User login

Impact of Continuous Glucose Monitoring for American Indian/Alaska Native Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Not Using Insulin

Impact of Continuous Glucose Monitoring for American Indian/Alaska Native Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Not Using Insulin

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a national health crisis affecting > 38 million people (11.6%) in the United States.1 American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) adults are disproportionately affected, with a prevalence of 14.5%—the highest among all racial and ethnic groups.1 Type 2 DM (T2DM) accounts for 90% to 95% of all DM cases and is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality due to its association with cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, and other complications.2

Maintaining glycemic control is important for managing T2DM and preventing microvascular and macrovascular complications.3 The cornerstone of diabetes self-management has been patient self-monitored blood glucose (SMBG) using finger-stick glucometers.4 However, SMBG provides measurements from a single point in time and requires frequent, painful, and inconvenient finger pricks, leading to decreased adherence.5,6 These limitations negatively affect patient engagement and overall glycemic control.7

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) offer real-time, continuous glucose readings and trends.8 CGMs improve glycemic control and reduce hypoglycemic episodes in patients who are insulin-dependent.9,10 Flash glucose monitors, a type of CGM that requires scanning to obtain glucose readings, provide similar benefits.11 Despite these demonstrated advantages, research has primarily focused on insulin-dependent populations, leaving a significant gap in understanding the effect of CGMs on patients with T2DM who are not insulin-dependent.12

Given the high prevalence of T2DM among AI/AN populations and the potential benefits of CGMs, this study sought to evaluate the effect of CGM use on glycemic control and other health metrics in patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM in an AI/AN population. This focus addresses a critical knowledge gap and may inform clinical practices and policies to improve diabetes management in this high-risk group.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was conducted using deidentified electronic health records (EHRs) from 2019 to 2024 at a federally operated outpatient Indian Health Service (IHS) clinic serving an AI/AN population in the IHS Portland Area (Oregon, Washington, Idaho). The study protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by institutional review boards at Washington State University and the Portland Area IHS.

Study Population

This study included patients diagnosed with non–insulin-dependent T2DM, had used a CGM for ≥ 1 year, and had hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measurements within 4 months prior to CGM initiation (baseline) and within ± 4 months after 1 year of CGM use. For other health metrics, including blood pressure (BP), weight, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), this study required measurements within 6 months before CGM initiation and within 6 months after 1 year of CGM use. The baseline HbA1c in the dataset ranged from 5.3% to > 14%.

Patients were excluded if they used insulin during the study period, had incomplete laboratory or clinical data for the required time frame, or had < 1 year of CGM use. The dataset did not include detailed information on oral DM medications; thus, we could not report or account for the type or number of oral hypoglycemic agents used by the patients. The IHS clinical applications coordinator compiled the dataset from the EHR, identifying patients who were prescribed and received a CGM at the clinic. All patients used the Abbott Freestyle Libre CGM, the only formulary CGM available at the clinic during the study period.

A 1-year follow-up endpoint was selected for several reasons: (1) to capture potential seasonal variations in diet and activity; (2) to align with the clinic’s standard practice of annual comprehensive diabetes evaluations; and (3) to allow sufficient time for patients to adapt to CGM use and reflect any meaningful changes in glycemic control.

All patients received standard DM care according to clinic protocols, which included DM self-management education and training. Patients met with the diabetes educator at least once, during which the educator emphasized making informed decisions using CGM data, such as adjusting dietary choices and physical activity levels to manage blood glucose concentrations effectively.

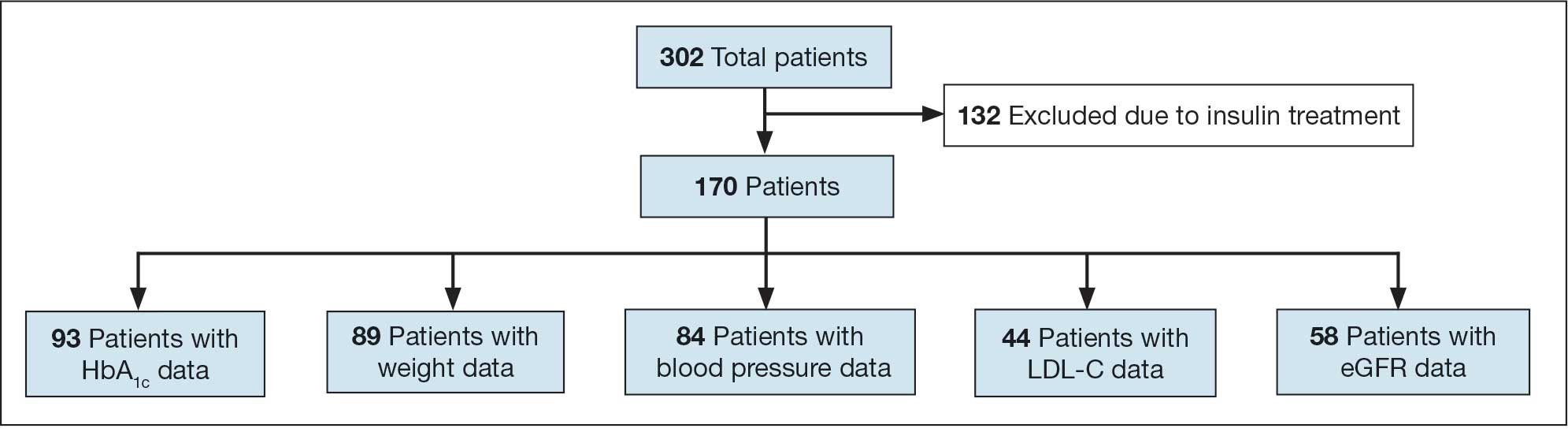

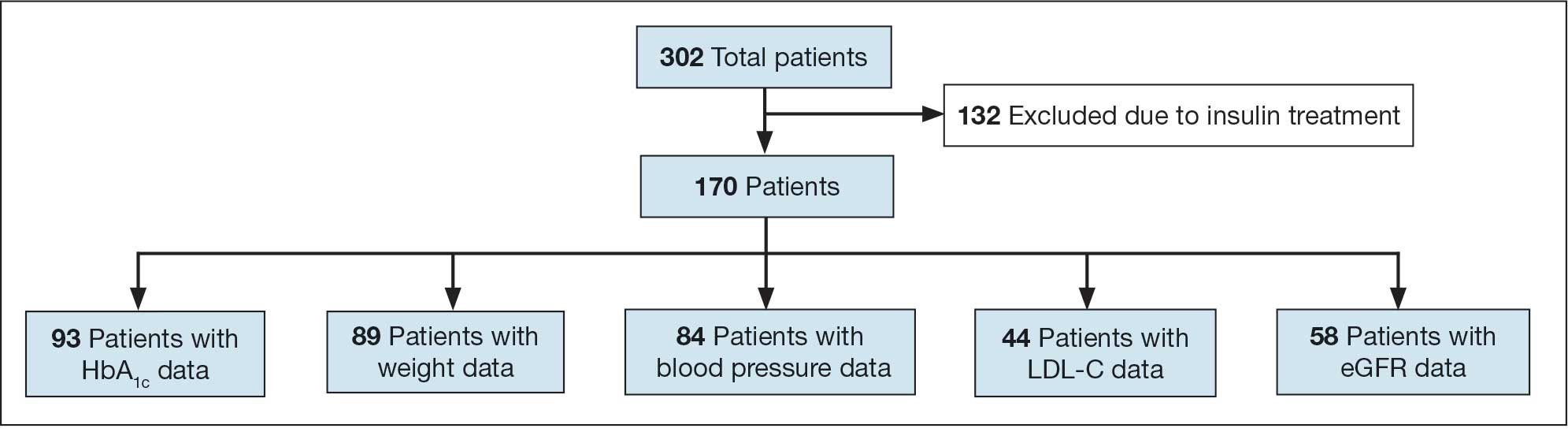

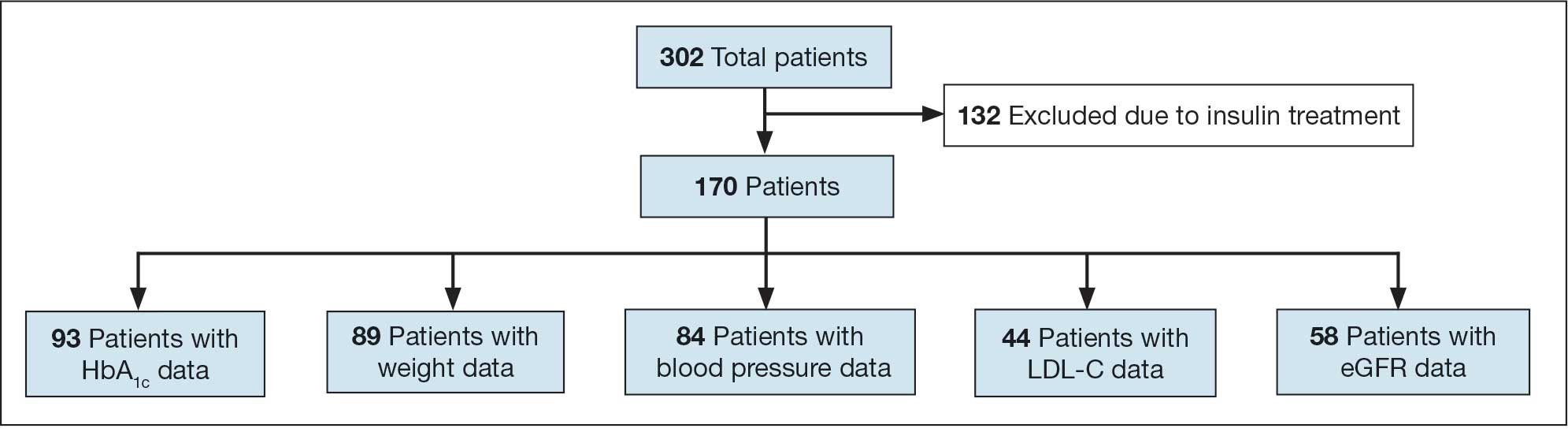

A total of 302 patients were initially identified. After applying exclusion criteria, 132 were excluded due to insulin use, and 77 were excluded due to incomplete HbA1c data within the specified time frames (Figure 1). The final sample included 93 patients.

