User login

Chronic pain and psychiatric illness: Managing comorbid conditions

Pain is one of the most common symptoms for which patients seek medical care, with an associated estimated annual cost of $600 billion.1 Using a multimodal approach to care—thorough evaluation, cognitive-behavioral and psychophysiological therapy, physical therapy, medications, and other interventions—can help patients effectively manage their condition and achieve healthier outcomes.

Evaluating a patient with pain

When developing a safe, comprehensive, and effective treatment plan for patients with chronic pain, first perform a thorough history and physical exam using the following elements:

Pain history. The PQRST mnemonic (Table 1) can help you obtain critical information and assist in determining the appropriate diagnosis and cause of the patient’s pain complaints.

Psychiatric history. Document the mental health history of the patient and first-degree relatives.

Medical history. Knowing the medical history could reveal comorbidities contributing to a patient’s pain complaint.

Treatment history. Listing past and current treatments for pain, including effectiveness, helps the clinician understand if an existing treatment plan should be modified.

Functional status. Document current level of daily activity, how life activities are affected by pain; strategies used to help cope with pain; level of physical and emotional support provided in home, work, and school environments; and active stressors (eg, financial, interpersonal).

Psychosocial history. Document historical information related to coping skills, trauma history, family of origin, abuse, interpersonal relationships, social support, and academic and vocational functioning.

Substance use or abuse. Assess for use of controlled substances (ie, early refills; lost medications; obtaining medications from multiple prescribers, friends, families, or strangers; use of prescribed and non-prescribed medications for non-medical and medical purposes), nicotine, alcohol, illicit substances, and caffeine. A thorough inventory can help to identify substances a patient is using that could affect daily functioning and pain level.

Behavioral observations. Assessing mental status (eg, insight, pain behavior, cooperation) can be useful. Paying attention to pain behaviors, such as complaints of pain, decreased activity, increased medication intake, or altered facial expressions or body posture, can help the clinician gain insight to the extent that pain affects the patient’s quality of life.

The information gathered in the patient evaluation can be used to design a multimodal treatment plan to achieve maximum effectiveness.

Assessing psychiatric illness

Current approaches to pain evaluation and treatment recommend use of a biopsychosocial orientation because psychological, behavioral, and social factors can influence the experience and impact of pain, regardless of the primary cause.2 A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan should consider the broader context in which a patient’s pain occurs.

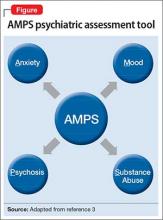

Regarding psychiatric illness, past and current symptoms, treatment history, and risk assessment should all be included. Using the “AMPS approach” (Figure)3—assessing Anxiety, Mood (depression and mania), Psychotic symptoms (paranoid ideation and hallucinations), and Substance use—helps screen for comorbid psychiatric conditions in patients with chronic pain.

Sleep assessment

Chronic pain patients often experience significant sleep disturbance that could be caused by physiological aspects of the pain condition, environmental factors (eg, uncomfortable bedding), a comorbid sleep disorder (eg, sleep apnea), a psychiatric disorder, or a combination of the above.

Obstructive and central sleep apnea are characterized by nighttime hypoxia, which leads to frequent disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and often manifests as daytime fatigue, irritability, depression, drowsiness, headaches, and increased pain sensitivity. Changes in sleep arousal can lead to neuropsychological changes during the day, such as decreased attention, memory problems, impaired executive functioning, and reduced impulse control.

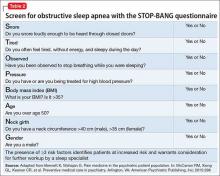

Screen patients for central and obstructive sleep apnea before prescribing opioids or benzodiazepines for pain because these medications can cause or exacerbate underlying sleep apnea. Although many screening tools, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, assess daytime somnolence,4 the STOP-BANG questionnaire is a quick, validated, and efficient screening tool that often is used to assess sleep apnea risk5,6 (Table 2). The presence of ≥3 risk factors identifies patients at increased risk and warrants consideration for further workup by a sleep specialist.7,8

Pharmacotherapy for chronic pain

Non-opioid medications. Pain can be broadly categorized as neuropathic or nociceptive. Neuropathic pain can be described by patients as numbness, burning, electric-like, and tingling, and is associated with nerve damage. Nociceptive pain commonly is described as similar to a toothache with descriptors such as stabbing, sharp, or a dull aching sensation; it is often, but not always, associated with acute injury or ongoing trauma to tissue. Drug treatment is most successful when the appropriate class of medication is matched to the specific type of pain.

