User login

M. Alexander Otto began his reporting career early in 1999 covering the pharmaceutical industry for a national pharmacists' magazine and freelancing for the Washington Post and other newspapers. He then joined BNA, now part of Bloomberg News, covering health law and the protection of people and animals in medical research. Alex next worked for the McClatchy Company. Based on his work, Alex won a year-long Knight Science Journalism Fellowship to MIT in 2008-2009. He joined the company shortly thereafter. Alex has a newspaper journalism degree from Syracuse (N.Y.) University and a master's degree in medical science -- a physician assistant degree -- from George Washington University. Alex is based in Seattle.

N.Y. hospitals report near-universal CMV screening when newborns fail hearing tests

BALTIMORE – Over the past 2 years, Northwell Health, a large medical system in the metropolitan New York area, increased cytomegalovirus screening for infants who fail hearing tests from 6.6% to 95% at five of its birth hospitals, according to a presentation at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

Three cases of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) have been picked up so far. The plan is to roll the program out to all 10 of the system’s birth hospitals, where over 40,000 children are born each year.

“We feel very satisfied and proud” of the progress that’s been made at Northwell in such a short time, said Alia Chauhan, MD, a Northwell pediatrician who presented the findings.

Northwell launched its “Hearing Plus” program in 2017 to catch the infection before infants leave the hospital. Several other health systems around the country have launched similar programs, and a handful of states – including New York – now require CMV screening for infants who fail mandated hearing tests.

The issue is gaining traction because hearing loss is often the only sign of congenital CMV, so it’s a bellwether for infection. Screening children with hearing loss is an easy way to pick it up early, so steps can be taken to prevent problems down the road. As it is, congenital CMV is the leading nongenetic cause of hearing loss in infants, accounting for at least 10% of cases.

The Northwell program kicked off with an education campaign to build consensus among pediatricians, hospitalists, and nurses. A flyer was made about CMV screening for moms whose infants fail hearing tests, printed in both English and Spanish.

Initially, the program used urine PCR [polymerase chain reaction] to screen for CMV, but waiting for infants to produce a sample often delayed discharge, so a switch was soon made to saliva swab PCRs, which take seconds, with urine PCR held in reserve to confirm positive swabs.

To streamline the process, a standing order was added to the electronic records system so nurses could order saliva PCRs without having to get physician approval. “I think [that] was one of the biggest things that’s helped us,” Dr. Chauhan said.

Children who test positive must have urine confirmation within 21 days of birth; most are long gone from the hospital by then and have to be called back in. “We haven’t lost anyone to follow-up, but it can be stressful trying to get someone to come back,” she said.

Six of 449 infants have screened positive on saliva – three were false positives with negative urine screens. Of the three confirmed cases, two infants later turned out to have normal hearing on repeat testing and were otherwise asymptomatic.

These days, Dr. Chauhan said, if children have a positive saliva PCR but later turn out to have normal hearing, and are otherwise free of symptoms with no CMV risk factors, “we are not confirming with urine.”

Dr. Chauhan did not have any disclosures. No funding source was mentioned.

SOURCE: Chauhan A et al. PAS 2019. Abstract 306

BALTIMORE – Over the past 2 years, Northwell Health, a large medical system in the metropolitan New York area, increased cytomegalovirus screening for infants who fail hearing tests from 6.6% to 95% at five of its birth hospitals, according to a presentation at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

Three cases of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) have been picked up so far. The plan is to roll the program out to all 10 of the system’s birth hospitals, where over 40,000 children are born each year.

“We feel very satisfied and proud” of the progress that’s been made at Northwell in such a short time, said Alia Chauhan, MD, a Northwell pediatrician who presented the findings.

Northwell launched its “Hearing Plus” program in 2017 to catch the infection before infants leave the hospital. Several other health systems around the country have launched similar programs, and a handful of states – including New York – now require CMV screening for infants who fail mandated hearing tests.

The issue is gaining traction because hearing loss is often the only sign of congenital CMV, so it’s a bellwether for infection. Screening children with hearing loss is an easy way to pick it up early, so steps can be taken to prevent problems down the road. As it is, congenital CMV is the leading nongenetic cause of hearing loss in infants, accounting for at least 10% of cases.

The Northwell program kicked off with an education campaign to build consensus among pediatricians, hospitalists, and nurses. A flyer was made about CMV screening for moms whose infants fail hearing tests, printed in both English and Spanish.

Initially, the program used urine PCR [polymerase chain reaction] to screen for CMV, but waiting for infants to produce a sample often delayed discharge, so a switch was soon made to saliva swab PCRs, which take seconds, with urine PCR held in reserve to confirm positive swabs.

To streamline the process, a standing order was added to the electronic records system so nurses could order saliva PCRs without having to get physician approval. “I think [that] was one of the biggest things that’s helped us,” Dr. Chauhan said.

Children who test positive must have urine confirmation within 21 days of birth; most are long gone from the hospital by then and have to be called back in. “We haven’t lost anyone to follow-up, but it can be stressful trying to get someone to come back,” she said.

Six of 449 infants have screened positive on saliva – three were false positives with negative urine screens. Of the three confirmed cases, two infants later turned out to have normal hearing on repeat testing and were otherwise asymptomatic.

These days, Dr. Chauhan said, if children have a positive saliva PCR but later turn out to have normal hearing, and are otherwise free of symptoms with no CMV risk factors, “we are not confirming with urine.”

Dr. Chauhan did not have any disclosures. No funding source was mentioned.

SOURCE: Chauhan A et al. PAS 2019. Abstract 306

BALTIMORE – Over the past 2 years, Northwell Health, a large medical system in the metropolitan New York area, increased cytomegalovirus screening for infants who fail hearing tests from 6.6% to 95% at five of its birth hospitals, according to a presentation at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

Three cases of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) have been picked up so far. The plan is to roll the program out to all 10 of the system’s birth hospitals, where over 40,000 children are born each year.

“We feel very satisfied and proud” of the progress that’s been made at Northwell in such a short time, said Alia Chauhan, MD, a Northwell pediatrician who presented the findings.

Northwell launched its “Hearing Plus” program in 2017 to catch the infection before infants leave the hospital. Several other health systems around the country have launched similar programs, and a handful of states – including New York – now require CMV screening for infants who fail mandated hearing tests.

The issue is gaining traction because hearing loss is often the only sign of congenital CMV, so it’s a bellwether for infection. Screening children with hearing loss is an easy way to pick it up early, so steps can be taken to prevent problems down the road. As it is, congenital CMV is the leading nongenetic cause of hearing loss in infants, accounting for at least 10% of cases.

The Northwell program kicked off with an education campaign to build consensus among pediatricians, hospitalists, and nurses. A flyer was made about CMV screening for moms whose infants fail hearing tests, printed in both English and Spanish.

Initially, the program used urine PCR [polymerase chain reaction] to screen for CMV, but waiting for infants to produce a sample often delayed discharge, so a switch was soon made to saliva swab PCRs, which take seconds, with urine PCR held in reserve to confirm positive swabs.

To streamline the process, a standing order was added to the electronic records system so nurses could order saliva PCRs without having to get physician approval. “I think [that] was one of the biggest things that’s helped us,” Dr. Chauhan said.

Children who test positive must have urine confirmation within 21 days of birth; most are long gone from the hospital by then and have to be called back in. “We haven’t lost anyone to follow-up, but it can be stressful trying to get someone to come back,” she said.

Six of 449 infants have screened positive on saliva – three were false positives with negative urine screens. Of the three confirmed cases, two infants later turned out to have normal hearing on repeat testing and were otherwise asymptomatic.

These days, Dr. Chauhan said, if children have a positive saliva PCR but later turn out to have normal hearing, and are otherwise free of symptoms with no CMV risk factors, “we are not confirming with urine.”

Dr. Chauhan did not have any disclosures. No funding source was mentioned.

SOURCE: Chauhan A et al. PAS 2019. Abstract 306

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Key clinical point: A metropolitan N.Y. health system provides a model for how to implement cytomegalovirus screening for infants who fail hearing tests.

Major finding: .

Study details: Pre-post quality improvement project.

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no disclosures. No funding source was mentioned.

Source: Chauhan A et al. PAS 2019. Abstract 306.

No exudates or fever? Age over 11? Skip strep test

BALTIMORE – In children with pharyngitis, it’s safe to skip group A Streptococcus testing if there are no exudates, children are 11 years or older, and there is either no cervical adenopathy or adenopathy without fever, according to a Boston Children’s Hospital investigation.

