User login

Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Outcomes by p16 INK4a Antigen Status in a Veteran Population

Since 1983, the correlation between head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been of great interest to head and neck oncologists.1 In 1998, Smith and colleagues provided evidence of HPV as an independent risk factor for the development of head and neck SCC.2 HPV-associated head and neck SCC accounts for between 30% and 64% of oropharyngeal SCC, depending on the published study; tonsil primaries account for the majority of these cancers.3,4

The presence of HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins leads to the inactivation of p53 and pRb tumor suppressors. Furthermore, Ragin and colleagues discussed a distinct molecular pathway specific to HPV-associated head and neck SCC, which was different from non–HPV-associated head and neck SCC, involving genetic mutations in CDKN2A/p16.5

Current methods in correlating the presence of HPV infection in head and neck SCC have centered on p16INK4a (p16) immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining and DNA in situ hybridization (ISH) for specific HPV DNA types. IHC staining for p16 involves a monoclonal antibody specific to p16. The usefulness of this test relies on p16 overexpression due to the inactivation of pRb by the HPV E7 oncoprotein. This test is readily performed on archived tissue and has a documented sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 79%, respectively, as reported by Singhi and Westra in 2010.6 HPV DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization is the gold standard for determining the presence of specific types of HPV DNA; however, p16 IHC can serve as a rapid, less costly means of studying archived tissue, lending its utility to retrospective population-based studies.

METHODS

A retrospective study was designed to determine the proportion of HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population, using p16 antigen IHC on paraffin-embedded tissue as the surrogate marker for the presence of HPV infection. Patients consisted of veterans who were treated for oropharyngeal SCC at Veterans Affairs Memphis Healthcare System (VAMHS) in Tennessee between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2008. This data range allowed for at least 5 years of follow-up. Patients were excluded who lacked enough tissue specimens for analysis. Measurement outcomes included p16 expression, with subset analysis by race and ethnicity, degree of tobacco and alcohol use, tumor location, stage, age at diagnosis, and survival outcome. Microsoft Excel was used to calculate Fisher exact test, Student t test, and χ2 statistics. Significance was set at P < .05. This study received institutional review board approval from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and the VAMHS.

RESULTS

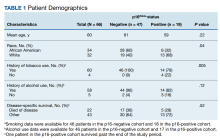

We identified 66 total cases of oropharyngeal SCC; 19 cases (29%) were positive for p16. The mean age at diagnosis for the p16-positive cohort was 59 years vs 61 years for the p16-negative cohort (P = .22; Table 1).

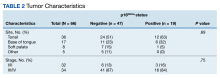

Although the tonsil was the most common site of tumor origin in both the p16-positive and negative cohorts (63% vs 51%, respectively), our analysis showed no statistically significant difference in sites of origin (P = .69) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The VAMHS population in our study had a lower proportion of HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC compared with studies on nonveteran populations (29% vs 40%-80%, respectively).5,6 This disparity may indicate a true difference in these populations or may be related to a decreased prevalence of HPV infection in the population served by the VAMHS. This single-institution population did not completely correlate with previous population studies. Specifically, age at presentation (equivalent to patients with p16-negative status rather than earlier age at onset), disease stage at presentation (lower stage for patients with p16-positive status), and disease-specific survival (not improved compared with patients with p16-negative status in other studies) were dissimilar to previous investigations.2,3

The increased age and staging at presentation could be related in these patients with p16-positive status, which may further account for the lack of improved survival. Furthermore, both groups tended to use alcohol at a high proportion; whereas other populations have had a lesser degree of alcohol intake with p16 positivity.1-4 These differences may be due to variations in the habits and behavior of VA patients compared with non-VA patients.3,4

HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC in published data has been associated with high-risk sexual behavior, lower age, and less tobacco and alcohol use.5,6 No difference was noted in tumor site predilection; however, the small size of our study could explain the lack of finding site preference shown in previous studies.2,3Other veteran-specific factors are absent in the at-large population, such as Agent Orange exposure. More than 8 million veterans (22%) from the Vietnam era self-reported Agent Orange exposure.7 Agent Orange exposure significantly predicted developing upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Oropharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, laryngeal, and thyroid cancers were significantly associated with Agent Orange exposure. Interestingly, these patients experienced an improved 10-year survival rate compared with patients not exposed to Agent Orange. This finding contrasts with our patients, who did not experience improved outcomes vs nonveteran patients with head and neck cancer.7

Suicide in veterans with head and neck cancer has been evaluated and was found at an incidence of 0.7%. Survivors of head and neck cancer are almost twice as likely to die by suicide compared with other cancer survivors. These patients have a higher rate of mental health disorders, substance misuse, and use of palliative care services.8 Sixty-five of 66 of our patients died during the 5-year observation period, although none died by suicide.

