User login

Patient Satisfaction Variance Prediction

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandates that government payments to hospitals and physicians must depend, in part, on metrics that assess the quality and efficiency of healthcare being provided to encourage value‐based healthcare.[1] Value in healthcare is defined by the delivery of high‐quality care at low cost.[2, 3] To this end, Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing (HVBP) and Physician Value‐Based Payment Modifier programs have been developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). HVBP is currently being phased in and affects CMS payments for fiscal year (FY) 2013 for over 3000 hospitals across the United States to incentivize healthcare delivery value. The final phase of implementation will be in FY 2017 and will then affect 2% of all CMS hospital reimbursement. HVBP is based on objective measures of hospital performance as well as a subjective measure of performance captured under the Patient Experience of Care domain. This subjective measure will remain at 30% of the aggregate score until FY 2016, when it will then be 25% the aggregate score moving forward.[4] The program rewards hospitals for both overall achievement and improvement in any domain, so that hospitals have multiple ways to receive financial incentives for providing quality care.[5] Even still, there appears to be a nonrandom pattern of patient satisfaction scores across the country with less favorable scores clustering in densely populated areas.[6]

Value‐Based Purchasing and other incentive‐based programs have been criticized for increasing disparities in healthcare by penalizing larger hospitals (including academic medical centers, safety‐net hospitals, and others that disproportionately serve lower socioeconomic communities) and favoring physician‐based specialty hospitals.[7, 8, 9] Therefore, hospitals that serve indigent and elderly populations may be at a disadvantage.[9, 10] HVBP portends significant economic consequences for the majority of hospitals that rely heavily on Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement, as most hospitals have large revenues but low profit margins.[11] Higher HVBP scores are associated with for profit status, smaller size, and location in certain areas of the United States.[12] Jha et al.[6] described Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores regional geographic variability, but concluded that poor satisfaction was due to poor quality.

The Patient Experience of Care domain quantifies patient satisfaction using the validated HCAHPS survey, which is provided to a random sample of patients continuously throughout the year at 48 hours to 6 weeks after discharge. It is a publically available standardized survey instrument used to measure patients perspectives on hospital care. It assesses the following 8 dimensions: nurse communication, doctor communication, hospital staff responsiveness, pain management, medicine communication, discharge information, hospital cleanliness and quietness, and overall hospital rating, of which the last 2 dimensions each have 2 measures (cleanliness and quietness) and (rating 9 or 10 and definitely recommend) to give a total of 10 distinct measures.

