User login

Stroke risk in new-onset atrial fib goes up with greater alcohol intake

There’s abundant evidence linking higher alcohol intake levels to greater stroke risk and, separately, increasing risk for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib). Less settled is whether moderate to heavy drinking worsens the risk for stroke in patients already in AFib and whether giving up alcohol can attenuate that risk. A new observational study suggests the answer to both questions is yes.

The risk for ischemic stroke was only around 1% over about 5 years in a Korean nationwide cohort of almost 98,000 patients with new-onset AFib. About half the patients followed were nondrinkers, as they had been before the study, 13% became abstinent soon after their AFib diagnosis, and 36% were currently drinkers.

But stroke risk went up about 30% with “moderate” current alcohol intake, compared with no intake, and by more than 40% for current drinkers reporting “heavy” alcohol intake, researchers found in an adjusted analysis.

However, abstainers who had mild to moderate alcohol-intake levels before their AFib diagnosis “had a similar risk of ischemic stroke as nondrinkers,” write the authors, led by So-Ryoung Lee, MD, PhD, and colleagues, Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea, in their report published June 7 in the European Heart Journal. In a secondary analysis, binge drinking was also independently associated with risk for ischemic stroke.

The findings suggest that “alcohol abstinence after the diagnosis of AFib could reduce the risk of ischemic stroke,” they conclude. “Lifestyle interventions, including attention to alcohol consumption, should be encouraged as part of a comprehensive approach in the management of patients with a new diagnosis of AFib” for lowering the risk for stroke and other clinical outcomes.

“These results are pretty comparable to those obtained in the more general population,” David Conen, MD, MPH, not connected to the analysis, told this news organization.

In the study’s population with new-onset AFib, there is an alcohol-dependent risk for stroke “that goes up with increasing alcohol intake, which is more or less similar to that found without atrial fibrillation in previous studies,” said Dr. Conen, from the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The study, “which overall I think is very well done,” he said, is noteworthy for also suggesting that binge drinking, which was scrutinized in a secondary analysis, appeared independently to worsen the risk for stroke in its AFib population.

Dr. Conen said the observed 1% overall risk for stroke was very similar to the rate he and his colleagues saw in a recent combined analysis of two European cohorts with AFib that was usually longer standing; the median was 3 years. That analysis, in contrast, showed no significant association between increasing levels of alcohol intake and risk for stroke or systemic embolism.

However, “our confidence limits did not exclude the possibility of a small to moderate association,” he said. Given that, and the current study from Korea, there might indeed be “a weak association between alcohol consumption and stroke” in patients with AFib.

“Their results are just more precise because of the larger sample size. That’s why they were able to show those associations,” said Dr. Conen, who was senior author on the earlier report, which covered a pooled analysis of 3,852 patients with AFib in the BEAT-AF and SWISS-AF cohort studies. It was published January 25 in CMAJ, with lead author Philipp Reddiess, MD, Cardiovascular Research Institute Basel, Switzerland.

The two published studies contrast in other ways that are worth noting and together suggest the stroke rate might have been 1% in both by chance, Dr. Conen said. “The populations were pretty different.”

In the earlier study, for example, the overwhelmingly European patients had more comorbidities and had been in AFib for much longer; their mean age was 71 years; and 84% were on oral anticoagulation (OAC).

In contrast, the Korean cohort averaged 61 years in age and only about 24% were taking oral anticoagulants. Given their distribution of CHA2DS2-VASc scores and mean score of 2.3, more than twice as many should have been on OAC, Dr. Conen speculated. “Even if you take into account that some patients may have contraindications, this is clearly an underanticoagulated population.”

The European cohort might have been “a little bit more representative because atrial fibrillation is a disease of the elderly,” Dr. Conen said, but “the Korean paper has the advantage of being a population-based study.”

It involved 97,869 patients from a Korean national data base who were newly diagnosed with AFib from 2010 to 2016. Of the total, 49,781 (51%) were continuously nondrinkers before and after their diagnosis; 12,789 (13%) abstained from alcohol only after their AFib diagnosis; and 35,299 (36%) were drinkers during the follow-up, either because they continued to drink or newly started after their diagnosis.

Of the cohort, 3,120 were diagnosed with new ischemic stroke over a follow-up of 310,926 person-years, for a rate of 1 per 100 person-years.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke over a 5-year follow-up, compared with nondrinkers, was:

- 1.127 (95% confidence interval, 1.003-1.266) among abstainers

- 1.280 (95% CI, 1.166-1.405) for current drinkers

The corresponding HR, compared with current drinkers, was:

- 0.781 (95% CI, 0.712-0.858) for nondrinkers

- 0.880 (95% CI, 0.782-0.990) among abstainers

No significant interactions with ischemic stroke risk were observed in groups by sex, age, CHA2DS2-VASc score, or smoking status. The risk rose consistently with current drinking levels.

The overall stroke rate of 1% per year is “very low,” and “the absolute differences are small, even though there is a clear significant trend from nondrinking to drinking,” Dr. Conen said.

However, “the difference becomes more sizable when you compare heavy drinking to abstinence.”

Dr. Lee reports no conflicts of interest; disclosures for the other authors are in their report. Dr. Conen reports receiving speaker fees from Servier Canada; disclosures for the other authors are in their report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There’s abundant evidence linking higher alcohol intake levels to greater stroke risk and, separately, increasing risk for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib). Less settled is whether moderate to heavy drinking worsens the risk for stroke in patients already in AFib and whether giving up alcohol can attenuate that risk. A new observational study suggests the answer to both questions is yes.

The risk for ischemic stroke was only around 1% over about 5 years in a Korean nationwide cohort of almost 98,000 patients with new-onset AFib. About half the patients followed were nondrinkers, as they had been before the study, 13% became abstinent soon after their AFib diagnosis, and 36% were currently drinkers.

But stroke risk went up about 30% with “moderate” current alcohol intake, compared with no intake, and by more than 40% for current drinkers reporting “heavy” alcohol intake, researchers found in an adjusted analysis.

However, abstainers who had mild to moderate alcohol-intake levels before their AFib diagnosis “had a similar risk of ischemic stroke as nondrinkers,” write the authors, led by So-Ryoung Lee, MD, PhD, and colleagues, Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea, in their report published June 7 in the European Heart Journal. In a secondary analysis, binge drinking was also independently associated with risk for ischemic stroke.

The findings suggest that “alcohol abstinence after the diagnosis of AFib could reduce the risk of ischemic stroke,” they conclude. “Lifestyle interventions, including attention to alcohol consumption, should be encouraged as part of a comprehensive approach in the management of patients with a new diagnosis of AFib” for lowering the risk for stroke and other clinical outcomes.

“These results are pretty comparable to those obtained in the more general population,” David Conen, MD, MPH, not connected to the analysis, told this news organization.

In the study’s population with new-onset AFib, there is an alcohol-dependent risk for stroke “that goes up with increasing alcohol intake, which is more or less similar to that found without atrial fibrillation in previous studies,” said Dr. Conen, from the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The study, “which overall I think is very well done,” he said, is noteworthy for also suggesting that binge drinking, which was scrutinized in a secondary analysis, appeared independently to worsen the risk for stroke in its AFib population.

Dr. Conen said the observed 1% overall risk for stroke was very similar to the rate he and his colleagues saw in a recent combined analysis of two European cohorts with AFib that was usually longer standing; the median was 3 years. That analysis, in contrast, showed no significant association between increasing levels of alcohol intake and risk for stroke or systemic embolism.

However, “our confidence limits did not exclude the possibility of a small to moderate association,” he said. Given that, and the current study from Korea, there might indeed be “a weak association between alcohol consumption and stroke” in patients with AFib.

“Their results are just more precise because of the larger sample size. That’s why they were able to show those associations,” said Dr. Conen, who was senior author on the earlier report, which covered a pooled analysis of 3,852 patients with AFib in the BEAT-AF and SWISS-AF cohort studies. It was published January 25 in CMAJ, with lead author Philipp Reddiess, MD, Cardiovascular Research Institute Basel, Switzerland.

The two published studies contrast in other ways that are worth noting and together suggest the stroke rate might have been 1% in both by chance, Dr. Conen said. “The populations were pretty different.”

In the earlier study, for example, the overwhelmingly European patients had more comorbidities and had been in AFib for much longer; their mean age was 71 years; and 84% were on oral anticoagulation (OAC).

