User login

The time is now for physicians to ride the digital disruption wave

CHICAGO – “The health care milieu is ripe for digital disruption,” said Anton Decker, MD. Speaking at the American Gastroenterological Association Partners in Value meeting, which was developed in partnership with the Digestive Health Physicians Association, he said that physicians need to become part of the disruption before it’s too late.

There’s no sign of improvement in worrisome trends in reimbursement, said Dr. Decker, president, international, at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. The megamerger trend that is bringing together ever-larger payers, pharmacy benefit managers, and hospital groups is just one manifestation of the trend toward consolidation that’s also seen in the airline industry, in financial services, and in telecommunications, he said.

“The math is not good on the payer and health systems side,” but for physicians, “There are ways to survive trends like this if we can move ourselves higher in the food chain.”

Other players in the health care space are figuring it out, he said. For example, the state of Ohio has five Medicaid plans; in 2018, aggregate profits for these plans were approximately 400 million dollars. Laying this profit figure against the backdrop of Medicare reimbursement rates for physician services makes it clear that “we have to figure out ways to survive this game,” he said.

“Health systems keep their lights on because of the hospital reimbursements – that pays for everything else,” said Dr. Decker, adding that payments from commercial insurers fill the coffers that, in turn, pay physicians who are employed by health systems. However, there’s a sea change underway in the sites in which care is delivered: “There’s enormous pressure to get people out of the hospital and out of the emergency rooms,” said Dr. Decker, “And that’s not always better for patients.”

That shift to delivering care outside of the four walls of the hospital represents an opportunity for digitally savvy companies, many of whom may actually have little experience with health care delivery.

“Digital disruption is a sleeping giant that is easy to ignore, but you do that at your own peril. It’s happening in front of your eyes. My message today is: Figure out how you can move yourself further down the line.”

Chronic diseases, said Dr. Decker, “represent an opportunity for providers and health systems to leverage digital disruption.”

Overall, health care services contribute only to 10% of a patient’s health, said Dr. Decker, and are far overshadowed by individual health behaviors and social determinants of health. Is there a role for physicians to move beyond the clinic and hospital as partners in the digital disruption of health care? Yes, said Dr. Decker: “We’re not part of that aspect of a person’s life, and we need to be. ... I believe that providers have the right to be involved in other aspects of peoples’ lives to make them better, and yes, also to survive financially.”

said Dr. Decker. “Sixty percent of this country has a chronic disease. We as health care providers need to think differently about that.”

Changes are already well underway, with score upon score of startup companies developing apps that utilize smartphones and wearable devices to offer coaching, health education, and remote monitoring to consumers. “The barrier to entry is really low,” said Dr. Decker, with Silicon Valley already partnering with patients and payers to achieve digital monitoring and care delivery. But relatively few of these partnerships have actually involved physicians in building and executing the solutions they offer. “And that’s our fault, for not making sure we are part of this disruption,” he said.

Further, the evidence base for much of this monitoring and intervention is low. “There are some scathing articles on the level of evidence that these apps have – or don’t have,” said Dr. Becker. Physicians who get on board at the early stages of technology development could make a real difference, he said. “We could help them build the real evidence.”

Looping back to the current payer model, Dr. Decker asked, “Which pool of money is this coming from?” From the same pool of money that pays physicians, he said: “It’s coming off our backs.”

This isn’t a time when physicians can afford to wait and see how the digital health care landscape evolves, stressed Dr. Decker, making the subtle but important point that it’s hard to discern when you’re in the middle of disruptive change. Though the curve may appear relatively flat at the moment, he assured attendees that exponential growth in digital health care is already well underway.

Here is where early entry and user adoption are key: “Why do you think Facebook bought WhatsApp?” he asked. Though the messaging app, which has more than a billion users worldwide, is free now, eventual plans to charge WhatsApp users a dollar – or even less – per year will net Facebook staggering sums in the end, he said. Companies like Facebook “have figured out...the strength of exponential growth in a digital world,” he said.

All the building blocks are in place for physicians to begin contributing to health care’s digital disruption, said Dr. Decker. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid already have reimbursement codes for remote patient monitoring, for example. “Providers are being left out, and I think it’s our own fault.”

Dr. Decker reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – “The health care milieu is ripe for digital disruption,” said Anton Decker, MD. Speaking at the American Gastroenterological Association Partners in Value meeting, which was developed in partnership with the Digestive Health Physicians Association, he said that physicians need to become part of the disruption before it’s too late.

There’s no sign of improvement in worrisome trends in reimbursement, said Dr. Decker, president, international, at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. The megamerger trend that is bringing together ever-larger payers, pharmacy benefit managers, and hospital groups is just one manifestation of the trend toward consolidation that’s also seen in the airline industry, in financial services, and in telecommunications, he said.

“The math is not good on the payer and health systems side,” but for physicians, “There are ways to survive trends like this if we can move ourselves higher in the food chain.”

Other players in the health care space are figuring it out, he said. For example, the state of Ohio has five Medicaid plans; in 2018, aggregate profits for these plans were approximately 400 million dollars. Laying this profit figure against the backdrop of Medicare reimbursement rates for physician services makes it clear that “we have to figure out ways to survive this game,” he said.

“Health systems keep their lights on because of the hospital reimbursements – that pays for everything else,” said Dr. Decker, adding that payments from commercial insurers fill the coffers that, in turn, pay physicians who are employed by health systems. However, there’s a sea change underway in the sites in which care is delivered: “There’s enormous pressure to get people out of the hospital and out of the emergency rooms,” said Dr. Decker, “And that’s not always better for patients.”

That shift to delivering care outside of the four walls of the hospital represents an opportunity for digitally savvy companies, many of whom may actually have little experience with health care delivery.

“Digital disruption is a sleeping giant that is easy to ignore, but you do that at your own peril. It’s happening in front of your eyes. My message today is: Figure out how you can move yourself further down the line.”

Chronic diseases, said Dr. Decker, “represent an opportunity for providers and health systems to leverage digital disruption.”

Overall, health care services contribute only to 10% of a patient’s health, said Dr. Decker, and are far overshadowed by individual health behaviors and social determinants of health. Is there a role for physicians to move beyond the clinic and hospital as partners in the digital disruption of health care? Yes, said Dr. Decker: “We’re not part of that aspect of a person’s life, and we need to be. ... I believe that providers have the right to be involved in other aspects of peoples’ lives to make them better, and yes, also to survive financially.”

said Dr. Decker. “Sixty percent of this country has a chronic disease. We as health care providers need to think differently about that.”

Changes are already well underway, with score upon score of startup companies developing apps that utilize smartphones and wearable devices to offer coaching, health education, and remote monitoring to consumers. “The barrier to entry is really low,” said Dr. Decker, with Silicon Valley already partnering with patients and payers to achieve digital monitoring and care delivery. But relatively few of these partnerships have actually involved physicians in building and executing the solutions they offer. “And that’s our fault, for not making sure we are part of this disruption,” he said.

Further, the evidence base for much of this monitoring and intervention is low. “There are some scathing articles on the level of evidence that these apps have – or don’t have,” said Dr. Becker. Physicians who get on board at the early stages of technology development could make a real difference, he said. “We could help them build the real evidence.”

Looping back to the current payer model, Dr. Decker asked, “Which pool of money is this coming from?” From the same pool of money that pays physicians, he said: “It’s coming off our backs.”

This isn’t a time when physicians can afford to wait and see how the digital health care landscape evolves, stressed Dr. Decker, making the subtle but important point that it’s hard to discern when you’re in the middle of disruptive change. Though the curve may appear relatively flat at the moment, he assured attendees that exponential growth in digital health care is already well underway.

Here is where early entry and user adoption are key: “Why do you think Facebook bought WhatsApp?” he asked. Though the messaging app, which has more than a billion users worldwide, is free now, eventual plans to charge WhatsApp users a dollar – or even less – per year will net Facebook staggering sums in the end, he said. Companies like Facebook “have figured out...the strength of exponential growth in a digital world,” he said.

