User login

FDA asked to approve add-on drug for eosinophilic COPD

GlaxoSmithKline asked the Food and Drug Administration to approve an interleuklin-5 antagonist as an add-on maintenance therapy for patients with eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The pharmaceutical and health care company is seeking approval of mepolizumab to be used specifically to treat COPD patients with an eosinophilic phenotype. The drug currently is indicated to treat patients aged 12 years or older with severe asthma and asthma with an eosinophilic phenotype and is sold under the name Nucala, according to a GlaxoSmithKline statement issued November 7.

Headache, injection site reaction, back pain, and fatigue are the most common adverse reactions seen in patients who took mepolizumab during clinical trials.

Mepolizumab is not approved for the treatment of COPD anywhere in the world, and GlaxoSmithKline intends to also ask other countries’ regulatory authorities to allow this drug to be sold as a therapy for COPD.

GlaxoSmithKline asked the Food and Drug Administration to approve an interleuklin-5 antagonist as an add-on maintenance therapy for patients with eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The pharmaceutical and health care company is seeking approval of mepolizumab to be used specifically to treat COPD patients with an eosinophilic phenotype. The drug currently is indicated to treat patients aged 12 years or older with severe asthma and asthma with an eosinophilic phenotype and is sold under the name Nucala, according to a GlaxoSmithKline statement issued November 7.

Headache, injection site reaction, back pain, and fatigue are the most common adverse reactions seen in patients who took mepolizumab during clinical trials.

Mepolizumab is not approved for the treatment of COPD anywhere in the world, and GlaxoSmithKline intends to also ask other countries’ regulatory authorities to allow this drug to be sold as a therapy for COPD.

GlaxoSmithKline asked the Food and Drug Administration to approve an interleuklin-5 antagonist as an add-on maintenance therapy for patients with eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The pharmaceutical and health care company is seeking approval of mepolizumab to be used specifically to treat COPD patients with an eosinophilic phenotype. The drug currently is indicated to treat patients aged 12 years or older with severe asthma and asthma with an eosinophilic phenotype and is sold under the name Nucala, according to a GlaxoSmithKline statement issued November 7.

Headache, injection site reaction, back pain, and fatigue are the most common adverse reactions seen in patients who took mepolizumab during clinical trials.

Mepolizumab is not approved for the treatment of COPD anywhere in the world, and GlaxoSmithKline intends to also ask other countries’ regulatory authorities to allow this drug to be sold as a therapy for COPD.

Aspirin responsiveness improved in some with OSA

Obstructive sleep apnea patients with endothelial dysfunction gained aspirin responsiveness after using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, according to the findings from a small study scheduled to be presented at CHEST 2017.

“Endothelial dysfunction is an important phenomenon implicated in cardiovascular morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients. While it has been demonstrated that CPAP improves endothelial function, our understanding of the pathophysiologic links between CPAP therapy and cardiovascular outcomes remain limited,” researchers wrote in the study’s abstract.

The researchers examined 18 patients’ endothelial function before and after using CPAP therapy for a median of 37 days, along with the relationship between endothelial function and aspirin responsiveness in these same patients. All study participants had been recently diagnosed with moderate to severe OSA and underwent modified peripheral artery tonometry and platelet aggregometry before and after beginning CPAP therapy. Most of the patients (14) demonstrated aspirin resistance at baseline.

Endothelial dysfunction was defined as having a reactive hyperemia index (RHI) of less than or equal to 1.67, while aspirin resistance was defined as having a reading of at least 550 aspirin reaction units (ARU).

At baseline, the average RHI of patients was 1.79 (standard deviation = 0.3), with 8 of the patients having had endothelial dysfunction. Following CPAP use, patients’ mean RHI increased to 1.94 (SD = 0.36), and endothelial dysfunction was present in just 5 of the study participants.*

After using CPAP, those patients with endothelial dysfunction at baseline were responsive to aspirin, with their average ARU reading at 520 following therapy. In contrast, those patients with normal endothelial function at baseline remained resistant to aspirin following CPAP use, based on mean ARU values before and after therapy.

Lirim Krveshi, DO, of Danbury (Conn.) Hospital, is scheduled to present this study, “A Prospective Cohort Study of Endothelial Function and its Relationship to Aspirin Responsiveness in OSA Patients,” on Sunday, Oct. 29, at 1:45 p.m. in Convention Center, room 601A. This presentation is part of the Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Insights & Management session, running from 1:30 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.

The study’s authors reported no conflicts of interest.

*This article was updated Oct. 27, 2017.

Obstructive sleep apnea patients with endothelial dysfunction gained aspirin responsiveness after using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, according to the findings from a small study scheduled to be presented at CHEST 2017.

“Endothelial dysfunction is an important phenomenon implicated in cardiovascular morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients. While it has been demonstrated that CPAP improves endothelial function, our understanding of the pathophysiologic links between CPAP therapy and cardiovascular outcomes remain limited,” researchers wrote in the study’s abstract.

The researchers examined 18 patients’ endothelial function before and after using CPAP therapy for a median of 37 days, along with the relationship between endothelial function and aspirin responsiveness in these same patients. All study participants had been recently diagnosed with moderate to severe OSA and underwent modified peripheral artery tonometry and platelet aggregometry before and after beginning CPAP therapy. Most of the patients (14) demonstrated aspirin resistance at baseline.

Endothelial dysfunction was defined as having a reactive hyperemia index (RHI) of less than or equal to 1.67, while aspirin resistance was defined as having a reading of at least 550 aspirin reaction units (ARU).

At baseline, the average RHI of patients was 1.79 (standard deviation = 0.3), with 8 of the patients having had endothelial dysfunction. Following CPAP use, patients’ mean RHI increased to 1.94 (SD = 0.36), and endothelial dysfunction was present in just 5 of the study participants.*

After using CPAP, those patients with endothelial dysfunction at baseline were responsive to aspirin, with their average ARU reading at 520 following therapy. In contrast, those patients with normal endothelial function at baseline remained resistant to aspirin following CPAP use, based on mean ARU values before and after therapy.

Lirim Krveshi, DO, of Danbury (Conn.) Hospital, is scheduled to present this study, “A Prospective Cohort Study of Endothelial Function and its Relationship to Aspirin Responsiveness in OSA Patients,” on Sunday, Oct. 29, at 1:45 p.m. in Convention Center, room 601A. This presentation is part of the Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Insights & Management session, running from 1:30 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.

The study’s authors reported no conflicts of interest.

*This article was updated Oct. 27, 2017.

Obstructive sleep apnea patients with endothelial dysfunction gained aspirin responsiveness after using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, according to the findings from a small study scheduled to be presented at CHEST 2017.

“Endothelial dysfunction is an important phenomenon implicated in cardiovascular morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients. While it has been demonstrated that CPAP improves endothelial function, our understanding of the pathophysiologic links between CPAP therapy and cardiovascular outcomes remain limited,” researchers wrote in the study’s abstract.

The researchers examined 18 patients’ endothelial function before and after using CPAP therapy for a median of 37 days, along with the relationship between endothelial function and aspirin responsiveness in these same patients. All study participants had been recently diagnosed with moderate to severe OSA and underwent modified peripheral artery tonometry and platelet aggregometry before and after beginning CPAP therapy. Most of the patients (14) demonstrated aspirin resistance at baseline.

Endothelial dysfunction was defined as having a reactive hyperemia index (RHI) of less than or equal to 1.67, while aspirin resistance was defined as having a reading of at least 550 aspirin reaction units (ARU).

At baseline, the average RHI of patients was 1.79 (standard deviation = 0.3), with 8 of the patients having had endothelial dysfunction. Following CPAP use, patients’ mean RHI increased to 1.94 (SD = 0.36), and endothelial dysfunction was present in just 5 of the study participants.*

After using CPAP, those patients with endothelial dysfunction at baseline were responsive to aspirin, with their average ARU reading at 520 following therapy. In contrast, those patients with normal endothelial function at baseline remained resistant to aspirin following CPAP use, based on mean ARU values before and after therapy.