The prevalence of group A Streptococcus among children who meet those criteria is 13%, less than the estimated asymptomatic carriage rate of about 15%. Among 67,127 children tested for strep and treated for sore throats in a network of retail health clinics across the United States, 35% fit the profile.

Investigators led by Daniel Shapiro, MD, a pediatrics fellow at Boston Children’s, concluded that “laboratory testing for GAS [group A Streptococcus] might be safely avoided in a large proportion of patients with sore throats. In doing so, we may avoid some of the downstream effects of unnecessary antibiotic use.” Incorporating the rules into EHRs “might help physicians identify patients who are at low risk of GAS pharyngitis.”

The study team tackled a long-standing and vexing problem in general pediatrics: how to distinguish viral from GAS pharyngitis. They often present the same way, so it’s difficult to tell them apart, but important to do so to prevent misuse of antibiotics. Health care providers generally rely on rapid strep tests and other assays to make the call, but they have to be used cautiously, because asymptomatic carriers also will test positive and be at risk for unnecessary treatment, Dr. Shapiro said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

To try to prevent that, the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) recommends against strep testing in children who present with overt viral signs, including cough, rhinorrhea, oral ulcers, and hoarseness (Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55[10]:1279-82).

In a previous study at Boston Children’s ED, however, Dr. Shapiro and his colleagues found that 29% of children with overt viral features were positive for GAS, suggesting that the IDSA guidelines probably go too far (Pediatrics. 2017 May;139[5]. pii: e20163403).

“One might conclude that while it’s a good rule of thumb to avoid testing patients with viral features, some of the patients with viral features really do have GAS pharyngitis, so the recommendation to forgo testing in all these kids needs a little bit of refinement,” he said.

That was the goal of the new study; the team sought to identify viral features that signaled a low risk of GAS pharyngitis and, therefore, no need for testing. Low risk was defined as less than 15%, in keeping with the asymptomatic carriage rate.

The 67,127 patients were aged 3-21 years. Their signs and symptoms were collected at the retail clinics in a standardized form. The subjects had rapid strep tests, with negative results confirmed by DNA probe or culture.

Fifty-four percent had viral features, defined in the study as cough, runny nose, or hoarseness (oral ulcers weren’t collected on the form). The overall prevalence of GAS was 35%, similar to previous studies; 39% of children with no viral features tested positive for GAS versus 26% of children with all three. Exudates and age below 11 years were strongly associated with GAS among patients with viral features.

It turned out that just 23% of children without exudates were GAS positive; the number fell to 15% when limited to children 11 years or older, and to 13% when either no cervical adenopathy or adenopathy without fever were added to the mix.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Shapiro didn’t have any disclosures.

BALTIMORE – In children with pharyngitis, it’s safe to skip group A Streptococcus testing if there are no exudates, children are 11 years or older, and there is either no cervical adenopathy or adenopathy without fever, according to a Boston Children’s Hospital investigation.

The prevalence of group A Streptococcus among children who meet those criteria is 13%, less than the estimated asymptomatic carriage rate of about 15%. Among 67,127 children tested for strep and treated for sore throats in a network of retail health clinics across the United States, 35% fit the profile.

Investigators led by Daniel Shapiro, MD, a pediatrics fellow at Boston Children’s, concluded that “laboratory testing for GAS [group A Streptococcus] might be safely avoided in a large proportion of patients with sore throats. In doing so, we may avoid some of the downstream effects of unnecessary antibiotic use.” Incorporating the rules into EHRs “might help physicians identify patients who are at low risk of GAS pharyngitis.”

The study team tackled a long-standing and vexing problem in general pediatrics: how to distinguish viral from GAS pharyngitis. They often present the same way, so it’s difficult to tell them apart, but important to do so to prevent misuse of antibiotics. Health care providers generally rely on rapid strep tests and other assays to make the call, but they have to be used cautiously, because asymptomatic carriers also will test positive and be at risk for unnecessary treatment, Dr. Shapiro said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

To try to prevent that, the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) recommends against strep testing in children who present with overt viral signs, including cough, rhinorrhea, oral ulcers, and hoarseness (Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55[10]:1279-82).

In a previous study at Boston Children’s ED, however, Dr. Shapiro and his colleagues found that 29% of children with overt viral features were positive for GAS, suggesting that the IDSA guidelines probably go too far (Pediatrics. 2017 May;139[5]. pii: e20163403).

“One might conclude that while it’s a good rule of thumb to avoid testing patients with viral features, some of the patients with viral features really do have GAS pharyngitis, so the recommendation to forgo testing in all these kids needs a little bit of refinement,” he said.

That was the goal of the new study; the team sought to identify viral features that signaled a low risk of GAS pharyngitis and, therefore, no need for testing. Low risk was defined as less than 15%, in keeping with the asymptomatic carriage rate.

The 67,127 patients were aged 3-21 years. Their signs and symptoms were collected at the retail clinics in a standardized form. The subjects had rapid strep tests, with negative results confirmed by DNA probe or culture.

Fifty-four percent had viral features, defined in the study as cough, runny nose, or hoarseness (oral ulcers weren’t collected on the form). The overall prevalence of GAS was 35%, similar to previous studies; 39% of children with no viral features tested positive for GAS versus 26% of children with all three. Exudates and age below 11 years were strongly associated with GAS among patients with viral features.

It turned out that just 23% of children without exudates were GAS positive; the number fell to 15% when limited to children 11 years or older, and to 13% when either no cervical adenopathy or adenopathy without fever were added to the mix.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Shapiro didn’t have any disclosures.

BALTIMORE – In children with pharyngitis, it’s safe to skip group A Streptococcus testing if there are no exudates, children are 11 years or older, and there is either no cervical adenopathy or adenopathy without fever, according to a Boston Children’s Hospital investigation.

The prevalence of group A Streptococcus among children who meet those criteria is 13%, less than the estimated asymptomatic carriage rate of about 15%. Among 67,127 children tested for strep and treated for sore throats in a network of retail health clinics across the United States, 35% fit the profile.

Investigators led by Daniel Shapiro, MD, a pediatrics fellow at Boston Children’s, concluded that “laboratory testing for GAS [group A Streptococcus] might be safely avoided in a large proportion of patients with sore throats. In doing so, we may avoid some of the downstream effects of unnecessary antibiotic use.” Incorporating the rules into EHRs “might help physicians identify patients who are at low risk of GAS pharyngitis.”

The study team tackled a long-standing and vexing problem in general pediatrics: how to distinguish viral from GAS pharyngitis. They often present the same way, so it’s difficult to tell them apart, but important to do so to prevent misuse of antibiotics. Health care providers generally rely on rapid strep tests and other assays to make the call, but they have to be used cautiously, because asymptomatic carriers also will test positive and be at risk for unnecessary treatment, Dr. Shapiro said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

To try to prevent that, the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) recommends against strep testing in children who present with overt viral signs, including cough, rhinorrhea, oral ulcers, and hoarseness (Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55[10]:1279-82).

In a previous study at Boston Children’s ED, however, Dr. Shapiro and his colleagues found that 29% of children with overt viral features were positive for GAS, suggesting that the IDSA guidelines probably go too far (Pediatrics. 2017 May;139[5]. pii: e20163403).

“One might conclude that while it’s a good rule of thumb to avoid testing patients with viral features, some of the patients with viral features really do have GAS pharyngitis, so the recommendation to forgo testing in all these kids needs a little bit of refinement,” he said.

That was the goal of the new study; the team sought to identify viral features that signaled a low risk of GAS pharyngitis and, therefore, no need for testing. Low risk was defined as less than 15%, in keeping with the asymptomatic carriage rate.

The 67,127 patients were aged 3-21 years. Their signs and symptoms were collected at the retail clinics in a standardized form. The subjects had rapid strep tests, with negative results confirmed by DNA probe or culture.

Fifty-four percent had viral features, defined in the study as cough, runny nose, or hoarseness (oral ulcers weren’t collected on the form). The overall prevalence of GAS was 35%, similar to previous studies; 39% of children with no viral features tested positive for GAS versus 26% of children with all three. Exudates and age below 11 years were strongly associated with GAS among patients with viral features.

It turned out that just 23% of children without exudates were GAS positive; the number fell to 15% when limited to children 11 years or older, and to 13% when either no cervical adenopathy or adenopathy without fever were added to the mix.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Shapiro didn’t have any disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

A gentler approach to gastroschisis improves outcomes

BALTIMORE – a condition in which infants are born with their intestines and sometimes other organs protruding through a hole beside the umbilicus.

