User login

Obsessed with Facebook

CASE: Paranoid and online

Mr. M, age 22, is brought to the emergency department by family because they are concerned about his paranoia and increasing agitation related to Facebook posts by friends and siblings. At age 8, Mr. M was diagnosed with depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anger management problems, which were well controlled with fluoxetine until last year, when he discontinued psychiatric follow-up. Mr. M’s girlfriend ended their relationship 1 month ago, although it is unclear whether the break-up was caused by his depressive symptoms or exacerbated them. In the last 2 days, his parents have noticed an increase in his delusional thoughts and aggressive behavior.

Family psychiatric history is not significant. Five years ago, Mr. M suffered a head injury in a motor vehicle collision, but completed high school without evidence of cognitive impairment or behavioral changes.

Mr. M appears disheveled and irritable. He reports his mood as “depressed,” but denies suicidal or homicidal ideations. He has no history of violence or antisocial behavior.

Mr. M is alert and oriented with clear speech, intact language, and grossly intact memory and concentration—although, he admits, “I just obsess over certain thoughts.” He endorses feelings of anxiety, insomnia, low energy, lack of sleep secondary to his paranoia, and claims that “something was said on Facebook about a girl and everyone is in on it.” He explains that his Facebook friends talk in “analogies” about him, and reports that, “I can just tell that’s what they are talking about even if they don’t say it directly.”

a) impulse control disorder

b) brief psychotic episode

c) psychotic depression

d) bipolar disorder

The authors’ observations

The last decade has seen a rise in the creation and use of social networking sites such as Facebook, Myspace, and Twitter. Facebook has 1.15 billion monthly active users.1 Seventy-five percent of teenagers own cell phones, and 25% report using their phones to access social media outlets.2 More than 50% of teenagers visit a social networking site daily, with 22% logging in to their favorite social media network more than 10 times a day.3 The easy accessibility of social media outlets has prompted study of the association of that accessibility with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem.3-7

Although not a DSM-5 or ICD-10 diagnosis, internet addiction has been correlated with depression.8 Similarly, O’Keefe and colleagues describe Facebook depression in teens who spend a large amount of time on social networking sites.4 The recently developed Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS)9 evaluates the six core elements of addiction (salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse) in Facebook users.

Facebook certainly provides a valuable mechanism for friends to stay connected in an increasingly global society, and has acknowledged the potential it has to address mental illness. In 2011, Facebook partnered with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to allow users to report observed suicidal content, thereby utilizing the online community to facilitate delivery of mental health resources.10,11

HISTORY: Sibling rivalry

Mr. M had a romantic relationship with “Ms. B” in high school that he describes as “on and off,” beginning during his sophomore year. He describes himself as a “quick learner” who is task-oriented. He says he was outgoing in high school but became more introverted during his last year there. After high school, Mr. M worked as an electrician and discontinued psychiatric follow-up because he “felt fine.” He lives at home with his parents, two older sisters, and twin brother, who he identifies as being a lifelong “rival.”

After Ms. B ended her relationship with Mr. M, he began to suspect that she had become romantically involved with his twin brother. After Mr. M observed his brother leaving the house one night, he confronted his twin, who denied any involvement with Ms. B. After his brother left, Mr. M became enraged and punched a wall, fracturing his hand.

Two weeks before admission, Mr. M became increasingly preoccupied with suspicions of his brother’s involvement with Ms. B and looked for evidence on Facebook. Mr. M intensely monitored his Facebook news feed, which constantly updates to show public posts made by a user’s Facebook friends. He interpreted his friends’ posts as either directly relating to him or to a new relationship between Ms. B and his twin brother, stating that his friends were “talking in analogies” rather than directly using names.

Mr. M’s Facebook use rapidly increased to 3 or more hours a day. He can access Facebook from his laptop or cell phone, and reports logging in more than 10 times throughout the day. He says that, on Facebook, “it’s easier to talk trash” because people can say things they would not normally say face to face. He also states that Facebook is “ruining personal relationships,” and that it is “so easy to be in touch with everyone without really being in touch.”