Lirim Krveshi, DO, of Danbury (Conn.) Hospital, is scheduled to present this study, “A Prospective Cohort Study of Endothelial Function and its Relationship to Aspirin Responsiveness in OSA Patients,” on Sunday, Oct. 29, at 1:45 p.m. in Convention Center, room 601A. This presentation is part of the Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Insights & Management session, running from 1:30 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.

The study’s authors reported no conflicts of interest.

*This article was updated Oct. 27, 2017.

FROM CHEST 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The average aspirin reaction units reading for patients who had endothelial dysfunction at baseline was 520 following therapy.

Data source: A prospective cohort study of 18 patients with newly diagnosed moderate to severe OSA.

Disclosures: The study’s authors reported no conflicts of interest.

CHEST Physician’s planned coverage of CHEST 2017

CHEST Physician is providing on-site coverage of the CHEST annual meeting in Toronto from Oct. 29 through Nov. 1.

We are planning to share findings from the latest research on treating COPD, sleep apnea, pulmonary hypertension, severe asthma, and other diseases that are part of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. Any improved methods for managing an ICU and updated recommendations on screening for lung cancer will also be on our radar.

The meeting’s agenda includes presentations of hundreds of study abstracts, and we thought you would be interested in hearing which ones grabbed the attention of some of CHEST Physician’s editorial advisory board members.

Board member Susan L. Millard, MD, FCCP, suggested attendees check out presentations of the following two studies:

- Impact of Race on Quality of Life of Families of Children with Asthma when Asthma Guidelines are Followed: Long-Term Follow-Up

- Results Of A Phase 3, Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial of Remimazolam: A New Ultra Short Acting Benzodiazepine for Bronchoscopy

The first study is part of a session entitled Pediatrics, scheduled to run from 3:15 to 4:15 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 29, in Convention Center - 606. Shahid Sheikh, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in New Albany, Ohio, is scheduled to present the abstract at 4:00 p.m.

Dr. Millard, who is Therapeutic Development Network director for the Pediatric CF Care Center and director of research for pediatric pulmonary and sleep medicine at the Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., noted that she is interested in Dr. Sheikh’s research, “because cultural diversity is such a hot topic in general.”

Her other recommendation is part of the Late Breaking Abstracts 2 session, scheduled to occur on Wednesday, Nov. 1, from 2:45 to 4:15 p.m. in Convention Center - 603. CHEST President, Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP, will present the abstract at 4:00 p.m.

Dr. Millard said she is interested in this study, because new drug options are so helpful for the frequently performed bronchoscopy.

Two sleep medicine experts on CHEST Physician’s editorial advisory board also selected a few presentations they expect to be newsworthy.

David Schulman, MD, MPH, FCCP, and professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta suggested CHEST Physician cover the following studies:

- Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, 12-Week, Multicenter Study of JZP-110 for the Treatment Of Excessive Sleepiness in Patients with OSA, scheduled to be presented on Sunday, Oct. 29, at 1:30 p.m. in Convention Center - 601A. Dr. Kingman Strohl, MD, FCCP, of University Hospitals Case Medical Center-Sleep Center in Shaker Heights, Ohio, will present this research during a session entitled, Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Insights & Management, running from 1:30 to 3:00 p.m.

- History of Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease may Portend Improved Mortality in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke, scheduled to be presented on Tuesday, Oct. 31, at 11:15 a.m., in Convention Center - 601A. Nura Festic will present this research during the session, “Sleep, Heart, Brain and More,” running from 11:00 a.m. to 12:15 p.m.

- Ischemic Preconditioning in OSA Patients Manifested after Surviving a Cardiac Arrest? John Moss, MD, of Jacksonville, Fla., will present this study on Tuesday, Oct. 31, at 11:30 a.m., in Convention Center - 601A as part of the session “Sleep, Heart, Brain and More.”

Krishna M. Sundar, MD, FCCP, also recommended that CHEST Physician cover “A Prospective Cohort Study of Endothelial Function and its Relationship to Aspirin Responsiveness in OSA Patients.” Lirim Krveshi is scheduled to present this study on Sunday, Oct. 29, at 1:45 p.m. in Convention Center - 601A. This presentation is part of the Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Insights & Management session.

Dr. Sundar is an associate clinical professor of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine and medical director of the Sleep-Wake Center at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

To view the full agenda of the CHEST annual meeting, visit: chestmeeting.chestnet.org.

Look for CHEST Physician’s coverage of CHEST 2017 on our conference coverage page.

CHEST Physician is providing on-site coverage of the CHEST annual meeting in Toronto from Oct. 29 through Nov. 1.

We are planning to share findings from the latest research on treating COPD, sleep apnea, pulmonary hypertension, severe asthma, and other diseases that are part of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. Any improved methods for managing an ICU and updated recommendations on screening for lung cancer will also be on our radar.

The meeting’s agenda includes presentations of hundreds of study abstracts, and we thought you would be interested in hearing which ones grabbed the attention of some of CHEST Physician’s editorial advisory board members.

Board member Susan L. Millard, MD, FCCP, suggested attendees check out presentations of the following two studies:

- Impact of Race on Quality of Life of Families of Children with Asthma when Asthma Guidelines are Followed: Long-Term Follow-Up

- Results Of A Phase 3, Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial of Remimazolam: A New Ultra Short Acting Benzodiazepine for Bronchoscopy

The first study is part of a session entitled Pediatrics, scheduled to run from 3:15 to 4:15 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 29, in Convention Center - 606. Shahid Sheikh, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in New Albany, Ohio, is scheduled to present the abstract at 4:00 p.m.

Dr. Millard, who is Therapeutic Development Network director for the Pediatric CF Care Center and director of research for pediatric pulmonary and sleep medicine at the Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., noted that she is interested in Dr. Sheikh’s research, “because cultural diversity is such a hot topic in general.”

Her other recommendation is part of the Late Breaking Abstracts 2 session, scheduled to occur on Wednesday, Nov. 1, from 2:45 to 4:15 p.m. in Convention Center - 603. CHEST President, Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP, will present the abstract at 4:00 p.m.

Dr. Millard said she is interested in this study, because new drug options are so helpful for the frequently performed bronchoscopy.

Two sleep medicine experts on CHEST Physician’s editorial advisory board also selected a few presentations they expect to be newsworthy.

David Schulman, MD, MPH, FCCP, and professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta suggested CHEST Physician cover the following studies:

- Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, 12-Week, Multicenter Study of JZP-110 for the Treatment Of Excessive Sleepiness in Patients with OSA, scheduled to be presented on Sunday, Oct. 29, at 1:30 p.m. in Convention Center - 601A. Dr. Kingman Strohl, MD, FCCP, of University Hospitals Case Medical Center-Sleep Center in Shaker Heights, Ohio, will present this research during a session entitled, Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Insights & Management, running from 1:30 to 3:00 p.m.

- History of Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease may Portend Improved Mortality in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke, scheduled to be presented on Tuesday, Oct. 31, at 11:15 a.m., in Convention Center - 601A. Nura Festic will present this research during the session, “Sleep, Heart, Brain and More,” running from 11:00 a.m. to 12:15 p.m.

- Ischemic Preconditioning in OSA Patients Manifested after Surviving a Cardiac Arrest? John Moss, MD, of Jacksonville, Fla., will present this study on Tuesday, Oct. 31, at 11:30 a.m., in Convention Center - 601A as part of the session “Sleep, Heart, Brain and More.”

Krishna M. Sundar, MD, FCCP, also recommended that CHEST Physician cover “A Prospective Cohort Study of Endothelial Function and its Relationship to Aspirin Responsiveness in OSA Patients.” Lirim Krveshi is scheduled to present this study on Sunday, Oct. 29, at 1:45 p.m. in Convention Center - 601A. This presentation is part of the Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Insights & Management session.