In contrast, the Korean cohort averaged 61 years in age and only about 24% were taking oral anticoagulants. Given their distribution of CHA2DS2-VASc scores and mean score of 2.3, more than twice as many should have been on OAC, Dr. Conen speculated. “Even if you take into account that some patients may have contraindications, this is clearly an underanticoagulated population.”

The European cohort might have been “a little bit more representative because atrial fibrillation is a disease of the elderly,” Dr. Conen said, but “the Korean paper has the advantage of being a population-based study.”

It involved 97,869 patients from a Korean national data base who were newly diagnosed with AFib from 2010 to 2016. Of the total, 49,781 (51%) were continuously nondrinkers before and after their diagnosis; 12,789 (13%) abstained from alcohol only after their AFib diagnosis; and 35,299 (36%) were drinkers during the follow-up, either because they continued to drink or newly started after their diagnosis.

Of the cohort, 3,120 were diagnosed with new ischemic stroke over a follow-up of 310,926 person-years, for a rate of 1 per 100 person-years.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke over a 5-year follow-up, compared with nondrinkers, was:

- 1.127 (95% confidence interval, 1.003-1.266) among abstainers

- 1.280 (95% CI, 1.166-1.405) for current drinkers

The corresponding HR, compared with current drinkers, was:

- 0.781 (95% CI, 0.712-0.858) for nondrinkers

- 0.880 (95% CI, 0.782-0.990) among abstainers

No significant interactions with ischemic stroke risk were observed in groups by sex, age, CHA2DS2-VASc score, or smoking status. The risk rose consistently with current drinking levels.

The overall stroke rate of 1% per year is “very low,” and “the absolute differences are small, even though there is a clear significant trend from nondrinking to drinking,” Dr. Conen said.

However, “the difference becomes more sizable when you compare heavy drinking to abstinence.”

Dr. Lee reports no conflicts of interest; disclosures for the other authors are in their report. Dr. Conen reports receiving speaker fees from Servier Canada; disclosures for the other authors are in their report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There’s abundant evidence linking higher alcohol intake levels to greater stroke risk and, separately, increasing risk for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib). Less settled is whether moderate to heavy drinking worsens the risk for stroke in patients already in AFib and whether giving up alcohol can attenuate that risk. A new observational study suggests the answer to both questions is yes.

The risk for ischemic stroke was only around 1% over about 5 years in a Korean nationwide cohort of almost 98,000 patients with new-onset AFib. About half the patients followed were nondrinkers, as they had been before the study, 13% became abstinent soon after their AFib diagnosis, and 36% were currently drinkers.

But stroke risk went up about 30% with “moderate” current alcohol intake, compared with no intake, and by more than 40% for current drinkers reporting “heavy” alcohol intake, researchers found in an adjusted analysis.

However, abstainers who had mild to moderate alcohol-intake levels before their AFib diagnosis “had a similar risk of ischemic stroke as nondrinkers,” write the authors, led by So-Ryoung Lee, MD, PhD, and colleagues, Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea, in their report published June 7 in the European Heart Journal. In a secondary analysis, binge drinking was also independently associated with risk for ischemic stroke.

The findings suggest that “alcohol abstinence after the diagnosis of AFib could reduce the risk of ischemic stroke,” they conclude. “Lifestyle interventions, including attention to alcohol consumption, should be encouraged as part of a comprehensive approach in the management of patients with a new diagnosis of AFib” for lowering the risk for stroke and other clinical outcomes.

“These results are pretty comparable to those obtained in the more general population,” David Conen, MD, MPH, not connected to the analysis, told this news organization.

In the study’s population with new-onset AFib, there is an alcohol-dependent risk for stroke “that goes up with increasing alcohol intake, which is more or less similar to that found without atrial fibrillation in previous studies,” said Dr. Conen, from the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

The study, “which overall I think is very well done,” he said, is noteworthy for also suggesting that binge drinking, which was scrutinized in a secondary analysis, appeared independently to worsen the risk for stroke in its AFib population.

Dr. Conen said the observed 1% overall risk for stroke was very similar to the rate he and his colleagues saw in a recent combined analysis of two European cohorts with AFib that was usually longer standing; the median was 3 years. That analysis, in contrast, showed no significant association between increasing levels of alcohol intake and risk for stroke or systemic embolism.

However, “our confidence limits did not exclude the possibility of a small to moderate association,” he said. Given that, and the current study from Korea, there might indeed be “a weak association between alcohol consumption and stroke” in patients with AFib.

“Their results are just more precise because of the larger sample size. That’s why they were able to show those associations,” said Dr. Conen, who was senior author on the earlier report, which covered a pooled analysis of 3,852 patients with AFib in the BEAT-AF and SWISS-AF cohort studies. It was published January 25 in CMAJ, with lead author Philipp Reddiess, MD, Cardiovascular Research Institute Basel, Switzerland.

The two published studies contrast in other ways that are worth noting and together suggest the stroke rate might have been 1% in both by chance, Dr. Conen said. “The populations were pretty different.”

In the earlier study, for example, the overwhelmingly European patients had more comorbidities and had been in AFib for much longer; their mean age was 71 years; and 84% were on oral anticoagulation (OAC).

In contrast, the Korean cohort averaged 61 years in age and only about 24% were taking oral anticoagulants. Given their distribution of CHA2DS2-VASc scores and mean score of 2.3, more than twice as many should have been on OAC, Dr. Conen speculated. “Even if you take into account that some patients may have contraindications, this is clearly an underanticoagulated population.”

The European cohort might have been “a little bit more representative because atrial fibrillation is a disease of the elderly,” Dr. Conen said, but “the Korean paper has the advantage of being a population-based study.”

It involved 97,869 patients from a Korean national data base who were newly diagnosed with AFib from 2010 to 2016. Of the total, 49,781 (51%) were continuously nondrinkers before and after their diagnosis; 12,789 (13%) abstained from alcohol only after their AFib diagnosis; and 35,299 (36%) were drinkers during the follow-up, either because they continued to drink or newly started after their diagnosis.

Of the cohort, 3,120 were diagnosed with new ischemic stroke over a follow-up of 310,926 person-years, for a rate of 1 per 100 person-years.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for ischemic stroke over a 5-year follow-up, compared with nondrinkers, was:

- 1.127 (95% confidence interval, 1.003-1.266) among abstainers

- 1.280 (95% CI, 1.166-1.405) for current drinkers

The corresponding HR, compared with current drinkers, was:

- 0.781 (95% CI, 0.712-0.858) for nondrinkers

- 0.880 (95% CI, 0.782-0.990) among abstainers

No significant interactions with ischemic stroke risk were observed in groups by sex, age, CHA2DS2-VASc score, or smoking status. The risk rose consistently with current drinking levels.

The overall stroke rate of 1% per year is “very low,” and “the absolute differences are small, even though there is a clear significant trend from nondrinking to drinking,” Dr. Conen said.

However, “the difference becomes more sizable when you compare heavy drinking to abstinence.”

Dr. Lee reports no conflicts of interest; disclosures for the other authors are in their report. Dr. Conen reports receiving speaker fees from Servier Canada; disclosures for the other authors are in their report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Are left atrial thrombi that defy preprocedure anticoagulation predictable?

Three or more weeks of oral anticoagulation (OAC) sometimes isn’t up to the job of clearing any potentially embolic left atrial (LA) thrombi before procedures like cardioversion or catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Such OAC-defiant LA thrombi aren’t common, nor are they rare enough to ignore, suggests a new meta-analysis that might also have identified features that predispose to them.

Such predictors of LA clots that persist despite OAC could potentially guide selective use of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) instead of more routine policies to either use or not use TEE for thrombus rule-out before rhythm-control procedures, researchers propose.

Their prevalence was about 2.7% among the study’s more than 14,000 patients who received at least 3 weeks of OAC with either vitamin K antagonists (VKA) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) before undergoing TEE.

But OAC-resistant LA thrombi were two- to four-times as common in patients with than without certain features, including AF other than paroxysmal and higher CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc stroke risk-stratification scores.

“TEE imaging in select patients at an elevated risk of LA thrombus, despite anticoagulation status, may be a reasonable approach to minimize the risk of thromboembolic complications following cardioversion or catheter ablation,” propose the study’s authors, led by Antony Lurie, BMSC, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont. Their report was published in the June 15 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Guidelines don’t encourage TEE before cardioversion in patients who have been on OAC for at least 3 weeks, the group notes, and policies on TEE use before AF ablation vary widely regardless of anticoagulation status.