In a 2022 cohort study by Sun and colleagues, upfront surgical treatment was associated with a 23% reduced risk of stroke compared with definitive chemoradiotherapy in US veterans with oropharyngeal carcinoma.9 In our study, 58 of 66 patients (88%) received concurrent chemoradiation, possibly reflecting the more advanced stage of diagnosis in our study population. This was due to comorbidities and other health and economic factors. In our study, 43 patients (65%) died of factors not related to the disease, reflecting the overall comorbidity burden of this population. Seven patients (11%) in our 5-year study died of a documented stroke. In the study of veterans by Sun and colleagues, the 10-year cumulative incidence of stroke was 12.5% and death was 57.3%.9 Our veteran population experienced a similar incidence of strokes. These findings may need to be included when discussing the risk-benefit aspects of different treatment options with our veteran patients with oropharyngeal cancer.

To understand the influence of HPV infection on the course of oropharyngeal SCC in the VA patient population and to apply this understanding to future individualized treatment paradigms, this study can be expanded to a greater number of VA patients. p16 immunoexpression appears to be a useful surrogate for high-risk HPV infection in oropharyngeal SCC, and its ease of use supports its feasibility in further VA population analysis.10 While realizing that the veteran HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC population differs from the civilian HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC population, we also have realized that other unique considerations in the veteran population, such as chemical warfare exposure, mental illness, and vascular disease, complicate treatment decisions in these patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Disparities in racial distribution and tobacco use between patients with p16-positive and p16-negative status are similar to those reported in non-VA populations. In contrast, the frequently reported younger age at presentation and better disease outcomes seen in non-VA patients were not observed, perhaps due to the lower percentage of p16 expression in VA patients with oropharyngeal SCC. Whereas de-intensification of therapy may be considered for many patients with oropharygeal cancer that is HPV-associated because of improved prognosis, this approach should be undertaken with great care in this group of patients. Personalization of therapy for these HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC in the veteran population must be adapted to mitigate this critical disparity.

1. Syrjänen K, Syrjänen S, Lamberg M, Pyrhönen S, Nuutinen J. Morphological and immunohistochemical evidence suggesting human papillomavirus (HPV) involvement in oral squamous cell carcinogenesis. Int J Oral Surg. 1983;12(6):418-424. doi:10.1016/s0300-9785(83)80033-7

2. Smith EM, Hoffman HT, Summersgill KS, Kirchner HL, Turek LP, Haugen TH. Human papillomavirus and risk of oral cancer. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(7):1098-1103. doi:10.1097/00005537-199807000-00027

3. Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24-35. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0912217

4. Ragin CC, Taioli E. Survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in relation to human papillomavirus infection: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(8):1813-1820. doi:10.1002/ijc.22851

5. Ragin CC, Taioli E, Weissfeld JL, et al. 11q13 amplification status and human papillomavirus in relation to p16 expression defines two distinct etiologies of head and neck tumours. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(10):1432-1438. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603394

6. Singhi AD, Westra WH. Comparison of human papillomavirus in situ hybridization and p16 immunohistochemistry in the detection of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer based on a prospective clinical experience. Cancer. 2010;116(9):2166-2173. doi:10.1002/cncr.25033

7. Mowery A, Conlin M, Clayburgh D. Increased risk of head and neck cancer in Agent Orange exposed Vietnam Era veterans. Oral Oncol. 2020;100:104483. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104483

8. Nugent SM, Morasco BJ, Handley R, et al. Risk of suicidal self-directed violence among US veteran survivors of head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(11):981-989. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2021.2625

9. Sun L, Brody R, Candelieri D, et al. Association between up-front surgery and risk of stroke in US veterans with oropharyngeal carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(8):740-747. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2022.1327

