User login

Impella heart pump may enable 30-minute reperfusion delay

CHICAGO – An investigative heart pump for unloading the left ventricle in patients who had an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) yielded similar safety and efficacy outcomes with a 30-minute delay in reperfusion or the standard approach of immediate reperfusion.

That’s according to results of a pilot feasibility trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

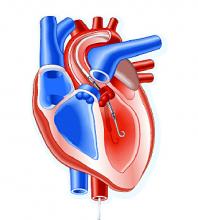

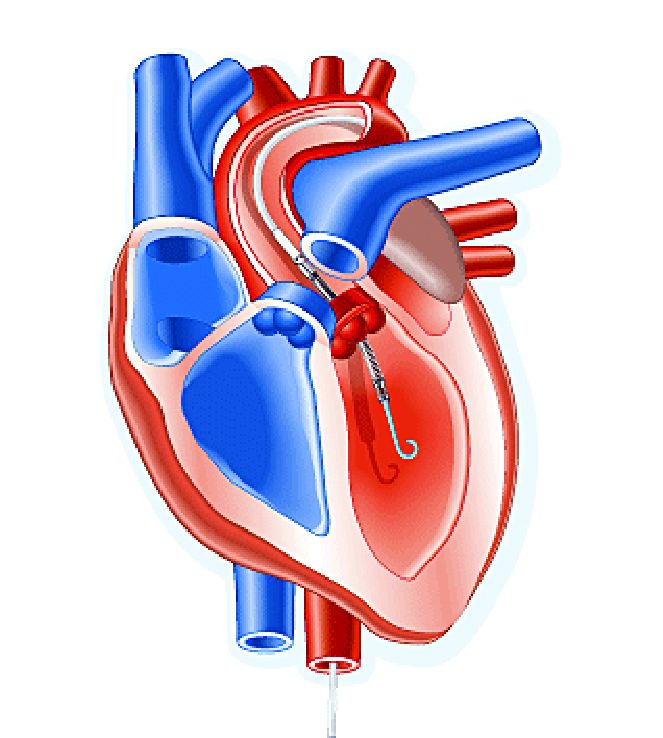

The trial, titled the DTU (Door to Unload)–STEMI trial, evaluated the Impella CP (Abiomed) device used for unloading the left ventricle (LV). “No prohibitive safety signals that would preclude proceeding to a larger pivotal study of left ventricle unloading and delaying reperfusion for 30 minutes were identified,” said principal investigator Navin Kapur, MD, of Tufts Medical Center.

The trial evaluated 50 patients who received the Impella device in two different groups: one that underwent immediate reperfusion after LV unloading, the other that had a 30-minute delay before reperfusion. The study found no significant difference in major adverse cardiovascular or cerebral events between the two groups (there were two in the delayed group vs. none in the immediate group), and no difference in infarct size increase as a percentage of LV mass at 30 days between the groups, Dr. Kapur said.

Door-to-balloon times averaged 73 minutes in the immediate reperfusion group and 97 minutes in the delayed reperfusion group, with door-to-unload times averaging around 60 minutes in both groups. “We were able to see successful enrollment and distribution across multiple sites and multiple operators, suggesting the feasibility of this approach,” Dr. Kapur said.

He noted “one of the most important messages” of the study was that no patients in either arm required percutaneous coronary intervention. “What this suggests is that, when we look at operator behavior, operators were comfortable with initiating LV unloading and waiting 30 minutes,” Dr. Kapur said.

The primary endpoint of the trial was to determine if delayed reperfusion led to an increase in infarct size. “We did not see that,” he noted. “And among patients with an anterior ST-segment elevation sum in leads V1-V4 of more than 6 mm Hg, infarct size normalized to the area at risk was significantly lower with 30 minutes of LV unloading before reperfusion, compared to LV unloading with immediate reperfusion.”

The next step is to initiate a pivotal trial of the device, Dr. Kapur said. “The findings from the DTU-STEMI pilot trial will inform the pivotal trial based on preclinical data showing that LV unloading attenuates myocardial ischemia and also preconditions the myocardium to allow it to be more receptive to reperfusion with a reduction in reperfusion injury,” he said. The pivotal trial will have two similar arms: one using the standard of care of immediate reperfusion and the other utilizing the 30-minute delay.

In his discussion of the DTU-STEMI trial, Holger Thiele, MD, of the Leipzig (Germany) Heart Institute and the University of Leipzig, expressed concern with the lack of a standard-of-care group in the trial. “Thus, the primary efficacy endpoint on infarct size cannot be reliably compared,” he said. “Based on the small sample size, there’s no reliable information on safety.”

Dr. Kapur reported financial relationships with Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Abbott, Medtronic, and MD Start. Dr. Thiele had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Kapur NK et al. AHA scientific sessions, LBCT-19578

CHICAGO – An investigative heart pump for unloading the left ventricle in patients who had an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) yielded similar safety and efficacy outcomes with a 30-minute delay in reperfusion or the standard approach of immediate reperfusion.

That’s according to results of a pilot feasibility trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The trial, titled the DTU (Door to Unload)–STEMI trial, evaluated the Impella CP (Abiomed) device used for unloading the left ventricle (LV). “No prohibitive safety signals that would preclude proceeding to a larger pivotal study of left ventricle unloading and delaying reperfusion for 30 minutes were identified,” said principal investigator Navin Kapur, MD, of Tufts Medical Center.

The trial evaluated 50 patients who received the Impella device in two different groups: one that underwent immediate reperfusion after LV unloading, the other that had a 30-minute delay before reperfusion. The study found no significant difference in major adverse cardiovascular or cerebral events between the two groups (there were two in the delayed group vs. none in the immediate group), and no difference in infarct size increase as a percentage of LV mass at 30 days between the groups, Dr. Kapur said.

Door-to-balloon times averaged 73 minutes in the immediate reperfusion group and 97 minutes in the delayed reperfusion group, with door-to-unload times averaging around 60 minutes in both groups. “We were able to see successful enrollment and distribution across multiple sites and multiple operators, suggesting the feasibility of this approach,” Dr. Kapur said.

He noted “one of the most important messages” of the study was that no patients in either arm required percutaneous coronary intervention. “What this suggests is that, when we look at operator behavior, operators were comfortable with initiating LV unloading and waiting 30 minutes,” Dr. Kapur said.

The primary endpoint of the trial was to determine if delayed reperfusion led to an increase in infarct size. “We did not see that,” he noted. “And among patients with an anterior ST-segment elevation sum in leads V1-V4 of more than 6 mm Hg, infarct size normalized to the area at risk was significantly lower with 30 minutes of LV unloading before reperfusion, compared to LV unloading with immediate reperfusion.”

The next step is to initiate a pivotal trial of the device, Dr. Kapur said. “The findings from the DTU-STEMI pilot trial will inform the pivotal trial based on preclinical data showing that LV unloading attenuates myocardial ischemia and also preconditions the myocardium to allow it to be more receptive to reperfusion with a reduction in reperfusion injury,” he said. The pivotal trial will have two similar arms: one using the standard of care of immediate reperfusion and the other utilizing the 30-minute delay.

In his discussion of the DTU-STEMI trial, Holger Thiele, MD, of the Leipzig (Germany) Heart Institute and the University of Leipzig, expressed concern with the lack of a standard-of-care group in the trial. “Thus, the primary efficacy endpoint on infarct size cannot be reliably compared,” he said. “Based on the small sample size, there’s no reliable information on safety.”

Dr. Kapur reported financial relationships with Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Abbott, Medtronic, and MD Start. Dr. Thiele had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Kapur NK et al. AHA scientific sessions, LBCT-19578

CHICAGO – An investigative heart pump for unloading the left ventricle in patients who had an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) yielded similar safety and efficacy outcomes with a 30-minute delay in reperfusion or the standard approach of immediate reperfusion.

That’s according to results of a pilot feasibility trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The trial, titled the DTU (Door to Unload)–STEMI trial, evaluated the Impella CP (Abiomed) device used for unloading the left ventricle (LV). “No prohibitive safety signals that would preclude proceeding to a larger pivotal study of left ventricle unloading and delaying reperfusion for 30 minutes were identified,” said principal investigator Navin Kapur, MD, of Tufts Medical Center.

