User login

What Dermatology Residents Need to Know About Joining Group Practices

What Dermatology Residents Need to Know About Joining Group Practices

Choosing your first job out of residency can be overwhelming. The things you need to consider go way beyond the job itself: things like geography, work/life balance, and practice focus (eg, skin cancer, cosmetics, medical dermatology, pediatrics) are all relatively independent factors from the specific practice you join. About 1 in 6 dermatologists change practices every year, with even higher rates for new graduates.1

Drawing from my 20 years of experience as a dermatologist (10 in academia and 10 in 3 different private group practice settings—one that was independently owned and 2 with private equity owners, of which I am one), I have seen firsthand what matters and what does not when it comes to joining a group practice, both in my own career and in watching the careers of many young dermatologists. I will do my best to summarize that experience into useful advice.

Important Factors to Consider When Choosing a Practice

As a second- or third-year resident, you likely are excited but nervous about leaping into practice. To approach it with confidence, allow me to outline certain factors that apply to all dermatology practices that you may consider joining as you start your career and beyond.

- Every Practice Owner Has to Prioritize Profit. Independent owners need to build the value of their main asset, academics need to fund research and teaching, and private equity owners need to drive returns for their investors. In other words, there are lots of negative situations in academic and independently owned groups, although private equity gets all the bad press.2-5 Nothing inherently makes one type of practice setting better; it depends on the specific organization. Owners do care about other things beyond just profit (eg, providing quality care, performing cutting-edge research), but when the rubber meets the road, if a practice is providing amazing quality care but losing money doing so, in a short time it won’t be providing any care at all.

- There Is No Free Money. Your long-term compensation will 100% be determined by how much revenue you generate minus the overhead. There is no magic fund to boost your pay long term, no matter how badly the practice needs or wants you. Be clear and even blunt: ask how the practice is going to profit from you. Ask how they plan to make back any signing bonus or guaranteed salary. If they are paying you a higher percentage of collections, ask them how they are able to pay more than competitors. If they say it is because they are more efficient with lower overhead, make sure that increased efficiency does not translate into less support.

- Percent of Collections Is Irrelevant. OK, perhaps not completely irrelevant, but it is one of the least important aspects in determining how much you will make or how happy you will be. Percent of collections is the percentage of the money that the practice actually collects that is paid out to you as compensation. For example, if your percentage of collections is 40%, that means that if the practice collects $1,000,000 for the care you deliver, you will be compensated $400,000. Read on to find out why it is not as important as it seems.

- Don’t Get Too Hung Up on the Details of the Contract. I have seen so many young dermatologists spend enormous amounts of time and money on attorneys and negotiating the fine points of the contract, but not a single one has ever said later that because of all that negotiation they were protected or treated well when things got contentious. What it comes down to is that, if the practice wants to treat you well, they will. If they want to treat you badly, no contract on earth can protect you from all the ways they can do so. And if you leave, no matter what the contract says, they can do whatever they want unless you are willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight them in court. So review the contract with an attorney and know what it says, but don’t sweat every period and clause. It isn’t worth it.

- Your Day-to-Day Is Everything. The practice you join may be the best-run practice in the world in every way, except that the office you happen to be going to work in is the one office in the practice that has 2 providers who are jerks and everyone dreads coming to work every morning. There are so many other examples of ways one location can be a disaster even in a great practice—and unfortunately, even great locations can change. The best you can do is to make sure you know where you will be working and with whom. Go and visit the actual office and spend a day shadowing to feel what the vibe is.

What Really Matters

If factors like the percentage of collections you keep are not the big things, what are? The good and bad news is that there isn’t a single answer to this question. Rather, the fundamental question is whether the practice’s plan to maximize profit includes having satisfied, motivated, and engaged long-term providers. Obviously every group practice says this is fundamental to them, but often it isn’t true. Your real job is to find out whether or not it is. The second fundamental question is whether or not the leadership and members of a group practice are competent. It doesn’t matter if they want and intend to do everything right; if the practice is not competent at getting it done, your life practicing dermatology there is not going to be good.

As a dermatologist who has practiced for 20 years in multiple settings, here are some of the questions I would ask when assessing a practice setting I might consider joining. The practice should be able to easily answer all of these questions. If they won’t, can’t, or don’t—or if they answer but don’t give you clear, concrete responses—it is a huge red flag. It could be that they know you won’t like the answers or it could be that they don’t know the answers, but either reason indicates a big problem.

- How do the contracted rates compare to other practices? Pick 5 to 10 Current Procedural Terminology codes you expect to bill the most and ask the practice to tell you the contracted rates for each of those codes with their top 5 payers. Get the same information from all the practices you are considering joining and compare them. The variation between 2 practices in the same market can be as high as 30%. That means that for doing the same work at Practice A you could collect $800,000 and at Practice B in the same market you could collect more than $1,000,000. Getting 45% of your collection from Practice A is a losing proposition compared to getting 40% at Practice B.

- What is the collection rate? If the practice has great contracted rates but terrible revenue cycle management operations, the rates don’t matter. For example, maybe their contracted rate for a given code is $150, compared to another practice whose contracted rate is $125. But if their collection rate is only 60% and the other practice has a collection rate of 80%, they are only getting $90 while the practice with the lower contracted rate is getting $100.

- What billing and coding support does the practice offer? Are you expected to know and keep up with all the procedure codes, modifiers, etc, and use them correctly yourself or do they have professional coders who review every visit? Do they appeal every denied claim? Will you get reports on what charges get denied and why so that you can adjust your practices to avoid further denials?

- How do they train and assign medical assistants (MAs)? The single biggest determinant of your day-to-day productivity and happiness will be your MAs. Having 3 experienced, efficient MAs will allow you to see 50 patients per day with less effort and more fun than seeing 30 patients per day with 2 inexperienced, inefficient MAs. Seeing 50 patients per day at 40% of collections leads to you earning a lot more than seeing 30 per day at 50% of collections. Beyond the basic question of how many MAs you will have, also ask: Will you be expected to train them yourself, or does the practice have a formal training program? Who assesses how well they are performing? Will you have the same MAs every day? When more senior providers have MAs call off sick or leave the practice, will your MAs be pulled to cover their clinics? If that happens, will you be compensated in some way? Get the answers in writing.

- What is the “feel” of the office you will be working in? Ideally you will go and spend a day seeing patients in the office with one of the existing providers to get a sense of whether it’s a place you will be excited to come to every morning. Do you like the other providers? Is there someone who could act as a mentor for you? Does the staff seem happy? Will the physical layout and square footage accommodate the way you imagine practicing? Are the sociodemographics of the patients a fit for what you want?

- Who will be the office manager responsible for your personal practice? Some practices have an on-site manager for every location; others have district or regional managers who are split between multiple practices. Some have both. All can work, but having a competent, supportive office manager with whom you get along with whom and who “gets it” is crucial. You should ask about office manager turnover (high rates are bad, of course) and should ask to meet and interview the office manager who will be the boots on the ground for the practice in your location.

- How much demand for services is there and how are new patients scheduled? If the new hire gets all the hair loss, acne, and eczema cases and the established providers get all the skin cancer/Medicare patients, you are not going to have a balanced patient mix, and you are not going to meet productivity goals because you won’t be doing enough procedures. If there is not enough demand to fill your schedule, what kind of marketing support does the practice offer and what other approaches might they take? If you want to do cosmetics, how are they going to help you grow in that area? Are there other providers who don’t do cosmetics and will refer to you? Is there already someone in the practice who all the referrals go to? Is your percentage of collections based on total collections or on collections after the cost of injectables is deducted?

- What educational support does the practice offer? Do they have an annual meeting for networking and continuing medical education (CME)? If so, will you be expected to use your CME budget to pay to attend? Are there restrictions on what you can use your CME budget for? Is your CME budget considered part of your percentage of collections? Are there experts in the practice you can go to if you have a challenging case or difficult situation?