Dr. Sundar is an associate clinical professor of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine and medical director of the Sleep-Wake Center at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

To view the full agenda of the CHEST annual meeting, visit: chestmeeting.chestnet.org.

Look for CHEST Physician’s coverage of CHEST 2017 on our conference coverage page.

CHEST Physician is providing on-site coverage of the CHEST annual meeting in Toronto from Oct. 29 through Nov. 1.

We are planning to share findings from the latest research on treating COPD, sleep apnea, pulmonary hypertension, severe asthma, and other diseases that are part of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. Any improved methods for managing an ICU and updated recommendations on screening for lung cancer will also be on our radar.

The meeting’s agenda includes presentations of hundreds of study abstracts, and we thought you would be interested in hearing which ones grabbed the attention of some of CHEST Physician’s editorial advisory board members.

Board member Susan L. Millard, MD, FCCP, suggested attendees check out presentations of the following two studies:

- Impact of Race on Quality of Life of Families of Children with Asthma when Asthma Guidelines are Followed: Long-Term Follow-Up

- Results Of A Phase 3, Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial of Remimazolam: A New Ultra Short Acting Benzodiazepine for Bronchoscopy

The first study is part of a session entitled Pediatrics, scheduled to run from 3:15 to 4:15 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 29, in Convention Center - 606. Shahid Sheikh, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in New Albany, Ohio, is scheduled to present the abstract at 4:00 p.m.

Dr. Millard, who is Therapeutic Development Network director for the Pediatric CF Care Center and director of research for pediatric pulmonary and sleep medicine at the Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., noted that she is interested in Dr. Sheikh’s research, “because cultural diversity is such a hot topic in general.”

Her other recommendation is part of the Late Breaking Abstracts 2 session, scheduled to occur on Wednesday, Nov. 1, from 2:45 to 4:15 p.m. in Convention Center - 603. CHEST President, Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP, will present the abstract at 4:00 p.m.

Dr. Millard said she is interested in this study, because new drug options are so helpful for the frequently performed bronchoscopy.

Two sleep medicine experts on CHEST Physician’s editorial advisory board also selected a few presentations they expect to be newsworthy.

David Schulman, MD, MPH, FCCP, and professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta suggested CHEST Physician cover the following studies:

- Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, 12-Week, Multicenter Study of JZP-110 for the Treatment Of Excessive Sleepiness in Patients with OSA, scheduled to be presented on Sunday, Oct. 29, at 1:30 p.m. in Convention Center - 601A. Dr. Kingman Strohl, MD, FCCP, of University Hospitals Case Medical Center-Sleep Center in Shaker Heights, Ohio, will present this research during a session entitled, Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Insights & Management, running from 1:30 to 3:00 p.m.

- History of Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease may Portend Improved Mortality in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke, scheduled to be presented on Tuesday, Oct. 31, at 11:15 a.m., in Convention Center - 601A. Nura Festic will present this research during the session, “Sleep, Heart, Brain and More,” running from 11:00 a.m. to 12:15 p.m.

- Ischemic Preconditioning in OSA Patients Manifested after Surviving a Cardiac Arrest? John Moss, MD, of Jacksonville, Fla., will present this study on Tuesday, Oct. 31, at 11:30 a.m., in Convention Center - 601A as part of the session “Sleep, Heart, Brain and More.”

Krishna M. Sundar, MD, FCCP, also recommended that CHEST Physician cover “A Prospective Cohort Study of Endothelial Function and its Relationship to Aspirin Responsiveness in OSA Patients.” Lirim Krveshi is scheduled to present this study on Sunday, Oct. 29, at 1:45 p.m. in Convention Center - 601A. This presentation is part of the Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Insights & Management session.

Dr. Sundar is an associate clinical professor of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine and medical director of the Sleep-Wake Center at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

To view the full agenda of the CHEST annual meeting, visit: chestmeeting.chestnet.org.

Look for CHEST Physician’s coverage of CHEST 2017 on our conference coverage page.

FROM CHEST 2017

New test could cause OSA’s treatment success rate to rise

A novel device has shown a high rate of accuracy in predicting which patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) will improve with oral appliance therapy, according to a study.

“At the present time CPAP is our go-to standard medical therapy [for treating OSA]. While it is a wonderful therapy, it has a very serious drawback, which is poor compliance, and that undercuts its long-term effectiveness in reducing the incidence of cardiovascular disease,” said John E. Remmers, MD, the principal investigator, in an interview.

Referring to the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) trial’s finding that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) did not reduce long-term cardiovascular incidents, he claimed that “these incidents are not being reduced by CPAP, because people don’t use it” (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 8;375[10]:919-31).

In Dr. Remmers’ new two-part study, 202 adults – primarily overweight, middle-aged men, diagnosed with moderate sleep apnea – were divided into two groups. The first included 149 people who were given a two-night, in-home, feedback controlled mandibular positioner (FCMP) test, using equipment manufactured by Zephyr Sleep Technologies. In this test, a custom-fit oral appliance is simulated using a temporary set of trays and impression material. The trays are connected to a small motor controlled by a little computer that sits on the stomach and moves the mandible when the patient has a problem breathing.

All patients received a custom oral appliance designed using data acquired from the test. The patients then wore the custom oral appliances while connected to a validated monitor as an outcomes study.

Finally, the researchers fed all of the data they collected from this first group of patients into a machine learning model. Then the second set of patients participated in the testing. Outcomes data on the appliance’s performance in each individual in the first group were used to create a classification system to predict therapeutic outcomes for the 53 patients in the second group. The patients in the second group then received their custom oral appliances, connected to the same type of monitor used by the first group.

Therapeutic success or failure was defined as having mean oxygen desaturation index values of less than or greater than 10 events/hour, respectively. The investigators determined that the test had an 85% sensitivity level with 93% specificity, a positive predictive value of 97%, and a negative predictive value of 72%. Of those who were predicted to respond to therapy, the mandibular protrusive position was efficacious in 86% of patients.

The high rate of accuracy for predicting who will derive the most benefit from the appliance, along with the demonstrated preference for oral appliances compared to continuous positive airway pressure devices among patients, increases the clinical utility of the appliance, and expands options for clinical management of sleep apnea, according to the study authors (Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13[7]:871-80).

“Our test allows the physician to prescribe the therapy knowing it will get rid of sleep apnea, and it tells the dentist how far the mandible needs to be pulled out by the custom fit device,” Dr. Remmers explained.

Dentists will also benefit from the test, because it allows them to make an appliance that will not need to be adjusted and will have a higher success rate than the current 60% success rate that oral appliances have at treating sleep apnea, he noted.

“This opens up a new an alternative clinical avenue at a critical time, when we have just learned over the past few years that there are serious questions about the effectiveness of CPAP in the long term,” Dr. Remmers added. “[With oral appliance therapy] you have an opportunity for higher compliance, because people prefer the less obtrusive oral appliance therapy over CPAP, and they use it more than CPAP. ... Because our product says you don’t treat everybody, you only undertake oral appliance therapy for those who we know in advance will have a favorable outcome, it removes a major barrier to oral appliance therapy that has been the barrier for many years.”

Dr. Remmers noted that his test was not nearly as good at identifying people who would be failures as it was at identifying people who would be successes and that he is carrying out another trial with a similar device.

Some participants reported sore gums when using the device, but there were no long-lasting adverse events reported.

The mandibular positioner home test has not been approved or cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration, but is currently being sold in Canada, according to Dr. Remmers.

Zephyr Sleep Technologies and Alberta Innovates Technology Futures sponsored the study. It is registered on clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03011762. All of the investigators, other than Nikola Vranjes, are employed or associated with Zephyr Sleep Technologies.