The trial evaluated 50 patients who received the Impella device in two different groups: one that underwent immediate reperfusion after LV unloading, the other that had a 30-minute delay before reperfusion. The study found no significant difference in major adverse cardiovascular or cerebral events between the two groups (there were two in the delayed group vs. none in the immediate group), and no difference in infarct size increase as a percentage of LV mass at 30 days between the groups, Dr. Kapur said.

Door-to-balloon times averaged 73 minutes in the immediate reperfusion group and 97 minutes in the delayed reperfusion group, with door-to-unload times averaging around 60 minutes in both groups. “We were able to see successful enrollment and distribution across multiple sites and multiple operators, suggesting the feasibility of this approach,” Dr. Kapur said.

He noted “one of the most important messages” of the study was that no patients in either arm required percutaneous coronary intervention. “What this suggests is that, when we look at operator behavior, operators were comfortable with initiating LV unloading and waiting 30 minutes,” Dr. Kapur said.

The primary endpoint of the trial was to determine if delayed reperfusion led to an increase in infarct size. “We did not see that,” he noted. “And among patients with an anterior ST-segment elevation sum in leads V1-V4 of more than 6 mm Hg, infarct size normalized to the area at risk was significantly lower with 30 minutes of LV unloading before reperfusion, compared to LV unloading with immediate reperfusion.”

The next step is to initiate a pivotal trial of the device, Dr. Kapur said. “The findings from the DTU-STEMI pilot trial will inform the pivotal trial based on preclinical data showing that LV unloading attenuates myocardial ischemia and also preconditions the myocardium to allow it to be more receptive to reperfusion with a reduction in reperfusion injury,” he said. The pivotal trial will have two similar arms: one using the standard of care of immediate reperfusion and the other utilizing the 30-minute delay.

In his discussion of the DTU-STEMI trial, Holger Thiele, MD, of the Leipzig (Germany) Heart Institute and the University of Leipzig, expressed concern with the lack of a standard-of-care group in the trial. “Thus, the primary efficacy endpoint on infarct size cannot be reliably compared,” he said. “Based on the small sample size, there’s no reliable information on safety.”

Dr. Kapur reported financial relationships with Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Abbott, Medtronic, and MD Start. Dr. Thiele had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Kapur NK et al. AHA scientific sessions, LBCT-19578

REPORTING FROM AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Door-to-balloon times averaged 73 minutes in the immediate reperfusion group and 97 minutes in the delayed reperfusion group.

Study details: A phase 1, randomized, exploratory safety and feasibility trial in 50 patients with anterior STEMI to left ventricle unloading using the Impella CP followed by immediate reperfusion versus delayed reperfusion after 30 minutes of unloading.

Disclosures: Dr. Kapur reported financial relationships with Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Abbott, Medtronic and MD Start/Precardia.

Source: Kapur NK et al. AHA scientific sessions, LBCT-19578.

Is prehospital cooling in cardiac arrest ready for prime time?

CHICAGO – Starting transnasal evaporative cooling before patients in cardiac arrest arrive at the hospital has been found to be safe, according to study results presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The European trial didn’t determine any benefit in the out-of-hospital approach, compared with in-hospital cooling across all study patients. But it did suggest that patients with ventricular fibrillation may achieve higher rates of complete neurologic recovery with the prehospital cooling approach.

“Transnasal evaporative cooling in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is hemodynamically safe,” said Per Nordberg, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, reporting for the Prehospital Resuscitation Intra-arrest Cooling Effectiveness Survival Study (PRINCESS). “I think this an important message, because guidelines state at the moment that you shouldn’t cool patients outside the hospital. We have shown that this is possible with this new method.”

Transnasal evaporative cooling (RhinoChill) is a noninvasive method that involves cooling of the brain and provides continuous cooling without volume loading.

Centers in seven European countries participated in the trial, randomizing 677 patients to the transnasal, early cooling protocol or standard in-hospital hypothermia. The final analysis evaluated 671 patients: 337 in the intervention group and 334 in the control group. In the intervention group, the transnasal cooling technique was started on patients during CPR in their homes or in the ambulance.

The study found that the rate of 90-day survival with good neurological outcome was 16.6% in the intervention group, compared with 13.5% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .26).

“However, we could see a signal or a clinical trend toward an improved neurologic outcome in patients with ventricular fibrillation,” Dr. Nordberg said: 34.8% vs. 25.9% for the intervention vs. control populations, a relative, nonsignificant difference of 25% (P = .11).

In terms of complete neurologic recovery, the differences between the treatment groups among those with ventricular fibrillation were even more profound, and significant: 32.6% vs. 20% (P = .002).

Rates of cardiovascular complications – ventricular fibrillation, cardiogenic shock, pulmonary edema, and need for vasopressor – were similar between both groups, although the intervention group had low rates of nasal-related problems such as nose bleed and white nose tip that the control group didn’t have.

Transnasal evaporative cooling “could significantly shorten the time to the target temperature; we have shown that in previous safety feasibility trials,” Dr. Nordberg said. “Now, we can confirm that this method is effective to cool patients with cardiac arrest outside the hospital.”

In his discussion of the trial, Christopher B. Granger, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., noted that the trial was well conducted and that it confirmed that patients can be rapidly cooled during or immediately after cardiac arrest. “But we still do not know if this has meaningful improvement in clinical outcomes,” he cautioned. A strength of the trial is its size, particularly “in a very challenging setting,” Dr. Granger added.

But he questioned the potential for neurological benefit in patients with ventricular fibrillation, particularly because the finding conflicts with a previously published trial (Crit Care Med. 2009 Dec;37[12]:3062-9). “With the primary outcome not significantly reduced, the subgroup analysis may not be reliable,” he said.

What’s needed next? “This trial provides some suggestion of the benefit of early rapid cooling in the ventricular fibrillation population,” Dr. Granger said, “but another trial is needed to justify a widespread change in practice.”

He reported receiving funding from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation. The makers of RhinoChill provided the cooling device used in the study at no cost to the participating sites.

Dr. Granger reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Armetheon, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic and the Medtronic Foundation, Merck, National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Rho Pharmaceuticals, Sirtex, and Verseon.

SOURCE: Nordberg P et al. Abstract 2018-LBCT-18598-AHA.

CHICAGO – Starting transnasal evaporative cooling before patients in cardiac arrest arrive at the hospital has been found to be safe, according to study results presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The European trial didn’t determine any benefit in the out-of-hospital approach, compared with in-hospital cooling across all study patients. But it did suggest that patients with ventricular fibrillation may achieve higher rates of complete neurologic recovery with the prehospital cooling approach.

“Transnasal evaporative cooling in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is hemodynamically safe,” said Per Nordberg, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, reporting for the Prehospital Resuscitation Intra-arrest Cooling Effectiveness Survival Study (PRINCESS). “I think this an important message, because guidelines state at the moment that you shouldn’t cool patients outside the hospital. We have shown that this is possible with this new method.”

Transnasal evaporative cooling (RhinoChill) is a noninvasive method that involves cooling of the brain and provides continuous cooling without volume loading.

Centers in seven European countries participated in the trial, randomizing 677 patients to the transnasal, early cooling protocol or standard in-hospital hypothermia. The final analysis evaluated 671 patients: 337 in the intervention group and 334 in the control group. In the intervention group, the transnasal cooling technique was started on patients during CPR in their homes or in the ambulance.

The study found that the rate of 90-day survival with good neurological outcome was 16.6% in the intervention group, compared with 13.5% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .26).

“However, we could see a signal or a clinical trend toward an improved neurologic outcome in patients with ventricular fibrillation,” Dr. Nordberg said: 34.8% vs. 25.9% for the intervention vs. control populations, a relative, nonsignificant difference of 25% (P = .11).

In terms of complete neurologic recovery, the differences between the treatment groups among those with ventricular fibrillation were even more profound, and significant: 32.6% vs. 20% (P = .002).

Rates of cardiovascular complications – ventricular fibrillation, cardiogenic shock, pulmonary edema, and need for vasopressor – were similar between both groups, although the intervention group had low rates of nasal-related problems such as nose bleed and white nose tip that the control group didn’t have.

