication process. For example, physicians were asked to check the system regularly, as the process worked only if they responded to messages. Nurses were asked not to send messages during scheduled educational sessions unless necessary and to limit messages they flagged as urgent to ones that were in fact urgent.

Our quantitative evaluation compared interruptions, which we define as communication that caused a medical resident to stop current activity to address, before and after the implementation of the Web‐based messaging system to assess the volume and time distribution of messages, and compared these results with our qualitative evaluation. For the pre‐implementation phase, interruptions were all numeric pages sent to all residents during the period of July 1427, 2008. For the post‐implementation phase, interruptions were the e‐mails sent directly to the team smartphones from the Web‐based messaging system to all residents during the period of October 1124, 2010. We excluded messages from the postimplementation phase if the same message was sent >10 times, typically indicating technical issues such as a malfunction of the smartphone causing the escalation process to continue.

Our qualitative evaluation consisted of semistructured interviews that were conducted after implementation. A research coordinator sent e‐mails to potential physician participants during a 1‐month rotation (n=16), and nurses (N=50), pharmacists (N=4), and social workers (N=4) from a representative ward inviting them to be part of this study. A set of open‐ended questions (see Supporting Information, Appendix A, in the online version of this article) developed based on informal feedback regarding the system provided by physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers served as a guide to highlight key themes of interest. Based on the participants' responses, further questions were asked to drill down into more detail. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymized.

The interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis to generate categories and overarching themes.[24, 25] Once the coding structure was developed, the transcripts were imported into qualitative analysis software (NVivo 9, QSR International) and then coded and analyzed, pulling the key themes that emerged from the text to be used in interpreting the data.

RESULTS

Our quantitative before‐after comparison of clinical messages sent to physicians revealed an increase in interruptions. We compared these results to the results of our interviews to understand why this might have occurred. Several key themes emerged from the analysis of the interviews, including increase in interruptions, accountability, and tactics to improve personal productivity. We interviewed 5 physicians, 8 nurses, 2 pharmacists, and 2 social workers.

Pre‐Post System Usage Data: Quantitative Assessment

Table 1 outlines the number of numeric pages sent during the pre‐implementation phase of July 1427, 2008. All pages sent immediately alerted the resident and so were all considered interruptions. Table 1 also outlines the number of urgent and escalation messages sent via e‐mail to the residents during the post‐implementation phase of October 1124, 2010. All messages were sent immediately to the team smartphone alerting the resident and so were all considered interruptions. During both timeframes, there were 15 resident physicians on service. During the pre‐implementation phase, 117 patients were admitted to the GIM service, and 162 patients were admitted during the post‐implementation phase.

| Numeric Paging (Predata) | Advance Communication System (Postdata) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pages sent | 710 | Urgent | 951 |

| Interruptions | 710 | Escalations | 1245 |

| Interruptions per resident per day | 3 | Interruptions | 2196 |

| Interruptions per resident per day | 10 | ||

Table 1 shows that the number of interruptions in the pre‐implementation phase was 710 (3 per resident per day) compared with 2196 (10 per resident per day) in the post‐implementation phase, a 233% increase in interruptions. Because admissions were higher in the post‐implementation phase, it is possible that higher patient volumes could have contributed to the increase in interruptions.

Semi‐Structured Interviews: Qualitative Assessment

Increase in Interruptions

The intent of the web‐based messaging system was to reduce interruptions by triaging clinical messages and allowing healthcare professionals to respond to multiple non‐urgent issues at once. The unexpected result, however, was that the frequency at which physicians were interrupted actually increased following implementation.

I feel like I'm constantly bombarded with things Just psychologically I feel like it's harassing me a lot more than the pager used to. [MD02, physician]

Yes. Definitely, I'm paging them more frequently in general than I would have previously. [RN02, nurse]

Increased interruptions occurred in part because traditional barriers to paging, like having to wait by a phone for a response, were eliminated by the new system. Sending a message was easy, and with the reliability introduced through team‐based paging, there was greater temptation to send separate messages for singular issues.