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Measures

The primary outcome was the change in HbA1c levels from baseline to 1 year after CGM initiation. Secondary outcomes included changes in weight, systolic and diastolic BP, LDL-C concentrations, and eGFR. For the primary outcome, HbA1c values were collected within a grace period of ± 4 months from the baseline and 1-year time points. The laboratory’s upper reporting limit for HbA1c was 14%; values reported as “> 14%” were recorded as 14.1% for data analysis, although the actual values could have been higher.

For secondary outcomes, data were included if measurements were obtained within ± 6 months of the baseline and 1-year time points. Patients who did not have measurements within these time frames for specific metrics were excluded from secondary outcome analysis but remained in the overall study if they met the criteria for HbA1c and CGM use.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software version 4.4.2. Paired t tests were conducted to compare baseline and 1-year follow- up measurements for variables with parametric distributions. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for nonparametric data. A linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between baseline HbA1c levels and the change in HbA1c after 1 year of CGM use. Differences were considered significant at P < .05 set a priori. To guide future research, a posthoc power analysis was performed using Cohen’s d to estimate the required sample sizes for detecting significant effects, assuming a similar population.

Results

The study included 93 patients, with a mean (SD) age of 55 (13) years (range, 29-83 years). Of the participants, 56 were female (60%) and 37 were male (40%). All participants were identified as AI/AN and had non–insulin-dependent T2DM.

