User login

Vitamin D pills do not alter kidney function in prediabetes

However, most of these adults with prediabetes plus obesity or overweight also had sufficient serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) and a low risk for adverse kidney outcomes at study entry.

“The benefits of vitamin D might be greater in people with low blood vitamin D levels and/or reduced kidney function,” lead author Sun H. Kim, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, speculated in a statement from the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was published online August 6 in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

“The D2d study is unique because we recruited individuals with high-risk prediabetes, having two out of three abnormal glucose values, and we recruited more than 2,000 participants, representing the largest vitamin D diabetes prevention trial to date,” Dr. Kim pointed out.

Although the study did not show a benefit of vitamin D supplements on kidney function outcomes, 43% of participants were already taking up to 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily when they entered the study, she noted.

A subgroup analysis of individuals who were not taking vitamin D at study entry found that vitamin D supplements were associated with lowered proteinuria, “which means that it could have a beneficial effect on kidney health,” said Dr. Kim, cautioning that “additional studies are needed to look into this further.”

Effect of vitamin D on three kidney function outcomes

Although low levels of serum 25(OH)D are associated with kidney disease, few trials have evaluated how vitamin D supplements might affect kidney function, Dr. Kim and colleagues write.

The D2d trial, they note, found that vitamin D supplements did not lower the risk of incident diabetes in people with prediabetes recruited from medical centers across the United States, as previously reported in 2019.

However, since then, meta-analyses that included the D2d trial have reported a significant 11%-12% reduction in diabetes risk in people with prediabetes who took vitamin D supplements.

The current secondary analysis of D2d aimed to investigate whether vitamin D supplements affect kidney function in people with prediabetes.

A total of 2,166 participants in D2d with complete kidney function data were included in the analysis.

The three study outcomes were change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from baseline, change in urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) from baseline, and worsening Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) risk score (which takes eGFR and UACR into account).

At baseline, patients were a mean age of 60, had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 32 kg/m2, and 44% were women.

Most (79%) had hypertension, 52% were receiving antihypertensives, and 33% were receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Participants had a mean serum 25(OH) level of 28 ng/mL.

They had a mean eGFR of 87 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a mean UACR of 11 mg/g. Only 10% had a moderate, high, or very high KDIGO risk score.

Participants were randomized to receive a daily gel pill containing 4,000 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or placebo.

Medication adherence was high (83%) in both groups during a median follow-up of 2.9 years.

There was no significant between-group difference in the following kidney function outcomes:

- 28 patients in the vitamin D group and 30 patients in the placebo group had a worsening KDIGO risk score.

- The mean difference in eGFR from baseline was -1.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the vitamin D group and -0.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the placebo group.

- The mean difference in UACR from baseline was 2.7 mg/g in the vitamin D group and 2.0 mg/g in the placebo group.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, most of these adults with prediabetes plus obesity or overweight also had sufficient serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) and a low risk for adverse kidney outcomes at study entry.

“The benefits of vitamin D might be greater in people with low blood vitamin D levels and/or reduced kidney function,” lead author Sun H. Kim, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, speculated in a statement from the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was published online August 6 in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

“The D2d study is unique because we recruited individuals with high-risk prediabetes, having two out of three abnormal glucose values, and we recruited more than 2,000 participants, representing the largest vitamin D diabetes prevention trial to date,” Dr. Kim pointed out.

Although the study did not show a benefit of vitamin D supplements on kidney function outcomes, 43% of participants were already taking up to 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily when they entered the study, she noted.

A subgroup analysis of individuals who were not taking vitamin D at study entry found that vitamin D supplements were associated with lowered proteinuria, “which means that it could have a beneficial effect on kidney health,” said Dr. Kim, cautioning that “additional studies are needed to look into this further.”

Effect of vitamin D on three kidney function outcomes

Although low levels of serum 25(OH)D are associated with kidney disease, few trials have evaluated how vitamin D supplements might affect kidney function, Dr. Kim and colleagues write.

The D2d trial, they note, found that vitamin D supplements did not lower the risk of incident diabetes in people with prediabetes recruited from medical centers across the United States, as previously reported in 2019.

However, since then, meta-analyses that included the D2d trial have reported a significant 11%-12% reduction in diabetes risk in people with prediabetes who took vitamin D supplements.

The current secondary analysis of D2d aimed to investigate whether vitamin D supplements affect kidney function in people with prediabetes.

A total of 2,166 participants in D2d with complete kidney function data were included in the analysis.

The three study outcomes were change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from baseline, change in urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) from baseline, and worsening Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) risk score (which takes eGFR and UACR into account).

At baseline, patients were a mean age of 60, had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 32 kg/m2, and 44% were women.

Most (79%) had hypertension, 52% were receiving antihypertensives, and 33% were receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Participants had a mean serum 25(OH) level of 28 ng/mL.

They had a mean eGFR of 87 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a mean UACR of 11 mg/g. Only 10% had a moderate, high, or very high KDIGO risk score.

Participants were randomized to receive a daily gel pill containing 4,000 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or placebo.

Medication adherence was high (83%) in both groups during a median follow-up of 2.9 years.

There was no significant between-group difference in the following kidney function outcomes:

- 28 patients in the vitamin D group and 30 patients in the placebo group had a worsening KDIGO risk score.

- The mean difference in eGFR from baseline was -1.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the vitamin D group and -0.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the placebo group.

- The mean difference in UACR from baseline was 2.7 mg/g in the vitamin D group and 2.0 mg/g in the placebo group.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, most of these adults with prediabetes plus obesity or overweight also had sufficient serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) and a low risk for adverse kidney outcomes at study entry.

“The benefits of vitamin D might be greater in people with low blood vitamin D levels and/or reduced kidney function,” lead author Sun H. Kim, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, speculated in a statement from the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was published online August 6 in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

“The D2d study is unique because we recruited individuals with high-risk prediabetes, having two out of three abnormal glucose values, and we recruited more than 2,000 participants, representing the largest vitamin D diabetes prevention trial to date,” Dr. Kim pointed out.

Although the study did not show a benefit of vitamin D supplements on kidney function outcomes, 43% of participants were already taking up to 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily when they entered the study, she noted.

A subgroup analysis of individuals who were not taking vitamin D at study entry found that vitamin D supplements were associated with lowered proteinuria, “which means that it could have a beneficial effect on kidney health,” said Dr. Kim, cautioning that “additional studies are needed to look into this further.”

Effect of vitamin D on three kidney function outcomes

Although low levels of serum 25(OH)D are associated with kidney disease, few trials have evaluated how vitamin D supplements might affect kidney function, Dr. Kim and colleagues write.

The D2d trial, they note, found that vitamin D supplements did not lower the risk of incident diabetes in people with prediabetes recruited from medical centers across the United States, as previously reported in 2019.

However, since then, meta-analyses that included the D2d trial have reported a significant 11%-12% reduction in diabetes risk in people with prediabetes who took vitamin D supplements.

The current secondary analysis of D2d aimed to investigate whether vitamin D supplements affect kidney function in people with prediabetes.

A total of 2,166 participants in D2d with complete kidney function data were included in the analysis.

The three study outcomes were change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from baseline, change in urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) from baseline, and worsening Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) risk score (which takes eGFR and UACR into account).

At baseline, patients were a mean age of 60, had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 32 kg/m2, and 44% were women.

Most (79%) had hypertension, 52% were receiving antihypertensives, and 33% were receiving an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Participants had a mean serum 25(OH) level of 28 ng/mL.

They had a mean eGFR of 87 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a mean UACR of 11 mg/g. Only 10% had a moderate, high, or very high KDIGO risk score.

Participants were randomized to receive a daily gel pill containing 4,000 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) or placebo.

Medication adherence was high (83%) in both groups during a median follow-up of 2.9 years.