The authors’ observations

In Mr. M’s case, Facebook served as a vehicle through which he could pursue a non-bizarre delusion. Mr. M openly admitted to viewing his twin brother as a rival; it is not surprising, therefore, that his delusions targeted his brother and ex-girlfriend.

Before social networks, the perseveration of this delusion might have been limited to internal thinking, or gathering corroborative information by means of stalking. Social media outlets have provided a means to perseverate and implicate others remotely, however, and Mr. M soon expanded his delusions to include more peers.

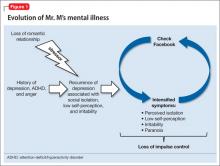

After beginning to suspect that friends and family are commenting on or criticizing him through Facebook, Mr. M experienced an irresistible impulse to repeatedly check the social network, which may have provided short-term relief of anticipatory anxiety, but that perpetuated the cycle. Constant access to the internet facilitated and intensified Mr. M’s cycle of paranoia, anxiety, and dysphoria. He called this process an “addiction.” A conceptual framework of the development of Mr. M’s maladaptive use of Facebook is illustrated in Figure 1.

Risk factors

Insecurity with one’s self-worth also may be a warning sign. Online social networking circumvents the need for physical interaction. A Facebook profile allows a person to selectively portray himself (herself) to the world, which may not be congruous with how his peers see him in everyday life. Patients who fear criticism or judgment may be more prone to maladaptive Facebook use, because they might feel empowered by the control they have over how others see them—online, at least.

Limited or, in Mr. M’s case, singular romantic experience may have influenced the course of his illness. Mr. M described his romantic involvement as a single, tumultuous relationship that lasted several years. Young patients with limited romantic experience may struggle to develop healthy protective mechanisms and may become preoccupied with the details of the situation, such that it interferes with functioning.

Mr. M’s history of ADHD might be a risk factor for abnormal patterns of internet use. Patients with ADHD have increased attentiveness with visually stimulating tasks—specifically, computers and video games.12

Last, it is unclear how, or if, Mr. M’s history of head injury contributed to his symptoms. There were no clear, temporal changes in cognition or emotion associated with the head injury, and he did not receive regular follow-up. Significant cognitive impairment does not appear to be a factor.

a) restart fluoxetine

b) begin an atypical antipsychotic

c) begin a mood stabilizer and atypical antipsychotic

d) encourage Mr. M to deactivate his Facebook account

TREATMENT: Observed use

Quetiapine is selected to target psychosis, agitation, and insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep initiation. Risperidone is added as a short-term agent to boost antipsychotic effect during the day when Mr. M is not fully responsive to quetiapine alone. Valproic acid is added on admission as a mood stabilizer to target emotional lability, impulsiveness, and possible mania.

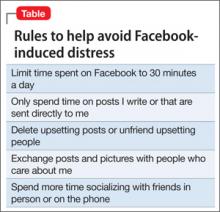

After several days of treatment, and without access to a computer, Mr. M is calmer. We begin to assess the challenges of self-limiting time spent on Facebook; Mr. M explains that, before hospitalization, he had deactivated his Facebook account several times to try to rid himself of what he describes as an “addiction to social media”; soon afterward, however, he experienced overwhelming anxiety that led him to reactivate his account.

We sit with Mr. M as he logs in to Facebook and discuss the range of alternative explanations that specific public messages on his news feed could have. Explicitly listing alternative explanations is a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Mr. M begins to demonstrate increased insight regarding his paranoia and possible misinterpretation of information gleaned via Facebook; however, he still believes that masked references to him had existed. During his hospital stay he begins to acknowledge the problems that online interactions pose compared with face-to-face interactions, stating that, “There’s no emotion in [Facebook], so you can easily misinterpret what someone says.”

The authors’ observations

Mr. M was discharged after 7 days of treatment and has been seen weekly as an outpatient for 3 months without need for further hospitalization.

Bottom Line

Pervasive access to social media represents a vehicle for relapse of many psychiatric conditions. Younger patients may be especially at risk because they are more likely to use social media and are in the age range for onset of psychiatric illness. Although some degree of dependence on online networks can be considered normal, patients suffering from mental illness represent a vulnerable population for maladaptive online interactions.