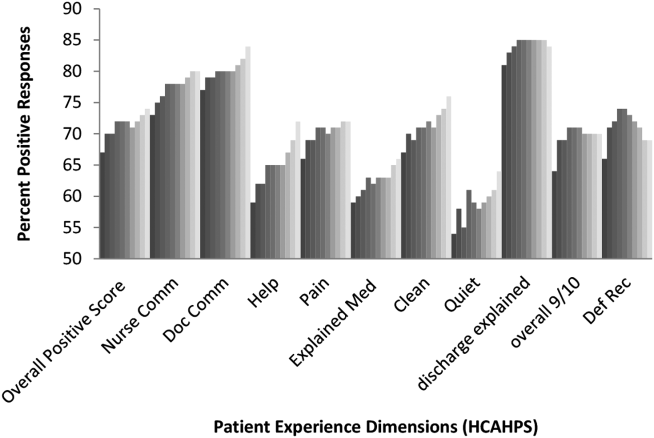

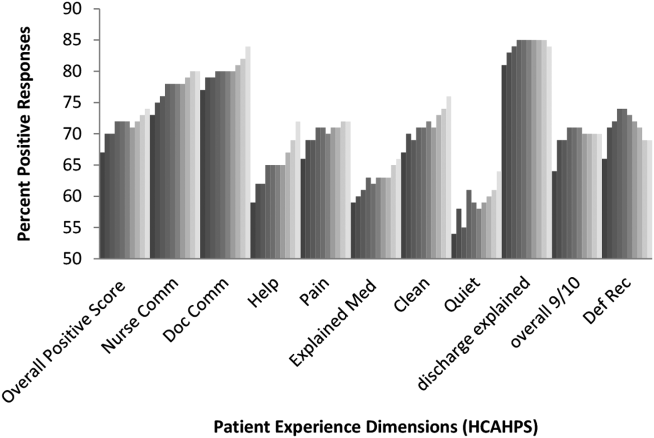

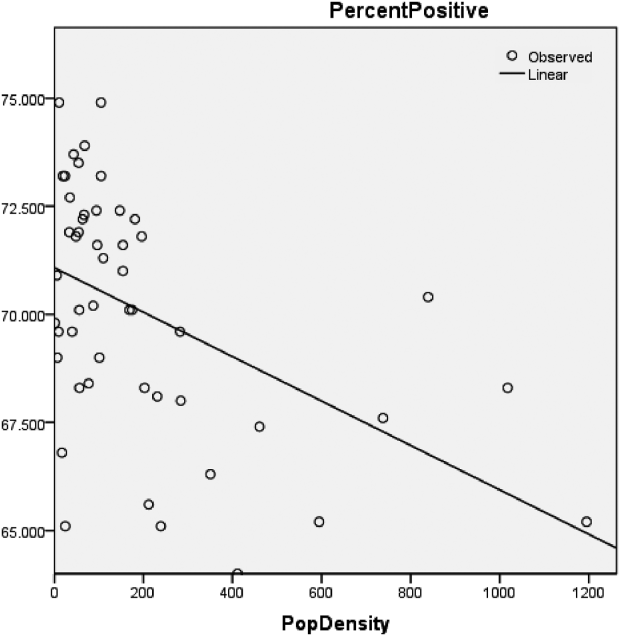

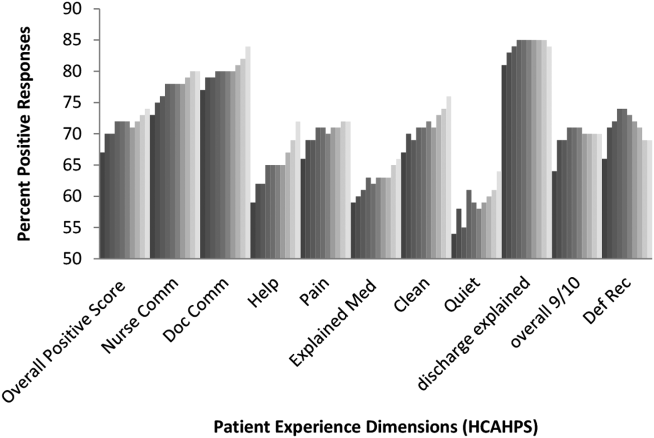

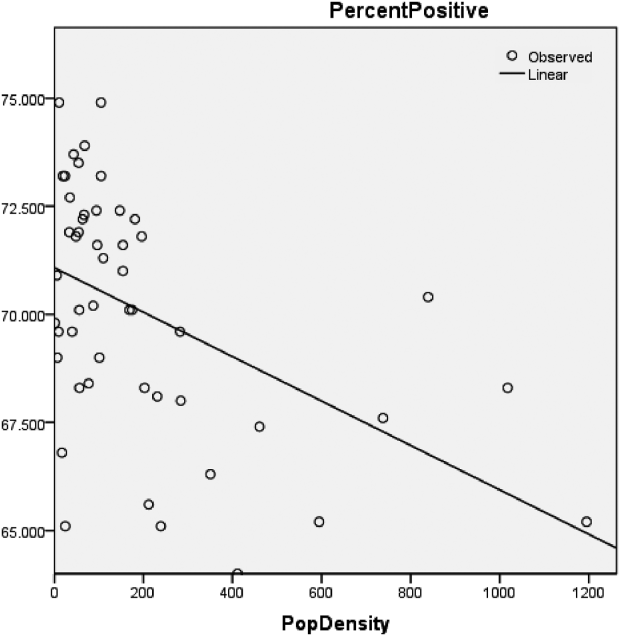

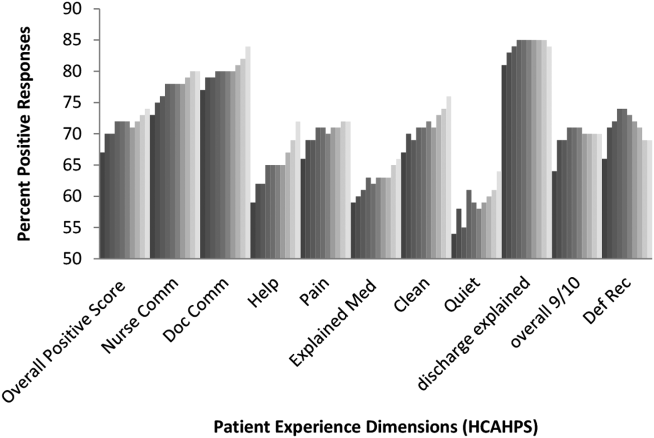

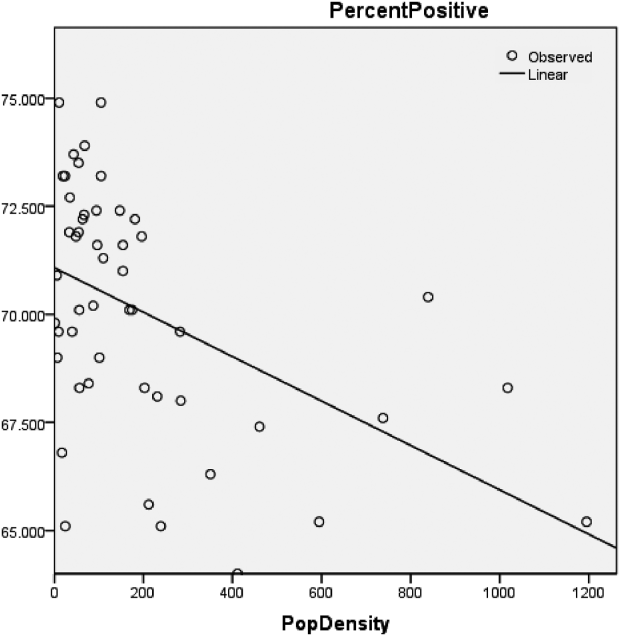

The United States is a complex network of urban, suburban, and rural demographic areas. Hospitals exist within a unique contextual and compositional meshwork that determines its caseload. The top population density decile of the United States lives within 37 counties, whereas half of the most populous parts of the United States occupy a total of 250 counties out of a total of 3143 counties in the United States. If the 10 measures of patient satisfaction (HCAHPS) scores were abstracted from hospitals and viewed according to county‐level population density (separated into deciles across the United States), a trend would be apparent (Figure 1). Greater population density is associated with lower patient satisfaction in 9 of 10 categories. On the state level, composite scores of overall patient satisfaction (amount of positive scores) of hospitals show a 12% variability and a significant correlation with population density (r=0.479; Figure 2). The lowest overall satisfaction scores are obtained from hospitals located in the population‐dense regions of Washington, DC, New York State, California, Maryland, and New Jersey (ie, 63%65%), and the best scores are from Louisiana, South Dakota, Iowa, Maine, and Vermont (ie, 74%75%). The average patient satisfaction score is 71%2.9%. Lower patient satisfaction scores appear to cluster in population‐dense areas and may be associated with greater heterogeneous patient demographics and economic variability in addition to population density.

These observations are surprising considering that CMS already adjusts HCAHPS scores based on patient‐mix coefficients and mode of collection.[13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] Adjustments are updated multiple times per year and account for survey collection either by telephone, email, or paper survey, because the populations that select survey forms will differ. Previous studies have shown that demographic features influence the patient evaluation process. For example, younger and more educated patients were found to provide less positive evaluations of healthcare.[19]

This study examined whether patients perceptions of healthcare (pattern of patient satisfaction) as quantified under the patient experience domain of HVBP were affected and predicted by population density and other demographic factors that are outside the control of individual hospitals. In addition, hospital‐level data (eg, number of hospital beds) and county‐level data such as race, age, gender, overall population, income, time spent commuting to work, primary language, and place of birth were analyzed for correlation with patient satisfaction scores. Our study demonstrates that demographic and hospital‐level data can predict patient satisfaction scores and suggests that CMS may need to modify its adjustment formulas to eliminate bias in HVBP‐based reimbursement.

METHODS

Data Collection

Publically available data were obtained from Hospital Compare,[20] American Hospital Directory,[21] and the US Census Bureau[22] websites. Twenty relevant US Census data categories were selected by their relevance for this study out of the 50 publically reported US Census categories, and included the following: county population, county population density, percent of population change over 1 year, poverty level (percent), income level per capita, median household income, average household size, travel time to work, percentage of high school or college graduates, non‐English primary language spoken at home, percentage of residents born outside of the United States, population percent in same residence for over 1 year, gender, race (white alone, white alone (not Hispanic or Latino), black or African American alone), population over 65 years old, and population under 18 years old.

HCAHPS Development

The HCAHPS survey is 32 questions in length, comprised of 10 evaluative dimensions. All short‐term, acute care, nonspecialty hospitals are invited to participate in the HCAHPS survey.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data were checked for statistical assumptions, including normality, linearity of relationships, and full range of scores. Categories in both the Hospital Compare (HCAHPS) and US Census datasets were analyzed to assess their distribution curves. The category of population densities (per county) was converted to a logarithmic scale to account for a skewed distribution and long tail in the area of low population density. Data were subsequently merged into an Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet using the VLookup function such that relevant 2010 census county data were added to each hospital's Hospital Compare data. Linear regression modeling was performed. Bivariate analysis was conducted (ENTER method) to determine the significant US Census data predictors for each of the 10 Hospital Compare dimensions including the composite overall satisfaction score. Significant predictors were then analyzed in a multivariate model (BACKWORDS method) for each Hospital Compare dimension and the composite average positive score. Models were assessed by determinates of correlation (adjusted R2) to assess for goodness of fit. Statistically significant predictor variables for overall patient satisfaction scores were then ranked according to their partial regression coefficients (standardized ).

A patient satisfaction predictive model was sought based upon significant predictors of aggregate percent positive HCAHPS scores. Various predictor combinations were formed based on their partial coefficients (ie, standardized coefficients); combinations were assessed based on their R2 values and assessed for colinearity. Combinations of partial coefficients included the 2, 4, and 8 most predictive variables as well the 2 most positive and negative predictors. They were then incorporated into a multivariate analysis model (FORWARD method) and assessed based on their adjusted R2 values. A 4‐variable combination (the 2 most predictive positive partial coefficients plus the 2 most predictive negative partial coefficients) was selected as a predictive model, and a formula predictive of the composite overall satisfaction score was generated. This formula (predicted patient satisfaction formula [PPSF]) predicts hospital patient satisfaction HCAHPS scores based on the 4 predictive variables for particular county and hospital characteristics.

| B | SE | t | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Educational attainmentbachelor's degree | 0.157 | 0.018 | 0.27 | 8.612 | <0.001 |

| White alone percent 2012 | 0.09 | 0.012 | 0.235 | 7.587 | <0.001 |

| Resident population percent under 18 years | 0.404 | 0.0444 | 0.209 | 9.085 | <0.001 |

| Black or African American alone percent 2012 | 0.083 | 0.014 | 0.191 | 5.936 | <0.001 |

| Median household income 20072011 | 0.00003 | 0.00 | 0.062 | 2.027 | 0.043 |

| Population density (log) 2010 | 0.277 | 0.083 | 0.087 | 3.3333 | 0.001 |

| Average travel time to work | 0.107 | 0.024 | 0.088 | 4.366 | <0.001 |

| Educational attainmenthigh school | 0.082 | 0.026 | 0.088 | 3.147 | 0.002 |

| Average household size | 2.58 | 0.727 | 0.107 | 3.55 | <0.001 |

| Total females percent 2012 | 0.423 | 0.067 | 0.107 | 6.296 | <0.001 |

| Percent nonEnglish speaking at home 20072011 | 0.052 | 0.018 | 0.14 | 2.929 | 0.003 |

| No. of hospital beds | 0.006 | 0.00 | 0.213 | 12.901 | <0.001 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.222 | ||||

The PPSF was then modified by weighting with the partial coefficient () to remove the bias in patient satisfaction generated by demographic and structural factors over which individual hospitals have limited or no control. This formula generated a Weighted Individual (hospital) Predicted Patient Satisfaction Score (WIPPSS). Application of this formula narrowed the predicted distribution of patient satisfaction for all hospitals across the country.

To create an adjusted score with direct relevance to the reported patient satisfaction scores, the reported scores were multiplied by an adjustment factor that defines the difference between individual hospital‐weighted scores and the national mean HCAHPS score across the United States. This formula, the Weighted Individual (hospital) Patient Satisfaction Adjustment Score (WIPSAS), represents a patient satisfaction score adjusted for demographic and structural factors that can be utilized for interhospital comparisons across all areas of the country.

where PSrep=patient satisfaction reported score, PSUSA=mean reported score for United States (71.84), and WIPPSSX=WIPPSS for individual hospital.

Application of Data Analysis

PPSF, WIPPSS, and WIPSAS were calculated for all HCAHPS‐participating hospitals and compared with averaged raw HCAHPS scores across the United States. WIPSAS and raw scores were specifically analyzed for New York State to demonstrate exactly how adjustments would change state‐level rankings.