There was no significant between-group difference in the following kidney function outcomes:

- 28 patients in the vitamin D group and 30 patients in the placebo group had a worsening KDIGO risk score.

- The mean difference in eGFR from baseline was -1.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the vitamin D group and -0.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the placebo group.

- The mean difference in UACR from baseline was 2.7 mg/g in the vitamin D group and 2.0 mg/g in the placebo group.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tackle obesity to drop risk for secondary cardiac event

Patients who had been hospitalized for heart attack or cardiovascular revascularization procedures commonly were overweight (46%) or had obesity (35%), but at a follow-up visit, few had lost weight or planned to do so, according to researchers who conduced a large European study.

The findings emphasize that obesity needs to be recognized as a disease that has to be optimally managed to lessen the risk for a secondary cardiovascular event, the authors stressed.

The study, by Dirk De Bacquer, PhD, professor, department of public health, Ghent (Belgium) University, and colleagues, was published recently in the European Heart Journal – Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes.

The researchers analyzed data from more than 10,000 patients in the EUROASPIRE IV and V studies who were hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and answered a survey 16 months later on average.

Although 20% of the patients with obesity had lost 5% or more of their initial weight, 16% had gained 5% or more of their initial weight.

Notably, “the discharge letter did not record the weight status in a quarter of [the patients with obesity] and a substantial proportion reported to have never been told by a healthcare professional [that they were] overweight,” the investigators wrote.

“It seems,” Dr. De Bacquer and colleagues noted, “that obesity is not considered by physicians as a serious medical problem, which requires attention, recommendations, and obvious advice on personal weight targets.”

However, “the benefits for patients who lost weight in our study, resulting in a healthier cardiovascular risk profile, are really worthwhile,” they pointed out.

Cardiovascular rehabilitation should include weight loss intervention

“The safest and most effective approach for managing body weight” in patients with coronary artery disease and obesity “is adopting a healthy eating pattern and increasing levels of physical activity,” they wrote.

Their findings that “patients who reported reducing their fat and sugar intake, consuming more fruit, vegetables, and fish and doing more regular physical activity, had significant weight loss,” support this.

Dr. De Bacquer and colleagues recommend that cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programs “should include weight loss intervention, including different forms of self-support, as a specific component of a comprehensive intervention to reduce total cardiovascular risk, extend life expectancy, and improve quality of life.”

Clinicians should “consider the incremental value of telehealth intervention as well as recently described pharmacological interventions,” they added, noting that the study did not look at these options or at metabolic surgery.

Invited to comment, one expert pointed out that two new observational studies of metabolic surgery in patients with obesity and coronary artery disease reported positive outcomes.

Another expert took issue with the “patient blaming” tone of the article and the lack of actionable ways to help patients lose weight.

Medical therapy or bariatric surgery as other options?

“The study demonstrated how prevalent obesity is in patients with heart disease“ and “confirmed how difficult it is to achieve weight loss, in particular, in patients with heart disease, where weight loss would be beneficial,” Erik Näslund, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Even though “current guidelines stress weight-loss counseling, some patients actually gained weight,” observed Dr. Näslund, of Danderyd Hospital and Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

On the other hand, patients who lost 5% or more of their initial weight had reduced comorbidities that are associated with cardiovascular disease.

“The best way to achieve long-term weight loss in patients with severe obesity is metabolic (bariatric) surgery,” noted Dr. Näslund, who was not involved in the study. “There are now two recent papers in the journal Circulation that demonstrate that metabolic surgery has a role in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with severe obesity” – one study from Dr. Näslund’s group (Circulation. 2021;143:1458-67), as previously reported, and one study from researchers in Ontario, Canada (Circulation. 2021;143:1468-80).

However, those were observational studies, and the findings would need to be confirmed in a randomized clinical trial before they could be used as recommended practice of care, he cautioned. In addition, most patients in the current study would not fulfill the minimum body weight criteria for metabolic surgery.

“Therefore, there is a need for intensified medical therapy for these patients,” as another treatment option, said Dr. Näslund.

“It would be interesting,” he speculated, “to study how the new glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist therapies could work in this setting as a weight loss agent and perhaps have a positive independent cardiovascular benefit.”

Obesity is a disease; clinicians need to be respectful

Meanwhile, Obesity Society fellow and spokesperson Fatima Cody Stanford, MD, said in an interview that she didn’t think the language and tone of the article was respectful for patients with obesity, and the researchers “talked about the old narrative of how we support patients with obesity.”

Lifestyle modification can be at the core of treatment, but medication or bariatric surgery may be other options to “help patients get to their best selves.

“Patients with obesity deserve to be cared for and treated with respect,” said Dr. Stanford, an obesity medicine physician scientist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Treatment needs to be individualized and clinicians need to listen to patient concerns. For example, a patient with obesity may not be able to follow advice to walk more. “I can barely stand up,” one patient with obesity and osteoarthritis told Dr. Stanford.

And patients’ insurance may not cover cardiac rehabilitation – especially patients from racial minorities or those with lower socioeconomic status, she noted.

“My feeling has always been that it is important to be respectful to all patients,” Dr. Näslund agreed. “I do agree that we need to recognize obesity as a chronic disease, and the paper in EHJ demonstrates this, as obesity was not registered in many of the discharge notes.

“If we as healthcare workers measured a weight of our patients the same way that we take a blood pressure,” he said, “perhaps the [stigma] of obesity would be reduced.”

Study findings

The researchers examined pooled data from EUROASPIRE IV (2012-13) and EUROASPIRE V (2016-17) surveys of patients who were overweight or had obesity who had been discharged from hospital after MI, CABG, or PCI to determine if they had received lifestyle advice for weight loss, if they had acted on this advice, and if losing weight altered their cardiovascular disease risk factors.

They identified 10,507 adult patients in 29 mainly European countries who had complete survey data.

The mean age of the patients was 63 at the time of their hospitalization; 25% were women. Many had hypertension (66%-88%), dyslipidemia (69%-80%), or diabetes (16%-37%).

The prevalence of obesity varied from 8% to 46% in men and from 18% to 57% in women, in different countries. Patients with obesity had a mean body weight of 97 kg (213 pounds).

One of the most “striking” findings was the “apparent lack of motivation” to lose weight, Dr. De Bacquer and colleagues wrote. Half of the patients with obesity had not attempted to lose weight in the month before the follow-up visit and most did not plan to do so in the following month.

Goal setting is an important aspect of behavior modification techniques, they wrote, yet 7% of the patients did not know their body weight and 21% did not have an optimal weight target.

Half of the patients had been advised to follow a cardiac rehabilitation program and two-thirds had been advised to follow dietary recommendations and move more.

Those who made positive dietary changes and were more physically active were more likely to lose at least 5% of their weight.

And patients who lost at least 5% of their initial weight were less likely to have hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes compared with patients who had gained this much weight, which “is likely to translate into improved prognosis on the long term,” the authors wrote.

EUROASPIRE IV and V were supported through research grants to the European Society of Cardiology from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Emea Sarl, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche, and Merck, Sharp & Dohme (EUROASPIRE IV) and Amarin, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi, Ferrer, and Novo Nordisk (EUROASPIRE V). Dr. De Bacquer, Dr. Näslund, and Dr. Stanford have no disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who had been hospitalized for heart attack or cardiovascular revascularization procedures commonly were overweight (46%) or had obesity (35%), but at a follow-up visit, few had lost weight or planned to do so, according to researchers who conduced a large European study.

The findings emphasize that obesity needs to be recognized as a disease that has to be optimally managed to lessen the risk for a secondary cardiovascular event, the authors stressed.

The study, by Dirk De Bacquer, PhD, professor, department of public health, Ghent (Belgium) University, and colleagues, was published recently in the European Heart Journal – Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes.

The researchers analyzed data from more than 10,000 patients in the EUROASPIRE IV and V studies who were hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and answered a survey 16 months later on average.

