User login

Utilization and Cost of Veterans Health Administration Referrals to Community Care-Based Physical Therapy

Utilization and Cost of Veterans Health Administration Referrals to Community Care-Based Physical Therapy

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health system, providing care to veterans through VHA and non-VHA practitioners and facilities.1,2 Providing high-quality, timely, and veteran-centric care remains a priority for the VHA. Legislative efforts have expanded opportunities for eligible veterans to receive care in the community purchased by VHA, known as community care (CC).1 The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 came in response to reports of long wait times and drive times for patients.3-5 The MISSION Act of 2018 expanded access to CC by streamlining it and broadening eligibility criteria, especially for veterans in rural communities who often experience more barriers in accessing care than veterans living in urban communities.1,6-10 Since the implementation of the Choice and MISSION Acts, > 2.7 million veterans have received care through community practitioners within the VHA CC network.11

Background

Increased access to CC could benefit veterans living in rural communities by increasing care options and circumventing challenges to accessing VHA care (ie, geographic, transportation, and distance barriers, practitioner and specialist shortages, and hospital closures). 5,9,10,12,13 However, health care system deficits in rural areas could also limit CC effectiveness for veterans living in those communities. 3 Other challenges posed by using CC include care coordination, information sharing, care continuity, delayed payments to CC practitioners, and mixed findings regarding CC quality.5,8,13,14 VHA practitioners are specifically trained to meet the multifaceted needs unique to veterans’ health and subculture, training CC practitioners may not receive.5,15

CC offers services for primary care and a broad range of specialties, including rehabilitation services such as physical therapy (PT).6 PT is used for the effective treatment of various conditions veterans experience and promote wellbeing and independence.16 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) databases reveal a high prevalence of veterans receiving PT services through CC; PT is one of the most frequently used CC outpatient specialty services by veterans living in rural communities.14,17

Telerehabitltation Enterprisewide Initiative

VHA has greatly invested in delivering care virtually, especially for veterans living in rural communities.18 In 2017, the VHA Office of Rural Health funded the Telerehabilitation Enterprise-Wide Initiative (TR-EWI) in partnership with the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Services national program office to increase access to specialized rehabilitation services for veterans living in rural communities by leveraging telehealth technologies.18-21 This alternative mode of health care delivery allows clinicians to overcome access barriers by delivering rehabilitation therapies directly to veterans' homes or nearby community-based outpatient clinics. TR-EWI was conceived as a hub-and-spoke model, where rehabilitation expertise at the hub was virtually delivered to spoke sites that did not have in-house expertise. In subsequent years, the TR-EWI also evolved to provide targeted telerehabilitation programs within rural-serving community-based outpatient clinics, including PT as a predominant service.19,20

As TR-EWI progressed—and in conjunction with the uptake of telehealth across VHA during the COVID-19 pandemic—there has been increased focus on PT telerehabilitation, especially for the 4.6 million veterans in rural communities.18,22,23 Because health care delivery system deficits in rural areas could limit the effective use of CC, many TR-EWI sites hope to reduce their CC referrals by providing telehealth PT services to veterans who might otherwise need to be referred to CC. This strategy aligns with VHA goals of providing high-quality and timely care. To better understand opportunities for programs like TR-EWI to provide rehabilitation services for veterans and reduce care sent to the community, research that examines CC referral trends for PT over time is warranted.

This study examines CC from a rehabilitation perspective with a focus on CC referral trends for PT, specifically for Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) where TREWI sites are located. The study’s objectives were to describe rehabilitation PT services being referred to CC and examine associated CC costs for PT services. Two research questions guided the study. First, what are the utilization trends for CC PT referrals from fiscal year (FY) 2019 to FY 2022? Secondly, what is the cost breakdown of CC for PT referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022?

Methods

This study was conducted by a multidisciplinary team comprised of public health, disability, rehabilitation counseling, and PT professionals. It was deemed a quality improvement project under VA guidance and followed the SQUIRE guidelines for quality improvement reporting.24,25 The study used the VA Common Operating Platform (Palantir) to obtain individual-level CC referral data from the HealthShare Referral Manager (HSRM) database and consult data from the Computerized Patient Record System. Palantir is used to store and integrate VA data derived from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and VHA Support Service Center. Referrals are authorizations for care to be delivered by a CC practitioner.

TR-EWI is comprised of 7 sites: VISN 2, VISN 4, VISN 8, VISN 12, VISN 15, VISN 19, and VISN 22. Each site provides telerehabilitation services with an emphasis on reaching veterans living in rural communities. We joined the referrals and consults cubes in Palantir to extract PT referrals for FY 2019 to FY 2022 for the 7 VISNs with TR-EWI sites and obtain referral-specific information and demographic characteristics. 26 Data were extracted in October 2022.

The VHA Community Care Referral Dashboard (CC Dashboard) provided nonindividual level CC cost data.27 The CC Dashboard provides insights into the costs of CC services for VHA enrollees by category of care, standardized episode of care, and eligibility. Data are based on nationallevel HSRM referrals that are not suspended or linked to a canceled or discontinued consult. Data were aggregated by VISN. The dashboard only includes referrals dating back to FY 2020; therefore, PT data from FY 2020 through FY 2022 for VISNs with TR-EWI sites were collected. Data were extracted in December 2022.

This study examined CC referrals, station name, eligibility types, clinical diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes), and demographic information in the Palantir dataset. Six eligibility criteria can qualify a veteran to receive CC.28 Within clinical diagnoses, the variable of interest was the provisional diagnosis. Patient demographics included age, gender, and rurality of residence, as determined by the Rural-Urban Commuting Area system.29,30 Rural and highly rural categories were combined for analysis. For the CC cost dataset, this study examined CC referrals, referral cost, and eligibility type.

Analysis

For the first research question, we examined referral data from FY 2019 to FY 2022 using the Palantir dataset, performed descriptive statistical analysis for all variables, and analyzed data to identify trends. Descriptive statistics were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 29.0.0.0.

A qualitative analysis of provisional diagnosis data revealed what is being referred to CC for PT. A preliminary overview of provisional diagnosis data was conducted to familiarize coders with the data. We developed a coding framework to categorize diagnoses based on anatomical location, body structure, and clinical areas of interest. Data were reviewed individually and grouped into categories within the coding framework before meeting as a team to achieve group consensus on categorization. We then totaled the frequency of occurrence for provisional diagnoses within each category. Qualitative analyses were completed using Microsoft Excel.

For the second research question, the study used the CC cost dataset to examine the cost breakdown of CC PT referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022. We calculated the number and cost of PT referrals across eligibility groups for each FY and VISN. Data were analyzed using SPSS to identify cost trends.

Results

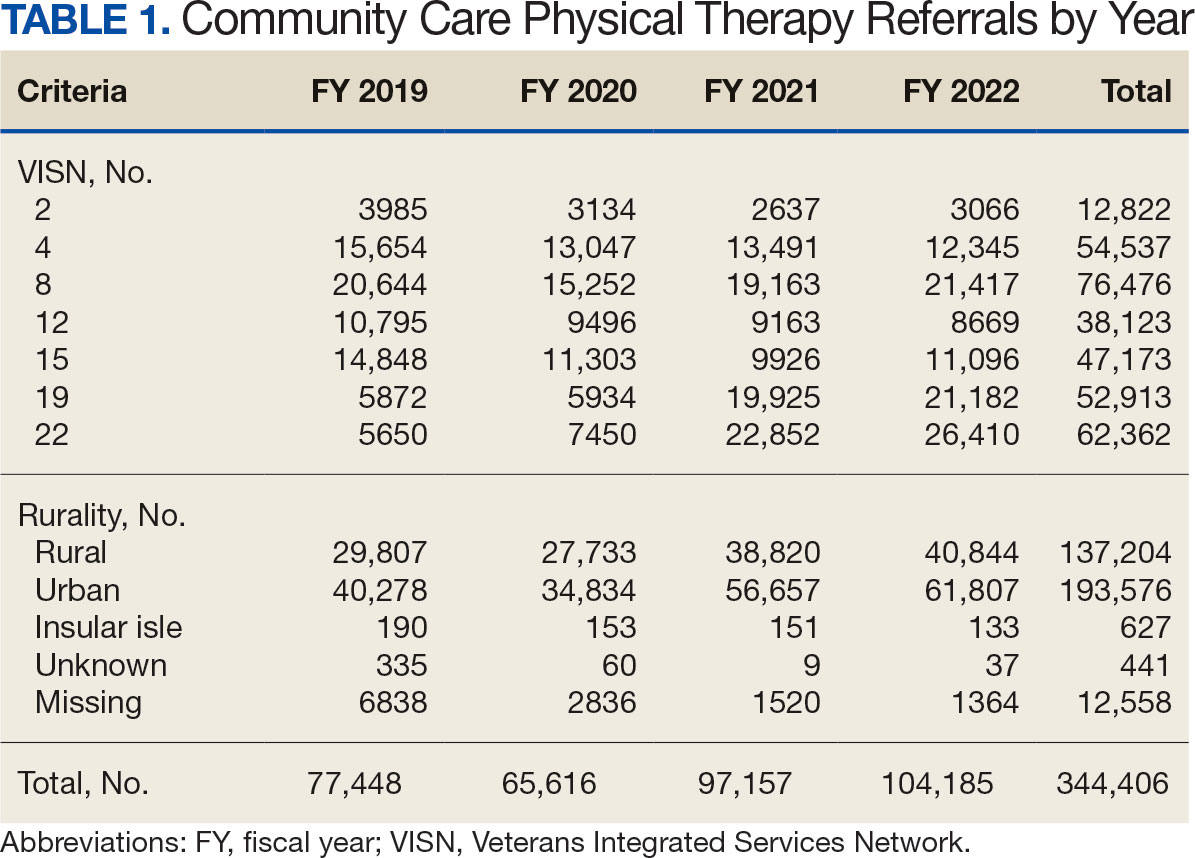

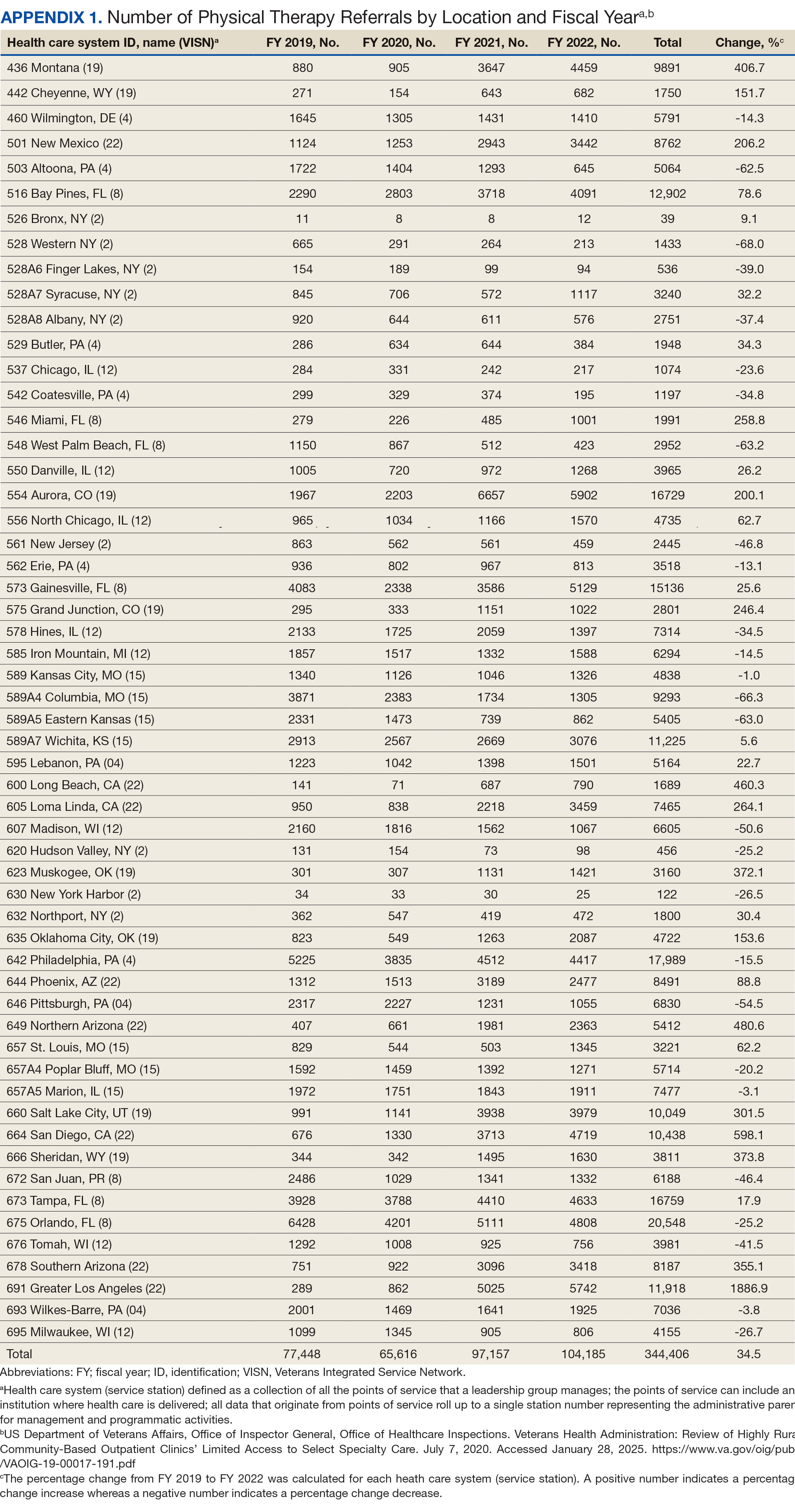

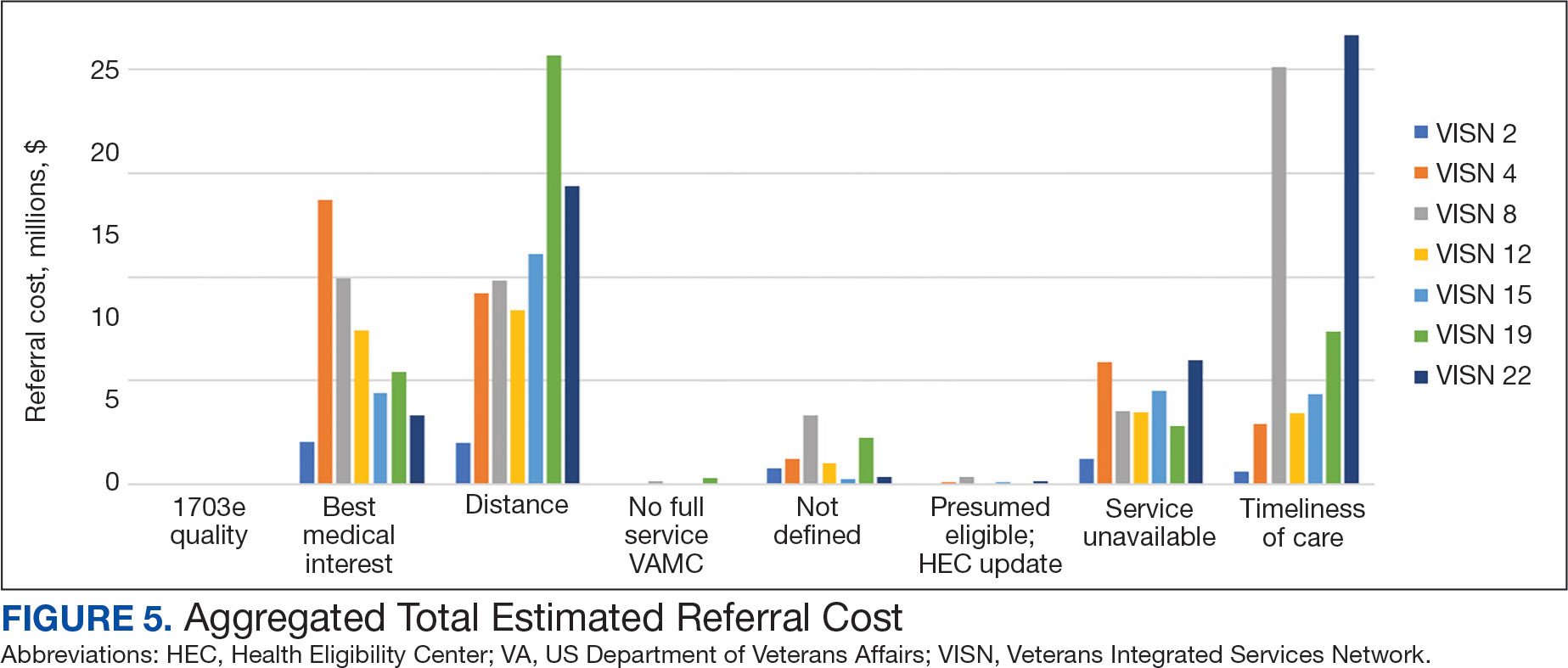

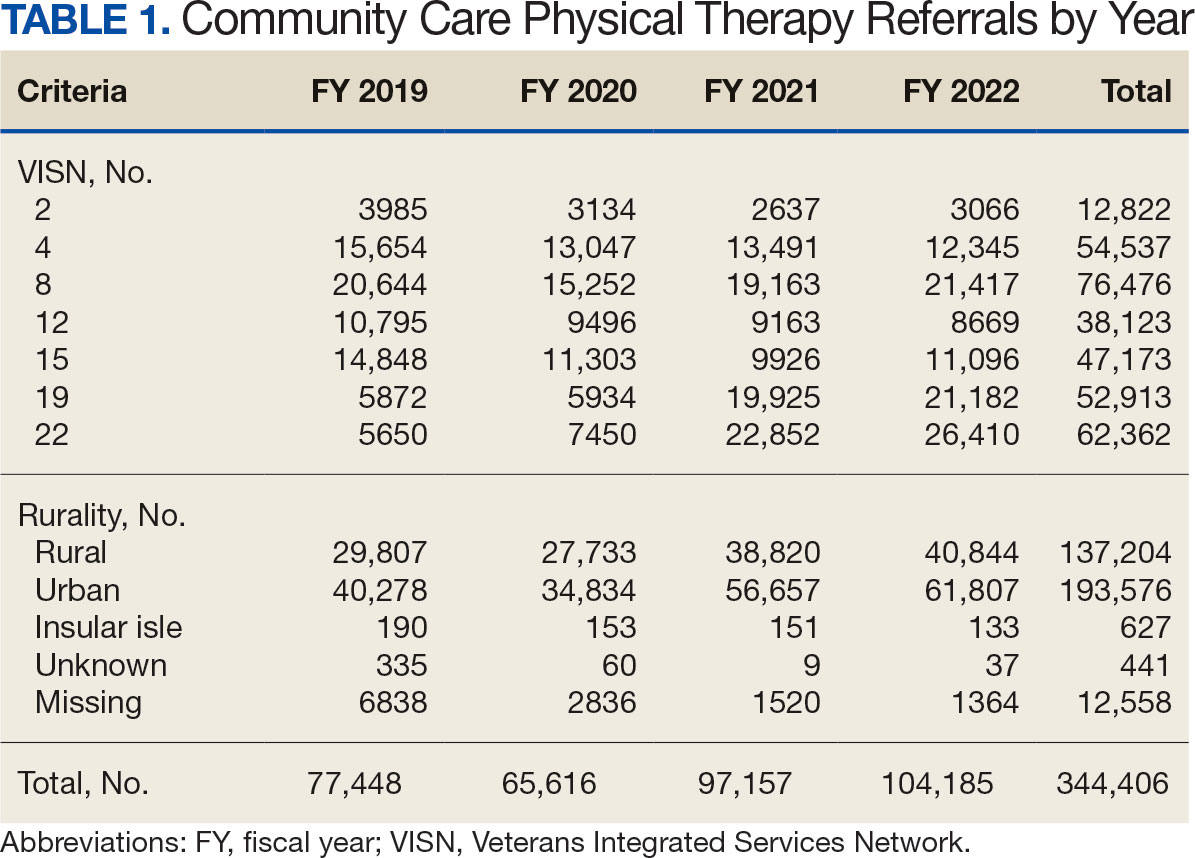

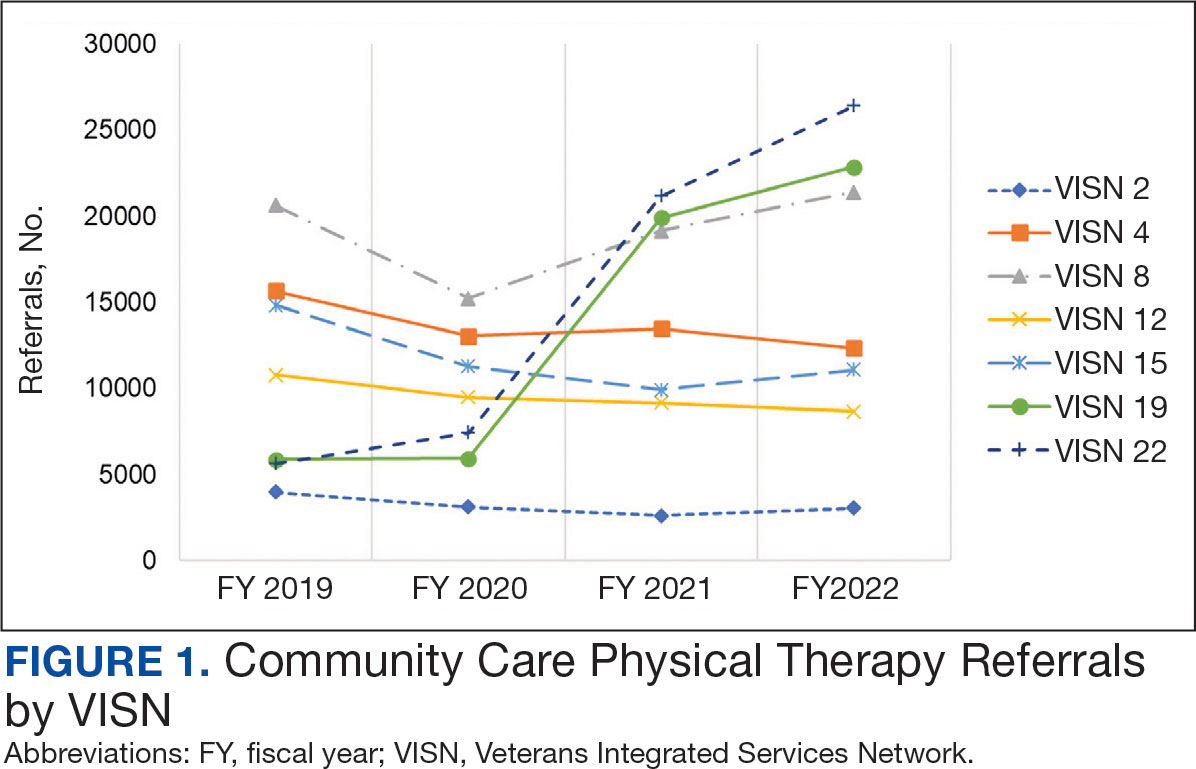

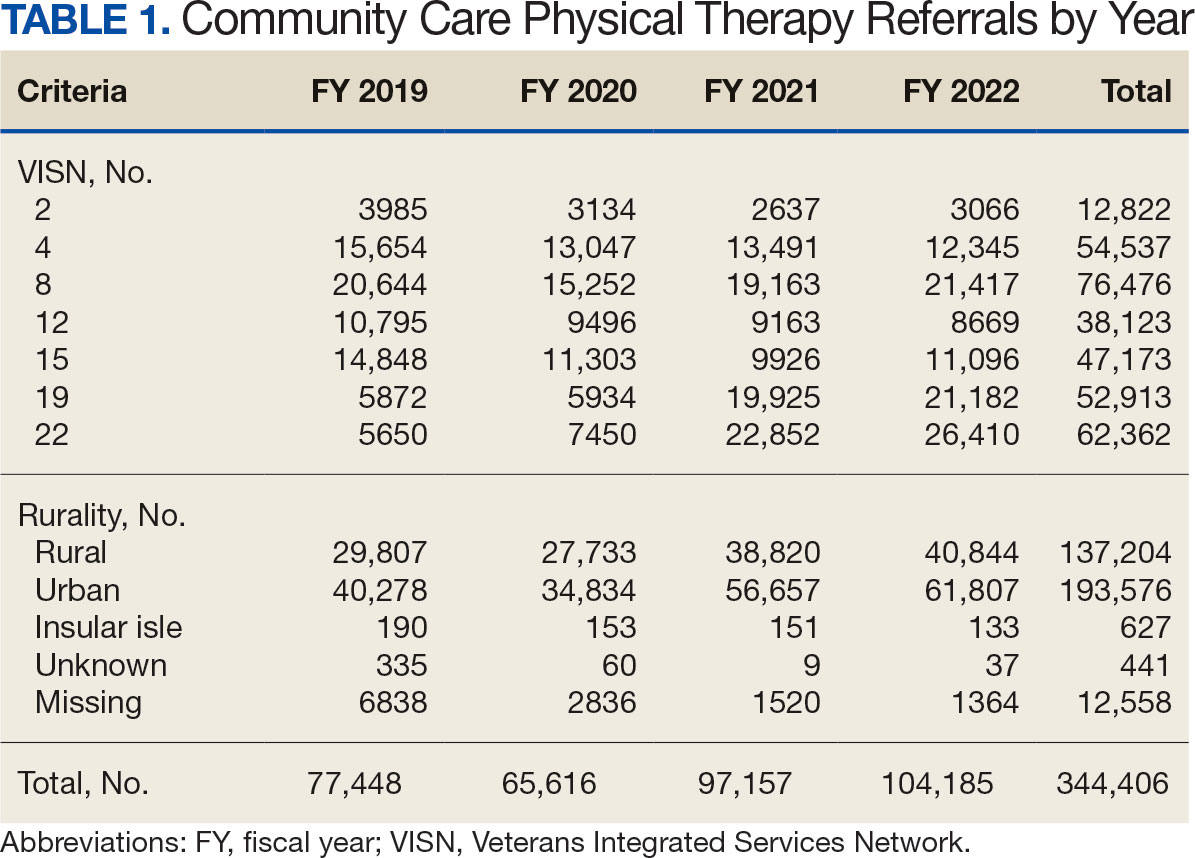

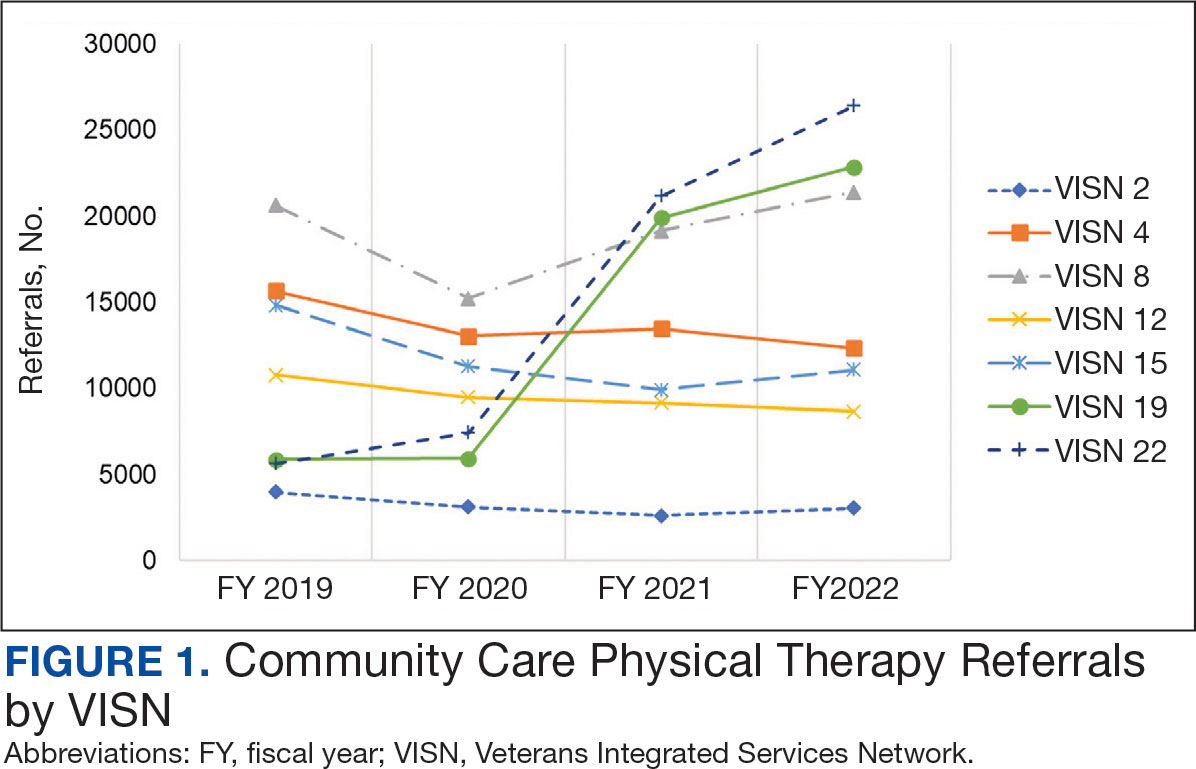

There were 344,406 referrals to CC for PT from FY 2019 to FY 2022 for the 7 VISNs analyzed (Table 1). Of these, 22.5% were from FY 2019, 19.1% from FY 2020, 28.2% from FY 2021, and 30.3% from FY 2022. VISN 8 and VISN 22 reported the most overall PT referrals, with VISN 8 comprising 22.2% and VISN 22 comprising 18.1% of all referrals. VISN 2 reported the least overall referrals (3.7%). VISN 4 and VISN 12 had decreases in referrals over time. VISN 2 and VISN 15 had decreases in referrals from FY 2019 to FY 2021 and slight increases from FY 2021 to FY 2022. VISN 19 and VISN 22 both saw slight increases from FY 2019 to FY 2020 and substantial increases from FY 2020 to FY 2022, with FY 2022 accounting for 40.0% and 42.3% of all referrals for VISN 19 and VISN 20, respectively (Figure 1).