RESULTS

Complete HCAHPS scores were obtained from 3907 hospitals out of a total 4621 hospitals listed by the Hospital Compare website (85%). The majority of hospitals (2884) collected over 300 surveys, fewer hospitals (696) collected 100 to 299 surveys, and fewer still (333) collected <100 surveys. In total, results were available from at least 934,800 individual surveys, by the most conservative estimate. Missing HCAHPS hospital data averaged 13.4 (standard deviation [SD] 12.2) hospitals per state. County‐level data were obtained from all 3144 county or county equivalents across the United States (100%). Multivariate regression modeling across all HCAHPS dimensions found that between 10 and 16 of the 20 predictors (US Census categories) were statistically significant and predictive of individual HCAHPS dimension scores and the aggregate percent positive score as demonstrated in Table 2. For example, county percentage of bachelors degrees positively predicts for positive doctor communication scores, and hospital beds negatively predicts for quiet dimension. The strongest positive and negative predictive variables by model regression coefficients for each HCAHPS dimension are also listed in Table 2.

| Average Positive Scores | Nurse Communication | Doctor Communication | Help | Pain | Explain Meds | Clean | Quiet | Discharge Explain | Recommend 9/10 | Definitely Recommend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Educationalbachelor's | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.416 |

| Hospital beds | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| Population density 2010 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.07 | * |

| White alone percent | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.317 | |

| Total females percent | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.09 | |

| African American alone | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.34 | * | 0.09 | 0.084 | |

| Average travel time to work | 0.09 | 0.10 | * | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | * | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Foreign‐born percent | * | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.18 | * | * |

| Average household size | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.07 | * | 0.07 | * | 0.01 | * | 0.07 | 0.076 |

| NonEnglish speaking | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.07 | * | * | * | * | * | 0.34 | 0.28 |

| Educationhigh school | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.40 | * | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.08 | * | |||

| Household income | 0.06 | * | 0.35 | 0.08 | * | * | 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.265 | ||

| Population 65 years and over | * | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 | * | 0.11 | 0.15 | * | 0.10 | ||

| White, not Hispanic/Latino | * | * | 0.20 | * | * | * | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| Population under 18 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.20 | ||||||

| Population (county) | * | 0.06 | 0.08 | * | 0.03 | 0.05 | * | * | 0.06 | * | * |

| All ages in poverty | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.08 | * | 0.281 | |||||

| 1 year at same residence | * | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 | * | 0.04 | * | * | ||

| Per capita income | * | 0.07 | * | * | * | * | * | 0.09 | * | ||

| Population percent change | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0.05 | * | * | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

Table 1 highlights multivariate regression modeling of the composite average positive score, which produced an adjusted R2 of 0.222 (P<0.001). All variables were significant and predicted change of the composite HCAHPS except for place of birthforeign born (not listed in the table). Table 1 ranks variables from most positive to most negative predictors.

Other HCAHPS domains demonstrated statistically significant models (P<0.001) and are listed by their coefficients of determination (ie, adjusted R2) (Table 2). The best‐fit dimensions were help (adjusted R2=0.304), quiet (adjusted R2=0.299), doctor communication (adjusted R2=0.298), nurse communication (adjusted R2=0.245), and clean (adjusted R2=0.232). Models that were not as strongly predictive as the composite score included pain (adjusted R2=0.124), overall 9/10 (adjusted R2=0.136), definitely recommend (adjusted R2=0.150), and explained meds (adjusted R2=0.169).

A predictive formula for average positive scores was created by determination of the most predictive partial coefficients and the best‐fit model. Bachelor's degree and white only were the 2 greatest positive predictors, and number of hospital beds and nonEnglish speaking were the 2 greatest negative predictors. The PPSF (predictive formula) was chosen out of various combinations of predictors (Table 1), because its coefficient of determination (adjusted R2=0.155) was closest to the overall model's coefficient of determination (adjusted R2=0.222) without demonstrating colinearity. Possible predictive formulas were based on the predictors standardized and included the following combinations: the 2 greatest overall predictors (adjusted R2=0.051), the 2 greatest negative and positive predictors (adjusted R2=0.098), the 4 greatest overall predictors (adjusted R2=0.117), and the 8 greatest overall predictors (adjusted R2=0.201), which suffered from colinearity (household size plus nonEnglish speaking [Pearson=0.624] and under 18 years old [Pearson=0.708]). None of the correlated independent variables (eg, poverty and median income) were placed in the final model.

The mean WIPSAS scores closely corresponded with the national average of HCAHPS scores (71.6 vs 71.84) but compressed scores into a narrower distribution (SD 5.52 vs 5.92). The greatest positive and negative changes were by 8.51% and 2.25%, respectively. Essentially, a smaller number of hospitals in demographically challenged areas were more significantly impacted by the WIPSAS adjustment than the larger number of hospitals in demographically favorable areas. Large hospitals in demographically diverse counties saw the greatest positive change (e.g., Texas, California, and New York), whereas smaller hospitals in demographically nondiverse areas saw comparatively smaller decrements in the overall WIPSAS scores. The WIPSAS had the most beneficial effect on urban and rural safety‐net hospitals that serve diverse populations including many academic medical centers. This is illustrated by the reranking of the top 10 and bottom 10 hospitals in New York State by the WIPSAS (Table 3). For example, 3 academic medical centers in New York State, Montefiore Medical Center, New York Presbyterian Hospital, and Mount Sinai Hospital, were moved from the 46th, 43rd, and 42nd (out of 167 hospitals) respectively into the top 10 in patient satisfaction utilizing the WIPSAS methodology. Reported patient satisfaction scores, PPSF, WIPPSS, and WIPSAS scores for each hospital in the United States are available online (see Supporting Table S1 in the online version of this article).

| Ten Highest Ranked New York State Hospitals by HCAHPS | Ten Highest Ranked New York State Hospitals After WIPSAS |

|---|---|

| |

| 1. River Hospital, Inc. | 1. River Hospital, Inc. |

| 2. Westfield Memorial Hospital, Inc. | 2. Westfield Memorial Hospital, Inc. |

| 3. Clifton Fine Hospital | 3. Clifton Fine Hospital |

| 4. Hospital For Special Surgery | 4. Hospital For Special Surgery |

| 5. Delaware Valley Hospital, Inc. | 5. New YorkPresbyterian Hospital |

| 6. Putnam Hospital Center | 6. Delaware Valley Hospital, Inc. |

| 7. Margaretville Memorial Hospital | 7. Montefiore Medical Center |

| 8. Community Memorial Hospital, Inc. | 8. St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn |

| 9. Lewis County General Hospital | 9. Putnam Hospital Center |

| 10. St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn | 10. Mount Sinai Hospital |

DISCUSSION

The HVBP program is an incentive program that is meant to enhance the quality of care. This study illustrates healthcare inequalities in patient satisfaction that are not accounted for by the current CMS adjustments, and shows that education, ethnicity, primary language, and number of hospital beds are predictive of how patients evaluate their care via patient satisfaction scores. Hospitals that treat a disproportionate percentage of nonEnglish speaking, nonwhite, noneducated patients in large facilities are not meeting patient satisfaction standards. This inequity is not ameliorated by the adjustments currently performed by CMS, and has financial consequences for those hospitals that are not meeting national standards in patient satisfaction. These hospitals, which often include academic medical centers in urban areas, may therefore be penalized under the existing HVBP reimbursement models.

Using only 4 demographic and hospital‐specific predictors (ie, hospital beds, percent nonEnglish speaking, percent bachelors degrees, percent white), it is possible to utilize a simple formula to predict patient satisfaction with a significant degree of correlation to the reported scores available through Hospital Compare.

Our initial hypothesis that population density predicted lower patient satisfaction scores was confirmed, but these aforementioned demographic and hospital‐based factors were stronger independent predictors of HCAHPS scores. The WIPSAS is a representation of patient satisfaction and quality‐of‐care delivery across the country that accounts for nonrandom variation in patient satisfaction scores.

For hospitals in New York State, WIPSAS resulted in the placement of 3 urban‐based academic medical centers in the top 10 in patient satisfaction, when previously, based on the raw scores, their rankings were between 42nd and 46th statewide. Prior studies have suggested that large, urban, teaching, and not‐for‐profit hospitals were disadvantaged based on their hospital characteristics and patient features.[10, 11, 12] Under the current CMS reimbursement methodologies, these institutions are more likely to receive financial penalties.[8] The WIPSAS is a simple method to assess hospitals performance in the area of patient satisfaction that accounts for the demographic and hospital‐based factors (eg, number of beds) of the hospital. Its incorporation into CMS reimbursement calculations, or incorporation of a similar adjustment formula, should be strongly considered to account for predictive factors in patient satisfaction that could be addressed to enhance their scores.

Limitations for this study are the approximation of county‐level data for actual individual hospital demographic information and the exclusion of specialty hospitals, such as cancer centers and children's hospitals, in HCAHPS surveys. Repeated multivariate analyses at different time points would also serve to identify how CMS‐specific adjustments are recalibrated over time. Although we have primarily reported on the composite percent positive score as a surrogate for all HCAHPS dimensions, an individual adjustment formula could be generated for each dimension of the patient experience of care domain.