Neonatologists, maternal-fetal health experts, and pediatric surgeons standardized a literature-based approach that was gentler and less invasive than usual management, emphasizing sutureless closure, sometimes at bedside on the first day of life, and early feeding. Often, it turned out, that’s all that children require.

It’s made a big difference. “We reduced the number of trips to the operating room and exposure to general anesthesia. We reduced the number of babies intubated and days on the ventilator. We reduced opioid days and antibiotic days” without increasing bacteremia, and “there are probably long-term benefits beyond the NICU,” said Kara Calkins, MD, at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

I think this is definitely ahead of the curve for NICUs. My hope is that the vast majority of universities adopt a similar approach,” said Dr. Calkins, who is an assistant professor of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“When I was a fellow,” she explained, “we took all of these babies and intubated them right away and put them on a drip to paralyze and sedate them. We put their bowels into a silo,” essentially a plastic bag suspended by a string, in the hopes that gravity would pull the bowels back into the abdomen. More often than not, however, “the surgeon would come by every day and slowly push them” back in over a week or so. “The fear was if you did it too quickly, you’d invoke an abdominal compartment syndrome, or respiratory decompensation. You had a baby intubated for a week, sedated and paralyzed.”

Infants were kept on total parenteral nutrition for weeks, sometimes through a Broviac central catheter.

It was overkill, Dr. Calkins said, when only the intestines are out and the abdominal wall defect isn’t too large or too small, which is the case for many infants.

For those children, sutureless closure over 1-3 days is the new goal. The bowel is worked back into the abdomen and the umbilical cord is pulled to the side to approximate the edges of the wound, and tacked down; the defect then heals itself. Antibiotics are discontinued 48 hours after closure. Gastric and rectal decompression helps with reduction.

Also, “we give drops of breast milk in their cheek right away, every couple of hours starting on the first day of life. Once the output from the gastric tube is clear, we start feeds. We still give total parenteral nutrition, but through a [peripherally inserted central catheter] in the arm,” Dr. Calkins said. “Use of breast milk for this population is important” to help establish a healthy microbiome, among other reasons.

Another improvement that had been made, according to Dr. Calkins, is that if only the intestines are out, women carry their baby to term and deliver vaginally. The old practice was to deliver babies preterm by Cesarean section, she explained.

To see how it’s worked out, Dr. Calkins and her colleagues reviewed 70 gastroschisis cases managed under the new guidelines. They were uncomplicated cases, with no intestinal atresia, stricture, or ischemia.

Paralysis was avoided for silo placement in 53 infants (76%) and 32 (46%) avoided intubation. Antibiotics were discontinued in 56 (80%) within 48 hours of abdominal wall closure, and routine narcotics were discontinued in 53 infants (76%). Feeds were initiated in almost all children within 48 hours of non-bilious gastric tube output.

Compared with 168 infants treated before the changes were made, silo placement dropped from 71% to 58% of infants, and total ventilator days from a median of 5 to 2.

There was no difference in length of stay, perhaps because the “intestinal dysmotility intrinsic to gastroschisis remains a rate limiting factor for discharge,” the team concluded.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Calkins didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottkamp CA et al., PAS 2019. Abstract 51.

BALTIMORE – a condition in which infants are born with their intestines and sometimes other organs protruding through a hole beside the umbilicus.

Neonatologists, maternal-fetal health experts, and pediatric surgeons standardized a literature-based approach that was gentler and less invasive than usual management, emphasizing sutureless closure, sometimes at bedside on the first day of life, and early feeding. Often, it turned out, that’s all that children require.

It’s made a big difference. “We reduced the number of trips to the operating room and exposure to general anesthesia. We reduced the number of babies intubated and days on the ventilator. We reduced opioid days and antibiotic days” without increasing bacteremia, and “there are probably long-term benefits beyond the NICU,” said Kara Calkins, MD, at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

I think this is definitely ahead of the curve for NICUs. My hope is that the vast majority of universities adopt a similar approach,” said Dr. Calkins, who is an assistant professor of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“When I was a fellow,” she explained, “we took all of these babies and intubated them right away and put them on a drip to paralyze and sedate them. We put their bowels into a silo,” essentially a plastic bag suspended by a string, in the hopes that gravity would pull the bowels back into the abdomen. More often than not, however, “the surgeon would come by every day and slowly push them” back in over a week or so. “The fear was if you did it too quickly, you’d invoke an abdominal compartment syndrome, or respiratory decompensation. You had a baby intubated for a week, sedated and paralyzed.”

Infants were kept on total parenteral nutrition for weeks, sometimes through a Broviac central catheter.

It was overkill, Dr. Calkins said, when only the intestines are out and the abdominal wall defect isn’t too large or too small, which is the case for many infants.

For those children, sutureless closure over 1-3 days is the new goal. The bowel is worked back into the abdomen and the umbilical cord is pulled to the side to approximate the edges of the wound, and tacked down; the defect then heals itself. Antibiotics are discontinued 48 hours after closure. Gastric and rectal decompression helps with reduction.

Also, “we give drops of breast milk in their cheek right away, every couple of hours starting on the first day of life. Once the output from the gastric tube is clear, we start feeds. We still give total parenteral nutrition, but through a [peripherally inserted central catheter] in the arm,” Dr. Calkins said. “Use of breast milk for this population is important” to help establish a healthy microbiome, among other reasons.

Another improvement that had been made, according to Dr. Calkins, is that if only the intestines are out, women carry their baby to term and deliver vaginally. The old practice was to deliver babies preterm by Cesarean section, she explained.

To see how it’s worked out, Dr. Calkins and her colleagues reviewed 70 gastroschisis cases managed under the new guidelines. They were uncomplicated cases, with no intestinal atresia, stricture, or ischemia.

Paralysis was avoided for silo placement in 53 infants (76%) and 32 (46%) avoided intubation. Antibiotics were discontinued in 56 (80%) within 48 hours of abdominal wall closure, and routine narcotics were discontinued in 53 infants (76%). Feeds were initiated in almost all children within 48 hours of non-bilious gastric tube output.

Compared with 168 infants treated before the changes were made, silo placement dropped from 71% to 58% of infants, and total ventilator days from a median of 5 to 2.

There was no difference in length of stay, perhaps because the “intestinal dysmotility intrinsic to gastroschisis remains a rate limiting factor for discharge,” the team concluded.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Calkins didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottkamp CA et al., PAS 2019. Abstract 51.

BALTIMORE – a condition in which infants are born with their intestines and sometimes other organs protruding through a hole beside the umbilicus.

Neonatologists, maternal-fetal health experts, and pediatric surgeons standardized a literature-based approach that was gentler and less invasive than usual management, emphasizing sutureless closure, sometimes at bedside on the first day of life, and early feeding. Often, it turned out, that’s all that children require.

It’s made a big difference. “We reduced the number of trips to the operating room and exposure to general anesthesia. We reduced the number of babies intubated and days on the ventilator. We reduced opioid days and antibiotic days” without increasing bacteremia, and “there are probably long-term benefits beyond the NICU,” said Kara Calkins, MD, at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

I think this is definitely ahead of the curve for NICUs. My hope is that the vast majority of universities adopt a similar approach,” said Dr. Calkins, who is an assistant professor of neonatology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“When I was a fellow,” she explained, “we took all of these babies and intubated them right away and put them on a drip to paralyze and sedate them. We put their bowels into a silo,” essentially a plastic bag suspended by a string, in the hopes that gravity would pull the bowels back into the abdomen. More often than not, however, “the surgeon would come by every day and slowly push them” back in over a week or so. “The fear was if you did it too quickly, you’d invoke an abdominal compartment syndrome, or respiratory decompensation. You had a baby intubated for a week, sedated and paralyzed.”

Infants were kept on total parenteral nutrition for weeks, sometimes through a Broviac central catheter.

It was overkill, Dr. Calkins said, when only the intestines are out and the abdominal wall defect isn’t too large or too small, which is the case for many infants.

For those children, sutureless closure over 1-3 days is the new goal. The bowel is worked back into the abdomen and the umbilical cord is pulled to the side to approximate the edges of the wound, and tacked down; the defect then heals itself. Antibiotics are discontinued 48 hours after closure. Gastric and rectal decompression helps with reduction.

Also, “we give drops of breast milk in their cheek right away, every couple of hours starting on the first day of life. Once the output from the gastric tube is clear, we start feeds. We still give total parenteral nutrition, but through a [peripherally inserted central catheter] in the arm,” Dr. Calkins said. “Use of breast milk for this population is important” to help establish a healthy microbiome, among other reasons.

Another improvement that had been made, according to Dr. Calkins, is that if only the intestines are out, women carry their baby to term and deliver vaginally. The old practice was to deliver babies preterm by Cesarean section, she explained.