Although 20% of the patients with obesity had lost 5% or more of their initial weight, 16% had gained 5% or more of their initial weight.

Notably, “the discharge letter did not record the weight status in a quarter of [the patients with obesity] and a substantial proportion reported to have never been told by a healthcare professional [that they were] overweight,” the investigators wrote.

“It seems,” Dr. De Bacquer and colleagues noted, “that obesity is not considered by physicians as a serious medical problem, which requires attention, recommendations, and obvious advice on personal weight targets.”

However, “the benefits for patients who lost weight in our study, resulting in a healthier cardiovascular risk profile, are really worthwhile,” they pointed out.

Cardiovascular rehabilitation should include weight loss intervention

“The safest and most effective approach for managing body weight” in patients with coronary artery disease and obesity “is adopting a healthy eating pattern and increasing levels of physical activity,” they wrote.

Their findings that “patients who reported reducing their fat and sugar intake, consuming more fruit, vegetables, and fish and doing more regular physical activity, had significant weight loss,” support this.

Dr. De Bacquer and colleagues recommend that cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programs “should include weight loss intervention, including different forms of self-support, as a specific component of a comprehensive intervention to reduce total cardiovascular risk, extend life expectancy, and improve quality of life.”

Clinicians should “consider the incremental value of telehealth intervention as well as recently described pharmacological interventions,” they added, noting that the study did not look at these options or at metabolic surgery.

Invited to comment, one expert pointed out that two new observational studies of metabolic surgery in patients with obesity and coronary artery disease reported positive outcomes.

Another expert took issue with the “patient blaming” tone of the article and the lack of actionable ways to help patients lose weight.

Medical therapy or bariatric surgery as other options?

“The study demonstrated how prevalent obesity is in patients with heart disease“ and “confirmed how difficult it is to achieve weight loss, in particular, in patients with heart disease, where weight loss would be beneficial,” Erik Näslund, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Even though “current guidelines stress weight-loss counseling, some patients actually gained weight,” observed Dr. Näslund, of Danderyd Hospital and Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

On the other hand, patients who lost 5% or more of their initial weight had reduced comorbidities that are associated with cardiovascular disease.

“The best way to achieve long-term weight loss in patients with severe obesity is metabolic (bariatric) surgery,” noted Dr. Näslund, who was not involved in the study. “There are now two recent papers in the journal Circulation that demonstrate that metabolic surgery has a role in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with severe obesity” – one study from Dr. Näslund’s group (Circulation. 2021;143:1458-67), as previously reported, and one study from researchers in Ontario, Canada (Circulation. 2021;143:1468-80).

However, those were observational studies, and the findings would need to be confirmed in a randomized clinical trial before they could be used as recommended practice of care, he cautioned. In addition, most patients in the current study would not fulfill the minimum body weight criteria for metabolic surgery.

“Therefore, there is a need for intensified medical therapy for these patients,” as another treatment option, said Dr. Näslund.

“It would be interesting,” he speculated, “to study how the new glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist therapies could work in this setting as a weight loss agent and perhaps have a positive independent cardiovascular benefit.”

Obesity is a disease; clinicians need to be respectful

Meanwhile, Obesity Society fellow and spokesperson Fatima Cody Stanford, MD, said in an interview that she didn’t think the language and tone of the article was respectful for patients with obesity, and the researchers “talked about the old narrative of how we support patients with obesity.”

Lifestyle modification can be at the core of treatment, but medication or bariatric surgery may be other options to “help patients get to their best selves.

“Patients with obesity deserve to be cared for and treated with respect,” said Dr. Stanford, an obesity medicine physician scientist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Treatment needs to be individualized and clinicians need to listen to patient concerns. For example, a patient with obesity may not be able to follow advice to walk more. “I can barely stand up,” one patient with obesity and osteoarthritis told Dr. Stanford.

And patients’ insurance may not cover cardiac rehabilitation – especially patients from racial minorities or those with lower socioeconomic status, she noted.

“My feeling has always been that it is important to be respectful to all patients,” Dr. Näslund agreed. “I do agree that we need to recognize obesity as a chronic disease, and the paper in EHJ demonstrates this, as obesity was not registered in many of the discharge notes.

“If we as healthcare workers measured a weight of our patients the same way that we take a blood pressure,” he said, “perhaps the [stigma] of obesity would be reduced.”

Study findings

The researchers examined pooled data from EUROASPIRE IV (2012-13) and EUROASPIRE V (2016-17) surveys of patients who were overweight or had obesity who had been discharged from hospital after MI, CABG, or PCI to determine if they had received lifestyle advice for weight loss, if they had acted on this advice, and if losing weight altered their cardiovascular disease risk factors.

They identified 10,507 adult patients in 29 mainly European countries who had complete survey data.

The mean age of the patients was 63 at the time of their hospitalization; 25% were women. Many had hypertension (66%-88%), dyslipidemia (69%-80%), or diabetes (16%-37%).

The prevalence of obesity varied from 8% to 46% in men and from 18% to 57% in women, in different countries. Patients with obesity had a mean body weight of 97 kg (213 pounds).

One of the most “striking” findings was the “apparent lack of motivation” to lose weight, Dr. De Bacquer and colleagues wrote. Half of the patients with obesity had not attempted to lose weight in the month before the follow-up visit and most did not plan to do so in the following month.

Goal setting is an important aspect of behavior modification techniques, they wrote, yet 7% of the patients did not know their body weight and 21% did not have an optimal weight target.

Half of the patients had been advised to follow a cardiac rehabilitation program and two-thirds had been advised to follow dietary recommendations and move more.

Those who made positive dietary changes and were more physically active were more likely to lose at least 5% of their weight.

And patients who lost at least 5% of their initial weight were less likely to have hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes compared with patients who had gained this much weight, which “is likely to translate into improved prognosis on the long term,” the authors wrote.

EUROASPIRE IV and V were supported through research grants to the European Society of Cardiology from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Emea Sarl, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche, and Merck, Sharp & Dohme (EUROASPIRE IV) and Amarin, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi, Ferrer, and Novo Nordisk (EUROASPIRE V). Dr. De Bacquer, Dr. Näslund, and Dr. Stanford have no disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who had been hospitalized for heart attack or cardiovascular revascularization procedures commonly were overweight (46%) or had obesity (35%), but at a follow-up visit, few had lost weight or planned to do so, according to researchers who conduced a large European study.

The findings emphasize that obesity needs to be recognized as a disease that has to be optimally managed to lessen the risk for a secondary cardiovascular event, the authors stressed.

The study, by Dirk De Bacquer, PhD, professor, department of public health, Ghent (Belgium) University, and colleagues, was published recently in the European Heart Journal – Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes.

The researchers analyzed data from more than 10,000 patients in the EUROASPIRE IV and V studies who were hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and answered a survey 16 months later on average.

Although 20% of the patients with obesity had lost 5% or more of their initial weight, 16% had gained 5% or more of their initial weight.

Notably, “the discharge letter did not record the weight status in a quarter of [the patients with obesity] and a substantial proportion reported to have never been told by a healthcare professional [that they were] overweight,” the investigators wrote.

“It seems,” Dr. De Bacquer and colleagues noted, “that obesity is not considered by physicians as a serious medical problem, which requires attention, recommendations, and obvious advice on personal weight targets.”

However, “the benefits for patients who lost weight in our study, resulting in a healthier cardiovascular risk profile, are really worthwhile,” they pointed out.

Cardiovascular rehabilitation should include weight loss intervention

“The safest and most effective approach for managing body weight” in patients with coronary artery disease and obesity “is adopting a healthy eating pattern and increasing levels of physical activity,” they wrote.

Their findings that “patients who reported reducing their fat and sugar intake, consuming more fruit, vegetables, and fish and doing more regular physical activity, had significant weight loss,” support this.