For FY 2019 and FY 2020, VISN 8 had the highest percentage of referrals (26.7% and 23.2%, respectively), whereas VISN 22 was among the lowest (7.3% and 11.4%, respectively). However, for FY 2021 and FY 2022, VISN 22 reported the highest percentage of referrals (23.5% and 25.3%, respectively) compared to all other VISNs. VISN 2 consistently reported the lowest percentage of referrals across all years.

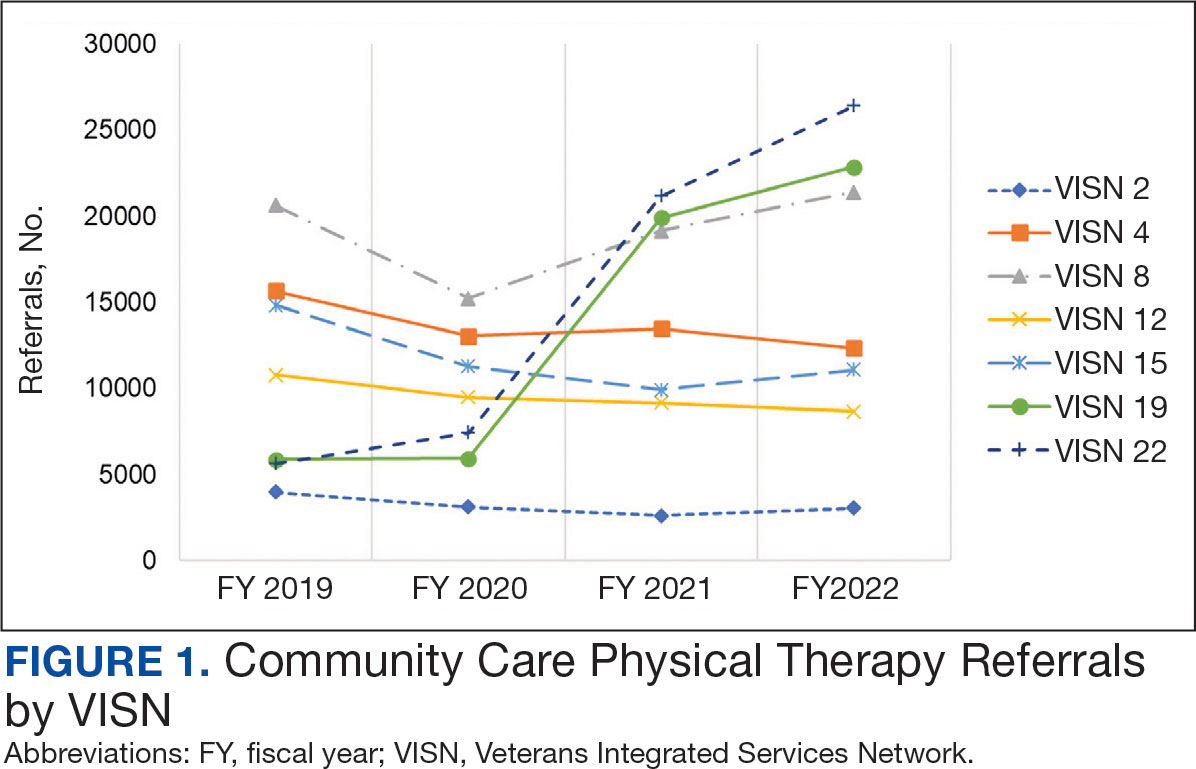

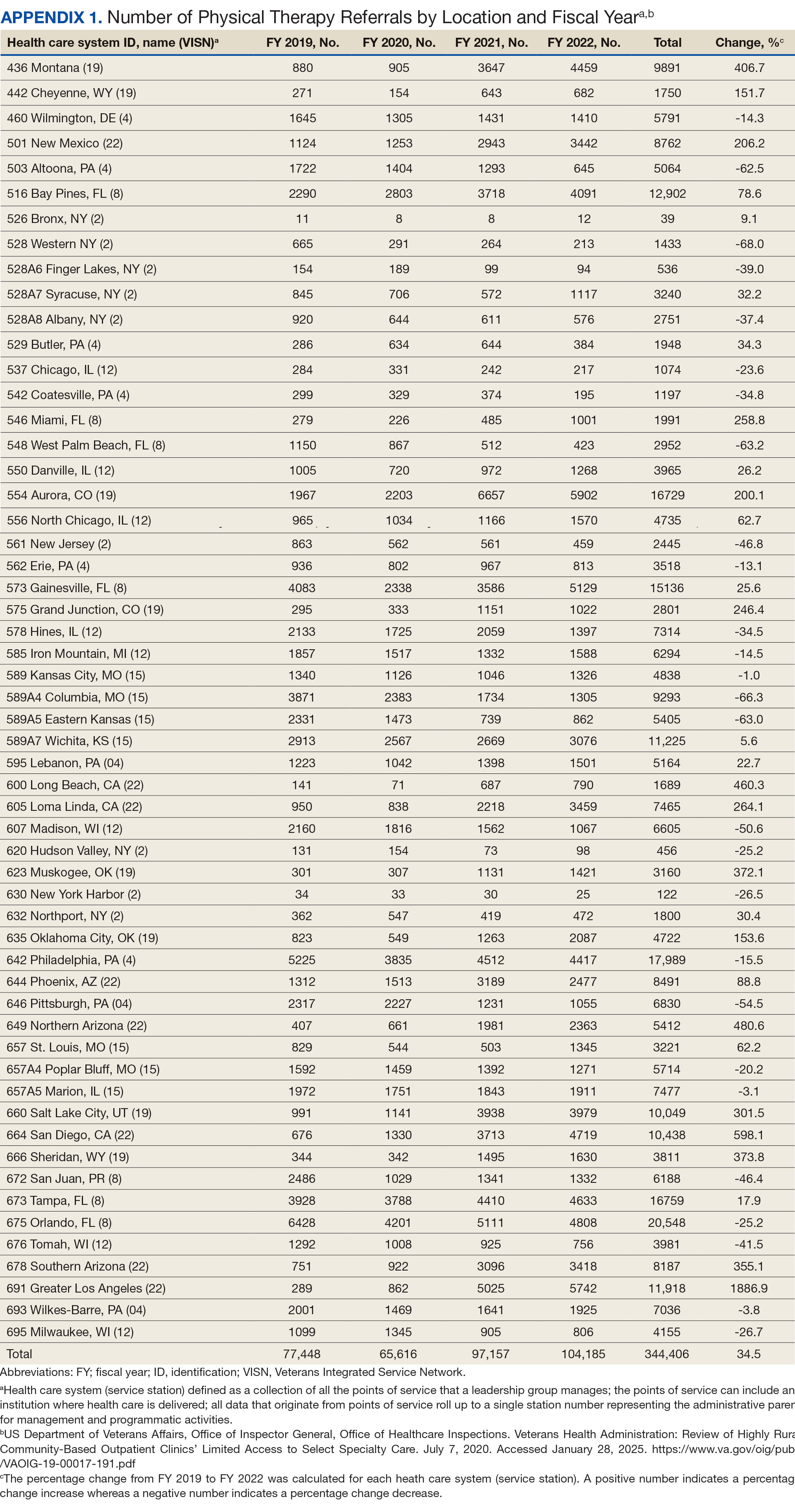

There were 56 stations analyzed across the 7 VISNs (Appendix 1). Nine stations each accounted for ≥ 3.0% of the total PT referrals and only 2 stations accounted for > 5.0% of referrals. Orlando, Florida (6.0%), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (5.2%), Tampa, Florida (4.9%), Aurora, Colorado (4.9%), and Gainesville, Florida (4.4%) reported the top 5 highest referrals, with 3 being from VISN 8 (Orlando, Tampa, Gainesville). Stations with the lowest reported referrals were all in VISN 2 in New York: The Bronx, (0%), New York Harbor (0%), Hudson Valley (0.1%) and Finger Lakes (0.2%).

Rurality

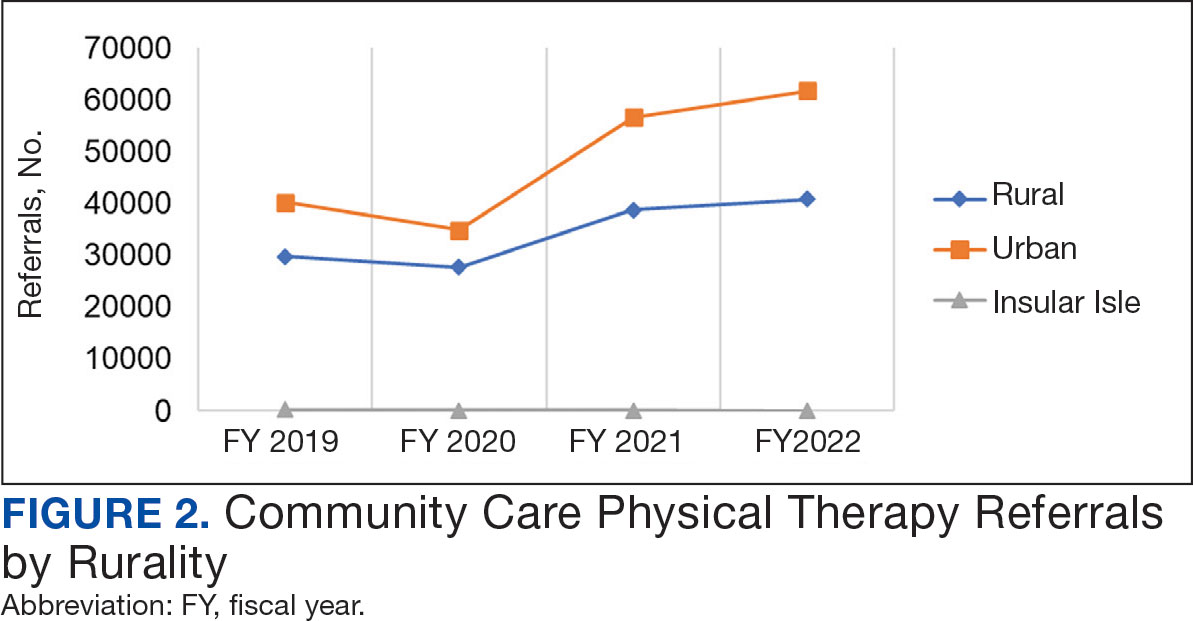

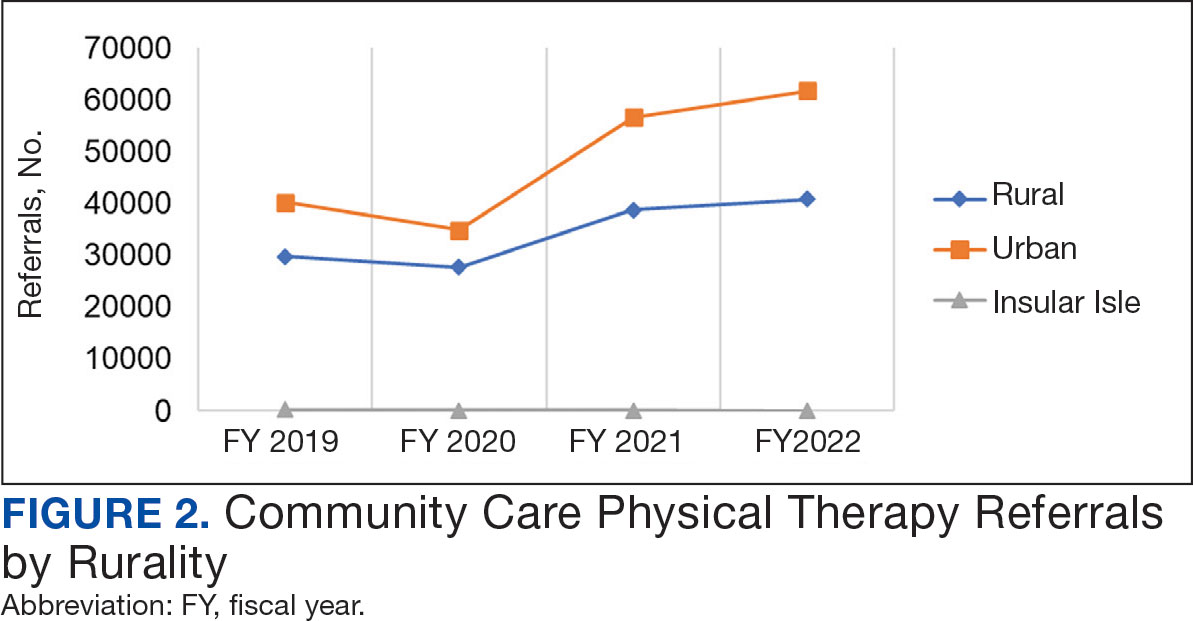

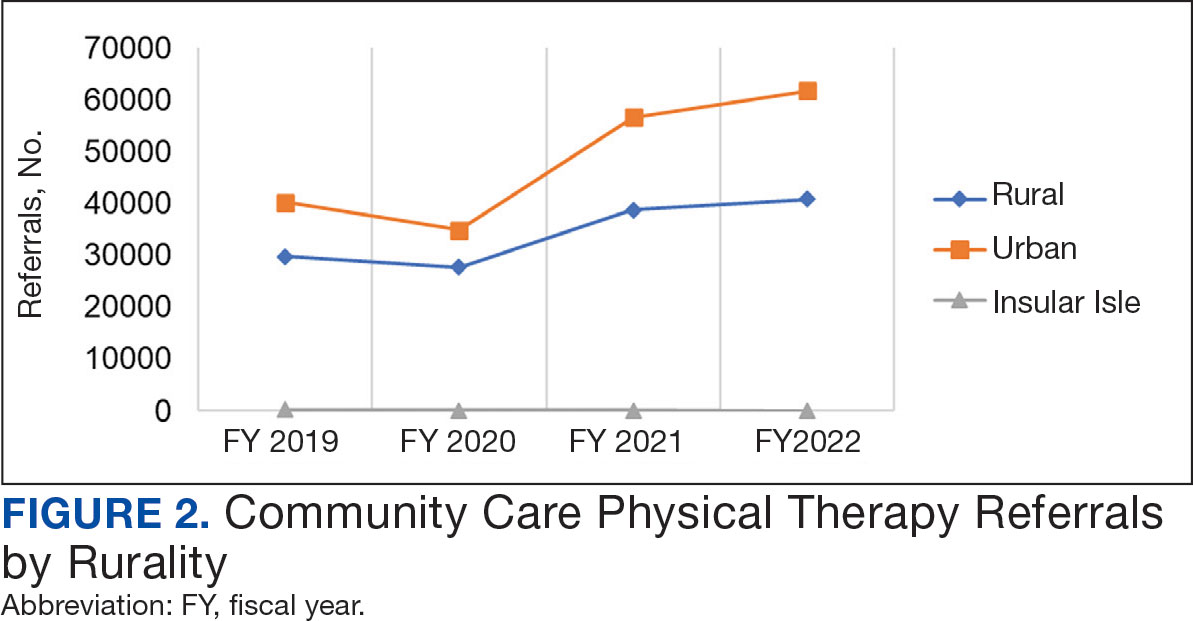

Urban stations comprised 56.2% and rural stations comprised 39.8% of PT CC referrals, while 0.2% of referrals were from insular isle US territories: Guam, American Samoa, Northern Marianas, and the Virgin Islands. The sample had missing or unknown data for 3.8% of referrals. FY 2022 had the largest difference in rural and urban referrals. Additionally, there was an overall trend of more referrals over time for rural and urban, with a large increase in rural (+40.0%) and urban (+62.7%) referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2021 and a modest increase from FY 2021 to FY 2022 (+5.2% for rural and +9.1% for urban). There was a decrease in rural (-7.0%) and urban (-3.5%) referrals from FY 2019 to FY 2020 (Figure 2).