Whitney McKnight contributed to this report.

A novel device has shown a high rate of accuracy in predicting which patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) will improve with oral appliance therapy, according to a study.

“At the present time CPAP is our go-to standard medical therapy [for treating OSA]. While it is a wonderful therapy, it has a very serious drawback, which is poor compliance, and that undercuts its long-term effectiveness in reducing the incidence of cardiovascular disease,” said John E. Remmers, MD, the principal investigator, in an interview.

Referring to the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) trial’s finding that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) did not reduce long-term cardiovascular incidents, he claimed that “these incidents are not being reduced by CPAP, because people don’t use it” (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 8;375[10]:919-31).

In Dr. Remmers’ new two-part study, 202 adults – primarily overweight, middle-aged men, diagnosed with moderate sleep apnea – were divided into two groups. The first included 149 people who were given a two-night, in-home, feedback controlled mandibular positioner (FCMP) test, using equipment manufactured by Zephyr Sleep Technologies. In this test, a custom-fit oral appliance is simulated using a temporary set of trays and impression material. The trays are connected to a small motor controlled by a little computer that sits on the stomach and moves the mandible when the patient has a problem breathing.

All patients received a custom oral appliance designed using data acquired from the test. The patients then wore the custom oral appliances while connected to a validated monitor as an outcomes study.

Finally, the researchers fed all of the data they collected from this first group of patients into a machine learning model. Then the second set of patients participated in the testing. Outcomes data on the appliance’s performance in each individual in the first group were used to create a classification system to predict therapeutic outcomes for the 53 patients in the second group. The patients in the second group then received their custom oral appliances, connected to the same type of monitor used by the first group.

Therapeutic success or failure was defined as having mean oxygen desaturation index values of less than or greater than 10 events/hour, respectively. The investigators determined that the test had an 85% sensitivity level with 93% specificity, a positive predictive value of 97%, and a negative predictive value of 72%. Of those who were predicted to respond to therapy, the mandibular protrusive position was efficacious in 86% of patients.

The high rate of accuracy for predicting who will derive the most benefit from the appliance, along with the demonstrated preference for oral appliances compared to continuous positive airway pressure devices among patients, increases the clinical utility of the appliance, and expands options for clinical management of sleep apnea, according to the study authors (Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13[7]:871-80).

“Our test allows the physician to prescribe the therapy knowing it will get rid of sleep apnea, and it tells the dentist how far the mandible needs to be pulled out by the custom fit device,” Dr. Remmers explained.

Dentists will also benefit from the test, because it allows them to make an appliance that will not need to be adjusted and will have a higher success rate than the current 60% success rate that oral appliances have at treating sleep apnea, he noted.

“This opens up a new an alternative clinical avenue at a critical time, when we have just learned over the past few years that there are serious questions about the effectiveness of CPAP in the long term,” Dr. Remmers added. “[With oral appliance therapy] you have an opportunity for higher compliance, because people prefer the less obtrusive oral appliance therapy over CPAP, and they use it more than CPAP. ... Because our product says you don’t treat everybody, you only undertake oral appliance therapy for those who we know in advance will have a favorable outcome, it removes a major barrier to oral appliance therapy that has been the barrier for many years.”

Dr. Remmers noted that his test was not nearly as good at identifying people who would be failures as it was at identifying people who would be successes and that he is carrying out another trial with a similar device.

Some participants reported sore gums when using the device, but there were no long-lasting adverse events reported.

The mandibular positioner home test has not been approved or cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration, but is currently being sold in Canada, according to Dr. Remmers.

Zephyr Sleep Technologies and Alberta Innovates Technology Futures sponsored the study. It is registered on clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03011762. All of the investigators, other than Nikola Vranjes, are employed or associated with Zephyr Sleep Technologies.

Whitney McKnight contributed to this report.

A novel device has shown a high rate of accuracy in predicting which patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) will improve with oral appliance therapy, according to a study.

“At the present time CPAP is our go-to standard medical therapy [for treating OSA]. While it is a wonderful therapy, it has a very serious drawback, which is poor compliance, and that undercuts its long-term effectiveness in reducing the incidence of cardiovascular disease,” said John E. Remmers, MD, the principal investigator, in an interview.

Referring to the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) trial’s finding that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) did not reduce long-term cardiovascular incidents, he claimed that “these incidents are not being reduced by CPAP, because people don’t use it” (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sept 8;375[10]:919-31).

In Dr. Remmers’ new two-part study, 202 adults – primarily overweight, middle-aged men, diagnosed with moderate sleep apnea – were divided into two groups. The first included 149 people who were given a two-night, in-home, feedback controlled mandibular positioner (FCMP) test, using equipment manufactured by Zephyr Sleep Technologies. In this test, a custom-fit oral appliance is simulated using a temporary set of trays and impression material. The trays are connected to a small motor controlled by a little computer that sits on the stomach and moves the mandible when the patient has a problem breathing.

All patients received a custom oral appliance designed using data acquired from the test. The patients then wore the custom oral appliances while connected to a validated monitor as an outcomes study.

Finally, the researchers fed all of the data they collected from this first group of patients into a machine learning model. Then the second set of patients participated in the testing. Outcomes data on the appliance’s performance in each individual in the first group were used to create a classification system to predict therapeutic outcomes for the 53 patients in the second group. The patients in the second group then received their custom oral appliances, connected to the same type of monitor used by the first group.

Therapeutic success or failure was defined as having mean oxygen desaturation index values of less than or greater than 10 events/hour, respectively. The investigators determined that the test had an 85% sensitivity level with 93% specificity, a positive predictive value of 97%, and a negative predictive value of 72%. Of those who were predicted to respond to therapy, the mandibular protrusive position was efficacious in 86% of patients.

The high rate of accuracy for predicting who will derive the most benefit from the appliance, along with the demonstrated preference for oral appliances compared to continuous positive airway pressure devices among patients, increases the clinical utility of the appliance, and expands options for clinical management of sleep apnea, according to the study authors (Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13[7]:871-80).

“Our test allows the physician to prescribe the therapy knowing it will get rid of sleep apnea, and it tells the dentist how far the mandible needs to be pulled out by the custom fit device,” Dr. Remmers explained.

Dentists will also benefit from the test, because it allows them to make an appliance that will not need to be adjusted and will have a higher success rate than the current 60% success rate that oral appliances have at treating sleep apnea, he noted.

“This opens up a new an alternative clinical avenue at a critical time, when we have just learned over the past few years that there are serious questions about the effectiveness of CPAP in the long term,” Dr. Remmers added. “[With oral appliance therapy] you have an opportunity for higher compliance, because people prefer the less obtrusive oral appliance therapy over CPAP, and they use it more than CPAP. ... Because our product says you don’t treat everybody, you only undertake oral appliance therapy for those who we know in advance will have a favorable outcome, it removes a major barrier to oral appliance therapy that has been the barrier for many years.”

Dr. Remmers noted that his test was not nearly as good at identifying people who would be failures as it was at identifying people who would be successes and that he is carrying out another trial with a similar device.

Some participants reported sore gums when using the device, but there were no long-lasting adverse events reported.

The mandibular positioner home test has not been approved or cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration, but is currently being sold in Canada, according to Dr. Remmers.

Zephyr Sleep Technologies and Alberta Innovates Technology Futures sponsored the study. It is registered on clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03011762. All of the investigators, other than Nikola Vranjes, are employed or associated with Zephyr Sleep Technologies.

Whitney McKnight contributed to this report.