All the building blocks are in place for physicians to begin contributing to health care’s digital disruption, said Dr. Decker. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid already have reimbursement codes for remote patient monitoring, for example. “Providers are being left out, and I think it’s our own fault.”

Dr. Decker reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – “The health care milieu is ripe for digital disruption,” said Anton Decker, MD. Speaking at the American Gastroenterological Association Partners in Value meeting, which was developed in partnership with the Digestive Health Physicians Association, he said that physicians need to become part of the disruption before it’s too late.

There’s no sign of improvement in worrisome trends in reimbursement, said Dr. Decker, president, international, at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. The megamerger trend that is bringing together ever-larger payers, pharmacy benefit managers, and hospital groups is just one manifestation of the trend toward consolidation that’s also seen in the airline industry, in financial services, and in telecommunications, he said.

“The math is not good on the payer and health systems side,” but for physicians, “There are ways to survive trends like this if we can move ourselves higher in the food chain.”

Other players in the health care space are figuring it out, he said. For example, the state of Ohio has five Medicaid plans; in 2018, aggregate profits for these plans were approximately 400 million dollars. Laying this profit figure against the backdrop of Medicare reimbursement rates for physician services makes it clear that “we have to figure out ways to survive this game,” he said.

“Health systems keep their lights on because of the hospital reimbursements – that pays for everything else,” said Dr. Decker, adding that payments from commercial insurers fill the coffers that, in turn, pay physicians who are employed by health systems. However, there’s a sea change underway in the sites in which care is delivered: “There’s enormous pressure to get people out of the hospital and out of the emergency rooms,” said Dr. Decker, “And that’s not always better for patients.”

That shift to delivering care outside of the four walls of the hospital represents an opportunity for digitally savvy companies, many of whom may actually have little experience with health care delivery.

“Digital disruption is a sleeping giant that is easy to ignore, but you do that at your own peril. It’s happening in front of your eyes. My message today is: Figure out how you can move yourself further down the line.”

Chronic diseases, said Dr. Decker, “represent an opportunity for providers and health systems to leverage digital disruption.”

Overall, health care services contribute only to 10% of a patient’s health, said Dr. Decker, and are far overshadowed by individual health behaviors and social determinants of health. Is there a role for physicians to move beyond the clinic and hospital as partners in the digital disruption of health care? Yes, said Dr. Decker: “We’re not part of that aspect of a person’s life, and we need to be. ... I believe that providers have the right to be involved in other aspects of peoples’ lives to make them better, and yes, also to survive financially.”

said Dr. Decker. “Sixty percent of this country has a chronic disease. We as health care providers need to think differently about that.”

Changes are already well underway, with score upon score of startup companies developing apps that utilize smartphones and wearable devices to offer coaching, health education, and remote monitoring to consumers. “The barrier to entry is really low,” said Dr. Decker, with Silicon Valley already partnering with patients and payers to achieve digital monitoring and care delivery. But relatively few of these partnerships have actually involved physicians in building and executing the solutions they offer. “And that’s our fault, for not making sure we are part of this disruption,” he said.

Further, the evidence base for much of this monitoring and intervention is low. “There are some scathing articles on the level of evidence that these apps have – or don’t have,” said Dr. Becker. Physicians who get on board at the early stages of technology development could make a real difference, he said. “We could help them build the real evidence.”

Looping back to the current payer model, Dr. Decker asked, “Which pool of money is this coming from?” From the same pool of money that pays physicians, he said: “It’s coming off our backs.”

This isn’t a time when physicians can afford to wait and see how the digital health care landscape evolves, stressed Dr. Decker, making the subtle but important point that it’s hard to discern when you’re in the middle of disruptive change. Though the curve may appear relatively flat at the moment, he assured attendees that exponential growth in digital health care is already well underway.

Here is where early entry and user adoption are key: “Why do you think Facebook bought WhatsApp?” he asked. Though the messaging app, which has more than a billion users worldwide, is free now, eventual plans to charge WhatsApp users a dollar – or even less – per year will net Facebook staggering sums in the end, he said. Companies like Facebook “have figured out...the strength of exponential growth in a digital world,” he said.

All the building blocks are in place for physicians to begin contributing to health care’s digital disruption, said Dr. Decker. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid already have reimbursement codes for remote patient monitoring, for example. “Providers are being left out, and I think it’s our own fault.”

Dr. Decker reported that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AGA PARTNERS IN VALUE MEETING

Patients frequently drive too soon after ICD implantation

PARIS – Fewer than half of commercial drivers who received implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) recalled being told they should never drive professionally again, according to a recent Danish survey. Further, about a third of patients overall reported that they began driving soon after they received an ICD, during the period when guidelines recommend refraining from driving.

“These devices, they save lives – so what’s not to like?” lead investigator Jenny Bjerre, MD, asked at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. “Well, if you are a patient qualifying for an ICD, you also automatically qualify for some driving restrictions.” These are put in place because of the concern for an arrhythmia causing a loss of consciousness behind the wheel, she said.

A European consensus statement calls for a 3-month driving moratorium when an ICD is implanted for secondary prevention or after an appropriate ICD shock, and a 4-week restriction when an ICD is placed for primary prevention. All these restrictions apply to personal driver’s licenses; anyone with an ICD is permanently restricted from commercial driving according to the consensus statement, said Dr. Bjerre, of the University Hospital, Copenhagen.

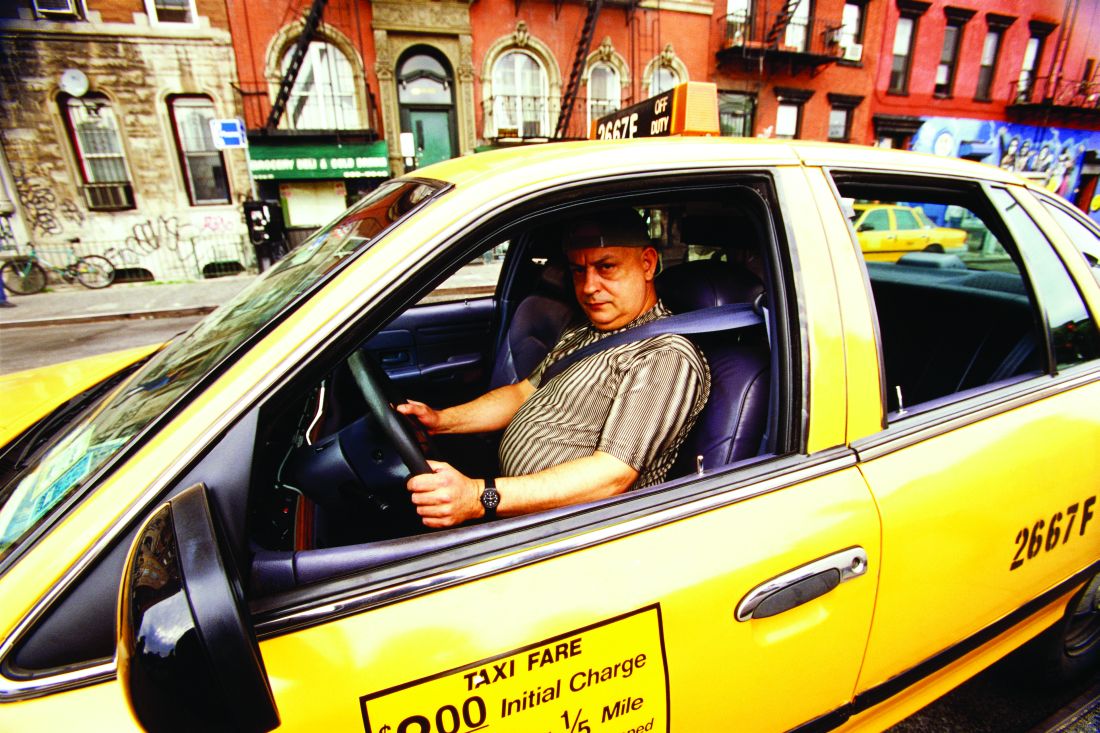

“As you can imagine, these restrictions are not that popular with the patients,” she said. She related the story of a patient, a taxi driver who had returned to a full range of physically taxing activities after his ICD implantation, but whose livelihood had been taken away from him.