Although patient satisfaction is a component of how quality should be measured, further emphasis needs to be placed on nonrandom patient satisfaction variance so that HVBP can serve as an incentivizing program for at‐risk hospitals. Regional variation in scoring is not altogether accounted for by the current CMS adjustment system. Because patient satisfaction scores are now directly linked to reimbursement, further evaluation is needed to enhance patient satisfaction scoring paradigms to account for demographic and hospital‐specific factors.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Will choice‐based reform work for Medicare? Evidence from the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1741–1761.

- H.R. 3590. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010 (2010).

- . The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748.

- Lake Superior Quality Innovation Network. FY 2017 Value‐Based Purchasing domain weighting. Available at: http://www.stratishealth.org/documents/VBP‐FY2017.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015.

- Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing Program. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/Hospital‐Value‐Based‐Purchasing. Accessed December 1st, 2013.

- , , , . Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931.

- , . Providers must lead the way in making value the overarching goal Harvard Bus Rev. October 2013:3–19.

- , , . The effect of financial incentives on hospitals that serve poor patients. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(5):299–306.

- , . Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–343.

- . Will value‐based purchasing increase disparities in care? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2472–2474.

- , , . Hospital conversions, margins, and the provision of uncompensated care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(6):187–194.

- , , , , , . Association between value‐based purchasing score and hospital characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:464.

- , , , et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix, and nonresponse on CAHPS hospital survey scores. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(2 pt 1):501–518.

- , , , , . Patient satisfaction measurement strategies: a comparison of phone and mail methods. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27(7):349–361.

- , , . Comparing telephone and mail responses to the CAHPS survey instrument. Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Med Care. 1999;37(3 suppl):MS41–MS49.

- , , , , , . Evaluating patients' experiences with individual physicians: a randomized trial of mail, internet, and interactive voice response telephone administration of surveys. Med Care. 2006;44(2):167–174.

- , , , , . Case‐mix adjustment of the CAHPS Hospital Survey. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 pt 2):2162–2181.

- Mode and patient‐mix adjustments of CAHPS hospital survey (HCAHPS). Available at: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/modeadjustment.aspx. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- , , , , , . Adjusting performance measures to ensure equitable plan comparisons. Health Care Financ Rev. 2001;22(3):109–126.

- Official Hospital Compare Data. Displaying datasets in Patient Survey Results category. Available at: https://data.medicare.gov/data/hospital‐compare/Patient%20Survey%20Results. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Hospital statistics by state. American Hospital Directory, Inc. website. Available at: http://www.ahd.com/state_statistics.html. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- U.S. Census Download Center. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/download_center.xhtml. Accessed December 1, 2013.

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandates that government payments to hospitals and physicians must depend, in part, on metrics that assess the quality and efficiency of healthcare being provided to encourage value‐based healthcare.[1] Value in healthcare is defined by the delivery of high‐quality care at low cost.[2, 3] To this end, Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing (HVBP) and Physician Value‐Based Payment Modifier programs have been developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). HVBP is currently being phased in and affects CMS payments for fiscal year (FY) 2013 for over 3000 hospitals across the United States to incentivize healthcare delivery value. The final phase of implementation will be in FY 2017 and will then affect 2% of all CMS hospital reimbursement. HVBP is based on objective measures of hospital performance as well as a subjective measure of performance captured under the Patient Experience of Care domain. This subjective measure will remain at 30% of the aggregate score until FY 2016, when it will then be 25% the aggregate score moving forward.[4] The program rewards hospitals for both overall achievement and improvement in any domain, so that hospitals have multiple ways to receive financial incentives for providing quality care.[5] Even still, there appears to be a nonrandom pattern of patient satisfaction scores across the country with less favorable scores clustering in densely populated areas.[6]

Value‐Based Purchasing and other incentive‐based programs have been criticized for increasing disparities in healthcare by penalizing larger hospitals (including academic medical centers, safety‐net hospitals, and others that disproportionately serve lower socioeconomic communities) and favoring physician‐based specialty hospitals.[7, 8, 9] Therefore, hospitals that serve indigent and elderly populations may be at a disadvantage.[9, 10] HVBP portends significant economic consequences for the majority of hospitals that rely heavily on Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement, as most hospitals have large revenues but low profit margins.[11] Higher HVBP scores are associated with for profit status, smaller size, and location in certain areas of the United States.[12] Jha et al.[6] described Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores regional geographic variability, but concluded that poor satisfaction was due to poor quality.

The Patient Experience of Care domain quantifies patient satisfaction using the validated HCAHPS survey, which is provided to a random sample of patients continuously throughout the year at 48 hours to 6 weeks after discharge. It is a publically available standardized survey instrument used to measure patients perspectives on hospital care. It assesses the following 8 dimensions: nurse communication, doctor communication, hospital staff responsiveness, pain management, medicine communication, discharge information, hospital cleanliness and quietness, and overall hospital rating, of which the last 2 dimensions each have 2 measures (cleanliness and quietness) and (rating 9 or 10 and definitely recommend) to give a total of 10 distinct measures.

The United States is a complex network of urban, suburban, and rural demographic areas. Hospitals exist within a unique contextual and compositional meshwork that determines its caseload. The top population density decile of the United States lives within 37 counties, whereas half of the most populous parts of the United States occupy a total of 250 counties out of a total of 3143 counties in the United States. If the 10 measures of patient satisfaction (HCAHPS) scores were abstracted from hospitals and viewed according to county‐level population density (separated into deciles across the United States), a trend would be apparent (Figure 1). Greater population density is associated with lower patient satisfaction in 9 of 10 categories. On the state level, composite scores of overall patient satisfaction (amount of positive scores) of hospitals show a 12% variability and a significant correlation with population density (r=0.479; Figure 2). The lowest overall satisfaction scores are obtained from hospitals located in the population‐dense regions of Washington, DC, New York State, California, Maryland, and New Jersey (ie, 63%65%), and the best scores are from Louisiana, South Dakota, Iowa, Maine, and Vermont (ie, 74%75%). The average patient satisfaction score is 71%2.9%. Lower patient satisfaction scores appear to cluster in population‐dense areas and may be associated with greater heterogeneous patient demographics and economic variability in addition to population density.

These observations are surprising considering that CMS already adjusts HCAHPS scores based on patient‐mix coefficients and mode of collection.[13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] Adjustments are updated multiple times per year and account for survey collection either by telephone, email, or paper survey, because the populations that select survey forms will differ. Previous studies have shown that demographic features influence the patient evaluation process. For example, younger and more educated patients were found to provide less positive evaluations of healthcare.[19]

This study examined whether patients perceptions of healthcare (pattern of patient satisfaction) as quantified under the patient experience domain of HVBP were affected and predicted by population density and other demographic factors that are outside the control of individual hospitals. In addition, hospital‐level data (eg, number of hospital beds) and county‐level data such as race, age, gender, overall population, income, time spent commuting to work, primary language, and place of birth were analyzed for correlation with patient satisfaction scores. Our study demonstrates that demographic and hospital‐level data can predict patient satisfaction scores and suggests that CMS may need to modify its adjustment formulas to eliminate bias in HVBP‐based reimbursement.

METHODS

Data Collection

Publically available data were obtained from Hospital Compare,[20] American Hospital Directory,[21] and the US Census Bureau[22] websites. Twenty relevant US Census data categories were selected by their relevance for this study out of the 50 publically reported US Census categories, and included the following: county population, county population density, percent of population change over 1 year, poverty level (percent), income level per capita, median household income, average household size, travel time to work, percentage of high school or college graduates, non‐English primary language spoken at home, percentage of residents born outside of the United States, population percent in same residence for over 1 year, gender, race (white alone, white alone (not Hispanic or Latino), black or African American alone), population over 65 years old, and population under 18 years old.

HCAHPS Development

The HCAHPS survey is 32 questions in length, comprised of 10 evaluative dimensions. All short‐term, acute care, nonspecialty hospitals are invited to participate in the HCAHPS survey.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data were checked for statistical assumptions, including normality, linearity of relationships, and full range of scores. Categories in both the Hospital Compare (HCAHPS) and US Census datasets were analyzed to assess their distribution curves. The category of population densities (per county) was converted to a logarithmic scale to account for a skewed distribution and long tail in the area of low population density. Data were subsequently merged into an Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet using the VLookup function such that relevant 2010 census county data were added to each hospital's Hospital Compare data. Linear regression modeling was performed. Bivariate analysis was conducted (ENTER method) to determine the significant US Census data predictors for each of the 10 Hospital Compare dimensions including the composite overall satisfaction score. Significant predictors were then analyzed in a multivariate model (BACKWORDS method) for each Hospital Compare dimension and the composite average positive score. Models were assessed by determinates of correlation (adjusted R2) to assess for goodness of fit. Statistically significant predictor variables for overall patient satisfaction scores were then ranked according to their partial regression coefficients (standardized ).