Dr. De Bacquer and colleagues recommend that cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programs “should include weight loss intervention, including different forms of self-support, as a specific component of a comprehensive intervention to reduce total cardiovascular risk, extend life expectancy, and improve quality of life.”

Clinicians should “consider the incremental value of telehealth intervention as well as recently described pharmacological interventions,” they added, noting that the study did not look at these options or at metabolic surgery.

Invited to comment, one expert pointed out that two new observational studies of metabolic surgery in patients with obesity and coronary artery disease reported positive outcomes.

Another expert took issue with the “patient blaming” tone of the article and the lack of actionable ways to help patients lose weight.

Medical therapy or bariatric surgery as other options?

“The study demonstrated how prevalent obesity is in patients with heart disease“ and “confirmed how difficult it is to achieve weight loss, in particular, in patients with heart disease, where weight loss would be beneficial,” Erik Näslund, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Even though “current guidelines stress weight-loss counseling, some patients actually gained weight,” observed Dr. Näslund, of Danderyd Hospital and Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

On the other hand, patients who lost 5% or more of their initial weight had reduced comorbidities that are associated with cardiovascular disease.

“The best way to achieve long-term weight loss in patients with severe obesity is metabolic (bariatric) surgery,” noted Dr. Näslund, who was not involved in the study. “There are now two recent papers in the journal Circulation that demonstrate that metabolic surgery has a role in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with severe obesity” – one study from Dr. Näslund’s group (Circulation. 2021;143:1458-67), as previously reported, and one study from researchers in Ontario, Canada (Circulation. 2021;143:1468-80).

However, those were observational studies, and the findings would need to be confirmed in a randomized clinical trial before they could be used as recommended practice of care, he cautioned. In addition, most patients in the current study would not fulfill the minimum body weight criteria for metabolic surgery.

“Therefore, there is a need for intensified medical therapy for these patients,” as another treatment option, said Dr. Näslund.

“It would be interesting,” he speculated, “to study how the new glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist therapies could work in this setting as a weight loss agent and perhaps have a positive independent cardiovascular benefit.”

Obesity is a disease; clinicians need to be respectful

Meanwhile, Obesity Society fellow and spokesperson Fatima Cody Stanford, MD, said in an interview that she didn’t think the language and tone of the article was respectful for patients with obesity, and the researchers “talked about the old narrative of how we support patients with obesity.”

Lifestyle modification can be at the core of treatment, but medication or bariatric surgery may be other options to “help patients get to their best selves.

“Patients with obesity deserve to be cared for and treated with respect,” said Dr. Stanford, an obesity medicine physician scientist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Treatment needs to be individualized and clinicians need to listen to patient concerns. For example, a patient with obesity may not be able to follow advice to walk more. “I can barely stand up,” one patient with obesity and osteoarthritis told Dr. Stanford.

And patients’ insurance may not cover cardiac rehabilitation – especially patients from racial minorities or those with lower socioeconomic status, she noted.

“My feeling has always been that it is important to be respectful to all patients,” Dr. Näslund agreed. “I do agree that we need to recognize obesity as a chronic disease, and the paper in EHJ demonstrates this, as obesity was not registered in many of the discharge notes.

“If we as healthcare workers measured a weight of our patients the same way that we take a blood pressure,” he said, “perhaps the [stigma] of obesity would be reduced.”

Study findings

The researchers examined pooled data from EUROASPIRE IV (2012-13) and EUROASPIRE V (2016-17) surveys of patients who were overweight or had obesity who had been discharged from hospital after MI, CABG, or PCI to determine if they had received lifestyle advice for weight loss, if they had acted on this advice, and if losing weight altered their cardiovascular disease risk factors.

They identified 10,507 adult patients in 29 mainly European countries who had complete survey data.

The mean age of the patients was 63 at the time of their hospitalization; 25% were women. Many had hypertension (66%-88%), dyslipidemia (69%-80%), or diabetes (16%-37%).

The prevalence of obesity varied from 8% to 46% in men and from 18% to 57% in women, in different countries. Patients with obesity had a mean body weight of 97 kg (213 pounds).

One of the most “striking” findings was the “apparent lack of motivation” to lose weight, Dr. De Bacquer and colleagues wrote. Half of the patients with obesity had not attempted to lose weight in the month before the follow-up visit and most did not plan to do so in the following month.

Goal setting is an important aspect of behavior modification techniques, they wrote, yet 7% of the patients did not know their body weight and 21% did not have an optimal weight target.

Half of the patients had been advised to follow a cardiac rehabilitation program and two-thirds had been advised to follow dietary recommendations and move more.

Those who made positive dietary changes and were more physically active were more likely to lose at least 5% of their weight.

And patients who lost at least 5% of their initial weight were less likely to have hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes compared with patients who had gained this much weight, which “is likely to translate into improved prognosis on the long term,” the authors wrote.

EUROASPIRE IV and V were supported through research grants to the European Society of Cardiology from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Emea Sarl, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche, and Merck, Sharp & Dohme (EUROASPIRE IV) and Amarin, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi, Ferrer, and Novo Nordisk (EUROASPIRE V). Dr. De Bacquer, Dr. Näslund, and Dr. Stanford have no disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Certain gut bacteria tied to lower risk of diabetes

Having more diverse gut bacteria (greater microbiome richness) and specifically a greater abundance of 12 types of butyrate-producing bacteria were both associated with less insulin resistance and less type 2 diabetes, in a population-based observational study from the Netherlands.

Several studies have reported that there is less microbiome diversity in type 2 diabetes, Zhangling Chen, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues note.

Their study also identified a dozen types of bacteria that ferment dietary fiber (undigested carbohydrates) in the gut to produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid, which may play a role in protection against type 2 diabetes.

“The current study is the first, to our knowledge, to comprehensively investigate the associations between gut microbiome composition [and] type 2 diabetes in a large population-based sample … which we adjusted for a series of key confounders,” the researchers write.

“These findings suggest that higher gut microbial diversity, along with specifically more butyrate-producing bacteria, may play a role in the development of type 2 diabetes, which may help guide future prevention and treatment strategies,” they conclude in their study published online July 29 in JAMA Network Open.

Confirmation of previous work, plus some new findings

The study confirms what many smaller ones have repeatedly shown – that low gut microbiome diversity is associated with increased risks of obesity and type 2 diabetes, Nanette I. Steinle, MD, RDN, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview.

A diet rich in fiber and prebiotics promotes gut biome diversity, added Dr. Steinle, chief of the endocrinology and diabetes section at Maryland Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Baltimore.

The findings add to other research, she noted, such as a prospective trial in which a high-fiber diet induced changes in the gut microbe that were linked to better glycemic regulation (Science. 2018;359:1151-6) and a study of a promising probiotic formula to treat diabetes.

“An important next step,” according to Dr. Steinle, “is to provide interventions like healthy diet or specific fiber types to see what can be done to produce lasting shifts in the gut microbiome and if these shifts result in improved metabolic health.”

Natalia Shulzhenko, MD, PhD, said: “Some of associations of taxa [bacteria groupings] with type 2 diabetes reported by this study are new.”

Dr. Shulzhenko and colleagues recently published a review of the role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology that summarized evidence from 42 human studies as well as preclinical studies and clinical trials of probiotic treatments (EBioMedicine. 2020;51:102590).

“Besides adding new microbes to the list of potential pathobionts [organisms that can cause harm] and beneficial microbes for type 2 diabetes,” the findings by Dr. Chen and colleagues “support a notion that different members of the gut microbial community may have similar effects on type 2 diabetes in different individuals,” commonly known as “functional redundancy,” Dr. Shulzhenko, associate professor, Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine, Oregon State University, Corvallis, pointed out in an email.

Also “in line with previous studies,” the study shows that butyrate-producing bacteria are associated with type 2 diabetes.

She speculated that “these results will probably contribute to the body of knowledge that is needed to develop microbiota-based therapy and diagnostics.”