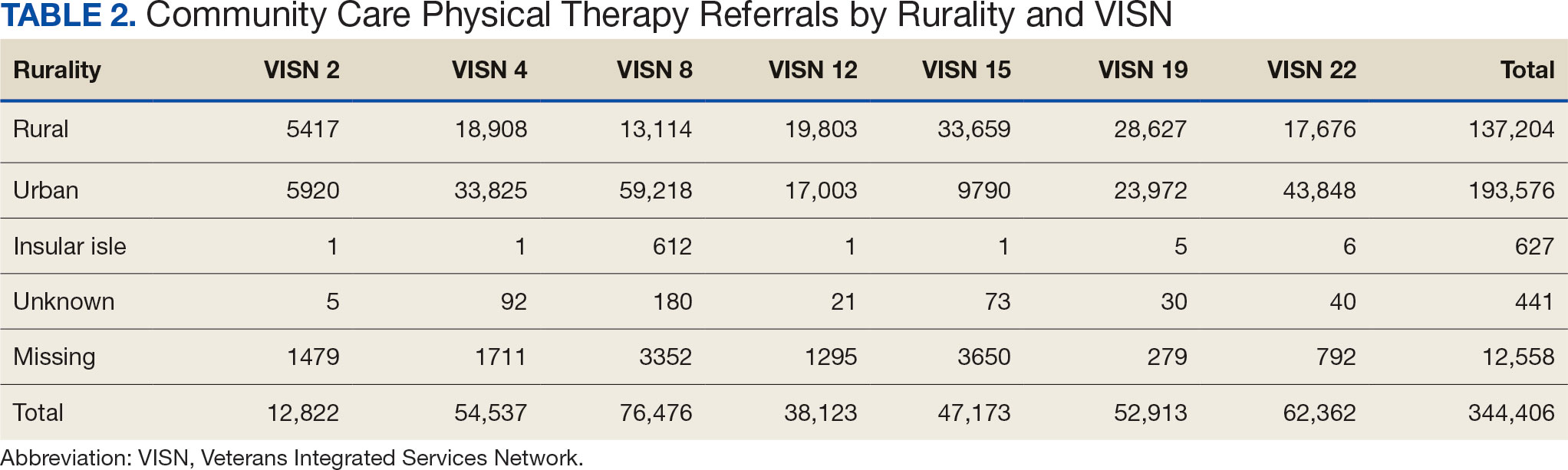

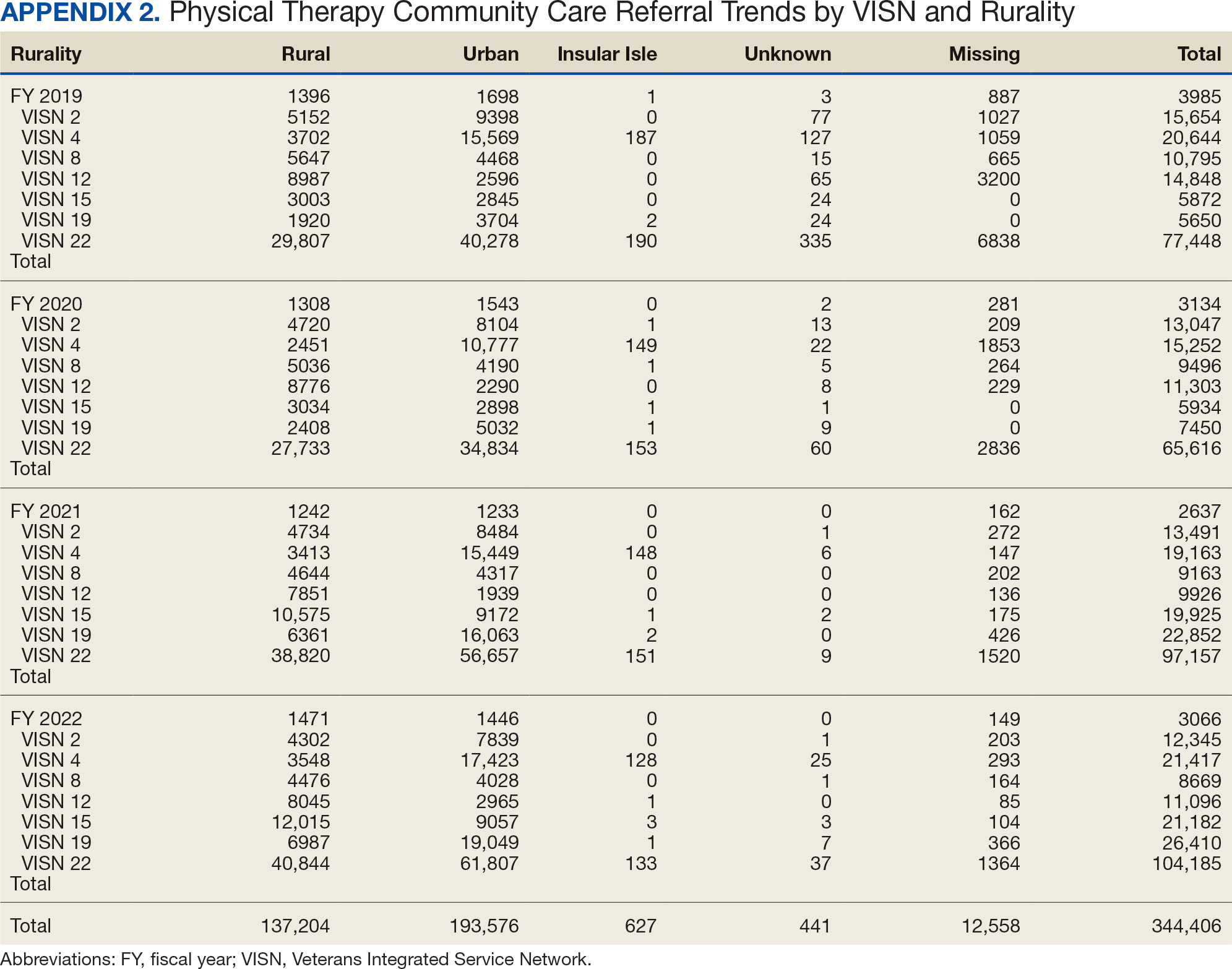

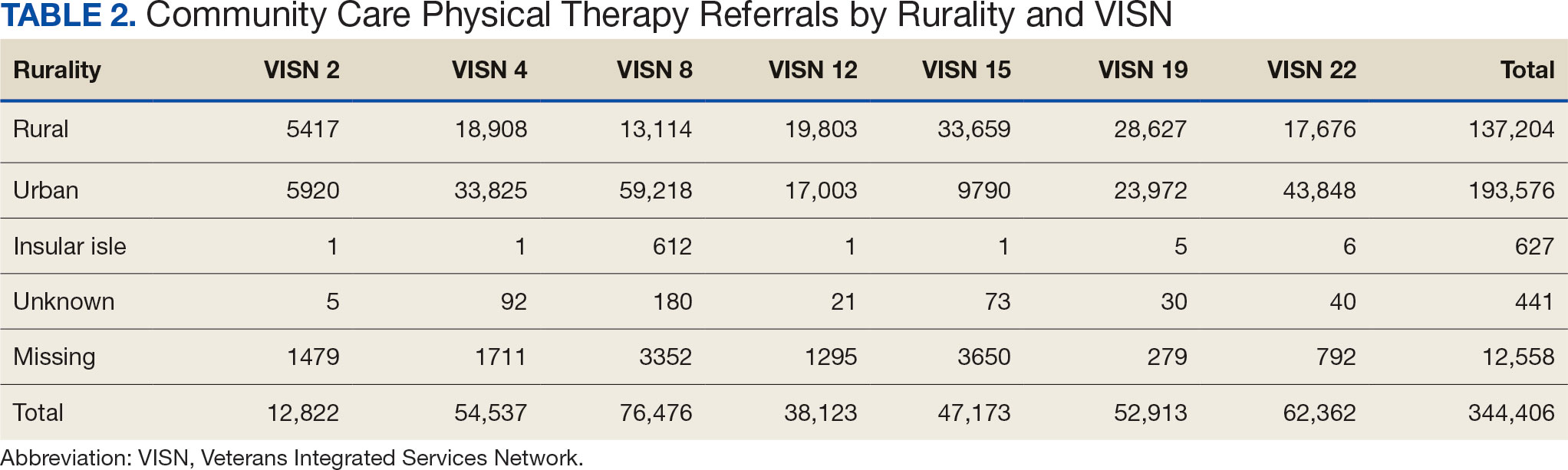

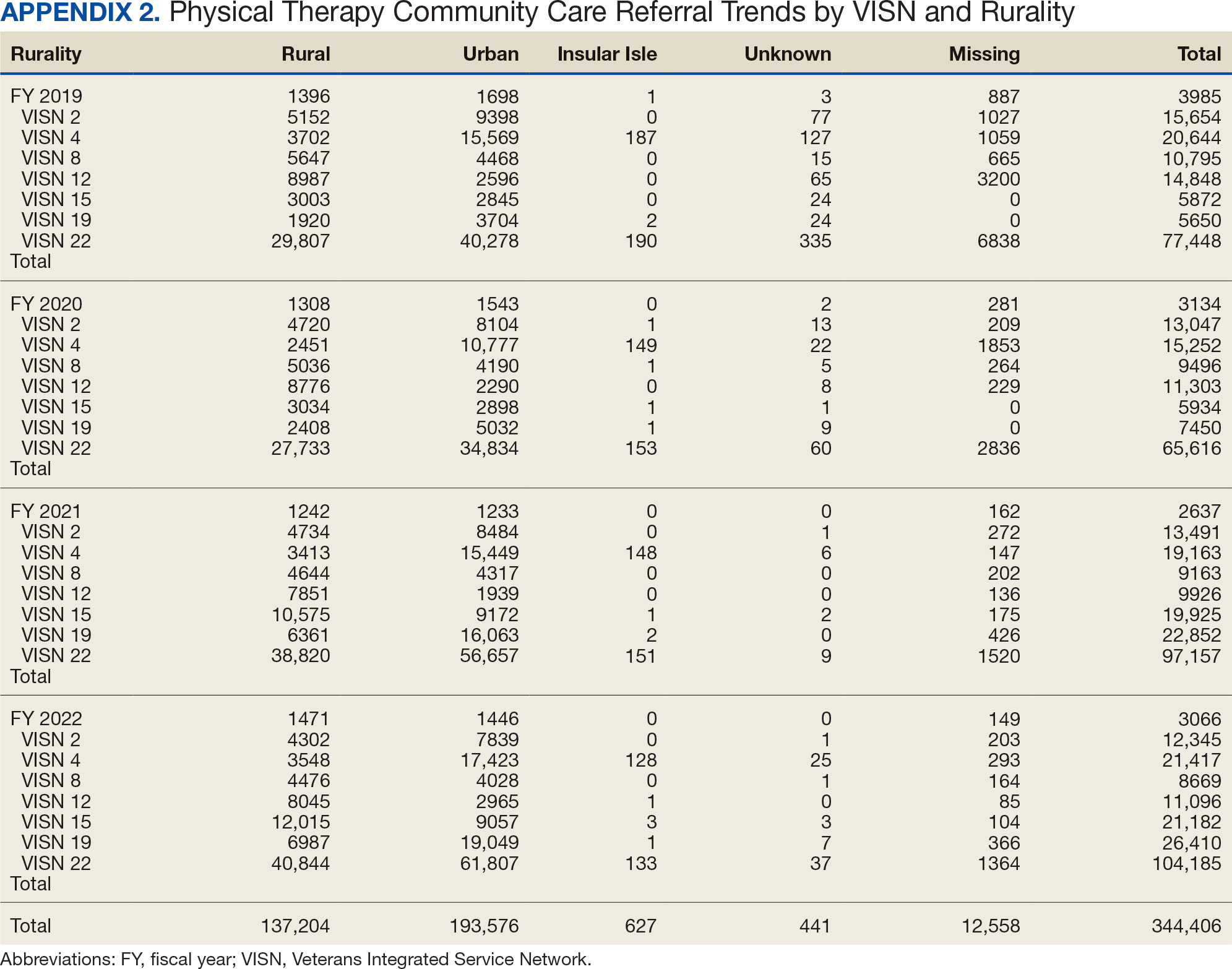

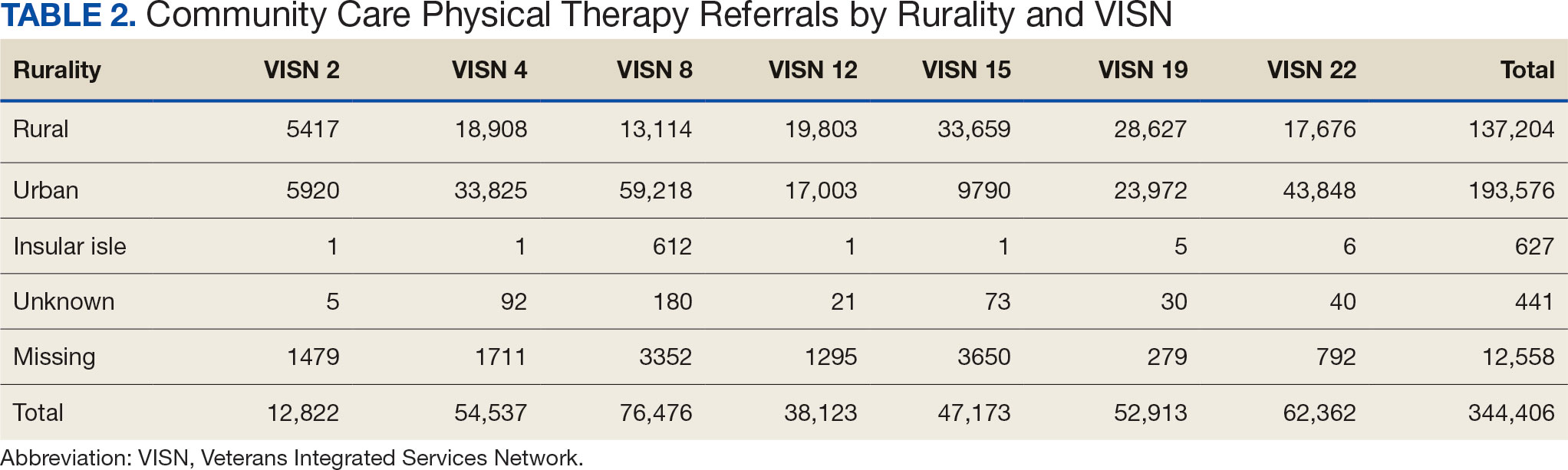

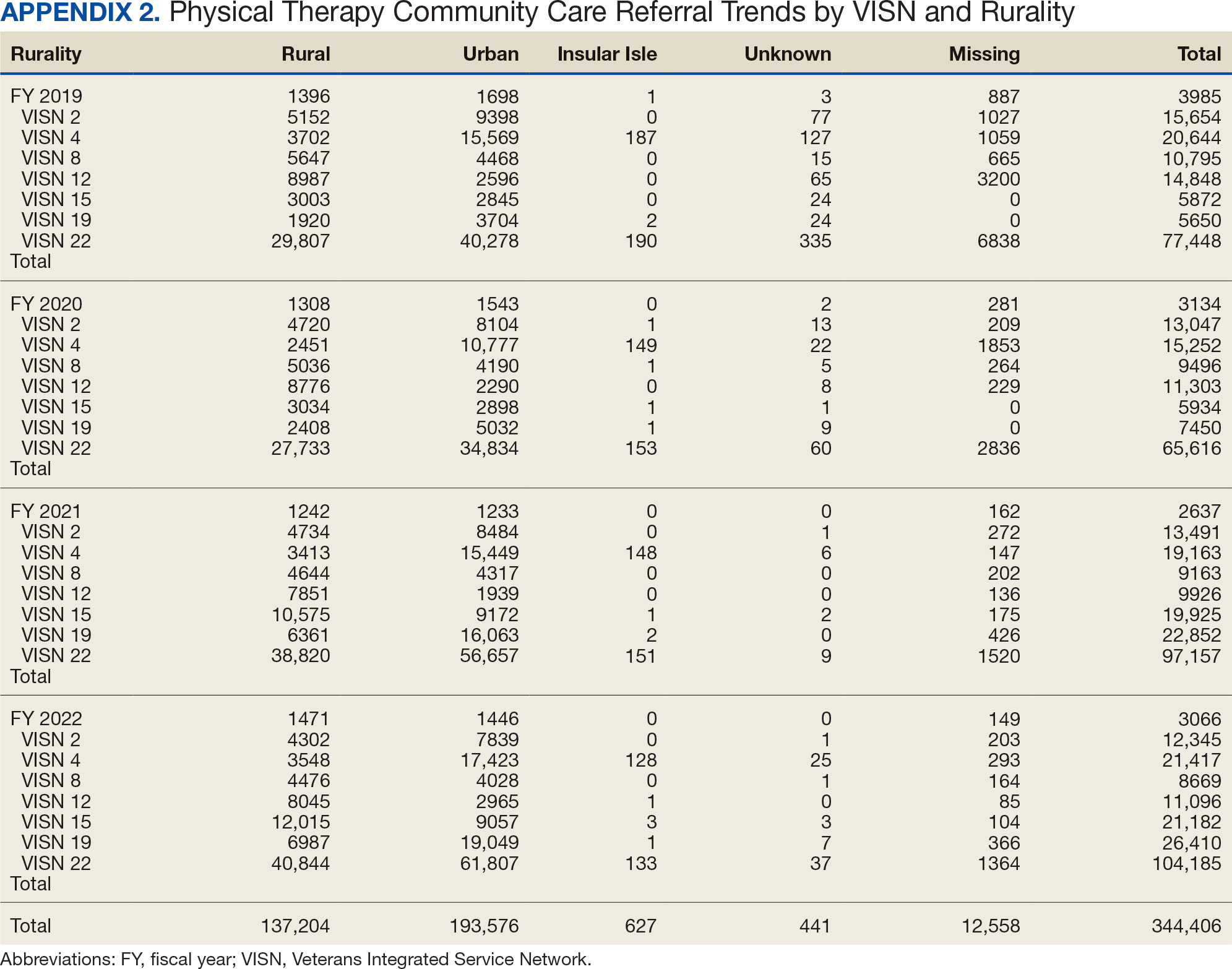

There were differences in referrals by rurality and VISN (Table 2). VISN 12, VISN 15, and VISN 19 reported more rural than urban referrals, whereas VISN 4, VISN 8, and VISN 22 reported more urban than rural referrals. VISN 2 reported similar numbers for both, with slightly more urban than rural referrals. When reviewing trends over time for each FY, VISN 12, VISN 15, and VISN 19 reported more rural than urban referrals and VISN 4, VISN 8, and VISN 22 had more urban than rural referrals. In FY 2019 and FY 2020, VISN 2 reported slightly more urban than rural referrals but almost the same number of referrals in FY 2021 and FY 2022 (Appendix 2).

Demographics

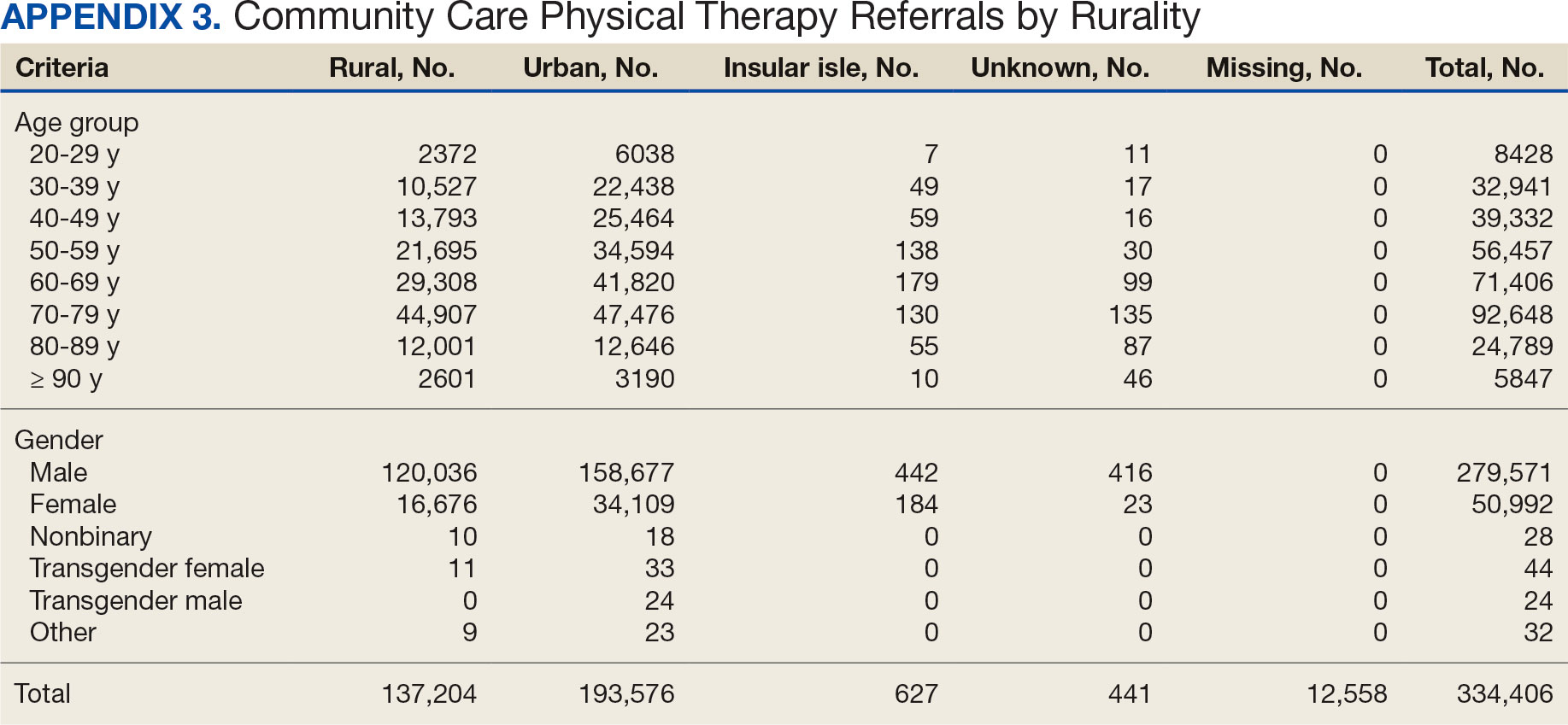

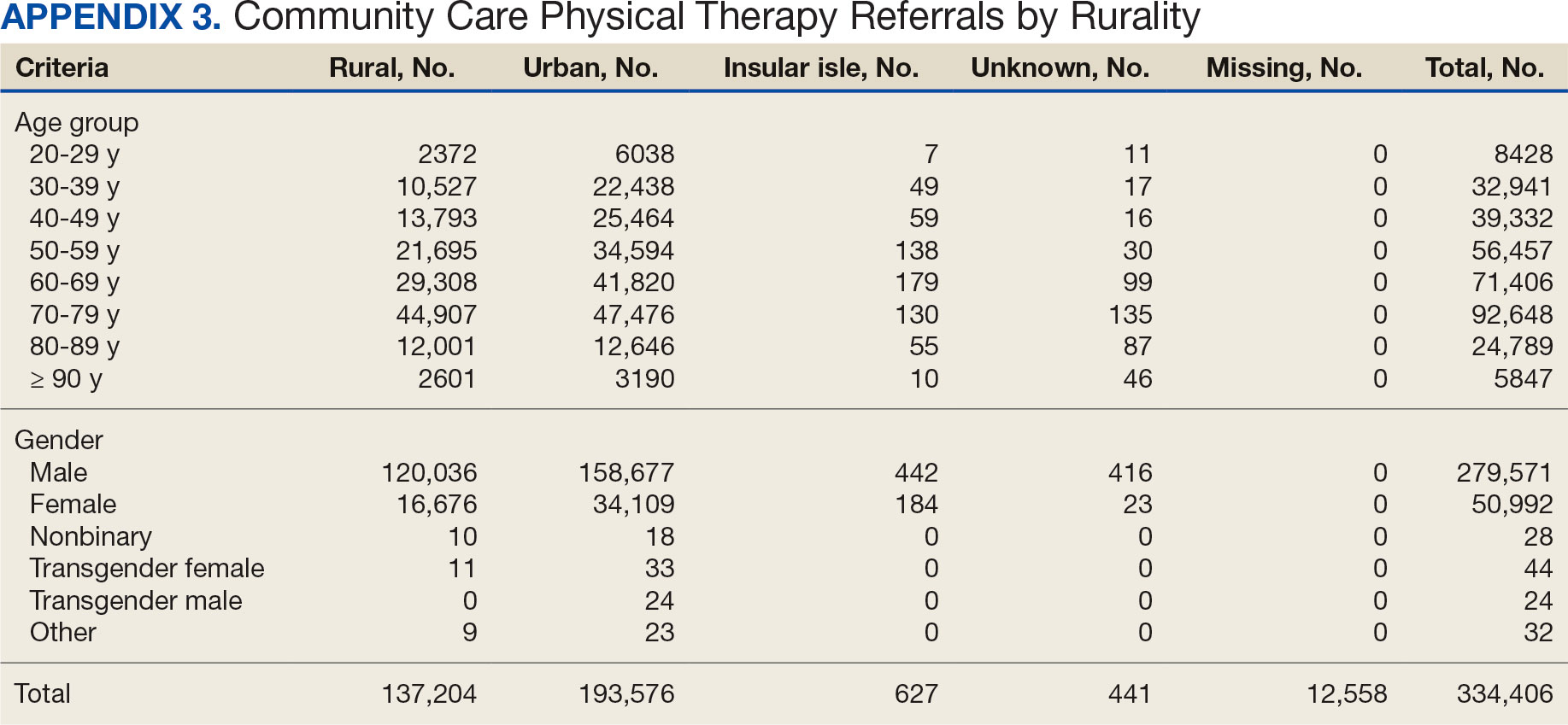

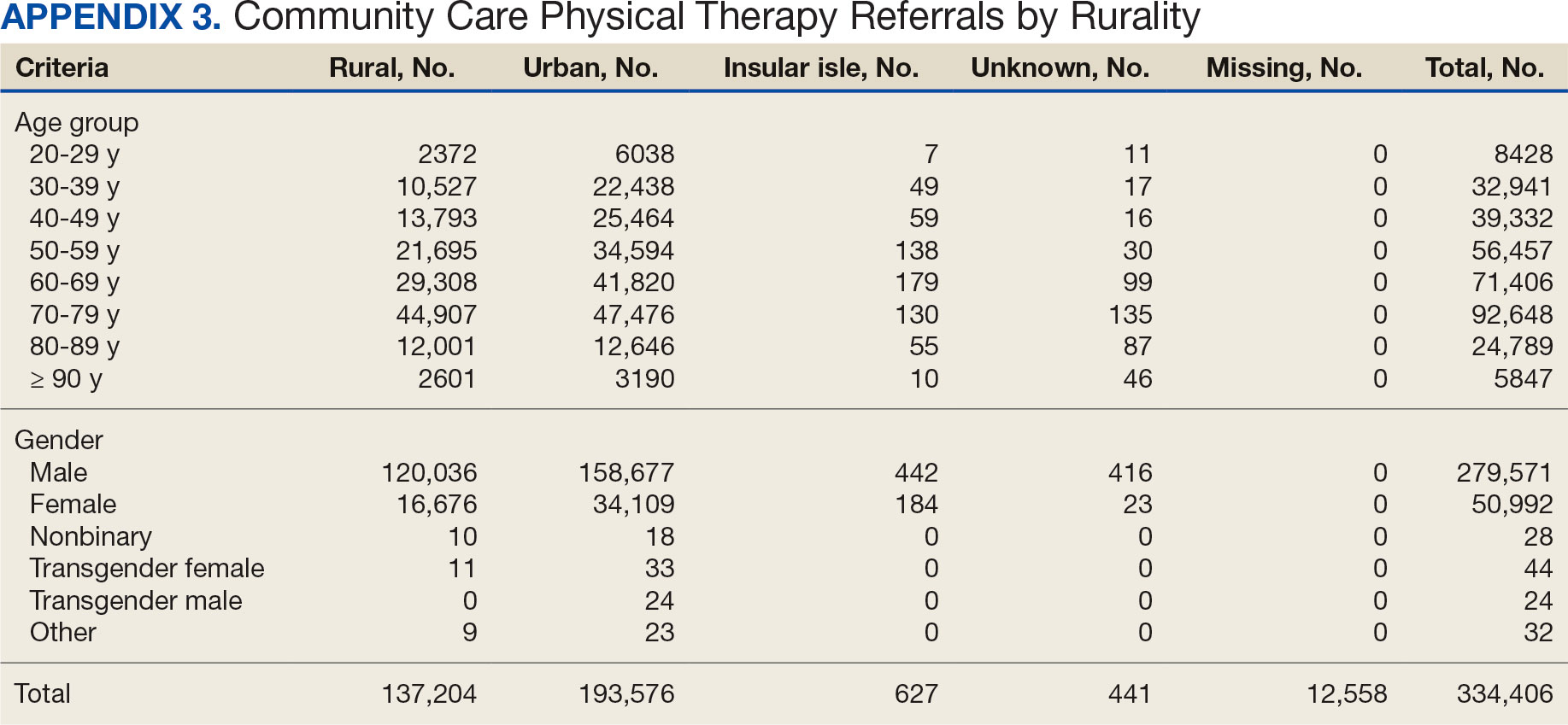

The mean (SD) age was 61.2 (15.8) years (range, 20-105). Most PT CC referrals were for veterans aged 70 to 79 years (26.9%), followed by 60 to 69 years (20.7%), and 50 to 59 years (16.4%) (Appendix 3). Trends were consistent across VISNs. There was less of a difference between rural and urban referral percentages as the population aged. Veterans aged < 49 years residing in more urban areas accounted for more referrals to CC compared to their rural counterparts. This difference was less apparent in the 70 to 79 years and 80 to 89 years age brackets.

Most PT CC referrals (81.2%) were male and 14.8% were female. About 3.6% of referral data were missing sex information, and there was a smaller difference between male veterans living in rural communities and male veterans living in urban communities compared with female veterans. A total of 42.9% of male veterans resided in rural areas compared to 56.8% in urban areas; 32.7% of female veterans resided in rural areas compared to 66.9% in urban areas (Appendix 3).