To see how it’s worked out, Dr. Calkins and her colleagues reviewed 70 gastroschisis cases managed under the new guidelines. They were uncomplicated cases, with no intestinal atresia, stricture, or ischemia.

Paralysis was avoided for silo placement in 53 infants (76%) and 32 (46%) avoided intubation. Antibiotics were discontinued in 56 (80%) within 48 hours of abdominal wall closure, and routine narcotics were discontinued in 53 infants (76%). Feeds were initiated in almost all children within 48 hours of non-bilious gastric tube output.

Compared with 168 infants treated before the changes were made, silo placement dropped from 71% to 58% of infants, and total ventilator days from a median of 5 to 2.

There was no difference in length of stay, perhaps because the “intestinal dysmotility intrinsic to gastroschisis remains a rate limiting factor for discharge,” the team concluded.

There was no industry funding, and Dr. Calkins didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottkamp CA et al., PAS 2019. Abstract 51.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Combo respiratory pathogen tests miss pertussis

BALTIMORE – Ann Arbor.

Respiratory pathogen panels are popular because they test for many things at once, but providers have to know their limits, said lead investigator Colleen Mayhew, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at the University of Michigan.

“Should RPAN be used to diagnosis pertussis? No,” she said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. RPAN was negative for confirmed pertussis 44% of the time in the study.

“In our cohort, [it] was no better than a coin flip for detecting pertussis,” she said. Also, even when it missed pertussis, it still detected other pathogens, which raises the risk that symptoms might be attributed to a different infection. “This has serious public health implications.”

“The bottom line is, if you are concerned about pertussis, it’s important to use a dedicated pertussis PCR [polymerase chain reaction] assay, and to use comprehensive respiratory pathogen testing only if there are other, specific targets that will change your clinical management,” such as mycoplasma or the flu, Dr. Mayhew said.

In the study, 102 nasopharyngeal swabs positive for pertussis on standalone PCR testing – the university uses an assay from Focus Diagnostics – were thawed and tested with RPAN.

RPAN was negative for pertussis on 45 swabs (44%). “These are the potential missed pertussis cases if RPAN is used alone,” Dr. Mayhew said. RPAN detected other pathogens, such as coronavirus, about half the time, whether or not it tested positive for pertussis. “Those additional pathogens might represent coinfection, but might also represent asymptomatic carriage.” It’s impossible to differentiate between the two, she noted.

In short, “neither positive testing for other respiratory pathogens, nor negative testing for pertussis by RPAN, is reliable for excluding the diagnosis of pertussis. Dedicated pertussis PCR testing should be used for diagnosis,” she and her team concluded.

RPAN also is a PCR test, but with a different, perhaps less robust, genetic target.

The 102 positive swabs were from patients aged 1 month to 73 years, so “it’s important for all of us to keep pertussis on our differential diagnose” no matter how old patients are, Dr. Mayhew said.

Freezing and thawing the swabs shouldn’t have degraded the genetic material, but it might have; that was one of the limits of the study.

The team hopes to run a quality improvement project to encourage the use of standalone pertussis PCR in Ann Arbor.

There was no industry funding. Dr. Mayhew didn’t report any disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Ann Arbor.

Respiratory pathogen panels are popular because they test for many things at once, but providers have to know their limits, said lead investigator Colleen Mayhew, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at the University of Michigan.

“Should RPAN be used to diagnosis pertussis? No,” she said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. RPAN was negative for confirmed pertussis 44% of the time in the study.

“In our cohort, [it] was no better than a coin flip for detecting pertussis,” she said. Also, even when it missed pertussis, it still detected other pathogens, which raises the risk that symptoms might be attributed to a different infection. “This has serious public health implications.”

“The bottom line is, if you are concerned about pertussis, it’s important to use a dedicated pertussis PCR [polymerase chain reaction] assay, and to use comprehensive respiratory pathogen testing only if there are other, specific targets that will change your clinical management,” such as mycoplasma or the flu, Dr. Mayhew said.

In the study, 102 nasopharyngeal swabs positive for pertussis on standalone PCR testing – the university uses an assay from Focus Diagnostics – were thawed and tested with RPAN.

RPAN was negative for pertussis on 45 swabs (44%). “These are the potential missed pertussis cases if RPAN is used alone,” Dr. Mayhew said. RPAN detected other pathogens, such as coronavirus, about half the time, whether or not it tested positive for pertussis. “Those additional pathogens might represent coinfection, but might also represent asymptomatic carriage.” It’s impossible to differentiate between the two, she noted.

In short, “neither positive testing for other respiratory pathogens, nor negative testing for pertussis by RPAN, is reliable for excluding the diagnosis of pertussis. Dedicated pertussis PCR testing should be used for diagnosis,” she and her team concluded.

RPAN also is a PCR test, but with a different, perhaps less robust, genetic target.

The 102 positive swabs were from patients aged 1 month to 73 years, so “it’s important for all of us to keep pertussis on our differential diagnose” no matter how old patients are, Dr. Mayhew said.

Freezing and thawing the swabs shouldn’t have degraded the genetic material, but it might have; that was one of the limits of the study.

The team hopes to run a quality improvement project to encourage the use of standalone pertussis PCR in Ann Arbor.

There was no industry funding. Dr. Mayhew didn’t report any disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Ann Arbor.

Respiratory pathogen panels are popular because they test for many things at once, but providers have to know their limits, said lead investigator Colleen Mayhew, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at the University of Michigan.

“Should RPAN be used to diagnosis pertussis? No,” she said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. RPAN was negative for confirmed pertussis 44% of the time in the study.

“In our cohort, [it] was no better than a coin flip for detecting pertussis,” she said. Also, even when it missed pertussis, it still detected other pathogens, which raises the risk that symptoms might be attributed to a different infection. “This has serious public health implications.”

“The bottom line is, if you are concerned about pertussis, it’s important to use a dedicated pertussis PCR [polymerase chain reaction] assay, and to use comprehensive respiratory pathogen testing only if there are other, specific targets that will change your clinical management,” such as mycoplasma or the flu, Dr. Mayhew said.

In the study, 102 nasopharyngeal swabs positive for pertussis on standalone PCR testing – the university uses an assay from Focus Diagnostics – were thawed and tested with RPAN.

RPAN was negative for pertussis on 45 swabs (44%). “These are the potential missed pertussis cases if RPAN is used alone,” Dr. Mayhew said. RPAN detected other pathogens, such as coronavirus, about half the time, whether or not it tested positive for pertussis. “Those additional pathogens might represent coinfection, but might also represent asymptomatic carriage.” It’s impossible to differentiate between the two, she noted.

In short, “neither positive testing for other respiratory pathogens, nor negative testing for pertussis by RPAN, is reliable for excluding the diagnosis of pertussis. Dedicated pertussis PCR testing should be used for diagnosis,” she and her team concluded.

RPAN also is a PCR test, but with a different, perhaps less robust, genetic target.

The 102 positive swabs were from patients aged 1 month to 73 years, so “it’s important for all of us to keep pertussis on our differential diagnose” no matter how old patients are, Dr. Mayhew said.

Freezing and thawing the swabs shouldn’t have degraded the genetic material, but it might have; that was one of the limits of the study.

The team hopes to run a quality improvement project to encourage the use of standalone pertussis PCR in Ann Arbor.

There was no industry funding. Dr. Mayhew didn’t report any disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Marijuana during prenatal OUD treatment increases premature birth

BALTIMORE – Marijuana is a not a good idea during pregnancy, and it’s an even worse idea when women are being treated for opioid addiction, according to an investigation from East Tennessee State University, Mountain Home.

Marijuana use may become more common as legalization rolls out across the country, and legalization, in turn, may add to the perception that pot is harmless, and maybe a good way to take the edge off during pregnancy and prevent morning sickness, said neonatologist Darshan Shaw, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Shaw wondered how that trend might impact treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy, which has also become more common. The take-home is that “if you have a pregnant patient on medically assistant therapy” for opioid addition, “you should warn them against use of marijuana. It increases the risk of prematurity and low birth weight,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

He and his team reviewed 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals in south-central Appalachia from July 2011 to June 2016. All of the women had used opioids during pregnancy, some illegally and others for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment or other medical issues; 108 had urine screens that were positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at the time of delivery.

Infants were born a mean of 3 days earlier in the marijuana group, and a mean of 265 g lighter. They were also more likely to be born before 37 weeks’ gestation (14% versus 6.5%); born weighing less than 2,500 g (17.6% versus 7.3%); and more likely to be admitted to the neonatal ICU (17.5% versus 7.1%).