10. El-Naggar AK, Westra WH. p16 expression as a surrogate marker for HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma: a guide for interpretative relevance and consistency. Head Neck. 2012;34(4):459-461. doi:10.1002/hed.21974

Since 1983, the correlation between head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been of great interest to head and neck oncologists.1 In 1998, Smith and colleagues provided evidence of HPV as an independent risk factor for the development of head and neck SCC.2 HPV-associated head and neck SCC accounts for between 30% and 64% of oropharyngeal SCC, depending on the published study; tonsil primaries account for the majority of these cancers.3,4

The presence of HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins leads to the inactivation of p53 and pRb tumor suppressors. Furthermore, Ragin and colleagues discussed a distinct molecular pathway specific to HPV-associated head and neck SCC, which was different from non–HPV-associated head and neck SCC, involving genetic mutations in CDKN2A/p16.5

Current methods in correlating the presence of HPV infection in head and neck SCC have centered on p16INK4a (p16) immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining and DNA in situ hybridization (ISH) for specific HPV DNA types. IHC staining for p16 involves a monoclonal antibody specific to p16. The usefulness of this test relies on p16 overexpression due to the inactivation of pRb by the HPV E7 oncoprotein. This test is readily performed on archived tissue and has a documented sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 79%, respectively, as reported by Singhi and Westra in 2010.6 HPV DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization is the gold standard for determining the presence of specific types of HPV DNA; however, p16 IHC can serve as a rapid, less costly means of studying archived tissue, lending its utility to retrospective population-based studies.

METHODS

A retrospective study was designed to determine the proportion of HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population, using p16 antigen IHC on paraffin-embedded tissue as the surrogate marker for the presence of HPV infection. Patients consisted of veterans who were treated for oropharyngeal SCC at Veterans Affairs Memphis Healthcare System (VAMHS) in Tennessee between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2008. This data range allowed for at least 5 years of follow-up. Patients were excluded who lacked enough tissue specimens for analysis. Measurement outcomes included p16 expression, with subset analysis by race and ethnicity, degree of tobacco and alcohol use, tumor location, stage, age at diagnosis, and survival outcome. Microsoft Excel was used to calculate Fisher exact test, Student t test, and χ2 statistics. Significance was set at P < .05. This study received institutional review board approval from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and the VAMHS.

RESULTS

We identified 66 total cases of oropharyngeal SCC; 19 cases (29%) were positive for p16. The mean age at diagnosis for the p16-positive cohort was 59 years vs 61 years for the p16-negative cohort (P = .22; Table 1).

Although the tonsil was the most common site of tumor origin in both the p16-positive and negative cohorts (63% vs 51%, respectively), our analysis showed no statistically significant difference in sites of origin (P = .69) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The VAMHS population in our study had a lower proportion of HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC compared with studies on nonveteran populations (29% vs 40%-80%, respectively).5,6 This disparity may indicate a true difference in these populations or may be related to a decreased prevalence of HPV infection in the population served by the VAMHS. This single-institution population did not completely correlate with previous population studies. Specifically, age at presentation (equivalent to patients with p16-negative status rather than earlier age at onset), disease stage at presentation (lower stage for patients with p16-positive status), and disease-specific survival (not improved compared with patients with p16-negative status in other studies) were dissimilar to previous investigations.2,3

The increased age and staging at presentation could be related in these patients with p16-positive status, which may further account for the lack of improved survival. Furthermore, both groups tended to use alcohol at a high proportion; whereas other populations have had a lesser degree of alcohol intake with p16 positivity.1-4 These differences may be due to variations in the habits and behavior of VA patients compared with non-VA patients.3,4

HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC in published data has been associated with high-risk sexual behavior, lower age, and less tobacco and alcohol use.5,6 No difference was noted in tumor site predilection; however, the small size of our study could explain the lack of finding site preference shown in previous studies.2,3Other veteran-specific factors are absent in the at-large population, such as Agent Orange exposure. More than 8 million veterans (22%) from the Vietnam era self-reported Agent Orange exposure.7 Agent Orange exposure significantly predicted developing upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Oropharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, laryngeal, and thyroid cancers were significantly associated with Agent Orange exposure. Interestingly, these patients experienced an improved 10-year survival rate compared with patients not exposed to Agent Orange. This finding contrasts with our patients, who did not experience improved outcomes vs nonveteran patients with head and neck cancer.7

Suicide in veterans with head and neck cancer has been evaluated and was found at an incidence of 0.7%. Survivors of head and neck cancer are almost twice as likely to die by suicide compared with other cancer survivors. These patients have a higher rate of mental health disorders, substance misuse, and use of palliative care services.8 Sixty-five of 66 of our patients died during the 5-year observation period, although none died by suicide.