Other Criteria

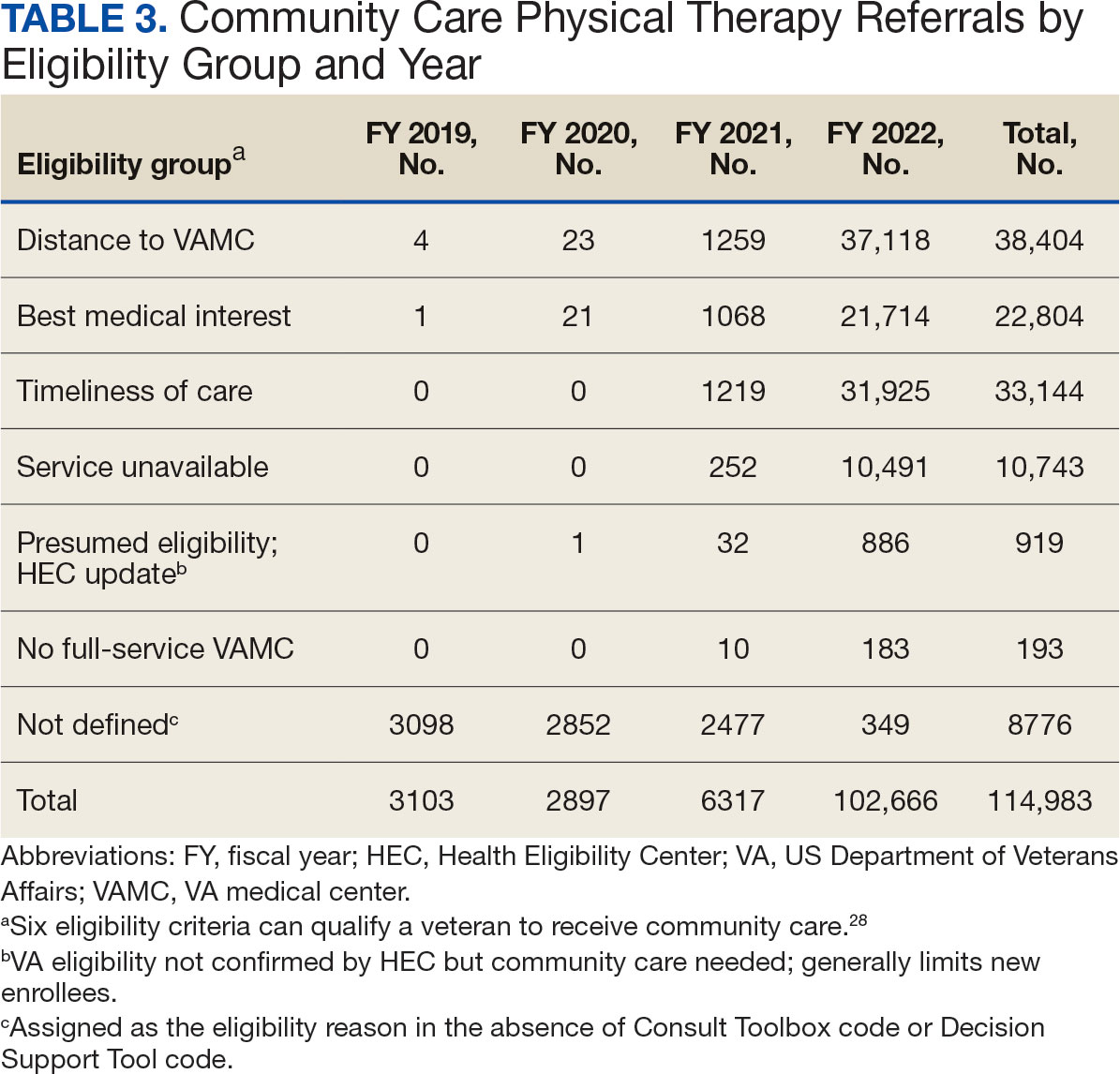

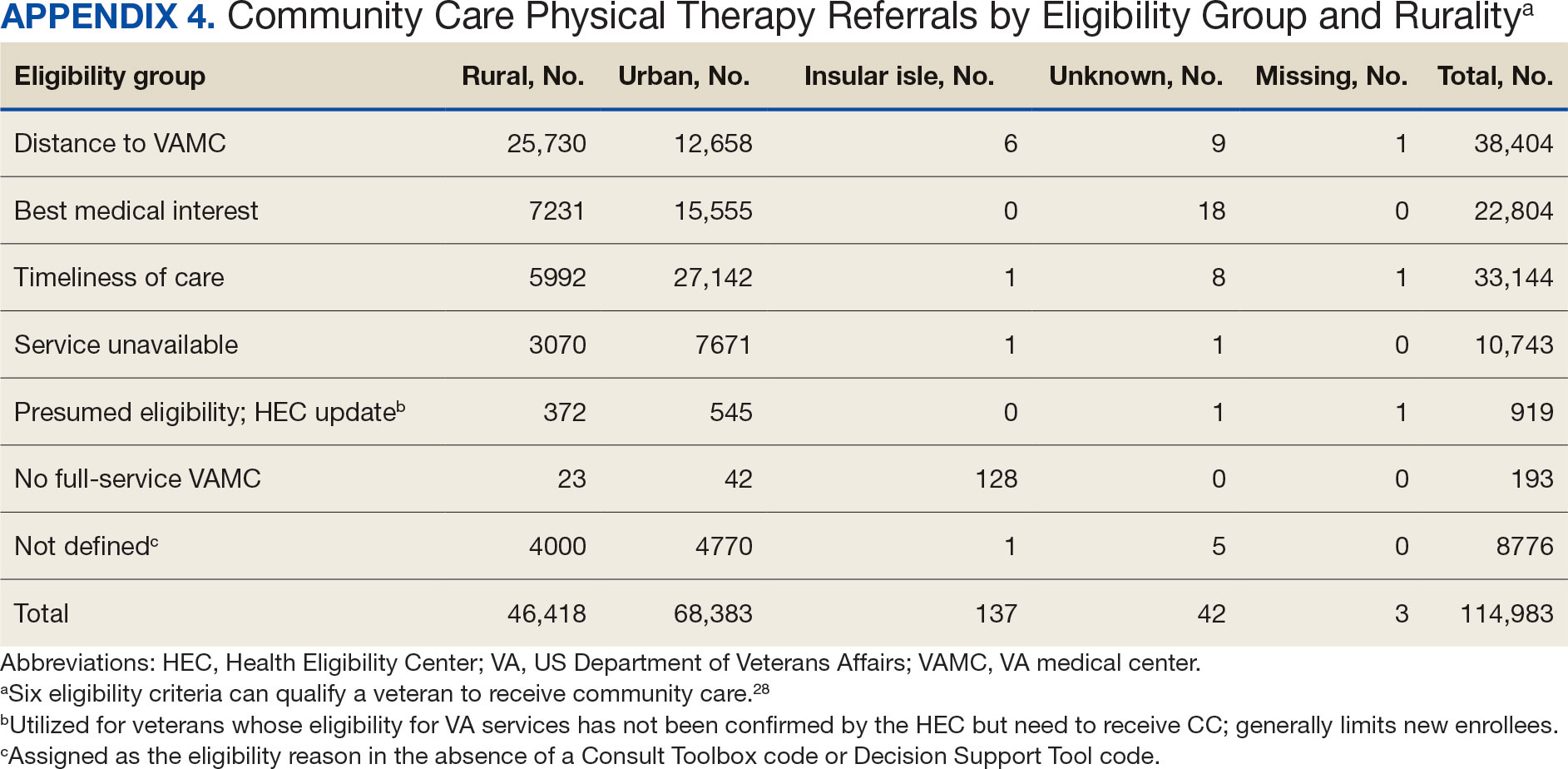

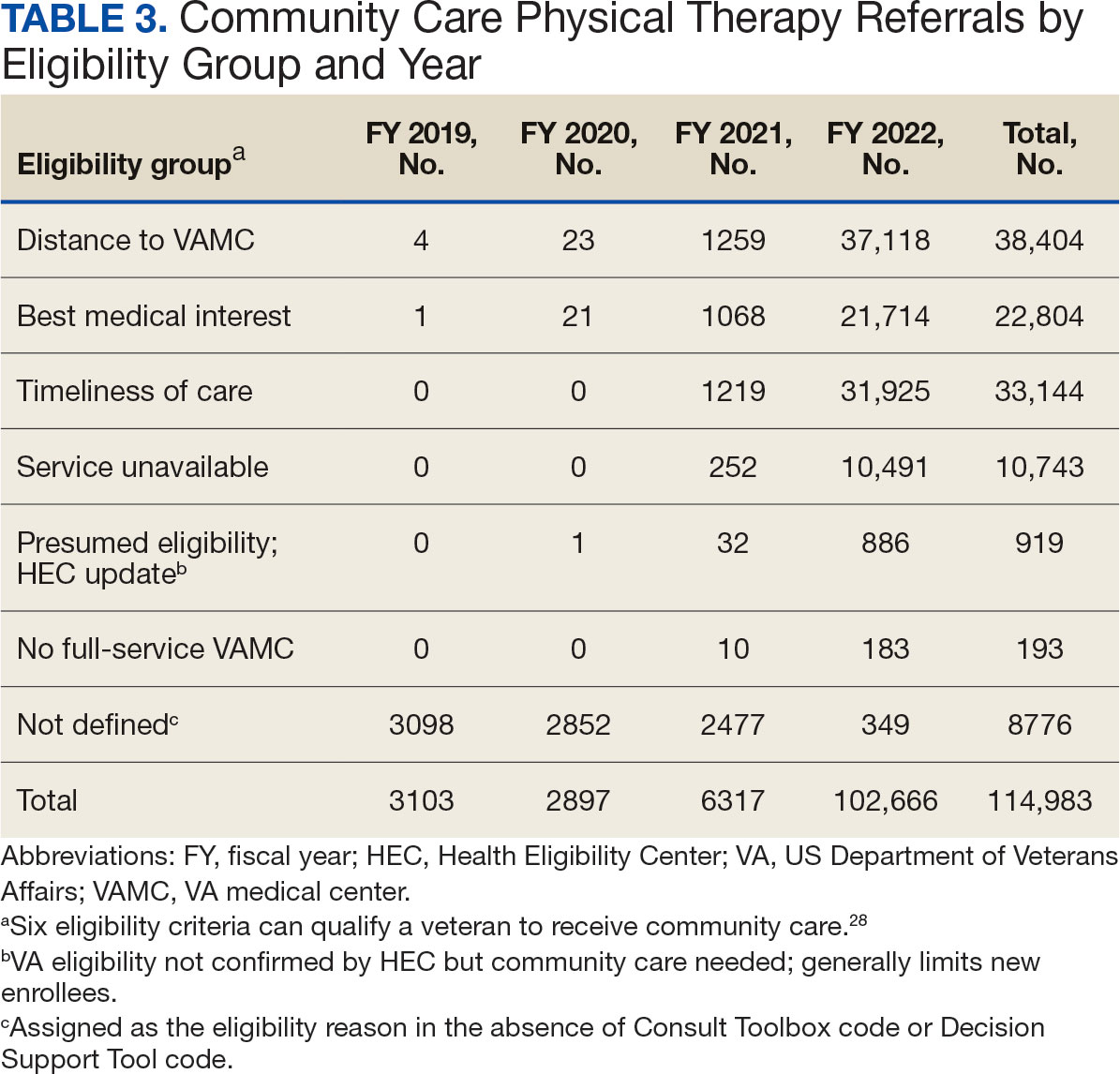

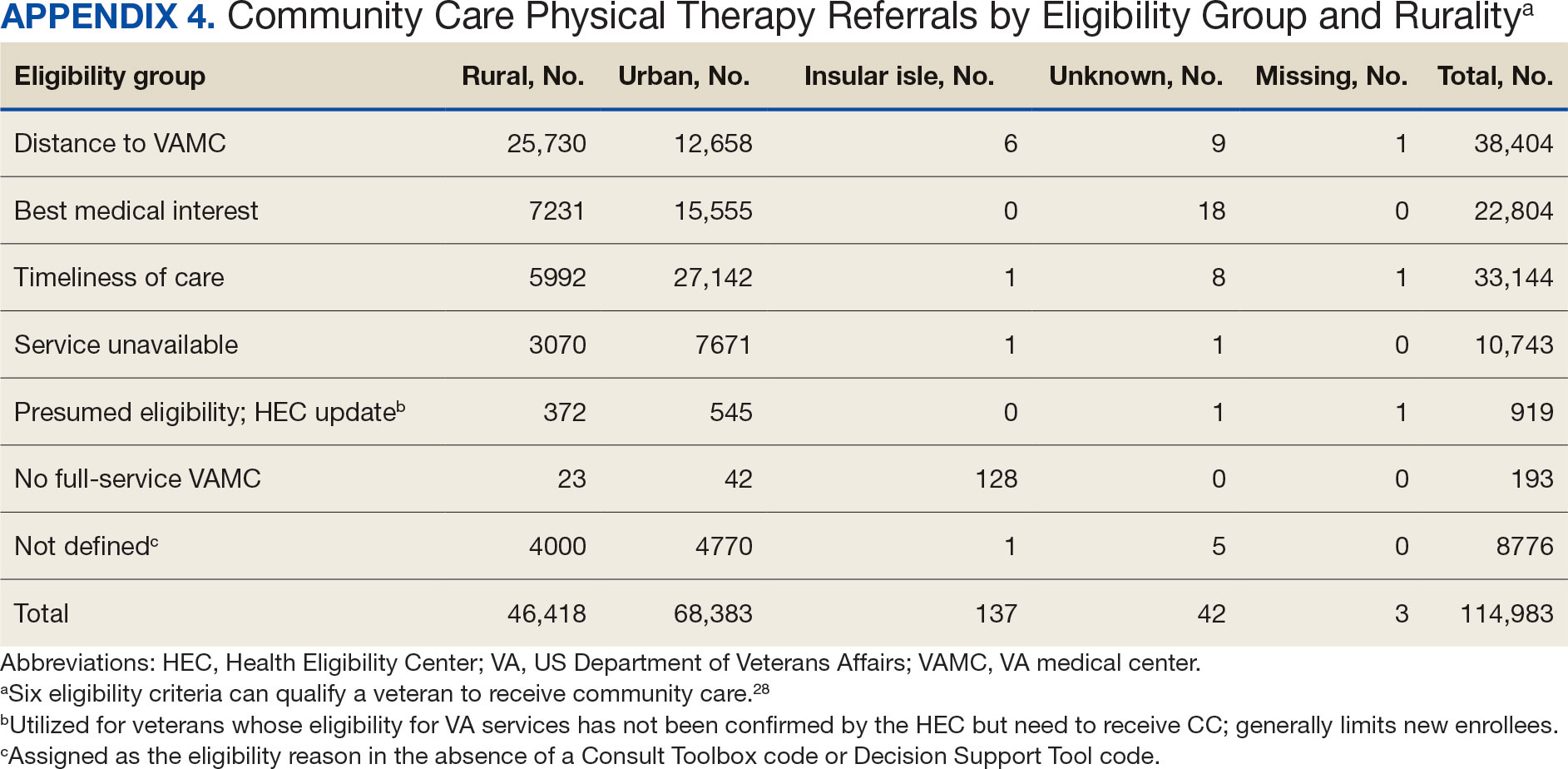

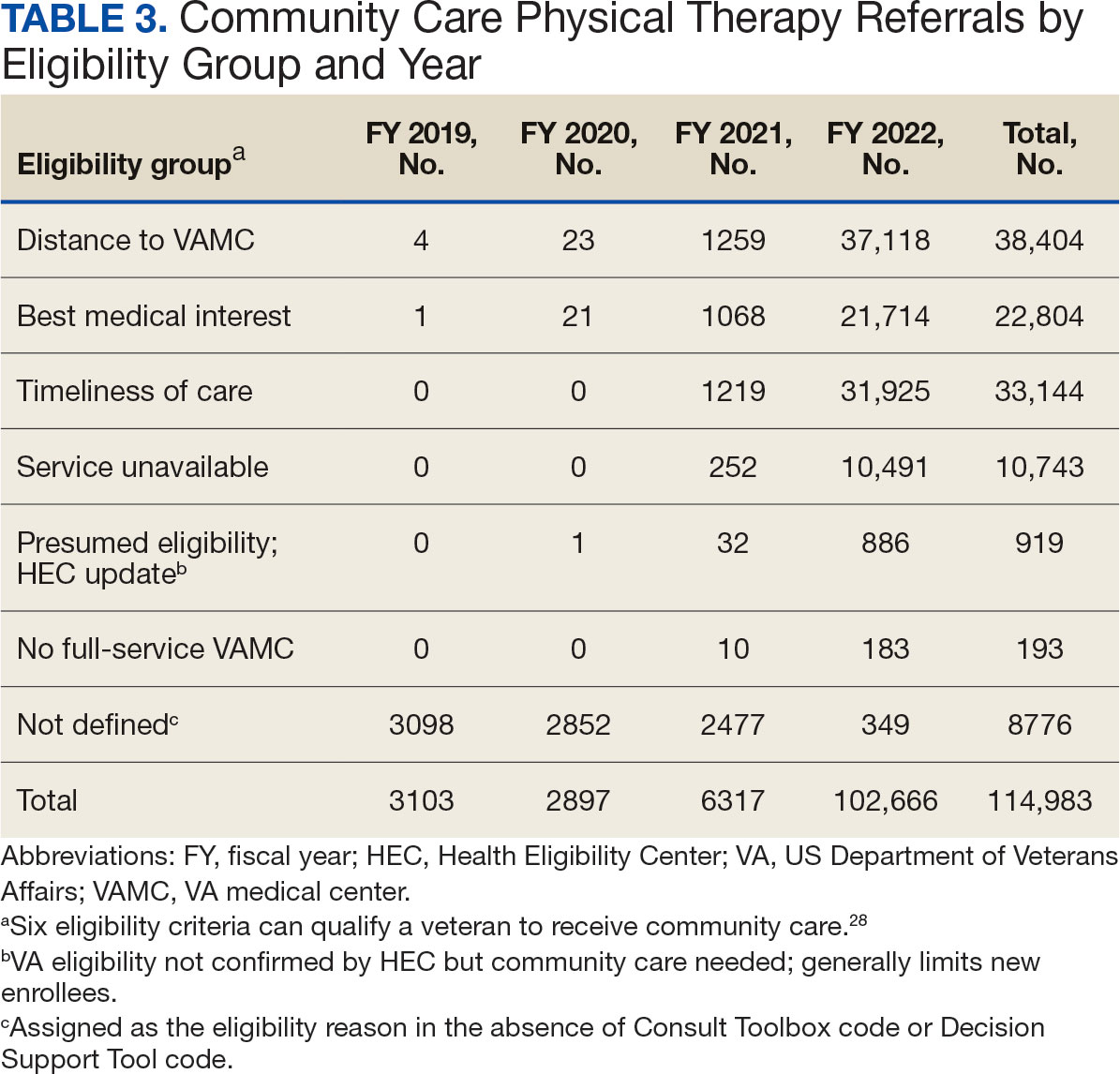

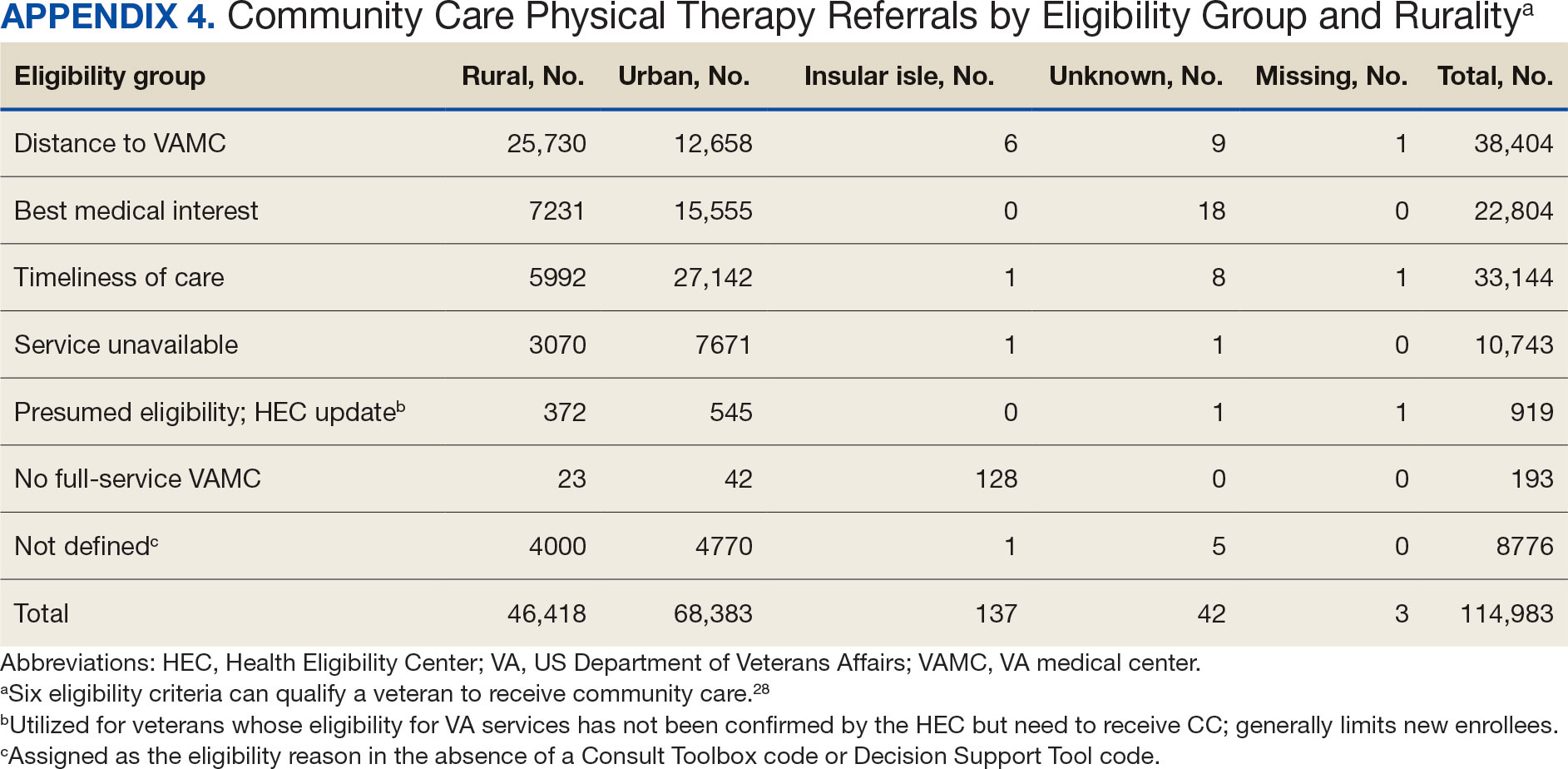

Of the 334,406 referrals, 114,983 (34.4%) had eligibility data, mostly from FY 2021 and FY 2022 (Table 3). Available eligibility data were likely affected by the MISSION Act and new regulations for reporting CC eligibility. Distance (33.4%) was the most common eligibility criteria, followed by timeliness of care (28.8%), and best medical interest (19.8%); 40.4% were rural and 59.5% were urban. Distance (55.4%) was most common for rural veterans, while timeliness of care (39.7%) was most common for urban veterans. For both groups, the second most common eligibility reason was best medical interest (Appendix 4).

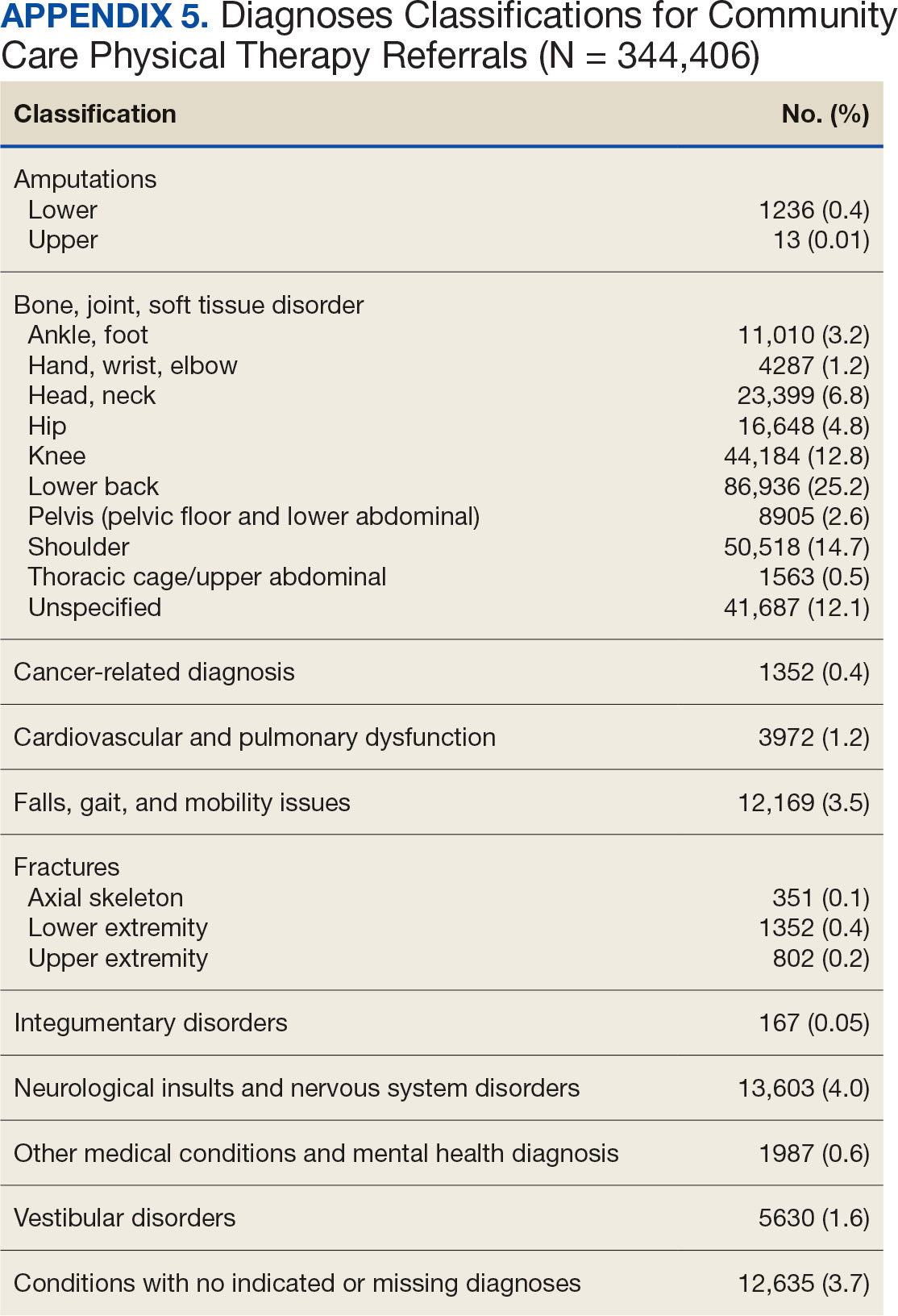

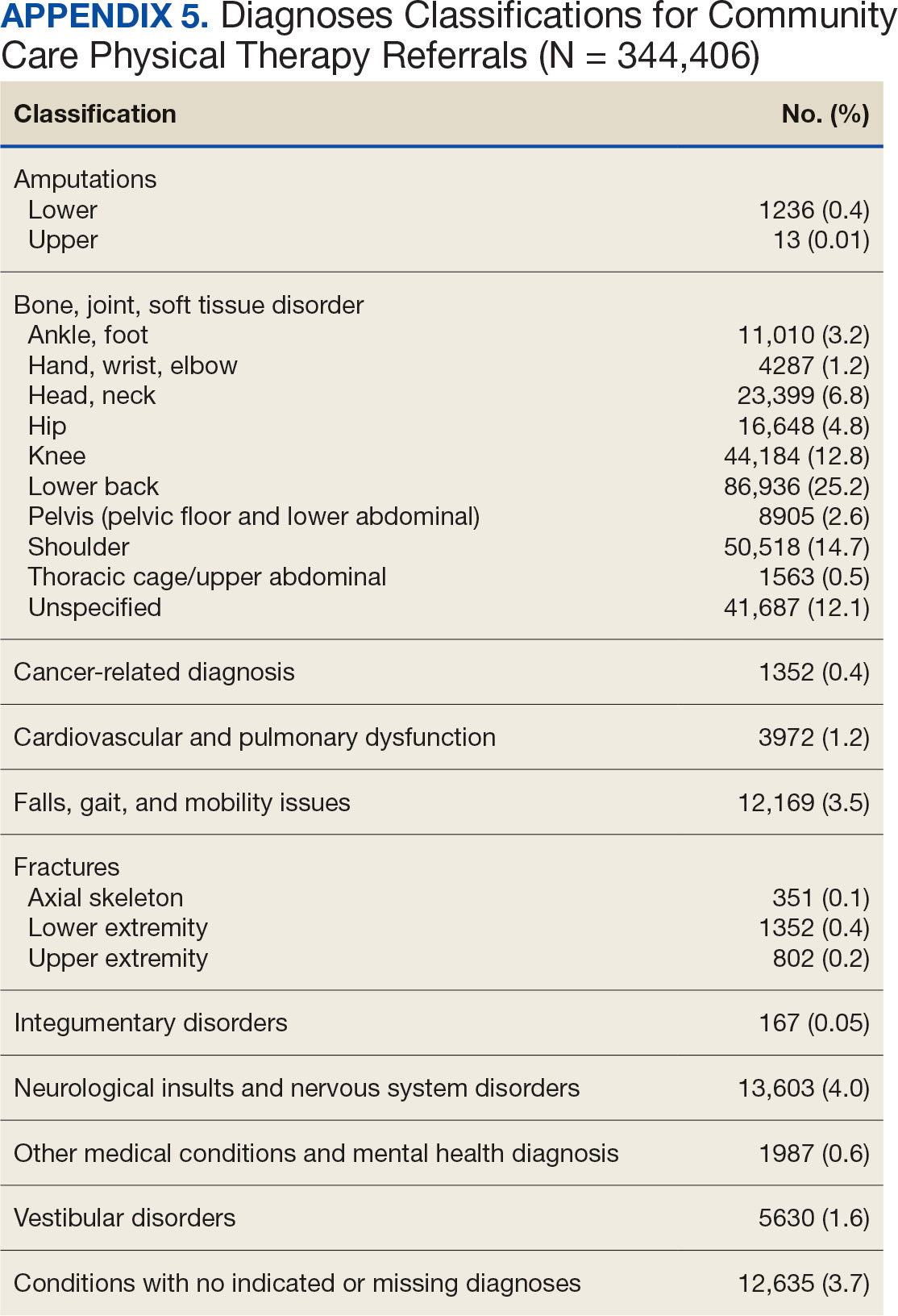

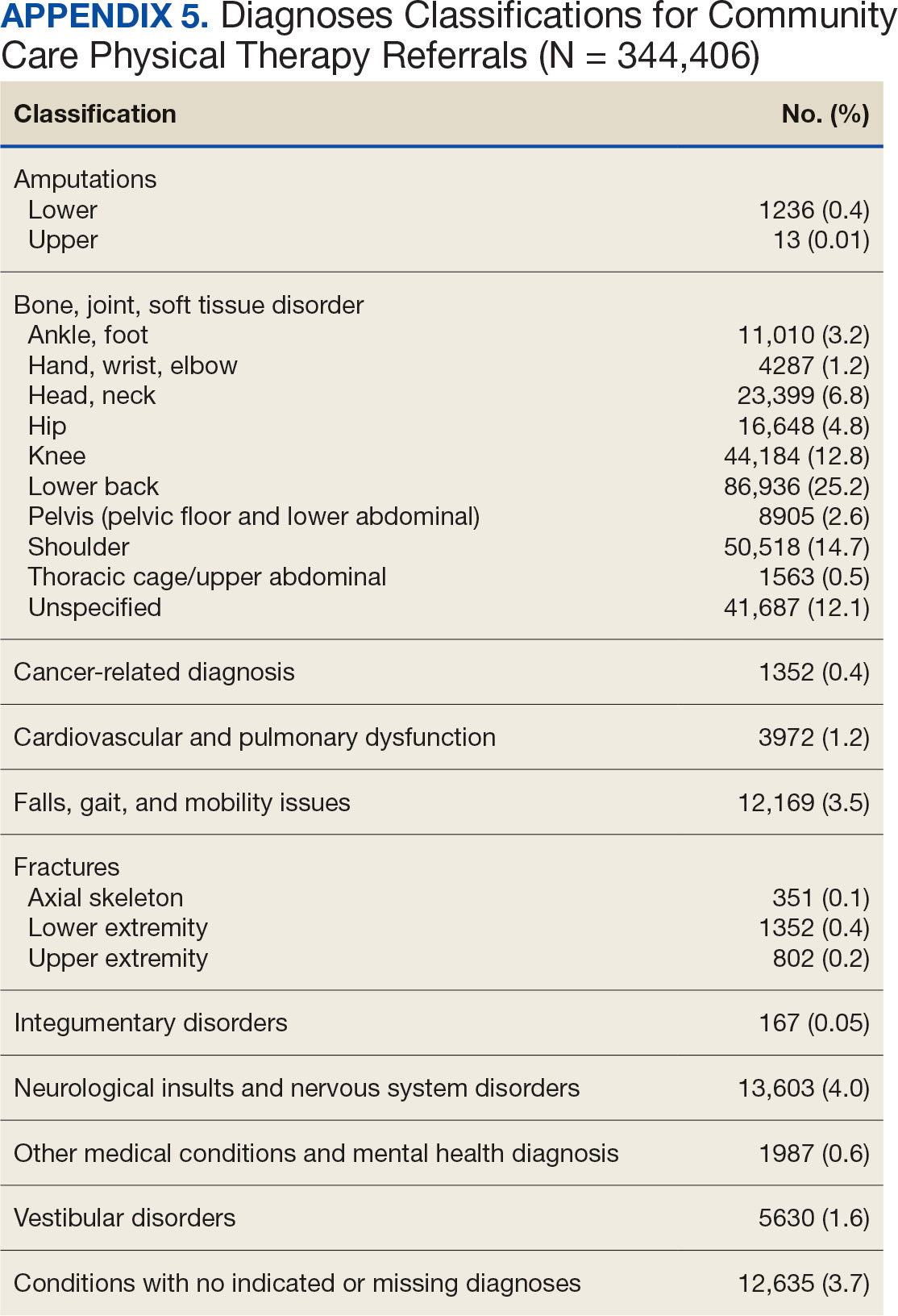

Bone, joint, or soft tissue disorders were common diagnoses, with 25.2% located in the lower back, 14.7% in the shoulder, and 12.8% in the knee (Appendix 5). Amputations of the upper and lower limbs, fractures, cancer-related diagnoses, integumentary system disorders, thoracic and abdominal injuries and disorders, and other medical and mental health conditions each accounted for < 1% of the total diagnoses.

Costs

At time of analysis, the CC Dashboard had cost data available for 200,204 CC PT referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022. The difference in referral numbers for the 2 datasets is likely attributed to several factors: CC cost data is exclusively from the HSRM, whereas Palantir includes other data sources; how VA cleans data pulled into Palantir; how the CC Dashboard algorithm populates data; and variances based on timing of reporting and/or if referrals are eventually canceled.