Which gut bacteria are linked with diabetes?

It is unclear which gut bacteria are associated with the development of type 2 diabetes, Dr. Chen and colleagues write.

To investigate this, they identified 1,418 participants from the Rotterdam Study and 748 participants from the LifeLines-DEEP study enrolled from January 2018 to December 2020. Of these participants, 193 had type 2 diabetes.

The participants provided stool samples that were used to measure gut microbiome composition using the 16S ribosomal RNA method. They also had blood tests to measure glucose and insulin, and researchers collected other demographic and medical data.

Participants in the Rotterdam study were older than in the LifeLines Deep study (mean age, 62 vs. 45 years). Both cohorts included slightly more men than women (58%).

Dr. Chen and colleagues identified 126 (bacteria) genera in the gut microbiome in the Rotterdam study and 184 genera in the LifeLines Deep study.

After correcting for age, sex, smoking, education, physical activity, alcohol intake, daily calories, body mass index, and use of lipid-lowering medication or proton pump inhibitors, higher microbiome diversity was associated with lower insulin resistance and a lower prevalence of type 2 diabetes.

A higher abundance of each of seven types of butyrate-producing bacteria – Christensenellaceae, Christensenellaceae R7 group, Marvinbryantia, Ruminococcaceae UCG-005, Ruminococcaceae UCG-008, Ruminococcaceae UCG-010, and Ruminococcaceae NK4A214 group – was associated with lower insulin resistance, after adjusting for confounders such as diet and medications (all P < .001).

And a higher abundance of each of five other types of butyrate-producing bacteria – Clostridiaceae 1, Peptostreptococcaceae, Clostridium sensu stricto 1, Intestinibacter, and Romboutsia – was associated with less type 2 diabetes (all P < .001).

Study limitations include that gut microbiome composition was determined from stool (fecal) samples, whereas the actual composition varies in different locations along the intestine, and the study also lacked information about butyrate concentrations in stool or blood, the researchers note.

They call for “future research [to] validate the hypothesis of butyrate-producing bacteria affecting glucose metabolism and diabetes risk via production of butyrate.”

The authors and Dr. Shulzhenko have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Steinle has reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health and conducting a study funded by Kowa through the VA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Having more diverse gut bacteria (greater microbiome richness) and specifically a greater abundance of 12 types of butyrate-producing bacteria were both associated with less insulin resistance and less type 2 diabetes, in a population-based observational study from the Netherlands.

Several studies have reported that there is less microbiome diversity in type 2 diabetes, Zhangling Chen, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues note.

Their study also identified a dozen types of bacteria that ferment dietary fiber (undigested carbohydrates) in the gut to produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid, which may play a role in protection against type 2 diabetes.

“The current study is the first, to our knowledge, to comprehensively investigate the associations between gut microbiome composition [and] type 2 diabetes in a large population-based sample … which we adjusted for a series of key confounders,” the researchers write.

“These findings suggest that higher gut microbial diversity, along with specifically more butyrate-producing bacteria, may play a role in the development of type 2 diabetes, which may help guide future prevention and treatment strategies,” they conclude in their study published online July 29 in JAMA Network Open.

Confirmation of previous work, plus some new findings

The study confirms what many smaller ones have repeatedly shown – that low gut microbiome diversity is associated with increased risks of obesity and type 2 diabetes, Nanette I. Steinle, MD, RDN, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview.

A diet rich in fiber and prebiotics promotes gut biome diversity, added Dr. Steinle, chief of the endocrinology and diabetes section at Maryland Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Baltimore.

The findings add to other research, she noted, such as a prospective trial in which a high-fiber diet induced changes in the gut microbe that were linked to better glycemic regulation (Science. 2018;359:1151-6) and a study of a promising probiotic formula to treat diabetes.

“An important next step,” according to Dr. Steinle, “is to provide interventions like healthy diet or specific fiber types to see what can be done to produce lasting shifts in the gut microbiome and if these shifts result in improved metabolic health.”

Natalia Shulzhenko, MD, PhD, said: “Some of associations of taxa [bacteria groupings] with type 2 diabetes reported by this study are new.”

Dr. Shulzhenko and colleagues recently published a review of the role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology that summarized evidence from 42 human studies as well as preclinical studies and clinical trials of probiotic treatments (EBioMedicine. 2020;51:102590).

“Besides adding new microbes to the list of potential pathobionts [organisms that can cause harm] and beneficial microbes for type 2 diabetes,” the findings by Dr. Chen and colleagues “support a notion that different members of the gut microbial community may have similar effects on type 2 diabetes in different individuals,” commonly known as “functional redundancy,” Dr. Shulzhenko, associate professor, Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine, Oregon State University, Corvallis, pointed out in an email.

Also “in line with previous studies,” the study shows that butyrate-producing bacteria are associated with type 2 diabetes.

She speculated that “these results will probably contribute to the body of knowledge that is needed to develop microbiota-based therapy and diagnostics.”

Which gut bacteria are linked with diabetes?

It is unclear which gut bacteria are associated with the development of type 2 diabetes, Dr. Chen and colleagues write.

To investigate this, they identified 1,418 participants from the Rotterdam Study and 748 participants from the LifeLines-DEEP study enrolled from January 2018 to December 2020. Of these participants, 193 had type 2 diabetes.

The participants provided stool samples that were used to measure gut microbiome composition using the 16S ribosomal RNA method. They also had blood tests to measure glucose and insulin, and researchers collected other demographic and medical data.

Participants in the Rotterdam study were older than in the LifeLines Deep study (mean age, 62 vs. 45 years). Both cohorts included slightly more men than women (58%).

Dr. Chen and colleagues identified 126 (bacteria) genera in the gut microbiome in the Rotterdam study and 184 genera in the LifeLines Deep study.

After correcting for age, sex, smoking, education, physical activity, alcohol intake, daily calories, body mass index, and use of lipid-lowering medication or proton pump inhibitors, higher microbiome diversity was associated with lower insulin resistance and a lower prevalence of type 2 diabetes.

A higher abundance of each of seven types of butyrate-producing bacteria – Christensenellaceae, Christensenellaceae R7 group, Marvinbryantia, Ruminococcaceae UCG-005, Ruminococcaceae UCG-008, Ruminococcaceae UCG-010, and Ruminococcaceae NK4A214 group – was associated with lower insulin resistance, after adjusting for confounders such as diet and medications (all P < .001).

And a higher abundance of each of five other types of butyrate-producing bacteria – Clostridiaceae 1, Peptostreptococcaceae, Clostridium sensu stricto 1, Intestinibacter, and Romboutsia – was associated with less type 2 diabetes (all P < .001).

Study limitations include that gut microbiome composition was determined from stool (fecal) samples, whereas the actual composition varies in different locations along the intestine, and the study also lacked information about butyrate concentrations in stool or blood, the researchers note.

They call for “future research [to] validate the hypothesis of butyrate-producing bacteria affecting glucose metabolism and diabetes risk via production of butyrate.”

The authors and Dr. Shulzhenko have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Steinle has reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health and conducting a study funded by Kowa through the VA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Having more diverse gut bacteria (greater microbiome richness) and specifically a greater abundance of 12 types of butyrate-producing bacteria were both associated with less insulin resistance and less type 2 diabetes, in a population-based observational study from the Netherlands.

Several studies have reported that there is less microbiome diversity in type 2 diabetes, Zhangling Chen, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues note.

Their study also identified a dozen types of bacteria that ferment dietary fiber (undigested carbohydrates) in the gut to produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid, which may play a role in protection against type 2 diabetes.

“The current study is the first, to our knowledge, to comprehensively investigate the associations between gut microbiome composition [and] type 2 diabetes in a large population-based sample … which we adjusted for a series of key confounders,” the researchers write.

