User login

Documentation of Clinical Reasoning in Admission Notes of Hospitalists: Validation of the CRANAPL Assessment Rubric

Approximately 60,000 hospitalists were working in the United States in 2018.1 Hospitalist groups work collaboratively because of the shiftwork required for 24/7 patient coverage, and first-rate clinical documentation is essential for quality care.2 Thoughtful clinical documentation not only transmits one provider’s clinical reasoning to other providers but is a professional responsibility.3 Hospitalists spend two-thirds of their time in indirect patient-care activities and approximately one quarter of their time on documentation in electronic health records (EHRs).4 Despite documentation occupying a substantial portion of the clinician’s time, published literature on the best practices for the documentation of clinical reasoning in hospital medicine or its assessment remains scant.5-7

Clinical reasoning involves establishing a diagnosis and developing a therapeutic plan that fits the unique circumstances and needs of the patient.8 Inpatient providers who admit patients to the hospital end the admission note with their assessment and plan (A&P) after reflecting about a patient’s presenting illness. The A&P generally represents the interpretations, deductions, and clinical reasoning of the inpatient providers; this is the section of the note that fellow physicians concentrate on over others.9 The documentation of clinical reasoning in the A&P allows for many to consider how the recorded interpretations relate to their own elucidations resulting in distributed cognition.10

Disorganized documentation can contribute to cognitive overload and impede thoughtful consideration about the clinical presentation.3 The assessment of clinical documentation may translate into reduced medical errors and improved note quality.11,12 Studies that have formally evaluated the documentation of clinical reasoning have focused exclusively on medical students.13-15 The nonexistence of a detailed rubric for evaluating clinical reasoning in the A&Ps of hospitalists represents a missed opportunity for evaluating

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Subjects

This was a retrospective study that reviewed the admission notes of hospitalists for patients admitted over the period of January 2014 and October 2017 at three hospitals in Maryland. One is a community hospital (Hospital A) and two are academic medical centers (Hospital B and Hospital C). Even though these three hospitals are part of one health system, they have distinct cultures and leadership, serve different populations, and are staffed by different provider teams.

The notes of physicians working for the hospitalist groups at each of the three hospitals were the focus of the analysis in this study.

Development of the Documentation Assessment Rubric

A team was assembled to develop the Clinical Reasoning in Admission Note Assessment & PLan (CRANAPL) tool. The CRANAPL was designed to assess the comprehensiveness and thoughtfulness of the clinical reasoning documented in the A&P sections of the notes of patients who were admitted to the hospital with an acute illness. Validity evidence for CRANAPL was summarized on the basis of Messick’s unified validity framework by using four of the five sources of validity: content, response process, internal structure, and relations to other variables.17

Content Validity

The development team consisted of members who have an average of 10 years of clinical experience in hospital medicine; have studied clinical excellence and clinical reasoning; and have expertise in feedback, assessment, and professional development.18-22 The development of the CRANAPL tool by the team was informed by a review of the clinical reasoning literature, with particular attention paid to the standards and competencies outlined by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the Association of American Medical Colleges, the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education, the Internal Medicine Milestone Project, and the Society of Hospital Medicine.23-26 For each of these parties, diagnostic reasoning and its impact on clinical decision-making are considered to be a core competency. Several works that heavily influenced the CRANAPL tool’s development were Baker’s Interpretive Summary, Differential Diagnosis, Explanation of Reasoning, And Alternatives (IDEA) assessment tool;14 King’s Pediatric History and Physical Exam Evaluation (P-HAPEE) rubric;15 and three other studies related to diagnostic reasoning.16,27,28 These manuscripts and other works substantively informed the preliminary behavioral-based anchors that formed the initial foundation for the tool under development. The CRANAPL tool was shown to colleagues at other institutions who are leaders on clinical reasoning and was presented at academic conferences in the Division of General Internal Medicine and the Division of Hospital Medicine of our institution. Feedback resulted in iterative revisions. The aforementioned methods established content validity evidence for the CRANAPL tool.

Response Process Validity

Several of the authors pilot-tested earlier iterations on admission notes that were excluded from the sample when refining the CRANAPL tool. The weaknesses and sources of confusion with specific items were addressed by scoring 10 A&Ps individually and then comparing data captured on the tool. This cycle was repeated three times for the iterative enhancement and finalization of the CRANAPL tool. On several occasions when two authors were piloting the near-final CRANAPL tool, a third author interviewed each of the two authors about reactivity while assessing individual items and exploring with probes how their own clinical documentation practices were being considered when scoring the notes. The reasonable and thoughtful answers provided by the two authors as they explained and justified the scores they were selecting during the pilot testing served to confer response process validity evidence.

Finalizing the CRANAPL Tool

The nine-item CRANAPL tool includes elements for problem representation, leading diagnosis, uncertainty, differential diagnosis, plans for diagnosis and treatment, estimated length of stay (LOS), potential for upgrade in status to a higher level of care, and consideration of disposition. Although the final three items are not core clinical reasoning domains in the medical education literature, they represent clinical judgments that are especially relevant for the delivery of the high-quality and cost-effective care of hospitalized patients. Given that the probabilities and estimations of these three elements evolve over the course of any hospitalization on the basis of test results and response to therapy, the documentation of initial expectations on these fronts can facilitate distributed cognition with all individuals becoming wiser from shared insights.10 The tool uses two- and three-point rating scales, with each number score being clearly defined by specific written criteria (total score range: 0-14; Appendix).

Data Collection

Hospitalists’ admission notes from the three hospitals were used to validate the CRANAPL tool. Admission notes from patients hospitalized to the general medical floors with an admission diagnosis of either fever, syncope/dizziness, or abdominal pain were used. These diagnoses were purposefully examined because they (1) have a wide differential diagnosis, (2) are common presenting symptoms, and (3) are prone to diagnostic errors.29-32

The centralized EHR system across the three hospitals identified admission notes with one of these primary diagnoses of patients admitted over the period of January 2014 to October 2017. We submitted a request for 650 admission notes to be randomly selected from the centralized institutional records system. The notes were stratified by hospital and diagnosis. The sample size of our study was comparable with that of prior psychometric validation studies.33,34 Upon reviewing the A&Ps associated with these admissions, 365 notes were excluded for one of three reasons: (1) the note was written by a nurse practitioner, physician assistant, resident, or medical student; (2) the admission diagnosis had been definitively confirmed in the emergency department (eg, abdominal pain due to diverticulitis seen on CT); and (3) the note represented the fourth or more note by any single provider (to sample notes of many providers, no more than three notes written by any single provider were analyzed). A total of 285 admission notes were ultimately included in the sample.

Data were deidentified, and the A&P sections of the admission notes were each copied from the EHR into a unique Word document. Patient and hospital demographic data (including age, gender, race, number of comorbid conditions, LOS, hospital charges, and readmission to the same health system within 30 days) were collected separately from the EHR. Select physician characteristics were also collected from the hospitalist groups at each of the three hospitals, as was the length (word count) of each A&P.

The study was approved by our institutional review board.

Data Analysis

Two authors scored all deidentified A&Ps by using the finalized version of the CRANAPL tool. Prior to using the CRANAPL tool on each of the notes, these raters read each A&P and scored them by using two single-item rating scales: a global clinical reasoning and a global readability/clarity measure. Both of these global scales used three-item Likert scales (below average, average, and above average). These global rating scales collected the reviewers’ gestalt about the quality and clarity of the A&P. The use of gestalt ratings as comparators is supported by other research.35

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. Each rater rescored a sample of 48 records (one month after the initial scoring) and intraclass correlations (ICCs) were computed for intrarater reliability. ICCs were calculated for each item and for the CRANAPL total to determine interrater reliability.

The averaged ratings from the two raters were used for all other analyses. For CRANAPL’s internal structure validity evidence, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as a measure of internal consistency. For relations to other variables validity evidence, CRANAPL total scores were compared with the two global assessment variables with linear regressions.

Bivariate analyses were performed by applying parametric and nonparametric tests as appropriate. A series of multivariate linear regressions, controlling for diagnosis and clustered variance by hospital site, were performed using CRANAPL total as the dependent variable and patient variables as predictors.