In a 2022 cohort study by Sun and colleagues, upfront surgical treatment was associated with a 23% reduced risk of stroke compared with definitive chemoradiotherapy in US veterans with oropharyngeal carcinoma.9 In our study, 58 of 66 patients (88%) received concurrent chemoradiation, possibly reflecting the more advanced stage of diagnosis in our study population. This was due to comorbidities and other health and economic factors. In our study, 43 patients (65%) died of factors not related to the disease, reflecting the overall comorbidity burden of this population. Seven patients (11%) in our 5-year study died of a documented stroke. In the study of veterans by Sun and colleagues, the 10-year cumulative incidence of stroke was 12.5% and death was 57.3%.9 Our veteran population experienced a similar incidence of strokes. These findings may need to be included when discussing the risk-benefit aspects of different treatment options with our veteran patients with oropharyngeal cancer.

To understand the influence of HPV infection on the course of oropharyngeal SCC in the VA patient population and to apply this understanding to future individualized treatment paradigms, this study can be expanded to a greater number of VA patients. p16 immunoexpression appears to be a useful surrogate for high-risk HPV infection in oropharyngeal SCC, and its ease of use supports its feasibility in further VA population analysis.10 While realizing that the veteran HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC population differs from the civilian HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC population, we also have realized that other unique considerations in the veteran population, such as chemical warfare exposure, mental illness, and vascular disease, complicate treatment decisions in these patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Disparities in racial distribution and tobacco use between patients with p16-positive and p16-negative status are similar to those reported in non-VA populations. In contrast, the frequently reported younger age at presentation and better disease outcomes seen in non-VA patients were not observed, perhaps due to the lower percentage of p16 expression in VA patients with oropharyngeal SCC. Whereas de-intensification of therapy may be considered for many patients with oropharygeal cancer that is HPV-associated because of improved prognosis, this approach should be undertaken with great care in this group of patients. Personalization of therapy for these HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC in the veteran population must be adapted to mitigate this critical disparity.

Since 1983, the correlation between head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been of great interest to head and neck oncologists.1 In 1998, Smith and colleagues provided evidence of HPV as an independent risk factor for the development of head and neck SCC.2 HPV-associated head and neck SCC accounts for between 30% and 64% of oropharyngeal SCC, depending on the published study; tonsil primaries account for the majority of these cancers.3,4

The presence of HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins leads to the inactivation of p53 and pRb tumor suppressors. Furthermore, Ragin and colleagues discussed a distinct molecular pathway specific to HPV-associated head and neck SCC, which was different from non–HPV-associated head and neck SCC, involving genetic mutations in CDKN2A/p16.5

Current methods in correlating the presence of HPV infection in head and neck SCC have centered on p16INK4a (p16) immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining and DNA in situ hybridization (ISH) for specific HPV DNA types. IHC staining for p16 involves a monoclonal antibody specific to p16. The usefulness of this test relies on p16 overexpression due to the inactivation of pRb by the HPV E7 oncoprotein. This test is readily performed on archived tissue and has a documented sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 79%, respectively, as reported by Singhi and Westra in 2010.6 HPV DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization is the gold standard for determining the presence of specific types of HPV DNA; however, p16 IHC can serve as a rapid, less costly means of studying archived tissue, lending its utility to retrospective population-based studies.

METHODS

A retrospective study was designed to determine the proportion of HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population, using p16 antigen IHC on paraffin-embedded tissue as the surrogate marker for the presence of HPV infection. Patients consisted of veterans who were treated for oropharyngeal SCC at Veterans Affairs Memphis Healthcare System (VAMHS) in Tennessee between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2008. This data range allowed for at least 5 years of follow-up. Patients were excluded who lacked enough tissue specimens for analysis. Measurement outcomes included p16 expression, with subset analysis by race and ethnicity, degree of tobacco and alcohol use, tumor location, stage, age at diagnosis, and survival outcome. Microsoft Excel was used to calculate Fisher exact test, Student t test, and χ2 statistics. Significance was set at P < .05. This study received institutional review board approval from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and the VAMHS.