Related Resources

• Sandler EP. If you’re in crisis, go online. Psychology Today. www.psychologytoday.com/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201110/if-you-re-in-crisis-go-online. Published October 26, 2011.

• Nitzan U, Shoshan E, Lev-Ran S, et al. Internet-related psychosis−a sign of the times. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(3):207-211.

• Martin EA, Bailey DH, Cicero DC, et al. Social networking profile correlates of schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):641-646.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Facebook. Facebook reports second quarter 2013 results. http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID= 780093. Updated July 24, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2013.

2. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Offline consequences of online victimization: school violence and delinquency. Journal of School Violence. 2007;6(3):89-112.

3. Pantic I, Damjanovic A, Todorovic J, et al. Associations between online social networking and depression in high school students: behavioral physiology viewpoint. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(1):90-93.

4. O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K; Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):800-804.

5. Gonzales AL, Hancock JT. Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: effects of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(1-2):79-83.

6. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(3):206-221.

7. Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, et al. Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: the role of perceived friendship quality. J Adolesc. 2009;32(4):819-833.

8. Morrison CM, Gore H. The relationship between excessive internet use and depression: a questionnaire-based study of 1,319 young people and adults. Psychopathology. 2010; 43:121-126.

9. Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, et al. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501-517.

10. SAMHSA News. Suicide prevention: a national priority. vol 20, no 3. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012.

11. Facebook. New partnership between Facebook and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=310287485658707. Accessed July 25, 2013.

12. Weinstein A, Weizman A. Emerging association between addictive gaming and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(5):590-597.

CASE: Paranoid and online

Mr. M, age 22, is brought to the emergency department by family because they are concerned about his paranoia and increasing agitation related to Facebook posts by friends and siblings. At age 8, Mr. M was diagnosed with depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anger management problems, which were well controlled with fluoxetine until last year, when he discontinued psychiatric follow-up. Mr. M’s girlfriend ended their relationship 1 month ago, although it is unclear whether the break-up was caused by his depressive symptoms or exacerbated them. In the last 2 days, his parents have noticed an increase in his delusional thoughts and aggressive behavior.

Family psychiatric history is not significant. Five years ago, Mr. M suffered a head injury in a motor vehicle collision, but completed high school without evidence of cognitive impairment or behavioral changes.

Mr. M appears disheveled and irritable. He reports his mood as “depressed,” but denies suicidal or homicidal ideations. He has no history of violence or antisocial behavior.

Mr. M is alert and oriented with clear speech, intact language, and grossly intact memory and concentration—although, he admits, “I just obsess over certain thoughts.” He endorses feelings of anxiety, insomnia, low energy, lack of sleep secondary to his paranoia, and claims that “something was said on Facebook about a girl and everyone is in on it.” He explains that his Facebook friends talk in “analogies” about him, and reports that, “I can just tell that’s what they are talking about even if they don’t say it directly.”

a) impulse control disorder

b) brief psychotic episode

c) psychotic depression

d) bipolar disorder

The authors’ observations

The last decade has seen a rise in the creation and use of social networking sites such as Facebook, Myspace, and Twitter. Facebook has 1.15 billion monthly active users.1 Seventy-five percent of teenagers own cell phones, and 25% report using their phones to access social media outlets.2 More than 50% of teenagers visit a social networking site daily, with 22% logging in to their favorite social media network more than 10 times a day.3 The easy accessibility of social media outlets has prompted study of the association of that accessibility with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem.3-7

Although not a DSM-5 or ICD-10 diagnosis, internet addiction has been correlated with depression.8 Similarly, O’Keefe and colleagues describe Facebook depression in teens who spend a large amount of time on social networking sites.4 The recently developed Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS)9 evaluates the six core elements of addiction (salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse) in Facebook users.