- Are physician associates and nurse practitioners a big part of the practice? Will you have the opportunity to increase your compensation by supervising them? If so, what is expected of supervising physicians and how are they compensated (flat fee vs percentage of collections vs another model)?

- What does the noncompete say? Obviously the shorter the time period and the smaller the distance, the better. For most practices, a noncompete is nonnegotiable. But there are some nuances to consider: Is the restricted distance from any location that the practice has in the market, or from any location(s) in which you personally have practiced, or from the primary location(s) in which you have practiced? If it is from the primary location(s), get details on how this term is defined: How much do you have to be at a location before it is considered primary? If you stop going to a location, after what period of time is it no longer considered a primary location? Additional questions to ask about noncompetes include: Is there a nonsolicitation clause for employees or patients? Will the practice include a buy-out clause in which you can pay them a set amount to waive the noncompete? Will they make the noncompete time dependent? In other words, if it is a terrible fit and you want to leave in the first year, there is very little justification for them to enforce a noncompete—but unless it is in your contract that they won’t enforce it if you leave before a certain amount of time, they will enforce it.

- Is there a path to having equity in the practice? In academia, this obviously is not a possibility. In independent practices it generally is referred to as an ownership stake or becoming a partner, and in private-equity groups it is literally referred to as “equity,” but they mean essentially the same thing for our purposes. It benefits the practice if you have equity because it gives you a reason to work to help increase the value of the practice. It benefits you to have equity because it means you have more input into decisions that will affect you (and the influence is proportional to how much equity you have) and the equity is an asset that can become very valuable.

The primary advice I have when it comes to being promised an opportunity to become an owner/partner in an independent group is to get the timing and conditions under which you can become an owner in the contract and strongly advocate for a clause that states that if you are not offered the opportunity as defined in the contract that you will be compensated. Also consider what happens if the current owner(s) sell the practice before you become an owner.

In private-equity groups, ask how many of the current providers have equity and ask how the equity is currently divided (what percentage is held by the private equity group, what percentage is held by the CEO and other executives, and what percentage is held by providers). The more equity held by the executive leadership and providers the better, as that means more people are on the same team of trying to increase the value of the practice. Find out how and when you will be able to buy in and try to get this in the contract or at least in writing. Also ask for a guarantee that your equity will not decrease in value. There are instances in which the practice loses value over time due to mismanagement, and the legal structure typically prioritizes the equity of the private-equity owners over the equity of providers. This is called an equity waterfall. Equity that providers were told was worth millions can literally be worth nothing.

One Key Thing You Need to Know

More important than the formal interviews and meetings that will provide you with answers to the questions outlined here, you need to know if you can trust the answers and you need to know the overall culture of the organization. Are they truly pro-provider, and do they believe that engaged and supported providers are the best route to long-term profit maximization? Or do they see providers primarily as replaceable adversaries who need to be placated and managed in order to minimize overhead? The only way to find out is to talk to providers already working there.

If you ask the practice for contact information for providers you can talk to, they likely will put you in touch with those who they know are going to talk about the practice in the best possible light. Be aware that providers may speak positively about a practice for a few different reasons other than that they are actually happy. Maybe the provider has an ownership stake in the practice and will benefit financially if you join. Keep in mind that, if a friend or colleague introduced you to the practice, they are almost certainly getting a substantial referral bonus if you join, so they may not be unbiased; however, if they are an actual friend, the last thing they want is for you to join and be unhappy in the practice because they didn’t tell the truth.

To learn about the experiences of others in your situation who have joined the practice, go to the website and look through the list of providers. Ideally, look for people who are in their first 3 years out of residency who have been there long enough to know the ins and outs but who still are considered newbies and almost certainly don’t have a meaningful ownership stake or strong allegiance to the practice. If it is a geographically widespread practice, focus on people in the region you will be in, but also talk to at least one person from a distant site.

Next, go to the American Academy of Dermatology’s website to find the email addresses for the providers you want to contact in the member directory. Send them an email explaining that you are thinking about joining the practice and that you would like to have an off-the-record phone conversation with them about their experiences. If they decline or don’t respond, it could be a red flag that likely means they don’t think they can speak positively about the practice. If they do agree to speak with you, you can reiterate at that time that the conversation is off the record and that you won’t relay your discussion to anyone at the practice.

Here is a sample email you can use to reach out to providers from a practice you are considering joining:

Subject: Advice on Joining [Practice Name]

Dear Dr. [Name],

I’m a dermatology resident considering joining [Practice Name] and came across your profile. Would you be willing to have a brief (5 to 10 minutes), off-the-record call about your experience? I’d value your perspective and won’t share our conversation with the practice. Thank you!

Best, [Your Name]

Start the conversation with open-ended questions and see where it goes. Some things to ask might be, are you glad you joined the practice? Was there anything that surprised you after you joined? Is there anything you wish you would have asked or known before you joined? I would recommend not asking specifically about their compensation, as it likely will be different from what you are being offered due to variations in location and current market situations.

Final Thoughts

There is no perfect dermatology practice, but the approach outlined here—rooted in first principles and real-world experience—will help you find one that is right for you. Ask tough questions, talk to other providers, and trust your instincts.

- Cwalina TB, Mazmudar RS, Bordeaux JS, et al. Dermatologist workforce mobility: recent trends and characteristics. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:323-325. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5862

- Oscherwitz ME, Godinich BM, Patel RH, et al. Effects of private equity on dermatologic quality of patient care. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:E100-E102. doi:10.1111/jdv.20191

- Walsh S, Seaton E. Private equity in dermatology: a cloud on the horizon of quality care? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:9-10. doi:10.1111/jdv.20272

- Konda S, Patel S, Francis J. Private equity: the bad and the ugly. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:597-610. doi:10.1016/j.det.2023.04.004

- Novice T, Portney D, Eshaq M. Dermatology resident perspectives on practice ownership structures and private equity-backed group practices. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:296-302. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.008

Choosing your first job out of residency can be overwhelming. The things you need to consider go way beyond the job itself: things like geography, work/life balance, and practice focus (eg, skin cancer, cosmetics, medical dermatology, pediatrics) are all relatively independent factors from the specific practice you join. About 1 in 6 dermatologists change practices every year, with even higher rates for new graduates.1

Drawing from my 20 years of experience as a dermatologist (10 in academia and 10 in 3 different private group practice settings—one that was independently owned and 2 with private equity owners, of which I am one), I have seen firsthand what matters and what does not when it comes to joining a group practice, both in my own career and in watching the careers of many young dermatologists. I will do my best to summarize that experience into useful advice.

Important Factors to Consider When Choosing a Practice

As a second- or third-year resident, you likely are excited but nervous about leaping into practice. To approach it with confidence, allow me to outline certain factors that apply to all dermatology practices that you may consider joining as you start your career and beyond.

- Every Practice Owner Has to Prioritize Profit. Independent owners need to build the value of their main asset, academics need to fund research and teaching, and private equity owners need to drive returns for their investors. In other words, there are lots of negative situations in academic and independently owned groups, although private equity gets all the bad press.2-5 Nothing inherently makes one type of practice setting better; it depends on the specific organization. Owners do care about other things beyond just profit (eg, providing quality care, performing cutting-edge research), but when the rubber meets the road, if a practice is providing amazing quality care but losing money doing so, in a short time it won’t be providing any care at all.

- There Is No Free Money. Your long-term compensation will 100% be determined by how much revenue you generate minus the overhead. There is no magic fund to boost your pay long term, no matter how badly the practice needs or wants you. Be clear and even blunt: ask how the practice is going to profit from you. Ask how they plan to make back any signing bonus or guaranteed salary. If they are paying you a higher percentage of collections, ask them how they are able to pay more than competitors. If they say it is because they are more efficient with lower overhead, make sure that increased efficiency does not translate into less support.