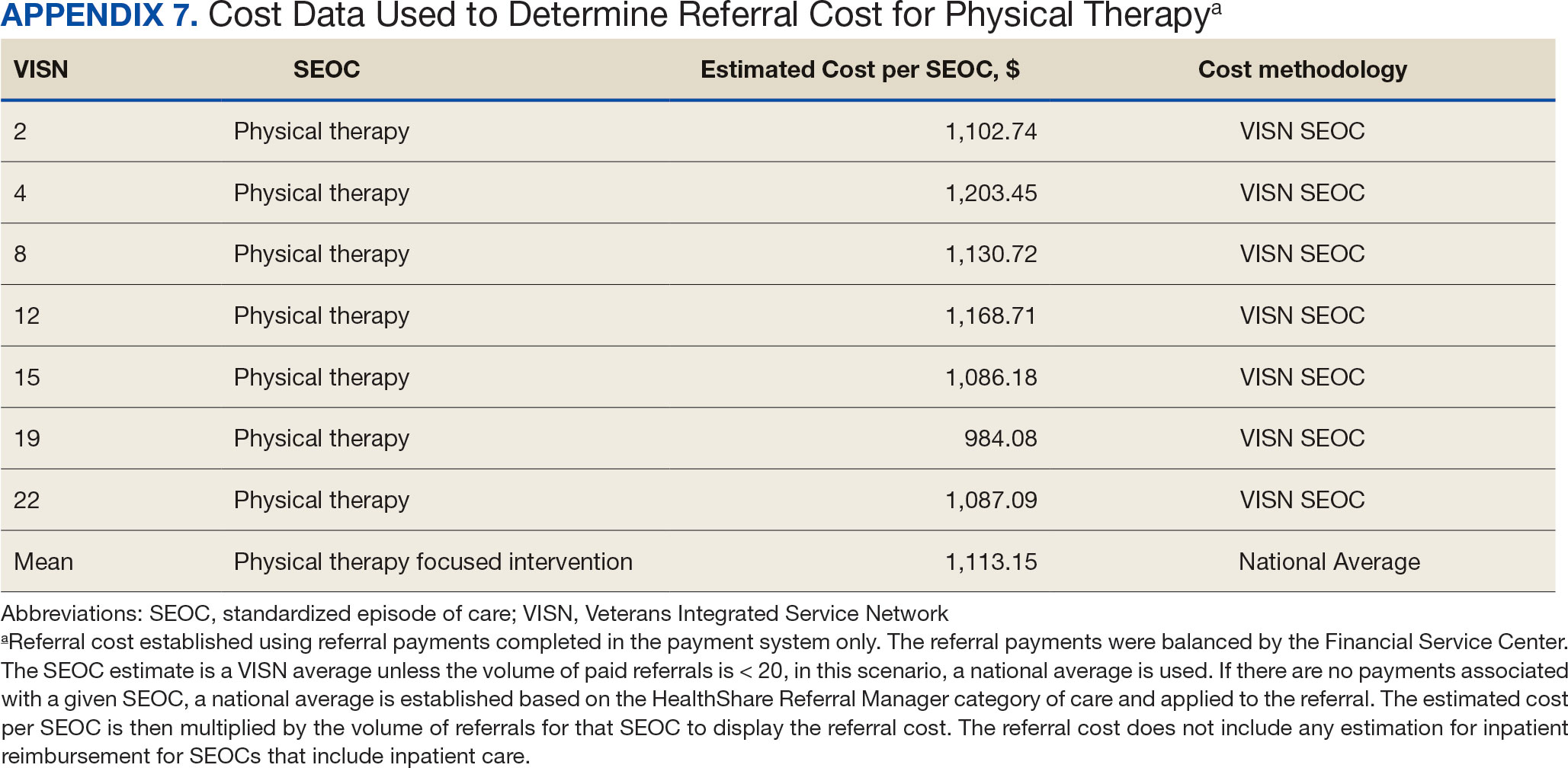

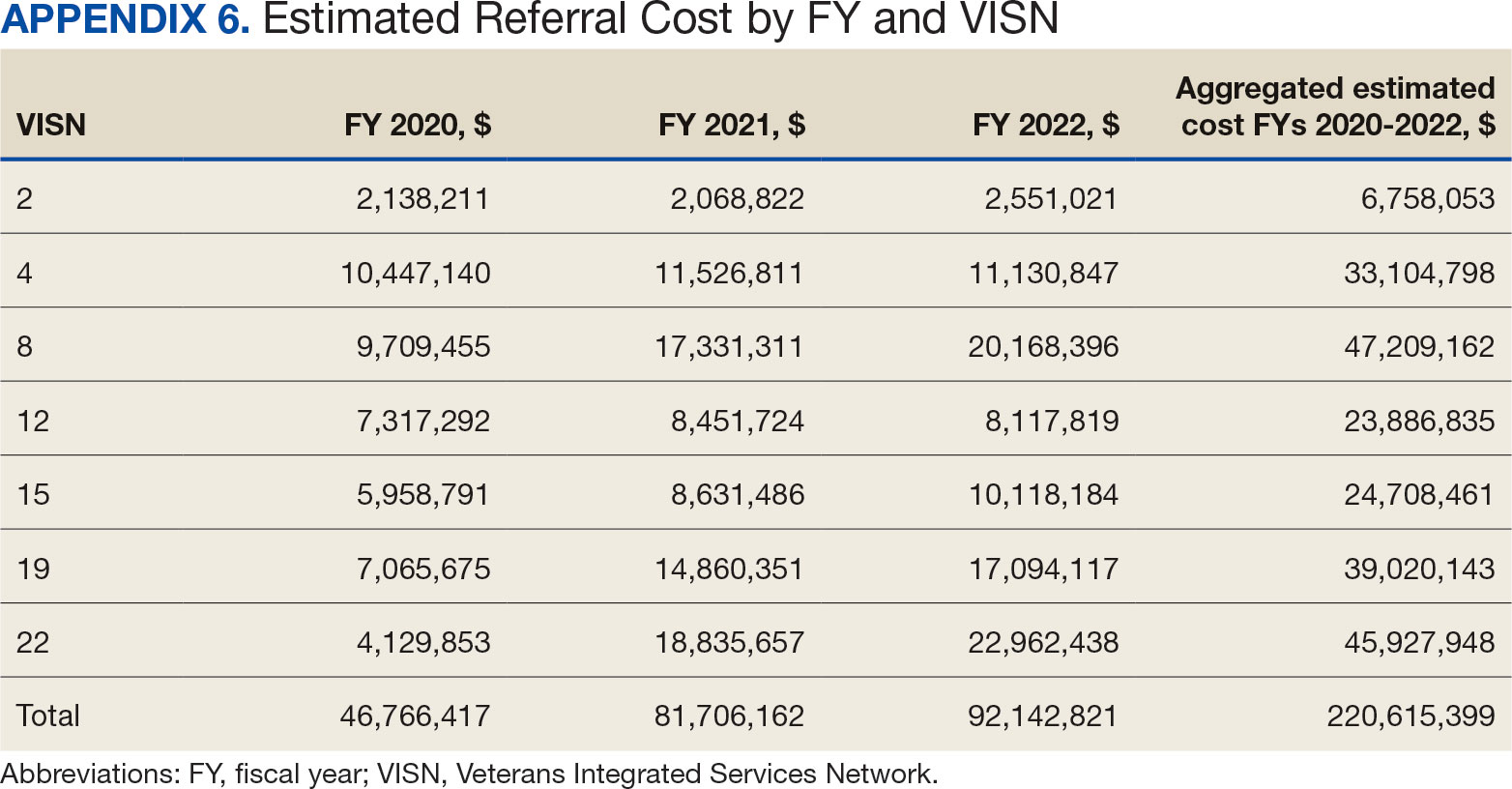

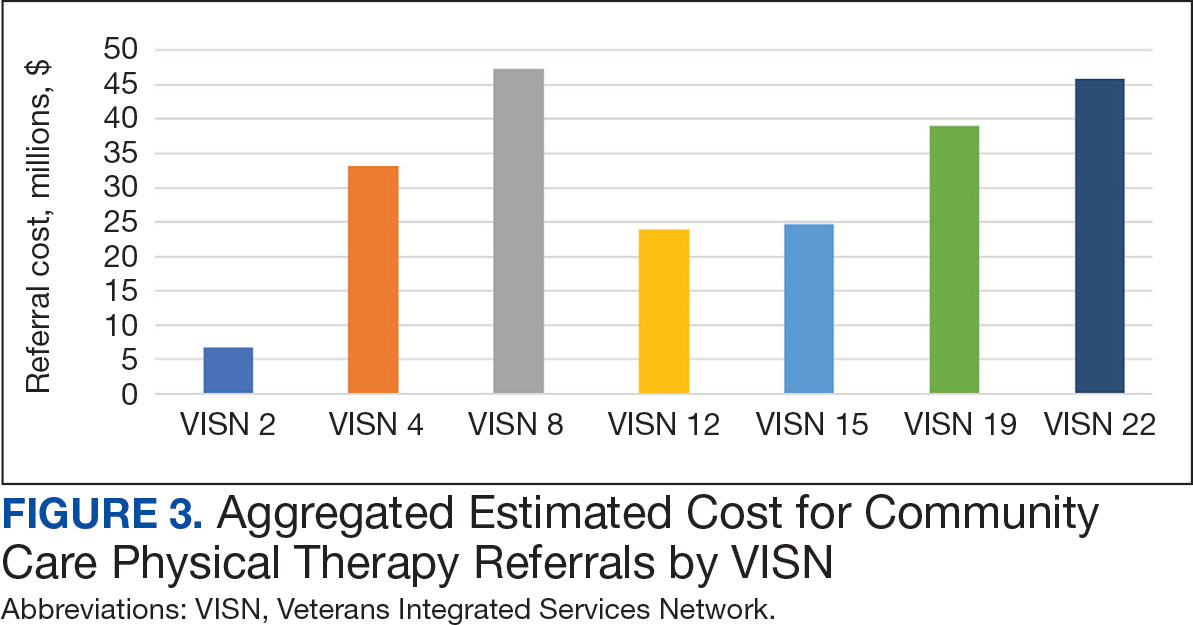

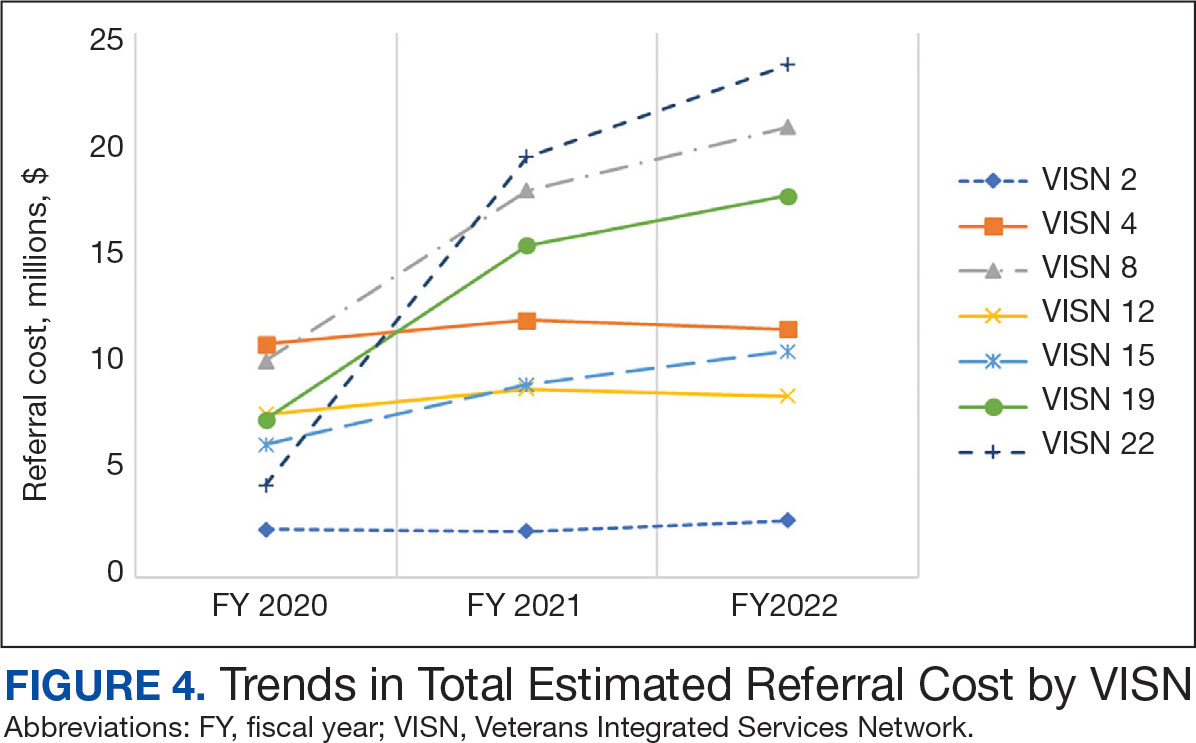

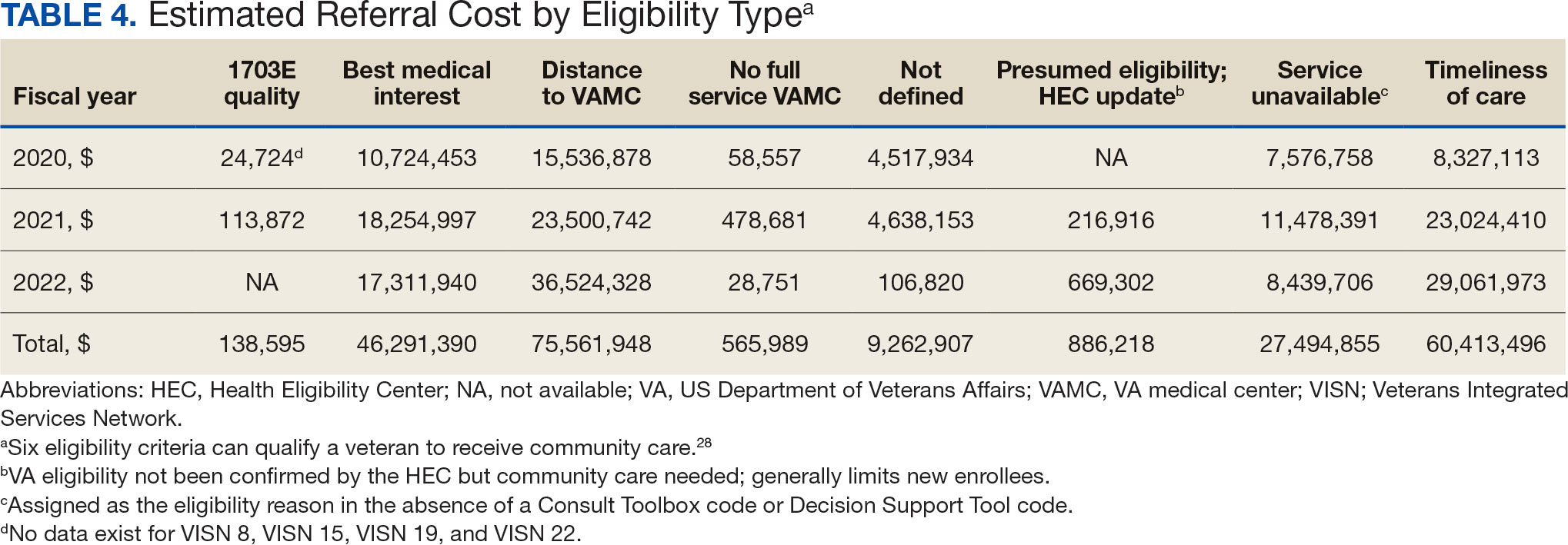

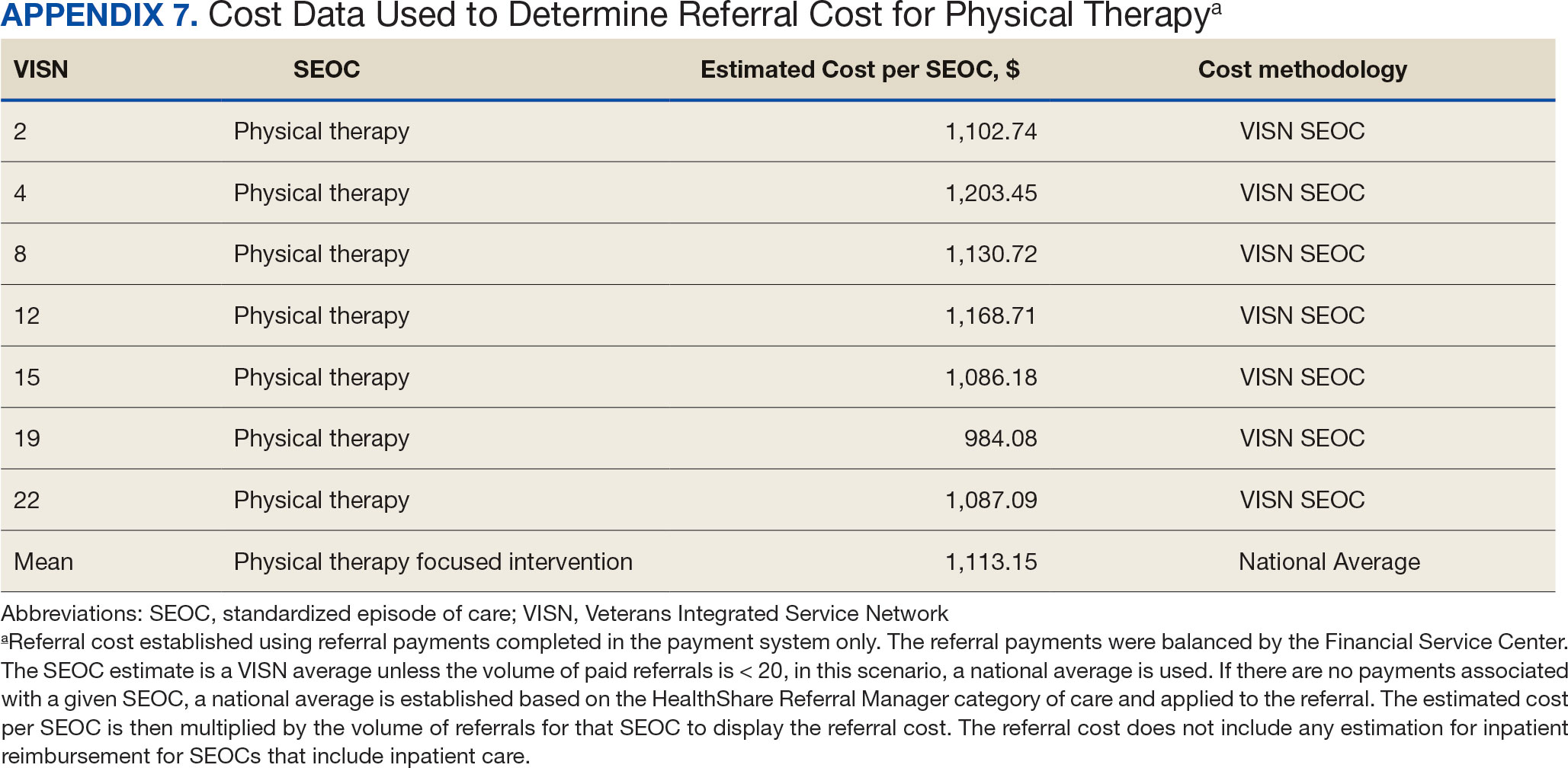

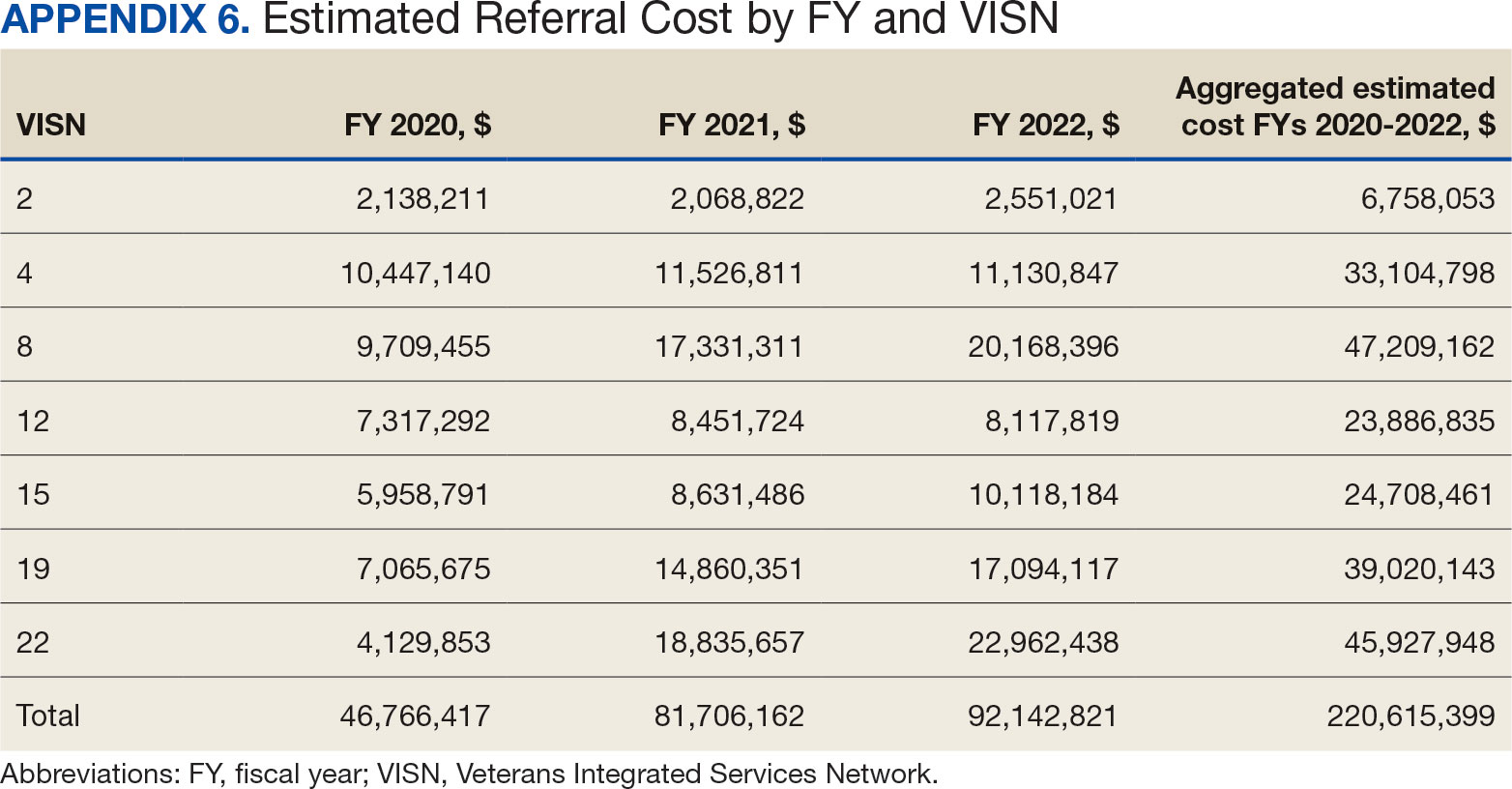

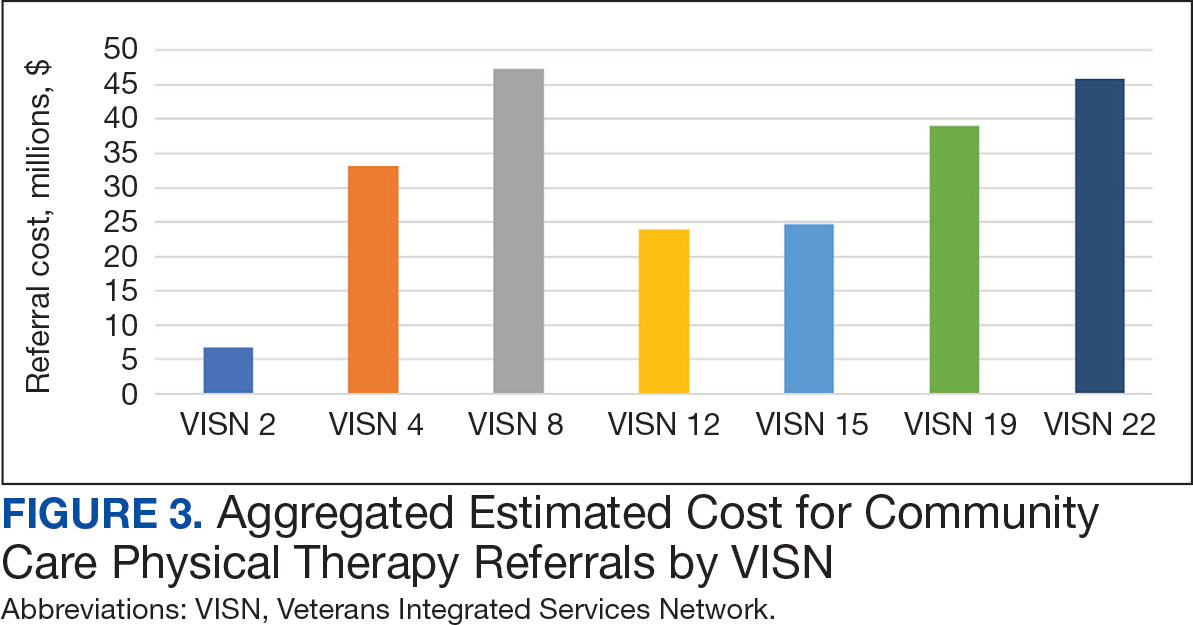

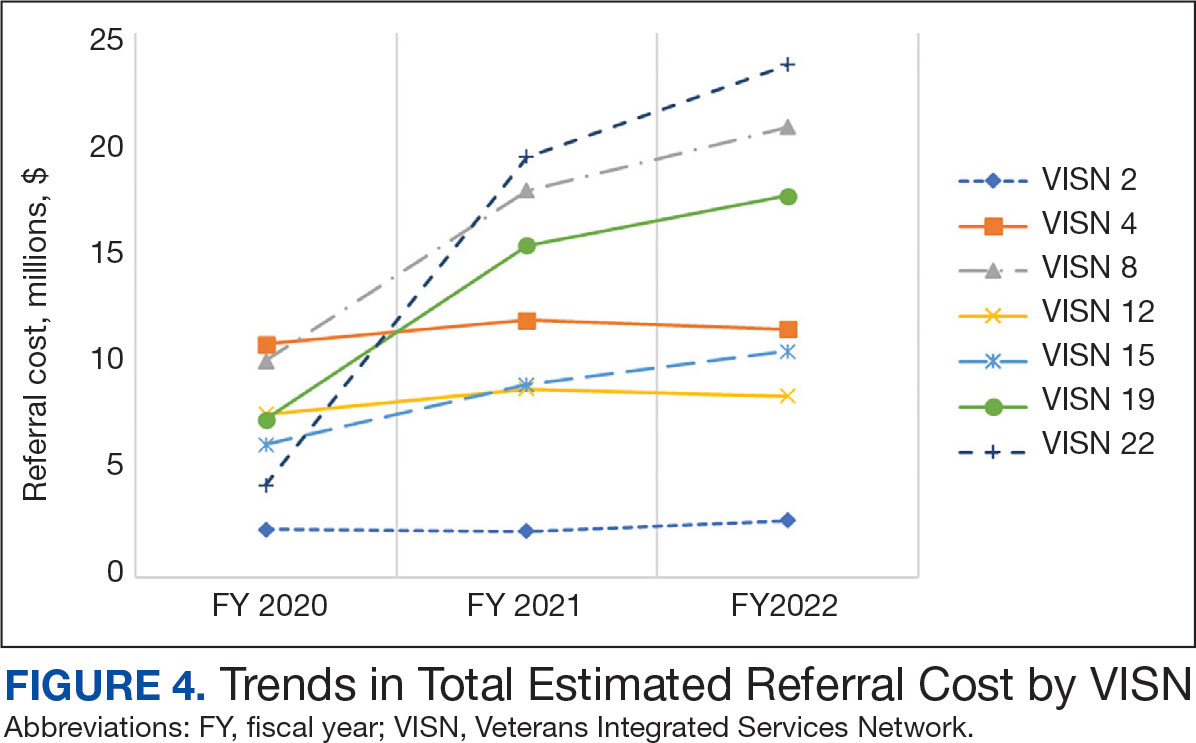

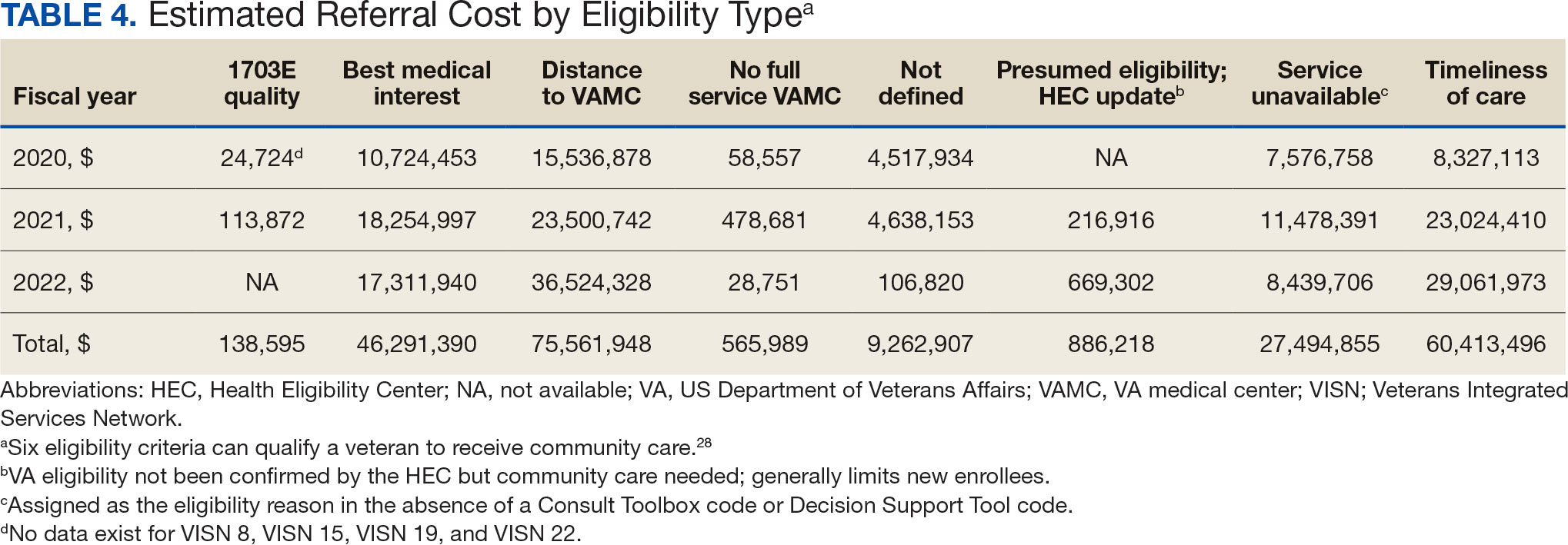

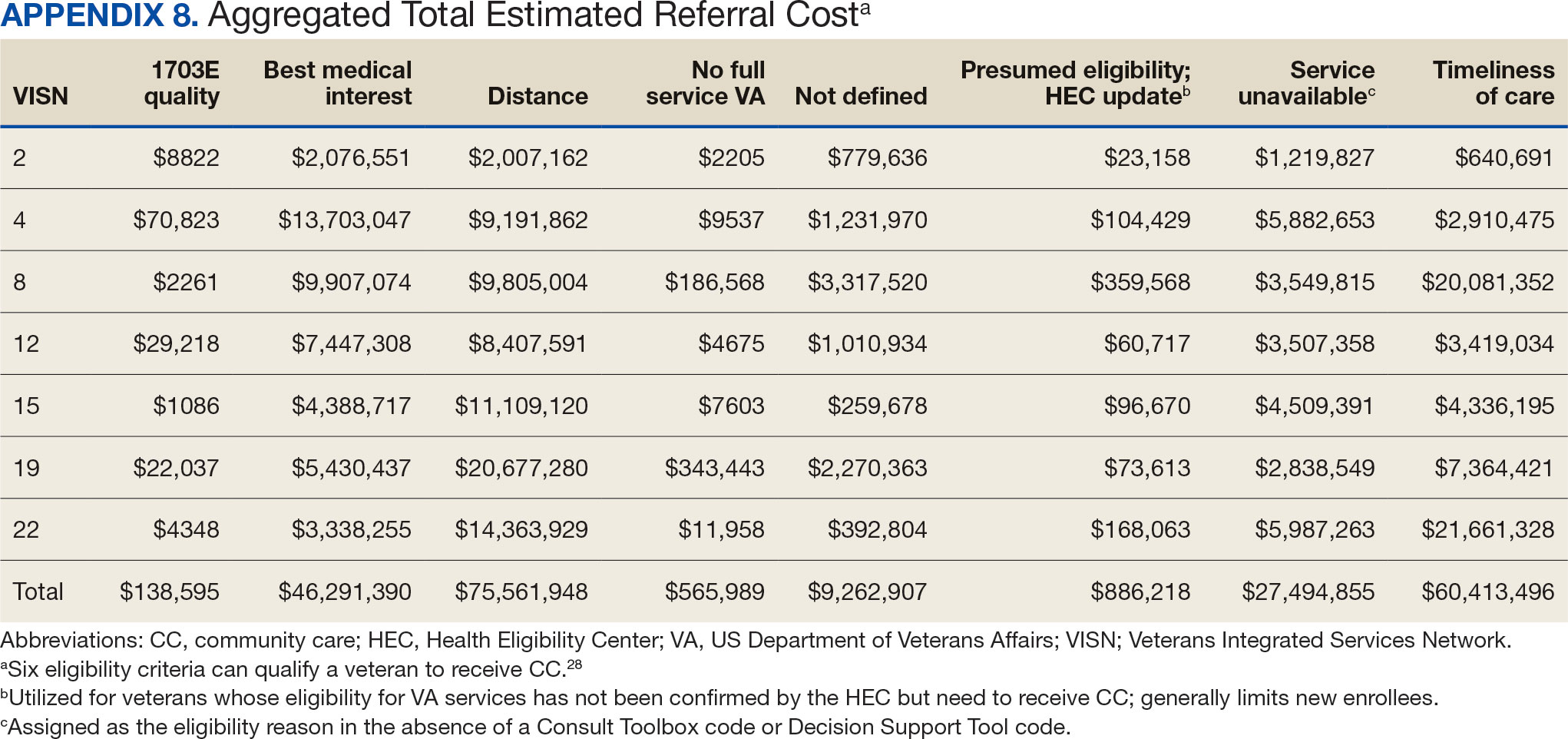

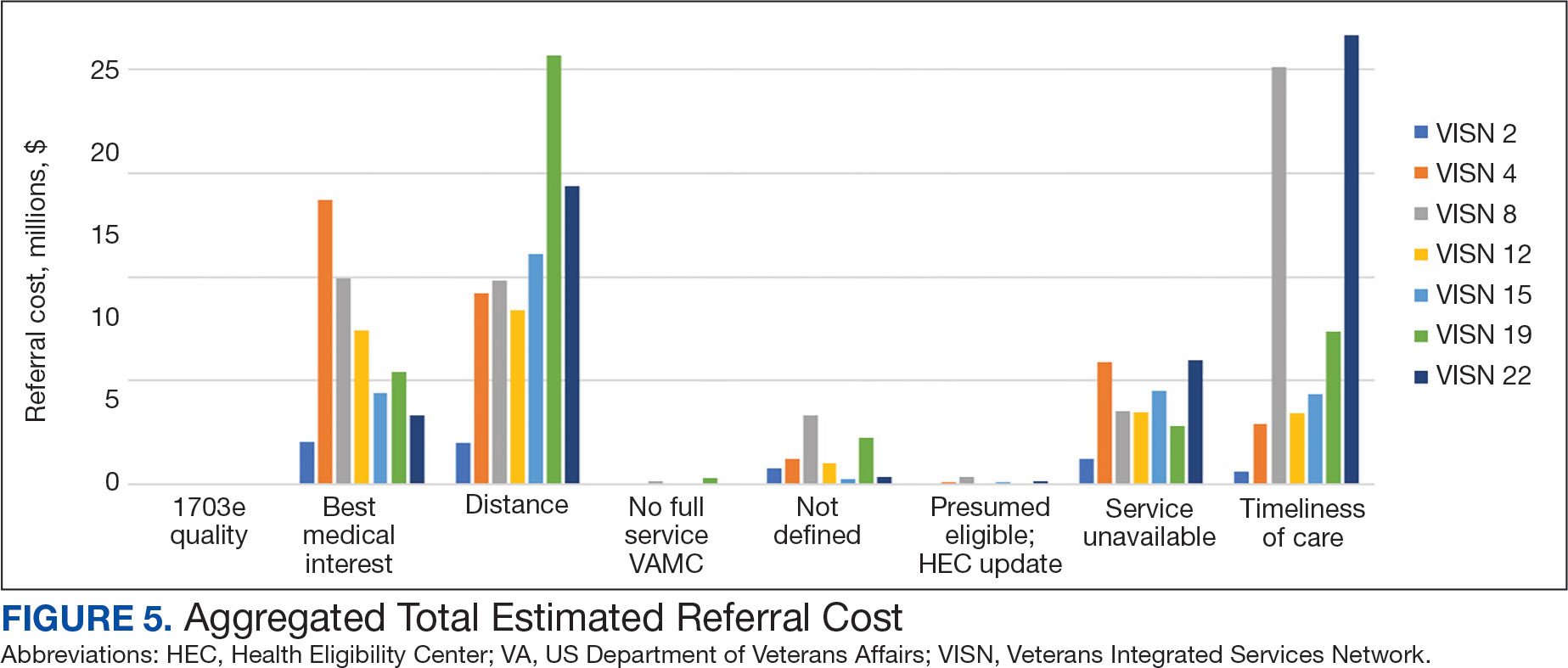

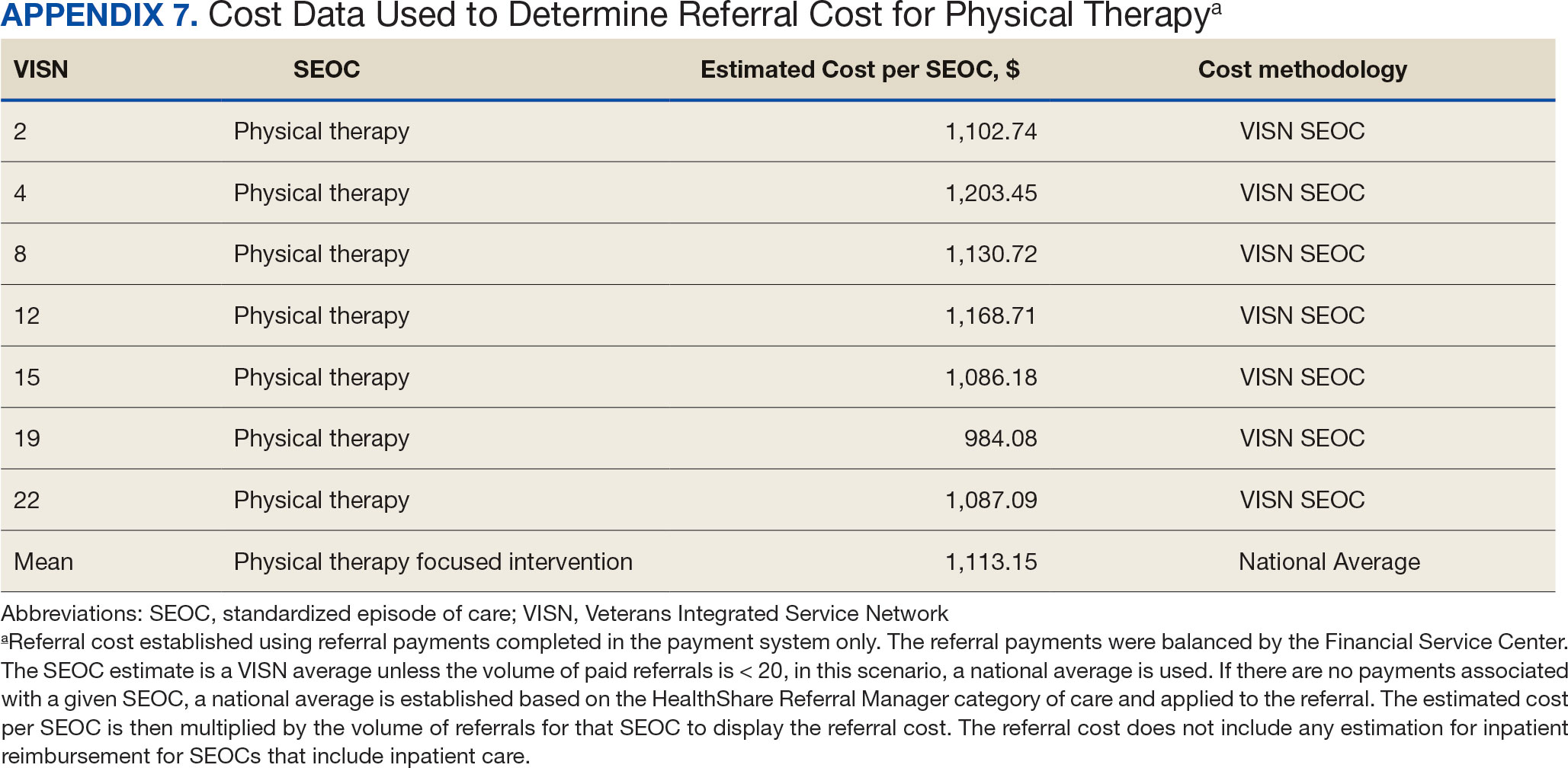

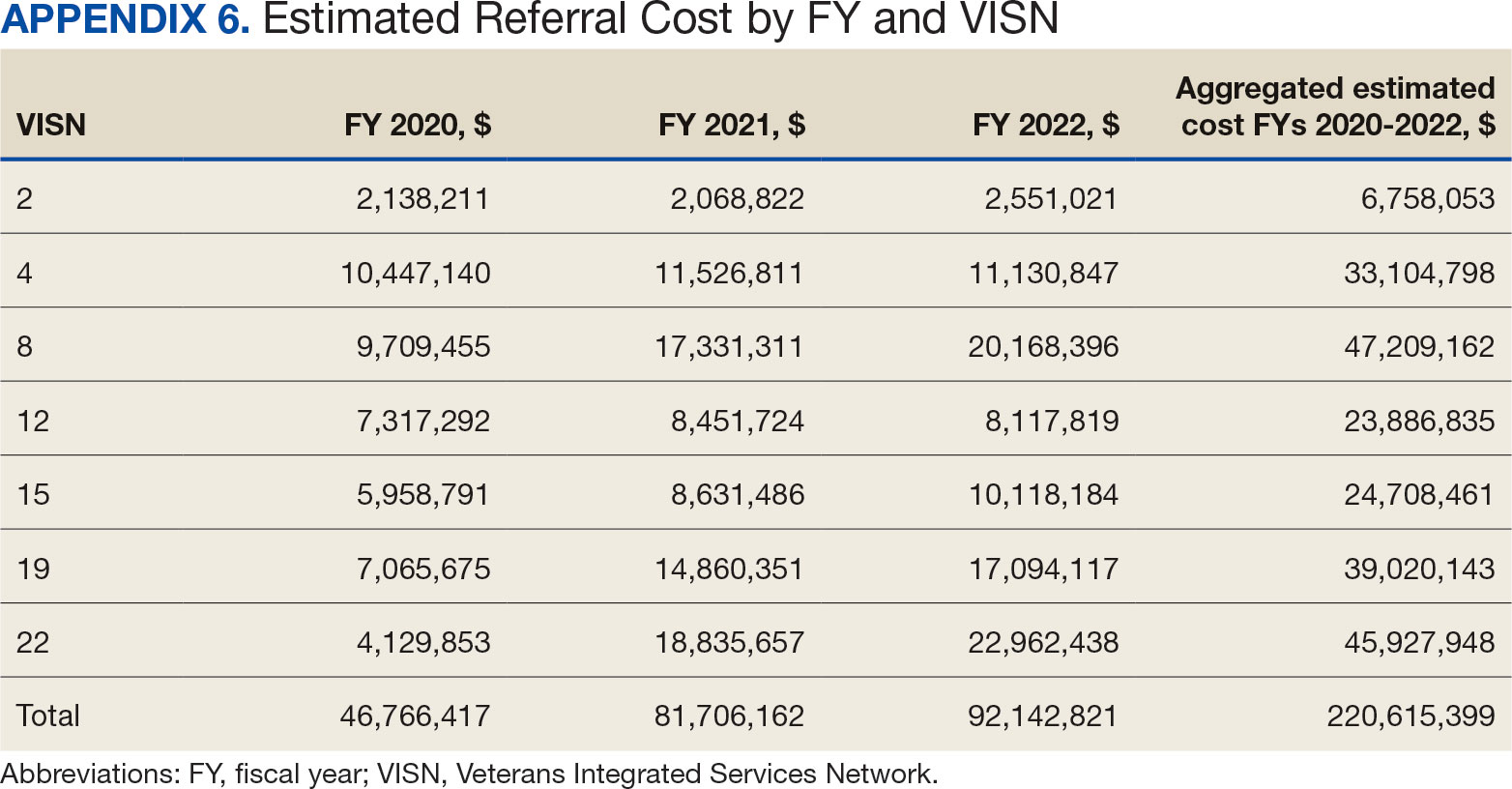

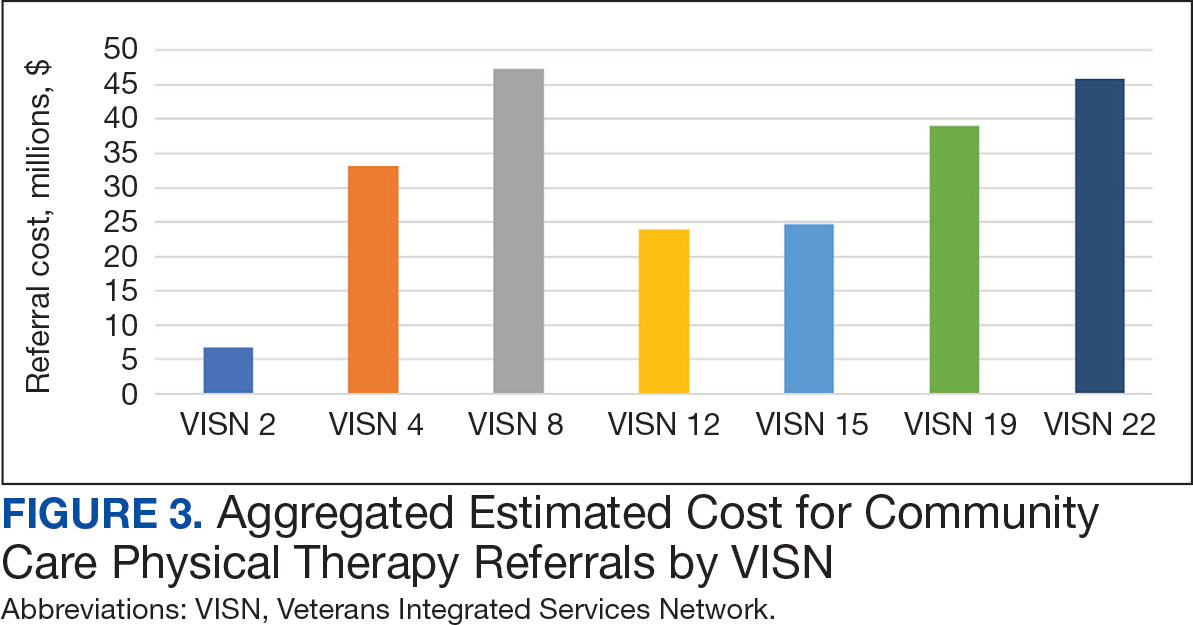

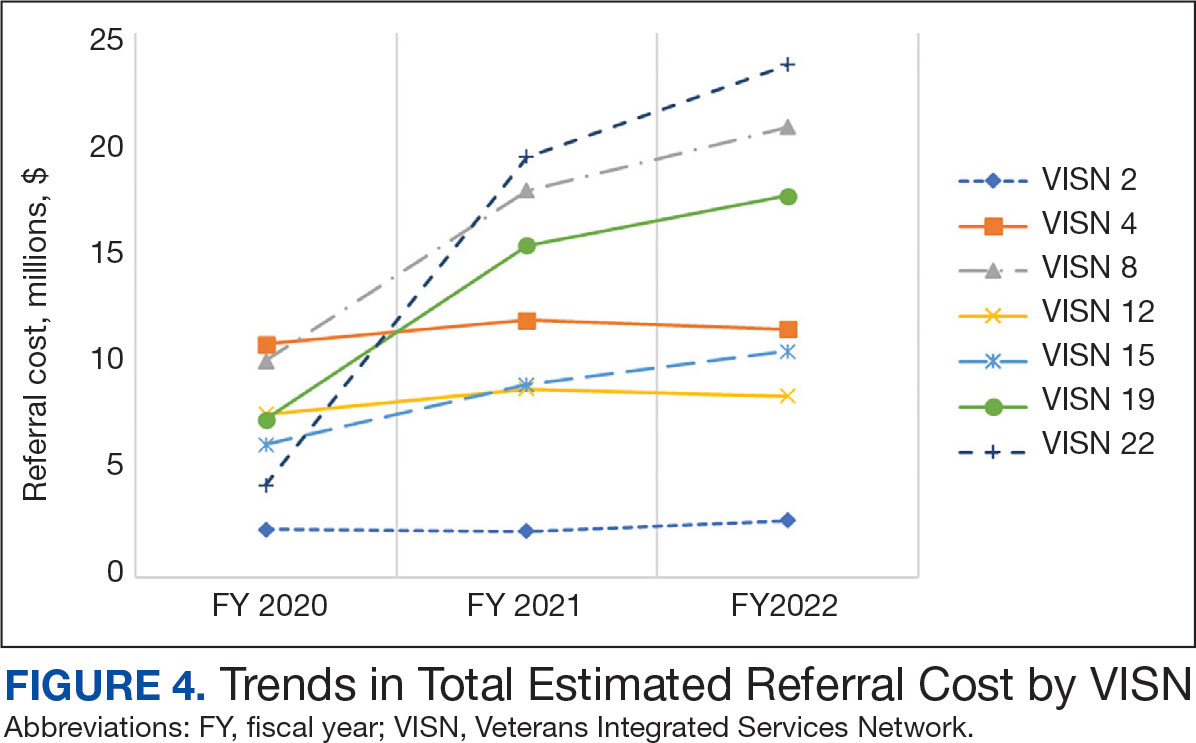

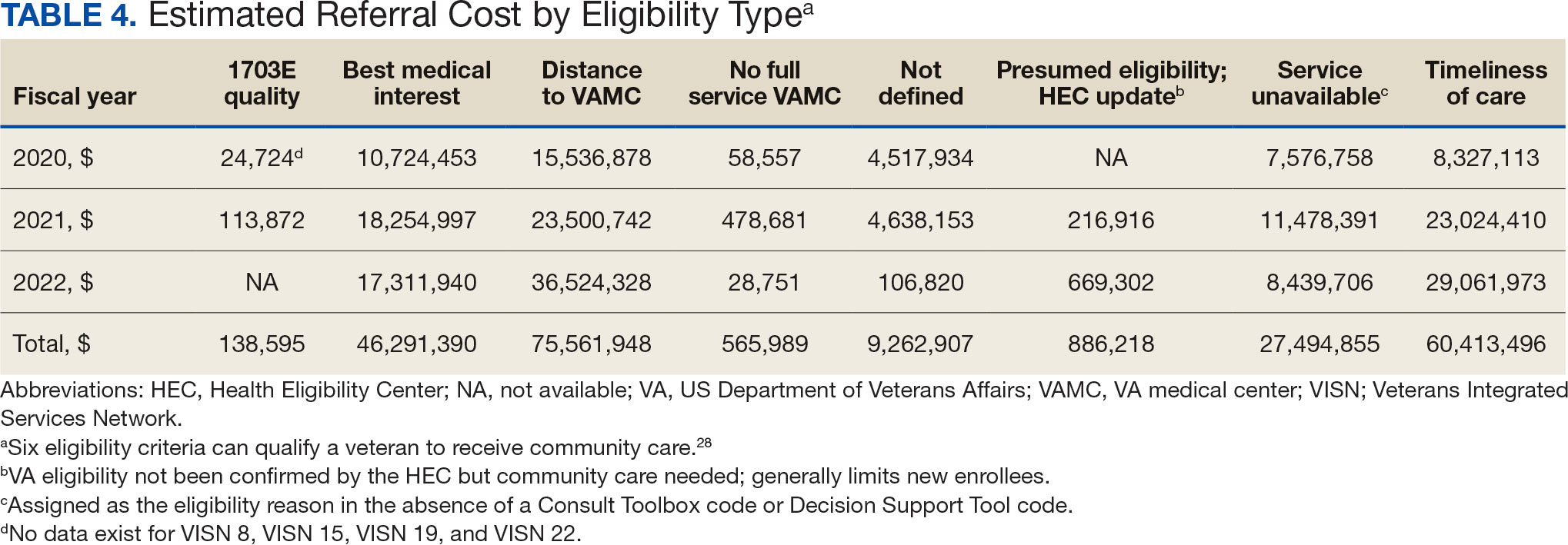

The total cost of PT CC referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022 in selected VISNs was about $220,615,399 (Appendix 6). Appendix 7 details the methodology for determining the average standardized episode- of-care cost by VISN and how referral costs are calculated. Data show a continuous increase in total estimated cost from $46.8 million in FY 2020 to $92.1 million in FY 2022. From FY 2020 to FY 2022, aggregate costs ranged from $6,758,053 in