Dr. Bjerre said she sought to understand the perspective of this patient, who said, “Sometimes I wish I hadn’t been resuscitated!” She saw that the loss of freedom and a meaningful occupation had profoundly affected the daily life of this patient, and she became curious about adherence to driving restrictions in patients with ICDs.

Using the nationwide Danish medical record database, Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues looked at a nationwide cohort of ICD patients to see they remembered hearing about restrictions on personal and commercial driving activities after ICD implantation. They also investigated adherence to restrictions, and sought to identify what factors were associated with nonadherence.

The questionnaire developed by Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues was made available to the ICD cohort both electronically and in a paper version. Questionnaires received were linked with a variety of nationwide registries through each participant’s unique national identification number, she explained. They obtained information about comorbidities, pharmacotherapies, and socioeconomic status. Not only did this linkage give more precise and complete data than would a questionnaire alone, but it also allowed the investigators to see how responders differed from nonresponders – important in questionnaire research, said Dr. Bjerre.

The investigators were able to locate and distribute questionnaires to a total of 3,913 living adults who had received first-time ICDs during the 3-year study period. In the end, even after excluding 31 responses for missing data, 2,741 responses were used for analysis – a response rate of over 70%.

The median age of respondents was 67, and 83% were male. About half – 46% – of respondents had an ICD implanted for primary prevention. Compared with those who did respond, said Dr. Bjerre, the nonresponders “were younger, sicker, more likely to be female, had lower socioeconomic status, and were less likely to be on guideline-directed therapy.”

Over 90% of respondents held a private driver’s license at the time of their ICD implantation, and just 7% were actively using a commercial license prior to implantation. Participants had a variety of commercial driving occupations, including driving trucks, buses, and taxis.

“Only 43% of primary prevention patients and 64% of secondary prevention patients stated that they had been informed about any driving restrictions,” said Dr. Bjerre. The figure was slightly better for patients after an ICD shock was delivered – 72% of these patients recalled hearing about driving restrictions.

“Among professional drivers – who are never supposed to drive again – only 45% said they had been informed about any professional driving restrictions,” she added.

What did patients report about their actual driving behaviors? Of patients receiving an ICD for primary prevention, 34% resumed driving within one week of ICD implantation. For those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention and those who had received an appropriate ICD shock, 43% and 30%, respectively, began driving before the recommended 3 months had elapsed.

The driving behavior of those with commercial licenses didn’t differ from the cohort as a whole: 35% of this group had resumed commercial driving.

In all the study’s subgroups, nonadherence to driving restrictions was more likely if the participant didn’t recall having been informed of the restrictions, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.34 for nonadherence. However, noted Dr. Bjerre, at least 20% of patients in all subgroups who said they’d been told not to drive still resumed driving in contravention of restrictions. “So it seems that information can’t explain everything,” she said.

Additional predictors of nonadherence included male sex, with an OR of 1.53, being the only driver in the household (OR 1.29), and being at least 60 years old (OR, 1.20). Those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention had an OR of 2.20 for nonadherence, as well.

The study had a large cohort of real-life ICD patients and the response rate was high, said Dr. Bjerre. However, there was a risk of recall bias; additionally, nonresponders differed from responders, limiting full generalizability of the data. Finally, she observed that participants may have given the answers they thought were socially desirable.

“I want to get back to our friend the taxi driver,” who was adherent to restrictions, but who kept wanting to know what the actual chances were that he’d harm someone if he resumed driving. Realizing she couldn’t give him a very precise answer, Dr. Bjerre concluded, “I do think we owe it to our patients to provide more evidence on the absolute risk of traffic accidents in these patients.”

Dr. Bjerre reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

PARIS – Fewer than half of commercial drivers who received implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) recalled being told they should never drive professionally again, according to a recent Danish survey. Further, about a third of patients overall reported that they began driving soon after they received an ICD, during the period when guidelines recommend refraining from driving.

“These devices, they save lives – so what’s not to like?” lead investigator Jenny Bjerre, MD, asked at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. “Well, if you are a patient qualifying for an ICD, you also automatically qualify for some driving restrictions.” These are put in place because of the concern for an arrhythmia causing a loss of consciousness behind the wheel, she said.

A European consensus statement calls for a 3-month driving moratorium when an ICD is implanted for secondary prevention or after an appropriate ICD shock, and a 4-week restriction when an ICD is placed for primary prevention. All these restrictions apply to personal driver’s licenses; anyone with an ICD is permanently restricted from commercial driving according to the consensus statement, said Dr. Bjerre, of the University Hospital, Copenhagen.

“As you can imagine, these restrictions are not that popular with the patients,” she said. She related the story of a patient, a taxi driver who had returned to a full range of physically taxing activities after his ICD implantation, but whose livelihood had been taken away from him.

Dr. Bjerre said she sought to understand the perspective of this patient, who said, “Sometimes I wish I hadn’t been resuscitated!” She saw that the loss of freedom and a meaningful occupation had profoundly affected the daily life of this patient, and she became curious about adherence to driving restrictions in patients with ICDs.

Using the nationwide Danish medical record database, Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues looked at a nationwide cohort of ICD patients to see they remembered hearing about restrictions on personal and commercial driving activities after ICD implantation. They also investigated adherence to restrictions, and sought to identify what factors were associated with nonadherence.

The questionnaire developed by Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues was made available to the ICD cohort both electronically and in a paper version. Questionnaires received were linked with a variety of nationwide registries through each participant’s unique national identification number, she explained. They obtained information about comorbidities, pharmacotherapies, and socioeconomic status. Not only did this linkage give more precise and complete data than would a questionnaire alone, but it also allowed the investigators to see how responders differed from nonresponders – important in questionnaire research, said Dr. Bjerre.

The investigators were able to locate and distribute questionnaires to a total of 3,913 living adults who had received first-time ICDs during the 3-year study period. In the end, even after excluding 31 responses for missing data, 2,741 responses were used for analysis – a response rate of over 70%.

The median age of respondents was 67, and 83% were male. About half – 46% – of respondents had an ICD implanted for primary prevention. Compared with those who did respond, said Dr. Bjerre, the nonresponders “were younger, sicker, more likely to be female, had lower socioeconomic status, and were less likely to be on guideline-directed therapy.”

Over 90% of respondents held a private driver’s license at the time of their ICD implantation, and just 7% were actively using a commercial license prior to implantation. Participants had a variety of commercial driving occupations, including driving trucks, buses, and taxis.

“Only 43% of primary prevention patients and 64% of secondary prevention patients stated that they had been informed about any driving restrictions,” said Dr. Bjerre. The figure was slightly better for patients after an ICD shock was delivered – 72% of these patients recalled hearing about driving restrictions.

“Among professional drivers – who are never supposed to drive again – only 45% said they had been informed about any professional driving restrictions,” she added.

What did patients report about their actual driving behaviors? Of patients receiving an ICD for primary prevention, 34% resumed driving within one week of ICD implantation. For those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention and those who had received an appropriate ICD shock, 43% and 30%, respectively, began driving before the recommended 3 months had elapsed.

The driving behavior of those with commercial licenses didn’t differ from the cohort as a whole: 35% of this group had resumed commercial driving.

In all the study’s subgroups, nonadherence to driving restrictions was more likely if the participant didn’t recall having been informed of the restrictions, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.34 for nonadherence. However, noted Dr. Bjerre, at least 20% of patients in all subgroups who said they’d been told not to drive still resumed driving in contravention of restrictions. “So it seems that information can’t explain everything,” she said.

