User login

What is the diagnostic approach to a 1-year-old with chronic cough?

Very few studies examine the evaluation of chronic cough among young children. Based on expert opinion, investigation of chronic cough should begin with a detailed history, physical examination, and chest radiograph (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, expert opinion).1

Before pursuing additional studies, remove potential irritants from the patient’s environment. Work-up for persisting cough should consider congenital anomalies and then be directed toward common causes of chronic cough like those seen in older children and adults, including postnasal drip syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and asthma (SOR: C).

Evidence summary

The data on which expert opinion is based comes from case series of chronic cough in adults and older children in the setting of a specialty clinic.2,3 A detailed history should attend to the neonatal course, feeding concerns, sleep issues, potential for foreign-body aspiration, medications, infectious exposures, family history of atopy or asthma, and exposures to environmental irritants such as tobacco smoke.1 A dry, barking, or brassy cough in infants suggests large airway obstruction; in older children, it is likely psychogenic. A wet, productive cough is associated with an infectious cause. A cough associated with throat clearing suggests GERD or postnasal drip syndrome.3

Chest radiography, although universally recommended, was only abnormal for 4% of older patients (age 6 years through adult) from one series.2 Chest radiography may be most helpful for infants at increased risk for foreign-body aspiration. Cough from passive smoke exposure should improve with removal of exposure. There is no information on how long to wait for improvement.1

If the initial evaluation is not revealing, further investigation should focus on congenital anomalies, asthma, postnasal drip, and GERD. Aberrant innominate artery and asthma were the most frequent diagnoses among children aged <18 months old referred for otolaryngology consultation.3 Because pulmonary function testing is not practical for infants, a trial of aggressive therapy in combination with a “cough diary” kept by the parents may be used to diagnose asthma.1 Sinus computed tomography films are not routinely recommended to evaluate for postnasal drip, as sinusitis among children does not correlate well with postnasal drip.1 GERD may present with chronic cough; however, there is insufficient evidence for a uniform approach to diagnosis of cough associated with reflux.4

After evaluating infants for common causes of chronic cough (or if suggested by the history or physical), less common causes should be explored (Table). Consider a sweat chloride test first, followed by tuberculin testing. More than one cause for chronic cough was found 23% of the time in adults.2 Multiple causes of cough may be less common among infants, though no data confirm this.

Though it includes a mixture of adults and older children, a case series from pulmonary specialists finds pulmonary function tests with methacholine challenge the most helpful test.2 Case series from otolaryngology find endoscopy to be the most helpful, but it also includes a mix of older patients.3 Therefore, it seems likely that primary care physicians already appropriately refer patients to the correct specialists for evaluation. The optimal time to refer patients is unknown. We identified no reports from primary care settings. The question is an appropriate topic for primary care research.

TABLE

Causes of chronic cough among children with normal chest radiograph

| Category | Diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Asthma | Cough-variant asthma, hyperactive airways after infection |

| Infectious | Chronic sinusitis, otitis media with effusion, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, chronic Waldeyer’s ring infection, pertussis, parapertussis, adenovirus, tuberculosis |

Congenital

| Aberrant innominate artery, vascular rings, bronchogenic cyst, esophageal duplication, subglottic stenosis, tracheomalacia, tracheal and bronchial stenosis Gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal incoordination, tracheoesophageal fistula, cleft larynx, vocal cord paralysis, pharyngeal incoordination, achalasia, cricopharyngeal achalasia Tracheobronchial tree abnormalities, cystic fibrosis, immotile cilia syndrome, congenital heart disease, bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| Psychogenic | Psychogenic cough |

| Traumatic | Foreign bodies of bronchus, trachea, larynx, nose, external auditory canal |

| Environmental | Tobacco exposure, low humidity, overheating, allergens, industrial pollutants |

| Otologic | Cerumen, foreign body, infection, neoplasm, hair |

| Neoplastic | Larynx: Subglottic hemangioma, papillomatosis Tracheobronchial tree: Papillomatosis, bronchial adenoma Mediastinal tumor causing tracheobronchial compression |

| Cardiovascular | Rheumatic fever, congestive heart failure, mitral stenosis |

| Adapted from: Holinger 1986.3 | |

Recommendations from others

A guideline from Finaldn suggests referral for investigations of asthma, allergy, and GERD. Infectious diseases, the presence of foreign bodies, and psychogenic causes should also be considered.5

Inquire about exposure to irritants, feeding habits, infection, family history of asthma

Phong Luu, MD

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex

A comprehensive detailed history is the first important diagnostic step in the approach to a chronic cough in a 1-year old. The primary care provider should inquire about the infant’s exposure to environmental irritants such as tobacco smoke, their feeding habits, possible foreign-body aspiration, infectious exposure, and the family history of asthma. Environmental pollution in areas such as where I practice (Houston, Texas) can be a significant factor in evaluating infant with chronic cough. A chest radiograph should be considered after a thorough physical examination.