Facebook certainly provides a valuable mechanism for friends to stay connected in an increasingly global society, and has acknowledged the potential it has to address mental illness. In 2011, Facebook partnered with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to allow users to report observed suicidal content, thereby utilizing the online community to facilitate delivery of mental health resources.10,11

HISTORY: Sibling rivalry

Mr. M had a romantic relationship with “Ms. B” in high school that he describes as “on and off,” beginning during his sophomore year. He describes himself as a “quick learner” who is task-oriented. He says he was outgoing in high school but became more introverted during his last year there. After high school, Mr. M worked as an electrician and discontinued psychiatric follow-up because he “felt fine.” He lives at home with his parents, two older sisters, and twin brother, who he identifies as being a lifelong “rival.”

After Ms. B ended her relationship with Mr. M, he began to suspect that she had become romantically involved with his twin brother. After Mr. M observed his brother leaving the house one night, he confronted his twin, who denied any involvement with Ms. B. After his brother left, Mr. M became enraged and punched a wall, fracturing his hand.

Two weeks before admission, Mr. M became increasingly preoccupied with suspicions of his brother’s involvement with Ms. B and looked for evidence on Facebook. Mr. M intensely monitored his Facebook news feed, which constantly updates to show public posts made by a user’s Facebook friends. He interpreted his friends’ posts as either directly relating to him or to a new relationship between Ms. B and his twin brother, stating that his friends were “talking in analogies” rather than directly using names.

Mr. M’s Facebook use rapidly increased to 3 or more hours a day. He can access Facebook from his laptop or cell phone, and reports logging in more than 10 times throughout the day. He says that, on Facebook, “it’s easier to talk trash” because people can say things they would not normally say face to face. He also states that Facebook is “ruining personal relationships,” and that it is “so easy to be in touch with everyone without really being in touch.”

The authors’ observations

In Mr. M’s case, Facebook served as a vehicle through which he could pursue a non-bizarre delusion. Mr. M openly admitted to viewing his twin brother as a rival; it is not surprising, therefore, that his delusions targeted his brother and ex-girlfriend.

Before social networks, the perseveration of this delusion might have been limited to internal thinking, or gathering corroborative information by means of stalking. Social media outlets have provided a means to perseverate and implicate others remotely, however, and Mr. M soon expanded his delusions to include more peers.

After beginning to suspect that friends and family are commenting on or criticizing him through Facebook, Mr. M experienced an irresistible impulse to repeatedly check the social network, which may have provided short-term relief of anticipatory anxiety, but that perpetuated the cycle. Constant access to the internet facilitated and intensified Mr. M’s cycle of paranoia, anxiety, and dysphoria. He called this process an “addiction.” A conceptual framework of the development of Mr. M’s maladaptive use of Facebook is illustrated in Figure 1.

Risk factors

Insecurity with one’s self-worth also may be a warning sign. Online social networking circumvents the need for physical interaction. A Facebook profile allows a person to selectively portray himself (herself) to the world, which may not be congruous with how his peers see him in everyday life. Patients who fear criticism or judgment may be more prone to maladaptive Facebook use, because they might feel empowered by the control they have over how others see them—online, at least.

Limited or, in Mr. M’s case, singular romantic experience may have influenced the course of his illness. Mr. M described his romantic involvement as a single, tumultuous relationship that lasted several years. Young patients with limited romantic experience may struggle to develop healthy protective mechanisms and may become preoccupied with the details of the situation, such that it interferes with functioning.

Mr. M’s history of ADHD might be a risk factor for abnormal patterns of internet use. Patients with ADHD have increased attentiveness with visually stimulating tasks—specifically, computers and video games.12

Last, it is unclear how, or if, Mr. M’s history of head injury contributed to his symptoms. There were no clear, temporal changes in cognition or emotion associated with the head injury, and he did not receive regular follow-up. Significant cognitive impairment does not appear to be a factor.

a) restart fluoxetine

b) begin an atypical antipsychotic

c) begin a mood stabilizer and atypical antipsychotic

d) encourage Mr. M to deactivate his Facebook account

TREATMENT: Observed use

Quetiapine is selected to target psychosis, agitation, and insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep initiation. Risperidone is added as a short-term agent to boost antipsychotic effect during the day when Mr. M is not fully responsive to quetiapine alone. Valproic acid is added on admission as a mood stabilizer to target emotional lability, impulsiveness, and possible mania.