I think [that] before, things were saved up and then paged and given all at once. And now it's, like, there's a temptation just to send things all the time, like, small issues. [AH01, pharmacist]

Communication also increased due to the impersonal nature of the electronic system. With many of the barriers to communicating removed, such as receiving immediate feedback regarding the appropriateness of a message, staff no longer hesitated when sending messages regarding less‐important issues.

So some stuff that you may have not wanted to call for before 'cause it's kind of silly, you can just send it information‐only. So they're aware 'cause the thing about with using electronics it's a lot more impersonal and indirect. [RN03, nurse]

At the same time, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers acknowledged that receiving all of this additional, sometimes unnecessary, information could be frustrating for the physicians. This recognition alone, however, was not sufficient to modify their behavior.

So I find that I can imagine for them it may be a little frustrating 'cause they're getting all these tidbits of information. [RN03, nurse]

I'm sure they get overwhelmed and I've had the feedback from the team They were saying that they were getting constantly paged, not by me, just by me, but by everybody. [AH01, pharmacist]

Accountability

As part of their professional practice, nurses described a medico‐legal obligation to inform physicians about relevant patient issues such as abnormal laboratory values. A culture of accountability, therefore, underpinned many of the actions taken by the nurses, reinforced because the electronic messages sent through the system were permanent and retrievable. The physicians also used the system as an electronic record of discussions that occurred.

Because it's just, like, this thing about accountability in terms of letting them know, that they are aware. [RN03, nurse]

And I think everything you do is recorded, like, you can go back and check, so there's that legal piece, which I guess covers you, in terms of time you called, those things which are critical, what you are calling for. [RN09, nurse]

'Cause I use it now as a reference. So even if I have a phone conversation with a nurse, based on a message that we've had, I will record what we said and send it. [MD03, physician]

Some of the more junior nurses periodically felt unsure or uncomfortable with clinical situations and would send a message to the physician to share their concerns. The messaging reassured the nurses and made them feel like they were fulfilling their professional responsibilities.

So a senior nurse could probably take a look at some situation and they can acknowledge whether the issue is urgent or nonurgent But from a novice perspective, as you're still learning it kind of gives you peace of mind and feels like you're filling your responsibility and accountability, that you're passing on the messages. [RN03, nurse]

Whereas nurses felt they were fulfilling their professional obligations, some physicians felt that nurses were using the system to absolve themselves of their clinical responsibilities.

Some just feel the need to send everything on there and maybe they feel that by sending it on here they absolve themselves of responsibility. [MD05, physician]

Other clinicians felt that the system created more of a responsibility or obligation for the physicians to respond. They believed the escalation feature of the system helped ensure the physicians responded in some fashion to close the loop.

[T]hey have the responsibility to answer it if it's an urgent message and because it keeps coming on to remind them. [AH02, social worker]

Interestingly, there were physicians that identified the opposite and felt the system created less of a responsibility or obligation for them to respond. By knowing the context of the message, it gave them the ability to prioritize or ignore the message if they knew it was not life threatening.

[T]here's less of a responsibility or an obligation They get a message and then they can actually delay the process So in a way it actually allows us to kind of get away with some things and that happens because, you know, we're prioritizing something that we're doing as being more important to us. [MD01, physician]

Tactics to Improve Personal Productivity

The web‐based messaging system's triaging feature allows the sender of the message to indicate whether an issue is urgent or non‐urgent. Urgent issues result in an immediate e‐mail that is intended to elicit an immediate response. Some of the nurses, pharmacists, and social workers exploited features of the system to elicit immediate responses from the physicians for non‐urgent issues, including using their knowledge of the urgent and non‐urgent features of the system to interrupt the physicians.

I kind of cheat and don't use the system properly. So every message I send I always send it as urgent because I want it go to the smartphone. [AH01, pharmacist]

I like that if you know how to use the urgent and nonurgent features effectively it generally works quite well in getting a response in a timely fashion. [RN02, nurse]

One tactic that physicians perceived the nurses were using to elicit a response from them was to exaggerate the severity or urgency of the issue in their message.