After an initial evaluation, further investigation should focus on the common causes of chronic cough such as postnasal drip, asthma, and GERD. Because of the high frequency of postnasal drip, the patient can be empirically started on antihistamine/decongestion combination. The primary care provider may consider an empirical treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease if suggested by the history and physical examination. If no improvement is seen after several weeks, the patient should be referred to the appropriate specialist for evaluation of asthma, congenital anomalies, or other less common cause of chronic cough.

1. Irwin RS, Boulet LP, Cloutier MM, et al. Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom. A consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest 1998;114(2 Suppl):133S-181S.

2. Irwin RS, Curley FJ, French CL. Chronic cough. The spectrum and frequency of causes, key components of diagnostic evaluation, and outcome of specific therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;141:640-647.

3. Holinger LD. Chronic cough in infants and children. Laryngoscope 1986;96:316-322.

4. Rudolph CD, Mazur LJ, Liptak GS, et al. Guidelines for evaluation and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;32 Suppl 2:S1-31.

5. Finnish Medical Society Duodecim. Prolonged cough in children. Helsinki, Finland: Duodecim Medical Publications; 2001. Available at: www.guideline.gov/guidelines/FTNGC-2602.html. Accessed on November 11, 2004.

Very few studies examine the evaluation of chronic cough among young children. Based on expert opinion, investigation of chronic cough should begin with a detailed history, physical examination, and chest radiograph (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, expert opinion).1

Before pursuing additional studies, remove potential irritants from the patient’s environment. Work-up for persisting cough should consider congenital anomalies and then be directed toward common causes of chronic cough like those seen in older children and adults, including postnasal drip syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and asthma (SOR: C).

Evidence summary

The data on which expert opinion is based comes from case series of chronic cough in adults and older children in the setting of a specialty clinic.2,3 A detailed history should attend to the neonatal course, feeding concerns, sleep issues, potential for foreign-body aspiration, medications, infectious exposures, family history of atopy or asthma, and exposures to environmental irritants such as tobacco smoke.1 A dry, barking, or brassy cough in infants suggests large airway obstruction; in older children, it is likely psychogenic. A wet, productive cough is associated with an infectious cause. A cough associated with throat clearing suggests GERD or postnasal drip syndrome.3

Chest radiography, although universally recommended, was only abnormal for 4% of older patients (age 6 years through adult) from one series.2 Chest radiography may be most helpful for infants at increased risk for foreign-body aspiration. Cough from passive smoke exposure should improve with removal of exposure. There is no information on how long to wait for improvement.1

If the initial evaluation is not revealing, further investigation should focus on congenital anomalies, asthma, postnasal drip, and GERD. Aberrant innominate artery and asthma were the most frequent diagnoses among children aged <18 months old referred for otolaryngology consultation.3 Because pulmonary function testing is not practical for infants, a trial of aggressive therapy in combination with a “cough diary” kept by the parents may be used to diagnose asthma.1 Sinus computed tomography films are not routinely recommended to evaluate for postnasal drip, as sinusitis among children does not correlate well with postnasal drip.1 GERD may present with chronic cough; however, there is insufficient evidence for a uniform approach to diagnosis of cough associated with reflux.4

After evaluating infants for common causes of chronic cough (or if suggested by the history or physical), less common causes should be explored (Table). Consider a sweat chloride test first, followed by tuberculin testing. More than one cause for chronic cough was found 23% of the time in adults.2 Multiple causes of cough may be less common among infants, though no data confirm this.

Though it includes a mixture of adults and older children, a case series from pulmonary specialists finds pulmonary function tests with methacholine challenge the most helpful test.2 Case series from otolaryngology find endoscopy to be the most helpful, but it also includes a mix of older patients.3 Therefore, it seems likely that primary care physicians already appropriately refer patients to the correct specialists for evaluation. The optimal time to refer patients is unknown. We identified no reports from primary care settings. The question is an appropriate topic for primary care research.

TABLE

Causes of chronic cough among children with normal chest radiograph

| Category | Diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Asthma | Cough-variant asthma, hyperactive airways after infection |

| Infectious | Chronic sinusitis, otitis media with effusion, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, chronic Waldeyer’s ring infection, pertussis, parapertussis, adenovirus, tuberculosis |

Congenital

| Aberrant innominate artery, vascular rings, bronchogenic cyst, esophageal duplication, subglottic stenosis, tracheomalacia, tracheal and bronchial stenosis Gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal incoordination, tracheoesophageal fistula, cleft larynx, vocal cord paralysis, pharyngeal incoordination, achalasia, cricopharyngeal achalasia Tracheobronchial tree abnormalities, cystic fibrosis, immotile cilia syndrome, congenital heart disease, bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| Psychogenic | Psychogenic cough |

| Traumatic | Foreign bodies of bronchus, trachea, larynx, nose, external auditory canal |

| Environmental | Tobacco exposure, low humidity, overheating, allergens, industrial pollutants |

| Otologic | Cerumen, foreign body, infection, neoplasm, hair |

| Neoplastic | Larynx: Subglottic hemangioma, papillomatosis Tracheobronchial tree: Papillomatosis, bronchial adenoma Mediastinal tumor causing tracheobronchial compression |

| Cardiovascular | Rheumatic fever, congestive heart failure, mitral stenosis |

| Adapted from: Holinger 1986.3 | |

Recommendations from others

A guideline from Finaldn suggests referral for investigations of asthma, allergy, and GERD. Infectious diseases, the presence of foreign bodies, and psychogenic causes should also be considered.5