After several days of treatment, and without access to a computer, Mr. M is calmer. We begin to assess the challenges of self-limiting time spent on Facebook; Mr. M explains that, before hospitalization, he had deactivated his Facebook account several times to try to rid himself of what he describes as an “addiction to social media”; soon afterward, however, he experienced overwhelming anxiety that led him to reactivate his account.

We sit with Mr. M as he logs in to Facebook and discuss the range of alternative explanations that specific public messages on his news feed could have. Explicitly listing alternative explanations is a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Mr. M begins to demonstrate increased insight regarding his paranoia and possible misinterpretation of information gleaned via Facebook; however, he still believes that masked references to him had existed. During his hospital stay he begins to acknowledge the problems that online interactions pose compared with face-to-face interactions, stating that, “There’s no emotion in [Facebook], so you can easily misinterpret what someone says.”

The authors’ observations

Mr. M was discharged after 7 days of treatment and has been seen weekly as an outpatient for 3 months without need for further hospitalization.

Bottom Line

Pervasive access to social media represents a vehicle for relapse of many psychiatric conditions. Younger patients may be especially at risk because they are more likely to use social media and are in the age range for onset of psychiatric illness. Although some degree of dependence on online networks can be considered normal, patients suffering from mental illness represent a vulnerable population for maladaptive online interactions.

Related Resources

• Sandler EP. If you’re in crisis, go online. Psychology Today. www.psychologytoday.com/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201110/if-you-re-in-crisis-go-online. Published October 26, 2011.

• Nitzan U, Shoshan E, Lev-Ran S, et al. Internet-related psychosis−a sign of the times. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(3):207-211.

• Martin EA, Bailey DH, Cicero DC, et al. Social networking profile correlates of schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):641-646.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Paranoid and online

Mr. M, age 22, is brought to the emergency department by family because they are concerned about his paranoia and increasing agitation related to Facebook posts by friends and siblings. At age 8, Mr. M was diagnosed with depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anger management problems, which were well controlled with fluoxetine until last year, when he discontinued psychiatric follow-up. Mr. M’s girlfriend ended their relationship 1 month ago, although it is unclear whether the break-up was caused by his depressive symptoms or exacerbated them. In the last 2 days, his parents have noticed an increase in his delusional thoughts and aggressive behavior.

Family psychiatric history is not significant. Five years ago, Mr. M suffered a head injury in a motor vehicle collision, but completed high school without evidence of cognitive impairment or behavioral changes.

Mr. M appears disheveled and irritable. He reports his mood as “depressed,” but denies suicidal or homicidal ideations. He has no history of violence or antisocial behavior.

Mr. M is alert and oriented with clear speech, intact language, and grossly intact memory and concentration—although, he admits, “I just obsess over certain thoughts.” He endorses feelings of anxiety, insomnia, low energy, lack of sleep secondary to his paranoia, and claims that “something was said on Facebook about a girl and everyone is in on it.” He explains that his Facebook friends talk in “analogies” about him, and reports that, “I can just tell that’s what they are talking about even if they don’t say it directly.”

a) impulse control disorder

b) brief psychotic episode

c) psychotic depression

d) bipolar disorder

The authors’ observations

The last decade has seen a rise in the creation and use of social networking sites such as Facebook, Myspace, and Twitter. Facebook has 1.15 billion monthly active users.1 Seventy-five percent of teenagers own cell phones, and 25% report using their phones to access social media outlets.2 More than 50% of teenagers visit a social networking site daily, with 22% logging in to their favorite social media network more than 10 times a day.3 The easy accessibility of social media outlets has prompted study of the association of that accessibility with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem.3-7

Although not a DSM-5 or ICD-10 diagnosis, internet addiction has been correlated with depression.8 Similarly, O’Keefe and colleagues describe Facebook depression in teens who spend a large amount of time on social networking sites.4 The recently developed Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS)9 evaluates the six core elements of addiction (salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse) in Facebook users.