- Percent of Collections Is Irrelevant. OK, perhaps not completely irrelevant, but it is one of the least important aspects in determining how much you will make or how happy you will be. Percent of collections is the percentage of the money that the practice actually collects that is paid out to you as compensation. For example, if your percentage of collections is 40%, that means that if the practice collects $1,000,000 for the care you deliver, you will be compensated $400,000. Read on to find out why it is not as important as it seems.

- Don’t Get Too Hung Up on the Details of the Contract. I have seen so many young dermatologists spend enormous amounts of time and money on attorneys and negotiating the fine points of the contract, but not a single one has ever said later that because of all that negotiation they were protected or treated well when things got contentious. What it comes down to is that, if the practice wants to treat you well, they will. If they want to treat you badly, no contract on earth can protect you from all the ways they can do so. And if you leave, no matter what the contract says, they can do whatever they want unless you are willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight them in court. So review the contract with an attorney and know what it says, but don’t sweat every period and clause. It isn’t worth it.

- Your Day-to-Day Is Everything. The practice you join may be the best-run practice in the world in every way, except that the office you happen to be going to work in is the one office in the practice that has 2 providers who are jerks and everyone dreads coming to work every morning. There are so many other examples of ways one location can be a disaster even in a great practice—and unfortunately, even great locations can change. The best you can do is to make sure you know where you will be working and with whom. Go and visit the actual office and spend a day shadowing to feel what the vibe is.

What Really Matters

If factors like the percentage of collections you keep are not the big things, what are? The good and bad news is that there isn’t a single answer to this question. Rather, the fundamental question is whether the practice’s plan to maximize profit includes having satisfied, motivated, and engaged long-term providers. Obviously every group practice says this is fundamental to them, but often it isn’t true. Your real job is to find out whether or not it is. The second fundamental question is whether or not the leadership and members of a group practice are competent. It doesn’t matter if they want and intend to do everything right; if the practice is not competent at getting it done, your life practicing dermatology there is not going to be good.

As a dermatologist who has practiced for 20 years in multiple settings, here are some of the questions I would ask when assessing a practice setting I might consider joining. The practice should be able to easily answer all of these questions. If they won’t, can’t, or don’t—or if they answer but don’t give you clear, concrete responses—it is a huge red flag. It could be that they know you won’t like the answers or it could be that they don’t know the answers, but either reason indicates a big problem.

- How do the contracted rates compare to other practices? Pick 5 to 10 Current Procedural Terminology codes you expect to bill the most and ask the practice to tell you the contracted rates for each of those codes with their top 5 payers. Get the same information from all the practices you are considering joining and compare them. The variation between 2 practices in the same market can be as high as 30%. That means that for doing the same work at Practice A you could collect $800,000 and at Practice B in the same market you could collect more than $1,000,000. Getting 45% of your collection from Practice A is a losing proposition compared to getting 40% at Practice B.

- What is the collection rate? If the practice has great contracted rates but terrible revenue cycle management operations, the rates don’t matter. For example, maybe their contracted rate for a given code is $150, compared to another practice whose contracted rate is $125. But if their collection rate is only 60% and the other practice has a collection rate of 80%, they are only getting $90 while the practice with the lower contracted rate is getting $100.

- What billing and coding support does the practice offer? Are you expected to know and keep up with all the procedure codes, modifiers, etc, and use them correctly yourself or do they have professional coders who review every visit? Do they appeal every denied claim? Will you get reports on what charges get denied and why so that you can adjust your practices to avoid further denials?

- How do they train and assign medical assistants (MAs)? The single biggest determinant of your day-to-day productivity and happiness will be your MAs. Having 3 experienced, efficient MAs will allow you to see 50 patients per day with less effort and more fun than seeing 30 patients per day with 2 inexperienced, inefficient MAs. Seeing 50 patients per day at 40% of collections leads to you earning a lot more than seeing 30 per day at 50% of collections. Beyond the basic question of how many MAs you will have, also ask: Will you be expected to train them yourself, or does the practice have a formal training program? Who assesses how well they are performing? Will you have the same MAs every day? When more senior providers have MAs call off sick or leave the practice, will your MAs be pulled to cover their clinics? If that happens, will you be compensated in some way? Get the answers in writing.

- What is the “feel” of the office you will be working in? Ideally you will go and spend a day seeing patients in the office with one of the existing providers to get a sense of whether it’s a place you will be excited to come to every morning. Do you like the other providers? Is there someone who could act as a mentor for you? Does the staff seem happy? Will the physical layout and square footage accommodate the way you imagine practicing? Are the sociodemographics of the patients a fit for what you want?

- Who will be the office manager responsible for your personal practice? Some practices have an on-site manager for every location; others have district or regional managers who are split between multiple practices. Some have both. All can work, but having a competent, supportive office manager with whom you get along with whom and who “gets it” is crucial. You should ask about office manager turnover (high rates are bad, of course) and should ask to meet and interview the office manager who will be the boots on the ground for the practice in your location.

- How much demand for services is there and how are new patients scheduled? If the new hire gets all the hair loss, acne, and eczema cases and the established providers get all the skin cancer/Medicare patients, you are not going to have a balanced patient mix, and you are not going to meet productivity goals because you won’t be doing enough procedures. If there is not enough demand to fill your schedule, what kind of marketing support does the practice offer and what other approaches might they take? If you want to do cosmetics, how are they going to help you grow in that area? Are there other providers who don’t do cosmetics and will refer to you? Is there already someone in the practice who all the referrals go to? Is your percentage of collections based on total collections or on collections after the cost of injectables is deducted?

- What educational support does the practice offer? Do they have an annual meeting for networking and continuing medical education (CME)? If so, will you be expected to use your CME budget to pay to attend? Are there restrictions on what you can use your CME budget for? Is your CME budget considered part of your percentage of collections? Are there experts in the practice you can go to if you have a challenging case or difficult situation?

- Are physician associates and nurse practitioners a big part of the practice? Will you have the opportunity to increase your compensation by supervising them? If so, what is expected of supervising physicians and how are they compensated (flat fee vs percentage of collections vs another model)?

- What does the noncompete say? Obviously the shorter the time period and the smaller the distance, the better. For most practices, a noncompete is nonnegotiable. But there are some nuances to consider: Is the restricted distance from any location that the practice has in the market, or from any location(s) in which you personally have practiced, or from the primary location(s) in which you have practiced? If it is from the primary location(s), get details on how this term is defined: How much do you have to be at a location before it is considered primary? If you stop going to a location, after what period of time is it no longer considered a primary location? Additional questions to ask about noncompetes include: Is there a nonsolicitation clause for employees or patients? Will the practice include a buy-out clause in which you can pay them a set amount to waive the noncompete? Will they make the noncompete time dependent? In other words, if it is a terrible fit and you want to leave in the first year, there is very little justification for them to enforce a noncompete—but unless it is in your contract that they won’t enforce it if you leave before a certain amount of time, they will enforce it.

- Is there a path to having equity in the practice? In academia, this obviously is not a possibility. In independent practices it generally is referred to as an ownership stake or becoming a partner, and in private-equity groups it is literally referred to as “equity,” but they mean essentially the same thing for our purposes. It benefits the practice if you have equity because it gives you a reason to work to help increase the value of the practice. It benefits you to have equity because it means you have more input into decisions that will affect you (and the influence is proportional to how much equity you have) and the equity is an asset that can become very valuable.

The primary advice I have when it comes to being promised an opportunity to become an owner/partner in an independent group is to get the timing and conditions under which you can become an owner in the contract and strongly advocate for a clause that states that if you are not offered the opportunity as defined in the contract that you will be compensated. Also consider what happens if the current owner(s) sell the practice before you become an owner.