Inquire about exposure to irritants, feeding habits, infection, family history of asthma

Phong Luu, MD

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex

A comprehensive detailed history is the first important diagnostic step in the approach to a chronic cough in a 1-year old. The primary care provider should inquire about the infant’s exposure to environmental irritants such as tobacco smoke, their feeding habits, possible foreign-body aspiration, infectious exposure, and the family history of asthma. Environmental pollution in areas such as where I practice (Houston, Texas) can be a significant factor in evaluating infant with chronic cough. A chest radiograph should be considered after a thorough physical examination.

After an initial evaluation, further investigation should focus on the common causes of chronic cough such as postnasal drip, asthma, and GERD. Because of the high frequency of postnasal drip, the patient can be empirically started on antihistamine/decongestion combination. The primary care provider may consider an empirical treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease if suggested by the history and physical examination. If no improvement is seen after several weeks, the patient should be referred to the appropriate specialist for evaluation of asthma, congenital anomalies, or other less common cause of chronic cough.

Very few studies examine the evaluation of chronic cough among young children. Based on expert opinion, investigation of chronic cough should begin with a detailed history, physical examination, and chest radiograph (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, expert opinion).1

Before pursuing additional studies, remove potential irritants from the patient’s environment. Work-up for persisting cough should consider congenital anomalies and then be directed toward common causes of chronic cough like those seen in older children and adults, including postnasal drip syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and asthma (SOR: C).

Evidence summary

The data on which expert opinion is based comes from case series of chronic cough in adults and older children in the setting of a specialty clinic.2,3 A detailed history should attend to the neonatal course, feeding concerns, sleep issues, potential for foreign-body aspiration, medications, infectious exposures, family history of atopy or asthma, and exposures to environmental irritants such as tobacco smoke.1 A dry, barking, or brassy cough in infants suggests large airway obstruction; in older children, it is likely psychogenic. A wet, productive cough is associated with an infectious cause. A cough associated with throat clearing suggests GERD or postnasal drip syndrome.3

Chest radiography, although universally recommended, was only abnormal for 4% of older patients (age 6 years through adult) from one series.2 Chest radiography may be most helpful for infants at increased risk for foreign-body aspiration. Cough from passive smoke exposure should improve with removal of exposure. There is no information on how long to wait for improvement.1

If the initial evaluation is not revealing, further investigation should focus on congenital anomalies, asthma, postnasal drip, and GERD. Aberrant innominate artery and asthma were the most frequent diagnoses among children aged <18 months old referred for otolaryngology consultation.3 Because pulmonary function testing is not practical for infants, a trial of aggressive therapy in combination with a “cough diary” kept by the parents may be used to diagnose asthma.1 Sinus computed tomography films are not routinely recommended to evaluate for postnasal drip, as sinusitis among children does not correlate well with postnasal drip.1 GERD may present with chronic cough; however, there is insufficient evidence for a uniform approach to diagnosis of cough associated with reflux.4

After evaluating infants for common causes of chronic cough (or if suggested by the history or physical), less common causes should be explored (Table). Consider a sweat chloride test first, followed by tuberculin testing. More than one cause for chronic cough was found 23% of the time in adults.2 Multiple causes of cough may be less common among infants, though no data confirm this.

Though it includes a mixture of adults and older children, a case series from pulmonary specialists finds pulmonary function tests with methacholine challenge the most helpful test.2 Case series from otolaryngology find endoscopy to be the most helpful, but it also includes a mix of older patients.3 Therefore, it seems likely that primary care physicians already appropriately refer patients to the correct specialists for evaluation. The optimal time to refer patients is unknown. We identified no reports from primary care settings. The question is an appropriate topic for primary care research.

TABLE

Causes of chronic cough among children with normal chest radiograph

| Category | Diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Asthma | Cough-variant asthma, hyperactive airways after infection |

| Infectious | Chronic sinusitis, otitis media with effusion, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, chronic Waldeyer’s ring infection, pertussis, parapertussis, adenovirus, tuberculosis |

Congenital

| Aberrant innominate artery, vascular rings, bronchogenic cyst, esophageal duplication, subglottic stenosis, tracheomalacia, tracheal and bronchial stenosis Gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal incoordination, tracheoesophageal fistula, cleft larynx, vocal cord paralysis, pharyngeal incoordination, achalasia, cricopharyngeal achalasia Tracheobronchial tree abnormalities, cystic fibrosis, immotile cilia syndrome, congenital heart disease, bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| Psychogenic | Psychogenic cough |

| Traumatic | Foreign bodies of bronchus, trachea, larynx, nose, external auditory canal |

| Environmental | Tobacco exposure, low humidity, overheating, allergens, industrial pollutants |

| Otologic | Cerumen, foreign body, infection, neoplasm, hair |

| Neoplastic | Larynx: Subglottic hemangioma, papillomatosis Tracheobronchial tree: Papillomatosis, bronchial adenoma Mediastinal tumor causing tracheobronchial compression |

| Cardiovascular | Rheumatic fever, congestive heart failure, mitral stenosis |

| Adapted from: Holinger 1986.3 | |

Recommendations from others

A guideline from Finaldn suggests referral for investigations of asthma, allergy, and GERD. Infectious diseases, the presence of foreign bodies, and psychogenic causes should also be considered.5