Primary Outcomes

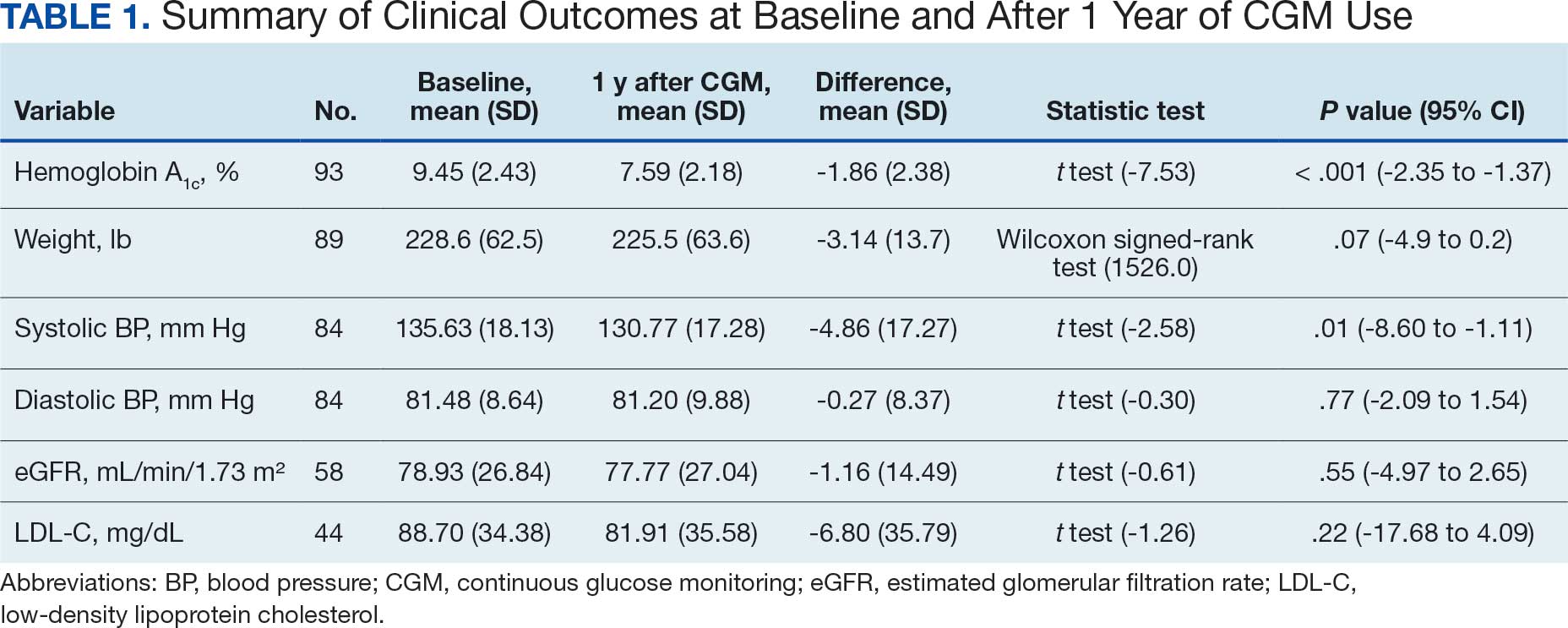

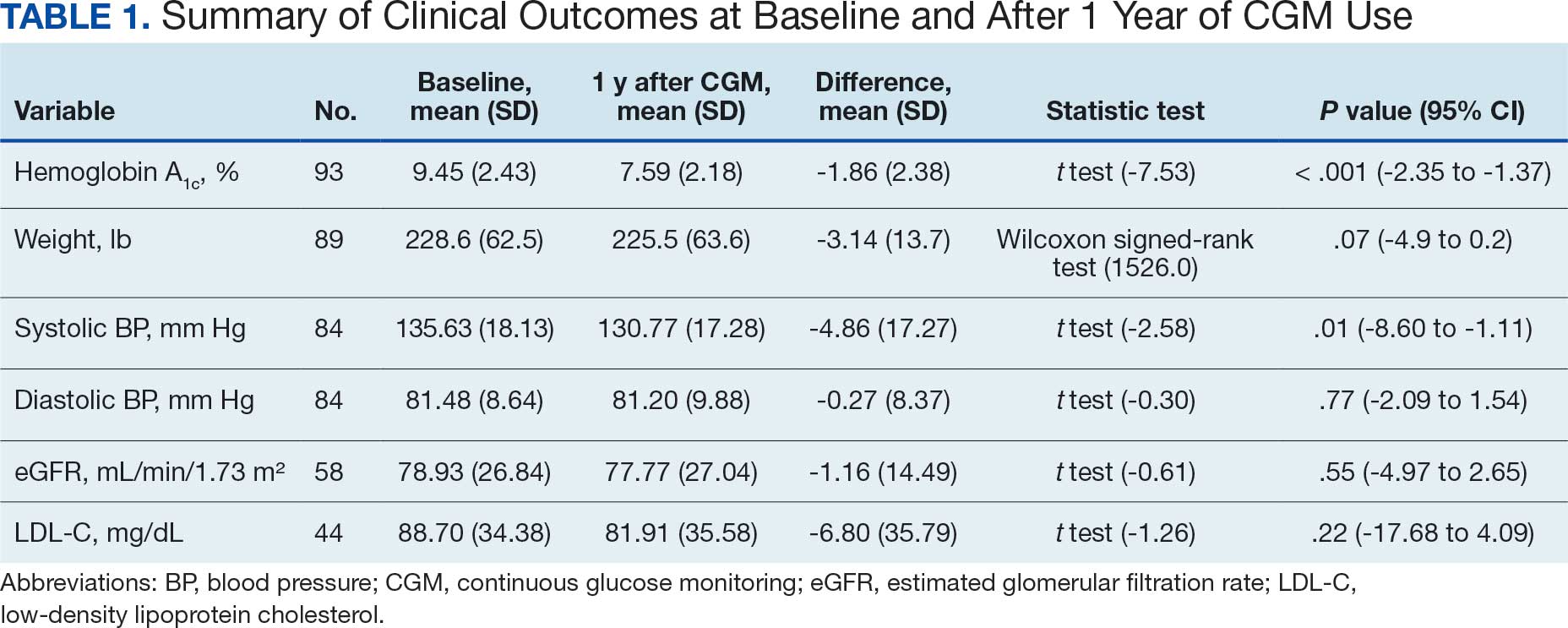

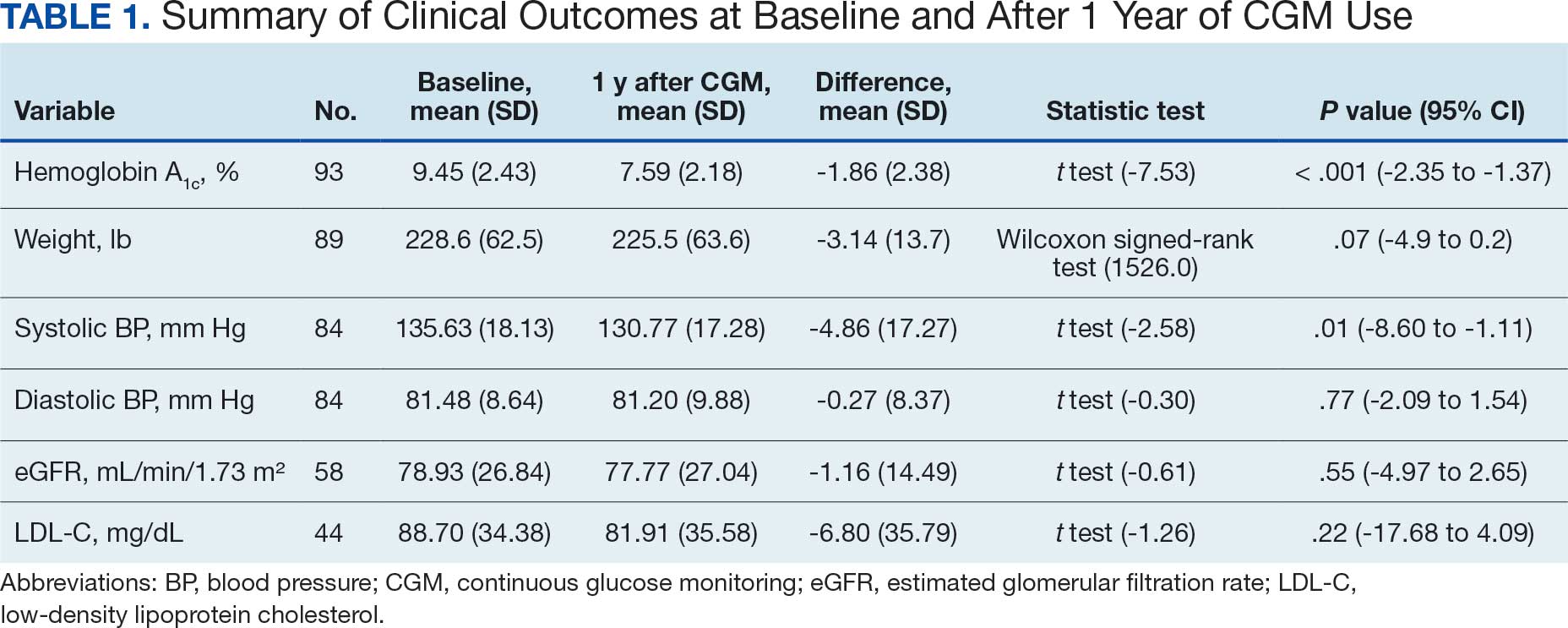

A significant reduction in HbA1c levels was observed after 1 year of CGM use. The mean (SD) baseline HbA1c was 9.5% (2.4%), which decreased to 7.6% (2.2%) at 1-year follow-up (Table 1). This difference represents a mean change of -1.86% (2.4%) (95% CI, -2.35 to -1.37; P < .001 [paired t test, -7.53]).

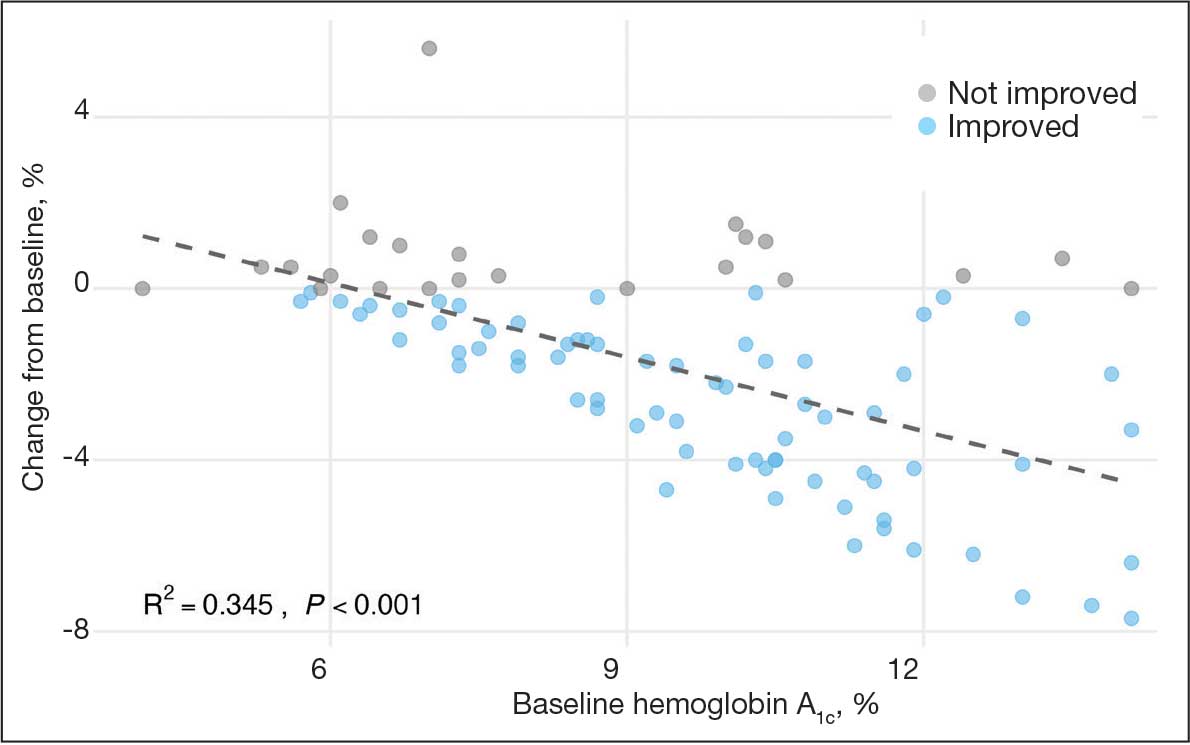

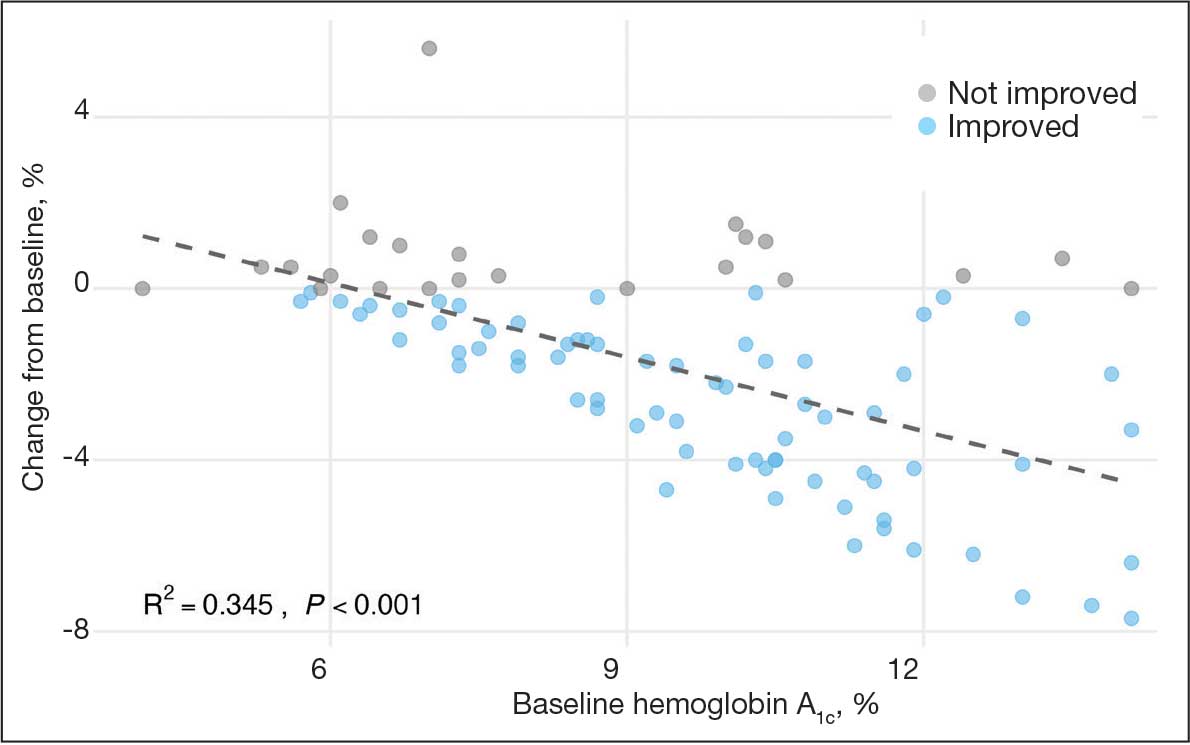

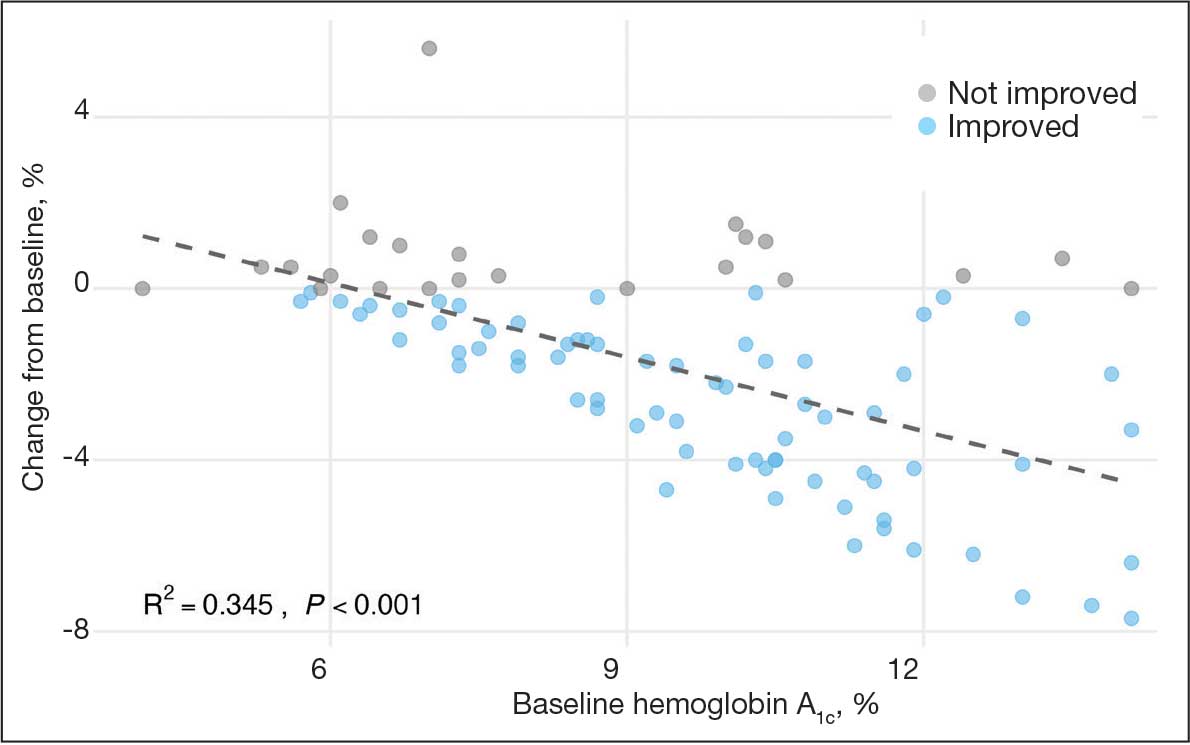

A linear regression model evaluated the relationship between baseline HbA1c (predictor) and the change in HbA1c after 1 year (outcome). The change in HbA1c was calculated as the difference between 1-year follow-up and baseline values. The regression model revealed a significant negative association between baseline HbA1c and the change in HbA1c (Β = -0.576; P < .001), indicating that higher baseline HbA1c values were associated with greater reductions in HbA1c over the year. The regression equation was: Change in HbA1c = 3.587 – 0.576 × Baseline HbA1c

The regression coefficient for baseline HbA1c was -0.576 (standard error, 0.083; t = -6.931; P < .001), indicating that for each 1% increase in baseline HbA1c, the reduction of HbA1c after 1 year increased by approximately 0.576% (Figure 2). The model explained 34.6% of the variance in HbA1c change (R2 = .345; adjusted R2 = .338).