A patient satisfaction predictive model was sought based upon significant predictors of aggregate percent positive HCAHPS scores. Various predictor combinations were formed based on their partial coefficients (ie, standardized coefficients); combinations were assessed based on their R2 values and assessed for colinearity. Combinations of partial coefficients included the 2, 4, and 8 most predictive variables as well the 2 most positive and negative predictors. They were then incorporated into a multivariate analysis model (FORWARD method) and assessed based on their adjusted R2 values. A 4‐variable combination (the 2 most predictive positive partial coefficients plus the 2 most predictive negative partial coefficients) was selected as a predictive model, and a formula predictive of the composite overall satisfaction score was generated. This formula (predicted patient satisfaction formula [PPSF]) predicts hospital patient satisfaction HCAHPS scores based on the 4 predictive variables for particular county and hospital characteristics.

| B | SE | t | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Educational attainmentbachelor's degree | 0.157 | 0.018 | 0.27 | 8.612 | <0.001 |

| White alone percent 2012 | 0.09 | 0.012 | 0.235 | 7.587 | <0.001 |

| Resident population percent under 18 years | 0.404 | 0.0444 | 0.209 | 9.085 | <0.001 |

| Black or African American alone percent 2012 | 0.083 | 0.014 | 0.191 | 5.936 | <0.001 |

| Median household income 20072011 | 0.00003 | 0.00 | 0.062 | 2.027 | 0.043 |

| Population density (log) 2010 | 0.277 | 0.083 | 0.087 | 3.3333 | 0.001 |

| Average travel time to work | 0.107 | 0.024 | 0.088 | 4.366 | <0.001 |

| Educational attainmenthigh school | 0.082 | 0.026 | 0.088 | 3.147 | 0.002 |

| Average household size | 2.58 | 0.727 | 0.107 | 3.55 | <0.001 |

| Total females percent 2012 | 0.423 | 0.067 | 0.107 | 6.296 | <0.001 |

| Percent nonEnglish speaking at home 20072011 | 0.052 | 0.018 | 0.14 | 2.929 | 0.003 |

| No. of hospital beds | 0.006 | 0.00 | 0.213 | 12.901 | <0.001 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.222 | ||||

The PPSF was then modified by weighting with the partial coefficient () to remove the bias in patient satisfaction generated by demographic and structural factors over which individual hospitals have limited or no control. This formula generated a Weighted Individual (hospital) Predicted Patient Satisfaction Score (WIPPSS). Application of this formula narrowed the predicted distribution of patient satisfaction for all hospitals across the country.

To create an adjusted score with direct relevance to the reported patient satisfaction scores, the reported scores were multiplied by an adjustment factor that defines the difference between individual hospital‐weighted scores and the national mean HCAHPS score across the United States. This formula, the Weighted Individual (hospital) Patient Satisfaction Adjustment Score (WIPSAS), represents a patient satisfaction score adjusted for demographic and structural factors that can be utilized for interhospital comparisons across all areas of the country.

where PSrep=patient satisfaction reported score, PSUSA=mean reported score for United States (71.84), and WIPPSSX=WIPPSS for individual hospital.

Application of Data Analysis

PPSF, WIPPSS, and WIPSAS were calculated for all HCAHPS‐participating hospitals and compared with averaged raw HCAHPS scores across the United States. WIPSAS and raw scores were specifically analyzed for New York State to demonstrate exactly how adjustments would change state‐level rankings.

RESULTS

Complete HCAHPS scores were obtained from 3907 hospitals out of a total 4621 hospitals listed by the Hospital Compare website (85%). The majority of hospitals (2884) collected over 300 surveys, fewer hospitals (696) collected 100 to 299 surveys, and fewer still (333) collected <100 surveys. In total, results were available from at least 934,800 individual surveys, by the most conservative estimate. Missing HCAHPS hospital data averaged 13.4 (standard deviation [SD] 12.2) hospitals per state. County‐level data were obtained from all 3144 county or county equivalents across the United States (100%). Multivariate regression modeling across all HCAHPS dimensions found that between 10 and 16 of the 20 predictors (US Census categories) were statistically significant and predictive of individual HCAHPS dimension scores and the aggregate percent positive score as demonstrated in Table 2. For example, county percentage of bachelors degrees positively predicts for positive doctor communication scores, and hospital beds negatively predicts for quiet dimension. The strongest positive and negative predictive variables by model regression coefficients for each HCAHPS dimension are also listed in Table 2.

| Average Positive Scores | Nurse Communication | Doctor Communication | Help | Pain | Explain Meds | Clean | Quiet | Discharge Explain | Recommend 9/10 | Definitely Recommend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Educationalbachelor's | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.416 |

| Hospital beds | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| Population density 2010 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.07 | * |

| White alone percent | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.317 | |

| Total females percent | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.09 | |

| African American alone | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.34 | * | 0.09 | 0.084 | |

| Average travel time to work | 0.09 | 0.10 | * | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | * | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Foreign‐born percent | * | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.18 | * | * |

| Average household size | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.07 | * | 0.07 | * | 0.01 | * | 0.07 | 0.076 |

| NonEnglish speaking | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.07 | * | * | * | * | * | 0.34 | 0.28 |

| Educationhigh school | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.40 | * | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.08 | * | |||

| Household income | 0.06 | * | 0.35 | 0.08 | * | * | 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.265 | ||

| Population 65 years and over | * | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 | * | 0.11 | 0.15 | * | 0.10 | ||

| White, not Hispanic/Latino | * | * | 0.20 | * | * | * | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| Population under 18 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.20 | ||||||

| Population (county) | * | 0.06 | 0.08 | * | 0.03 | 0.05 | * | * | 0.06 | * | * |

| All ages in poverty | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.08 | * | 0.281 | |||||

| 1 year at same residence | * | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 | * | 0.04 | * | * | ||

| Per capita income | * | 0.07 | * | * | * | * | * | 0.09 | * | ||

| Population percent change | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0.05 | * | * | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

Table 1 highlights multivariate regression modeling of the composite average positive score, which produced an adjusted R2 of 0.222 (P<0.001). All variables were significant and predicted change of the composite HCAHPS except for place of birthforeign born (not listed in the table). Table 1 ranks variables from most positive to most negative predictors.

Other HCAHPS domains demonstrated statistically significant models (P<0.001) and are listed by their coefficients of determination (ie, adjusted R2) (Table 2). The best‐fit dimensions were help (adjusted R2=0.304), quiet (adjusted R2=0.299), doctor communication (adjusted R2=0.298), nurse communication (adjusted R2=0.245), and clean (adjusted R2=0.232). Models that were not as strongly predictive as the composite score included pain (adjusted R2=0.124), overall 9/10 (adjusted R2=0.136), definitely recommend (adjusted R2=0.150), and explained meds (adjusted R2=0.169).

A predictive formula for average positive scores was created by determination of the most predictive partial coefficients and the best‐fit model. Bachelor's degree and white only were the 2 greatest positive predictors, and number of hospital beds and nonEnglish speaking were the 2 greatest negative predictors. The PPSF (predictive formula) was chosen out of various combinations of predictors (Table 1), because its coefficient of determination (adjusted R2=0.155) was closest to the overall model's coefficient of determination (adjusted R2=0.222) without demonstrating colinearity. Possible predictive formulas were based on the predictors standardized and included the following combinations: the 2 greatest overall predictors (adjusted R2=0.051), the 2 greatest negative and positive predictors (adjusted R2=0.098), the 4 greatest overall predictors (adjusted R2=0.117), and the 8 greatest overall predictors (adjusted R2=0.201), which suffered from colinearity (household size plus nonEnglish speaking [Pearson=0.624] and under 18 years old [Pearson=0.708]). None of the correlated independent variables (eg, poverty and median income) were placed in the final model.