VISN 2 to $47,209,162 in VISN 8 (Figure 3). The total referral cost for PT was highest at VISN 4 in FY 2020 ($10,447,140) and highest at VISN 22 in FY 2021 ($18,835,657) and FY 2022 ($22,962,438) (Figure 4). For referral costs from FY 2020 to FY 2022, distance accounted for $75,561,948 (34.3%), timeliness of care accounted for $60,413,496 (27.3%), and best medical interest accounted for $46,291,390 (21.0%) (Table 4).

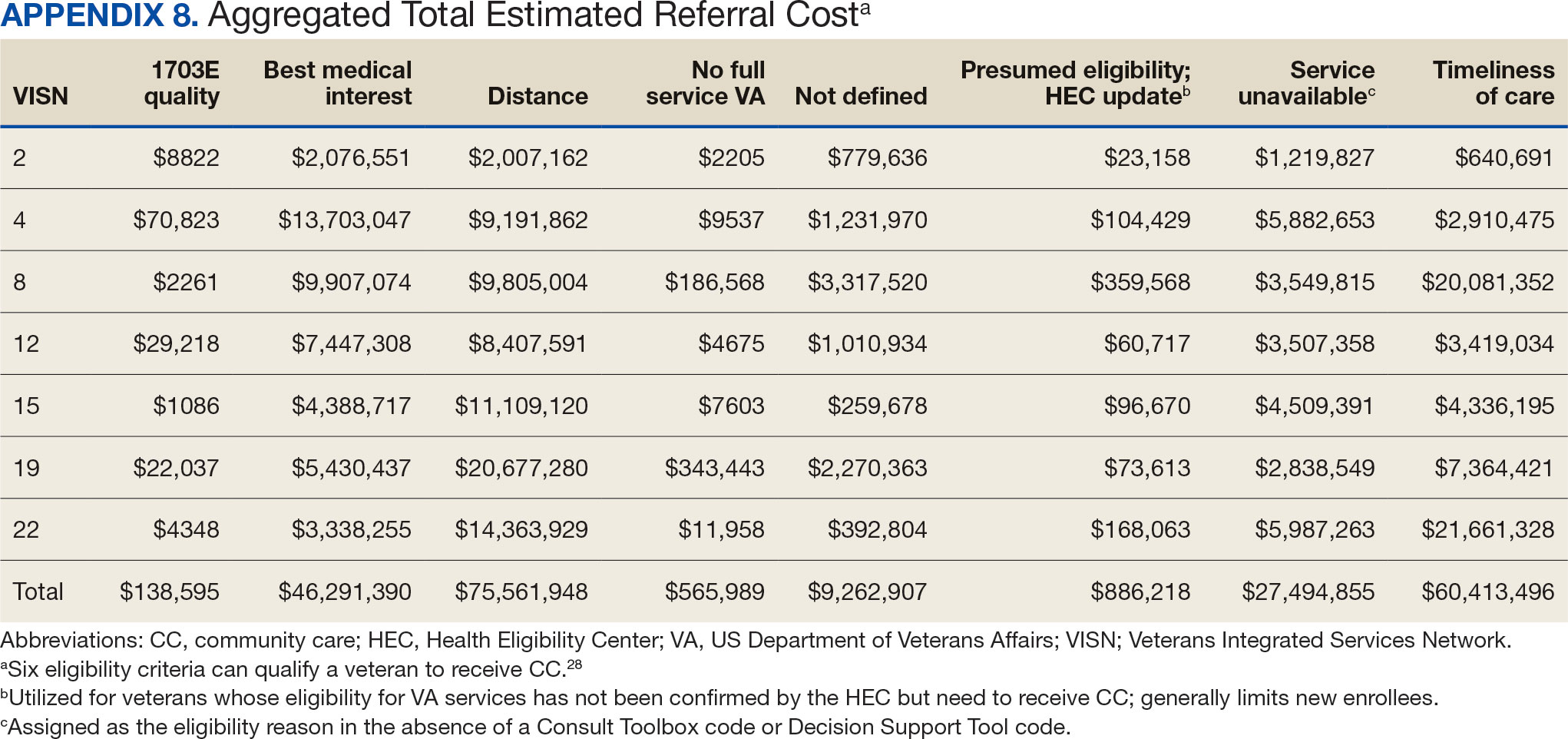

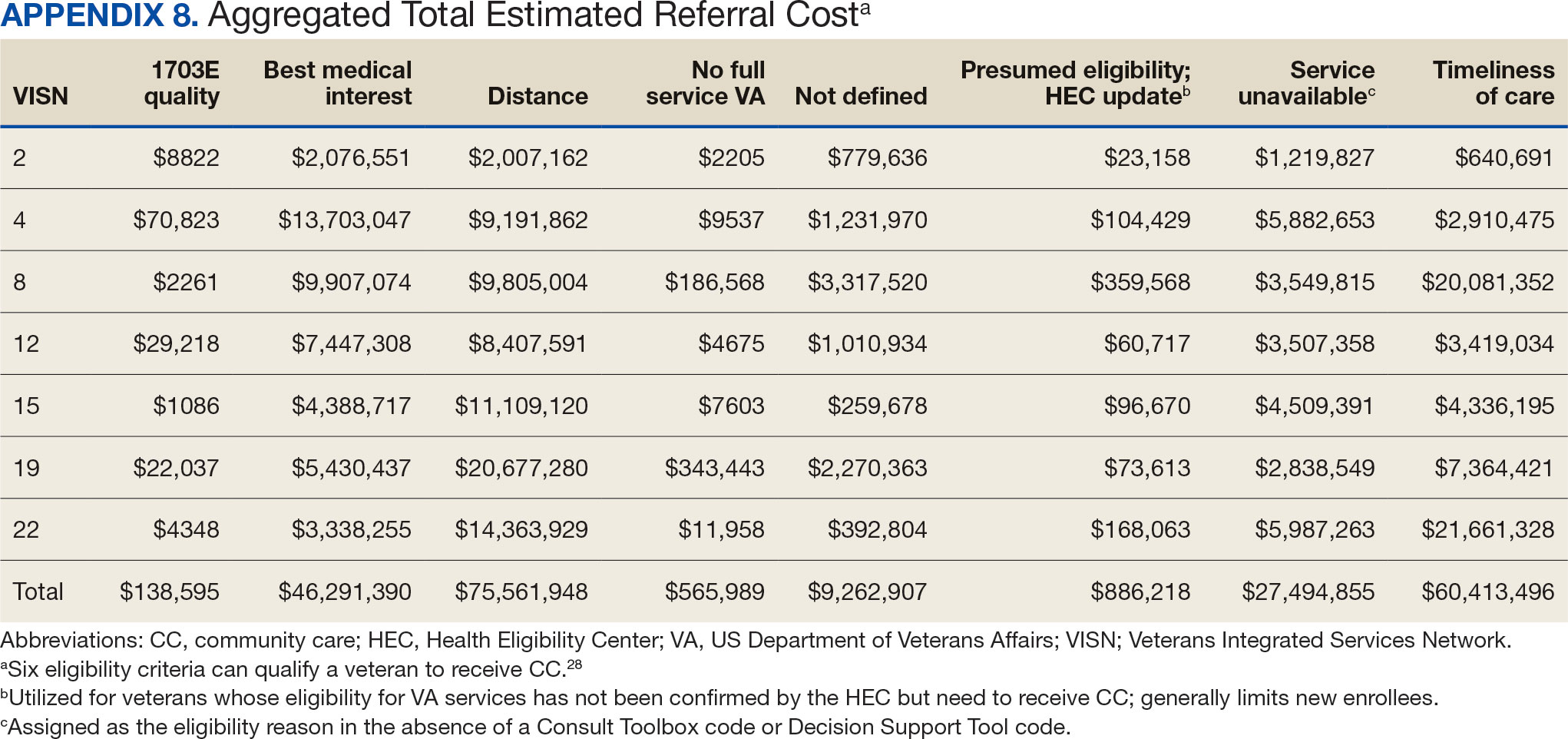

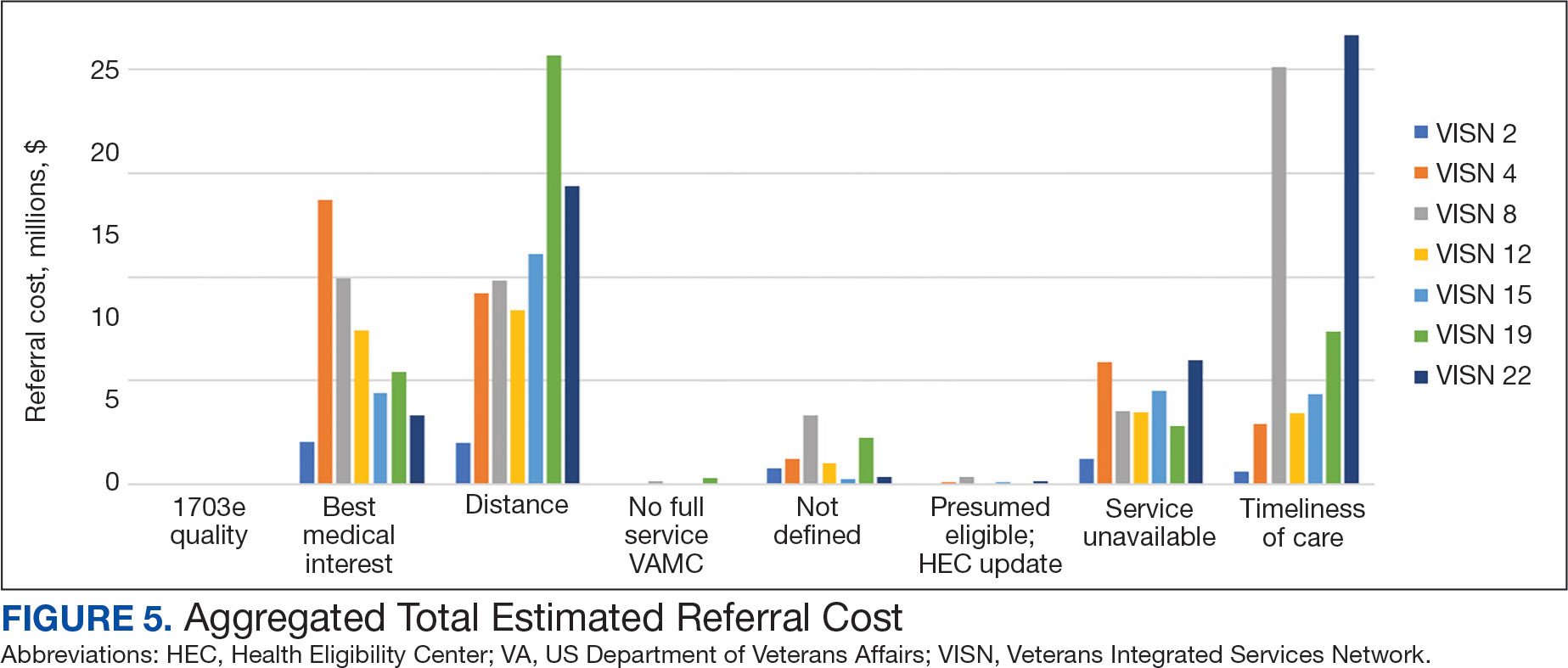

Overall costs were primarily driven by specific VISNs within each eligibility type (Appendix 8; Figure 5). VISN 19, VISN 22, and VISN 15 accounted for the highest referral costs for distance; VISN 22, VISN 8, and VISN 19 accounted for the secondhighest referral cost, timeliness of care; and VISN 4, VISN 8, and VISN 12 accounted for the third-highest referral cost, best medical interest (Figure 5). VISN 2, VISN 4, VISN 12, VISN 15, and VISN 22 had service unavailable as an eligibility type with 1 of the top 3 associated referral costs, which was higher in cost than timeliness of care for VISN 2, VISN 4, VISN 12, and VISN 15.