The current study suggests that 3 weeks of OAC isn’t enough for a substantial number of patients, who might be put at thromboembolic risk if TEE were to be skipped before rhythm-control procedures.

Conversely, many patients unlikely to have LA thrombi get preprocedure TEE anyway. That can happen “irrespective of how long they’ve been anticoagulated, their pattern of atrial fibrillation, or their stroke risk,” senior author Jorge A. Wong, MD, MPH, Population Health Research Institute and McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., told this news organization.

But “TEE is an invasive imaging modality, so it is associated with small element of risk.” The current study, Dr. Wong said, points to potential risk-stratification tools clinicians might use to guide more selective TEE screening.

“At sites where TEEs are done all the time for patients undergoing ablation, one could use several of these risk markers to perhaps tailor use of TEE in individuals,” Dr. Wong said. “For example, in people with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, we found that the risk of left atrial appendage clot was approximately 1% or less.” Screening by TEE might reasonably be avoided in such patients.

“Fortunately, continued oral anticoagulation already yields low peri-procedural stroke rates,” observes an accompanying editorial from Paulus Kirchhof, MD, and Christoph Sinning, MD, from the University Heart & Vascular Center and German Centre of Cardiovascular Research, Hamburg.

“Based on this new analysis of existing data, a risk-based use of TEE imaging in anticoagulated patients could enable further improvement in the safe delivery of rhythm control interventions in patients with AF,” the editorialists agree.

The meta-analysis covered 10 prospective and 25 retrospective studies with a total of 14,653 patients that reported whether LA thrombus was present in patients with AF or atrial flutter (AFL) who underwent TEE after at least 3 weeks of VKA or DOAC therapy. Reports for 30 of the studies identified patients by rhythm-control procedure, and the remaining five didn’t specify TEE indications.

The weighted mean prevalence of LA thrombus at TEE was 2.73% (95% confidence interval, 1.95%-3.80%). The finding was not significantly changed in separate sensitivity analyses, the report says, including one limited to studies with low risk of bias and others excluding patients with valvular AF, interrupted OAC, heparin bridging, or subtherapeutic anticoagulation, respectively.

Patients treated with VKA and DOACs showed similar prevalences of LA thrombi, with means of 2.80% and 3.12%, respectively (P = .674). The prevalence was significantly higher in patients:

- with nonparoxysmal than with paroxysmal AF/AFL (4.81% vs. 1.03%; P < .001)

- undergoing cardioversion than ablation (5.55% vs. 1.65; P < .001)

- with CHA2DS2-VASc scores of at least 3 than with scores of 2 or less (6.31% vs. 1.06%; P < .001).

A limitation of the study, observe Dr. Kirchhof and Dr. Sinning, “is that all patients had a clinical indication for a TEE, which might be a selection bias. When a thrombus was found on TEE, clinical judgment led to postponing of the procedure,” thereby avoiding potential thromboembolism.

“Thus, the paper cannot demonstrate that presence of a thrombus on TEE is related to peri-procedural ischemic stroke,” they write.

The literature puts the risk for stroke or systemic embolism at well under 1% for patients anticoagulated with either VKA or DOACs for at least 3 weeks prior to cardioversion, in contrast to the nearly 3% prevalence of LA appendage thrombus by TEE in the current analysis, Dr. Wong observed.

“So we’re seeing a lot more left atrial appendage thrombus than we would see stroke,” but there wasn’t a way to determine whether that increases the stroke risk, he agreed.Dr. Wong, Dr. Lurie, and the other authors report no relevant conflicts. Dr. Kirchhof discloses receiving partial support “from several drug and device companies active in atrial fibrillation” and to being listed as inventor on two AF-related patents held by the University of Birmingham. Dr. Sinning reports no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Three or more weeks of oral anticoagulation (OAC) sometimes isn’t up to the job of clearing any potentially embolic left atrial (LA) thrombi before procedures like cardioversion or catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Such OAC-defiant LA thrombi aren’t common, nor are they rare enough to ignore, suggests a new meta-analysis that might also have identified features that predispose to them.

Such predictors of LA clots that persist despite OAC could potentially guide selective use of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) instead of more routine policies to either use or not use TEE for thrombus rule-out before rhythm-control procedures, researchers propose.

Their prevalence was about 2.7% among the study’s more than 14,000 patients who received at least 3 weeks of OAC with either vitamin K antagonists (VKA) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) before undergoing TEE.

But OAC-resistant LA thrombi were two- to four-times as common in patients with than without certain features, including AF other than paroxysmal and higher CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc stroke risk-stratification scores.

“TEE imaging in select patients at an elevated risk of LA thrombus, despite anticoagulation status, may be a reasonable approach to minimize the risk of thromboembolic complications following cardioversion or catheter ablation,” propose the study’s authors, led by Antony Lurie, BMSC, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont. Their report was published in the June 15 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Guidelines don’t encourage TEE before cardioversion in patients who have been on OAC for at least 3 weeks, the group notes, and policies on TEE use before AF ablation vary widely regardless of anticoagulation status.

The current study suggests that 3 weeks of OAC isn’t enough for a substantial number of patients, who might be put at thromboembolic risk if TEE were to be skipped before rhythm-control procedures.

Conversely, many patients unlikely to have LA thrombi get preprocedure TEE anyway. That can happen “irrespective of how long they’ve been anticoagulated, their pattern of atrial fibrillation, or their stroke risk,” senior author Jorge A. Wong, MD, MPH, Population Health Research Institute and McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., told this news organization.

But “TEE is an invasive imaging modality, so it is associated with small element of risk.” The current study, Dr. Wong said, points to potential risk-stratification tools clinicians might use to guide more selective TEE screening.

“At sites where TEEs are done all the time for patients undergoing ablation, one could use several of these risk markers to perhaps tailor use of TEE in individuals,” Dr. Wong said. “For example, in people with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, we found that the risk of left atrial appendage clot was approximately 1% or less.” Screening by TEE might reasonably be avoided in such patients.

“Fortunately, continued oral anticoagulation already yields low peri-procedural stroke rates,” observes an accompanying editorial from Paulus Kirchhof, MD, and Christoph Sinning, MD, from the University Heart & Vascular Center and German Centre of Cardiovascular Research, Hamburg.

“Based on this new analysis of existing data, a risk-based use of TEE imaging in anticoagulated patients could enable further improvement in the safe delivery of rhythm control interventions in patients with AF,” the editorialists agree.

The meta-analysis covered 10 prospective and 25 retrospective studies with a total of 14,653 patients that reported whether LA thrombus was present in patients with AF or atrial flutter (AFL) who underwent TEE after at least 3 weeks of VKA or DOAC therapy. Reports for 30 of the studies identified patients by rhythm-control procedure, and the remaining five didn’t specify TEE indications.

The weighted mean prevalence of LA thrombus at TEE was 2.73% (95% confidence interval, 1.95%-3.80%). The finding was not significantly changed in separate sensitivity analyses, the report says, including one limited to studies with low risk of bias and others excluding patients with valvular AF, interrupted OAC, heparin bridging, or subtherapeutic anticoagulation, respectively.

Patients treated with VKA and DOACs showed similar prevalences of LA thrombi, with means of 2.80% and 3.12%, respectively (P = .674). The prevalence was significantly higher in patients:

- with nonparoxysmal than with paroxysmal AF/AFL (4.81% vs. 1.03%; P < .001)

- undergoing cardioversion than ablation (5.55% vs. 1.65; P < .001)

- with CHA2DS2-VASc scores of at least 3 than with scores of 2 or less (6.31% vs. 1.06%; P < .001).

A limitation of the study, observe Dr. Kirchhof and Dr. Sinning, “is that all patients had a clinical indication for a TEE, which might be a selection bias. When a thrombus was found on TEE, clinical judgment led to postponing of the procedure,” thereby avoiding potential thromboembolism.

“Thus, the paper cannot demonstrate that presence of a thrombus on TEE is related to peri-procedural ischemic stroke,” they write.

The literature puts the risk for stroke or systemic embolism at well under 1% for patients anticoagulated with either VKA or DOACs for at least 3 weeks prior to cardioversion, in contrast to the nearly 3% prevalence of LA appendage thrombus by TEE in the current analysis, Dr. Wong observed.