The mean WIPSAS scores closely corresponded with the national average of HCAHPS scores (71.6 vs 71.84) but compressed scores into a narrower distribution (SD 5.52 vs 5.92). The greatest positive and negative changes were by 8.51% and 2.25%, respectively. Essentially, a smaller number of hospitals in demographically challenged areas were more significantly impacted by the WIPSAS adjustment than the larger number of hospitals in demographically favorable areas. Large hospitals in demographically diverse counties saw the greatest positive change (e.g., Texas, California, and New York), whereas smaller hospitals in demographically nondiverse areas saw comparatively smaller decrements in the overall WIPSAS scores. The WIPSAS had the most beneficial effect on urban and rural safety‐net hospitals that serve diverse populations including many academic medical centers. This is illustrated by the reranking of the top 10 and bottom 10 hospitals in New York State by the WIPSAS (Table 3). For example, 3 academic medical centers in New York State, Montefiore Medical Center, New York Presbyterian Hospital, and Mount Sinai Hospital, were moved from the 46th, 43rd, and 42nd (out of 167 hospitals) respectively into the top 10 in patient satisfaction utilizing the WIPSAS methodology. Reported patient satisfaction scores, PPSF, WIPPSS, and WIPSAS scores for each hospital in the United States are available online (see Supporting Table S1 in the online version of this article).

| Ten Highest Ranked New York State Hospitals by HCAHPS | Ten Highest Ranked New York State Hospitals After WIPSAS |

|---|---|

| |

| 1. River Hospital, Inc. | 1. River Hospital, Inc. |

| 2. Westfield Memorial Hospital, Inc. | 2. Westfield Memorial Hospital, Inc. |

| 3. Clifton Fine Hospital | 3. Clifton Fine Hospital |

| 4. Hospital For Special Surgery | 4. Hospital For Special Surgery |

| 5. Delaware Valley Hospital, Inc. | 5. New YorkPresbyterian Hospital |

| 6. Putnam Hospital Center | 6. Delaware Valley Hospital, Inc. |

| 7. Margaretville Memorial Hospital | 7. Montefiore Medical Center |

| 8. Community Memorial Hospital, Inc. | 8. St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn |

| 9. Lewis County General Hospital | 9. Putnam Hospital Center |

| 10. St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn | 10. Mount Sinai Hospital |

DISCUSSION

The HVBP program is an incentive program that is meant to enhance the quality of care. This study illustrates healthcare inequalities in patient satisfaction that are not accounted for by the current CMS adjustments, and shows that education, ethnicity, primary language, and number of hospital beds are predictive of how patients evaluate their care via patient satisfaction scores. Hospitals that treat a disproportionate percentage of nonEnglish speaking, nonwhite, noneducated patients in large facilities are not meeting patient satisfaction standards. This inequity is not ameliorated by the adjustments currently performed by CMS, and has financial consequences for those hospitals that are not meeting national standards in patient satisfaction. These hospitals, which often include academic medical centers in urban areas, may therefore be penalized under the existing HVBP reimbursement models.

Using only 4 demographic and hospital‐specific predictors (ie, hospital beds, percent nonEnglish speaking, percent bachelors degrees, percent white), it is possible to utilize a simple formula to predict patient satisfaction with a significant degree of correlation to the reported scores available through Hospital Compare.

Our initial hypothesis that population density predicted lower patient satisfaction scores was confirmed, but these aforementioned demographic and hospital‐based factors were stronger independent predictors of HCAHPS scores. The WIPSAS is a representation of patient satisfaction and quality‐of‐care delivery across the country that accounts for nonrandom variation in patient satisfaction scores.

For hospitals in New York State, WIPSAS resulted in the placement of 3 urban‐based academic medical centers in the top 10 in patient satisfaction, when previously, based on the raw scores, their rankings were between 42nd and 46th statewide. Prior studies have suggested that large, urban, teaching, and not‐for‐profit hospitals were disadvantaged based on their hospital characteristics and patient features.[10, 11, 12] Under the current CMS reimbursement methodologies, these institutions are more likely to receive financial penalties.[8] The WIPSAS is a simple method to assess hospitals performance in the area of patient satisfaction that accounts for the demographic and hospital‐based factors (eg, number of beds) of the hospital. Its incorporation into CMS reimbursement calculations, or incorporation of a similar adjustment formula, should be strongly considered to account for predictive factors in patient satisfaction that could be addressed to enhance their scores.

Limitations for this study are the approximation of county‐level data for actual individual hospital demographic information and the exclusion of specialty hospitals, such as cancer centers and children's hospitals, in HCAHPS surveys. Repeated multivariate analyses at different time points would also serve to identify how CMS‐specific adjustments are recalibrated over time. Although we have primarily reported on the composite percent positive score as a surrogate for all HCAHPS dimensions, an individual adjustment formula could be generated for each dimension of the patient experience of care domain.

Although patient satisfaction is a component of how quality should be measured, further emphasis needs to be placed on nonrandom patient satisfaction variance so that HVBP can serve as an incentivizing program for at‐risk hospitals. Regional variation in scoring is not altogether accounted for by the current CMS adjustment system. Because patient satisfaction scores are now directly linked to reimbursement, further evaluation is needed to enhance patient satisfaction scoring paradigms to account for demographic and hospital‐specific factors.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandates that government payments to hospitals and physicians must depend, in part, on metrics that assess the quality and efficiency of healthcare being provided to encourage value‐based healthcare.[1] Value in healthcare is defined by the delivery of high‐quality care at low cost.[2, 3] To this end, Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing (HVBP) and Physician Value‐Based Payment Modifier programs have been developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). HVBP is currently being phased in and affects CMS payments for fiscal year (FY) 2013 for over 3000 hospitals across the United States to incentivize healthcare delivery value. The final phase of implementation will be in FY 2017 and will then affect 2% of all CMS hospital reimbursement. HVBP is based on objective measures of hospital performance as well as a subjective measure of performance captured under the Patient Experience of Care domain. This subjective measure will remain at 30% of the aggregate score until FY 2016, when it will then be 25% the aggregate score moving forward.[4] The program rewards hospitals for both overall achievement and improvement in any domain, so that hospitals have multiple ways to receive financial incentives for providing quality care.[5] Even still, there appears to be a nonrandom pattern of patient satisfaction scores across the country with less favorable scores clustering in densely populated areas.[6]

Value‐Based Purchasing and other incentive‐based programs have been criticized for increasing disparities in healthcare by penalizing larger hospitals (including academic medical centers, safety‐net hospitals, and others that disproportionately serve lower socioeconomic communities) and favoring physician‐based specialty hospitals.[7, 8, 9] Therefore, hospitals that serve indigent and elderly populations may be at a disadvantage.[9, 10] HVBP portends significant economic consequences for the majority of hospitals that rely heavily on Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement, as most hospitals have large revenues but low profit margins.[11] Higher HVBP scores are associated with for profit status, smaller size, and location in certain areas of the United States.[12] Jha et al.[6] described Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores regional geographic variability, but concluded that poor satisfaction was due to poor quality.

The Patient Experience of Care domain quantifies patient satisfaction using the validated HCAHPS survey, which is provided to a random sample of patients continuously throughout the year at 48 hours to 6 weeks after discharge. It is a publically available standardized survey instrument used to measure patients perspectives on hospital care. It assesses the following 8 dimensions: nurse communication, doctor communication, hospital staff responsiveness, pain management, medicine communication, discharge information, hospital cleanliness and quietness, and overall hospital rating, of which the last 2 dimensions each have 2 measures (cleanliness and quietness) and (rating 9 or 10 and definitely recommend) to give a total of 10 distinct measures.

The United States is a complex network of urban, suburban, and rural demographic areas. Hospitals exist within a unique contextual and compositional meshwork that determines its caseload. The top population density decile of the United States lives within 37 counties, whereas half of the most populous parts of the United States occupy a total of 250 counties out of a total of 3143 counties in the United States. If the 10 measures of patient satisfaction (HCAHPS) scores were abstracted from hospitals and viewed according to county‐level population density (separated into deciles across the United States), a trend would be apparent (Figure 1). Greater population density is associated with lower patient satisfaction in 9 of 10 categories. On the state level, composite scores of overall patient satisfaction (amount of positive scores) of hospitals show a 12% variability and a significant correlation with population density (r=0.479; Figure 2). The lowest overall satisfaction scores are obtained from hospitals located in the population‐dense regions of Washington, DC, New York State, California, Maryland, and New Jersey (ie, 63%65%), and the best scores are from Louisiana, South Dakota, Iowa, Maine, and Vermont (ie, 74%75%). The average patient satisfaction score is 71%2.9%. Lower patient satisfaction scores appear to cluster in population‐dense areas and may be associated with greater heterogeneous patient demographics and economic variability in addition to population density.

These observations are surprising considering that CMS already adjusts HCAHPS scores based on patient‐mix coefficients and mode of collection.[13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18] Adjustments are updated multiple times per year and account for survey collection either by telephone, email, or paper survey, because the populations that select survey forms will differ. Previous studies have shown that demographic features influence the patient evaluation process. For example, younger and more educated patients were found to provide less positive evaluations of healthcare.[19]

This study examined whether patients perceptions of healthcare (pattern of patient satisfaction) as quantified under the patient experience domain of HVBP were affected and predicted by population density and other demographic factors that are outside the control of individual hospitals. In addition, hospital‐level data (eg, number of hospital beds) and county‐level data such as race, age, gender, overall population, income, time spent commuting to work, primary language, and place of birth were analyzed for correlation with patient satisfaction scores. Our study demonstrates that demographic and hospital‐level data can predict patient satisfaction scores and suggests that CMS may need to modify its adjustment formulas to eliminate bias in HVBP‐based reimbursement.