Secondary Outcomes

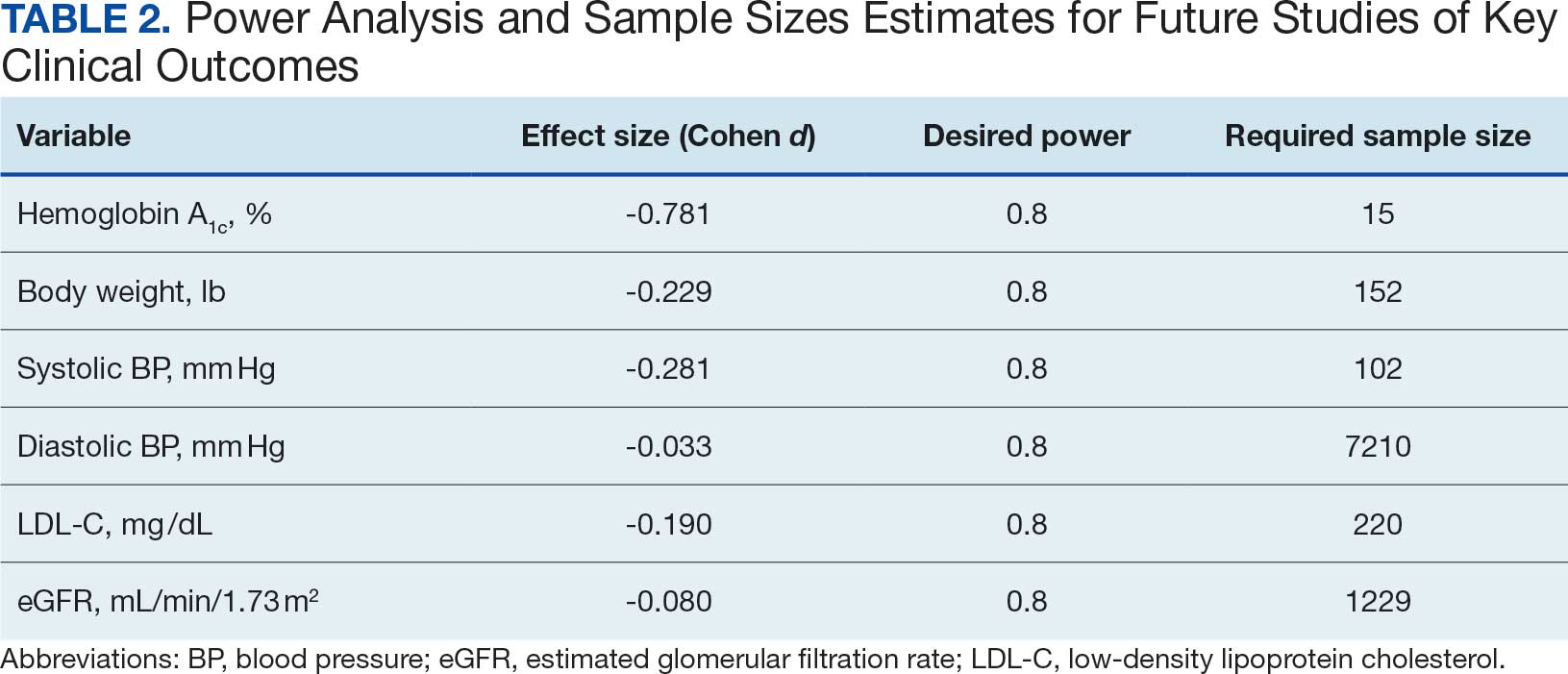

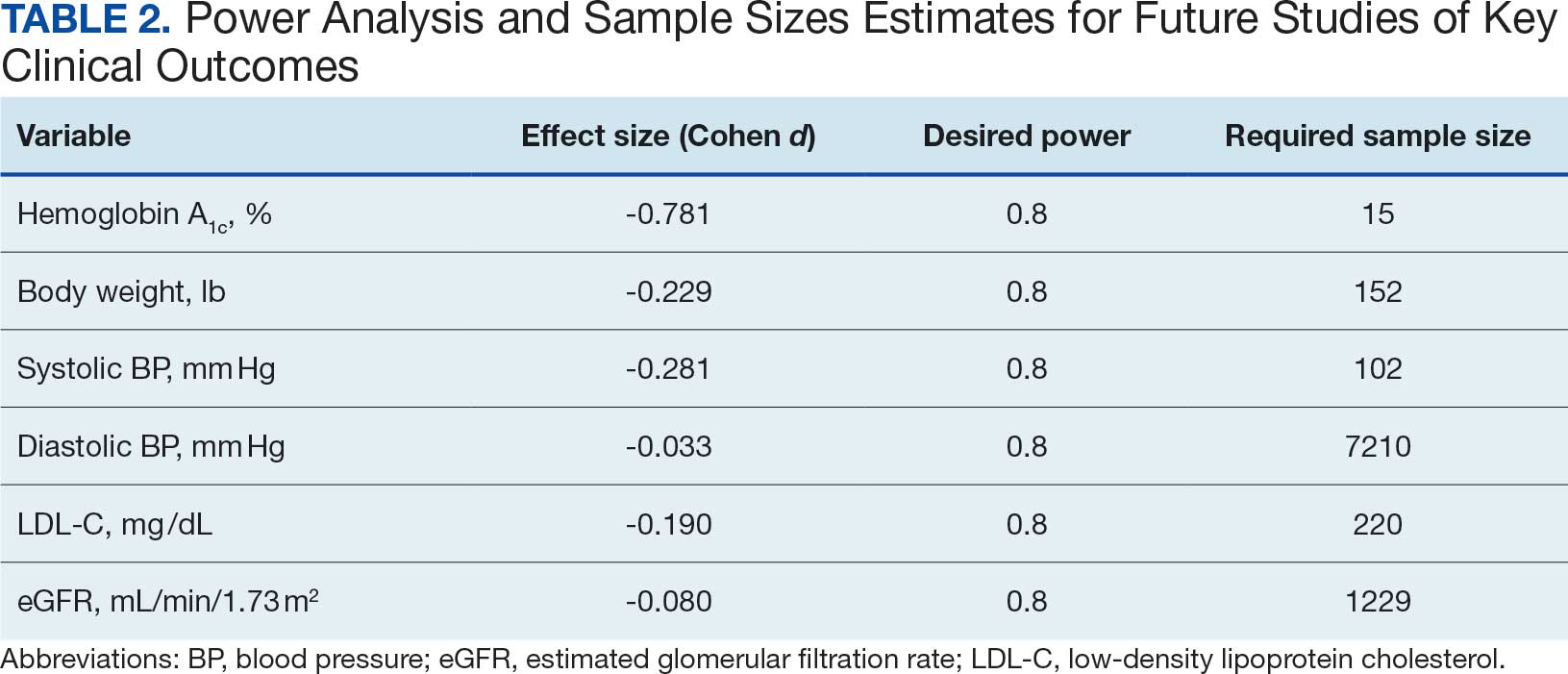

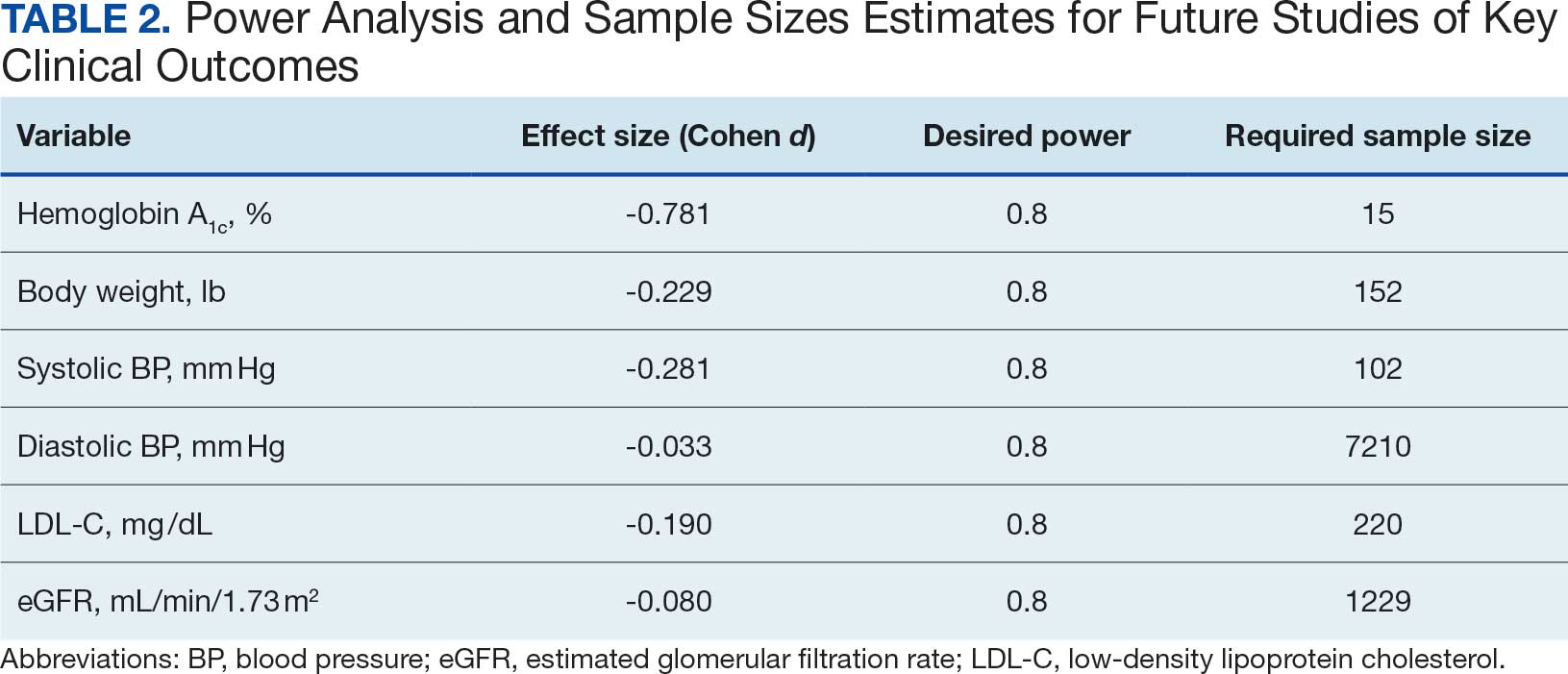

Systolic BP decreased by a mean (SD) -4.9 (17) mm Hg; 95% CI, -8.6 to -1.11; P = .01, paired t test). However, no significant change was observed for diastolic BP (P = .77, paired t test). Similarly, no significant changes were observed in weight, LDL-C concentrations, or eGFR after 1 year of CGM use. A posthoc power analysis indicated that the study was underpowered to detect smaller effect sizes in secondary outcomes. For example, sample size estimates indicated that detecting significant changes in weight and LDL-C concentrations would require sample sizes of 152 and 220 patients, respectively (Table 2).

Discussion

This study found a clinically significant reduction in HbA1c levels after 1 year among AI/AN patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM who used CGMs. The mean HbA1c decreased 1.9%, from 9.5% at baseline to 7.6% after 1 year. This reduction is not only statistically significant (P < .001), it is clinically meaningful—even a 1% decrease in HbA1c is associated with substantial reductions in the risk of microvascular complications.3 The magnitude of the HbA1c reduction observed suggests CGM use may be associated with improved glycemic control in this high-risk population. By achieving lower HbA1c levels, patients may experience improved long-term health outcomes and a reduced burden of DM-related complications.

Changes in oral DM medications during the study period may have contributed to the observed improvements in HbA1c levels. While the dataset lacked detailed information on types or dosages of oral hypoglycemic agents used, adjustments in medication regimens are common in DM management and could significantly affect glycemic control. The inability to account for these changes results in an inability to attribute the improvements in HbA1c solely to CGM use. Future studies should collect comprehensive medication data to better isolate the effects of CGM use from other treatment modifications.

Another factor that may have contributed to the improved glycemic control is the DM self-management education and training patients received as part of standard care. Patients met with diabetes educators at least once and learned how to use the CGM device and interpret the data for self-management decisions. This education may have enhanced patient engagement and empowerment, enabling them to make informed choices about diet, physical activity, and medication adherence. Studies have shown that DM self-management education can significantly improve glycemic control and patient outcomes.13 By combining the CGM technology with targeted education, patients may have been better equipped to manage their condition, contributing to the observed reduction in HbA1c levels. Future studies should consider synergistic effects of CGM use and DM education when evaluating interventions for glycemic control.

The significant reduction in HbA1c indicates CGM use is associated with improved glycemic control in non–insulin-dependent T2DM. The linear regression analysis suggests patients with poorer glycemic control at baseline experienced greater reductions in HbA1c over the course of 1 year. This finding aligns with previous studies that have shown greater HbA1c reductions in patients with higher initial levels when using CGMs. Yaron et al reported similar findings: higher baseline HbA1c levels predicted more substantial improvements with CGM use in patients with T2DM on insulin therapy.14

This study contributes to existing research by examining the association between CGM use and glycemic control in patients with non– insulin-dependent T2DM within an AI/AN population, a group that has been underreported in previous studies. Most prior research has focused on insulin-dependent patients or populations with different ethnic backgrounds.12 By focusing on patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM, this study highlights the broader applicability of CGMs beyond traditional use, showcasing their potential association with benefits in earlier stages of DM management. Targeting the AI/AN population addresses a critical knowledge gap, given the disproportionately high prevalence of T2DM and associated complications in this group. The findings of this study suggest integrating CGM technology into the standard care of AI/AN patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM may be associated with improved glycemic control and may help reduce health disparities.

The modest decrease in systolic BP observed in this study may indicate potential cardiovascular benefits associated with CGM use, possibly due to improved glycemic control and increased patient engagement in self-management. However, given the limited sample size and exclusion criteria, the study lacked sufficient power to detect significant associations between CGM use and other secondary outcomes such as BP, weight, LDL-C, and eGFR. Therefore, the significant finding with systolic BP should be interpreted with caution.

The lack of significant changes in secondary outcomes may be attributed to the study’s limited sample size and the relatively short duration for observing changes in these parameters. Larger studies are needed to assess the full impact of CGM on these variables. The required sample sizes for achieving adequate power in future studies were calculated, highlighting the utility of our study as a pilot, providing critical data for the design of larger, adequately powered studies.

Limitations

The retrospective design of this study limits causal inferences. Moreover, potential confounding variables were not controlled, such as changes in medication regimens (other than insulin use), dietary counseling, or physical activity. Additionally, we could not account for the type or number of oral DM medications prescribed to patients. The dataset included only information on insulin use, without detailed records of other antidiabetic medications. This limitation may have influenced the observed change in glycemic control, as variations in medication regimens could affect HbA1c levels.

Because this study lacked a comparator group, the effect of CGM use cannot be definitively isolated from other factors (eg, medication changes, dietary modifications, or physical activity). Moreover, CGM devices can be costly and are not universally covered by all insurance or IHS programs, potentially limiting widespread implementation. Policy-level restrictions and patient-specific barriers may also hinder feasibility in other settings.

The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Of the initial 302 patients, about 69% were excluded due to insulin use or incomplete laboratory data. A ± 4-month window was selected to balance data quality with real-world practices. Extending this window further (eg, ± 6 months) might have included more participants but risked diluting the 1-year endpoint consistency. The lack of statistical significance in secondary metrics may be due to insufficient power rather than the absence of an effect.

Exclusion of patients due to incomplete data may have introduced selection bias. However, patients were included in the overall analysis if they met the criteria for HbA1c and CGM use, even if they lacked data for secondary outcomes. Additionally, the laboratory’s upper reporting limit for HbA1c was 14%, with values above this reported as “> 14%.” For analysis, these were recorded as 14.1%, which may underestimate the true baseline HbA1c levels and impact of the assessment of change. This occurred for 4 of the 93 patients included.

All patients used the Freestyle Libre CGM, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other CGM brands or models. Differences in device features, accuracy, scanning frequency, and user experience may influence outcomes, and results might differ with other CGM technologies. The dataset did not include patients’ scanning frequency because this metric was not consistently included in the EHRs.

Conclusions

This study found that CGM use was significantly associated with improved glycemic control in patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM within an AI/AN population, particularly among patients with higher baseline HbA1c levels. The findings suggest that CGMs may be a valuable tool for managing T2DM beyond insulin-dependent populations.

Additional research with larger sample sizes, control groups, and extended follow-up periods is recommended to explore long-term benefits and impacts on other health metrics. The sample size estimates derived from this study serve as a valuable resource for researchers designing future studies aimed at addressing these gaps. Future research that expands on our findings by including larger, more diverse cohorts, accounting for medication use, and exploring different CGM technologies will enhance understanding and contribute to more effective diabetes management strategies for varied populations.

- National diabetes statistics report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 15, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html

- Elsayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S19-S40. doi:10.2337/dc23-S002

- Fowler MJ. Microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2011;29:116-122. doi:10.2337/diaclin.29.3.116

- Pleus S, Freckmann G, Schauer S, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose as an integral part in the management of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13:829-846. doi:10.1007/s13300-022-01254-8

- Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Schikman CH, et al. Structured self-monitoring of blood glucose significantly reduces A1C levels in poorly controlled, noninsulin-treated type 2 diabetes: results from the Structured Testing Program study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:262-267. doi:10.2337/dc10-1732

- Tanaka N, Yabe D, Murotani K, et al. Mental distress and health-related quality of life among type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients using self-monitoring of blood glucose: a cross-sectional questionnaire study in Japan. J Diabetes Investig. 2018;9:1203-1211. doi:10.1111/jdi.12827

- Hortensius J, Kars MC, Wierenga WS, et al. Perspectives of patients with type 1 or insulin-treated type 2 diabetes on self-monitoring of blood glucose: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:167. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-167

- Didyuk O, Econom N, Guardia A, Livingston K, Klueh U. Continuous glucose monitoring devices: past, present, and future focus on the history and evolution of technological innovation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2021;15:676-683. doi:10.1177/1932296819899394

- Beck RW, Riddlesworth TD, Ruedy K, et al. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:371-378. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.19975

- Lind M, Polonsky W, Hirsch IB, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring vs conventional therapy for glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes treated with multiple daily insulin injections: the GOLD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:379-387. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.19976

- Bolinder J, Antuna R, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn P, et al. Novel glucose-sensing technology and hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes: a multicenter, non-masked, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2254-2263. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31535-5