RESULTS

We identified 66 total cases of oropharyngeal SCC; 19 cases (29%) were positive for p16. The mean age at diagnosis for the p16-positive cohort was 59 years vs 61 years for the p16-negative cohort (P = .22; Table 1).

Although the tonsil was the most common site of tumor origin in both the p16-positive and negative cohorts (63% vs 51%, respectively), our analysis showed no statistically significant difference in sites of origin (P = .69) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The VAMHS population in our study had a lower proportion of HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC compared with studies on nonveteran populations (29% vs 40%-80%, respectively).5,6 This disparity may indicate a true difference in these populations or may be related to a decreased prevalence of HPV infection in the population served by the VAMHS. This single-institution population did not completely correlate with previous population studies. Specifically, age at presentation (equivalent to patients with p16-negative status rather than earlier age at onset), disease stage at presentation (lower stage for patients with p16-positive status), and disease-specific survival (not improved compared with patients with p16-negative status in other studies) were dissimilar to previous investigations.2,3

The increased age and staging at presentation could be related in these patients with p16-positive status, which may further account for the lack of improved survival. Furthermore, both groups tended to use alcohol at a high proportion; whereas other populations have had a lesser degree of alcohol intake with p16 positivity.1-4 These differences may be due to variations in the habits and behavior of VA patients compared with non-VA patients.3,4

HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC in published data has been associated with high-risk sexual behavior, lower age, and less tobacco and alcohol use.5,6 No difference was noted in tumor site predilection; however, the small size of our study could explain the lack of finding site preference shown in previous studies.2,3Other veteran-specific factors are absent in the at-large population, such as Agent Orange exposure. More than 8 million veterans (22%) from the Vietnam era self-reported Agent Orange exposure.7 Agent Orange exposure significantly predicted developing upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Oropharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, laryngeal, and thyroid cancers were significantly associated with Agent Orange exposure. Interestingly, these patients experienced an improved 10-year survival rate compared with patients not exposed to Agent Orange. This finding contrasts with our patients, who did not experience improved outcomes vs nonveteran patients with head and neck cancer.7

Suicide in veterans with head and neck cancer has been evaluated and was found at an incidence of 0.7%. Survivors of head and neck cancer are almost twice as likely to die by suicide compared with other cancer survivors. These patients have a higher rate of mental health disorders, substance misuse, and use of palliative care services.8 Sixty-five of 66 of our patients died during the 5-year observation period, although none died by suicide.

In a 2022 cohort study by Sun and colleagues, upfront surgical treatment was associated with a 23% reduced risk of stroke compared with definitive chemoradiotherapy in US veterans with oropharyngeal carcinoma.9 In our study, 58 of 66 patients (88%) received concurrent chemoradiation, possibly reflecting the more advanced stage of diagnosis in our study population. This was due to comorbidities and other health and economic factors. In our study, 43 patients (65%) died of factors not related to the disease, reflecting the overall comorbidity burden of this population. Seven patients (11%) in our 5-year study died of a documented stroke. In the study of veterans by Sun and colleagues, the 10-year cumulative incidence of stroke was 12.5% and death was 57.3%.9 Our veteran population experienced a similar incidence of strokes. These findings may need to be included when discussing the risk-benefit aspects of different treatment options with our veteran patients with oropharyngeal cancer.

To understand the influence of HPV infection on the course of oropharyngeal SCC in the VA patient population and to apply this understanding to future individualized treatment paradigms, this study can be expanded to a greater number of VA patients. p16 immunoexpression appears to be a useful surrogate for high-risk HPV infection in oropharyngeal SCC, and its ease of use supports its feasibility in further VA population analysis.10 While realizing that the veteran HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC population differs from the civilian HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC population, we also have realized that other unique considerations in the veteran population, such as chemical warfare exposure, mental illness, and vascular disease, complicate treatment decisions in these patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Disparities in racial distribution and tobacco use between patients with p16-positive and p16-negative status are similar to those reported in non-VA populations. In contrast, the frequently reported younger age at presentation and better disease outcomes seen in non-VA patients were not observed, perhaps due to the lower percentage of p16 expression in VA patients with oropharyngeal SCC. Whereas de-intensification of therapy may be considered for many patients with oropharygeal cancer that is HPV-associated because of improved prognosis, this approach should be undertaken with great care in this group of patients. Personalization of therapy for these HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC in the veteran population must be adapted to mitigate this critical disparity.