“So we’re seeing a lot more left atrial appendage thrombus than we would see stroke,” but there wasn’t a way to determine whether that increases the stroke risk, he agreed.Dr. Wong, Dr. Lurie, and the other authors report no relevant conflicts. Dr. Kirchhof discloses receiving partial support “from several drug and device companies active in atrial fibrillation” and to being listed as inventor on two AF-related patents held by the University of Birmingham. Dr. Sinning reports no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Three or more weeks of oral anticoagulation (OAC) sometimes isn’t up to the job of clearing any potentially embolic left atrial (LA) thrombi before procedures like cardioversion or catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). Such OAC-defiant LA thrombi aren’t common, nor are they rare enough to ignore, suggests a new meta-analysis that might also have identified features that predispose to them.

Such predictors of LA clots that persist despite OAC could potentially guide selective use of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) instead of more routine policies to either use or not use TEE for thrombus rule-out before rhythm-control procedures, researchers propose.

Their prevalence was about 2.7% among the study’s more than 14,000 patients who received at least 3 weeks of OAC with either vitamin K antagonists (VKA) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) before undergoing TEE.

But OAC-resistant LA thrombi were two- to four-times as common in patients with than without certain features, including AF other than paroxysmal and higher CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc stroke risk-stratification scores.

“TEE imaging in select patients at an elevated risk of LA thrombus, despite anticoagulation status, may be a reasonable approach to minimize the risk of thromboembolic complications following cardioversion or catheter ablation,” propose the study’s authors, led by Antony Lurie, BMSC, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont. Their report was published in the June 15 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Guidelines don’t encourage TEE before cardioversion in patients who have been on OAC for at least 3 weeks, the group notes, and policies on TEE use before AF ablation vary widely regardless of anticoagulation status.

The current study suggests that 3 weeks of OAC isn’t enough for a substantial number of patients, who might be put at thromboembolic risk if TEE were to be skipped before rhythm-control procedures.

Conversely, many patients unlikely to have LA thrombi get preprocedure TEE anyway. That can happen “irrespective of how long they’ve been anticoagulated, their pattern of atrial fibrillation, or their stroke risk,” senior author Jorge A. Wong, MD, MPH, Population Health Research Institute and McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., told this news organization.

But “TEE is an invasive imaging modality, so it is associated with small element of risk.” The current study, Dr. Wong said, points to potential risk-stratification tools clinicians might use to guide more selective TEE screening.

“At sites where TEEs are done all the time for patients undergoing ablation, one could use several of these risk markers to perhaps tailor use of TEE in individuals,” Dr. Wong said. “For example, in people with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, we found that the risk of left atrial appendage clot was approximately 1% or less.” Screening by TEE might reasonably be avoided in such patients.

“Fortunately, continued oral anticoagulation already yields low peri-procedural stroke rates,” observes an accompanying editorial from Paulus Kirchhof, MD, and Christoph Sinning, MD, from the University Heart & Vascular Center and German Centre of Cardiovascular Research, Hamburg.

“Based on this new analysis of existing data, a risk-based use of TEE imaging in anticoagulated patients could enable further improvement in the safe delivery of rhythm control interventions in patients with AF,” the editorialists agree.

The meta-analysis covered 10 prospective and 25 retrospective studies with a total of 14,653 patients that reported whether LA thrombus was present in patients with AF or atrial flutter (AFL) who underwent TEE after at least 3 weeks of VKA or DOAC therapy. Reports for 30 of the studies identified patients by rhythm-control procedure, and the remaining five didn’t specify TEE indications.

The weighted mean prevalence of LA thrombus at TEE was 2.73% (95% confidence interval, 1.95%-3.80%). The finding was not significantly changed in separate sensitivity analyses, the report says, including one limited to studies with low risk of bias and others excluding patients with valvular AF, interrupted OAC, heparin bridging, or subtherapeutic anticoagulation, respectively.

Patients treated with VKA and DOACs showed similar prevalences of LA thrombi, with means of 2.80% and 3.12%, respectively (P = .674). The prevalence was significantly higher in patients:

- with nonparoxysmal than with paroxysmal AF/AFL (4.81% vs. 1.03%; P < .001)

- undergoing cardioversion than ablation (5.55% vs. 1.65; P < .001)

- with CHA2DS2-VASc scores of at least 3 than with scores of 2 or less (6.31% vs. 1.06%; P < .001).

A limitation of the study, observe Dr. Kirchhof and Dr. Sinning, “is that all patients had a clinical indication for a TEE, which might be a selection bias. When a thrombus was found on TEE, clinical judgment led to postponing of the procedure,” thereby avoiding potential thromboembolism.

“Thus, the paper cannot demonstrate that presence of a thrombus on TEE is related to peri-procedural ischemic stroke,” they write.

The literature puts the risk for stroke or systemic embolism at well under 1% for patients anticoagulated with either VKA or DOACs for at least 3 weeks prior to cardioversion, in contrast to the nearly 3% prevalence of LA appendage thrombus by TEE in the current analysis, Dr. Wong observed.

“So we’re seeing a lot more left atrial appendage thrombus than we would see stroke,” but there wasn’t a way to determine whether that increases the stroke risk, he agreed.Dr. Wong, Dr. Lurie, and the other authors report no relevant conflicts. Dr. Kirchhof discloses receiving partial support “from several drug and device companies active in atrial fibrillation” and to being listed as inventor on two AF-related patents held by the University of Birmingham. Dr. Sinning reports no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Novel rehab program fights frailty, boosts capacity in advanced HF

A novel physical rehabilitation program for patients with advanced heart failure that aimed to improve their ability to exercise before focusing on endurance was successful in a randomized trial in ways that seem to have eluded some earlier exercise-training studies in the setting of HF.

The often-frail patients following the training regimen, initiated before discharge from hospitalization for acute decompensation, worked on capabilities such as mobility, balance, and strength deemed necessary if exercises meant to build exercise capacity were to succeed.

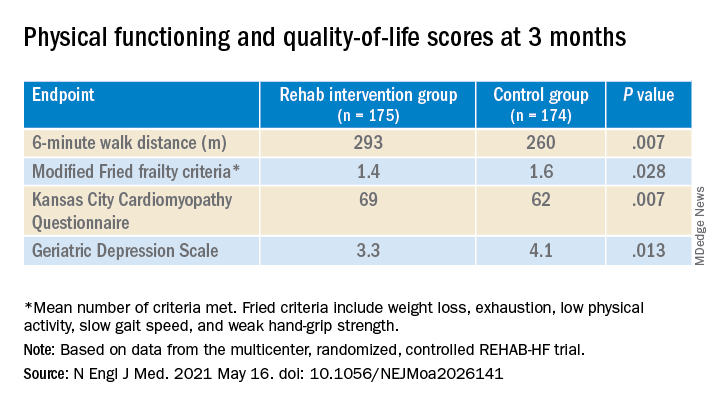

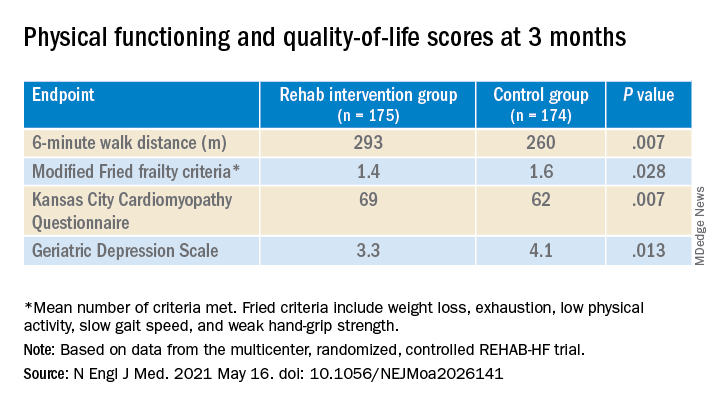

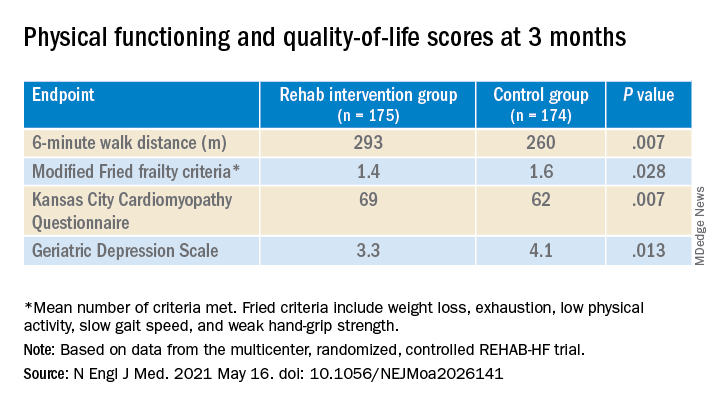

A huge percentage stayed with the 12-week program, which featured personalized, one-on-one training from a physical therapist. The patients benefited, with improvements in balance, walking ability, and strength, which were followed by significant gains in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and measures of physical functioning, frailty, and quality of life. The patients then continued elements of the program at home out to 6 months.