All data were analyzed using Stata (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP.)

RESULTS

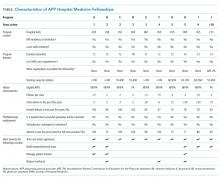

The admission notes of 120 hospitalists were evaluated (Table 1). A total of 39 (33%) physicians were moonlighters with primary appointments outside of the hospitalist division, and 81 (68%) were full-time hospitalists. Among the 120 hospitalists, 48 (40%) were female, 60 (50%) were international medical graduates, and 90 (75%) were of nonwhite race. Most hospitalist physicians (n = 47, 58%) had worked in our health system for less than five years, and 64 hospitalists (53%) devoted greater than 50% of their time to patient care.

Approximately equal numbers of patient admission notes were pulled from each of the three hospitals. The average age of patients was 67.2 (SD 13.6) years, 145 (51%) were female, and 120 (42%) were of nonwhite race. The mean LOS for all patients was 4.0 (SD 3.4) days. A total of 44 (15%) patients were readmitted to the same health system within 30 days of discharge. None of the patients died during the incident hospitalization. The average charge for each of the hospitalizations was $10,646 (SD $9,964).

CRANAPL Data

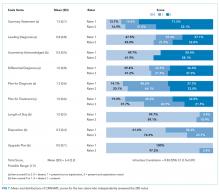

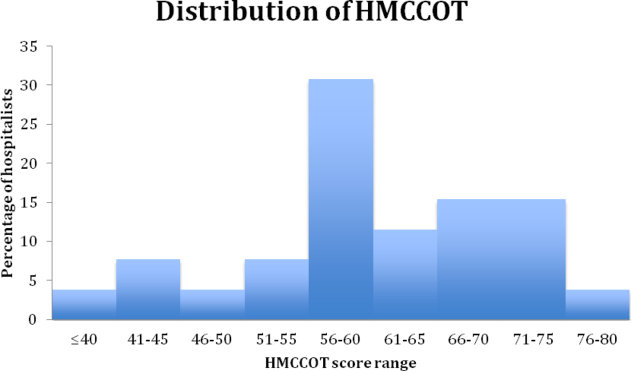

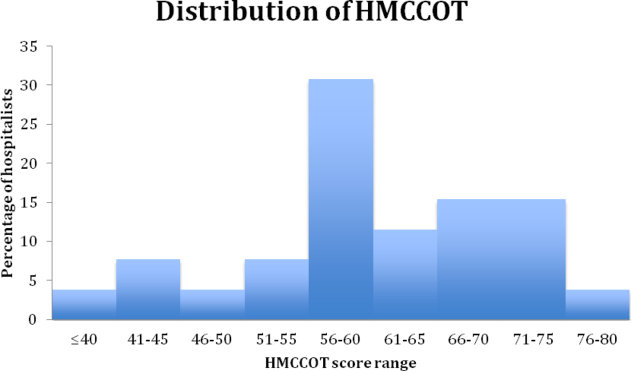

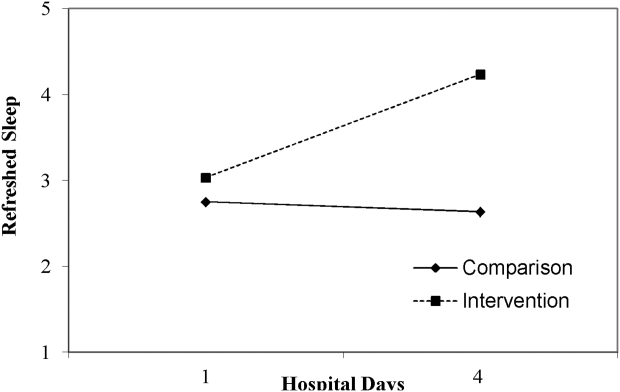

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the scores given by each rater for each of the nine items. The mean of the total CRANAPL score given by both raters was 6.4 (SD 2.2). Scoring for some items were high (eg, summary statement: 1.5/2), whereas performance on others were low (eg, estimating LOS: 0.1/1 and describing the potential need for upgrade in care: 0.0/1).

Validity of the CRANAPL Tool’s Internal Structure

Cronbach’s alpha, which was used to measure internal consistency within the CRANAPL tool, was 0.43. The ICC, which was applied to measure the interrater reliability for both raters for the total CRANAPL score, was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.76-0.87). The ICC values for intrarater reliability for raters 1 and 2 were 0.73 (95% CI: 0.60-0.83) and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.45-0.86), respectively.

Relations to Other Variables Validity

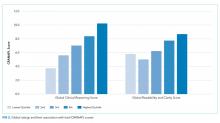

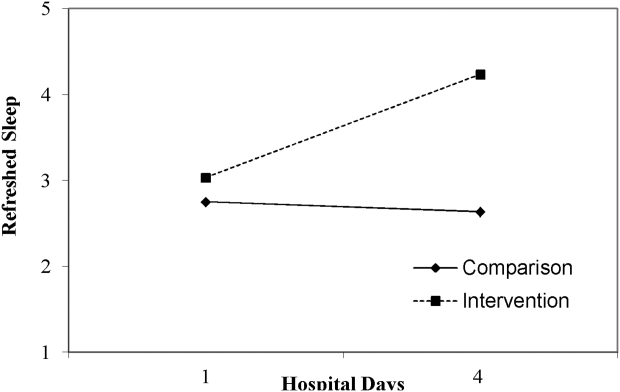

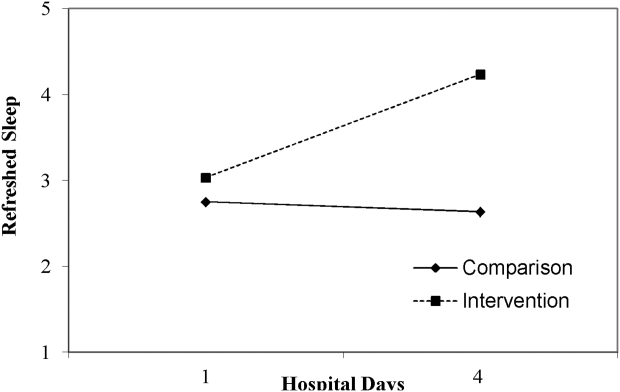

Associations between CRANAPL total scores, global clinical reasoning, and global scores for note readability/clarity were statistically significant (P < .001), Figure 2.

Eight out of nine CRANAPL variables were statistically significantly different across the three hospitals (P <. 01) when data were analyzed by hospital site. Hospital C had the highest mean score of 7.4 (SD 2.0), followed by Hospital B with a score of 6.6 (SD 2.1), and Hospital A had the lowest total CRANAPL score of 5.2 (SD 1.9). This difference was statistically significant (P < .001). Five variables with respect to admission diagnoses (uncertainty acknowledged, differential diagnosis, plan for diagnosis, plan for treatment, and upgrade plan) were statistically significantly different across notes. Notes for syncope/dizziness generally yielded higher scores than those for abdominal pain and fever.

Factors Associated with High CRANAPL Scores

Table 2 shows the associations between CRANAPL scores and several covariates. Before adjustment, high CRANAPL scores were associated with high word counts of A&Ps (P < .001) and high hospital charges (P < .05). These associations were no longer significant after adjusting for hospital site and admitting diagnoses.

DISCUSSION

We reviewed the documentation of clinical reasoning in 285 admission notes at three different hospitals written by hospitalist physicians during routine clinical care. To our knowledge, this is the first study that assessed the documentation of hospitalists’ clinical reasoning with real patient notes. Wide variability exists in the documentation of clinical reasoning within the A&Ps of hospitalists’ admission notes. We have provided validity evidence to support the use of the user-friendly CRANAPL tool.