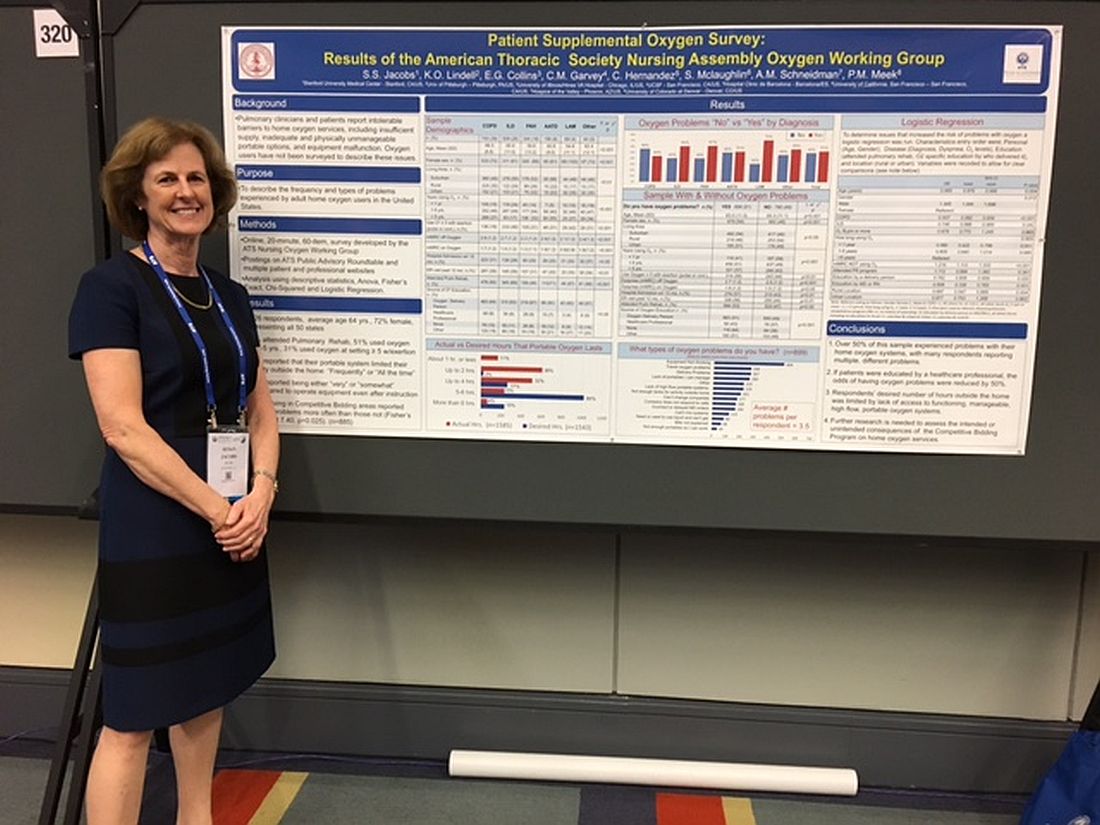

Patients report issues with home O2

WASHINGTON – Patient education in the use of home oxygen halves the number of system use issues reported by patients, based on results of a survey of nearly 2,000 patients.

Pulmonary clinicians and patients report “intolerable barriers to home oxygen services,” lead researcher Susan S. Jacobs, RN, MS, said in a poster session at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. These barriers include insufficient oxygen supply, inadequate and physically unmanageable portable options, and equipment malfunction.

“We’ve demonstrated that, if the patients are educated by a health care professional, the problems with oxygen go down, Ms. Jacobs, who is a nurse coordinator in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “While physicians can provide oxygen for their patients, the patient oxygen education will most likely lie with the nurses and respiratory therapists.”

Of patients who responded to the survey question "Do you have oxygen problems?" 51% (899) said yes*. On average, these patients said they had experienced 3.5 types of problems with their systems.

Patients who were educated by a health care professional reported fewer problems and were more likely to report having no problems with their oxygen system. Of the patients who received oxygen therapy instruction from a health care professional, 76 (57%) did not report having any issues with their system. In contrast, of the patients who received no instruction, 116 (64%) said they had problems with their oxygen.

Most survey participants (1,113 patients) received oxygen therapy instruction from an oxygen delivery person instead of a health care professional. This group’s opinions about their oxygen systems were split, with 51% (563 patients) experiencing issues with their systems. The other 49% reported no problems.

Survey participants most frequently complained that their equipment was not working; 499 selected this response to the question, “What types of oxygen problems do you have?”

Many patients also reported being unable to spend as much time out of their homes as they wanted. This limitation resulted from their lack of access to functioning, manageable, high flow, portable oxygen systems, according to the researchers. Further, 43% of patients reported that their portable system limited their activity outside the home frequently or all of the time.

“Most of the reported problems were related to respondents not having portable systems that let them be out of their house for more than 2 to 4 hours or [to systems that] were too heavy for the patients to lift up and down their stairs and out of their cars, and they had problems operating them,” said Ms. Jacobs, who is a nurse coordinator in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The survey respondents also reported experiencing delivery problems, not being able to change the company providing them with oxygen, receiving incorrect or delayed orders from a physician, or being unable to get liquid oxygen. These responses were provided by 267, 177, 166, and 68 patients, respectively.

“There is a lot of confusion for the physicians as well as the nurses about what types of systems the patients can use [and] the pros and cons of each system. There’s lots of confusion and time spent about getting the initial orders right, getting them set up with a supplier, and ensuring the patient gets the equipment that was ordered. There is a lot of back and forth, which results in a delay to the patient, and the patients are upset because they are waiting for their oxygen supply,” she explained. “So, I think that physicians are very much wanting clarification to streamline the process and identify what patient systems are appropriate, which are high flow, [and] what their patients’ needs are to help physicians spend less time on this and help the patients get their oxygen set up in a timely manner.”

The study participants came from all 50 states and were 64 years of age on average and mostly women. A high percentage (39%) of the sample had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, while 26% had interstitial lung diseases, 18% had pulmonary arterial hypertension, 8% had alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and 4% had lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Ms. Jacobs noted that she thought patients would benefit from greater physician knowledge of their prescribing options.

“A physician can dictate exactly what system they want. ... You can try to give [patients] a lighter system, a backpack, a smaller tank, more tanks per week, depending on their lifestyle and their needs. But physicians, a lot of times, like all of us and our patients, [are] not aware of all these choices,” she said, during the interview.

An online resource providing all of the pros and cons of the different types of portable oxygen systems that would be appropriate for physicians, nurses, and patients, as well as an examination of the quality standards of the oxygen suppliers, are needed, she noted

Ms. Jacobs reported no financial disclosures.

*This article was corrected June 16, 2017

WASHINGTON – Patient education in the use of home oxygen halves the number of system use issues reported by patients, based on results of a survey of nearly 2,000 patients.

Pulmonary clinicians and patients report “intolerable barriers to home oxygen services,” lead researcher Susan S. Jacobs, RN, MS, said in a poster session at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. These barriers include insufficient oxygen supply, inadequate and physically unmanageable portable options, and equipment malfunction.

“We’ve demonstrated that, if the patients are educated by a health care professional, the problems with oxygen go down, Ms. Jacobs, who is a nurse coordinator in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “While physicians can provide oxygen for their patients, the patient oxygen education will most likely lie with the nurses and respiratory therapists.”

Of patients who responded to the survey question "Do you have oxygen problems?" 51% (899) said yes*. On average, these patients said they had experienced 3.5 types of problems with their systems.

Patients who were educated by a health care professional reported fewer problems and were more likely to report having no problems with their oxygen system. Of the patients who received oxygen therapy instruction from a health care professional, 76 (57%) did not report having any issues with their system. In contrast, of the patients who received no instruction, 116 (64%) said they had problems with their oxygen.

Most survey participants (1,113 patients) received oxygen therapy instruction from an oxygen delivery person instead of a health care professional. This group’s opinions about their oxygen systems were split, with 51% (563 patients) experiencing issues with their systems. The other 49% reported no problems.

Survey participants most frequently complained that their equipment was not working; 499 selected this response to the question, “What types of oxygen problems do you have?”