Additional predictors of nonadherence included male sex, with an OR of 1.53, being the only driver in the household (OR 1.29), and being at least 60 years old (OR, 1.20). Those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention had an OR of 2.20 for nonadherence, as well.

The study had a large cohort of real-life ICD patients and the response rate was high, said Dr. Bjerre. However, there was a risk of recall bias; additionally, nonresponders differed from responders, limiting full generalizability of the data. Finally, she observed that participants may have given the answers they thought were socially desirable.

“I want to get back to our friend the taxi driver,” who was adherent to restrictions, but who kept wanting to know what the actual chances were that he’d harm someone if he resumed driving. Realizing she couldn’t give him a very precise answer, Dr. Bjerre concluded, “I do think we owe it to our patients to provide more evidence on the absolute risk of traffic accidents in these patients.”

Dr. Bjerre reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

PARIS – Fewer than half of commercial drivers who received implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) recalled being told they should never drive professionally again, according to a recent Danish survey. Further, about a third of patients overall reported that they began driving soon after they received an ICD, during the period when guidelines recommend refraining from driving.

“These devices, they save lives – so what’s not to like?” lead investigator Jenny Bjerre, MD, asked at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. “Well, if you are a patient qualifying for an ICD, you also automatically qualify for some driving restrictions.” These are put in place because of the concern for an arrhythmia causing a loss of consciousness behind the wheel, she said.

A European consensus statement calls for a 3-month driving moratorium when an ICD is implanted for secondary prevention or after an appropriate ICD shock, and a 4-week restriction when an ICD is placed for primary prevention. All these restrictions apply to personal driver’s licenses; anyone with an ICD is permanently restricted from commercial driving according to the consensus statement, said Dr. Bjerre, of the University Hospital, Copenhagen.

“As you can imagine, these restrictions are not that popular with the patients,” she said. She related the story of a patient, a taxi driver who had returned to a full range of physically taxing activities after his ICD implantation, but whose livelihood had been taken away from him.

Dr. Bjerre said she sought to understand the perspective of this patient, who said, “Sometimes I wish I hadn’t been resuscitated!” She saw that the loss of freedom and a meaningful occupation had profoundly affected the daily life of this patient, and she became curious about adherence to driving restrictions in patients with ICDs.

Using the nationwide Danish medical record database, Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues looked at a nationwide cohort of ICD patients to see they remembered hearing about restrictions on personal and commercial driving activities after ICD implantation. They also investigated adherence to restrictions, and sought to identify what factors were associated with nonadherence.

The questionnaire developed by Dr. Bjerre and her colleagues was made available to the ICD cohort both electronically and in a paper version. Questionnaires received were linked with a variety of nationwide registries through each participant’s unique national identification number, she explained. They obtained information about comorbidities, pharmacotherapies, and socioeconomic status. Not only did this linkage give more precise and complete data than would a questionnaire alone, but it also allowed the investigators to see how responders differed from nonresponders – important in questionnaire research, said Dr. Bjerre.

The investigators were able to locate and distribute questionnaires to a total of 3,913 living adults who had received first-time ICDs during the 3-year study period. In the end, even after excluding 31 responses for missing data, 2,741 responses were used for analysis – a response rate of over 70%.

The median age of respondents was 67, and 83% were male. About half – 46% – of respondents had an ICD implanted for primary prevention. Compared with those who did respond, said Dr. Bjerre, the nonresponders “were younger, sicker, more likely to be female, had lower socioeconomic status, and were less likely to be on guideline-directed therapy.”

Over 90% of respondents held a private driver’s license at the time of their ICD implantation, and just 7% were actively using a commercial license prior to implantation. Participants had a variety of commercial driving occupations, including driving trucks, buses, and taxis.

“Only 43% of primary prevention patients and 64% of secondary prevention patients stated that they had been informed about any driving restrictions,” said Dr. Bjerre. The figure was slightly better for patients after an ICD shock was delivered – 72% of these patients recalled hearing about driving restrictions.

“Among professional drivers – who are never supposed to drive again – only 45% said they had been informed about any professional driving restrictions,” she added.

What did patients report about their actual driving behaviors? Of patients receiving an ICD for primary prevention, 34% resumed driving within one week of ICD implantation. For those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention and those who had received an appropriate ICD shock, 43% and 30%, respectively, began driving before the recommended 3 months had elapsed.

The driving behavior of those with commercial licenses didn’t differ from the cohort as a whole: 35% of this group had resumed commercial driving.

In all the study’s subgroups, nonadherence to driving restrictions was more likely if the participant didn’t recall having been informed of the restrictions, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.34 for nonadherence. However, noted Dr. Bjerre, at least 20% of patients in all subgroups who said they’d been told not to drive still resumed driving in contravention of restrictions. “So it seems that information can’t explain everything,” she said.

Additional predictors of nonadherence included male sex, with an OR of 1.53, being the only driver in the household (OR 1.29), and being at least 60 years old (OR, 1.20). Those receiving an ICD for secondary prevention had an OR of 2.20 for nonadherence, as well.

The study had a large cohort of real-life ICD patients and the response rate was high, said Dr. Bjerre. However, there was a risk of recall bias; additionally, nonresponders differed from responders, limiting full generalizability of the data. Finally, she observed that participants may have given the answers they thought were socially desirable.

“I want to get back to our friend the taxi driver,” who was adherent to restrictions, but who kept wanting to know what the actual chances were that he’d harm someone if he resumed driving. Realizing she couldn’t give him a very precise answer, Dr. Bjerre concluded, “I do think we owe it to our patients to provide more evidence on the absolute risk of traffic accidents in these patients.”

Dr. Bjerre reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM ESC CONGRESS 2019

Cancer overtakes CVD as cause of death in high-income countries

PARIS – Though cardiovascular disease still accounts for 40% of deaths around the world, , according to new data from a global prospective study.

“Cancer deaths are becoming more frequent not because the rates of death from cancer are going up, but because we have decreased the deaths from cardiovascular disease,” said the study’s senior author, Salim Yusuf, MD, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

A striking pattern emerged when cause of death was stratified by country income level, said fellow investigator Darryl P. Leong, MBBS, in presenting data regarding shifting global mortality patterns. Fully 55% of deaths in high-income nations were caused by cancer, compared with 30% in middle-income countries and 15% in low-income countries. In high-income countries, by contrast, cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the cause of death 23% of the time, while that figure was 42% and 43% for middle- and low-income countries, respectively.

Looking at the data slightly differently, the ratio of cardiovascular deaths to cancer deaths for high-income countries is 0.4; for middle-income countries, the ratio is 1.3, and “One is threefold more likely to die from cardiovascular disease as from cancer” in low-income countries, said Dr. Leong. Although the United States is not included in the PURE study, “recent data shows that some states in the U.S. also have higher cancer mortality than cardiovascular disease. This is a success story,” said Dr. Yusuf, since the shift is largely attributable to decreased mortality from CVD.

Dr. Leong and Dr. Yusuf each presented results from the PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) study, which has enrolled a total of 202,000 individuals from 27 countries on every inhabited continent but Australia. Follow-up data are available for 167,000 individuals in 21 countries. Canada, Russia, China, India, Brazil, and Chile are among the most populous national that are included. Their findings were published simultaneously in the Lancet with the congress presentations (2019 Sep 3; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2 and doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32007-0).

The INTERHEART risk score, an integrated cardiovascular risk score that uses non-laboratory values such as age, smoking status, family history, and comorbidities, was calculated for all participants. “We observed that the highest predicted cardiovascular risk is in high-income countries, and the lowest, in low-income countries,” said Dr. Leong, a cardiologist at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Over the study period, 11,307 deaths occurred. Over 9,000 incident cardiovascular events were observed, as were over 5,000 new cancers.