In private-equity groups, ask how many of the current providers have equity and ask how the equity is currently divided (what percentage is held by the private equity group, what percentage is held by the CEO and other executives, and what percentage is held by providers). The more equity held by the executive leadership and providers the better, as that means more people are on the same team of trying to increase the value of the practice. Find out how and when you will be able to buy in and try to get this in the contract or at least in writing. Also ask for a guarantee that your equity will not decrease in value. There are instances in which the practice loses value over time due to mismanagement, and the legal structure typically prioritizes the equity of the private-equity owners over the equity of providers. This is called an equity waterfall. Equity that providers were told was worth millions can literally be worth nothing.

One Key Thing You Need to Know

More important than the formal interviews and meetings that will provide you with answers to the questions outlined here, you need to know if you can trust the answers and you need to know the overall culture of the organization. Are they truly pro-provider, and do they believe that engaged and supported providers are the best route to long-term profit maximization? Or do they see providers primarily as replaceable adversaries who need to be placated and managed in order to minimize overhead? The only way to find out is to talk to providers already working there.

If you ask the practice for contact information for providers you can talk to, they likely will put you in touch with those who they know are going to talk about the practice in the best possible light. Be aware that providers may speak positively about a practice for a few different reasons other than that they are actually happy. Maybe the provider has an ownership stake in the practice and will benefit financially if you join. Keep in mind that, if a friend or colleague introduced you to the practice, they are almost certainly getting a substantial referral bonus if you join, so they may not be unbiased; however, if they are an actual friend, the last thing they want is for you to join and be unhappy in the practice because they didn’t tell the truth.

To learn about the experiences of others in your situation who have joined the practice, go to the website and look through the list of providers. Ideally, look for people who are in their first 3 years out of residency who have been there long enough to know the ins and outs but who still are considered newbies and almost certainly don’t have a meaningful ownership stake or strong allegiance to the practice. If it is a geographically widespread practice, focus on people in the region you will be in, but also talk to at least one person from a distant site.

Next, go to the American Academy of Dermatology’s website to find the email addresses for the providers you want to contact in the member directory. Send them an email explaining that you are thinking about joining the practice and that you would like to have an off-the-record phone conversation with them about their experiences. If they decline or don’t respond, it could be a red flag that likely means they don’t think they can speak positively about the practice. If they do agree to speak with you, you can reiterate at that time that the conversation is off the record and that you won’t relay your discussion to anyone at the practice.

Here is a sample email you can use to reach out to providers from a practice you are considering joining:

Subject: Advice on Joining [Practice Name]

Dear Dr. [Name],

I’m a dermatology resident considering joining [Practice Name] and came across your profile. Would you be willing to have a brief (5 to 10 minutes), off-the-record call about your experience? I’d value your perspective and won’t share our conversation with the practice. Thank you!

Best, [Your Name]

Start the conversation with open-ended questions and see where it goes. Some things to ask might be, are you glad you joined the practice? Was there anything that surprised you after you joined? Is there anything you wish you would have asked or known before you joined? I would recommend not asking specifically about their compensation, as it likely will be different from what you are being offered due to variations in location and current market situations.

Final Thoughts

There is no perfect dermatology practice, but the approach outlined here—rooted in first principles and real-world experience—will help you find one that is right for you. Ask tough questions, talk to other providers, and trust your instincts.

Choosing your first job out of residency can be overwhelming. The things you need to consider go way beyond the job itself: things like geography, work/life balance, and practice focus (eg, skin cancer, cosmetics, medical dermatology, pediatrics) are all relatively independent factors from the specific practice you join. About 1 in 6 dermatologists change practices every year, with even higher rates for new graduates.1

Drawing from my 20 years of experience as a dermatologist (10 in academia and 10 in 3 different private group practice settings—one that was independently owned and 2 with private equity owners, of which I am one), I have seen firsthand what matters and what does not when it comes to joining a group practice, both in my own career and in watching the careers of many young dermatologists. I will do my best to summarize that experience into useful advice.

Important Factors to Consider When Choosing a Practice

As a second- or third-year resident, you likely are excited but nervous about leaping into practice. To approach it with confidence, allow me to outline certain factors that apply to all dermatology practices that you may consider joining as you start your career and beyond.

- Every Practice Owner Has to Prioritize Profit. Independent owners need to build the value of their main asset, academics need to fund research and teaching, and private equity owners need to drive returns for their investors. In other words, there are lots of negative situations in academic and independently owned groups, although private equity gets all the bad press.2-5 Nothing inherently makes one type of practice setting better; it depends on the specific organization. Owners do care about other things beyond just profit (eg, providing quality care, performing cutting-edge research), but when the rubber meets the road, if a practice is providing amazing quality care but losing money doing so, in a short time it won’t be providing any care at all.

- There Is No Free Money. Your long-term compensation will 100% be determined by how much revenue you generate minus the overhead. There is no magic fund to boost your pay long term, no matter how badly the practice needs or wants you. Be clear and even blunt: ask how the practice is going to profit from you. Ask how they plan to make back any signing bonus or guaranteed salary. If they are paying you a higher percentage of collections, ask them how they are able to pay more than competitors. If they say it is because they are more efficient with lower overhead, make sure that increased efficiency does not translate into less support.

- Percent of Collections Is Irrelevant. OK, perhaps not completely irrelevant, but it is one of the least important aspects in determining how much you will make or how happy you will be. Percent of collections is the percentage of the money that the practice actually collects that is paid out to you as compensation. For example, if your percentage of collections is 40%, that means that if the practice collects $1,000,000 for the care you deliver, you will be compensated $400,000. Read on to find out why it is not as important as it seems.

- Don’t Get Too Hung Up on the Details of the Contract. I have seen so many young dermatologists spend enormous amounts of time and money on attorneys and negotiating the fine points of the contract, but not a single one has ever said later that because of all that negotiation they were protected or treated well when things got contentious. What it comes down to is that, if the practice wants to treat you well, they will. If they want to treat you badly, no contract on earth can protect you from all the ways they can do so. And if you leave, no matter what the contract says, they can do whatever they want unless you are willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight them in court. So review the contract with an attorney and know what it says, but don’t sweat every period and clause. It isn’t worth it.

- Your Day-to-Day Is Everything. The practice you join may be the best-run practice in the world in every way, except that the office you happen to be going to work in is the one office in the practice that has 2 providers who are jerks and everyone dreads coming to work every morning. There are so many other examples of ways one location can be a disaster even in a great practice—and unfortunately, even great locations can change. The best you can do is to make sure you know where you will be working and with whom. Go and visit the actual office and spend a day shadowing to feel what the vibe is.

What Really Matters

If factors like the percentage of collections you keep are not the big things, what are? The good and bad news is that there isn’t a single answer to this question. Rather, the fundamental question is whether the practice’s plan to maximize profit includes having satisfied, motivated, and engaged long-term providers. Obviously every group practice says this is fundamental to them, but often it isn’t true. Your real job is to find out whether or not it is. The second fundamental question is whether or not the leadership and members of a group practice are competent. It doesn’t matter if they want and intend to do everything right; if the practice is not competent at getting it done, your life practicing dermatology there is not going to be good.

As a dermatologist who has practiced for 20 years in multiple settings, here are some of the questions I would ask when assessing a practice setting I might consider joining. The practice should be able to easily answer all of these questions. If they won’t, can’t, or don’t—or if they answer but don’t give you clear, concrete responses—it is a huge red flag. It could be that they know you won’t like the answers or it could be that they don’t know the answers, but either reason indicates a big problem.

- How do the contracted rates compare to other practices? Pick 5 to 10 Current Procedural Terminology codes you expect to bill the most and ask the practice to tell you the contracted rates for each of those codes with their top 5 payers. Get the same information from all the practices you are considering joining and compare them. The variation between 2 practices in the same market can be as high as 30%. That means that for doing the same work at Practice A you could collect $800,000 and at Practice B in the same market you could collect more than $1,000,000. Getting 45% of your collection from Practice A is a losing proposition compared to getting 40% at Practice B.