Facebook certainly provides a valuable mechanism for friends to stay connected in an increasingly global society, and has acknowledged the potential it has to address mental illness. In 2011, Facebook partnered with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to allow users to report observed suicidal content, thereby utilizing the online community to facilitate delivery of mental health resources.10,11

HISTORY: Sibling rivalry

Mr. M had a romantic relationship with “Ms. B” in high school that he describes as “on and off,” beginning during his sophomore year. He describes himself as a “quick learner” who is task-oriented. He says he was outgoing in high school but became more introverted during his last year there. After high school, Mr. M worked as an electrician and discontinued psychiatric follow-up because he “felt fine.” He lives at home with his parents, two older sisters, and twin brother, who he identifies as being a lifelong “rival.”

After Ms. B ended her relationship with Mr. M, he began to suspect that she had become romantically involved with his twin brother. After Mr. M observed his brother leaving the house one night, he confronted his twin, who denied any involvement with Ms. B. After his brother left, Mr. M became enraged and punched a wall, fracturing his hand.

Two weeks before admission, Mr. M became increasingly preoccupied with suspicions of his brother’s involvement with Ms. B and looked for evidence on Facebook. Mr. M intensely monitored his Facebook news feed, which constantly updates to show public posts made by a user’s Facebook friends. He interpreted his friends’ posts as either directly relating to him or to a new relationship between Ms. B and his twin brother, stating that his friends were “talking in analogies” rather than directly using names.

Mr. M’s Facebook use rapidly increased to 3 or more hours a day. He can access Facebook from his laptop or cell phone, and reports logging in more than 10 times throughout the day. He says that, on Facebook, “it’s easier to talk trash” because people can say things they would not normally say face to face. He also states that Facebook is “ruining personal relationships,” and that it is “so easy to be in touch with everyone without really being in touch.”

The authors’ observations

In Mr. M’s case, Facebook served as a vehicle through which he could pursue a non-bizarre delusion. Mr. M openly admitted to viewing his twin brother as a rival; it is not surprising, therefore, that his delusions targeted his brother and ex-girlfriend.

Before social networks, the perseveration of this delusion might have been limited to internal thinking, or gathering corroborative information by means of stalking. Social media outlets have provided a means to perseverate and implicate others remotely, however, and Mr. M soon expanded his delusions to include more peers.

After beginning to suspect that friends and family are commenting on or criticizing him through Facebook, Mr. M experienced an irresistible impulse to repeatedly check the social network, which may have provided short-term relief of anticipatory anxiety, but that perpetuated the cycle. Constant access to the internet facilitated and intensified Mr. M’s cycle of paranoia, anxiety, and dysphoria. He called this process an “addiction.” A conceptual framework of the development of Mr. M’s maladaptive use of Facebook is illustrated in Figure 1.

Risk factors

Insecurity with one’s self-worth also may be a warning sign. Online social networking circumvents the need for physical interaction. A Facebook profile allows a person to selectively portray himself (herself) to the world, which may not be congruous with how his peers see him in everyday life. Patients who fear criticism or judgment may be more prone to maladaptive Facebook use, because they might feel empowered by the control they have over how others see them—online, at least.

Limited or, in Mr. M’s case, singular romantic experience may have influenced the course of his illness. Mr. M described his romantic involvement as a single, tumultuous relationship that lasted several years. Young patients with limited romantic experience may struggle to develop healthy protective mechanisms and may become preoccupied with the details of the situation, such that it interferes with functioning.

Mr. M’s history of ADHD might be a risk factor for abnormal patterns of internet use. Patients with ADHD have increased attentiveness with visually stimulating tasks—specifically, computers and video games.12

Last, it is unclear how, or if, Mr. M’s history of head injury contributed to his symptoms. There were no clear, temporal changes in cognition or emotion associated with the head injury, and he did not receive regular follow-up. Significant cognitive impairment does not appear to be a factor.

a) restart fluoxetine

b) begin an atypical antipsychotic

c) begin a mood stabilizer and atypical antipsychotic

d) encourage Mr. M to deactivate his Facebook account

TREATMENT: Observed use

Quetiapine is selected to target psychosis, agitation, and insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep initiation. Risperidone is added as a short-term agent to boost antipsychotic effect during the day when Mr. M is not fully responsive to quetiapine alone. Valproic acid is added on admission as a mood stabilizer to target emotional lability, impulsiveness, and possible mania.