Nociceptive pain often is successfully treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen. Non-selective COX inhibitors (eg, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac) and COX-2 selective inhibitors (eg, celecoxib) have been associated with cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal disease; acetaminophen is associated with liver dysfunction.9-11 However, the absolute risk for complications in healthy patients is low.12 To minimize risk, use these agents for the shortest duration and at the lowest effective dosage possible.

Neuropathic pain can be addressed with certain antidepressants13—specifically, those that increase serotonin and norepinephrine (eg, tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs] and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs]), or medications that block ion channels (eg, anticonvulsants). TCAs (eg, desipramine, nortriptyline, amitriptyline) are among the best studied and most cost effective medications for treating neuropathic pain,14,15 but they can have sedating and anticholinergic effects, as well as cardiac adverse effects (ie, prolongation of the QTc interval). SNRIs (eg, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran) can be effective and often are better tolerated than TCAs.14

Some newer anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin and pregabalin) have been found to be more effective than placebo for a variety of neuropathic pain conditions.16,17 Although they have few drug-drug interactions, anticonvulsants can cause dizziness, forgetfulness, and sedation. These adverse effects can be minimized by starting at a low dosage and titrating carefully. Because hepatic or renal impairment can affect metabolism or excretion of these drugs, review the prescribing information to determine safe dosing.

Targeted injection of medications to major pain generators (eg, an epidural steroid for radicular neck and back pain; facet injections for facet-related neck and back pain; trigger point injections for myofascial pain; occipital nerve blocks for occipital neuralgia; and botulinum toxin A injections for chronic migraine headache) can be effective in reducing discomfort and increasing function in patients with chronic pain. A detailed discussion of such therapies is beyond the scope of this article, but have been reviewed extensively elsewhere.18,19

Opioids. Although there is little evidence of long-term efficacy with chronic opioid therapy for most patients, a trial of opioids might be warranted for select patients who do not respond to other medications. Because the risk–benefit ratio for chronic opioid therapy is high,20-22 a decision to initiate a trial of a low-dosage opioid should be made only after careful consideration of those risks. It is generally agreed that treatment of chronic pain with low-dosage opioid therapy is more likely to be successful when it is used as an adjuvant to non-opioid modalities (eg, physical reconditioning, injection therapies, spinal cord stimulation, neurobehavioral interventions, non-opioid medications).

The Federation of State Medical Boards has stated that excessive reliance on opioid medications for treating chronic pain is a deviation from best practices.23 To maximize benefit and minimize risk, clinicians should carefully select appropriate patients, establish functional goals, and regularly monitor for efficacy and compliance. Thoroughly document these steps in the patient’s record for later reference.23

After establishing a clinical diagnosis for the cause of the pain, you should determine the risk of opioid abuse or misuse by using any one of the available risk assessment tools (Box). Understand, however, that no single tool has been shown to be more effective than others.

Although patients and some clinicians tend to overvalue the benefits of chronic opioid therapy, many do not fully appreciate the risks (eg, respiratory depression and death), which can be exacerbated if the patient is using other substance that suppress respiration (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, and illicit substances). Written informed consent and treatment agreement is highly recommended; components of such a document are listed in Table 3.23

Develop a treatment plan that emphasizes functional goals based on the patient’s physical limitations and that incorporates some type of daily, atraumatic physical activity. This plan should be documented and reviewed regularly to help monitor treatment effectiveness.

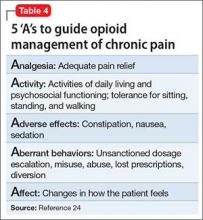

After an initial trial of a few weeks, the patient and clinician should meet to review the 5 “A”s (Table 4)24 to determine the success of the opioid regimen. Consulting your state’s prescription drug monitoring program (if one is available), obtaining a random urine drug test, and doing a pill count can provide useful, objective data. If the patient has not made progress but has experienced no adverse effects, then a small dosage increase might be warranted. If any of the 5 “A”s indicates lack of improvement or increased risk, consider stopping opioid therapy and exploring non-opioid options to manage chronic pain.

Referrals to a pain specialist or an addiction specialist, or both, might be needed, depending on the patient’s condition at any given follow-up visit. Such referral decisions, as well as all treatment plans, should be documented clearly in the medical record to prevent any misunderstanding, false accusations, or medicolegal repercussions regarding the rationale for continuing or terminating opioid-based treatment.

Non-pharmaceutical therapy for treating pain

The pain management field has successfully integrated the biopsychosocial model into regular practice. This model advocates the use of multimodal non-drug interventions in conjunction with opioid and non-opioid medications. Such interventions address behavioral, cognitive, sociocultural (psychosocial), lifestyle, and physiological dimensions of pain. A partial list of non-drug interventions is provided in Table 5.