Transnasal evaporative cooling “could significantly shorten the time to the target temperature; we have shown that in previous safety feasibility trials,” Dr. Nordberg said. “Now, we can confirm that this method is effective to cool patients with cardiac arrest outside the hospital.”

In his discussion of the trial, Christopher B. Granger, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., noted that the trial was well conducted and that it confirmed that patients can be rapidly cooled during or immediately after cardiac arrest. “But we still do not know if this has meaningful improvement in clinical outcomes,” he cautioned. A strength of the trial is its size, particularly “in a very challenging setting,” Dr. Granger added.

But he questioned the potential for neurological benefit in patients with ventricular fibrillation, particularly because the finding conflicts with a previously published trial (Crit Care Med. 2009 Dec;37[12]:3062-9). “With the primary outcome not significantly reduced, the subgroup analysis may not be reliable,” he said.

What’s needed next? “This trial provides some suggestion of the benefit of early rapid cooling in the ventricular fibrillation population,” Dr. Granger said, “but another trial is needed to justify a widespread change in practice.”

He reported receiving funding from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation. The makers of RhinoChill provided the cooling device used in the study at no cost to the participating sites.

Dr. Granger reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Armetheon, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic and the Medtronic Foundation, Merck, National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Rho Pharmaceuticals, Sirtex, and Verseon.

SOURCE: Nordberg P et al. Abstract 2018-LBCT-18598-AHA.

CHICAGO – Starting transnasal evaporative cooling before patients in cardiac arrest arrive at the hospital has been found to be safe, according to study results presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The European trial didn’t determine any benefit in the out-of-hospital approach, compared with in-hospital cooling across all study patients. But it did suggest that patients with ventricular fibrillation may achieve higher rates of complete neurologic recovery with the prehospital cooling approach.

“Transnasal evaporative cooling in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is hemodynamically safe,” said Per Nordberg, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, reporting for the Prehospital Resuscitation Intra-arrest Cooling Effectiveness Survival Study (PRINCESS). “I think this an important message, because guidelines state at the moment that you shouldn’t cool patients outside the hospital. We have shown that this is possible with this new method.”

Transnasal evaporative cooling (RhinoChill) is a noninvasive method that involves cooling of the brain and provides continuous cooling without volume loading.

Centers in seven European countries participated in the trial, randomizing 677 patients to the transnasal, early cooling protocol or standard in-hospital hypothermia. The final analysis evaluated 671 patients: 337 in the intervention group and 334 in the control group. In the intervention group, the transnasal cooling technique was started on patients during CPR in their homes or in the ambulance.

The study found that the rate of 90-day survival with good neurological outcome was 16.6% in the intervention group, compared with 13.5% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .26).

“However, we could see a signal or a clinical trend toward an improved neurologic outcome in patients with ventricular fibrillation,” Dr. Nordberg said: 34.8% vs. 25.9% for the intervention vs. control populations, a relative, nonsignificant difference of 25% (P = .11).

In terms of complete neurologic recovery, the differences between the treatment groups among those with ventricular fibrillation were even more profound, and significant: 32.6% vs. 20% (P = .002).

Rates of cardiovascular complications – ventricular fibrillation, cardiogenic shock, pulmonary edema, and need for vasopressor – were similar between both groups, although the intervention group had low rates of nasal-related problems such as nose bleed and white nose tip that the control group didn’t have.

Transnasal evaporative cooling “could significantly shorten the time to the target temperature; we have shown that in previous safety feasibility trials,” Dr. Nordberg said. “Now, we can confirm that this method is effective to cool patients with cardiac arrest outside the hospital.”

In his discussion of the trial, Christopher B. Granger, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., noted that the trial was well conducted and that it confirmed that patients can be rapidly cooled during or immediately after cardiac arrest. “But we still do not know if this has meaningful improvement in clinical outcomes,” he cautioned. A strength of the trial is its size, particularly “in a very challenging setting,” Dr. Granger added.

But he questioned the potential for neurological benefit in patients with ventricular fibrillation, particularly because the finding conflicts with a previously published trial (Crit Care Med. 2009 Dec;37[12]:3062-9). “With the primary outcome not significantly reduced, the subgroup analysis may not be reliable,” he said.

What’s needed next? “This trial provides some suggestion of the benefit of early rapid cooling in the ventricular fibrillation population,” Dr. Granger said, “but another trial is needed to justify a widespread change in practice.”

He reported receiving funding from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation. The makers of RhinoChill provided the cooling device used in the study at no cost to the participating sites.

Dr. Granger reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Armetheon, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic and the Medtronic Foundation, Merck, National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Rho Pharmaceuticals, Sirtex, and Verseon.

SOURCE: Nordberg P et al. Abstract 2018-LBCT-18598-AHA.

REPORTING FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Prehospital hypothermia therapy for cardiac arrest patients is safe.

Major finding: Ninety-day survival was 16.6% in the intervention group vs. 13.5% in controls (P = .26).

Study details: A randomized clinical trial of 677 patients who had cardiac arrest outside the hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Nordberg receives funding from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation. The makers of RhinoChill provided the cooling device used in the study at no cost to the participating sites.

Source: Nordberg P et al. Abstract 2018-LBCT-18598-AHA.

REDUCE-IT: Fish-derived agent cut CV events 25%

CHICAGO – Detailed results of the REDUCE-IT trial have confirmed earlier-reported top line results that showed a 25% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular death or nonfatal cardiovascular event with the fish-derived, triglyceride-reducing agent icosapent acid in combination with statin.

But they should not be interpreted as validation of the cardiovascular benefits of fish-oil supplements, according to Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, principal investigator and steering committee chair for REDUCE-IT, who presented the results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He reported the results from 8,179 patients followed for a median of 4.9 years. The treatment group received 4 g/day of icosapent ethyl (Vascepa, Amarin), a single-molecule agent consisting of the omega-3 acid known as eicosapentaeonoic acid (EPA) in ethyl-ester form, which Dr. Bhatt called “a highly purified” formulation. Vascepa is derived from fish but it is not fish oil, a company press release states. Amarin, sponsor of the study, released top line results in September.

To qualify for the trial, patients had to have a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease or diabetes and other risk factors, had been on statin therapy and had above normal triglyceride (135-499 mg/dL) and optimal LDL (41-100 mg/dL) levels. Patients were randomly assigned to receive 4 g/day of icosapent ethyl or placebo.

Dr. Bhatt stressed that the REDUCE-IT results do not necessarily validate the use of fish oil to lower cardiovascular risk. “It would be mistake if patients and physicians” to interpret the results that way, and that classifying the purified formulation of icosapent ethyl used in REDUCE-IT as fish oil is a “misnomer.” He added, “Really, what we’re talking about is prescription therapy icosapent ethyl vs. over-the-counter supplements.” Icosapent ethyl is approved in the United States for patients with triglyceride levels of more than 500 mg/dL.

Dr. Bhatt and the study coauthors acknowledged that the results of REDUCE-IT deviate from other trials of triglyceride-lowering agents, including other n-3 fatty acids. They noted two potential explanations: a high dose; or higher ratios of EPA to docosahexaenoic acid in the REDUCE-IT formulation vs. agents used in the other studies. For example, the ASCEND study, presented at the European Society of Cardiology in September, reported no cardiovascular benefit from a 1-g/day dose of omega-3 fatty acids and low-dose aspirin in patients with diabetes.

The primary endpoint of REDUCE-IT was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI or stroke, coronary revascularization or unstable angina, which occurred in 17.2% of the patients taking icosapent ethyl, compared with 22% of the controls, for a risk reduction of 25% (P less than .001). The key secondary endpoint was composite of cardiovascular death and nonfatal MI or stroke, which occurred in 11.2% and 14.8% of the treated and placebo groups, respectively, for a risk reduction of 26% (P less than .001).

The study investigators also zeroed in on specific ischemic endpoints. Cardiovascular death rates were 20% lower in the treated patients (4.2% vs. 5.2%, P less than .03).