Many patients also reported being unable to spend as much time out of their homes as they wanted. This limitation resulted from their lack of access to functioning, manageable, high flow, portable oxygen systems, according to the researchers. Further, 43% of patients reported that their portable system limited their activity outside the home frequently or all of the time.

“Most of the reported problems were related to respondents not having portable systems that let them be out of their house for more than 2 to 4 hours or [to systems that] were too heavy for the patients to lift up and down their stairs and out of their cars, and they had problems operating them,” said Ms. Jacobs, who is a nurse coordinator in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The survey respondents also reported experiencing delivery problems, not being able to change the company providing them with oxygen, receiving incorrect or delayed orders from a physician, or being unable to get liquid oxygen. These responses were provided by 267, 177, 166, and 68 patients, respectively.

“There is a lot of confusion for the physicians as well as the nurses about what types of systems the patients can use [and] the pros and cons of each system. There’s lots of confusion and time spent about getting the initial orders right, getting them set up with a supplier, and ensuring the patient gets the equipment that was ordered. There is a lot of back and forth, which results in a delay to the patient, and the patients are upset because they are waiting for their oxygen supply,” she explained. “So, I think that physicians are very much wanting clarification to streamline the process and identify what patient systems are appropriate, which are high flow, [and] what their patients’ needs are to help physicians spend less time on this and help the patients get their oxygen set up in a timely manner.”

The study participants came from all 50 states and were 64 years of age on average and mostly women. A high percentage (39%) of the sample had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, while 26% had interstitial lung diseases, 18% had pulmonary arterial hypertension, 8% had alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and 4% had lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Ms. Jacobs noted that she thought patients would benefit from greater physician knowledge of their prescribing options.

“A physician can dictate exactly what system they want. ... You can try to give [patients] a lighter system, a backpack, a smaller tank, more tanks per week, depending on their lifestyle and their needs. But physicians, a lot of times, like all of us and our patients, [are] not aware of all these choices,” she said, during the interview.

An online resource providing all of the pros and cons of the different types of portable oxygen systems that would be appropriate for physicians, nurses, and patients, as well as an examination of the quality standards of the oxygen suppliers, are needed, she noted

Ms. Jacobs reported no financial disclosures.

*This article was corrected June 16, 2017

WASHINGTON – Patient education in the use of home oxygen halves the number of system use issues reported by patients, based on results of a survey of nearly 2,000 patients.

Pulmonary clinicians and patients report “intolerable barriers to home oxygen services,” lead researcher Susan S. Jacobs, RN, MS, said in a poster session at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. These barriers include insufficient oxygen supply, inadequate and physically unmanageable portable options, and equipment malfunction.

“We’ve demonstrated that, if the patients are educated by a health care professional, the problems with oxygen go down, Ms. Jacobs, who is a nurse coordinator in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “While physicians can provide oxygen for their patients, the patient oxygen education will most likely lie with the nurses and respiratory therapists.”

Of patients who responded to the survey question "Do you have oxygen problems?" 51% (899) said yes*. On average, these patients said they had experienced 3.5 types of problems with their systems.

Patients who were educated by a health care professional reported fewer problems and were more likely to report having no problems with their oxygen system. Of the patients who received oxygen therapy instruction from a health care professional, 76 (57%) did not report having any issues with their system. In contrast, of the patients who received no instruction, 116 (64%) said they had problems with their oxygen.

Most survey participants (1,113 patients) received oxygen therapy instruction from an oxygen delivery person instead of a health care professional. This group’s opinions about their oxygen systems were split, with 51% (563 patients) experiencing issues with their systems. The other 49% reported no problems.

Survey participants most frequently complained that their equipment was not working; 499 selected this response to the question, “What types of oxygen problems do you have?”

Many patients also reported being unable to spend as much time out of their homes as they wanted. This limitation resulted from their lack of access to functioning, manageable, high flow, portable oxygen systems, according to the researchers. Further, 43% of patients reported that their portable system limited their activity outside the home frequently or all of the time.

“Most of the reported problems were related to respondents not having portable systems that let them be out of their house for more than 2 to 4 hours or [to systems that] were too heavy for the patients to lift up and down their stairs and out of their cars, and they had problems operating them,” said Ms. Jacobs, who is a nurse coordinator in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The survey respondents also reported experiencing delivery problems, not being able to change the company providing them with oxygen, receiving incorrect or delayed orders from a physician, or being unable to get liquid oxygen. These responses were provided by 267, 177, 166, and 68 patients, respectively.

“There is a lot of confusion for the physicians as well as the nurses about what types of systems the patients can use [and] the pros and cons of each system. There’s lots of confusion and time spent about getting the initial orders right, getting them set up with a supplier, and ensuring the patient gets the equipment that was ordered. There is a lot of back and forth, which results in a delay to the patient, and the patients are upset because they are waiting for their oxygen supply,” she explained. “So, I think that physicians are very much wanting clarification to streamline the process and identify what patient systems are appropriate, which are high flow, [and] what their patients’ needs are to help physicians spend less time on this and help the patients get their oxygen set up in a timely manner.”

The study participants came from all 50 states and were 64 years of age on average and mostly women. A high percentage (39%) of the sample had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, while 26% had interstitial lung diseases, 18% had pulmonary arterial hypertension, 8% had alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and 4% had lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Ms. Jacobs noted that she thought patients would benefit from greater physician knowledge of their prescribing options.

“A physician can dictate exactly what system they want. ... You can try to give [patients] a lighter system, a backpack, a smaller tank, more tanks per week, depending on their lifestyle and their needs. But physicians, a lot of times, like all of us and our patients, [are] not aware of all these choices,” she said, during the interview.

An online resource providing all of the pros and cons of the different types of portable oxygen systems that would be appropriate for physicians, nurses, and patients, as well as an examination of the quality standards of the oxygen suppliers, are needed, she noted

Ms. Jacobs reported no financial disclosures.

*This article was corrected June 16, 2017

AT ATS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients reported experiencing an average of 3.5 types of problems with their home oxygen systems.

Data source: An analysis of 1,926 home-oxygen users’ responses to an online, 60-question survey.

Disclosures: Ms. Jacobs reported no financial disclosures.

NIH releases COPD National Action Plan

WASHINGTON – The National Institutes of Health on Monday released its first COPD National Action Plan, a five-point initiative to reduce the burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and increase research into prevention and treatment.

On the same day, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and other supporters of the plan described its evolution and why they thought the plan’s implementation was important.

The plan’s five goals are:

- Empower people with COPD, their families, and caregivers to recognize and reduce the burden of COPD.

- Improve the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and management of COPD by increasing the quality of care delivered across the health care continuum.

- Collect, analyze, report, and disseminate COPD-related public health data that drive change and track progress.

- Increase and sustain research to better understand the prevention, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and management of COPD.

- Translate national policy, educational, and program recommendations into research and public health care actions.

“Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is the third-leading cause of death in this country; it’s just behind heart disease and cancer,” Dr. Kiley noted. “What’s really disappointing and discouraging is it’s the only cause of death in this country where the numbers are not declining.”

COPD “got the attention of Congress a number of years ago,” he added. “They encouraged the National Institutes of Health to work with the community stakeholders and other federal agencies to develop a national action plan to respond to the growing burden of this disease.”

COPD’s stakeholder community, the federal government, and other partners worked together to develop a set of core goals that the National Action Plan would address, Dr. Kiley continued. “It was meant to obtain the broadest amount of input possible so that we could get it right from the start.”

Another of the plan’s advocates, MeiLan Han, MD, medical director of the women’s respiratory health program at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, illustrated the need to increase and sustain COPD research related to the disease.

[polldaddy:9806142]

“I see the suffering and disease toll that this takes on my patients, and I can’t convince you enough of the level of frustration that I have as a physician in not being able to provide the level of care that I want to be able to provide,” said Dr. Han, who served as a panelist at the press conference.