Inquire about exposure to irritants, feeding habits, infection, family history of asthma

Phong Luu, MD

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex

A comprehensive detailed history is the first important diagnostic step in the approach to a chronic cough in a 1-year old. The primary care provider should inquire about the infant’s exposure to environmental irritants such as tobacco smoke, their feeding habits, possible foreign-body aspiration, infectious exposure, and the family history of asthma. Environmental pollution in areas such as where I practice (Houston, Texas) can be a significant factor in evaluating infant with chronic cough. A chest radiograph should be considered after a thorough physical examination.

After an initial evaluation, further investigation should focus on the common causes of chronic cough such as postnasal drip, asthma, and GERD. Because of the high frequency of postnasal drip, the patient can be empirically started on antihistamine/decongestion combination. The primary care provider may consider an empirical treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease if suggested by the history and physical examination. If no improvement is seen after several weeks, the patient should be referred to the appropriate specialist for evaluation of asthma, congenital anomalies, or other less common cause of chronic cough.

1. Irwin RS, Boulet LP, Cloutier MM, et al. Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom. A consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest 1998;114(2 Suppl):133S-181S.

2. Irwin RS, Curley FJ, French CL. Chronic cough. The spectrum and frequency of causes, key components of diagnostic evaluation, and outcome of specific therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;141:640-647.

3. Holinger LD. Chronic cough in infants and children. Laryngoscope 1986;96:316-322.

4. Rudolph CD, Mazur LJ, Liptak GS, et al. Guidelines for evaluation and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;32 Suppl 2:S1-31.

5. Finnish Medical Society Duodecim. Prolonged cough in children. Helsinki, Finland: Duodecim Medical Publications; 2001. Available at: www.guideline.gov/guidelines/FTNGC-2602.html. Accessed on November 11, 2004.

1. Irwin RS, Boulet LP, Cloutier MM, et al. Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom. A consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest 1998;114(2 Suppl):133S-181S.

2. Irwin RS, Curley FJ, French CL. Chronic cough. The spectrum and frequency of causes, key components of diagnostic evaluation, and outcome of specific therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;141:640-647.

3. Holinger LD. Chronic cough in infants and children. Laryngoscope 1986;96:316-322.

4. Rudolph CD, Mazur LJ, Liptak GS, et al. Guidelines for evaluation and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;32 Suppl 2:S1-31.

5. Finnish Medical Society Duodecim. Prolonged cough in children. Helsinki, Finland: Duodecim Medical Publications; 2001. Available at: www.guideline.gov/guidelines/FTNGC-2602.html. Accessed on November 11, 2004.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

When should patients with mitral valve prolapse get endocarditis prophylaxis?

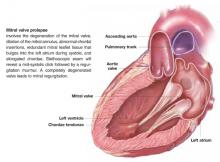

Patients with suspected mitral valve prolapse (MVP) ( Figure 1 ) should undergo echocardiography before any procedure that may place them at risk for bacteremia. Patients with MVP and documented absence of mitral regurgitation or valvular thickening likely do not need antibiotic prophylaxis against subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE). Patients with MVP with documented mitral regurgitation, valvular thickening, or an unknown degree of valvular dysfunction may benefit from antibiotics during procedures that often lead to bacteremia (strength of recommendation: C).1

FIGURE 1 Mitral valve prolapse

Evidence summary

Only disease-oriented evidence and expert opinion address prevention for endocarditis. A randomized trial would require an estimated 6000 patients to demonstrate benefit.2

Endocarditis occurs in MVP at a rate of 0.1 cases/100 patient-years.3 However, MVP is the most common predisposing/precipitating cause of native valve endocarditis.4,5 In animal models, antibiotics prevent endocarditis following experimental bacteremia. The antibiotic can be administered either just before or up to 2 hours after the bacteremic event.2 It is worth noting that most bacteremia is not associated with medical procedures. Since endocarditis is often fatal, recommendations have been developed based on these animal models. Estimates of effectiveness of prophylaxis from case-control studies in humans (not limited to patients with MVP) estimate effectiveness from 49% to 91%.2

For patients with MVP who do not have evidence of mitral regurgitation on physical examination or echocardiography, the risk of morbidity may be greater from antibiotic therapy than the risk of endocarditis. Prophylaxis for these patients is not recommended. Patients with MVP associated with regurgitation are at moderate risk and may benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis.