The study also evaluated lipid levels. The median change in triglyceride levels after a year of treatment was a decrease of 18.3%, or 39 mg/dL, in the treatment group while triglyceride levels rose 2.2% in the placebo patients (P less than .001). LDL levels increased in the treated patients by 3.1%, or 2 mg/dL (median) vs. 10.2%, or 7 mg/dL, in controls (P less than .001).

The trial also reported a 33% greater risk of hospitalization for atrial fibrillation or flutter and about a 30% heightened risk of serious bleeding among patients taking icosapent ethyl. Dr. Bhatt pointed out that, while the high rate of atrial fibrillation among treated patients was statistically significant, “the most feared complication of atrial fibrillation is stroke, but in this study we saw a 28% reduction in stroke.”

Likewise the nonsignificantly higher rate of bleeding in the treatment group was inconsequential. “When we looked at specific types of serious bleeding – GI or stomach bleeding, CNS or bleeding into the brain or fatal bleeding – there were no significant differences,” he said.

Discussant Carl Orringer, MD, of the University of Miami, said, “My perspective of this is that the likelihood of atrial fibrillation, although statistically higher, is something that should not prevent physicians from prescribing the drug because of the tremendous benefit that we’ve seen in those appropriate patients on high intensity statin.” However, he said, it does merit further investigation. He also pointed out that one limitation of the study was that the population was 90% white. “Thus the potential benefits of icosapent ethyl in patients of other ethnicities remains unclear,” he said.

The results were published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Bhatt receives funding from Amarin, which sponsored the REDUCE-IT trial.

SOURCE: Bhatt DL, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 10; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa181279.

CHICAGO – Detailed results of the REDUCE-IT trial have confirmed earlier-reported top line results that showed a 25% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular death or nonfatal cardiovascular event with the fish-derived, triglyceride-reducing agent icosapent acid in combination with statin.

But they should not be interpreted as validation of the cardiovascular benefits of fish-oil supplements, according to Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, principal investigator and steering committee chair for REDUCE-IT, who presented the results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He reported the results from 8,179 patients followed for a median of 4.9 years. The treatment group received 4 g/day of icosapent ethyl (Vascepa, Amarin), a single-molecule agent consisting of the omega-3 acid known as eicosapentaeonoic acid (EPA) in ethyl-ester form, which Dr. Bhatt called “a highly purified” formulation. Vascepa is derived from fish but it is not fish oil, a company press release states. Amarin, sponsor of the study, released top line results in September.

To qualify for the trial, patients had to have a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease or diabetes and other risk factors, had been on statin therapy and had above normal triglyceride (135-499 mg/dL) and optimal LDL (41-100 mg/dL) levels. Patients were randomly assigned to receive 4 g/day of icosapent ethyl or placebo.

Dr. Bhatt stressed that the REDUCE-IT results do not necessarily validate the use of fish oil to lower cardiovascular risk. “It would be mistake if patients and physicians” to interpret the results that way, and that classifying the purified formulation of icosapent ethyl used in REDUCE-IT as fish oil is a “misnomer.” He added, “Really, what we’re talking about is prescription therapy icosapent ethyl vs. over-the-counter supplements.” Icosapent ethyl is approved in the United States for patients with triglyceride levels of more than 500 mg/dL.

Dr. Bhatt and the study coauthors acknowledged that the results of REDUCE-IT deviate from other trials of triglyceride-lowering agents, including other n-3 fatty acids. They noted two potential explanations: a high dose; or higher ratios of EPA to docosahexaenoic acid in the REDUCE-IT formulation vs. agents used in the other studies. For example, the ASCEND study, presented at the European Society of Cardiology in September, reported no cardiovascular benefit from a 1-g/day dose of omega-3 fatty acids and low-dose aspirin in patients with diabetes.

The primary endpoint of REDUCE-IT was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI or stroke, coronary revascularization or unstable angina, which occurred in 17.2% of the patients taking icosapent ethyl, compared with 22% of the controls, for a risk reduction of 25% (P less than .001). The key secondary endpoint was composite of cardiovascular death and nonfatal MI or stroke, which occurred in 11.2% and 14.8% of the treated and placebo groups, respectively, for a risk reduction of 26% (P less than .001).

The study investigators also zeroed in on specific ischemic endpoints. Cardiovascular death rates were 20% lower in the treated patients (4.2% vs. 5.2%, P less than .03).

The study also evaluated lipid levels. The median change in triglyceride levels after a year of treatment was a decrease of 18.3%, or 39 mg/dL, in the treatment group while triglyceride levels rose 2.2% in the placebo patients (P less than .001). LDL levels increased in the treated patients by 3.1%, or 2 mg/dL (median) vs. 10.2%, or 7 mg/dL, in controls (P less than .001).

The trial also reported a 33% greater risk of hospitalization for atrial fibrillation or flutter and about a 30% heightened risk of serious bleeding among patients taking icosapent ethyl. Dr. Bhatt pointed out that, while the high rate of atrial fibrillation among treated patients was statistically significant, “the most feared complication of atrial fibrillation is stroke, but in this study we saw a 28% reduction in stroke.”

Likewise the nonsignificantly higher rate of bleeding in the treatment group was inconsequential. “When we looked at specific types of serious bleeding – GI or stomach bleeding, CNS or bleeding into the brain or fatal bleeding – there were no significant differences,” he said.

Discussant Carl Orringer, MD, of the University of Miami, said, “My perspective of this is that the likelihood of atrial fibrillation, although statistically higher, is something that should not prevent physicians from prescribing the drug because of the tremendous benefit that we’ve seen in those appropriate patients on high intensity statin.” However, he said, it does merit further investigation. He also pointed out that one limitation of the study was that the population was 90% white. “Thus the potential benefits of icosapent ethyl in patients of other ethnicities remains unclear,” he said.

The results were published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Bhatt receives funding from Amarin, which sponsored the REDUCE-IT trial.

SOURCE: Bhatt DL, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 10; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa181279.

CHICAGO – Detailed results of the REDUCE-IT trial have confirmed earlier-reported top line results that showed a 25% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular death or nonfatal cardiovascular event with the fish-derived, triglyceride-reducing agent icosapent acid in combination with statin.

But they should not be interpreted as validation of the cardiovascular benefits of fish-oil supplements, according to Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, principal investigator and steering committee chair for REDUCE-IT, who presented the results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He reported the results from 8,179 patients followed for a median of 4.9 years. The treatment group received 4 g/day of icosapent ethyl (Vascepa, Amarin), a single-molecule agent consisting of the omega-3 acid known as eicosapentaeonoic acid (EPA) in ethyl-ester form, which Dr. Bhatt called “a highly purified” formulation. Vascepa is derived from fish but it is not fish oil, a company press release states. Amarin, sponsor of the study, released top line results in September.

To qualify for the trial, patients had to have a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease or diabetes and other risk factors, had been on statin therapy and had above normal triglyceride (135-499 mg/dL) and optimal LDL (41-100 mg/dL) levels. Patients were randomly assigned to receive 4 g/day of icosapent ethyl or placebo.

Dr. Bhatt stressed that the REDUCE-IT results do not necessarily validate the use of fish oil to lower cardiovascular risk. “It would be mistake if patients and physicians” to interpret the results that way, and that classifying the purified formulation of icosapent ethyl used in REDUCE-IT as fish oil is a “misnomer.” He added, “Really, what we’re talking about is prescription therapy icosapent ethyl vs. over-the-counter supplements.” Icosapent ethyl is approved in the United States for patients with triglyceride levels of more than 500 mg/dL.

Dr. Bhatt and the study coauthors acknowledged that the results of REDUCE-IT deviate from other trials of triglyceride-lowering agents, including other n-3 fatty acids. They noted two potential explanations: a high dose; or higher ratios of EPA to docosahexaenoic acid in the REDUCE-IT formulation vs. agents used in the other studies. For example, the ASCEND study, presented at the European Society of Cardiology in September, reported no cardiovascular benefit from a 1-g/day dose of omega-3 fatty acids and low-dose aspirin in patients with diabetes.