Integration of these interventions within a biopsychosocial framework can assist you in making a comprehensive treatment plan. For example, patients with focal myofascial shoulder and back pain might derive only transient benefit from trigger point injection. However, concurrent referral to a pain psychologist and physical therapist could substantially improve functional outcomes by addressing factors that directly and indirectly influence myofascial pain. Inclusion of cognitive-behavioral therapy (addressing psychosocial and lifestyle dimensions), surface electromyography, psychophysiological interventions/biofeedback (addressing psychosocial, lifestyle, and physiological dimensions), and physical therapy (addressing lifestyle and physiological dimensions) allows the patient to learn coping skills, decrease physiological arousal that can lead to unnecessary tensing of muscles, and strengthen core muscle groups.

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20 Files/2011/Relieving-Pain-in-America-A-Blueprint-for- Transforming-Prevention-Care-Education-Research/ Pain%20Research%202011%20Report%20Brief.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed April 15, 2015.

2. Jensen MP, Moore MR, Bockow TB, et al. Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in persons with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(1):146-160.

3. McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

4. Abrishami A, Khajehdehi A, Chung F. A systematic review of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):423-438.

5. Boynton G, Vahabzadeh A, Hammoud S, et al. Validation of the STOP-BANG questionnaire among patients referred for suspected obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Disord Treat Care. 2013;2(4). doi: 10.4172/2325-9639.1000121.

6. Vana KD, Silva GE, Goldberg R. Predictive abilities of the STOP-Bang and Epworth Sleepiness Scale in identifying sleep clinic patients at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(1):84-94.

7. Chung F, Elsaid H. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea before surgery: why is it important? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22(3):405-411.

8. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821.

9. Forman JP, Rimm EB, Curhan GC. Frequency of analgesic use and risk of hypertension among men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):394-399.

10. Sudano I, Flammer AJ, Périat D, et al. Acetaminophen increases blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1789-1796.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers about oral prescription acetaminophen products to be limited to 325 mg per dosage unit. http://www.fda.gov/ drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/ucm239871. htm. Updated December 11, 2014. Accessed February 23, 2015.

12. Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al; Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769-779.

13. Sullivan MD, Robinson JP. Antidepressant and anticonvulsant medication for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17(2):381-400, vi-vii.

14. Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, et al. Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96(6):399-409.

15. Pilowsky I, Hallett EC, Bassett DL, et al. A controlled study of amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain. Pain. 1982;14(2):169-179.

16. Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150(3):573-581.

17. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

18. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. An update of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in chronic spinal pain. Part II: guidance and recommendations. Pain Physician. 2013;16(suppl 2):S49-S283.

19. Singh V, Trescot A, Nishio I. Injections for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):249-261.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers— United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492.

21. Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659.

22. Chen L, Vo T, Seefeld L, et al. Lack of correlation between opioid dose adjustment and pain score change in a group of chronic pain patients. J Pain. 2013;14(4):384-392.

23. Federation of State Medical Boards. Model policy for the use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of chronic pain. http:// www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/ pain_policy_july2013.pdf. Published July 2013. Accessed December 18, 2015.

24. Passik SD, Weinreb HJ. Managing chronic nonmalignant pain: overcoming obstacles to the use of opioids. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):70-83.

Pain is one of the most common symptoms for which patients seek medical care, with an associated estimated annual cost of $600 billion.1 Using a multimodal approach to care—thorough evaluation, cognitive-behavioral and psychophysiological therapy, physical therapy, medications, and other interventions—can help patients effectively manage their condition and achieve healthier outcomes.

Evaluating a patient with pain

When developing a safe, comprehensive, and effective treatment plan for patients with chronic pain, first perform a thorough history and physical exam using the following elements:

Pain history. The PQRST mnemonic (Table 1) can help you obtain critical information and assist in determining the appropriate diagnosis and cause of the patient’s pain complaints.

Psychiatric history. Document the mental health history of the patient and first-degree relatives.

Medical history. Knowing the medical history could reveal comorbidities contributing to a patient’s pain complaint.

Treatment history. Listing past and current treatments for pain, including effectiveness, helps the clinician understand if an existing treatment plan should be modified.

Functional status. Document current level of daily activity, how life activities are affected by pain; strategies used to help cope with pain; level of physical and emotional support provided in home, work, and school environments; and active stressors (eg, financial, interpersonal).

Psychosocial history. Document historical information related to coping skills, trauma history, family of origin, abuse, interpersonal relationships, social support, and academic and vocational functioning.