On logistic regression to control for parity, maternal status, and tobacco and benzodiazepine use, prenatal marijuana exposure more than doubled the risk of prematurity (odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-4.23); tobacco and benzodiazepines did not increase the risk. Marijuana also doubled the risk of low birth weight (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.18-3.47), about the same as tobacco and benzodiazepines.

The study had limitations. There was no controlling for a major confounder: the amount of opioids woman took while pregnant. These data were not available, Dr. Shaw said.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more common in the marijuana group (33.3% versus 18.1%), so it’s possible that women who used marijuana also used more opioids. “We suspect that opioid exposure was not uniform among all infants,” he said. There were also no data on the amount or way marijuana was used.

Marijuana-positive women were more likely to be unmarried, nulliparous, and use tobacco and benzodiazepines.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Shaw had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Marijuana is a not a good idea during pregnancy, and it’s an even worse idea when women are being treated for opioid addiction, according to an investigation from East Tennessee State University, Mountain Home.

Marijuana use may become more common as legalization rolls out across the country, and legalization, in turn, may add to the perception that pot is harmless, and maybe a good way to take the edge off during pregnancy and prevent morning sickness, said neonatologist Darshan Shaw, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Shaw wondered how that trend might impact treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy, which has also become more common. The take-home is that “if you have a pregnant patient on medically assistant therapy” for opioid addition, “you should warn them against use of marijuana. It increases the risk of prematurity and low birth weight,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

He and his team reviewed 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals in south-central Appalachia from July 2011 to June 2016. All of the women had used opioids during pregnancy, some illegally and others for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment or other medical issues; 108 had urine screens that were positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at the time of delivery.

Infants were born a mean of 3 days earlier in the marijuana group, and a mean of 265 g lighter. They were also more likely to be born before 37 weeks’ gestation (14% versus 6.5%); born weighing less than 2,500 g (17.6% versus 7.3%); and more likely to be admitted to the neonatal ICU (17.5% versus 7.1%).

On logistic regression to control for parity, maternal status, and tobacco and benzodiazepine use, prenatal marijuana exposure more than doubled the risk of prematurity (odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-4.23); tobacco and benzodiazepines did not increase the risk. Marijuana also doubled the risk of low birth weight (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.18-3.47), about the same as tobacco and benzodiazepines.

The study had limitations. There was no controlling for a major confounder: the amount of opioids woman took while pregnant. These data were not available, Dr. Shaw said.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more common in the marijuana group (33.3% versus 18.1%), so it’s possible that women who used marijuana also used more opioids. “We suspect that opioid exposure was not uniform among all infants,” he said. There were also no data on the amount or way marijuana was used.

Marijuana-positive women were more likely to be unmarried, nulliparous, and use tobacco and benzodiazepines.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Shaw had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Marijuana is a not a good idea during pregnancy, and it’s an even worse idea when women are being treated for opioid addiction, according to an investigation from East Tennessee State University, Mountain Home.

Marijuana use may become more common as legalization rolls out across the country, and legalization, in turn, may add to the perception that pot is harmless, and maybe a good way to take the edge off during pregnancy and prevent morning sickness, said neonatologist Darshan Shaw, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Shaw wondered how that trend might impact treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy, which has also become more common. The take-home is that “if you have a pregnant patient on medically assistant therapy” for opioid addition, “you should warn them against use of marijuana. It increases the risk of prematurity and low birth weight,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

He and his team reviewed 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals in south-central Appalachia from July 2011 to June 2016. All of the women had used opioids during pregnancy, some illegally and others for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment or other medical issues; 108 had urine screens that were positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at the time of delivery.

Infants were born a mean of 3 days earlier in the marijuana group, and a mean of 265 g lighter. They were also more likely to be born before 37 weeks’ gestation (14% versus 6.5%); born weighing less than 2,500 g (17.6% versus 7.3%); and more likely to be admitted to the neonatal ICU (17.5% versus 7.1%).

On logistic regression to control for parity, maternal status, and tobacco and benzodiazepine use, prenatal marijuana exposure more than doubled the risk of prematurity (odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-4.23); tobacco and benzodiazepines did not increase the risk. Marijuana also doubled the risk of low birth weight (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.18-3.47), about the same as tobacco and benzodiazepines.

The study had limitations. There was no controlling for a major confounder: the amount of opioids woman took while pregnant. These data were not available, Dr. Shaw said.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more common in the marijuana group (33.3% versus 18.1%), so it’s possible that women who used marijuana also used more opioids. “We suspect that opioid exposure was not uniform among all infants,” he said. There were also no data on the amount or way marijuana was used.

Marijuana-positive women were more likely to be unmarried, nulliparous, and use tobacco and benzodiazepines.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Shaw had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Key clinical point: Warn pregnant women being treated for opioid use disorder to stay away from marijuana.

Major finding: Marijuana use more than doubled the risk of prematurity and low birth weight.

Study details: Review of 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the lead investigator had no disclosures.

Twitter chat recap: Take-homes from LUPUS 2019

Despite negative trial findings, belimumab (Benlysta) remains a valid option for black lupus patients, so long as they have high disease activity and positive serology.

That was just one of the many useful messages from a robust question-and-answer session on Twitter April 23, about important findings from the recent LUPUS 2019 Congress in San Francisco. The Twitter chat was hosted by MDedge Rheumatology and led by Jinoos Yazdany, MD, and Gabriela Schmajuk, MD, both associate professors of rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). The chat included scores of posts from over a dozen participants, most of them rheumatologists, and it’s worth a recap.

The EMBRACE trial

The belimumab EMBRACE trial was the first topic up to bat. The Food and Drug Administration ordered GlaxoSmithKline to conduct the trial as a condition of approval for lupus in 2011; phase 3 trials found no benefit among a small number of black subjects and even a suggestion of harm.

Although lupus is highly prevalent among black people, and outcomes are generally worse, EMBRACE was the first lupus trial to enroll an entirely black population; 345 patients were treated for a year at 10 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks. Inclusion criteria included disease activity scores of at least 8.

Overall, 49% of belimumab patients, and 42% on placebo, had a positive response, which meant a drop of 4 or more disease activity points, among other things. The difference was not statistically significant (P = .11).

However, GSK’s data showed a statistically significant benefit in favor of belimumab among people who entered with a disease activity score of at least 10 (53% vs. 41% for placebo), as well as for those with low complement levels (47% vs. 25%) and both anti–double stranded DNA antibodies and low complement (45% vs. 24%). Response rates were also significantly higher among the 57% of subjects who lived outside of the United States and Canada.

So what to make of the results?

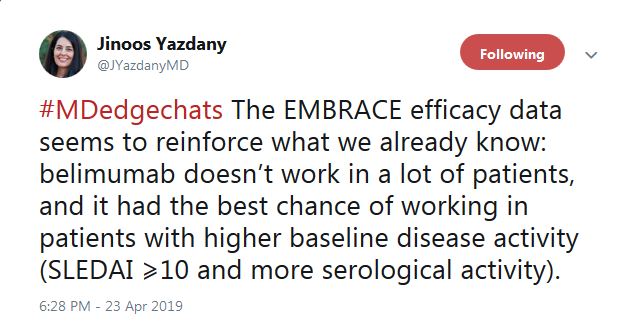

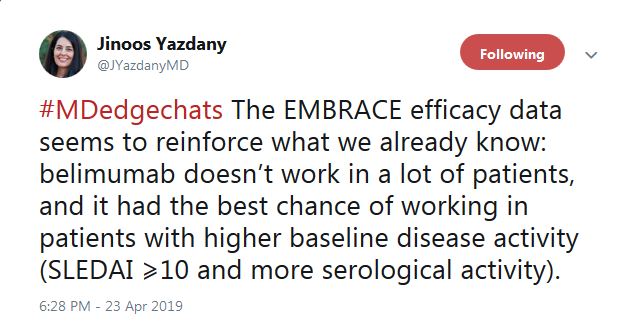

“The EMBRACE efficacy data seems to reinforce what we already know: belimumab doesn’t work in a lot of patients, and it [has] the best chance of working in patients with higher baseline disease activity,” tweeted Dr. Yazdany.