- What is the collection rate? If the practice has great contracted rates but terrible revenue cycle management operations, the rates don’t matter. For example, maybe their contracted rate for a given code is $150, compared to another practice whose contracted rate is $125. But if their collection rate is only 60% and the other practice has a collection rate of 80%, they are only getting $90 while the practice with the lower contracted rate is getting $100.

- What billing and coding support does the practice offer? Are you expected to know and keep up with all the procedure codes, modifiers, etc, and use them correctly yourself or do they have professional coders who review every visit? Do they appeal every denied claim? Will you get reports on what charges get denied and why so that you can adjust your practices to avoid further denials?

- How do they train and assign medical assistants (MAs)? The single biggest determinant of your day-to-day productivity and happiness will be your MAs. Having 3 experienced, efficient MAs will allow you to see 50 patients per day with less effort and more fun than seeing 30 patients per day with 2 inexperienced, inefficient MAs. Seeing 50 patients per day at 40% of collections leads to you earning a lot more than seeing 30 per day at 50% of collections. Beyond the basic question of how many MAs you will have, also ask: Will you be expected to train them yourself, or does the practice have a formal training program? Who assesses how well they are performing? Will you have the same MAs every day? When more senior providers have MAs call off sick or leave the practice, will your MAs be pulled to cover their clinics? If that happens, will you be compensated in some way? Get the answers in writing.

- What is the “feel” of the office you will be working in? Ideally you will go and spend a day seeing patients in the office with one of the existing providers to get a sense of whether it’s a place you will be excited to come to every morning. Do you like the other providers? Is there someone who could act as a mentor for you? Does the staff seem happy? Will the physical layout and square footage accommodate the way you imagine practicing? Are the sociodemographics of the patients a fit for what you want?

- Who will be the office manager responsible for your personal practice? Some practices have an on-site manager for every location; others have district or regional managers who are split between multiple practices. Some have both. All can work, but having a competent, supportive office manager with whom you get along with whom and who “gets it” is crucial. You should ask about office manager turnover (high rates are bad, of course) and should ask to meet and interview the office manager who will be the boots on the ground for the practice in your location.

- How much demand for services is there and how are new patients scheduled? If the new hire gets all the hair loss, acne, and eczema cases and the established providers get all the skin cancer/Medicare patients, you are not going to have a balanced patient mix, and you are not going to meet productivity goals because you won’t be doing enough procedures. If there is not enough demand to fill your schedule, what kind of marketing support does the practice offer and what other approaches might they take? If you want to do cosmetics, how are they going to help you grow in that area? Are there other providers who don’t do cosmetics and will refer to you? Is there already someone in the practice who all the referrals go to? Is your percentage of collections based on total collections or on collections after the cost of injectables is deducted?

- What educational support does the practice offer? Do they have an annual meeting for networking and continuing medical education (CME)? If so, will you be expected to use your CME budget to pay to attend? Are there restrictions on what you can use your CME budget for? Is your CME budget considered part of your percentage of collections? Are there experts in the practice you can go to if you have a challenging case or difficult situation?

- Are physician associates and nurse practitioners a big part of the practice? Will you have the opportunity to increase your compensation by supervising them? If so, what is expected of supervising physicians and how are they compensated (flat fee vs percentage of collections vs another model)?

- What does the noncompete say? Obviously the shorter the time period and the smaller the distance, the better. For most practices, a noncompete is nonnegotiable. But there are some nuances to consider: Is the restricted distance from any location that the practice has in the market, or from any location(s) in which you personally have practiced, or from the primary location(s) in which you have practiced? If it is from the primary location(s), get details on how this term is defined: How much do you have to be at a location before it is considered primary? If you stop going to a location, after what period of time is it no longer considered a primary location? Additional questions to ask about noncompetes include: Is there a nonsolicitation clause for employees or patients? Will the practice include a buy-out clause in which you can pay them a set amount to waive the noncompete? Will they make the noncompete time dependent? In other words, if it is a terrible fit and you want to leave in the first year, there is very little justification for them to enforce a noncompete—but unless it is in your contract that they won’t enforce it if you leave before a certain amount of time, they will enforce it.

- Is there a path to having equity in the practice? In academia, this obviously is not a possibility. In independent practices it generally is referred to as an ownership stake or becoming a partner, and in private-equity groups it is literally referred to as “equity,” but they mean essentially the same thing for our purposes. It benefits the practice if you have equity because it gives you a reason to work to help increase the value of the practice. It benefits you to have equity because it means you have more input into decisions that will affect you (and the influence is proportional to how much equity you have) and the equity is an asset that can become very valuable.

The primary advice I have when it comes to being promised an opportunity to become an owner/partner in an independent group is to get the timing and conditions under which you can become an owner in the contract and strongly advocate for a clause that states that if you are not offered the opportunity as defined in the contract that you will be compensated. Also consider what happens if the current owner(s) sell the practice before you become an owner.

In private-equity groups, ask how many of the current providers have equity and ask how the equity is currently divided (what percentage is held by the private equity group, what percentage is held by the CEO and other executives, and what percentage is held by providers). The more equity held by the executive leadership and providers the better, as that means more people are on the same team of trying to increase the value of the practice. Find out how and when you will be able to buy in and try to get this in the contract or at least in writing. Also ask for a guarantee that your equity will not decrease in value. There are instances in which the practice loses value over time due to mismanagement, and the legal structure typically prioritizes the equity of the private-equity owners over the equity of providers. This is called an equity waterfall. Equity that providers were told was worth millions can literally be worth nothing.

One Key Thing You Need to Know

More important than the formal interviews and meetings that will provide you with answers to the questions outlined here, you need to know if you can trust the answers and you need to know the overall culture of the organization. Are they truly pro-provider, and do they believe that engaged and supported providers are the best route to long-term profit maximization? Or do they see providers primarily as replaceable adversaries who need to be placated and managed in order to minimize overhead? The only way to find out is to talk to providers already working there.

If you ask the practice for contact information for providers you can talk to, they likely will put you in touch with those who they know are going to talk about the practice in the best possible light. Be aware that providers may speak positively about a practice for a few different reasons other than that they are actually happy. Maybe the provider has an ownership stake in the practice and will benefit financially if you join. Keep in mind that, if a friend or colleague introduced you to the practice, they are almost certainly getting a substantial referral bonus if you join, so they may not be unbiased; however, if they are an actual friend, the last thing they want is for you to join and be unhappy in the practice because they didn’t tell the truth.

To learn about the experiences of others in your situation who have joined the practice, go to the website and look through the list of providers. Ideally, look for people who are in their first 3 years out of residency who have been there long enough to know the ins and outs but who still are considered newbies and almost certainly don’t have a meaningful ownership stake or strong allegiance to the practice. If it is a geographically widespread practice, focus on people in the region you will be in, but also talk to at least one person from a distant site.

Next, go to the American Academy of Dermatology’s website to find the email addresses for the providers you want to contact in the member directory. Send them an email explaining that you are thinking about joining the practice and that you would like to have an off-the-record phone conversation with them about their experiences. If they decline or don’t respond, it could be a red flag that likely means they don’t think they can speak positively about the practice. If they do agree to speak with you, you can reiterate at that time that the conversation is off the record and that you won’t relay your discussion to anyone at the practice.

Here is a sample email you can use to reach out to providers from a practice you are considering joining:

Subject: Advice on Joining [Practice Name]

Dear Dr. [Name],

I’m a dermatology resident considering joining [Practice Name] and came across your profile. Would you be willing to have a brief (5 to 10 minutes), off-the-record call about your experience? I’d value your perspective and won’t share our conversation with the practice. Thank you!