Some details will be sort of cherry picked to make the issue sound very dire I'll give you a classic, like, high blood pressure and patient has a headache. So initially, you know, I have to think, does this patient have a hypertensive emergency? So by putting sort of history together in this way, that sort of suggestive way, then yeah. [MD03, physician]

The nurses, pharmacists. and social workers frequently exaggerated the urgency of their clinical messages at the end of their shifts in an effort to resolve outstanding issues immediately in order to avoid transferring tasks to another colleague or delaying them until the next day.

But in terms of a shift change, for example, I need a response now 'cause that is a lot of times where it is that although it's not clinically urgent it's time sensitive. So it is urgent. [RN02, nurse]

I do also notice that around changeover time, issues that have been sort of chronically or have preexisting, become urgent issues. [MD01, physician]

Messages were also sent inappropriately as urgent as a strategy to ensure the physician dealt with the issue promptly and did not forget to complete the requested task associated with the issue.

Everybody puts urgent because we want the response immediately. Otherwise, if you put nonurgent, the doctors will just drag and drag and will forget to respond to the issue. [RN09, nurse]

However, because physicians received context clarifying the urgency of the message, they were able to prioritize their tasks and defer less‐important issues without compromising patient safety or quality of care, allowing them to use their time more productively. This, however, did not always align with the sender's request.

I think the key thing is that the information coming to us is text and it describes the issue. So we can, at our end, then we can make a call as to what the priority is. [MD03, physician]

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate a Web‐based messaging system and identify the unintended consequences observed with implementing HIT to improve clinical communication. This is an important study because healthcare organizations are beginning to develop strategies for improving clinical communication but believe the solution involves simply replacing pager technology. Support for this approach is seen with larger vendors in the smartphone and communication industry, who promote their products as pager‐replacement solutions and even help customers develop pager‐replacement strategies.[26, 27, 28] Simply replacing pagers with smartphones and sending text messages will have only a limited impact on improving clinical communication and will likely result in unintended negative consequences, as seen in this study.

Whereas the Web‐based messaging system was designed to reduce interruptions from clinical messaging, interruptions actually increased, although the mental burden of each interruption was likely lower because responding to a text message is less interruptive than finding a telephone to answer a page. A key contributor to this effect was a culture of accountability among nurses, pharmacists, and social workers who felt it was their professional obligation to notify physicians about all issues of concern. This belief and related behavior is aligned with the standards promoted by professional regulatory bodies that identify accountability as a vital practice expectation.[29] Nurses and nursing staff take responsibility for the care they provide and answer for their own judgments and actions.[30] The system eliminated many of the previous barriers to paging and provided a less‐personal form of communication. The cumulative and unexpected outcome was an increase of interruptions for physicians and the adoption of workarounds by all healthcare professionals to improve personal productivity. Although the system was built in an iterative fashion with frontline clinicians, it is likely that oversights in the design of the system also contributed to these problems, which speaks to the complexity of clinical communication. Centralizing communication to the team smartphone could have overburdened the physicians covering it at the time, causing them to ignore messages because they were too busy to address them.

There were limitations to this study. One limitation was that this study examined only a cross‐section of messaging activity at a given point in time, and therefore it may not be representative of the behaviors of the physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers over time as the culture of the environment evolves and they adjust to the new technology. The pre‐implementation data were collected 2 years prior to the post‐implementation data, but it was necessary to use data this old because other interventions were implemented prior to the Web‐based messaging system, so baseline paging data were no longer available. Whereas most clinical disciplines were represented in the interviews, the sample included only 17 participants from 1 clinical service, so generalizability of the results may be limited.

Although the reliance on numeric paging technology was previously identified as a primary source of problems with communication, the real issues are much more complex. This study highlighted that many of the underlying obstacles relate to existing social interactions and habits of multiple professions working together. Failures in collaboration among healthcare professionals have a negative impact on health outcomes and routinely stem from the lack of explicit definitions of roles, the absence of clear leadership, insufficient time for team‐building, the us‐and‐them effects created by professional socialization, and frustration created by power and status differentials of each discipline.[31, 32, 33] Therefore, it is critical that healthcare organizations focus on the people and clinical processes when implementing technology to solve issues with clinical communication. These observations are consistent with other studies examining the unintended consequences caused by the sociotechnical aspects of HIT implementation, where workarounds to game the system were also employed.[21]

In summary, improving clinical communication cannot be achieved simply by replacing pagers with newer technology; it requires a fundamental shift in how healthcare professionals interact, with a focus on the sociotechnical aspects of HIT. As patient volumes and the complexity of care continue to increase, more effective methods for facilitating interprofessional communication and collaboration must be developed.