Prior studies have described rubrics for evaluating the clinical reasoning skills of medical students.14,15 The ICCs for the IDEA rubric used to assess medical students’ documentation of clinical reasoning were fair to moderate (0.29-0.67), whereas the ICC for the CRANAPL tool was high at 0.83. This measure of reliability is similar to that for the P-HAPEE rubric used to assess medical students’ documentation of pediatric history and physical notes.15 These data are markedly different from the data in previous studies that have found low interrater reliability for psychometric evaluations related to judgment and decision-making.36-39 CRANAPL was also found to have high intrarater reliability, which shows the reproducibility of an individual’s assessment over time. The strong association between the total CRANAPL score and global clinical reasoning assessment found in the present study is similar to that found in previous studies that have also embedded global rating scales as comparators when assessing clinical reasoning.13,,15,40,41 Global rating scales represent an overarching structure for comparison given the absence of an accepted method or gold standard for assessing clinical reasoning documentation. High-quality provider notes are defined by clarity, thoroughness, and accuracy;35 and effective documentation promotes communication and the coordination of care among the members of the care team.3

The total CRANAPL scores varied by hospital site with academic hospitals (B and C) scoring higher than the community hospital (A) in our study. Similarly, lengthy A&Ps were associated with high CRANAPL scores (P < .001) prior to adjustment for hospital site. Healthcare providers consider that the thoroughness of documentation denotes quality and attention to detail.35,42 Comprehensive documentation takes time; the longer notes by academic hospitalists than those by community hospitalists may be attributed to the fewer number of patients generally carried by hospitalists at academic centers than that by hospitalists at community hospitals.43

The documentation of the estimations of LOS, possibility of potential upgrade, and thoughts about disposition were consistently poorly described across all hospital sites and diagnoses. In contrast to CRANAPL, other clinical reasoning rubrics have excluded these items or discussed uncertainty.14,15,44 These elements represent the forward thinking that may be essential for high-quality progressive care by hospitalists. Physicians’s difficulty in acknowledging uncertainty has been associated with resource overuse, including the excessive ordering of tests, iatrogenic injury, and heavy financial burden on the healthcare system.45,46 The lack of thoughtful clinical and management reasoning at the time of admission is believed to be associated with medical errors.47 If used as a guide, the CRANAPL tool may promote reflection on the part of the admitting physician. The estimations of LOS, potential for upgrade to a higher level of care, and disposition are markers of optimal inpatient care, especially for hospitalists who work in shifts with embedded handoffs. When shared with colleagues (through documentation), there is the potential for distributed cognition10 to extend throughout the social network of the hospitalist group. The fact that so few providers are currently including these items in their A&P’s show that the providers are either not performing or documenting the ‘reasoning’. Either way, this is an opportunity that has been highlighted by the CRANAPL tool.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, the CRANAPL tool may not have captured elements of optimal clinical reasoning documentation. The reliance on multiple methods and an iterative process in the refinement of the CRANAPL tool should have minimized this. Second, this study was conducted across a single healthcare system that uses the same EHR; this EHR or institutional culture may influence documentation practices and behaviors. Given that using the CRANAPL tool to score an A&P is quick and easy, the benefit of giving providers feedback on their notes remains to be seen—here and at other hospitals. Third, our sample size could limit the generalizability of the results and the significance of the associations. However, the sample assessed in our study was significantly larger than that assessed in other studies that have validated clinical reasoning rubrics.14,15 Fourth, clinical reasoning is a broad and multidimensional construct. The CRANAPL tool focuses exclusively on hospitalists’ documentation of clinical reasoning and therefore does not assess aspects of clinical reasoning occurring in the physicians’ minds. Finally, given our goal to optimally validate the CRANAPL tool, we chose to test the tool on specific presentations that are known to be associated with diagnostic practice variation and errors. We may have observed different results had we chosen a different set of diagnoses from each hospital. Further validity evidence will be established when applying the CRANPL tool to different diagnoses and to notes from other clinical settings.

In conclusion, this study focuses on the development and validation of the CRANAPL tool that assesses how hospitalists document their clinical reasoning in the A&P section of admission notes. Our results show that wide variability exists in the documentation of clinical reasoning by hospitalists within and across hospitals. Given the CRANAPL tool’s ease-of-use and its versatility, hospitalist divisions in academic and nonacademic settings may use the CRANAPL tool to assess and provide feedback on the documentation of hospitalists’ clinical reasoning. Beyond studying whether physicians can be taught to improve their notes with feedback based on the CRANAPL tool, future studies may explore whether enhancing clinical reasoning documentation may be associated with improvements in patient care and clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wright is the Anne Gaines and G. Thomas Miller Professor of Medicine which is supported through Hopkins’ Center for Innovative Medicine.

The authors thank Christine Caufield-Noll, MLIS, AHIP (Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland) for her assistance with this project.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. State of Hospital Medicine. Society of Hospital Medicine. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed August 19, 2018.

2. Mehta R, Radhakrishnan NS, Warring CD, et al. The use of evidence-based, problem-oriented templates as a clinical decision support in an inpatient electronic health record system. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(3):790-802. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2015-11-RA-0164

3. Improving Diagnosis in Healthcare: Health and Medicine Division. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2015/Improving-Diagnosis-in-Healthcare.aspx. Accessed August 7, 2018.

4. Tipping MD, Forth VE, O’Leary KJ, et al. Where did the day go? A time-motion study of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):323-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.790

5. Varpio L, Rashotte J, Day K, King J, Kuziemsky C, Parush A. The EHR and building the patient’s story: a qualitative investigation of how EHR use obstructs a vital clinical activity. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(12):1019-1028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.09.004

6. Clynch N, Kellett J. Medical documentation: part of the solution, or part of the problem? A narrative review of the literature on the time spent on and value of medical documentation. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(4):221-228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.12.001

7. Varpio L, Day K, Elliot-Miller P, et al. The impact of adopting EHRs: how losing connectivity affects clinical reasoning. Med Educ. 2015;49(5):476-486. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12665

8. McBee E, Ratcliffe T, Schuwirth L, et al. Context and clinical reasoning: understanding the medical student perspective. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(4):256-263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0417-x

9. Brown PJ, Marquard JL, Amster B, et al. What do physicians read (and ignore) in electronic progress notes? Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5(2):430-444. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2014-01-RA-0003

10. Katherine D, Shalin VL. Creating a common trajectory: Shared decision making and distributed cognition in medical consultations. https://pxjournal.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1116&context=journal Accessed April 4, 2019.

11. Harchelroad FP, Martin ML, Kremen RM, Murray KW. Emergency department daily record review: a quality assurance system in a teaching hospital. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1988;14(2):45-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0097-5990(16)30187-7.

12. Opila DA. The impact of feedback to medical housestaff on chart documentation and quality of care in the outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):352-356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-5083-8.

13. Smith S, Kogan JR, Berman NB, Dell MS, Brock DM, Robins LS. The development and preliminary validation of a rubric to assess medical students’ written summary statements in virtual patient cases. Acad Med. 2016;91(1):94-100. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000800

14. Baker EA, Ledford CH, Fogg L, Way DP, Park YS. The IDEA assessment tool: assessing the reporting, diagnostic reasoning, and decision-making skills demonstrated in medical students’ hospital admission notes. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(2):163-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1011654

15. King MA, Phillipi CA, Buchanan PM, Lewin LO. Developing validity evidence for the written pediatric history and physical exam evaluation rubric. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(1):68-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.001

16. Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9):S63-S67.

17. Messick S. Standards of validity and the validity of standards in performance asessment. Educ Meas Issues Pract. 2005;14(4):5-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.1995.tb00881.x

18. Menachery EP, Knight AM, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Physician characteristics associated with proficiency in feedback skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):440-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00424.x

19. Tackett S, Eisele D, McGuire M, Rotello L, Wright S. Fostering clinical excellence across an academic health system. South Med J. 2016;109(8):471-476. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000498

20. Christmas C, Kravet SJ, Durso SC, Wright SM. Clinical excellence in academia: perspectives from masterful academic clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(9):989-994. https://doi.org/10.4065/83.9.989

21. Wright SM, Kravet S, Christmas C, Burkhart K, Durso SC. Creating an academy of clinical excellence at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center: a 3-year experience. Acad Med. 2010;85(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181fa416c

22. Kotwal S, Peña I, Howell E, Wright S. Defining clinical excellence in hospital medicine: a qualitative study. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37(1):3-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000145

23. Common Program Requirements. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements. Accessed August 21, 2018.

24. Warren J, Lupi C, Schwartz ML, et al. Chief Medical Education Officer.; 2017. https://www.aamc.org/download/482204/data/epa9toolkit.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

25. Th He Inte. https://www.abim.org/~/media/ABIM Public/Files/pdf/milestones/internal-medicine-milestones-project.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

26. Core Competencies. Society of Hospital Medicine. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/professional-development/core-competencies/. Accessed August 21, 2018.