The primary endpoint of REDUCE-IT was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI or stroke, coronary revascularization or unstable angina, which occurred in 17.2% of the patients taking icosapent ethyl, compared with 22% of the controls, for a risk reduction of 25% (P less than .001). The key secondary endpoint was composite of cardiovascular death and nonfatal MI or stroke, which occurred in 11.2% and 14.8% of the treated and placebo groups, respectively, for a risk reduction of 26% (P less than .001).

The study investigators also zeroed in on specific ischemic endpoints. Cardiovascular death rates were 20% lower in the treated patients (4.2% vs. 5.2%, P less than .03).

The study also evaluated lipid levels. The median change in triglyceride levels after a year of treatment was a decrease of 18.3%, or 39 mg/dL, in the treatment group while triglyceride levels rose 2.2% in the placebo patients (P less than .001). LDL levels increased in the treated patients by 3.1%, or 2 mg/dL (median) vs. 10.2%, or 7 mg/dL, in controls (P less than .001).

The trial also reported a 33% greater risk of hospitalization for atrial fibrillation or flutter and about a 30% heightened risk of serious bleeding among patients taking icosapent ethyl. Dr. Bhatt pointed out that, while the high rate of atrial fibrillation among treated patients was statistically significant, “the most feared complication of atrial fibrillation is stroke, but in this study we saw a 28% reduction in stroke.”

Likewise the nonsignificantly higher rate of bleeding in the treatment group was inconsequential. “When we looked at specific types of serious bleeding – GI or stomach bleeding, CNS or bleeding into the brain or fatal bleeding – there were no significant differences,” he said.

Discussant Carl Orringer, MD, of the University of Miami, said, “My perspective of this is that the likelihood of atrial fibrillation, although statistically higher, is something that should not prevent physicians from prescribing the drug because of the tremendous benefit that we’ve seen in those appropriate patients on high intensity statin.” However, he said, it does merit further investigation. He also pointed out that one limitation of the study was that the population was 90% white. “Thus the potential benefits of icosapent ethyl in patients of other ethnicities remains unclear,” he said.

The results were published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Bhatt receives funding from Amarin, which sponsored the REDUCE-IT trial.

SOURCE: Bhatt DL, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 10; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa181279.

REPORTING FROM AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS 2018

Key Clinical point: .

Major finding: Cardiovascular death or nonfatal cardiovascular event occurred in 17.7% of treated patients vs. 22% of controls.

Study details: Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of 8,179 patients with established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and other risk factors.

Disclosures: Dr. Bhatt disclosed having a significant research relationship with Amarin Corp., which funded the trial.

Source: N Engl J Med. 2018; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa181279.

Quality tool tied to improved adherence

CHICAGO – A multifaceted quality initiative that consists of staff education, patient reminders and a feedback loop may help to improve therapy adherence and encourage lifestyle changes of at-risk cardiovascular patients in settings with limited resources, according to results of a clinical trial from Brazil presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions 2018.

“In patients at high cardiovascular risk – in this case patients with established cardiovascular disease – a multifaceted quality-improvement intervention resulted in significant improvement in the use of evidence-based therapies,” said Otavio Berwanger, MD, PhD, of the Heart Hospital in Sao Paolo. He reported results of the BRIDGE Cardiovascular Prevention Cluster Randomized Trial. “The tools used in our trial can become the basis for developing quality-improvement programs to maximize the use of evidence-based therapies for the management of these high-risk patients with, especially in limited-resource settings.”

BRIDGE-CV included 1,619 patients from 40 care settings. Institutions that adopted the multifaceted intervention adhered to 73.5% of the evidence-based therapies (antiplatelet agents, statins and ACE inhibitors) while those in the control group adhered to 58.7% of the performance measures, Dr. Berwanger said. That represents a gain of 25%. The study employed an “all-or-none” model. That is, participating sites were required to adopt all components of the quality-improvement initiative or none.

He noted that although the evidence supporting the use of platelet therapies, statins, and ACE inhibitors is strong, “translation of these findings in practice is clearly suboptimal.” He added, “It seems to be an even larger problem in settings like mine in Brazil, so quality-improvement interventions, especially in lower-resource settings such as low- and middle-income countries, are definitely needed.”

The quality-improvement model the trial evaluated involved two levels of intervention. The first level comprised three steps: a case manager evaluating the patient’s treatment needs with the aid of a checklist; then an evaluation by the physician; and then providing physicians with what Dr. Berwanger described as “a physician support tool” – a one-page summary of major guideline recommendations. The second level comprised monthly audit and feedback reports to the providers and patient education about lifestyle modification. Staff education and training was also provided to sites that adopted the model. “Our intervention was sort of based on behavioral marketing,” Dr. Berwanger said.

The trial also identified a number of trends among secondary endpoints, although the populations were too small to reach statistical significance. For example, Dr. Berwanger noted that intervention sites had higher use of high-dose statins and more than double the rate of smoking cessation. He also noted a 24% relative risk reduction in major cardiovascular events in the intervention group vs. controls. Among the intervention sites, teaching institutions seems to have a notable improvement in adherence outcomes than other settings, Dr. Berwanger said, but the study did not fully analyze that trend.

“We see this study not as the final word but as the first step,” he said. “More studies are needed.”

Dr. Berwanger reported receiving research support and/or honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Amgen, Bayer, Eurofarma, Servier, Novartis and NovoNordisk. Amgen sponsored the investigator-initiated trial.

SOURCE: Berwanger O, et al. AHA 2018 Abstr.19360.

CHICAGO – A multifaceted quality initiative that consists of staff education, patient reminders and a feedback loop may help to improve therapy adherence and encourage lifestyle changes of at-risk cardiovascular patients in settings with limited resources, according to results of a clinical trial from Brazil presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions 2018.

“In patients at high cardiovascular risk – in this case patients with established cardiovascular disease – a multifaceted quality-improvement intervention resulted in significant improvement in the use of evidence-based therapies,” said Otavio Berwanger, MD, PhD, of the Heart Hospital in Sao Paolo. He reported results of the BRIDGE Cardiovascular Prevention Cluster Randomized Trial. “The tools used in our trial can become the basis for developing quality-improvement programs to maximize the use of evidence-based therapies for the management of these high-risk patients with, especially in limited-resource settings.”

BRIDGE-CV included 1,619 patients from 40 care settings. Institutions that adopted the multifaceted intervention adhered to 73.5% of the evidence-based therapies (antiplatelet agents, statins and ACE inhibitors) while those in the control group adhered to 58.7% of the performance measures, Dr. Berwanger said. That represents a gain of 25%. The study employed an “all-or-none” model. That is, participating sites were required to adopt all components of the quality-improvement initiative or none.

He noted that although the evidence supporting the use of platelet therapies, statins, and ACE inhibitors is strong, “translation of these findings in practice is clearly suboptimal.” He added, “It seems to be an even larger problem in settings like mine in Brazil, so quality-improvement interventions, especially in lower-resource settings such as low- and middle-income countries, are definitely needed.”

The quality-improvement model the trial evaluated involved two levels of intervention. The first level comprised three steps: a case manager evaluating the patient’s treatment needs with the aid of a checklist; then an evaluation by the physician; and then providing physicians with what Dr. Berwanger described as “a physician support tool” – a one-page summary of major guideline recommendations. The second level comprised monthly audit and feedback reports to the providers and patient education about lifestyle modification. Staff education and training was also provided to sites that adopted the model. “Our intervention was sort of based on behavioral marketing,” Dr. Berwanger said.

The trial also identified a number of trends among secondary endpoints, although the populations were too small to reach statistical significance. For example, Dr. Berwanger noted that intervention sites had higher use of high-dose statins and more than double the rate of smoking cessation. He also noted a 24% relative risk reduction in major cardiovascular events in the intervention group vs. controls. Among the intervention sites, teaching institutions seems to have a notable improvement in adherence outcomes than other settings, Dr. Berwanger said, but the study did not fully analyze that trend.

“We see this study not as the final word but as the first step,” he said. “More studies are needed.”

Dr. Berwanger reported receiving research support and/or honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Amgen, Bayer, Eurofarma, Servier, Novartis and NovoNordisk. Amgen sponsored the investigator-initiated trial.

SOURCE: Berwanger O, et al. AHA 2018 Abstr.19360.