Best, [Your Name]

Start the conversation with open-ended questions and see where it goes. Some things to ask might be, are you glad you joined the practice? Was there anything that surprised you after you joined? Is there anything you wish you would have asked or known before you joined? I would recommend not asking specifically about their compensation, as it likely will be different from what you are being offered due to variations in location and current market situations.

Final Thoughts

There is no perfect dermatology practice, but the approach outlined here—rooted in first principles and real-world experience—will help you find one that is right for you. Ask tough questions, talk to other providers, and trust your instincts.

- Cwalina TB, Mazmudar RS, Bordeaux JS, et al. Dermatologist workforce mobility: recent trends and characteristics. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:323-325. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5862

- Oscherwitz ME, Godinich BM, Patel RH, et al. Effects of private equity on dermatologic quality of patient care. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:E100-E102. doi:10.1111/jdv.20191

- Walsh S, Seaton E. Private equity in dermatology: a cloud on the horizon of quality care? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:9-10. doi:10.1111/jdv.20272

- Konda S, Patel S, Francis J. Private equity: the bad and the ugly. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:597-610. doi:10.1016/j.det.2023.04.004

- Novice T, Portney D, Eshaq M. Dermatology resident perspectives on practice ownership structures and private equity-backed group practices. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:296-302. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.008

- Cwalina TB, Mazmudar RS, Bordeaux JS, et al. Dermatologist workforce mobility: recent trends and characteristics. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:323-325. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5862

- Oscherwitz ME, Godinich BM, Patel RH, et al. Effects of private equity on dermatologic quality of patient care. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:E100-E102. doi:10.1111/jdv.20191

- Walsh S, Seaton E. Private equity in dermatology: a cloud on the horizon of quality care? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:9-10. doi:10.1111/jdv.20272

- Konda S, Patel S, Francis J. Private equity: the bad and the ugly. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:597-610. doi:10.1016/j.det.2023.04.004

- Novice T, Portney D, Eshaq M. Dermatology resident perspectives on practice ownership structures and private equity-backed group practices. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:296-302. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.008

What Dermatology Residents Need to Know About Joining Group Practices

What Dermatology Residents Need to Know About Joining Group Practices

PRACTICE POINTS

- Finding the right fit in the first position out of dermatology residency can be difficult and feel overwhelming.

- Leaving one practice and joining another is especially common in the first 10 years after residency.

- Asking the right questions can increase the probability of finding the right practice for you and receiving fair compensation.

Differentiation of Latex Allergy From Irritant Contact Dermatitis

Latex allergy is an all-encompassing term used to describe hypersensitivity reactions to products containing natural rubber latex from the Hevea brasiliensis tree and affects approximately 1% to 2% of the general population.1 Although latex gloves are the most widely known culprits, several other commonly used products can contain natural rubber latex, including adhesive tape, balloons, condoms, rubber bands, paint, tourniquets, electrode pads, and Foley catheters.2 The term latex allergy often is used as a general diagnosis, but there are in fact 3 distinct mechanisms by which individuals may develop an adverse reaction to latex-containing products: irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis (type IV hypersensitivity) and true latex allergy (type I hypersensitivity).

Irritant Contact Dermatitis

Irritant contact dermatitis, a nonimmunologic reaction, occurs due to mechanical factors (eg, friction) or contact with chemicals, which can have irritating and dehydrating effects. Individuals with irritant contact dermatitis do not have true latex allergy and will not necessarily develop a reaction to products containing natural rubber latex. Incorrectly attributing these irritant contact dermatitis reactions to latex allergy and simply advising patients to avoid all latex products (eg, use nitrile gloves rather than latex gloves) will not address the underlying problem. Rather, these patients must be informed that the dermatitis is a result of a disruption to the natural, protective skin barrier and not an allergic reaction.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis to rubber is caused by a type IV (delayed) hypersensitivity reaction and is the result of exposure to the accelerators present in rubber products in sensitive individuals. Individuals experiencing this type of reaction typically develop localized erythema, pruritus, and urticarial lesions 48 hours after exposure.3 Incorrectly labeling this problem as latex allergy and recommending nonlatex rubber substitutes (eg, hypoallergenic gloves) likely will not be effective, as these nonlatex replacement products contain the same accelerators as do latex gloves.

True Latex Allergy

The most severe form of latex allergy, often referred to as true latex allergy, is caused by a type I (immediate) hypersensitivity reaction mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. Individuals experiencing this type of reaction have a systemic response to latex proteins that may result in fulminant anaphylaxis. Individuals with true latex allergy must absolutely avoid latex products, and substituting nonlatex products is the most effective approach.

Latex Reactions in Medical Practice

The varying propensity of certain populations to develop latex allergy has been well documented; for example, the prevalence of hypersensitivity in patients with spina bifida ranges from 20% to 65%, figures that are much higher than those reported in the general population.3 This hypersensitivity in patients with spina bifida most likely results from repeated exposure to latex products during corrective surgeries and diagnostic procedures early in life. Atopic individuals, such as those with allergic rhinitis, eczema, and asthma, have a 4-fold increased risk for developing latex allergy compared to nonatopic individuals.4 The risk of latex allergy among health care workers is increased due to increased exposure to rubber products. One study found that the risk of latex sensitization among health care workers exposed to products containing latex was 4.3%, while the risk in the general population was only 1.37%.1 Those at highest risk for sensitization include dental assistants, operating room personnel, hospital housekeeping staff, and paramedics or emergency medical technicians.3 However, sensitization documented on laboratory assessment does not reliably correlate with symptomatic allergy, as many patients with a positive IgE test do not show clinical symptoms. Schmid et al4 demonstrated that a 1.3% prevalence of clinically symptomatic latex allergy among health care workers may approximate the prevalence of latex allergy in the general population. In a study by Brown et al,5 although 12.5% of anesthesiologists were found to be sensitized to latex, only 2.4% had clinically symptomatic allergic reactions.

Testing for Latex Allergy

Several diagnostic tests are available to establish a diagnosis of type I sensitization or true latex allergy. Skin prick testing is an in vivo assay and is the gold standard for diagnosing IgE-mediated type I hypersensitivity to latex. The test involves pricking the skin of the forearm and applying a commercial extract of nonammoniated latex to monitor for development of a wheal within several minutes. The skin prick test should be performed in a health care setting equipped with oxygen, epinephrine, and latex-free resuscitation equipment in case of anaphylaxis following exposure. Although latex skin prick testing is the gold standard, it is rarely performed in the United States because there is no US Food and Drug Administration–approved natural rubber latex reagent.3 Consequently, physicians who wish to perform skin prick testing for latex allergy are forced to develop improvised reagents from the H brasiliensis tree itself or from highly allergenic latex gloves. Standardized latex allergens are commercially available in Europe.