At that time, death and rehospitalizations did not differ between those assigned to the regimen and similar patients who had not participated in the program, although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical events.

The rehab strategy seemed to work across a wide range of patient subgroups. In particular, there was evidence that the benefits were more pronounced in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), observed Dalane W. Kitzman, MD, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Kitzman presented results from the REHAB-HF (Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and is lead author on its same-day publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An earlier pilot program unexpectedly showed that such patients recently hospitalized with HF “have significant impairments in mobility and balance,” he explained. If so, “it would be hazardous to subject them to traditional endurance training, such as walking-based treadmill or even bicycle.”

The unusual program, said Dr. Kitzman, looks to those issues before engaging the patients in endurance exercise by addressing mobility, balance, and basic strength – enough to repeatedly stand up from a sitting position, for example. “If you’re not able to stand with confidence, then you’re not able to walk on a treadmill.”

This model of exercise rehab “is used in geriatrics research, and enables them to safely increase endurance. It’s well known from geriatric studies that if you go directly to endurance in these, frail, older patients, you have little improvement and often have injuries and falls,” he added.

Guidance from telemedicine?

The functional outcomes examined in REHAB-HF “are the ones that matter to patients the most,” observed Eileen M. Handberg, PhD, of Shands Hospital at the University of Florida, Gainesville, at a presentation on the trial for the media.

“This is about being able to get out of a chair without assistance, not falling, walking farther, and feeling better as opposed to the more traditional outcome measure that has been used in cardiac rehab trials, which has been the exercise treadmill test – which most patients don’t have the capacity to do very well anyway,” said Dr. Handberg, who is not a part of REHAB-HF.

“This opens up rehab, potentially, to the more sick, who also need a better quality of life,” she said.

However, many patients invited to participate in the trial could not because they lived too far from the program, Dr. Handberg observed. “It would be nice to see if the lessons from COVID-19 might apply to this population” by making participation possible remotely, “perhaps using family members as rehab assistance,” she said.

“I was really very impressed that you had 83% adherence to a home exercise 6 months down the road, which far eclipses what we had in HF-ACTION,” said Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, as the invited discussant following Dr. Kitzman’s formal presentation of the trial. “And it certainly eclipses what we see in the typical cardiac rehab program.”

Both Dr. Bittner and Dr. Kitzman participated in HF-ACTION, a randomized exercise-training trial for patients with chronic, stable HFrEF who were all-around less sick than those in REHAB-HF.

Four functional domains

Historically, HF exercise or rehab trials have excluded patients hospitalized with acute decompensation, and third-party reimbursement often has not covered such programs because of a lack of supporting evidence and a supposed potential for harm, Dr. Kitzman said.

Entry to REHAB-HF required the patients to be fit enough to walk 4 meters, with or without a walker or other assistant device, and to have been in the hospital for at least 24 hours with a primary diagnosis of acute decompensated HF.

The intervention relied on exercises aimed at improving the four functional domains of strength, balance, mobility, and – when those three were sufficiently developed – endurance, Dr. Kitzman and associates wrote in their published report.

“The intervention was initiated in the hospital when feasible and was subsequently transitioned to an outpatient facility as soon as possible after discharge,” they wrote. Afterward, “a key goal of the intervention during the first 3 months [the outpatient phase] was to prepare the patient to transition to the independent maintenance phase (months 4-6).”

The study’s control patients “received frequent calls from study staff to try to approximate the increased attention received by the intervention group,” Dr. Kitzman said in an interview. “They were allowed to receive all usual care as ordered by their treating physicians. This included, if ordered, standard physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation” in 43% of the control cohort. Of the trial’s 349 patients, those assigned to the intervention scored significantly higher on the three-component Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) at 12 weeks than those assigned to a usual care approach that included, for some, more conventional cardiac rehabilitation (8.3 vs. 6.9; P < .001).

The SPPB, validated in trials as a proxy for clinical outcomes includes tests of balance while standing, gait speed during a 4-minute walk, and strength. The latter is the test that measures time needed to rise from a chair five times.

They also showed consistent gains in other measures of physical functioning and quality of life by 12 weeks months.

The observed SPPB treatment effect is “impressive” and “compares very favorably with previously reported estimates,” observed an accompanying editorial from Stefan D. Anker, MD, PhD, of the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, and Andrew J.S. Coats, DM, of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

“Similarly, the between-group differences seen in 6-minute walk distance (34 m) and gait speed (0.12 m/s) are clinically meaningful and sizable.”

They propose that some of the substantial quality-of-life benefit in the intervention group “may be due to better physical performance, and that part may be due to improvements in psychosocial factors and mood. It appears that exercise also resulted in patients becoming happier, or at least less depressed, as evidenced by the positive results on the Geriatric Depression Scale.”

Similar results across most subgroups

In subgroup analyses, the intervention was successful against the standard-care approach in both men and women at all ages and regardless of ejection fraction; symptom status; and whether the patient had diabetes, ischemic heart disease, or atrial fibrillation, or was obese.

Clinical outcomes were not significantly different at 6 months. The rate of death from any cause was 13% for the intervention group and 10% for the control group. There were 194 and 213 hospitalizations from any cause, respectively.

Not included in the trial’s current publication but soon to be published, Dr. Kitzman said when interviewed, is a comparison of outcomes in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF. “We found at baseline that those with HFpEF had worse impairment in physical function, quality of life, and frailty. After the intervention, there appeared to be consistently larger improvements in all outcomes, including SPPB, 6-minute walk, qualify of life, and frailty, in HFpEF versus HFrEF.”

The signals of potential benefit in HFpEF extended to clinical endpoints, he said. In contrast to similar rates of all-cause rehospitalization in HFrEF, “in patients with HFpEF, rehospitalizations were 17% lower in the intervention group, compared to the control group.” Still, he noted, the interaction P value wasn’t significant.

However, Dr. Kitzman added, mortality in the intervention group, compared with the control group, was reduced by 35% among patients with HFpEF, “but was 250% higher in HFrEF,” with a significant interaction P value.

He was careful to note that, as a phase 2 trial, REHAB-HF was underpowered for clinical events, “and even the results in the HFpEF group should not be seen as adequate evidence to change clinical care.” They were from an exploratory analysis that included relatively few events.

“Because definitive demonstration of improvement in clinical events is critical for altering clinical care guidelines and for third-party payer reimbursement decisions, we believe that a subsequent phase 3 trial is needed and are currently planning toward that,” Dr. Kitzman said.

The study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Kermit Glenn Phillips II Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, and the Oristano Family Fund at Wake Forest. Dr. Kitzman disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corviamedical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and having an unspecified relationship with Gilead. Dr. Handberg disclosed receiving grants from Aastom Biosciences, Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Amorcyte, AstraZeneca, Biocardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Capricor, Cytori Therapeutics, Department of Defense, Direct Flow Medical, Everyfit, Gilead, Ionis, Medtronic, Merck, Mesoblast, Relypsa, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Bittner discloses receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Pfizer and Sanofi; receiving research grants from Amgen and The Medicines Company; and having unspecified relationships with AstraZeneca, DalCor, Esperion, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Anker reported receiving grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular and Vifor; personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier, Cardiac Dimensions, Thermo Fisher Scientific, AstraZeneca, Occlutech, Actimed, and Respicardia. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Servier, Vifor, Abbott, Actimed, Arena, Cardiac Dimensions, Corvia, CVRx, Enopace, ESN Cleer, Faraday, WL Gore, Impulse Dynamics, and Respicardia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel physical rehabilitation program for patients with advanced heart failure that aimed to improve their ability to exercise before focusing on endurance was successful in a randomized trial in ways that seem to have eluded some earlier exercise-training studies in the setting of HF.