Discussion

This study examines the referral of rehabilitation PT services to CC, evaluates CC costs for PT services, and analyzes utilization and cost trends among veterans within the VHA. Utilization data demonstrated a decrease in referrals from FY 2019 to FY 2020 and increases in referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022 for most variables of interest, with cost data exhibiting similar trends. Results highlight the need for further investigation to address variations in PT referrals and costs across VISNs and eligibility reasons for CC referral.

Results demonstrated a noteworthy increase in PT CC referrals over time. The largest increase occurred from FY 2020 to FY 2021, with a smaller increase from FY 2021 to FY 2022. During this period, total enrollee numbers decreased by 3.0% across the 7 VISNs included in this analysis and by 1.6% across all VISNs, a trend that illustrates an overall decrease in enrollees as CC use increased. Results align with the implementation of the MISSION Act of 2018, which further expanded veterans’ options to use CC.1,6,7 Results also align with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted care access for many veterans, placed a larger emphasis on the use of telehealth, and increased opportunities to stay within the VA for care by rapidly shifting to telehealth and leveraging telerehabilitation investments and initiatives (such as TR-EWI).20,31

VISN 8, VISN 19, and VISN 22, accounted for more than half of PT referrals. These VISNs had higher enrollee counts compared to the other VISNs.32 VISN 8 consistently had high levels of referrals, whereas VISN 19 and VISN 22 saw dramatic increases in FY 2021 and FY 2022. In contrast, VISN 4 and VISN 12 gradually decreased referrals during the study. VISN 2 had the lowest referral numbers during the study period, and all stations with the lowest individual referral numbers were located within VISN 2. Of the VISNs included in this study, VISN 2 had the second lowest number of enrollees (324,042).32 Reasons for increases and decreases over time could not be determined based on data collected in this study.

There were more urban than rural PT CC referrals; however, both exhibited an increase in referrals over time. This is consistent with population trends showing that most VHA patients (62.6%) and veterans (75.9%) reside in urban areas, which could explain some of the trends in this study.33 Some VISNs have larger urban catchment areas (eg, VISN 8 and VISN 22), and some have larger rural catchment areas (eg, VISN 15 and VISN 19), which could partially explain the rural-urban differences by VISN.32 Rural-urban referral trends might also reflect existing health care delivery system deficits in rural areas and known challenges associated with accessing health care for veterans living in rural communities.8,9

This study found larger differences in rural and urban PT CC referrals for younger age groups, with more than twice as many urban referrals in veterans aged 20 to 29 years and aged 30 to 39 years, and roughly 1.8 times as many urban referrals in veterans aged 40 to 49 years. However, there were similar numbers of rural and urban referrals in those aged 70 to 79 years and aged 80 to 89 years. These trends are consistent with data showing veterans residing in rural communities are older than their urban counterparts.23,34 Data suggest that older veteran populations might seek PT at higher rates than younger veteran populations. Moreover, data suggest there could be differences in PT-seeking rates for younger veteran populations who reside in rural vs urban areas. Additional research is needed to understand these trends.

Distance and timeliness of care were the predominant reasons for referral among eligibility groups, which is consistent with the MISSION Act goals.1,6,7 The most common eligibility reason for rural referrals was distance; timeliness of care was most common for urban referrals. This finding is expected, as veterans living in rural communities are farther away from VHA facilities and have longer drive times, whereas veterans living in urban communities might live closer, yet experience longer wait times due to services and/or appointment availability. Best medical interest accounted for almost 20% of referrals, which does not provide detailed insights into why those veterans were referred to CC.

The top PT diagnoses referred to CC were related to bone, joint, or soft tissue disorders of the lower back, shoulder, and knee. This suggests that musculoskeletal-related issues are prevalent among veterans seeking PT care, which is consistent with research that found > 50% of veterans receiving VHA care have musculoskeletal disorders.35 The probability of experiencing musculoskeletal problems increases with age, as does the need for PT services. Amputations and fractures accounted for < 1% of CC referrals, which is consistent with the historic provision of VHA clinical specialized care to conditions prevalent among veterans. It may also represent VHA efforts to internally provide care for complex conditions requiring more extensive interdisciplinary coordination.

The total cost of referrals over time was about $221 million. VISN 8 accounted for the highest overall cost; VISN 2 had the lowest, mirroring referral utilization trends and aligning with VISN enrollee numbers. VISN 19 and VISN 22 reported large cost increases from FY 2020 to FY 2021. Total referral costs increased by $34.9 million from FY 2020 to FY 2021, which may be due to health care inflation (2.9% during FY 2019 to FY 2022), increased awareness of CC services, or increased VHA wait times.36 Additionally, there were limitations in care provided across health care systems during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the VA.5 The increase from FY 2020 to FY 2021 may reflect a rebound from restrictions in appointments across VA, CC, and the private sector.

While the increase in total referral cost may be partly attributed to inflation, the cost effectiveness and efficiency of referring veterans to CC vs keeping veterans within VHA care is an ongoing debate.5 Examining and addressing cost drivers within the top eligibility types and their respective VISNs is necessary to determine resource allocation and improve quality of care. This study found that best medical interest and unavailable services accounted for 33.4% of the total cost of CC referrals, highlighting the need for policies that strengthen in-house competencies and recruit personnel to provide PT services currently unavailable within the VA.

Future Directions

The VHA should explore opportunities for in-house care, especially for services appropriate for telehealth.18,20,37 Data indicated a smaller cost increase from FY 2021 to FY 2022 compared to the relatively large increase from FY 2020 to FY 2021. The increased telehealth usage across VHA by TR-EWI and non—TR-EWI sites within selected VISNs may have contributed to limiting the increase in CC costs. Future studies should investigate contextual factors of increased telehealth usage, which would offer guidance for implementation to optimize the integration of telehealth with PT rehabilitation provided in-house. Additionally, future studies can examine potential limitations experienced during PT telehealth visits, such as the inability to conduct hands-on assessments, challenges in viewing the quality of patient movement, ensuring patient safety in the remote environment, and the lack of PT equipment in homes for telehealth visits, and how these challenges are being addressed.38,39 Research is also needed to understand tradeoffs of CC vs VHA care and the potential and cost benefits of keeping veterans within VHA using programs like TR-EWI.5 Veterans living in rural communities may especially benefit from this as expanding telehealth options can provide access to PT care that may not be readily available, enabling them to stay connected and engaged in their care.18,40

Future studies could examine contributory factors to rising costs, such as demographic shifts, changes in PT service utilization, and policy. Researchers might also consider qualitative studies with clinicians and veterans within each VISN, which may provide insights into how local factors impact PT referral to the community.

Limitations

Due to its descriptive nature, this study can only speculate about factors influencing trends. Limitations include the inability to link the Palantir and CC Dashboard datasets for cost comparisons and potential data change over time on Palantir due to platform updates. The focus on VISNs with TREWI sites limited generalizability and this study did not compare CC PT vs VHA PT. Finally, there may have been cost drivers not identified in this study.

Conclusions

This descriptive study provides insights into the utilization and cost of PT CC referrals for selected VISNs. Cost trends underscore the financial commitment to providing PT services to veterans. Understanding what factors are driving this cost is necessary for VHA to optimally provide and manage the rehabilitation resources needed to serve veterans through traditional in-person care, telehealth, and CC options while ensuring timely, highquality care.

- Congressional Budget Office. The Veterans Community Care Program: Background and Early Effects. October 26, 2021. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57257

- US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Providing Health Care for Veterans. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.va.gov/health/

- Davila H, Rosen AK, Beilstein-Wedel E, Shwartz M, Chatelain LJ, Gurewich D. Rural veterans’ experiences with outpatient care in the Veterans Health Administration versus community care. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 3):S286-S291. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001552

- Vanneman ME, Wagner TH, Shwartz M, et al. Veterans’ experiences with outpatient care: comparing the Veterans Affairs system with community-based care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1368-1376. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01375

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10(3):9.

- Feyman Y, Legler A, Griffith KN. Appointment wait time data for primary & specialty care in veterans health administration facilities vs. community medical centers. Data Brief. 2021;36:107134. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2021.107134

- Kelley AT, Greenstone CL, Kirsh SR. Defining access and the role of community care in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1584-1585. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05358-z

- Garvin LA, Pugatch M, Gurewich D, Pendergast JN, Miller CJ. Interorganizational care coordination of rural veterans by Veterans Affairs and community care programs: a systematic review. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 3):S259-S269. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001542

- US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Rural Veterans: Rural Veteran Health Care Challenges. Updated May 14, 2024. Accessed September 23, 2024. https:// www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp

- Ohl ME, Carrell M, Thurman A, et al. “Availability of healthcare providers for rural veterans eligible for purchased care under the veterans choice act.” BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):315. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3108-8

- Mattocks KM, Cunningham KJ, Greenstone C, Atkins D, Rosen AK, Upton M. Innovations in community care programs, policies, and research. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 3):S229-S231. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001550

- Doyle JM, Streeter RA. Veterans’ location in health professional shortage areas: implications for access to care and workforce supply. Health Serv Res. 2017;52 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):459-480. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12633

- Patzel M, Barnes C, Ramalingam N, et al. Jumping through hoops: community care clinician and staff experiences providing primary care to rural veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(Suppl 3):821-828. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08126-2

- Mattocks KM, Kroll-Desrosiers A, Kinney R, Elwy AR, Cunningham KJ, Mengeling MA. Understanding VA’s use of and relationships with community care providers under the MISSION Act. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 3):S252-S258. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001545

- Olenick M, Flowers M, Diaz VJ. US veterans and their unique issues: enhancing health care professional awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:635-639. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S89479

- Campbell P, Pope R, Simas V, Canetti E, Schram B, Orr R. The effects of early physiotherapy treatment on musculoskeletal injury outcomes in military personnel: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(20):13416. doi:10.3390/ijerph192013416

- Gurewich D, Shwartz M, Beilstein-Wedel E, Davila H, Rosen AK. Did access to care improve since passage of the veterans choice act? Differences between rural and urban veterans. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 3):S270-S278. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001490

- Myers US, Birks A, Grubaugh AL, Axon RN. Flattening the curve by getting ahead of it: how the VA healthcare system is leveraging telehealth to provide continued access to care for rural veterans. J Rural Health. 2021;37(1):194-196. doi:10.1111/jrh.12449

- Hale-Gallardo JL, Kreider CM, Jia H, et al. Telerehabilitation for rural veterans: a qualitative assessment of barriers and facilitators to implementation. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:559-570. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S247267

- Kreider CM, Hale-Gallardo J, Kramer JC, et al. Providers’ shift to telerehabilitation at the U.S. Veterans Health Administration during COVID-19: practical applications. Front Public Health. 2022;10:831762. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.831762

- Cowper-Ripley DC, Jia H, Wang X, et al. Trends in VA telerehabilitation patients and encounters over time and by rurality. Fed Pract. 2019;36(3):122-128.

- US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. VHA Office of Rural Health. Updated August 30, 2024. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/index.asp

- National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Rural Veterans: 2021-2023. April 2023. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.datahub.va.gov/stories/s/Rural-Veterans-FY2021-2023/kkh2-eymp/

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research & Development. Program Guide: 1200.21, VHA Operations Activities That May Constitute Research. January 9, 2019. https://www.research.va.gov/resources/policies/ProgramGuide-1200-21-VHA-Operations-Activities.pdf

- Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. J Nurs Care Qual. 2016;31(1):1-8. doi:10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000153

- US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration: Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). Updated January 29, 2024. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTH/visns.asp

- Stomberg C, Frost A, Becker C, Stang H, Windschitl M, Carrier E. Community Care referral dashboard [Data dashboard]. https://app.powerbigov.us/groups/me/reports/090d22a7-0e1f-4cc5-bea8-0a1b87aa0bd9/ReportSectionacfd03cdebd76ffca9ec [Source not verified]

- US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Eligibility for community care outside VA. Updated May 30, 2024. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/programs/veterans/General_Care.asp

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. How to define rurality fact sheet. Updated December 2023. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/ORH_RuralityFactSheet_508.pdf

- Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. Economic Research Service, US Dept of Agriculture. Updated September 25, 2023. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx

- Gurewich D, Beilstein-Wedel E, Shwartz M, Davila H, Rosen AK. Disparities in wait times for care among US veterans by race and ethnici t y. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2252061. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.52061

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Office of Rural Health, Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Gainesville, GeoSpatial Outcomes Division. VA and Community Healthcare, and VHA Rurality web map application. Published 2023. https://portal.vhagis.inv.vaec.va.gov/arcgis/apps/webappbuilder/index.html [source not verified]

- Chartbook on Healthcare for Veterans: National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 2020. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/chartbooks/veterans/index.html

- Lum HD, Nearing K, Pimentel CB, Levy CR, Hung WW. Anywhere to anywhere: use of telehealth to increase health care access for older, rural veterans. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2020;30(1):12-18. doi:10.1093/ppar/prz030

- Goulet JL, Kerns RD, Bair M, et al. The musculoskeletal diagnosis cohort: examining pain and pain care among veterans. Pain. 2016;157(8):1696-1703. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000567

- US Inflation Calculator. Health Care Inflation in the United States (1948-2024). Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/health-care-inflation-in-the-united-states/

- Cottrell MA, Galea OA, O’Leary SP, Hill AJ, Russell TG. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(5):625-638. doi:10.1177/0269215516645148

- Elor A, Conde S, Powel l M, Robbins A, Chen NN, Kurniawan S. Physical therapist impressions of telehealth and virtual reality needs amidst a pandemic. Front Virtual Real. 2022;3. doi:10.3389/frvir.2022.915332

- Lee AC, Harada N. Telehealth as a means of health care delivery for physical therapist practice. Phys Ther. 2012;92(3):463-468. doi:10.2522/ptj.20110100

- Hynes DM, Edwards S, Hickok A, et al. Veterans’ use of Veterans Health Administration primary care in an era of expanding choice. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 3):S292- S300. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001554

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health system, providing care to veterans through VHA and non-VHA practitioners and facilities.1,2 Providing high-quality, timely, and veteran-centric care remains a priority for the VHA. Legislative efforts have expanded opportunities for eligible veterans to receive care in the community purchased by VHA, known as community care (CC).1 The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 came in response to reports of long wait times and drive times for patients.3-5 The MISSION Act of 2018 expanded access to CC by streamlining it and broadening eligibility criteria, especially for veterans in rural communities who often experience more barriers in accessing care than veterans living in urban communities.1,6-10 Since the implementation of the Choice and MISSION Acts, > 2.7 million veterans have received care through community practitioners within the VHA CC network.11

Background

Increased access to CC could benefit veterans living in rural communities by increasing care options and circumventing challenges to accessing VHA care (ie, geographic, transportation, and distance barriers, practitioner and specialist shortages, and hospital closures). 5,9,10,12,13 However, health care system deficits in rural areas could also limit CC effectiveness for veterans living in those communities. 3 Other challenges posed by using CC include care coordination, information sharing, care continuity, delayed payments to CC practitioners, and mixed findings regarding CC quality.5,8,13,14 VHA practitioners are specifically trained to meet the multifaceted needs unique to veterans’ health and subculture, training CC practitioners may not receive.5,15

CC offers services for primary care and a broad range of specialties, including rehabilitation services such as physical therapy (PT).6 PT is used for the effective treatment of various conditions veterans experience and promote wellbeing and independence.16 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) databases reveal a high prevalence of veterans receiving PT services through CC; PT is one of the most frequently used CC outpatient specialty services by veterans living in rural communities.14,17

Telerehabitltation Enterprisewide Initiative

VHA has greatly invested in delivering care virtually, especially for veterans living in rural communities.18 In 2017, the VHA Office of Rural Health funded the Telerehabilitation Enterprise-Wide Initiative (TR-EWI) in partnership with the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Services national program office to increase access to specialized rehabilitation services for veterans living in rural communities by leveraging telehealth technologies.18-21 This alternative mode of health care delivery allows clinicians to overcome access barriers by delivering rehabilitation therapies directly to veterans' homes or nearby community-based outpatient clinics. TR-EWI was conceived as a hub-and-spoke model, where rehabilitation expertise at the hub was virtually delivered to spoke sites that did not have in-house expertise. In subsequent years, the TR-EWI also evolved to provide targeted telerehabilitation programs within rural-serving community-based outpatient clinics, including PT as a predominant service.19,20

As TR-EWI progressed—and in conjunction with the uptake of telehealth across VHA during the COVID-19 pandemic—there has been increased focus on PT telerehabilitation, especially for the 4.6 million veterans in rural communities.18,22,23 Because health care delivery system deficits in rural areas could limit the effective use of CC, many TR-EWI sites hope to reduce their CC referrals by providing telehealth PT services to veterans who might otherwise need to be referred to CC. This strategy aligns with VHA goals of providing high-quality and timely care. To better understand opportunities for programs like TR-EWI to provide rehabilitation services for veterans and reduce care sent to the community, research that examines CC referral trends for PT over time is warranted.

This study examines CC from a rehabilitation perspective with a focus on CC referral trends for PT, specifically for Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) where TREWI sites are located. The study’s objectives were to describe rehabilitation PT services being referred to CC and examine associated CC costs for PT services. Two research questions guided the study. First, what are the utilization trends for CC PT referrals from fiscal year (FY) 2019 to FY 2022? Secondly, what is the cost breakdown of CC for PT referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022?

Methods

This study was conducted by a multidisciplinary team comprised of public health, disability, rehabilitation counseling, and PT professionals. It was deemed a quality improvement project under VA guidance and followed the SQUIRE guidelines for quality improvement reporting.24,25 The study used the VA Common Operating Platform (Palantir) to obtain individual-level CC referral data from the HealthShare Referral Manager (HSRM) database and consult data from the Computerized Patient Record System. Palantir is used to store and integrate VA data derived from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and VHA Support Service Center. Referrals are authorizations for care to be delivered by a CC practitioner.

TR-EWI is comprised of 7 sites: VISN 2, VISN 4, VISN 8, VISN 12, VISN 15, VISN 19, and VISN 22. Each site provides telerehabilitation services with an emphasis on reaching veterans living in rural communities. We joined the referrals and consults cubes in Palantir to extract PT referrals for FY 2019 to FY 2022 for the 7 VISNs with TR-EWI sites and obtain referral-specific information and demographic characteristics. 26 Data were extracted in October 2022.

The VHA Community Care Referral Dashboard (CC Dashboard) provided nonindividual level CC cost data.27 The CC Dashboard provides insights into the costs of CC services for VHA enrollees by category of care, standardized episode of care, and eligibility. Data are based on nationallevel HSRM referrals that are not suspended or linked to a canceled or discontinued consult. Data were aggregated by VISN. The dashboard only includes referrals dating back to FY 2020; therefore, PT data from FY 2020 through FY 2022 for VISNs with TR-EWI sites were collected. Data were extracted in December 2022.

This study examined CC referrals, station name, eligibility types, clinical diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes), and demographic information in the Palantir dataset. Six eligibility criteria can qualify a veteran to receive CC.28 Within clinical diagnoses, the variable of interest was the provisional diagnosis. Patient demographics included age, gender, and rurality of residence, as determined by the Rural-Urban Commuting Area system.29,30 Rural and highly rural categories were combined for analysis. For the CC cost dataset, this study examined CC referrals, referral cost, and eligibility type.

Analysis

For the first research question, we examined referral data from FY 2019 to FY 2022 using the Palantir dataset, performed descriptive statistical analysis for all variables, and analyzed data to identify trends. Descriptive statistics were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 29.0.0.0.

A qualitative analysis of provisional diagnosis data revealed what is being referred to CC for PT. A preliminary overview of provisional diagnosis data was conducted to familiarize coders with the data. We developed a coding framework to categorize diagnoses based on anatomical location, body structure, and clinical areas of interest. Data were reviewed individually and grouped into categories within the coding framework before meeting as a team to achieve group consensus on categorization. We then totaled the frequency of occurrence for provisional diagnoses within each category. Qualitative analyses were completed using Microsoft Excel.

For the second research question, the study used the CC cost dataset to examine the cost breakdown of CC PT referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022. We calculated the number and cost of PT referrals across eligibility groups for each FY and VISN. Data were analyzed using SPSS to identify cost trends.

Results

There were 344,406 referrals to CC for PT from FY 2019 to FY 2022 for the 7 VISNs analyzed (Table 1). Of these, 22.5% were from FY 2019, 19.1% from FY 2020, 28.2% from FY 2021, and 30.3% from FY 2022. VISN 8 and VISN 22 reported the most overall PT referrals, with VISN 8 comprising 22.2% and VISN 22 comprising 18.1% of all referrals. VISN 2 reported the least overall referrals (3.7%). VISN 4 and VISN 12 had decreases in referrals over time. VISN 2 and VISN 15 had decreases in referrals from FY 2019 to FY 2021 and slight increases from FY 2021 to FY 2022. VISN 19 and VISN 22 both saw slight increases from FY 2019 to FY 2020 and substantial increases from FY 2020 to FY 2022, with FY 2022 accounting for 40.0% and 42.3% of all referrals for VISN 19 and VISN 20, respectively (Figure 1).

For FY 2019 and FY 2020, VISN 8 had the highest percentage of referrals (26.7% and 23.2%, respectively), whereas VISN 22 was among the lowest (7.3% and 11.4%, respectively). However, for FY 2021 and FY 2022, VISN 22 reported the highest percentage of referrals (23.5% and 25.3%, respectively) compared to all other VISNs. VISN 2 consistently reported the lowest percentage of referrals across all years.

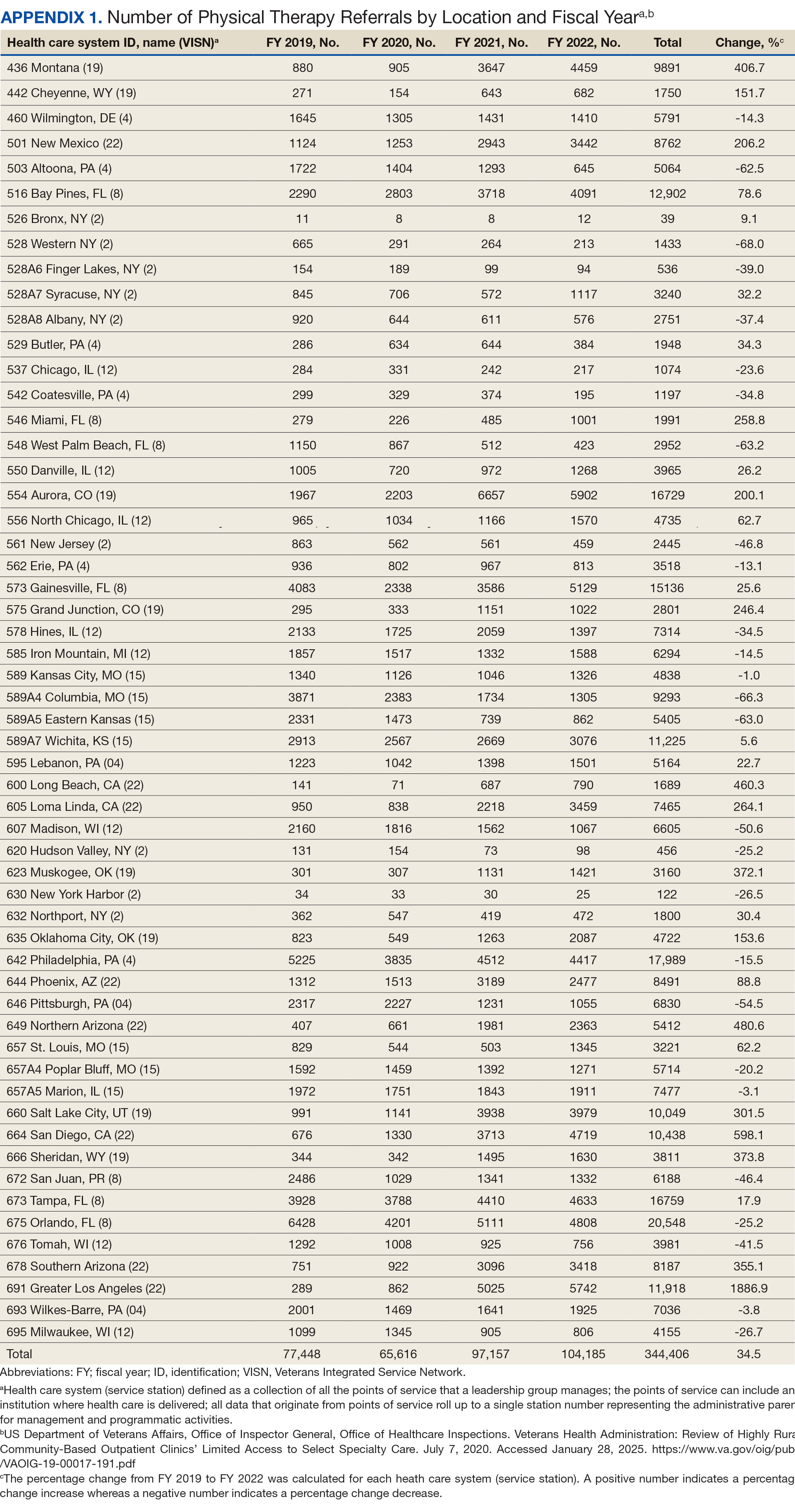

There were 56 stations analyzed across the 7 VISNs (Appendix 1). Nine stations each accounted for ≥ 3.0% of the total PT referrals and only 2 stations accounted for > 5.0% of referrals. Orlando, Florida (6.0%), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (5.2%), Tampa, Florida (4.9%), Aurora, Colorado (4.9%), and Gainesville, Florida (4.4%) reported the top 5 highest referrals, with 3 being from VISN 8 (Orlando, Tampa, Gainesville). Stations with the lowest reported referrals were all in VISN 2 in New York: The Bronx, (0%), New York Harbor (0%), Hudson Valley (0.1%) and Finger Lakes (0.2%).