The most noninvasive method of latex allergy testing is an in vitro assay for latex-specific IgE antibodies, which can be detected by either a radioallergosorbent test (RAST) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The presence of antilatex IgE antibodies confirms sensitization but does not necessarily mean the patient will develop a symptomatic reaction following exposure. Due to the unavailability of a standardized reagent for the skin prick test in the United States, evaluation of latex-specific serum IgE levels may be the best alternative. While the skin prick test has the highest sensitivity, the sensitivity and specificity of latex-specific serum IgE testing are 50% to 90% and 80% to 87%, respectively.6

The wear test (also known as the use or glove provocation test), can be used to diagnose clinically symptomatic latex allergy when there is a discrepancy between the patient’s clinical history and results from skin prick or serum IgE antibody testing. To perform the wear test, place a natural rubber latex glove on one of the patient’s fingers for 15 minutes and monitor the area for development of urticaria. If there is no evidence of allergic reaction within 15 minutes, place the glove on the whole hand for an additional 15 minutes. The patient is said to be nonreactive if a latex glove can be placed on the entire hand for 15 minutes without evidence of reaction.3

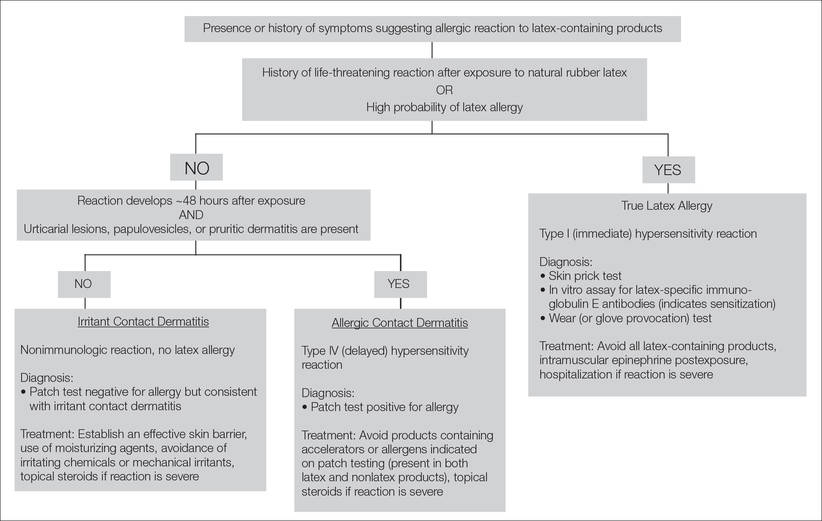

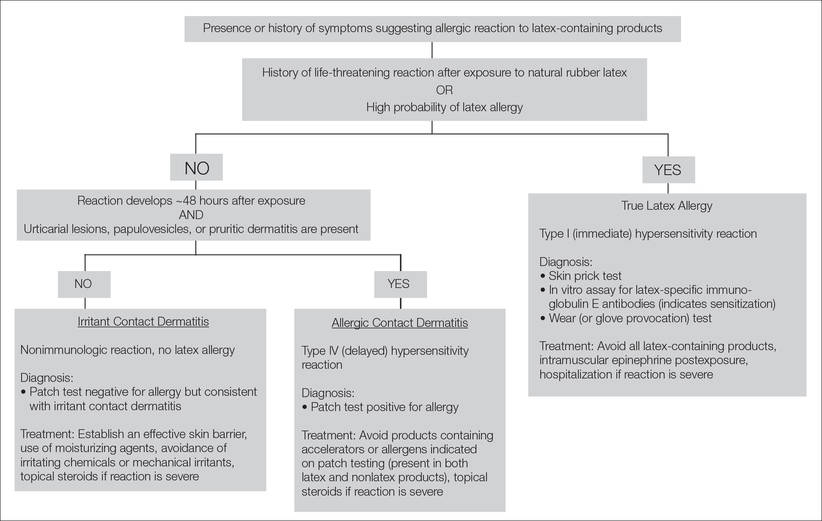

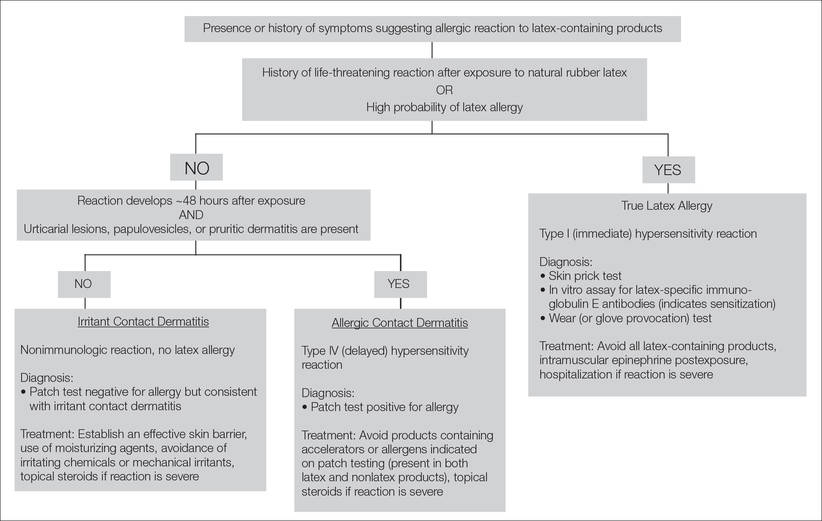

Lastly, patch testing can differentiate between irritant contact and allergic contact (type IV hypersensitivity) dermatitis. Apply a small amount of each substance of interest onto a separate disc and place the discs in direct contact with the skin using hypoallergenic tape. With type IV latex hypersensitivity, the skin underneath the disc will become erythematous with developing papulovesicles, starting between 2 and 5 days after exposure. The Figure outlines the differentiation of true latex allergy from irritant and allergic contact dermatitis and identifies methods for making these diagnoses.

General Medical Protocol With Latex Reactions

To reduce the incidence of latex allergic reactions among health care workers and patients, Kumar2 recommends putting a protocol in place to document steps in preventing, diagnosing, and treating latex allergy. This protocol includes employee and patient education about the risks for developing latex allergy and the signs and symptoms of a reaction; available diagnostic testing; and alternative products (eg, hypoallergenic gloves) that are available to individuals with a known or suspected allergy. At-risk health care workers who have not been sensitized should be advised to avoid latex-containing products.3 Routine questioning and diagnostic testing may be necessary as part of every preoperative assessment, as there have been reported cases of anaphylaxis in patients with undocumented allergies.7 Anaphylaxis caused by latex allergy is the second leading cause of perioperative anaphylaxis, accounting for as many as 20% of cases.8 With the use of preventative measures and early identification of at-risk patients, the incidence of latex-related anaphylaxis is decreasing.8 Ascertaining valuable information about the patient’s medical history, such as known allergies to foods that have cross-reactivity to latex (eg, bananas, mango, kiwi, avocado), is one simple way of identifying a patient who should be tested for possible underlying latex allergy.8 Total avoidance of latex-containing products (eg, in the workplace) can further reduce the incidence of allergic reactions by decreasing primary sensitization and risk of exposure.

Conclusion

Patients claiming to be allergic to latex without documentation should be tested. The diagnostic testing available in the United States includes patch testing, wear (or glove provocation) testing, or assessment of IgE antibody titer. Accurate differentiation among irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, and true latex allergy is paramount for properly educating patients and effectively treating these conditions. Additionally, distinguishing patients with true latex allergy from those who have been misdiagnosed can save resources and reduce health care costs.

- Bousquet J, Flahault A, Vandenplas O, et al. Natural rubber latex allergy among health care workers: a systematic review of the evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:447-454.

- Kumar RP. Latex allergy in clinical practice. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:66-70.

- Taylor JS, Erkek E. Latex allergy: diagnosis and management. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:289-301.

- Schmid K, Christoph Broding H, Niklas D, et al. Latex sensitization in dental students using powder-free gloves low in latex protein: a cross-sectional study. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:103-108.

- Brown RH, Schauble JF, Hamilton RG. Prevalence of latex allergy among anesthesiologists: identification of sensitized but asymptomatic individuals. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:292-299.

- Pollart SM, Warniment C, Mori T. Latex allergy. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:1413-1418.

- Duger C, Kol IO, Kaygusuz K, et al. A perioperative anaphylactic reaction caused by latex in a patient with no history of allergy. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2012;16:71-73.

- Hepner DL, Castells MC. Anaphylaxis during the perioperative period. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1381-1395.

Latex allergy is an all-encompassing term used to describe hypersensitivity reactions to products containing natural rubber latex from the Hevea brasiliensis tree and affects approximately 1% to 2% of the general population.1 Although latex gloves are the most widely known culprits, several other commonly used products can contain natural rubber latex, including adhesive tape, balloons, condoms, rubber bands, paint, tourniquets, electrode pads, and Foley catheters.2 The term latex allergy often is used as a general diagnosis, but there are in fact 3 distinct mechanisms by which individuals may develop an adverse reaction to latex-containing products: irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis (type IV hypersensitivity) and true latex allergy (type I hypersensitivity).