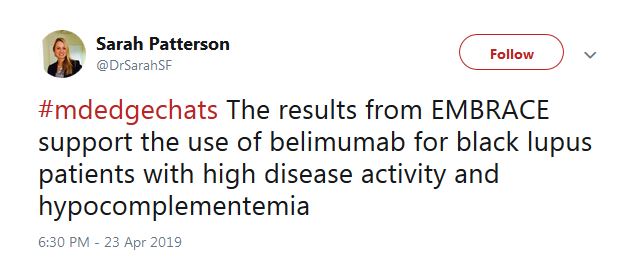

As for prescribing, Sarah Patterson, MD, a postdoctoral fellow in the UCSF Division of Rheumatology, tweeted that the results “support the use of belimumab for black lupus patients with high disease activity” and positive serology.

For those who don’t fit the treatment profile, “we should take care to not over-use it,” said Megan Clowse, MD, an associate professor of rheumatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., in a tweet.

The HCQ adherence fail

Poor hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) adherence came up next on Twitter. The chat participants agreed it’s a huge problem, but no one knows why. Perhaps it’s because patients don’t feel a therapeutic effect or perhaps because GI problems and other side effects are worse than doctors think. Maybe there’s simply not enough social support to encourage people to stay on the drug, even though it’s the single most important medication in lupus.

A nine-study meta-analysis presented at LUPUS 2019 suggested a solution: blood levels. The odds of nonadherence were three times higher in patients below threshold HCQ levels, and although not statistically significant, the mean lupus disease activity index score was more than 3 points higher.

A rheumatologist on the chat said that he’s already checking them.

“We have been measuring HCQ for the past 12 months” at Washington University, St. Louis, according to Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of rheumatology at the school. The data are just now coming in, he said, but it seems to be catching people.

That raised another question on the chat, however: What do you do with people who aren’t down with the program? They’ll be out the door and gone with the wrong words.

“I haven’t figured out the proper tone for when I say ‘So, I see that you haven’t picked up your HCQ in 5 months,’ ” tweeted Dr. Clowse. “It is a really uncomfortable phone call.”

Dr. Kim said that “I ‘gotcha’ them all the time. Guess what typically goes up after they get that 1st HCQ test? Their HCQ levels ... But this rise isn’t durable in our short experience. It goes back down later.”

He tweeted that overall “this is an opportunity to educate patients on the benefits of HCQ ... Most actually do not [know] why they are taking this medication, in our experience.” In another tweet, Dr. Kim said “I tell them I care,” and that checking HCQ levels “is one way of demonstrating how I want to improve their outcomes.”

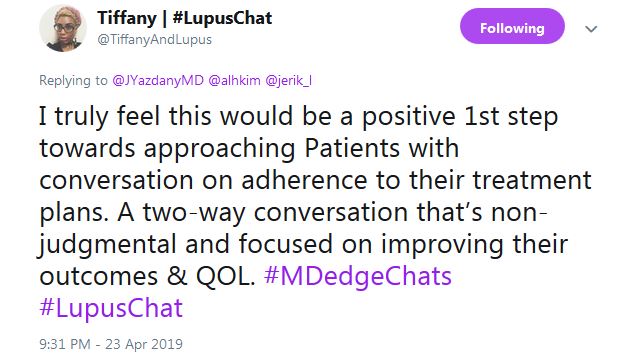

Tiffany from #LupusChat thought that it’s time for doctors to sit down with patient advocates and hash it out. She tweeted that “I truly feel this would be a positive 1st step ... a two-way conversation that’s non-judgmental and focused on improving” outcomes and quality of life.

Baricitinib for lupus?

The final topic was baricitinib (Olumiant).

There were modest indications of benefit at 4 mg/day oral after 6 months in a phase 2 trial with 314 people. There were also serious infections in 6% versus 2% on 2 mg/day and 1% on placebo. One patient in the 4-mg/day arm (1%) developed deep vein thrombosis (DVT), but they were positive for antiphospholipid antibodies, which raise the clot risk.

Baricitinib is FDA approved as second line at 2 mg/day for adult rheumatoid arthritis; there’s a black box warning of malignancies, thrombosis, and serious infections.

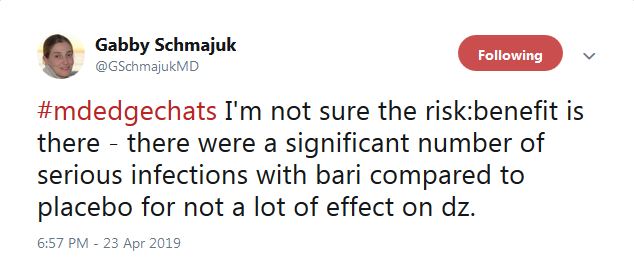

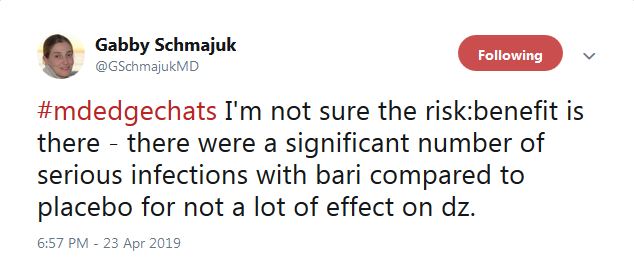

“I’m not sure” the risk-benefit is in the right direction for baricitinib in lupus. “There were a significant number of serious infections ... for not a lot of effect on” disease activity, tweeted the Twitter chat coleader, Dr. Schmajuk. In a separate tweet, she said that, even in nonlupus patients, “we are avoiding [Janus kinase inhibitors] in patients with DVT risk factors. If I were a patient, [I’m] not sure I would want to take the risk.”

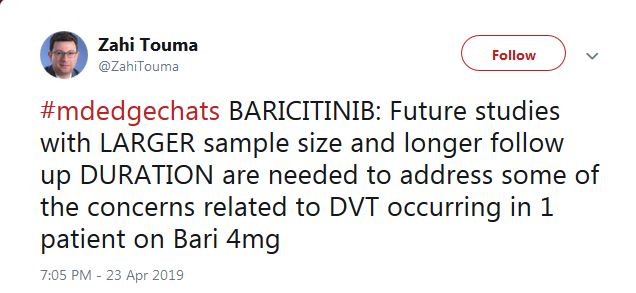

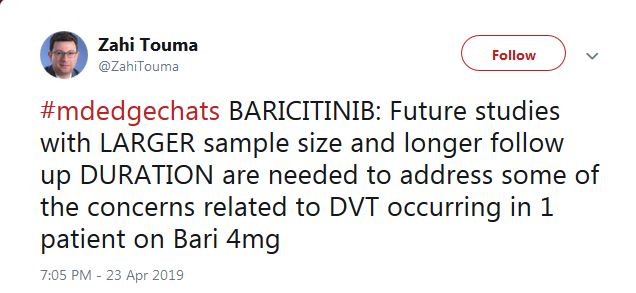

“Future studies with larger sample size and longer follow up ... are needed to address some of the concerns related to DVT,” said Zahi Touma, MD, an assistant professor of rheumatology at the University of Toronto.

Despite negative trial findings, belimumab (Benlysta) remains a valid option for black lupus patients, so long as they have high disease activity and positive serology.

That was just one of the many useful messages from a robust question-and-answer session on Twitter April 23, about important findings from the recent LUPUS 2019 Congress in San Francisco. The Twitter chat was hosted by MDedge Rheumatology and led by Jinoos Yazdany, MD, and Gabriela Schmajuk, MD, both associate professors of rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). The chat included scores of posts from over a dozen participants, most of them rheumatologists, and it’s worth a recap.

The EMBRACE trial

The belimumab EMBRACE trial was the first topic up to bat. The Food and Drug Administration ordered GlaxoSmithKline to conduct the trial as a condition of approval for lupus in 2011; phase 3 trials found no benefit among a small number of black subjects and even a suggestion of harm.

Although lupus is highly prevalent among black people, and outcomes are generally worse, EMBRACE was the first lupus trial to enroll an entirely black population; 345 patients were treated for a year at 10 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks. Inclusion criteria included disease activity scores of at least 8.

Overall, 49% of belimumab patients, and 42% on placebo, had a positive response, which meant a drop of 4 or more disease activity points, among other things. The difference was not statistically significant (P = .11).

However, GSK’s data showed a statistically significant benefit in favor of belimumab among people who entered with a disease activity score of at least 10 (53% vs. 41% for placebo), as well as for those with low complement levels (47% vs. 25%) and both anti–double stranded DNA antibodies and low complement (45% vs. 24%). Response rates were also significantly higher among the 57% of subjects who lived outside of the United States and Canada.

So what to make of the results?

“The EMBRACE efficacy data seems to reinforce what we already know: belimumab doesn’t work in a lot of patients, and it [has] the best chance of working in patients with higher baseline disease activity,” tweeted Dr. Yazdany.