“These findings suggest that higher gut microbial diversity, along with specifically more butyrate-producing bacteria, may play a role in the development of type 2 diabetes, which may help guide future prevention and treatment strategies,” they conclude in their study published online July 29 in JAMA Network Open.

Confirmation of previous work, plus some new findings

The study confirms what many smaller ones have repeatedly shown – that low gut microbiome diversity is associated with increased risks of obesity and type 2 diabetes, Nanette I. Steinle, MD, RDN, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview.

A diet rich in fiber and prebiotics promotes gut biome diversity, added Dr. Steinle, chief of the endocrinology and diabetes section at Maryland Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Baltimore.

The findings add to other research, she noted, such as a prospective trial in which a high-fiber diet induced changes in the gut microbe that were linked to better glycemic regulation (Science. 2018;359:1151-6) and a study of a promising probiotic formula to treat diabetes.

“An important next step,” according to Dr. Steinle, “is to provide interventions like healthy diet or specific fiber types to see what can be done to produce lasting shifts in the gut microbiome and if these shifts result in improved metabolic health.”

Natalia Shulzhenko, MD, PhD, said: “Some of associations of taxa [bacteria groupings] with type 2 diabetes reported by this study are new.”

Dr. Shulzhenko and colleagues recently published a review of the role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology that summarized evidence from 42 human studies as well as preclinical studies and clinical trials of probiotic treatments (EBioMedicine. 2020;51:102590).

“Besides adding new microbes to the list of potential pathobionts [organisms that can cause harm] and beneficial microbes for type 2 diabetes,” the findings by Dr. Chen and colleagues “support a notion that different members of the gut microbial community may have similar effects on type 2 diabetes in different individuals,” commonly known as “functional redundancy,” Dr. Shulzhenko, associate professor, Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine, Oregon State University, Corvallis, pointed out in an email.

Also “in line with previous studies,” the study shows that butyrate-producing bacteria are associated with type 2 diabetes.

She speculated that “these results will probably contribute to the body of knowledge that is needed to develop microbiota-based therapy and diagnostics.”

Which gut bacteria are linked with diabetes?

It is unclear which gut bacteria are associated with the development of type 2 diabetes, Dr. Chen and colleagues write.

To investigate this, they identified 1,418 participants from the Rotterdam Study and 748 participants from the LifeLines-DEEP study enrolled from January 2018 to December 2020. Of these participants, 193 had type 2 diabetes.

The participants provided stool samples that were used to measure gut microbiome composition using the 16S ribosomal RNA method. They also had blood tests to measure glucose and insulin, and researchers collected other demographic and medical data.

Participants in the Rotterdam study were older than in the LifeLines Deep study (mean age, 62 vs. 45 years). Both cohorts included slightly more men than women (58%).

Dr. Chen and colleagues identified 126 (bacteria) genera in the gut microbiome in the Rotterdam study and 184 genera in the LifeLines Deep study.

After correcting for age, sex, smoking, education, physical activity, alcohol intake, daily calories, body mass index, and use of lipid-lowering medication or proton pump inhibitors, higher microbiome diversity was associated with lower insulin resistance and a lower prevalence of type 2 diabetes.

A higher abundance of each of seven types of butyrate-producing bacteria – Christensenellaceae, Christensenellaceae R7 group, Marvinbryantia, Ruminococcaceae UCG-005, Ruminococcaceae UCG-008, Ruminococcaceae UCG-010, and Ruminococcaceae NK4A214 group – was associated with lower insulin resistance, after adjusting for confounders such as diet and medications (all P < .001).

And a higher abundance of each of five other types of butyrate-producing bacteria – Clostridiaceae 1, Peptostreptococcaceae, Clostridium sensu stricto 1, Intestinibacter, and Romboutsia – was associated with less type 2 diabetes (all P < .001).

Study limitations include that gut microbiome composition was determined from stool (fecal) samples, whereas the actual composition varies in different locations along the intestine, and the study also lacked information about butyrate concentrations in stool or blood, the researchers note.

They call for “future research [to] validate the hypothesis of butyrate-producing bacteria affecting glucose metabolism and diabetes risk via production of butyrate.”

The authors and Dr. Shulzhenko have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Steinle has reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health and conducting a study funded by Kowa through the VA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

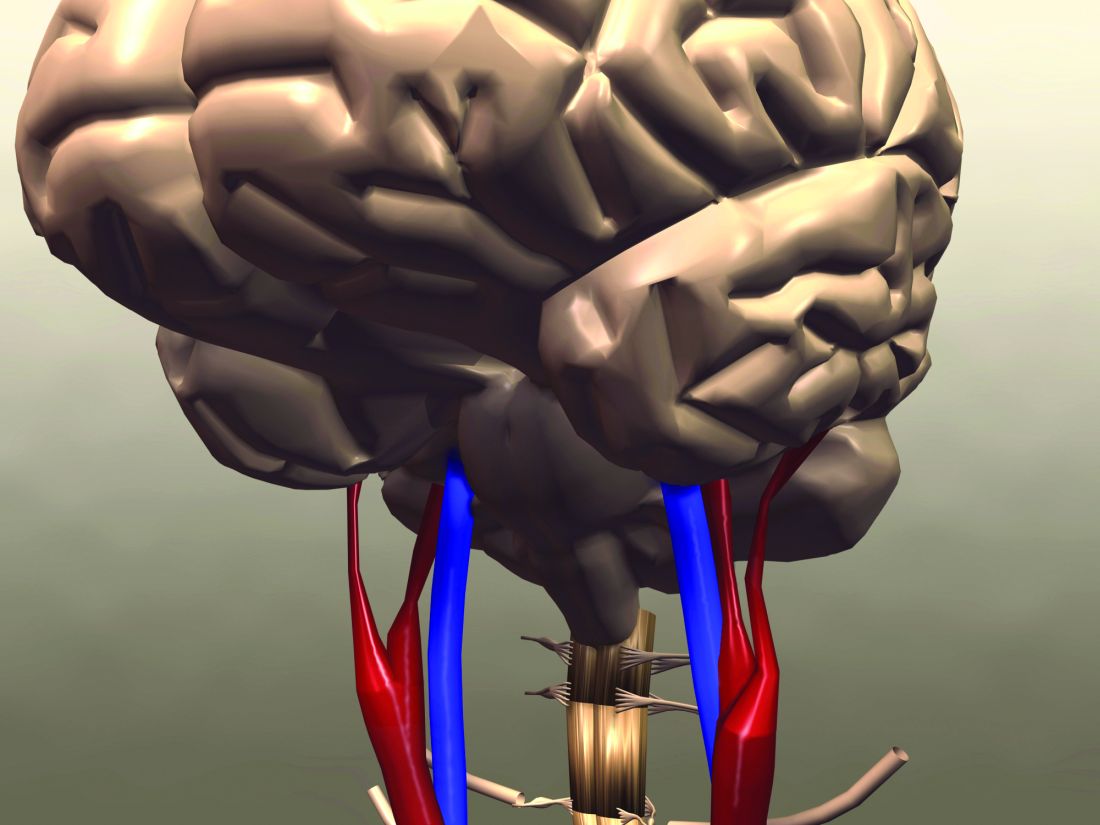

Dapagliflozin safe, protective in advanced kidney disease

Patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (CKD) who were in the DAPA-CKD trial had cardiorenal benefits from dapagliflozin that were similar to those of patients in the overall trial, with no added safety signal.

DAPA-CKD (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease) was a landmark study of more than 4,000 patients with CKD, with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 25-75 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and albuminuria with/without type 2 diabetes.

The primary results showed that patients who received the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin for a median of 2.4 years were significantly less likely to have worsening kidney disease or die from all causes than were patients who received placebo.

“This prespecified subanalysis of people with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 [stage 4 CKD] in the DAPA-CKD study shows first, that in this very vulnerable population, use of the SGLT2 inhibitor is safe,” said Chantal Mathieu, MD, PhD.