27. Bowen JL. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. Cox M,

28. Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199911000-00012.

29. Rao G, Epner P, Bauer V, Solomonides A, Newman-Toker DE. Identifying and analyzing diagnostic paths: a new approach for studying diagnostic practices. Diagnosis Berlin, Ger. 2017;4(2):67-72. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2016-0049

30. Ely JW, Kaldjian LC, D’Alessandro DM. Diagnostic errors in primary care: lessons learned. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(1):87-97. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110174

31. Kerber KA, Newman-Toker DE. Misdiagnosing dizzy patients: common pitfalls in clinical practice. Neurol Clin. 2015;33(3):565-75, viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.009

32. Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer AND, Forjuoh SN, Reis MD, Thomas EJ. Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):418. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2777.

33. Kahn D, Stewart E, Duncan M, et al. A prescription for note bloat: an effective progress note template. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):378-382. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2898

34. Anthoine E, Moret L, Regnault A, Sébille V, Hardouin J-B. Sample size used to validate a scale: a review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-014-0176-2

35. Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, Siegler EL. Assessing electronic note quality using the physician documentation quality instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(2):164-174. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2011-11-RA-0070

36. Govaerts MJB, Schuwirth LWT, Van der Vleuten CPM, Muijtjens AMM. Workplace-based assessment: effects of rater expertise. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16(2):151-165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9250-7

37. Kreiter CD, Ferguson KJ. Examining the generalizability of ratings across clerkships using a clinical evaluation form. Eval Health Prof. 2001;24(1):36-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/01632780122034768

38. Middleman AB, Sunder PK, Yen AG. Reliability of the history and physical assessment (HAPA) form. Clin Teach. 2011;8(3):192-195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2011.00459.x

39. Kogan JR, Shea JA. Psychometric characteristics of a write-up assessment form in a medicine core clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17(2):101-106. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1702_2

40. Lewin LO, Beraho L, Dolan S, Millstein L, Bowman D. Interrater reliability of an oral case presentation rating tool in a pediatric clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(1):31-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2012.741537

41. Gray JD. Global rating scales in residency education. Acad Med. 1996;71(1):S55-S63.

42. Rosenbloom ST, Crow AN, Blackford JU, Johnson KB. Cognitive factors influencing perceptions of clinical documentation tools. J Biomed Inform. 2007;40(2):106-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2006.06.006

43. Michtalik HJ, Pronovost PJ, Marsteller JA, Spetz J, Brotman DJ. Identifying potential predictors of a safe attending physician workload: a survey of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):644-646. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2088

44. Seo J-H, Kong H-H, Im S-J, et al. A pilot study on the evaluation of medical student documentation: assessment of SOAP notes. Korean J Med Educ. 2016;28(2):237-241. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2016.26

45. Kassirer JP. Our stubborn quest for diagnostic certainty. A cause of excessive testing. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(22):1489-1491. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198906013202211

46. Hatch S. Uncertainty in medicine. BMJ. 2017;357:j2180. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2180

47. Cook DA, Sherbino J, Durning SJ. Management reasoning. JAMA. 2018;319(22):2267. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.4385

Approximately 60,000 hospitalists were working in the United States in 2018.1 Hospitalist groups work collaboratively because of the shiftwork required for 24/7 patient coverage, and first-rate clinical documentation is essential for quality care.2 Thoughtful clinical documentation not only transmits one provider’s clinical reasoning to other providers but is a professional responsibility.3 Hospitalists spend two-thirds of their time in indirect patient-care activities and approximately one quarter of their time on documentation in electronic health records (EHRs).4 Despite documentation occupying a substantial portion of the clinician’s time, published literature on the best practices for the documentation of clinical reasoning in hospital medicine or its assessment remains scant.5-7

Clinical reasoning involves establishing a diagnosis and developing a therapeutic plan that fits the unique circumstances and needs of the patient.8 Inpatient providers who admit patients to the hospital end the admission note with their assessment and plan (A&P) after reflecting about a patient’s presenting illness. The A&P generally represents the interpretations, deductions, and clinical reasoning of the inpatient providers; this is the section of the note that fellow physicians concentrate on over others.9 The documentation of clinical reasoning in the A&P allows for many to consider how the recorded interpretations relate to their own elucidations resulting in distributed cognition.10

Disorganized documentation can contribute to cognitive overload and impede thoughtful consideration about the clinical presentation.3 The assessment of clinical documentation may translate into reduced medical errors and improved note quality.11,12 Studies that have formally evaluated the documentation of clinical reasoning have focused exclusively on medical students.13-15 The nonexistence of a detailed rubric for evaluating clinical reasoning in the A&Ps of hospitalists represents a missed opportunity for evaluating

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Subjects

This was a retrospective study that reviewed the admission notes of hospitalists for patients admitted over the period of January 2014 and October 2017 at three hospitals in Maryland. One is a community hospital (Hospital A) and two are academic medical centers (Hospital B and Hospital C). Even though these three hospitals are part of one health system, they have distinct cultures and leadership, serve different populations, and are staffed by different provider teams.

The notes of physicians working for the hospitalist groups at each of the three hospitals were the focus of the analysis in this study.

Development of the Documentation Assessment Rubric

A team was assembled to develop the Clinical Reasoning in Admission Note Assessment & PLan (CRANAPL) tool. The CRANAPL was designed to assess the comprehensiveness and thoughtfulness of the clinical reasoning documented in the A&P sections of the notes of patients who were admitted to the hospital with an acute illness. Validity evidence for CRANAPL was summarized on the basis of Messick’s unified validity framework by using four of the five sources of validity: content, response process, internal structure, and relations to other variables.17

Content Validity

The development team consisted of members who have an average of 10 years of clinical experience in hospital medicine; have studied clinical excellence and clinical reasoning; and have expertise in feedback, assessment, and professional development.18-22 The development of the CRANAPL tool by the team was informed by a review of the clinical reasoning literature, with particular attention paid to the standards and competencies outlined by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the Association of American Medical Colleges, the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education, the Internal Medicine Milestone Project, and the Society of Hospital Medicine.23-26 For each of these parties, diagnostic reasoning and its impact on clinical decision-making are considered to be a core competency. Several works that heavily influenced the CRANAPL tool’s development were Baker’s Interpretive Summary, Differential Diagnosis, Explanation of Reasoning, And Alternatives (IDEA) assessment tool;14 King’s Pediatric History and Physical Exam Evaluation (P-HAPEE) rubric;15 and three other studies related to diagnostic reasoning.16,27,28 These manuscripts and other works substantively informed the preliminary behavioral-based anchors that formed the initial foundation for the tool under development. The CRANAPL tool was shown to colleagues at other institutions who are leaders on clinical reasoning and was presented at academic conferences in the Division of General Internal Medicine and the Division of Hospital Medicine of our institution. Feedback resulted in iterative revisions. The aforementioned methods established content validity evidence for the CRANAPL tool.

Response Process Validity

Several of the authors pilot-tested earlier iterations on admission notes that were excluded from the sample when refining the CRANAPL tool. The weaknesses and sources of confusion with specific items were addressed by scoring 10 A&Ps individually and then comparing data captured on the tool. This cycle was repeated three times for the iterative enhancement and finalization of the CRANAPL tool. On several occasions when two authors were piloting the near-final CRANAPL tool, a third author interviewed each of the two authors about reactivity while assessing individual items and exploring with probes how their own clinical documentation practices were being considered when scoring the notes. The reasonable and thoughtful answers provided by the two authors as they explained and justified the scores they were selecting during the pilot testing served to confer response process validity evidence.