Recommendations from others

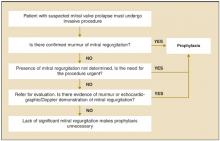

The American Heart Association has published recommendations in 1985,6 1990,7 and 1997.1 The 1997 recommendations are summarized in Figure 2 . The Swiss Working Group for Endocarditis Prophylaxis published similar recommendations in 2000.8 Recommended prophylactic regimens appear in Table 1. Table 2 shows a modified list of procedures for which prophylaxis is recommended.

FIGURE 2

Determining the need for antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with mitral valve prolapse

TABLE 1

Recommended prophylactic regimens for mitral valve prolaspe

| Situation | Medication | Dosage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dental, oral, respiratory, esophageal procedures | 1 hour before procedure | ||

| Standard prophylaxis | Amoxicillin | Adult:2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg |

| Allergy to penicillin | Clindamycin | Adult: 600 mg | Child: 20 mg/kg |

| Cephalexin | Adult: 2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg | |

| Azithromycin | Adult: 500 mg | Child: 15 mg/kg | |

| Genitourinary or non-esophageal gastrointestinal procedures | |||

| Moderate-risk patients | Amoxicillin | Adult: 2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg |

| 1 hour before procedure | |||

| Moderate-risk patients allergic to penicillin | Vancomycin | Adult: 1 g IV | Child: 20 mg/kg IV |

| Administer over 1-2 hrs; complete 30 minutes before procedure | |||

| High-risk patients | Add gentamicin to amoxicillin or vancomycin | 1.5 mg/kg (up to 120 mg) IV to be completed 30 minutes before procedure. If not allergic to penicillin, give penicillin give penicillin, give amoxicillin 1 g 6 hours after | |

| Modified from Dajani 1997.1 | |||

TABLE 2

Procedures for which endocarditis prophylaxis is, or is not, recommended

| Endocarditis prophylaxis recommended |

| Respiratory tract |

| Tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy |

| Surgical operations that involve respiratory mucosa |

| Bronchoscopy with a rigid bronchoscope |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

| Sclerotherapy for esophageal varices |

| Esophageal stricture dilation |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography with biliary obstruction |

| Biliary tract surgery |

| Surgical operations that involve intestinal mucosa |

| Genitourinary tract |

| Prostatic surgery |

| Cystoscopy |

| Urethral dilation |

| Endocarditis prophylaxis not recommended |

| Respiratory tract |

| Endotracheal intubation |

| Flexible bronchoscopy, with or without biopsy |

| Tympanostomy tube insertion |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

| Endoscopy with or without gastrointestinal biopsy |

| Genitourinary tract |

| Circumcision |

| Vaginal hysterectomy |

| Vaginal delivery |

| Cesarean section |

| In uninfected tissue |

| Incision or biopsy of surgically scrubbed skin |

| Urethral catheterization |

| Uterine dilatation and curettage |

| Therapeutic abortion |

| Sterilization procedures |

| Insertion or removal of intrauterine devices |

| Cardiac |

| Transesophageal echocardiography |

| Cardiac catheterization, including balloon angioplasty and coronary stents |

| Implanted cardiac pacemakers, implanted defibrillators |

| Modified from Dajani et al, 1997.1 |

Guidelines assist decision-making regarding who needs SBE prophylaxis

David M. Bercaw, MD

Christiana Care Health Systems, Wilmington, Del

It is unfortunate, but not surprising, that the evidence for SBE prophylaxis for patients with MVP is disease-oriented evidence and expert opinion. Too often, the easy thing to do in a busy practice is not necessarily in the best interest of either the patient or the public. However—despite the low incidence of SBE—the high mortality of the disease and community standard of care often drive clinicians to write that prescription for antibiotics.

With the improved resolution and sensitivity of newer generations of echocardiograms, clinicians often face the dilemma of the patient with MVP and “trivial” or “mnimal” mitral regurgitation. Unfortunately, no guidelines assist us in our decision-making regarding these patients. Another consideration for the clinician is the American Heart Association’s recommendation for SBE prophylaxis for patients with MVP and thickened leaflets, regardless of whether there is associated mitral valve regurgitation.

One significant change that should lessen the frequency of unnecessary antibiotic prescribing was published recently. The echocardiographic criteria for diagnosing MVP were changed in the 2003 updated guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American Society of Echocardiography. Valve prolapse of 2 mm or more above the mitral annulus is required for diagnosis.10 This change has effectively lowered the prevalence of MVP from 4% to 8% of the general population down to 2% to 3%.

1. Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA 1997;277:1794-1801.

2. Durack DT. Prevention of infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med 1995;332:38-44.

3. Zuppiroli A, Rinaldi M, Kramer-Fox R, Favilli S, Roman MJ, Devereux RB. Natural history of mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:1028-1032.

4. Awadallah SM, Kavey RE, Byrum CJ, Smith FC, Kveselis DA, Blackman MS. The changing pattern of infective endocarditis in childhood. Am J Cardiol 1991;68:90-94.

5. McKinsey DS, Ratts TE, Bisno AL. Underlying cardiac lesions in adults with infective endocarditis. The changing spectrum. Am J Med 1987;82:681-688.