The often-frail patients following the training regimen, initiated before discharge from hospitalization for acute decompensation, worked on capabilities such as mobility, balance, and strength deemed necessary if exercises meant to build exercise capacity were to succeed.

A huge percentage stayed with the 12-week program, which featured personalized, one-on-one training from a physical therapist. The patients benefited, with improvements in balance, walking ability, and strength, which were followed by significant gains in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and measures of physical functioning, frailty, and quality of life. The patients then continued elements of the program at home out to 6 months.

At that time, death and rehospitalizations did not differ between those assigned to the regimen and similar patients who had not participated in the program, although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical events.

The rehab strategy seemed to work across a wide range of patient subgroups. In particular, there was evidence that the benefits were more pronounced in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), observed Dalane W. Kitzman, MD, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Kitzman presented results from the REHAB-HF (Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and is lead author on its same-day publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An earlier pilot program unexpectedly showed that such patients recently hospitalized with HF “have significant impairments in mobility and balance,” he explained. If so, “it would be hazardous to subject them to traditional endurance training, such as walking-based treadmill or even bicycle.”

The unusual program, said Dr. Kitzman, looks to those issues before engaging the patients in endurance exercise by addressing mobility, balance, and basic strength – enough to repeatedly stand up from a sitting position, for example. “If you’re not able to stand with confidence, then you’re not able to walk on a treadmill.”

This model of exercise rehab “is used in geriatrics research, and enables them to safely increase endurance. It’s well known from geriatric studies that if you go directly to endurance in these, frail, older patients, you have little improvement and often have injuries and falls,” he added.

Guidance from telemedicine?

The functional outcomes examined in REHAB-HF “are the ones that matter to patients the most,” observed Eileen M. Handberg, PhD, of Shands Hospital at the University of Florida, Gainesville, at a presentation on the trial for the media.

“This is about being able to get out of a chair without assistance, not falling, walking farther, and feeling better as opposed to the more traditional outcome measure that has been used in cardiac rehab trials, which has been the exercise treadmill test – which most patients don’t have the capacity to do very well anyway,” said Dr. Handberg, who is not a part of REHAB-HF.

“This opens up rehab, potentially, to the more sick, who also need a better quality of life,” she said.

However, many patients invited to participate in the trial could not because they lived too far from the program, Dr. Handberg observed. “It would be nice to see if the lessons from COVID-19 might apply to this population” by making participation possible remotely, “perhaps using family members as rehab assistance,” she said.

“I was really very impressed that you had 83% adherence to a home exercise 6 months down the road, which far eclipses what we had in HF-ACTION,” said Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, as the invited discussant following Dr. Kitzman’s formal presentation of the trial. “And it certainly eclipses what we see in the typical cardiac rehab program.”

Both Dr. Bittner and Dr. Kitzman participated in HF-ACTION, a randomized exercise-training trial for patients with chronic, stable HFrEF who were all-around less sick than those in REHAB-HF.

Four functional domains

Historically, HF exercise or rehab trials have excluded patients hospitalized with acute decompensation, and third-party reimbursement often has not covered such programs because of a lack of supporting evidence and a supposed potential for harm, Dr. Kitzman said.

Entry to REHAB-HF required the patients to be fit enough to walk 4 meters, with or without a walker or other assistant device, and to have been in the hospital for at least 24 hours with a primary diagnosis of acute decompensated HF.

The intervention relied on exercises aimed at improving the four functional domains of strength, balance, mobility, and – when those three were sufficiently developed – endurance, Dr. Kitzman and associates wrote in their published report.

“The intervention was initiated in the hospital when feasible and was subsequently transitioned to an outpatient facility as soon as possible after discharge,” they wrote. Afterward, “a key goal of the intervention during the first 3 months [the outpatient phase] was to prepare the patient to transition to the independent maintenance phase (months 4-6).”

The study’s control patients “received frequent calls from study staff to try to approximate the increased attention received by the intervention group,” Dr. Kitzman said in an interview. “They were allowed to receive all usual care as ordered by their treating physicians. This included, if ordered, standard physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation” in 43% of the control cohort. Of the trial’s 349 patients, those assigned to the intervention scored significantly higher on the three-component Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) at 12 weeks than those assigned to a usual care approach that included, for some, more conventional cardiac rehabilitation (8.3 vs. 6.9; P < .001).

The SPPB, validated in trials as a proxy for clinical outcomes includes tests of balance while standing, gait speed during a 4-minute walk, and strength. The latter is the test that measures time needed to rise from a chair five times.

They also showed consistent gains in other measures of physical functioning and quality of life by 12 weeks months.

The observed SPPB treatment effect is “impressive” and “compares very favorably with previously reported estimates,” observed an accompanying editorial from Stefan D. Anker, MD, PhD, of the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, and Andrew J.S. Coats, DM, of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

“Similarly, the between-group differences seen in 6-minute walk distance (34 m) and gait speed (0.12 m/s) are clinically meaningful and sizable.”

They propose that some of the substantial quality-of-life benefit in the intervention group “may be due to better physical performance, and that part may be due to improvements in psychosocial factors and mood. It appears that exercise also resulted in patients becoming happier, or at least less depressed, as evidenced by the positive results on the Geriatric Depression Scale.”

Similar results across most subgroups

In subgroup analyses, the intervention was successful against the standard-care approach in both men and women at all ages and regardless of ejection fraction; symptom status; and whether the patient had diabetes, ischemic heart disease, or atrial fibrillation, or was obese.

Clinical outcomes were not significantly different at 6 months. The rate of death from any cause was 13% for the intervention group and 10% for the control group. There were 194 and 213 hospitalizations from any cause, respectively.

Not included in the trial’s current publication but soon to be published, Dr. Kitzman said when interviewed, is a comparison of outcomes in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF. “We found at baseline that those with HFpEF had worse impairment in physical function, quality of life, and frailty. After the intervention, there appeared to be consistently larger improvements in all outcomes, including SPPB, 6-minute walk, qualify of life, and frailty, in HFpEF versus HFrEF.”

The signals of potential benefit in HFpEF extended to clinical endpoints, he said. In contrast to similar rates of all-cause rehospitalization in HFrEF, “in patients with HFpEF, rehospitalizations were 17% lower in the intervention group, compared to the control group.” Still, he noted, the interaction P value wasn’t significant.

However, Dr. Kitzman added, mortality in the intervention group, compared with the control group, was reduced by 35% among patients with HFpEF, “but was 250% higher in HFrEF,” with a significant interaction P value.

He was careful to note that, as a phase 2 trial, REHAB-HF was underpowered for clinical events, “and even the results in the HFpEF group should not be seen as adequate evidence to change clinical care.” They were from an exploratory analysis that included relatively few events.

“Because definitive demonstration of improvement in clinical events is critical for altering clinical care guidelines and for third-party payer reimbursement decisions, we believe that a subsequent phase 3 trial is needed and are currently planning toward that,” Dr. Kitzman said.

The study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Kermit Glenn Phillips II Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, and the Oristano Family Fund at Wake Forest. Dr. Kitzman disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corviamedical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and having an unspecified relationship with Gilead. Dr. Handberg disclosed receiving grants from Aastom Biosciences, Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Amorcyte, AstraZeneca, Biocardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Capricor, Cytori Therapeutics, Department of Defense, Direct Flow Medical, Everyfit, Gilead, Ionis, Medtronic, Merck, Mesoblast, Relypsa, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Bittner discloses receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Pfizer and Sanofi; receiving research grants from Amgen and The Medicines Company; and having unspecified relationships with AstraZeneca, DalCor, Esperion, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Anker reported receiving grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular and Vifor; personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier, Cardiac Dimensions, Thermo Fisher Scientific, AstraZeneca, Occlutech, Actimed, and Respicardia. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Servier, Vifor, Abbott, Actimed, Arena, Cardiac Dimensions, Corvia, CVRx, Enopace, ESN Cleer, Faraday, WL Gore, Impulse Dynamics, and Respicardia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel physical rehabilitation program for patients with advanced heart failure that aimed to improve their ability to exercise before focusing on endurance was successful in a randomized trial in ways that seem to have eluded some earlier exercise-training studies in the setting of HF.

The often-frail patients following the training regimen, initiated before discharge from hospitalization for acute decompensation, worked on capabilities such as mobility, balance, and strength deemed necessary if exercises meant to build exercise capacity were to succeed.