As for prescribing, Sarah Patterson, MD, a postdoctoral fellow in the UCSF Division of Rheumatology, tweeted that the results “support the use of belimumab for black lupus patients with high disease activity” and positive serology.

For those who don’t fit the treatment profile, “we should take care to not over-use it,” said Megan Clowse, MD, an associate professor of rheumatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., in a tweet.

The HCQ adherence fail

Poor hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) adherence came up next on Twitter. The chat participants agreed it’s a huge problem, but no one knows why. Perhaps it’s because patients don’t feel a therapeutic effect or perhaps because GI problems and other side effects are worse than doctors think. Maybe there’s simply not enough social support to encourage people to stay on the drug, even though it’s the single most important medication in lupus.

A nine-study meta-analysis presented at LUPUS 2019 suggested a solution: blood levels. The odds of nonadherence were three times higher in patients below threshold HCQ levels, and although not statistically significant, the mean lupus disease activity index score was more than 3 points higher.

A rheumatologist on the chat said that he’s already checking them.

“We have been measuring HCQ for the past 12 months” at Washington University, St. Louis, according to Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of rheumatology at the school. The data are just now coming in, he said, but it seems to be catching people.

That raised another question on the chat, however: What do you do with people who aren’t down with the program? They’ll be out the door and gone with the wrong words.

“I haven’t figured out the proper tone for when I say ‘So, I see that you haven’t picked up your HCQ in 5 months,’ ” tweeted Dr. Clowse. “It is a really uncomfortable phone call.”

Dr. Kim said that “I ‘gotcha’ them all the time. Guess what typically goes up after they get that 1st HCQ test? Their HCQ levels ... But this rise isn’t durable in our short experience. It goes back down later.”

He tweeted that overall “this is an opportunity to educate patients on the benefits of HCQ ... Most actually do not [know] why they are taking this medication, in our experience.” In another tweet, Dr. Kim said “I tell them I care,” and that checking HCQ levels “is one way of demonstrating how I want to improve their outcomes.”

Tiffany from #LupusChat thought that it’s time for doctors to sit down with patient advocates and hash it out. She tweeted that “I truly feel this would be a positive 1st step ... a two-way conversation that’s non-judgmental and focused on improving” outcomes and quality of life.

Baricitinib for lupus?

The final topic was baricitinib (Olumiant).

There were modest indications of benefit at 4 mg/day oral after 6 months in a phase 2 trial with 314 people. There were also serious infections in 6% versus 2% on 2 mg/day and 1% on placebo. One patient in the 4-mg/day arm (1%) developed deep vein thrombosis (DVT), but they were positive for antiphospholipid antibodies, which raise the clot risk.

Baricitinib is FDA approved as second line at 2 mg/day for adult rheumatoid arthritis; there’s a black box warning of malignancies, thrombosis, and serious infections.

“I’m not sure” the risk-benefit is in the right direction for baricitinib in lupus. “There were a significant number of serious infections ... for not a lot of effect on” disease activity, tweeted the Twitter chat coleader, Dr. Schmajuk. In a separate tweet, she said that, even in nonlupus patients, “we are avoiding [Janus kinase inhibitors] in patients with DVT risk factors. If I were a patient, [I’m] not sure I would want to take the risk.”

“Future studies with larger sample size and longer follow up ... are needed to address some of the concerns related to DVT,” said Zahi Touma, MD, an assistant professor of rheumatology at the University of Toronto.

Despite negative trial findings, belimumab (Benlysta) remains a valid option for black lupus patients, so long as they have high disease activity and positive serology.

That was just one of the many useful messages from a robust question-and-answer session on Twitter April 23, about important findings from the recent LUPUS 2019 Congress in San Francisco. The Twitter chat was hosted by MDedge Rheumatology and led by Jinoos Yazdany, MD, and Gabriela Schmajuk, MD, both associate professors of rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). The chat included scores of posts from over a dozen participants, most of them rheumatologists, and it’s worth a recap.

The EMBRACE trial

The belimumab EMBRACE trial was the first topic up to bat. The Food and Drug Administration ordered GlaxoSmithKline to conduct the trial as a condition of approval for lupus in 2011; phase 3 trials found no benefit among a small number of black subjects and even a suggestion of harm.

Although lupus is highly prevalent among black people, and outcomes are generally worse, EMBRACE was the first lupus trial to enroll an entirely black population; 345 patients were treated for a year at 10 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks. Inclusion criteria included disease activity scores of at least 8.

Overall, 49% of belimumab patients, and 42% on placebo, had a positive response, which meant a drop of 4 or more disease activity points, among other things. The difference was not statistically significant (P = .11).

However, GSK’s data showed a statistically significant benefit in favor of belimumab among people who entered with a disease activity score of at least 10 (53% vs. 41% for placebo), as well as for those with low complement levels (47% vs. 25%) and both anti–double stranded DNA antibodies and low complement (45% vs. 24%). Response rates were also significantly higher among the 57% of subjects who lived outside of the United States and Canada.

So what to make of the results?

“The EMBRACE efficacy data seems to reinforce what we already know: belimumab doesn’t work in a lot of patients, and it [has] the best chance of working in patients with higher baseline disease activity,” tweeted Dr. Yazdany.

As for prescribing, Sarah Patterson, MD, a postdoctoral fellow in the UCSF Division of Rheumatology, tweeted that the results “support the use of belimumab for black lupus patients with high disease activity” and positive serology.

For those who don’t fit the treatment profile, “we should take care to not over-use it,” said Megan Clowse, MD, an associate professor of rheumatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., in a tweet.

The HCQ adherence fail

Poor hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) adherence came up next on Twitter. The chat participants agreed it’s a huge problem, but no one knows why. Perhaps it’s because patients don’t feel a therapeutic effect or perhaps because GI problems and other side effects are worse than doctors think. Maybe there’s simply not enough social support to encourage people to stay on the drug, even though it’s the single most important medication in lupus.

A nine-study meta-analysis presented at LUPUS 2019 suggested a solution: blood levels. The odds of nonadherence were three times higher in patients below threshold HCQ levels, and although not statistically significant, the mean lupus disease activity index score was more than 3 points higher.

A rheumatologist on the chat said that he’s already checking them.

“We have been measuring HCQ for the past 12 months” at Washington University, St. Louis, according to Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of rheumatology at the school. The data are just now coming in, he said, but it seems to be catching people.

That raised another question on the chat, however: What do you do with people who aren’t down with the program? They’ll be out the door and gone with the wrong words.

“I haven’t figured out the proper tone for when I say ‘So, I see that you haven’t picked up your HCQ in 5 months,’ ” tweeted Dr. Clowse. “It is a really uncomfortable phone call.”

Dr. Kim said that “I ‘gotcha’ them all the time. Guess what typically goes up after they get that 1st HCQ test? Their HCQ levels ... But this rise isn’t durable in our short experience. It goes back down later.”

He tweeted that overall “this is an opportunity to educate patients on the benefits of HCQ ... Most actually do not [know] why they are taking this medication, in our experience.” In another tweet, Dr. Kim said “I tell them I care,” and that checking HCQ levels “is one way of demonstrating how I want to improve their outcomes.”

Tiffany from #LupusChat thought that it’s time for doctors to sit down with patient advocates and hash it out. She tweeted that “I truly feel this would be a positive 1st step ... a two-way conversation that’s non-judgmental and focused on improving” outcomes and quality of life.

Baricitinib for lupus?

The final topic was baricitinib (Olumiant).

There were modest indications of benefit at 4 mg/day oral after 6 months in a phase 2 trial with 314 people. There were also serious infections in 6% versus 2% on 2 mg/day and 1% on placebo. One patient in the 4-mg/day arm (1%) developed deep vein thrombosis (DVT), but they were positive for antiphospholipid antibodies, which raise the clot risk.

Baricitinib is FDA approved as second line at 2 mg/day for adult rheumatoid arthritis; there’s a black box warning of malignancies, thrombosis, and serious infections.

“I’m not sure” the risk-benefit is in the right direction for baricitinib in lupus. “There were a significant number of serious infections ... for not a lot of effect on” disease activity, tweeted the Twitter chat coleader, Dr. Schmajuk. In a separate tweet, she said that, even in nonlupus patients, “we are avoiding [Janus kinase inhibitors] in patients with DVT risk factors. If I were a patient, [I’m] not sure I would want to take the risk.”

“Future studies with larger sample size and longer follow up ... are needed to address some of the concerns related to DVT,” said Zahi Touma, MD, an assistant professor of rheumatology at the University of Toronto.