- Seidu S, Kunutsor SK, Ajjan RA, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous glucose monitoring and intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional evidence. Diabetes Care. 2024;47:169-179. doi:10.2337/dc23-1520

- ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S68-S96. doi:10.2337/dc23-S005

- Yaron M, Roitman E, Aharon-Hananel G, et al. Effect of flash glucose monitoring technology on glycemic control and treatment satisfaction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1178-1184. doi:10.2337/dc18-0166

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a national health crisis affecting > 38 million people (11.6%) in the United States.1 American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) adults are disproportionately affected, with a prevalence of 14.5%—the highest among all racial and ethnic groups.1 Type 2 DM (T2DM) accounts for 90% to 95% of all DM cases and is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality due to its association with cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, and other complications.2

Maintaining glycemic control is important for managing T2DM and preventing microvascular and macrovascular complications.3 The cornerstone of diabetes self-management has been patient self-monitored blood glucose (SMBG) using finger-stick glucometers.4 However, SMBG provides measurements from a single point in time and requires frequent, painful, and inconvenient finger pricks, leading to decreased adherence.5,6 These limitations negatively affect patient engagement and overall glycemic control.7

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) offer real-time, continuous glucose readings and trends.8 CGMs improve glycemic control and reduce hypoglycemic episodes in patients who are insulin-dependent.9,10 Flash glucose monitors, a type of CGM that requires scanning to obtain glucose readings, provide similar benefits.11 Despite these demonstrated advantages, research has primarily focused on insulin-dependent populations, leaving a significant gap in understanding the effect of CGMs on patients with T2DM who are not insulin-dependent.12

Given the high prevalence of T2DM among AI/AN populations and the potential benefits of CGMs, this study sought to evaluate the effect of CGM use on glycemic control and other health metrics in patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM in an AI/AN population. This focus addresses a critical knowledge gap and may inform clinical practices and policies to improve diabetes management in this high-risk group.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was conducted using deidentified electronic health records (EHRs) from 2019 to 2024 at a federally operated outpatient Indian Health Service (IHS) clinic serving an AI/AN population in the IHS Portland Area (Oregon, Washington, Idaho). The study protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by institutional review boards at Washington State University and the Portland Area IHS.

Study Population

This study included patients diagnosed with non–insulin-dependent T2DM, had used a CGM for ≥ 1 year, and had hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measurements within 4 months prior to CGM initiation (baseline) and within ± 4 months after 1 year of CGM use. For other health metrics, including blood pressure (BP), weight, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), this study required measurements within 6 months before CGM initiation and within 6 months after 1 year of CGM use. The baseline HbA1c in the dataset ranged from 5.3% to > 14%.

Patients were excluded if they used insulin during the study period, had incomplete laboratory or clinical data for the required time frame, or had < 1 year of CGM use. The dataset did not include detailed information on oral DM medications; thus, we could not report or account for the type or number of oral hypoglycemic agents used by the patients. The IHS clinical applications coordinator compiled the dataset from the EHR, identifying patients who were prescribed and received a CGM at the clinic. All patients used the Abbott Freestyle Libre CGM, the only formulary CGM available at the clinic during the study period.

A 1-year follow-up endpoint was selected for several reasons: (1) to capture potential seasonal variations in diet and activity; (2) to align with the clinic’s standard practice of annual comprehensive diabetes evaluations; and (3) to allow sufficient time for patients to adapt to CGM use and reflect any meaningful changes in glycemic control.

All patients received standard DM care according to clinic protocols, which included DM self-management education and training. Patients met with the diabetes educator at least once, during which the educator emphasized making informed decisions using CGM data, such as adjusting dietary choices and physical activity levels to manage blood glucose concentrations effectively.

A total of 302 patients were initially identified. After applying exclusion criteria, 132 were excluded due to insulin use, and 77 were excluded due to incomplete HbA1c data within the specified time frames (Figure 1). The final sample included 93 patients.

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Measures

The primary outcome was the change in HbA1c levels from baseline to 1 year after CGM initiation. Secondary outcomes included changes in weight, systolic and diastolic BP, LDL-C concentrations, and eGFR. For the primary outcome, HbA1c values were collected within a grace period of ± 4 months from the baseline and 1-year time points. The laboratory’s upper reporting limit for HbA1c was 14%; values reported as “> 14%” were recorded as 14.1% for data analysis, although the actual values could have been higher.

For secondary outcomes, data were included if measurements were obtained within ± 6 months of the baseline and 1-year time points. Patients who did not have measurements within these time frames for specific metrics were excluded from secondary outcome analysis but remained in the overall study if they met the criteria for HbA1c and CGM use.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software version 4.4.2. Paired t tests were conducted to compare baseline and 1-year follow- up measurements for variables with parametric distributions. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for nonparametric data. A linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between baseline HbA1c levels and the change in HbA1c after 1 year of CGM use. Differences were considered significant at P < .05 set a priori. To guide future research, a posthoc power analysis was performed using Cohen’s d to estimate the required sample sizes for detecting significant effects, assuming a similar population.

Results

The study included 93 patients, with a mean (SD) age of 55 (13) years (range, 29-83 years). Of the participants, 56 were female (60%) and 37 were male (40%). All participants were identified as AI/AN and had non–insulin-dependent T2DM.

Primary Outcomes

A significant reduction in HbA1c levels was observed after 1 year of CGM use. The mean (SD) baseline HbA1c was 9.5% (2.4%), which decreased to 7.6% (2.2%) at 1-year follow-up (Table 1). This difference represents a mean change of -1.86% (2.4%) (95% CI, -2.35 to -1.37; P < .001 [paired t test, -7.53]).

A linear regression model evaluated the relationship between baseline HbA1c (predictor) and the change in HbA1c after 1 year (outcome). The change in HbA1c was calculated as the difference between 1-year follow-up and baseline values. The regression model revealed a significant negative association between baseline HbA1c and the change in HbA1c (Β = -0.576; P < .001), indicating that higher baseline HbA1c values were associated with greater reductions in HbA1c over the year. The regression equation was: Change in HbA1c = 3.587 – 0.576 × Baseline HbA1c

The regression coefficient for baseline HbA1c was -0.576 (standard error, 0.083; t = -6.931; P < .001), indicating that for each 1% increase in baseline HbA1c, the reduction of HbA1c after 1 year increased by approximately 0.576% (Figure 2). The model explained 34.6% of the variance in HbA1c change (R2 = .345; adjusted R2 = .338).

Secondary Outcomes

Systolic BP decreased by a mean (SD) -4.9 (17) mm Hg; 95% CI, -8.6 to -1.11; P = .01, paired t test). However, no significant change was observed for diastolic BP (P = .77, paired t test). Similarly, no significant changes were observed in weight, LDL-C concentrations, or eGFR after 1 year of CGM use. A posthoc power analysis indicated that the study was underpowered to detect smaller effect sizes in secondary outcomes. For example, sample size estimates indicated that detecting significant changes in weight and LDL-C concentrations would require sample sizes of 152 and 220 patients, respectively (Table 2).

Discussion

This study found a clinically significant reduction in HbA1c levels after 1 year among AI/AN patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM who used CGMs. The mean HbA1c decreased 1.9%, from 9.5% at baseline to 7.6% after 1 year. This reduction is not only statistically significant (P < .001), it is clinically meaningful—even a 1% decrease in HbA1c is associated with substantial reductions in the risk of microvascular complications.3 The magnitude of the HbA1c reduction observed suggests CGM use may be associated with improved glycemic control in this high-risk population. By achieving lower HbA1c levels, patients may experience improved long-term health outcomes and a reduced burden of DM-related complications.

Changes in oral DM medications during the study period may have contributed to the observed improvements in HbA1c levels. While the dataset lacked detailed information on types or dosages of oral hypoglycemic agents used, adjustments in medication regimens are common in DM management and could significantly affect glycemic control. The inability to account for these changes results in an inability to attribute the improvements in HbA1c solely to CGM use. Future studies should collect comprehensive medication data to better isolate the effects of CGM use from other treatment modifications.

Another factor that may have contributed to the improved glycemic control is the DM self-management education and training patients received as part of standard care. Patients met with diabetes educators at least once and learned how to use the CGM device and interpret the data for self-management decisions. This education may have enhanced patient engagement and empowerment, enabling them to make informed choices about diet, physical activity, and medication adherence. Studies have shown that DM self-management education can significantly improve glycemic control and patient outcomes.13 By combining the CGM technology with targeted education, patients may have been better equipped to manage their condition, contributing to the observed reduction in HbA1c levels. Future studies should consider synergistic effects of CGM use and DM education when evaluating interventions for glycemic control.

The significant reduction in HbA1c indicates CGM use is associated with improved glycemic control in non–insulin-dependent T2DM. The linear regression analysis suggests patients with poorer glycemic control at baseline experienced greater reductions in HbA1c over the course of 1 year. This finding aligns with previous studies that have shown greater HbA1c reductions in patients with higher initial levels when using CGMs. Yaron et al reported similar findings: higher baseline HbA1c levels predicted more substantial improvements with CGM use in patients with T2DM on insulin therapy.14

This study contributes to existing research by examining the association between CGM use and glycemic control in patients with non– insulin-dependent T2DM within an AI/AN population, a group that has been underreported in previous studies. Most prior research has focused on insulin-dependent patients or populations with different ethnic backgrounds.12 By focusing on patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM, this study highlights the broader applicability of CGMs beyond traditional use, showcasing their potential association with benefits in earlier stages of DM management. Targeting the AI/AN population addresses a critical knowledge gap, given the disproportionately high prevalence of T2DM and associated complications in this group. The findings of this study suggest integrating CGM technology into the standard care of AI/AN patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM may be associated with improved glycemic control and may help reduce health disparities.

The modest decrease in systolic BP observed in this study may indicate potential cardiovascular benefits associated with CGM use, possibly due to improved glycemic control and increased patient engagement in self-management. However, given the limited sample size and exclusion criteria, the study lacked sufficient power to detect significant associations between CGM use and other secondary outcomes such as BP, weight, LDL-C, and eGFR. Therefore, the significant finding with systolic BP should be interpreted with caution.