“We face some serious barriers to being able to provide adequate care for patients,” she added. Those barriers include lack of access to providers who are knowledgeable about COPD, as well as lack of access to affordable and conveniently located pulmonology rehabilitation and education materials. From a research standpoint, Dr. Han added, medicine still doesn’t know enough about the disease. “We certainly have good treatments, but we need better treatments,” she said.

“What’s clear is that we as society can no longer afford to brush this under the table and ignore this problem,” Dr. Han added.

The National Action Plan and information about how to get involved are available at copd.nih.gov.

WASHINGTON – The National Institutes of Health on Monday released its first COPD National Action Plan, a five-point initiative to reduce the burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and increase research into prevention and treatment.

On the same day, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and other supporters of the plan described its evolution and why they thought the plan’s implementation was important.

The plan’s five goals are:

- Empower people with COPD, their families, and caregivers to recognize and reduce the burden of COPD.

- Improve the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and management of COPD by increasing the quality of care delivered across the health care continuum.

- Collect, analyze, report, and disseminate COPD-related public health data that drive change and track progress.

- Increase and sustain research to better understand the prevention, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and management of COPD.

- Translate national policy, educational, and program recommendations into research and public health care actions.

“Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is the third-leading cause of death in this country; it’s just behind heart disease and cancer,” Dr. Kiley noted. “What’s really disappointing and discouraging is it’s the only cause of death in this country where the numbers are not declining.”

COPD “got the attention of Congress a number of years ago,” he added. “They encouraged the National Institutes of Health to work with the community stakeholders and other federal agencies to develop a national action plan to respond to the growing burden of this disease.”

COPD’s stakeholder community, the federal government, and other partners worked together to develop a set of core goals that the National Action Plan would address, Dr. Kiley continued. “It was meant to obtain the broadest amount of input possible so that we could get it right from the start.”

Another of the plan’s advocates, MeiLan Han, MD, medical director of the women’s respiratory health program at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, illustrated the need to increase and sustain COPD research related to the disease.

[polldaddy:9806142]

“I see the suffering and disease toll that this takes on my patients, and I can’t convince you enough of the level of frustration that I have as a physician in not being able to provide the level of care that I want to be able to provide,” said Dr. Han, who served as a panelist at the press conference.

“We face some serious barriers to being able to provide adequate care for patients,” she added. Those barriers include lack of access to providers who are knowledgeable about COPD, as well as lack of access to affordable and conveniently located pulmonology rehabilitation and education materials. From a research standpoint, Dr. Han added, medicine still doesn’t know enough about the disease. “We certainly have good treatments, but we need better treatments,” she said.

“What’s clear is that we as society can no longer afford to brush this under the table and ignore this problem,” Dr. Han added.

The National Action Plan and information about how to get involved are available at copd.nih.gov.

WASHINGTON – The National Institutes of Health on Monday released its first COPD National Action Plan, a five-point initiative to reduce the burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and increase research into prevention and treatment.

On the same day, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and other supporters of the plan described its evolution and why they thought the plan’s implementation was important.

The plan’s five goals are:

- Empower people with COPD, their families, and caregivers to recognize and reduce the burden of COPD.

- Improve the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and management of COPD by increasing the quality of care delivered across the health care continuum.

- Collect, analyze, report, and disseminate COPD-related public health data that drive change and track progress.

- Increase and sustain research to better understand the prevention, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and management of COPD.

- Translate national policy, educational, and program recommendations into research and public health care actions.

“Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is the third-leading cause of death in this country; it’s just behind heart disease and cancer,” Dr. Kiley noted. “What’s really disappointing and discouraging is it’s the only cause of death in this country where the numbers are not declining.”

COPD “got the attention of Congress a number of years ago,” he added. “They encouraged the National Institutes of Health to work with the community stakeholders and other federal agencies to develop a national action plan to respond to the growing burden of this disease.”

COPD’s stakeholder community, the federal government, and other partners worked together to develop a set of core goals that the National Action Plan would address, Dr. Kiley continued. “It was meant to obtain the broadest amount of input possible so that we could get it right from the start.”

Another of the plan’s advocates, MeiLan Han, MD, medical director of the women’s respiratory health program at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, illustrated the need to increase and sustain COPD research related to the disease.

[polldaddy:9806142]

“I see the suffering and disease toll that this takes on my patients, and I can’t convince you enough of the level of frustration that I have as a physician in not being able to provide the level of care that I want to be able to provide,” said Dr. Han, who served as a panelist at the press conference.

“We face some serious barriers to being able to provide adequate care for patients,” she added. Those barriers include lack of access to providers who are knowledgeable about COPD, as well as lack of access to affordable and conveniently located pulmonology rehabilitation and education materials. From a research standpoint, Dr. Han added, medicine still doesn’t know enough about the disease. “We certainly have good treatments, but we need better treatments,” she said.

“What’s clear is that we as society can no longer afford to brush this under the table and ignore this problem,” Dr. Han added.

The National Action Plan and information about how to get involved are available at copd.nih.gov.

AT ATS 2017

App may improve CPAP adherence

Use of a mobile app may help sleep apnea patients adhere to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, a small study suggests.

The app – SleepMapper (SM) – has interactive algorithms that are modeled on the same theories of behavior change that have improved adherence to CPAP when delivered in person or through telephone-linked communication, wrote Jordanna M. Hostler of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., and her coinvestigators (J Sleep Res. 2017;26:139-46).

“Despite our small sample size, patients in the SM group were more than three times as likely to meet Medicare criteria for [CPAP] adherence (greater than 4 hours per night for 70% of nights), a trend that just missed statistical significance (P = .06),” the researchers noted.

“The magnitude of the increase [in CPAP use] indicates likely clinical benefit,” they added.

SleepMapper allows patients to self-monitor the outcomes of positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy by providing information on their adherence, Apnea-Hypopnea Index, and mask leak. The app, which can be downloaded on a smartphone or personal computer, also includes training modules on how to use PAP. The system, owned by Phillips Respironics, will sync with Philips Respironics’ Encore Anywhere software program.

The study comprised 61 patients who had been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) via overnight, in-lab polysomnography. The patients were initiating PAP for the first time at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center’s Sleep Disorders Center in Bethesda, Md., as participants in the center’s program. Such a program included group sessions with instruction on sleep hygiene and training in the use of PAP, an initial one-on-one meeting with a physician, and a follow-up appointment with a physician 4 weeks after initiating the therapy.

Thirty of the program participants included in the study used SleepMapper in addition to the center’s standard education and follow-up. The researchers analyzed 11 weeks of data for all 61 study participants.

Patients in the SleepMapper group used their PAP machines for a greater percentage of days and achieved more than 4 hours of use on more days of participation in the program, compared with patients who did not use the app. The patients using the app also showed a trend toward using PAP for more hours per night overall. Specifically, nine of the patients in the app group used their PAP machines greater than 4 hours per night for 70% of nights, versus three of the patients in the control group (P = .06). SleepMapper usage remained significantly associated with percentage of nights including greater than 4 hours of PAP use, in a multivariate linear regression analysis.

The researchers observed many similarities between patients using the app and patients in the control group, including Apnea-Hypopnea Index scores, central apnea index scores, and percentages of time spent in periodic breathing.

Some additional advantages to use of SleepMapper over simply participating in the center’s educational program are that the app provides ongoing coaching and immediate access to Apnea-Hypopnea Index and PAP use data, according to the researchers. They touted the app’s educational videos about OSA and PAP therapy and “structured motivational enhancement techniques such as feedback and goal setting, which have shown benefit when delivered by health care professionals in other studies.”

The researchers called for an additional study of the app’s usefulness in a larger group of patients.

The authors did not receive any funding or support for this study.

Feedback to patients regarding their clinical status is rarely a bad thing. I’m a big fan of tools that give patients information on their CPAP adherence and outcomes, of which several now exist, including some that are not affiliated with any particular respiratory device company, and are able to read a number of different device downloads.