Substance use or abuse. Assess for use of controlled substances (ie, early refills; lost medications; obtaining medications from multiple prescribers, friends, families, or strangers; use of prescribed and non-prescribed medications for non-medical and medical purposes), nicotine, alcohol, illicit substances, and caffeine. A thorough inventory can help to identify substances a patient is using that could affect daily functioning and pain level.

Behavioral observations. Assessing mental status (eg, insight, pain behavior, cooperation) can be useful. Paying attention to pain behaviors, such as complaints of pain, decreased activity, increased medication intake, or altered facial expressions or body posture, can help the clinician gain insight to the extent that pain affects the patient’s quality of life.

The information gathered in the patient evaluation can be used to design a multimodal treatment plan to achieve maximum effectiveness.

Assessing psychiatric illness

Current approaches to pain evaluation and treatment recommend use of a biopsychosocial orientation because psychological, behavioral, and social factors can influence the experience and impact of pain, regardless of the primary cause.2 A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan should consider the broader context in which a patient’s pain occurs.

Regarding psychiatric illness, past and current symptoms, treatment history, and risk assessment should all be included. Using the “AMPS approach” (Figure)3—assessing Anxiety, Mood (depression and mania), Psychotic symptoms (paranoid ideation and hallucinations), and Substance use—helps screen for comorbid psychiatric conditions in patients with chronic pain.

Sleep assessment

Chronic pain patients often experience significant sleep disturbance that could be caused by physiological aspects of the pain condition, environmental factors (eg, uncomfortable bedding), a comorbid sleep disorder (eg, sleep apnea), a psychiatric disorder, or a combination of the above.

Obstructive and central sleep apnea are characterized by nighttime hypoxia, which leads to frequent disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and often manifests as daytime fatigue, irritability, depression, drowsiness, headaches, and increased pain sensitivity. Changes in sleep arousal can lead to neuropsychological changes during the day, such as decreased attention, memory problems, impaired executive functioning, and reduced impulse control.

Screen patients for central and obstructive sleep apnea before prescribing opioids or benzodiazepines for pain because these medications can cause or exacerbate underlying sleep apnea. Although many screening tools, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, assess daytime somnolence,4 the STOP-BANG questionnaire is a quick, validated, and efficient screening tool that often is used to assess sleep apnea risk5,6 (Table 2). The presence of ≥3 risk factors identifies patients at increased risk and warrants consideration for further workup by a sleep specialist.7,8

Pharmacotherapy for chronic pain

Non-opioid medications. Pain can be broadly categorized as neuropathic or nociceptive. Neuropathic pain can be described by patients as numbness, burning, electric-like, and tingling, and is associated with nerve damage. Nociceptive pain commonly is described as similar to a toothache with descriptors such as stabbing, sharp, or a dull aching sensation; it is often, but not always, associated with acute injury or ongoing trauma to tissue. Drug treatment is most successful when the appropriate class of medication is matched to the specific type of pain.

Nociceptive pain often is successfully treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen. Non-selective COX inhibitors (eg, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac) and COX-2 selective inhibitors (eg, celecoxib) have been associated with cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal disease; acetaminophen is associated with liver dysfunction.9-11 However, the absolute risk for complications in healthy patients is low.12 To minimize risk, use these agents for the shortest duration and at the lowest effective dosage possible.

Neuropathic pain can be addressed with certain antidepressants13—specifically, those that increase serotonin and norepinephrine (eg, tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs] and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs]), or medications that block ion channels (eg, anticonvulsants). TCAs (eg, desipramine, nortriptyline, amitriptyline) are among the best studied and most cost effective medications for treating neuropathic pain,14,15 but they can have sedating and anticholinergic effects, as well as cardiac adverse effects (ie, prolongation of the QTc interval). SNRIs (eg, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran) can be effective and often are better tolerated than TCAs.14

Some newer anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin and pregabalin) have been found to be more effective than placebo for a variety of neuropathic pain conditions.16,17 Although they have few drug-drug interactions, anticonvulsants can cause dizziness, forgetfulness, and sedation. These adverse effects can be minimized by starting at a low dosage and titrating carefully. Because hepatic or renal impairment can affect metabolism or excretion of these drugs, review the prescribing information to determine safe dosing.