6. Shulman ST, Amren DP, Bisno AL, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis: A statement for health professionals by the Committee on Rheumatic Fever and Bacterial Endocarditis of the Council on Cardiovascular Diseases in the Young of the American Heart Association. Am J Dis Child 1985;139:232-235.

7. Dajani AS, Bisno AL, Chung KJ, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA 1990;264:2919-2922.

8. Moreillon P. Endocarditis prophylaxis revisited: experimental evidence of efficacy and new Swiss recommendations. Swiss Working Group for Endocarditis Prophylaxis. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 2000;130:1013-1026.

9. Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:954-970.

Patients with suspected mitral valve prolapse (MVP) ( Figure 1 ) should undergo echocardiography before any procedure that may place them at risk for bacteremia. Patients with MVP and documented absence of mitral regurgitation or valvular thickening likely do not need antibiotic prophylaxis against subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE). Patients with MVP with documented mitral regurgitation, valvular thickening, or an unknown degree of valvular dysfunction may benefit from antibiotics during procedures that often lead to bacteremia (strength of recommendation: C).1

FIGURE 1 Mitral valve prolapse

Evidence summary

Only disease-oriented evidence and expert opinion address prevention for endocarditis. A randomized trial would require an estimated 6000 patients to demonstrate benefit.2

Endocarditis occurs in MVP at a rate of 0.1 cases/100 patient-years.3 However, MVP is the most common predisposing/precipitating cause of native valve endocarditis.4,5 In animal models, antibiotics prevent endocarditis following experimental bacteremia. The antibiotic can be administered either just before or up to 2 hours after the bacteremic event.2 It is worth noting that most bacteremia is not associated with medical procedures. Since endocarditis is often fatal, recommendations have been developed based on these animal models. Estimates of effectiveness of prophylaxis from case-control studies in humans (not limited to patients with MVP) estimate effectiveness from 49% to 91%.2

For patients with MVP who do not have evidence of mitral regurgitation on physical examination or echocardiography, the risk of morbidity may be greater from antibiotic therapy than the risk of endocarditis. Prophylaxis for these patients is not recommended. Patients with MVP associated with regurgitation are at moderate risk and may benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis.

Recommendations from others

The American Heart Association has published recommendations in 1985,6 1990,7 and 1997.1 The 1997 recommendations are summarized in Figure 2 . The Swiss Working Group for Endocarditis Prophylaxis published similar recommendations in 2000.8 Recommended prophylactic regimens appear in Table 1. Table 2 shows a modified list of procedures for which prophylaxis is recommended.

FIGURE 2

Determining the need for antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with mitral valve prolapse

TABLE 1

Recommended prophylactic regimens for mitral valve prolaspe

| Situation | Medication | Dosage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dental, oral, respiratory, esophageal procedures | 1 hour before procedure | ||

| Standard prophylaxis | Amoxicillin | Adult:2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg |

| Allergy to penicillin | Clindamycin | Adult: 600 mg | Child: 20 mg/kg |

| Cephalexin | Adult: 2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg | |

| Azithromycin | Adult: 500 mg | Child: 15 mg/kg | |

| Genitourinary or non-esophageal gastrointestinal procedures | |||

| Moderate-risk patients | Amoxicillin | Adult: 2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg |

| 1 hour before procedure | |||

| Moderate-risk patients allergic to penicillin | Vancomycin | Adult: 1 g IV | Child: 20 mg/kg IV |

| Administer over 1-2 hrs; complete 30 minutes before procedure | |||

| High-risk patients | Add gentamicin to amoxicillin or vancomycin | 1.5 mg/kg (up to 120 mg) IV to be completed 30 minutes before procedure. If not allergic to penicillin, give penicillin give penicillin, give amoxicillin 1 g 6 hours after | |

| Modified from Dajani 1997.1 | |||

TABLE 2

Procedures for which endocarditis prophylaxis is, or is not, recommended

| Endocarditis prophylaxis recommended |

| Respiratory tract |

| Tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy |

| Surgical operations that involve respiratory mucosa |

| Bronchoscopy with a rigid bronchoscope |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

| Sclerotherapy for esophageal varices |

| Esophageal stricture dilation |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography with biliary obstruction |

| Biliary tract surgery |

| Surgical operations that involve intestinal mucosa |

| Genitourinary tract |

| Prostatic surgery |

| Cystoscopy |

| Urethral dilation |

| Endocarditis prophylaxis not recommended |

| Respiratory tract |

| Endotracheal intubation |

| Flexible bronchoscopy, with or without biopsy |

| Tympanostomy tube insertion |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