CHICAGO – A multifaceted quality initiative that consists of staff education, patient reminders and a feedback loop may help to improve therapy adherence and encourage lifestyle changes of at-risk cardiovascular patients in settings with limited resources, according to results of a clinical trial from Brazil presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions 2018.

“In patients at high cardiovascular risk – in this case patients with established cardiovascular disease – a multifaceted quality-improvement intervention resulted in significant improvement in the use of evidence-based therapies,” said Otavio Berwanger, MD, PhD, of the Heart Hospital in Sao Paolo. He reported results of the BRIDGE Cardiovascular Prevention Cluster Randomized Trial. “The tools used in our trial can become the basis for developing quality-improvement programs to maximize the use of evidence-based therapies for the management of these high-risk patients with, especially in limited-resource settings.”

BRIDGE-CV included 1,619 patients from 40 care settings. Institutions that adopted the multifaceted intervention adhered to 73.5% of the evidence-based therapies (antiplatelet agents, statins and ACE inhibitors) while those in the control group adhered to 58.7% of the performance measures, Dr. Berwanger said. That represents a gain of 25%. The study employed an “all-or-none” model. That is, participating sites were required to adopt all components of the quality-improvement initiative or none.

He noted that although the evidence supporting the use of platelet therapies, statins, and ACE inhibitors is strong, “translation of these findings in practice is clearly suboptimal.” He added, “It seems to be an even larger problem in settings like mine in Brazil, so quality-improvement interventions, especially in lower-resource settings such as low- and middle-income countries, are definitely needed.”

The quality-improvement model the trial evaluated involved two levels of intervention. The first level comprised three steps: a case manager evaluating the patient’s treatment needs with the aid of a checklist; then an evaluation by the physician; and then providing physicians with what Dr. Berwanger described as “a physician support tool” – a one-page summary of major guideline recommendations. The second level comprised monthly audit and feedback reports to the providers and patient education about lifestyle modification. Staff education and training was also provided to sites that adopted the model. “Our intervention was sort of based on behavioral marketing,” Dr. Berwanger said.

The trial also identified a number of trends among secondary endpoints, although the populations were too small to reach statistical significance. For example, Dr. Berwanger noted that intervention sites had higher use of high-dose statins and more than double the rate of smoking cessation. He also noted a 24% relative risk reduction in major cardiovascular events in the intervention group vs. controls. Among the intervention sites, teaching institutions seems to have a notable improvement in adherence outcomes than other settings, Dr. Berwanger said, but the study did not fully analyze that trend.

“We see this study not as the final word but as the first step,” he said. “More studies are needed.”

Dr. Berwanger reported receiving research support and/or honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Amgen, Bayer, Eurofarma, Servier, Novartis and NovoNordisk. Amgen sponsored the investigator-initiated trial.

SOURCE: Berwanger O, et al. AHA 2018 Abstr.19360.

REPORTING FROM AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS 2018

Key clinical point: A multifaceted quality-improvement initiative led to improved adherence to evidence-based therapies.

Major finding: Sites that adopted the intervention had adherence rates 25% higher than control sites.

Study details: Two-arm, cluster-randomized, controlled trial of 1,619 high-risk, stable patients with established CVD from 40 sites.

Disclosures: Dr. Berwanger disclosed receiving research support and/or honoraria from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Bayer, Eurofarma, Servier, Novartis and NovoNordisk. Amgen sponsored the investigator-initiated trial.

Source: Berwanger O, et al. 2018-LBCT-19360-AHA.

Combination supplements show neuroprotective potential in Parkinson’s

NEW YORK – Preclinical studies have shown the natural supplements vinpocetine and pomegranate, along with vitamin B complex and vitamin E, may have some effect individually in providing neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease, but may have a more profound effect when used in combination, a researcher from Egypt reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“We need to carry out a clinical trial to ensure that this multiple direct strategy can provide protection in different stages of neurodegenerative disease – during induction and even during the progression of the disease,” said Azza Ali, PhD, of Al-Azhar University, Cairo. She presented a poster of her research in an unspecified number of rats with manganese-induced Parkinsonian symptoms. The goal of the study was to compare the oral supplements to each other and to evaluate their impact in combinations. Excessive levels of manganese have been associated with movement disorders similar to Parkinson’s disease.

The research involved histologic studies to evaluate the impact of the supplements in the brains, and evaluated biochemical, neuroinflammatory, apoptotic, and oxidative markers. Behavioral tests evaluated cognition, memory, and motor skills.

Histological studies of manganese-induced brains exhibited nuclear pyknosis – clumping of chromosomes, excessive chromatic aberrations, and shrinkage of the nucleus – in the neurons of the cerebral cortex as well as in some areas of the hippocampus, although no alteration was seen in the subiculum, Dr. Ali reported. The stria showed multiple plaque formations with nuclear pyknosis and degeneration in some neurons.

All the studied treatments improved motor, memory, and cognitive decline induced by manganese, with pomegranate and vinpocetine yielding the best results, Dr. Ali said. However, a combination of treatments showed more pronounced improvements in some biochemical markers, as well as the neuroinflammatory, apoptotic, and oxidative markers. “They have a high antioxidant and antiapoptotic effect,” Dr. Ali said. Histopathologic studies confirmed those results, she noted.

Pomegranate (150 mg/kg) had a somewhat positive effect in the subiculum and fascia dentate areas of the hippocampus, although the stria appeared similar to manganese-induced brains. With vinpocetine (20 mg/kg), neurons in the cerebral cortex showed intact histological structure with some degeneration and nuclear pyknosis in the subiculum. There was no alteration in the neurons of the fascia dentate, hilus, and stria of the hippocampus.

Histologic studies of induced brains after treatment with vitamin-B complex (8.5 mg/kg) showed nuclear pyknosis and degeneration in the neurons of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, including the subiculum. The stria also showed multiple focal eosinophilic plaques with nuclear pyknosis and degeneration in some neurons. Vitamin E (100 mg/kg) resulted in intact neurons in the cerebral cortex but not in the hippocampus.

Histopathologic studies of brains that received combination treatment showed no alteration in the neurons of the cerebral cortex or in the subiculum and fascia dentate of the hippocampus, although a few neurons in the stria showed nuclear pyknosis and degeneration, Dr. Ali said.

She had no financial relationships to disclose.

NEW YORK – Preclinical studies have shown the natural supplements vinpocetine and pomegranate, along with vitamin B complex and vitamin E, may have some effect individually in providing neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease, but may have a more profound effect when used in combination, a researcher from Egypt reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“We need to carry out a clinical trial to ensure that this multiple direct strategy can provide protection in different stages of neurodegenerative disease – during induction and even during the progression of the disease,” said Azza Ali, PhD, of Al-Azhar University, Cairo. She presented a poster of her research in an unspecified number of rats with manganese-induced Parkinsonian symptoms. The goal of the study was to compare the oral supplements to each other and to evaluate their impact in combinations. Excessive levels of manganese have been associated with movement disorders similar to Parkinson’s disease.

The research involved histologic studies to evaluate the impact of the supplements in the brains, and evaluated biochemical, neuroinflammatory, apoptotic, and oxidative markers. Behavioral tests evaluated cognition, memory, and motor skills.

Histological studies of manganese-induced brains exhibited nuclear pyknosis – clumping of chromosomes, excessive chromatic aberrations, and shrinkage of the nucleus – in the neurons of the cerebral cortex as well as in some areas of the hippocampus, although no alteration was seen in the subiculum, Dr. Ali reported. The stria showed multiple plaque formations with nuclear pyknosis and degeneration in some neurons.

All the studied treatments improved motor, memory, and cognitive decline induced by manganese, with pomegranate and vinpocetine yielding the best results, Dr. Ali said. However, a combination of treatments showed more pronounced improvements in some biochemical markers, as well as the neuroinflammatory, apoptotic, and oxidative markers. “They have a high antioxidant and antiapoptotic effect,” Dr. Ali said. Histopathologic studies confirmed those results, she noted.