Rurality

Urban stations comprised 56.2% and rural stations comprised 39.8% of PT CC referrals, while 0.2% of referrals were from insular isle US territories: Guam, American Samoa, Northern Marianas, and the Virgin Islands. The sample had missing or unknown data for 3.8% of referrals. FY 2022 had the largest difference in rural and urban referrals. Additionally, there was an overall trend of more referrals over time for rural and urban, with a large increase in rural (+40.0%) and urban (+62.7%) referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2021 and a modest increase from FY 2021 to FY 2022 (+5.2% for rural and +9.1% for urban). There was a decrease in rural (-7.0%) and urban (-3.5%) referrals from FY 2019 to FY 2020 (Figure 2).

There were differences in referrals by rurality and VISN (Table 2). VISN 12, VISN 15, and VISN 19 reported more rural than urban referrals, whereas VISN 4, VISN 8, and VISN 22 reported more urban than rural referrals. VISN 2 reported similar numbers for both, with slightly more urban than rural referrals. When reviewing trends over time for each FY, VISN 12, VISN 15, and VISN 19 reported more rural than urban referrals and VISN 4, VISN 8, and VISN 22 had more urban than rural referrals. In FY 2019 and FY 2020, VISN 2 reported slightly more urban than rural referrals but almost the same number of referrals in FY 2021 and FY 2022 (Appendix 2).

Demographics

The mean (SD) age was 61.2 (15.8) years (range, 20-105). Most PT CC referrals were for veterans aged 70 to 79 years (26.9%), followed by 60 to 69 years (20.7%), and 50 to 59 years (16.4%) (Appendix 3). Trends were consistent across VISNs. There was less of a difference between rural and urban referral percentages as the population aged. Veterans aged < 49 years residing in more urban areas accounted for more referrals to CC compared to their rural counterparts. This difference was less apparent in the 70 to 79 years and 80 to 89 years age brackets.

Most PT CC referrals (81.2%) were male and 14.8% were female. About 3.6% of referral data were missing sex information, and there was a smaller difference between male veterans living in rural communities and male veterans living in urban communities compared with female veterans. A total of 42.9% of male veterans resided in rural areas compared to 56.8% in urban areas; 32.7% of female veterans resided in rural areas compared to 66.9% in urban areas (Appendix 3).

Other Criteria

Of the 334,406 referrals, 114,983 (34.4%) had eligibility data, mostly from FY 2021 and FY 2022 (Table 3). Available eligibility data were likely affected by the MISSION Act and new regulations for reporting CC eligibility. Distance (33.4%) was the most common eligibility criteria, followed by timeliness of care (28.8%), and best medical interest (19.8%); 40.4% were rural and 59.5% were urban. Distance (55.4%) was most common for rural veterans, while timeliness of care (39.7%) was most common for urban veterans. For both groups, the second most common eligibility reason was best medical interest (Appendix 4).

Bone, joint, or soft tissue disorders were common diagnoses, with 25.2% located in the lower back, 14.7% in the shoulder, and 12.8% in the knee (Appendix 5). Amputations of the upper and lower limbs, fractures, cancer-related diagnoses, integumentary system disorders, thoracic and abdominal injuries and disorders, and other medical and mental health conditions each accounted for < 1% of the total diagnoses.

Costs

At time of analysis, the CC Dashboard had cost data available for 200,204 CC PT referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022. The difference in referral numbers for the 2 datasets is likely attributed to several factors: CC cost data is exclusively from the HSRM, whereas Palantir includes other data sources; how VA cleans data pulled into Palantir; how the CC Dashboard algorithm populates data; and variances based on timing of reporting and/or if referrals are eventually canceled.

The total cost of PT CC referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022 in selected VISNs was about $220,615,399 (Appendix 6). Appendix 7 details the methodology for determining the average standardized episode- of-care cost by VISN and how referral costs are calculated. Data show a continuous increase in total estimated cost from $46.8 million in FY 2020 to $92.1 million in FY 2022. From FY 2020 to FY 2022, aggregate costs ranged from $6,758,053 in VISN 2 to $47,209,162 in VISN 8 (Figure 3). The total referral cost for PT was highest at VISN 4 in FY 2020 ($10,447,140) and highest at VISN 22 in FY 2021 ($18,835,657) and FY 2022 ($22,962,438) (Figure 4). For referral costs from FY 2020 to FY 2022, distance accounted for $75,561,948 (34.3%), timeliness of care accounted for $60,413,496 (27.3%), and best medical interest accounted for $46,291,390 (21.0%) (Table 4).

Overall costs were primarily driven by specific VISNs within each eligibility type (Appendix 8; Figure 5). VISN 19, VISN 22, and VISN 15 accounted for the highest referral costs for distance; VISN 22, VISN 8, and VISN 19 accounted for the secondhighest referral cost, timeliness of care; and VISN 4, VISN 8, and VISN 12 accounted for the third-highest referral cost, best medical interest (Figure 5). VISN 2, VISN 4, VISN 12, VISN 15, and VISN 22 had service unavailable as an eligibility type with 1 of the top 3 associated referral costs, which was higher in cost than timeliness of care for VISN 2, VISN 4, VISN 12, and VISN 15.

Discussion

This study examines the referral of rehabilitation PT services to CC, evaluates CC costs for PT services, and analyzes utilization and cost trends among veterans within the VHA. Utilization data demonstrated a decrease in referrals from FY 2019 to FY 2020 and increases in referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022 for most variables of interest, with cost data exhibiting similar trends. Results highlight the need for further investigation to address variations in PT referrals and costs across VISNs and eligibility reasons for CC referral.

Results demonstrated a noteworthy increase in PT CC referrals over time. The largest increase occurred from FY 2020 to FY 2021, with a smaller increase from FY 2021 to FY 2022. During this period, total enrollee numbers decreased by 3.0% across the 7 VISNs included in this analysis and by 1.6% across all VISNs, a trend that illustrates an overall decrease in enrollees as CC use increased. Results align with the implementation of the MISSION Act of 2018, which further expanded veterans’ options to use CC.1,6,7 Results also align with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted care access for many veterans, placed a larger emphasis on the use of telehealth, and increased opportunities to stay within the VA for care by rapidly shifting to telehealth and leveraging telerehabilitation investments and initiatives (such as TR-EWI).20,31

VISN 8, VISN 19, and VISN 22, accounted for more than half of PT referrals. These VISNs had higher enrollee counts compared to the other VISNs.32 VISN 8 consistently had high levels of referrals, whereas VISN 19 and VISN 22 saw dramatic increases in FY 2021 and FY 2022. In contrast, VISN 4 and VISN 12 gradually decreased referrals during the study. VISN 2 had the lowest referral numbers during the study period, and all stations with the lowest individual referral numbers were located within VISN 2. Of the VISNs included in this study, VISN 2 had the second lowest number of enrollees (324,042).32 Reasons for increases and decreases over time could not be determined based on data collected in this study.

There were more urban than rural PT CC referrals; however, both exhibited an increase in referrals over time. This is consistent with population trends showing that most VHA patients (62.6%) and veterans (75.9%) reside in urban areas, which could explain some of the trends in this study.33 Some VISNs have larger urban catchment areas (eg, VISN 8 and VISN 22), and some have larger rural catchment areas (eg, VISN 15 and VISN 19), which could partially explain the rural-urban differences by VISN.32 Rural-urban referral trends might also reflect existing health care delivery system deficits in rural areas and known challenges associated with accessing health care for veterans living in rural communities.8,9

This study found larger differences in rural and urban PT CC referrals for younger age groups, with more than twice as many urban referrals in veterans aged 20 to 29 years and aged 30 to 39 years, and roughly 1.8 times as many urban referrals in veterans aged 40 to 49 years. However, there were similar numbers of rural and urban referrals in those aged 70 to 79 years and aged 80 to 89 years. These trends are consistent with data showing veterans residing in rural communities are older than their urban counterparts.23,34 Data suggest that older veteran populations might seek PT at higher rates than younger veteran populations. Moreover, data suggest there could be differences in PT-seeking rates for younger veteran populations who reside in rural vs urban areas. Additional research is needed to understand these trends.

Distance and timeliness of care were the predominant reasons for referral among eligibility groups, which is consistent with the MISSION Act goals.1,6,7 The most common eligibility reason for rural referrals was distance; timeliness of care was most common for urban referrals. This finding is expected, as veterans living in rural communities are farther away from VHA facilities and have longer drive times, whereas veterans living in urban communities might live closer, yet experience longer wait times due to services and/or appointment availability. Best medical interest accounted for almost 20% of referrals, which does not provide detailed insights into why those veterans were referred to CC.

The top PT diagnoses referred to CC were related to bone, joint, or soft tissue disorders of the lower back, shoulder, and knee. This suggests that musculoskeletal-related issues are prevalent among veterans seeking PT care, which is consistent with research that found > 50% of veterans receiving VHA care have musculoskeletal disorders.35 The probability of experiencing musculoskeletal problems increases with age, as does the need for PT services. Amputations and fractures accounted for < 1% of CC referrals, which is consistent with the historic provision of VHA clinical specialized care to conditions prevalent among veterans. It may also represent VHA efforts to internally provide care for complex conditions requiring more extensive interdisciplinary coordination.

The total cost of referrals over time was about $221 million. VISN 8 accounted for the highest overall cost; VISN 2 had the lowest, mirroring referral utilization trends and aligning with VISN enrollee numbers. VISN 19 and VISN 22 reported large cost increases from FY 2020 to FY 2021. Total referral costs increased by $34.9 million from FY 2020 to FY 2021, which may be due to health care inflation (2.9% during FY 2019 to FY 2022), increased awareness of CC services, or increased VHA wait times.36 Additionally, there were limitations in care provided across health care systems during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the VA.5 The increase from FY 2020 to FY 2021 may reflect a rebound from restrictions in appointments across VA, CC, and the private sector.

While the increase in total referral cost may be partly attributed to inflation, the cost effectiveness and efficiency of referring veterans to CC vs keeping veterans within VHA care is an ongoing debate.5 Examining and addressing cost drivers within the top eligibility types and their respective VISNs is necessary to determine resource allocation and improve quality of care. This study found that best medical interest and unavailable services accounted for 33.4% of the total cost of CC referrals, highlighting the need for policies that strengthen in-house competencies and recruit personnel to provide PT services currently unavailable within the VA.

Future Directions

The VHA should explore opportunities for in-house care, especially for services appropriate for telehealth.18,20,37 Data indicated a smaller cost increase from FY 2021 to FY 2022 compared to the relatively large increase from FY 2020 to FY 2021. The increased telehealth usage across VHA by TR-EWI and non—TR-EWI sites within selected VISNs may have contributed to limiting the increase in CC costs. Future studies should investigate contextual factors of increased telehealth usage, which would offer guidance for implementation to optimize the integration of telehealth with PT rehabilitation provided in-house. Additionally, future studies can examine potential limitations experienced during PT telehealth visits, such as the inability to conduct hands-on assessments, challenges in viewing the quality of patient movement, ensuring patient safety in the remote environment, and the lack of PT equipment in homes for telehealth visits, and how these challenges are being addressed.38,39 Research is also needed to understand tradeoffs of CC vs VHA care and the potential and cost benefits of keeping veterans within VHA using programs like TR-EWI.5 Veterans living in rural communities may especially benefit from this as expanding telehealth options can provide access to PT care that may not be readily available, enabling them to stay connected and engaged in their care.18,40

Future studies could examine contributory factors to rising costs, such as demographic shifts, changes in PT service utilization, and policy. Researchers might also consider qualitative studies with clinicians and veterans within each VISN, which may provide insights into how local factors impact PT referral to the community.

Limitations

Due to its descriptive nature, this study can only speculate about factors influencing trends. Limitations include the inability to link the Palantir and CC Dashboard datasets for cost comparisons and potential data change over time on Palantir due to platform updates. The focus on VISNs with TREWI sites limited generalizability and this study did not compare CC PT vs VHA PT. Finally, there may have been cost drivers not identified in this study.

Conclusions

This descriptive study provides insights into the utilization and cost of PT CC referrals for selected VISNs. Cost trends underscore the financial commitment to providing PT services to veterans. Understanding what factors are driving this cost is necessary for VHA to optimally provide and manage the rehabilitation resources needed to serve veterans through traditional in-person care, telehealth, and CC options while ensuring timely, highquality care.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health system, providing care to veterans through VHA and non-VHA practitioners and facilities.1,2 Providing high-quality, timely, and veteran-centric care remains a priority for the VHA. Legislative efforts have expanded opportunities for eligible veterans to receive care in the community purchased by VHA, known as community care (CC).1 The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 came in response to reports of long wait times and drive times for patients.3-5 The MISSION Act of 2018 expanded access to CC by streamlining it and broadening eligibility criteria, especially for veterans in rural communities who often experience more barriers in accessing care than veterans living in urban communities.1,6-10 Since the implementation of the Choice and MISSION Acts, > 2.7 million veterans have received care through community practitioners within the VHA CC network.11

Background

Increased access to CC could benefit veterans living in rural communities by increasing care options and circumventing challenges to accessing VHA care (ie, geographic, transportation, and distance barriers, practitioner and specialist shortages, and hospital closures). 5,9,10,12,13 However, health care system deficits in rural areas could also limit CC effectiveness for veterans living in those communities. 3 Other challenges posed by using CC include care coordination, information sharing, care continuity, delayed payments to CC practitioners, and mixed findings regarding CC quality.5,8,13,14 VHA practitioners are specifically trained to meet the multifaceted needs unique to veterans’ health and subculture, training CC practitioners may not receive.5,15

CC offers services for primary care and a broad range of specialties, including rehabilitation services such as physical therapy (PT).6 PT is used for the effective treatment of various conditions veterans experience and promote wellbeing and independence.16 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) databases reveal a high prevalence of veterans receiving PT services through CC; PT is one of the most frequently used CC outpatient specialty services by veterans living in rural communities.14,17

Telerehabitltation Enterprisewide Initiative

VHA has greatly invested in delivering care virtually, especially for veterans living in rural communities.18 In 2017, the VHA Office of Rural Health funded the Telerehabilitation Enterprise-Wide Initiative (TR-EWI) in partnership with the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Services national program office to increase access to specialized rehabilitation services for veterans living in rural communities by leveraging telehealth technologies.18-21 This alternative mode of health care delivery allows clinicians to overcome access barriers by delivering rehabilitation therapies directly to veterans' homes or nearby community-based outpatient clinics. TR-EWI was conceived as a hub-and-spoke model, where rehabilitation expertise at the hub was virtually delivered to spoke sites that did not have in-house expertise. In subsequent years, the TR-EWI also evolved to provide targeted telerehabilitation programs within rural-serving community-based outpatient clinics, including PT as a predominant service.19,20

As TR-EWI progressed—and in conjunction with the uptake of telehealth across VHA during the COVID-19 pandemic—there has been increased focus on PT telerehabilitation, especially for the 4.6 million veterans in rural communities.18,22,23 Because health care delivery system deficits in rural areas could limit the effective use of CC, many TR-EWI sites hope to reduce their CC referrals by providing telehealth PT services to veterans who might otherwise need to be referred to CC. This strategy aligns with VHA goals of providing high-quality and timely care. To better understand opportunities for programs like TR-EWI to provide rehabilitation services for veterans and reduce care sent to the community, research that examines CC referral trends for PT over time is warranted.

This study examines CC from a rehabilitation perspective with a focus on CC referral trends for PT, specifically for Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) where TREWI sites are located. The study’s objectives were to describe rehabilitation PT services being referred to CC and examine associated CC costs for PT services. Two research questions guided the study. First, what are the utilization trends for CC PT referrals from fiscal year (FY) 2019 to FY 2022? Secondly, what is the cost breakdown of CC for PT referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022?

Methods

This study was conducted by a multidisciplinary team comprised of public health, disability, rehabilitation counseling, and PT professionals. It was deemed a quality improvement project under VA guidance and followed the SQUIRE guidelines for quality improvement reporting.24,25 The study used the VA Common Operating Platform (Palantir) to obtain individual-level CC referral data from the HealthShare Referral Manager (HSRM) database and consult data from the Computerized Patient Record System. Palantir is used to store and integrate VA data derived from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and VHA Support Service Center. Referrals are authorizations for care to be delivered by a CC practitioner.

TR-EWI is comprised of 7 sites: VISN 2, VISN 4, VISN 8, VISN 12, VISN 15, VISN 19, and VISN 22. Each site provides telerehabilitation services with an emphasis on reaching veterans living in rural communities. We joined the referrals and consults cubes in Palantir to extract PT referrals for FY 2019 to FY 2022 for the 7 VISNs with TR-EWI sites and obtain referral-specific information and demographic characteristics. 26 Data were extracted in October 2022.

The VHA Community Care Referral Dashboard (CC Dashboard) provided nonindividual level CC cost data.27 The CC Dashboard provides insights into the costs of CC services for VHA enrollees by category of care, standardized episode of care, and eligibility. Data are based on nationallevel HSRM referrals that are not suspended or linked to a canceled or discontinued consult. Data were aggregated by VISN. The dashboard only includes referrals dating back to FY 2020; therefore, PT data from FY 2020 through FY 2022 for VISNs with TR-EWI sites were collected. Data were extracted in December 2022.

This study examined CC referrals, station name, eligibility types, clinical diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes), and demographic information in the Palantir dataset. Six eligibility criteria can qualify a veteran to receive CC.28 Within clinical diagnoses, the variable of interest was the provisional diagnosis. Patient demographics included age, gender, and rurality of residence, as determined by the Rural-Urban Commuting Area system.29,30 Rural and highly rural categories were combined for analysis. For the CC cost dataset, this study examined CC referrals, referral cost, and eligibility type.

Analysis

For the first research question, we examined referral data from FY 2019 to FY 2022 using the Palantir dataset, performed descriptive statistical analysis for all variables, and analyzed data to identify trends. Descriptive statistics were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 29.0.0.0.

A qualitative analysis of provisional diagnosis data revealed what is being referred to CC for PT. A preliminary overview of provisional diagnosis data was conducted to familiarize coders with the data. We developed a coding framework to categorize diagnoses based on anatomical location, body structure, and clinical areas of interest. Data were reviewed individually and grouped into categories within the coding framework before meeting as a team to achieve group consensus on categorization. We then totaled the frequency of occurrence for provisional diagnoses within each category. Qualitative analyses were completed using Microsoft Excel.

For the second research question, the study used the CC cost dataset to examine the cost breakdown of CC PT referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022. We calculated the number and cost of PT referrals across eligibility groups for each FY and VISN. Data were analyzed using SPSS to identify cost trends.

Results

There were 344,406 referrals to CC for PT from FY 2019 to FY 2022 for the 7 VISNs analyzed (Table 1). Of these, 22.5% were from FY 2019, 19.1% from FY 2020, 28.2% from FY 2021, and 30.3% from FY 2022. VISN 8 and VISN 22 reported the most overall PT referrals, with VISN 8 comprising 22.2% and VISN 22 comprising 18.1% of all referrals. VISN 2 reported the least overall referrals (3.7%). VISN 4 and VISN 12 had decreases in referrals over time. VISN 2 and VISN 15 had decreases in referrals from FY 2019 to FY 2021 and slight increases from FY 2021 to FY 2022. VISN 19 and VISN 22 both saw slight increases from FY 2019 to FY 2020 and substantial increases from FY 2020 to FY 2022, with FY 2022 accounting for 40.0% and 42.3% of all referrals for VISN 19 and VISN 20, respectively (Figure 1).

For FY 2019 and FY 2020, VISN 8 had the highest percentage of referrals (26.7% and 23.2%, respectively), whereas VISN 22 was among the lowest (7.3% and 11.4%, respectively). However, for FY 2021 and FY 2022, VISN 22 reported the highest percentage of referrals (23.5% and 25.3%, respectively) compared to all other VISNs. VISN 2 consistently reported the lowest percentage of referrals across all years.

There were 56 stations analyzed across the 7 VISNs (Appendix 1). Nine stations each accounted for ≥ 3.0% of the total PT referrals and only 2 stations accounted for > 5.0% of referrals. Orlando, Florida (6.0%), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (5.2%), Tampa, Florida (4.9%), Aurora, Colorado (4.9%), and Gainesville, Florida (4.4%) reported the top 5 highest referrals, with 3 being from VISN 8 (Orlando, Tampa, Gainesville). Stations with the lowest reported referrals were all in VISN 2 in New York: The Bronx, (0%), New York Harbor (0%), Hudson Valley (0.1%) and Finger Lakes (0.2%).

Rurality

Urban stations comprised 56.2% and rural stations comprised 39.8% of PT CC referrals, while 0.2% of referrals were from insular isle US territories: Guam, American Samoa, Northern Marianas, and the Virgin Islands. The sample had missing or unknown data for 3.8% of referrals. FY 2022 had the largest difference in rural and urban referrals. Additionally, there was an overall trend of more referrals over time for rural and urban, with a large increase in rural (+40.0%) and urban (+62.7%) referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2021 and a modest increase from FY 2021 to FY 2022 (+5.2% for rural and +9.1% for urban). There was a decrease in rural (-7.0%) and urban (-3.5%) referrals from FY 2019 to FY 2020 (Figure 2).

There were differences in referrals by rurality and VISN (Table 2). VISN 12, VISN 15, and VISN 19 reported more rural than urban referrals, whereas VISN 4, VISN 8, and VISN 22 reported more urban than rural referrals. VISN 2 reported similar numbers for both, with slightly more urban than rural referrals. When reviewing trends over time for each FY, VISN 12, VISN 15, and VISN 19 reported more rural than urban referrals and VISN 4, VISN 8, and VISN 22 had more urban than rural referrals. In FY 2019 and FY 2020, VISN 2 reported slightly more urban than rural referrals but almost the same number of referrals in FY 2021 and FY 2022 (Appendix 2).

Demographics

The mean (SD) age was 61.2 (15.8) years (range, 20-105). Most PT CC referrals were for veterans aged 70 to 79 years (26.9%), followed by 60 to 69 years (20.7%), and 50 to 59 years (16.4%) (Appendix 3). Trends were consistent across VISNs. There was less of a difference between rural and urban referral percentages as the population aged. Veterans aged < 49 years residing in more urban areas accounted for more referrals to CC compared to their rural counterparts. This difference was less apparent in the 70 to 79 years and 80 to 89 years age brackets.

Most PT CC referrals (81.2%) were male and 14.8% were female. About 3.6% of referral data were missing sex information, and there was a smaller difference between male veterans living in rural communities and male veterans living in urban communities compared with female veterans. A total of 42.9% of male veterans resided in rural areas compared to 56.8% in urban areas; 32.7% of female veterans resided in rural areas compared to 66.9% in urban areas (Appendix 3).

Other Criteria

Of the 334,406 referrals, 114,983 (34.4%) had eligibility data, mostly from FY 2021 and FY 2022 (Table 3). Available eligibility data were likely affected by the MISSION Act and new regulations for reporting CC eligibility. Distance (33.4%) was the most common eligibility criteria, followed by timeliness of care (28.8%), and best medical interest (19.8%); 40.4% were rural and 59.5% were urban. Distance (55.4%) was most common for rural veterans, while timeliness of care (39.7%) was most common for urban veterans. For both groups, the second most common eligibility reason was best medical interest (Appendix 4).

Bone, joint, or soft tissue disorders were common diagnoses, with 25.2% located in the lower back, 14.7% in the shoulder, and 12.8% in the knee (Appendix 5). Amputations of the upper and lower limbs, fractures, cancer-related diagnoses, integumentary system disorders, thoracic and abdominal injuries and disorders, and other medical and mental health conditions each accounted for < 1% of the total diagnoses.

Costs

At time of analysis, the CC Dashboard had cost data available for 200,204 CC PT referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022. The difference in referral numbers for the 2 datasets is likely attributed to several factors: CC cost data is exclusively from the HSRM, whereas Palantir includes other data sources; how VA cleans data pulled into Palantir; how the CC Dashboard algorithm populates data; and variances based on timing of reporting and/or if referrals are eventually canceled.

The total cost of PT CC referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022 in selected VISNs was about $220,615,399 (Appendix 6). Appendix 7 details the methodology for determining the average standardized episode- of-care cost by VISN and how referral costs are calculated. Data show a continuous increase in total estimated cost from $46.8 million in FY 2020 to $92.1 million in FY 2022. From FY 2020 to FY 2022, aggregate costs ranged from $6,758,053 in VISN 2 to $47,209,162 in VISN 8 (Figure 3). The total referral cost for PT was highest at VISN 4 in FY 2020 ($10,447,140) and highest at VISN 22 in FY 2021 ($18,835,657) and FY 2022 ($22,962,438) (Figure 4). For referral costs from FY 2020 to FY 2022, distance accounted for $75,561,948 (34.3%), timeliness of care accounted for $60,413,496 (27.3%), and best medical interest accounted for $46,291,390 (21.0%) (Table 4).

Overall costs were primarily driven by specific VISNs within each eligibility type (Appendix 8; Figure 5). VISN 19, VISN 22, and VISN 15 accounted for the highest referral costs for distance; VISN 22, VISN 8, and VISN 19 accounted for the secondhighest referral cost, timeliness of care; and VISN 4, VISN 8, and VISN 12 accounted for the third-highest referral cost, best medical interest (Figure 5). VISN 2, VISN 4, VISN 12, VISN 15, and VISN 22 had service unavailable as an eligibility type with 1 of the top 3 associated referral costs, which was higher in cost than timeliness of care for VISN 2, VISN 4, VISN 12, and VISN 15.

Discussion

This study examines the referral of rehabilitation PT services to CC, evaluates CC costs for PT services, and analyzes utilization and cost trends among veterans within the VHA. Utilization data demonstrated a decrease in referrals from FY 2019 to FY 2020 and increases in referrals from FY 2020 to FY 2022 for most variables of interest, with cost data exhibiting similar trends. Results highlight the need for further investigation to address variations in PT referrals and costs across VISNs and eligibility reasons for CC referral.

Results demonstrated a noteworthy increase in PT CC referrals over time. The largest increase occurred from FY 2020 to FY 2021, with a smaller increase from FY 2021 to FY 2022. During this period, total enrollee numbers decreased by 3.0% across the 7 VISNs included in this analysis and by 1.6% across all VISNs, a trend that illustrates an overall decrease in enrollees as CC use increased. Results align with the implementation of the MISSION Act of 2018, which further expanded veterans’ options to use CC.1,6,7 Results also align with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted care access for many veterans, placed a larger emphasis on the use of telehealth, and increased opportunities to stay within the VA for care by rapidly shifting to telehealth and leveraging telerehabilitation investments and initiatives (such as TR-EWI).20,31

VISN 8, VISN 19, and VISN 22, accounted for more than half of PT referrals. These VISNs had higher enrollee counts compared to the other VISNs.32 VISN 8 consistently had high levels of referrals, whereas VISN 19 and VISN 22 saw dramatic increases in FY 2021 and FY 2022. In contrast, VISN 4 and VISN 12 gradually decreased referrals during the study. VISN 2 had the lowest referral numbers during the study period, and all stations with the lowest individual referral numbers were located within VISN 2. Of the VISNs included in this study, VISN 2 had the second lowest number of enrollees (324,042).32 Reasons for increases and decreases over time could not be determined based on data collected in this study.

There were more urban than rural PT CC referrals; however, both exhibited an increase in referrals over time. This is consistent with population trends showing that most VHA patients (62.6%) and veterans (75.9%) reside in urban areas, which could explain some of the trends in this study.33 Some VISNs have larger urban catchment areas (eg, VISN 8 and VISN 22), and some have larger rural catchment areas (eg, VISN 15 and VISN 19), which could partially explain the rural-urban differences by VISN.32 Rural-urban referral trends might also reflect existing health care delivery system deficits in rural areas and known challenges associated with accessing health care for veterans living in rural communities.8,9

This study found larger differences in rural and urban PT CC referrals for younger age groups, with more than twice as many urban referrals in veterans aged 20 to 29 years and aged 30 to 39 years, and roughly 1.8 times as many urban referrals in veterans aged 40 to 49 years. However, there were similar numbers of rural and urban referrals in those aged 70 to 79 years and aged 80 to 89 years. These trends are consistent with data showing veterans residing in rural communities are older than their urban counterparts.23,34 Data suggest that older veteran populations might seek PT at higher rates than younger veteran populations. Moreover, data suggest there could be differences in PT-seeking rates for younger veteran populations who reside in rural vs urban areas. Additional research is needed to understand these trends.

Distance and timeliness of care were the predominant reasons for referral among eligibility groups, which is consistent with the MISSION Act goals.1,6,7 The most common eligibility reason for rural referrals was distance; timeliness of care was most common for urban referrals. This finding is expected, as veterans living in rural communities are farther away from VHA facilities and have longer drive times, whereas veterans living in urban communities might live closer, yet experience longer wait times due to services and/or appointment availability. Best medical interest accounted for almost 20% of referrals, which does not provide detailed insights into why those veterans were referred to CC.