A huge percentage stayed with the 12-week program, which featured personalized, one-on-one training from a physical therapist. The patients benefited, with improvements in balance, walking ability, and strength, which were followed by significant gains in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and measures of physical functioning, frailty, and quality of life. The patients then continued elements of the program at home out to 6 months.

At that time, death and rehospitalizations did not differ between those assigned to the regimen and similar patients who had not participated in the program, although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical events.

The rehab strategy seemed to work across a wide range of patient subgroups. In particular, there was evidence that the benefits were more pronounced in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), observed Dalane W. Kitzman, MD, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Kitzman presented results from the REHAB-HF (Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and is lead author on its same-day publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An earlier pilot program unexpectedly showed that such patients recently hospitalized with HF “have significant impairments in mobility and balance,” he explained. If so, “it would be hazardous to subject them to traditional endurance training, such as walking-based treadmill or even bicycle.”

The unusual program, said Dr. Kitzman, looks to those issues before engaging the patients in endurance exercise by addressing mobility, balance, and basic strength – enough to repeatedly stand up from a sitting position, for example. “If you’re not able to stand with confidence, then you’re not able to walk on a treadmill.”

This model of exercise rehab “is used in geriatrics research, and enables them to safely increase endurance. It’s well known from geriatric studies that if you go directly to endurance in these, frail, older patients, you have little improvement and often have injuries and falls,” he added.

Guidance from telemedicine?

The functional outcomes examined in REHAB-HF “are the ones that matter to patients the most,” observed Eileen M. Handberg, PhD, of Shands Hospital at the University of Florida, Gainesville, at a presentation on the trial for the media.

“This is about being able to get out of a chair without assistance, not falling, walking farther, and feeling better as opposed to the more traditional outcome measure that has been used in cardiac rehab trials, which has been the exercise treadmill test – which most patients don’t have the capacity to do very well anyway,” said Dr. Handberg, who is not a part of REHAB-HF.

“This opens up rehab, potentially, to the more sick, who also need a better quality of life,” she said.

However, many patients invited to participate in the trial could not because they lived too far from the program, Dr. Handberg observed. “It would be nice to see if the lessons from COVID-19 might apply to this population” by making participation possible remotely, “perhaps using family members as rehab assistance,” she said.

“I was really very impressed that you had 83% adherence to a home exercise 6 months down the road, which far eclipses what we had in HF-ACTION,” said Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, as the invited discussant following Dr. Kitzman’s formal presentation of the trial. “And it certainly eclipses what we see in the typical cardiac rehab program.”

Both Dr. Bittner and Dr. Kitzman participated in HF-ACTION, a randomized exercise-training trial for patients with chronic, stable HFrEF who were all-around less sick than those in REHAB-HF.

Four functional domains

Historically, HF exercise or rehab trials have excluded patients hospitalized with acute decompensation, and third-party reimbursement often has not covered such programs because of a lack of supporting evidence and a supposed potential for harm, Dr. Kitzman said.

Entry to REHAB-HF required the patients to be fit enough to walk 4 meters, with or without a walker or other assistant device, and to have been in the hospital for at least 24 hours with a primary diagnosis of acute decompensated HF.

The intervention relied on exercises aimed at improving the four functional domains of strength, balance, mobility, and – when those three were sufficiently developed – endurance, Dr. Kitzman and associates wrote in their published report.

“The intervention was initiated in the hospital when feasible and was subsequently transitioned to an outpatient facility as soon as possible after discharge,” they wrote. Afterward, “a key goal of the intervention during the first 3 months [the outpatient phase] was to prepare the patient to transition to the independent maintenance phase (months 4-6).”

The study’s control patients “received frequent calls from study staff to try to approximate the increased attention received by the intervention group,” Dr. Kitzman said in an interview. “They were allowed to receive all usual care as ordered by their treating physicians. This included, if ordered, standard physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation” in 43% of the control cohort. Of the trial’s 349 patients, those assigned to the intervention scored significantly higher on the three-component Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) at 12 weeks than those assigned to a usual care approach that included, for some, more conventional cardiac rehabilitation (8.3 vs. 6.9; P < .001).

The SPPB, validated in trials as a proxy for clinical outcomes includes tests of balance while standing, gait speed during a 4-minute walk, and strength. The latter is the test that measures time needed to rise from a chair five times.

They also showed consistent gains in other measures of physical functioning and quality of life by 12 weeks months.

The observed SPPB treatment effect is “impressive” and “compares very favorably with previously reported estimates,” observed an accompanying editorial from Stefan D. Anker, MD, PhD, of the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, and Andrew J.S. Coats, DM, of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

“Similarly, the between-group differences seen in 6-minute walk distance (34 m) and gait speed (0.12 m/s) are clinically meaningful and sizable.”

They propose that some of the substantial quality-of-life benefit in the intervention group “may be due to better physical performance, and that part may be due to improvements in psychosocial factors and mood. It appears that exercise also resulted in patients becoming happier, or at least less depressed, as evidenced by the positive results on the Geriatric Depression Scale.”

Similar results across most subgroups

In subgroup analyses, the intervention was successful against the standard-care approach in both men and women at all ages and regardless of ejection fraction; symptom status; and whether the patient had diabetes, ischemic heart disease, or atrial fibrillation, or was obese.

Clinical outcomes were not significantly different at 6 months. The rate of death from any cause was 13% for the intervention group and 10% for the control group. There were 194 and 213 hospitalizations from any cause, respectively.

Not included in the trial’s current publication but soon to be published, Dr. Kitzman said when interviewed, is a comparison of outcomes in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF. “We found at baseline that those with HFpEF had worse impairment in physical function, quality of life, and frailty. After the intervention, there appeared to be consistently larger improvements in all outcomes, including SPPB, 6-minute walk, qualify of life, and frailty, in HFpEF versus HFrEF.”

The signals of potential benefit in HFpEF extended to clinical endpoints, he said. In contrast to similar rates of all-cause rehospitalization in HFrEF, “in patients with HFpEF, rehospitalizations were 17% lower in the intervention group, compared to the control group.” Still, he noted, the interaction P value wasn’t significant.

However, Dr. Kitzman added, mortality in the intervention group, compared with the control group, was reduced by 35% among patients with HFpEF, “but was 250% higher in HFrEF,” with a significant interaction P value.

He was careful to note that, as a phase 2 trial, REHAB-HF was underpowered for clinical events, “and even the results in the HFpEF group should not be seen as adequate evidence to change clinical care.” They were from an exploratory analysis that included relatively few events.

“Because definitive demonstration of improvement in clinical events is critical for altering clinical care guidelines and for third-party payer reimbursement decisions, we believe that a subsequent phase 3 trial is needed and are currently planning toward that,” Dr. Kitzman said.

The study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Kermit Glenn Phillips II Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, and the Oristano Family Fund at Wake Forest. Dr. Kitzman disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corviamedical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and having an unspecified relationship with Gilead. Dr. Handberg disclosed receiving grants from Aastom Biosciences, Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Amorcyte, AstraZeneca, Biocardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Capricor, Cytori Therapeutics, Department of Defense, Direct Flow Medical, Everyfit, Gilead, Ionis, Medtronic, Merck, Mesoblast, Relypsa, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Bittner discloses receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Pfizer and Sanofi; receiving research grants from Amgen and The Medicines Company; and having unspecified relationships with AstraZeneca, DalCor, Esperion, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Anker reported receiving grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular and Vifor; personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier, Cardiac Dimensions, Thermo Fisher Scientific, AstraZeneca, Occlutech, Actimed, and Respicardia. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Servier, Vifor, Abbott, Actimed, Arena, Cardiac Dimensions, Corvia, CVRx, Enopace, ESN Cleer, Faraday, WL Gore, Impulse Dynamics, and Respicardia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fresh look at ISCHEMIA bolsters conservative message in stable CAD

The more complicated a primary endpoint, the greater a puzzle it can be for clinicians to interpret the results. It’s likely even tougher for patients, who don’t help choose the events studied in clinical trials yet are increasingly sharing in the management decisions they influence.

That creates an opening for a more patient-centered take on one of cardiology’s most influential recent studies, ISCHEMIA, which bolsters the case for conservative, med-oriented management over a more invasive initial strategy for patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and positive stress tests, researchers said.