Pomegranate (150 mg/kg) had a somewhat positive effect in the subiculum and fascia dentate areas of the hippocampus, although the stria appeared similar to manganese-induced brains. With vinpocetine (20 mg/kg), neurons in the cerebral cortex showed intact histological structure with some degeneration and nuclear pyknosis in the subiculum. There was no alteration in the neurons of the fascia dentate, hilus, and stria of the hippocampus.

Histologic studies of induced brains after treatment with vitamin-B complex (8.5 mg/kg) showed nuclear pyknosis and degeneration in the neurons of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, including the subiculum. The stria also showed multiple focal eosinophilic plaques with nuclear pyknosis and degeneration in some neurons. Vitamin E (100 mg/kg) resulted in intact neurons in the cerebral cortex but not in the hippocampus.

Histopathologic studies of brains that received combination treatment showed no alteration in the neurons of the cerebral cortex or in the subiculum and fascia dentate of the hippocampus, although a few neurons in the stria showed nuclear pyknosis and degeneration, Dr. Ali said.

She had no financial relationships to disclose.

NEW YORK – Preclinical studies have shown the natural supplements vinpocetine and pomegranate, along with vitamin B complex and vitamin E, may have some effect individually in providing neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease, but may have a more profound effect when used in combination, a researcher from Egypt reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“We need to carry out a clinical trial to ensure that this multiple direct strategy can provide protection in different stages of neurodegenerative disease – during induction and even during the progression of the disease,” said Azza Ali, PhD, of Al-Azhar University, Cairo. She presented a poster of her research in an unspecified number of rats with manganese-induced Parkinsonian symptoms. The goal of the study was to compare the oral supplements to each other and to evaluate their impact in combinations. Excessive levels of manganese have been associated with movement disorders similar to Parkinson’s disease.

The research involved histologic studies to evaluate the impact of the supplements in the brains, and evaluated biochemical, neuroinflammatory, apoptotic, and oxidative markers. Behavioral tests evaluated cognition, memory, and motor skills.

Histological studies of manganese-induced brains exhibited nuclear pyknosis – clumping of chromosomes, excessive chromatic aberrations, and shrinkage of the nucleus – in the neurons of the cerebral cortex as well as in some areas of the hippocampus, although no alteration was seen in the subiculum, Dr. Ali reported. The stria showed multiple plaque formations with nuclear pyknosis and degeneration in some neurons.

All the studied treatments improved motor, memory, and cognitive decline induced by manganese, with pomegranate and vinpocetine yielding the best results, Dr. Ali said. However, a combination of treatments showed more pronounced improvements in some biochemical markers, as well as the neuroinflammatory, apoptotic, and oxidative markers. “They have a high antioxidant and antiapoptotic effect,” Dr. Ali said. Histopathologic studies confirmed those results, she noted.

Pomegranate (150 mg/kg) had a somewhat positive effect in the subiculum and fascia dentate areas of the hippocampus, although the stria appeared similar to manganese-induced brains. With vinpocetine (20 mg/kg), neurons in the cerebral cortex showed intact histological structure with some degeneration and nuclear pyknosis in the subiculum. There was no alteration in the neurons of the fascia dentate, hilus, and stria of the hippocampus.

Histologic studies of induced brains after treatment with vitamin-B complex (8.5 mg/kg) showed nuclear pyknosis and degeneration in the neurons of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, including the subiculum. The stria also showed multiple focal eosinophilic plaques with nuclear pyknosis and degeneration in some neurons. Vitamin E (100 mg/kg) resulted in intact neurons in the cerebral cortex but not in the hippocampus.

Histopathologic studies of brains that received combination treatment showed no alteration in the neurons of the cerebral cortex or in the subiculum and fascia dentate of the hippocampus, although a few neurons in the stria showed nuclear pyknosis and degeneration, Dr. Ali said.

She had no financial relationships to disclose.

REPORTING FROM ICPDMD 2018

Can boxing training improve Parkinson reaction times?

NEW YORK – A small pilot study has shown that patients with Parkinson’s disease who participated in the Rock Steady Boxing non-contact training program may have faster reaction times than PD patients who did not participate in the program, according to a poster presented at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“The novelty of this is that it shows how Rock Steady Boxing and exercise programs that use sequences and the learning of sequences could possibly help slow the decline, or maintain a level of functioning longer, in Parkinson’s disease,” said Christopher McLeod, a second-year medical student at New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) College of Osteopathic Medicine, Old Westbury, N.Y.

Rock Steady Boxing is a non-contact program tailored to Parkinson’s patients founded in 2006 by Scott Newman, an Indiana lawyer who was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s at age 40. The regimen involves intense one-on-one training centered around boxing. Rock Steady Boxing offers classes from coast to coast in the United States and in 13 other countries. Mr. McLeod is a volunteer at the NYIT chapter of Rock Steady Boxing in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Mr. McLeod studied 28 PD patients – 14 who had been taking Rock Steady Boxing classes at NYIT for at least 6 months and 14 controls. The goal of the study was to evaluate if the Rock Steady Boxing participants showed any improvement in procedural motor learning. His coauthor was Adena Leder, DO, a faculty neurologist and movement disorder specialist at NYIT,

“What’s new about this research is the procedural memory component and the Rock Steady Boxing program is just more of the vessel, so to speak,” Mr. McLeod said. “This is a pilot study. We wanted to see if Rock Steady Boxing would show benefits in these patients. There are some trends in my research that [indicate] it would; it did not have statistical significance, but we did see trend lines.”

The researchers used a modified Serial Reaction Time Test (SRTT) composed of seven blocks of 10 stimuli each with 30-second breaks between blocks. Blocks consisted of a random familiarization block, four learning blocks repeating the same sequence of stimuli, a transfer block of random stimuli, and a posttransfer block presenting the same sequence of stimuli from the four learning blocks.

They assessed procedural learning by comparing the reduction in response time over the four identical learning blocks as well as by comparing changes in response time when the subjects were subsequently exposed to the random transfer block.

Experienced boxers demonstrated faster reaction time over the four learning blocks, ranging from 795.32 vs. 906.89 ms in the first learning block to 674.79 vs. 787.32 ms in the fourth learning block (P = .19). In the random sequence transfer block, controls showed a 93.5-ms decrease in median reaction time vs. a 27.3-ms increase in reaction time of experienced boxers. One possible explanation the investigators noted is that the controls simply got better at reading the stimuli over time without actually learning the repeated sequence.

Mr. McLeod noted that a typical Rock Steady Boxing session starts with a warmup and stretch, then learning the boxing stance with the nondominant foot back, shoulders over the body and the head over the feet. The boxing moves involve sequences of different punching combinations — jab, jab, cross; left, left, right; jab, cross, hook. Then the class divides into separate circuits for boxing and exercise. The boxing circuit involves punching the speed bag – the small, air-filled, pear-shaped bag attached to a hook at eye level – as well as heavy bag and partner-held focus mitts, all with the aim of reinforcing the learned sequences. The exercise circuit focuses on muscle training and exercise with the goal of improving balance and gait.

“The boxing sequences help not only with cognitive ability but motor control,” Mr. McLeod said. “The program also helps with some of the nonmotor aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Depression is almost synonymous with Parkinson’s disease; this brings people together and builds camaraderie.”

Mr. McLeod said he hopes the research continues. “I’m hoping that this can be a jumping-off point for research going forward with procedural memory, Parkinson’s, and Rock Steady Boxing or programs like it,” he said. Future research should involve more subjects, measure improvement within same subjects who participate in the program, and account for variables such as age and gender.

Mr. McLeod and Dr. Leder reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – A small pilot study has shown that patients with Parkinson’s disease who participated in the Rock Steady Boxing non-contact training program may have faster reaction times than PD patients who did not participate in the program, according to a poster presented at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“The novelty of this is that it shows how Rock Steady Boxing and exercise programs that use sequences and the learning of sequences could possibly help slow the decline, or maintain a level of functioning longer, in Parkinson’s disease,” said Christopher McLeod, a second-year medical student at New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) College of Osteopathic Medicine, Old Westbury, N.Y.