Irritant Contact Dermatitis

Irritant contact dermatitis, a nonimmunologic reaction, occurs due to mechanical factors (eg, friction) or contact with chemicals, which can have irritating and dehydrating effects. Individuals with irritant contact dermatitis do not have true latex allergy and will not necessarily develop a reaction to products containing natural rubber latex. Incorrectly attributing these irritant contact dermatitis reactions to latex allergy and simply advising patients to avoid all latex products (eg, use nitrile gloves rather than latex gloves) will not address the underlying problem. Rather, these patients must be informed that the dermatitis is a result of a disruption to the natural, protective skin barrier and not an allergic reaction.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis to rubber is caused by a type IV (delayed) hypersensitivity reaction and is the result of exposure to the accelerators present in rubber products in sensitive individuals. Individuals experiencing this type of reaction typically develop localized erythema, pruritus, and urticarial lesions 48 hours after exposure.3 Incorrectly labeling this problem as latex allergy and recommending nonlatex rubber substitutes (eg, hypoallergenic gloves) likely will not be effective, as these nonlatex replacement products contain the same accelerators as do latex gloves.

True Latex Allergy

The most severe form of latex allergy, often referred to as true latex allergy, is caused by a type I (immediate) hypersensitivity reaction mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. Individuals experiencing this type of reaction have a systemic response to latex proteins that may result in fulminant anaphylaxis. Individuals with true latex allergy must absolutely avoid latex products, and substituting nonlatex products is the most effective approach.

Latex Reactions in Medical Practice

The varying propensity of certain populations to develop latex allergy has been well documented; for example, the prevalence of hypersensitivity in patients with spina bifida ranges from 20% to 65%, figures that are much higher than those reported in the general population.3 This hypersensitivity in patients with spina bifida most likely results from repeated exposure to latex products during corrective surgeries and diagnostic procedures early in life. Atopic individuals, such as those with allergic rhinitis, eczema, and asthma, have a 4-fold increased risk for developing latex allergy compared to nonatopic individuals.4 The risk of latex allergy among health care workers is increased due to increased exposure to rubber products. One study found that the risk of latex sensitization among health care workers exposed to products containing latex was 4.3%, while the risk in the general population was only 1.37%.1 Those at highest risk for sensitization include dental assistants, operating room personnel, hospital housekeeping staff, and paramedics or emergency medical technicians.3 However, sensitization documented on laboratory assessment does not reliably correlate with symptomatic allergy, as many patients with a positive IgE test do not show clinical symptoms. Schmid et al4 demonstrated that a 1.3% prevalence of clinically symptomatic latex allergy among health care workers may approximate the prevalence of latex allergy in the general population. In a study by Brown et al,5 although 12.5% of anesthesiologists were found to be sensitized to latex, only 2.4% had clinically symptomatic allergic reactions.

Testing for Latex Allergy

Several diagnostic tests are available to establish a diagnosis of type I sensitization or true latex allergy. Skin prick testing is an in vivo assay and is the gold standard for diagnosing IgE-mediated type I hypersensitivity to latex. The test involves pricking the skin of the forearm and applying a commercial extract of nonammoniated latex to monitor for development of a wheal within several minutes. The skin prick test should be performed in a health care setting equipped with oxygen, epinephrine, and latex-free resuscitation equipment in case of anaphylaxis following exposure. Although latex skin prick testing is the gold standard, it is rarely performed in the United States because there is no US Food and Drug Administration–approved natural rubber latex reagent.3 Consequently, physicians who wish to perform skin prick testing for latex allergy are forced to develop improvised reagents from the H brasiliensis tree itself or from highly allergenic latex gloves. Standardized latex allergens are commercially available in Europe.

The most noninvasive method of latex allergy testing is an in vitro assay for latex-specific IgE antibodies, which can be detected by either a radioallergosorbent test (RAST) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The presence of antilatex IgE antibodies confirms sensitization but does not necessarily mean the patient will develop a symptomatic reaction following exposure. Due to the unavailability of a standardized reagent for the skin prick test in the United States, evaluation of latex-specific serum IgE levels may be the best alternative. While the skin prick test has the highest sensitivity, the sensitivity and specificity of latex-specific serum IgE testing are 50% to 90% and 80% to 87%, respectively.6

The wear test (also known as the use or glove provocation test), can be used to diagnose clinically symptomatic latex allergy when there is a discrepancy between the patient’s clinical history and results from skin prick or serum IgE antibody testing. To perform the wear test, place a natural rubber latex glove on one of the patient’s fingers for 15 minutes and monitor the area for development of urticaria. If there is no evidence of allergic reaction within 15 minutes, place the glove on the whole hand for an additional 15 minutes. The patient is said to be nonreactive if a latex glove can be placed on the entire hand for 15 minutes without evidence of reaction.3

Lastly, patch testing can differentiate between irritant contact and allergic contact (type IV hypersensitivity) dermatitis. Apply a small amount of each substance of interest onto a separate disc and place the discs in direct contact with the skin using hypoallergenic tape. With type IV latex hypersensitivity, the skin underneath the disc will become erythematous with developing papulovesicles, starting between 2 and 5 days after exposure. The Figure outlines the differentiation of true latex allergy from irritant and allergic contact dermatitis and identifies methods for making these diagnoses.

General Medical Protocol With Latex Reactions

To reduce the incidence of latex allergic reactions among health care workers and patients, Kumar2 recommends putting a protocol in place to document steps in preventing, diagnosing, and treating latex allergy. This protocol includes employee and patient education about the risks for developing latex allergy and the signs and symptoms of a reaction; available diagnostic testing; and alternative products (eg, hypoallergenic gloves) that are available to individuals with a known or suspected allergy. At-risk health care workers who have not been sensitized should be advised to avoid latex-containing products.3 Routine questioning and diagnostic testing may be necessary as part of every preoperative assessment, as there have been reported cases of anaphylaxis in patients with undocumented allergies.7 Anaphylaxis caused by latex allergy is the second leading cause of perioperative anaphylaxis, accounting for as many as 20% of cases.8 With the use of preventative measures and early identification of at-risk patients, the incidence of latex-related anaphylaxis is decreasing.8 Ascertaining valuable information about the patient’s medical history, such as known allergies to foods that have cross-reactivity to latex (eg, bananas, mango, kiwi, avocado), is one simple way of identifying a patient who should be tested for possible underlying latex allergy.8 Total avoidance of latex-containing products (eg, in the workplace) can further reduce the incidence of allergic reactions by decreasing primary sensitization and risk of exposure.

Conclusion

Patients claiming to be allergic to latex without documentation should be tested. The diagnostic testing available in the United States includes patch testing, wear (or glove provocation) testing, or assessment of IgE antibody titer. Accurate differentiation among irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, and true latex allergy is paramount for properly educating patients and effectively treating these conditions. Additionally, distinguishing patients with true latex allergy from those who have been misdiagnosed can save resources and reduce health care costs.

Latex allergy is an all-encompassing term used to describe hypersensitivity reactions to products containing natural rubber latex from the Hevea brasiliensis tree and affects approximately 1% to 2% of the general population.1 Although latex gloves are the most widely known culprits, several other commonly used products can contain natural rubber latex, including adhesive tape, balloons, condoms, rubber bands, paint, tourniquets, electrode pads, and Foley catheters.2 The term latex allergy often is used as a general diagnosis, but there are in fact 3 distinct mechanisms by which individuals may develop an adverse reaction to latex-containing products: irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis (type IV hypersensitivity) and true latex allergy (type I hypersensitivity).

Irritant Contact Dermatitis