“We have some interesting observations from these data,” said Dr. Leong. “Firstly, there is a gradient in the cardiovascular disease rates, moving from lowest in high-income countries – despite the fact that their INTERHEART risk score was highest – through to highest incident cardiovascular disease in low-income countries, despite their INTERHEART risk score being lowest.” This difference, said Dr. Leong, was driven by higher myocardial infarction rates in low-income countries and higher stroke rates in middle-income countries, when compared to high-income countries.

Once a participant was subject to one of the incident diseases, though, the patterns shifted. For CVD, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, and injury, the likelihood of death within 1 year was highest in low-income countries – markedly higher, in the case of CVD. For all conditions, the one-year case-fatality rate after the occurrence of an incident disease was lowest in high-income countries.

“So we are seeing a new transition,” said Dr. Yusuf, the executive director of the Population Health Research Institute and Distinguished University Professor of Medicine, McMaster University, both in Hamilton, Ont. “The old transition was infectious diseases giving way to noncommunicable diseases. Now we are seeing a transition within noncommunicable diseases: In rich countries, cardiovascular disease is going down, perhaps due to better prevention, but I think even more importantly, due to better treatments.

“I want to hasten to add that the difference in risk between high-, middle-, and low-income countries in cardiovascular disease is not due to risk factors,” he went on. “Risk factors, if anything, are lower in the poor countries, compared to the higher-income countries.”

The shift away from cardiovascular disease mortality toward cancer mortality is also occurring in some countries that are in the upper tier of middle-income nations, including Chile, Argentina, Turkey, and Poland, said Dr. Yusuf, who presented data regarding the relative contributions of risk factors to cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the PURE study were expressed by a measure called the population attributable fraction (PAF) that captures both the hazard ratio for a particular risk factor and the prevalence of the risk factor, explained Dr. Yusuf. “Hypertension, by far, was the biggest risk factor of cardiovascular disease globally,” he added, noting that the PAF for hypertension was over 20%. Hypertension far outstripped the next most significant risk factor, high non-HDL cholesterol, which had a PAF of less than 10%.

“This was a big surprise to us: Household pollution was a big factor,” said Dr. Yusuf, who later added that particulate matter from cooking, particularly with solid fuels such as wood or charcoal, was likely the source of much household air pollution, “a big problem in middle- and low-income countries.”

Tobacco usage is decreasing, as is its contribution to cardiovascular deaths, but other commonly cited culprits for cardiovascular disease were not significant contributors to cardiovascular disease in the PURE population.

“Abdominal obesity, and not BMI” contributes to cardiovascular risk. “BMI is not a good indicator of risk,” said Dr. Yusuf in a video interview. These results were presented separately at the congress.

“Grip strength is important; in fact, it is more important than low physical activity. People have focused on physical activity – how much you do. But strength seems to be more important…We haven’t focused on the importance of strength in the past.”

“Salt doesn’t figure in at all; salt has been exaggerated as a risk factor,” said Dr. Yusuf. “Diet needs to be rethought,” and conventional thinking challenged, he added, noting that consumption of full-fat dairy, nuts, and a moderate amount of meat all were protective among the PURE cohort.

Looking next at factors contributing to mortality in the global PURE population, low educational level had the highest attributable fraction of mortality of any single risk factor, at about 12%. “This has been ignored,” said Dr. Yusuf. “In most epidemiological studies, it’s been used as a covariate, or a stratifier,” rather than addressing low education itself as a risk factor, he said.

Tobacco use, low grip strength, and poor diet all had attributable fractions of just over 10%, said Dr. Yusuf, again noting that it wasn’t fat or meat consumption that made for the riskiest diet.

Overall, metabolic risk factors accounted for the largest fraction of risk of cardiovascular disease in the PURE population, with behavioral risk factors such as alcohol and tobacco use coming next. This held true across all income categories. However, in higher income nations where environmental factors and household air pollution are lower contributors to cardiovascular disease, metabolic and behavioral risk factors contributed more to cardiovascular disease risk.

Global differences in cardiovascular disease rates, stressed Dr. Yusuf, are not primarily attributable to metabolic risk factors. “The [World Health Organization] has focused on risk factors and has not focused on improved health care. Health care matters, and it matters in a big way.”

Adults aged 35-70 were recruited from 4 high-, 12 middle- and 5 low-income countries for PURE, and followed for a median 9.5 years. Cardiovascular disease and other health events salient to the study were documented both through direct contact and administrative record review, said Dr. Leong, and data about cardiovascular events and vital status were known for well over 90% of study participants.

Slightly less than half of participants were male, and over 108,000 participants were from middle income countries.

The PURE study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Ontaario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi-Aentis, Servier Laboratories, and Glaxo Smith Kline. The study also received additional support in individual participating countries. Dr. Yusuf and Dr. Leon reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

PARIS – Though cardiovascular disease still accounts for 40% of deaths around the world, , according to new data from a global prospective study.

“Cancer deaths are becoming more frequent not because the rates of death from cancer are going up, but because we have decreased the deaths from cardiovascular disease,” said the study’s senior author, Salim Yusuf, MD, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

A striking pattern emerged when cause of death was stratified by country income level, said fellow investigator Darryl P. Leong, MBBS, in presenting data regarding shifting global mortality patterns. Fully 55% of deaths in high-income nations were caused by cancer, compared with 30% in middle-income countries and 15% in low-income countries. In high-income countries, by contrast, cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the cause of death 23% of the time, while that figure was 42% and 43% for middle- and low-income countries, respectively.

Looking at the data slightly differently, the ratio of cardiovascular deaths to cancer deaths for high-income countries is 0.4; for middle-income countries, the ratio is 1.3, and “One is threefold more likely to die from cardiovascular disease as from cancer” in low-income countries, said Dr. Leong. Although the United States is not included in the PURE study, “recent data shows that some states in the U.S. also have higher cancer mortality than cardiovascular disease. This is a success story,” said Dr. Yusuf, since the shift is largely attributable to decreased mortality from CVD.

Dr. Leong and Dr. Yusuf each presented results from the PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) study, which has enrolled a total of 202,000 individuals from 27 countries on every inhabited continent but Australia. Follow-up data are available for 167,000 individuals in 21 countries. Canada, Russia, China, India, Brazil, and Chile are among the most populous national that are included. Their findings were published simultaneously in the Lancet with the congress presentations (2019 Sep 3; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2 and doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32007-0).

The INTERHEART risk score, an integrated cardiovascular risk score that uses non-laboratory values such as age, smoking status, family history, and comorbidities, was calculated for all participants. “We observed that the highest predicted cardiovascular risk is in high-income countries, and the lowest, in low-income countries,” said Dr. Leong, a cardiologist at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Over the study period, 11,307 deaths occurred. Over 9,000 incident cardiovascular events were observed, as were over 5,000 new cancers.

“We have some interesting observations from these data,” said Dr. Leong. “Firstly, there is a gradient in the cardiovascular disease rates, moving from lowest in high-income countries – despite the fact that their INTERHEART risk score was highest – through to highest incident cardiovascular disease in low-income countries, despite their INTERHEART risk score being lowest.” This difference, said Dr. Leong, was driven by higher myocardial infarction rates in low-income countries and higher stroke rates in middle-income countries, when compared to high-income countries.

Once a participant was subject to one of the incident diseases, though, the patterns shifted. For CVD, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, and injury, the likelihood of death within 1 year was highest in low-income countries – markedly higher, in the case of CVD. For all conditions, the one-year case-fatality rate after the occurrence of an incident disease was lowest in high-income countries.

“So we are seeing a new transition,” said Dr. Yusuf, the executive director of the Population Health Research Institute and Distinguished University Professor of Medicine, McMaster University, both in Hamilton, Ont. “The old transition was infectious diseases giving way to noncommunicable diseases. Now we are seeing a transition within noncommunicable diseases: In rich countries, cardiovascular disease is going down, perhaps due to better prevention, but I think even more importantly, due to better treatments.