| Endoscopy with or without gastrointestinal biopsy |

| Genitourinary tract |

| Circumcision |

| Vaginal hysterectomy |

| Vaginal delivery |

| Cesarean section |

| In uninfected tissue |

| Incision or biopsy of surgically scrubbed skin |

| Urethral catheterization |

| Uterine dilatation and curettage |

| Therapeutic abortion |

| Sterilization procedures |

| Insertion or removal of intrauterine devices |

| Cardiac |

| Transesophageal echocardiography |

| Cardiac catheterization, including balloon angioplasty and coronary stents |

| Implanted cardiac pacemakers, implanted defibrillators |

| Modified from Dajani et al, 1997.1 |

Guidelines assist decision-making regarding who needs SBE prophylaxis

David M. Bercaw, MD

Christiana Care Health Systems, Wilmington, Del

It is unfortunate, but not surprising, that the evidence for SBE prophylaxis for patients with MVP is disease-oriented evidence and expert opinion. Too often, the easy thing to do in a busy practice is not necessarily in the best interest of either the patient or the public. However—despite the low incidence of SBE—the high mortality of the disease and community standard of care often drive clinicians to write that prescription for antibiotics.

With the improved resolution and sensitivity of newer generations of echocardiograms, clinicians often face the dilemma of the patient with MVP and “trivial” or “mnimal” mitral regurgitation. Unfortunately, no guidelines assist us in our decision-making regarding these patients. Another consideration for the clinician is the American Heart Association’s recommendation for SBE prophylaxis for patients with MVP and thickened leaflets, regardless of whether there is associated mitral valve regurgitation.

One significant change that should lessen the frequency of unnecessary antibiotic prescribing was published recently. The echocardiographic criteria for diagnosing MVP were changed in the 2003 updated guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American Society of Echocardiography. Valve prolapse of 2 mm or more above the mitral annulus is required for diagnosis.10 This change has effectively lowered the prevalence of MVP from 4% to 8% of the general population down to 2% to 3%.

Patients with suspected mitral valve prolapse (MVP) ( Figure 1 ) should undergo echocardiography before any procedure that may place them at risk for bacteremia. Patients with MVP and documented absence of mitral regurgitation or valvular thickening likely do not need antibiotic prophylaxis against subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE). Patients with MVP with documented mitral regurgitation, valvular thickening, or an unknown degree of valvular dysfunction may benefit from antibiotics during procedures that often lead to bacteremia (strength of recommendation: C).1

FIGURE 1 Mitral valve prolapse

Evidence summary

Only disease-oriented evidence and expert opinion address prevention for endocarditis. A randomized trial would require an estimated 6000 patients to demonstrate benefit.2

Endocarditis occurs in MVP at a rate of 0.1 cases/100 patient-years.3 However, MVP is the most common predisposing/precipitating cause of native valve endocarditis.4,5 In animal models, antibiotics prevent endocarditis following experimental bacteremia. The antibiotic can be administered either just before or up to 2 hours after the bacteremic event.2 It is worth noting that most bacteremia is not associated with medical procedures. Since endocarditis is often fatal, recommendations have been developed based on these animal models. Estimates of effectiveness of prophylaxis from case-control studies in humans (not limited to patients with MVP) estimate effectiveness from 49% to 91%.2

For patients with MVP who do not have evidence of mitral regurgitation on physical examination or echocardiography, the risk of morbidity may be greater from antibiotic therapy than the risk of endocarditis. Prophylaxis for these patients is not recommended. Patients with MVP associated with regurgitation are at moderate risk and may benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis.

Recommendations from others

The American Heart Association has published recommendations in 1985,6 1990,7 and 1997.1 The 1997 recommendations are summarized in Figure 2 . The Swiss Working Group for Endocarditis Prophylaxis published similar recommendations in 2000.8 Recommended prophylactic regimens appear in Table 1. Table 2 shows a modified list of procedures for which prophylaxis is recommended.

FIGURE 2

Determining the need for antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with mitral valve prolapse

TABLE 1

Recommended prophylactic regimens for mitral valve prolaspe

| Situation | Medication | Dosage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dental, oral, respiratory, esophageal procedures | 1 hour before procedure | ||

| Standard prophylaxis | Amoxicillin | Adult:2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg |

| Allergy to penicillin | Clindamycin | Adult: 600 mg | Child: 20 mg/kg |

| Cephalexin | Adult: 2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg | |

| Azithromycin | Adult: 500 mg | Child: 15 mg/kg | |

| Genitourinary or non-esophageal gastrointestinal procedures | |||

| Moderate-risk patients | Amoxicillin | Adult: 2 g | Child: 50 mg/kg |

| 1 hour before procedure | |||

| Moderate-risk patients allergic to penicillin | Vancomycin | Adult: 1 g IV | Child: 20 mg/kg IV |

| Administer over 1-2 hrs; complete 30 minutes before procedure | |||

| High-risk patients | Add gentamicin to amoxicillin or vancomycin | 1.5 mg/kg (up to 120 mg) IV to be completed 30 minutes before procedure. If not allergic to penicillin, give penicillin give penicillin, give amoxicillin 1 g 6 hours after | |

| Modified from Dajani 1997.1 | |||

TABLE 2

Procedures for which endocarditis prophylaxis is, or is not, recommended

| Endocarditis prophylaxis recommended |

| Respiratory tract |

| Tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy |

| Surgical operations that involve respiratory mucosa |

| Bronchoscopy with a rigid bronchoscope |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