The lack of significant changes in secondary outcomes may be attributed to the study’s limited sample size and the relatively short duration for observing changes in these parameters. Larger studies are needed to assess the full impact of CGM on these variables. The required sample sizes for achieving adequate power in future studies were calculated, highlighting the utility of our study as a pilot, providing critical data for the design of larger, adequately powered studies.

Limitations

The retrospective design of this study limits causal inferences. Moreover, potential confounding variables were not controlled, such as changes in medication regimens (other than insulin use), dietary counseling, or physical activity. Additionally, we could not account for the type or number of oral DM medications prescribed to patients. The dataset included only information on insulin use, without detailed records of other antidiabetic medications. This limitation may have influenced the observed change in glycemic control, as variations in medication regimens could affect HbA1c levels.

Because this study lacked a comparator group, the effect of CGM use cannot be definitively isolated from other factors (eg, medication changes, dietary modifications, or physical activity). Moreover, CGM devices can be costly and are not universally covered by all insurance or IHS programs, potentially limiting widespread implementation. Policy-level restrictions and patient-specific barriers may also hinder feasibility in other settings.

The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Of the initial 302 patients, about 69% were excluded due to insulin use or incomplete laboratory data. A ± 4-month window was selected to balance data quality with real-world practices. Extending this window further (eg, ± 6 months) might have included more participants but risked diluting the 1-year endpoint consistency. The lack of statistical significance in secondary metrics may be due to insufficient power rather than the absence of an effect.

Exclusion of patients due to incomplete data may have introduced selection bias. However, patients were included in the overall analysis if they met the criteria for HbA1c and CGM use, even if they lacked data for secondary outcomes. Additionally, the laboratory’s upper reporting limit for HbA1c was 14%, with values above this reported as “> 14%.” For analysis, these were recorded as 14.1%, which may underestimate the true baseline HbA1c levels and impact of the assessment of change. This occurred for 4 of the 93 patients included.

All patients used the Freestyle Libre CGM, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other CGM brands or models. Differences in device features, accuracy, scanning frequency, and user experience may influence outcomes, and results might differ with other CGM technologies. The dataset did not include patients’ scanning frequency because this metric was not consistently included in the EHRs.

Conclusions

This study found that CGM use was significantly associated with improved glycemic control in patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM within an AI/AN population, particularly among patients with higher baseline HbA1c levels. The findings suggest that CGMs may be a valuable tool for managing T2DM beyond insulin-dependent populations.

Additional research with larger sample sizes, control groups, and extended follow-up periods is recommended to explore long-term benefits and impacts on other health metrics. The sample size estimates derived from this study serve as a valuable resource for researchers designing future studies aimed at addressing these gaps. Future research that expands on our findings by including larger, more diverse cohorts, accounting for medication use, and exploring different CGM technologies will enhance understanding and contribute to more effective diabetes management strategies for varied populations.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a national health crisis affecting > 38 million people (11.6%) in the United States.1 American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) adults are disproportionately affected, with a prevalence of 14.5%—the highest among all racial and ethnic groups.1 Type 2 DM (T2DM) accounts for 90% to 95% of all DM cases and is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality due to its association with cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, and other complications.2

Maintaining glycemic control is important for managing T2DM and preventing microvascular and macrovascular complications.3 The cornerstone of diabetes self-management has been patient self-monitored blood glucose (SMBG) using finger-stick glucometers.4 However, SMBG provides measurements from a single point in time and requires frequent, painful, and inconvenient finger pricks, leading to decreased adherence.5,6 These limitations negatively affect patient engagement and overall glycemic control.7

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) offer real-time, continuous glucose readings and trends.8 CGMs improve glycemic control and reduce hypoglycemic episodes in patients who are insulin-dependent.9,10 Flash glucose monitors, a type of CGM that requires scanning to obtain glucose readings, provide similar benefits.11 Despite these demonstrated advantages, research has primarily focused on insulin-dependent populations, leaving a significant gap in understanding the effect of CGMs on patients with T2DM who are not insulin-dependent.12

Given the high prevalence of T2DM among AI/AN populations and the potential benefits of CGMs, this study sought to evaluate the effect of CGM use on glycemic control and other health metrics in patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM in an AI/AN population. This focus addresses a critical knowledge gap and may inform clinical practices and policies to improve diabetes management in this high-risk group.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was conducted using deidentified electronic health records (EHRs) from 2019 to 2024 at a federally operated outpatient Indian Health Service (IHS) clinic serving an AI/AN population in the IHS Portland Area (Oregon, Washington, Idaho). The study protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by institutional review boards at Washington State University and the Portland Area IHS.

Study Population

This study included patients diagnosed with non–insulin-dependent T2DM, had used a CGM for ≥ 1 year, and had hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measurements within 4 months prior to CGM initiation (baseline) and within ± 4 months after 1 year of CGM use. For other health metrics, including blood pressure (BP), weight, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), this study required measurements within 6 months before CGM initiation and within 6 months after 1 year of CGM use. The baseline HbA1c in the dataset ranged from 5.3% to > 14%.

Patients were excluded if they used insulin during the study period, had incomplete laboratory or clinical data for the required time frame, or had < 1 year of CGM use. The dataset did not include detailed information on oral DM medications; thus, we could not report or account for the type or number of oral hypoglycemic agents used by the patients. The IHS clinical applications coordinator compiled the dataset from the EHR, identifying patients who were prescribed and received a CGM at the clinic. All patients used the Abbott Freestyle Libre CGM, the only formulary CGM available at the clinic during the study period.

A 1-year follow-up endpoint was selected for several reasons: (1) to capture potential seasonal variations in diet and activity; (2) to align with the clinic’s standard practice of annual comprehensive diabetes evaluations; and (3) to allow sufficient time for patients to adapt to CGM use and reflect any meaningful changes in glycemic control.

All patients received standard DM care according to clinic protocols, which included DM self-management education and training. Patients met with the diabetes educator at least once, during which the educator emphasized making informed decisions using CGM data, such as adjusting dietary choices and physical activity levels to manage blood glucose concentrations effectively.

A total of 302 patients were initially identified. After applying exclusion criteria, 132 were excluded due to insulin use, and 77 were excluded due to incomplete HbA1c data within the specified time frames (Figure 1). The final sample included 93 patients.

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Measures

The primary outcome was the change in HbA1c levels from baseline to 1 year after CGM initiation. Secondary outcomes included changes in weight, systolic and diastolic BP, LDL-C concentrations, and eGFR. For the primary outcome, HbA1c values were collected within a grace period of ± 4 months from the baseline and 1-year time points. The laboratory’s upper reporting limit for HbA1c was 14%; values reported as “> 14%” were recorded as 14.1% for data analysis, although the actual values could have been higher.

For secondary outcomes, data were included if measurements were obtained within ± 6 months of the baseline and 1-year time points. Patients who did not have measurements within these time frames for specific metrics were excluded from secondary outcome analysis but remained in the overall study if they met the criteria for HbA1c and CGM use.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software version 4.4.2. Paired t tests were conducted to compare baseline and 1-year follow- up measurements for variables with parametric distributions. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for nonparametric data. A linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between baseline HbA1c levels and the change in HbA1c after 1 year of CGM use. Differences were considered significant at P < .05 set a priori. To guide future research, a posthoc power analysis was performed using Cohen’s d to estimate the required sample sizes for detecting significant effects, assuming a similar population.

Results

The study included 93 patients, with a mean (SD) age of 55 (13) years (range, 29-83 years). Of the participants, 56 were female (60%) and 37 were male (40%). All participants were identified as AI/AN and had non–insulin-dependent T2DM.

Primary Outcomes

A significant reduction in HbA1c levels was observed after 1 year of CGM use. The mean (SD) baseline HbA1c was 9.5% (2.4%), which decreased to 7.6% (2.2%) at 1-year follow-up (Table 1). This difference represents a mean change of -1.86% (2.4%) (95% CI, -2.35 to -1.37; P < .001 [paired t test, -7.53]).

A linear regression model evaluated the relationship between baseline HbA1c (predictor) and the change in HbA1c after 1 year (outcome). The change in HbA1c was calculated as the difference between 1-year follow-up and baseline values. The regression model revealed a significant negative association between baseline HbA1c and the change in HbA1c (Β = -0.576; P < .001), indicating that higher baseline HbA1c values were associated with greater reductions in HbA1c over the year. The regression equation was: Change in HbA1c = 3.587 – 0.576 × Baseline HbA1c

The regression coefficient for baseline HbA1c was -0.576 (standard error, 0.083; t = -6.931; P < .001), indicating that for each 1% increase in baseline HbA1c, the reduction of HbA1c after 1 year increased by approximately 0.576% (Figure 2). The model explained 34.6% of the variance in HbA1c change (R2 = .345; adjusted R2 = .338).

Secondary Outcomes

Systolic BP decreased by a mean (SD) -4.9 (17) mm Hg; 95% CI, -8.6 to -1.11; P = .01, paired t test). However, no significant change was observed for diastolic BP (P = .77, paired t test). Similarly, no significant changes were observed in weight, LDL-C concentrations, or eGFR after 1 year of CGM use. A posthoc power analysis indicated that the study was underpowered to detect smaller effect sizes in secondary outcomes. For example, sample size estimates indicated that detecting significant changes in weight and LDL-C concentrations would require sample sizes of 152 and 220 patients, respectively (Table 2).

Discussion

This study found a clinically significant reduction in HbA1c levels after 1 year among AI/AN patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM who used CGMs. The mean HbA1c decreased 1.9%, from 9.5% at baseline to 7.6% after 1 year. This reduction is not only statistically significant (P < .001), it is clinically meaningful—even a 1% decrease in HbA1c is associated with substantial reductions in the risk of microvascular complications.3 The magnitude of the HbA1c reduction observed suggests CGM use may be associated with improved glycemic control in this high-risk population. By achieving lower HbA1c levels, patients may experience improved long-term health outcomes and a reduced burden of DM-related complications.