Targeted injection of medications to major pain generators (eg, an epidural steroid for radicular neck and back pain; facet injections for facet-related neck and back pain; trigger point injections for myofascial pain; occipital nerve blocks for occipital neuralgia; and botulinum toxin A injections for chronic migraine headache) can be effective in reducing discomfort and increasing function in patients with chronic pain. A detailed discussion of such therapies is beyond the scope of this article, but have been reviewed extensively elsewhere.18,19

Opioids. Although there is little evidence of long-term efficacy with chronic opioid therapy for most patients, a trial of opioids might be warranted for select patients who do not respond to other medications. Because the risk–benefit ratio for chronic opioid therapy is high,20-22 a decision to initiate a trial of a low-dosage opioid should be made only after careful consideration of those risks. It is generally agreed that treatment of chronic pain with low-dosage opioid therapy is more likely to be successful when it is used as an adjuvant to non-opioid modalities (eg, physical reconditioning, injection therapies, spinal cord stimulation, neurobehavioral interventions, non-opioid medications).

The Federation of State Medical Boards has stated that excessive reliance on opioid medications for treating chronic pain is a deviation from best practices.23 To maximize benefit and minimize risk, clinicians should carefully select appropriate patients, establish functional goals, and regularly monitor for efficacy and compliance. Thoroughly document these steps in the patient’s record for later reference.23

After establishing a clinical diagnosis for the cause of the pain, you should determine the risk of opioid abuse or misuse by using any one of the available risk assessment tools (Box). Understand, however, that no single tool has been shown to be more effective than others.

Although patients and some clinicians tend to overvalue the benefits of chronic opioid therapy, many do not fully appreciate the risks (eg, respiratory depression and death), which can be exacerbated if the patient is using other substance that suppress respiration (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, and illicit substances). Written informed consent and treatment agreement is highly recommended; components of such a document are listed in Table 3.23

Develop a treatment plan that emphasizes functional goals based on the patient’s physical limitations and that incorporates some type of daily, atraumatic physical activity. This plan should be documented and reviewed regularly to help monitor treatment effectiveness.

After an initial trial of a few weeks, the patient and clinician should meet to review the 5 “A”s (Table 4)24 to determine the success of the opioid regimen. Consulting your state’s prescription drug monitoring program (if one is available), obtaining a random urine drug test, and doing a pill count can provide useful, objective data. If the patient has not made progress but has experienced no adverse effects, then a small dosage increase might be warranted. If any of the 5 “A”s indicates lack of improvement or increased risk, consider stopping opioid therapy and exploring non-opioid options to manage chronic pain.

Referrals to a pain specialist or an addiction specialist, or both, might be needed, depending on the patient’s condition at any given follow-up visit. Such referral decisions, as well as all treatment plans, should be documented clearly in the medical record to prevent any misunderstanding, false accusations, or medicolegal repercussions regarding the rationale for continuing or terminating opioid-based treatment.

Non-pharmaceutical therapy for treating pain

The pain management field has successfully integrated the biopsychosocial model into regular practice. This model advocates the use of multimodal non-drug interventions in conjunction with opioid and non-opioid medications. Such interventions address behavioral, cognitive, sociocultural (psychosocial), lifestyle, and physiological dimensions of pain. A partial list of non-drug interventions is provided in Table 5.

Integration of these interventions within a biopsychosocial framework can assist you in making a comprehensive treatment plan. For example, patients with focal myofascial shoulder and back pain might derive only transient benefit from trigger point injection. However, concurrent referral to a pain psychologist and physical therapist could substantially improve functional outcomes by addressing factors that directly and indirectly influence myofascial pain. Inclusion of cognitive-behavioral therapy (addressing psychosocial and lifestyle dimensions), surface electromyography, psychophysiological interventions/biofeedback (addressing psychosocial, lifestyle, and physiological dimensions), and physical therapy (addressing lifestyle and physiological dimensions) allows the patient to learn coping skills, decrease physiological arousal that can lead to unnecessary tensing of muscles, and strengthen core muscle groups.

Pain is one of the most common symptoms for which patients seek medical care, with an associated estimated annual cost of $600 billion.1 Using a multimodal approach to care—thorough evaluation, cognitive-behavioral and psychophysiological therapy, physical therapy, medications, and other interventions—can help patients effectively manage their condition and achieve healthier outcomes.

Evaluating a patient with pain

When developing a safe, comprehensive, and effective treatment plan for patients with chronic pain, first perform a thorough history and physical exam using the following elements:

Pain history. The PQRST mnemonic (Table 1) can help you obtain critical information and assist in determining the appropriate diagnosis and cause of the patient’s pain complaints.

Psychiatric history. Document the mental health history of the patient and first-degree relatives.

Medical history. Knowing the medical history could reveal comorbidities contributing to a patient’s pain complaint.

Treatment history. Listing past and current treatments for pain, including effectiveness, helps the clinician understand if an existing treatment plan should be modified.