Finalizing the CRANAPL Tool

The nine-item CRANAPL tool includes elements for problem representation, leading diagnosis, uncertainty, differential diagnosis, plans for diagnosis and treatment, estimated length of stay (LOS), potential for upgrade in status to a higher level of care, and consideration of disposition. Although the final three items are not core clinical reasoning domains in the medical education literature, they represent clinical judgments that are especially relevant for the delivery of the high-quality and cost-effective care of hospitalized patients. Given that the probabilities and estimations of these three elements evolve over the course of any hospitalization on the basis of test results and response to therapy, the documentation of initial expectations on these fronts can facilitate distributed cognition with all individuals becoming wiser from shared insights.10 The tool uses two- and three-point rating scales, with each number score being clearly defined by specific written criteria (total score range: 0-14; Appendix).

Data Collection

Hospitalists’ admission notes from the three hospitals were used to validate the CRANAPL tool. Admission notes from patients hospitalized to the general medical floors with an admission diagnosis of either fever, syncope/dizziness, or abdominal pain were used. These diagnoses were purposefully examined because they (1) have a wide differential diagnosis, (2) are common presenting symptoms, and (3) are prone to diagnostic errors.29-32

The centralized EHR system across the three hospitals identified admission notes with one of these primary diagnoses of patients admitted over the period of January 2014 to October 2017. We submitted a request for 650 admission notes to be randomly selected from the centralized institutional records system. The notes were stratified by hospital and diagnosis. The sample size of our study was comparable with that of prior psychometric validation studies.33,34 Upon reviewing the A&Ps associated with these admissions, 365 notes were excluded for one of three reasons: (1) the note was written by a nurse practitioner, physician assistant, resident, or medical student; (2) the admission diagnosis had been definitively confirmed in the emergency department (eg, abdominal pain due to diverticulitis seen on CT); and (3) the note represented the fourth or more note by any single provider (to sample notes of many providers, no more than three notes written by any single provider were analyzed). A total of 285 admission notes were ultimately included in the sample.

Data were deidentified, and the A&P sections of the admission notes were each copied from the EHR into a unique Word document. Patient and hospital demographic data (including age, gender, race, number of comorbid conditions, LOS, hospital charges, and readmission to the same health system within 30 days) were collected separately from the EHR. Select physician characteristics were also collected from the hospitalist groups at each of the three hospitals, as was the length (word count) of each A&P.

The study was approved by our institutional review board.

Data Analysis

Two authors scored all deidentified A&Ps by using the finalized version of the CRANAPL tool. Prior to using the CRANAPL tool on each of the notes, these raters read each A&P and scored them by using two single-item rating scales: a global clinical reasoning and a global readability/clarity measure. Both of these global scales used three-item Likert scales (below average, average, and above average). These global rating scales collected the reviewers’ gestalt about the quality and clarity of the A&P. The use of gestalt ratings as comparators is supported by other research.35

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. Each rater rescored a sample of 48 records (one month after the initial scoring) and intraclass correlations (ICCs) were computed for intrarater reliability. ICCs were calculated for each item and for the CRANAPL total to determine interrater reliability.

The averaged ratings from the two raters were used for all other analyses. For CRANAPL’s internal structure validity evidence, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as a measure of internal consistency. For relations to other variables validity evidence, CRANAPL total scores were compared with the two global assessment variables with linear regressions.

Bivariate analyses were performed by applying parametric and nonparametric tests as appropriate. A series of multivariate linear regressions, controlling for diagnosis and clustered variance by hospital site, were performed using CRANAPL total as the dependent variable and patient variables as predictors.

All data were analyzed using Stata (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP.)

RESULTS

The admission notes of 120 hospitalists were evaluated (Table 1). A total of 39 (33%) physicians were moonlighters with primary appointments outside of the hospitalist division, and 81 (68%) were full-time hospitalists. Among the 120 hospitalists, 48 (40%) were female, 60 (50%) were international medical graduates, and 90 (75%) were of nonwhite race. Most hospitalist physicians (n = 47, 58%) had worked in our health system for less than five years, and 64 hospitalists (53%) devoted greater than 50% of their time to patient care.

Approximately equal numbers of patient admission notes were pulled from each of the three hospitals. The average age of patients was 67.2 (SD 13.6) years, 145 (51%) were female, and 120 (42%) were of nonwhite race. The mean LOS for all patients was 4.0 (SD 3.4) days. A total of 44 (15%) patients were readmitted to the same health system within 30 days of discharge. None of the patients died during the incident hospitalization. The average charge for each of the hospitalizations was $10,646 (SD $9,964).

CRANAPL Data

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the scores given by each rater for each of the nine items. The mean of the total CRANAPL score given by both raters was 6.4 (SD 2.2). Scoring for some items were high (eg, summary statement: 1.5/2), whereas performance on others were low (eg, estimating LOS: 0.1/1 and describing the potential need for upgrade in care: 0.0/1).

Validity of the CRANAPL Tool’s Internal Structure

Cronbach’s alpha, which was used to measure internal consistency within the CRANAPL tool, was 0.43. The ICC, which was applied to measure the interrater reliability for both raters for the total CRANAPL score, was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.76-0.87). The ICC values for intrarater reliability for raters 1 and 2 were 0.73 (95% CI: 0.60-0.83) and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.45-0.86), respectively.

Relations to Other Variables Validity

Associations between CRANAPL total scores, global clinical reasoning, and global scores for note readability/clarity were statistically significant (P < .001), Figure 2.

Eight out of nine CRANAPL variables were statistically significantly different across the three hospitals (P <. 01) when data were analyzed by hospital site. Hospital C had the highest mean score of 7.4 (SD 2.0), followed by Hospital B with a score of 6.6 (SD 2.1), and Hospital A had the lowest total CRANAPL score of 5.2 (SD 1.9). This difference was statistically significant (P < .001). Five variables with respect to admission diagnoses (uncertainty acknowledged, differential diagnosis, plan for diagnosis, plan for treatment, and upgrade plan) were statistically significantly different across notes. Notes for syncope/dizziness generally yielded higher scores than those for abdominal pain and fever.

Factors Associated with High CRANAPL Scores

Table 2 shows the associations between CRANAPL scores and several covariates. Before adjustment, high CRANAPL scores were associated with high word counts of A&Ps (P < .001) and high hospital charges (P < .05). These associations were no longer significant after adjusting for hospital site and admitting diagnoses.

DISCUSSION

We reviewed the documentation of clinical reasoning in 285 admission notes at three different hospitals written by hospitalist physicians during routine clinical care. To our knowledge, this is the first study that assessed the documentation of hospitalists’ clinical reasoning with real patient notes. Wide variability exists in the documentation of clinical reasoning within the A&Ps of hospitalists’ admission notes. We have provided validity evidence to support the use of the user-friendly CRANAPL tool.

Prior studies have described rubrics for evaluating the clinical reasoning skills of medical students.14,15 The ICCs for the IDEA rubric used to assess medical students’ documentation of clinical reasoning were fair to moderate (0.29-0.67), whereas the ICC for the CRANAPL tool was high at 0.83. This measure of reliability is similar to that for the P-HAPEE rubric used to assess medical students’ documentation of pediatric history and physical notes.15 These data are markedly different from the data in previous studies that have found low interrater reliability for psychometric evaluations related to judgment and decision-making.36-39 CRANAPL was also found to have high intrarater reliability, which shows the reproducibility of an individual’s assessment over time. The strong association between the total CRANAPL score and global clinical reasoning assessment found in the present study is similar to that found in previous studies that have also embedded global rating scales as comparators when assessing clinical reasoning.13,,15,40,41 Global rating scales represent an overarching structure for comparison given the absence of an accepted method or gold standard for assessing clinical reasoning documentation. High-quality provider notes are defined by clarity, thoroughness, and accuracy;35 and effective documentation promotes communication and the coordination of care among the members of the care team.3

The total CRANAPL scores varied by hospital site with academic hospitals (B and C) scoring higher than the community hospital (A) in our study. Similarly, lengthy A&Ps were associated with high CRANAPL scores (P < .001) prior to adjustment for hospital site. Healthcare providers consider that the thoroughness of documentation denotes quality and attention to detail.35,42 Comprehensive documentation takes time; the longer notes by academic hospitalists than those by community hospitalists may be attributed to the fewer number of patients generally carried by hospitalists at academic centers than that by hospitalists at community hospitals.43