| Sclerotherapy for esophageal varices |

| Esophageal stricture dilation |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography with biliary obstruction |

| Biliary tract surgery |

| Surgical operations that involve intestinal mucosa |

| Genitourinary tract |

| Prostatic surgery |

| Cystoscopy |

| Urethral dilation |

| Endocarditis prophylaxis not recommended |

| Respiratory tract |

| Endotracheal intubation |

| Flexible bronchoscopy, with or without biopsy |

| Tympanostomy tube insertion |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

| Endoscopy with or without gastrointestinal biopsy |

| Genitourinary tract |

| Circumcision |

| Vaginal hysterectomy |

| Vaginal delivery |

| Cesarean section |

| In uninfected tissue |

| Incision or biopsy of surgically scrubbed skin |

| Urethral catheterization |

| Uterine dilatation and curettage |

| Therapeutic abortion |

| Sterilization procedures |

| Insertion or removal of intrauterine devices |

| Cardiac |

| Transesophageal echocardiography |

| Cardiac catheterization, including balloon angioplasty and coronary stents |

| Implanted cardiac pacemakers, implanted defibrillators |

| Modified from Dajani et al, 1997.1 |

Guidelines assist decision-making regarding who needs SBE prophylaxis

David M. Bercaw, MD

Christiana Care Health Systems, Wilmington, Del

It is unfortunate, but not surprising, that the evidence for SBE prophylaxis for patients with MVP is disease-oriented evidence and expert opinion. Too often, the easy thing to do in a busy practice is not necessarily in the best interest of either the patient or the public. However—despite the low incidence of SBE—the high mortality of the disease and community standard of care often drive clinicians to write that prescription for antibiotics.

With the improved resolution and sensitivity of newer generations of echocardiograms, clinicians often face the dilemma of the patient with MVP and “trivial” or “mnimal” mitral regurgitation. Unfortunately, no guidelines assist us in our decision-making regarding these patients. Another consideration for the clinician is the American Heart Association’s recommendation for SBE prophylaxis for patients with MVP and thickened leaflets, regardless of whether there is associated mitral valve regurgitation.

One significant change that should lessen the frequency of unnecessary antibiotic prescribing was published recently. The echocardiographic criteria for diagnosing MVP were changed in the 2003 updated guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American Society of Echocardiography. Valve prolapse of 2 mm or more above the mitral annulus is required for diagnosis.10 This change has effectively lowered the prevalence of MVP from 4% to 8% of the general population down to 2% to 3%.

1. Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA 1997;277:1794-1801.

2. Durack DT. Prevention of infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med 1995;332:38-44.

3. Zuppiroli A, Rinaldi M, Kramer-Fox R, Favilli S, Roman MJ, Devereux RB. Natural history of mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:1028-1032.

4. Awadallah SM, Kavey RE, Byrum CJ, Smith FC, Kveselis DA, Blackman MS. The changing pattern of infective endocarditis in childhood. Am J Cardiol 1991;68:90-94.

5. McKinsey DS, Ratts TE, Bisno AL. Underlying cardiac lesions in adults with infective endocarditis. The changing spectrum. Am J Med 1987;82:681-688.

6. Shulman ST, Amren DP, Bisno AL, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis: A statement for health professionals by the Committee on Rheumatic Fever and Bacterial Endocarditis of the Council on Cardiovascular Diseases in the Young of the American Heart Association. Am J Dis Child 1985;139:232-235.

7. Dajani AS, Bisno AL, Chung KJ, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA 1990;264:2919-2922.

8. Moreillon P. Endocarditis prophylaxis revisited: experimental evidence of efficacy and new Swiss recommendations. Swiss Working Group for Endocarditis Prophylaxis. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 2000;130:1013-1026.

9. Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:954-970.

1. Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA 1997;277:1794-1801.

2. Durack DT. Prevention of infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med 1995;332:38-44.

3. Zuppiroli A, Rinaldi M, Kramer-Fox R, Favilli S, Roman MJ, Devereux RB. Natural history of mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:1028-1032.

4. Awadallah SM, Kavey RE, Byrum CJ, Smith FC, Kveselis DA, Blackman MS. The changing pattern of infective endocarditis in childhood. Am J Cardiol 1991;68:90-94.

5. McKinsey DS, Ratts TE, Bisno AL. Underlying cardiac lesions in adults with infective endocarditis. The changing spectrum. Am J Med 1987;82:681-688.

6. Shulman ST, Amren DP, Bisno AL, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis: A statement for health professionals by the Committee on Rheumatic Fever and Bacterial Endocarditis of the Council on Cardiovascular Diseases in the Young of the American Heart Association. Am J Dis Child 1985;139:232-235.

7. Dajani AS, Bisno AL, Chung KJ, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA 1990;264:2919-2922.

8. Moreillon P. Endocarditis prophylaxis revisited: experimental evidence of efficacy and new Swiss recommendations. Swiss Working Group for Endocarditis Prophylaxis. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 2000;130:1013-1026.

9. Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:954-970.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network