METHODS

Data Collection

Publically available data were obtained from Hospital Compare,[20] American Hospital Directory,[21] and the US Census Bureau[22] websites. Twenty relevant US Census data categories were selected by their relevance for this study out of the 50 publically reported US Census categories, and included the following: county population, county population density, percent of population change over 1 year, poverty level (percent), income level per capita, median household income, average household size, travel time to work, percentage of high school or college graduates, non‐English primary language spoken at home, percentage of residents born outside of the United States, population percent in same residence for over 1 year, gender, race (white alone, white alone (not Hispanic or Latino), black or African American alone), population over 65 years old, and population under 18 years old.

HCAHPS Development

The HCAHPS survey is 32 questions in length, comprised of 10 evaluative dimensions. All short‐term, acute care, nonspecialty hospitals are invited to participate in the HCAHPS survey.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data were checked for statistical assumptions, including normality, linearity of relationships, and full range of scores. Categories in both the Hospital Compare (HCAHPS) and US Census datasets were analyzed to assess their distribution curves. The category of population densities (per county) was converted to a logarithmic scale to account for a skewed distribution and long tail in the area of low population density. Data were subsequently merged into an Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet using the VLookup function such that relevant 2010 census county data were added to each hospital's Hospital Compare data. Linear regression modeling was performed. Bivariate analysis was conducted (ENTER method) to determine the significant US Census data predictors for each of the 10 Hospital Compare dimensions including the composite overall satisfaction score. Significant predictors were then analyzed in a multivariate model (BACKWORDS method) for each Hospital Compare dimension and the composite average positive score. Models were assessed by determinates of correlation (adjusted R2) to assess for goodness of fit. Statistically significant predictor variables for overall patient satisfaction scores were then ranked according to their partial regression coefficients (standardized ).

A patient satisfaction predictive model was sought based upon significant predictors of aggregate percent positive HCAHPS scores. Various predictor combinations were formed based on their partial coefficients (ie, standardized coefficients); combinations were assessed based on their R2 values and assessed for colinearity. Combinations of partial coefficients included the 2, 4, and 8 most predictive variables as well the 2 most positive and negative predictors. They were then incorporated into a multivariate analysis model (FORWARD method) and assessed based on their adjusted R2 values. A 4‐variable combination (the 2 most predictive positive partial coefficients plus the 2 most predictive negative partial coefficients) was selected as a predictive model, and a formula predictive of the composite overall satisfaction score was generated. This formula (predicted patient satisfaction formula [PPSF]) predicts hospital patient satisfaction HCAHPS scores based on the 4 predictive variables for particular county and hospital characteristics.

| B | SE | t | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Educational attainmentbachelor's degree | 0.157 | 0.018 | 0.27 | 8.612 | <0.001 |

| White alone percent 2012 | 0.09 | 0.012 | 0.235 | 7.587 | <0.001 |

| Resident population percent under 18 years | 0.404 | 0.0444 | 0.209 | 9.085 | <0.001 |

| Black or African American alone percent 2012 | 0.083 | 0.014 | 0.191 | 5.936 | <0.001 |

| Median household income 20072011 | 0.00003 | 0.00 | 0.062 | 2.027 | 0.043 |

| Population density (log) 2010 | 0.277 | 0.083 | 0.087 | 3.3333 | 0.001 |

| Average travel time to work | 0.107 | 0.024 | 0.088 | 4.366 | <0.001 |

| Educational attainmenthigh school | 0.082 | 0.026 | 0.088 | 3.147 | 0.002 |

| Average household size | 2.58 | 0.727 | 0.107 | 3.55 | <0.001 |

| Total females percent 2012 | 0.423 | 0.067 | 0.107 | 6.296 | <0.001 |

| Percent nonEnglish speaking at home 20072011 | 0.052 | 0.018 | 0.14 | 2.929 | 0.003 |

| No. of hospital beds | 0.006 | 0.00 | 0.213 | 12.901 | <0.001 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.222 | ||||

The PPSF was then modified by weighting with the partial coefficient () to remove the bias in patient satisfaction generated by demographic and structural factors over which individual hospitals have limited or no control. This formula generated a Weighted Individual (hospital) Predicted Patient Satisfaction Score (WIPPSS). Application of this formula narrowed the predicted distribution of patient satisfaction for all hospitals across the country.

To create an adjusted score with direct relevance to the reported patient satisfaction scores, the reported scores were multiplied by an adjustment factor that defines the difference between individual hospital‐weighted scores and the national mean HCAHPS score across the United States. This formula, the Weighted Individual (hospital) Patient Satisfaction Adjustment Score (WIPSAS), represents a patient satisfaction score adjusted for demographic and structural factors that can be utilized for interhospital comparisons across all areas of the country.

where PSrep=patient satisfaction reported score, PSUSA=mean reported score for United States (71.84), and WIPPSSX=WIPPSS for individual hospital.

Application of Data Analysis

PPSF, WIPPSS, and WIPSAS were calculated for all HCAHPS‐participating hospitals and compared with averaged raw HCAHPS scores across the United States. WIPSAS and raw scores were specifically analyzed for New York State to demonstrate exactly how adjustments would change state‐level rankings.

RESULTS

Complete HCAHPS scores were obtained from 3907 hospitals out of a total 4621 hospitals listed by the Hospital Compare website (85%). The majority of hospitals (2884) collected over 300 surveys, fewer hospitals (696) collected 100 to 299 surveys, and fewer still (333) collected <100 surveys. In total, results were available from at least 934,800 individual surveys, by the most conservative estimate. Missing HCAHPS hospital data averaged 13.4 (standard deviation [SD] 12.2) hospitals per state. County‐level data were obtained from all 3144 county or county equivalents across the United States (100%). Multivariate regression modeling across all HCAHPS dimensions found that between 10 and 16 of the 20 predictors (US Census categories) were statistically significant and predictive of individual HCAHPS dimension scores and the aggregate percent positive score as demonstrated in Table 2. For example, county percentage of bachelors degrees positively predicts for positive doctor communication scores, and hospital beds negatively predicts for quiet dimension. The strongest positive and negative predictive variables by model regression coefficients for each HCAHPS dimension are also listed in Table 2.

| Average Positive Scores | Nurse Communication | Doctor Communication | Help | Pain | Explain Meds | Clean | Quiet | Discharge Explain | Recommend 9/10 | Definitely Recommend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Educationalbachelor's | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.416 |

| Hospital beds | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| Population density 2010 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.07 | * |

| White alone percent | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.317 | |

| Total females percent | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.09 | |

| African American alone | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.34 | * | 0.09 | 0.084 | |

| Average travel time to work | 0.09 | 0.10 | * | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | * | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Foreign‐born percent | * | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.18 | * | * |

| Average household size | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.07 | * | 0.07 | * | 0.01 | * | 0.07 | 0.076 |

| NonEnglish speaking | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.07 | * | * | * | * | * | 0.34 | 0.28 |

| Educationhigh school | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.40 | * | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.08 | * | |||

| Household income | 0.06 | * | 0.35 | 0.08 | * | * | 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.265 | ||

| Population 65 years and over | * | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 | * | 0.11 | 0.15 | * | 0.10 | ||

| White, not Hispanic/Latino | * | * | 0.20 | * | * | * | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| Population under 18 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.20 | ||||||

| Population (county) | * | 0.06 | 0.08 | * | 0.03 | 0.05 | * | * | 0.06 | * | * |

| All ages in poverty | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.08 | * | 0.281 | |||||

| 1 year at same residence | * | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 | * | 0.04 | * | * | ||

| Per capita income | * | 0.07 | * | * | * | * | * | 0.09 | * | ||

| Population percent change | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0.05 | * | * | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

Table 1 highlights multivariate regression modeling of the composite average positive score, which produced an adjusted R2 of 0.222 (P<0.001). All variables were significant and predicted change of the composite HCAHPS except for place of birthforeign born (not listed in the table). Table 1 ranks variables from most positive to most negative predictors.

Other HCAHPS domains demonstrated statistically significant models (P<0.001) and are listed by their coefficients of determination (ie, adjusted R2) (Table 2). The best‐fit dimensions were help (adjusted R2=0.304), quiet (adjusted R2=0.299), doctor communication (adjusted R2=0.298), nurse communication (adjusted R2=0.245), and clean (adjusted R2=0.232). Models that were not as strongly predictive as the composite score included pain (adjusted R2=0.124), overall 9/10 (adjusted R2=0.136), definitely recommend (adjusted R2=0.150), and explained meds (adjusted R2=0.169).