After several days of treatment, and without access to a computer, Mr. M is calmer. We begin to assess the challenges of self-limiting time spent on Facebook; Mr. M explains that, before hospitalization, he had deactivated his Facebook account several times to try to rid himself of what he describes as an “addiction to social media”; soon afterward, however, he experienced overwhelming anxiety that led him to reactivate his account.

We sit with Mr. M as he logs in to Facebook and discuss the range of alternative explanations that specific public messages on his news feed could have. Explicitly listing alternative explanations is a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Mr. M begins to demonstrate increased insight regarding his paranoia and possible misinterpretation of information gleaned via Facebook; however, he still believes that masked references to him had existed. During his hospital stay he begins to acknowledge the problems that online interactions pose compared with face-to-face interactions, stating that, “There’s no emotion in [Facebook], so you can easily misinterpret what someone says.”

The authors’ observations

Mr. M was discharged after 7 days of treatment and has been seen weekly as an outpatient for 3 months without need for further hospitalization.

Bottom Line

Pervasive access to social media represents a vehicle for relapse of many psychiatric conditions. Younger patients may be especially at risk because they are more likely to use social media and are in the age range for onset of psychiatric illness. Although some degree of dependence on online networks can be considered normal, patients suffering from mental illness represent a vulnerable population for maladaptive online interactions.

Related Resources

• Sandler EP. If you’re in crisis, go online. Psychology Today. www.psychologytoday.com/blog/promoting-hope-preventing-suicide/201110/if-you-re-in-crisis-go-online. Published October 26, 2011.

• Nitzan U, Shoshan E, Lev-Ran S, et al. Internet-related psychosis−a sign of the times. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(3):207-211.

• Martin EA, Bailey DH, Cicero DC, et al. Social networking profile correlates of schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):641-646.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal Valproic acid • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Facebook. Facebook reports second quarter 2013 results. http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID= 780093. Updated July 24, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2013.

2. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Offline consequences of online victimization: school violence and delinquency. Journal of School Violence. 2007;6(3):89-112.

3. Pantic I, Damjanovic A, Todorovic J, et al. Associations between online social networking and depression in high school students: behavioral physiology viewpoint. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(1):90-93.

4. O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K; Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):800-804.

5. Gonzales AL, Hancock JT. Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: effects of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(1-2):79-83.

6. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(3):206-221.

7. Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, et al. Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: the role of perceived friendship quality. J Adolesc. 2009;32(4):819-833.

8. Morrison CM, Gore H. The relationship between excessive internet use and depression: a questionnaire-based study of 1,319 young people and adults. Psychopathology. 2010; 43:121-126.

9. Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, et al. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501-517.

10. SAMHSA News. Suicide prevention: a national priority. vol 20, no 3. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012.

11. Facebook. New partnership between Facebook and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=310287485658707. Accessed July 25, 2013.

12. Weinstein A, Weizman A. Emerging association between addictive gaming and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(5):590-597.

1. Facebook. Facebook reports second quarter 2013 results. http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID= 780093. Updated July 24, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2013.

2. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Offline consequences of online victimization: school violence and delinquency. Journal of School Violence. 2007;6(3):89-112.

3. Pantic I, Damjanovic A, Todorovic J, et al. Associations between online social networking and depression in high school students: behavioral physiology viewpoint. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(1):90-93.

4. O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K; Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):800-804.

5. Gonzales AL, Hancock JT. Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: effects of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(1-2):79-83.

6. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(3):206-221.

7. Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, et al. Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: the role of perceived friendship quality. J Adolesc. 2009;32(4):819-833.

8. Morrison CM, Gore H. The relationship between excessive internet use and depression: a questionnaire-based study of 1,319 young people and adults. Psychopathology. 2010; 43:121-126.

9. Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, et al. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501-517.

10. SAMHSA News. Suicide prevention: a national priority. vol 20, no 3. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012.

11. Facebook. New partnership between Facebook and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=310287485658707. Accessed July 25, 2013.

12. Weinstein A, Weizman A. Emerging association between addictive gaming and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(5):590-597.