“I want to hasten to add that the difference in risk between high-, middle-, and low-income countries in cardiovascular disease is not due to risk factors,” he went on. “Risk factors, if anything, are lower in the poor countries, compared to the higher-income countries.”

The shift away from cardiovascular disease mortality toward cancer mortality is also occurring in some countries that are in the upper tier of middle-income nations, including Chile, Argentina, Turkey, and Poland, said Dr. Yusuf, who presented data regarding the relative contributions of risk factors to cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the PURE study were expressed by a measure called the population attributable fraction (PAF) that captures both the hazard ratio for a particular risk factor and the prevalence of the risk factor, explained Dr. Yusuf. “Hypertension, by far, was the biggest risk factor of cardiovascular disease globally,” he added, noting that the PAF for hypertension was over 20%. Hypertension far outstripped the next most significant risk factor, high non-HDL cholesterol, which had a PAF of less than 10%.

“This was a big surprise to us: Household pollution was a big factor,” said Dr. Yusuf, who later added that particulate matter from cooking, particularly with solid fuels such as wood or charcoal, was likely the source of much household air pollution, “a big problem in middle- and low-income countries.”

Tobacco usage is decreasing, as is its contribution to cardiovascular deaths, but other commonly cited culprits for cardiovascular disease were not significant contributors to cardiovascular disease in the PURE population.

“Abdominal obesity, and not BMI” contributes to cardiovascular risk. “BMI is not a good indicator of risk,” said Dr. Yusuf in a video interview. These results were presented separately at the congress.

“Grip strength is important; in fact, it is more important than low physical activity. People have focused on physical activity – how much you do. But strength seems to be more important…We haven’t focused on the importance of strength in the past.”

“Salt doesn’t figure in at all; salt has been exaggerated as a risk factor,” said Dr. Yusuf. “Diet needs to be rethought,” and conventional thinking challenged, he added, noting that consumption of full-fat dairy, nuts, and a moderate amount of meat all were protective among the PURE cohort.

Looking next at factors contributing to mortality in the global PURE population, low educational level had the highest attributable fraction of mortality of any single risk factor, at about 12%. “This has been ignored,” said Dr. Yusuf. “In most epidemiological studies, it’s been used as a covariate, or a stratifier,” rather than addressing low education itself as a risk factor, he said.

Tobacco use, low grip strength, and poor diet all had attributable fractions of just over 10%, said Dr. Yusuf, again noting that it wasn’t fat or meat consumption that made for the riskiest diet.

Overall, metabolic risk factors accounted for the largest fraction of risk of cardiovascular disease in the PURE population, with behavioral risk factors such as alcohol and tobacco use coming next. This held true across all income categories. However, in higher income nations where environmental factors and household air pollution are lower contributors to cardiovascular disease, metabolic and behavioral risk factors contributed more to cardiovascular disease risk.

Global differences in cardiovascular disease rates, stressed Dr. Yusuf, are not primarily attributable to metabolic risk factors. “The [World Health Organization] has focused on risk factors and has not focused on improved health care. Health care matters, and it matters in a big way.”

Adults aged 35-70 were recruited from 4 high-, 12 middle- and 5 low-income countries for PURE, and followed for a median 9.5 years. Cardiovascular disease and other health events salient to the study were documented both through direct contact and administrative record review, said Dr. Leong, and data about cardiovascular events and vital status were known for well over 90% of study participants.

Slightly less than half of participants were male, and over 108,000 participants were from middle income countries.

The PURE study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Ontaario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi-Aentis, Servier Laboratories, and Glaxo Smith Kline. The study also received additional support in individual participating countries. Dr. Yusuf and Dr. Leon reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

PARIS – Though cardiovascular disease still accounts for 40% of deaths around the world, , according to new data from a global prospective study.

“Cancer deaths are becoming more frequent not because the rates of death from cancer are going up, but because we have decreased the deaths from cardiovascular disease,” said the study’s senior author, Salim Yusuf, MD, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

A striking pattern emerged when cause of death was stratified by country income level, said fellow investigator Darryl P. Leong, MBBS, in presenting data regarding shifting global mortality patterns. Fully 55% of deaths in high-income nations were caused by cancer, compared with 30% in middle-income countries and 15% in low-income countries. In high-income countries, by contrast, cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the cause of death 23% of the time, while that figure was 42% and 43% for middle- and low-income countries, respectively.

Looking at the data slightly differently, the ratio of cardiovascular deaths to cancer deaths for high-income countries is 0.4; for middle-income countries, the ratio is 1.3, and “One is threefold more likely to die from cardiovascular disease as from cancer” in low-income countries, said Dr. Leong. Although the United States is not included in the PURE study, “recent data shows that some states in the U.S. also have higher cancer mortality than cardiovascular disease. This is a success story,” said Dr. Yusuf, since the shift is largely attributable to decreased mortality from CVD.

Dr. Leong and Dr. Yusuf each presented results from the PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) study, which has enrolled a total of 202,000 individuals from 27 countries on every inhabited continent but Australia. Follow-up data are available for 167,000 individuals in 21 countries. Canada, Russia, China, India, Brazil, and Chile are among the most populous national that are included. Their findings were published simultaneously in the Lancet with the congress presentations (2019 Sep 3; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2 and doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32007-0).

The INTERHEART risk score, an integrated cardiovascular risk score that uses non-laboratory values such as age, smoking status, family history, and comorbidities, was calculated for all participants. “We observed that the highest predicted cardiovascular risk is in high-income countries, and the lowest, in low-income countries,” said Dr. Leong, a cardiologist at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, both in Hamilton, Ont.

Over the study period, 11,307 deaths occurred. Over 9,000 incident cardiovascular events were observed, as were over 5,000 new cancers.

“We have some interesting observations from these data,” said Dr. Leong. “Firstly, there is a gradient in the cardiovascular disease rates, moving from lowest in high-income countries – despite the fact that their INTERHEART risk score was highest – through to highest incident cardiovascular disease in low-income countries, despite their INTERHEART risk score being lowest.” This difference, said Dr. Leong, was driven by higher myocardial infarction rates in low-income countries and higher stroke rates in middle-income countries, when compared to high-income countries.

Once a participant was subject to one of the incident diseases, though, the patterns shifted. For CVD, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, and injury, the likelihood of death within 1 year was highest in low-income countries – markedly higher, in the case of CVD. For all conditions, the one-year case-fatality rate after the occurrence of an incident disease was lowest in high-income countries.

“So we are seeing a new transition,” said Dr. Yusuf, the executive director of the Population Health Research Institute and Distinguished University Professor of Medicine, McMaster University, both in Hamilton, Ont. “The old transition was infectious diseases giving way to noncommunicable diseases. Now we are seeing a transition within noncommunicable diseases: In rich countries, cardiovascular disease is going down, perhaps due to better prevention, but I think even more importantly, due to better treatments.

“I want to hasten to add that the difference in risk between high-, middle-, and low-income countries in cardiovascular disease is not due to risk factors,” he went on. “Risk factors, if anything, are lower in the poor countries, compared to the higher-income countries.”

The shift away from cardiovascular disease mortality toward cancer mortality is also occurring in some countries that are in the upper tier of middle-income nations, including Chile, Argentina, Turkey, and Poland, said Dr. Yusuf, who presented data regarding the relative contributions of risk factors to cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the PURE study were expressed by a measure called the population attributable fraction (PAF) that captures both the hazard ratio for a particular risk factor and the prevalence of the risk factor, explained Dr. Yusuf. “Hypertension, by far, was the biggest risk factor of cardiovascular disease globally,” he added, noting that the PAF for hypertension was over 20%. Hypertension far outstripped the next most significant risk factor, high non-HDL cholesterol, which had a PAF of less than 10%.