A predictive formula for average positive scores was created by determination of the most predictive partial coefficients and the best‐fit model. Bachelor's degree and white only were the 2 greatest positive predictors, and number of hospital beds and nonEnglish speaking were the 2 greatest negative predictors. The PPSF (predictive formula) was chosen out of various combinations of predictors (Table 1), because its coefficient of determination (adjusted R2=0.155) was closest to the overall model's coefficient of determination (adjusted R2=0.222) without demonstrating colinearity. Possible predictive formulas were based on the predictors standardized and included the following combinations: the 2 greatest overall predictors (adjusted R2=0.051), the 2 greatest negative and positive predictors (adjusted R2=0.098), the 4 greatest overall predictors (adjusted R2=0.117), and the 8 greatest overall predictors (adjusted R2=0.201), which suffered from colinearity (household size plus nonEnglish speaking [Pearson=0.624] and under 18 years old [Pearson=0.708]). None of the correlated independent variables (eg, poverty and median income) were placed in the final model.

The mean WIPSAS scores closely corresponded with the national average of HCAHPS scores (71.6 vs 71.84) but compressed scores into a narrower distribution (SD 5.52 vs 5.92). The greatest positive and negative changes were by 8.51% and 2.25%, respectively. Essentially, a smaller number of hospitals in demographically challenged areas were more significantly impacted by the WIPSAS adjustment than the larger number of hospitals in demographically favorable areas. Large hospitals in demographically diverse counties saw the greatest positive change (e.g., Texas, California, and New York), whereas smaller hospitals in demographically nondiverse areas saw comparatively smaller decrements in the overall WIPSAS scores. The WIPSAS had the most beneficial effect on urban and rural safety‐net hospitals that serve diverse populations including many academic medical centers. This is illustrated by the reranking of the top 10 and bottom 10 hospitals in New York State by the WIPSAS (Table 3). For example, 3 academic medical centers in New York State, Montefiore Medical Center, New York Presbyterian Hospital, and Mount Sinai Hospital, were moved from the 46th, 43rd, and 42nd (out of 167 hospitals) respectively into the top 10 in patient satisfaction utilizing the WIPSAS methodology. Reported patient satisfaction scores, PPSF, WIPPSS, and WIPSAS scores for each hospital in the United States are available online (see Supporting Table S1 in the online version of this article).

| Ten Highest Ranked New York State Hospitals by HCAHPS | Ten Highest Ranked New York State Hospitals After WIPSAS |

|---|---|

| |

| 1. River Hospital, Inc. | 1. River Hospital, Inc. |

| 2. Westfield Memorial Hospital, Inc. | 2. Westfield Memorial Hospital, Inc. |

| 3. Clifton Fine Hospital | 3. Clifton Fine Hospital |

| 4. Hospital For Special Surgery | 4. Hospital For Special Surgery |

| 5. Delaware Valley Hospital, Inc. | 5. New YorkPresbyterian Hospital |

| 6. Putnam Hospital Center | 6. Delaware Valley Hospital, Inc. |

| 7. Margaretville Memorial Hospital | 7. Montefiore Medical Center |

| 8. Community Memorial Hospital, Inc. | 8. St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn |

| 9. Lewis County General Hospital | 9. Putnam Hospital Center |

| 10. St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn | 10. Mount Sinai Hospital |

DISCUSSION

The HVBP program is an incentive program that is meant to enhance the quality of care. This study illustrates healthcare inequalities in patient satisfaction that are not accounted for by the current CMS adjustments, and shows that education, ethnicity, primary language, and number of hospital beds are predictive of how patients evaluate their care via patient satisfaction scores. Hospitals that treat a disproportionate percentage of nonEnglish speaking, nonwhite, noneducated patients in large facilities are not meeting patient satisfaction standards. This inequity is not ameliorated by the adjustments currently performed by CMS, and has financial consequences for those hospitals that are not meeting national standards in patient satisfaction. These hospitals, which often include academic medical centers in urban areas, may therefore be penalized under the existing HVBP reimbursement models.

Using only 4 demographic and hospital‐specific predictors (ie, hospital beds, percent nonEnglish speaking, percent bachelors degrees, percent white), it is possible to utilize a simple formula to predict patient satisfaction with a significant degree of correlation to the reported scores available through Hospital Compare.

Our initial hypothesis that population density predicted lower patient satisfaction scores was confirmed, but these aforementioned demographic and hospital‐based factors were stronger independent predictors of HCAHPS scores. The WIPSAS is a representation of patient satisfaction and quality‐of‐care delivery across the country that accounts for nonrandom variation in patient satisfaction scores.

For hospitals in New York State, WIPSAS resulted in the placement of 3 urban‐based academic medical centers in the top 10 in patient satisfaction, when previously, based on the raw scores, their rankings were between 42nd and 46th statewide. Prior studies have suggested that large, urban, teaching, and not‐for‐profit hospitals were disadvantaged based on their hospital characteristics and patient features.[10, 11, 12] Under the current CMS reimbursement methodologies, these institutions are more likely to receive financial penalties.[8] The WIPSAS is a simple method to assess hospitals performance in the area of patient satisfaction that accounts for the demographic and hospital‐based factors (eg, number of beds) of the hospital. Its incorporation into CMS reimbursement calculations, or incorporation of a similar adjustment formula, should be strongly considered to account for predictive factors in patient satisfaction that could be addressed to enhance their scores.

Limitations for this study are the approximation of county‐level data for actual individual hospital demographic information and the exclusion of specialty hospitals, such as cancer centers and children's hospitals, in HCAHPS surveys. Repeated multivariate analyses at different time points would also serve to identify how CMS‐specific adjustments are recalibrated over time. Although we have primarily reported on the composite percent positive score as a surrogate for all HCAHPS dimensions, an individual adjustment formula could be generated for each dimension of the patient experience of care domain.

Although patient satisfaction is a component of how quality should be measured, further emphasis needs to be placed on nonrandom patient satisfaction variance so that HVBP can serve as an incentivizing program for at‐risk hospitals. Regional variation in scoring is not altogether accounted for by the current CMS adjustment system. Because patient satisfaction scores are now directly linked to reimbursement, further evaluation is needed to enhance patient satisfaction scoring paradigms to account for demographic and hospital‐specific factors.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Will choice‐based reform work for Medicare? Evidence from the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1741–1761.

- H.R. 3590. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010 (2010).

- . The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748.

- Lake Superior Quality Innovation Network. FY 2017 Value‐Based Purchasing domain weighting. Available at: http://www.stratishealth.org/documents/VBP‐FY2017.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015.

- Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing Program. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/Hospital‐Value‐Based‐Purchasing. Accessed December 1st, 2013.

- , , , . Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931.

- , . Providers must lead the way in making value the overarching goal Harvard Bus Rev. October 2013:3–19.

- , , . The effect of financial incentives on hospitals that serve poor patients. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(5):299–306.

- , . Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–343.

- . Will value‐based purchasing increase disparities in care? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2472–2474.

- , , . Hospital conversions, margins, and the provision of uncompensated care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(6):187–194.

- , , , , , . Association between value‐based purchasing score and hospital characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:464.

- , , , et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix, and nonresponse on CAHPS hospital survey scores. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(2 pt 1):501–518.

- , , , , . Patient satisfaction measurement strategies: a comparison of phone and mail methods. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27(7):349–361.

- , , . Comparing telephone and mail responses to the CAHPS survey instrument. Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Med Care. 1999;37(3 suppl):MS41–MS49.

- , , , , , . Evaluating patients' experiences with individual physicians: a randomized trial of mail, internet, and interactive voice response telephone administration of surveys. Med Care. 2006;44(2):167–174.

- , , , , . Case‐mix adjustment of the CAHPS Hospital Survey. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 pt 2):2162–2181.

- Mode and patient‐mix adjustments of CAHPS hospital survey (HCAHPS). Available at: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/modeadjustment.aspx. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- , , , , , . Adjusting performance measures to ensure equitable plan comparisons. Health Care Financ Rev. 2001;22(3):109–126.

- Official Hospital Compare Data. Displaying datasets in Patient Survey Results category. Available at: https://data.medicare.gov/data/hospital‐compare/Patient%20Survey%20Results. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Hospital statistics by state. American Hospital Directory, Inc. website. Available at: http://www.ahd.com/state_statistics.html. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- U.S. Census Download Center. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/download_center.xhtml. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- , , . Will choice‐based reform work for Medicare? Evidence from the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1741–1761.

- H.R. 3590. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010 (2010).

- . The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748.

- Lake Superior Quality Innovation Network. FY 2017 Value‐Based Purchasing domain weighting. Available at: http://www.stratishealth.org/documents/VBP‐FY2017.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015.

- Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing Program. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/Hospital‐Value‐Based‐Purchasing. Accessed December 1st, 2013.

- , , , . Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931.

- , . Providers must lead the way in making value the overarching goal Harvard Bus Rev. October 2013:3–19.

- , , . The effect of financial incentives on hospitals that serve poor patients. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(5):299–306.

- , . Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–343.