Rock Steady Boxing is a non-contact program tailored to Parkinson’s patients founded in 2006 by Scott Newman, an Indiana lawyer who was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s at age 40. The regimen involves intense one-on-one training centered around boxing. Rock Steady Boxing offers classes from coast to coast in the United States and in 13 other countries. Mr. McLeod is a volunteer at the NYIT chapter of Rock Steady Boxing in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Mr. McLeod studied 28 PD patients – 14 who had been taking Rock Steady Boxing classes at NYIT for at least 6 months and 14 controls. The goal of the study was to evaluate if the Rock Steady Boxing participants showed any improvement in procedural motor learning. His coauthor was Adena Leder, DO, a faculty neurologist and movement disorder specialist at NYIT,

“What’s new about this research is the procedural memory component and the Rock Steady Boxing program is just more of the vessel, so to speak,” Mr. McLeod said. “This is a pilot study. We wanted to see if Rock Steady Boxing would show benefits in these patients. There are some trends in my research that [indicate] it would; it did not have statistical significance, but we did see trend lines.”

The researchers used a modified Serial Reaction Time Test (SRTT) composed of seven blocks of 10 stimuli each with 30-second breaks between blocks. Blocks consisted of a random familiarization block, four learning blocks repeating the same sequence of stimuli, a transfer block of random stimuli, and a posttransfer block presenting the same sequence of stimuli from the four learning blocks.

They assessed procedural learning by comparing the reduction in response time over the four identical learning blocks as well as by comparing changes in response time when the subjects were subsequently exposed to the random transfer block.

Experienced boxers demonstrated faster reaction time over the four learning blocks, ranging from 795.32 vs. 906.89 ms in the first learning block to 674.79 vs. 787.32 ms in the fourth learning block (P = .19). In the random sequence transfer block, controls showed a 93.5-ms decrease in median reaction time vs. a 27.3-ms increase in reaction time of experienced boxers. One possible explanation the investigators noted is that the controls simply got better at reading the stimuli over time without actually learning the repeated sequence.

Mr. McLeod noted that a typical Rock Steady Boxing session starts with a warmup and stretch, then learning the boxing stance with the nondominant foot back, shoulders over the body and the head over the feet. The boxing moves involve sequences of different punching combinations — jab, jab, cross; left, left, right; jab, cross, hook. Then the class divides into separate circuits for boxing and exercise. The boxing circuit involves punching the speed bag – the small, air-filled, pear-shaped bag attached to a hook at eye level – as well as heavy bag and partner-held focus mitts, all with the aim of reinforcing the learned sequences. The exercise circuit focuses on muscle training and exercise with the goal of improving balance and gait.

“The boxing sequences help not only with cognitive ability but motor control,” Mr. McLeod said. “The program also helps with some of the nonmotor aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Depression is almost synonymous with Parkinson’s disease; this brings people together and builds camaraderie.”

Mr. McLeod said he hopes the research continues. “I’m hoping that this can be a jumping-off point for research going forward with procedural memory, Parkinson’s, and Rock Steady Boxing or programs like it,” he said. Future research should involve more subjects, measure improvement within same subjects who participate in the program, and account for variables such as age and gender.

Mr. McLeod and Dr. Leder reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – A small pilot study has shown that patients with Parkinson’s disease who participated in the Rock Steady Boxing non-contact training program may have faster reaction times than PD patients who did not participate in the program, according to a poster presented at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“The novelty of this is that it shows how Rock Steady Boxing and exercise programs that use sequences and the learning of sequences could possibly help slow the decline, or maintain a level of functioning longer, in Parkinson’s disease,” said Christopher McLeod, a second-year medical student at New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) College of Osteopathic Medicine, Old Westbury, N.Y.

Rock Steady Boxing is a non-contact program tailored to Parkinson’s patients founded in 2006 by Scott Newman, an Indiana lawyer who was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s at age 40. The regimen involves intense one-on-one training centered around boxing. Rock Steady Boxing offers classes from coast to coast in the United States and in 13 other countries. Mr. McLeod is a volunteer at the NYIT chapter of Rock Steady Boxing in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Mr. McLeod studied 28 PD patients – 14 who had been taking Rock Steady Boxing classes at NYIT for at least 6 months and 14 controls. The goal of the study was to evaluate if the Rock Steady Boxing participants showed any improvement in procedural motor learning. His coauthor was Adena Leder, DO, a faculty neurologist and movement disorder specialist at NYIT,

“What’s new about this research is the procedural memory component and the Rock Steady Boxing program is just more of the vessel, so to speak,” Mr. McLeod said. “This is a pilot study. We wanted to see if Rock Steady Boxing would show benefits in these patients. There are some trends in my research that [indicate] it would; it did not have statistical significance, but we did see trend lines.”

The researchers used a modified Serial Reaction Time Test (SRTT) composed of seven blocks of 10 stimuli each with 30-second breaks between blocks. Blocks consisted of a random familiarization block, four learning blocks repeating the same sequence of stimuli, a transfer block of random stimuli, and a posttransfer block presenting the same sequence of stimuli from the four learning blocks.

They assessed procedural learning by comparing the reduction in response time over the four identical learning blocks as well as by comparing changes in response time when the subjects were subsequently exposed to the random transfer block.

Experienced boxers demonstrated faster reaction time over the four learning blocks, ranging from 795.32 vs. 906.89 ms in the first learning block to 674.79 vs. 787.32 ms in the fourth learning block (P = .19). In the random sequence transfer block, controls showed a 93.5-ms decrease in median reaction time vs. a 27.3-ms increase in reaction time of experienced boxers. One possible explanation the investigators noted is that the controls simply got better at reading the stimuli over time without actually learning the repeated sequence.

Mr. McLeod noted that a typical Rock Steady Boxing session starts with a warmup and stretch, then learning the boxing stance with the nondominant foot back, shoulders over the body and the head over the feet. The boxing moves involve sequences of different punching combinations — jab, jab, cross; left, left, right; jab, cross, hook. Then the class divides into separate circuits for boxing and exercise. The boxing circuit involves punching the speed bag – the small, air-filled, pear-shaped bag attached to a hook at eye level – as well as heavy bag and partner-held focus mitts, all with the aim of reinforcing the learned sequences. The exercise circuit focuses on muscle training and exercise with the goal of improving balance and gait.

“The boxing sequences help not only with cognitive ability but motor control,” Mr. McLeod said. “The program also helps with some of the nonmotor aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Depression is almost synonymous with Parkinson’s disease; this brings people together and builds camaraderie.”

Mr. McLeod said he hopes the research continues. “I’m hoping that this can be a jumping-off point for research going forward with procedural memory, Parkinson’s, and Rock Steady Boxing or programs like it,” he said. Future research should involve more subjects, measure improvement within same subjects who participate in the program, and account for variables such as age and gender.

Mr. McLeod and Dr. Leder reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ICPDMD 2018

Key clinical point: Exercise programs may help improve procedural learning in individuals with Parkinson’s disease.

Major finding: Rock Steady Boxing experienced boxers demonstrated reaction times ranging from 795.32 vs. 906.89 ms to 674.79 vs. 787.32 ms across four test blocks.

Study details: Pilot study of 14 Parkinson’s patients who participated in Rock Steady Boxing vs. 14 controls.

Disclosures: Mr. McLeod reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Novel imaging may differentiate dementia in Parkinson’s

NEW YORK – Making the clinical diagnosis of dementia in Parkinson’s patients has been confounding because of the difficulty of differentiating it from dementia in Alzheimer’s disease, but researchers have developed a novel imaging technique, known as single-scan dynamic molecular imaging, which uses positron emission tomography to identify the key differentiating factor between the two types of dementia, as reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“We have a technique with which we can detect neurotransmitters in the brain, particularly in patients with dementia,” said Rajendra D. Badgaiyan, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. “This is important to not only understand the type of dementia you’re dealing with but also to understand the underlying neurocognitive problem.”

The technique is called single-scan dynamic molecular imaging technique (SDMIT) and uses PET to detect and measure dopamine release activity in the brain during cognitive or behavioral functioning, he said. After patients are placed in the PET scanner, they receive an IV injection of the radio-labeled ligand fallypride. While in the PET scanner, patients are asked to perform a cognitive task, and PET measures the ligand concentration before and after the task in the dorsal striatum of the brain. The rate of ligand displacement before and after the task are compared to determine the levels of dopamine activity in the brain.