“This was a big surprise to us: Household pollution was a big factor,” said Dr. Yusuf, who later added that particulate matter from cooking, particularly with solid fuels such as wood or charcoal, was likely the source of much household air pollution, “a big problem in middle- and low-income countries.”

Tobacco usage is decreasing, as is its contribution to cardiovascular deaths, but other commonly cited culprits for cardiovascular disease were not significant contributors to cardiovascular disease in the PURE population.

“Abdominal obesity, and not BMI” contributes to cardiovascular risk. “BMI is not a good indicator of risk,” said Dr. Yusuf in a video interview. These results were presented separately at the congress.

“Grip strength is important; in fact, it is more important than low physical activity. People have focused on physical activity – how much you do. But strength seems to be more important…We haven’t focused on the importance of strength in the past.”

“Salt doesn’t figure in at all; salt has been exaggerated as a risk factor,” said Dr. Yusuf. “Diet needs to be rethought,” and conventional thinking challenged, he added, noting that consumption of full-fat dairy, nuts, and a moderate amount of meat all were protective among the PURE cohort.

Looking next at factors contributing to mortality in the global PURE population, low educational level had the highest attributable fraction of mortality of any single risk factor, at about 12%. “This has been ignored,” said Dr. Yusuf. “In most epidemiological studies, it’s been used as a covariate, or a stratifier,” rather than addressing low education itself as a risk factor, he said.

Tobacco use, low grip strength, and poor diet all had attributable fractions of just over 10%, said Dr. Yusuf, again noting that it wasn’t fat or meat consumption that made for the riskiest diet.

Overall, metabolic risk factors accounted for the largest fraction of risk of cardiovascular disease in the PURE population, with behavioral risk factors such as alcohol and tobacco use coming next. This held true across all income categories. However, in higher income nations where environmental factors and household air pollution are lower contributors to cardiovascular disease, metabolic and behavioral risk factors contributed more to cardiovascular disease risk.

Global differences in cardiovascular disease rates, stressed Dr. Yusuf, are not primarily attributable to metabolic risk factors. “The [World Health Organization] has focused on risk factors and has not focused on improved health care. Health care matters, and it matters in a big way.”

Adults aged 35-70 were recruited from 4 high-, 12 middle- and 5 low-income countries for PURE, and followed for a median 9.5 years. Cardiovascular disease and other health events salient to the study were documented both through direct contact and administrative record review, said Dr. Leong, and data about cardiovascular events and vital status were known for well over 90% of study participants.

Slightly less than half of participants were male, and over 108,000 participants were from middle income countries.

The PURE study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Ontaario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi-Aentis, Servier Laboratories, and Glaxo Smith Kline. The study also received additional support in individual participating countries. Dr. Yusuf and Dr. Leon reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM ESC CONGRESS 2019

GALACTIC: Early vasodilation strategy no help in acute heart failure

PARIS – A practical strategy of early and aggressive vasodilation and optimization of long-term medication for acute heart failure did not budge all-cause mortality or 180-day readmission rates, according to results of a pragmatic trial presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“To our great disappointment, the curves were superimposable” between intervention and control arms in the GALACTIC (Goal-directed Afterload Reduction in Acute Congestive Cardiac Decompensation) trial, said lead investigator Christian Eugen Mueller, MD. “There was no signal of a benefit” for those receiving the targeted intervention: the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.07 for the composite primary endpoint of all-cause mortality or 6-month readmission for acute heart failure (P = 0.59).

GALACTIC, explained Dr. Mueller, was the largest investigator-initiated, randomized, controlled trial of pharmacologic therapy for acute heart failure (AHF).

“It is different in that it did not investigate a single drug, but a strategy of early, intensive, and sustained vasodilation. It is also unique in that it used individual doses of well-characterized, widely available, and mostly inexpensive drugs,” said Dr. Mueller, director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute at the University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland. “So this would have the beauty that, if it has a positive finding, you – in whatever country you come from – would be immediately able to apply it once you’re back home in your institution.”

The study attempted to address the gap between symptom amelioration and long-term outcomes when patients arrive in the ED with AHF. “Despite symptomatic improvement achieved from loop diuretics, mortality and morbidity remain unacceptably high,” said Dr. Mueller, with 40%-50% of AHF patients experiencing rehospitalization or death within 180 days of discharge.

Much remains unknown about the optimal treatment strategy for AHF. Aggressive vasodilation has been shown to improve outcomes in less-severe AHF, and intravenous nitrates are known to improve outcomes in AHF where severe pulmonary edema is present – “a phenotype representing only about 5% of patients,” noted Dr. Mueller. Still, “it is unknown whether aggressive vasodilation also improves outcomes in the much more common less-severe phenotype.”

Also, previous trials that ran intravenous vasodilators at a fixed dose for 48 hours did not improve AHF outcomes, so a one-size-fits-all strategy was not one the GALACTIC investigators sought to pursue.

In addition to a flexible regimen, “any strategy applied needs to take into consideration that the vast majority of patients with acute heart failure, after initial treatment in the ED, are then treated in a general cardiology ward,” added Dr. Mueller.

This meant that intravenous nitrate infusion was not part of the GALACTIC trial; rather, sublingual and transdermal nitrates were used, explained Dr. Mueller. “Transdermal application has the beauty that if you have an adverse effect – and hypotension is the most dangerous one – you can immediately remove the patch, and thereby avoid any further harm.”

The two-part strategy tested in GALACTIC involved reducing cardiac filling pressures by maintaining or increasing organ perfusion, while also increasing “long-term lifesaving therapy” targeting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system during hospitalization, with a goal to continue optimal treatment long term.

ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers were added on the second day of hospitalization for the intervention group, said Dr. Mueller, and “in the ideal setting, up-titrated very aggressively from day to day.

“However, as you know, up-titration to target dose is sometimes wishful thinking in this frail population,” he said, so the GALACTIC trial protocol included a scheme to back dosing off for hypotension, hypokalemia, or worsening renal function. Systolic BP guided how aggressively vasodilation and ACE inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker therapy were escalated.

In the end, 382 patients randomized to the intervention arm received early, intensive, and sustained vasodilation, and the 399 patients in the control arm received standard-of-care treatment according to ESC guidelines. These figures omit two patients in the standard-of-care arm who withdrew consent, but follow-up was otherwise complete, said Dr. Mueller. Physicians treating patients in both study arms had discretion to use such other therapies as loop diuretics, beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and cardiac devices.

Adult patients coming to the ED with acute dyspnea classified as New York Heart Association class III or IV were eligible if they had brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels of at least 500 ng/L, or N-terminal of the prohormone BNP (NT-proBNP) levels of at least 2,000 ng/L.

Overall, patients enrolled in GALACTIC were in their late 70s, and women made up 37% of the population.

The actual median BNP for enrollees was about 1,250 ng/L, and the median NT-proBNP was just under 6,000 ng/L. The median left ventricular ejection fraction was 37%. About a third of patients had diabetes, and 85% had hypertension. Over half had known chronic heart failure, about a third had prior history of MI, and half of patients had atrial fibrillation at baseline.

“Signs of congestion were present in all patients, and over 90% had rales on physical examination,” said Dr. Mueller.

Patients who were destined for the ICU, those who had systolic BP below 100 mm Hg or marked creatinine elevation, or who required cardiopulmonary resuscitation were excluded. Also excluded were patients with known structural defects such as severe valvular stenosis, congenital heart disease, or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. GALACTIC also excluded patients with isolated right ventricular failure caused by pulmonary hypertension.

Prespecified subgroup analyses compared women with men, and those younger than 75 years with older participants. Women saw a significantly higher hazard ratio for readmission or death, indicating a potential harm from the intervention, said Dr. Mueller. An additional analysis stratified patients by left ventricular ejection fraction. Aside from the intervention’s negative effect on women participating in the trial, no other subgroups benefited or were harmed by an early vasodilation strategy.