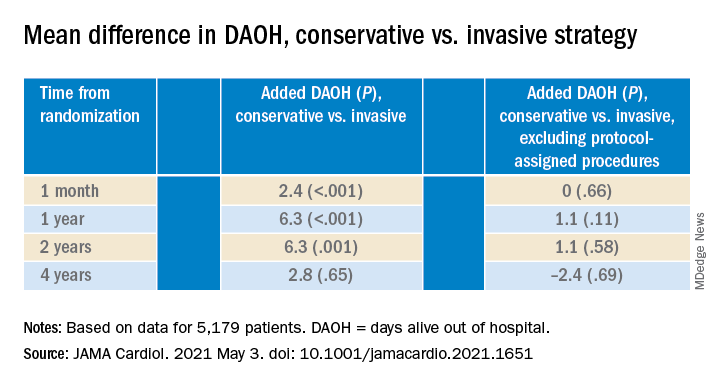

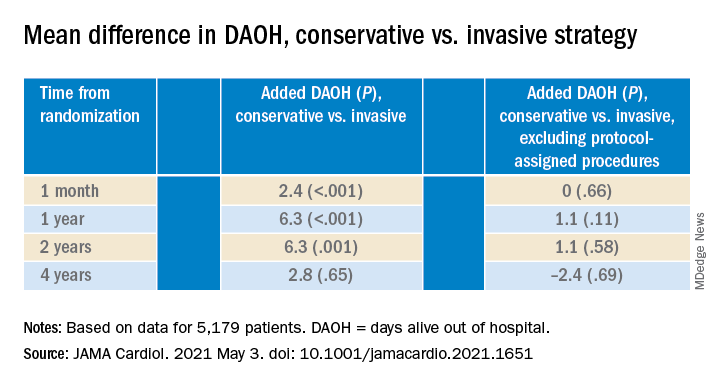

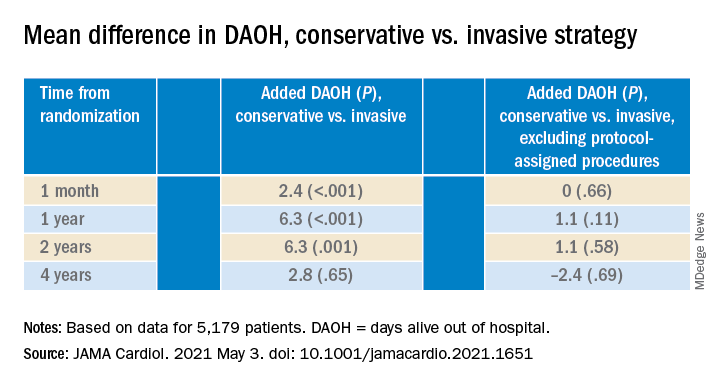

The new, prespecified analysis replaced the trial’s conventional primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) with one based on “days alive out of hospital” (DAOH) and found an early advantage for the conservative approach, with caveats.

Those assigned to the conservative arm benefited with more out-of-hospital days throughout the next 2 years than those in the invasive-management group, owing to the latter’s protocol-mandated early cath-lab work-up with possible revascularization. The difference averaged more than 6 days for much of that time.

But DAOH evened out for the two groups by the fourth year in the analysis of more than 5,000 patients.

Protocol-determined cath procedures accounted for 61% of hospitalizations in the invasively managed group. A secondary DAOH analysis that excluded such required hospital days, also prespecified, showed no meaningful difference between the two strategies over the 4 years, noted the report published online May 3 in JAMA Cardiology.

DOAH is ‘very, very important’

The DAOH metric has been a far less common consideration in clinical trials, compared with clinical events, yet in some ways it is as “hard” a metric as mortality, encompasses a broader range of outcomes, and may matter more to patients, it’s been argued.

“The thing patients most value is time at home. So they don’t want to be in the hospital, they don’t want to be away from friends, they want to do recreation, or they may want to work,” lead author Harvey D. White, DSc, Green Lane Cardiovascular Services, Auckland (New Zealand) City Hospital, University of Auckland, told this news organization.

“When we need to talk to patients – and we do need to talk to patients – to have a days-out-of-hospital metric is very, very important,” he said. It is not only patient focused, it’s “meaningful in terms of the seriousness of events,” in that length of hospitalization tracks with clinical severity, observed Dr. White, who is slated to present the analysis May 17 during the virtual American College of Cardiology 2021 scientific sessions.

As previously reported, ISCHEMIA showed no significant effect on the primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, MI, or hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest by assignment group over a median 3.2 years. Angina and quality of life measures were improved for patients in the invasive arm.

With an invasive initial strategy, “What we know now is that you get nothing of an advantage in terms of the composite endpoint, and you’re going to spend 6 days more in the hospital in the first 2 years, for largely no benefit,” Dr. White said.

That outlook may apply out to 4 years, the analysis suggests, but could conceivably change if DAOH is reassessed later as the ISCHEMIA follow-up continues for what is now a planned total of 10 years.

Meanwhile, the current findings could enhance doctor-patient discussions about the trade-offs between the two strategies for individuals whose considerations will vary.

“This is a very helpful measure to understand the burden of an approach to the patient,” observed E. Magnus Ohman, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who was not involved in the trial.

With DAOH as an endpoint, “you as a clinician get another aspect of understanding of a treatment’s impact on a multitude of endpoints.” Days out of hospital, he noted, encompasses the effects of clinical events that often go into composite clinical endpoints – not death, but including nonfatal MI, stroke, need for revascularization, and cardiovascular hospitalization.

To patients with stable CAD who ask whether the invasive approach has merits in their case, the DAOH finding “helps you to say, well, at the end of the day, you will probably be spending an equal amount of time in the hospital. Your price up front is a little bit higher, but over time, the group who gets conservative treatment will catch up.”

The DAOH outcome also avoids the limitations of an endpoint based on time to first event, “not the least of which,” said Dr. White, is that it counts only the first of what might be multiple events of varying clinical impact. Misleadingly, “you can have an event that’s a small troponin rise, but that becomes more important in a person than dying the next day.”

The DAOH analysis was based on 5,179 patients from 37 countries who averaged 64 years of age and of whom 23% were women. The endpoint considered only overnight stays in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes.

There were many more hospital or extended care facility stays overall in the invasive-management group, 4,002 versus 1,897 for those following the conservative strategy (P < .001), but the numbers flipped after excluding protocol-assigned procedures: 1,568 stays in the invasive group, compared with 1,897 (P = .001)

There were no associations between DAOH and Seattle Angina Questionnaire 7–Angina Frequency scores or DAOH interactions by age, sex, geographic region, or whether the patient had diabetes, prior MI, or heart failure, the report notes.

The primary ISCHEMIA analysis hinted at a possible long-term advantage for the invasive initial strategy in that event curves for the two arms crossed after 2-3 years, Dr. Ohman observed.

Based on that, for younger patients with stable CAD and ischemia at stress testing, “an investment of more hospital days early on might be worth it in the long run.” But ISCHEMIA, he said, “only suggests it, it doesn’t confirm it.”

The study was supported in part by grants from Arbor Pharmaceuticals and AstraZeneca. Devices or medications were provided by Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Arbor, AstraZeneca, Esperion, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Phillips, Omron Healthcare, and Sunovion. Dr. White disclosed receiving grants paid to his institution and fees for serving on a steering committee from Sanofi-Aventis, Regeneron, Eli Lilly, Omthera, American Regent, Eisai, DalCor, CSL Behring, Sanofi-Aventis Australia, and Esperion Therapeutics, and personal fees from Genentech and AstraZeneca. Dr. Ohman reported receiving grants from Abiomed and Cheisi USA, and consulting for Abiomed, Cara Therapeutics, Chiesi USA, Cytokinetics, Imbria Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, and XyloCor Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The more complicated a primary endpoint, the greater a puzzle it can be for clinicians to interpret the results. It’s likely even tougher for patients, who don’t help choose the events studied in clinical trials yet are increasingly sharing in the management decisions they influence.

That creates an opening for a more patient-centered take on one of cardiology’s most influential recent studies, ISCHEMIA, which bolsters the case for conservative, med-oriented management over a more invasive initial strategy for patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and positive stress tests, researchers said.

The new, prespecified analysis replaced the trial’s conventional primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) with one based on “days alive out of hospital” (DAOH) and found an early advantage for the conservative approach, with caveats.

Those assigned to the conservative arm benefited with more out-of-hospital days throughout the next 2 years than those in the invasive-management group, owing to the latter’s protocol-mandated early cath-lab work-up with possible revascularization. The difference averaged more than 6 days for much of that time.