The documentation of the estimations of LOS, possibility of potential upgrade, and thoughts about disposition were consistently poorly described across all hospital sites and diagnoses. In contrast to CRANAPL, other clinical reasoning rubrics have excluded these items or discussed uncertainty.14,15,44 These elements represent the forward thinking that may be essential for high-quality progressive care by hospitalists. Physicians’s difficulty in acknowledging uncertainty has been associated with resource overuse, including the excessive ordering of tests, iatrogenic injury, and heavy financial burden on the healthcare system.45,46 The lack of thoughtful clinical and management reasoning at the time of admission is believed to be associated with medical errors.47 If used as a guide, the CRANAPL tool may promote reflection on the part of the admitting physician. The estimations of LOS, potential for upgrade to a higher level of care, and disposition are markers of optimal inpatient care, especially for hospitalists who work in shifts with embedded handoffs. When shared with colleagues (through documentation), there is the potential for distributed cognition10 to extend throughout the social network of the hospitalist group. The fact that so few providers are currently including these items in their A&P’s show that the providers are either not performing or documenting the ‘reasoning’. Either way, this is an opportunity that has been highlighted by the CRANAPL tool.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, the CRANAPL tool may not have captured elements of optimal clinical reasoning documentation. The reliance on multiple methods and an iterative process in the refinement of the CRANAPL tool should have minimized this. Second, this study was conducted across a single healthcare system that uses the same EHR; this EHR or institutional culture may influence documentation practices and behaviors. Given that using the CRANAPL tool to score an A&P is quick and easy, the benefit of giving providers feedback on their notes remains to be seen—here and at other hospitals. Third, our sample size could limit the generalizability of the results and the significance of the associations. However, the sample assessed in our study was significantly larger than that assessed in other studies that have validated clinical reasoning rubrics.14,15 Fourth, clinical reasoning is a broad and multidimensional construct. The CRANAPL tool focuses exclusively on hospitalists’ documentation of clinical reasoning and therefore does not assess aspects of clinical reasoning occurring in the physicians’ minds. Finally, given our goal to optimally validate the CRANAPL tool, we chose to test the tool on specific presentations that are known to be associated with diagnostic practice variation and errors. We may have observed different results had we chosen a different set of diagnoses from each hospital. Further validity evidence will be established when applying the CRANPL tool to different diagnoses and to notes from other clinical settings.

In conclusion, this study focuses on the development and validation of the CRANAPL tool that assesses how hospitalists document their clinical reasoning in the A&P section of admission notes. Our results show that wide variability exists in the documentation of clinical reasoning by hospitalists within and across hospitals. Given the CRANAPL tool’s ease-of-use and its versatility, hospitalist divisions in academic and nonacademic settings may use the CRANAPL tool to assess and provide feedback on the documentation of hospitalists’ clinical reasoning. Beyond studying whether physicians can be taught to improve their notes with feedback based on the CRANAPL tool, future studies may explore whether enhancing clinical reasoning documentation may be associated with improvements in patient care and clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wright is the Anne Gaines and G. Thomas Miller Professor of Medicine which is supported through Hopkins’ Center for Innovative Medicine.

The authors thank Christine Caufield-Noll, MLIS, AHIP (Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland) for her assistance with this project.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Approximately 60,000 hospitalists were working in the United States in 2018.1 Hospitalist groups work collaboratively because of the shiftwork required for 24/7 patient coverage, and first-rate clinical documentation is essential for quality care.2 Thoughtful clinical documentation not only transmits one provider’s clinical reasoning to other providers but is a professional responsibility.3 Hospitalists spend two-thirds of their time in indirect patient-care activities and approximately one quarter of their time on documentation in electronic health records (EHRs).4 Despite documentation occupying a substantial portion of the clinician’s time, published literature on the best practices for the documentation of clinical reasoning in hospital medicine or its assessment remains scant.5-7

Clinical reasoning involves establishing a diagnosis and developing a therapeutic plan that fits the unique circumstances and needs of the patient.8 Inpatient providers who admit patients to the hospital end the admission note with their assessment and plan (A&P) after reflecting about a patient’s presenting illness. The A&P generally represents the interpretations, deductions, and clinical reasoning of the inpatient providers; this is the section of the note that fellow physicians concentrate on over others.9 The documentation of clinical reasoning in the A&P allows for many to consider how the recorded interpretations relate to their own elucidations resulting in distributed cognition.10

Disorganized documentation can contribute to cognitive overload and impede thoughtful consideration about the clinical presentation.3 The assessment of clinical documentation may translate into reduced medical errors and improved note quality.11,12 Studies that have formally evaluated the documentation of clinical reasoning have focused exclusively on medical students.13-15 The nonexistence of a detailed rubric for evaluating clinical reasoning in the A&Ps of hospitalists represents a missed opportunity for evaluating

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Subjects

This was a retrospective study that reviewed the admission notes of hospitalists for patients admitted over the period of January 2014 and October 2017 at three hospitals in Maryland. One is a community hospital (Hospital A) and two are academic medical centers (Hospital B and Hospital C). Even though these three hospitals are part of one health system, they have distinct cultures and leadership, serve different populations, and are staffed by different provider teams.

The notes of physicians working for the hospitalist groups at each of the three hospitals were the focus of the analysis in this study.

Development of the Documentation Assessment Rubric

A team was assembled to develop the Clinical Reasoning in Admission Note Assessment & PLan (CRANAPL) tool. The CRANAPL was designed to assess the comprehensiveness and thoughtfulness of the clinical reasoning documented in the A&P sections of the notes of patients who were admitted to the hospital with an acute illness. Validity evidence for CRANAPL was summarized on the basis of Messick’s unified validity framework by using four of the five sources of validity: content, response process, internal structure, and relations to other variables.17

Content Validity

The development team consisted of members who have an average of 10 years of clinical experience in hospital medicine; have studied clinical excellence and clinical reasoning; and have expertise in feedback, assessment, and professional development.18-22 The development of the CRANAPL tool by the team was informed by a review of the clinical reasoning literature, with particular attention paid to the standards and competencies outlined by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the Association of American Medical Colleges, the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education, the Internal Medicine Milestone Project, and the Society of Hospital Medicine.23-26 For each of these parties, diagnostic reasoning and its impact on clinical decision-making are considered to be a core competency. Several works that heavily influenced the CRANAPL tool’s development were Baker’s Interpretive Summary, Differential Diagnosis, Explanation of Reasoning, And Alternatives (IDEA) assessment tool;14 King’s Pediatric History and Physical Exam Evaluation (P-HAPEE) rubric;15 and three other studies related to diagnostic reasoning.16,27,28 These manuscripts and other works substantively informed the preliminary behavioral-based anchors that formed the initial foundation for the tool under development. The CRANAPL tool was shown to colleagues at other institutions who are leaders on clinical reasoning and was presented at academic conferences in the Division of General Internal Medicine and the Division of Hospital Medicine of our institution. Feedback resulted in iterative revisions. The aforementioned methods established content validity evidence for the CRANAPL tool.

Response Process Validity

Several of the authors pilot-tested earlier iterations on admission notes that were excluded from the sample when refining the CRANAPL tool. The weaknesses and sources of confusion with specific items were addressed by scoring 10 A&Ps individually and then comparing data captured on the tool. This cycle was repeated three times for the iterative enhancement and finalization of the CRANAPL tool. On several occasions when two authors were piloting the near-final CRANAPL tool, a third author interviewed each of the two authors about reactivity while assessing individual items and exploring with probes how their own clinical documentation practices were being considered when scoring the notes. The reasonable and thoughtful answers provided by the two authors as they explained and justified the scores they were selecting during the pilot testing served to confer response process validity evidence.

Finalizing the CRANAPL Tool

The nine-item CRANAPL tool includes elements for problem representation, leading diagnosis, uncertainty, differential diagnosis, plans for diagnosis and treatment, estimated length of stay (LOS), potential for upgrade in status to a higher level of care, and consideration of disposition. Although the final three items are not core clinical reasoning domains in the medical education literature, they represent clinical judgments that are especially relevant for the delivery of the high-quality and cost-effective care of hospitalized patients. Given that the probabilities and estimations of these three elements evolve over the course of any hospitalization on the basis of test results and response to therapy, the documentation of initial expectations on these fronts can facilitate distributed cognition with all individuals becoming wiser from shared insights.10 The tool uses two- and three-point rating scales, with each number score being clearly defined by specific written criteria (total score range: 0-14; Appendix).