Alexandre Mebazaa, MD, the designated discussant for the presentation, said that, although the GALACTIC trial was neutral, it represents “an important step forward in acute heart failure.

“Congratulations: First, because we know that in the critically ill condition it’s very difficult to do trials,” and the GALACTIC investigators succeeded in enrolling patients within the first 5 hours of presentation to EDs, noted Dr. Mebazaa, professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at the Paris Diderot School of Medicine.

He added that GALACTIC succeeded in continuing vasodilator use beyond the 48-hour mark. “For the first time, you had the courage to go a little bit further down, and we see that patients got the drug with vasodilator properties for 2 days or more.”

However, the long recruitment period for GALACTIC – first enrollment began in 2007 – meant that the study design reflected a thought process about AHF that doesn’t necessarily reflect current practice, noted Dr. Mebazaa. “The trial was designed many years ago, and at that time, we were still thinking that giving very aggressive treatment in the first hours could have an impact.

“Now, when we will be treating patients with vasodilators with acute heart failure – at least myself and my group – I would really wonder whether there is still evidence in the world to support the use of those agents.”

Dr. Mueller noted limitations of the GALACTIC trial, including the lack of generalizability to patients with systolic hypotension or severe renal dysfunction, since these populations were excluded. Also, “the open-label design, which was mandated by the aim to test a strategy, not a single drug, may have introduced a bias in the unblinded assessment of dyspnea” during inpatient stay.

The study was funded by several Swiss research institutions and had no industry support. Dr. Mueller reported no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Mebazaa reported financial relationships with Roche, Service, Novartis, AstraZeneca, S-Form Pharma, 4Teen$4, Adrenomed, and Sphingotec.

SOURCE: Mueller C. ESC 2019, Hot Line Session 3.

PARIS – A practical strategy of early and aggressive vasodilation and optimization of long-term medication for acute heart failure did not budge all-cause mortality or 180-day readmission rates, according to results of a pragmatic trial presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“To our great disappointment, the curves were superimposable” between intervention and control arms in the GALACTIC (Goal-directed Afterload Reduction in Acute Congestive Cardiac Decompensation) trial, said lead investigator Christian Eugen Mueller, MD. “There was no signal of a benefit” for those receiving the targeted intervention: the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.07 for the composite primary endpoint of all-cause mortality or 6-month readmission for acute heart failure (P = 0.59).

GALACTIC, explained Dr. Mueller, was the largest investigator-initiated, randomized, controlled trial of pharmacologic therapy for acute heart failure (AHF).

“It is different in that it did not investigate a single drug, but a strategy of early, intensive, and sustained vasodilation. It is also unique in that it used individual doses of well-characterized, widely available, and mostly inexpensive drugs,” said Dr. Mueller, director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute at the University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland. “So this would have the beauty that, if it has a positive finding, you – in whatever country you come from – would be immediately able to apply it once you’re back home in your institution.”

The study attempted to address the gap between symptom amelioration and long-term outcomes when patients arrive in the ED with AHF. “Despite symptomatic improvement achieved from loop diuretics, mortality and morbidity remain unacceptably high,” said Dr. Mueller, with 40%-50% of AHF patients experiencing rehospitalization or death within 180 days of discharge.

Much remains unknown about the optimal treatment strategy for AHF. Aggressive vasodilation has been shown to improve outcomes in less-severe AHF, and intravenous nitrates are known to improve outcomes in AHF where severe pulmonary edema is present – “a phenotype representing only about 5% of patients,” noted Dr. Mueller. Still, “it is unknown whether aggressive vasodilation also improves outcomes in the much more common less-severe phenotype.”

Also, previous trials that ran intravenous vasodilators at a fixed dose for 48 hours did not improve AHF outcomes, so a one-size-fits-all strategy was not one the GALACTIC investigators sought to pursue.

In addition to a flexible regimen, “any strategy applied needs to take into consideration that the vast majority of patients with acute heart failure, after initial treatment in the ED, are then treated in a general cardiology ward,” added Dr. Mueller.

This meant that intravenous nitrate infusion was not part of the GALACTIC trial; rather, sublingual and transdermal nitrates were used, explained Dr. Mueller. “Transdermal application has the beauty that if you have an adverse effect – and hypotension is the most dangerous one – you can immediately remove the patch, and thereby avoid any further harm.”

The two-part strategy tested in GALACTIC involved reducing cardiac filling pressures by maintaining or increasing organ perfusion, while also increasing “long-term lifesaving therapy” targeting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system during hospitalization, with a goal to continue optimal treatment long term.

ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers were added on the second day of hospitalization for the intervention group, said Dr. Mueller, and “in the ideal setting, up-titrated very aggressively from day to day.

“However, as you know, up-titration to target dose is sometimes wishful thinking in this frail population,” he said, so the GALACTIC trial protocol included a scheme to back dosing off for hypotension, hypokalemia, or worsening renal function. Systolic BP guided how aggressively vasodilation and ACE inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker therapy were escalated.

In the end, 382 patients randomized to the intervention arm received early, intensive, and sustained vasodilation, and the 399 patients in the control arm received standard-of-care treatment according to ESC guidelines. These figures omit two patients in the standard-of-care arm who withdrew consent, but follow-up was otherwise complete, said Dr. Mueller. Physicians treating patients in both study arms had discretion to use such other therapies as loop diuretics, beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and cardiac devices.

Adult patients coming to the ED with acute dyspnea classified as New York Heart Association class III or IV were eligible if they had brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels of at least 500 ng/L, or N-terminal of the prohormone BNP (NT-proBNP) levels of at least 2,000 ng/L.

Overall, patients enrolled in GALACTIC were in their late 70s, and women made up 37% of the population.

The actual median BNP for enrollees was about 1,250 ng/L, and the median NT-proBNP was just under 6,000 ng/L. The median left ventricular ejection fraction was 37%. About a third of patients had diabetes, and 85% had hypertension. Over half had known chronic heart failure, about a third had prior history of MI, and half of patients had atrial fibrillation at baseline.

“Signs of congestion were present in all patients, and over 90% had rales on physical examination,” said Dr. Mueller.

Patients who were destined for the ICU, those who had systolic BP below 100 mm Hg or marked creatinine elevation, or who required cardiopulmonary resuscitation were excluded. Also excluded were patients with known structural defects such as severe valvular stenosis, congenital heart disease, or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. GALACTIC also excluded patients with isolated right ventricular failure caused by pulmonary hypertension.

Prespecified subgroup analyses compared women with men, and those younger than 75 years with older participants. Women saw a significantly higher hazard ratio for readmission or death, indicating a potential harm from the intervention, said Dr. Mueller. An additional analysis stratified patients by left ventricular ejection fraction. Aside from the intervention’s negative effect on women participating in the trial, no other subgroups benefited or were harmed by an early vasodilation strategy.

Alexandre Mebazaa, MD, the designated discussant for the presentation, said that, although the GALACTIC trial was neutral, it represents “an important step forward in acute heart failure.

“Congratulations: First, because we know that in the critically ill condition it’s very difficult to do trials,” and the GALACTIC investigators succeeded in enrolling patients within the first 5 hours of presentation to EDs, noted Dr. Mebazaa, professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at the Paris Diderot School of Medicine.

He added that GALACTIC succeeded in continuing vasodilator use beyond the 48-hour mark. “For the first time, you had the courage to go a little bit further down, and we see that patients got the drug with vasodilator properties for 2 days or more.”

However, the long recruitment period for GALACTIC – first enrollment began in 2007 – meant that the study design reflected a thought process about AHF that doesn’t necessarily reflect current practice, noted Dr. Mebazaa. “The trial was designed many years ago, and at that time, we were still thinking that giving very aggressive treatment in the first hours could have an impact.

“Now, when we will be treating patients with vasodilators with acute heart failure – at least myself and my group – I would really wonder whether there is still evidence in the world to support the use of those agents.”