Furthermore, there was no signal whatsoever of more adverse events and even a trend to fewer events, she said in an email to this news organization.

The analysis also showed that “although now in small numbers (around 300 each in the treated group vs. placebo group), there is no suggestion that the protective effect of dapagliflozin on the renal and cardiovascular front would not happen in this group” with advanced CKD. The efficacy findings just missed statistical significance, noted Dr. Mathieu, of Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium, who was not involved in the study.

Although dapagliflozin is now approved for treating patients with CKD who are at risk of kidney disease progression (on the basis of the DAPA-CKD results), guidelines have not yet been updated to reflect this, lead investigator Glenn M. Chertow, MD, MPH, of Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization in an email.

“For clinicians,” Dr. Mathieu said, “this is now the absolute reassurance that we do not have to stop an SGLT2 inhibitor in people with eGFR < 30 mL/min for safety reasons and that we should maintain them at these values for renal and cardiovascular protection!

“I absolutely hope labels will change soon to reflect these observations (and indeed movement on that front is happening),” she continued.

“The American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes consensus on glucose-lowering therapies in type 2 diabetes already advocated keeping these agents until eGFR 30 mL/min (on the basis of evidence in 2019),” Dr. Mathieu added, “but this study will probably push the statements even further.”

“Of note,” she pointed out, “at these low eGFRs, the glucose-lowering potential of the SGLT2 inhibitor is negligible.”

Dapagliflozin risks and benefits in advanced CKD

Based on the DAPA-CKD study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine Oct. 8, 2020, the Food and Drug Administration expanded the indication for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in April of 2021.

However, relatively little is known about the safety and efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with advanced CKD, who are particularly vulnerable to cardiovascular events and progressive kidney failure, Dr. Chertow and colleagues wrote.

The DAPA-CKD trial randomized 4,304 patients with CKD 1:1 to dapagliflozin 10 mg/day or placebo, including 624 patients (14%) who had eGFR < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and albuminuria at baseline.

Patients in the subgroup with advanced CKD had a mean age of 62 years, and 37% were female. About two-thirds had type 2 diabetes and about one-third had cardiovascular disease.

A total of 293 patients received dapagliflozin and 331 patients received placebo.

During a median follow-up of 2.4 years, patients who received dapagliflozin as opposed to placebo had a lower risk of the primary efficacy outcome – a composite of a 50% or greater sustained decline in eGFR, end-stage kidney disease, or death from cardiovascular or renal causes (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-1.02).

In secondary efficacy outcomes, patients who received dapagliflozin as opposed to placebo also had a lower risk of the following:

- A renal composite outcome – a ≥ 50% sustained decline in eGFR, end-stage kidney disease, or death from renal causes (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.49-1.02).

- A cardiovascular composite outcome comprising cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.45-1.53).

- All-cause mortality (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.39 to 1.21).

The eGFR slope declined by 2.15 mL/min per 1.73 m2 per year and by 3.38 mL/min per 1.73 m2 per year in the dapagliflozin and placebo groups, respectively (P = .005).

“The trial was not powered to detect a statistically significant difference in the primary and key secondary endpoints in modest-sized subgroups,” the researchers noted.

The researchers limited their safety analysis to serious adverse events or symptoms of volume depletion, kidney-related events, major hypoglycemia, bone fractures, amputations, and potential diabetic ketoacidosis.

There was no evidence of increased risk of these adverse events in patients who received dapagliflozin.

The subanalysis of the DAPA-CKD trial was published July 16 in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Chertow has received fees from AstraZeneca for the DAPA-CKD trial steering committee. The disclosures of the other authors are listed in the article. Dr. Mathieu has served on the advisory panel/speakers bureau for AstraZeneca. Dr. Chertow and Dr. Mathieu also have financial relationships with many other pharmaceutical companies.

Patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (CKD) who were in the DAPA-CKD trial had cardiorenal benefits from dapagliflozin that were similar to those of patients in the overall trial, with no added safety signal.

DAPA-CKD (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease) was a landmark study of more than 4,000 patients with CKD, with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 25-75 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and albuminuria with/without type 2 diabetes.

The primary results showed that patients who received the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin for a median of 2.4 years were significantly less likely to have worsening kidney disease or die from all causes than were patients who received placebo.

“This prespecified subanalysis of people with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 [stage 4 CKD] in the DAPA-CKD study shows first, that in this very vulnerable population, use of the SGLT2 inhibitor is safe,” said Chantal Mathieu, MD, PhD.

Furthermore, there was no signal whatsoever of more adverse events and even a trend to fewer events, she said in an email to this news organization.

The analysis also showed that “although now in small numbers (around 300 each in the treated group vs. placebo group), there is no suggestion that the protective effect of dapagliflozin on the renal and cardiovascular front would not happen in this group” with advanced CKD. The efficacy findings just missed statistical significance, noted Dr. Mathieu, of Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium, who was not involved in the study.

Although dapagliflozin is now approved for treating patients with CKD who are at risk of kidney disease progression (on the basis of the DAPA-CKD results), guidelines have not yet been updated to reflect this, lead investigator Glenn M. Chertow, MD, MPH, of Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization in an email.

“For clinicians,” Dr. Mathieu said, “this is now the absolute reassurance that we do not have to stop an SGLT2 inhibitor in people with eGFR < 30 mL/min for safety reasons and that we should maintain them at these values for renal and cardiovascular protection!

“I absolutely hope labels will change soon to reflect these observations (and indeed movement on that front is happening),” she continued.

“The American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes consensus on glucose-lowering therapies in type 2 diabetes already advocated keeping these agents until eGFR 30 mL/min (on the basis of evidence in 2019),” Dr. Mathieu added, “but this study will probably push the statements even further.”

“Of note,” she pointed out, “at these low eGFRs, the glucose-lowering potential of the SGLT2 inhibitor is negligible.”

Dapagliflozin risks and benefits in advanced CKD

Based on the DAPA-CKD study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine Oct. 8, 2020, the Food and Drug Administration expanded the indication for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in April of 2021.

However, relatively little is known about the safety and efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with advanced CKD, who are particularly vulnerable to cardiovascular events and progressive kidney failure, Dr. Chertow and colleagues wrote.

The DAPA-CKD trial randomized 4,304 patients with CKD 1:1 to dapagliflozin 10 mg/day or placebo, including 624 patients (14%) who had eGFR < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and albuminuria at baseline.

Patients in the subgroup with advanced CKD had a mean age of 62 years, and 37% were female. About two-thirds had type 2 diabetes and about one-third had cardiovascular disease.

A total of 293 patients received dapagliflozin and 331 patients received placebo.

During a median follow-up of 2.4 years, patients who received dapagliflozin as opposed to placebo had a lower risk of the primary efficacy outcome – a composite of a 50% or greater sustained decline in eGFR, end-stage kidney disease, or death from cardiovascular or renal causes (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-1.02).

In secondary efficacy outcomes, patients who received dapagliflozin as opposed to placebo also had a lower risk of the following:

- A renal composite outcome – a ≥ 50% sustained decline in eGFR, end-stage kidney disease, or death from renal causes (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.49-1.02).

- A cardiovascular composite outcome comprising cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.45-1.53).

- All-cause mortality (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.39 to 1.21).

The eGFR slope declined by 2.15 mL/min per 1.73 m2 per year and by 3.38 mL/min per 1.73 m2 per year in the dapagliflozin and placebo groups, respectively (P = .005).

“The trial was not powered to detect a statistically significant difference in the primary and key secondary endpoints in modest-sized subgroups,” the researchers noted.

The researchers limited their safety analysis to serious adverse events or symptoms of volume depletion, kidney-related events, major hypoglycemia, bone fractures, amputations, and potential diabetic ketoacidosis.