Data Collection

Hospitalists’ admission notes from the three hospitals were used to validate the CRANAPL tool. Admission notes from patients hospitalized to the general medical floors with an admission diagnosis of either fever, syncope/dizziness, or abdominal pain were used. These diagnoses were purposefully examined because they (1) have a wide differential diagnosis, (2) are common presenting symptoms, and (3) are prone to diagnostic errors.29-32

The centralized EHR system across the three hospitals identified admission notes with one of these primary diagnoses of patients admitted over the period of January 2014 to October 2017. We submitted a request for 650 admission notes to be randomly selected from the centralized institutional records system. The notes were stratified by hospital and diagnosis. The sample size of our study was comparable with that of prior psychometric validation studies.33,34 Upon reviewing the A&Ps associated with these admissions, 365 notes were excluded for one of three reasons: (1) the note was written by a nurse practitioner, physician assistant, resident, or medical student; (2) the admission diagnosis had been definitively confirmed in the emergency department (eg, abdominal pain due to diverticulitis seen on CT); and (3) the note represented the fourth or more note by any single provider (to sample notes of many providers, no more than three notes written by any single provider were analyzed). A total of 285 admission notes were ultimately included in the sample.

Data were deidentified, and the A&P sections of the admission notes were each copied from the EHR into a unique Word document. Patient and hospital demographic data (including age, gender, race, number of comorbid conditions, LOS, hospital charges, and readmission to the same health system within 30 days) were collected separately from the EHR. Select physician characteristics were also collected from the hospitalist groups at each of the three hospitals, as was the length (word count) of each A&P.

The study was approved by our institutional review board.

Data Analysis

Two authors scored all deidentified A&Ps by using the finalized version of the CRANAPL tool. Prior to using the CRANAPL tool on each of the notes, these raters read each A&P and scored them by using two single-item rating scales: a global clinical reasoning and a global readability/clarity measure. Both of these global scales used three-item Likert scales (below average, average, and above average). These global rating scales collected the reviewers’ gestalt about the quality and clarity of the A&P. The use of gestalt ratings as comparators is supported by other research.35

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. Each rater rescored a sample of 48 records (one month after the initial scoring) and intraclass correlations (ICCs) were computed for intrarater reliability. ICCs were calculated for each item and for the CRANAPL total to determine interrater reliability.

The averaged ratings from the two raters were used for all other analyses. For CRANAPL’s internal structure validity evidence, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as a measure of internal consistency. For relations to other variables validity evidence, CRANAPL total scores were compared with the two global assessment variables with linear regressions.

Bivariate analyses were performed by applying parametric and nonparametric tests as appropriate. A series of multivariate linear regressions, controlling for diagnosis and clustered variance by hospital site, were performed using CRANAPL total as the dependent variable and patient variables as predictors.

All data were analyzed using Stata (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP.)

RESULTS

The admission notes of 120 hospitalists were evaluated (Table 1). A total of 39 (33%) physicians were moonlighters with primary appointments outside of the hospitalist division, and 81 (68%) were full-time hospitalists. Among the 120 hospitalists, 48 (40%) were female, 60 (50%) were international medical graduates, and 90 (75%) were of nonwhite race. Most hospitalist physicians (n = 47, 58%) had worked in our health system for less than five years, and 64 hospitalists (53%) devoted greater than 50% of their time to patient care.

Approximately equal numbers of patient admission notes were pulled from each of the three hospitals. The average age of patients was 67.2 (SD 13.6) years, 145 (51%) were female, and 120 (42%) were of nonwhite race. The mean LOS for all patients was 4.0 (SD 3.4) days. A total of 44 (15%) patients were readmitted to the same health system within 30 days of discharge. None of the patients died during the incident hospitalization. The average charge for each of the hospitalizations was $10,646 (SD $9,964).

CRANAPL Data

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the scores given by each rater for each of the nine items. The mean of the total CRANAPL score given by both raters was 6.4 (SD 2.2). Scoring for some items were high (eg, summary statement: 1.5/2), whereas performance on others were low (eg, estimating LOS: 0.1/1 and describing the potential need for upgrade in care: 0.0/1).

Validity of the CRANAPL Tool’s Internal Structure

Cronbach’s alpha, which was used to measure internal consistency within the CRANAPL tool, was 0.43. The ICC, which was applied to measure the interrater reliability for both raters for the total CRANAPL score, was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.76-0.87). The ICC values for intrarater reliability for raters 1 and 2 were 0.73 (95% CI: 0.60-0.83) and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.45-0.86), respectively.

Relations to Other Variables Validity

Associations between CRANAPL total scores, global clinical reasoning, and global scores for note readability/clarity were statistically significant (P < .001), Figure 2.

Eight out of nine CRANAPL variables were statistically significantly different across the three hospitals (P <. 01) when data were analyzed by hospital site. Hospital C had the highest mean score of 7.4 (SD 2.0), followed by Hospital B with a score of 6.6 (SD 2.1), and Hospital A had the lowest total CRANAPL score of 5.2 (SD 1.9). This difference was statistically significant (P < .001). Five variables with respect to admission diagnoses (uncertainty acknowledged, differential diagnosis, plan for diagnosis, plan for treatment, and upgrade plan) were statistically significantly different across notes. Notes for syncope/dizziness generally yielded higher scores than those for abdominal pain and fever.

Factors Associated with High CRANAPL Scores

Table 2 shows the associations between CRANAPL scores and several covariates. Before adjustment, high CRANAPL scores were associated with high word counts of A&Ps (P < .001) and high hospital charges (P < .05). These associations were no longer significant after adjusting for hospital site and admitting diagnoses.

DISCUSSION

We reviewed the documentation of clinical reasoning in 285 admission notes at three different hospitals written by hospitalist physicians during routine clinical care. To our knowledge, this is the first study that assessed the documentation of hospitalists’ clinical reasoning with real patient notes. Wide variability exists in the documentation of clinical reasoning within the A&Ps of hospitalists’ admission notes. We have provided validity evidence to support the use of the user-friendly CRANAPL tool.

Prior studies have described rubrics for evaluating the clinical reasoning skills of medical students.14,15 The ICCs for the IDEA rubric used to assess medical students’ documentation of clinical reasoning were fair to moderate (0.29-0.67), whereas the ICC for the CRANAPL tool was high at 0.83. This measure of reliability is similar to that for the P-HAPEE rubric used to assess medical students’ documentation of pediatric history and physical notes.15 These data are markedly different from the data in previous studies that have found low interrater reliability for psychometric evaluations related to judgment and decision-making.36-39 CRANAPL was also found to have high intrarater reliability, which shows the reproducibility of an individual’s assessment over time. The strong association between the total CRANAPL score and global clinical reasoning assessment found in the present study is similar to that found in previous studies that have also embedded global rating scales as comparators when assessing clinical reasoning.13,,15,40,41 Global rating scales represent an overarching structure for comparison given the absence of an accepted method or gold standard for assessing clinical reasoning documentation. High-quality provider notes are defined by clarity, thoroughness, and accuracy;35 and effective documentation promotes communication and the coordination of care among the members of the care team.3

The total CRANAPL scores varied by hospital site with academic hospitals (B and C) scoring higher than the community hospital (A) in our study. Similarly, lengthy A&Ps were associated with high CRANAPL scores (P < .001) prior to adjustment for hospital site. Healthcare providers consider that the thoroughness of documentation denotes quality and attention to detail.35,42 Comprehensive documentation takes time; the longer notes by academic hospitalists than those by community hospitalists may be attributed to the fewer number of patients generally carried by hospitalists at academic centers than that by hospitalists at community hospitals.43