FROM LUPUS 2019

Measuring hydroxychloroquine blood levels could inform safe, optimal dosing

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to an investigation of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, an ongoing longitudinal study of lupus patients in the Baltimore area.

As innocuous as the assertions seem, they are anything but. They directly contradict a 2014 investigation from Kaiser Permanente that put the retinopathy risk after 20 years at almost 40%; that finding led directly to an American Academy of Ophthalmology recommendation to reduce the maximum hydroxychloroquine dose from 6.5 mg/kg per day ideal weight to 5 mg/kg real weight, where it remains to this day.

Meanwhile, very few rheumatologists have access to hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) blood levels because most commercial labs don’t offer them. Plasma testing is widely available, but it’s nowhere near as good, according to Michelle Petri, MD, a rheumatology professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; director of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort; and a respected authority on lupus management.

“The Kaiser Permanente study was very worrisome,” she said. “I remember that I thought it didn’t fit my practice at all; I don’t see 40%. It made me even more concerned when the ophthalmologists” reduced the dose, “because hydroxychloroquine is the most important medicine I have for my lupus patients; it is the only one that improves survival. We don’t want to scare our patients into thinking that 40% of them are going to have retinopathy.”

Dueling studies

Dr. Petri’s concerns led her and her team to launch their own investigation; they followed 537 Baltimore cohort members on HCQ as they went through eye exams by Hopkins retinopathy specialists, often with optical coherence tomography (OCT). With a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 84%, OCT is the best screening method available.

“We found that the risk of retinopathy is not nearly as high as Kaiser Permanente found,” just 11.46% (11/96) with 16-20 years of use, and 8% (6/75) with 21 or more years. On average, “the risk is probably about 10% after 16 or more years, not 40%,” Dr. Petri said at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

Patients with “possible” retinopathy were not included in the analysis.

When asked for comment, Ronald Melles, MD, a Kaiser ophthalmologist in Redwood City, Calif.; one of the two authors on the Kaiser study; and an author on the subsequent AAO recommendations, stood by his work.

“A rate of 12% retinopathy after 16 years of use ... seems right in line with what we found.” However, “the fact that the rate went down to 8%” after 20 years does not make sense; “the longer you are on the medicine, the more likely you would be to develop the toxicity,” he said.

Maybe the fluctuation had to do with the fact that there were only 75 patients in the Hopkins study on HCQ past 20 years, whereas “we looked at 2,361 patients, and 238 were on the medication for” 20 years or more. Patients over 5.0 mg/kg per day had a 5.67-fold higher risk”of retinopathy, he said (univariate analysis, P less than .001).

Dr. Petri wasn’t buying it. The across the board recommendation was made “without any recognition that if you reduce the dose, you reduce the benefit,” she said.

A new referee: blood levels

Dr. Petri and her team also found that HCQ blood levels correlated with retinopathy, and it was a direct relationship. Patients in the highest maximum tertile (1,753-6,281 ng/mL) had a retinopathy rate of 6.7%, a good deal higher than patients in lower tertiles. It was the same story with the highest mean tertile (1,117-3,513 ng/mL). Retinopathy in that group occurred in 7.9% versus 3.7% or less in lower tertiles. The findings were statistically significant.

Patients in the third tertile “are at the greatest risk, so I reduce their dose,” but “I do not want to reduce the dose across the board” to 5 mg/kg per day; that’s overreach. The tertile approach, if it pans out, might be a better way, she said.

The problem with plasma levels is that HCQ binds to red blood cells, so plasma levels are artificially low and do not indicate the true HCQ load. For now, just one company in the United States offers HCQ blood levels: Exagen.

“We have to get the big companies to start offering” this, and “I want rheumatologists to adopt it. I am lucky at Hopkins [because] we have our own homegrown blood level assay,” she said.

Dr. Melles agreed that tracking blood level makes sense, “but the literature I am aware of has not been able to closely correlate either lupus disease activity or retinal toxicity with blood levels. Also, we have seen some patients at lower doses develop toxicity and other patients on higher doses without any detectable changes.”

Still, “we would like to see [this] studied more, perhaps with newer analytic methods,” said his coauthor on the Kaiser study, and also the lead author on the AAO guidelines, Michael Marmor, MD, professor emeritus of ophthalmology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

In the end, on the same team

Dr. Petri said there is interest among some of her fellow members of the American College of Rheumatology to work with AAO to revise the guidelines. “Until then,” she said, “I want the ophthalmologists to withdraw” them.

She’s worried about undertreatment and believes that the previous AAO guideline, up to 6.5 mg/kg per day ideal weight, was fine, “with some understanding that there are high-risk groups, such as the elderly and people with renal impairment, where the dose should be reduced.”

“No matter how obese a patient is, I cap it at 400 mg/day,” she said, and, with the luxury of HCQ blood level testing, “no matter the weight, if the person is in the upper tertile, I reduce the dose.”

Dr. Marmor agreed that “if rheumatologists prescribe 5 mg/kg real weight and do not stress compliance, some patients may indeed be underdosed.”

“However, that is a fault of the doctor and patient relationship,” he said, “not the guideline; we do not feel it ethical to prescribe higher doses which could increase toxicity in reliable patients ... just because some patients might be unreliable.”

Overall, “I have not heard complaints from rheumatologists in our area, who try hard to follow the current recommendations. ... any doctor can use the dose he or she feels is necessary for a patient. Several recent reports [also] suggest the incidence of toxicity is falling now with usage of AAO guidelines, [and] I am not aware of any data” showing that management has become less effective, he said.

In the meantime, “I assure you that AAO wants ... to serve both specialties, and will change the guidelines when there is new, defensible data,” he added.

The Hopkins team found that the risk of HCQ retinopathy was highest in men and white patients, as well as older people. Body mass index and hypertension also predicted retina issues.

“As screening tests are frequently abnormal due to causes other than HCQ ... stopping [it] based on an abnormal test without confirmation from a retinopathy expert could needlessly deprive an SLE patient of an important medication,” they said.

The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is funded by the National Institutes of Health. The physicians didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCES: Petri M et al. Lupus Sci Med. 2019;6(suppl 1). Abstracts 15 and 16.

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to an investigation of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, an ongoing longitudinal study of lupus patients in the Baltimore area.

As innocuous as the assertions seem, they are anything but. They directly contradict a 2014 investigation from Kaiser Permanente that put the retinopathy risk after 20 years at almost 40%; that finding led directly to an American Academy of Ophthalmology recommendation to reduce the maximum hydroxychloroquine dose from 6.5 mg/kg per day ideal weight to 5 mg/kg real weight, where it remains to this day.

Meanwhile, very few rheumatologists have access to hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) blood levels because most commercial labs don’t offer them. Plasma testing is widely available, but it’s nowhere near as good, according to Michelle Petri, MD, a rheumatology professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; director of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort; and a respected authority on lupus management.

“The Kaiser Permanente study was very worrisome,” she said. “I remember that I thought it didn’t fit my practice at all; I don’t see 40%. It made me even more concerned when the ophthalmologists” reduced the dose, “because hydroxychloroquine is the most important medicine I have for my lupus patients; it is the only one that improves survival. We don’t want to scare our patients into thinking that 40% of them are going to have retinopathy.”

Dueling studies

Dr. Petri’s concerns led her and her team to launch their own investigation; they followed 537 Baltimore cohort members on HCQ as they went through eye exams by Hopkins retinopathy specialists, often with optical coherence tomography (OCT). With a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 84%, OCT is the best screening method available.

“We found that the risk of retinopathy is not nearly as high as Kaiser Permanente found,” just 11.46% (11/96) with 16-20 years of use, and 8% (6/75) with 21 or more years. On average, “the risk is probably about 10% after 16 or more years, not 40%,” Dr. Petri said at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

Patients with “possible” retinopathy were not included in the analysis.

When asked for comment, Ronald Melles, MD, a Kaiser ophthalmologist in Redwood City, Calif.; one of the two authors on the Kaiser study; and an author on the subsequent AAO recommendations, stood by his work.

“A rate of 12% retinopathy after 16 years of use ... seems right in line with what we found.” However, “the fact that the rate went down to 8%” after 20 years does not make sense; “the longer you are on the medicine, the more likely you would be to develop the toxicity,” he said.

Maybe the fluctuation had to do with the fact that there were only 75 patients in the Hopkins study on HCQ past 20 years, whereas “we looked at 2,361 patients, and 238 were on the medication for” 20 years or more. Patients over 5.0 mg/kg per day had a 5.67-fold higher risk”of retinopathy, he said (univariate analysis, P less than .001).