1. Syrjänen K, Syrjänen S, Lamberg M, Pyrhönen S, Nuutinen J. Morphological and immunohistochemical evidence suggesting human papillomavirus (HPV) involvement in oral squamous cell carcinogenesis. Int J Oral Surg. 1983;12(6):418-424. doi:10.1016/s0300-9785(83)80033-7

2. Smith EM, Hoffman HT, Summersgill KS, Kirchner HL, Turek LP, Haugen TH. Human papillomavirus and risk of oral cancer. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(7):1098-1103. doi:10.1097/00005537-199807000-00027

3. Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24-35. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0912217

4. Ragin CC, Taioli E. Survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in relation to human papillomavirus infection: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(8):1813-1820. doi:10.1002/ijc.22851

5. Ragin CC, Taioli E, Weissfeld JL, et al. 11q13 amplification status and human papillomavirus in relation to p16 expression defines two distinct etiologies of head and neck tumours. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(10):1432-1438. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603394

6. Singhi AD, Westra WH. Comparison of human papillomavirus in situ hybridization and p16 immunohistochemistry in the detection of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer based on a prospective clinical experience. Cancer. 2010;116(9):2166-2173. doi:10.1002/cncr.25033

7. Mowery A, Conlin M, Clayburgh D. Increased risk of head and neck cancer in Agent Orange exposed Vietnam Era veterans. Oral Oncol. 2020;100:104483. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104483

8. Nugent SM, Morasco BJ, Handley R, et al. Risk of suicidal self-directed violence among US veteran survivors of head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(11):981-989. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2021.2625

9. Sun L, Brody R, Candelieri D, et al. Association between up-front surgery and risk of stroke in US veterans with oropharyngeal carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(8):740-747. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2022.1327

10. El-Naggar AK, Westra WH. p16 expression as a surrogate marker for HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma: a guide for interpretative relevance and consistency. Head Neck. 2012;34(4):459-461. doi:10.1002/hed.21974

1. Syrjänen K, Syrjänen S, Lamberg M, Pyrhönen S, Nuutinen J. Morphological and immunohistochemical evidence suggesting human papillomavirus (HPV) involvement in oral squamous cell carcinogenesis. Int J Oral Surg. 1983;12(6):418-424. doi:10.1016/s0300-9785(83)80033-7

2. Smith EM, Hoffman HT, Summersgill KS, Kirchner HL, Turek LP, Haugen TH. Human papillomavirus and risk of oral cancer. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(7):1098-1103. doi:10.1097/00005537-199807000-00027

3. Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24-35. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0912217

4. Ragin CC, Taioli E. Survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in relation to human papillomavirus infection: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(8):1813-1820. doi:10.1002/ijc.22851

5. Ragin CC, Taioli E, Weissfeld JL, et al. 11q13 amplification status and human papillomavirus in relation to p16 expression defines two distinct etiologies of head and neck tumours. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(10):1432-1438. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603394

6. Singhi AD, Westra WH. Comparison of human papillomavirus in situ hybridization and p16 immunohistochemistry in the detection of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer based on a prospective clinical experience. Cancer. 2010;116(9):2166-2173. doi:10.1002/cncr.25033

7. Mowery A, Conlin M, Clayburgh D. Increased risk of head and neck cancer in Agent Orange exposed Vietnam Era veterans. Oral Oncol. 2020;100:104483. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104483

8. Nugent SM, Morasco BJ, Handley R, et al. Risk of suicidal self-directed violence among US veteran survivors of head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(11):981-989. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2021.2625

9. Sun L, Brody R, Candelieri D, et al. Association between up-front surgery and risk of stroke in US veterans with oropharyngeal carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(8):740-747. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2022.1327

10. El-Naggar AK, Westra WH. p16 expression as a surrogate marker for HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma: a guide for interpretative relevance and consistency. Head Neck. 2012;34(4):459-461. doi:10.1002/hed.21974