In the end, the use of technology for monitoring CPAP adherence is here to stay, and the incremental cost of making it available to our patients is low. Taking the time to educate patients who are newly prescribed CPAP about interpreting their outcome data is likely to be time well spent.

Feedback to patients regarding their clinical status is rarely a bad thing. I’m a big fan of tools that give patients information on their CPAP adherence and outcomes, of which several now exist, including some that are not affiliated with any particular respiratory device company, and are able to read a number of different device downloads.

In the end, the use of technology for monitoring CPAP adherence is here to stay, and the incremental cost of making it available to our patients is low. Taking the time to educate patients who are newly prescribed CPAP about interpreting their outcome data is likely to be time well spent.

Feedback to patients regarding their clinical status is rarely a bad thing. I’m a big fan of tools that give patients information on their CPAP adherence and outcomes, of which several now exist, including some that are not affiliated with any particular respiratory device company, and are able to read a number of different device downloads.

In the end, the use of technology for monitoring CPAP adherence is here to stay, and the incremental cost of making it available to our patients is low. Taking the time to educate patients who are newly prescribed CPAP about interpreting their outcome data is likely to be time well spent.

Use of a mobile app may help sleep apnea patients adhere to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, a small study suggests.

The app – SleepMapper (SM) – has interactive algorithms that are modeled on the same theories of behavior change that have improved adherence to CPAP when delivered in person or through telephone-linked communication, wrote Jordanna M. Hostler of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., and her coinvestigators (J Sleep Res. 2017;26:139-46).

“Despite our small sample size, patients in the SM group were more than three times as likely to meet Medicare criteria for [CPAP] adherence (greater than 4 hours per night for 70% of nights), a trend that just missed statistical significance (P = .06),” the researchers noted.

“The magnitude of the increase [in CPAP use] indicates likely clinical benefit,” they added.

SleepMapper allows patients to self-monitor the outcomes of positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy by providing information on their adherence, Apnea-Hypopnea Index, and mask leak. The app, which can be downloaded on a smartphone or personal computer, also includes training modules on how to use PAP. The system, owned by Phillips Respironics, will sync with Philips Respironics’ Encore Anywhere software program.

The study comprised 61 patients who had been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) via overnight, in-lab polysomnography. The patients were initiating PAP for the first time at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center’s Sleep Disorders Center in Bethesda, Md., as participants in the center’s program. Such a program included group sessions with instruction on sleep hygiene and training in the use of PAP, an initial one-on-one meeting with a physician, and a follow-up appointment with a physician 4 weeks after initiating the therapy.

Thirty of the program participants included in the study used SleepMapper in addition to the center’s standard education and follow-up. The researchers analyzed 11 weeks of data for all 61 study participants.

Patients in the SleepMapper group used their PAP machines for a greater percentage of days and achieved more than 4 hours of use on more days of participation in the program, compared with patients who did not use the app. The patients using the app also showed a trend toward using PAP for more hours per night overall. Specifically, nine of the patients in the app group used their PAP machines greater than 4 hours per night for 70% of nights, versus three of the patients in the control group (P = .06). SleepMapper usage remained significantly associated with percentage of nights including greater than 4 hours of PAP use, in a multivariate linear regression analysis.

The researchers observed many similarities between patients using the app and patients in the control group, including Apnea-Hypopnea Index scores, central apnea index scores, and percentages of time spent in periodic breathing.

Some additional advantages to use of SleepMapper over simply participating in the center’s educational program are that the app provides ongoing coaching and immediate access to Apnea-Hypopnea Index and PAP use data, according to the researchers. They touted the app’s educational videos about OSA and PAP therapy and “structured motivational enhancement techniques such as feedback and goal setting, which have shown benefit when delivered by health care professionals in other studies.”

The researchers called for an additional study of the app’s usefulness in a larger group of patients.

The authors did not receive any funding or support for this study.

Use of a mobile app may help sleep apnea patients adhere to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, a small study suggests.

The app – SleepMapper (SM) – has interactive algorithms that are modeled on the same theories of behavior change that have improved adherence to CPAP when delivered in person or through telephone-linked communication, wrote Jordanna M. Hostler of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., and her coinvestigators (J Sleep Res. 2017;26:139-46).

“Despite our small sample size, patients in the SM group were more than three times as likely to meet Medicare criteria for [CPAP] adherence (greater than 4 hours per night for 70% of nights), a trend that just missed statistical significance (P = .06),” the researchers noted.

“The magnitude of the increase [in CPAP use] indicates likely clinical benefit,” they added.

SleepMapper allows patients to self-monitor the outcomes of positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy by providing information on their adherence, Apnea-Hypopnea Index, and mask leak. The app, which can be downloaded on a smartphone or personal computer, also includes training modules on how to use PAP. The system, owned by Phillips Respironics, will sync with Philips Respironics’ Encore Anywhere software program.

The study comprised 61 patients who had been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) via overnight, in-lab polysomnography. The patients were initiating PAP for the first time at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center’s Sleep Disorders Center in Bethesda, Md., as participants in the center’s program. Such a program included group sessions with instruction on sleep hygiene and training in the use of PAP, an initial one-on-one meeting with a physician, and a follow-up appointment with a physician 4 weeks after initiating the therapy.

Thirty of the program participants included in the study used SleepMapper in addition to the center’s standard education and follow-up. The researchers analyzed 11 weeks of data for all 61 study participants.

Patients in the SleepMapper group used their PAP machines for a greater percentage of days and achieved more than 4 hours of use on more days of participation in the program, compared with patients who did not use the app. The patients using the app also showed a trend toward using PAP for more hours per night overall. Specifically, nine of the patients in the app group used their PAP machines greater than 4 hours per night for 70% of nights, versus three of the patients in the control group (P = .06). SleepMapper usage remained significantly associated with percentage of nights including greater than 4 hours of PAP use, in a multivariate linear regression analysis.

The researchers observed many similarities between patients using the app and patients in the control group, including Apnea-Hypopnea Index scores, central apnea index scores, and percentages of time spent in periodic breathing.

Some additional advantages to use of SleepMapper over simply participating in the center’s educational program are that the app provides ongoing coaching and immediate access to Apnea-Hypopnea Index and PAP use data, according to the researchers. They touted the app’s educational videos about OSA and PAP therapy and “structured motivational enhancement techniques such as feedback and goal setting, which have shown benefit when delivered by health care professionals in other studies.”

The researchers called for an additional study of the app’s usefulness in a larger group of patients.

The authors did not receive any funding or support for this study.

CHEST names Stephen J. Welch as EVP and CEO

The Board of Regents of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) has finalized the appointment of Stephen J. Welch as executive vice president and chief executive officer.

“We appreciate the exceptional performance of Steve, his senior team, and the entire CHEST staff during this transition in executive leadership. We are excited about the opportunity to work with Steve in his new role going forward, as we begin outlining CHEST’s strategic plan for the next 5 years,” said CHEST President Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP, in a statement.

The Board of Regents of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) has finalized the appointment of Stephen J. Welch as executive vice president and chief executive officer.

“We appreciate the exceptional performance of Steve, his senior team, and the entire CHEST staff during this transition in executive leadership. We are excited about the opportunity to work with Steve in his new role going forward, as we begin outlining CHEST’s strategic plan for the next 5 years,” said CHEST President Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP, in a statement.

The Board of Regents of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) has finalized the appointment of Stephen J. Welch as executive vice president and chief executive officer.

“We appreciate the exceptional performance of Steve, his senior team, and the entire CHEST staff during this transition in executive leadership. We are excited about the opportunity to work with Steve in his new role going forward, as we begin outlining CHEST’s strategic plan for the next 5 years,” said CHEST President Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP, in a statement.

Children with poor lung function develop ACOS