Functional status. Document current level of daily activity, how life activities are affected by pain; strategies used to help cope with pain; level of physical and emotional support provided in home, work, and school environments; and active stressors (eg, financial, interpersonal).

Psychosocial history. Document historical information related to coping skills, trauma history, family of origin, abuse, interpersonal relationships, social support, and academic and vocational functioning.

Substance use or abuse. Assess for use of controlled substances (ie, early refills; lost medications; obtaining medications from multiple prescribers, friends, families, or strangers; use of prescribed and non-prescribed medications for non-medical and medical purposes), nicotine, alcohol, illicit substances, and caffeine. A thorough inventory can help to identify substances a patient is using that could affect daily functioning and pain level.

Behavioral observations. Assessing mental status (eg, insight, pain behavior, cooperation) can be useful. Paying attention to pain behaviors, such as complaints of pain, decreased activity, increased medication intake, or altered facial expressions or body posture, can help the clinician gain insight to the extent that pain affects the patient’s quality of life.

The information gathered in the patient evaluation can be used to design a multimodal treatment plan to achieve maximum effectiveness.

Assessing psychiatric illness

Current approaches to pain evaluation and treatment recommend use of a biopsychosocial orientation because psychological, behavioral, and social factors can influence the experience and impact of pain, regardless of the primary cause.2 A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan should consider the broader context in which a patient’s pain occurs.

Regarding psychiatric illness, past and current symptoms, treatment history, and risk assessment should all be included. Using the “AMPS approach” (Figure)3—assessing Anxiety, Mood (depression and mania), Psychotic symptoms (paranoid ideation and hallucinations), and Substance use—helps screen for comorbid psychiatric conditions in patients with chronic pain.

Sleep assessment

Chronic pain patients often experience significant sleep disturbance that could be caused by physiological aspects of the pain condition, environmental factors (eg, uncomfortable bedding), a comorbid sleep disorder (eg, sleep apnea), a psychiatric disorder, or a combination of the above.

Obstructive and central sleep apnea are characterized by nighttime hypoxia, which leads to frequent disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and often manifests as daytime fatigue, irritability, depression, drowsiness, headaches, and increased pain sensitivity. Changes in sleep arousal can lead to neuropsychological changes during the day, such as decreased attention, memory problems, impaired executive functioning, and reduced impulse control.

Screen patients for central and obstructive sleep apnea before prescribing opioids or benzodiazepines for pain because these medications can cause or exacerbate underlying sleep apnea. Although many screening tools, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, assess daytime somnolence,4 the STOP-BANG questionnaire is a quick, validated, and efficient screening tool that often is used to assess sleep apnea risk5,6 (Table 2). The presence of ≥3 risk factors identifies patients at increased risk and warrants consideration for further workup by a sleep specialist.7,8

Pharmacotherapy for chronic pain

Non-opioid medications. Pain can be broadly categorized as neuropathic or nociceptive. Neuropathic pain can be described by patients as numbness, burning, electric-like, and tingling, and is associated with nerve damage. Nociceptive pain commonly is described as similar to a toothache with descriptors such as stabbing, sharp, or a dull aching sensation; it is often, but not always, associated with acute injury or ongoing trauma to tissue. Drug treatment is most successful when the appropriate class of medication is matched to the specific type of pain.

Nociceptive pain often is successfully treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen. Non-selective COX inhibitors (eg, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac) and COX-2 selective inhibitors (eg, celecoxib) have been associated with cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal disease; acetaminophen is associated with liver dysfunction.9-11 However, the absolute risk for complications in healthy patients is low.12 To minimize risk, use these agents for the shortest duration and at the lowest effective dosage possible.

Neuropathic pain can be addressed with certain antidepressants13—specifically, those that increase serotonin and norepinephrine (eg, tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs] and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs]), or medications that block ion channels (eg, anticonvulsants). TCAs (eg, desipramine, nortriptyline, amitriptyline) are among the best studied and most cost effective medications for treating neuropathic pain,14,15 but they can have sedating and anticholinergic effects, as well as cardiac adverse effects (ie, prolongation of the QTc interval). SNRIs (eg, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran) can be effective and often are better tolerated than TCAs.14

Some newer anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin and pregabalin) have been found to be more effective than placebo for a variety of neuropathic pain conditions.16,17 Although they have few drug-drug interactions, anticonvulsants can cause dizziness, forgetfulness, and sedation. These adverse effects can be minimized by starting at a low dosage and titrating carefully. Because hepatic or renal impairment can affect metabolism or excretion of these drugs, review the prescribing information to determine safe dosing.