The documentation of the estimations of LOS, possibility of potential upgrade, and thoughts about disposition were consistently poorly described across all hospital sites and diagnoses. In contrast to CRANAPL, other clinical reasoning rubrics have excluded these items or discussed uncertainty.14,15,44 These elements represent the forward thinking that may be essential for high-quality progressive care by hospitalists. Physicians’s difficulty in acknowledging uncertainty has been associated with resource overuse, including the excessive ordering of tests, iatrogenic injury, and heavy financial burden on the healthcare system.45,46 The lack of thoughtful clinical and management reasoning at the time of admission is believed to be associated with medical errors.47 If used as a guide, the CRANAPL tool may promote reflection on the part of the admitting physician. The estimations of LOS, potential for upgrade to a higher level of care, and disposition are markers of optimal inpatient care, especially for hospitalists who work in shifts with embedded handoffs. When shared with colleagues (through documentation), there is the potential for distributed cognition10 to extend throughout the social network of the hospitalist group. The fact that so few providers are currently including these items in their A&P’s show that the providers are either not performing or documenting the ‘reasoning’. Either way, this is an opportunity that has been highlighted by the CRANAPL tool.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, the CRANAPL tool may not have captured elements of optimal clinical reasoning documentation. The reliance on multiple methods and an iterative process in the refinement of the CRANAPL tool should have minimized this. Second, this study was conducted across a single healthcare system that uses the same EHR; this EHR or institutional culture may influence documentation practices and behaviors. Given that using the CRANAPL tool to score an A&P is quick and easy, the benefit of giving providers feedback on their notes remains to be seen—here and at other hospitals. Third, our sample size could limit the generalizability of the results and the significance of the associations. However, the sample assessed in our study was significantly larger than that assessed in other studies that have validated clinical reasoning rubrics.14,15 Fourth, clinical reasoning is a broad and multidimensional construct. The CRANAPL tool focuses exclusively on hospitalists’ documentation of clinical reasoning and therefore does not assess aspects of clinical reasoning occurring in the physicians’ minds. Finally, given our goal to optimally validate the CRANAPL tool, we chose to test the tool on specific presentations that are known to be associated with diagnostic practice variation and errors. We may have observed different results had we chosen a different set of diagnoses from each hospital. Further validity evidence will be established when applying the CRANPL tool to different diagnoses and to notes from other clinical settings.

In conclusion, this study focuses on the development and validation of the CRANAPL tool that assesses how hospitalists document their clinical reasoning in the A&P section of admission notes. Our results show that wide variability exists in the documentation of clinical reasoning by hospitalists within and across hospitals. Given the CRANAPL tool’s ease-of-use and its versatility, hospitalist divisions in academic and nonacademic settings may use the CRANAPL tool to assess and provide feedback on the documentation of hospitalists’ clinical reasoning. Beyond studying whether physicians can be taught to improve their notes with feedback based on the CRANAPL tool, future studies may explore whether enhancing clinical reasoning documentation may be associated with improvements in patient care and clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wright is the Anne Gaines and G. Thomas Miller Professor of Medicine which is supported through Hopkins’ Center for Innovative Medicine.

The authors thank Christine Caufield-Noll, MLIS, AHIP (Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland) for her assistance with this project.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. State of Hospital Medicine. Society of Hospital Medicine. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/. Accessed August 19, 2018.

2. Mehta R, Radhakrishnan NS, Warring CD, et al. The use of evidence-based, problem-oriented templates as a clinical decision support in an inpatient electronic health record system. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(3):790-802. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2015-11-RA-0164

3. Improving Diagnosis in Healthcare: Health and Medicine Division. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2015/Improving-Diagnosis-in-Healthcare.aspx. Accessed August 7, 2018.

4. Tipping MD, Forth VE, O’Leary KJ, et al. Where did the day go? A time-motion study of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):323-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.790

5. Varpio L, Rashotte J, Day K, King J, Kuziemsky C, Parush A. The EHR and building the patient’s story: a qualitative investigation of how EHR use obstructs a vital clinical activity. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(12):1019-1028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.09.004

6. Clynch N, Kellett J. Medical documentation: part of the solution, or part of the problem? A narrative review of the literature on the time spent on and value of medical documentation. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(4):221-228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.12.001

7. Varpio L, Day K, Elliot-Miller P, et al. The impact of adopting EHRs: how losing connectivity affects clinical reasoning. Med Educ. 2015;49(5):476-486. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12665

8. McBee E, Ratcliffe T, Schuwirth L, et al. Context and clinical reasoning: understanding the medical student perspective. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(4):256-263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0417-x

9. Brown PJ, Marquard JL, Amster B, et al. What do physicians read (and ignore) in electronic progress notes? Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5(2):430-444. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2014-01-RA-0003

10. Katherine D, Shalin VL. Creating a common trajectory: Shared decision making and distributed cognition in medical consultations. https://pxjournal.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1116&context=journal Accessed April 4, 2019.

11. Harchelroad FP, Martin ML, Kremen RM, Murray KW. Emergency department daily record review: a quality assurance system in a teaching hospital. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1988;14(2):45-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0097-5990(16)30187-7.

12. Opila DA. The impact of feedback to medical housestaff on chart documentation and quality of care in the outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):352-356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-5083-8.

13. Smith S, Kogan JR, Berman NB, Dell MS, Brock DM, Robins LS. The development and preliminary validation of a rubric to assess medical students’ written summary statements in virtual patient cases. Acad Med. 2016;91(1):94-100. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000800

14. Baker EA, Ledford CH, Fogg L, Way DP, Park YS. The IDEA assessment tool: assessing the reporting, diagnostic reasoning, and decision-making skills demonstrated in medical students’ hospital admission notes. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(2):163-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1011654

15. King MA, Phillipi CA, Buchanan PM, Lewin LO. Developing validity evidence for the written pediatric history and physical exam evaluation rubric. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(1):68-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.001

16. Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9):S63-S67.

17. Messick S. Standards of validity and the validity of standards in performance asessment. Educ Meas Issues Pract. 2005;14(4):5-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.1995.tb00881.x

18. Menachery EP, Knight AM, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Physician characteristics associated with proficiency in feedback skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):440-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00424.x

19. Tackett S, Eisele D, McGuire M, Rotello L, Wright S. Fostering clinical excellence across an academic health system. South Med J. 2016;109(8):471-476. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000498

20. Christmas C, Kravet SJ, Durso SC, Wright SM. Clinical excellence in academia: perspectives from masterful academic clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(9):989-994. https://doi.org/10.4065/83.9.989

21. Wright SM, Kravet S, Christmas C, Burkhart K, Durso SC. Creating an academy of clinical excellence at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center: a 3-year experience. Acad Med. 2010;85(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181fa416c

22. Kotwal S, Peña I, Howell E, Wright S. Defining clinical excellence in hospital medicine: a qualitative study. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37(1):3-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000145

23. Common Program Requirements. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements. Accessed August 21, 2018.

24. Warren J, Lupi C, Schwartz ML, et al. Chief Medical Education Officer.; 2017. https://www.aamc.org/download/482204/data/epa9toolkit.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

25. Th He Inte. https://www.abim.org/~/media/ABIM Public/Files/pdf/milestones/internal-medicine-milestones-project.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2018.

26. Core Competencies. Society of Hospital Medicine. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/professional-development/core-competencies/. Accessed August 21, 2018.

27. Bowen JL. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. Cox M,

28. Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199911000-00012.

29. Rao G, Epner P, Bauer V, Solomonides A, Newman-Toker DE. Identifying and analyzing diagnostic paths: a new approach for studying diagnostic practices. Diagnosis Berlin, Ger. 2017;4(2):67-72. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2016-0049

30. Ely JW, Kaldjian LC, D’Alessandro DM. Diagnostic errors in primary care: lessons learned. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(1):87-97. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110174

31. Kerber KA, Newman-Toker DE. Misdiagnosing dizzy patients: common pitfalls in clinical practice. Neurol Clin. 2015;33(3):565-75, viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.009

32. Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer AND, Forjuoh SN, Reis MD, Thomas EJ. Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):418. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2777.

33. Kahn D, Stewart E, Duncan M, et al. A prescription for note bloat: an effective progress note template. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):378-382. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2898

34. Anthoine E, Moret L, Regnault A, Sébille V, Hardouin J-B. Sample size used to validate a scale: a review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-014-0176-2

35. Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, Siegler EL. Assessing electronic note quality using the physician documentation quality instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(2):164-174. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2011-11-RA-0070