Changes in oral DM medications during the study period may have contributed to the observed improvements in HbA1c levels. While the dataset lacked detailed information on types or dosages of oral hypoglycemic agents used, adjustments in medication regimens are common in DM management and could significantly affect glycemic control. The inability to account for these changes results in an inability to attribute the improvements in HbA1c solely to CGM use. Future studies should collect comprehensive medication data to better isolate the effects of CGM use from other treatment modifications.

Another factor that may have contributed to the improved glycemic control is the DM self-management education and training patients received as part of standard care. Patients met with diabetes educators at least once and learned how to use the CGM device and interpret the data for self-management decisions. This education may have enhanced patient engagement and empowerment, enabling them to make informed choices about diet, physical activity, and medication adherence. Studies have shown that DM self-management education can significantly improve glycemic control and patient outcomes.13 By combining the CGM technology with targeted education, patients may have been better equipped to manage their condition, contributing to the observed reduction in HbA1c levels. Future studies should consider synergistic effects of CGM use and DM education when evaluating interventions for glycemic control.

The significant reduction in HbA1c indicates CGM use is associated with improved glycemic control in non–insulin-dependent T2DM. The linear regression analysis suggests patients with poorer glycemic control at baseline experienced greater reductions in HbA1c over the course of 1 year. This finding aligns with previous studies that have shown greater HbA1c reductions in patients with higher initial levels when using CGMs. Yaron et al reported similar findings: higher baseline HbA1c levels predicted more substantial improvements with CGM use in patients with T2DM on insulin therapy.14

This study contributes to existing research by examining the association between CGM use and glycemic control in patients with non– insulin-dependent T2DM within an AI/AN population, a group that has been underreported in previous studies. Most prior research has focused on insulin-dependent patients or populations with different ethnic backgrounds.12 By focusing on patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM, this study highlights the broader applicability of CGMs beyond traditional use, showcasing their potential association with benefits in earlier stages of DM management. Targeting the AI/AN population addresses a critical knowledge gap, given the disproportionately high prevalence of T2DM and associated complications in this group. The findings of this study suggest integrating CGM technology into the standard care of AI/AN patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM may be associated with improved glycemic control and may help reduce health disparities.

The modest decrease in systolic BP observed in this study may indicate potential cardiovascular benefits associated with CGM use, possibly due to improved glycemic control and increased patient engagement in self-management. However, given the limited sample size and exclusion criteria, the study lacked sufficient power to detect significant associations between CGM use and other secondary outcomes such as BP, weight, LDL-C, and eGFR. Therefore, the significant finding with systolic BP should be interpreted with caution.

The lack of significant changes in secondary outcomes may be attributed to the study’s limited sample size and the relatively short duration for observing changes in these parameters. Larger studies are needed to assess the full impact of CGM on these variables. The required sample sizes for achieving adequate power in future studies were calculated, highlighting the utility of our study as a pilot, providing critical data for the design of larger, adequately powered studies.

Limitations

The retrospective design of this study limits causal inferences. Moreover, potential confounding variables were not controlled, such as changes in medication regimens (other than insulin use), dietary counseling, or physical activity. Additionally, we could not account for the type or number of oral DM medications prescribed to patients. The dataset included only information on insulin use, without detailed records of other antidiabetic medications. This limitation may have influenced the observed change in glycemic control, as variations in medication regimens could affect HbA1c levels.

Because this study lacked a comparator group, the effect of CGM use cannot be definitively isolated from other factors (eg, medication changes, dietary modifications, or physical activity). Moreover, CGM devices can be costly and are not universally covered by all insurance or IHS programs, potentially limiting widespread implementation. Policy-level restrictions and patient-specific barriers may also hinder feasibility in other settings.

The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Of the initial 302 patients, about 69% were excluded due to insulin use or incomplete laboratory data. A ± 4-month window was selected to balance data quality with real-world practices. Extending this window further (eg, ± 6 months) might have included more participants but risked diluting the 1-year endpoint consistency. The lack of statistical significance in secondary metrics may be due to insufficient power rather than the absence of an effect.

Exclusion of patients due to incomplete data may have introduced selection bias. However, patients were included in the overall analysis if they met the criteria for HbA1c and CGM use, even if they lacked data for secondary outcomes. Additionally, the laboratory’s upper reporting limit for HbA1c was 14%, with values above this reported as “> 14%.” For analysis, these were recorded as 14.1%, which may underestimate the true baseline HbA1c levels and impact of the assessment of change. This occurred for 4 of the 93 patients included.

All patients used the Freestyle Libre CGM, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other CGM brands or models. Differences in device features, accuracy, scanning frequency, and user experience may influence outcomes, and results might differ with other CGM technologies. The dataset did not include patients’ scanning frequency because this metric was not consistently included in the EHRs.

Conclusions

This study found that CGM use was significantly associated with improved glycemic control in patients with non–insulin-dependent T2DM within an AI/AN population, particularly among patients with higher baseline HbA1c levels. The findings suggest that CGMs may be a valuable tool for managing T2DM beyond insulin-dependent populations.

Additional research with larger sample sizes, control groups, and extended follow-up periods is recommended to explore long-term benefits and impacts on other health metrics. The sample size estimates derived from this study serve as a valuable resource for researchers designing future studies aimed at addressing these gaps. Future research that expands on our findings by including larger, more diverse cohorts, accounting for medication use, and exploring different CGM technologies will enhance understanding and contribute to more effective diabetes management strategies for varied populations.

- National diabetes statistics report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 15, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html

- Elsayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S19-S40. doi:10.2337/dc23-S002

- Fowler MJ. Microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2011;29:116-122. doi:10.2337/diaclin.29.3.116

- Pleus S, Freckmann G, Schauer S, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose as an integral part in the management of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13:829-846. doi:10.1007/s13300-022-01254-8

- Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Schikman CH, et al. Structured self-monitoring of blood glucose significantly reduces A1C levels in poorly controlled, noninsulin-treated type 2 diabetes: results from the Structured Testing Program study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:262-267. doi:10.2337/dc10-1732

- Tanaka N, Yabe D, Murotani K, et al. Mental distress and health-related quality of life among type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients using self-monitoring of blood glucose: a cross-sectional questionnaire study in Japan. J Diabetes Investig. 2018;9:1203-1211. doi:10.1111/jdi.12827

- Hortensius J, Kars MC, Wierenga WS, et al. Perspectives of patients with type 1 or insulin-treated type 2 diabetes on self-monitoring of blood glucose: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:167. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-167

- Didyuk O, Econom N, Guardia A, Livingston K, Klueh U. Continuous glucose monitoring devices: past, present, and future focus on the history and evolution of technological innovation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2021;15:676-683. doi:10.1177/1932296819899394

- Beck RW, Riddlesworth TD, Ruedy K, et al. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:371-378. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.19975

- Lind M, Polonsky W, Hirsch IB, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring vs conventional therapy for glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes treated with multiple daily insulin injections: the GOLD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:379-387. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.19976

- Bolinder J, Antuna R, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn P, et al. Novel glucose-sensing technology and hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes: a multicenter, non-masked, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2254-2263. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31535-5

- Seidu S, Kunutsor SK, Ajjan RA, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous glucose monitoring and intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional evidence. Diabetes Care. 2024;47:169-179. doi:10.2337/dc23-1520

- ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S68-S96. doi:10.2337/dc23-S005

- Yaron M, Roitman E, Aharon-Hananel G, et al. Effect of flash glucose monitoring technology on glycemic control and treatment satisfaction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1178-1184. doi:10.2337/dc18-0166

- National diabetes statistics report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 15, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html

- Elsayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S19-S40. doi:10.2337/dc23-S002

- Fowler MJ. Microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2011;29:116-122. doi:10.2337/diaclin.29.3.116

- Pleus S, Freckmann G, Schauer S, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose as an integral part in the management of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13:829-846. doi:10.1007/s13300-022-01254-8

- Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Schikman CH, et al. Structured self-monitoring of blood glucose significantly reduces A1C levels in poorly controlled, noninsulin-treated type 2 diabetes: results from the Structured Testing Program study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:262-267. doi:10.2337/dc10-1732

- Tanaka N, Yabe D, Murotani K, et al. Mental distress and health-related quality of life among type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients using self-monitoring of blood glucose: a cross-sectional questionnaire study in Japan. J Diabetes Investig. 2018;9:1203-1211. doi:10.1111/jdi.12827

- Hortensius J, Kars MC, Wierenga WS, et al. Perspectives of patients with type 1 or insulin-treated type 2 diabetes on self-monitoring of blood glucose: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:167. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-167

- Didyuk O, Econom N, Guardia A, Livingston K, Klueh U. Continuous glucose monitoring devices: past, present, and future focus on the history and evolution of technological innovation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2021;15:676-683. doi:10.1177/1932296819899394

- Beck RW, Riddlesworth TD, Ruedy K, et al. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:371-378. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.19975

- Lind M, Polonsky W, Hirsch IB, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring vs conventional therapy for glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes treated with multiple daily insulin injections: the GOLD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:379-387. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.19976

- Bolinder J, Antuna R, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn P, et al. Novel glucose-sensing technology and hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes: a multicenter, non-masked, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2254-2263. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31535-5

- Seidu S, Kunutsor SK, Ajjan RA, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous glucose monitoring and intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional evidence. Diabetes Care. 2024;47:169-179. doi:10.2337/dc23-1520

- ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S68-S96. doi:10.2337/dc23-S005

- Yaron M, Roitman E, Aharon-Hananel G, et al. Effect of flash glucose monitoring technology on glycemic control and treatment satisfaction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1178-1184. doi:10.2337/dc18-0166

Impact of Continuous Glucose Monitoring for American Indian/Alaska Native Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Not Using Insulin

Impact of Continuous Glucose Monitoring for American Indian/Alaska Native Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Not Using Insulin