Targeted injection of medications to major pain generators (eg, an epidural steroid for radicular neck and back pain; facet injections for facet-related neck and back pain; trigger point injections for myofascial pain; occipital nerve blocks for occipital neuralgia; and botulinum toxin A injections for chronic migraine headache) can be effective in reducing discomfort and increasing function in patients with chronic pain. A detailed discussion of such therapies is beyond the scope of this article, but have been reviewed extensively elsewhere.18,19

Opioids. Although there is little evidence of long-term efficacy with chronic opioid therapy for most patients, a trial of opioids might be warranted for select patients who do not respond to other medications. Because the risk–benefit ratio for chronic opioid therapy is high,20-22 a decision to initiate a trial of a low-dosage opioid should be made only after careful consideration of those risks. It is generally agreed that treatment of chronic pain with low-dosage opioid therapy is more likely to be successful when it is used as an adjuvant to non-opioid modalities (eg, physical reconditioning, injection therapies, spinal cord stimulation, neurobehavioral interventions, non-opioid medications).

The Federation of State Medical Boards has stated that excessive reliance on opioid medications for treating chronic pain is a deviation from best practices.23 To maximize benefit and minimize risk, clinicians should carefully select appropriate patients, establish functional goals, and regularly monitor for efficacy and compliance. Thoroughly document these steps in the patient’s record for later reference.23

After establishing a clinical diagnosis for the cause of the pain, you should determine the risk of opioid abuse or misuse by using any one of the available risk assessment tools (Box). Understand, however, that no single tool has been shown to be more effective than others.

Although patients and some clinicians tend to overvalue the benefits of chronic opioid therapy, many do not fully appreciate the risks (eg, respiratory depression and death), which can be exacerbated if the patient is using other substance that suppress respiration (eg, benzodiazepines, alcohol, and illicit substances). Written informed consent and treatment agreement is highly recommended; components of such a document are listed in Table 3.23

Develop a treatment plan that emphasizes functional goals based on the patient’s physical limitations and that incorporates some type of daily, atraumatic physical activity. This plan should be documented and reviewed regularly to help monitor treatment effectiveness.

After an initial trial of a few weeks, the patient and clinician should meet to review the 5 “A”s (Table 4)24 to determine the success of the opioid regimen. Consulting your state’s prescription drug monitoring program (if one is available), obtaining a random urine drug test, and doing a pill count can provide useful, objective data. If the patient has not made progress but has experienced no adverse effects, then a small dosage increase might be warranted. If any of the 5 “A”s indicates lack of improvement or increased risk, consider stopping opioid therapy and exploring non-opioid options to manage chronic pain.

Referrals to a pain specialist or an addiction specialist, or both, might be needed, depending on the patient’s condition at any given follow-up visit. Such referral decisions, as well as all treatment plans, should be documented clearly in the medical record to prevent any misunderstanding, false accusations, or medicolegal repercussions regarding the rationale for continuing or terminating opioid-based treatment.

Non-pharmaceutical therapy for treating pain

The pain management field has successfully integrated the biopsychosocial model into regular practice. This model advocates the use of multimodal non-drug interventions in conjunction with opioid and non-opioid medications. Such interventions address behavioral, cognitive, sociocultural (psychosocial), lifestyle, and physiological dimensions of pain. A partial list of non-drug interventions is provided in Table 5.

Integration of these interventions within a biopsychosocial framework can assist you in making a comprehensive treatment plan. For example, patients with focal myofascial shoulder and back pain might derive only transient benefit from trigger point injection. However, concurrent referral to a pain psychologist and physical therapist could substantially improve functional outcomes by addressing factors that directly and indirectly influence myofascial pain. Inclusion of cognitive-behavioral therapy (addressing psychosocial and lifestyle dimensions), surface electromyography, psychophysiological interventions/biofeedback (addressing psychosocial, lifestyle, and physiological dimensions), and physical therapy (addressing lifestyle and physiological dimensions) allows the patient to learn coping skills, decrease physiological arousal that can lead to unnecessary tensing of muscles, and strengthen core muscle groups.

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20 Files/2011/Relieving-Pain-in-America-A-Blueprint-for- Transforming-Prevention-Care-Education-Research/ Pain%20Research%202011%20Report%20Brief.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed April 15, 2015.

2. Jensen MP, Moore MR, Bockow TB, et al. Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in persons with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(1):146-160.

3. McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

4. Abrishami A, Khajehdehi A, Chung F. A systematic review of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):423-438.

5. Boynton G, Vahabzadeh A, Hammoud S, et al. Validation of the STOP-BANG questionnaire among patients referred for suspected obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Disord Treat Care. 2013;2(4). doi: 10.4172/2325-9639.1000121.