There was no evidence of increased risk of these adverse events in patients who received dapagliflozin.

The subanalysis of the DAPA-CKD trial was published July 16 in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Chertow has received fees from AstraZeneca for the DAPA-CKD trial steering committee. The disclosures of the other authors are listed in the article. Dr. Mathieu has served on the advisory panel/speakers bureau for AstraZeneca. Dr. Chertow and Dr. Mathieu also have financial relationships with many other pharmaceutical companies.

Patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (CKD) who were in the DAPA-CKD trial had cardiorenal benefits from dapagliflozin that were similar to those of patients in the overall trial, with no added safety signal.

DAPA-CKD (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease) was a landmark study of more than 4,000 patients with CKD, with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 25-75 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and albuminuria with/without type 2 diabetes.

The primary results showed that patients who received the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin for a median of 2.4 years were significantly less likely to have worsening kidney disease or die from all causes than were patients who received placebo.

“This prespecified subanalysis of people with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 [stage 4 CKD] in the DAPA-CKD study shows first, that in this very vulnerable population, use of the SGLT2 inhibitor is safe,” said Chantal Mathieu, MD, PhD.

Furthermore, there was no signal whatsoever of more adverse events and even a trend to fewer events, she said in an email to this news organization.

The analysis also showed that “although now in small numbers (around 300 each in the treated group vs. placebo group), there is no suggestion that the protective effect of dapagliflozin on the renal and cardiovascular front would not happen in this group” with advanced CKD. The efficacy findings just missed statistical significance, noted Dr. Mathieu, of Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium, who was not involved in the study.

Although dapagliflozin is now approved for treating patients with CKD who are at risk of kidney disease progression (on the basis of the DAPA-CKD results), guidelines have not yet been updated to reflect this, lead investigator Glenn M. Chertow, MD, MPH, of Stanford (Calif.) University, told this news organization in an email.

“For clinicians,” Dr. Mathieu said, “this is now the absolute reassurance that we do not have to stop an SGLT2 inhibitor in people with eGFR < 30 mL/min for safety reasons and that we should maintain them at these values for renal and cardiovascular protection!

“I absolutely hope labels will change soon to reflect these observations (and indeed movement on that front is happening),” she continued.

“The American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes consensus on glucose-lowering therapies in type 2 diabetes already advocated keeping these agents until eGFR 30 mL/min (on the basis of evidence in 2019),” Dr. Mathieu added, “but this study will probably push the statements even further.”

“Of note,” she pointed out, “at these low eGFRs, the glucose-lowering potential of the SGLT2 inhibitor is negligible.”

Dapagliflozin risks and benefits in advanced CKD

Based on the DAPA-CKD study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine Oct. 8, 2020, the Food and Drug Administration expanded the indication for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in April of 2021.

However, relatively little is known about the safety and efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with advanced CKD, who are particularly vulnerable to cardiovascular events and progressive kidney failure, Dr. Chertow and colleagues wrote.

The DAPA-CKD trial randomized 4,304 patients with CKD 1:1 to dapagliflozin 10 mg/day or placebo, including 624 patients (14%) who had eGFR < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and albuminuria at baseline.

Patients in the subgroup with advanced CKD had a mean age of 62 years, and 37% were female. About two-thirds had type 2 diabetes and about one-third had cardiovascular disease.

A total of 293 patients received dapagliflozin and 331 patients received placebo.

During a median follow-up of 2.4 years, patients who received dapagliflozin as opposed to placebo had a lower risk of the primary efficacy outcome – a composite of a 50% or greater sustained decline in eGFR, end-stage kidney disease, or death from cardiovascular or renal causes (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-1.02).

In secondary efficacy outcomes, patients who received dapagliflozin as opposed to placebo also had a lower risk of the following:

- A renal composite outcome – a ≥ 50% sustained decline in eGFR, end-stage kidney disease, or death from renal causes (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.49-1.02).

- A cardiovascular composite outcome comprising cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.45-1.53).

- All-cause mortality (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.39 to 1.21).

The eGFR slope declined by 2.15 mL/min per 1.73 m2 per year and by 3.38 mL/min per 1.73 m2 per year in the dapagliflozin and placebo groups, respectively (P = .005).

“The trial was not powered to detect a statistically significant difference in the primary and key secondary endpoints in modest-sized subgroups,” the researchers noted.

The researchers limited their safety analysis to serious adverse events or symptoms of volume depletion, kidney-related events, major hypoglycemia, bone fractures, amputations, and potential diabetic ketoacidosis.

There was no evidence of increased risk of these adverse events in patients who received dapagliflozin.

The subanalysis of the DAPA-CKD trial was published July 16 in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Chertow has received fees from AstraZeneca for the DAPA-CKD trial steering committee. The disclosures of the other authors are listed in the article. Dr. Mathieu has served on the advisory panel/speakers bureau for AstraZeneca. Dr. Chertow and Dr. Mathieu also have financial relationships with many other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF NEPHROLOGY

‘Wild West’ and weak evidence for weight-loss supplements

“Purported” weight-loss products –12 dietary supplements and 2 alternative therapies – lack high-quality evidence to back up claims of efficacy, a systematic review by the Obesity Society reports.

Most of the more than 300 published randomized controlled trials in the review were small and short, and only 0.5% found a statistically significant weight loss of up to 5 kg, John A. Batsis, MD, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and colleagues reported in the journal Obesity.

“Despite the poor quality of these studies with high degrees of bias, most still failed to show efficacy of the product they were testing,” Srividya Kidambi, MD, from the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and colleagues from the Obesity Society’s Clinical Committee pointed out in an accompanying commentary.

“Yet these are the studies that are often used to support manufacturers’ claims of ‘clinically proven’ in their marketing,” they noted.

Most consumers, they continued, are unaware that these nondrug weight-loss products are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, but rather, if their ingredients are “generally regarded as safe,” they are treated as dietary supplements and require little or no testing to show either efficacy or safety.

“Our patients need to become aware that dietary supplements for weight loss are nothing more than a pipe dream, and as clinicians we would do well to talk with our patients and help steer them toward science-based treatments rather than the ‘Wild West’ of dietary supplements that are marketed for weight loss,” Scott Kahan, MD, MPH, coauthor of the review and commentary, told this news organization.

The dietary supplement industry has a strong lobby against legislation for more rigorous requirements for claims, noted Dr. Kahan, of the National Center for Weight and Wellness as well as George Washington University, Washington.

However, “there has to be some level of protection for consumers” who are faced with ads by “healthy skinny people saying this [product] can change your life.”

Clinical providers need to guide patients to “evidence-based interventions to support weight loss such as behavioral weight-loss interventions, [FDA-approved] medications, or bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Batsis, who also coauthored the commentary.

There is a “critical need” for more rigorous trials, and a partnership between researchers, funders, and industry, he added.

According to Dr. Kidambi and colleagues, “the use of these products will continue as long as they are allowed to be marketed with the aforementioned limited federal oversight and there is a lack of access to evidence-based obesity treatments.”

The commentary authors “call on regulatory authorities to critically examine the dietary supplement industry, including their role in promoting misleading claims and marketing products that have the potential to harm patients.”

They also urged public and private health insurance plans to “provide adequate resources for obesity management.”

And clinicians should “consider the lack of evidence for non–FDA-approved dietary supplements and therapies and guide their patients toward tested weight-management approaches.”

Subpar evidence, booming industry

“Annual sales of dietary supplements for weight loss are booming with an industry valued at $30 billion worldwide, despite subpar evidence” of efficacy, the commentary authors wrote by way of background.

After the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Dietary Supplements was established “to strengthen the knowledge and understanding of dietary supplements by evaluating scientific information, stimulating and supporting research, and educating the public,” they explained.

However, dietary supplements and alternative therapies are endorsed by influencers and celebrities and marketed as a panacea for obesity and weight gain.

Literature review finds scant evidence