Acknowledgements

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- . When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277–286.

- , , , et al. Synchronous communication facilitates interruptive workflow for attending physicians and nurses in clinical settings. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(9):629–637.

- , , , et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):377–384.

- , , . Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186–194.

- The Joint Commission. Improving America's Hospitals: The Joint Commission's Annual Report on Quality and Safety. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2007. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2007_Annual_Report.pdf. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- , . Residents' suggestions for reducing errors in teaching hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(9):851–855.

- , . Interruptions in healthcare: theoretical views. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(5):293–307.

- , , , et al. Frequency and clinical importance of pages sent to the wrong physician. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(11):1072–1073.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–407.

- , , , , , . Towards safer interprofessional communication: Constructing a model of “utility” from preoperative team briefings. J Interprof Care. 2006;20(5):471–483.

- , , . Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice‐based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD000072.

- , . The effects of hands free communication devices on clinical communication: balancing communication access needs with user control. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008;621–625.

- , , , , . Beyond paging: building a web‐based communication tool for nurses and physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):105–110.

- , , , et al. The use of smartphones for clinical communication on internal medicine wards. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):553–559.

- , , , . Implementation and evaluation of an alpha‐numeric paging system on a resident inpatient teaching service. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):E34–E40.

- , , , et al. Effects of clinical communication interventions in hospitals: a systematic review of information and communication technology adoptions for improved communication between clinicians. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(11):723–732.

- , , , et al. An evaluation of the use of smartphones to communicate between clinicians: a mixed‐methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e59.

- , , . Computerized physician order entry in the critical care environment: a review of current literature. J Intensive Care Med. 2011;26(3):165–171.

- , , , et al. Factors contributing to an increase in duplicate medication order errors after CPOE implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(6):774–782.

- , , , et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1197–1203.

- , , . Unintended consequences of information technologies in health care—an interactive sociotechnical analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(5):542–549.

- . Why did that happen? Exploring the proliferation of barely usable software in healthcare systems. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;(15 suppl 1):i76–i81.

- , , . Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system‐related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104–112.

- , , . An overview of three different approaches to the interpretation of qualitative data. Part 1: Theoretical issues. Nurse Res. 2002;10(1):30–42.

- , . Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Research in Motion, Amcom Software. Six things hospitals need to know about replacing pagers with smartphones. Available at: http://us.blackberry.com/business/industry/healthcare/6ThingstoKnow_ReplacingHospitalPagers_WhitePaper.pdf. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- Vocera, Wallace Wireless. The Longstreet Clinic: replacing pagers, supercharging communication with WIC pager. Available at: http://www.vocera.com/assets/pdf/case_studies/cs_longstreetclinic_0910_v1.pdf. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- Amcom Software reports strong momentum with its new smartphone messaging and pager replacement solution [press release]. Minneapolis, MN: Amcom Software; September 29, 2010. Available at: http://www.amcomsoftware.com/News/09‐29‐10.aspx. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- College of Nurses of Ontario. 2011 standards and guidelines. Availableat: http://www.cno.org/en/learn‐about‐standards‐guidelines/publications‐list/standards‐and‐guidelines. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- , , . Accountability and responsibility: principle of nursing practice B. Nurs Stand. 2011;25(29):35–36.

- , , , , . The association between interdisciplinary collaboration and patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Heart Lung. 1992;21(1):18–24.

- . Professionalization and socialization in interprofessional collaboration. In: Casto RM, Julia MC, eds. Interprofessional Care and Collaborative Practice. 1st ed. Independence, KY: Cengage Learning; 1994:23–31.