6. Vana KD, Silva GE, Goldberg R. Predictive abilities of the STOP-Bang and Epworth Sleepiness Scale in identifying sleep clinic patients at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(1):84-94.

7. Chung F, Elsaid H. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea before surgery: why is it important? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22(3):405-411.

8. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821.

9. Forman JP, Rimm EB, Curhan GC. Frequency of analgesic use and risk of hypertension among men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):394-399.

10. Sudano I, Flammer AJ, Périat D, et al. Acetaminophen increases blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1789-1796.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers about oral prescription acetaminophen products to be limited to 325 mg per dosage unit. http://www.fda.gov/ drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/ucm239871. htm. Updated December 11, 2014. Accessed February 23, 2015.

12. Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al; Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769-779.

13. Sullivan MD, Robinson JP. Antidepressant and anticonvulsant medication for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17(2):381-400, vi-vii.

14. Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, et al. Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96(6):399-409.

15. Pilowsky I, Hallett EC, Bassett DL, et al. A controlled study of amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain. Pain. 1982;14(2):169-179.

16. Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150(3):573-581.

17. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

18. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. An update of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in chronic spinal pain. Part II: guidance and recommendations. Pain Physician. 2013;16(suppl 2):S49-S283.

19. Singh V, Trescot A, Nishio I. Injections for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):249-261.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers— United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492.

21. Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659.

22. Chen L, Vo T, Seefeld L, et al. Lack of correlation between opioid dose adjustment and pain score change in a group of chronic pain patients. J Pain. 2013;14(4):384-392.

23. Federation of State Medical Boards. Model policy for the use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of chronic pain. http:// www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/ pain_policy_july2013.pdf. Published July 2013. Accessed December 18, 2015.

24. Passik SD, Weinreb HJ. Managing chronic nonmalignant pain: overcoming obstacles to the use of opioids. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):70-83.

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20 Files/2011/Relieving-Pain-in-America-A-Blueprint-for- Transforming-Prevention-Care-Education-Research/ Pain%20Research%202011%20Report%20Brief.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed April 15, 2015.

2. Jensen MP, Moore MR, Bockow TB, et al. Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in persons with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(1):146-160.

3. McCarron R, Xiong G, Bourgeois J. Lippincott’s primary care psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

4. Abrishami A, Khajehdehi A, Chung F. A systematic review of screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(5):423-438.

5. Boynton G, Vahabzadeh A, Hammoud S, et al. Validation of the STOP-BANG questionnaire among patients referred for suspected obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Disord Treat Care. 2013;2(4). doi: 10.4172/2325-9639.1000121.

6. Vana KD, Silva GE, Goldberg R. Predictive abilities of the STOP-Bang and Epworth Sleepiness Scale in identifying sleep clinic patients at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(1):84-94.

7. Chung F, Elsaid H. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea before surgery: why is it important? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22(3):405-411.

8. Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821.

9. Forman JP, Rimm EB, Curhan GC. Frequency of analgesic use and risk of hypertension among men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):394-399.

10. Sudano I, Flammer AJ, Périat D, et al. Acetaminophen increases blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1789-1796.

11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers about oral prescription acetaminophen products to be limited to 325 mg per dosage unit. http://www.fda.gov/ drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/ucm239871. htm. Updated December 11, 2014. Accessed February 23, 2015.

12. Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al; Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’ (CNT) Collaboration. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769-779.

13. Sullivan MD, Robinson JP. Antidepressant and anticonvulsant medication for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17(2):381-400, vi-vii.

14. Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, et al. Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96(6):399-409.

15. Pilowsky I, Hallett EC, Bassett DL, et al. A controlled study of amitriptyline in the treatment of chronic pain. Pain. 1982;14(2):169-179.

16. Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150(3):573-581.

17. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

18. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. An update of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in chronic spinal pain. Part II: guidance and recommendations. Pain Physician. 2013;16(suppl 2):S49-S283.

19. Singh V, Trescot A, Nishio I. Injections for chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26(2):249-261.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers— United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492.

21. Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659.

22. Chen L, Vo T, Seefeld L, et al. Lack of correlation between opioid dose adjustment and pain score change in a group of chronic pain patients. J Pain. 2013;14(4):384-392.

23. Federation of State Medical Boards. Model policy for the use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of chronic pain. http:// www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/ pain_policy_july2013.pdf. Published July 2013. Accessed December 18, 2015.

24. Passik SD, Weinreb HJ. Managing chronic nonmalignant pain: overcoming obstacles to the use of opioids. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):70-83.